Abstract

p38δ mitogen activated protein kinase (MAPK) is a unique stress responsive protein kinase. While the p38 MAPK family as a whole has been implicated in a wide variety of biological processes, a specific role for p38δ MAPK in cellular signalling and its contribution to both physiological and pathological conditions are presently lacking. Recent emerging evidence, however, provides some insights into specific p38δ MAPK signalling. Importantly, these studies have helped to highlight functional similarities as well as differences between p38δ MAPK and the other members of the p38 MAPK family of kinases. In this review we discuss the current understanding of the molecular mechanisms underlying p38δ MAPK activity. We outline a role for p38δ MAPK in important cellular processes such as differentiation and apoptosis as well as pathological conditions such as neurodegenerative disorders, diabetes, and inflammatory disease. Interestingly, disparate roles for p38δ MAPK in tumour development have also recently been reported. Thus, we consider evidence which characterises p38δ MAPK as both a tumour promoter and a tumour suppressor. In summary, while our knowledge of p38δ MAPK has progressed somewhat since its identification in 1997, our understanding of this particular isoform in many cellular processes still strikingly lags behind that of its counterparts.

1. p38 Isoform Evolution

The first and now archetypal member of the p38 MAPK family, p38α MAPK, was identified by four independent groups in 1994. It was isolated as a 38 kDa protein rapidly tyrosine phosphorylated in response to lipopolysaccharide stimulation [1], as a molecule that binds pyridinyl-imidazole drugs which inhibit the synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines [2] and as an activator of MAPK activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAP-K2/MK2) and small heat shock proteins in cells stimulated with heat shock or interleukin- (IL-) 1 [3, 4]. This was followed by the subsequent identification of p38β MAPK in the same year, p38γ MAPK in 1996, and lastly p38δ MAPK in 1997 [5–9]. The product of the S. cerevisiae HOG1 gene, an important component of osmoregulation and the cell cycle, was found to be a homologue of p38 MAPK [10]. This conservation from yeast to mammals is significant as it indicates that the p38 family is responsible for critical cellular processes. A study of the evolutionary history of MAPKs suggests that each p38 MAPK family member evolved from a single ancestor. In fact it appears that MAPK12 (p38γ) arose from a tandem duplication of MAPK11 (p38β) on chromosome 22 while MAPK14 (p38α) and MAPK13 (p38δ) subsequently resulted from a single segmental duplication of the MAPK11-MAPK12 gene unit on chromosome 6 [11]. These gene duplications appear to have occurred before the species separation of nematodes but after the species separation of arthropods. Interestingly, unlike the other p38 isoforms, MAPK13 has not been identified in teleosts [11]. This indicates that a MAPK13 gene deletion event may have occurred subsequent to gene duplication in the evolution of these species. Duplicated genes are generally assumed to be functionally redundant at the time of origin and are eventually silenced. The evolutionary preservation of the four p38 MAPK isoforms therefore suggests functional differentiation of the individual family members. Thus, while the majority of research to date has focused on p38α and p38β MAPKs, each isoform is an important kinase in its own right with distinct cellular functions. This review aims to highlight components of the previously neglected p38δ MAPK signalling pathway and emphasises recent progress in our understanding of p38δ MAPK involvement in diverse physiological as well as pathological processes.

The use of pyridinyl-imidazole inhibitors has largely driven the advancement in our understanding of p38α and p38β MAPK signalling, functions, and substrates. Both p38α and p38β MAPK are highly sensitive to inhibition by SB203580, SB202190, and newer compounds such as L-167307 [2, 5, 12]. In contrast, the observation that p38δ MAPK is insensitive to inhibition by pyridinyl-imidazole compounds has hindered its study in cellular events [7, 9]. The differential sensitivity to these drugs can be attributed to amino acid sequence variability at the ATP binding pocket where these compounds bind competitively, facilitated by interactions with nearby amino acids. Thr106 of p38α and p38β MAPK has been identified as the major determinant for imidazole inhibitor specificity as it orientates the drug to interact with His107 and Leu108 thereby preventing ATP binding [13]. The equivalent residue in p38δ MAPK is a methionine (Met), the large side chain of which prevents binding of these inhibitors. In fact, substitution of Met106 in p38δ MAPK with Thr was found to confer some sensitivity to inhibition by SB203580 [14]. Conversely, p38α MAPK mutants in which Thr106 is replaced with Met displayed reduced sensitivity to inhibition by SB203580 [15]. It is unfortunate that no potent p38δ MAPK specific inhibitor has been identified to date. Although the diaryl urea compound BIRB796 allosterically inhibits p38δ MAPK at high concentrations, it is also a powerful inhibitor of p38α, -β, and -γ MAPK [16]. While varying the concentration of BIRB796 and combining it with SB203580 may be of some use in identifying p38δ MAPK specific signalling pathways, the possible influence of the other p38 MAPK isoforms, in particular p38γ MAPK, must be considered when interpreting any results.

2. p38δ MAPK Expression and Activation

Unsurprisingly, p38δ MAPK shares highly similar protein sequences with the other p38 MAPK isoforms. It displays 61%, 59%, and 65% amino acid identity to p38α, -β, and -γ MAPKs, respectively [7]. Differences in sequence between p38δ MAPK and the other p38 MAPK family members can be observed in the ATP binding pocket. This has consequences for inhibitor sensitivity and contributes to substrate specificity. On the other hand, the greatest sequence similarities lie in the highly conserved kinase domains, where the four isoforms share >90% amino acid identity [17]. Within kinase subdomain VIII (of XI), p38δ MAPK possesses a TGY dual phosphorylation motif which is the hallmark of p38 MAPKs and is conserved among all known mammalian p38 isoforms [7–9, 18]. p38δ MAPK has a distinct distribution profile in human tissue that is relatively limited compared to that of p38α and p38β MAPK isoforms which are largely ubiquitously expressed [8]. High levels of p38δ mRNA have been detected in endocrine tissues such as salivary, pituitary, prostate, and adrenal glands, while more modest levels are expressed in the stomach, colon, trachea, pancreas, skin, kidney, and lung [8]. This differential expression in different cell and tissue types is indicative of a specific biological effect of p38δ MAPK activation in these cell types, distinct from that of the other p38 family members.

The murine p38δ MAPK amino acid sequence is 92% identical to the human sequence and the adult mouse displays a broadly similar pattern of p38δ MAPK expression to that seen in human tissue, that is, lung, testis, kidney, and gut epithelium [18]. Murine p38δ MAPK expression varies at different stages in the developing mouse embryo. At 9.5 days it is primarily expressed in the developing gut and septum transversum, while by 15.5 days its expression expands to most developing epithelia [18]. This suggests that p38δ MAPK has a role in embryonic development. However, knock-out of p38δ MAPK results in mice which are both viable and fertile and exhibit a normal phenotype [19]. Moreover, while p38β- and p38γ-null mice as well as p38γ/p38δ double knockout (KO) mice are also phenotypically normal [19, 20], genetic ablation of p38α MAPK is embryonic lethal at day 10.5–11.5 [21]. Functional redundancy among the p38 isoforms is a likely explanation with p38α, -β, or -γ compensating for the loss of p38δ MAPK activity during development. However, it appears that p38α MAPK plays a critical role in early development where its loss cannot be overcome.

