Summary

Individual mammalian neurons express distinct repertoires of protocadherin (Pcdh) -α, -β and -γ proteins that function in neural circuit assembly. Here we show that all three types of Pcdhs can engage in specific homophilic interactions, that cell surface delivery of alternate Pcdhα isoforms requires cis interactions with other Pcdh isoforms, and that the extracellular cadherin domain EC6 plays a critical role in this process. Analysis of specific combinations of up to five Pcdh isoforms showed that Pcdh homophilic recognition specificities strictly depend on the identity of all of the expressed isoforms, such that mismatched isoforms interfere with cell-cell interactions. We present a theoretical analysis showing that the assembly of Pcdh-α, –β and –γ isoforms into multimeric recognition units, and the observed tolerance for mismatched isoforms can generate the cell surface diversity necessary for single-cell identity. However, competing demands of non-self discrimination and self-recognition place limitations on the mechanisms by which recognition units can function.

Introduction

An essential feature of neural circuit assembly is that the cellular processes (axons and dendrites) of the same neuron do not contact one another, but do interact with processes of other neurons. This feature requires “self-avoidance” between sister neurites of the same cell, a phenomenon that is highly conserved in evolution. Self-avoidance, in turn, requires a mechanism by which individual neurons distinguish self from non-self (Zipursky and Grueber, 2013).

A model for self-recognition, based on studies of the Drosophila Dscam1 gene (Schmucker et al., 2000), posits that individual neurons stochastically express unique combinations of distinct Dscam1 protein isoforms that are capable of engaging in highly specific homophilic trans interactions between proteins on apposing cell surfaces (Hattori et al., 2008). If neurites of the same neuron contact each other, the identical Dscam1 protein repertoire on their cell surfaces will result in homophilic interactions, which in turn leads to contact-dependent repulsion and neurite self-avoidance. In contrast, neurites from different neurons display distinct combinations of Dscam1 isoforms that do not engage in homophilic interactions, and thus not repel one another (Hattori et al., 2008).

The generation of extraordinary Dscam1 isoform diversity is a consequence of the unique structure of the Drosophila Dscam1 gene, and stochastic alternative splicing of Dscam1 pre-mRNAs (Miura et al., 2013; Neves et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2013; Zhan et al., 2004). In Drosophila this leads to the generation of 19,008 Dscam1 protein isoforms with distinct ectodomains, the vast majority of which can engage in highly specific homophilic interactions, apparently as monomers (Wojtowicz et al., 2004; Wojtowicz et al., 2007; Yagi, 2013) Genetic studies have shown that thousands of Dscam1 isoforms are required for neurite self-avoidance and non-self discrimination (Hattori et al., 2009). By contrast to Drosophila Dscam1, vertebrate Dscam genes do not generate significant cell surface diversity (Schmucker and Chen, 2009), suggesting that other genes may serve this function in vertebrates. The most promising candidates are the clustered protocadherin (Pcdh) genes (for recent reviews see (Chen and Maniatis, 2013; Yagi, 2012; Zipursky and Grueber, 2013; Zipursky and Sanes, 2010)).

In the mouse 58 Pcdh proteins are encoded by the Pcdha, Pcdhb, and Pcdhg gene clusters, which are arranged in tandem (Figure 1A) (Wu and Maniatis, 1999; Wu et al., 2001). Each of the Pcdh gene clusters contains multiple variable exons that encode the entire ectodomain composed of six extracellular cadherin domains (EC1-6), a transmembrane region (TM), and a short cytoplasmic extension. The Pcdhα and Pcdhγ gene clusters also contain three cluster-specific “constant” exons that encode a common intracellular domain (ICD). The last two variable exons in the Pcdha gene cluster, and the last three variable exons of the Pcdhg gene cluster are divergent from other Pcdh “alternate” isoforms and are referred to as “C-type” Pcdhs (Wu and Maniatis, 1999; Wu et al., 2001). Each of the variable exons is preceded by a promoter, and Pcdh expression occurs through promoter choice (Ribich et al., 2006; Tasic et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2002). Single cell RT-PCR studies in cerebellar Purkinje cells indicate that promoter choice of alternate isoforms is stochastic and independent on the two allelic chromosomes, whereas C-type Pcdhs are constitutively and biallelically expressed (Esumi et al., 2005; Hirano et al., 2012; Kaneko et al., 2006,). As a result, each neuron expresses approximately 15 Pcdh isoforms, including a random repertoire of 10 alternate α, β and γ isoforms and all 5 C-type isoforms (Yagi, 2012).

Figure 1. The Pcdh gene cluster encodes a large repertoire of cell surface recognition proteins.

(A) Schematic representation of the mouse Pcdh-a, -b and -g gene clusters. Variable exons of each subtype are differentially color-coded. Pcdha and Pcdhg variable exons are joined via cis-splicing to three constant exons. An example is shown for Pcdha9. Each variable exon encodes six EC domains, a TM, and a short cytoplasmic extension. The constant exons encode the common ICD domain.

(B) Schematic diagrams representing the four major subtypes of Pcdhs are shown.

(C) Schematic diagram of the cell aggregation assay. mCherry-tagged Pcdh proteins are expressed in K562 cells to assay for their ability to induce cell aggregation. As shown in the examples, cells expressing mCherry alone do not aggregate, while robust cell aggregation is observed with cells expressing PcdhγC3-mCherry.

(D) Survey of homophilic binding properties of all 58 Pcdh isoforms in the cell aggregation assay. Scale bar, 50 µm. (See also Figure S1B).

A critical functional connection between Drosophila Dscam1 isoforms and vertebrate clustered Pcdhs was made by the observation that conditional deletion of the mouse Pcdhg gene cluster in retinal starburst amacrine cells or in Purkinje cells results in defective dendritic self-avoidance (Lefebvre et al., 2012). This observation, in conjunction with the stochastic promoter choice mechanism, suggests that clustered Pcdhs may also mediate neurite self-avoidance by specifying single cell identity. Consistent with this suggestion, previous studies showed that a subset of Pcdh-γ isoforms can engage in specific homophilic interactions (Reiss et al., 2006; Schreiner and Weiner, 2010), suggesting that Pcdhs mediate contact-dependent repulsion in a manner similar to that of invertebrate Dscam1 proteins. However, the question of whether all Pcdh-α, –β, -γ and C-type isoforms engage in homophilic interactions, which would be required to generate sufficient diversity, has yet to be answered. Paradoxically, there are only 58 distinct clustered Pcdh isoforms in the mouse as compared to 19,008 Dscam1 isoforms with distinct ectodomains in Drosophila, raising the question of whether the molecular diversity provided by clustered Pcdhs is sufficient for discrimination between self and non-self. A possible answer to this question was proposed in a previous study that suggested that Pcdhγs can associate promiscuously as cis (same cell) tetramers that bind with homophilic specificity in trans (different cells)(Schreiner and Weiner, 2010). The large number of possible Pcdh tetramers would then dramatically increase cell surface diversity (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010; Yagi, 2012). However, In order to reach the level of diversity predicted by this model, and to determine whether alternate models are possible or likely, it is necessary to establish the binding behavior of all the clustered Pcdhs, including that of the Pcdh α and β isoforms, which were not previously tested.

