Abstract

Myxococcus xanthus and Bacillus subtilis are common soil-dwelling bacteria that produce a wide range of secondary metabolites and sporulate under nutrient-limiting conditions. Both organisms affect the composition and dynamics of microbial communities in the soil. However, M. xanthus is known to be a predator, while B. subtilis is not. A screen of various prey led to the finding that M. xanthus is capable of consuming laboratory strains of B. subtilis, while the ancestral strain, NCIB3610, was resistant to predation. Based in part on recent characterization of several strains of B. subtilis, we were able to determine that the pks gene cluster, which is required for production of bacillaene, is the major factor allowing B. subtilis NCIB3610 cells to resist predation by M. xanthus. Furthermore, purified bacillaene was added exogenously to domesticated strains, resulting in resistance to predation. Lastly, we found that M. xanthus is incapable of consuming B. subtilis spores even from laboratory strains, indicating the evolutionary fitness of sporulation as a survival strategy. Together, the results suggest that bacillaene inhibits M. xanthus predation, allowing sufficient time for development of B. subtilis spores.

INTRODUCTION

Naturally occurring antibiotics are produced by bacteria as secondary metabolites and are typically found at relatively low sublethal concentrations, suggesting a role in intercellular and interspecies communication (1–3). Bacteria such as Myxococcus xanthus and Bacillus subtilis are known to produce large numbers of secondary metabolites composed of polyketides and nonribosomal peptides that may act both as antibiotics and as signaling molecules. For each of these organisms, biofilm formation and their capacity to differentiate into quiescent spores have been described. Roles for secondary metabolites during development have also been reported for these organisms (4–6).

M. xanthus is a deltaproteobacterium and serves as a model organism for the study of gliding motility, intercellular communication, and multicellular development. One additional prominent aspect of the M. xanthus life cycle is its capacity to act as a predator (7–10). Upon encountering a suitable source, M. xanthus cells penetrate microcolonies (11) and consume their prey, a process that requires secretion of lytic enzymes and metabolites that target susceptible cells (12, 13). Lytic enzymes such as proteases, lysozyme, amidases, and endopeptidases produced by M. xanthus are involved in extracellular degradation of cells. Formation of predatory biofilms is frequently described as “wolf pack” behavior, which is thought to facilitate predation by increasing the concentration of secreted lytic factors (14–16).

M. xanthus and B. subtilis secondary metabolites include both antifungal and antibacterial properties (17, 18). For M. xanthus, myxovirescin was recently demonstrated to inhibit lipoprotein production in proteobacteria, thereby defining a role in predation specifically for Gram-negative prey sources (19–21). Another M. xanthus metabolite, DKxanthene, has antioxidant properties, is required for developmental sporulation, gives M. xanthus its distinctive yellow color, and may also function as an interspecies signal (5). For B. subtilis, the lipopeptides plipastatin and surfactin have antimicrobial properties (22), while surfactin also affects surface tension and signaling during biofilm development (23). The peptide/polyketide bacillaene was first discovered to inhibit bacterial protein synthesis and has recently been implicated in interspecies interactions (24–26).

In this study, we sought to refine our understanding of M. xanthus predator-prey interactions with various strains of bacteria, specifically by investigating prey preference. We observed that while M. xanthus consumes laboratory strains of B. subtilis, the ancestral strain NCIB3610 is highly resistant to predation by M. xanthus. Further analyses indicated that production of bacillaene by B. subtilis inhibits predation by M. xanthus and that purified bacillaene could be added exogenously to susceptible strains to provide protection against predation. Additionally, B. subtilis laboratory strains were capable of generating spores that are resistant to predation by M. xanthus. We conclude that bacillaene is an effective secondary metabolite that transiently “protects” B. subtilis cells from predation during the process of sporulation in its natural environment.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, growth, and development.

Bacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Escherichia coli and B. subtilis strains were grown in LB at 37°C or 32°C. E. coli β2155, a diaminopimelic acid (DAP) auxotroph strain, was grown in the presence of 100 μg/ml DAP. M. xanthus strains were cultivated in casitone-yeast extract (CYE) medium at 32°C (27). If required, kanamycin was used at a final concentration of 50 or 100 μg/ml for M. xanthus strains. For the cultivation of B. subtilis strains, antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: chloramphenicol, 5 μg/ml; tetracycline, 10 μg/ml; spectinomycin, 100 μg/ml; and erythromycin, 0.5 μg/ml. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Rhodobacter capsulatus, Salmonella enterica, and Staphylococcus aureus strains were grown as previously described (28–31).

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains used in this study

| Species and strain | Genotype or description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Myxococcus xanthus DZ2 | Wild type | 51 |

| Bacillus subtilis | ||

| OI1085 | Domesticated strain | 52 |

| 168 | Domesticated strain | 53 |

| NCIB3610 | Ancestral strain | 39 |

| DS4085 | pksL::cat | This work |

| DS4114 | ppsC::tet | This work |

| DS4124 | pksL::cat ppsC::tet srfAC::Tn10 spec | This work |

| DS1122 | srfAC::Tn10 spec | 54 |

| DS3337 | sfp::mls | 55 |

| DS4113 | pksL::cat ppsC::tet | This work |

| Escherichia coli | ||

| DH5α | Laboratory strain | |

| β2155 | 56 | |

| Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium 6704 | 28 | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa 388 | 29 | |

| Staphylococcus aureus MN8 | 30 | |

| Rhodobacter capsulatus SB1003 | 31 |

B. subtilis mutant strain construction.

All constructs were first introduced into the domesticated strain PY79 by natural competence and then transferred to the 3610 background using SPP1-mediated generalized phage transduction (32). All strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All plasmids and primers used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. The ppsC::tet insertion-deletion allele was generated by long flanking homology PCR (using primers 1270 and 1271 and primers 1272 and 1273), and DNA containing a tetracycline resistance gene (pDG1515) was used as a template for marker replacement (33, 34). The pksL insertion-deletion allele was generated by long flanking homology PCR (using primers 1274 and 1275 and primers 1276 and 1278), and DNA containing a tetracycline resistance gene (pAC225) was used as a template for marker replacement (34).

Predation assays.

