Abstract

Human brain anatomy and function display a combination of modular and hierarchical organization, suggesting the importance of both cohesive structures and variable resolutions in the facilitation of healthy cognitive processes. However, tools to simultaneously probe these features of brain architecture require further development. We propose and apply a set of methods to extract cohesive structures in network representations of brain connectivity using multi-resolution techniques. We employ a combination of soft thresholding, windowed thresholding, and resolution in community detection, that enable us to identify and isolate structures associated with different weights. One such mesoscale structure is bipartivity, which quantifies the extent to which the brain is divided into two partitions with high connectivity between partitions and low connectivity within partitions. A second, complementary mesoscale structure is modularity, which quantifies the extent to which the brain is divided into multiple communities with strong connectivity within each community and weak connectivity between communities. Our methods lead to multi-resolution curves of these network diagnostics over a range of spatial, geometric, and structural scales. For statistical comparison, we contrast our results with those obtained for several benchmark null models. Our work demonstrates that multi-resolution diagnostic curves capture complex organizational profiles in weighted graphs. We apply these methods to the identification of resolution-specific characteristics of healthy weighted graph architecture and altered connectivity profiles in psychiatric disease.

Author Summary

The human brain is a fascinating organ full of exquisite anatomical and functional detail. A striking feature of this detail lies in the presence of small modules nested within one another across hierarchical levels of organization. Here we develop and apply computational analysis tools to probe these features of brain architecture by examining network representations in which brain areas are treated as network nodes and links between areas are treated as network edges. The class of methods that we describe are referred to as “multi-resolution techniques” and enable us to identify and isolate neural structures associated with different edge properties. Our methods lead to multi-resolution curves of these network diagnostics over a range of spatial, geometric, and structural scales. For statistical comparison, we contrast our results with those obtained for several benchmark null models. Our work demonstrates that multi-resolution diagnostic curves capture complex organizational profiles in weighted graphs. We apply these methods to the identification of resolution-specific characteristics of healthy weighted graph architecture and altered connectivity profiles in psychiatric disease.

Introduction

Noninvasive neuroimaging techniques provide quantitative measurements of structural and functional connectivity in the human brain. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) indirectly resolves time dependent neural activity by measuring the blood-oxygen-level-dependent (BOLD) signal while the subject is at rest or performing a cognitive task. Diffusion weighted imaging (DWI) techniques use MRI to map the diffusion of water molecules along white matter tracts in the brain, from which anatomical connections between brain regions can be inferred. In each case, measurements can be represented as a weighted network [1], [2], [3], [4], [5], [6], [7], in which nodes correspond to brain regions, and the weighted connection strength between two nodes can, for example, represent correlated activity (fMRI) or fiber density (DWI). The resulting network is complex, and richly structured, with weights that exhibit a broad range of values, reflecting a continuous spectrum from weak to strong connections.

The network representation of human brain connectivity facilitates quantitative and statistically stringent investigations of human cognitive function, aging and development, and injury or disease. Target applications of these measurements include disease diagnosis, monitoring of disease progression, and prediction of treatment outcomes [8], [9], [10], [11], [12]. However, efforts to develop robust methods to reduce these large and complex neuroimaging data sets to statistical diagnostics that differentiate between patient populations have been stymied by the dearth of methods to quantify the statistical significance of apparent group differences in network organization [13], [14], [15], [16].

Network comparisons can be performed in several ways. In one approach, network comparisons are made after applying a threshold to weighted structural and functional connectivity matrices to fix the number of edges at a constant value in all individuals [4], [13]. Edges with weights passing the threshold are set to a value of  while all others are set to a value of

while all others are set to a value of  (a process referred to as ‘binarizing’). In some cases results are tested for robustness across multiple thresholds, although this increases the probability of Type I (false positive) errors from multiple non-independent comparisons. More generally, this procedure disregards potentially important neurobiological information present in the original edge weights. A second approach involves examination of network geometry in the original weighted matrices without binarizing. However, because the values of weighted metrics can be influenced by both the average weight of the matrix and the distribution of weights, this approach presents peculiar complications for the assessment of group differences [14], [15]. Critically, neither of these two approaches for network comparison allow for a principled examination of network structure as a function of weight (strong versus weak connections) or space (short versus long connections). Disease-related group differences in network architecture that are present only at a particular edge weight range or at a specific spatial resolution can therefore remain hidden.

(a process referred to as ‘binarizing’). In some cases results are tested for robustness across multiple thresholds, although this increases the probability of Type I (false positive) errors from multiple non-independent comparisons. More generally, this procedure disregards potentially important neurobiological information present in the original edge weights. A second approach involves examination of network geometry in the original weighted matrices without binarizing. However, because the values of weighted metrics can be influenced by both the average weight of the matrix and the distribution of weights, this approach presents peculiar complications for the assessment of group differences [14], [15]. Critically, neither of these two approaches for network comparison allow for a principled examination of network structure as a function of weight (strong versus weak connections) or space (short versus long connections). Disease-related group differences in network architecture that are present only at a particular edge weight range or at a specific spatial resolution can therefore remain hidden.

In this paper, we employ several techniques to examine the multi-resolution structure of weighted connectivity matrices: soft thresholding, windowed thresholding, and modularity resolution. A summary of these techniques is presented in Table 1, and each method is discussed in more detail in the Methods section. We apply these techniques to two previously published data sets: structural networks extracted from diffusion tractography data in five healthy human subjects [17] and functional networks extracted from resting state fMRI data in people with schizophrenia and healthy controls (N = 58) [15]. As benchmark comparisons, we also explore a set of synthetic networks that includes a random Erdős-Rényi network (ER), a ring lattice (RL), a small-world network (SW), and a fractal hierarchical network (FH).

Table 1. Summary of multi-resolution methods for network diagnostics.

| Technique | Method Summary | Control Parameter | Strengths and Limitations | Refs. |

| Soft Threhsolding | Raise each entry in  to the power r: to the power r:

|

r: power applied to entries in  . Small r limit weights all connections equally. Large r limit amplifies strong connections, relative to weak. . Small r limit weights all connections equally. Large r limit amplifies strong connections, relative to weak. |

Enables continuous variation of the contribution of edges of different weights. Strong edges may dominate, but all connections retained. | [49], [50] |

| Windowed Thresholding | Construct binarized network a fixed percentage of connections corresponding to a range of edge weights |

: average edge weight of connections within the window. Small : average edge weight of connections within the window. Small  isolates weak connections. Large isolates weak connections. Large  isolates strong connections. isolates strong connections. |

Enables an isolated view of structure at different edge weights. Weak connections are not obscured by strong connections, but relationships between strong and weak connections are ignored. | [15], [49] |

| Modularity Resolution | Structural resolution tuned in community detection. Sets a tolerance on the partition into modules relative to a null model. |

: appears in the quality function : appears in the quality function  or or  optimized when dividing nodes into partitions. Small optimized when dividing nodes into partitions. Small  yields one large community. Large yields one large community. Large  yields many small communities. yields many small communities. |

Enables a continuous variation in the resolution of community structure. This method has the most direct, tunable control of the output, but does not generalize to diagnostics other than those associated with modularity. | [51] |

We use soft thresholding, windowed thresholding, and variation in the resolution parameter of modularity maximization to probe network architecture across scales (Column 1). For each approach, we provide a method summary (Column 2), a description of the control parameter (Column 3), a brief synopsis of the strengths and limitations of the approach (Column 4), and a few relevant references (Column 5).

While multi-resolution techniques could be usefully applied to a broad range of network diagnostics, here we focus on two complementary mesoscale characteristics that can be used to probe the manner in which groups of brain regions are connected with one another: modularity and bipartivity. Modularity quantifies community structure in a network by identifying groups of brain regions that are more strongly connected to other regions in their group than to regions in other groups [18], [19]. Communities of different sizes, nested within one another, have been identified in both structural and functional brain networks [20], [21], [22], [23], [24] and are thought to constrain information processing [25], [26], [27]. Bipartivity quantifies bipartite structure in a network by separating brain regions into two groups with sparse connectivity within each group and dense connectivity between the two groups. The dichotomous nature of bipartitivity is particularly interesting to quantify in systems with bilateral symmetry such as the human brain, in which inter- and intra-hemispheric connectivity display differential structural [28] and functional [29] network properties.

We describe these techniques, diagnostics, and null models in detail in the Methods section and illustrate their utility in addressing questions in systems and clinical neuroscience in the Results section.

Methods

This section has three major components: (1) a description of the empirical data examined in this study as well as the simpler synthetic networks employed to illustrate our techniques in well-characterized, controlled settings, (2) a summary of the graph diagnostics used in our analysis to examine properties of mesoscale network architecture, and (3) definitions of the soft thresholding, windowed thresholding, and modularity resolution techniques which provide a means to resolve network structure at different connection strengths.