Here we provide direct evidence that all but one of the 58 clustered Pcdh isoforms mediate highly specific homophilic trans interactions. We show that the EC6 domains of alternate Pcdhαs and PcdhγC4 inhibit cell surface delivery and that cis interactions involving the membrane proximal EC domains (EC5-EC6) of other Pcdh isoforms can relieve this inhibition. Furthermore, when multiple clustered Pcdh isoforms representing all three clusters are co-expressed, strict homophilic cell-cell recognition is observed. Remarkably, cells expressing as many as five different Pcdh isoforms display specific homophilic interactions in cell aggregation assays. However, aggregation is prevented by the expression of a single mismatched Pcdh isoform. In contrast, when the mismatch is generated by co-expression of classical N-cadherin (N-cad), there is no effect on homophilic recognition mediated by the Pcdhs, revealing a fundamental difference between the behaviors of classical cadherins and Pcdhs. Based on these findings we present a theoretical analysis of the dependence of Pcdh diversity on the number of subunits in putative cis-multimeric recognition units, and on the number of common isoforms that can be tolerated between two contacting cells without resulting in incorrect self-recognition. We discuss the competing requirements of self-recognition and non-self discrimination, and argue that these requirements raise questions concerning the validity of a current model in which the basic Pcdh recognition unit is a random assembly of Pcdh tetramers.

Results

Cluster-wide analysis of Pcdh-mediated homophilic interactions

The mouse Pcdh gene cluster encodes diverse subfamilies of cell surface proteins: 12 alternate Pcdhα, 22 Pcdhβ, 19 Pcdhγ isoforms and 5 C-type Pcdh-α or -γ isoforms (Figures 1A and 1B). We examined the ability of each Pcdh isoform to mediate homophilic recognition using a K562 cell aggregation assay. K562 cells are non-adherent in culture with no endogenous Pcdh expression, and thus provide an assay for homophilic interactions mediated by transfected clustered Pcdh cDNAs (Reiss et al., 2006; Schreiner and Weiner, 2010). It is important to note that while this aggregation assay provides an excellent system for studying homophilic interactions between Pcdh proteins on the cell surface, it cannot provide information regarding the self-avoidance (neurite repulsion) function of Pcdhs in the nervous system.

We carried out a systematic analysis of the homophilic interactions of all 58 Pcdh proteins (α, β, γ and C type Pcdhs) by transfecting cDNA plasmids encoding individual Pcdh C-terminal mCherry fusion proteins into K562 cells and visualizing cell aggregation. We found that all 22 Pcdhβs, 19 alternate Pcdhγs, and the C-type Pcdhs -αC2, -γC3 and -γC5 form aggregates when assayed individually (Figure 1D), We note that the size of the aggregates observed varies significantly (Figure S1B), which is likely the consequence of differences in expression, cell surface delivery, or intrinsic trans-binding affinities of individual Pcdh isoforms. By contrast, none of the alternate Pcdhα isoforms nor Pcdh-αC1 or -γC4 form aggregates (Figure 1D), presumably due to the lack of membrane localization (Bonn et al., 2007; Murata et al., 2004).

Pcdhβs, Pcdhγs, and a subset of C-type Pcdhs display highly specific homophilic interactions

The EC2 and EC3 domains, which display the highest level of amino acid sequence diversity among the EC domains (Figure S2A) (Wu, 2005) were previously shown to comprise the specificity-determining region for a subset of Pcdhγ isoforms (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010). In order to determine the stringency of recognition specificity, we generated pairwise sequence identity heat maps of the EC2-EC3 domains (Figures 2B and S2B). Using these heat maps, we identified Pcdh pairs with greater than 80% pairwise sequence identity in their EC2 and EC3 domains. If the most closely related Pcdhs within the same cluster fail to recognize each other thru heterophillic interactions, it is unlikely that the more distantly related Pcdhs would interact. Notably, among the closely related Pcdh pairs, Pcdhβ6-Pcdhβ8 and PcdhγA8-PcdhγA9 both share more than 90% sequence identity within their EC2-EC3 domains. Eight of the closely related Pcdhs were tested along with twelve more distantly related Pcdhs. In total, we tested 89 unique pairs of Pcdhs with sequence identity for non-self pairs ranging from 50–95% in their EC2-EC3 domains.

Figure 2. Pcdh-β, –γ, and C-type isoforms engage in specific homophilic interactions.

(A) Schematic diagram of the binding specificity assay. Cells expressing differentially tagged Pcdh isoforms are then mixed and assayed for homophilic or heterophilic interactions. A strict homophilic interaction is indicated by mixed red-and-green co-aggregates between cells expressing only the identical isoforms and segregation of separate red and green aggregates between cells expressing different isoforms.

(B) Heat map of pair-wise protein sequence identities of the EC2-EC3 domains of Pcdh isoforms and their evolutionary relationship is presented. Subsets of the isoforms within the boxed region were assayed. (See also Figure S2B).

(C–E) Pairwise combinations within each subtype Pcdhβ (C), Pcdhγ (D), and C-type (E) isoforms were assayed for their binding specificity. Scale bar, 50 µm. (See also Figure S3C).

Each protein was expressed with mCherry or mVenus fused to the C-terminus and tested for binding specificity (Figure 2A). Pairwise Pcdh isoform combinations were tested within each Pcdh subtype (Figures 2C–2E and S2C) and between different subtypes (Figure S2D). Only self-pairs on the matrix diagonals displayed intermixing of mCherry- and mVenus-expressing cells, while all non-self pairs exclusively segregate into red and green cell homophilic aggregates. Despite their high level of sequence identity, even the Pcdhβ6-Pcdhβ8 and PcdhγA8-PcdhγA9 pairs form separate, non-interacting homophilic cell aggregates. Thus, all of the Pcdh γ and β proteins tested display strict transhomophilic specificity.

Pcdhαs mediate homophilic recognition when delivered to the cell surface

As mentioned above, Pcdhα isoforms are not delivered to the plasma membrane when expressed alone (Bonn et al., 2007; Murata et al., 2004), so this likely explains why all of the Pcdhα isoforms fail to engage in homophilic interactions in the K562 assay (Figure 1D). We therefore used Pcdh constructs bearing an extracellular c-Myc tag to visualize cell surface localization by immunofluorescence in K562 cells. We first showed that Pcdh-β17, -γB6, and the C-type -αC2 and -γC3 isoforms, all of which engage in homophilic interactions (Figure 1D), can be detected on the cell surface (Figure 3A (ii–v)). By contrast, neither the wild type nor intracellular domain (ICD) deleted Pcdhα4 can be detected on the cell surface (Figure 3A (i and vi)). This observation is consistent with the idea that failure to detect homophilic interactions of Pcdhαs in the cell aggregation assay is due to failure of Pcdhαs to localize to the plasma membrane.

Figure 3. Pcdhα isoforms engage in specific homophilic interactions when delivered to the cell surface by co-expressed Pcdh-β or -γ isoforms.

(A) Surface expression of mCherry-tagged Pcdh constructs bearing an extracellular c-Myc tag were shown. White arrows indicate the c-Myc staining at cell-cell contacts. Scale bar, 10 µm.

(B) Cells transfected with single Pcdhα isoforms (upper panels) and cells co-transfected with Pcdhα isoforms and PcdhγB6ΔEC1 (lower panels) were assayed for aggregation. Scale bar, 50 µm.

