Background: Jade-1 localizes to the primary cilium and centrosome and inhibits canonical Wnt signaling.

Results: Casein kinase 1 α phosphorylates Jade-1 at a conserved SLS motif.

Conclusion: Jade-1 phosphorylation abrogates its ability to inhibit β-catenin signaling.

Significance: These results contribute to understanding β-catenin regulation, which is central to discovering new therapeutic targets for diseases involving the Wnt signaling pathway.

Keywords: β-catenin (B-catenin), Centrosome, Cilia, Phosphorylation, Wnt Signaling, NPHP4, Casein Kinase 1 α

Abstract

Tight regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is critical for vertebrate development and tissue maintenance, and deregulation can lead to a host of disease phenotypes, including developmental disorders and cancer. Proteins associated with primary cilia and centrosomes have been demonstrated to negatively regulate canonical Wnt signaling in interphase cells. The plant homeodomain zinc finger protein Jade-1 can act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase-targeting β-catenin for proteasomal degradation and concentrates at the centrosome and ciliary basal body in addition to the nucleus in interphase cells. We demonstrate that the destruction complex component casein kinase 1α (CK1α) phosphorylates Jade-1 at a conserved SLS motif and reduces the ability of Jade-1 to inhibit β-catenin signaling. Consistently, Jade-1 lacking the SLS motif is more effective than wild-type Jade-1 in reducing β-catenin-induced secondary axis formation in Xenopus laevis embryos in vivo. Interestingly, CK1α also phosphorylates β-catenin and the destruction complex component adenomatous polyposis coli at a similar SLS motif to the effect that β-catenin is targeted for degradation. The opposing effect of Jade-1 phosphorylation by CK1α suggests a novel example of the dual functions of CK1α activity to either oppose or promote canonical Wnt signaling in a context-dependent manner.

Introduction

Wnt/β-catenin signaling has long been recognized as a critical regulator of vertebrate development (1, 2). More recently, the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in pluripotent stem cell renewal and adult tissue repair has been increasingly explored (3–5). In differentiated cells, β-catenin functions as an adhesion molecule, and unbound cytosolic β-catenin is degraded rapidly. However, up-regulated Wnt signaling prevents degradation and allows unbound β-catenin to translocate to the nucleus, where it acts as a transcription factor for several genes involved in proliferation (for a review, see Refs. 2, 6, 7). β-catenin signaling during repair is critical in multiple adult organ systems, including the kidney (8, 9), colon (10, 11), lung (12), liver (13), bone (14), and central nervous system (15, 16). Consistently, deregulated Wnt/β-catenin signaling is associated with diseases ranging from Alzheimer disease and schizophrenia to osteoporosis and cystic kidney disease (9, 15, 17). Furthermore, β-catenin accumulation is widely associated with tumorigenesis, and several tumor types have underlying germ line or sporadic mutations that disrupt β-catenin degradation (18, 19). The context-dependent mechanisms regulating β-catenin signaling continue to be discovered, but it remains difficult to selectively and temporally target specific components of this pathway.

Several reports have demonstrated that the primary cilium and centrosome restrain β-catenin signaling in interphase cells (20–22), and that several components of the β-catenin destruction complex localize to the base of the primary cilium (23–25). Recently, our group demonstrated that Jade-1, an E3-ubiquitin ligase that targets β-catenin for proteasomal degradation (26), localizes to the primary cilium and is regulated by the ciliary nephrocystin protein complex (27). Specifically, nephrocystin-4 (NPHP4) stabilizes a non-phosphorylated form of Jade-1, increasing Jade-1 nuclear translocation and inhibiting β-catenin signaling. Loss of nephrocystin complex function leads to nephronophthisis, the leading genetic cause of end-stage kidney failure in children. To further determine the mechanisms underlying Jade-1 regulation of β-catenin signaling, we sought to identify specific kinases responsible for the phosphorylation of Jade-1. We now report that the classical Wnt pathway component casein kinase 1 α (CK1α) specifically phosphorylates Jade-1 at an unprimed SLS phosphorylation site, initiating a phosphorylation cascade that abrogates the ability of Jade-1 to inhibit β-catenin signaling.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids, Antibodies, and siRNA

FLAG (F)-tagged5 or V5-tagged plasmids were generated by PCR from the fetal human kidney cDNA library (Stratagene) and inserted into a modified pcDNA6 vector (Invitrogen) using standard cloning techniques. All plasmids were verified by automated DNA sequencing. M50 Super 8×TOPFlash was generated by the Moon laboratory and received from Addgene (plasmids 12456). Renilla luciferase pGL4.74 was purchased from Promega (catalog no. E6921). Site-directed mutagenesis was achieved using the relevant wild-type plasmid as a template together with primers containing alterations to the minimum number of bases required to modify the residues of interest. A silent mutation was also included to yield a novel restriction site for diagnostic digest. After PCR, the product was incubated with 1 μl of Dpn1 for 2 h at 37 °C, followed by heat inactivation at 70 °C for 10 min to digest methylated template DNA. Antibodies were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (monoclonal mouse anti-FLAG (M2) and monoclonal mouse anti-β-tubulin), Abcam (polyclonal rabbit anti-fibrillarin), Serotec (monoclonal mouse anti-V5), Proteintech (polyclonal rabbit anti-Jade-1), Covance (polyclonal rabbit anti-HA tag), GE Healthcare (polyclonal goat anti-GST), and Santa Cruz Biotechnology (polyclonal goat anti-CK1α (catalog no. sc-6477) and polyclonal goat anti-Densin-180 (catalog no. sc-15447)). Oligonucleotides for RNAi have been described previously and were purchased from Biomers (Konstanz, Germany) or Integrated DNA Technologies (Leuven, Belgium). Sequences were directed as follows: Jade-1 siRNA (26), 5′-AAGTTGAAGAGGAAGGTCAACTT-3′; CK1α siRNA #1 (28), 5′-CCAGGCATCCCCAGTTGCT-3′; CK1α siRNA #2 (29), 5′-AATCTCAGAAGGCCAGGCATC-3′; and control siRNA (30), 5′-AAATGTACTGCGCGTGGAGAC-3′.

Cell Culture

HEK 293T cells were cultured in DMEM (Sigma) supplemented with 10% FBS as described previously (27). For transfection experiments, cells were seeded in 10-cm or 6-well dishes, grown to 60% confluency, and transiently transfected with plasmid DNA using the calcium phosphate method as described previously (31, 32). For luciferase and siRNA experiments, cells were grown to 80% confluency in 6-well or 96-well plates and transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the instructions of the manufacturer. 24 h post-transfection, cells in 6-well dishes were harvested in 1 ml of cold PBS, and the centrifuged pellet was boiled in Laemmli buffer at 95 °C for 10 min to obtain whole cell lysate. Cells in 10-cm dishes were harvested with 6 ml of cold PBS and centrifuged, and the cell pellet was used for cell fractionation or coimmunoprecipitation experiments as described previously (27). Proteins were immunoprecipitated using anti-FLAG-agarose beads (M2, Sigma), nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen), or 2 μg of antibody coupled to protein G beads (GE Healthcare), as indicated in the figure legends. For cell fraction experiments, all nuclear pellets were resuspended in a high-salt buffer, sonicated, and boiled in Laemmli buffer. Densitometry values were obtained using Image Studio Lite version 4.0.21 (LI-COR Biosciences) and calculated as follows. Each cytosolic F.β-catenin value was normalized by the respective cytosolic β-tubulin value in each condition. Nuclear F.β-catenin values were likewise normalized by nuclear fibrillarin. Values for each protein analyzed were set to a percentage across each image to control for exposure times. Experiments were normalized by setting total β-catenin values to 1 across all conditions independently for the cytosol and nucleus. Differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA.

Ubiquitinated Protein Detection

Transfected HEK 293T cells were incubated with MG132 (1 μm for 7 h) prior to harvesting 48 h post-transfection. Ubiquitinated proteins were detected according to a modified protocol from Choo et al. (33). Cell monolayers were washed with PBS and scraped in 150 μl of lysis buffer (2% SDS, 150 mm NaCl, and 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0)) with 2 mm Na3VO4, 50 mm PMSF, and 25 mm N-ethylmaleimide and boiled immediately at 95 °C for 10 min. Boiled lysates were sonicated and diluted in 900 μl of dilution buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mm NaCl, 2 mm EDTA, and 1% Triton) prior to incubation with rotation at 4 °C for 60 min. Lysates were subsequently centrifuged for 30 min at 20,000 × g, and supernatants were equalized for protein concentration according to the BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific). 30 μl of equalized protein lysate was immediately boiled with Laemmli buffer as an “IP lysate.” 950 μl of equalized protein lysate was incubated overnight with 30 μl of FLAG (M2) beads. After incubation, beads were washed three time in wash buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 m NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, and 1% Nonidet P-40) and boiled with Laemmli buffer for 5 min at 95 °C, and then binding proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Ubiquitinated F.β-catenin values were determined using densitometry software (Image Studio Lite version 4.0.21, LI-COR Biosciences) and calculated as follows. The densitometry value for the HA-ubiquitin smear corresponding to immunoprecipitated β-catenin was normalized by the heavy chain of the precipitated beads, and this value was then divided by the densitometry value for FLAG staining, representing the immunoprecipitated F.β-catenin normalized by the heavy chain of the precipitated beads. To control for variation in exposure intensity, the sum of measured values in an individual blot was set to 100%. Differences were assessed by one-way ANOVA.