M. xanthus was grown in CYE medium to mid-log phase. Cells were harvested and washed twice with MMC buffer (20 mM morpholinepropanesulfonic acid [MOPS] [pH 7.6], 4.0 mM MgSO4, 2 mM CaCl2). M. xanthus cells were resuspended in MMC buffer to a final concentration of 2 × 109 cells/ml. Prey cells were grown overnight in strain-specific media to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of about 2. Cells were washed twice with water and resuspended in water to a final concentration of 1 × 1011/ml. Qualitative predation assays were performed on CFL (9) agar plates. Seven microliters of prey cells was spotted onto the CFL plates. After the prey spot was dried, M. xanthus predatory cells (2 μl) were spotted into the middle of the prey spot (inside-out assay). Assay mixtures were incubated at 32°C, and pictures were taken after different times to monitor progression of predation.

Quantitative predation assays were performed by mixing prey and predator cells in a ratio of 50:1 and spread plating them on CFL agar plates. Prey and predator cells were prepared as described above. As controls, just prey or predator cells were spread plated on CFL agar plates. After incubation for 24 h at 32°C, cells were harvested and resuspended in water. Serial dilutions were plated on strain-selective media and incubated at 32°C for 5 days to quantify predator CFU or at 37°C overnight to calculate prey survival. Assays were performed in triplicate. The average CFU and standard deviation were calculated for each experiment. Prey survival and predator growth were calculated as percentages, with prey-only or predator-only controls, respectively, set to 100%.

Bacillaene extraction and purification.

Bacillus amyloliquefaciens CH12 (35) was cultured aerobically at 37°C in LB. Two 4-liter flasks containing 1 liter each of sterile production medium (100 mM MOPS [pH 7], 5 mM potassium phosphate, 0.5% [wt/vol] sodium glutamate, 0.5% [wt/vol] glycerol, 1 mM MgSO4, 100 μM CaCl2, 6 μM MnSO4, 3 μM FeSO4) were inoculated with the overnight culture at an initial OD600 of 0.008. The flasks were incubated with shaking at 25°C (26 h, 240 rpm, 1-in. throw, light excluded). All remaining steps were carried out in the dark. Cells were removed by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 30 min, 25°C), and the combined supernatants were extracted with 1 volume (2 liters) CH2Cl2. The organic layer was washed with a saturated NaCl solution to break a partial emulsion and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in 50% methanol (MeOH)–20 mM NaPi (pH 7), and insoluble particulate was removed by centrifugation (4,000 × g, 10 min, 25°C). The clarified culture extract was filtered and chromatographed on an Agilent 1200 high-pressure liquid chromatograph (HPLC) as follows. The crude sample was injected (sequential 50-μl injections) onto a semipreparative (10 by 250 mm, 5 μm) Phenomenex Luna C18 column equilibrated with 35% acetonitrile (ACN)–20 mM NaPi (pH 7) and eluted with a gradient program (solvent A, 20 mM NaPi [pH 7]; solvent B, acetonitrile; wash postinjection with 35% B for 2 min; ramp to 40% B over 8 min; hold at 40% B for 2 min; return to 35% B over 3 min; and reequilibrate at 35% for 5 min). Absorbance was monitored at 361 nm, and fraction collection was triggered in the 7- to 14-min time window by a minimum threshold absorbance above the baseline. Fractions containing the single major bacillaene peak were pooled and evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in 20% MeOH and passed through a Supelco C18 SPE cartridge for desalting. Bacillaene was eluted from the cartridge with 100% MeOH, and the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in water and lyophilized. The product was stored desiccated at −80°C until use. Purity was estimated to be ∼90% by HPLC, and bacillaene integrity was verified by UV and liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) (603 [M + Na]+, 581 [M + H]+, 579 [M − H]−).

B. subtilis spore preparation.

B. subtilis spores were made and purified according to protocols described earlier (36). Briefly, strains were grown for 3 days in DSM sporulation medium (Difco) at 37°C with shaking. Sporulated cultures were centrifuged, and the pellets were washed with 1/4 culture volume 1 M KCl–0.5 M NaCl and treated with lysozyme (50 μg/ml) at 37°C for 60 min in 1/4 culture volume 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.2. Spores were cleaned by an alternate washing step with 1 M NaCl, 0.05% SDS, 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.2), and 10 mM EDTA and 4 washes with H2O. Spores were resuspended to a final concentration of 4 × 108/ml. Predation assays using mature spores were performed as inside-out assays (described above) on MOPS agar plates (0.1 M MOPS, pH 7.6).

Microscopy.

Predation assays were monitored by microscopy using a Nikon SMZ10000 dissecting microscope. Images were taken using a QImaging Micropublisher charge-coupled device (CCD) camera and processed with QCapture software.

RESULTS

Domesticated bacterial strains are sensitive to predation by Myxococcus xanthus.

