Abstract

Deep-sea fishes provide a unique opportunity to study the physiology and evolutionary adaptation to extreme environments. We carried out a high throughput sequencing analysis on a 454 GS-FLX titanium plate using unnormalized cDNA libraries from six tissues of A. carbo. Assemblage and annotations were performed by Newbler and InterPro/Pfam analyses, respectively. The assembly of 544,491 high quality reads provided 8,319 contigs, 55.6% of which retrieved blast hits against the NCBI nonredundant database or were annotated with ESTscan. Comparison of functional genes at both the protein sequences and protein stability levels, associated with adaptations to depth, revealed similarities between A. carbo and other bathypelagic fishes. A selection of putative genes was standardized to evaluate the correlation between number of contigs and their normalized expression, as determined by qPCR amplification. The screening of the libraries contributed to the identification of new EST simple-sequence repeats (SSRs) and to the design of primer pairs suitable for population genetic studies as well as for tagging and mapping of genes. The characterization of the deep-sea fish A. carbo first transcriptome is expected to provide abundant resources for genetic, evolutionary, and ecological studies of this species and the basis for further investigation of depth-related adaptation processes in fishes.

1. Introduction

The deep-sea (>1000 m depth) covers about 70% of the Earth's surface, representing one of the last large unexplored areas on the planet. Only within the last few decades the technology has advanced sufficiently to reach the deep-sea effectively, revealing unexpected high levels of biodiversity and extremely diverse habitats (canyons, cold seeps, hydrothermal vents, deep-water coral reefs, mud volcanoes, seamounts, and trenches) of significant conservation interest and potential high economic values. Deep-sea environments are characterized by extremely high hydrostatic pressures (1 MPa every 100 m), lack of light, and low temperatures (down to 1-2°C). Therefore, fish as well as any other organism living in the deep-sea had to adapt to tolerate conditions of this extreme habitat [1].

First studies on adaptation to high pressure and low temperatures are dated back in the ‘70s and they report comparison of common proteins present in shallow and deep-water fishes [2, 3]. Key enzymes in muscle tissues that exhibit adaptive differences among species at different depths are the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and malate dehydrogenase (MDH) presenting differences in structural stability (reviews in [4–6]). More recent studies on evolutionary adaptation of functional genes to high pressure report unique amino acid substitutions in α-skeletal actin and myosin heavy chain (MyHC) proteins in deep-sea fishes [7–10]. For deep-sea species inhabiting hydrothermal vents and cold seeps, environments characterized by high pressure, chronic hypoxia, and high concentrations of toxic compounds, molecular and functional adaptation of hemoglobins (Hbs) are reviewed in Hourdez and Weber [11]. Despite these studies, our knowledge on wide scale gene expression patterns in deep-sea fish remains elusive.

The black scabbardfish, Aphanopus carbo (Lowe 1839), is a bathypelagic species belonging to the Trichiuridae family and is distributed in temperate-cold Atlantic waters at depths between 200 and 1800 m [12, 13]. A. carbo represents a commercially valuable species for several regions of the Iberic peninsula, especially in Madeira where catches have reached up to 1000 tons per year [14] amounting to ca. 55% of the total landings. Recently this species has become increasingly targeted by Portuguese, French, and Irish fishing fleets ([15] and literature therein) and fishery data have shown a constant decline in population [16]. The information available on the biology, maturity, spawning, and growth of this species [17, 18] is scattered. Recent studies are reporting a panmictic distribution of this species in the NE Atlantic with multiple breeding sites at low latitudes [19]. It is also worth mentioning that, in southern locations, this species lives in sympatry with A. intermedius, a close related species with very similar morphology [20], therefore attracting interest for evolutionary studies.

High-throughput sequencing approaches applied to transcriptomics now provide a global perspective on taxonomic and functional profiling of genes expectedly expressed under the influence of environmental conditions in which these organisms live. Also known as next-generation sequencing, these techniques allow for a massive characterization of expressed sequence tags (ESTs) providing an overview of those genes expressed in a given tissue at any given time [21]. In silico analyses of massive gene libraries may serve several interests among others. For instances, from discovery and identification of new genes, characterization of gene expression, to development of novel genetic markers for quantitative trait locus (QTL), and population of genomic analyses. The breadth of next-generation sequencing applications extends over a variety of biological questions including those addressing pertinent questions regarding a species' ecology, life history, and evolution [22, 23].

Previous studies regarding transcriptome sequencing and gene expression studies in deep-water species were mostly limited to hydrothermal vents invertebrates [24], microbial communities in hydrothermal plumes [25], deep-sediments [26], and in the water column [27] leaving vertebrates species virtually under-represented. The present work represents a pioneer study for deep-sea fishes providing new insights into the role of differential gene expression on the environmental adaptation of deep-sea black scabbardfish.

Here we describe the assembly and annotation of the transcriptome of A. carbo obtained by sequencing mRNA libraries of six tissues (spleen, brain, heart, gonads, liver, and muscle) and explore functional genes whose sequence might be associated to depth adaptation. Additionally, we tested the correlation of selected candidate genes comparing the number of contigs against the gene expression normalized to a relative value of 1.0, as determined by qPCR amplification. Furthermore, the screening of the libraries allowed the identification of new EST-simple-sequence repeats (SSRs) and the design of primer pairs suitable for population genetic studies as well as tagging and mapping of genes.

2. Methods

2.1. Fish and Tissue Samples

Specimens of Aphanopus carbo (two males and two females) were collected in 2009 onboard of the RV “Arquipelago.” A. carbo were fished at depth range 1100–1250 m using deep-water long-lines in proximity of the Condor Seamount, located approximately at 15 nm SW of the island of Fayal (Azores, Portugal). The four specimens used in this study were caught on the same longline set and once onboard, the freshly caught animals were dissected and portions (or complete organs) of spleen, brain, heart, gonads, liver, and muscle tissues were preserved in formamide solution and kept at −20°C until RNA extraction was performed.

To validate the correct identification of the species, a small portion of muscle tissue was also preserved in 95% ethanol for molecular screening following Stefanni et al. [28] protocols.

2.2. RNA Extraction and Sequencing

Total RNA was extracted from 20 to 40 mg of each of the six preserved tissues of a pool of four A. carbo individualsusing the RiboPure kit (Ambion, Applied Biosystems). Quantity and purity of the RNA was determined on a 1.4% agarose-MOPS-formaldehyde denaturing gels and by assessing the A 260/280 and A 260/230 ratios using the NanoVue spectrophotometer (GE Healthcare). Poly-A RNA was extracted from 15 μg of each total RNA sample using the Poly(A)Purist mRNA Purification kit according to manufacturer's instructions (Ambion, Applied Biosystems). mRNAs were transcribed into cDNA utilizing Mint-2 cDNA synthesis kit (Evrogen, http://www.evrogen.com/) according to manufacturer's instructions for NGS platforms. Six cDNA libraries were constructed from mRNA of individual pools of tissues and sequenced in a single 454 GS FLX Titanium run. Each of the cDNA libraries was characterised by unique sequence tags (MIDs) that allowed to trace back the sequences generated from single tissues after assembly.

cDNAs were sheared by nebulization to yield random fragments approximately 500–800 bp in length, by applying 30 psi (2,1 bar) of nitrogen for 1 minute on 4 μg of each library. The distribution of fragments was verified on a BioAnalyser DNA 7500 LabChip (Agilent Technologies). The fragmented cDNA sample was end-repaired with T4 DNA polymerase and T4 polynucleotide kinase and adaptor sequences ligated according to the manufacturer's instructions [29]. The fragments were immobilized onto streptavidin beads and nick-repaired with Bst polymerase. The cDNA fragments were denaturated with alkali to yield single stranded cDNA (sscDNA) library. Quality of the library was assayed on a BioAnalyser RNA 6000 Pico LabChip (Agilent Technologies) and quantity measured by spectrofluorimetry with the Quant-iT RiboGreen RNA Assay kit (Invitrogen). A titration was set up at 1, 2, 4, and 8 copies per bead (cpb) in the clonal amplification by emulsion PCR to optimize yield and sequence quality. The percent enrichment of beads carrying the sscDNA was determined and the amount of library input calculated to 18%. A large scale emulsion PCR was set-up based on the previous value and sequenced at Biocant (Cantanhede, Portugal) using the 454 GS FLX Titanium pyrosequencing on a full 70X75 PicoTiterPlate, according to manufacturer's instructions (Roche).

2.3. Bioinformatic Analyses

High quality reads were assembled using Newbler ver. 2.6 (Roche 454) sequence analysis software. All reads were identified and grouped by their unique MIDs to the tissue of origin. Trimming and masking the polyAs was a common procedure for the assembling tool.

The assemblage is characterized by read overlaps and multiple alignments made in nucleotide space. Consensus base-calling and quality value determination for contigs are performed in flow space. The use of flow space in determining the properties of the consensus sequence results in an improved accuracy for the final base-calls. The implementation of this software was performed using default parameters. Assembled contigs were annotated through sequence similarity searches against the National Centre for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) nonredundant (nr) protein database using the BLASTx [30] with a cut-off criterion of an expect-value (e-value) < 10−6. The contigs that did not find a hit were further processed with ESTScan (http://www.ch.embnet.org/software/ESTScan2.html). The two assemblages of amino acid sequences, resulting from the BLASTx searches at high level of stringency and the ESTScan, were processed by InterProScan for functional annotation of transcripts applying the function for the mapping of gene ontology (GO) terms. The GO method classifies genes within a hierarchy using a systematic nomenclature of attributes that can be assigned to all gene products independently from the organism of origin. To reduce the redundancy in the consensus sequences which correspond to the same gene we used BLASTClust to detect similar assemblies with 95% identity and 90% coverage. All the results from both assemblage methods were loaded into a SQL database developed for this purpose.

To validate the accuracy of the assembly, the resulting contigs were compared to previously sequenced transcriptomes of 6 teleosts including Danio rerio, Gasterosteus aculeatus, Oreochromis niloticus, Oryzias latipes, Takifugu rubripes, and Tetraodon nigroviridis, using tBLASTn [30] to find protein homologs at two levels of stringency (e-value < 10−3 and e-value < 10−10).

To identify protein conserved domain specific for each tissue analysed a new annotation was performed with Hmmer against the Pfam database (ver. 25.0). Protein domain representativeness for each tissue was obtained comparing protein domain abundance in a particular tissue versus all the tissues compiled together using a hypergeometric test.

