Abstract

A macrocyclic β-sheet peptide containing two nonapeptide segments based on Aβ15–23 (QKLVFFAED) forms fibril-like assemblies of oligomers in the solid state. The X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3 was determined at 1.75 Å resolution. The macrocycle forms hydrogen-bonded dimers, which further assemble along the fibril axis in a fashion resembling a herringbone pattern. The extended β-sheet comprising the dimers is laminated against a second layer of dimers through hydrophobic interactions to form a fibril-like assembly that runs the length of the crystal lattice. The second layer is offset by one monomer subunit, so that the fibril-like assembly is composed of partially overlapping dimers, rather than discrete tetramers. In aqueous solution, macrocyclic β-sheet 3 and homologues 4 and 5 form discrete tetramers, rather than extended fibril-like assemblies. The fibril-like assemblies of oligomers formed in the solid state by macrocyclic β-sheet 3 represent a new mode of supramolecular assembly not previously observed for the amyloidogenic central region of Aβ. The structures observed at atomic resolution for this peptide model system may offer insights into the structures of oligomers and oligomer assemblies formed by full-length Aβ and may provide a window into the propagation and replication of amyloid oligomers.

Introduction

The supramolecular assembly of the β-amyloid peptide Aβ to form fibrils and soluble oligomers has been the subject of intense interest and study over the past two decades. The plaques formed by the 40–42 amino acid Aβ polypeptide in the brain are one of the most distinctive physiological features of Alzheimer’s disease, while the more cryptic soluble Aβ oligomers that also form are now thought to be the primary culprits in the devastating neurodegeneration that occurs.1 In β-amyloid fibrils, the central region of Aβ forms an extended network of β-sheets.2 The oligomers also appear to involve β-sheet formation, but their structures are still largely unknown at atomic resolution.3,4 Enhanced understanding of the structures and interactions of the oligomers and fibrils offers the promise of preventing and treating Alzheimer’s and other amyloid diseases.

The highly amyloidogenic central region of Aβ, which includes the hydrophobic pentapeptide sequence LVFFA (Aβ17–21) has provided an archetype not only for the assembly of Aβ but also for amyloidogenic peptides and proteins in general.5 This region is particularly prone to interaction, and peptides derived from Aβ17–21 have been found to inhibit the aggregation of full length Aβ.6 The hydrophobic residues 17–21 are flanked by cationic and anionic residues K16 and E22, making the heptapeptide sequence KLVFFAE (Aβ16–22) especially prone to supramolecular assembly to form fibrils and nanotubes.7