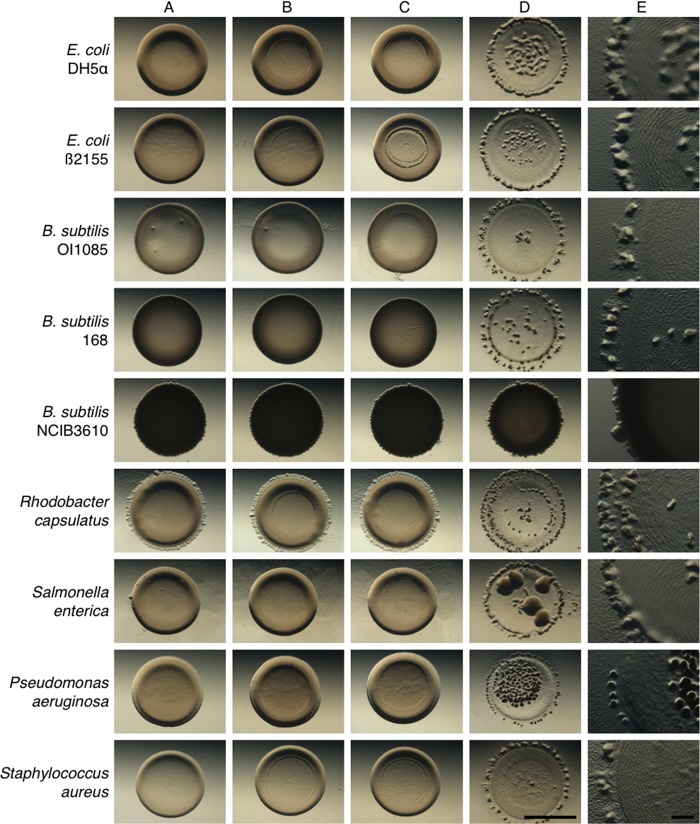

To assess whether M. xanthus displays a preference for specific prey, we conducted a screen with different bacteria, including several isolates of Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella enterica, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Rhodobacter capsulatus, Escherichia coli, and Bacillus subtilis (Fig. 1; Table 2). The screen allowed us to verify predation as indicated by M. xanthus rippling behavior in the presence of prey on low-nutrient agar surfaces (CFL) as described previously (8–10). Prey cells were spotted on agar at high density (7-μl aliquots at 1 × 1011 cells/μl). Subsequently, M. xanthus predator cells were spotted at a lower density (2-μl aliquots at 2 × 109cells/μl) into the center of the prey (Fig. 1D). The assay conditions provide immediate and direct contact between a minority of predator cells with an excess of prey cells. Successful predation is then indicated by plaque formation or clearing of the prey colony. Predation is accompanied by multicellular rippling (Fig. 1E), which is followed by fruiting body formation at the edge of the initial prey spot, where consumption of prey generates a step-down in nutrient availability (Fig. 1D and E) (9). As controls, prey alone (Fig. 1A), prey plus buffer (Fig. 1B), and prey plus heat-killed M. xanthus cells (Fig. 1C) were spotted onto CFL agar, and these did not produce plaques. Thus, plaque formation by M. xanthus is an active process that indicates that predation has occurred under these conditions (Fig. 1D). The results from this screen revealed that M. xanthus cells prey on a wide variety of bacteria, including Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains.

FIG 1.

M. xanthus predation of various prey strains. Shown are predation assays using different Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains as prey for M. xanthus predator cells. Efficient predation results in clearing of the prey spot, with M. xanthus fruiting body formation occurring at the edge of the original prey spot. The prey strains tested were E. coli DH5α and B2155, B. subtilis OI1085, 168, and NCIB3610, Rhodobacter capsulatus, Salmonella enterica, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Staphylococcus aureus. Strains resisting predation show only minimal lysis at the center of the prey spot. (A) Prey only; (B) prey with buffer spotted at center; (C) prey with heat-killed predator; (D) prey with predator. Pictures were taken at 48 h after spotting at a magnification of ×10 (A to D) or ×30 (E). Bars, 0.5 cm (A to D) and 0.1 cm (E).

TABLE 2.

Prey survival and predator growth

| Prey | % prey survival (mean ± SD) | % predator growth (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli β2155 | 0.0007 ± 0.00006 | 2,501 ± 468 |

| B. subtilis | ||

| OI1085 | 0.046 ± 0.01 | 1,912 ± 307 |

| 168 | 0.293 ± 0.06 | 524 ± 47 |

| NCIB3610 | 68 ± 12.8 | 110 ± 20 |

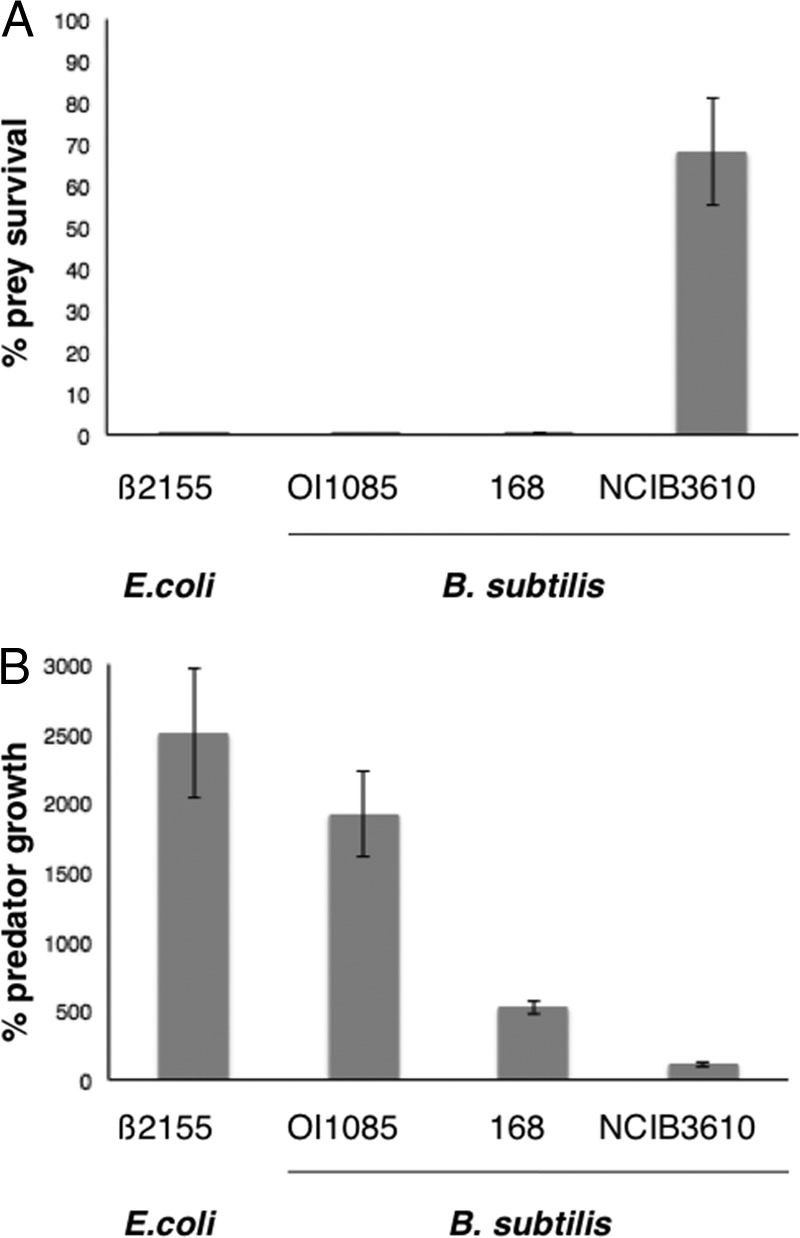

The assay described above is not quantitative and may not reveal a preference for any given prey. In order to quantify predation efficiency, we used predator and prey strains encoding selectable markers to allow for accurate determination of prey survival and growth of the predator over time. For these assays, we chose standard laboratory strains of B. subtilis and E. coli as prey. We mixed prey cells with M. xanthus predator cells and then plated on low-nutrient agar. After 24 h, the mixed population was harvested and plated on rich medium with the appropriate antibiotic to determine CFU for either the predator or prey. The results (Table 2) indicated that the vast majority of cells for E. coli β2155 and two domesticated strains of B. subtilis, 168 and OI1085, were consumed efficiently (<1.0% prey survival). As expected, M. xanthus predation of E. coli and B. subtilis supported efficient growth as indicated by an increase in CFU for the predator. M. xanthus growth varied slightly depending on the prey source, suggesting a slight preference for Gram-negative over Gram-positive strains. This result is consistent with recent observations made by the Wall and Velicer groups which may reflect differences in prey suitability (21, 37).