Reagents

MG132 InSolution was purchased from Calbiochem. LiCl was purchased from Merck and resuspended in water. D4476 was purchased from Sigma and resuspended in dimethyl sulfoxide. Cells previously transfected for 24 h were incubated in a final concentration of 100 μm D4476 for an additional 24-h period. D4476 was transfected using a modified protocol to enhance solubility (34) whereby 10 μl of a 10 mm stock solution was diluted in 50 μl of Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) and incubated with 3 μl of Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for 20 min at room temperature before application to cells in 1 ml of DMEM. Control cells were incubated with an equal amount of dimethyl sulfoxide. BI 2536 was purchased from Selleck Chemicals and resuspended in water. Cells previously transfected for 24 h were incubated in a final concentration of 100 nm BI 2536 for an additional 24-h period.

In Vitro Kinase Assay and Direct Interaction

For downstream coprecipitation and mass spectrometry applications, 500 ng of GST-tagged CK1α (Sigma, catalog no. SRP5013) was incubated for 15 min at 30 °C in a 25-μl reaction containing 10 μl of the kinase assay buffer recommended by the manufacturer (diluted 5-fold in water plus 0.25 mm DTT) with or without 5 μg of recombinant His-tagged Jade-1 truncation (amino acids 4–174) and 80 nm (final concentration) ATP, as indicated in the figure legends. Recombinant His-tagged Jade-1 4–174 was expressed according to the standard protocol in BL21 bacteria. Direct interaction was assessed by diluting the completed reaction with 1 ml of IP buffer and proceeding according to the immunoprecipitation protocol as described above.

Mass Spectrometry and Phosphoproteomic Analysis

Phosphoproteomic analysis of whole cell lysates was performed as described previously with slight modifications (35, 36). Harvested HEK 293T cells were lysed in a buffer containing 8 m urea and 50 mm ammonium bicarbonate with added Pierce protease and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (Thermo Scientific). Protein concentration was determined by BCA protein assay (Thermo Scientific). 400 μg of total protein was reduced using DTT and alkylated using iodoacetamide, as described previously, and peptides were digested using trypsin at a w/w ratio of 1:50 at 37 °C for 16 h. After desalting procedure, phosphopeptides were enriched using ferric nitrolotriacetate immobilized metal affinity chromatography columns (Thermo Scientific). After final cleanup (ZipTip columns, Millipore), samples were analyzed using an LTQ Orbitrap Discovery mass spectrometer (Thermo Scientific) coupled to a Proxeon EASY-nLC II nano-LC system (Proxeon/Thermo Scientific). Intact peptides were detected at a resolution of 30,000 in the m/z range of 200–2000 (MS). Internal calibration was performed using the ion signal of (Si(CH3)2O)6H at m/z 445.120025 as a lock mass. For LC-MS/MS analysis, up to five collision-induced dissociation spectra (MS2) were acquired following each full MS scan. Sample aliquots were separated on a 15-cm, 75-μm reverse phase column (Proxeon/Thermo Scientific). Gradient elution was performed from 10–40% acetonitrile within 90 min at a flow rate of 250 nl/min. Generated raw data were searched using the SEQUEST algorithm against the most recent version of the Uniprot human database. The false discovery rate was adjusted to be lower than 0.01. Analysis and visualization of spectra were performed using the ProteomeDiscoverer software (Thermo Scientific). Label-free quantification and visualization of MS1 precursor masses were performed using the QUOIL software (37, 38).

An in vitro kinase assay (described above) was used to detect specific residues phosphorylated by CK1α. After reaction completion, peptides were reduced, alkylated, and digested using trypsin overnight, as described previously (35). Subsequently, peptides were subjected to C18 cleanup as described above and then resuspended in 10 μl of 0.1% formic acid. Peptides were separated using a 90-min nLC-MS/MS gradient on a 15-cm C18 column (Dr. Maisch) and sprayed into a Q Exactive Plus mass spectrometer (Thermo, Bremen, Germany). Gradient settings are described above. The setting for peptide fragmentation on a Q Exactive plus mass spectrometer were as follows. An MS1 scan (resolution, 70,000; scan range, 300–2000 m/z) was followed by 20 MS2 scans acquired in the Orbitrap (resolution, 75,000; isolation window, 3 m/z) using higher energy collisional dissociation fractionation. Dynamic exclusion was enabled (10 s).

Thermo raw files were analyzed using the MaxQuant software suite, as described previously, with the label-free quantitation option enabled (36, 39, 40). Briefly, carbamidomethylation of cysteine was put as a fixed modification, and phosphorylation and N-terminal acetylation was put as a variable modification. Peptide identifications were only accepted when they matched a protein and peptide identification false discovery rate of less than 0.01 and when the site localization false discovery rate was less than 0.01. Only high-confidence localized peptides (MaxQuant localization score >0.75) were used for further analysis. Spectra were displayed and annotated using MaxQuant viewer software (39).

Luciferase Assay

HEK 293T cells were seeded into 96-well plates and transfected as described above, with a total amount of 130 ng of DNA/well (50 ng of TOPFlash firefly luciferase, 25 ng of constitutively active Renilla luciferase pGL4.74, 5 ng of FLAG.β-catenin, and 25 ng each of experimental plasmids as indicated in the figure legends; total DNA transfected was balanced when necessary using empty vector). Where indicated in the figure legends, 25 nm siRNA was used. Transfections, lyses, and measurements were performed as described previously (27). Significance was assessed for all β-catenin-stimulated treatment groups using a one-way analysis of variance with Tukey's post hoc test or two-way analysis of variance with post hoc Bonferroni-corrected paired Student's t tests. Error bars represent mean ± S.E.

Xenopus laevis Microinjections and Double Axis Assay

X. laevis embryos were cultured, manipulated, and staged as described elsewhere (41). In brief, X. laevis eggs were obtained from females injected with 500–800 units of human chorionic gonadotropin. Eggs were fertilized in vitro and dejellied with 3% cysteine. For microinjection, eggs were transferred into Ficoll (3% Ficoll in 0.3× Marc's modified Ringer's medium). Microinjection of 10 nl containing the indicated amount of RNA into one ventral blastomere of Xenopus was performed at the four-cell stage. 12 h after injection, the embryos were transferred into 0.3× Marc's modified Ringer's medium plus gentamicin and cultivated at 13 °C until harvested and staged according to Nieuwkoop and Faber (63). Secondary axis formation was scored morphologically at stage 39. Statistical analysis was performed using Sigma-Stat 3.5 (Systat Software, Germany). All experiments were approved by the institutional animal committee (Regierungspräsidium Baden-Württemberg).

In Vitro Synthesis of mRNA

Plasmids were linearized with the following enzymes: Jade1 VF10, Sal1 and β-catenin CS2+MT, and NotI (5′ deletion of 138 bp to eliminate a possible GSK3 sequence). Linearized plasmids were purified by phenol-chloroform. In vitro synthesis of synthetically capped mRNA was performed by in vitro transcription with T7 or SP6 polymerase using the mMessage mMachine kit (Ambion), and the RNA was purified using the RNAeasy mini kit (Qiagen).

RESULTS

Jade-1 Is Phosphorylated by CK1α at a Conserved SLS Motif

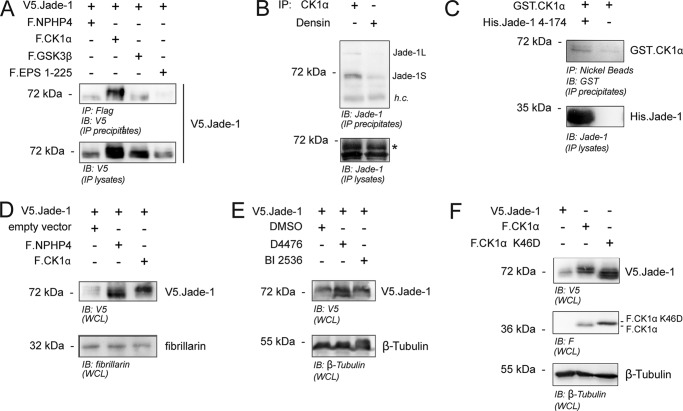

To determine whether Jade-1 could be a substrate of a Wnt pathway kinase, we analyzed specific protein-protein interactions by coimmunoprecipitation experiments. V5-tagged short isoform Jade-1 (V5.Jade-1) was found to coprecipitate with two overexpressed classical Wnt/β-catenin pathway kinases, FLAG-tagged GSK3β (F.GSK3β) and FLAG-tagged CK1α (F.CK1α). In these experiments, we observed that coexpression of F.CK1α, but not F.GSK3β, shifted the size of V5.Jade-1 to a higher molecular weight (Fig. 1A). With an endogenous coimmunoprecipitation experiment, we also demonstrated that both the long and short isoforms of endogenous Jade-1 coprecipitated with endogenous CK1α (Fig. 1B). Moreover, in vitro interaction experiments using recombinant purified proteins suggested that this interaction is direct (Fig. 1C). In our previous study, we described that Jade-1, in whole cell lysates, presents as a double band, and we proposed that the upper band might result from phosphorylation of Jade-1 (27). To confirm the size shift because of CK1α in nuclei-containing whole cell lysates, Western blot visualization of V5.Jade-1 coexpressed with empty vector was compared with that of V5.Jade-1 coexpressed with either F.CK1α or F.NPHP4. Consistent with our previous findings, coexpression with F.NPHP4 stabilized the smaller form of V5.Jade-1, whereas coexpression with F.CK1α stabilized the larger form of V5.Jade-1 (Fig. 1D). Conversely, inhibition of CK1α kinase activity using the specific CK1 inhibitor D4476 led to the stabilization of the smaller V5.Jade-1 expression size, whereas a control kinase inhibitor, BI 2536, had no effect (Fig. 1E). Strikingly, coexpression of a kinase-dead version of F.CK1α possessing a mutation of the lysine at residue 46 to aspartic acid (29) failed to stabilize the larger form of V5.Jade-1 and, instead, potently reduced expression size (Fig. 1F). Taken together, these data suggest that Jade-1 is phosphorylated by CK1α.