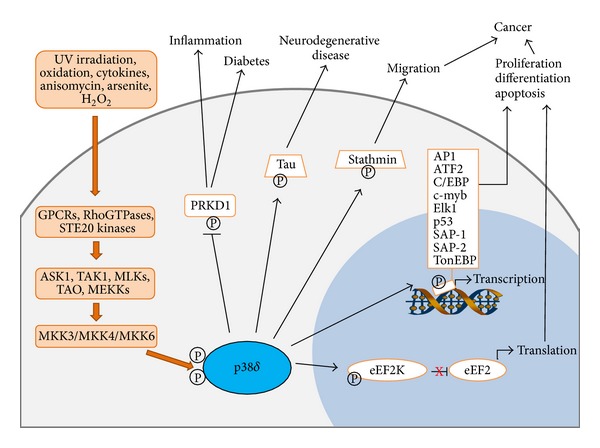

p38α, -β, and -γ MAPK isoforms are activated by alterations in the physical and chemical properties of the extracellular environment with diverse triggers including environmental stress signals, inflammatory cytokines, and mitogenic stimuli [1, 5, 6, 22]. Using transiently expressed epitope-tagged p38δ MAPK, a similar activation profile has been defined for p38δ MAPK [7–9]. It is strongly activated by environmental alterations in osmolarity, ultraviolet (UV) irradiation, and oxidation. It is also moderately activated by chemical stressors and proinflammatory cytokines including arsenite, anisomycin, tumour necrosis factor- (TNF-) α, and IL-1. Despite their similar activation profiles, differences in the levels of activation of p38δ MAPK and the other p38 MAPK isoforms have been reported. For example, while hyperosmolarity appears to stimulate both p38α and p38δ to a similar degree, under hypoosmotic conditions, p38α MAPK is more strongly activated than p38δ MAPK [7]. A range of MAP3Ks have been implicated in the activation of the p38 MAPK pathway, including MLKs (mixed-lineage kinases), TAK1 (transforming growth factor β activated kinase 1), ASK1 (apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1), TAO (thousand-and-one amino acid), DLK1 (dual-leucine-zipper-bearing kinase 1) MEKKs, and ZAK1 (leucine zipper and sterile-α motif kinase 1) (Figure 1). To date their individual contribution to p38δ MAPK signalling in particular is not yet understood [23–28]. Further upstream of the MAP3Ks is a complex network involving members of the Ras/Rho family of small GTP-binding proteins and heterotrimeric G-protein coupled receptors [29, 30]. This adds to the diversity of signalling from various stimuli contributing to the crosstalk between p38 MAPKs and other signalling pathways.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the current understanding of p38δ MAPK signalling and activation. A variety of extracellular stimuli can activate the MAPK signalling pathway resulting in dual phosphorylation of p38δ MAPK. Known substrates of active p38δ MAPK include transcription factors, structural proteins, kinases, and translation repressors. Phosphorylated substrates affect several cellular processes and contribute to the pathogenesis of diseases such as cancer, diabetes, and neurodegenerative and inflammatory conditions.

The upstream direct activators responsible for dual phosphorylation of the p38 MAPK TGY motif are the MAPK kinases (MKKs). p38δ MAPK is unique as it can be activated by four separate MKKs: the p38 MAPK specific MKK3 and MKK6 and also the JNK MKKs-4 and -7 [7–9, 18]. However, information regarding the specific contributions of these individual MKKs to p38δ MAPK activation in different cell types and under diverse conditions is lacking. Current evidence suggests that activation of p38δ MAPK is significantly influenced by both the nature and the strength of the stimulus as well as the cell type involved. This may be the result of varying levels of expression of upstream components of the MAPK signalling cascade in different cell types. For example, MKK3 is the major direct activator of p38δ MAPK phosphorylation in response to UV radiation, hyperosmotic shock, and TNFα in mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEF) cells [31]. It also appears to be the primary kinase responsible for p38δ MAPK activation in response to transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) as MKK3 deficiency impairs endogenous p38δ activation by TGF-β1 in murine glomerular mesangial cells [32]. On the other hand, MKK6 was identified as the major activator of p38δ MAPK in KB (HeLa) cells subjected to IL-1, anisomycin, or osmotic stress [9]. Furthermore, MKK7 is reported to be responsible for the activation of p38δ MAPK in 293T cells under peroxide stress, mediated by the scaffolding action of islet brain-2 [33]. Further complicating the current understanding of p38δ MAPK activation is the likelihood that, in some cases, the cooperation of two MKKs may be necessary. While MKK4 preferentially phosphorylates JNK on Tyr, MKK7 preferentially phosphorylates JNK on Thr [34–36]. Therefore it must be considered possible that the combined activity of these two MKKs may be required to fully phosphorylate p38δ MAPK on both the Tyr and the Thr residues. Interestingly, two reports outline a MKK-independent mechanism of activation for p38α MAPK via autophosphorylation [37, 38]. While autophosphorylation activity is detected in intrinsically active p38δ mutants [39, 40], no such pathway has been observed which activates the endogenous p38δ MAPK isoform.

An important factor in determining the biological consequences of p38δ MAPK phosphorylation is the strength and duration of the activation signal. p38δ MAPK activation is largely transient with activation and downregulation occurring within minutes of stimulation [17]. This is due to the regulatory action of protein phosphatases which again appears to be cell-type specific. While MAPK phosphatase 1 inactivates p38δ MAPK in HEK293FT cells, it does not interact with p38δ MAPK in the NIH3T3 cell line [41, 42]. The protein serine/threonine phosphatases PP1 and PP2A have also been shown to be involved in p38δ MAPK phosphorylation as okadaic acid (OA), a PP1/PP2A inhibitor, causes increased p38δ MAPK activity in human epidermal keratinocytes [43].

3. Novel p38δ MAPK Substrates

While p38 MAPKs are proline-directed kinases, substrate specificity is also determined by docking domains both in the MAPK itself and in the target protein [44]. Therefore, although p38δ MAPK substrate specificity overlaps to some extent with that of p38α, -β, and -γ MAPKs, there are a number of notable differences. Common substrates of p38 MAPKs include MBP, PHAS-1, and transcription factors ATF2, SAP1, Elk-1, and p53 (Figure 1). In contrast, however, substrates such as MAPK activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAP-K2) and MAPKAP-K3 which are the major downstream kinases of p38α and p38β MAPK are not phosphorylated by p38δ MAPK [7–9, 45] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Known p38δ MAPK substrates and their biochemical functions.

| Substrate | Function | Consequences of phosphorylation |

|---|---|---|

| AP1 | Transcription factor | Activation of transcription, involucrin expression, keratinocyte differentiation [58] |

| ATF2 | Transcription factor | Activation of transcription [7, 9] |

| C/EBP | Transcription factor | Keratinocyte differentiation [59] |

| c-myb | Transcription factor | c-myb degradation [109] |

| eEF2K | Inhibitory kinase | eEF2 activation, protein synthesis [53] |

| Elk1 | Transcription factor | Activation of transcription [7, 9] |

| p53 | Transcription factor | p21 expression, G1 phase arrest [9, 110] |

| PHAS-1 | Translation repressor | Dissociation from eIF4E, activation of translation [7] |

| PRKD1 | Serine-threonine kinase | Inhibition of PRKD1 activity [72] |

| SAP-1 | Transcription factor | Activation of transcription [9] |

| SAP-2 | Transcription factor | Activation of transcription [9] |

| Stathmin | Microtubule protein | Cytoskeleton reorganisation [50] |

| Tau | Microtubule protein | Microtubule assembly, tau self-aggregation [46] |

| TonEBP/OREBP | Transcription factor | Impaired TonEBP/OREBP transcriptional activity [41] |

AP1: activator protein 1; ATF2: activating transcription factor 2; C/EBP: CCAAT (cytosine-cytosine-adenosine-adenosine-thymidine)-enhancer-binding protein; myb: myeloblastosis; eEF2K: eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase; eEF2: eukaryotic elongation factor 2; PHAS-1: phosphorylated heat- and acid-stable protein 1; PRKD1: protein kinase D 1; SAP: serum response factor accessory protein; eIF4E: eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E.