(C) Cells expressing ΔEC1-Pcdhs alone (upper panels), Pcdhα4/ΔEC1-Pcdhs (middle panels) were assayed for aggregation. Cells co-expressing Pcdhα4 and a carrier ΔEC1-Pcdhs do not interact with cells expressing only the wild-type carrier Pcdhs (lower panels). Scale bar, 50 µm. (See also Figure S3C).

(D) Heat map of pairwise sequence identities of the EC2-EC3 domains of Pcdhα isoforms. The boxed region shows Pcdh-α4, -α7 and -α8, which share a high level of sequence conservation.

(E–F) Cells co-expressing pairs of differentially tagged Pcdhαs and ΔEC1-Pcdhs were assayed for co-aggregation.

Previous studies have shown that Pcdhγs can facilitate membrane delivery of Pcdhαs (Murata et al., 2004). We confirmed this finding with PcdhγB6 (Figure 3A (ix)) and in addition, found that Pcdhβ17 (Figure 3A (viii)) and the C-type Pcdh-αC2 and -γC3 isoforms (Figure 3A (vii and x)) could also facilitate membrane delivery of Pcdhα4. Deletion of Pcdh EC1 domains was previously shown to abrogate Pcdh homophilic interactions (Figure 3C (i–iv)) (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010) but not their cell surface delivery (Figure S3A (ii)). In order to determine whether Pcdhαs can directly mediate homophilic interactions, we co-expressed Pcdhα isoforms with ΔEC1-Pcdh isoforms, reasoning that cis interactions with these ΔEC1-Pcdh constructs would assist in cell surface delivery but would not participate in trans binding. Thus, the EC1-deleted “carrier” proteins should not affect the recognition specificity (see e.g. Figure 3C (ix – xii). We confirmed that all of the ΔEC1-Pcdh proteins tested can deliver Pcdhα4 to the cell surface (Figure 3A (xi–xiv)) and facilitate cell aggregation (Figure 3C (v–viii)). Consistent with these observations, Flag-tagged Pcdhα4 co-immunoprecipitates with mCherry fusions of each of the ΔEC1-Pcdhs or wild-type Pcdh carrier proteins tested (Figure S3B). Using carrier Pcdhs for membrane delivery, we found that all 12 alternate Pcdhαs mediate strict homophilic interactions (Figures 3B, S3D and S3E). Similar to the Pcdh -βs and –γs, EC1 deletion in Pcdhα4 abolished its homophilic binding activity when co-expressed with a carrier protein (Figure 3B (vii) and (xiv)).

In addition to the Pcdhα isoforms, PcdhγC4 and PcdhαC1 did not mediate homophilic interactions when transfected alone (Figure 1D). PcdhγC4 exhibits behavior similar to that of the Pcdhαs: its membrane delivery and homophilic interactions are promoted by co-transfection with carrier Pcdhs (Figure S3F, second row). By contrast, we found that PcdhαC1 homophilic interactions could not be rescued by co-expression with any of the carrier Pcdhs (Figure S3F, third row). To determine whether the cotransfected Pcdhα isoform defines binding specificity, we selected the closely related Pcdhα pairs, Pcdh-α8 and -α7 (97% identity in the EC2-EC3 domains) and Pcdh-α8 and -α4 (74% identity) for testing in cell aggregation assay (Figure 3D). Cells expressing the same Pcdhα isoform showed homophilic interactions (Figure 3E (ii)), whereas those expressing different Pcdhα isoforms did not interact (Figure 3E (i and iii)). Conversely, when the Pcdhα isoform is the same for all transfectants, but the carrier Pcdhs are varied (Figure 3F), intermixing of the red and green cells is observed between all transfectants, irrespective of the identity of the carrier Pcdh. These results demonstrate that the recognition specificity between cells co-transfected with an alternate Pcdhα and a carrier Pcdh depends only on the identity of the Pcdhα isoform.

Role of the membrane-proximal EC6 domain in cell surface localization

To identify the regions of Pcdhβ/γ proteins responsible for the carrier function, we produced an EC-domain deletion series of PcdhγB6 in which EC domains were successively deleted starting with EC1. Each of these constructs failed to mediate homophilic interactions (Figures 4A (i–vi) and S4G). We then co-transfected Pcdhα4 with each of the PcdhγB6 ΔEC constructs and assayed for cell aggregation. When co-transfected with Pcdhα4, aggregation was observed when up to four EC domains were deleted from PcdhγB6 (Figures 4A (vii–x) and S4G). Cell aggregation was not observed in co-transfectants in which the first five or all six EC domains were deleted from PcdhγB6 (Figures 4A (xi and xii) and S4G). When co-transfected with Pcdhα4, the PcdhγB6ΔEC1-4 mediates efficient membrane delivery of Pcdhα4 (Figure 4A (xv)). PcdhγB6ΔEC1-5 localizes to the cell surface when transfected alone (Figure 4A (xiv)), yet does not deliver Pcdhα4 to the cell surface (Figure 4A (xvi)). Similarly, Pcdhβ17ΔEC1-4 also mediates efficient membrane delivery of Pcdhα4 (Figure S4A). We conclude that the EC5 and EC6 domains of Pcdhβ or γ are necessary to deliver the Pcdhα isoform to the cell membrane.

Figure 4. The role of EC6 domains in membrane delivery.

(A) Mapping the minimum binding region of carrier Pcdhs. Cells expressing PcdhγB6 mutants alone (Upper panels) and with Pcdhα4 (Lower panels) were assayed for aggregation. Cell surface expression of Myc-tagged Pcdhα were shown (xv–xvi). (See also Figure S4G)

(B) Schematic representation of chimeric proteins and the results of homophilic binding assays are presented. All of the chimeras bearing the EC6 domain from PcdhγC3 (yellow) mediate cell aggregation. All of the chimeras bearing the EC6 domain of Pcdhα4 (red) fail to mediate cell aggregation. Scale bar, 50 µm. (See also Figure S4B and S4H).

(C) Cells expressing Pcdhα4 EC6/ICD domain deletion mutants are tested for aggregation (i–ii). Surface expression of Pcdhα constructs were shown on the right (iii–iv). (See also Figure S4I)

(D) Heat map of pairwise sequence identities for EC6 domains. The EC6 domain is highly conserved in alternate Pcdhβ and Pcdhγ isoforms, but the EC6 domains of alternate Pcdhα isoforms are less conserved.

(E) Multiple sequence alignment of EC6 domains of membrane-delivered Pcdhs (light gray) and non-membrane delivered Pcdhs (dark grey). Residues conserved within only one group are highlighted in blue and invariant residues in red.

White arrows indicate the c-Myc staining at cell-cell contacts in A and C. Scale bar, 50 µm.