FIGURE 1.

The canonical Wnt pathway kinase CK1α interacts with and phosphorylates Jade-1S. A, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h. V5.Jade-1 coprecipitated with the FLAG-tagged Wnt-pathway kinases F.GSK3β and F.CK1α as well as a positive control protein (F.NPHP4) but not a negative control protein (F.EPS1–225). Only coexpression of F.CK1α generated a larger band indicative of multiple posttranslational modifications of V5.Jade-1. IB, immunoblot. B, endogenous CK1α or a control protein (Densin) was immunoprecipitated from confluent HEK 293T cells. Both the long and short isoforms of endogenous Jade-1 coprecipitated with CK1α but not Densin despite equal protein amounts in the IP lysate. Asterisk, Jade-1; h.c., heavy chain. C, recombinant purified GST.CK1α was incubated with or without a bacterially expressed and purified recombinant truncation of His.Jade-1 (4–174). Reactions were diluted with IP buffer and incubated overnight with Ni2+ beads. GST.CK1α coprecipitated only with Ni2+ beads plus His.Jade-1 4–174. D, plasmids were transiently transfected as indicated in HEK 293T cells for 24 h prior to harvesting cells as a whole cell lysate (WCL). Coexpression of F.CK1α stabilized protein expression of V5.Jade-1 but increased band size in contrast to the reduced band size observed when coexpressed with F.NPHP4. E, whole cell lysates of HEK 293T cells transiently transfected for 24 h with the indicated plasmids prior to 18-h exposure to kinase inhibitor or dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) control. The CK1-specific kinase inhibitor D4476 reduces band size of V5.Jade-1 in contrast to the use of dimethyl sulfoxide alone or a control kinase inhibitor, BI 2536. F, plasmids were transiently transfected as indicated in HEK 293T cells and processed 24 h later as a whole cell lysate. Coexpression of a kinase-dead mutant of F.CK1α (K46D) failed to stabilize the larger expression form of V5.Jade-1.

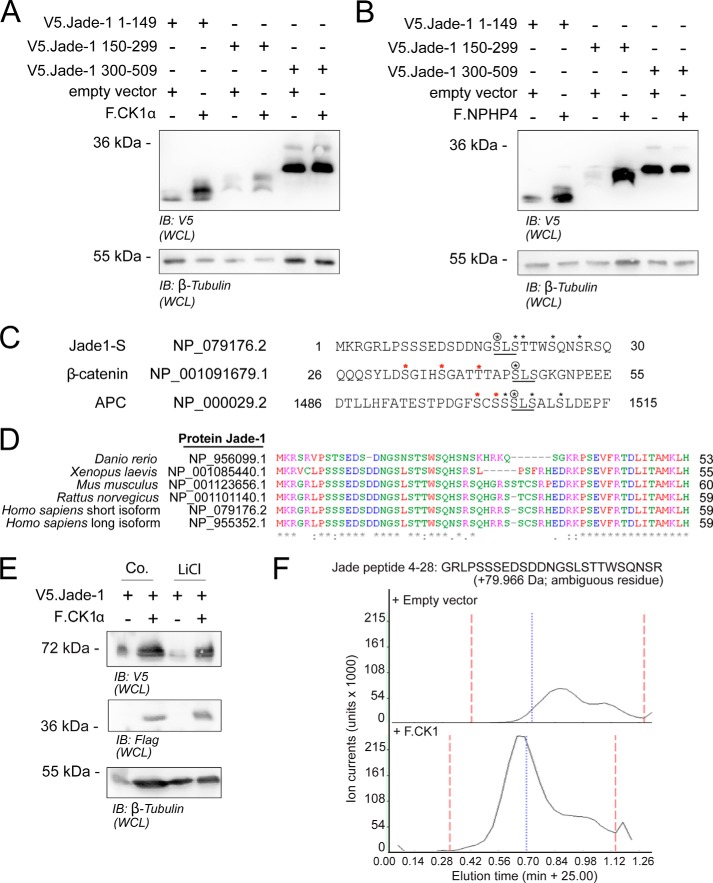

To determine where a candidate phosphorylation site might be located, three truncations of V5.Jade-1 were expressed together with either F.CK1α or F.NPHP4 (Fig. 2, A and B). In both cases, expression of the first 150 amino acids was modified heavily, as is visible by the size shift, whereas expression of the C terminus was unchanged. The middle truncation appears to be only slightly modified by CK1α. However it is strongly stabilized by NPHP4 coexpression. Sequence analysis of the Jade-1 N terminus identified several candidate CK1α phosphorylation motifs according to the consensus sequence of S/Tp-X-X-S/T (42, 43). In addition, one candidate motif was identified at amino acid 18 that could be phosphorylated according to two possible unprimed consensus motifs: either because of the upstream cluster of acidic residues at amino acid positions 11–15 (44, 45) or because of the following two residues that, together, create an SLS phosphorylation motif. Such an unprimed SLS phosphorylation motif is also used by CK1α to phosphorylate the canonical Wnt pathway components β-catenin (46) and adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) (47), where unprimed phosphorylation by CK1α initiates a primed phosphorylation cascade in combination with GSK3β (Fig. 2C). This candidate multiple phosphorylation motif of human Jade-1 is highly conserved across species (Fig. 2D), as, indeed, is the entire protein sequence (data not shown). To determine whether a CK1-initiated phosphorylation cascade on the Jade-1 N terminus might require the tandem activity of GSK3β, V5.Jade-1 was coexpressed with F.CK1α in the presence of LiCl, a known GSK3β inhibitor. LiCl treatment failed to interfere with the stabilization of the larger form of Jade-1 by F.CK1α (Fig. 2E), confirming CK1α as the major kinase for Jade-1, whereas GSK3β might have only a minor influence on the CK1α-Jade-1 axis.

FIGURE 2.

The N terminus of Jade-1S is phosphorylated by CK1α on a conserved non-canonical SLS motif identical to that phosphorylated on APC and β-catenin by CK1α. A and B, truncations of V5.Jade-1 were coexpressed in HEK 293T cells with a vector control and either F.CK1α (A) or F.NPHP4 (B) for 24 h and harvested as a whole cell lysate (WCL). In both cases, the N-terminal fragment containing the first 150 amino acids was modified heavily, whereas the C-terminal fragment was not affected. IB, immunoblot. C, the non-canonical unprimed SLS motif leads to phosphorylation of the initial serine (circled asterisk), which can prime sequential phosphorylation on multiple classical CK1α motifs (black asterisks). In two other canonical Wnt pathway proteins, β-catenin (46) and APC (47), the SLS motif initiates multiple sequential phosphorylation events by CK1α or GSK3β (red asterisks) that are important for destruction complex function. D, sequence alignment demonstrated 95% sequence homology between species for Jade-1, including the N-terminal CK1α phosphorylation motifs and the SLS motif at position 18 (only the N terminus shown). E, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with the indicated plasmids for 24 h prior to 24-h incubation with control (Co) medium or medium containing 40 μm LiCl. After a total of 48 h post-transfection, cells were harvested as a whole cell lysate. Incubation with LiCl did not alter the ability of F.CK1α to stabilize the larger expression form of V5.Jade-1. F, HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with V5.Jade-1 and either F.CK1α or an empty vector control for 48 h. Mass spectrometry analysis of whole cell lysates confirmed increased phosphorylation of an N-terminal fragment of V5.Jade-1 in the presence of overexpressed F.CK1α but was unable to determine specific phosphorylated residues because of the presence of multiple potential phosphorylation sites (lack of site-determining peak). Shown is a representative graph depicting the MS1 precursor ion chromatograms of the respective phosphorylated peptide. Three biological replicates were performed.