3.1. Tau

At the time p38δ MAPK was first described the microtubule-associated protein tau was identified as a strong in vitro substrate for p38δ MAPK [46]. Tau is a component of the cytoskeleton network and under normal conditions it stabilises microtubule assembly by binding to β-tubulin. Phosphorylation of tau at T50 by p38δ MAPK causes it to be functionally modified and enhances its capacity to promote microtubule assembly. This effect is seen in neuroblastoma in response to osmotic shock where tau T50 phosphorylation occurs soon after p38δ MAPK activation, aiding the adaptive response of neurons to changes in osmolarity [46]. It appears, however, that subsequent hyperphosphorylation of tau at additional sites causes it to dissociate from the cytoskeleton, thereby promoting its self-assembly [47]. This aggregation destabilises the microtubule network and contributes to the development of neurofibrillary tangles [48]. Notably, Alzheimer's disease and other neurodegenerative disorders known as tauopathies are characterised by the aggregation in the brain of these neurofilament structures [49]. There is therefore a clearly defined role for p38δ MAPK in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative disease, making it a good potential therapeutic target for these disorders.

3.2. Stathmin

There is further evidence of a role for p38δ MAPK in cytoskeleton regulation as the microtubule-associated protein stathmin has also been characterised as a good p38δ MAPK substrate in vitro and in transfected cells exposed to osmotic shock [50]. The normal physiological role of stathmin is to sequester free tubulin and increase depolymerisation of microtubules [51, 52]. It is possible that phosphorylation of stathmin by p38δ MAPK blocks its ability to destabilise microtubules and as a result promotes microtubule polymerisation and enhances cell survival under stress conditions.

3.3. eEF2K

In response to anisomycin stimulation, p38δ MAPK has been shown to be the main p38 MAPK isoform which phosphorylates eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase (eEF2K) [53]. Phosphorylation of eEF2K on Ser359 inactivates the kinase and as a result removes its inhibitory phosphorylation of eEF2. eEF2 in turn promotes the movement of the ribosome along mRNA during translation [54]. This suggests that, by inhibiting eEF2K and consequently activating eEF2, p38δ MAPK is responsible for driving the translation of proteins associated with stress responses. Consistent with this hypothesis is the observation that the MKK3/6-p38δ MAPK-eEF2K pathway in myeloid cells is implicated in the production of the proinflammatory cytokine TNFα in bacterial LPS induced acute liver disease [55]. These differences in substrate specificity in combination with its unique tissue distribution profile demonstrate that despite similarities in stimuli the consequences of p38δ MAPK can potentially be significantly different to those of the other p38 MAPK isoforms.

4. p38δ MAPK Function and New Roles in Human Disease

Since the discovery of p38δ MAPK in 1997 it has been implicated in a range of diverse physiological events, namely, differentiation, apoptosis, and cytokine production (Figure 1). The greatest understanding of its involvement in these cellular processes has been achieved from work using keratinocytes and the majority of these studies have previously been reviewed [56, 57]. Research is now emerging which establishes p38δ MAPK as a regulator of these processes in other cell types. As a result in the past five years p38δ MAPK has also been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetes, inflammatory diseases, and cancer. This progress has been achieved with the development of p38δ MAPK KO mouse models which are proving to be a useful tool in elucidating novel roles for p38δ MAPK in vivo.

4.1. Differentiation and Psoriasis

A number of different studies have identified a role for p38δ MAPK in keratinocyte differentiation, a process critical for the precise control of normal epidermal homeostasis. p38δ MAPK induces keratinocyte differentiation by regulating the expression of involucrin, a marker of keratinocyte terminal differentiation [58–60]. p38δ MAPK activation by 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA), calcium, OA, or green tea polyphenol corresponds with increased involucrin promoter activity, mRNA, and protein expression, as well as increased levels and activity of AP1 and C/EBP transcription factors [58, 59, 61]. Importantly, these responses are observed in the presence of a p38α/β MAPK inhibitor. In addition p38γ MAPK is poorly expressed in keratinocytes [60] confirming a specific role for p38δ MAPK. Involucrin expression can also be further upregulated in keratinocytes coexpressing p38δ MAPK and PKCη, -δ or ε isoforms [59]. Of note cholesterol-depleting agents and overexpression of MKK6/MKK7 have previously been shown to induce involucrin expression via activation of p38α MAPK [60, 62, 63]. This highlights the significance of the stimulus type in determining p38 MAPK isoform activation. A further role for p38δ MAPK in keratinocyte differentiation was recently identified. p38δ MAPK can regulate expression of ZO-1, an epidermal tight junction membrane protein associated with keratinocyte differentiation [64]. Inhibition of p38δ MAPK results in depletion of ZO-1 protein in calcium induced differentiating keratinocytes while other junction proteins remain unaffected [64]. Psoriasis is a benign, chronic inflammatory skin condition that is characterised by hyperproliferation and differentiation of keratinocytes as well as increased expression of inflammatory cytokines. Given the significant role p38δ MAPK plays in keratinocyte differentiation, it is no surprise that aberrant p38δ MAPK signalling has been implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis. Expression of the MAPK13 gene is commonly upregulated in psoriasis [65]. Furthermore, an increase in p38δ (as well as -α and -β) MAPK activity has been detected in psoriatic lesions compared to nonlesional psoriatic skin. After treatment for psoriasis, phosphorylated p38 MAPK levels return to those of uninvolved skin [66].

Further to its role in keratinocyte differentiation p38δ MAPK is also implicated in hematopoiesis. In human primary erythroid cells, p38δ MAPK mRNA is only expressed in late-stage differentiation where along with p38α MAPK it is increasingly activated [67]. This may suggest a functional role for p38δ MAPK in erythrocyte membrane remodelling and enucleation. Interestingly, an increase in p38δ MAPK mRNA and protein expression is observed as blood monocytes differentiate to macrophages [68]. This suggests a role for p38δ MAPK in functions gained by mature macrophages. A possible candidate is phagocytosis given that the microtubule associated protein stathmin is such a strong p38δ MAPK substrate.

Most recently, p38δ MAPK has been identified as a component of differentiation in bone repair [69]. In bone cell differentiation during wound healing, wild type (WT) monocytes differentiate to calcifying/bone-forming monoosteophils upon treatment with the peptide LL-37. p38δ MAPK protein and mRNA is highly expressed in monoosteophils compared to undifferentiated monocytes. Monocytes from p38δ MAPK KO mice are incapable of this differentiation, suggesting a critical role for p38δ MAPK in this process [69].

