Abstract

Background

Vitamin D deficiency may be associated with an increased risk of asthma.

Objective

We studied the association between 25-hydroxy (25-OH) vitamin D deficiency and asthma prevalence in two Peruvian populations close to the equator but with disparate degrees of urbanization.

Methods

We conducted a population-based study in 1441 children in two communities in Peru, of which 1134 (79%) provided a blood sample for 25-OH vitamin D analysis.

Results

In these 1134 children, mean age was 14.8 years; 52% were boys; asthma and atopy prevalence were 12% in Lima vs. 3% in Tumbes (p<0.001) and 59% in Lima vs. 41% in Tumbes (p<0.001), respectively; and, mean 25-OH vitamin D was 20.8 ng/mL in Lima vs. 30.1 ng/mL in Tumbes (p<0.001). Prevalence of 25-OH vitamin D deficiency (<20 ng/mL) was 47% in Lima vs. 7% in Tumbes (p<0.001). In multivariable logistic regression, we found that lower 25-OH vitamin D levels were associated with an increased odds of asthma (OR = 1.7 per each 10 ng/mL decrease in 25-OH vitamin D levels, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.6; p<0.01). In stratified analyses, the association between lower 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma was limited to children with atopy (OR=2.2, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.6) and not in those without atopy (OR=0.9, 95% CI 0.5 to 2.0). We did not find associations between 25-OH vitamin D levels and other clinical biomarkers for asthma, including exhaled nitric oxide, total serum IgE and pulmonary function.

Conclusion and Clinical Relevance

Both asthma and 25-OH vitamin D deficiency were common among children living in Lima (latitude=12.0°S) but not among those in Tumbes (3.6°S). The relationship between 25-OH vitamin D deficiency and asthma was similar in both sites and was limited among children with atopy. Future supplementation trials may need to consider stratification by atopy at the time of design.

INTRODUCTION

Asthma is a chronic lung disease that is associated with airway inflammation, airflow limitation, bronchial hyper-responsiveness and symptoms of episodic wheeze and cough. Asthma prevalence has increased rapidly over the past several decades worldwide and has emerged as one of the most prevalent non-communicable diseases. Asthma currently affects 300 million individuals worldwide and is responsible for 180 thousand deaths and 15 million DALYs lost each year (1, 2). Asthma is a public health problem not just in high-income countries, but also in low and lower-middle income countries where over 80% of asthma-related deaths occur (3).

The role of micronutrient deficiencies in the etiology of asthma has gained considerable attention in recent years (4–6). There is mounting evidence that vitamin D confers a protective effect against asthma risk and severity; however, evidence for an important relationship remains controversial (7). First, vitamin D supplementation early in childhood may be associated with increased allergy and asthma (8). Second, a recent analysis of a population-based study in the United States and of a cohort of inner-city adolescents with asthma managed prospectively with guidelines-based therapy in the Asthma Control Evaluation did not find an association between vitamin D and asthma (9), Finally, several cross-sectional studies have demonstrated an association between vitamin D deficiency and risk of asthma (10–18) and plasma concentrations of vitamin D may influence the effect of inhaled corticosteroids on lung function and airway responsiveness (19). Studies also suggest a link between lower maternal vitamin D intake and higher risk of wheezing, allergic rhinitis, and eczema in childhood (20–24). Vitamin D may also play a role in asthma severity. One study in Costa Rica demonstrated that lower levels of serum vitamin D were associated with higher eosinophil count, total serum IgE and increased airway responsiveness in asthmatic children, while higher vitamin D levels were associated with decreased odds of hospitalization and use of anti-inflammatory medications in the previous year (10). In a multi-center study in the United States, vitamin D insufficiency (<30 ng/ml) was predictive of severe asthma exacerbations (13). Randomized clinical trials of vitamin D supplementation for asthma prevention and control are underway and will lead insights into the relationship between vitamin D and asthma (25).

Vitamin D deficiency is hypothesized to affect asthma through a variety of mechanisms. Vitamin D deficiency may weaken immunological defenses against respiratory infections, which in turn could trigger asthma exacerbations (26). Vitamin D deficiency may also affect lung development and function (27–29). Vitamin D has also been implicated in airway remodeling, and may influence the efficacy of anti-inflammatory treatments (30). Moreover, vitamin D stimulates innate immunity by enhancing bacterial killing and modulates adaptive immunity to minimize inflammation and autoimmune disease (31). Finally, vitamin D may also confer protection against allergic sensitization and deficiency may lead to abnormalities in the allergic immune response which in turn may increase asthma risk (32).

We sought to quantify 25-hydroxy (25-OH) vitamin D levels in a cohort of Peruvian children and determine the association with asthma prevalence, pulmonary function and biomarkers for asthma. Since there is a current knowledge gap in factors that may affect relationship between vitamin D and asthma, we explored the relationship between 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma stratified by atopic status.

METHODS

Study design

The study design is described in detail elsewhere (33, 34). Briefly, we conducted a population-based, cross-sectional study of asthma prevalence in two regions in Peru. In December 2008, we selected a random sample of children aged 13–15 years from a community census and visited them for enrollment between April 2009 and December 2010. A total of 1441 children were enrolled (33, 34). The first site was Lima (latitude 12.0°S), the highly urbanized capital of Peru located at sea level and with a population of >10 million. We conducted our study in Pampas de San Juan de Miraflores, a peri-urban shanty-town. The second site was rural Tumbes (latitude 3°S), also at sea level, located in northern Peru. Summer months in Peru occur between December to March, and winter months between June to September. Average ambient temperature in Lima ranges between 17°C and 30°C year-round, and relative humidity ranges between 55% and 80%. Annual precipitation in Lima is 50 mm per year. Average ambient temperature in Tumbes ranges between 25°C and 33°C, relative humidity ranges between 55% and 80% and precipitation is much higher, with annual rainfall up to 2200 mm per year.