2.4. cDNA Synthesis and qPCR Validation Tests

Fresh cDNA was synthesised from the six mRNAs that were used for pyrosequencing, cDNA synthesis was performed using primers with oligo(dT) and the ThermoScript RT-PCR System (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer's instructions.

A set of 28 genes were selected including candidates that were tissue-specific and genes that were encountered in the tissue expressed at similar as well as at different amounts in all the six libraries, with the aim of covering most of the possible expression scenarios within the dataset. Frequencies of contigs for all candidates genes in the mRNA libraries were obtained by detecting orthologous gene sequences using the BLAST tool included in the A. carbo database.

For the design of all qPCR primers (Table 1) we used the web interface NCBI Primer-BLAST (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Alignments of the sequences provided by the output from the internal blast search were used to select all primer sets.

Table 1.

List of targeted genes using qPCR, primer sets specifically designed for this study, size for each of the product, and NCBI accession number for all the EST sequences.

| Gene | Primer name | Primer Sequences (5′-3′) | Size (bp) | NCBI Accession # |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Elongation factor 1-beta | EF-1B L | GCTTGGACATGTCGGTCTCGTC | 229 bp | All_gs454_000396 |

| EF-1B H | GTGGCTGACACCACATCTGGC | |||

| Ras-related GTP-binding protein A | Rab-1A L | AGTAGCCGTTCCACCTTGTCGG | 247 bp | All_gs454_000598 |

| Rab-1A H | TGCCAAGAAACCGTACGTGGGA | |||

| Basic Transcription Factor 3-like 4 | BTF3 L | CCCAAAGTTCAGGCCTCCCTGT | 273 bp | All_gs454_000873 |

| BTF3 H | TCATGTGCGTCAGTTCGCTTCG | |||

| Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutase | SOD-1 L | AAACGTGACTGCAGGAGGGGAT | 240 bp | All_gs454_000925 |

| SOD-1 H | CAGTGCTCCTGCTCCATGTTCG | |||

| 2-Cys Peroxiredoxin | PRDX1 L | CCGATAACCTCGCAGCCGATAC | 243 bp | All_gs454_000558 |

| PRDX1 H | ACAGTCATTTGCCACCAGCATCA | |||

| Heat Shock Protein 90 | HSP90 L | TGACGATGTCCCCACAGATGAGG | 221 bp | All_gs454_000008 |

| HSP90 H | GCAACACTGGTCCACCACACAAC | |||

| Ferritin, heavy subunit | Ferr L | CCTGCAGCTTGAGAAGAGCGTC | 203 bp | All_gs454_000681 |

| Ferr H | CAAACAGGTACTCGGCCATGCC | |||

| α 2 Globin | Hb-A L | AAATTGTTGGCCATGCGGAGGA | 208 bp | All_gs454_001919 |

| Hb-A H | CTGAGGTTCAGCAGACCTGCCT | |||

| β 2 Globin | Hb-B L | TCGTCTACCCCTGGTGTCAGAG | 245 bp | All_gs454_001018 |

| Hb-B H | AACCACAATGGTCAGGCAGTCC | |||

| Ependymin-1 precursor | EPD-1 L | CAGGTGTGAGGCAGTGCAGT | 230 bp | All_gs454_000469 |

| EPD-1 H | ACCCCGATCTCCTCCTGGTG | |||

| Fatty acid-binding protein, brain | BLBP L | CAACACTTCTTGGCCGGTTTGG | 239 bp | All_gs454_001220 |

| BLBP H | GAGAGGAGTTCGACGAAGCCAC | |||

| CD63-like protein Sm-TSP-2 | TSPAN-8 L | TCGCTGGCTGCTCTGAGAAAGA | 200 bp | All_gs454_000381 |

| TSPAN-8 H | GGTCACGCCGAGCTGTATTCTG | |||

| Tropomyosin 4 isoform 1 | TRPM-1 L | GTGGAGGAGGAGTTGGACCGAG | 221 bp | All_gs454_000222 |

| TRPM1 H | TTGCGAGCCACCTCCTCGTATT | |||

| C-Myc-binding protein | MYCBP L | CGCCAGTTTACCTGCGTTCCAA | 182 bp | All_gs454_001640 |

| MYCBP H | GGCCGTCAACAACACCACCTTT | |||

| Cathepsin S | CTSS L | AACAGCCTACCCCTACACAGCC | 200 bp | All_gs454_000156 |

| CTSS H | TGTACACACCGTGGCGGTAGAA | |||

| Transferrin | STF-1 L | AGCTGCACCAGCTTCACAGTTG | 215 bp | All_gs454_000004 |

| STF-1 H | AAGGATGGCACCAGACAACCCA | |||

| Warm Temperature Acclimation related-like 65 kDa protein | HPX L | TGATACCGGGTGGAACCTGGTG | 207 bp | All_gs454_000060 |

| HPX H | GCTGCTGTGGAGTGTCCCAAAG | |||

| Betaine Homocysteine S-methyltransferase | BHTM L | GGGGGTTCGCTGTTACCAAGTG | 194 bp | All_gs454_000088 |

| BHTM H | TGTGAGACAGCAGCCTCAGGAG | |||

| FUCL1 Fucolectin-1 | FUCL1 L | CGCAAACCCTTTGGCTGGTGTA | 196 bp | All_gs454_000758 |

| FUCL1 H | GGCTTTTCCTTGGACTGCCAGG | |||

| Aldolase B | ALDB L | GCCATTGGTCTTGGCCCTGATC | 220 bp | All_gs454_000115 |

| ALDB H | CGCTGTGCCTGGTATCTGCTTC | |||

| Type-4 ice-structuring protein LS-12 precursor | ISP LS12 L | AAGACCTGACAAACCAGGCCCA | 198 bp | All_gs454_001277 |

| ISP LS12 H | GGAGGATGGCCTCCATCTGCTT | |||

| Alcohol Dehydrogenase 8a | ADH L | GGCAAGAAGGTGCTGCAGTTCA | 228 bp | All_gs454_000105-6 |

| ADH H | CATGACTGCAGCCAAACCCACA | |||

| Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate Dehydrogenase | GAPDH L | GTCAACCACTGACACGTTGGGG | 229 bp | All_gs454_000148 |

| GAPDH H | CGGCATCATTGAGGGCCTGATG | |||

| Lactate Dehydrogenase-A | LDH-A L | TCTTAACCTGGTGCAGCGCAAC | 219 bp | All_gs454_000149 |

| LDH-A H | TGGAGCTTCTCGCCCATGATGT | |||

| Phosphoglycerate Mutase 2-1 (muscle) | PglyM L | ACACCTCTGTGCTGAAACGTGC | 212 bp | All_gs454_000309 |

| PglyM H | CATGGGTGGAGGTGGGATGTCA | |||

| Heat Shock Protein 70 | HSP70 L | CGGTGTTGTGTGCTGGGTGAAA | 207 bp | All_gs454_000005 |

| HSP70 H | CCACATAGCTGGGTGTGGTCCT | |||

| Fructose-bisphosphate Aldolase A | FBPA L | GGAACCAACGGCGAGACAACAA | 208 bp | All_gs454_002732 |

| FBPA H | CAATGGGGACGATGCCATGCAT | |||

| Phosphoglucose Isomerase-2 | PGI L | CCACACTGGGCCAATTGTCTGG | 217 bp | All_gs454_000011 |

| PGI H | GGCCTCCTCTGTGGTCTTACCC |

Gene expression, calculated as relative expression, was determined by means of real-time PCR using the CFX96 (Bio-Rad). Primer concentrations and sample dilutions were optimized to meet highest efficiency in the PCR reaction in a total reaction volume of 20 μL. Fluorescent signal was determined by the addition of SsoFast EvaGreen Supermix (Bio-Rad) which was included in the cocktail accordingly to manufacturer's instructions. Baseline and threshold cycle were always set to automatic in the sequence detection software, CFX Manager (Bio-Rad). All plates contained a “no template control” (NTC) and each sample was tested in duplicate. Cycling conditions for gene amplifications were 95°C for 3 min followed by 35 cycles of 95°C for 10 s, 56°C for 10 s, and 68°C for 15 s. An additional protocol for melting curves analysis included a cycle at 95°C followed by a progressive reading of fluorescence for every cycle from 65°C to 95°C for 5 s at intervals of 0.5°C. Gene expression, normalized to a relative value of 1.0 for all the genes selected and for each tissue, was compared to the contigs frequencies generated by the assembly platform to determine the significance of correlation between qPCRs values and 454 sequencing reads from unnormalized cDNA libraries.

2.5. Characterization of Depth-Related Functional Genes

The predicted amino acid sequences of functional genes of A. carbo possibly related to depth adaptations were compared to those deposited in NCBI database searching for homologies. We aligned and compared translated sequences of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH-A and LDH-B), cytosolic malate dehydrogenase (MDHc), hemoglobins (Hb-A and Hb-B), actin (ACTA1), and myosin heavy chain (MyHC). Protein and nucleotide sequences were aligned using Clustal X [31] while sequence analysis and phylogenetic inferences were performed using CLC Main Workbench (v. 6.8.2, CLC Bio). The neighbor-joining (NJ) algorithm [32] was implemented to construct a phylogenetic tree using HKY substitution model and attributing a gap penalty of 10. The support for internal branches was assessed using the bootstrap [33] with 1000 replicates.

Nucleotide alignments and ML trees built, implementing the most appropriate substitution model under the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), were used in the program “codeml” in PAML 4 [34] to assess selective pressure on those genes for which the complete sequences was available. Positive (or negative) selected sites were defined by the ratio between nonsynonymous versus synonymous substitutions (dN/dS or ω). Two models were tested comparatively: M1 which groups codons in two classes (ω < 1 and ω = 1), clustering sites under negative or neutral selection; and M2 which groups codons in three classes (ω < 1, ω = 1 and ω > 1), adding a cluster for sites under positive selection to the ones defined in M1. Probabilistic measures of how well these models fits the evolutionary relationship of individual genes were calculated from the likelihood values of fitted models and the number of “free parameters” for all genes.

Protein stability was estimated using a virtual quantification software [35] calculating Gibbs free energy in terms of kinetic and thermodynamic quantities taking into account each amino acid contribution for the maintenance of the native structure of the protein. For a protein to maintain its stability there is a need of sufficient hydrophobic residues which will utilize free energy to guide proper folding [35].