Empirical and Synthetic Benchmark Networks

We examine two separate neuroimaging data sets acquired noninvasively from humans. The first is a set of  structural networks constructed from diffusion spectrum imaging (DSI) data (taken from 5 subjects; one subject was scanned twice) and the second is a set of

structural networks constructed from diffusion spectrum imaging (DSI) data (taken from 5 subjects; one subject was scanned twice) and the second is a set of  functional networks constructed from resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data. For comparison, we generate 4 types of synthetic network models that range from an Erdős-Rényi random graph to models that include more complex structure, including hierarchy and clustering.

functional networks constructed from resting state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) data. For comparison, we generate 4 types of synthetic network models that range from an Erdős-Rényi random graph to models that include more complex structure, including hierarchy and clustering.

Each network is described by an adjacency matrix  whose

whose  entry describes the weight of the edge connecting nodes

entry describes the weight of the edge connecting nodes  and

and  . For the empirical brain networks, the edge weights are determined by neuroimaging measurements. For the synthetic networks, we construct weights to mimic the structural organization of the network, as described below.

. For the empirical brain networks, the edge weights are determined by neuroimaging measurements. For the synthetic networks, we construct weights to mimic the structural organization of the network, as described below.

Empirical brain networks: Data acquisition and preprocessing

Because our focus in this paper lies in method development and illustration, we have chosen to utilize two previously published empirical brain network data sets. These data sets were chosen to represent the two neuroimaging techniques most commonly utilized for analysis of brain network architecture: diffusion imaging which captures anatomical structure, and fMRI which captures brain function. For our diffusion data set, we chose the DSI data from the seminal contribution of Hagmann et al. 2008 in PLoS Biol [17]. For our fMRI data set, we chose a resting state data set acquired from both healthy controls and a patient population to enable the comparison of multiresolution structure in two sets of networks, thereby illustrating the utility of these techniques in the context of clinical questions [15]. In both data sets, we utilized the brain networks extracted and examined in these two papers [17], [15], enabling a direct comparison between the utility of multiresolution techniques and previously published single resolution techniques.

Structural networks:. We construct an adjacency matrix  whose

whose  entries are the probabilities of fiber tracts linking region

entries are the probabilities of fiber tracts linking region  with region

with region  as determined by an altered path integration method. The resultant adjacency matrix

as determined by an altered path integration method. The resultant adjacency matrix  contains entries

contains entries  that represent connection weights between the 998 regions of interest extracted from the whole brain. We also define the distance matrix

that represent connection weights between the 998 regions of interest extracted from the whole brain. We also define the distance matrix  to contain entries

to contain entries  that are the average curvilinear distance traveled by fiber tracts that link region

that are the average curvilinear distance traveled by fiber tracts that link region  with region

with region  , or the Euclidean distance between region

, or the Euclidean distance between region  and

and  , where no data of the arc length was available. We define separate

, where no data of the arc length was available. We define separate  and

and  adjacency matrices for each of 5 healthy adults with 1 adult scanned twice (treated as 6 separate scans throughout the paper). For further details, see [17].

adjacency matrices for each of 5 healthy adults with 1 adult scanned twice (treated as 6 separate scans throughout the paper). For further details, see [17].

Functional networks: We construct an adjacency matrix  whose

whose  entry is given by the absolute value of the Pearson correlation coefficient between the resting state wavelet scale 2 (0.06–0.12 Hz) blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) time series from region

entry is given by the absolute value of the Pearson correlation coefficient between the resting state wavelet scale 2 (0.06–0.12 Hz) blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) time series from region  and from region

and from region  . The resultant adjacency matrix

. The resultant adjacency matrix  contains entries

contains entries  that represent functional connection weights between 90 cortical and subcortical regions of interest extracted from the whole brain automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas [30].

that represent functional connection weights between 90 cortical and subcortical regions of interest extracted from the whole brain automated anatomical labeling (AAL) atlas [30].

We define separate adjacency matrices for each of 29 participants with chronic schizophrenia (11 females; age 41.3  9.3 (SD)) and 29 healthy participants (11 females; age 41.1

9.3 (SD)) and 29 healthy participants (11 females; age 41.1  10.6 (SD)) (see [31] for detailed characteristics of participants and imaging data). We note that the two groups had similar mean RMS motion parameters (two-sample t-tests of mean RMS translational and angular movement were not significant at

10.6 (SD)) (see [31] for detailed characteristics of participants and imaging data). We note that the two groups had similar mean RMS motion parameters (two-sample t-tests of mean RMS translational and angular movement were not significant at  and

and  , respectively), suggesting that identified group difference in network properties could not be attributed to differences in movement during scanning.

, respectively), suggesting that identified group difference in network properties could not be attributed to differences in movement during scanning.

Synthetic benchmark networks

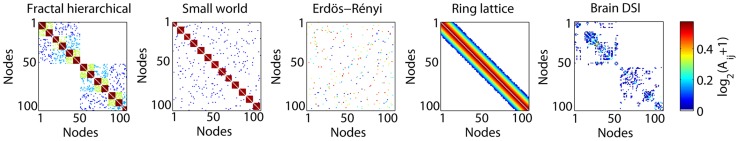

In addition to empirical networks, we also examine 4 synthetic model networks to illustrate our techniques in well-characterized, controlled settings: an Erdös-Rényi random network, a ring-lattice, a small world network, and a fractal hierarchical network (see Fig. 9). These four network models provide simple benchmark comparisons for the empirical data but cannot be interpreted as biological models of the empirical data. Indeed, the question of which graphical models produce networks most similar to empirical data is a matter of ongoing investigation [28]. All networks were created using modified code from [32].

Figure 9. Weighted connection matrices for the synthetic benchmark networks and an empirical brain DSI network (N = 1000 nodes).

Because network topologies can be difficult to decipher in large networks, here we illustrate the connections between only 100 of the total 1000 nodes. In each network, the topology changes as a function of edge weight (i.e., color) in the adjacency matrix. The windowed thresholding technique isolates topological characteristics in the subnetworks of nodes of similar weight. We report the initial benchmark results for a window size of 25% but find that results from other window sizes are qualitatively similar (see the Supporting Information).

The Erdös-Rényi and the ring-lattice networks are important benchmark models used in a range of contexts across a variety of network systems. Small world and fractal hierarchical networks incorporate clustering and layered structure, reminiscent of properties associated with brain networks [33]. We emphasize that the synthetic models are not intended to be realistic models of the brain. Rather, we use them to isolate structural drivers of network topology and to illustrate the utility of multi-resolution approaches [34] in a controlled setting.

Most synthetic network models, including all those that we study in this paper were originally developed as binary graphs (i.e. all edge weights equal to either  or

or  ). Since we are specifically interested in the effect of edge weights on network properties, we consider weighted generalizations of these models, in which the weights of edges are chosen to maintain essential structural properties of the underlying graph (see Figure 9). For example, in network models that display hierarchical structure, edge weights differ across the hierarchical levels but remain constant within a hierarchical level, while in network models with both short and long distance topological connections, edge weights correspond to the topological distance of connections (see below for additional details). Importantly, all of these networks therefore maintain the same number of nodes and edges as the empirical data, but differ in terms of their average weight, degree distribution, and strength distribution as expected mathematically from the differences in their geometry (i.e., weighted network structure).

). Since we are specifically interested in the effect of edge weights on network properties, we consider weighted generalizations of these models, in which the weights of edges are chosen to maintain essential structural properties of the underlying graph (see Figure 9). For example, in network models that display hierarchical structure, edge weights differ across the hierarchical levels but remain constant within a hierarchical level, while in network models with both short and long distance topological connections, edge weights correspond to the topological distance of connections (see below for additional details). Importantly, all of these networks therefore maintain the same number of nodes and edges as the empirical data, but differ in terms of their average weight, degree distribution, and strength distribution as expected mathematically from the differences in their geometry (i.e., weighted network structure).

Erdös-Rényi Random (ER) model: The Erdös-Rényi random graph serves as an important benchmark null model against which to compare other empirical and synthetic networks. The graph  is constructed by assigning a fixed number of connections

is constructed by assigning a fixed number of connections  between the

between the  nodes of the network. The edges are chosen uniformly at random from all possible edges, and we assign them weights drawn from a uniform distribution in

nodes of the network. The edges are chosen uniformly at random from all possible edges, and we assign them weights drawn from a uniform distribution in  .

.