Ancestral Bacillus subtilis NCIB3610 is resistant to predation by Myxococcus xanthus.

Because M. xanthus is a soil-dwelling organism, it is unlikely to come in direct contact with the domesticated strains or clinical isolates tested above. Thus, we tested the capacity for M. xanthus to prey on B. subtilis NCIB3610, an ancestor of the lab strain 168 (Fig. 1). Strikingly, NCIB3610 was highly resistant to predation compared to the domesticated strains, 168 and OI1085. Some lysis of NCIB3610 was observed, but only where M. xanthus came into immediate contact with B. subtilis as a result of directly spotting the predator onto the prey. This assay shows that the ancestral B. subtilis strain is naturally resistant to predation by M. xanthus. The quantitative assay also indicated that ancestral Bacillus resists predation by M. xanthus. The majority of NCIB3610 cells, 68%, survived predation (Fig. 2A). However, there was some growth (110% relative to the control) and no cell death displayed for M. xanthus in this assay (Fig. 2B). Such a modest increase suggests that the killing of NCIB3610 cells is due to conditions of the assay where both predator and prey are mixed immediately prior to plating. The results also indicate that B. subtilis does not kill M. xanthus cells under the conditions of this assay. Together the results allow us to conclude that ancestral Bacillus strain NCIB3610 actively resists predation, possibly facilitated by secretion of defensive molecules to inhibit predation by M. xanthus.

FIG 2.

Quantification of prey survival and predator growth. (A) Prey and predator cells were mixed in a ratio of 50:1, plated onto CFL agar plates, and incubated at 32°C for 24 h. Prey and predator alone were used as controls. CFU were determined, and percent prey survival and percent predator growth were calculated relative to the controls. The majority of E. coli β2155 and B. subtilis OI1085 and 168 were consumed, whereas about 68% of B. subtilis NCIB3610 survived. (B) M. xanthus was able to grow significantly on E. coli β2155 and B. subtilis OI1085 but not the ancestral B. subtilis NCIB3610 strain.

Bacillus subtilis bacillaene inhibits predation by Myxococcus xanthus.

The observation that the ancestral Bacillus subtilis NCIB3610 was resistant to predation while domesticated strains were susceptible to predation raised the question as to what factors or properties distinguish the two from each other. We hypothesized that resistance by NCIB3610 would most likely be due to production of inhibitory molecules. A key observation came from a recent study where McLoon et al. (38) identified five loci responsible for observed differences between B. subtilis 168 and NCIB3610. Strain 168 is attenuated for biofilm formation on MSgg agar plates and is defective in swarming motility and extracellular polysaccharide (EPS) production (4, 38, 39). Complementation of 168 to restore biofilm formation on MSgg agar confirmed that the observed defects in 168 were attributable to mutations in sfp (polyketide production), swrA (swarming motility), epsC (exopolysaccharide production), the promoter of degQ (secretion of degradative enzymes), and rapP (plasmid-encoded phosphatase) (40). In addition, a detailed study compared B. subtilis legacy strains (including NCIB3610 and the most commonly used laboratory strains) and identified 22 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as the major differences between NCIB3610 and 168 (39). Based on these studies, the mutation in sfp seemed to be the most likely candidate affecting predation by M. xanthus.

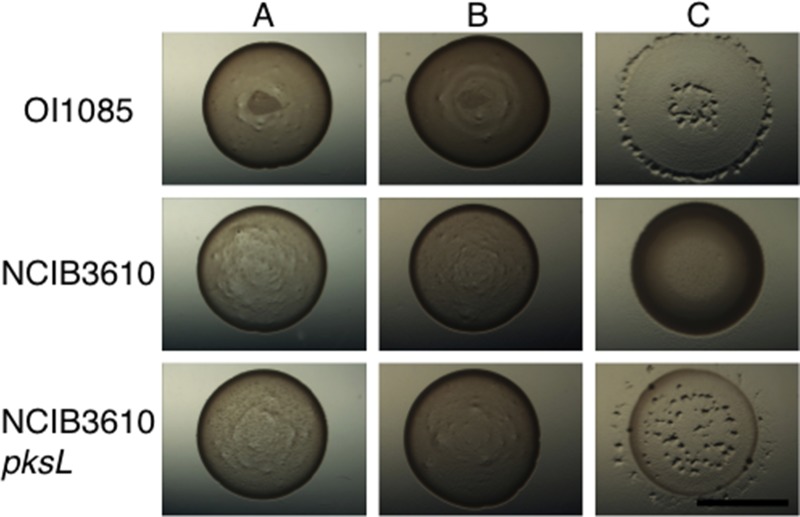

In B. subtilis, sfp encodes phosphopantetheinyl transferase, which posttranslationally modifies a serine residue within carrier domains of peptide synthetases (41). Thus, Sfp provides a necessary early step in the production of several small molecules, including the lipopeptide antibiotic surfactin, the phospholipase A2 inhibitor plipastatin, and the bacterial protein synthesis inhibitor bacillaene (41–44). To investigate whether Sfp is required for production of a small-molecule inhibitor, we first generated an NCIB3610 sfp mutant and assayed cells for resistance to predation by M. xanthus. The inside-out predation assay indicated that both lysis of prey and subsequent fruiting body formation had occurred (Fig. 3A), confirming that Sfp is required for resistance to predation by M. xanthus. Furthermore, quantification revealed that the sfp mutant cells cannot survive when mixed with M. xanthus cells under the conditions of this assay (Fig. 3B). Likewise, growth of the predator (Fig. 3C) corresponded with elimination of the sfp prey cells.