We asked participants and their caregivers about asthma and allergy symptoms using a previously validated Spanish version of the ISAAC study (35), sociodemographics and environmental exposures, collected anthropometry, a blood sample, and conducted allergy skin test, fractional exhaled nitric oxide (FeNO) test and spirometry before and after bronchodilators. We conducted spirometry according to ATS/ERS guidelines (36) with the portable SpiroPro (Jaeger, Hoechberg, Germany). We used the handheld NIOXMINO (Aerocrine, Solna, Sweden) to measure FeNO. We performed allergy tests with the Multi-Test II (Lincoln Diagnostics, Decatur, USA) using 10 common household allergens (cockroach, a mix of 2 dust mites, cat hair, dog epithelium, mouse epithelium and a mix of 4 molds). Serum samples were processed for vitamin D levels in duplicate using the LIAISON 25-OH vitamin D total assay (DiaSorin Inc., Stillwater, MN). Previous reports have found single determinations of 25-OH vitamin D are reproducible and hence are a relatively good index of deficiency (37). The Ethics Committees of A.B. PRISMA in Lima, Peru, and Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore, USA, approved conduct of this study.

Definitions

We defined asthma as wheeze or use of asthma medications in the last 12 months; atopy as a positive skin response to any allergen specificities tested in our study (33); and, 25-OH vitamin D deficiency as a level <20 ng/mL and vitamin D insufficiency as a level <30 ng/mL. We further categorized 25-OH vitamin D level (4.32–19.6, 19.7–24.0, 24.1–29.8 and 29.9–77.4) and BMI (13.9–18.9, 19–20.5, 20.6–22.7 and 22.8–39.3) into quartiles for analysis. We calculated percent predicted values for forced expiratory volumes and FEV1/FVC using a mixed ethnic population reference (38).

Biostatistical methods

We used chi-square tests or Fisher exact tests to compare proportions between subgroups, and t-tests (for 2 groups) or analysis of variance (for 3 or more groups) to compare means between subgroups, as appropriate. We used multivariable linear regressions for the entire cohort and stratified by site to identify variables associated with 25-OH vitamin D level in our study population. We included all important covariates identified in this stage (i.e., BMI, sex, household income, personal history of tobacco smoke, site and calendar quarter at the time of blood draw) to adjust for potential confounding in subsequent analyses. We used multivariable logistic regression to model the association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma in the entire cohort adjusted for BMI, sex, household income, personal history of tobacco smoke, site and calendar month at the time of blood draw. We do not control for atopy in our regression models because 25-OH vitamin D may be in the causal pathway between atopy and asthma. Instead, we stratified our analysis by atopic status (i.e., separate regressions for atopics and non-atopics, respectively). We used penalized logistic regression to address small sample sizes when appropriate (39). We also stratified our analysis of 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma by site. We then tested for an interaction effect between 25-OH vitamin D level and site to determine if the relationship between asthma prevalence and 25-OH vitamin D levels by site was heterogeneous. In the subset of non-asthmatics, we used multivariable logistic regression to model the association between 25-OH vitamin D insufficiency and atopy in the entire cohort adjusted for BMI, sex, household income, personal history of tobacco smoke, site and calendar month at the time of blood draw. We used multivariable linear regression to model the association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and either pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC or percent predicted FEV1 (%FEV1) for the entire cohort and stratified by site. We log-transformed FeNO and total serum IgE values for analyses, and used multivariable linear regressions to model the association with 25-OH vitamin D levels for the entire cohort and also stratified by site. We conducted all analyses in R (www.r-project.org).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study population

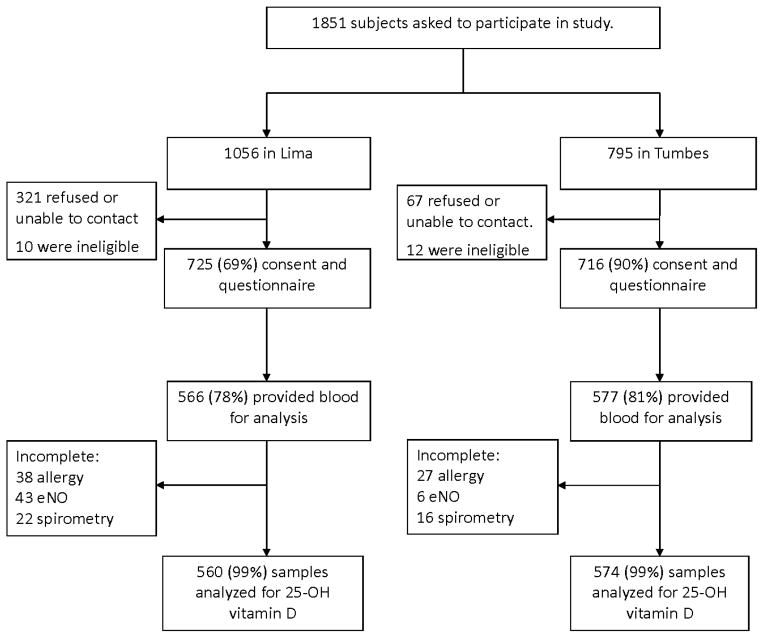

Of 1441 children who were enrolled into the study, 1134 (79%) had blood available for 25-OH vitamin D analysis (Figure 1). There were no differences observed in age (p=0.96), sex (p=0.64), prevalence of asthma (p=0.61) or atopy (p=0.09), pre-FEV1/FVC (p=0.78), exhaled nitric oxide (p=0.30), body mass index (p=0.42), income (p=0.57) maternal education (p=0.67), and site (p=0.20) between participants with and without a blood sample for 25-OH vitamin D analysis. Among the 1134 children, mean age at enrollment was 14.8 years (SD=0.9), 52% were boys, 49% lived in Lima, average height was 162 cm (SD=8) in boys and 153 cm (SD=6) in girls (p<0.001 after adjusting for site differences) and average BMI was 20.6 kg/m2 (SD=3.0) in boys and 21.8 kg/m2 (SD=3.3) in girls (p<0.001 after adjusting for site differences). The prevalence of atopy was 59% in Lima and 41% in Tumbes (p<0.001). The prevalence of asthma was 12% (69/560) in Lima and 3% (17/574) in Tumbes (p<0.001).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of recruitment, questionnaires and procedures in Lima and Tumbes, Peru; 2009 –2010.