To determine which Pcdh domains regulate membrane delivery we performed experiments in which domains were shuffled between Pcdhα4, which does not localize to the membrane (Figure 3A (i)), and PcdhγC3, which does (Figure 3A (x)). Constructs in which EC domains or the ICD of Pcdhα4 were replaced with the corresponding domains of PcdhγC3, or vice versa, were produced and tested for cell aggregation activity (Figure 4B and S4H), a proxy for membrane delivery. Chimeric constructs bearing the EC6 domain of PcdhγC3 mediate homophilic interactions (Figures 4B (i–iv, vii, xiv) and S4B (ii))) and are delivered to the cell surface (Figure S4B (iv)). By contrast, chimeric constructs that include the EC6 domain from Pcdhα4 showed no cell aggregation activity (Figures 4B (vi, ix–xiii, xv) and S4B (i)) due to the failure to localize to the plasma membrane (Figure S4B (iiii)). To address the possibility that the domain substitutions affect properties other than cell surface delivery, we co-transfected all Pcdhγ-Pcdhα chimera constructs containing the EC6 domain of Pcdhα4 (Figure S4C (i–vi)) with the carrier PcdhγB6ΔEC1. We found that these co-transfectants mediate homophilic interactions (Figure S4C (vii–xii)), demonstrating that the chimeric proteins are functional. Similar domain shuffling experiments were performed for other alternate Pcdhα isoforms (Figure S4D) and C type isoforms (Figures S4E and S4F). We conclude that the EC6 domain of alternate Pcdhα isoforms and of the PcdhγC4 isoform inhibit membrane delivery.

We next determined whether deletion of the EC6 domain in Pcdhα isoforms can rescue membrane delivery and homophilic binding. We found that Pcdhα4ΔEC6 is, in fact, efficiently delivered to the cell surface (Figure 4C (iii)) and mediates cell aggregation (Figures 4C (i) and S4I). These results, together with the domain swapping experiments (Figures 4B and S4D–S4F), show that the EC6 domain regulates Pcdh cell surface delivery but is not required for homophilic trans interactions.

Co-expression of multiple Pcdh isoforms generates new homophilic specificities

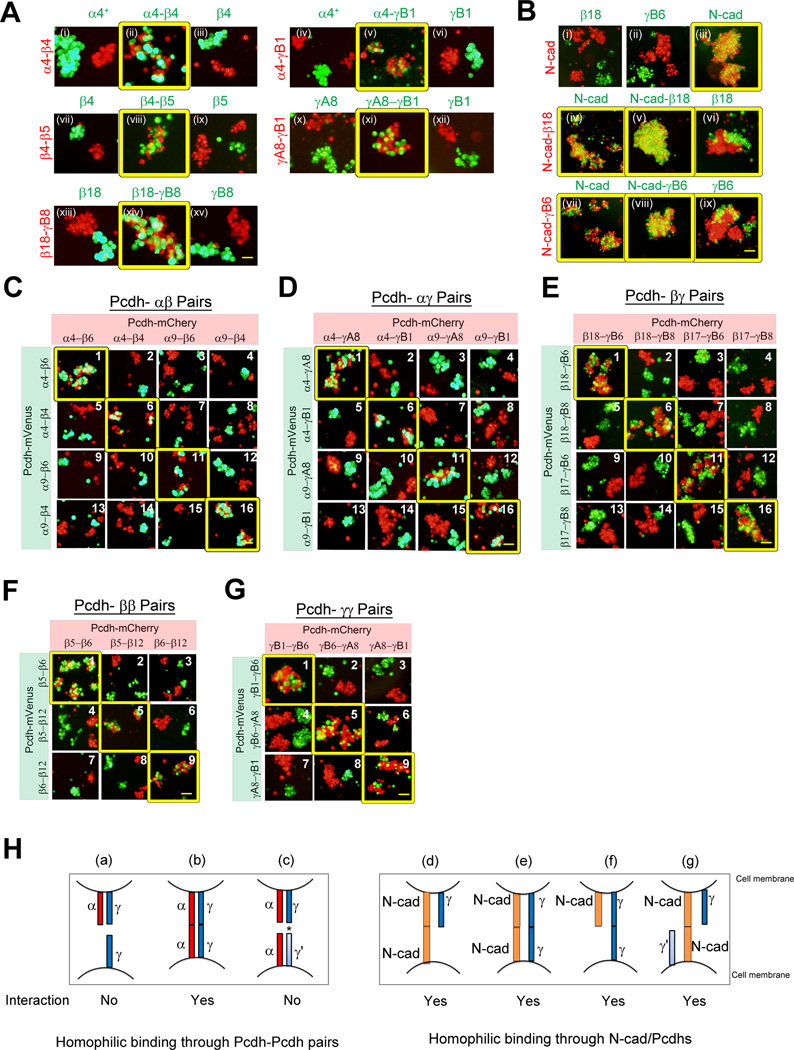

Previous studies suggested that multiple Pcdhγ isoforms form cis tetramers capable of mediating homophilic interactions (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010). Since all Pcdh-α, β and γ isoforms except PcdhαC1, mediate homophilic interactions (Figures 1D, 3B and S3D), and appear to associate with each other in cis (Figure S3B)(Han et al., 2010; Schalm et al., 2010), we tested the possibility that recognition specificity is diversified by co-expression of multiple Pcdh isoforms from all three subfamilies. Cells co-expressing Pcdhα4 and Pcdhβ4 were mixed with cells expressing both of these isoforms, or only one (Figure 5A (i–iii)). Cells expressing two distinct isoforms failed to co-aggregate with cells expressing either isoform alone. However, robust aggregation was observed with cells that co-express both isoforms. Similar results were observed for each of the Pcdh pairs shown in Figures 5A, S5A and S5C. These results suggest that the presence of one non-matching isoform can interfere with co-aggregation.

Figure 5. Co-expression of two distinct Pcdh isoforms generates a unique cell surface identity.

(A) Cells co-expressing two distinct mCherry-tagged Pcdh isoforms were assayed for interaction with cells expressing an mVenus-tagged Pcdh isoform or identical pairs. Pcdhα4+ is efficiently membrane-delivered and it possess the EC6 domain from PcdhγC3. (See also Figures S5A, S5C, S5G)

(B) Cells expressing mCherry-tagged N-cad were assayed for interaction with cells expressing single Pcdh isoform (Upper panels). Cells co-expressing pair of mCherry-tagged N-cad and Pcdh isoform were assayed for interaction with cells expressing an mVenus-tagged N-cad or Pcdh isoform (Middle and last panels). (See also Figures S5D, S5G, S6D, S6E and S6G)

(C–G) Cells co-expressing different combinations of differentially tagged Pcdh/Pcdh pairs were mixed and assayed for their interaction. (See also Figure S6B)

(H) Illustration of the outcome of cell-cell interaction dictated by combinatorial homophilic specificity of two distinct Pcdh isoforms (e.g a–c). Illustration of the outcome of cell-cell interaction dictated by cells co-expression N-cad and single Pcdh isoform (e.g d–g). This schematic diagram presented here does not reflect the cis-dimer and asterisk represents the non-matching Pcdhγ.