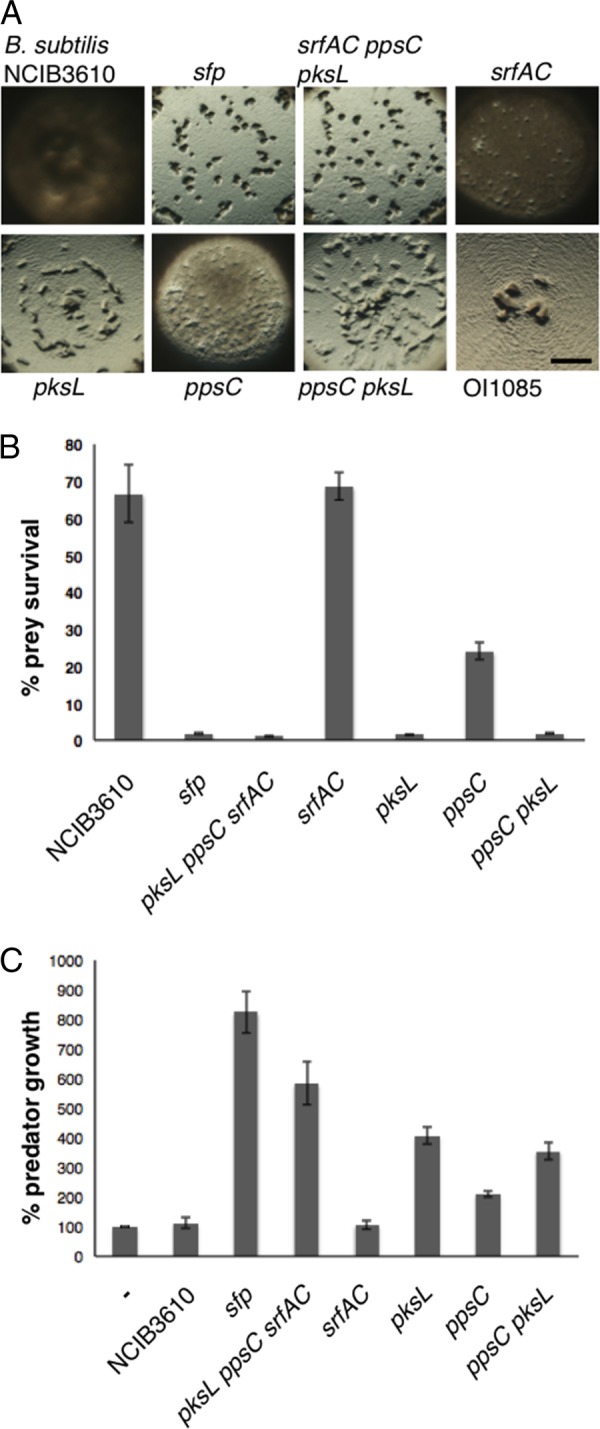

FIG 3.

Bacillaene inhibits M. xanthus predation. (A) Predation assays using the domesticated, ancestral, and mutant strains of B. subtilis. Mutations in sfp and pksL reveal the requirement for bacillaene as the major factor inhibiting M. xanthus predation. Pictures were taken 24 h after spotting M. xanthus predator cells in the center of the prey source. Bar, 0.1 cm. (B) Prey survival was quantified as described for Fig. 2 and normalized to that for the NCIB3610 control spotted without the predator. (C) Growth of the M. xanthus predator was quantified after 24 h and normalized to that for M. xanthus cells spotted without prey.

Sfp is required for production of surfactin, plipastatin, and bacillaene. Therefore, we generated mutations in genes encoding components required for production of each molecule, srfAC, ppsC, and pksL, respectively. Cells from each mutant strain were tested in the predation assay and quantified for survival and capacity to promote growth of the predator (Fig. 3). M. xanthus formed large plaques at the center of the prey colony (Fig. 3A) when introduced to B. subtilis cells carrying the mutation in pksL but not when introduced to NCIB3610 cells. Furthermore, quantitative assays indicated that the survival of B. subtilis cells with pksL mutated was reduced to only 1.4% following M. xanthus predation. In contrast, the survival of B. subtilis cells mutated for ppsC was 24% and survival for the srfAC mutant was similar to that for the parent (∼68%) following M. xanthus predation.

Mutations were also generated to assess the possibility of combinatorial effects. The pksL ppsC double mutant and the pksL ppsC srfAC triple mutant strains displayed 1.74% and 1.1% survival, respectively, similar to the levels displayed by the pksL (∼1.4%) and sfp (∼1.6%) single mutant strains (Fig. 3B). Thus, cells that cannot produce bacillaene have greatly diminished ability to escape predation by M. xanthus cells. In addition, the results indicate that combinations of mutations in pksL with either srfAC or ppsC do not display synergy under the conditions of this assay, revealing that bacillaene, synthesized in part by PksL, promotes B. subtilis survival when challenged with M. xanthus.

Furthermore, M. xanthus growth correlated well with its capacity to kill B. subtilis strains and utilize them for nutrients. This is evident by the increased growth observed for M. xanthus, where CFU following predation corresponded to 825% for sfp, 407% for pksL, and 584% for pksL ppsC srfAC mutant cells (Fig. 3C). These results indicated that M. xanthus kills and utilizes susceptible strains and that B. subtilis mutants lacking the capacity to produce bacillaene result in the greatest growth for the predator.

We note, however, that there is a difference for predator growth upon consumption of sfp mutant cells (825%) versus pksL mutant cells (407%), about 2-fold, possibly reflecting a modest level of synergy. Of the single mutants tested, those cells deficient in surfactin production (srfAC) resulted in only 106% predator growth, similar to that for the ancestral parent. In contrast, cells deficient in plipastatin production (ppsC) resulted in modest gains, about 210% predator growth, while those cells deficient in bacillaene production (pksL) resulted in the greatest amount of predator growth at 407%. Thus, the combination of Sfp-dependent secondary metabolites may be additive, where plipastatin and bacillaene have the greatest individual effects on predator growth. Nevertheless, the overall effects of individual mutations for these loci result in predator growth that is reciprocally related to their effects on survival. In summary, bacillaene provides a critical contribution to prey survival and corresponding prevention of predator growth, suggesting that production of bacillaene by the ancestral strain, B. subtilis NCIB3610, effectively functions as a significant defense protecting cells from predation by M. xanthus.