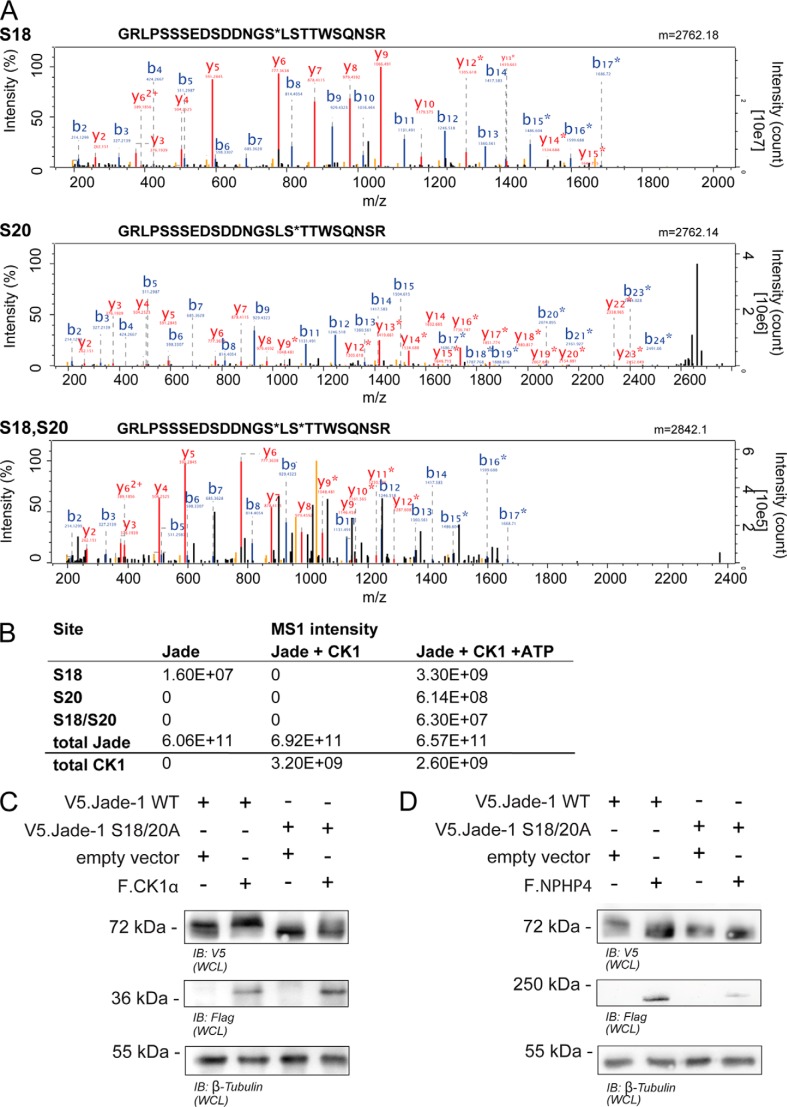

Phosphoproteomic analyses of HEK 293T cells expressing Jade-1 in the presence or absence of overexpressed CK1α were performed to confirm the phosphorylation of the Jade-1 residues Ser-18 and Ser-20. Although a dramatic increase in total Jade-1 phosphorylation in a peptide containing residues Ser-18 and Ser-20 could be shown in the presence of F.CK1α (Fig. 2F), initial attempts to localize the site specifically in the MS2 spectrum (CID) failed because of the multiple phosphorylatable residues in the N terminus. Therefore, a recombinant N-terminal peptide fragment of Jade-1 (amino acids 4–174) was incubated in vitro with CK1α protein and ATP. MS/MS analysis using HCD fractionation (48) identified both single phosphorylated (Ser-18 and Ser-20 individually) as well as double phosphorylated (Ser-18 and Ser-20 together) peptides (Fig. 3, A and B). There was no evidence for phosphorylation of any of the other serine or threonine residues within this peptide sequence (on the basis of label-free quantification of MS1 precursor intensities (39, 40)). In addition, there was no evidence for phosphorylation when ATP was omitted (Fig. 3B). To further confirm the requirement of residues Ser-18 and Ser-20 for CK1α-mediated phosphorylation of Jade-1, a construct with point mutations of both residues was generated (V5.Jade-1 S18/20A). Mutation of both Ser-18 and Ser-20 to alanine abolished the expression of the larger form of V5.Jade-1 under basal conditions and significantly reduced the expression of the larger form induced by the presence of overexpressed F.CK1α but did not alter expression size in the presence of F.NPHP4 (Fig. 3, C and D). The single point mutation of serine 18 or double point mutation of the upstream acidic residues did not significantly alter Jade-1 expression (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

CK1α-mediated phosphorylation of Jade-1 at the SLS site is confirmed in mass spectrometry and protein expression. A, MS2 spectra of phosphopeptides identified by HCD fragmentation. Recombinant peptides were incubated with CK1 and ATP in vitro and subjected to phosphoproteomic analysis. Three phosphopeptides (containing phosphorylated Ser-18, phosphorylated Ser-20, and both Ser-18 and Ser-20) were identified with high confidence. B and y ions are annotated, and asterisks indicate phosphorylated ion species. B, intensities obtained by label-free quantification of identified Jade species. Intensities were highly increased in the presence of both CK1 and ATP. Phosphorylated species were not detected in the presence of CK1 without ATP. C and D, wild-type V5.Jade-1 or a version containing a mutated SLS motif was overexpressed in HEK 293T cells for 24 h with either F.CK1α (C) or F.NPHP4 (D) and harvested as a whole cell lysate (WCL). Mutation of the SLS site abrogated the ability of coexpressed F.CK1α to increase the expression size of V5.Jade-1, whereas the expression size of the V5.Jade-1 SLS → ALA mutant was not reduced further by coexpressed F.NPHP4. B, immunoblot.

Jade-1 Phosphorylation Abrogates Its Ability to Inhibit β-Catenin Signaling

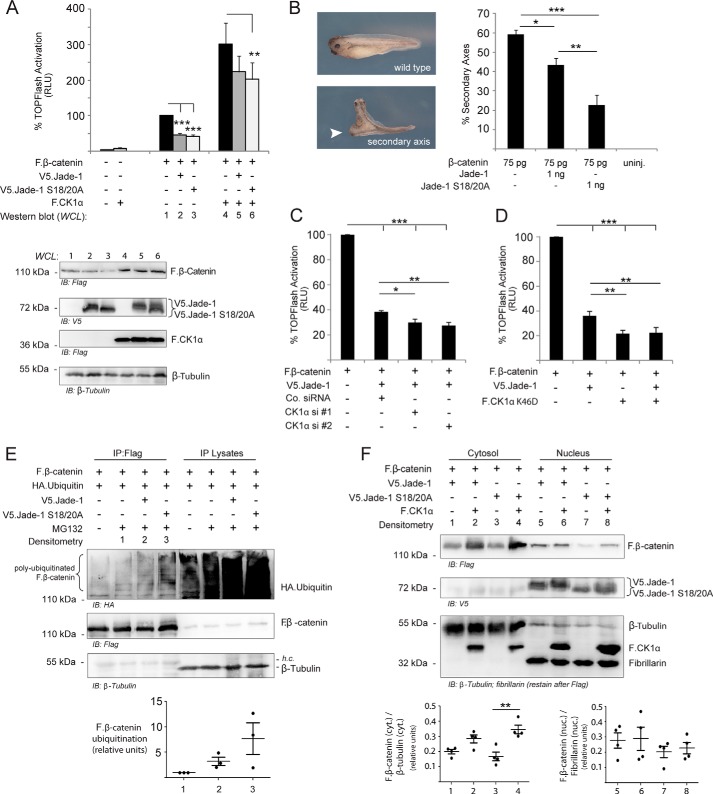

TOPflash TCF/LEF reporter assays were used to determine whether phosphorylation of Jade-1 altered the ability of Jade-1 to negatively regulate canonical Wnt signaling. Wild-type V5.Jade-1 and the S18A/S20A mutant version both reduced β-catenin-stimulated Wnt reporter activation. Overexpression of F.CK1α was not sufficient to activate TOPflash reporter activity but substantially potentiated β-catenin-stimulated reporter activity. In this condition, expression of V5.Jade-1 wild-type did not achieve a significant reduction of reporter activity, whereas V5.Jade-1 S18A/S20A lacking the intact bona fide CK1α phosphorylation motif did (Fig. 4A). Western blot analysis of whole cell protein expression in the luciferase transfection setting confirmed a stabilization of F.β-catenin in the presence of F.CK1α.

FIGURE 4.