2.6. EST-SSR Resources for Population Genetics

Among various molecular markers, simple sequence repeats (SSRs) are highly polymorphic, easier to develop, and very useful for researches such as genetic diversity assessment. Therefore A. carbo database was further used to detect such regions in the transcriptome sequencing data and provide a list of combination of primer sets on flanking regions that could be used for population genetic studies. To identify EST-SSRs, all the contigs were searched using MISA [36] and for primer design we used Primer3 [37]. The algorithm of the SSR finder identifies a good quality repeat when one locus is present with adjacent loci at an up or downstream distance higher than 100 bp and parameters were set to locate a minimum of 20 bp sequence repeats: di-mers (x12), 3-mers (x8), 4-mers (x5), 5-mers (x5), and 6-mers (x5). Primer design was performed setting parameters of a minimum size of 20 bp and melting temperatures of 60°C.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sequences Assemblage and Functional Annotations

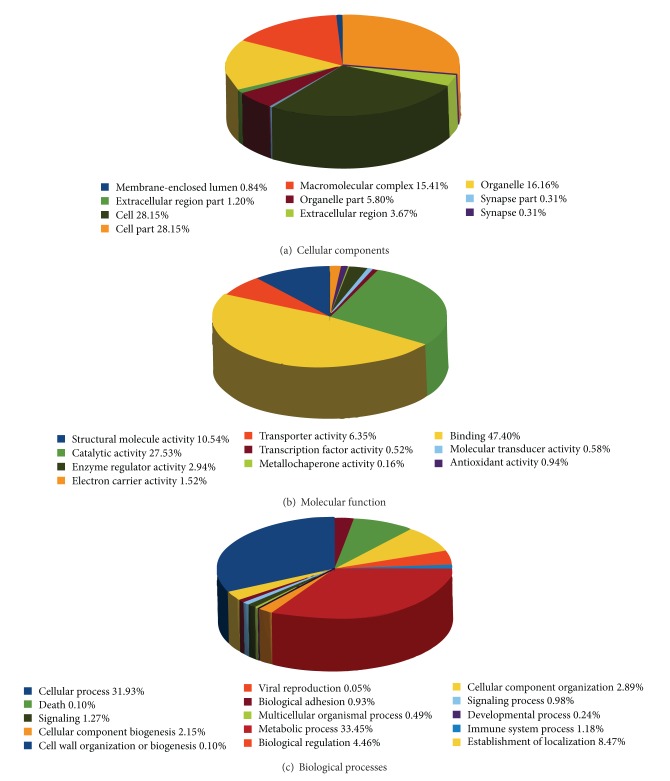

After sequence trimming, a total of 544,491 high quality reads were produced with an average length of 237 bp corresponding to 129.5 Mb. A total of 8,319 contigs were assembled with Newbler (ver 2.6) as high quality consensus sequences without the presence of singletons. A summary of EST data for each of the six tissues is reported in Table 2. A total of 2,440 assembled contigs were annotated against the NCBI nonredundant protein database at the cut-off (e-value) < 10−6. Additional 3,843 contigs with no protein matches were further processed with ESTScan to find 2,715 homologous proteins. All the contigs were then processed by InterProScan for functional annotation of transcripts and mapping functional information to gene ontology (GO) terms. Of the 5,155 amino-acid sequences (out of the 6,283 totally sequenced), 1,728 could be annotated within the GO hierarchy (Figure 1), while 2,395 could be annotated accordingly to InterProScan. The complete GO mapping of A. carbo for individual tissues can be accessed on the dedicated online database (http://transcriptomics.biocant.pt/AphanopusCarbo/). The largest proportions of GO functional categories are of similar proportion to the unnormalized libraries of Tilapia [38]. In the Cellular Components GO group (Figure 1(a)), the genes involved in cell and cell part functional categories corresponded to the largest percentage of the pie chart (28.15% each). In the Molecular Function GO group (Figure 1(b)), almost half of the total genes were involved in binding (47.40%), followed by those related to catalytic activity (27.53%). Finally, for the Biological Processes GO group (Figure 1(c)), the largest portion of the genes were involved in metabolic processes (33.45%), tightly followed by the category of genes linked to the Cellular Process (31.93%).

Table 2.

Global statistics for each of the nonnormalized libraries using Newbler software.

| Tissue | Spleen | Brain | Heart | Gonad | Liver | Muscle | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total EST | 15,034 | 33,337 | 73,263 | 157,275 | 134,523 | 92,788 | 544,491 |

| Total bases | 3,426,510 | 8,219,500 | 17,647,600 | 37,123,700 | 31,792,600 | 23,342,900 | 129,412,000 |

| Contigs | 567 | 651 | 1,260 | 3,875 | 1,274 | 626 | 8,319 |

| Average contig length | 470 | 619 | 567 | 465 | 612 | 689 | 555 |

| Contigs e-value < 10−6 | 220 | 420 | 622 | 951 | 617 | 409 | 2,440 |

| ESTscan | 584 | 345 | 977 | 2,838 | 634 | 269 | 2,715 |

| No similarity | 36 | 70 | 109 | 406 | 211 | 74 | 1,128 |

| GO annotation | 202 | 338 | 473 | 623 | 509 | 307 | 1,728 |

| InterPro annotation | 223 | 417 | 610 | 908 | 649 | 395 | 2,395 |

Figure 1.

Functional categorization of unigenes with gene ontology (GO) term for the Aphanopus carbo EST collection. These unigenes results were functionally classified from the six tissues pooled together as percentages under three main functional categories with respective GO Slim terms. Data refer to assemblage derived by implementation of Newbler, Roche 454 sequence analysis software.

To further validate the accuracy of the A. carbo assembly, we compared our dataset to the transcriptomes of six other prior sequenced teleosts including Danio rerio, Gasterosteus aculeatus, Oreochromis niloticus, Oryzias latipes, Takifugu rubripes, and Tetraodon nigroviridis. Similarity searches were performed comparing our assembled contigs against each of the available transcriptomes using tBLASTn [30]. The results highlighted strong similarity between the transcriptomes of A. carbo and other teleosts indicating that about 30% of the total contigs matched protein homologs (e-values <10−3 ranging between 2,268 and 2,457) and that our assembly presents the highest similarity (by little margin) with the transcriptome of Gasterosteus aculeatus (e-value < 10−10 = 2,223) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Similarity search for unigenes comparing transcriptomes of other teleosts against Aphanopus carbo using two levels of stringency.

| Species | Sequences available |

A. carbo

e-value < 10−3 |

A. carbo

e-value < 10−10 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Danio rerio | 42,787 | 2,457 | 2,199 |

| Gasterosteus aculeatus | 27,576 | 2,445 | 2,223 |

| Oreochromis niloticus | 26,763 | 2,436 | 2,202 |

| Oryzias latipes | 24,674 | 2,412 | 2,173 |

| Takifugu rubripes | 47,841 | 2,268 | 2,062 |

| Tetraodon nigroviridis | 23,118 | 2,300 | 2,073 |

A total of 1639 (20%) transcripts were annotated by Pfam protein domains matches and the set of protein domains characterizing each single tissue was identified by hypergeometric test (Table 4).

Table 4.

List of Pfam conserved domains that were tissue specifically expressed in Aphanopus carbo transcriptome. Frequencies and P-values of tissue specificity analysis are indicated.

(a).

| Gonads | Heart | Liver | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pfam ID | Domain | Freq | P | Pfam ID | Domain | Freq | P | Pfam ID | Domain | Freq | P |

| PF00100 | Zona pellucida | 17 | 3.15 10−13 | PF00011 | HSP20 | 3 | 4.03 10−4 | PF00084 | Sushi | 14 | 1.44 10−10 |

| PF00125 | Histone | 8 | 6.06 10−5 | PF13405 | EF hand 4 | 5 | 6.77 10−4 | PF00089 | Trypsin | 20 | 7.59 10−9 |

| PF01400 | Astacin | 3 | 3.22 10−3 | PF00412 | LIM | 3 | 1.52 10−3 | PF00079 | Serpin | 12 | 5.63 10−6 |

| PF00069 | Pkinase | 3 | 0.01 | PF05556 | Calsarcin | 3 | 3.60 10−3 | PF07678 | A2M comp | 4 | 1.35 10−4 |

| PF00653 | BIR | 2 | 0.02 | PF01576 | Myosin tail 1 | 3 | 3.60 10−3 | PF01042 | Ribonuc L-PSP | 3 | 1.26 10−3 |

| PF13424 | TPR 12 | 2 | 0.02 | PF00056 | Ldh 1 N | 3 | 3.60 10−3 | PF00045 | Hemopexin | 3 | 1.26 10−3 |

| PF13695 | zf-3CxxC | 2 | 0.02 | PF05300 | DUF737 | 2 | 5.50 10−3 | PF00059 | Lectin C | 6 | 1.69 10−3 |

| PF09360 | zf-CDGSH | 2 | 0.02 | PF00992 | Troponin | 4 | 6.40 10−3 | PF00701 | DHDPS | 4 | 4.64 10−3 |

| PF01712 | dNK | 2 | 0.02 | PF00595 | PDZ | 3 | 6.82 10−3 | PF00386 | C1q | 8 | 6.63 10−3 |

| PF00538 | Linker histone | 2 | 0.02 | PF00022 | Actin | 3 | 0.01 | PF00021 | UPAR LY6 | 5 | 0.01 |

| PF10178 | DUF2372 | 2 | 0.02 | PF02874 | ATP-synt ab N | 2 | 0.02 | PF00754 | F5 F8 type C | 9 | 0.01 |

| PF04856 | Securin | 2 | 0.02 | PF13895 | Ig 2 | 3 | 0.02 | PF08702 | Fib alpha | 2 | 0.01 |

| PF00250 | Fork head | 2 | 0.02 | PF00191 | Annexin | 2 | 0.03 | PF03982 | DAGAT | 2 | 0.01 |

| PF01498 | HTH Tnp Tc3 2 | 3 | 0.03 | PF00212 | ANP | 2 | 0.03 | PF01048 | PNP UDP 1 | 2 | 0.01 |

| PF00268 | Ribonuc red sm | 2 | 0.06 | PF05347 | Complex1 LYR | 2 | 0.07 | PF01014 | Uricase | 2 | 0.01 |

(b).