Ring-Lattice (RL) model: The one-dimensional ring-lattice model can be constructed for a given number of edges  and number of nodes

and number of nodes  by first placing edges between nodes separated by a single edge, then between pairs of nodes separated by

by first placing edges between nodes separated by a single edge, then between pairs of nodes separated by  edges and so on, until all

edges and so on, until all  connections have been assigned. To construct a geometric (i.e. weighted) chain-like structure, we assign the weights of each edge to mimic the topological structure of the binary chain lattice. Edge weights decreased linearly from

connections have been assigned. To construct a geometric (i.e. weighted) chain-like structure, we assign the weights of each edge to mimic the topological structure of the binary chain lattice. Edge weights decreased linearly from  to

to  with increasing topological distance between node pairs.

with increasing topological distance between node pairs.

Small World (SW) model: Networks with high clustering and short path lengths are often referred to as displaying “small world” characteristics [35], [36]. Here we construct a modular small world model [33] by connecting  nodes in elementary groups of fully connected clusters of

nodes in elementary groups of fully connected clusters of  nodes, where

nodes, where  and

and  are integers. If the number of edges in this model is less than

are integers. If the number of edges in this model is less than  , the remaining edges are placed uniformly at random throughout the network. The edges in this model are either intra-modular (placed within elementary groups) or inter-modular (placed between elementary groups). To construct a geometrical modular small world model, we assigned different weights to the two types of edges:

, the remaining edges are placed uniformly at random throughout the network. The edges in this model are either intra-modular (placed within elementary groups) or inter-modular (placed between elementary groups). To construct a geometrical modular small world model, we assigned different weights to the two types of edges:  for intra-modular edges and

for intra-modular edges and  for inter-modular edges.

for inter-modular edges.

To ensure our comparisons are not dominated by the overall network density, we construct synthetic network models with  nodes and

nodes and  edges to match the empirical data [13]. For modular small world networks, this stipulation requires that we modify the algorithm above to produce networks in which the number of nodes is not necessarily an exact power of two. For comparisons to the structural (functional) brain data, we generate a model as described above with

edges to match the empirical data [13]. For modular small world networks, this stipulation requires that we modify the algorithm above to produce networks in which the number of nodes is not necessarily an exact power of two. For comparisons to the structural (functional) brain data, we generate a model as described above with  (

( ) and then chose

) and then chose  (

( ) nodes at random, which are deleted along with their corresponding edges.

) nodes at random, which are deleted along with their corresponding edges.

Fractal Hierarchical (FH) model: Network structure in the brain displays a hierarchically modular organization [20], [21], [22], [23], [24] thought generally to constrain information processing phenomena [26], [27], [28]. Following [33], [37], we create a simplistic model consisting of  nodes that form

nodes that form  hierarchical levels to capture some essential features of fractal hierarchical geometry in an idealized setting. At the lowest level of the hierarchy, we form fully connected elementary groups of size

hierarchical levels to capture some essential features of fractal hierarchical geometry in an idealized setting. At the lowest level of the hierarchy, we form fully connected elementary groups of size  and weight all edges with the value

and weight all edges with the value  . At each additional level of the hierarchy

. At each additional level of the hierarchy  , we place edges uniformly at random between two modules from the previous level

, we place edges uniformly at random between two modules from the previous level  . The density of these inter-modular edges is given by the probability

. The density of these inter-modular edges is given by the probability  where

where  is a control parameter chosen to match the connection density

is a control parameter chosen to match the connection density  of the empirical data set. To mimic this defining topological feature, we construct the network geometry by letting edge weights at level

of the empirical data set. To mimic this defining topological feature, we construct the network geometry by letting edge weights at level  equal

equal  . For comparisons to the structural (functional) brain data, we generate a model as described above with

. For comparisons to the structural (functional) brain data, we generate a model as described above with

(

( ) and then chose

) and then chose  (

( ) nodes at random, which are deleted along with their corresponding edges.

) nodes at random, which are deleted along with their corresponding edges.

Constructing network ensembles. Each empirical data set displays variable  values. To construct comparable ensembles of synthetic networks, we drew

values. To construct comparable ensembles of synthetic networks, we drew  from a Gaussian distribution defined by the mean and standard deviation of

from a Gaussian distribution defined by the mean and standard deviation of  in the empirical data. For comparisons to DSI empirical data, we constructed ensembles of

in the empirical data. For comparisons to DSI empirical data, we constructed ensembles of  composed of 50 realizations per model. See Supplementary Information Table S1 for details on the ensembles.

composed of 50 realizations per model. See Supplementary Information Table S1 for details on the ensembles.

Mesoscale Network Diagnostics

In this paper we focus on two, complementary network characteristics that can be used to probe the manner in which groups of brain regions are connected with one another: modularity and bipartivity. These methods, however, are more generally applicable, and could be used to evaluate weight dependence of other metrics and data sets as well [38].

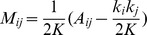

Community detection and modularity

Community detection by modularity maximization identifies a partition of the nodes of a network into groups (or communities) such that nodes are more densely connected with other nodes in their group than expected in an appropriate statistical null model. In this paper, we use this method to extract values of network modularity and other related diagnostics including community laterality, community radius, and the total number and sizes of communities. An additional feature of modularity maximization that is particularly useful for our purposes is its resolution dependency, which enables us to continuously monitor diagnostic values over different organizational levels in the data.

Community detection can be applied to both binary and weighted networks. Assuming node  is assigned to community

is assigned to community  and node

and node  is assigned to community

is assigned to community  , the quality of a partition for a binary network is defined using a modularity index [18], [19], [39], [40], [41]:

, the quality of a partition for a binary network is defined using a modularity index [18], [19], [39], [40], [41]:

| (1) |

where  is a normalization constant,

is a normalization constant,  is the binary adjacency matrix,

is the binary adjacency matrix,  is a structural resolution parameter, and

is a structural resolution parameter, and  is the probability of a connection between nodes

is the probability of a connection between nodes  and

and  under a given null model. Here we use the Newman-Girvan null model [40] that defines the connection probability between any two nodes under the assumption of randomly distributed edges and the constraint of a fixed degree distribution:

under a given null model. Here we use the Newman-Girvan null model [40] that defines the connection probability between any two nodes under the assumption of randomly distributed edges and the constraint of a fixed degree distribution:  , where

, where  is the degree of node

is the degree of node  . We optimize

. We optimize  from Equation 1 using a Louvain-like [42] locally greedy algorithm [43] to identify the optimal partition of the network into communities.

from Equation 1 using a Louvain-like [42] locally greedy algorithm [43] to identify the optimal partition of the network into communities.

For weighted networks, a generalization of the modularity index is defined as [44], [45]:

| (2) |

where  is the total edge weight,

is the total edge weight,  is the weighted adjacency matrix, and

is the weighted adjacency matrix, and  is the strength of node

is the strength of node  defined as the sum of the weights of all edges emanating from node

defined as the sum of the weights of all edges emanating from node  .

.

Due to the non-unique, but nearly-degenerate algorithmic solutions for  and

and  obtained computationally [46], we perform 20 optimizations of Equation 1 or 2 for each network under study. In the results, we report mean values of the following

obtained computationally [46], we perform 20 optimizations of Equation 1 or 2 for each network under study. In the results, we report mean values of the following  diagnostics over these optimizations: the modularity

diagnostics over these optimizations: the modularity  or

or  , the number of communities, the number of singletons (communities that consist of only a single node), and the community laterality and radius (defined in a later sections). We observed that the optimization error in these networks is significantly smaller than the empirical inter-individual or synthetic inter-realization variability, suggesting that these diagnostics produce reliable measurements of network structure (see Supplementary Information).

, the number of communities, the number of singletons (communities that consist of only a single node), and the community laterality and radius (defined in a later sections). We observed that the optimization error in these networks is significantly smaller than the empirical inter-individual or synthetic inter-realization variability, suggesting that these diagnostics produce reliable measurements of network structure (see Supplementary Information).

Community laterality. Laterality is a property that can be applied to any network in which each node can be assigned to one of two categories, and within the community detection method, describes the extent to which a community localizes to one category or the other [29]. In neuroscience, an intuitive category is that of the left and right hemispheres, and in this case laterality quantifies the extent to which the identified communities in functional or structural brain networks are localized within a hemisphere or form bridges between hemispheres.

For an individual community  within the network, the laterality

within the network, the laterality  is defined as [29]:

is defined as [29]:

| (3) |

where  and

and  are the number of nodes located in the left and right hemispheres respectively, or more generally in one or other of the two categories, and

are the number of nodes located in the left and right hemispheres respectively, or more generally in one or other of the two categories, and  is the total number of nodes in

is the total number of nodes in  . The value of

. The value of  ranges between zero (i.e., the number of nodes in the community are evenly distributed between the two categories) and unity (i.e., all nodes in the community are located in a single category).

ranges between zero (i.e., the number of nodes in the community are evenly distributed between the two categories) and unity (i.e., all nodes in the community are located in a single category).

