Abstract

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is associated with a proneness to unpleasant self-conscious emotions (SCE). Given that BPD is also associated with heightened rates of SCE-eliciting events (including unwanted sexual experiences), research examining the factors influencing SCE in response to these events is needed. This study examined associations between BPD pathology and SCE in response to adult unwanted sexual experiences among 303 community women. Extent of sharing about and perceived personal responsibility for the event were examined as moderators of the association between BPD and current event-related SCE. Both self-reported BPD symptom severity in the full sample and interview-based measures of BPD symptom count and diagnosis in a subsample (n=75) were associated with greater SCE at the event and currently. Moreover, in the subsample, both BPD symptom count and diagnosis were associated with heightened current SCE only when (1) extent of sharing was low, or (2) perceived personal responsibility was high.

Keywords: borderline personality disorder, unwanted sexual experiences, shame, self-conscious emotions, reactions

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a serious mental health concern associated with impairments in behavioral, cognitive, interpersonal, and emotional functioning (e.g., Skodol et al., 2002). With regard to the latter domain, extant theories of BPD emphasize the central role of emotional dysfunction in this disorder, highlighting the relevance of both emotional vulnerability (including emotional intensity, reactivity, and instability) and difficulties regulating intense emotions to BPD (Crowell, Beauchaine, & Linehan, 2009; Fonagy & Bateman, 2008; Linehan, 1993; Skodol et al., 2002). Although these emotion-related difficulties are thought to apply to emotions in general, recent theories suggest that individuals with BPD are especially prone to self-conscious emotions (SCE) and experience particular difficulties responding adaptively to these emotions (Rizvi, Brown, Bohus, & Linehan, 2011). In contrast to basic emotions (the capacities for which are present universally from birth), SCE develop later in life and require both self-awareness and the ability to hold in mind and evaluate self-representations (e.g., Lewis, Sullivan, Stangor, & Weiss, 1989). Unpleasant SCE, including shame, guilt, and self-anger, arise when individuals evaluate their behavior and/or personal characteristics negatively (cf. Tangney & Tracy, 2012). According to the biosocial theory (Linehan, 1993), experiences of invalidation during childhood may teach individuals with BPD that they are “bad” people who deserve punishment (see also Young, 1999), thereby increasing unpleasant SCE. Consistent with this theory, individuals with BPD have been found to endorse high levels of core beliefs related to Defectiveness/Shame (Jovev & Jackson, 2004), as well as to report higher levels of shame-proneness and exhibit a more shame-prone self-concept on an implicit measure than individuals with social phobia (Rüsch, Corrigan, et al., 2007) or posttraumatic stress disorder (Rüsch, Lieb, et al., 2007).

One type of event found to elicit SCE, and which is common among individuals with BPD, is adult unwanted sexual experiences (e.g., Amstadter & Vernon, 2008; McGowan, King, Frankenburg, Fitzmaurice, & Zanarini, 2012; Vidal & Petrak, 2007; Zanarini et al., 1999). Indeed, although SCE are common reactions to traumatic events in general (e.g., Andrews, Brewin, Rose, & Kirk, 2000; Kubany, Haynes, Abueg, Manke, Brennan, & Stahura, 1996), research suggests that they are particularly relevant to unwanted sexual experiences. For example, sexual assault has been found to result in higher levels of SCE than other traumatic events (e.g., physical assault; Amstadter & Vernon, 2008). Given the propensity for SCE within BPD (as well as the heightened rates of childhood abuse, neglect, and other invalidating experiences associated with this disorder; e.g., Ogata, Silk, Goodrich, Lohr, Westen, & Hill, 1990; Zanarini et al., 1997), individuals with BPD pathology may be particularly likely to experience SCE in response to adult unwanted sexual experiences.

Nonetheless, despite evidence that BPD pathology may be associated with greater SCE in response to unwanted sexual experiences, it is also likely that there is variability in the degree to which these emotions are maintained over time among individuals with BPD pathology. In particular, the relation between BPD pathology and current SCE in response to an unwanted sexual experience may be moderated by the extent to which individuals have shared information about their experience with others, as well as by their degree of perceived personal responsibility for the event’s occurrence. Each of these factors is theoretically relevant to the maintenance of SCE over time and may therefore influence the perpetuation of SCE in response to adult unwanted sexual experiences among individuals with BPD pathology.