| Muscle | Brain | Spleen | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pfam ID | Domain | Freq | P | Pfam ID | Domain | Freq | P | Pfam ID | Domain | Freq | P |

| PF01410 | Troponin | 7 | 1.99 10−5 | PF01669 | Myelin MBP | 4 | 4.03 10−5 | PF00042 | Globin | 5 | 1.33 10−6 |

| PF02807 | COLFI | 3 | 9.67 10−4 | PF01453 | B lectin | 2 | 6.44 10−3 | PF00078 | RVT 1 | 5 | 1.33 10−6 |

| PF00041 | ATP-gua PtransN | 3 | 3.59 10−3 | PF00612 | IQ | 2 | 6.44 10−3 | PF00993 | MHC II alpha | 4 | 5.02 10−6 |

| PF02453 | fn3 | 3 | 3.59 10−3 | PF11414 | Suppressor APC | 2 | 6.44 10−3 | PF07686 | V set | 5 | 2.49 10−6 |

| PF13895 | Reticulon | 3 | 3.59 10−3 | PF05768 | DUF836 | 2 | 6.44 10−3 | PF07654 | C1 set | 5 | 4.71 10−4 |

| PF00365 | Ig_2 | 4 | 7.97 10−3 | PF05196 | PTN MK N | 2 | 6.44 10−3 | PF00089 | Trypsin | 5 | 2.01 10−3 |

| PF01216 | PFK | 2 | 9.84 10−3 | PF04300 | FBA | 2 | 6.44 10−3 | PF01391 | Collagen | 2 | 2.30 10−3 |

| PF01267 | Calsequestrin | 2 | 9.84 10−3 | PF00287 | Na K-ATPase | 2 | 6.44 10−3 | PF00240 | ubiquitin | 3 | 3.28 10−3 |

| PF00261 | F-actin cap A | 2 | 9.84 10−3 | PF11032 | ApoM | 3 | 8.53 10−3 | PF09307 | MHC2-interact | 2 | 6.67 10−3 |

| PF00856 | Tropomyosin | 2 | 9.84 10−3 | PF00061 | Lipocalin | 4 | 0.01 | PF00643 | Zf-B box | 2 | 0.01 |

| PF01661 | SET | 2 | 9.84 10−3 | PF00007 | Cys knot | 2 | 0.02 | PF13445 | Zf-RING LisH | 2 | 0.01 |

| PF01667 | Macro | 2 | 0.03 | PF01275 | Myelin PLP | 2 | 0.02 | PF01498 | HTH Tnp Tc3 2 | 2 | 0.02 |

| PF00036 | Ribosomal S27e | 2 | 0.05 | PF00300 | His Phos 1 | 2 | 0.02 | PF02301 | HORMA | 1 | 0.05 |

| PF01576 | efhand | 2 | 0.05 | PF00230 | MIP | 2 | 0.02 | PF14259 | RRM 6 | 1 | 0.05 |

| PF01410 | Myosin_tail_1 | 2 | 0.08 | PF00091 | Tubulin | 3 | 0.02 | PF09004 | DUF1891 | 1 | 0.05 |

3.2. qPCR Assays and Validation Tests

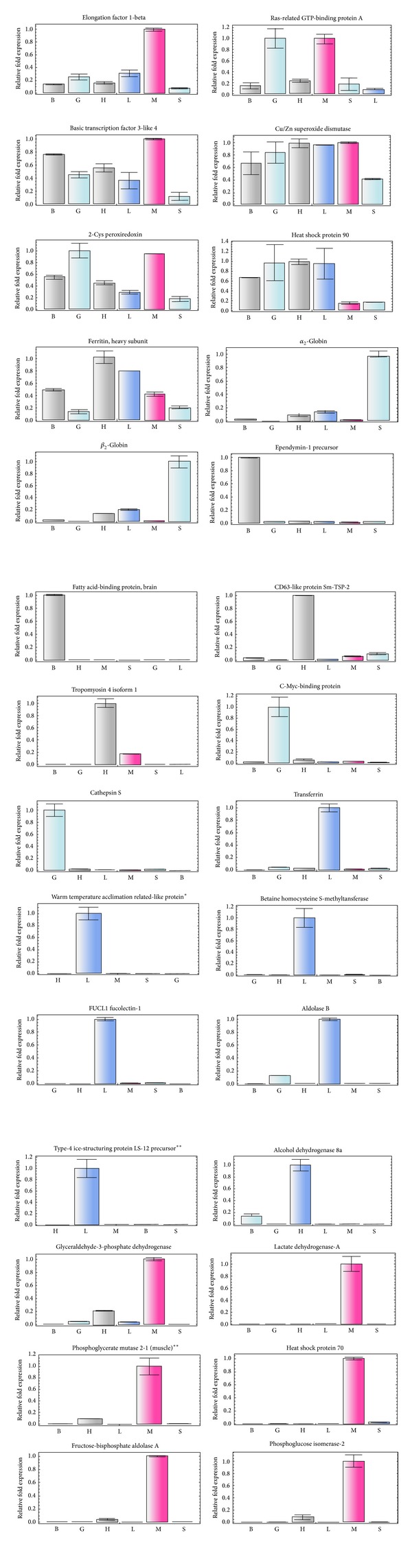

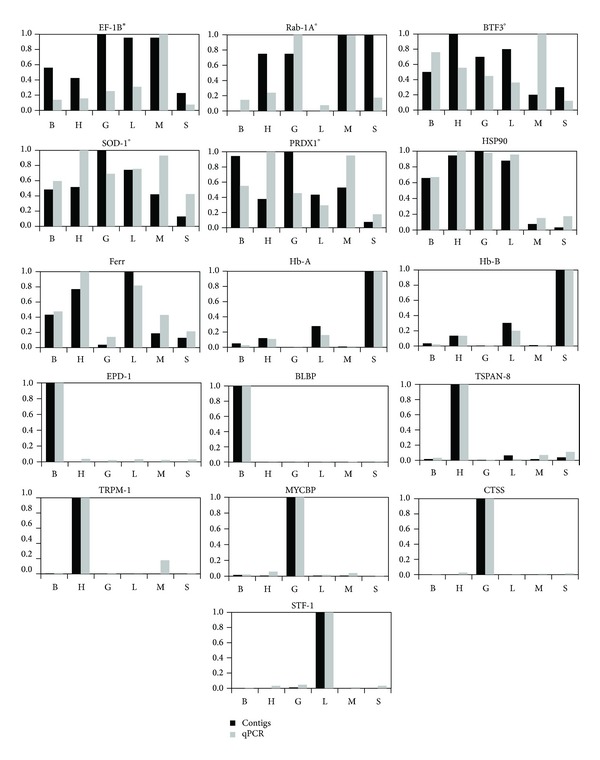

Quantitative PCR assays were performed using cDNA samples at 1 : 400 dilution (up to 100 ng approximately in the qPCR master mix), conditions at which the PCR resulted to be more efficient. We tested seven series of dilutions ranging from 1 : 50 to 1 : 1000. Based on optimized qPCR conditions; all targeted cDNAs were tested across all tissues for the complete set of genes selection used in this study. Normalized expression to a relative value of 1.0 for 28 genes is shown in Figure 2 (see: Figure S1 in Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2014/267482).

Figure 2.

Gene expression normalized to a relative value of 1.0 of all genes selected for this study in different tissues from Aphanopus carbo. S = spleen, B = brain, H = heart, G = gonad, L = liver, M = muscle, *= expression in the brain was below detection and **= expression in the gonads was below detection.

Statistical tests were performed to identify the correlation between the mean value of normalized expression and a relative value of 1.0, as determined by qPCR against contig frequencies using Pearson's r coefficient and its significance (Figure 3). Most of the genes showed highly significant correlation; however one case indicated a reduced significance (elongation factor) and a few other cases resulted to be not significant (e.g., Ras-related GTP-binding protein, Basic Transcription Factor 3, Cu/Zn Superoxide Dismutase and 2-Cys Peroxiredoxin). Reduced or lack of significance appeared to be related to a low number of contigs from the 454 sequencing (Table 5), which might be regarded as an indication of failure to reach library saturation. Low values in contig frequency should correspond to a reduced level of expression as the libraries are nonnormalized; therefore caution should be used when exploring 454 outputs below a certain threshold. Our data derived from the reading of a single plate were insufficient for systematical comparison of all the genes, although the majority of the genes show a high correlation between the 454 data and the qPCR. However, it should be emphasized that this exercise was not meant to be a surrogate to the qPCR approach for the study of gene expression but more a proxy for a preliminary screening of differentially expressed genes in multiple libraries.

Figure 3.

Comparative plots of relative expression as contig frequencies versus mean qPCR values for all genes selected for this study. Codes for each of the gene are listed in Table 1, S = spleen, B = brain, H = heart, G = gonad, L = liver, and M = muscle; the correlation coefficient (Pearson's r) resulted to be highly significant (P < 0.0001) for most of the genes except for *P < 0.05 and °not significant.

Table 5.

Summary table of contig frequency for each of the tissues for those genes used to test the correlation with qPCR assays. S: spleen, B: brain, H: heart, G: gonad, L: liver and M: muscle. Names of genes based on their coding used in this table are found in table.

| Gene | Contig code | Spleen | Brain | Gonads | Heart | Liver | Muscle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EF-1B | isotig00991 | 9 | 24 | 33 | 19 | 38 | 54 |

| Rab-1A | isotig02689 | 4 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| BTF3 | isotig02213 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 2 |

| SOD-1 | isotig02222 | 4 | 16 | 32 | 16 | 25 | 14 |

| PRDX1 | isotig01838 | 4 | 50 | 59 | 17 | 23 | 27 |

| HSP90 | isotig01406 | 3 | 64 | 94 | 86 | 86 | 13 |

| Ferr | isotig01665 | 33 | 121 | 10 | 210 | 264 | 47 |

| Hb-A | isotig06973 | 406 | 17 | 2 | 24 | 108 | 1 |

| Hb-B | isotig00163 | 2,303 | 81 | 16 | 313 | 707 | 22 |

| EPD-1 | isotig01567 | 0 | 1,190 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| BLBP | isotig02632 | 0 | 171 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| TSPAN-8 | isotig01397 | 17 | 7 | 3 | 407 | 24 | 9 |

| TRPM-1 | isotig01595 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 637 | 2 | 2 |

| MYCBP | isotig01988 | 0 | 2 | 135 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| CTSS | isotig01659 | 0 | 0 | 135 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| STF-1 | isotig00767 | 0 | 1 | 30 | 0 | 3,218 | 0 |

| HPX | isotig01479 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,234 | 0 |

| BHTM | isotig01489 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1,024 | 0 |

| FUCL1 | isotig00473 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 0 |

| ALDB | isotig01524 | 0 | 1 | 30 | 0 | 369 | 0 |

| ISP LS12 | isotig03004 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 211 | 1 |