Distribution and predictors of 25-OH vitamin D levels in our study population

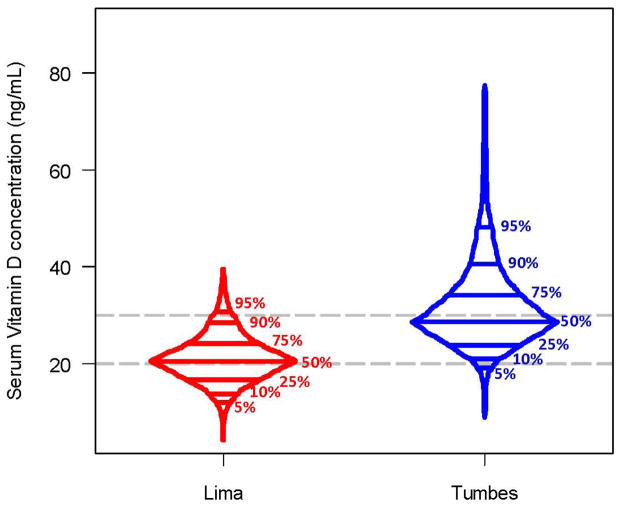

Average 25-OH vitamin D level in our study population was 25.5 ng/mL (SD=8.9). Of the 1134 children, 26% had 25-OH vitamin D deficiency and 75% met criteria for 25-OH vitamin D insufficiency. There were important differences in 25-OH vitamin D levels by study site (Figure 2). Children who lived in Lima had an average level of 20.8 ng/mL (range 4.3–39.5 ng/mL), whereas those who lived in Tumbes had an average level of 30.1 ng/mL (range 8.9–77.4 ng/mL; p<0.001 between sites). The prevalence of 25-OH vitamin D deficiency was 47% in Lima and 7% of children in Tumbes (p<0.001).

Figure 2. Box-percentile plots of the distribution of serum 25-OH vitamin D levels in two Peruvian populations; 2009–2010.

We display the distribution and percentiles (5%, 10%, 25%, 50%, 75%, 90%, 95%) of serum vitamin D levels stratified by study site.

We summarize single variable associations between possible predictors and 25-OH vitamin D levels by study site in Table 1. BMI was not associated with lower levels of 25 OH vitamin D (Online Supplement, e-Figure 1). We found an association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and BMI in Lima (−2.1 ng/mL per 10 kg/m2 increase in BMI; p<0.01) but not in Tumbes (p=0.88). Other variables that were associated with 25-OH vitamin D level include site (9.2 ng/mL higher in children who live in Tumbes vs. Lima; p<0.001), sex (2.6 ng/mL lower in girls vs. boys; p<0.001), personal history of tobacco smoke (2.4 ng/mL higher in smokers vs. nonsmokers; p=0.03) and calendar quarter at time of blood draw (p<0.001). When stratified by site, low household income (<175 USD/month) was associated with having a higher 25-OH vitamin D level in Tumbes (1.7 ng/mL vs. a higher household income; p=0.04).

Table 1.

Predictors of serum 25-OH vitamin D levels in two Peruvian populations; 2009–2010.

| 25-OH vitamin D concentration (ng/mL) in Lima | 25-OH vitamin D concentration (ng/mL) in Tumbes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | 20 – 29 | ≥30 | P | <20 | 20 – 29 | ≥30 | P | |

| Sample size | 263 | 258 | 39 | 39 | 296 | 239 | ||

| Demographics | ||||||||

| Age in years, mean (SD) | 14.8 (0.9) | 14.9 (0.9) | 15.0 (0.8) | 0.50 | 14.6 (0.8) | 14.9 (0.9) | 14.9 (0.9) | 0.08 |

| n, (%) boys | 123 (47%) | 136 (53%) | 22 (56%) | 0.29 | 11 (72%) | 134 (55%) | 166 (31%) | <0.001 |

| Height in cm, mean (SD) | 156.6 (7.3) | 157.6 (8.4) | 159.2 (9.2) | 0.09 | 157.2 (8.1) | 158.3 (7.4) | 160.9 (9.0) | <0.001 |

| BMI in kg/m2, mean (SD) | 22.1 (3.7) | 21.6 (3.1) | 20.7 (2.1) | 0.02 | 21.4 (3.5) | 20.6 (3.0) | 20.4 (2.7) | 0.15 |

| Socioeconomics, n (%) | ||||||||

| Income <175 USD | 66 (25%) | 69 (27%) | 12 (31%) | 0.73 | 31 (80%) | 190 (64%) | 135 (57%) | 0.01 |

| Maternal education >≥6 years | 195 (75%) | 194 (78%) | 35 (89%) | 0.11 | 20 (51%) | 210 (73%) | 167 (71%) | 0.02 |

| 6 or more household members | 137 (52%) | 123 (48%) | 21 (54%) | 0.54 | 11 (34%) | 63 (29%) | 46 (24%) | 0.39 |

| Electricity 24 hours | 262 (99%) | 256 (99%) | 39 (100%) | 0.69 | 36 (92%) | 259 (88%) | 208 (87%) | 0.72 |

| Private sanitation | 245 (93%) | 238 (92%) | 37 (95%) | 0.81 | 9 (23%) | 82 (27%) | 75 (31%) | 0.46 |

| Exposures | ||||||||

| Personal history of smoking | 7 (3%) | 22 (9%) | 6 (15%) | <0.001 | 0 (0%) | 4 (2%) | 7 (3%) | 0.36 |

| Second hand smoke | 39 (15%) | 48 (19%) | 4 (10%) | 0.32 | 8 (21%) | 68 (23%) | 56 (23%) | 0.92 |

| Calendar quarter at time of blood draw, n, (%) | ||||||||

| January – March | 17 (7%) | 35 (14%) | 9 (23%) | <0.001 | 1 (2%) | 9 (3%) | 13 (5%) | <0.001 |

| April – June | 36 (13%) | 84 (32%) | 18 (46%) | 15 (39%) | 48 (16%) | 75 (31%) | ||

| July – September | 152 (58%) | 83 (32%) | 3 (8%) | 12 (31%) | 92 (31%) | 54 (23%) | ||

| October – December | 58 (22%) | 56 (22%) | 9 (23%) | 11 (28%) | 147 (50%) | 97 (41%) | ||