With regard to the former, disclosure of SCE-eliciting potentially traumatic events is counter to the action tendencies associated with maladaptive SCE and may thus help regulate or lessen these SCE. For example, whereas shame motivates individuals to withdraw from others and hide perceived undesirable attributes and behaviors (e.g., Lindsay-Hartz, De Rivera, & Mascolo, 1995), acting consistent with these action tendencies is theorized to maintain SCE (Lewis, 1971; Brown, Rondero Hernandez, & Villarreal, 2011). Indeed, in one study, individuals who had kept their experiences of sexual assault a secret from others reported greater shame than those who had disclosed their experience to others (Vidal & Petrak, 2007). As such, acting opposite to these action tendencies (e.g., by increasing interpersonal approach behaviors and/or disclosing the event) is considered an effective strategy for reducing SCE (see Brown et al., 2011; Rizvi et al., 2011). Notably, Rizvi and Linehan (2005) found that acting opposite to the action tendencies associated with shame was effective in reducing shame about particular events among women with BPD in particular. Therefore, we expected that the association between BPD and SCE in response to unwanted sexual experiences would be particularly strong when the extent of sharing about the event was low.

The extent to which individuals hold themselves responsible for their unwanted sexual experience was also expected to influence the level of current event-related SCE among women with BPD. Although no research has examined the association between such self-blaming cognitions and SCE in response to unwanted sexual experiences in BPD, these cognitions have been linked to greater psychological distress in general among survivors of sexual assault (e.g., Frazier, 2003). Furthermore, treatments that address self-blaming cognitions (e.g., cognitive processing therapy) have been found to be effective in reducing SCE in response to traumatic events (e.g., Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, 2002). Thus, we expected that the association between BPD and current event-related SCE would be especially strong when the degree of perceived personal responsibility for the unwanted sexual experience was high.

Overall, the goal of the present study was to examine the associations between BPD pathology and SCE in response to adult unwanted sexual experiences among young adult women in the community, as well as the moderating roles of extent of sharing about the event and perceived personal responsibility for the event in these associations. We hypothesized that BPD pathology (across BPD diagnosis, symptom count, and symptom severity) would be associated with greater SCE in response to the unwanted sexual experience, both at the time of the event and currently. We also hypothesized that the associations between BPD pathology and current event-related SCE would be moderated by (1) the extent of sharing, and (2) perceived personal responsibility for the event.

Method

Participants

Participants were drawn from a large multi-site study of emotion dysregulation and sexual revictimization among young adult women in the community (the population most at risk for sexual victimization; see Breslau et al., 1998; Pimlott-Kubiak & Cortina, 2003). The larger study includes a representative community sample of young adult women drawn from four sites in the Southern and Midwestern United States (including Mississippi, Nebraska, and Ohio). Recruitment methods included random sampling from the community, in addition to community advertisements.

Participants for the current study included 303 young adult women who reported an unwanted sexual experience during adulthood (i.e., age 18 or older). Participants ranged in age from 18 to 25 years (M = 22.1, SD = 2.2) and were ethnically diverse (57.1% White; 23.1% African American; 6.6% Multiracial; 4.3% Latina; 3.3% Asian American). With regard to educational attainment, 94.1% of participants had received their high school diploma or GED, with many (75.2%) continuing on to complete at least some higher education. Approximately half the participants (47.5%) were full-time students, with an additional 9.2% enrolled part-time. Most participants (80.5%) were single.

Measures

Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time (BEST; Pfohl et al., 2009)

The BEST is a 15-item, self-report measure of BPD symptom severity and dysfunction over the past month. Rather than assessing the presence (vs. absence) of each BPD criterion, the BEST provides a dimensional assessment of the severity of BPD symptoms overall. Specifically, participants are asked to indicate the extent to which BPD-related thoughts, feelings, and behaviors resulted in distress and dysfunction on a scale from 1 (none/slight) to 5 (extreme). Research indicates that the BEST has adequate test-retest reliability, as well as good convergent and discriminant validity (Pfohl et al., 2009). The BEST was administered to the full sample to assess self-reported BPD symptom severity. Internal consistency in the present sample was adequate (α = .76).

Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders (DIPD-IV; Zanarini, Frankenburg, Sickel, & Young, 1996)

The BPD module of the DIPD-IV was administered to a subsample of women (n = 75) to obtain an interview-based assessment of BPD symptom count (i.e., the number of BPD criteria with threshold ratings), as well as BPD diagnostic status. The DIPD-IV has demonstrated good inter-rater and test-retest reliability for the assessment of BPD (Zanarini et al., 2000), with an inter-rater kappa coefficient of .68 and a test-retest kappa coefficient of .69. Interviews were conducted by bachelors- or masters-level clinical assessors trained to reliability with the second author (κ ≥ .80). All interviews were reviewed by the second author. Any discrepancies (found in fewer than 10% of cases) were discussed as a group and a consensus was reached. Participants who received the DIPD-IV met an average of 2.6 (SD = 2.4) criteria for BPD, with 18 women (24.0%) meeting full diagnostic criteria for BPD and an additional 16 women (21.3%) meeting criteria for subthreshold BPD.

Modified Sexual Experiences Survey (MSES; Messman-Moore, Walsh & DiLillo, 2010)

The MSES is an expanded version of the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss, Gidycz, & Wisiniewski, 1987) that was used to assess adult unwanted sexual experiences. The MSES assesses a range of unwanted sexual experiences occurring after the age of 18, ranging from verbally coercive sexual experiences to forcible rape. Modifications in the MSES include the assessment of specific sexual experiences in greater detail (e.g., additional questions were added regarding oral-genital contact). In addition, questions regarding substance-related victimization were modified according to suggestions by Muehlenhard, Powch, Phelps, and Giusti (1992). The MSES also includes a number of follow-up questions assessing reactions to the experience identified by the respondent as most upsetting. For example, participants are asked to report on the intensity of numerous emotions (e.g., ashamed, scared) both “at the time of the unwanted sexual activity (and shortly thereafter)” and “currently, when thinking about the unwanted sexual activity,” using a 5-point Likert-type scale. The MSES also obtains information on the number of different types of people the participant told about the unwanted sexual experience, as well as the degree to which they hold themselves responsible for the event’s occurrence (using a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from “not at all” to “very much”).

Participants in the present study reported experiencing at least one unwanted sexual experience (ranging from verbally coercive sexual experiences to forcible rape) during adulthood. The mean number of unwanted sexual experiences reported by the women in this sample was 4.8 (SD = 3.5), with the majority of women (82.5%) reporting at least one unwanted sexual experience involving the use or threat of physical force (42.6%) or occurring while they were incapacitated (54.5%).

Although all of the negative emotions assessed on the MSES are significantly correlated with one another (rs from .24 to .76, all ps italic> .001), they may be conceptualized as falling into two relatively broad categories: SCE (i.e. ashamed, guilty, angry at self) and more general negative affect (NA; i.e. sad, scared, numb, angry at other person). The conceptual distinction between NA in general and SCE in particular was supported by a principal components analysis using direct oblimin rotation. Specifically, the pattern matrix indicated that ashamed, guilty, and angry at self comprised one component (loadings from −.81 to −.92), whereas sad, scared, numb, and angry at other person comprised a second component (loadings from .68 to .92) with no significant cross-loadings (i.e. magnitude of loading > .30). As such, four composite scores were computed for use in subsequent analyses, including (1) SCE at event (α = .86), (2) current SCE (α = .87), (3) NA at event (α = .81), and (4) current NA (α = .79).

Procedure

All methods received prior approval by the Institutional Review Boards of all participating institutions. After providing written informed consent, participants completed the diagnostic interview. Following completion of the interview, participants completed a series of self-report questionnaires. All questionnaires were administered online and completed on a computer in the laboratory of one of the study sites. Participants were reimbursed $75 for this session (which included a laboratory assessment not included in the present study).