| ADH | isotig01491-546 | 1 | 2 | 16 | 7 | 292 | 6 |

| GAPDH | isotig00609 | 0 | 8 | 51 | 539 | 134 | 1,281 |

| LDH-A | isotig01401 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 5 | 0 | 789 |

| PglyM | isotig01642 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 36 | 0 | 241 |

| HSP70 | isotig01398 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 142 |

| FBPA | isotig00492 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 233 | 0 | 4,471 |

| PGI | isotig01410 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 151 |

3.3. Candidate Genes Associated to Depth

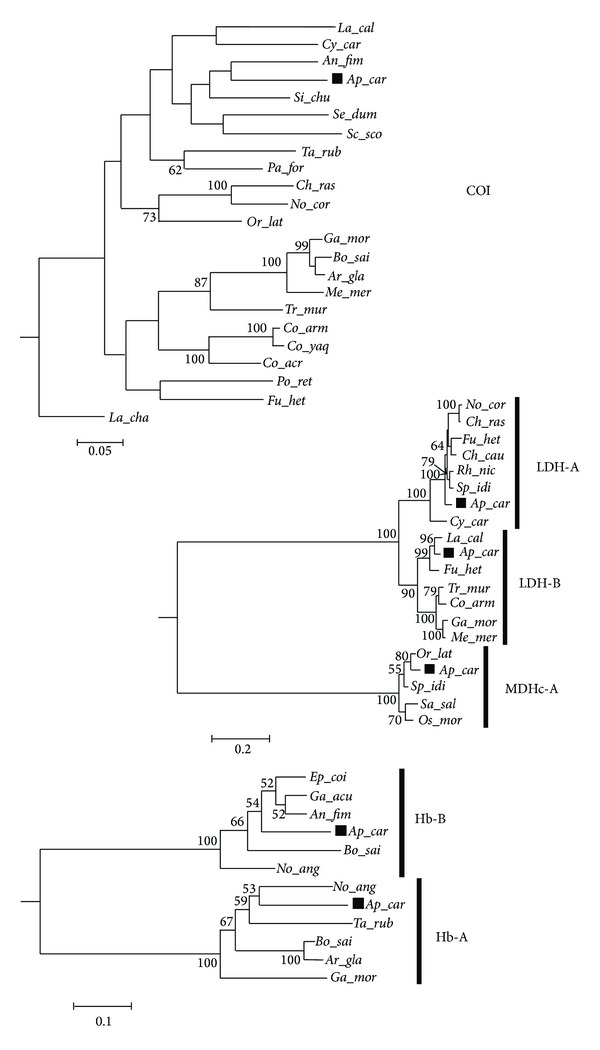

The predicted amino acid sequences of A. carbo functional genes putatively related to depth adaptations were compared to those deposited in NCBI database for homologies searches. Complete alignments of orthologous protein sequences from the set of functional genes that have been reported as responsive to depth adaptations included representatives of Teleosts belonging to several families (Table 6). Exploring the levels of similarities expressed as percentage of amino acid identity or number of amino acid that differ among sequences between A. carbo and other fish species (Table 7) brings evidence supporting the fact that deep-living as well as polar species are not the most similar to the black scabbard fish. We attempted to reconstruct the phylogenies for those species using amino acid sequences of functional genes (LDH-A, LDH-B, MDHc-A, Hb-A and Hb-B) and corresponding mtCOI nucleotide sequences (Figure 4). The resulting trees showed similar topologies, suggesting that the signals embedded in these functional genes reflect evolutionary divergence among taxa rather than any enzyme adaptations relationships.

Table 6.

Species list with informations on their type of environment (M = marine, BR = brackish and FW = freshwater), climate, depth range (in meters) and the type of genes used in the study with relative Genbank accession numbers.

| Order | Family | Species | Common name | Environment | Climate | Depth range | Gene | NCBI Acc. Nr |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perciformes | Trichiuridae | Aphanopus carbo | Black scabbardfish | M | Deep-water | 200–1700 | COI | EU854076 |

| Beloniformes | Adrianichthydae | Oryzias latipes | Japanese rice fish | FW + BR | Subtropical | shallow | ACTA1, MDHc, MyHC, COI | NM_001104806, NM_001163134, XM_004071618, AB498066 |

| Scorpaeniformes | Hexagrammidae | Pleurogrammus azonus | Okhotsk atka mackerel | M | Temperate | 0–240 | ACTA1 | AB073381 |

| Perciformes | Scombridae | Scomber scombrus | Atlantic mackerl | M | Temperate | 0–200 (0–1000) | ACTA1, COI | EF607093, KC015895 |

| Perciformes | Percihcthyidae | Siniperca chuatsi | Mandarin fish | FW | Temperate | 10 | ACTA1, MyHC, COI | AY395872, AY454304, NC_015822 |

| Perciformes | Sparidae | Sparus aurata | Gilthead seabream | M | Temperate | 1–30 (1–150) | ACTA1 | AF190473 |

| Perciformes | Sphyraenidae | Sphyraena idiastes | Pelican barracuda | M | Tropical | 3–24 | ACTA1, LDH-A, MDHc, mMDH | AF503593, SIU80001, AF390559, AF390561 |

| Tetraodontiformes | Tetraodontidae | Takifugu rubripes | Japanese pufferfish | M + FW + BR | Temperate | 0–200 (0–1000) | Hb-A, mMDH, COI | XM_003964767, XM_003965959, HM102315 |

| Scorpaeniformes | Anoplopomatidae | Anoplopoma fimbria | Sablefish | M | Deep-water | 0–2740 | Hb-B, COI | BT082849, JQ353978 |

| Perciformes | Serranidae | Epinephelus coioides | Orange-spotted grouper | M + BR | Subtropical | 1–100 | Hb-B | GU982530 |

| Gasterosteiformes | Gasterosteidae | Gasterosteus aculeatus | Three-spined stickleback | M + FW + BR | Temperate | 0–100 | Hb-B | NM_001267638 |

| Perciformes | Nototheniidae | Notothenia coriiceps | Black rockcod | M | Polar | 0–550 | LDH-A, MyHC, COI | AF079822, AJ243767, EU326390 |

| Perciformes | Nototheniidae | Notothenia angustata | Maori chief | M | Temperate | 0–100 | Hb-A, Hb-B | P62363, P29628 |

| Gadiformes | Macrouridae | Coryphaenoides armatus | Abyssal grenadier | M | Deep-water | 282–5180 | LDH-B, MyHC, COI | AJ609232, AB330140, FJ164497 |

| Gadiformes | Gadidae | Gadus morhua | Atlantic cod | M + BR | Temperate | 0–600 | LDH-B, COI | AJ609233, KC015385 |

| Gadiformes | Gadidae | Arctogadus glacialis | Arctic cod | M | Deep-water | 0–1000 | Hb-A, COI | Q1AGS4, KC015200 |

| Perciformes | Latidae | Lates calcarifer | Barramundi | M + FW + BR | Tropical | 10–40 | LDH-B, COI | FJ439507, JQ431879 |

| Gadiformes | Gadidae | Merlangius merlangus | Whiting | M | Temperate | 30–100 (10–200) | LDH-B, COI | AJ609234, JQ623954 |

| Cyprinodontiformes | Poeciliidae | Poecilia reticulata | Guppy | FW + BR | Tropical | Shallow | LDH-B, COI | EF408825, JX968696 |

| Gadiformes | Macrouridae | Trachyrincus murrayi | Roughnose grenadier | M | Deep-water | 0–1630 | LDH-B, COI | AJ609235, AP008990 |

| Perciformes | Channichthyidae | Chionodraco rastrospinosus | Ocellated icefish | M | Polar | 0–1000 | LDH-A, COI | AF079829, EU326337 |

| Perciformes | Pomacentridae | Chromis caudalis | Blue-axil chromis | M | Tropical | 15–55 | LDH-A | AY289558 |

| Perciformes | Gobiidae | Rhinogobiops nicholsii | Blackeye goby | M | Subtropical | ?-106 | LDH-A | AF079534 |

| Cypriniformes | Cyprinidae | Cyprinus carpio | Common carp | FW + BR | Subtropical | shallow | LDH-A, MyHC, COI | AF076528, D89992, HQ960709 |

| Cyprinodontiformes | Fundulidae | Fundulus heteroclitus | Mummichog | M + FW + BR | Temperate | shallow | LDH-A, LDH-B, COI | L43525, L23792, EU524629 |

| Osmeriformes | Osmeridae | Osmerus mordax | Rainbow smelt | M + FW + BR | Temperate | 0–425 | MDHc, mMDH | BT075651, BT075600 |

| Salmoniformes | Salmonidae | Salmo salar | Atlantic salmon | M + FW + BR | Temperate | 10–23 (0–210) | MDHc, mMDH | BT060183, BT048216 |

| Gadiformes | Macrouridae | Coryphaenoides acrolepis | Pacific grenadier | M | Deep-water | 900–1300 | MyHC, COI | AB330141, JQ354060 |

| Gadiformes | Macrouridae | Coryphaenoides yaquinae | n.a. | M | Deep-water | 3400–5800 | MyHC, COI | AB330139, GU440291 |

| Perciformes | Cirrhitidae | Paracirrhites forsteri | Blackside hawkfish | M | Tropical | 5–35 | MyHC, COI | AJ243770, HQ561521 |

| Perciformes | Carangidae | Seriola dumerili | Greater amberjack | M | Subtropical | 18–72 (1–360) | MyHC, COI | AB032020, KC015917 |

| Gadiformes | Gadidae | Boreogadus saida | Polar cod | M + BR | Polar | 0–400 | Hb-A, Hb-B, COI | DQ125471, Q1AGS6, KC015250 |

Table 7.

Comparison of protein sequences of depth related genes between Aphanopus carbo database (All_gs454_xxx) and other fishes. Diff.: amino acid differences; Id. %: percentage of identity; Gaps: number of gaps introduced in the complete alignment and Acc. nr.: NCBI Accession number. 1Partial sequence; 2only AA sequence available.