To test whether this type of interference is unique to Pcdhs, we carried out experiments similar to those reported in Figures 5A, but using cells co-transfected with N-cad and different Pcdhs. Figure 5B shows the results of aggregation assays with cells expressing various combinations of N-cad and Pcdhβ18 or PcdhγB6. Three types of aggregation behavior are observed. These three behaviors can be described as (1) formation of completely separate red and green aggregates, (2) complete intermixing between cell populations, and (3) formation of separate red and green aggregates that adhere to one another. Two of these aggregation phenotypes are seen in the top panels of Figure 5B, where red cells expressing N-cad form separate aggregates from green cells expressing any of the two Pcdhs (i and ii), but form a completely mixed aggregate with green cells expressing N-cad (iii). For these two cases, the different aggregation behaviors reflect the fact that N-cad does not bind to these Pcdhs, but binds strongly to itself. Figures 5B (iv–ix), S5D, S5F and S5G depicts the behavior of cells co-expressing N-cad and one Pcdh when they are allowed to mix with either N-cad or Pcdh expressors. In each case, these green cells form completely intermixed aggregates with red cells expressing N-cad alone, or with red cells expressing N-cad and the identical Pcdh or non-matching Pcdh, reflecting strong homophilic N-cad interactions with which Pcdhs do not interfere. The third type of aggregation behavior is observed when the red cells express both N-cad and a Pcdh isoform, and the green cells express only the identical Pcdh isoform (Figure 5B vi and ix). In this case, separate green and red homophilic aggregates are formed, but importantly they now adhere to one another. Similarly, all three types of behavior are observed for cells co-expressing N-cad and two Pcdhs (Figures S6D–E and S6G). The behavior of N-cad/Pcdh co-transfectants is strikingly different from that observed for Pcdh co-transfectants with mismatches, in which all homophilic aggregates remain completely separate.

These results strongly suggest that Pcdhs interact in cis so as to create new homophilic specificities that differ from the specificities of the individual Pcdh isoforms. In contrast, N-cad/Pcdh co-transfectants behave in a way that can be explained by a summation of the properties of the individual proteins, showing no evidence of cis interaction between them (Figure 5H). Thus, interference appears to be a property that is unique to Pcdhs. We note that co-IP experiments are consistent with cis interactions between Pcdhs, and with their absence between Pcdhs and N-cad (Figures S5E–S5G, and S6F).

To further characterize the Pcdh interference phenomenon, we assessed the ability of cells co-transfected with up to five Pcdh isoforms to co-aggregate with cells containing various numbers of mismatches (Figures 5C–G, 6A–C, S5B, S5G, S6A–C and S6F). In all cases, mixed aggregates were observed only for cells expressing identical isoforms whereas cells expressing mismatched isoforms formed separate non-adhering aggregates (Figure 5 and 6). Remarkably, even cells co-expressing distinct sets of four or five isoforms with even a single non-matching isoform resulted in the formation of large non-contacting homophilic aggregates with no contacts between them (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Combinatorial co-expression of multiple Pcdh isoforms generates unique cell surface identities.

(A–C) Cells co-expressing an identical or a distinct set Pcdh-α, –β, and –γ isoforms (A) and with C-type isoforms (B–C) were assayed for co-aggregation. Pcdhα4+ is efficiently membrane-delivered and it possess the EC6 domain from PcdhγC3. The non-matching isoforms between two cell populations were underlined. (See also Figure S6A–C and S6G)

(D) Illustration of the different behaviors of cell-cell interaction generated by combinatorial homophilic specificity of distinct sets of multiple Pcdh isoforms. (See also Figure S5G)

Discussion

The stochastic single-cell expression of clustered Pcdhs, the diversity of Pcdh extracellular domains, and the demonstration that the Pcdhg gene cluster is required for dendritic self-avoidance in starburst amacrine and Purkinjie cells support the hypothesis that the clustered Pcdhs provide single cell identity necessary for self-recognition in vertebrate nervous systems (Chen and Maniatis, 2013; Yagi, 2012; Zipursky and Grueber, 2013; Zipursky and Sanes, 2010). Here we provide evidence that different combinations of Pcdh α, β and γ isoforms interact in cis to generate combinatorial trans recognition specificities. The importance of Pcdh cis interactions is demonstrated by their role in delivering Pcdhα isoforms to the membrane. Below, we summarize evidence supporting these conclusions, we provide a theoretical analysis of Pcdh single cell diversity and we discuss the implications of this analysis on a prevailing model based on tetrameric cis recognition units (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010; Yagi, 2012). We conclude that, although recognition involving coupled cis and trans interactions (Wu et al., 2011; Wu et al., 2010) lies at the core of the mechanism through which Pcdhs establish single-cell identity, the nature of Pcdh recognition units and the mechanism of their interactions remains uncertain.

α, β, γ and C-type Pcdhs mediate specific homophilic recognition

We showed that Pcdh isoforms from all three gene clusters (α, β and γ) can mediate highly specific homophilic interactions (Figures 1D, 3B, S3D and S3F). Striking examples of this trans homophilic specificity are provided by the observation that Pcdh isoform pairs with as great as 91–97% identity in their EC2-EC3 recognition domains (α7-α8, β6-β8 and γA8-γA9) do not engage in heterophilic interactions (Figures 2C, 2D, and 3E). While PcdhαC1 does not interact homophilically in the aggregation assay (Figures 1D and S3F), a chimeric construct containing the PcdhαC1 EC1-EC3 domains can mediate homophilic interactions (Figure S4E (i)). Thus, it seems likely that the function of PcdhαC1 involves self-recognition, although the biological context is not yet understood. We note that, unlike the other Pcdhs, the calcium-binding motif DRE is not present in the EC3 domain of PcdhαC1 (Figure S1A). Rather, this motif is replaced by the sequence GPP, which is conserved in the PcdhαC1s in other species. We therefore speculate that the unique behavior of PcdhαC1 in the cell aggregation assay may result from differences in protein structure due to the absence of the calcium-binding motif, as, for example, in DN-cadherin (Jin et al., 2012).

Evidence for Pcdh cis interactions

Definitive evidence for cis interactions between distinct Pcdh isoforms is lacking. However, a number of experimental observations provide strong support for this possibility. First, we observe an altered recognition specificity when multiple Pcdh isoforms are expressed, a property thus far unique to Pcdhs. It is difficult to imagine how this could occur without cis interactions. Second, Pcdh β, γ and certain C-type isoforms deliver Pcdhα proteins to the cell surface in a process that requires membrane proximal domains (EC5 and EC6) of the carrier proteins, which are likely to be involved in cis interactions (Figure 4A). Third, distinct Pcdh-α, β and γ isoforms can be co-immunoprecipitated (Han et al., 2010; Murata et al., 2004; Schalm et al., 2010; Schreiner and Weiner, 2010) (Figures S3B and S6F). Fourth, multiple Pcdh isoforms are found in high molecular weight detergent-solubilized Pcdh complexes from the brain (Han et al., 2010).

Analysis of domain deletion and substitution experiments revealed a critical role of Pcdhα EC6 domains in the inhibition of cell surface delivery. Differential cell surface localization functions of EC6 domains may be reflected in amino acid sequence differences between them. The EC6 domains are the most highly conserved within the Pcdh -β and -γ subfamilies (Figures S2A and 4D), but differ from the EC6 domains of the Pcdhα isoforms (Figures 4D and 4E). The correspondence between membrane-delivery phenotypes and distinct EC6 sequence signatures suggests that the carrier function is a conserved property of clustered Pcdhs. The question of whether Pcdh cis complexes are stable on the cell surface, or can exchange cis partners in the plasma membrane remains to be determined. Reassortment of multimeric complexes on the cell surface would have obvious implications for Pcdh cell surface diversity and combinatorial specificity.