Results

Associations between BPD Pathology and SCE in Response to Unwanted Sexual Experiences

As shown in Table 1, BEST scores in the full sample were positively associated with SCE both at the time of the unwanted sexual experience and currently. The same associations were found for DIPD-IV symptom count in the subsample. Furthermore, partial correlations indicated that current SCE remained significantly associated with both BEST scores (r = .16, p bold> .01) and DIPD-IV symptom count (r = .24, p < .05) after taking into account both SCE at the time of the event and current NA. Finally, women with (vs. without) a DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis reported significantly greater SCE at the time of the event and currently. However, a univariate analysis of covariance indicated that the between-group difference in current SCE fell short of statistical significance after taking into account SCE at event and current NA (F(1, 72) = 3.08, p = .08).

Table 1.

Associations between BPD Pathology and Negative Emotions in Response to Unwanted Sexual Experiences

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

BPD Mean (SD) |

No BPD Mean (SD) |

F | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BPD Pathology | ||||||||||

| 1. BEST total score | -- | .54** | .45** | .25** | .32** | .18** | .25** | 33.53 (8.61) | 23.13 (8.97) | 18.65** |

| 2. DIPD-IV symptom count | -- | .81** | .29** | .35** | .16† | .17† | 6.00 (1.09) | 1.53 (1.47) | 142.55** | |

| 3. DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis | -- | .25* | .31** | .20* | .17† | -- | -- | -- | ||

| Trauma-Related Emotion | ||||||||||

| 4. SCE at event | -- | .65** | .65** | .52** | 12.11 (4.19) | 9.61 (4.27) | 4.72* | |||

| 5. Current SCE | -- | .46** | .67** | 9.44 (4.19) | 6.63 (3.52) | 7.97** | ||||

| 6. NA at event | -- | .73** | 17.33 (5.13) | 14.49 (6.42) | 2.93 | |||||

| 7. Current NA | -- | 12.78 (6.21) | 10.49 (5.54) | 2.20 | ||||||

Note: BEST = Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time; DIPD-IV = Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders. Analyses using the BEST were conducted in the full sample (N = 303), whereas those using the DIPD-IV were conducted in the subsample (n = 75).

p < .01;

p < .05;

p = .08.

Moderators of the Association between BPD Pathology and SCE in Response to Unwanted Sexual Experiences

Next, we examined two factors that may moderate the association between BPD pathology and SCE in response to unwanted sexual experiences: (1) the extent to which participants shared information about the experience with others, and (2) the extent to which participants viewed themselves as responsible for the event’s occurrence. To this end, we conducted a series of hierarchical multiple regression analyses with current event-related SCE as the outcome variable. In each analysis, SCE at the time of the event were entered in Step 1, followed by the relevant BPD variable and potential moderator in Step 2, and the interaction of the BPD and potential moderator variables in Step 3. The BPD and moderator variables were centered prior to creating the interaction terms. Significant interactions were probed using simple slopes analysis by examining whether the slopes of the regression lines for the BPD pathology variables differed significantly from zero at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of the moderators (Aiken & West, 1991).