We also summarize single variable associations between asthma and allergy outcomes and 25-OH vitamin D levels by study site in Table 2. Single variable analyses suggested a positive relationship between 25-OH vitamin D levels and atopy; however, in multivariable logistic regression we did not find an important relationship between 25-OH vitamin D levels and atopy (p=0.54) in the subset of non-asthmatics. In analyses stratified by site, we did not find an important relationship between 25-OH vitamin D levels and atopy in either Lima (p=0.14) or Tumbes (p=0.82).

Table 2.

Single variable analysis of the association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and multiple asthma and allergy outcomes in two Peruvian populations; 2009–2010.

| 25-OH vitamin D concentration (ng/mL) in Lima | 25-OH vitamin D concentration (ng/mL) in Tumbes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <20 | 20 – 29 | ≥30 | P | <20 | 20 – 29 | ≥30 | P | |

| Number of children with vitamin D levels | 263 | 258 | 39 | 39 | 296 | 239 | ||

| Number of children with current asthma symptoms/Total (%) | 37/263 (14%) | 29/258 (11%) | 3/39 (8%) | 0.47 | 0/39 | 12/296 (4%) | 5/239 (2%) | 0.28 |

| Number of children with atopy/Total tested (%) | 124/248 (50%) | 139/239 (58%) | 25/35 (71%) | 0.03 | 14/38 (37%) | 103/285 (36%) | 86/224 (38%) | 0.87 |

| Exhaled nitric oxide (ppb), geometric mean (geometric SD) | 15.5 (2.1) | 14.9 (2.1) | 16.6 (2.0) | 0.65 | 10.3 (1.9) | 12.8 (2.0) | 12.8 (2.0) | 0.18 |

| Total serum IgE, geometric mean (geometric SD) | 300 (3.7) | 228 (4.0) | 262 (4.4) | 0.07 | 141 (3.7) | 196 (3.3) | 198 (3.6) | 0.28 |

| Pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC, mean (SD) | 88.6% (6.1%) | 88.7% (6.7%) | 89.5% (4.6%) | 0.72 | 90.9% (6.1%) | 91.1% (5.6%) | 90.4% (6.2%) | 0.39 |

| % FEV1, mean (SD) | 120% (14%) | 119% (14%) | 117% (14%) | 0.39 | 107% (14%) | 105% (13%) | 105% (14%) | 0.70 |

25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma

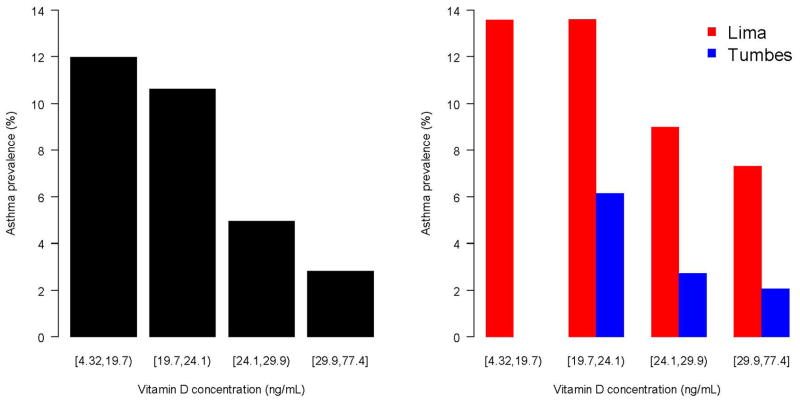

A higher prevalence of asthma was associated with lower 25-OH vitamin D levels for the overall cohort and when stratified by site (Figure 3). In unadjusted analysis, children with 25-OH vitamin D deficiency were about five times more likely to have asthma vs. those with normal levels of 25-OH vitamin D (OR=4.7, 95% CI 2.2 to 10.3); and, children who met criteria for insufficiency but not deficiency (20–29 ng/mL) were about three times more likely to have asthma vs. those with normal levels of 25-OH vitamin D (OR=2.7, 95% CI 1.2 to 5.8). There were too few children in Tumbes with either 25-OH vitamin D deficiency or asthma to conduct an analysis of 25-OH vitamin D deficiency and asthma stratified by site. Hence, we conducted an adjusted analysis using continuous values of 25-OH vitamin D levels instead. In multivariable logistic regression, we found that lower 25-OH vitamin D levels were associated with an increased odds of asthma (OR = 1.7 per each 10 ng/mL decrease in 25-OH vitamin D levels, 95% CI 1.2 to 2.6; p<0.01) after adjusting for BMI, sex, personal history of tobacco smoke, low household income, site and calendar quarter at the time of blood draw. When stratified by site, we found that lower 25-OH vitamin D levels were associated with an increased odds of asthma in Lima (OR=1.8, 95% CI 1.1 to 3.8; p=0.02); in Tumbes, we found an effect size similar in magnitude and direction that was marginally significant likely because of the few numbers of asthmatics at this site (OR=1.7, 95% CI 0.9 to 3.4; p=0.12). Moreover, we did not find an interaction between 25-OH vitamin D levels and site on asthma prevalence (p=0.61), suggesting that the relationship between asthma prevalence and vitamin D levels was homogenous across sites. When stratified by atopic status (Table 3), lower 25-OH vitamin D levels were associated with an increased odds of asthma in children with atopy (OR=2.2 per each 10 ng/mL decrease in 25-OH vitamin D levels, 95% CI 1.3 to 3.6; p<0.01) but not in those without atopy (OR=0.9, 95% CI 0.5 to 2.0; p=0.87). We present sample size and distributions of risk factors included in this analysis stratified by asthma and atopy status in the Online Supplement (e-Table 1).