CK1α impairs the ability of Jade-1S to inhibit Wnt reporter activity, and this is dependent on an intact SLS motif. A, the TOPflash Wnt reporter plasmid was cotransfected with a constitutively active Renilla luciferase reporter plasmid plus F.β-catenin and experimental plasmids as indicated. Background activation was determined by omitting experimental plasmids and was not included in the statistical analysis. All plasmids were transiently transfected for 24 h in HEK 293T cells, and relative light units (RLU) are shown after normalization to Renilla luciferase activity, setting activation because of F.β-catenin alone to 100%. Coexpression of experimental plasmids significantly altered TOPflash reporter activity, as assessed by two-way ANOVA, with significant main effects across Jade-1 condition (F(2,32) = 44.78, p < 0.0001) as well as the presence/absence of F.CK1α. (F(1,32) = 13; p = 0.0024). Post hoc analyses determined that overexpressed wild-type and the S18A/S20A mutant of V5.Jade-1 both significantly reduced TOPflash activation stimulated by F.β-catenin overexpression. Overexpressed F.CK1α potentiated TOPflash reporter activity. This potentiation was reduced significantly in the presence of the S18A/S20A mutant version of V5.Jade-1 but not by wild-type V5.Jade-1 (Bonferroni-corrected paired Student's t tests as post hoc with 15 possible comparisons. **, p < 0.001; ***, p < 0.0001. Western blot analysis of protein expression was obtained by scaling up transfection of the indicated plasmids (see “Experimental Procedures”) and harvesting cells as a whole cell lysate (WCL) to visualize nuclear as well as cytosolic proteins. B, double axis assays in X. laevis were performed by mRNA injection into one of four blastomeres (ventral) at the indicated concentrations. Injection of β-catenin mRNA alone resulted in the formation of a secondary axis (white arrow). Injection of Jade-1 mRNA in combination with β-catenin mRNA significantly reduced secondary axis formation. The reduction of double axis formation was enhanced significantly when β-catenin mRNA was injected in combination with the Jade-1 S18A/S20A mutant mRNA. Results of three independent experiments are shown (n = total injected embryos). Results were assessed by one-way ANOVA (F(3,11) = 61.72, p < 0.0001) with Tukey's post hoc (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001). uninj., uninjected. C and D, TOPflash luciferase experiments were performed in HEK 293T cells as described above with 24-h transient transfection of plasmids, reporter plasmids, and siRNA as indicated. Results were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (F(3,19) = 1.584, p < 0.0001 (C); F(3,15) = 4.977, p < 0.0001 (D)), and Tukey's post hoc analysis demonstrated that the ability of Jade-1 to inhibit F.β-catenin reporter activity was enhanced significantly by either endogenous CK1α knockdown or coexpression of a kinase-dead version of F.CK1α (K46D). *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001. E, plasmids were transiently transfected as indicated in HEK 293T cells for 16 h prior to incubation with or without MG132 for 7 h at 1 μm. Cells were harvested in SDS lysis buffer and processed according to the ubiquitin detection protocol (see “Experimental Procedures”). F.β-catenin was immunoprecipitated, and, after boiling in Laemmli buffer, supernatants were divided in two and run on separate SDS gels to visualize both HA and FLAG staining. The non-phosphorylatable version of V5.Jade-1 S18A/S20A was more effective at ubiquitinating F.β-catenin, although variability in densitometry analysis indicates that other factors may be involved. F, plasmids were transiently transfected as indicated in HEK 293T cells for 24 h prior to processing according to the cell fraction protocol (see “Experimental Procedures”). Overexpression of F.CK1α led to stabilized cytosolic (Cyt) F.β-catenin. Overexpression of V5.Jade-1 S18A/S20A trended to reduced nuclear F.β-catenin even when F.CK1α was coexpressed. The bar graphs represent densitometry values obtained from four independent experiments (see “Experimental Procedures”). Significant differences were found within the cytosolic data set as assessed by one-way ANOVA (F(3,15) = 7.583, p = 0.0078) with Tukey's post hoc (**, p < 0.01). Black circles are individual data points.

The influence of CK1α phosphorylation was further explored in vivo using the X. laevis model system. Overactive canonical Wnt signaling is well known to produce a double axis in developing X. laevis, and inhibition of this phenotype can be assessed by coinjecting mRNA into the developing embryo. Both wild-type and S18A/S20A mutant Jade-1 mRNA were able to reduce β-catenin-induced double axis formation (Fig. 4B). Consistent with our TCF/LEF reporter assay results, inhibition of double axis formation was enhanced significantly by the mutant S18A/S20A Jade-1 mRNA, demonstrating an in vivo phosphorylation-dependent difference in efficacy of β-catenin regulation by Jade-1. Subsequent studies were able to demonstrate a similar inhibition of CK1α-induced double axis formation by both versions of Jade-1. However, at non-toxic doses of CK1α, not a sufficient number of double axes was generated to determine a difference between the inhibition efficacies of wild-type and mutant Jade-1 (data not shown).

That CK1α acts in an inhibitory manner to reduce the ability of Jade-1 to inhibit Wnt signaling was further supported by RNAi knockdown of endogenous CK1α. When endogenous CK1α protein levels were reduced by 50% using siRNA, the same amount of transfected V5.Jade-1 was significantly more effective in reducing TOPflash reporter activity (Fig. 4C). Consistently, coexpression of the F.CK1α K46D construct, which stabilizes the apparently non-phosphorylated smaller version of V5.Jade-1, augmented TOPflash reporter inhibition (Fig. 4D). It is notable that the kinase-dead version of F.CK1α failed to potentiate TOPflash reporter activity as the wild-type version does. We were unable to detect a significant difference in the effect of either wild-type or kinase-dead CK1 on TOPflash reporter activity in the presence of Jade-1 siRNA, indicating that Jade-1 does not influence CK1 in a reciprocal manner (data not shown).

Western blot visualization of overexpressed proteins in the luciferase transfection protocol did not demonstrate a large difference between total F.β-catenin expression when coexpressed with wild-type versus mutant V5.Jade-1 and assessed as a whole cell lysate (Fig. 4A). However, an increased amount of ubiquitinated F.β-catenin could be detected in the presence of mutant versus wild-type V5.Jade-1 (Fig. 4E). It is important to note that densitometry analysis of the HA-ubiquitin smear relative to the amount of F.β-catenin precipitated did not reach statistical significance because of the variability between experiments, indicating that other factors likely play a role in modulating the ubiquitin ligase function of Jade-1. When F.β-catenin expression was assessed specifically in the cytosol versus the nucleus, it appeared that coexpression of V5.Jade-1 S18/20A was better able than wild-type V5.Jade-1 to reduce expression of F.β-catenin specifically in the nucleus (Fig. 4F). This effect persisted even in the presence of overexpressed F.CK1α, although variability again indicates that other factors are at play. Of interest, the stabilization of F.β-catenin in the presence of overexpressed F.CK1α appears to largely be seen in the cytosolic fraction.

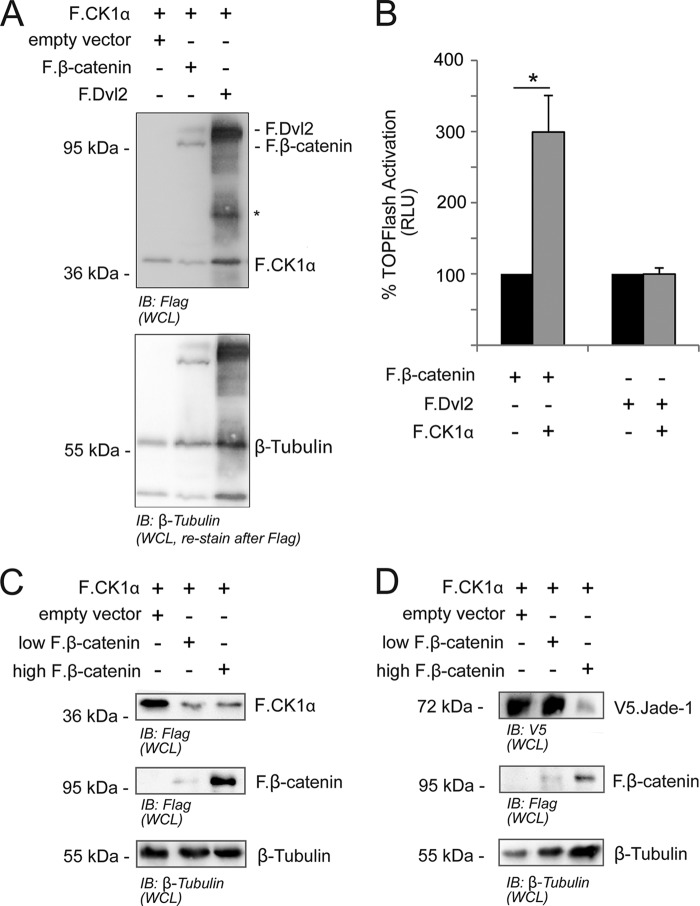

The canonical Wnt signaling model predicts that CK1α should function within the destruction complex when there is no upstream Wnt receptor activation. Therefore, the augmentation of TCF/LEF reporter activity because of CK1α overexpression was unexpected. However, CK1α has also been implicated as a positive regulator of Wnt reporter activity in HEK293 cells (49) and is known to stabilize β-catenin and activate Wnt signaling in X. laevis embryos (50). Although it remains possible that CK1α acts as a positive regulator in our luciferase experiments, further examination of our system revealed that overexpressed F.β-catenin substantially decreased expression of F.CK1α (Fig. 5, A and C), suggesting instead that the augmented signal could be due to factors that reduce stability of a negative regulator in the context of β-catenin expression. That this could be a specific effect is supported by our observation that overexpression of F.Dvl2, which also activates TOPflash reporter activity, does not decrease F.CK1α expression. Consistently, TOPflash reporter activity is only augmented by F.CK1α when the assay is activated by F.β-catenin and not by F.Dvl2 (Fig. 5B). Further analysis revealed that, at a higher threshold of F.β-catenin, V5.Jade-1 expression was also reduced (Fig. 5D), suggesting the possibility that a general downstream positive feedback exists when F.β-catenin is stabilized in our cell-based system.

FIGURE 5.