Extent of sharing

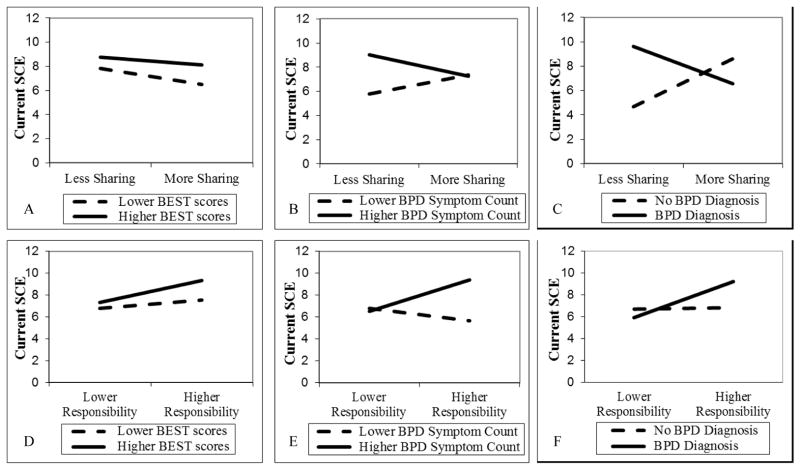

As shown in Table 2, SCE at the time of the event were positively associated with current event-related SCE in Step 1 for both the full sample and subsample. In Step 2 for the full sample, higher BEST scores and lesser extent of sharing were associated with higher current SCE. However, the interaction between BEST scores and extent of sharing was not significant in Step 3 (see Figure 1). In the subsample, DIPD-IV symptom count was the only variable uniquely associated with current SCE in Step 2; extent of sharing was not uniquely associated with current SCE in this subsample. However, the interactions between extent of sharing and both DIPD-IV symptom count and DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis were significant in Step 3. As shown in Figure 1, in the subsample of women interviewed with the DIPD-IV, when extent of sharing was high, neither DIPD-IV symptom count nor the presence of a DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis was significantly associated with current SCE (βs = −.02 and −.01, respectively; ps > .50); however, when the extent of sharing was low, both DIPD-IV symptom count and the presence of a DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis were significantly associated with greater current SCE (βs = .42 and .38, respectively; ps < .01).

Table 2.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression Analyses Examining Current Self-Conscious Emotions (SCE) in Response to an Adult Unwanted Sexual Experience

| Full Sample (N = 303)

|

Subsample (n = 75)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BEST

|

DIPD-IV Symptom Count

|

DIPD-IV BPD Diagnosis

|

|||||||

| ΔR2 | β | 95% CI | ΔR2 | β | 95% CI | ΔR2 | β | 95% CI | |

| Step 1 | .42** | .37** | .37** | ||||||

| SCE at event | .65** | 0.56, 0.73 | .61** | 0.42, 0.79 | .61** | 0.42, 0.79 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Step 2 | .04** | .04 | .03 | ||||||

| BPD Symptoms/Diagnosis | .16** | 0.07, 0.24 | .19** | 0.00, 0.38 | .18† | −0.01, 0.36 | |||

| Extent of Sharing | −.13** | −0.22, −0.05 | −.05 | −0.24, 0.14 | −.05 | −0.24, 0.14 | |||

| Step 3 | .00 | .04* | .04* | ||||||

| BPD x Extent of Sharing | .04 | −0.05, 0.13 | −.21* | −0.40, −0.03 | −.22* | −0.87, −0.33 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Step 2 | .05** | .08** | .08** | ||||||

| BPD Symptoms/Diagnosis | .15** | 0.07, 0.24 | .15 | −0.03, 0.34 | .14 | −0.04, 0.33 | |||

| Personal Responsibility | .17** | 0.09, 0.26 | .23* | 0.05, 0.41 | .24** | 0.06, 0.42 | |||

| Step 3 | .01† | .08** | .04* | ||||||

| BPD x Personal Responsibility | .08† | 0.00, 0.16 | .28** | 0.11, 0.42 | .26* | 0.04, 0.37 | |||

Note. BEST = Borderline Evaluation of Severity over Time; DIPD-IV = Diagnostic Interview for DSM-IV Personality Disorders.

p < .01;

p < .05;

p < .07.

Figure 1.

Interactions of BPD pathology with both extent of sharing (panels A through C) and perceived personal responsibility (panels D through F) in relation to current event-related self-conscious emotions (SCE) for both the full sample (panels A and D) and subsample (panels B, C, E, and F).

Perceived personal responsibility

Analyses examining the moderating role of perceived personal responsibility are presented in Table 2. In Step 2 for the full sample, both perceived personal responsibility and BEST scores were significantly positively associated with current SCE; however, the interaction of BEST scores and perceived personal responsibility fell just short of significance in Step 3 (p = .05). Notably, although both DIPD-IV symptom count and DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis failed to reach statistical significance in Step 2 within the smaller subsample, the interactions between perceived personal responsibility and both DIPD-IV variables (symptom count and BPD diagnosis) were significant in Step 3. As depicted in Figure 1, in the subsample, when perceived personal responsibility was low, neither DIPD-IV symptom count nor a DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis was significantly associated with levels of current SCE (βs = −.15 and −.10, respectively; ps > .20); however, when perceived personal responsibility was high, both DIPD-IV symptom count and the presence of a DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis were significantly associated with greater current SCE (βs = .37 and .31, respectively; ps < .01). As shown in Figure 1, the same pattern of results was found when exploring the interaction between BEST scores and perceived personal responsibility within the full sample of participants. Specifically, although BEST scores were not associated with levels of current SCE when perceived personal responsibility was low (β = .06, p > .30), they were significantly associated with greater current SCE (β = .22, p < .01) when perceived personal responsibility was high.