We define the laterality of a given partition of a network as:

|

(4) |

where we use  to denote the expectation value of the laterality under the null model specified by randomly reassigning nodes to the two categories while keeping the total number of nodes in each category fixed. We estimate the expectation value by calculating

to denote the expectation value of the laterality under the null model specified by randomly reassigning nodes to the two categories while keeping the total number of nodes in each category fixed. We estimate the expectation value by calculating  for 1000 randomizations of the data, which ensures that the error in the estimation of the expectation value is of order

for 1000 randomizations of the data, which ensures that the error in the estimation of the expectation value is of order  .

.

The laterality of each community is weighted by the number of nodes it contains, and the expectation value is subtracted to minimize the dependence of  on the number and sizes of detected communities. This correction is important for networks like the brain that exhibit highly fragmented structure. Otherwise the estimation would be biased by the large number of singletons, that by definition have a laterality of

on the number and sizes of detected communities. This correction is important for networks like the brain that exhibit highly fragmented structure. Otherwise the estimation would be biased by the large number of singletons, that by definition have a laterality of  .

.

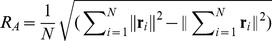

Community radius: To measure the spatial extent of a community in a physically embedded network such as the human brain, we suggest the notion of a community ‘radius’. Each node in the brain network has a position in physical space, which can be delineated by  ,

,  , and

, and  coordinates and which we refer to as that node's position vector. We calculate the standard deviation

coordinates and which we refer to as that node's position vector. We calculate the standard deviation  of the position vectors

of the position vectors  along each dimension

along each dimension  . Then we estimate the radius of the community as the length of the standard deviation vector

. Then we estimate the radius of the community as the length of the standard deviation vector  as follows:

as follows:

| (5) |

where  is the number of nodes in community

is the number of nodes in community  and

and  is the position vector of node

is the position vector of node  .

.

The average community radius of the entire network  is

is

| (6) |

where  serves to weight every community by the number of nodes it contains (compare to Equation 4), and

serves to weight every community by the number of nodes it contains (compare to Equation 4), and  is a normalization constant equal to the ‘radius’ of the entire network:

is a normalization constant equal to the ‘radius’ of the entire network:  . In this investigation, community radius is evaluated only for the empirical brain networks, since the synthetic networks lack a physical embedding.

. In this investigation, community radius is evaluated only for the empirical brain networks, since the synthetic networks lack a physical embedding.

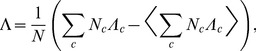

Bipartivity

Bipartivity is a topological network characteristic that occurs naturally in certain complex networks with two types of nodes. A network is perfectly bipartite if it is possible to separate the nodes of the network into two groups, such that all edges lie between the two groups and no edges lie within a group. In this sense bipartivity is a complementary diagnostic to modularity, which maximizes the number of edges within a group and minimizes the number of edges between groups.

Most networks are not perfectly bipartite, but still show a certain degree of bipartivity. A quantitative measure of bipartivity can be defined by considering the subgraph centrality  of the network, which is defined as a weighted sum over the number of closed walks of a given length. Because a network is bipartite if and only if there only exist closed walks of even length, the ratio of the contribution of closed walks of even length to the contribution of closed walks of any length provides a measure of the network bipartivity [47]. As shown in [47], this ratio can be calculated from the eigenvalues

of the network, which is defined as a weighted sum over the number of closed walks of a given length. Because a network is bipartite if and only if there only exist closed walks of even length, the ratio of the contribution of closed walks of even length to the contribution of closed walks of any length provides a measure of the network bipartivity [47]. As shown in [47], this ratio can be calculated from the eigenvalues  of the adjacency matrix [47]:

of the adjacency matrix [47]:

|

(7) |

where  is the contribution of closed walks of even length to the subgraph centrality. In this formulation,

is the contribution of closed walks of even length to the subgraph centrality. In this formulation,  takes values between

takes values between  for the least bipartite graphs (fully connected graphs) and

for the least bipartite graphs (fully connected graphs) and  for a perfectly bipartite graph [47].

for a perfectly bipartite graph [47].

The definition of bipartivity given in Equation 7 provides an estimate of  but does not provide a partition of network nodes into the two groups. To identify these partitions, we calculate the eigenvector corresponding to the smallest eigenvalue

but does not provide a partition of network nodes into the two groups. To identify these partitions, we calculate the eigenvector corresponding to the smallest eigenvalue  of the modularity quality matrix

of the modularity quality matrix  [48]. We then partition the network according to the signs of the entries of this eigenvector: nodes with positive entries in the eigenvector form group one and nodes with negative entries in the eigenvector form group two. This spectral formulation demonstrates that bipartivity is in some sense an anti-community structure [48]: community structure corresponds to the highest eigenvalues of

[48]. We then partition the network according to the signs of the entries of this eigenvector: nodes with positive entries in the eigenvector form group one and nodes with negative entries in the eigenvector form group two. This spectral formulation demonstrates that bipartivity is in some sense an anti-community structure [48]: community structure corresponds to the highest eigenvalues of  while the bipartivity corresponds to the lowest eigenvalue of

while the bipartivity corresponds to the lowest eigenvalue of  .

.

Multi-Resolution Methods

We quantify organization of weighted networks across varying ranges of connection weights (weak to strong) and connection lengths (short to long), using three complementary approaches: soft thresholding, windowed thresholding, and multi-resolution community detection. Each method employs a control parameter that we vary to generate network diagnostic curves, representing characteristics of the network under study. We refer to these curves as mesoscopic response functions (MRF) of the network [34]. A summary of the methods and control parameters is contained in Table 1.

Soft thresholding

To date, most investigations that have utilized thresholding to study brain networks have focused on cumulative thresholding [4], where a weighted network is converted to a binary network (binarized) by selecting a single threshold parameter  and setting all connections with weight

and setting all connections with weight  to

to  and all other entries to

and all other entries to  . Varying

. Varying  produces multiple binary matrices over a wide range of connection densities (sparsity range). On each of these matrices, we can compute a network diagnostic of interest. One disadvantage of this hard thresholding technique is that it assumes that matrix elements with weights just below

produces multiple binary matrices over a wide range of connection densities (sparsity range). On each of these matrices, we can compute a network diagnostic of interest. One disadvantage of this hard thresholding technique is that it assumes that matrix elements with weights just below  are significantly different from weights just above

are significantly different from weights just above  .

.

Soft thresholding [49], [50] instead probes the full network geometry as a function of edge weight. First, we normalize edge weights to ensure that all  are in

are in  . Next, we create a family of graphs from each network by reshaping its weight distribution by taking the adjacency matrix to the power

. Next, we create a family of graphs from each network by reshaping its weight distribution by taking the adjacency matrix to the power  :

:  . At each value of

. At each value of  , the distribution of edge weights – and by extension, the network geometry – is altered. As

, the distribution of edge weights – and by extension, the network geometry – is altered. As  goes towards zero, all nonzero elements of the matrix have larger and larger weights. At

goes towards zero, all nonzero elements of the matrix have larger and larger weights. At  , the weight distribution approximates a delta function: all nonzero elements of the resulting matrix have the same weight of

, the weight distribution approximates a delta function: all nonzero elements of the resulting matrix have the same weight of  , which corresponds to the application of a hard threshold at

, which corresponds to the application of a hard threshold at  . At

. At  , the weight distribution is heavy-tailed: the majority of elements of the resulting matrix are equal to

, the weight distribution is heavy-tailed: the majority of elements of the resulting matrix are equal to  , corresponding to the application of a hard threshold at

, corresponding to the application of a hard threshold at  .

.

Windowed thresholding

A potential disadvantage of both the cumulative and soft thresholding approaches is that results may be driven by effects of both connection density and the organization of the edges with the largest weights. As a result, these procedures can neglect underlying structure associated with weaker connections.

Windowed thresholding [15], [49] instead independently probes the topology of families of edges of different weights. We replace the cumulative threshold  with a threshold window

with a threshold window  that enforces an upper and lower bound on the edge weights retained in the construction of a binary matrix. We can specify this window using two parameters: (i) a fixed percentage

that enforces an upper and lower bound on the edge weights retained in the construction of a binary matrix. We can specify this window using two parameters: (i) a fixed percentage  of connections which are retained in each window, and (ii) the average percentile weight

of connections which are retained in each window, and (ii) the average percentile weight  of connections in each window. Note that we refer to the average percentile edge weight

of connections in each window. Note that we refer to the average percentile edge weight  in the remainder of this document as the connection weight. For example, if we specify

in the remainder of this document as the connection weight. For example, if we specify  and

and  , then we can identify the values

, then we can identify the values  and

and  (here given as percentiles of all connections) that provide a set of

(here given as percentiles of all connections) that provide a set of  edges whose average percentile edge weight is

edges whose average percentile edge weight is  . Each pair of variables (

. Each pair of variables ( ) ensures a unique set of edges.

) ensures a unique set of edges.