Overexpressed F.β-catenin, but not F.Dvl2, decreases protein expression of F.CK1α. A, plasmids were transiently transfected as indicated for 24 h in HEK 293T cells prior to harvesting as a whole cell lysate (WCL). Coexpression of F.β-catenin, but not F.Dvl2, reduced expression of F.CK1α. Asterisk, nonspecific; IB, immunoblot. B, TOPflash luciferase experiments were performed in HEK 293T cells as described above with 24-h transient transfection of reporter and experimental plasmids as indicated in separate experiments. Data were normalized to activation without F.CK1α in each situation. Results were analyzed by paired Student's t tests. F.CK1α significantly augmented TOPflash reporter activity because of F.β-catenin expression (t(4) = 3.879; *, p < 0.05) but did not alter reporter activity because of F.Dvl2 expression. RLU, relative light units. C, low or high amounts of overexpressed F.β-catenin reduces the expression of F.CK1α. HEK 293T cells were transiently transfected with plasmids as indicated and processed 24 h later as a whole cell lysate. D, whole cell lysates of HEK 293Ts cells transiently transfected for 24 h show reduced V5.Jade-1 expression in the presence of high but not low amounts of F.β-catenin.

DISCUSSION

Regulation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling is critical at all stages of mammalian life. In adults, injury repair requires activation of Wnt/β-catenin signaling, but uncontrolled activation is associated with numerous diseases, including cancer. Specific, local, and temporal targeting of β-catenin remains difficult because of the numerous influencing factors modulating β-catenin signaling and an incomplete understanding of β-catenin functions. The protein Jade-1 is able to act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase for β-catenin in addition to the more classically recognized β-TrCP (26). However, little is known about the physiological situations that may dictate which ubiquitin ligase is required at which time and to what effect. We have demonstrated previously that a non-phosphorylated form of Jade-1 is stabilized by the cilium- and centrosome-associated protein NPHP4 and that this enhances the negative regulation of β-catenin signaling by Jade-1 (27). Here we demonstrate that the classical Wnt kinase CK1α phosphorylates Jade-1 and that this reduces the efficacy of Jade-1 to inhibit β-catenin signaling.

Collectively, our data support that the Jade-1 motif phosphorylated by CK1α is an N-terminal SLS site. By phosphoproteomic analysis using a highly accurate peptide fragmentation method, HCD (48), we show unambiguously that the Jade-1 N-terminal residues Ser-18 and Ser-20 are phosphorylated directly by CK1α in vitro. This phosphorylation site is likely to be a rate-limiting step in a sequential phosphorylation cascade because mutation of both serines to alanines significantly reduced the formation of the larger species of Jade-1 despite several primed S/Tp-X-X-S/T motifs remaining intact immediately following the mutation. Furthermore, a kinase-dead mutant version of F.CK1α failed to stabilize the larger expressed form of V5.Jade-1, indicating that CK1α is not merely acting as a facilitator for another kinase but is integral to initiating the massively phosphorylated N terminus seen in HEK 293T cell lysates in the presence of overexpressed F.CK1α. Phosphorylation of the subsequent primed CK1α sites was not detected in the Jade-1 N-terminal fragment in our in vitro experimental setup, which indicates that another kinase may contribute to the sequential phosphorylation cascade in cells after initial priming by CK1α. The kinase GSK3β acts in tandem with CK1α in the Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. However, our data indicate that, despite the presence of the GSK3β consensus motifs within the Jade-1 N terminus, phosphorylation initiated by CK1α in intact HEK 293T cells does not require GSK3β cooperation because incubation with LiCl failed to interfere with the F.CK1α-induced shift of V5.Jade-1 expression size.

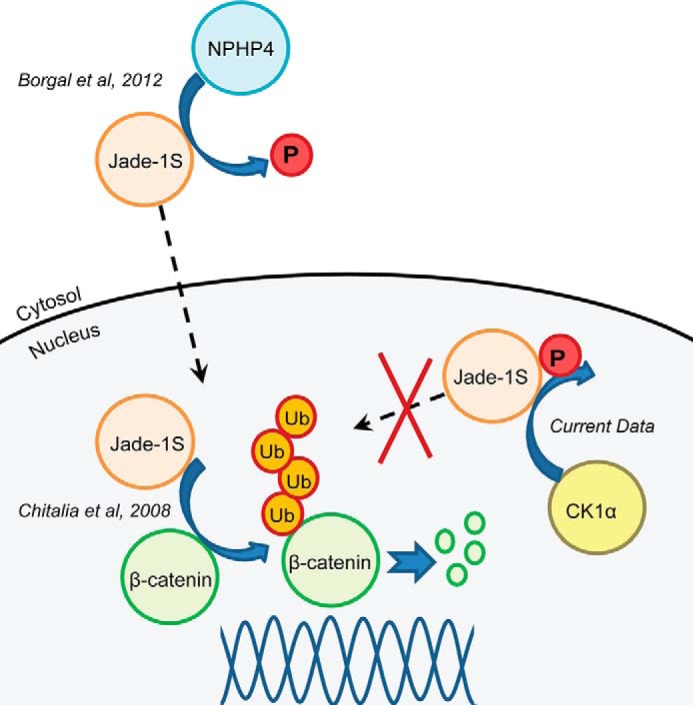

The Jade-1 unprimed SLS phosphorylation motif is highly conserved across species and is similar to that phosphorylated by CK1α on β-catenin (46) and APC (47). In both cell-based and X. laevis models of Wnt signaling, a mutant version of Jade-1 lacking this phosphorylation motif was more effective at inhibiting Wnt activity, and RNAi knockdown of endogenous CK1α enhanced the ability of Jade-1 to inhibit reporter activity. Collectively, these data suggest that CK1α could act to reduce the ability of Jade-1 to ubiquitinate β-catenin (Fig. 6). Indeed, the S18A/S20A mutant version of Jade-1 was better able to ubiquitinate overexpressed F.β-catenin, although the variability of the results indicate that other factors are at play. As demonstrated by cell fractionation data, the stability of F.β-catenin was differentially affected by F.CK1α in the nucleus versus the cytosol, suggesting that these factors may influence protein localization and substrate availability.

FIGURE 6.

Schematic depicting modes of action of Jade-1S relevant to β-catenin ubiquitination. The plant homeodomain zinc finger protein Jade-1 can act as an E3 ubiquitin ligase for β-catenin in both the nucleus and the cytosol, as described by Chitalia et al. (26). NPHP4 stabilizes a non-phosphorylated form of Jade-1 and enhances translocation of Jade-1 to the nucleus, promoting the ability of Jade-1 to inhibit canonical Wnt signaling, as described by Borgal et al. (27). Our data demonstrate that CK1α is able to phosphorylate Jade-1 at a conserved SLS residue and that this phosphorylation abrogates the ability of Jade-1 to inhibit β-catenin signaling. Phosphorylation (P) of Jade-1 by CK1 most likely affects nuclear Jade-1 and could abrogate activity by limiting the ability of Jade-1 to ubiquitinate (Ub) β-catenin.

It is interesting to note that phosphorylation of the SLS motif on β-catenin has the opposite effect. Phosphorylation of Ser-45 on β-catenin negatively regulates canonical Wnt signaling by initiating a phosphorylation cascade that will contribute to cytosolic β-catenin degradation. These opposing roles of CK1α must depend on cellular events governing access of this kinase to each substrate. Individual components of the β-catenin destruction complex have been shown previously to act in opposing manners depending on the activation status of the Wnt signaling cascade (7, 51). For example, phosphorylation of cytosolic β-catenin requires CK1α and GSK3β to work cooperatively within the destruction complex. However, when a Wnt ligand binds a Frizzled (Fz) receptor, the entire destruction complex is recruited to the plasma membrane, where CK1α and GSK3β phosphorylate lipoprotein receptor-related proteins 5 and 6 (LRP5/6) and enhance the LRP-mediated Wnt response (51–53). CK1α complexes with LRP5/6 at 30 min but not 1 h after Wnt stimulation (49). During this time, the adhesion junction proteins E-cadherin and p120-catenin are recruited to the LRP-Fz complex and initially facilitate Dishevelled (Dvl) phosphorylation. However, after 30 min, CK1α phosphorylates E-cadherin, which releases p120-catenin and prevents continued Dvl phosphorylation (49). These events mean that CK1α, a kinase that, in interphase, constitutively acts to restrain inappropriate β-catenin activation, responds to a Wnt signaling event by temporally regulated opposing responses. Initially, CK1α contributes to signal propagation, but it subsequently disables a prolonged response.

A similar situation may govern whether CK1α phosphorylates Jade-1 or β-catenin. In interphase cells, phosphorylated β-catenin accumulates at the centrosome, whereas β-catenin can be observed within the ciliary lumen (20). In addition to accumulating in the nucleus, Jade-1 also accumulates at the centrosome and ciliary base (27), and its role in ubiquitinating this pool of β-catenin could be mediated by the centrosomal NPH proteins. CK1α accumulates at the centrosome when cells enter prophase (54), where it could either phosphorylate β-catenin to inhibit a Wnt response or phosphorylate Jade-1 to enhance it. The balance between these two possibilities might be tipped by NPHP4, which is shown by these data to modify the same N-terminal fragment of Jade-1, as does CK1α in an opposing manner. NPHP4 localizes to the centrosome in confluent cells (55) and might play a role when cells reach confluence in “turning off” a Wnt response. In subconfluent cells, NPHP4 is dispersed throughout the cytoplasm and could play an earlier role during this time in enhancing Jade-1 nuclear translocation. Of note, NPHP4 mRNA is up-regulated after injury (56). Because Jade-1 can also ubiquitinate non-phosphorylated β-catenin (26), the ability of cytosolic NPHP4 to enhance this might be particularly important during injury repair.