4.2. Apoptosis and Diabetes

As well as its significant role in keratinocyte differentiation, p38δ MAPK has also been identified as a regulator of keratinocyte apoptosis. This dual functional role may be attributed to the overlap of differentiation and apoptosis signalling pathways [70]. As well as inducing involucrin expression [61], OA simultaneously causes disruption of mitochondrial membrane potential and caspase-dependent apoptosis [43]. Overexpression of p38δ MAPK enhances this OA driven apoptotic morphology. This response is specific to p38δ MAPK activation as it occurred in the presence of the p38α/β MAPK inhibitor SB203580 [43]. Furthermore, p38δ MAPK coexpressed with either MEK6 or PKCδ, both upstream p38 MAPK activators, elicited an apoptotic response similar to that induced by OA but in the absence of an external stimulus. This was also independent of SB203580, again ruling out a contribution from other p38 MAPK isoforms [71]. Interestingly, concurrent p38δ MAPK activation and inactivation of the proproliferative MAPK ERK1/2 were observed with OA stimulation and PKCδ/p38δ MAPK coexpression [43, 61, 71]. In fact a reduction in ERK1/2 activation appears to be critical for apoptosis as its constitutive activation inhibited PKCδ/p38δ MAPK mediated apoptosis [71]. Therefore, it is likely that a specific balance between prosurvival ERK1/2 and proapoptotic p38δ MAPK is essential in determining keratinocyte fate. In regulating this balance, p38δ MAPK and ERK1/2 form a complex that is translocated to the nucleus upon stimulation by PKCδ. This nuclear localisation facilitates ERK1/2 inactivation by nuclear phosphatases, while maintaining p38δ MAPK activation [71].

A role for p38δ MAPK in apoptosis has recently been demonstrated in vivo using p38δ MAPK KO mice. Mice deficient in p38δ MAPK displayed a fivefold lower rate of pancreatic β cell death in response to oxidative stress than WT mice and are afforded protection against insulin resistance induced by a high-fat diet [72]. This would appear to link p38δ MAPK to the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus, a disease characterised by reduced insulin sensitivity and a decrease in insulin-producing pancreatic β cells [72]. Increased p38 MAPK pathway activity has indeed been observed in both type 1 and type 2 diabetes and is correlated with late complications of hyperglycemia, including neuropathy and nephropathy [73, 74]. p38δ MAPK specifically has also been implicated in the regulation of insulin secretion. Phosphorylation by p38δ MAPK negatively regulates the activity of protein kinase D1 (PKD1), a known positive regulator of neuroendocrine cell secretion [72]. Thus, pronounced activation of PKD1 has been observed in pancreatic β cells lacking p38δ MAPK. As p38δ MAPK is normally quite highly expressed in the pancreas this can contribute to heightened insulin secretion and improved glucose tolerance in p38δ MAPK-null mice [72]. The pivotal role p38δ MAPK plays in integrating insulin secretion and survival of pancreatic β cells makes it an attractive potential therapeutic target for the treatment of human diabetes.

4.3. Cytokine Production and Inflammatory Diseases

One of the pathways by which p38α MAPK was discovered was via its identification as a regulator of proinflammatory cytokine biosynthesis [2]. Thus, its role in cytokine signalling and cytokine-dependent inflammatory diseases is well characterised. Consequently, some recent research using p38δ MAPK KO mouse models has focused on identifying specific roles for p38δ MAPK in inflammation. A study of p38δ MAPK KO mice as well as myeloid-restricted deletion of p38δ MAPK in mice has shown that p38δ MAPK is required for the recruitment of neutrophils to sites of inflammation [75]. p38δ MAPK and its downstream target PKD1 conversely regulate PTEN activity to control neutrophil extravasation and chemotaxis. The accumulation of neutrophils at inflammatory sites is known to trigger inflammation-induced acute lung injury (ALI) which can cause acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), a condition with a high mortality rate [76]. Therefore, abnormal p38δ-PKD1 signalling may play an important role in both ALI and ARDS in humans.

Rheumatoid arthritis is a typical example of an inflammatory disease involving chronic synthesis of proinflammatory cytokines which result in synovial hyperplasia and joint destruction [77]. While p38δ MAPK (along with -α, -β, and -γ) is expressed in the synovium of rheumatoid arthritis patients its level of activation is lower than that of the four other p38 MAPK isoforms [78]. Despite this low level of activation new research has identified p38δ MAPK as an essential component of joint damage in a collagen-induced model of arthritis. p38γ/δ −/− mice displayed reduced arthritis severity compared to WT mice [79]. The decrease in joint destruction was associated with lower expression of IL-1β and TNFα as well as a reduction in T cell proliferation, IFNγ, and IL-17 production. Lack of either p38γ or p38δ MAPK alone yielded intermediate effects, suggesting significant roles for both isoforms in arthritis pathogenesis.

Proinflammatory cytokines also play a significant role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory airway diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and cystic fibrosis. While increased mucus production is linked to the morbidity and mortality of such diseases the underlying molecular mechanisms remain somewhat unclear [80]. The critical driver of mucus production is thought to be IL-13 production by immune cells which results in mucin gene expression [81, 82]. In the last few years p38δ MAPK has been implicated in the signalling pathway responsible for controlling IL-13 driven excess mucus production. Increased MAPK13 gene expression is evident in the lungs of patients with severe COPD [83]. Novel inhibitors with increased activity against p38δ MAPK blocked mucus production by IL-13 in human airway epithelial cells [83]. Thus, in patients with hypersensitivity airway diseases there exists a potential opportunity for therapeutic intervention should specific p38δ MAPK inhibitors become clinically available.

5. p38δ MAPK and Cancer

In recent years, the function of the p38 MAPK signalling pathway in malignant transformation has been intensively studied. As a result, the best characterised isoform, p38α MAPK, has been identified as both a tumour promoter [84–86] and a tumour suppressor [87–89]. Recent studies have now also implicated p38δ MAPK in cancer development and progression. Like p38α MAPK, p38δ MAPK would also appear to have both pro- and antioncogenic roles, depending on the cell type studied.

Interest in p38δ MAPK as a potential tumour promoter is based on the evidence that p38δ MAPK expression and activation are significantly increased in a variety of carcinoma cell lines such as human primary cutaneous squamous carcinoma cells [65], head and neck squamous carcinoma cells and tumours [85], cholangiocarcinoma, and liver cancer cell lines [90]. p38δ MAPK was first shown to promote a malignant phenotype (over eight years ago) in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) [85]. It was shown to regulate HNSCC invasion and proliferation through controlling expression of matrix metalloproteinase-1 and -13 [85, 91]. Moreover the expression of dominant-negative p38δ MAPK impaired the ability of cutaneous HNSCC cells to implant in the skin of immunodeficiency mice as well as inhibiting the growth of xenografts [85].

p38δ MAPK-null mice have been utilised to demonstrate that p38δ MAPK is required for the development of multistage chemical skin carcinogenesis in vivo. When compared with WT mice, p38δ MAPK-deficient mice displayed reduced susceptibility to 7, 12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene/12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate induced skin carcinoma with a significant delay in tumour development [92]. Furthermore, both tumour numbers and size were significantly decreased compared with WT mice [92]. This decreased carcinogenesis was associated with reduced levels of proproliferative ERK1/2-AP1 signalling and decreased activation of signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) [92]. The ERK1/2-AP1 pathway is a key cancer promoting cascade previously implicated in skin carcinogenesis [93, 94]. Stat3 meanwhile is an oncogenic transcription factor involved in chemical and UVB-induced transformation [95]. It is also proproliferative and plays a role in angiogenesis and invasion [96, 97]. Therefore p38δ MAPK promotion of proliferation via Stat3 may be a significant mechanism in the promotion of carcinogenesis by p38δ MAPK. Similarly, p38δ MAPK KO mice have reduced susceptibility to development of K-ras driven lung tumorigenesis. Compared with WT mice, p38δ −/−/K-RasG12D+/− mice displayed significantly decreased tumour numbers, average tumour volume, and total tumour volume per lung [92]. This is in contrast to p38α MAPK-deficient mice which display hyperproliferation of lung epithelium and increased K-Ras-induced lung tumour development [88]. This highlights once again the distinct and often opposing functions of the individual p38 MAPK isoforms.