Combinatorial homophilic interactions between Pcdh α, β & γ isoforms

The key findings of cell aggregation assays can be interpreted in terms of the differential adhesion hypothesis (Foty and Steinberg, 2005) and the relationship between molecular binding affinities and the strength of cell-cell adhesion (Katsamba et al., 2009). Specifically, the aggregates we observe are likely the consequence of maximizing the number of favorable protein-protein interactions between cells. For example, cells expressing five Pcdh isoforms will prefer to form homophilic aggregates with cells expressing identical isoforms rather than to intermix with cells expressing only four of the five isoforms (Figure 6C). The cells expressing four Pcdh isoforms would similarly be expected to form homophilic aggregates with each other, in order to maximize the number of protein-protein interactions. However, one would also expect the two types of homophilic aggregates to adhere to one another, again to maximize favorable protein-protein contacts, as was observed in the experiments with N-cad and Pcdh(s) (Figures 5B, S6D, S6E and S6G). Remarkably, contact between aggregates expressing distinct Pcdh isoforms does not occur, suggesting a mechanism in which mismatched isoforms interfere with intercellular interactions. Indeed in all cases tested here (Figures 5 and 6), even a single Pcdh mismatch is sufficient to prevent the two types of homophilic aggregates from adhering to each another.

What is the maximum fraction of expressed isoforms that two cells can have in common before incorrectly recognizing each other as self? Our results suggest that at least in the cases examined, up to 80% (4/5) of the Pcdh common-isoforms can be shared between two cell populations without triggering co-aggregation (Figure 6C). In contrast, Schreiner and Weiner (2010) reported a graded recognition in which expression of 50% (1/2) and 75% (3/4) common-isoforms resulted in corresponding percentage of binding (~30–50% and ~70% respectively). These differences are likely to be due, at least in part, to different experimental approaches. Specifically, we used direct visualization to assess the specificity of cell-cell interactions and to determine which types of aggregates are formed (Figure S5G and S6G). In contrast, the previous report utilized an indirect colorimetric assay in which different types of aggregates could not be distinguished.

Theoretical analysis of Pcdh-mediated neuronal diversity

The prevailing model for generating neuronal diversity by Pcdhs involves the existence of discrete tetrameric recognition units formed by random combinations of Pcdh proteins that interact in cis (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010; Yagi, 2012). To consider this model in detail and to evaluate the implications of the high level of common-isoform tolerance identified in our study, we carried out an independent analysis of the factors that may contribute to Pcdh-mediated neuronal identity. Our analysis is based in part on earlier studies on Dscam1 by (Hattori et al., 2009) and by (Forbes et al., 2011), but focuses on the issue of isoform tolerance and introduces a factor not addressed previously; specifically how do neurites of the same neuron recognize that they are “the same”? We believe that the cis-tetramer model fails to answer this question. We begin with an analysis of isoform tolerance, which is key to understanding neuronal non-self discrimination.

For both Pcdhs and invertebrate Dscam1, the probability of errors in non-self discrimination depends on three parameters: the total number of potential isoforms, the number of distinct isoforms expressed per cell, and the tolerance for common isoforms between cells in contact (Hattori et al., 2009). Common-isoform tolerance is defined as the maximum percentage of common isoforms that can be present in two cells in contact without incorrect recognition as self. Based on this model (Hattori et al., 2009), if two cells have a higher fraction of common isoforms than the tolerance, they will inappropriately recognize each other as self. Hattori et al., (2009) assumed low tolerance for Dscam1 (10–20%), which is intuitively reasonable, since two cells expressing larger fractions of common isoforms would be expected to bind to one another. However to our knowledge, no experimental measure of tolerance has been reported for Dscam1. The results of the work presented here reveal much higher common-isoform tolerance levels for Pcdhs than assumed for Dscam1. This difference is likely the consequence of homophilic interactions between Pcdh cis multimers, in contrast to the Dscam1 isoforms which appear to interact as monomers. In the following section, we present an analysis of the inter-related effects of isoform diversity and isoform tolerance on non-self recognition. This in turn makes it possible to discuss Pcdhs and Dscam1 within a common framework.

Figure 7A shows the probabilities that two cells stochastically expressing different numbers of Pcdh isoforms will improperly recognize each other as self. Given the total number of possible isoforms, the number of isoforms expressed per cell (the x-axis in the figure), and a common-isoform tolerance, analytical expressions (Forbes, 2011) or Monte-Carlo simulations (Hattori et al., 2009) can be used to calculate these probabilities (See Supplemental Information). Results for Dscam1 were reported for a 5000-member isoform pool with a 15% tolerance (Hattori et al., 2009). In the case of Pcdhs, we made the conservative assumption of 67% tolerance (2/3 as observed in Figure 6A), and a 58-member isoform pool. Remarkably, even with a 67% common-isoform tolerance for clustered Pcdhs, the probabilities of incorrect recognition are as low as those for Dscam1 isoforms over much of the region that includes the expected number of isoforms (estimated at about 15 for Pcdhs and 10–50 for Dscam1) (Hattori et al., 2009; Yagi, 2012). These results suggest that a mechanism for achieving extremely high common-isoform tolerance is a key factor explaining how only 58 Pcdhs may be sufficient to mediate non-self discrimination in vertebrates.

Figure 7. Probabilistic analysis of Pcdh and Dscam1 recognition.

(A) Probabilities of incorrect non-self recognition between two cells as a function of the number of isoforms expressed per cell. Lines in the plot appear jagged due to the integer number of tolerated isoforms.

(B) Schematic representation of recognition units for different cis-multimeric states. Two cells share one common Pcdh isoform (blue) and one distinct isoform (red and yellow). Unique multimers are shown and the number of permutations for each multimer (e.g. ×2) are given.

(C) The relationships between common-isoforms and common-recognition units for different multimeric states. Vertical dotted lines mark the cases of 67% common Pcdh isoforms and show the corresponding percentage of common recognition units for monomers, dimers, trimers and tetramers. For the same percentage of common isoforms, larger multimers have a smaller percentage of common recognition unit.

(D) Monte-Carlo simulations were used to estimate the average number of copies of each multimer in a single cell. For the case of 15 Pcdh isoforms expressed per cell, the average number of copies of each multimeric recognition unit generated by the stochastic assembly of Pcdh isoforms into multimers is shown as a function of the number of copies of each isoform.

Combinatorial specificity of Pcdh interactions based on the assembly of multimeric cis Pcdh recognition units containing isoforms from all three gene clusters provides a possible mechanism to achieve the observed high level of tolerance. To illustrate this, we consider a model similar to that proposed for cis-tetramers (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010; Weiner et al., 2013; Yagi, 2012). We noted that the cis-tetramer model was based on a molecular weight estimate from size-exclusion chromatography (Schreiner and Weiner, 2010). However, the molecular weight of elongated proteins such as Pcdhs cannot be rigorously determined by this method, nor can it distinguish between cis and trans multimers. We therefore did not assume a specific multimeric state in our analysis.

A specific case where two cells each express one common and one different isoform and engage in cell-cell interactions through monomer, dimer, trimer or tetramer recognition units is illustrated in Figure 7B. As the multimer size increases, the fraction of common-recognition units decreases. This behavior is generalized in Figure 7C, which shows that at the same common-isoform tolerance, larger multimers will have a lower common-recognition unit tolerance, thus increasing cell surface diversity. For example, assuming tetrameric recognition units with 67% common isoforms (2/3) between two cells, only 20% of the recognition units will be shared, well within the range assumed for Dscam1 monomers (Hattori et al., 2009). This result highlights the essential feature of the tetramer model (Yagi, 2012). A tetrameric recognition unit implies that different neurons will have only a small fraction of recognition units in common even if they have a high fraction of common isoforms. In this way, mismatched isoforms will interfere with cell-cell recognition by diluting the number of common recognition units between two contacting cells (Yagi, 2013). However, this analysis did not consider the effect of dilution on self-recognition.