Figure 3. Relationship between serum 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma prevalence in two Peruvian populations; 2009–2010.

Left panel displays a barplot to describe the relationship between asthma prevalence and quartiles of vitamin D levels in the entire cohort. The right panel displays asthma prevalence by quartiles vitamin D levels stratified by site (Lima in red, Tumbes in blue).

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis of the association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma in two Peruvian populations; 2009–2010.

| Atopy (n=584) | Without atopy (n=660) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single variable OR (95% CI) |

Multivariable OR (95% CI) |

Single variable OR (95% CI) |

Multivariable OR (95% CI) |

|

| Per 10 ng/mL decrease in vitamin D levels | 2.5 (1.6 to 3.8) | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.6) | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.5) | 0.9 (0.5 to 2.0) |

| Blood drawn in 1st quarter | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Blood drawn in 2nd quarter | 1.0 (0.4 to 3.1) | 1.5 (0.5 to 4.8) | 1.3 (0.6 to 3.2) | 0.5 (0.1 to 3.8) |

| Blood drawn in 3rd quarter | 0.6 (0.2 to 2.1) | 0.6 (0.2 to 2.0) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.8) | 0.5 (0.1 to 3.1) |

| Blood drawn in 4th quarter | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.9) | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.6) | 0.7 (0.3 to 1.7) | 1.0 (0.2 to 5.7) |

| Sex (male is reference) | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.4) | 0.5 (0.3 to 1.0) | 1.3 (0.6 to 3.1) | 1.3 (0.5 to 3.2) |

| Income < 175 USD | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.7) | 0.5 (0.2 to 1.1) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.1) |

| Personal history of smoking | 1.8 (0.6 to 4.3) | 1.8 (0.5 to 5.7) | 1.0 (0.1 to 5.1) | 1.6 (0.2 to 7.9) |

| BMI, in kg/m2 | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | 1.2 (1.1 to 1.3) | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.3) |

| Site (Lima is reference) | 4.2 (2.2 to 8.6) | 2.3 (1.0 to 6.0) | 2.8 (1.3 to 6.7) | 1.7 (0.5 to 6.0) |

25-OH vitamin D levels and pulmonary function

A total of 1096 children had both pre-bronchodilator spirometry and 25-OH vitamin D levels available for analysis. Children in Lima had a lower pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC than did children in Tumbes (89% vs. 91%), and this difference persisted even adjustment by age, sex, and height (2% higher in children from Tumbes; p<0.001). Children with 25-OH vitamin D deficiency had a lower pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC vs. children who were not deficient (89% vs. 90%; p<0.01); however, when stratified by site this difference was no longer apparent in either Lima (89% vs. 89%; p=0.67) or Tumbes (91% vs. 91%; p=0.87). In multivariable linear regression, we did not find an association between pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC and 25-OH vitamin D levels in the overall cohort (p=0.64) and when stratified by site (p=0.80 for Lima and p=0.93 for Tumbes). Children in Lima had a greater %FEV1 than did children in Tumbes (119% vs. 105%) and this difference remained important in multivariable linear regression (12% higher in Lima vs. Tumbes; p<0.001). We did not identify an important association between %FEV1 and with 25-OH vitamin D level in the overall cohort (p=0.59) or when stratified by site (p=0.69 for Lima and p=0.55 for Tumbes). We also did not find an association between %FEV1 and 25-OH vitamin D levels among the subset of asthmatics (p=0.11).

25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma biomarkers

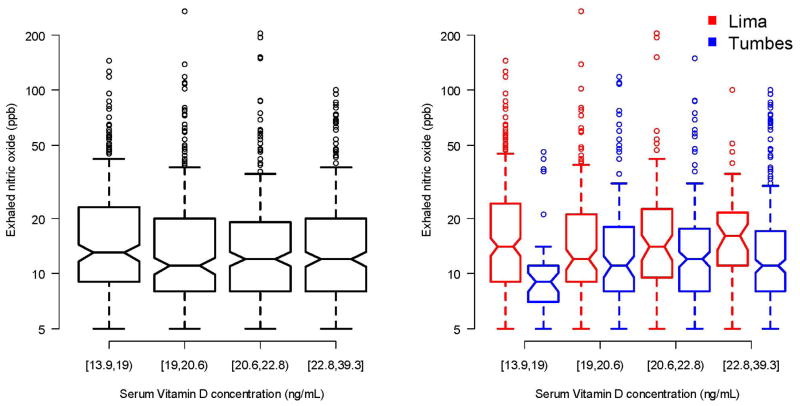

Mean FeNO was 19.3 ppb (SD=22) and the geometric mean for total serum IgE was 224 kU/L (geometric SD=3.7). Children in Lima had a higher mean FeNO than did children in Tumbes (21 ppb vs. 17 ppb; p<0.001), and they also had a higher geometric mean for total serum IgE (262 vs. 192 kU/L; p<0.001). We did not find a relationship between 25-OH vitamin D level and FeNO in the entire cohort or when stratified by site (Figure 4). Specifically, 25-OH vitamin D levels were not associated with FeNO in single variable analysis (p=0.28) or in multivariable analysis (p=0.78). We also did not find an association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and FeNO in the subset of children with asthma (p=0.38). Finally, we did not find an association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and FeNO among children with atopy (p=0.26) or without atopy (p=0.30).