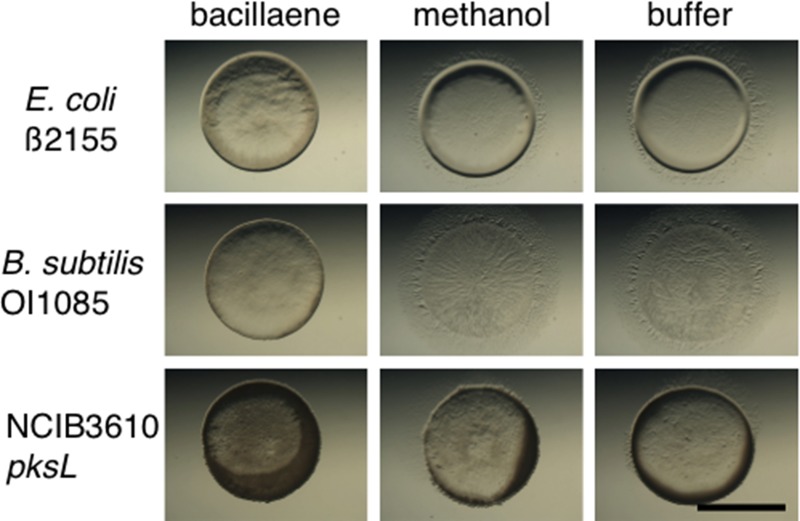

Support for this conclusion was obtained by mixing purified bacillaene with sensitive prey and challenging those cells with the predator (Fig. 4). Cells from the predation-sensitive, domesticated strains E. coli β2155 and B. subtilis OI1085 and the B. subtilis 3610 pksL mutant were mixed with bacillaene. The predator was spotted into the middle of the prey spot as described above (Fig. 4). As controls, prey cells were mixed with either methanol (used for solubilizing bacillaene) or MMC buffer (Fig. 4). The plates were incubated in the dark to avoid light-induced degradation of bacillaene, and pictures were taken at 24 h. Addition of bacillaene was observed to provide protection for otherwise sensitive prey relative to controls (Fig. 4). Importantly, purified bacillaene did not affect vegetative growth of M. xanthus, while fruiting body formation was transiently delayed (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material). Together, these results indicate that bacillaene protects susceptible cells from predation without affecting growth of the predator.

FIG 4.

Bacillaene protects sensitive prey. Predation assays were conducted using sensitive prey mixed with purified bacillaene (left), methanol (center), and MMC buffer (right) on CFL agar plates. Photographs were taken after 24 h. Sensitive prey were protected in the presence of bacillaene. Bar, 0.5 cm.

Bacillus subtilis spores are resistant to predation.

One factor affecting interpretation of the quantitative assays is that B. subtilis is capable of sporulating under stressful conditions which might render cells resistant to predation by M. xanthus. To test this, we assayed the B. subtilis spores for their capacity to resist predation by M. xanthus. The assays were performed on MOPS agar, completely lacking nutrients, to prevent germination of the B. subtilis spores being tested. Spores were purified from the B. subtilis domesticated strain OI1085, the ancestral strain NCIB3610, and the NCIB3610 pksL mutant using the method described previously (36). Spore suspensions were spotted on MOPS agar and did not germinate under these conditions (Fig. 5A). When M. xanthus cells were spotted onto the spores, no predation was observed for any of the strains tested (Fig. 5B). As a control, vegetatively growing cells for each strain were tested on MOPS agar as prey. As expected, OI1085 and NCIB3610 pksL were susceptible to predation on MOPS agar, while the NCIB3610 parent was resistant (Fig. 5C). We conclude that sporulation enables B. subtilis to escape predation. It is also worth noting that the NCIB3610 pksL mutant is competent for sporulation.

FIG 5.

Bacillus subtilis spores resist predation. Spores were made and purified as described in Materials and Methods (36). Spores were spotted on MOPS agar plates lacking any nutrients to prevent spore germination. Predation assays were conducted as shown in Fig. 1. Shown are spores alone (A), spores with predator cells (B), and vegetative prey cells with the predator (C). Domesticated strains as well as the NCIB3610 pksL mutant cells are capable of producing predation-resistant spores. Bar, 0.5 cm.

Lastly, we assayed for predation of spores on low-nutrient CFL medium. In the control assay, we observed B. subtilis outgrowth from spores on CFL agar plates (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material), due to the presence of nutrients in the medium. Because spores from all stains tested were completely resistant to predation, the results indicate that M. xanthus preys upon live cells or cellular debris. Furthermore, CFL promotes outgrowth of spores which would render prey susceptible to predation by M. xanthus. Thus, any spores formed by B. subtilis during predation assays on CFL medium would subsequently germinate, thereby eliminating sporulation as a confounding factor in the quantitation described above.

DISCUSSION

Myxococcus xanthus and Bacillus subtilis are ubiquitous soil bacteria that produce a wide range of secondary metabolites and sporulate under nutrient-limiting conditions (3, 7, 45). From an ecological perspective, M. xanthus is likely to affect the composition and dynamics of microbial communities due to its capacity for predation (21, 37). In this study, we observed that bacillaene-producing B. subtilis cells are effectively resistant to predation by M. xanthus cells. The inhibitory effect of bacillaene provides ample time for those cells to develop into mature spores without becoming prey for M. xanthus cells. This conclusion is supported by the fact that addition of purified bacillaene resulted in limited protection of sensitive prey such as E. coli. We also conclude that sporulation enables B. subtilis to escape predation. It is worth noting that the NCIB3610 pksL mutant is competent for sporulation, indicating that pksL is not required for sporulation even though Spo0A is known to be required for bacillaene production (46).

Production of secondary metabolites from different soil bacteria has been shown to regulate interactions with their neighbors. For example, Streptomyces strain A3 was shown to upregulate secondary metabolite production in the presence of certain bacteria, leading to the consumption or lysis of the inducing strains (47). In another example, competition experiments identified surfactin from B. subtilis as a negative regulator of aerial hypha formation and sporulation in Streptomyces coelicolor (25). Likewise, M. xanthus was found to induce secondary metabolite production and aerial mycelium formation in S. coelicolor (48). Additionally, B. subtilis bacillaene was found to inhibit the production of prodiginines by S. coelicolor and to inhibit growth of Streptomyces avermitilis (25, 26, 49), and similarly, a coculturing experiment demonstrated that a bacillaene mutant strain was more susceptible to lysis by Streptomyces (50). Taking these together with our results, it is clear that bacillaene plays a significant role in protection for B. subtilis in the natural environment and displays a broad range regarding host susceptibility.

Because of its large repertoire of genes dedicated to secondary metabolite production, we suspected that M. xanthus would be an efficient predator against many bacteria. Our screen to test different species of prey revealed that M. xanthus is able to consume both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacterial species, indicating that cell wall structure is not sufficient for protection from predation. Interestingly, M. xanthus was able to consume a wide variety of pathogenic, clinical isolates such as Salmonella and Staphylococcus strains. Even though M. xanthus does not readily prey upon the ancestral B. subtilis strain, it efficiently consumes related domesticated strains. The common denominator regarding predation for the domesticated strains we tested here is a defect in phosphopantetheinyl transferase activity. Thus, it appears that sensitive B. subtilis strains have simply lost their capacity to produce secondary metabolites which otherwise confer resistance to predation. It is likely that clinical isolates or human commensals which do not naturally encounter M. xanthus have developed alternative antimicrobials suited to their competitors.