More specifically, for each network  , we construct a family of binary graphs

, we construct a family of binary graphs  , each of which depends on the window size

, each of which depends on the window size  (percentage of connections retained), and the average weight

(percentage of connections retained), and the average weight  of connections in the window (together

of connections in the window (together  and

and  determine the upper and lower bounds,

determine the upper and lower bounds,  and

and  , defining the window):

, defining the window):

| (8) |

The fixed window size (5%–25%) mitigate biases associated with variable connection densities [4], [14], [15]. Each resulting binary graph  in the family summarizes the topology of edges with a given range of weights. The window size sets a resolution limit to the scale on which one can observe weight dependent changes in structure (see the Supplementary Information).

in the family summarizes the topology of edges with a given range of weights. The window size sets a resolution limit to the scale on which one can observe weight dependent changes in structure (see the Supplementary Information).

To probe the roles of weak versus strong edges and short versus long edges in the empirical brain networks, we extract families of graphs based on (i) networks weighted by correlation strength (fMRI), (ii) networks weighted by number of white matter streamlines (DSI), (iii) networks weighted by Euclidean distance between brain regions (DSI), and (iv) one network weighted by fiber tract arc length (DSI). For each case we compute graph diagnostics as a function of the associated connection weight  . This method isolates effects associated with different connection weights, but does not resolve network organization across different ranges of weights.

. This method isolates effects associated with different connection weights, but does not resolve network organization across different ranges of weights.

Resolution in community detection

The definition of modularity in Equations 1,2 includes a resolution parameter  [51], [52], [53] which tunes the size of communities in the optimal partition: high values of

[51], [52], [53] which tunes the size of communities in the optimal partition: high values of  lead to many small communities and low values of

lead to many small communities and low values of  lead to a few large communities. We vary

lead to a few large communities. We vary  to explore partitions with a range of mean community sizes: for the smallest value of

to explore partitions with a range of mean community sizes: for the smallest value of  the partition contains a single community of size

the partition contains a single community of size  , while for the largest value of

, while for the largest value of  the partition contains

the partition contains  communities of size unity. In physically embedded systems, such as brain networks, one can probe the relationship between structural scales uncovered by different

communities of size unity. In physically embedded systems, such as brain networks, one can probe the relationship between structural scales uncovered by different  values and spatial scales defined by the mean community radius

values and spatial scales defined by the mean community radius  .

.

Results

Multi-resolution methods serve as tools to investigate the structure of networks in ways that are unapproachable to single-resolution methods. What types of multi-resolution structure might be present in a network? One type of multi-resolution structure corresponds to the properties of individuals edges. In weighted embedded networks, for example, edges have both weights and lengths, and therefore network architecture might vary over both weight- or length-scales, and even perhaps differently over these two scales. Understanding this multi-resolution structure can inform our interpretations of network diagnostics and can provide mathematical means to distinguish between real and synthetic networks or between healthy and diseased brain networks.

To illustrate these points, we apply multi-resolution diagnostics to a sequence of  problems involving weighted empirical and synthetic network data (see Fig. 1). Problem 1 illustrates the utility of multi-resolution methods in informing our interpretations of network diagnostics. Problems 2 and 5 illustrate the utility of multi-resolution methods in distinguishing different types of networks. Problems 3 and 4 illustrate how multi-resolution structure in networks can differ across weight and length scales. We summarize each of these problems in more detail below.

problems involving weighted empirical and synthetic network data (see Fig. 1). Problem 1 illustrates the utility of multi-resolution methods in informing our interpretations of network diagnostics. Problems 2 and 5 illustrate the utility of multi-resolution methods in distinguishing different types of networks. Problems 3 and 4 illustrate how multi-resolution structure in networks can differ across weight and length scales. We summarize each of these problems in more detail below.

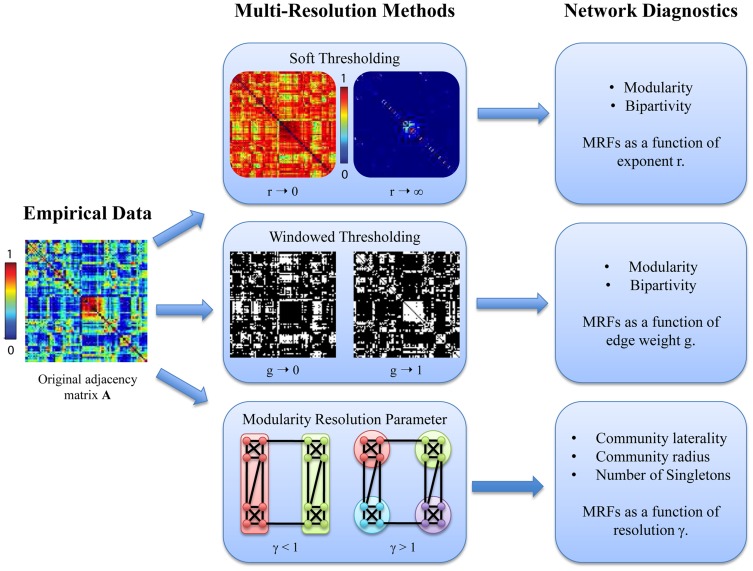

Figure 1. Pictorial schematic of multi-resolution methods for weighted networks.

We can apply soft or windowed thresholding, and vary the resolution parameter of modularity maximization to uncover multiresolution structure in empirical data that we summarize in the form of MRFs of network diagnostics.

Problem 1: Probing Drivers of Weighted Modularity. We begin our analysis with the weighted modularity

(Equation 2), a diagnostic that is based on the full weighted adjacency matrix. Using soft thresholding, we show that

(Equation 2), a diagnostic that is based on the full weighted adjacency matrix. Using soft thresholding, we show that  is most sensitive to the strongest connections. This motivates the use of windowed thresholding to isolate the topology of connections based on their weight.

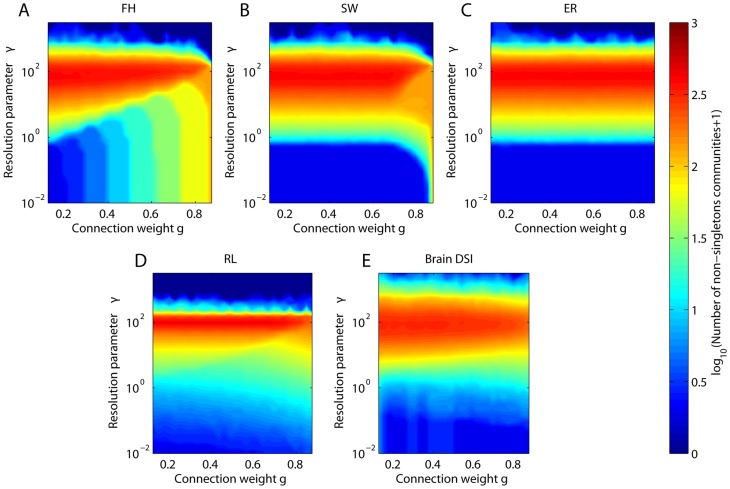

is most sensitive to the strongest connections. This motivates the use of windowed thresholding to isolate the topology of connections based on their weight.Problem 2: Determining Network Differences in Multiresolution Structure. In anatomical brain data and corresponding synthetic networks, we use windowed thresholding to obtain multi-resolution response functions (MRFs) for modularity

and bipartivity

and bipartivity  as a function of the average weight

as a function of the average weight  within the window. MRFs of synthetic networks do not resemble MRFs of the brain.

within the window. MRFs of synthetic networks do not resemble MRFs of the brain.Problem 3: Uncovering Differential Structure in Edge Strength & Length. Using windowed thresholding, we probed the multiresolution structure in anatomical brain data captured by two measures of connection weight: fiber density and fiber length. We observe that communities involving short, high density fibers tend to be localized in one hemisphere, while communities involving long, low density fibers span the hemispheres.

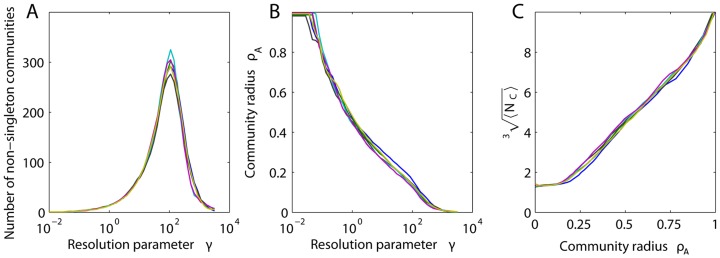

Problem 4: Identifying Physical Correlates of Multiresolution Structure. To investigate structure that spans geometric scales, we vary the resolution parameter in modularity maximization to probe mesoscale structure at large (few communities) and small scales (many communities). By calculating community radius, we find that large communities, as measured by the number of nodes, are embedded in large physical spaces.