Discussion

As predicted, BPD pathology was associated with greater SCE in response to an unwanted sexual experience in adulthood, both at the time of the event and currently. Interestingly, the same was not true of other negative emotions experienced in response to this event (e.g., sadness, fear). These findings are consistent with past work indicating that individuals with BPD have a particular propensity for SCE (e.g., Rüsch, Corrigan et al., 2007), as well as with the assertion that such emotions are maintained because individuals with BPD have difficulties down-regulating SCE effectively (e.g., Rivzi et al., 2011).

Providing partial support for our hypotheses, in the subsample, the associations between both BPD symptom count and diagnosis on the DIPD-IV and current SCE in response to the unwanted sexual experience were moderated by the extent to which individuals had shared information about their experience with others. Specifically, BPD pathology on the DIPD-IV was associated with heightened levels of current event-related SCE only when the extent of sharing was low. These findings are consistent with past research indicating that disclosure of sexual assault experiences is associated with lower shame than non-disclosure (Vidal & Petrak, 2007), and provide further support for assertions that effective down-regulation of maladaptive SCE can be achieved through increasing interpersonal approach behavior (see Brown et al., 2011; Rizvi et al., 2011). Moreover, ours is the second study to indicate that acting in ways that are counter to the action tendencies of maladaptive SCE can help reduce such emotions. Specifically, whereas Rizvi and Linehan (2005) found that engaging in behaviors opposite to shame’s action tendencies (e.g., sharing vs. withdrawal from or non-disclosure to others) reduced event-specific shame among women with BPD, the current study found that engaging in behaviors consistent with the action tendencies of maladaptive SCE (i.e., disclosing the unwanted sexual experience to relatively fewer people) was associated with greater event-related SCE among women with BPD.

Perceived personal responsibility for the unwanted sexual experience also moderated the association between BPD pathology and current event-related SCE in the subsample, with both DIPD-IV symptom count and DIPD-IV BPD diagnosis exhibiting associations with heightened levels of current event-related SCE only among those who perceived their personal responsibility for the event as high. Thus, the present study extends past research indicating that perceived personal responsibility contributes to psychological distress in response to a sexual assault (e.g., Frazier, 2003) by demonstrating that perceived personal responsibility also influences the relation between BPD pathology and a particular form of distress – SCE – in response to unwanted sexual experiences. Moreover, our results suggest that the recognition and acknowledgement that one is not responsible for a potentially traumatic event (in this case, an unwanted sexual experience) may buffer at-risk individuals from experiencing SCE in response to these events. These findings also suggest that working to address and reduce perceived personal responsibility may help alleviate SCE in response to potentially traumatic events among individuals with BPD.

Notably, despite greater power in the analyses examining the associations between BPD symptom severity on the BEST and current SCE, neither extent of sharing about the event nor perceived personal responsibility for the event emerged as significant moderators of the BPD-SCE relation in the full sample of participants. However, it is important to note that the interaction between BPD symptom severity and perceived personal responsibility for the event fell just short of significance (p = .05) and results of the simple slope analyses revealed the same pattern as found when using the DIPD-IV variables in the subsample. Thus, results reveal a relatively robust relation between BPD pathology (assessed in multiple ways) and current event-related SCE when perceived personal responsibility for the event is high. Conversely, results revealed a different pattern of findings with regard to the moderating role of extent of sharing about the event when examining BPD symptom severity on the BEST (vs. BPD symptom count or diagnosis on the DIPD-IV). Specifically, results of analyses using the BEST revealed a positive association between BPD symptom severity and current SCE regardless of the extent of sharing about the event. This different pattern of findings may reflect differences in the assessment of BPD pathology in the self-report versus interview-based measures. In particular, given that the BEST provides a dimensional assessment of the level of distress and dysfunction associated with BPD symptoms, this measure may have greater overlap with self-report measures of negative emotional responses than BPD diagnostic interview (evidencing a stronger association with self-reported negative emotions than diagnostic interviews that seek only to identify threshold vs. subthreshold levels of different BPD symptoms). Alternatively, dimensional measures of BPD symptom severity may be less effective at distinguishing women with (vs. without) clinically-relevant levels of BPD pathology than interview-based measures of BPD that focus specifically on determining whether individuals reach a clinical threshold for various criteria. The ability to distinguish between groups high and low in clinically-relevant BPD pathology may be particularly important when examining the moderating role of extent of sharing (vs. perceived personal responsibility) on the BPD-SCE relation.