Overall, our results show that bacillaene is a primary defensive molecule generated by B. subtilis that confers substantial resistance to predation by M. xanthus. Both the structure and biosynthetic pathway for bacillaene have been determined (43, 49), and its regulation is under the control of multiple factors to allow for dynamic control (46). Bacillaene was first described as an inhibitor of bacterial protein synthesis (24) even though our results indicate that predator growth is not affected by the addition of purified bacillaene. Because both Bacillus subtilis and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens are known to generate bacillaene, it appears that the pks cluster has been conserved in this clade, thereby implying a broader role for bacillaene as a defensive molecule for some Bacillus species (35). It remains unknown whether other Bacillus isolates will be found to produce bacillaene or a similar derivative with defensive properties. Based on previous studies and our findings presented here, bacillaene appears to play a central role in the regulation of interspecies interactions between B. subtilis and Streptomyces or Myxococcus. Bacillaene transiently inhibits the predatory capacity of M. xanthus cells, which enables B. subtilis to form spores in the presence of M. xanthus cells.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the laboratories of Steve Clegg, Carl Bauer, Patrick Schlievert, and Tim Yahr for providing us with bacterial strains listed in Table 1. DNA sequencing was performed by Nevada Genomics Center (University of Nevada, Reno). We thank the members of the Kirby lab for their support during the project period.

Support for this work was provided by NSF grant MCB-1244021 and grants from the University of Iowa Carver College of Medicine to both S.M. and J.R.K. Additional support was provided by NSF-CAREER grant MCB-1253215 to P.D.S. and NIH grant GM093030 to D.B.K.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print 7 July 2014