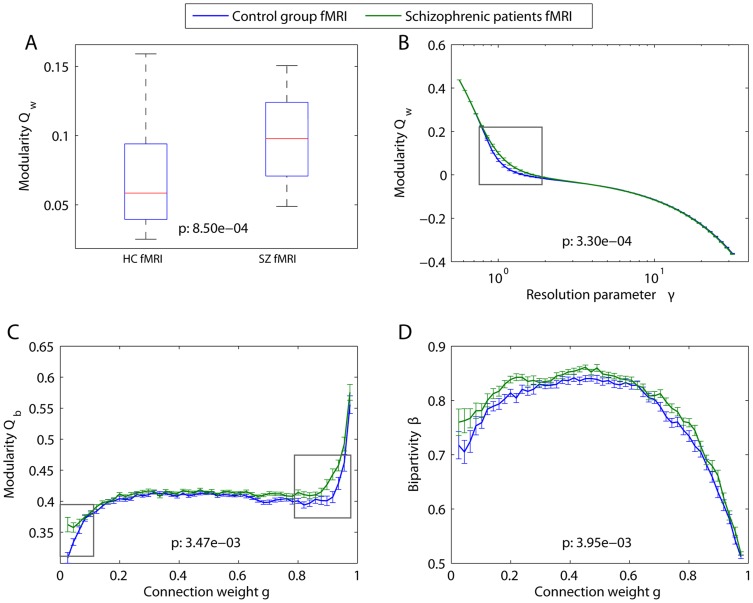

Problem 5: Demonstrating Clinical Relevance. To test diagnostic applicability, we apply our methods to functional (fMRI) networks extracted from a people with schizophrenia and healthy controls. Using windowed thresholding, we observe previously hidden significant differences between the two groups in specific weight ranges, suggesting that multi-resolution methods provide a powerful approach to differentiating clinical groups.

In the remainder of this Results section, we describe each of these problems and subsequent observations in greater detail.

Probing Drivers of Weighted Modularity

In this first section, we examine Problem 1: Probing Drivers of Weighted Modularity. We begin our analysis with measurements that illustrate the sensitivity of mesoscale network diagnostics to the edge weight organization and distribution. We employ the weighted modularity  to characterize the community structure of the network and ask whether the value of this diagnostic is primarily driven by the organization of strong edges or by the organization of weak edges. To answer this question, we will utilize two methods: network rewiring and soft thresholding.

to characterize the community structure of the network and ask whether the value of this diagnostic is primarily driven by the organization of strong edges or by the organization of weak edges. To answer this question, we will utilize two methods: network rewiring and soft thresholding.

Rewiring

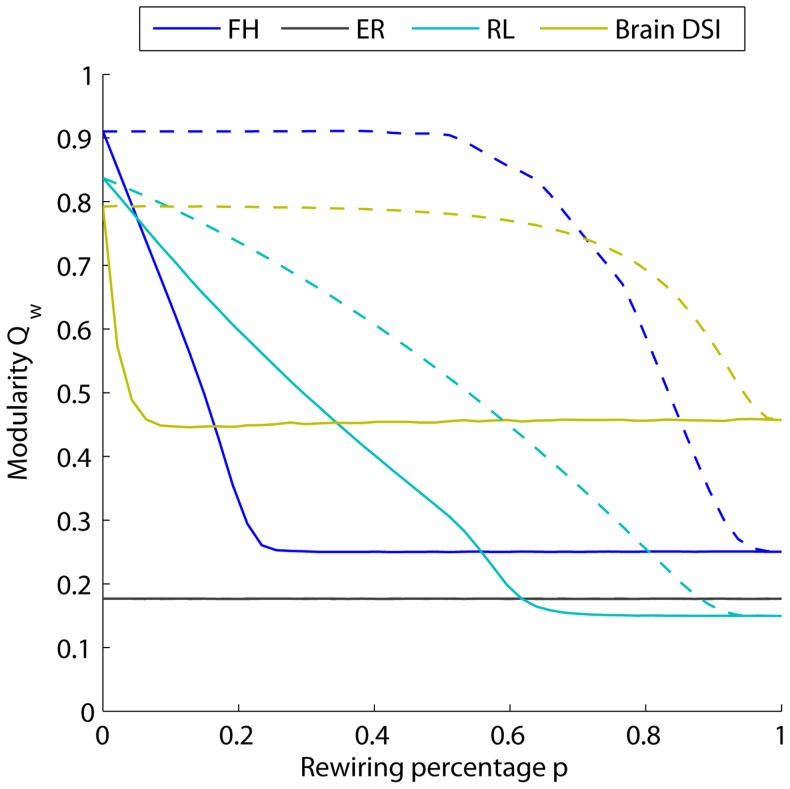

By randomly rewiring connections in a weighted network, one can quantify which connections dominate the value of the diagnostic in the original adjacency matrix. In empirical DSI data and three synthetic networks, we compare results obtained when a percentage  of the connections are rewired, starting with the strongest connections (solid lines) or starting with the weakest connections (dashed lines); see Fig. 2. We observe that modularity

of the connections are rewired, starting with the strongest connections (solid lines) or starting with the weakest connections (dashed lines); see Fig. 2. We observe that modularity  as a function of rewiring percentage

as a function of rewiring percentage  depends on the network topology. Randomly rewiring an Erdös-Rényi network has no effect on

depends on the network topology. Randomly rewiring an Erdös-Rényi network has no effect on  since it does not alter the underlying geometry. However, randomly rewiring a human DSI network or a synthetic fractal hierarchical or ring lattice network leads to changes in

since it does not alter the underlying geometry. However, randomly rewiring a human DSI network or a synthetic fractal hierarchical or ring lattice network leads to changes in  , that moreover depend on the types of edges rewired. Rewiring a large fraction of the weakest edges has a negligible effect on the value of

, that moreover depend on the types of edges rewired. Rewiring a large fraction of the weakest edges has a negligible effect on the value of  , while rewiring even a few of the strongest edges decreases the value of

, while rewiring even a few of the strongest edges decreases the value of  drastically in all three networks. These results illustrate that the value of

drastically in all three networks. These results illustrate that the value of  is dominated by a few edges with the largest weights. For additional contributions to

is dominated by a few edges with the largest weights. For additional contributions to  from the number of singletons in the network, see Supplementary Figure S4 and accompanying text.

from the number of singletons in the network, see Supplementary Figure S4 and accompanying text.

Figure 2. Use of rewiring strategies to probe geometric drivers of weighted modularity.

Changes in the maximum modularity as a given percentage  of the connections are randomly rewired for synthetic (fractal hierarchical, FR, in blue; Erdös-Rényi, ER, in black; ring lattice, RL, in cyan) and empirical (Brain DSI in mustard) networks. Dashed lines show the change of modularity when the

of the connections are randomly rewired for synthetic (fractal hierarchical, FR, in blue; Erdös-Rényi, ER, in black; ring lattice, RL, in cyan) and empirical (Brain DSI in mustard) networks. Dashed lines show the change of modularity when the  weakest connections are randomly rewired; solid lines illustrate the corresponding results when the

weakest connections are randomly rewired; solid lines illustrate the corresponding results when the  strongest connections are rewired. For the brain data and the synthetic networks, the value of the weighted modularity

strongest connections are rewired. For the brain data and the synthetic networks, the value of the weighted modularity  is most sensitive to the strongest connections in both the synthetic and empirical networks.

is most sensitive to the strongest connections in both the synthetic and empirical networks.

Soft thresholding

To more directly examine the role of edge weight in the value of the maximum modularity, we employ soft thresholding, which individually raises all entries in the adjacency matrix to a power  (see the Methods Section for methodological details and Fig. 1 for a schematic). Small values of

(see the Methods Section for methodological details and Fig. 1 for a schematic). Small values of  tend to equalize the original weights, while larger values of

tend to equalize the original weights, while larger values of  increasingly emphasize the stronger connections. By varying