The relationship between CK1α and β-catenin is not fully understood. Our current data demonstrate that overexpressed CK1α stabilized F.β-catenin and increased F.β-catenin-induced TOPflash reporter activity. Without an LRP-mediated Wnt response, CK1α should theoretically act within the destruction complex as a negative regulator. However, reports of CK1α potentiating Wnt signaling have been described (49, 50). Our current data suggests a novel route by which CK1α could potentiate a β-catenin signaling activity through phosphorylation of Jade-1. However, it is unlikely that the influence of CK1α on Jade-1 constitutes the major mechanism for the observed potentiation of TOPflash activity because RNAi knockdown of Jade-1 did not alter these results. Instead, it appears that the mechanism could involve phosphorylation of another unknown substrate because a kinase-dead CK1α inhibited TOPflash reporter activity. This mechanism may involve positive feedback because of stabilization of β-catenin in an overexpression context. In this situation, F.β-catenin substantially reduced the stabilization of F.CK1α protein. This effect was specific to β-catenin. Overexpressed Dvl2 neither decreased F.CK1α expression nor led to potentiated TOPflash reporter activity. Furthermore, overexpression of F.CK1α appeared to stabilize F.β-catenin protein levels, again suggesting that an unknown factor may be acting on both proteins. At a higher threshold of F.β-catenin expression, V5.Jade-1 was also destabilized, indicating that a positive feedback mechanism could exist in a more ubiquitous manner. Although it remains to be seen whether these results extend beyond our experimental context, it is interesting to consider that the difference in threshold levels of overexpressed β-catenin required to destabilize V5.Jade-1 versus F.CK1α could reflect the sensitivity of Wnt gene transcription to fold change rather than absolute β-catenin levels, which has been described as a mechanism to buffer response to the background “noise” of β-catenin fluctuation (57).

Threshold differences in β-catenin activity may furthermore contribute to achieving the temporal regulation necessary for operational transients of β-catenin activation to occur. In general, the last decade of research has produced numerous examples whereby the Wnt/β-catenin cascade initiates its own down-regulation via genetic and protein regulation (49, 58–62). Although the multiple mechanisms in place to restrain β-catenin signaling have been studied extensively, the mechanisms used to overcome these restraints in differentiated cells are less well understood. Perhaps this pathway has evolved to use the same players in different contexts to ensure that negative regulators are “engaged otherwise” for a specific amount of time so that an effective signal can be achieved when required, such as during injury repair. This activation then triggers multiple system termination processes, a phenomenon that is telling in terms of how important it is that the pathway does not remain in a prolonged active state. Many of the nuances of Wnt/β-catenin signaling remain to be discovered, and it will be exciting to determine the specific roles played, in particular, by ciliary and centrosomal proteins.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stefanie Keller, Ruth Herzog, Gunter Rappl, and Astrid Wilbrandt-Hennes for technical assistance and members of the laboratories for helpful discussions.

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Grants SCHE1562-2 (to B. S.) and SFB832 (to B. S. and T. B.).