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01621-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Davies J, Spiegelman GB, Yim G. 2006. The world of subinhibitory antibiotic concentrations. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:445–453. 10.1016/j.mib.2006.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fajardo A, Martinez JL. 2008. Antibiotics as signals that trigger specific bacterial responses. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 11:161–167. 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berleman JE, Kirby JR. 2009. Deciphering the hunting strategy of a bacterial wolfpack. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 33:942–957. 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00185.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Branda SS, Gonzalez-Pastor JE, Ben-Yehuda S, Losick R, Kolter R. 2001. Fruiting body formation by Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98:11621–11626. 10.1073/pnas.191384198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meiser P, Bode HB, Muller R. 2006. The unique DKxanthene secondary metabolite family from the myxobacterium Myxococcus xanthus is required for developmental sporulation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103:19128–19133. 10.1073/pnas.0606039103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lopez D, Vlamakis H, Losick R, Kolter R. 2009. Paracrine signaling in a bacterium. Genes Dev. 23:1631–1638. 10.1101/gad.1813709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reichenbach H. 1999. The ecology of the myxobacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 1:15–21. 10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00016.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berleman JE, Chumley T, Cheung P, Kirby JR. 2006. Rippling is a predatory behavior in Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 188:5888–5895. 10.1128/JB.00559-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berleman JE, Kirby JR. 2007. Multicellular development in Myxococcus xanthus is stimulated by predator-prey interactions. J. Bacteriol. 189:5675–5682. 10.1128/JB.00544-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berleman JE, Scott J, Chumley T, Kirby JR. 2008. Predataxis behavior in Myxococcus xanthus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105:17127–17132. 10.1073/pnas.0804387105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McBride MJ, Zusman DR. 1996. Behavioral analysis of single cells of Myxococcus xanthus in response to prey cells of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 137:227–231. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08110.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hart BA, Zahler SA. 1966. Lytic enzyme produced by Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 92:1632–1637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sudo S, Dworkin M. 1972. Bacteriolytic enzymes produced by Myxococcus xanthus. J. Bacteriol. 110:236–245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hillesland KL, Lenski RE, Velicer GJ. 2007. Ecological variables affecting predatory success in Myxococcus xanthus. Microb. Ecol. 53:571–578. 10.1007/s00248-006-9111-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaiser D. 2004. Signaling in myxobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 58:75–98. 10.1146/annurev.micro.58.030603.123620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg E, Keller KH, Dworkin M. 1977. Cell density-dependent growth of Myxococcus xanthus on casein. J. Bacteriol. 129:770–777 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weissman KJ, Muller R. 2010. Myxobacterial secondary metabolites: bioactivities and modes-of-action. Nat. Prod. Rep. 27:1276–1295. 10.1039/c001260m [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein T. 2005. Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: structures, syntheses and specific functions. Mol. Microbiol. 56:845–857. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04587.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosenberg E, Vaks B, Zuckerberg A. 1973. Bactericidal action of an antibiotic produced by Myxococcus xanthus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 4:507–513. 10.1128/AAC.4.5.507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerth K, Irschik H, Reichenbach H, Trowitzsch W. 1982. The myxovirescins, a family of antibiotics from Myxococcus virescens (Myxobacterales). J. Antibiot. 35:1454–1459. 10.7164/antibiotics.35.1454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Xiao Y, Wei X, Ebright R, Wall D. 2011. Antibiotic production by myxobacteria plays a role in predation. J. Bacteriol. 193:4626–4633. 10.1128/JB.05052-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volpon L, Besson F, Lancelin JM. 2000. NMR structure of antibiotics plipastatins A and B from Bacillus subtilis inhibitors of phospholipase A(2). FEBS Lett. 485:76–80. 10.1016/S0014-5793(00)02182-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vlamakis H, Chai Y, Beauregard P, Losick R, Kolter R. 2013. Sticking together: building a biofilm the Bacillus subtilis way. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 11:157–168. 10.1038/nrmicro2960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Patel PS, Huang S, Fisher S, Pirnik D, Aklonis C, Dean L, Meyers E, Fernandes P, Mayerl F. 1995. Bacillaene, a novel inhibitor of procaryotic protein synthesis produced by Bacillus subtilis: production, taxonomy, isolation, physico-chemical characterization and biological activity. J. Antibiot. 48:997–1003. 10.7164/antibiotics.48.997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straight PD, Willey JM, Kolter R. 2006. Interactions between Streptomyces coelicolor and Bacillus subtilis: role of surfactants in raising aerial structures. J. Bacteriol. 188:4918–4925. 10.1128/JB.00162-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang YL, Xu Y, Straight P, Dorrestein PC. 2009. Translating metabolic exchange with imaging mass spectrometry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 5:885–887. 10.1038/nchembio.252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bretscher AP, Kaiser D. 1978. Nutrition of Myxococcus xanthus, a fruiting myxobacterium. J. Bacteriol. 133:763–768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dwyer BE, Newton KL, Kisiela D, Sokurenko EV, Clegg S. 2011. Single nucleotide polypmorphisms of fimH associated with adherence and biofilm formation by serovars of Salmonella enterica. Microbiology 157:3162–3171. 10.1099/mic.0.051425-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iglewski BH, Sadoff J, Bjorn MJ, Maxwell ES. 1978. Pseudomonas aeruginosa exoenzyme S: an adenosine diphosphate ribosyltransferase distinct from toxin A. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 75:3211–3215. 10.1073/pnas.75.7.3211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blomster-Hautamaa DA, Schlievert PM. 1988. Preparation of toxic shock syndrome toxin-1. Methods Enzymol. 165:37–43. 10.1016/S0076-6879(88)65009-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yen HC, Marrs B. 1976. Map of genes for carotenoid and bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis in Rhodopseudomonas capsulata. J. Bacteriol. 126:619–629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yasbin RE, Young FE. 1974. Transduction in Bacillus subtilis by bacteriophage SPP1. J. Virol. 14:1343–1348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Guerout-Fleury AM, Frandsen N, Stragier P. 1996. Plasmids for ectopic integration in Bacillus subtilis. Gene 180:57–61. 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00404-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wach A. 1996. PCR-synthesis of marker cassettes with long flanking homology regions for gene disruptions in S. cerevisiae. Yeast 12:259–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen XH, Vater J, Piel J, Franke P, Scholz R, Schneider K, Koumoutsi A, Hitzeroth G, Grammel N, Strittmatter AW, Gottschalk G, Sussmuth RD, Borriss R. 2006. Structural and functional characterization of three polyketide synthase gene clusters in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB 42. J. Bacteriol. 188:4024–4036. 10.1128/JB.00052-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholson WL, Law JF. 1999. Method for purification of bacterial endospores from soils: UV resistance of natural Sonoran desert soil populations of Bacillus spp. with reference to B. subtilis strain 168. J. Microbiol. Methods 35:13–21. 10.1016/S0167-7012(98)00097-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Morgan AD, MacLean RC, Hillesland KL, Velicer GJ. 2010. Comparative analysis of myxococcus predation on soil bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76:6920–6927. 10.1128/AEM.00414-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLoon AL, Guttenplan SB, Kearns DB, Kolter R, Losick R. 2011. Tracing the domestication of a biofilm-forming bacterium. J. Bacteriol. 193:2027–2034. 10.1128/JB.01542-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeigler DR, Pragai Z, Rodriguez S, Chevreux B, Muffler A, Albert T, Bai R, Wyss M, Perkins JB. 2008. The origins of 168, W23, and other Bacillus subtilis legacy strains. J. Bacteriol. 190:6983–6995. 10.1128/JB.00722-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Parashar V, Konkol MA, Kearns DB, Neiditch MB. 2013. A plasmid-encoded phosphatase regulates Bacillus subtilis biofilm architecture, sporulation, and genetic competence. J. Bacteriol. 195:2437–2448. 10.1128/JB.02030-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quadri LE, Weinreb PH, Lei M, Nakano MM, Zuber P, Walsh CT. 1998. Characterization of Sfp, a Bacillus subtilis phosphopantetheinyl transferase for peptidyl carrier protein domains in peptide synthetases. Biochemistry 37:1585–1595. 10.1021/bi9719861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakano MM, Zuber P. 1989. Cloning and characterization of srfB, a regulatory gene involved in surfactin production and competence in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 171:5347–5353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Butcher RA, Schroeder FC, Fischbach MA, Straight PD, Kolter R, Walsh CT, Clardy J. 2007. The identification of bacillaene, the product of the PksX megacomplex in Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:1506–1509. 10.1073/pnas.0610503104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsuge K, Ano T, Shoda M. 1996. Isolation of a gene essential for biosynthesis of the lipopeptide antibiotics plipastatin B1 and surfactin in Bacillus subtilis YB8. Arch. Microbiol. 165:243–251. 10.1007/s002030050322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krug D, Zurek G, Revermann O, Vos M, Velicer GJ, Muller R. 2008. Discovering the hidden secondary metabolome of Myxococcus xanthus: a study of intraspecific diversity. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:3058–3068. 10.1128/AEM.02863-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vargas-Bautista C, Rahlwes K, Straight P. 2014. Bacterial competition reveals differential regulation of the pks genes by Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 196:717–728. 10.1128/JB.01022-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kumbhar C, Mudliar P, Bhatia L, Kshirsagar A, Watve M. 2014. Widespread predatory abilities in the genus Streptomyces. Arch. Microbiol. 196:235–248. 10.1007/s00203-014-0961-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Perez J, Munoz-Dorado J, Brana AF, Shimkets LJ, Sevillano L, Santamaria RI. 2011. Myxococcus xanthus induces actinorhodin overproduction and aerial mycelium formation by Streptomyces coelicolor. Microb. Biotechnol. 4:175–183. 10.1111/j.1751-7915.2010.00208.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Straight PD, Fischbach MA, Walsh CT, Rudner DZ, Kolter R. 2007. A singular enzymatic megacomplex from Bacillus subtilis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104:305–310. 10.1073/pnas.0609073103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barger SR, Hoefler BC, Cubillos-Ruiz A, Russell WK, Russell DH, Straight PD. 2012. Imaging secondary metabolism of Streptomyces sp. Mg1 during cellular lysis and colony degradation of competing Bacillus subtilis. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 102:435–445. 10.1007/s10482-012-9769-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muller S, Willett JW, Bahr SM, Darnell CL, Hummels KR, Dong CK, Vlamakis HC, Kirby JR. 2013. Draft genome sequence of Myxococcus xanthus wild-type strain DZ2, a model organism for predation and development. Genome Announc. 1(3):e00217-13. 10.1128/genomeA.00217-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ullah AH, Ordal GW. 1981. In vivo and in vitro chemotactic methylation in Bacillus subtilis. J. Bacteriol. 145:958–965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Burkholder PR, Giles NH., Jr 1947. Induced biochemical mutations in Bacillus subtilis. Am. J. Bot. 34:345–348. 10.2307/2437147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen R, Guttenplan SB, Blair KM, Kearns DB. 2009. Role of the σD-dependent autolysins in Bacillus subtilis population heterogeneity. J. Bacteriol. 191:5775–5784. 10.1128/JB.00521-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Patrick JE, Kearns DB. 2009. Laboratory strains of Bacillus subtilis do not exhibit swarming motility. J. Bacteriol. 191:7129–7133. 10.1128/JB.00905-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Dehio C, Meyer M. 1997. Maintenance of broad-host-range incompatibility group P and group Q. plasmids and transposition of Tn5 in Bartonella henselae following conjugal plasmid transfer from Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 179:538–540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.