Findings must be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, the retrospective assessment of negative emotions at the time of the unwanted sexual experience introduces the potential for bias and may be influenced by the individual’s ability to recall or accurately report on their emotions at the time. Indeed, most participants (73.3%) were reporting on events that had happened over one year ago. Future studies would benefit from efforts to assess SCE closer in proximity to the time of the unwanted sexual experience (e.g., by recruiting from emergency rooms or police stations), in order to address any possible influence of retrospective report biases. Second, as with the only other study of BPD and event-specific SCE (Rizvi & Linehan, 2005), this study focused exclusively on women. Thus, further research is needed to examine whether disclosure of SCE-related events is equally helpful in reducing SCE among men with BPD pathology. Future research would also benefit from the use of more thorough measures of perceived personal responsibility. Nonetheless, it is promising that this and other studies that have utilized single-item measures of self-blame (e.g., Filipas & Ullman, 2006) have found the theoretically expected associations between self-blame and psychological problems.

Continued examination of the influence of interpersonal approach behavior on event-specific SCE in BPD will also be important in future research. For example, future studies should examine whether the extent of sharing moderates the associations between BPD and levels of SCE in response to other possible cues, including psychiatric hospitalization (Moses, 2011) or substance misuse (e.g., Dearing, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2005). Future research is also needed to explore whether the extent of sharing or perceived personal responsibility for specific outcomes influences the relationships between SCE and other forms of psychopathology (e.g., depression, social anxiety).

The results of the present study also have important clinical implications. Beyond providing additional support for existing recommendations to target SCE specifically when treating individuals with BPD (e.g., Rizvi et al., 2011), our results highlight the importance of teaching skills for effectively sharing information about potentially traumatic events with others. Indeed, it is possible that the quality of the response provided by the person with whom information is shared will influence the degree to which the extent of sharing is helpful in down-regulating SCE in response to these events. Moreover, our results regarding perceived personal responsibility suggest that self-blaming cognitions may exacerbate SCE in response to potentially traumatic events among women with BPD – consistent with past work indicating that treatments designed to reduce such cognitions also reduce trauma-related SCE (e.g., Resick et al., 2002). These findings suggest the potential utility of augmenting current treatments for SCE among individuals with BPD, which focus largely on teaching individuals to engage in behaviors opposite to the action tendencies of maladaptive SCE (see Rizvi & Linehan, 2005), with strategies aimed at reducing the frequency, severity, or believability of SCE-eliciting cognitions (including cognitive restructuring, cognitive defusion, and mindfulness).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant R01 HD062226, awarded to the last author (DD).