Figure 4. Relationship between serum 25-OH vitamin D levels and exhaled nitric oxide levels in two Peruvian populations; 2009–2010.

Left panel displays a barplot to describe the relationship between exhaled nitric oxide and quartiles of vitamin D levels in the entire cohort. The right panel displays exhaled nitric oxide by quartiles vitamin D levels stratified by site (Lima in red, Tumbes in blue).

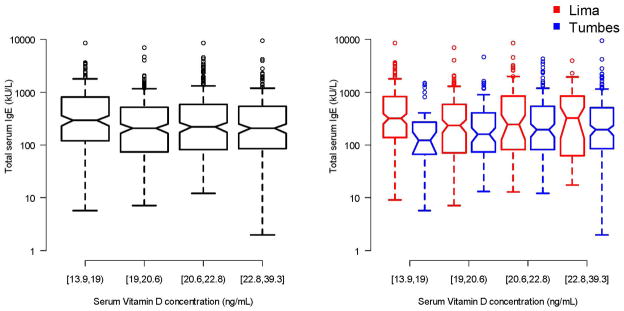

We did not find a relationship between 25-OH vitamin D level and total serum IgE in the entire cohort or when stratified by site (Figure 5). Specifically, 25-OH vitamin D levels were not associated with total serum IgE in multivariable analysis (p=0.25) or when restricted to the subset of children with asthma (p=0.24).

Figure 5. Relationship between serum 25-OH vitamin D levels and total serum IgE in two Peruvian populations; 2009–2010.

Left panel displays a barplot to describe the relationship between total serum IgE and quartiles of vitamin D levels in the entire cohort. The right panel displays exhaled total serum IgE by quartiles vitamin D levels stratified by site (Lima in red, Tumbes in blue).

DISCUSSION

The results of our study provides further evidence that a high prevalence of 25-OH vitamin D deficiency can occur in populations close to the equator; however, our data also indicate that this may be a problem predominantly found among children living in an urban environment. Indeed, lifestyle changes associated with urbanization may lead to a higher prevalence of being overweight or less time spent outdoors which in turn can be associated with being 25-OH vitamin D deficient. The prevalence of asthma was higher among children living in Lima, who also happened to have a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, than among children living in Tumbes. These findings suggest an ecological relationship between asthma prevalence and 25-OH vitamin D deficiency. Finally, lower 25-OH vitamin D levels were associated with a higher asthma prevalence in multivariable analysis. This association appeared to be similar between sites and, more importantly, was limited to children with atopy. The latter is a novel finding with potentially important clinical implications, and suggests that future supplementation trials of 25-OH vitamin D for asthma may need to consider stratification by atopy at the time of design. However, we did not find associations between 25-OH vitamin D and other clinical biomarkers for asthma, including exhaled nitric oxide, total serum IgE and pulmonary function.

Our study was in agreement with the study in Costa Rica (10) that did not find an association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and pulmonary function (FEV1/FVC or %FEV1), even when stratified by asthma status. In contrast, a study in Puerto Rico found an association between 25-OH vitamin D insufficiency and pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC among asthmatics (16). One possibility for a lack of association in our current study is that the number of asthmatics in our analysis (n=86) is low, and a study with a larger number of asthmatics in our study population may be required to verify our findings. Furthermore, our study did not find any relationship between 25-OH vitamin D levels and other asthma biomarkers, including exhaled nitric oxide and total serum IgE; however, it is important to note that both of these biomarkers have a poor positive predictive value for the diagnosis of asthma. Other potential reasons for these difference is that our sample size of children with asthma is smaller than previous studies (10, 16), our study is cross-sectional and not longitudinal as the study in Puerto Rico (14), and a much larger percentage of our study population is 25-OH vitamin D insufficient when compared with the studies in either Costa Rica (10) or Puerto Rico (16).

The association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma appear to be limited to those with atopy. Several studies have suggested that vitamin D can protect against allergic sensitization (18, 40–42), and our results potentially confirm the expected association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and current asthma among those with atopy which can be explained by abnormalities in the regulation of the allergic immune responses. This finding differs from the study in Puerto Rico which found that the magnitude of the association between vitamin D and asthma exacerbations was greater among non-atopic asthmatics than in atopic asthmatics; however, asthma exacerbations is a different outcome than asthma prevalence and may help explain differences between our studies. Further studies are needed to better understand the underlying relationship between vitamin D levels, asthma and atopy.

Our study identified several potential risk factors for 25-OH vitamin D deficiency, including a higher body mass index and factors associated with urbanization such as lower income and a personal history of tobacco smoke. It is unclear why a personal history of tobacco smoke may be associated with 25-OH vitamin D levels in our study population, and it may simply be an indicator of wealth or other socioeconomic factors in our study communities.

There are several potential limitations in our study. First, it is a cross-sectional study that limits conclusion to a potential association between 25-OH vitamin D and asthma prevalence. However, one of the strengths of our study is that it is a population-based study which offers other advantages over case-control study design. Second, we did not collect longitudinal data to determine an association between 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma exacerbations. Third, we do not have early life information regarding prematurity, maternal vitamin D status during pregnancy or shortly after birth, or a longitudinal history of respiratory infections all of which can play an important role in the development of asthma in our study community. Fourth, we did not measure sun exposure, and it is very possible that outdoor exposure may be lower in urban vs. rural children. Fifth, our findings could be also explained by reverse causality in the setting of a cross-sectional study, as children with asthma are more likely to spend less time outdoors, therefore have less sun exposure and worse vitamin D status. Sixth, we did not collect information on puberty status, which may affect our findings; however, we expect that the majority of participating children in this study were post-pubertal. Finally, we had an insufficient number of asthmatics especially in Tumbes; however, despite a low sample size we were able to document strong, important relationships between 25-OH vitamin D and asthma prevalence.