(a) LDH-A (332 AA)

| All_gs454_00149 vs. | Diff. | Id. % | Gaps | Acc. nr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sphyraena idiastes | 16 | 95.18 | 0 | U80001 |

| Rhinogobiops nicholsii | 17 | 94.88 | 0 | AF079534 |

| Chromis caudalis | 21 | 93.67 | 0 | AY289558 |

| Chionodraco rastrospinosus | 26 | 92.17 | 1 | AF079829 |

| Notothenia coriiceps | 27 | 91.87 | 1 | AF079822 |

| Fundulus heteroclitus | 27 | 91.87 | 0 | L43525 |

| Cyprinus carpio | 44 | 86.75 | 0 | AF076528 |

(b) MDHc-A (333 AA)

(c) Actin-1 (375 AA)

| All_gs454_00104 vs. | Diff. | Id. % | Gaps | Acc. nr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scomber scombrus 1 | 0 | 100 | 0 | EF607093 |

| Iniperca chuatsi 1 | 0 | 100 | 0 | AY395872 |

| Oryzias latipes 1 | 1 | 99.73 | 0 | NM_1104806 |

| Pleurogrammus azonus 1 | 1 | 99.73 | 0 | AB073381 |

| Coryphaenoides acrolepis 1 | 1 | 99.73 | 0 | AB021649 |

| Coryphaenoides cinereus 1 | 1 | 99.73 | 0 | AB021651 |

| Coryphaenoides armatus 2a | 2 | 99.47 | 0 | AB086240 |

| Coryphaenoides yaquinae 2a | 2 | 99.47 | 0 | AB086242 |

| Coryphaenoides acrolepis 2a | 2 | 99.47 | 0 | AB021650 |

| Coryphaenoides cinereus 2a | 2 | 99.47 | 0 | AB021652 |

| Cyprinus carpio 1 | 2 | 99.47 | 0 | AY395870 |

| Sphyraena idiastes 1 | 3 | 99.20 | 0 | AF503593 |

| Coryphaenoides armatus 2b | 5 | 98.67 | 0 | AB086241 |

| Coryphaenoides yaquinae 2b | 5 | 98.67 | 0 | AB086243 |

| Aphanopus carbo 2a | 6 | 98.40 | 0 | All_gs454_00102 |

| Sparus aurata 1 | 9 | 97.60 | 0 | AF190473 |

(d) LDH-B (334 AA)

(e) MyHC1 (305 AA)

| All_gs454_00001 vs. | Diff. | Id. % | Gaps | Acc. nr. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paracirrhites forsteri | 53 | 94.95 | 0 | AJ243770 |

| Seriola dumerilii | 54 | 94.86 | 0 | AB032020 |

| Siniperca chuatsi | 59 | 94.38 | 0 | AY454304 |

| Oryzias latipes | 62 | 94.10 | 2 | XM_4071618 |

| Cyprinus carpio | 69 | 93.43 | 2 | D89992 |

| Coryphaenoides acrolepis | 86 | 91.82 | 1 | AB330141 |

| Notothenia coriiceps | 86 | 91.82 | 1 | AJ243767 |

| Coryphaenoides yaquinae | 89 | 91.53 | 1 | AB330139 |

| Coryphaenoides armatus | 92 | 91.25 | 1 | AB330140 |

(f) Hb-A1 (143 AA)

(g) Hb-B1 (146 AA)

Figure 4.

At the top: molecular phylogenetic tree of COI gene estimated by the HKY nucleotide substitution model constructed by neighbor joining and rooted including the sequence of Latimeria chalumnae (acc. nr.: NC_001804); in the middle: NJ tree of LDH and MDH genes; and at the bottom: NJ tree of globin (Hb) gene. Numbers in proximity of the nodes denote the bootstrap value (above 50%) out of 1000 replicates. The scale indicates the evolutionary distance of the base substitution per site. Taxon coding includes the first two letters for the genus followed by three letters for the species name (see Table 6). A black square helps to locate Aphanopus carbo in the trees.

The lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A: isotig01401) was encountered abundantly in the muscle tissue (Table 5, Figure 2) and its comparison with other orthologous sequences differs for a number of amino acids between 16 and 44. One indel at position 75 had to be added to the two polar species to obtain a complete alignment (Table 7). The percentage of identity was higher with the strictly marine species ranging between 95.2 and 93.7%. Unfortunately, no sequences from neither deep-sea nor abyssal fishes were available for comparison. On the other hand, lactate dehydrogenase B (LDH-B: isotig01423) in A. carbo was highly represented in the heart while very scarcely recorded in the other tissues (Table S1). The largest sequence divergence in terms of amino acid substitutions ranges between 47 and 55 when compared with deep-water macrourids, and similarly to LDH-A, an indel had to be added in the sequences of the gadiform species at position 76 to obtain a complete alignment (Table 7). Previous studies on benthopelagic fish report a significant decline of LDH activities with increasing water depth [39]. However, it is known that variation in enzyme activities of fish at a given depth is influenced by feeding behaviour and locomotory modes [40, 41].

Cytosolic malate dehygrogenase A (MDHc-A: isotig01010) was detected in most of the tissues, with the exception of the muscle (Table S1). An isoform of MDHc was also detected but its sequence covered only the last 110 amino acids (isotig01731). However the type of substitutions and tissue expression pattern (Table S1) according to Merrit and Quattro [42], lead us to believe that this cytosolic isoform is MDHc-B. It has been reported that the two teleost MDHc isozymes are the products of a gene duplication event after the separation of teleosts and tetrapods (see [42] and references therein) although the exact timing of this duplication has not been inferred.

Further comparison analyses were carried out only for MDHc-A, with orthologous sequences obtained from NCBI database where only shallow-water fish sequences were available. The complete alignment did not include any indel, and sequences differed from A. carbo between 15 and 35 amino acid substitutions, representing a percentage of identity ranging from 95.5 to 89.5%.

Two α-skeletal actins were detected from the A. carbo database: the isoform 1 (isotig01459), expressed in shallow-water species and probably not functioning in abyssal fishes, and the isoform 2a (isotig01561). The mutations specific for A. carbo in the actin 2a were the substitutions Asp3Glu, Ala155Ser (a mutation also common with the isoform 2b [7]), Ser234Val, Val165Ile, Leu261Val, and finally Ala278Thr. This type of isoform was reported in other deep-sea species as Coryphaenoides acrolepis, C. cinereus, C. yaquinae, and C. armarus [7]. The isoform 2b, so far reported only in abyssal species, was not detected in A. carbo.

Actins 1 and 2a were significantly expressed in muscle tissue with evidence of its presence also in the heart (Table S1). Direct comparison of A. carbo actin 1 with orthologous sequences reported for other marine and deep-water species differed by just 1 amino acid at position 3 (Table 7). The number of substitutions increases to 2 when this sequence is compared to the isoform 2a of Coryphaenoides species (substitution at position 155) and to 5 amino acids replacement (Table 7) when compared to the isoform 2b, two of which are unique (positions 116 and 137) [7]. Actin has a function in polymerization of G-actin to F-actin in neutral salts. While the volume is increased following polymerization, the reaction is strongly affected by high pressure [43]. It is reported that the substitutions of Val54Ala or Leu67Pro reduced the volume change associated with actin polymerization [7].

The assemblage of the myosin heavy chain protein (MyHC: isotig02568 and isotig1394) obtained in A. carbo was incomplete (All_gs454_000756 and All_gs454_000001) containing a gap of 711 amino acids at the positions from 171 to 882 of the 1933 AA of the complete sequence. Unfortunately, within this gap there are the two loop regions with characteristic structures that are uniquely reported for deep-sea fish: loop-2 region is shorter and the loop-1 region has a proresidue [9]. MyHC was almost uniquely found in muscle tissue (Table S1) and for comparison analyses with orthologous genes from other fish we only used the last 305 AA (All_gs454_000184) of the complete sequence. The lowest number of amino acid substitutions ranged between 53 and 69 (corresponding to sequence identity between 94.95 to 93.43%) when the sequence from A. carbo is compared to its relative shallow water marine and freshwater species, while this value increases up to 92 amino acid substitutions (and corresponding sequence identity of 91.25%) when compared to its relatives from deep water or polar regions (Table 7).

Variation in globin sequences was analysed exploring the α 2- and β 2-chains (Hb-A: isotig00247 and Hb-B: isotig00163), whose relative expressions were detected more abundantly in the spleen, followed by liver, heart, brain, and muscle and virtually absent in the gonads (Figure 2, Table 5). Comparison analyses with orthologous sequences of deep-sea gadiforms and a notothenoid indicate that the number of amino acid substitutions ranged between 39 and 53 (Hb-A) and between 31 and 42 (Hb-B). The complete alignments included the additional single indel for the α 2-chain of Notothenia angustata at position 102. Notothenioids acquired a completely different globin genotype with respect to other teleostean groups. The Antarctic ichthyofauna (dominated by a single taxonomically uniform group) lost its globin multiplicity in correlation with temperature stability. On the other hand, for the Arctic ichthyofauna it may have been advantageous to maintain a multiple globin system, helping to deal with environmental changes and metabolic demands [44].

Selective pressure in the site-by-site patterns among species was evaluated for LDH-A, -B, MDHc, and ACTA1 (isoform 1). There was no evidence of positive selection at the nucleotide site level in any of those genes whose global ω value was very low in all cases (from 0 in ACTA1 and 0.032 in LDH-B) (Table S2). The proportion of sites supporting positive selection, the model M2, was null (LDH-A and -B) or extremely low (0.3% in MDHc and 1.6% in ACTA1) (Table S2). These results indicate that the evolution of these four genes in teleosts is constrained by very stringent selective pressure (model probabilities for M1 versus M2 ranging from 87% in MDHc and 88% in all others).