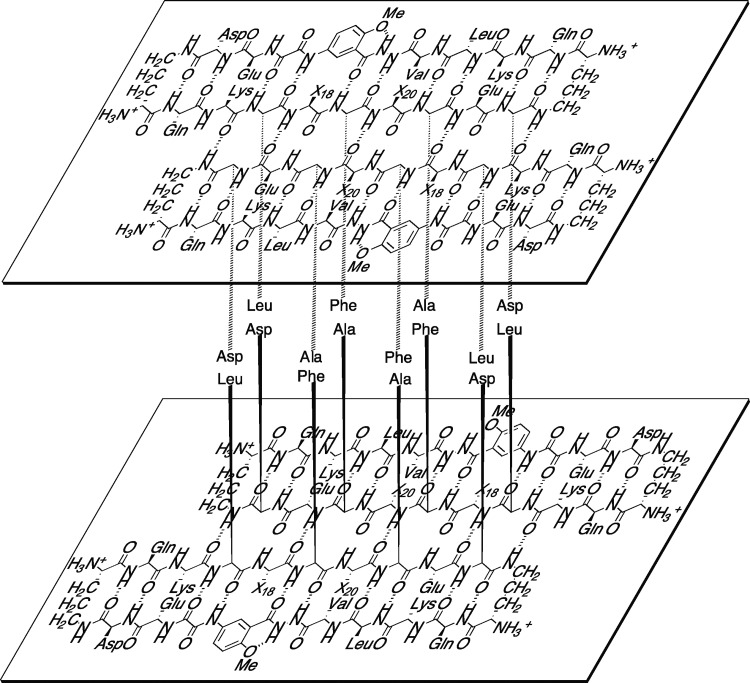

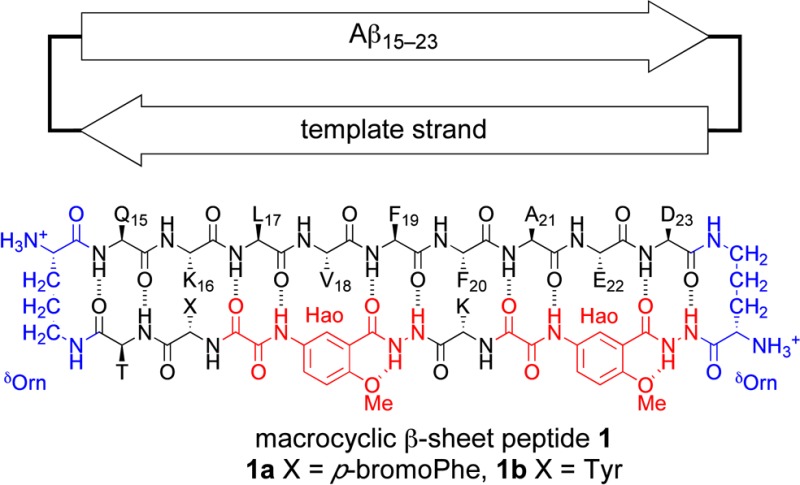

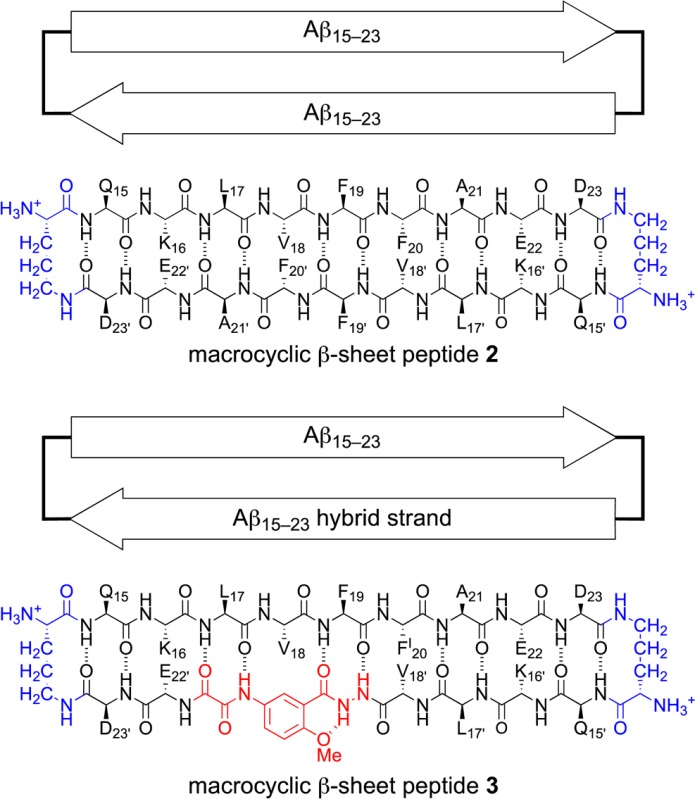

We recently began using

macrocyclic β-sheet peptides containing

the nonapeptide sequence QKLVFFAED (Aβ15–23) as a model system with which to explore the structures and interactions

of amyloid oligomers. We incorporated the Aβ15–23 nonapeptide into a 66-membered ring macrocycle containing template

and turn units that help enforce a β-sheet structure and block

uncontrolled aggregation, and we studied the supramolecular assembly

of the resulting macrocyclic β-sheet peptides 1 in the solid state by X-ray crystallography and in aqueous solution

by NMR spectroscopy.8,9 Macrocyclic β-sheets 1 contain an Aβ15–23 peptide strand

connected through two δ-linked ornithine turn units (δOrn) to a template strand that contains two Hao amino acid tripeptide

mimics.10,11 In the solid state, macrocyclic β-sheet

peptide 1a forms tetramers, dodecamers, and porelike

assemblies of oligomers. In solution, macrocyclic β-sheets 1 form tetramers that differ in structure from those in the

solid state. The differences between the solid-state and solution-state

tetramers are important, because they reveal polymorphism among amyloid

oligomers at atomic resolution and illustrate the importance of environment

upon oligomer structure.