In summary, 25-OH vitamin D levels were low in an urban versus rural setting in two equatorial populations and our findings highlight the importance of an urban lifestyle as a risk factor for 25-OH vitamin D deficiency. Asthma prevalence was greatest in the study population with a higher prevalence of 25-OH vitamin D deficiency, suggesting an ecological relationship between 25-OH vitamin D and asthma. However, we did not find associations between 25-OH vitamin D and other clinical biomarkers for asthma, including exhaled nitric oxide, total serum IgE and pulmonary function. Finally, the relationship between 25-OH vitamin D levels and asthma was limited to those with atopy. If validated by other research groups, future supplementation trials of 25-OH vitamin D for asthma may need to consider stratification by atopy at the time of design to resolve the nature of this relationship.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This study was supported in part by a grant from the Nemours Biomedical Research, the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health and Fogarty International Center (Grant R24 TW007988). Nadia Hansel and William Checkley were further supported by a R01 grant from the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES018845). William Checkley was also supported by a K99/R00 Pathway to Independence Award (R00HL096955) from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health and by a contract (HHSN268200900033C) with the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. Colin Robinson was a Fogarty International Clinical Research Scholar during the time of this work and was further supported by Tufts University School of Medicine. Lauren Baumann was supported by a pre-doctoral NIH T35 Training Grant (T35AI065385). Study sponsors played no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributions: All authors were involved in the study design and writing of the manuscript. William Checkley conducted statistical analysis and interpretation, and drafted the manuscript. Colin Robinson and Lauren Baumann share responsibilities in study design and conduct, in data management and participated in the writing of manuscript. Karina Romero was responsible for the study conduct and data management, and also participated in the writing of manuscript. Nadia Hansel, Robert Gilman and Robert Wise contributed to study design, interpretation of results and also participated in writing of this manuscript. Edward Mougey and John Lima were responsible for vitamin D analysis and laboratory quality control, and also participated in writing of the manuscript. Suzanne Pollard contributed to writing of manuscript. William Checkley had ultimate oversight over study design and administration, analysis and writing of this manuscript.

Other PURA study investigators include: Juan Combe MD (A.B. PRISMA, Lima, Peru), Alfonso Gomez MD (A.B. PRISMA, Lima, Peru), Guillermo Gonzalvez MD (PAHO, Lima, Peru), Lilia Cabrera RN (A.B. PRISMA, Lima, Peru), Kathleen Barnes PhD (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA), Patrick Breysse PhD (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA), D’Ann Williams PhD (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA), Robert G Hamilton PhD (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, USA).