- F

- FLAG tag

- ANOVA

- analysis of variance

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- APC

- adenomatous polyposis coli

- TCF

- T cell factor

- LEF

- lymphoid enhancer factor

- LRP

- lipoprotein receptor-related protein

- Dvl

- Dishevelled

- NPH

- nephronophthisis.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hikasa H., Sokol S. Y. (2013) Wnt signaling in vertebrate axis specification. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 5, a007955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Logan C. Y., Nusse R. (2004) The Wnt signaling pathway in development and disease. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 20, 781–810 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kühl S. J., Kühl M. (2013) On the role of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in stem cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1830, 2297–2306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Perez-Moreno M., Fuchs E. (2006) Catenins: keeping cells from getting their signals crossed. Dev. Cell 11, 601–612 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Reya T., Clevers H. (2005) Wnt signalling in stem cells and cancer. Nature 434, 843–850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Clevers H. (2006) Wnt/β-catenin signaling in development and disease. Cell 127, 469–480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clevers H., Nusse R. (2012) Wnt/β-catenin signaling and disease. Cell 149, 1192–1205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ishibe S., Cantley L. G. (2008) Epithelial-mesenchymal-epithelial cycling in kidney repair. Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 17, 379–385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kawakami T., Ren S., Duffield J. S. (2013) Wnt signalling in kidney diseases: dual roles in renal injury and repair. J. Pathol. 229, 221–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Koch S., Nava P., Addis C., Kim W., Denning T. L., Li L., Parkos C. A., Nusrat A. (2011) The Wnt antagonist Dkk1 regulates intestinal epithelial homeostasis and wound repair. Gastroenterology 141, 259–268, 268.e1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Yamamoto S., Nakase H., Matsuura M., Honzawa Y., Matsumura K., Uza N., Yamaguchi Y., Mizoguchi E., Chiba T. (2013) Heparan sulfate on intestinal epithelial cells plays a critical role in intestinal crypt homeostasis via Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 305, G241–249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Flozak A. S., Lam A. P., Russell S., Jain M., Peled O. N., Sheppard K. A., Beri R., Mutlu G. M., Budinger G. R., Gottardi C. J. (2010) β-Catenin/T-cell factor signaling is activated during lung injury and promotes the survival and migration of alveolar epithelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 3157–3167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Nejak-Bowen K. N., Monga S. P. (2011) β-Catenin signaling, liver regeneration and hepatocellular cancer: sorting the good from the bad. Semin. Cancer Biol. 21, 44–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Silkstone D., Hong H., Alman B. A. (2008) β-Catenin in the race to fracture repair: in it to Wnt. Nat. Clin. Pract. Rheumatol. 4, 413–419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Inestrosa N. C., Arenas E. (2010) Emerging roles of Wnts in the adult nervous system. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 11, 77–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Osakada F., Ooto S., Akagi T., Mandai M., Akaike A., Takahashi M. (2007) Wnt signaling promotes regeneration in the retina of adult mammals. J. Neurosci. 27, 4210–4219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Baron R., Kneissel M. (2013) WNT signaling in bone homeostasis and disease: from human mutations to treatments. Nat. Med. 19, 179–192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Anastas J. N., Moon R. T. (2013) WNT signalling pathways as therapeutic targets in cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 13, 11–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Thakur R., Mishra D. P. (2013) Pharmacological modulation of β-catenin and its applications in cancer therapy. J. Cell Mol. Med. 17, 449–456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Corbit K. C., Shyer A. E., Dowdle W. E., Gaulden J., Singla V., Chen M.-H., Chuang P.-T., Reiter J. F. (2008) Kif3a constrains β-catenin-dependent Wnt signalling through dual ciliary and non-ciliary mechanisms. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 70–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Gerdes J. M., Liu Y., Zaghloul N. A., Leitch C. C., Lawson S. S., Kato M., Beachy P. A., Beales P. L., DeMartino G. N., Fisher S., Badano J. L., Katsanis N. (2007) Disruption of the basal body compromises proteasomal function and perturbs intracellular Wnt response. Nat. Genet. 39, 1350–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lancaster M. A., Schroth J., Gleeson J. G. (2011) Subcellular spatial regulation of canonical Wnt signalling at the primary cilium. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 700–707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chilov D., Sinjushina N., Rita H., Taketo M. M., Mäkelä T. P., Partanen J. (2011) Phosphorylated β-catenin localizes to centrosomes of neuronal progenitors and is required for cell polarity and neurogenesis in developing midbrain. Dev. Biol. 357, 259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fumoto K., Kadono M., Izumi N., Kikuchi A. (2009) Axin localizes to the centrosome and is involved in microtubule nucleation. EMBO Rep. 10, 606–613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Greer Y. E., Rubin J. S. (2011) Casein kinase 1 Δ functions at the centrosome to mediate Wnt-3a-dependent neurite outgrowth. J. Cell Biol. 192, 993–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chitalia V. C., Foy R. L., Bachschmid M. M., Zeng L., Panchenko M. V., Zhou M. I., Bharti A., Seldin D. C., Lecker S. H., Dominguez I., Cohen H. T. (2008) Jade-1 inhibits Wnt signalling by ubiquitylating β-catenin and mediates Wnt pathway inhibition by pVHL. Nat. Cell Biol. 10, 1208–1216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Borgal L., Habbig S., Hatzold J., Liebau M. C., Dafinger C., Sacarea I., Hammerschmidt M., Benzing T., Schermer B. (2012) The ciliary protein nephrocystin-4 translocates the canonical Wnt regulator Jade-1 to the nucleus to negatively regulate β-catenin signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25370–25380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Liu J., Carvalho L. P., Bhattacharya S., Carbone C. J., Kumar K. G., Leu N. A., Yau P. M., Donald R. G., Weiss M. J., Baker D. P., McLaughlin K. J., Scott P., Fuchs S. Y. (2009) Mammalian casein kinase 1α and its leishmanial ortholog regulate stability of IFNAR1 and type I interferon signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 29, 6401–6412 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen L., Li C., Pan Y., Chen J. (2005) Regulation of p53-MDMX interaction by casein kinase 1 α. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 6509–6520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Habbig S., Bartram M. P., Müller R. U., Schwarz R., Andriopoulos N., Chen S., Sägmüller J. G., Hoehne M., Burst V., Liebau M. C., Reinhardt H. C., Benzing T., Schermer B. (2011) NPHP4, a cilia-associated protein, negatively regulates the Hippo pathway. J. Cell Biol. 193, 633–642 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Benzing T., Gerke P., Höpker K., Hildebrandt F., Kim E., Walz G. (2001) Nephrocystin interacts with Pyk2, p130(Cas), and tensin and triggers phosphorylation of Pyk2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 9784–9789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schermer B., Höpker K., Omran H., Ghenoiu C., Fliegauf M., Fekete A., Horvath J., Köttgen M., Hackl M., Zschiedrich S., Huber T. B., Kramer-Zucker A., Zentgraf H., Blaukat A., Walz G., Benzing T. (2005) Phosphorylation by casein kinase 2 induces PACS-1 binding of nephrocystin and targeting to cilia. EMBO J. 24, 4415–4424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Choo Y. S., Zhang Z. (2009) Detection of protein ubiquitination. J. Vis. Exp. 30, 1293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Rena G., Bain J., Elliott M., Cohen P. (2004) D4476, a cell-permeant inhibitor of CK1, suppresses the site-specific phosphorylation and nuclear exclusion of FOXO1a. EMBO Rep. 5, 60–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rinschen M. M., Yu M.-J., Wang G., Boja E. S., Hoffert J. D., Pisitkun T., Knepper M. A. (2010) Quantitative phosphoproteomic analysis reveals vasopressin V2-receptor-dependent signaling pathways in renal collecting duct cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3882–3887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Rinschen M. M., Wu X., König T., Pisitkun T., Hagmann H., Pahmeyer C., Lamkemeyer T., Kohli P., Schnell N., Schermer B., Dryer S., Brooks B. R., Beltrao P., Krueger M., Brinkkoetter P. T., Benzing T. (2014) Phosphoproteomic analysis reveals regulatory mechanisms at the kidney filtration barrier. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 25, 1509–1522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Hoffert J. D., Wang G., Pisitkun T., Shen R.-F., Knepper M. A. (2007) An automated platform for analysis of phosphoproteomic datasets: application to kidney collecting duct phosphoproteins. J. Proteome Res. 6, 3501–3508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Wang G., Wu W. W., Pisitkun T., Hoffert J. D., Knepper M. A., Shen R.-F. (2006) Automated quantification tool for high-throughput proteomics using stable isotope labeling and LC-MSn. Anal. Chem. 78, 5752–5761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cox J., Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cox J., Hein M. Y., Luber C. A., Paron I., Nagaraj N., Mann M. (2014) MaxLFQ allows accurate proteome-wide label-free quantification by delayed normalization and maximal peptide ratio extraction. Mol. Cell Proteomics mcp.M113.031591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hoff S., Halbritter J., Epting D., Frank V., Nguyen T.-M. T., van Reeuwijk J., Boehlke C., Schell C., Yasunaga T., Helmstädter M., Mergen M., Filhol E., Boldt K., Horn N., Ueffing M., Otto E. A., Eisenberger T., Elting M. W., van Wijk J. A., Bockenhauer D., Sebire N. J., Rittig S., Vyberg M., Ring T., Pohl M., Pape L., Neuhaus T. J., Elshakhs N. A., Koon S. J., Harris P. C., Grahammer F., Huber T. B., Kuehn E. W., Kramer-Zucker A., Bolz H. J., Roepman R., Saunier S., Walz G., Hildebrandt F., Bergmann C., Lienkamp S. S. (2013) ANKS6 is a central component of a nephronophthisis module linking NEK8 to INVS and NPHP3. Nat. Genet. 45, 951–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Flotow H., Graves P. R., Wang A. Q., Fiol C. J., Roeske R. W., Roach P. J. (1990) Phosphate groups as substrate determinants for casein kinase I action. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 14264–14269 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Meggio F., Perich J. W., Reynolds E. C., Pinna L. A. (1991) A synthetic β-casein phosphopeptide and analogues as model substrates for casein kinase-1, a ubiquitous, phosphate directed protein kinase. FEBS Lett. 283, 303–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Marin O., Meggio F., Sarno S., Andretta M., Pinna L. A. (1994) Phosphorylation of synthetic fragments of inhibitor-2 of protein phosphatase-1 by casein kinase-1 and -2: evidence that phosphorylated residues are not strictly required for efficient targeting by casein kinase-1. Eur. J. Biochem. 223, 647–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Pulgar V., Marin O., Meggio F., Allende C. C., Allende J. E., Pinna L. A. (1999) Optimal sequences for non-phosphate-directed phosphorylation by protein kinase CK1 (casein kinase-1): a re-evaluation. Eur. J. Biochem. 260, 520–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Marin O., Bustos V. H., Cesaro L., Meggio F., Pagano M. A., Antonelli M., Allende C. C., Pinna L. A., Allende J. E. (2003) A noncanonical sequence phosphorylated by casein kinase 1 in β-catenin may play a role in casein kinase 1 targeting of important signaling proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 10193–10200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ferrarese A., Marin O., Bustos V. H., Venerando A., Antonelli M., Allende J. E., Pinna L. A. (2007) Chemical dissection of the APC repeat 3 multistep phosphorylation by the concerted action of protein kinases CK1 and GSK3. Biochemistry 46, 11902–11910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Nagaraj N., D'Souza R. C., Cox J., Olsen J. V., Mann M. (2010) Feasibility of large-scale phosphoproteomics with higher energy collisional dissociation fragmentation. J. Proteome Res. 9, 6786–6794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Del Valle-Pérez B., Arqués O., Vinyoles M., de Herreros A. G., Duñach M. (2011) Coordinated action of CK1 isoforms in canonical Wnt signaling. Mol. Cell Biol. 31, 2877–2888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Peters J. M., McKay R. M., McKay J. P., Graff J. M. (1999) Casein kinase I transduces Wnt signals. Nature 401, 345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Li V. S., Ng S. S., Boersema P. J., Low T. Y., Karthaus W. R., Gerlach J. P., Mohammed S., Heck A. J., Maurice M. M., Mahmoudi T., Clevers H. (2012) Wnt signaling through inhibition of β-catenin degradation in an intact Axin1 complex. Cell 149, 1245–1256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dale T. (2006) Kinase cogs go forward and reverse in the Wnt signaling machine. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 13, 9–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zeng X., Tamai K., Doble B., Li S., Huang H., Habas R., Okamura H., Woodgett J., He X. (2005) A dual-kinase mechanism for Wnt co-receptor phosphorylation and activation. Nature 438, 873–877 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Brockman J. L., Gross S. D., Sussman M. R., Anderson R. A. (1992) Cell cycle-dependent localization of casein kinase I to mitotic spindles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 89, 9454–9458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Mollet G., Silbermann F., Delous M., Salomon R., Antignac C., Saunier S. (2005) Characterization of the nephrocystin/nephrocystin-4 complex and subcellular localization of nephrocystin-4 to primary cilia and centrosomes. Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 645–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Delous M., Hellman N. E., Gaudé H.-M., Silbermann F., Le Bivic A., Salomon R., Antignac C., Saunier S. (2009) Nephrocystin-1 and nephrocystin-4 are required for epithelial morphogenesis and associate with PALS1/PATJ and Par6. Hum. Mol. Genet. 18, 4711–4723 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Goentoro L., Kirschner M. W. (2009) Evidence that fold-change, and not absolute level, of β-catenin dictates Wnt signaling. Mol. Cell 36, 872–884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Niida A., Hiroko T., Kasai M., Furukawa Y., Nakamura Y., Suzuki Y., Sugano S., Akiyama T. (2004) DKK1, a negative regulator of Wnt signaling, is a target of the β-catenin/TCF pathway. Oncogene 23, 8520–8526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. González-Sancho J. M., Aguilera O., García J. M., Pendás-Franco N., Peña C., Cal S., García de Herreros A., Bonilla F., Muñoz A. (2005) The Wnt antagonist DICKKOPF-1 gene is a downstream target of β-catenin/TCF and is downregulated in human colon cancer. Oncogene 24, 1098–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lustig B., Jerchow B., Sachs M., Weiler S., Pietsch T., Karsten U., van de Wetering M., Clevers H., Schlag P. M., Birchmeier W., Behrens J. (2002) Negative feedback loop of Wnt signaling through upregulation of conductin/axin2 in colorectal and liver tumors. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 1184–1193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Jho E. H., Zhang T., Domon C., Joo C.-K., Freund J.-N., Costantini F. (2002) Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf signaling induces the transcription of Axin2, a negative regulator of the signaling pathway. Mol. Cell Biol. 22, 1172–1183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ha N.-C., Tonozuka T., Stamos J. L., Choi H.-J., Weis W. I. (2004) Mechanism of phosphorylation-dependent binding of APC to β-catenin and its role in beta-catenin degradation. Mol. Cell 15, 511–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Nieuwkoop P. D., Faber J. (eds) (1994) Normal Table of Xenopus laevis (Daudin), Garland Publishing Inc., New York [Google Scholar]