In the current study, we envisioned

replacing the template strand

with Aβ15–23 and determining the structures

of the oligomers that form. Attempts to synthesize and study macrocyclic

β-sheet peptide 2, which embodies this concept,

proved fruitless, yielding only an insoluble peptide hydrogel. Incorporating

two full strands of Aβ15–23 into a macrocycle

without a template designed to block aggregation appeared to give

a peptide that was highly amyloidogenic. To reduce the amyloidogenicity

of the macrocycle, we prepared macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3, which incorporates a single Hao amino acid in place of

the F19′F20′A21′ tripeptide segment of macrocyclic β-sheet 2,

to give an Aβ15–23 hybrid strand. To facilitate

phase determination through single anomalous dispersion (SAD) phasing,

we incorporated p-iodophenylalanine (FI) in place of F20 in the Aβ15–23 peptide strand.

Here, we report the X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet 3. We compare the solid-state supramolecular assembly to that of the oligomer observed in solution. We describe a new mode of assembly of Aβ15–23 in the solid state—a fibril-like assembly of oligomers—that resembles both fibrils and oligomers.

Results

X-ray Crystallographic Structure of Macrocyclic β-Sheet 3

In the solid state, macrocyclic β-sheet 3 forms hydrogen-bonded dimers arranged in a herringbone fashion in offset layers that pack through hydrophobic interactions. The resulting supramolecular assembly differs substantially both from that which we have observed previously for macrocyclic β-sheets 1(8,9) and that which others have previously observed for Aβ.

Macrocyclic β-sheet 3 readily formed crystals under sparse-matrix screening conditions with kits from Hampton Research. Crystals suitable for X-ray crystallography were grown from a 3.5 mg/mL solution with 0.1 M sodium citrate at pH 7.3, 0.1 M ammonium acetate, and 30% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol. Crystal diffraction data were collected on beamline 7-1 at the Stanford Synchotron Radiation Lightsource (SSRL) at 1.00 Å wavelength to 1.75 Å resolution. Data were integrated and scaled with XDS12 and merged with Aimless.13 Iodine locations were determined with HySS in the PHENIX software suite.14 Initial density maps and phasing were generated with Autosol. Alternating rounds of manual rebuilding with Coot15 and refinement with phenix.refine were performed. The structure was solved in the C2 space group with 49% pseudomerohedral twinning16 to give a model with Rfree = 22.0% and Rwork = 17.9% (Table 1). The asymmetric unit contains two molecules of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 and two molecules of 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol.

Table 1. X-ray Crystallographic Data Collection and Refinement Statistics for Macrocyclic β-Sheet Peptide 3.

| Crystal parameters | |

| space group | C2 |

| a, b, c (Å) | 32.174, 62.852, 20.094 |

| α, β, γ (deg) | 90.00, 89.98, 90.00 |

| molecules per asymmetric unit | 2 |

| Data collection | |

| synchrotron beamline | SSRL beamline 7–1 |

| wavelength (Å) | 1.00 |

| resolution (Å) | 17.56–1.75 (1.81–1.75) |

| total reflectionsa | 14845 (1450) |

| unique reflectionsa | 4060 (398) |

| completeness (%)a | 99.2 (97.1) |

| multiplicitya | 3.7 (3.6) |

| Rmerge (%)a,b | 3.6 (6.3) |

| CC1/2 (%)a | 99.8 (99.6) |

| CC* (%)a | 100 (99.9) |

| I/σ(I)a | 25.4 (13.4) |

| Refinement | |

| resolution (Å) | 1.75 |

| Rwork (%)c | 17.9 |

| Rfree (%)d | 22.0 |

| RMS bond lengths (Å) | 0.010 |

| RMS bond angles (deg) | 1.52 |

| ligands | 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol (2) |

| water | 43 |

| Ramachandran favored (%) | 100 |

| Ramachandran outliers (%) | 0 |

| Wilson B-factor (Å2) | 18.5 |

| average B-factor (Å2) | 22.6 |

| twinning | –h, −k, l (α = 0.49) |

Statistics for the highest resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Rmerge = ∑|I – ⟨I⟩|/∑I.