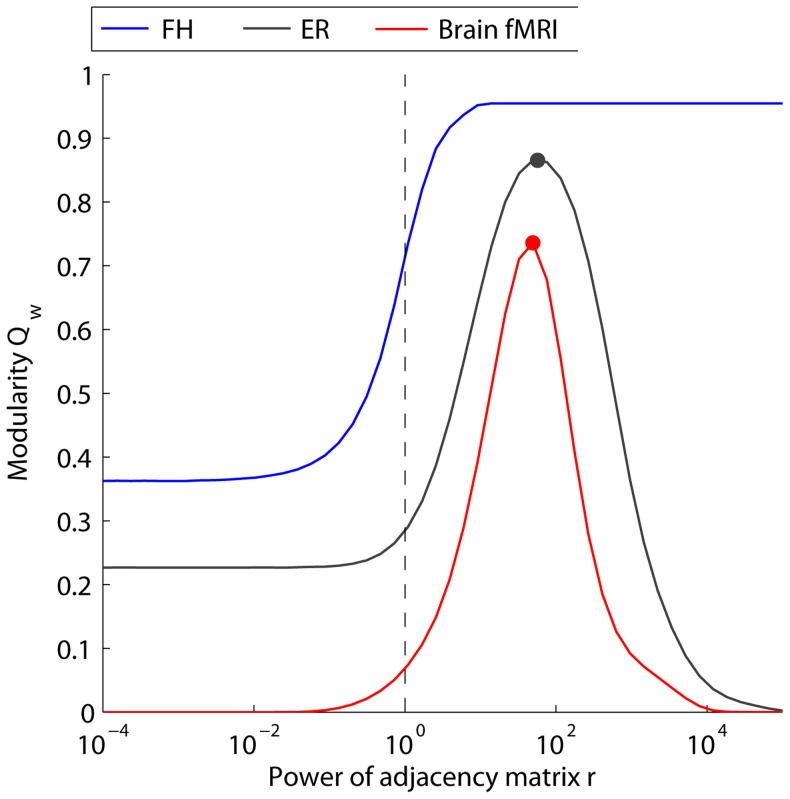

increasingly emphasize the stronger connections. By varying  , we can probe similarities and differences in both the weight distributions and weight geometries. In Fig. 3 we evaluate the mesoscopic response function (MRF)

, we can probe similarities and differences in both the weight distributions and weight geometries. In Fig. 3 we evaluate the mesoscopic response function (MRF)  as a function of

as a function of  , for empirical functional (fMRI) brain networks, as well as two synthetic networks. While the range of

, for empirical functional (fMRI) brain networks, as well as two synthetic networks. While the range of  most useful to study in any particular scientific investigation is an open question, here we vary

most useful to study in any particular scientific investigation is an open question, here we vary  from

from  to

to  . Our results illustrate that

. Our results illustrate that  varies both in shape and limiting behavior for different networks.

varies both in shape and limiting behavior for different networks.

Figure 3. Use of soft thresholding strategies to probe geometric drivers of weighted modularity.

Changes in maximum modularity  as a function of the control parameter

as a function of the control parameter  for soft thresholding. MRFs are presented for synthetic (fractal hierarchical, FR, in blue; Erdös-Rényi, ER, in black) and empirical (Brain fMRI in red) networks. Dots mark the peak value for different curves, which occur at different values of

for soft thresholding. MRFs are presented for synthetic (fractal hierarchical, FR, in blue; Erdös-Rényi, ER, in black) and empirical (Brain fMRI in red) networks. Dots mark the peak value for different curves, which occur at different values of  . The vertical dashed line marks the conventional value of

. The vertical dashed line marks the conventional value of  obtained for

obtained for  . The single, point summary statistic

. The single, point summary statistic  fails to capture the full structure of the MRF revealed using soft thresholding.

fails to capture the full structure of the MRF revealed using soft thresholding.

In the limit of  , the sparse networks (FH and ER) all converge to a non-zero value of

, the sparse networks (FH and ER) all converge to a non-zero value of  , while the fully connected fMRI network converges to

, while the fully connected fMRI network converges to  . In the limit of

. In the limit of  , the networks in which all edges have unique weights (i.e., a continuous weight distribution, which occurs in the empirical network as well as the ER network) converge to

, the networks in which all edges have unique weights (i.e., a continuous weight distribution, which occurs in the empirical network as well as the ER network) converge to  , while the FH network, where by construction there exists multiple edges with the maximum edge weight, (i.e., a discrete weight distribution) converge to a non-zero value of

, while the FH network, where by construction there exists multiple edges with the maximum edge weight, (i.e., a discrete weight distribution) converge to a non-zero value of  . Networks with continuous rather than discrete weight distributions display a peak in

. Networks with continuous rather than discrete weight distributions display a peak in  , but the

, but the  value at which this peak occurs (

value at which this peak occurs ( , marked by a dot on each curve in Fig. 3) differs for each network. The conventional measurement of weighted modularity

, marked by a dot on each curve in Fig. 3) differs for each network. The conventional measurement of weighted modularity  is associated with the value for

is associated with the value for  (i.e. the original adjacency matrix), marked by the vertical dashed line in Fig. 3). In comparing curves it is clear that the conventional measurement (a single point) fails to extract the more complete structure obtained by computing the MRF using soft thresholding.

(i.e. the original adjacency matrix), marked by the vertical dashed line in Fig. 3). In comparing curves it is clear that the conventional measurement (a single point) fails to extract the more complete structure obtained by computing the MRF using soft thresholding.

Summary

The results presented in Fig. 2 and Fig. 3 provide two types of diagnostic curves that illustrate features of the underlying weight distribution and network geometry. The curves themselves and the value of  in Fig. 3 could be used to uncover differences in multiresolution network structure, for example in healthy versus diseased human brains. However, because the value of

in Fig. 3 could be used to uncover differences in multiresolution network structure, for example in healthy versus diseased human brains. However, because the value of  is dominated by a few edges with the largest weights, the identification of community structure in weak or medium-strength edges requires an entirely separate mathematical approach that probes the pattern of edges as a function of their weight, such as is provided by windowed thresholding (see next section).

is dominated by a few edges with the largest weights, the identification of community structure in weak or medium-strength edges requires an entirely separate mathematical approach that probes the pattern of edges as a function of their weight, such as is provided by windowed thresholding (see next section).

Determining Network Differences in Multiresolution Structure

In this section, we examine Problem 2: Determining Network Differences in Multiresolution Structure. Determining differences in multiresolution network structure requires a set of techniques that quantify and summarize this structure in mesoscopic response functions of network diagnostics. Windowed thresholding is a unique candidate technique in that it resolves network structure associated with sets of edges with different weights. The technique decomposes a weighted adjacency matrix into a family of graphs. Each graph in this family shares a window size corresponding to the percentage of edges in the original network retained in the graph. A family of graphs is therefore characterized by a control parameter corresponding to the mean weight  of edges within the window. As we illustrate below in the context of network modularity and bipartivity, this control parameter can be optimized to uncover differences in multiresolution structure of networks.

of edges within the window. As we illustrate below in the context of network modularity and bipartivity, this control parameter can be optimized to uncover differences in multiresolution structure of networks.

Modularity

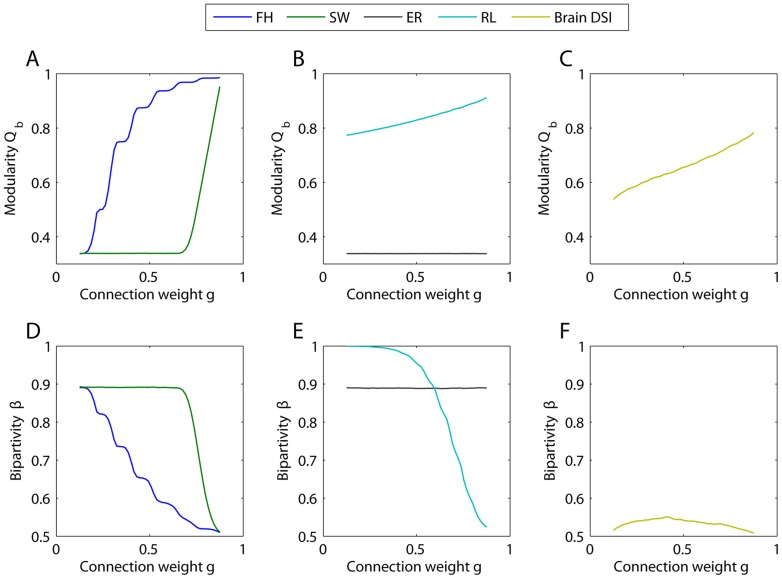

The modularity MRF  as a function of weight

as a function of weight  distinguishes between different networks in both its shape and its limiting behavior (see Figure 4A–C). The fractal hierarchical model (FH) yields a stepwise increase in modularity, where each step corresponds to one hierarchical level. The small world model (SW) illustrates two different regimes corresponding to (i) the random structure of the weakest 60% of the connections and (ii) the perfectly modular structure of the strongly connected elementary groups. The Erdös-Rényi network (ER) exhibits no weight dependence in modularity, since the underlying topology is constant across different weight values. The ring lattice exhibits an approximately linear increase in modularity, corresponding to the densely interconnected local neighborhoods of the chain. The structural brain network exhibits higher modularity than ER graphs over the entire weight range, with more community structure evident in graphs composed of strong weights.

distinguishes between different networks in both its shape and its limiting behavior (see Figure 4A–C). The fractal hierarchical model (FH) yields a stepwise increase in modularity, where each step corresponds to one hierarchical level. The small world model (SW) illustrates two different regimes corresponding to (i) the random structure of the weakest 60% of the connections and (ii) the perfectly modular structure of the strongly connected elementary groups. The Erdös-Rényi network (ER) exhibits no weight dependence in modularity, since the underlying topology is constant across different weight values. The ring lattice exhibits an approximately linear increase in modularity, corresponding to the densely interconnected local neighborhoods of the chain. The structural brain network exhibits higher modularity than ER graphs over the entire weight range, with more community structure evident in graphs composed of strong weights.