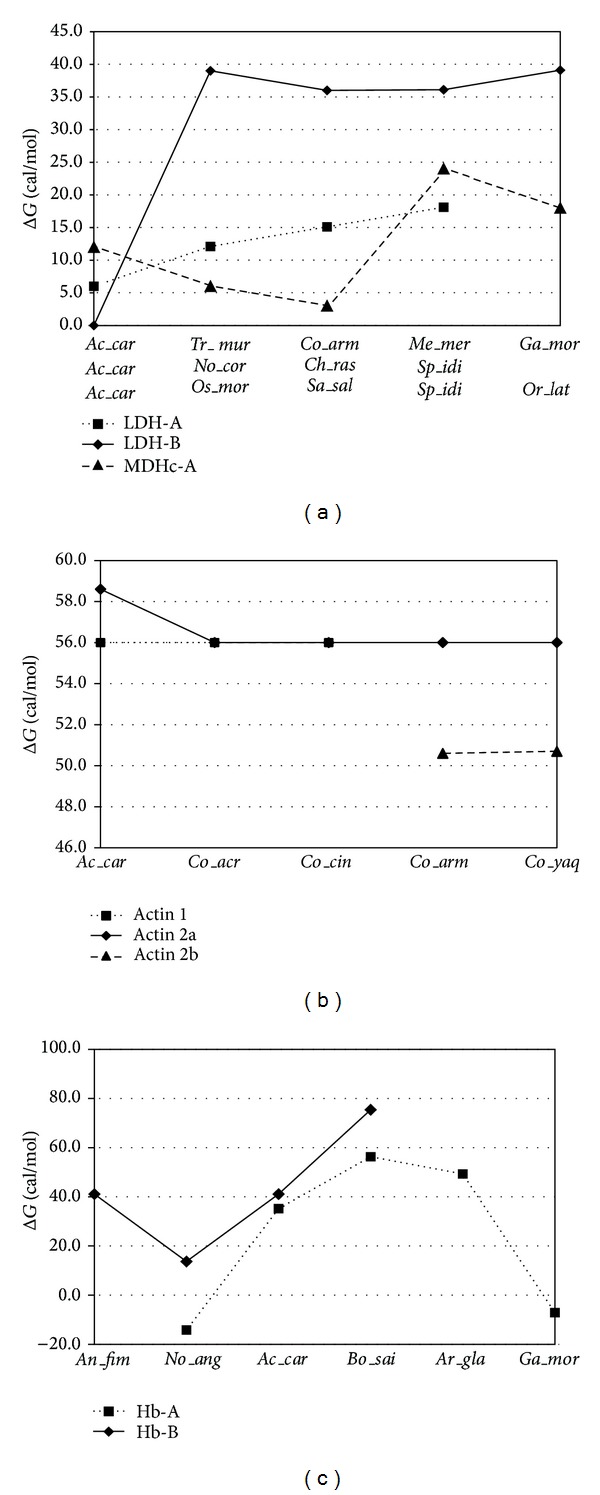

In terms of protein stability calculated as Gibbs free energy and taking into consideration kinetic and thermodynamic quantities, we explored only the functional genes for which the complete sequences were obtained (Figure 5). In this context, protein stability is defined by the ability of a protein to retain its structural conformation or its activity when subjected to physical or chemical manipulations; therefore the energy consumed by activation to promoted folding has to be compensated by thermal stability provided by the energy of denaturation [35]. Hence, protein stability is quantitatively calculated by the standard Gibbs energy change (ΔG), allowing comparison of stabilities for different proteins [45].

Figure 5.

Comparative plots of normalised difference in protein stability (ΔG) for different functional genes among several representative species. Taxon coding includes the first two letters for the genus followed by three letters for the species name (see Table 6).

The normalised difference in protein stability (ΔG) of lactate dehydrogenase A (LDH-A) was lower in A. carbo compared to fish from polar waters and tropical marine (Figure 5). This gradual variation was primarily dictated by the lower contributions of leucine and lysine in the hydrophobic trend of kinetic calculation in the A. carbo sequence (Table S3). The substantial drop in ΔG of LDH-B in A. carbo compared to the orthologous sequences of polar, abyssal, and shallower marine fishes (Figure 5) was due to a larger contribution of glutamic acid (Table S3) promoting the thermal denaturation of the protein. Other studies investigating kinetic, physical properties and ability to withstand high pressure of LDH-B of two gadiformes support our calculations showing that the enzyme from the deep-sea species has a significant increased tolerance to pressure and higher thermostability [6]. To provide protection to A. carbo LDH-B from pressure and temperature denaturation, osmolytes might play an essential role. Experiments adding Trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) to samples resulted in substantial increment of activity of LDH-B under conditions at which the enzyme was previously sensitive [6].

In the cytosolic malate dehygrogenase A (MDHc-A) there was a sharp decrease in protein stability of marine fishes going from shallower to deeper waters (no sequences of abyssal species were available). Lowest values are encountered in the sequences of the two euryhaline species included in the comparison (Figure 5). This progressive decrement in stability was associated to the larger contribution of aspartic acid (Table S3), also a promoter of thermal denaturation of the protein. The responses to pressure and temperature of soluble enzymes like LDH and MDH differ adaptively among species found at different depths.

The isoforms 1 and 2a of α-skeletal actin of A. carbo showed very similar numerical values of ΔG compared to their homologues of deep-water (actin 1) and deep and abyssal water (actin 2a). Protein stability drops substantially when these two isoforms were compared with actin 2b, only present in abyssal species (Figure 5). Such reduction in stability was due to a higher number of hydrophobic amino acids contributing to the thermodynamic calculation (Table S3). Morita [7] reported that the substitutions of Gln137Lys and Ala155Ser generate a mechanism for stabilizing enzyme-substrate interactions under high pressure.

Comparing the stability of globin, α 2-chain (Hb-A), in shallow, deep-water, and polar fish, the larger ΔG was found in polar and deep-water cods, followed by A. carbo before dropping to negative values for the shallower representatives of Antarctic and temperate environments (Figure 5). Stability of protein in A. carbo and its deep-water relatives was linked to larger contributions by leucine in the kinetic calculations promoting folding and thermal stability (Table S3). The stability as ΔG of globin sequences of the β 2-chains (Hb-B) showed a very similar trend as in Hb-A (although there were no negative values), and the two deep-living species had very similar protein stability value. Variation in ΔG among environments was linked to the balanced contribution of hydrophobic amino acids promoting folding versus those lowering thermal stability (Table S3).

Although for key enzymes it was found that adaptive differences among species at different depths showed structural changes as well as structural stability (reviews in: [4–6]), several studies remarked on the importance of regulatory regions of the genome acting on gene regulation (see [46]). Promoter regions often work together with other cys-regulatory elements (e.g., transcription factors binding sites, enhancers, silencers, and insulators) to regulate the transcription and expression of mRNA in a specific tissue at different times and places throughout the genome. In addition, in regards to adaptation to depth, it is remarked the importance of osmolyte concentrations of methylamines (TMAO is the most relevant). These are protein stabilizers that counteract inhibition of proteins by hydrostatic pressure [47–49].

Finally, we should also take into account the stress imposed on this fishes being captured at a depth range of 1100–1250 m and brought to surface in at least 3–5 hours. By the time specimens of black scabbardfish reach the surface they are already dead or dying; therefore the expression of some of the transcripts might be different if compared to a transcriptome of a fish sampled at a thousand meters depth. Notwithstanding, several experiments using model species have been targeting specific genes linked to stress factors [50] and this might prove useful in interpreting transcriptomes of animals undergoing stressful conditions before being sampled.

On the bases of this preliminary but encouraging results, we are planning to explore further deep water adaptivity employing different NGS sequence technology and experimental design, for instance using individual RADseq approach on a larger number of specimens caught at deep or shallow waters or by comparing sister species that live at different depth levels.

3.4. EST-SSR Resources for Population Genetics

In this study, a total of 153 EST-SSRs were detected in 142 contigs (3.87%) with a frequency of one EST-SSR per 27,69 kb sequence (Table 8). A further selection was made taking into account the type of repeats, size of the fragment, and quality of the primer sets, reducing the EST-SSR to 98. Some of those microsatellite markers were found in one tissue but not in others (16.3%), while others resolved to be found in more than one tissue (83.7%). Among the identified EST-SSRs, tri-nucleotide repeats represented the largest portion (40.8%), followed by di-nucleotide (28.6%), and tetra-nucleotide (25.7%), and only 2 EST-SSRs penta-nucleotide were identified (Table S4). Primer pairs have sizes ranging between 19 and 25 bp and melting temperatures from 57.1°C to 61.2°C, while expected PCR products are 100 to 280 bp in length. None of these EST-derived primer pairs have been tested for neutrality; therefore not all may be suitable for basic population genetic studies.

Table 8.

Statistics of EST-SSRs identified in Aphanopus carbo transcriptome.

| Searching item | Numbers |

|---|---|

| Total number of sequences examined | 7,920 |

| Total size of examined sequences (bp) | 4,235,839 |

| Total number of identified SSRs | 153 |

| Number of SSR containing sequences | 142 |

| Number of sequences containing more than 1 SSR | 9 |

| Number of SSRs present in compound formation | 8 |

| Di-nucleotide | 63 |

| Tri-nucleotide | 52 |

| Tetra-nucleotide | 35 |

| Penta-nucleotide | 3 |

4. Conclusions

The transcriptome analysis of A. carbo, revealed a comprehensive set of genes expressed in six tissues, producing over 8,000 genes, 55.6% of which annotated by similarity to known proteins or nucleotide sequences from freely accessible database. The transcriptome of black scabbardfish sets the stage for expanding the genetic resources available while providing sets of genes that are likely tied with physiological adaptations to depth, particularly to low temperature and high pressure factors. This study represents the first transcriptome analysis for a deep-sea fish providing insights based on comparison analyses of homologous depth-related functional genes from shallow, deep-water, and abyssal fish highlighting similarities for A. carbo isozyme patterns and stability to other bathypelagic fishes. Direct sequence comparison suggested that the signals embedded in these functional genes reflect evolutionary divergence among taxa rather than any kind of enzyme adaptations. Organisms are adapted to deep-sea environment and their physiological tolerance may vary among taxa as well as their enzymatic activities under extreme conditions. Osmolyte concentrations as protein stabilizers that counteract inhibition of proteins by hydrostatic pressure [6, 47–49] play a key role in deep-sea adaptation. Furthermore, contribution to adaptation is also provided by promoter regions that together with cys- and trans-regulatory elements work concertedly, at the mRNA transcription level, to drive the expression of a gene in a specific tissue or at a specific time [46].

The strong correlation detected between the values of standardized contigs frequency with the expression level of the gene by qPCR supports the use of our data to explore gene expression patterns in A. carbo.

Finally, considering the importance of this species for fishery management, a further exploration of this database has provided the characterization of new EST-SSR markers as additional resource for basic population genetic studies as well as tagging and mapping of genes.

Supplementary Material

As supplementary material we included: amplification plots of all genes selected for this study in different tissue from Aphanopus carbo (Figure S1); a summary table of contig frequency in all tissues for those genes associated to depth not listed in Table 3 (Table S1); details on outputs related to the selection models for four teleost genes associated to depth (Table S2); values of Gibbs free energy calculations in terms of kinetic and thermodynamic quantities for all depth-related genes (Table S3); and the list of EST-SSR markers (Table S4).