Further evidence for a specific role of p38δ MAPK in promoting cancer progression has most recently been demonstrated in cholangiocarcinoma (CC) [90]. p38δ MAPK expression is upregulated in CC when compared with normal biliary tract tissue. Knockdown, however, of p38δ MAPK expression by siRNA transfection significantly inhibited motility and invasiveness of CC cells. In contrast, overexpression of p38δ MAPK in these cells results in enhanced invasive behaviour. Significantly, p38δ MAPK may prove to be a useful marker for the differential diagnosis of CC over hepatocellular carcinoma where it lacks expression [90].

In contrast to the relatively well characterised role of p38δ MAPK as a tumour promoter an increasing number of reports since 2011 outline its activity as a tumour suppressor. The first indication of a tumour suppressive role for p38δ MAPK was observed in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEF). p38δ −/− (and p38γ −/−) MEFs displayed increased cell motility compared to WT cells [98]. Furthermore, while WT fibroblasts ceased to proliferate after reaching 100% confluency, p38δ −/− MEFs continued to grow, forming foci rather than a monolayer [98]. This deregulation of contact inhibition is significant as it is a hallmark of malignant transformation [99]. Our own recent studies have also identified a role for p38δ MAPK in the control of oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma (OESCC) migration, invasion and contact inhibition, processes which are crucial for the progression of primary tumours to distant metastases [100]. Reintroduction of p38δ MAPK into OESCC cells which lack endogenous expression significantly impaired cell proliferation, migration, and invasion as well as significantly reducing the number of colonies formed on soft agar compared to WT. These effects were further enhanced in cells transfected with a constitutively active form of p38δ MAPK [100]. Furthermore, p38δ MAPK expression appears to influence the chemosensitivity of OESCC to apoptosis. Our recent study indicates that OESCC cells expressing p38δ MAPK are significantly more sensitive to cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil combination therapy than p38δ MAPK-deficient cells [101]. These findings are significant as they suggest that p38δ MAPK may be a useful predictor of response to chemotherapy in OESCC patients. Further supporting the hypothesis that loss of p38δ MAPK confers a survival advantage, p38δ MAPK expression was found to be downregulated in brain metastases of triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Abolition of p38δ MAPK expression in TNBC induced cell growth, while overexpression of p38δ MAPK in brain metastases reduced growth rates [102].

Cancer genomes are increasingly associated with epigenetic alterations whereby tumour suppressor genes exhibit promoter hypermethylation. Interestingly, hypermethylation of the MAPK13 gene promoter region has recently been characterised in both malignant pleural mesothelioma [103] and primary cutaneous melanoma [104]. This methylation is associated with downregulation of p38δ MAPK mRNA and protein expression. Melanoma cell lines displaying MAPK13 gene promoter methylation do not express significant levels of p38δ MAPK when compared to fibroblasts, melanocytes, and melanoma cell lines with unmethylated MAPK13 promoters. Furthermore, treatment of melanoma cells with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine significantly increases the expression of the MAPK13 gene [104, 105]. Importantly, reestablishment of p38δ MAPK expression in melanoma cells with MAPK13 hypermethylation suppresses cell proliferation. The effect was further enhanced upon expression of a constitutively active form of p38δ MAPK. Interestingly, however, overexpression of p38δ MAPK or its constitutively active form in cells in which MAPK13 was not epigenetically silenced only marginally affected proliferation [104].

6. Conclusions and Future Directions for p38δ MAPK Research

p38δ MAPK is a unique stress-responsive protein kinase. It is mainly activated by environmental stresses, including UV radiation, osmotic shock, and oxidative stress, to illicit an adaptive response within the cell. This is mediated through phosphorylation of substrates involved in cytoskeleton organisation such as tau and stathmin, as well as transcription factors responsible for the expression of stress-responsive genes [106, 107]. Since the discovery of the p38 MAPK family in the mid-nineties they have increasingly been associated with cellular processes such as proliferation, differentiation, development, apoptosis, and migration [108]. Research to date has generally focused on the first two isoforms to be discovered. It is now becoming increasingly clear however that conclusions drawn from p38α MAPK (and to an extent p38β MAPK) studies cannot be automatically applied to the p38γ and p38δ MAPK isoforms due to their different expression patterns, substrate specificities, and sensitivity to chemical inhibitors. Studies carried out in the last few years have led to some small advances in our knowledge of the regulation of p38δ MAPK and its physiological roles. In particular, the development of p38δ MAPK KO mouse models has yielded a greater understanding of the consequences of p38δ MAPK signalling in vivo. Roles for p38δ MAPK in important cellular processes such as differentiation and apoptosis have been identified [69, 72]. As a result, p38δ MAPK is now implicated in a variety of pathological conditions including inflammatory diseases, diabetes, and cancer [72, 75, 92, 98]. Most importantly, p38δ MAPK may now be considered as a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of these disorders.

The implication of p38δ MAPK in a wide range of human diseases should strengthen future research interest in this isoform. The main limiting factors to the further study of p38δ MAPK functions, however, are the lack of specific inhibitors and activators. Fuelled by the prospect of therapeutic benefit for patients with diabetes or inflammatory disease, for example, the search for more potent and specific inhibitors of p38δ MAPK is ongoing [83]. These may not only provide potential treatments for the conditions outlined here but could also afford us the opportunity to delineate specific p38δ MAPK functions in the absence of involvement from other p38 MAPK isoforms. This in turn may identify other diseases where p38δ MAPK could be a potential therapeutic target. In this review we also present important and interesting observations which suggest that focusing on identification of specific p38δ MAPK activators is also warranted. This may in the future translate to the development of novel therapeutic strategies for patients with OESCC or melanoma. Whether considering the possible therapeutic benefits of p38δ MAPK inhibitors or activators it is important to heed the diversity and important role(s) of p38δ MAPK signalling in normal physiological processes. In conclusion, uncovering some of the physiological as well as pathological roles of p38δ MAPK since its discovery almost twenty years ago has been somewhat successful. However, based on our current knowledge continued focused research on this particular isoform is necessary if p38δ is to translate into a novel therapeutic target for a range of diverse human diseases.