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publishing; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Amstadter AB, Vernon LL. Emotional reactions during and after trauma: A comparison of trauma types. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2008;16:391–408. doi: 10.1080/10926770801926492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews B, Brewin CR, Rose S, Kirk M. Predicting PTSD symptoms in victims of violent crime: The role of shame, anger, and childhood abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2000;109:69–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.109.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: The 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:626–632. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown B, Rondero Hernandez V, Villarreal Y. Connections: A 12-session psychoeducational shame resilience curriculum. In: Dearing RL, Tangney JP, editors. Shame in the therapy hour. Washington DC: APA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell SE, Beauchaine TP, Linehan MM. A biosocial developmental model of borderline personality: Elaborating and extending Linehan’s theory. Psychological Bulletin. 2009;135:495–510. doi: 10.1037/a0015616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing RL, Stuewig J, Tangney JP. On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:1392–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filipas HH, Ullman SE. Child sexual abuse, coping resources, self-blame, posttraumatic stress disorder, and adult sexual revictimization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2006;21:652–672. doi: 10.1177/0886260506286879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Bateman A. The development of borderline personality disorder – A mentalizing model. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2008;22:4–21. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2008.22.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier PA. Perceived control and distress following sexual assault: A longitudinal test of a new model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;84:1257–1269. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.84.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jovev M, Jackson HJ. Early maladaptive schemas in personality disordered individuals. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2004;18:467–478. doi: 10.1521/pedi.18.5.467.51325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA, Wisiniewski N. The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1987;55:162–170. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.55.2.162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SN, Abueg FR, Manke FP, Brennan JM, Stahura C. Development and validation of the trauma-related guilt inventory (TRGI) Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:428–444. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HB. Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: International Universities Press; 1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis M, Sullivan MW, Stangor C, Weiss M. Self development and self-conscious emotions. Child Development. 1989;60:146–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay-Hartz J, De Rivera J, Mascolo MF. Differentiating guilt and shame and their effects on motivation. In: Tangney JP, Fischer KW, editors. Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, and embarrassment. New York: Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McGowan A, King H, Frankenburg FR, Fitzmaurice G, Zanarini MC. The course of adult experiences of abuse in patients with borderline personality disorder and Axis II comparison subjects: A 10-year follow-up study. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2012;26:192–202. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2012.26.2.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Walsh K, DiLillo D. Emotion dysregulation and risky sexual behavior in revictimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34:967–976. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2010.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses T. Stigma apprehension among adolescents discharged from brief psychiatric hospitalization. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2011;199:778–789. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e31822fc7be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muehlenhard CL, Powch IG, Phelps JL, Giusti LM. Definitions of rape: Scientific and political implications. Journal of Social Issues. 1992;48(1):23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Ogata SN, Silk KR, Goodrich S, Lohr NE, Westen D, Hill EM. Childhood sexual and physical abuse in adult patients with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:1008–1013. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.8.1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfohl B, Blum N, St John D, McCormick B, Allen J, Black DW. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Evaluation of Severity Over Time (BEST): A self-rated scale to measure severity and change in persons with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2009;23:281–293. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2009.23.3.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pimlott-Kubiak S, Cortina LM. Gender, victimization, and outcomes: Reconceptualizing risk. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2003;71:528–539. doi: 10.1037/0022-006x.71.3.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resick PA, Nishith P, Weaver TL, Astin MC, Feuer CA. A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:867–879. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.4.867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Brown MZ, Bohus M, Linehan MM. The role of shame in the development and treatment of borderline personality disorder. In: Dearing RL, Tangney JP, editors. Shame in the therapy hour. Washington DC: APA; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Linehan MM. The treatment of maladaptive shame in borderline personality disorder: A pilot study of “opposite action. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice. 2005;12:437–447. [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Corrigan PW, Bohus M, Kühler T, Jacob G, Lieb K. The impact of posttraumatic stress disorder on dysfunctional implicit and explicit emotions among women with borderline personality disorder. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2007;195:537–539. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318064e7fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rüsch N, Lieb K, Gottler I, Hermann C, Schramm E, Richter H, et al. Shame and implicit self-concept in women with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:500–508. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.3.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skodol AE, Siever LJ, Livesley WJ, Gunderson JG, Pfohl B, Widiger TA. The borderline diagnosis II: Biology, genetics, and clinical course. Biological Psychiatry. 2002;51:951–963. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01325-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Tracy JL. Self-conscious emotions. In: Leary MR, editor. Handbook of self and identity. New York: Guilford Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Vidal ME, Petrak J. Shame and adult sexual assault: A study with a group of female survivors recruited from an East London population. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. 2007;22:159–171. [Google Scholar]

- Young JE. Cognitive therapy for personality disorders: A schema focused approach. Sarasota, FL: Practitioner’s Resources Exchange; 1999. (Revised Edition) [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Marino MF, Reich DB, Haynes MC, Gunderson JG. Violence in the lives of adult borderline patients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 1999;187:65–71. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199902000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Williams A, Lewis R, Reich R, Vera S, Marino M, et al. Reported pathological childhood experiences associated with the development of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;154:1101–1106. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.8.1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Sickel AE, Young L. Diagnostic interview for DSM-IV personality disorders. Boston, MA: McLean Hospital; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Zanarini MC, Skodol AE, Bender D, Dolan R, Sanislow C, Schaefer E, Gunderson JG. The collaborative longitudinal personality disorders study: Reliability of axis I and axis II diagnoses. Journal of Personality Disorders. 2000;14:291–299. doi: 10.1521/pedi.2000.14.4.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]