Randomly assembled tetrameric recognition units in which all Pcdh isoforms form multimers with equal probability cannot explain how two neurites from the same cell body are able to recognize each other as self. The point can be easily seen by calculating the average number of copies of each multimeric recognition unit per cell as a function of the number of copies of each Pcdh isoform in a cell. Figure 7D reports these numbers for the case of 15 different isoforms expressed per cell. A striking conclusion is that, for tetramers, there would be an unacceptably small number of copies of each recognition unit per neuron. For example, assuming that there are 5,000 copies each of 15 distinct Pcdh isoforms in an individual cell (75,000 Pcdhs total - in the range estimated for cells overexpressing classical cadherins (Duguay et al., 2003)), 12,720 unique tetramers could form (Yagi, 2012) and there would thus be fewer than two copies (approximately 75,000/(12,720*4)=1.4) of each unique recognition unit per neuron. This number is clearly insufficient for self-recognition by neurons with many neurites. This self-recognition problem is reduced but not eliminated for trimeric and dimeric recognition units (Figure 7D).

These considerations bring into question the validity of the tetramer model in which all isoforms have equal probability of participation. This would be less of a problem if only certain combinations of Pcdh isoforms could assemble into multimers. For example, our data indicates that Pcdhα isoforms may form obligate complexes with Pcdh-β or –γ isoforms, or with constitutively expressed C-type isoforms to function on the cell surface. The obligate assembly could also determine the nature of the multimeric complexes. Another possibility is that like classical cadherins (Harrison et al., 2011), Pcdhs could form junction-like structures involving cis and trans interactions, which require a minimal percentage of matched isoforms to mediate stable adhesion. With such a mechanism, an excess of mismatched isoforms in contacting cells would reduce the number of favorable interactions so as to prevent junction formation.

We conclude that specific models of Pcdh combinatorial homophilic interactions cannot be rigorously supported at the present time. Neither the physical properties of the proposed multimeric complexes nor the mechanism of their interactions can be discerned on the basis of the currently available data. Nevertheless, it seems highly likely that the clustered Pcdhs play a fundamental role in intercellular recognition in the vertebrate nervous system based on the extraordinary diversity of their single cell expression, and the highly specific homophilic interactions between individual as well as combinations of all three families of clustered Pcdh isoforms as shown here. Most remarkable in this regard is interference in the interactions between cells each expressing five distinct Pcdh isoforms only one of which differs in the two cell populations. Based on these observations, and the demonstrated role of the Pcdhs in dendritic self-avoidance, these cell surface proteins clearly play a role in the establishment and maintenance of complex neural circuits in the brain.

Experimental procedures

Plasmid construction

Coding sequence of each clustered Pcdh isoform was PCR amplified from C57BL/6 genomic DNA or brain cDNA, cloned into modified Gateway vectors to generate C-terminal mCherry- or mVenus-tagged Pcdh proteins. Domain deletions, substitutions, or insertion of an extracellular c-Myc tag were created by overlapping PCR. See Extended Experimental Procedures for details.

Cell aggregation assay

Expression constructs were transfected into K562 cells (human leukemia cell line, ATCC CCL243) by electroporation using Amaxa 4D-Nucleofactor (Lonza). After 24 hours in culture, the transfected cells were allowed to aggregate for one to three hours on a rocker kept inside the incubator. The cells were then fixed in 4% PFA for 10 minutes, washed in PBS, and cleared with 50% glycerol for imaging. Quantification of the sizes of cell aggregates was described in Extended Experimental Procedures.

Immunostaining

K562 cells were transfected as described above. After 24 hours, FITC-conjugated anti-c-Myc antibodies were added to the cells and then incubated with shaking for one hour. Cells were then fixed with 4% PFA and washed in PBS. Fixed single cells or aggregates were collected on glass coverslips by using a cell concentrator (StatSpin) at 1000 rpm for 10 minutes. Images were collected with an Olympus Fluoview FV1000 confocal microscope.

Binding specificity assay for cells expressing single or multiple Pcdh isoform(s)

Differentially tagged Pcdh isoforms were transfected into K562 cells as described above. Transfected cell populations expressing mCherry- or mVenus-tagged Pcdh(s) were mixed after 24 hours by shaking for one to three hours. Images of cell aggregates were imported into ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij), and the number of aggregates containing red cells only (R), green cells only (G), and both red and green cells (RG) were counted for analysis of binding specificity. See Extended Experimental Procedure for details.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Pcdh–α,-β and -γ isoforms mediate specific homophilic interactions

EC6 domains of Pcdhα and PcdhγC4 isoforms inhibit cell surface delivery

Homophilic specificity of co-expressed Pcdh isoforms provides single cell identity

Conflicting requirements of self-recognition and non-self discrimination

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Richard Axel, Charles Zuker, Wesley Grueber and Hemali Phatnani for critical reading of the manuscript, and valuable comments. We also thank Lin Jin and Angelica Struve for technical assistance and members of the Maniatis, Shapiro, and Honig labs for discussion and comments. We thank Drs. Joshua Sanes, Julie Lefebvre, Stefanie S. Schalm and Steven Vogel for providing reagents and plasmids. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grant to T.M. (2R56NS043915-33A1), joint NIH grant to T.M. and L.S. (1R01GM107571-01), National Science Foundation grant to B.H (MCB-0918535), and NIH Training Programs to H.W. (T32GM008281) and K.F. (T32GM082797).

Footnotes

Supplemental information

Supplemental information includes Extended Experimental Procedures, seven supplementary figures and spreadsheet for raw data.

Author contributions

C.A.T. designed and performed experiments. W.V.C. co-initiated the study, and contributed to the design and establishment of experimental approaches. R.R. led the computational and statistical analysis. K.F predicted the EC domain alignment. M.C. provided technical support. J.C.T. contributed to image analysis. C.A.T., W.V.C., R.R., H.W.,L.S.,B.H.,T.M analyzed the data and wrote the paper.