Figure 4. Mesoscale diagnostics as a function of connection weight.

(A–C) Modularity as a function of the average connection weight  (see Methods Section) for fractal hierarchical, small world (B), Erdös-Rényi random, regular lattice (C) and structural brain network (D). The results shown here are averaged over 20 realizations of the community detection algorithm and over 50 realizations of each model (6 subjects for the brain DSI data). The variance in the measurements is smaller than the line width. (D–F) Bipartivity as function of average connection weight of the fractal hierarchical, small world, Erös-Rényi random model networks and the DSI structural brain networks. We report the initial benchmark results for a window size of 25% but find that results from other window sizes are qualitatively similar (see the Supporting Information).

(see Methods Section) for fractal hierarchical, small world (B), Erdös-Rényi random, regular lattice (C) and structural brain network (D). The results shown here are averaged over 20 realizations of the community detection algorithm and over 50 realizations of each model (6 subjects for the brain DSI data). The variance in the measurements is smaller than the line width. (D–F) Bipartivity as function of average connection weight of the fractal hierarchical, small world, Erös-Rényi random model networks and the DSI structural brain networks. We report the initial benchmark results for a window size of 25% but find that results from other window sizes are qualitatively similar (see the Supporting Information).

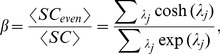

Bipartivity

The bipartivity MRF  as a function of weight

as a function of weight  also distinguishes between different networks in both its shape and its limiting behavior (see Fig. 4C–E). The bipartivity of the Erdös-Rényi network serves as a benchmark for a given choice of the window size, since the underlying uniform structure is perfectly homogeneous, and

also distinguishes between different networks in both its shape and its limiting behavior (see Fig. 4C–E). The bipartivity of the Erdös-Rényi network serves as a benchmark for a given choice of the window size, since the underlying uniform structure is perfectly homogeneous, and  therefore only depends on the connection density of the graph. The small world model (SW) again shows two different regimes corresponding to (i) the random structure of the weakest 60% of the connections and (ii) the perfectly modular (or anti-bipartite [48]) structure of the strongly connected elementary groups. The fractal hierarchical model shows a stepwise decrease in bipartivity, corresponding to the increasing strength of community structure at higher levels of the hierarchy. The regular chain lattice model shows greatest bipartivity for the weakest 50% of connections and lowest bipartivity for the strongest 50% of connections. Intuitively, this behavior stems from the fact that the weaker edges link nodes to neighbors at farther distances away, making a delineation into two sparsely intra-connected subgroups more fitting.

therefore only depends on the connection density of the graph. The small world model (SW) again shows two different regimes corresponding to (i) the random structure of the weakest 60% of the connections and (ii) the perfectly modular (or anti-bipartite [48]) structure of the strongly connected elementary groups. The fractal hierarchical model shows a stepwise decrease in bipartivity, corresponding to the increasing strength of community structure at higher levels of the hierarchy. The regular chain lattice model shows greatest bipartivity for the weakest 50% of connections and lowest bipartivity for the strongest 50% of connections. Intuitively, this behavior stems from the fact that the weaker edges link nodes to neighbors at farther distances away, making a delineation into two sparsely intra-connected subgroups more fitting.

Summary: In all model networks, the bipartivity shows the opposite trend as that observed in the modularity (compare top and bottom rows of Figure 4), supporting the interpretation of bipartivity as a measurement of “anti-community” structure [48]. It is therefore of interest to note that the DSI brain data shows very low bipartivity (close to the minimum possible value of  ) over the entire weight range, consistent with its pronounced community structure over different weight-based resolutions.

) over the entire weight range, consistent with its pronounced community structure over different weight-based resolutions.

Uncovering differential structure in edge strength & length

In this section, we examine Problem 3: Uncovering Differential Structure in Edge Strength & Length. Unlike the synthetic networks, human brain networks are physically embedded in the 3-dimensional volume of the cranium. Each node in the network is therefore associated with a set of spatial coordinates and each edge in the network is associated with a distance between these coordinates. MRFs for network diagnostics can be used to compare this physical embedding with the network's structure, and, as we show below, could offer particular utility in uncovering neurophysiologically relevant individual differences in network architecture.

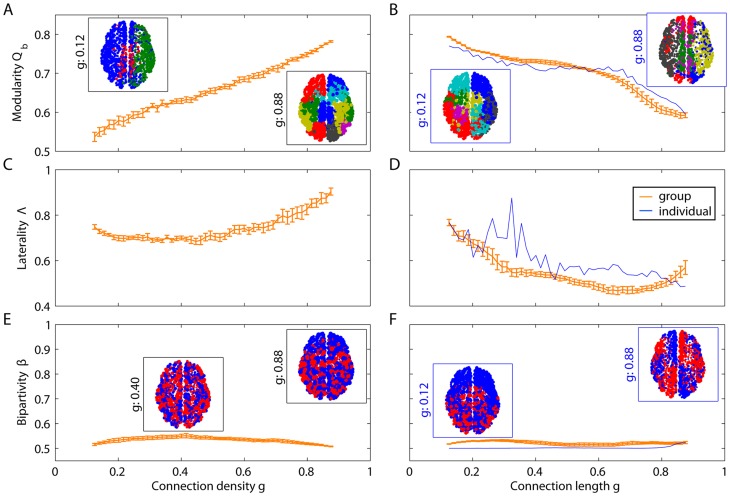

To illustrate the utility of this approach, we extract MRFs using two different measures of connection weight  for structural DSI brain data (see Figure 5). In one case

for structural DSI brain data (see Figure 5). In one case  is the density of fiber tracts between two nodes, and in the other case

is the density of fiber tracts between two nodes, and in the other case  is the length of the connections, measured by Euclidean distance or tract length. High density and short length edges tend to show more prominent community structure (higher

is the length of the connections, measured by Euclidean distance or tract length. High density and short length edges tend to show more prominent community structure (higher  ), with communities tending to be isolated in separate hemispheres (higher

), with communities tending to be isolated in separate hemispheres (higher  ). Low density and long edges tend to show less prominent community structure (lower

). Low density and long edges tend to show less prominent community structure (lower  ), with communities tending to span the two hemispheres (lower

), with communities tending to span the two hemispheres (lower  ). Bipartivity peaks for long fiber tract arc lengths, corresponding to the separation of the left and right hemisphere which is even more evident in smaller window sizes (see Supplementary Information). These results suggest a relationship between spatial and topological structure that can be identified across all edge weights and lengths.

). Bipartivity peaks for long fiber tract arc lengths, corresponding to the separation of the left and right hemisphere which is even more evident in smaller window sizes (see Supplementary Information). These results suggest a relationship between spatial and topological structure that can be identified across all edge weights and lengths.

Figure 5. Effect of connection density and length on mesoscale diagnostics.

(A–B) Modularity  , (C–D) laterality

, (C–D) laterality  and (E–F) bipartivity

and (E–F) bipartivity  as a function of the fiber tract density density (A,C,E), fiber tract arc length (B,D,F, blue curve) and Euclidean distance (B,D,F, orange curve). Orange curves correspond to the mean diagnostic value over DSI networks; blue curves correspond to the diagnostic value estimated from a single individual. The orange curves in panels B, D, and F represent the Euclidean distance between the nodes; the blue curve represents the average arc length of the fiber tracts. The insets illustrate partitions of one representative data set (see the Methods Section), indicating that communities tend to span the two hemispheres thus leading to low values of bipartivity. All curves and insets were calculated with a window size of

as a function of the fiber tract density density (A,C,E), fiber tract arc length (B,D,F, blue curve) and Euclidean distance (B,D,F, orange curve). Orange curves correspond to the mean diagnostic value over DSI networks; blue curves correspond to the diagnostic value estimated from a single individual. The orange curves in panels B, D, and F represent the Euclidean distance between the nodes; the blue curve represents the average arc length of the fiber tracts. The insets illustrate partitions of one representative data set (see the Methods Section), indicating that communities tend to span the two hemispheres thus leading to low values of bipartivity. All curves and insets were calculated with a window size of  .

.

The shapes of the MRFs are consistent across individuals. The small amount of inter-individual variability in  and

and  is observed in graphs composed of weak edges. Weak connections may be (i) most sensitive to noise in the experimental measurements, or (ii) most relevant to the biological differences between individuals [15]. Further investigation of individual differences associated with weak connections is needed to resolve this question.