Acknowledgments

All molecular work was supported by the research Projects DEECON (European Science Foundation, under the EUROCORES programme, proposal no. 06-EuroDEEP-FP-008) and ReDEco (MarinERA programme funded by the EU FP6 ERA-NET Scheme, MARIN-ERA/MAR/0003/2008). Specimens of A. carbo were provided by the CONDOR Project (EEA Grants Financial Mechanism, Iceland, Liechtenstein and Norway, proposal no. PT0040). The authors are thankful to captain, crew, and technicians onboard of the R/V Arquipelago for their excellent contribution while at sea. Sergio Stefanni is a research fellow supported by the Marie Curie grant cofunded by the EU under the FP7-People-2012-COFUND; Cofunding of Regional, National and International Programmes, GA no. 600407 and the Bandiera Project RITMARE. IMAR/DOP is funded through the pluri-annual and programmatic funding scheme as research unit number 531 and associate laboratory number 9. The authors are also grateful to Conceição Egas for the support provided at Biocant. Last, but not least, the authors thank three anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions that greatly improved the paper.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interests regarding the publication of this paper.

Authors' Contributions

Sergio Stefanni conceived the study and design, collected samples, participated in the data analysis, and drafted the paper. Raul Bettencourt contributed to gene validation experiments and discussion. Miguel Pinheiro and Gianluca De Moro developed the pipe-line analysis for all functional annotations and the SQL database. Lucia Bongiorni and Alberto Pallavicini participated in the structure, discussion, and paper drafting.

References

- 1.Somero GN. Adaptations to high hydrostatic pressure. Annual Review of Physiology. 1992;54:557–577. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.54.030192.003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Childress JJ, Nygaard MH. The chemical composition of midwater fishes as a function of depth of occurence off southern California. Deep-Sea Research and Oceanographic Abstracts. 1973;20(12):1093–1109. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Childress JJ, Somero GN. Depth-related enzymic activities in muscle, brain and heart of deep-living pelagic marine teleosts. Marine Biology. 1979;52(3):273–283. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Somero GN. Biochemical ecology of deep-sea animals. Experientia. 1992;48(6):537–543. doi: 10.1007/BF01920236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sebert P. Fish at high pressure: a hundred year history. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A. 2002;131(3):575–585. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(01)00509-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brindley AA, Pickersgill RW, Partridge JC, Dunstan DJ, Hunt DM, Warren MJ. Enzyme sequence and its relationship to hyperbaric stability of artificial and natural fish lactate dehydrogenases. PLoS ONE. 2008;3(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002042.e2042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morita T. Structure-based analysis of high pressure adaptation of α-actin. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2003;278(30):28060–28066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302328200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morita T. Studies on molecular mechanisms underlying high pressure adaptation of α-actin from deep-sea fish. Bulletin of Fisheries Research & Development Agency. 2004;13:35–77. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morita T. Comparative sequence analysis of myosin heavy chain proteins from congeneric shallow- and deep-living rattail fish (genus Coryphaenoides) The Journal of Experimental Biology. 2008;211(9):1362–1367. doi: 10.1242/jeb.017137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morita T. High-pressure adaptation of muscle proteins from deep-sea fishes, Coryphaenoides yaquinae and C. armatus . Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1189:91–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hourdez S, Weber RE. Molecular and functional adaptations in deep-sea hemoglobins. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 2005;99(1):130–141. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2004.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tucker DW. Studies on Trichiuroid fishes—3. A preliminary revision of the family Trichiuridae. Bulletin of the British Museum (Natural History) Zoology. 1956;4:73–131. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Martins MR, Leite AM, Nunes ML. Peixe-espada-preto. Algumas notas ácerca da pescaria do peixe-espada-preto. Instituto Nacional de Investigação das Pescas, 1987.

- 14.FAO. Fishstat. FAO Fisheries Department, Fishery Information, Data and Statistics Unit, 2002.

- 15.Machete M, Morato T, Menezes G. Experimental fisheries for black scabbardfish (Aphanopus carbo) in the Azores, Northeast Atlantic. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2011;68(2):302–308. [Google Scholar]

- 16.ICES. ICES CM 2008/ACOM :14. Copenhagen, Denmark: ICEC Headquarters; 2008. Report of the Working Group on the Biology and Assssment of Deep-Sea Fisheries Resources (WGDEEP) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Figueiredo I, Bordalo-Machado P, Reis S, et al. Observations on the reproductive cycle of the black scabbardfish (Aphanopus carbo Lowe, 1839) in the NE Atlantic. ICES Journal of Marine Science. 2003;60(4):774–779. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morales-Nin B, Sena-Carvalho D. Age and growth of the black scabbard fish (Aphanopus carbo) off Madeira. Fisheries Research. 1996;25(3-4):239–251. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Longmore C, Trueman CN, Neat F, et al. Ocean-scale connectivity and life cycle reconstruction in a deep-sea fish. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. 2014:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stefanni S, Knutsen H. Phylogeography and demographic history of the deep-sea fish Aphanopus carbo (Lowe, 1839) in the NE Atlantic: vicariance followed by secondary contact or speciation? Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 2007;42(1):38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nagaraj SH, Gasser RB, Ranganathan S. A hitchhiker’s guide to expressed sequence tag (EST) analysis. Briefings in Bioinformatics. 2007;8(1):6–21. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbl015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hudson ME. Sequencing breakthroughs for genomic ecology and evolutionary biology. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2008;8(1):3–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-8286.2007.02019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ellegren H. Sequencing goes 454 and takes large-scale genomics into the wild. Molecular Ecology. 2008;17(7):1629–1631. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bettencourt R, Pinheiro M, Egas C, et al. High-throughput sequencing and analysis of the gill tissue transcriptome from the deep-sea hydrothermal vent mussel Bathymodiolus azoricus. BMC Genomics. 2010;11(1, article 559) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lesniewski RA, Jain S, Anantharaman K, Schloss PD, Dick GJ. The metatranscriptome of a deep-sea hydrothermal plume is dominated by water column methanotrophs and lithotrophs. The ISME Journal. 2012;6(12):2257–2268. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2012.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu J, Gao W, Zhang W, Meldrum DR. Optimization of whole-transcriptome amplification from low cell density deep-sea microbial samples for metatranscriptomic analysis. Journal of Microbiological Methods. 2011;84(1):88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2010.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shi Y, McCarren J, Delong EF. Transcriptional responses of surface water marine microbial assemblages to deep-sea water amendment. Environmental Microbiology. 2012;14(1):191–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefanni S, Bettencourt R, Knutsen H, Menezes G. Rapid polymerase chain reaction-restriction fragment length polymorphism method for discrimination of the two Atlantic cryptic deep-sea species of scabbardfish. Molecular Ecology Resources. 2009;9(2):528–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2008.02470.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology. 1990;215(3):403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thompson JD, Gibson TJ, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins DG. The CLUSTAL X windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Research. 1997;25(24):4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 1987;4(4):406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang Z. PAML 4: a program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2007;24(8):1586–1591. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prashanth Kumar S, Meenatchi M. Virtual quantification of protein stability using applied kinetic and thermodynamic parameters. IIOAB Letters. 2011;1:21–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thiel T, Michalek W, Varshney RK, Graner A. Exploiting EST databases for the development and characterization of gene-derived SSR-markers in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) Theoretical and Applied Genetics. 2003;106(3):411–422. doi: 10.1007/s00122-002-1031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rozen S, Skaletsky H. Primer3 on the WWW for general users and for biologist programmers. Methods in Molecular Biology. 2000;132:365–386. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lee B-Y, Howe AE, Conte MA, et al. An EST resource for tilapia based on 17 normalized libraries and assembly of 116,899 sequence tags. BMC Genomics. 2010;11, article 278 doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Drazen JC, Seibel BA. Depth-related trends in metabolism of benthic and benthopelagic deep-sea fishes. Limnology and Oceanography. 2007;52(5):2306–2316. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sullivan KM, Somero GN. Enzyme activities of fish skeletal muscle and brain as influenced by depth of occurrence and habits of feeding and locomotion. Marine Biology. 1980;60(2-3):91–99. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siebenaller JF, Somero GN, Haedrich RL. Biochemical characteristics of macrourid fishes differing in their depths of distribution. The Biological Bulletin. 1982;163:240–249. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Merrit TJS, Quattro JM. Evolution of the vertebrate cytosolic malate dehydrogenase gene family: duplication and divergence in actinopterygian fish. Journal of Molecular Evolution. 2003;56(3):265–276. doi: 10.1007/s00239-002-2398-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ikkai T, Ooi T. The effects of pressure on F-G transformation of actin. Biochemistry. 1966;5(5):1551–1560. doi: 10.1021/bi00869a015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verde C, Balestrieri M, de Pascale D, Pagnozzi D, Lecointre G, Di Prisco G. The oxygen transport system in three species of the boreal fish family Gadidae: molecular phylogeny of hemoglobin. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(31):22073–22084. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513080200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Him HJ, Steif C, Vogl T, et al. Fundamentals of protein stability. Pure and Applied Chemistry. 1993;65:947–952. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hoekstra HE, Coyne JA. The locus of evolution: evo devo and the genetics of adaptation. Evolution. 2007;61(5):995–1016. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yancey PH, Fyfe-Johnson AL, Kelly RH, et al. Trimethylamine oxide counteracts effects of hydrostatic pressure on proteins of deep-sea teleosts. Journal of Experimental Zoology. 2001;289:p. 172. doi: 10.1002/1097-010x(20010215)289:3<172::aid-jez3>3.0.co;2-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yancey PH, Blake WR, Conley J. Unusual organic osmolytes in deep-sea animals: adaptations to hydrostatic pressure and other perturbants. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 2002;133(3):667–676. doi: 10.1016/s1095-6433(02)00182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Yancey PH, Rhea MD, Kemp KM, Bailey DM. Trimethylamine oxide, betaine and other osmolytes in deep-sea animals: depth trends and effects on enzymes under hydrostatic pressure. Cellular and Molecular Biology. 2004;50(4):371–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Prunet P, Cairns MT, Winberg S, Pottinger TG. Functional genomics of stress responses in fish. Reviews in Fisheries Science. 2008;16(1):157–166. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As supplementary material we included: amplification plots of all genes selected for this study in different tissue from Aphanopus carbo (Figure S1); a summary table of contig frequency in all tissues for those genes associated to depth not listed in Table 3 (Table S1); details on outputs related to the selection models for four teleost genes associated to depth (Table S2); values of Gibbs free energy calculations in terms of kinetic and thermodynamic quantities for all depth-related genes (Table S3); and the list of EST-SSR markers (Table S4).