References

- 1.Braman SS. The global burden of asthma. Chest. 2006;130:4–12. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1_suppl.4S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bousquet J. The public health implications of asthma. Bull World Health Organ. 2005;83:548–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Masoli M, Fabian D, Holt S, Beasley R. The global burden of asthma: executive summary of the GINA Dissemination Committee report. Allergy. 2004;59(5):469–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00526.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paul G, Brehm JM, Alcorn JF, Holguín F, Aujla SJ, Celedón JC. Vitamin D and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:124–32.A. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1502CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Litonjua AA. Vitamin D deficiency as a risk factor for childhood allergic disease and asthma. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012 Apr;12:179–85.A. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283507927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown SD, Calvert HH, Fitzpatrick AM. Vitamin D and asthma. Dermatoendocrinol. 2012;4:137–45. doi: 10.4161/derm.20434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaheen SO. Vitamin D deficiency and the asthma epidemic. Thorax. 2008;63:293. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.091728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wjst M. Is vitamin D supplementation responsible for the allergy pandemic? Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:257–62. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283535833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gergen PJ, Teach SJ, Mitchell HE, Freishtat RF, Calatroni A, Matsui E, Kattan M, Bloomberg GR, Liu AH, Kercsmar C, O’Connor G, Pongracic J, Rivera-Sanchez Y, Morgan WJ, Sorkness CA, Binkley N, Busse W. Lack of a relation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentrations and asthma in adolescents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97:1228–34. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.046961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brehm JM, Celedón JC, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Hunninghake GM, Forno E, Laskey D, Sylvia JS, Hollis BW, Weiss ST, Litonjua AA. Serum vitamin D levels and markers of severity of childhood asthma in Costa Rica. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179(9):765–71. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200808-1361OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Freishtat RJ, Iqbal SF, Pillai DK, Klein CJ, Ryan LM, Benton AS, Teach SJ. High prevalence of vitamin D deficiency among inner-city African American youth with asthma in Washington, DC. J Pediatr. 2010;156:948–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2009.12.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinellato I, Piazza M, Sandri M, Peroni DG, Cardinale F, Piacentini GL, et al. Vitamin D serum levels and exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in children with asthma. Eur Respir J. 2010;37:1366–1370. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00044710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brehm JM, Schuemann B, Fuhlbrigge AL, Hollis BW, Strunk RC, Zeiger RS, et al. Serum vitamin D levels and severe asthma exacerbations in the Childhood Asthma Management Program study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;126:52–58. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li F, Peng M, Jiang L, Sun Q, Zhang K, Lian F, Litonjua AA, Gao J, Gao X. Vitamin D deficiency is associated with decreased lung function in Chinese adults with asthma. Respiration. 2011;81:469–75. doi: 10.1159/000322008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chinellato I, Piazza M, Sandri M, Peroni D, Piacentini G, Boner AL. Vitamin D serum levels and markers of asthma control in Italian children. J Pediatr. 2011;158:437–441. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2010.08.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brehm JM, Acosta-Pérez E, Klei L, Roeder K, Barmada M, Boutaoui N, Forno E, Kelly R, Paul K, Sylvia J, Litonjua AA, Cabana M, Alvarez M, Colón-Semidey A, Canino G, Celedón JC. Vitamin D insufficiency and severe asthma exacerbations in Puerto Rican children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:140–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0431OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bener A, Ehlayel MS, Tulic MK, Hamid Q. Vitamin D deficiency as a strong predictor of asthma in children. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2012;157:168–75. doi: 10.1159/000323941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hollams EM, Hart PH, Holt BJ, Serralha M, Parsons F, de Klerk NH, Zhang G, Sly PD, Holt PG. Vitamin D and atopy and asthma phenotypes in children: a longitudinal cohort study. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1320–7. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00029011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu AC, Tantisira K, Li L, Fuhlbrigge AL, Weiss ST, Litonjua A Childhood Asthma Management Program Research Group. Effect of vitamin D and inhaled corticosteroid treatment on lung function in children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:508–13. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201202-0351OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miyake Y, Sasaki S, Tanaka K, Hirota Y. Dairy food, calcium and vitamin D intake in pregnancy, and wheeze and eczema in infants. Eur Respir J. 2010;35:1228–1234. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00100609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Camargo CA, Jr, Ingham T, Wickens K, Thadhani R, Silvers KM, Epton MJ, et al. Cord-blood 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels and risk of respiratory infection, wheezing, and asthma. Pediatrics. 2011;127:180–187. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-0442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Camargo CA, Rifas Shiman SL, Litonjua AA, Rich-Edwards JW, Weiss ST, Gold DR, et al. Maternal intake of vitamin D during pregnancy and risk of recurrent wheeze in children at 3 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:788–795. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erkkola M, Kaila M, Nwaru BI, Kronberg-Kippila C, Ahonen S, Nevalainen J, et al. Maternal vitamin D intake during pregnancy is inversely associated with asthma and allergic rhinitis in 5-year-old children. Clin Exp Allergy. 2009;39:875–882. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2009.03234.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Devereux G, Litonjua AA, Turner SW, Craig LC, McNeill G, Martindale S, et al. Maternal vitamin D intake during pregnancy and early childhood wheezing. Am J Clin Nutr. 2007;85:853–859. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/85.3.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paul G, Brehm JM, Alcorn JF, Holguín F, Aujla SJ, Celedón JC. Vitamin D and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:124–32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201108-1502CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bozzetto S, Carraro S, Giordano G, Boner A, Baraldi E. Asthma, allergy and respiratory infections: the vitamin D hypothesis. Allergy. 2011;67:10–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Black PN, Scragg R. Relationship between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and pulmonary function in the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Chest. 2005;128:3792–3798. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.6.3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zosky GR, Berry LJ, Elliot JG, James AL, Gorman S, Hart PH. Vitamin D deficiency causes deficits in lung function and alters lung structure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:1336–1343. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201010-1596OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bosse Y, Maghni K, Hudson TJ. 1alpha, 25-dihydroxy-vitamin D3 stimulation of bronchial smooth muscle cells induces autocrine, contractility, and remodeling processes. Physiol Genomics. 2007;29:161–168. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00134.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Searing DA, Zhang Y, Murphy J, Hauk PJ, Goleva E, Leung DY. Decreased serum vitamin D levels in children with asthma are associated with increased corticosteroid use. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125:995–1000. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adams JS, Hewison M. Unexpected actions of vitamin D: new perspectives on the regulation of innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab. 2008;4:80–90. doi: 10.1038/ncpendmet0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hollams EM. Vitamin D and atopy and asthma phenotypes in children. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:228–34. doi: 10.1097/ACI.0b013e3283534a32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robinson CL, Baumann LM, Gilman RH, Romero K, Combe JM, Cabrera L, Hansel NN, Barnes K, Gonzalvez G, Wise RA, Breysse PN, Checkley W. The Peru Urban versus Rural Asthma (PURA) Study: methods and baseline quality control data from a cross-sectional investigation into the prevalence, severity, genetics, immunology and environmental factors affecting asthma in adolescence in Peru. BMJ Open. 2012;2:e000421. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robinson CL, Baumann LM, Romero K, Combe JM, Gomez A, Gilman RH, Cabrera L, Gonzalvez G, Hansel NN, Wise RA, Barnes KC, Breysse PN, Checkley W. Effect of urbanisation on asthma, allergy and airways inflammation in a developing country setting. Thorax. 2011;66:1051–7. doi: 10.1136/thx.2011.158956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mata Fernández C, Fernández-Benítez M, Pérez Miranda M, Guillén Grima F. Validation of the Spanish version of the Phase III ISAAC questionnaire on asthma. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2005;15:201–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Miller MR, Hankinson JL, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. ATS/ERS Task Force. Standardisation of spirometry. Eur Respir J. 2005;26:319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonderman JS, Munro HM, Blot WJ, Signorello LB. Reproducibility of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin d and vitamin D-binding protein levels over time in a prospective cohort study of black and white adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2012;176:615–21. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quanjer PH, Stanojevic S, Cole TJ, Baur X, Hall GL, Culver B, Enright PL, Hankinson JL, Ip MS, Zheng J, Stocks J the ERS Global Lung Function Initiative. Multi-ethnic reference values for spirometry for the 3–95 year age range: the global lung function 2012 equations. Eur Respir J. 2012 doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Firth D. Bias Reduction of Maximum Likelihood Estimates. Biometrika. 1993;80:27–38. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar J, Muntner P, Kaskel FJ, Hailpern SM, Melamed ML. Prevalence and associations of 25-hydroxyvitamin D deficiency in US children: NHANES 2001–2004. Pediatrics. 2009;124:e362–70. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sharief S, Jariwala S, Kumar J, Muntner P, Melamed ML. Vitamin D levels and food and environmental allergies in the United States: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1195–202. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu X, Wang G, Hong X, Wang D, Tsai HJ, Zhang S, Arguelles L, Kumar R, Wang H, Liu R, Zhou Y, Pearson C, Ortiz K, Schleimer R, Holt PG, Pongracic J, Price HE, Langman C, Wang X. Gene-vitamin D interactions on food sensitization: a prospective birth cohort study. Allergy. 2011;66:1442–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02681.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.