Abbreviations

- UV:

Ultraviolet

- GPCR:

G-protein coupled receptor

- GTP:

Guanine tyrosine phosphatase

- STE20:

Sterile 20

- ASK1:

Apoptosis signal-regulating kinase 1

- TAK1:

Transforming growth factor β activated kinase 1

- MLK:

Mixed-lineage kinase

- TAO:

Thousand-and-one amino acid

- MEKK:

Mitogen activated protein kinase kinase kinase

- MKK:

Mitogen activated protein kinase kinase

- PRKD1:

Protein kinase D 1

- AP1:

Activator protein 1

- ATF2:

Activating transcription factor 2

- C/EBP:

CCAAT (cytosine-cytosine-adenosine-adenosine-thymidine)-enhancer-binding protein

- myb:

Myeloblastosis

- SAP:

Serum response factor accessory protein

- eEF2K:

Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 kinase

- eEF2:

Eukaryotic elongation factor 2

- PHAS-1:

Phosphorylated heat- and acid-stable protein 1

- eIF4E:

Eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4E.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- 1.Han J, Lee J-D, Bibbs L, Ulevitch RJ. A MAP kinase targeted by endotoxin and hyperosmolarity in mammalian cells. Science. 1994;265(5173):808–811. doi: 10.1126/science.7914033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee JC, Laydon JT, McDonnell PC, et al. A protein kinase involved in the regulation of inflammatory cytokine biosynthesis. Nature. 1994;372(6508):739–746. doi: 10.1038/372739a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rouse J, Cohen P, Trigon S, et al. A novel kinase cascade triggered by stress and heat shock that stimulates MAPKAP kinase-2 and phosphorylation of the small heat shock proteins. Cell. 1994;78(6):1027–1037. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90277-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Freshney NW, Rawlinson L, Guesdon F, et al. Interleukin-1 activates a novel protein kinase cascade that results in the phosphorylation of Hsp27. Cell. 1994;78(6):1039–1049. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90278-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Y, Chen C, Li Z, et al. Characterization of the structure and function of a new mitogen-activated protein kinase (p38β) The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1996;271(30):17920–17926. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.30.17920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li Z, Jiang Y, Ulevitch RJ, Han J. The primary structure of p38γ: a new member of p38 group of MAP kinases. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1996;228(2):334–340. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jiang Y, Gram H, Zhao M, et al. Characterization of the structure and function of the fourth member of p38 group mitogen-activated protein kinases, p38δ . The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(48):30122–30128. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.48.30122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang XS, Diener K, Manthey CL, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(38):23668–23674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goedert M, Cuenda A, Craxton M, Jakes R, Cohen P. Activation of the novel stress-activated protein kinase SAPK4 by cytokines and cellular stresses is mediated by SKK3 (MKK6); comparison of its substrate specificity with that of other SAP kinases. The EMBO Journal. 1997;16(12):3563–3571. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.12.3563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brewster JL, de Valoir T, Dwyer ND, Winter E, Gustin MC. An osmosensing signal transduction pathway in yeast. Science. 1993;259(5102):1760–1763. doi: 10.1126/science.7681220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li M, Liu J, Zhang C. Evolutionary history of the vertebrate mitogen activated protein kinases family. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026999.e26999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cuenda A, Rouse J, Doza YN, et al. SE 203580 is a specific inhibitor of a MAP kinase homologue which is stimulated by cellular stresses and interleukin-1. FEBS Letters. 1995;364(2):229–233. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00357-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong L, Pav S, White DM, et al. A highly specific inhibitor of human p38 MAP kinase binds in the ATP pocket. Nature Structural Biology. 1997;4(4):311–316. doi: 10.1038/nsb0497-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eyers PA, Craxton M, Morrice N, Cohen P, Goedert M. Conversion of SB 203580-insensitive MAP kinase family members to drug-sensitive forms by a single amino-acid substitution. Chemistry and Biology. 1998;5(6):321–328. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(98)90170-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gum RJ, McLaughlin MM, Kumar S, et al. Acquisition of sensitivity of stress-activated protein kinases to the p38 inhibitor, SB 203580, by alteration of one or more amino acids within the ATP binding pocket. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1998;273(25):15605–15610. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.25.15605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuma Y, Sabio G, Bain J, Shpiro N, Márquez R, Cuenda A. BIRB796 inhibits all p38 MAPK isoforms in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2005;280(20):19472–19479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414221200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coulthard LR, White DE, Jones DL, McDermott MF, Burchill SA. p38MAPK: stress responses from molecular mechanisms to therapeutics. Trends in Molecular Medicine. 2009;15(8):369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hu MC-T, Wang Y-p, Mikhail A. Murine p38-δ mitogen-activated protein kinase, a developmentally regulated protein kinase that is activated by stress and proinflammatory cytokines. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1999;274(11):7095–7102. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.11.7095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sabio G, Arthur JSC, Kuma Y, et al. p38γ regulates the localisation of SAP97 in the cytoskeleton by modulating its interaction with GKAP. EMBO Journal. 2005;24(6):1134–1145. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Beardmore VA, Hinton HJ, Eftychi C, et al. Generation and characterization of p38β (MAPK11) gene-targeted mice. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2005;25(23):10454–10464. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10454-10464.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allen M, Svensson L, Roach M, Hambor J, McNeish J, Gabel CA. Deficiency of the stress kinase p38α results in embryonic lethality: Characterization of the kinase dependence of stress responses of enzyme-deficient embryonic stem cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2000;191(5):859–870. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raingeaud J, Gupta S, Rogers JS, et al. Pro-inflammatory cytokines and environmental stress cause p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activation by dual phosphorylation on tyrosine and threonine. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(13):7420–7426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.13.7420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation. Physiological Reviews. 2001;81(2):807–869. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheung PCF, Campbell DG, Nebreda AR, Cohen P. Feedback control of the protein kinase TAK1 by SAPK2a/p38α. EMBO Journal. 2003;22(21):5793–5805. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gallo KA, Johnson GL. Mixed-lineage kinase control of JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2002;3(9):663–672. doi: 10.1038/nrm906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ichijo H, Nishida E, Irie K, et al. Induction of apoptosis by ASK1, a mammalian MAPKKK that activates SAPK/JNK and p38 signaling pathways. Science. 1997;275(5296):90–94. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5296.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamaguchi K, Shirakabe K, Shibuya H, et al. Identification of a member of the MAPKKK family as a potential Mediator of TGF-β signal transduction. Science. 1995;270(5244):2008–2011. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5244.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cuevas BD, Abell AN, Johnson GL. Role of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase kinases in signal integration. Oncogene. 2007;26(22):3159–3171. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang S, Han J, Sells MA, et al. Rho family GTPases regulate p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase through the downstream mediator Pak1. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1995;270(41):23934–23936. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.41.23934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marinissen MJ, Chiariello M, Pallante M, Gutkind JS. A network of mitogen-activated protein kinases links G protein-coupled receptors to the c-jun promoter: a role for c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase, p38s, and extracellular signal-regulated kinase 5. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 1999;19(6):4289–4301. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.6.4289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Remy G, Risco AM, Iñesta-Vaquera FA, et al. Differential activation of p38MAPK isoforms by MKK6 and MKK3. Cellular Signalling. 2010;22(4):660–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang L, Ma R, Flavell RA, Choi ME. Requirement of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 (MKK3) for activation of p38α and p38δ MAPK isoforms by TGF-β1 in murine mesangial cells. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(49):47257–47262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208573200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schoorlemmer J, Goldfarb M. Fibroblast growth factor homologous factors and the islet brain-2 scaffold protein regulate activation of a stress-activated protein kinase. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(51):49111–49119. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205520200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawler S, Fleming Y, Goedert M, Cohen P. Synergistic activation of SAPK1/JNK1 by two MAP kinase kinases in vitro. Current Biology. 1998;8(25):1387–1391. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00019-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tournier C, Dong C, Turner TK, Jones SN, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. MKK7 is an essential component of the JNK signal transduction pathway activated by proinflammatory cytokines. Genes and Development. 2001;15(11):1419–1426. doi: 10.1101/gad.888501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wada T, Nakagawa K, Watanabe T, et al. Impaired synergistic activation of stress-activated protein kinase SAPK/JNK in mouse embryonic stem cells lacking SEK1/MKK4: different contribution of SEK2/MKK7 isoforms to the synergistic activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(33):30892–30897. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M011780200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ge B, Gram H, di Padova F, et al. MAPKK-independent activation of p38alpha mediated by TAB1-dependent autophosphorylation of p38alpha. Science. 2002;295(5558):1291–1294. doi: 10.1126/science.1067289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salvador JM, Mittelstadt PR, Guszczynski T, et al. Alternative p38 activation pathway mediated by T cell receptor-proximal tyrosine kinases. Nature Immunology. 2005;6(4):390–395. doi: 10.1038/ni1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Avitzour M, Diskin R, Raboy B, Askari N, Engelberg D, Livnah O. Intrinsically active variants of all human p38 isoforms. FEBS Journal. 2007;274(4):963–975. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Askari N, Diskin R, Avitzour M, Capone R, Livnah O, Engelberg D. Hyperactive variants of p38α induce, whereas hyperactive variants of p38γ suppress, activating protein 1-mediated transcription. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2007;282(1):91–99. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608012200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou X, Ferraris JD, Dmitrieva NI, Liu Y, Burg MB. MKP-1 inhibits high NaCl-induced activation of p38 but does not inhibit the activation of TonEBP/OREBP: opposite roles of p38α and p38δ . Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105(14):5620–5625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801453105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tanoue T, Yamamoto T, Maeda R, Nishida E. A Novel MAPK phosphatase MKP-7 acts preferentially on JNK/SAPK and p38 alpha and beta MAPKs. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(28):26629–26639. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kraft CA, Efimova T, Eckert RL. Activation of PKCδ and p38δ MAPK during okadaic acid dependent keratinocyte apoptosis. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2007;299(2):71–83. doi: 10.1007/s00403-006-0727-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuenda A, Rousseau S. p38 MAP-Kinases pathway regulation, function and role in human diseases. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta—Molecular Cell Research. 2007;1773(8):1358–1375. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kumar S, McDonnell PC, Gum RJ, Hand AT, Lee JC, Young PR. Novel homologues of CSBP/p38 MAP kinase: activation, substrate specificity and sensitivity to inhibition by pyridinyl imidazoles. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1997;235(3):533–538. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goedert M, Hasegawa M, Jakes R, Lawler S, Cuenda A, Cohen P. Phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein tau by stress-activated protein kinases. FEBS Letters. 1997;409(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00483-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bramblett GT, Goedert M, Jakes R, Merrick SE, Trojanowski JQ, Lee VMY. Abnormal tau phosphorylation at Ser396 in Alzheimer's disease recapitulates development and contributes to reduced microtubule binding. Neuron. 1993;10(6):1089–1099. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90057-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goedert M. The significance of tau and α-synuclein inclusions in neurodegenerative diseases. Current Opinion in Genetics and Development. 2001;11(3):343–351. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lee VM-Y, Goedert M, Trojanowski JQ. Neurodegenerative tauopathies. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2001;24:1121–1159. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Parker CG, Hunt J, Diener K, et al. Identification of stathmin as a novel substrate for p38 delta. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 1998;249(3):791–796. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jourdain L, Curmi P, Sobel A, Pantaloni D, Carlier M-F. Stathmin: a tubulin-sequestering protein which forms a ternary T2S complex with two tubulin molecules. Biochemistry. 1997;36(36):10817–10821. doi: 10.1021/bi971491b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Curmi PA, Andersen SSL, Lachkar S, et al. The stathmin/tubulin interaction in vitro. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 1997;272(40):25029–25036. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knebel A, Morrice N, Cohen P. A novel method to identify protein kinase substrates: eEF2 kinase is phosphorylated and inhibited by SAPK4/p38δ . EMBO Journal. 2001;20(16):4360–4369. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.16.4360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jørgensen R, Merrill AR, Andersen GR. The life and death of translation elongation factor 2. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2006;34(1):1–6. doi: 10.1042/BST20060001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gonzalez-Teran B, Cortes JR, Manieri E, et al. Eukaryotic elongation factor 2 controls TNF-alpha translation in LPS-induced hepatitis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2013;123(1):164–178. doi: 10.1172/JCI65124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Efimova T. p38delta mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates skin homeostasis and tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2010;9(3):498–505. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.3.10541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Eckert RL, Efimova T, Balasubramanian S, Crish JF, Bone F, Dashti S. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinases on the body surface—a function for p38δ . Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2003;120(5):823–828. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2003.12120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Balasubramanian S, Efimova T, Eckert RL. Green tea polyphenol stimulates a Ras, MEKK1, MEK3, and p38 cascade to increase activator protein 1 factor-dependent involucrin gene expression in normal human keratinocytes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(3):1828–1836. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Efimova T, Deucher A, Kuroki T, Ohba M, Eckert RL. Novel protein kinase C isoforms regulate human keratinocyte differentiation by activating a p38δ mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade that targets CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2002;277(35):31753–31760. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dashti SR, Efimova T, Eckert RL. MEK6 regulates human involucrin gene expression via a p38α- and p38δ-dependent mechanism. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(29):27214–27220. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100465200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Efimova T, Broome A-M, Eckert RL. A regulatory role for p38delta MAPK in keratinocyte differentiation: evidence for p38delta-ERK1/2 complex formation. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(36):34277–34285. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jans R, Atanasova G, Jadot M, Poumay Y. Cholesterol depletion upregulates involucrin expression in epidermal keratinocytes through activation of p38. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2004;123(3):564–573. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.23221.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dashti SR, Efimova T, Eckert RL. MEK7-dependent activation of p38 MAP kinase in keratinocytes. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2001;276(11):8059–8063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000862200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Siljamäki E, Raiko L, Toriseva M, et al. p38delta mitogen-activated protein kinase regulates the expression of tight junction protein ZO-1 in differentiating human epidermal keratinocytes. Archives of Dermatological Research. 2014;306(2):131–141. doi: 10.1007/s00403-013-1391-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Haider AS, Peters SB, Kaporis H, et al. Genomic analysis defines a cancer-specific gene expression signature for human squamous cell carcinoma and distinguishes malignant hyperproliferation from benign hyperplasia. Journal of Investigative Dermatology. 2006;126(4):869–881. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johansen C, Kragballe K, Westergaard M, Henningsen J, Kristiansen K, Iversen L. The mitogen-activated protein kinases p38 and ERK1/2 are increased in lesional psoriatic skin. British Journal of Dermatology. 2005;152(1):37–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Uddin S, Ah-Kang J, Ulaszek J, Mahmud D, Wickrema A. Differentiation stage-specific activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms in primary human erythroid cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2004;101(1):147–152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307075101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hale KK, Trollinger D, Rihanek M, Manthey CL. Differential expression and activation of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase α, β, γ, and δ in inflammatory cell lineages. The Journal of Immunology. 1999;162(7):4246–4252. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang Z, Shively JE. Acceleration of bone repair in NOD/SCID mice by human Monoosteophils, novel LL-37-activated monocytes. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067649.e67649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Gandarillas A. Epidermal differentiation, apoptosis, and senescence: common pathways? Experimental Gerontology. 2000;35(1):53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0531-5565(99)00088-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Efimova T, Broome A-M, Eckert RL. Protein kinase Cdelta regulates keratinocyte death and survival by regulating activity and subcellular localization of a p38delta-extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 complex. Molecular and Cellular Biology. 2004;24(18):8167–8183. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.18.8167-8183.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Sumara G, Formentini I, Collins S, et al. Regulation of PKD by the MAPK p38delta in insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. Cell. 2009;136(2):235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Price SA, Agthong S, Middlemas AB, Tomlinson DR. Mitogen-activated protein kinase p38 mediates reduced nerve conduction in experimental diabetic neuropathy: interactions with aldose reductase. Diabetes. 2004;53(7):1851–1856. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Komers R, Lindsley JN, Oyama TT, Cohen DM, Anderson S. Renal p38 MAP kinase activity in experimental diabetes. Laboratory Investigation. 2007;87(6):548–558. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ittner A, Block H, Reichel CA, et al. Regulation of PTEN activity by p38delta-PKD1 signaling in neutrophils confers inflammatory responses in the lung. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 2012;209(12):2229–2246. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ware LB, Matthay MA. The acute respiratory distress syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000;342(18):1334–1349. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Brennan FM, McInnes IB. Evidence that cytokines play a role in rheumatoid arthritis. The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2008;118(11):3537–3545. doi: 10.1172/JCI36389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Korb A, Tohidast-Akrad M, Cetin E, Axmann R, Smolen J, Schett G. Differential tissue expression and activation of p38 MAPK α, β, γ, and δ isoforms in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2006;54(9):2745–2756. doi: 10.1002/art.22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Criado G, Risco A, Alsina-Beauchamp D, Pérez-Lorenzo MJ, Escõs A, Cuenda A. Alternative p38 MAPKs are essential for collagen-induced arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatology. 2014;66(5):1208–1217. doi: 10.1002/art.38327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kuyper LM, Paré PD, Hogg JC, et al. Characterization of airway plugging in fatal asthma. American Journal of Medicine. 2003;115(1):6–11. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kim EY, Battaile JT, Patel AC, et al. Persistent activation of an innate immune response translates respiratory viral infection into chronic lung disease. Nature Medicine. 2008;14(6):633–640. doi: 10.1038/nm1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wills-Karp M, Luyimbazi J, Xu X, et al. Interleukin-13: central mediator of allergic asthma. Science. 1998;282(5397):2258–2261. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Alevy YG, Patel AC, Romero AG, et al. IL-13-induced airway mucus production is attenuated by MAPK13 inhibition. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2012;122(12):4555–4568. doi: 10.1172/JCI64896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.del Barco Barrantes I, Nebreda AR. Roles of p38 MAPKs in invasion and metastasis. Biochemical Society Transactions. 2012;40(1):79–84. doi: 10.1042/BST20110676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Junttila MR, Ala-Aho R, Jokilehto T, et al. p38α and p38δ mitogen-activated protein kinase isoforms regulate invasion and growth of head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. Oncogene. 2007;26(36):5267–5279. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Rousseau S, Dolado I, Beardmore V, et al. CXCL12 and C5a trigger cell migration via a PAK1/2-p38alpha MAPK-MAPKAP-K2-HSP27 pathway. Cellular Signalling. 2006;18(11):1897–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bulavin DV, Fornace AJ., Jr. p38 MAP kinase's emerging role as a tumor suppressor. Advances in Cancer Research. 2004;92:95–118. doi: 10.1016/S0065-230X(04)92005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ventura JJ, Tenbaum S, Perdiguero E, et al. p38α MAP kinase is essential in lung stem and progenitor cell proliferation and differentiation. Nature Genetics. 2007;39(6):750–758. doi: 10.1038/ng2037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hui L, Bakiri L, Stepniak E, Wagner EF. p38α: a suppressor of cell proliferation and tumorigenesis. Cell Cycle. 2007;6(20):2429–2433. doi: 10.4161/cc.6.20.4774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Tan FL-S, Ooi A, Huang D, et al. p38delta/MAPK13 as a diagnostic marker for cholangiocarcinoma and its involvement in cell motility and invasion. International Journal of Cancer. 2010;126(10):2353–2361. doi: 10.1002/ijc.24944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Egeblad M, Werb Z. New functions for the matrix metalloproteinases in cancer progression. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2002;2(3):161–174. doi: 10.1038/nrc745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Schindler EM, Hindes A, Gribben EL, et al. p38delta Mitogen-activated protein kinase is essential for skin tumor development in mice. Cancer Research. 2009;69(11):4648–4655. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Bourcier C, Jacquel A, Hess J, et al. p44 mitogen-activated protein kinase (extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1)-dependent signaling contributes to epithelial skin carcinogenesis. Cancer Research. 2006;66(5):2700–2707. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Young MR, Li JJ, Rincón M. Transgenic mice demonstrate AP-1 (activator protein-1) transactivation is required for tumor promotion. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1999;96(17):9827–9832. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.17.9827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Dae JK, Chan KS, Sano S, DiGiovanni J. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Stat3) in epithelial carcinogenesis. Molecular Carcinogenesis. 2007;46(8):725–731. doi: 10.1002/mc.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Chan KS, Sano S, Kataoka K, et al. Forced expression of a constitutively active form of Stat3 in mouse epidermis enhances malignant progression of skin tumors induced by two-stage carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 2008;27(8):1087–1094. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Chan KS, Sano S, Kiguchi K, et al. Disruption of Stat3 reveals a critical role in both the initiation and the promotion stages of epithelial carcinogenesis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;114(5):720–728. doi: 10.1172/JCI21032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cerezo-guisado MI, del Reino P, Remy G, et al. Evidence of p38γ and p38δ involvement in cell transformation processes. Carcinogenesis. 2011;32(7):1093–1099. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgr079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.O'Callaghan C, Fanning LJ, Houston A, Barry OP. Loss of p38δ expression promotes oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma proliferation, migration and anchorage-independent growth. International Journal of Oncology. 2013;43(2):405–415. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.O'Callaghan C, Fanning LJ, Barry OP. p38delta MAPK phenotype: an indicator of chemotherapeutic response in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anti-Cancer Drugs. 2014 doi: 10.1097/CAD.0000000000000156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Choi YK, Woo S-M, Cho S-G, et al. Brain-metastatic triple-negative breast cancer cells regain growth ability by altering gene expression patterns. Cancer Genomics and Proteomics. 2013;10(6):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goto Y, Shinjo K, Kondo Y, et al. Epigenetic profiles distinguish malignant pleural mesothelioma from lung adenocarcinoma. Cancer Research. 2009;69(23):9073–9082. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Gao L, Smit MA, van den Oord JJ, et al. Genome-wide promoter methylation analysis identifies epigenetic silencing of MAPK13 in primary cutaneous melanoma. Pigment Cell and Melanoma Research. 2013;26(4):542–554. doi: 10.1111/pcmr.12096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Koga Y, Pelizzola M, Cheng E, et al. Genome-wide screen of promoter methylation identifies novel markers in melanoma. Genome Research. 2009;19(8):1462–1470. doi: 10.1101/gr.091447.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Risco A, Cuenda A. New insights into the p38gamma and p38delta MAPK pathways. Journal of Signal Transduction. 2012;2012:8 pages. doi: 10.1155/2012/520289.520289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Cuadrado A, Nebreda AR. Mechanisms and functions of p38 MAPK signalling. Biochemical Journal. 2010;429(3):403–417. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Kyriakis JM, Avruch J. Mammalian MAPK signal transduction pathways activated by stress and inflammation: a 10-year update. Physiological Reviews. 2012;92(2):689–737. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Pani E, Ferrari S. p38MAPKδ controls c-Myb degradation in response to stress. Blood Cells, Molecules, and Diseases. 2008;40(3):388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2007.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Hawkes WC, Alkan Z. Delayed cell cycle progression in selenoprotein w-depleted cells is regulated by a mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 4-p38/c-Jun NH 2-terminal kinase-p53 pathway. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2012;287(33):27371–27379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.346593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]