References

- Bonn S, Seeburg PH, Schwarz MK. Combinatorial expression of alpha- and gamma-protocadherins alters their presenilin-dependent processing. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:4121–4132. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01708-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen WV, Maniatis T. Clustered protocadherins. Development. 2013;140:3297–3302. doi: 10.1242/dev.090621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duguay D, Foty RA, Steinberg MS. Cadherin-mediated cell adhesion and tissue segregation: qualitative and quantitative determinants. Dev Biol. 2003;253:309–323. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00016-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esumi S, Kakazu N, Taguchi Y, Hirayama T, Sasaki A, Hirabayashi T, Koide T, Kitsukawa T, Hamada S, Yagi T. Monoallelic yet combinatorial expression of variable exons of the protocadherin-alpha gene cluster in single neurons. Nat Genet. 2005;37:171–176. doi: 10.1038/ng1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes EM, Hunt JJ, Goodhill GJ. The combinatorics of neurite self-avoidance. Neural computation. 2011;23:2746–2769. doi: 10.1162/NECO_a_00186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foty RA, Steinberg MS. The differential adhesion hypothesis: a direct evaluation. Dev Biol. 2005;278:255–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han MH, Lin C, Meng S, Wang X. Proteomics analysis reveals overlapping functions of clustered protocadherins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:71–83. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900343-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison OJ, Jin X, Hong S, Bahna F, Ahlsen G, Brasch J, Wu Y, Vendome J, Felsovalyi K, Hampton CM, et al. The extracellular architecture of adherens junctions revealed by crystal structures of type I cadherins. Structure. 2011;19:244–256. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori D, Chen Y, Matthews BJ, Salwinski L, Sabatti C, Grueber WB, Zipursky SL. Robust discrimination between self and non-self neurites requires thousands of Dscam1 isoforms. Nature. 2009;461:644–648. doi: 10.1038/nature08431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori D, Millard SS, Wojtowicz WM, Zipursky SL. Dscam-mediated cell recognition regulates neural circuit formation. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2008;24:597–620. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.24.110707.175250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K, Kaneko R, Izawa T, Kawaguchi M, Kitsukawa T, Yagi T. Single-neuron diversity generated by Protocadherin-beta cluster in mouse central and peripheral nervous systems. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:90. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin XS, Walker MA, Felsovalyi K, Vendome J, Bahna F, Mannepalli S, Cosmanescu F, Ahlsen G, Honig B, Shapiro L. Crystal structures of Drosophila N-cadherin ectodomain regions reveal a widely used class of Ca2+-free interdomain linkers. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E127–E134. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117538108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko R, Kato H, Kawamura Y, Esumi S, Hirayama T, Hirabayashi T, Yagi T. Allelic gene regulation of Pcdh-alpha and Pcdh-gamma clusters involving both monoallelic and biallelic expression in single Purkinje cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:30551–30560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605677200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katsamba P, Carroll K, Ahlsen G, Bahna F, Vendome J, Posy S, Rajebhosale M, Price S, Jessell TM, Ben-Shaul A, et al. Linking molecular affinity and cellular specificity in cadherin-mediated adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:11594–11599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905349106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre JL, Kostadinov D, Chen WV, Maniatis T, Sanes JR. Protocadherins mediate dendritic self-avoidance in the mammalian nervous system. Nature. 2012;488:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature11305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura SK, Martins A, Zhang KX, Graveley BR, Zipursky SL. Probabilistic splicing of dscam1 establishes identity at the level of single neurons. Cell. 2013;155:1166–1177. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murata Y, Hamada S, Morishita H, Mutoh T, Yagi T. Interaction with protocadherin-gamma regulates the cell surface expression of protocadherin-alpha. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49508–49516. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M408771200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves G, Zucker J, Daly M, Chess A. Stochastic yet biased expression of multiple Dscam splice variants by individual cells. Nat Genet. 2004;36:240–246. doi: 10.1038/ng1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reiss K, Maretzky T, Haas IG, Schulte M, Ludwig A, Frank M, Saftig P. Regulated ADAM10-dependent ectodomain shedding of gamma-protocadherin C3 modulates cell-cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:21735–21744. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602663200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribich S, Tasic B, Maniatis T. Identification of long-range regulatory elements in the protocadherin-alpha gene cluster. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19719–19724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609445104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schalm SS, Ballif BA, Buchanan SM, Phillips GR, Maniatis T. Phosphorylation of protocadherin proteins by the receptor tyrosine kinase Ret. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:13894–13899. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1007182107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker D, Chen B. Dscam and DSCAM: complex genes in simple animals, complex animals yet simple genes. Genes Dev. 2009;23:147–156. doi: 10.1101/gad.1752909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmucker D, Clemens JC, Shu H, Worby CA, Xiao J, Muda M, Dixon JE, Zipursky SL. Drosophila Dscam is an axon guidance receptor exhibiting extraordinary molecular diversity. Cell. 2000;101:671–684. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80878-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiner D, Weiner JA. Combinatorial homophilic interaction between gamma-protocadherin multimers greatly expands the molecular diversity of cell adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14893–14898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004526107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun W, You X, Gogol-Doring A, He H, Kise Y, Sohn M, Chen T, Klebes A, Schmucker D, Chen W. Ultra-deep profiling of alternatively spliced Drosophila Dscam isoforms by circularization-assisted multi-segment sequencing. EMBO J. 2013;32:2029–2038. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasic B, Nabholz CE, Baldwin KK, Kim Y, Rueckert EH, Ribich SA, Cramer P, Wu Q, Axel R, Maniatis T. Promoter choice determines splice site selection in protocadherin alpha and gamma pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2002;10:21–33. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00578-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Su H, Bradley A. Molecular mechanisms governing Pcdh-gamma gene expression: evidence for a multiple promoter and cis-alternative splicing model. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1890–1905. doi: 10.1101/gad.1004802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JA, Jontes JD, Burgess RW. Introduction to mechanisms of neural circuit formation. Front Mol Neurosci. 2013;6:12. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2013.00012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz WM, Flanagan JJ, Millard SS, Zipursky SL, Clemens JC. Alternative splicing of Drosophila Dscam generates axon guidance receptors that exhibit isoform-specific homophilic binding. Cell. 2004;118:619–633. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wojtowicz WM, Wu W, Andre I, Qian B, Baker D, Zipursky SL. A vast repertoire of Dscam binding specificities arises from modular interactions of variable Ig domains. Cell. 2007;130:1134–1145. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q. Comparative genomics and diversifying selection of the clustered vertebrate protocadherin genes. Genetics. 2005;169:2179–2188. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.037606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Maniatis T. A striking organization of a large family of human neural cadherin-like cell adhesion genes. Cell. 1999;97:779–790. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80789-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Q, Zhang T, Cheng JF, Kim Y, Grimwood J, Schmutz J, Dickson M, Noonan JP, Zhang MQ, Myers RM, et al. Comparative DNA sequence analysis of mouse and human protocadherin gene clusters. Genome Res. 2001;11:389–404. doi: 10.1101/gr.167301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Vendome J, Shapiro L, Ben-Shaul A, Honig B. Transforming binding affinities from three dimensions to two with application to cadherin clustering. Nature. 2011;475:510–513. doi: 10.1038/nature10183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu YH, Jin XS, Harrison O, Shapiro L, Honig BH, Ben-Shaul A. Cooperativity between trans and cis interactions in cadherin-mediated junction formation. P Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:17592–17597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011247107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi T. Molecular codes for neuronal individuality and cell assembly in the brain. Front Mol Neurosci. 2012;5:45. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2012.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi T. Genetic basis of neuronal individuality in the mammalian brain. Journal of neurogenetics. 2013;27:97–105. doi: 10.3109/01677063.2013.801969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhan XL, Clemens JC, Neves G, Hattori D, Flanagan JJ, Hummel T, Vasconcelos ML, Chess A, Zipursky SL. Analysis of Dscam diversity in regulating axon guidance in Drosophila mushroom bodies. Neuron. 2004;43:673–686. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipursky SL, Grueber WB. The molecular basis of self-avoidance. Annual review of neuroscience. 2013;36:547–568. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-062111-150414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zipursky SL, Sanes JR. Chemoaffinity revisited: dscams, protocadherins, and neural circuit assembly. Cell. 2010;143:343–353. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.