Rwork = ∑|Fobs – Fcalc|/∑Fobs.

Rfree was computed as Rwork using a cross-validation set of 10% nonredundant data.

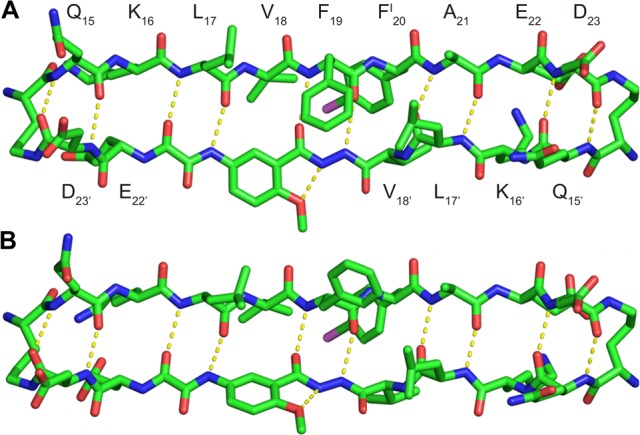

Macrocyclic β-sheet 3 crystallizes as a folded monomer in which the Aβ15–23 peptide strand and the Aβ15–23 hybrid strand form a hydrogen-bonded β-sheet. Two conformers of the macrocycle occur in the asymmetric unit, differing in rotamer of F19 and tilt of the Hao amino acid. The conformers alternate in the crystal lattice, geared together through crystal packing. Figure 1 illustrates the structure of the two conformers of the macrocycle.

Figure 1.

X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3. Two conformers (A and B) make up the asymmetric unit.

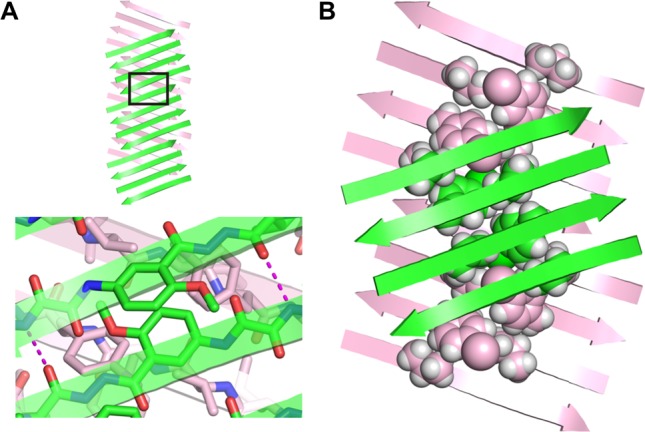

Macrocyclic β-sheet 3 forms a hydrogen-bonded dimer, in which the two conformers hydrogen bond to form a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet. The Aβ15–23 peptide strands of the macrocycles make up the dimerization interface and are fully aligned, with residues 15–23 of one of the macrocycles paired with residues 23–15 of the other through eight hydrogen bonds. The side chains of residues Q15, L17, F19, A21, and D23 of the Aβ15–23 peptide strands and Q15′, L17′, and D23′ of the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands decorate one of the surfaces of the four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet dimer; the side chains of residues K16, V18, FI20, and E22 of the Aβ15–23 peptide strands and K16′, V18′, and E22′ of the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands decorate the other surface. Figure 2 illustrates the structure of the hydrogen-bonded dimer and the two surfaces. We term the two surfaces the LFA face and the VF face for the discussion of the higher-order supramolecular assembly of the dimers that follows.

Figure 2.

X-ray crystallographic structure of the hydrogen-bonded dimer of macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3. (A) Cartoon illustration of the hydrogen-bonded dimer. (B) The LFA face of the hydrogen-bonded dimer, bearing the side chains of residues Q15, L17, F19, A21, and D23 of the Aβ15–23 peptide strands and Q15′, L17′, and D23′ of the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands. (C) The VF face of the hydrogen-bonded dimer, bearing the side chains of residues K16, V18, FI20, and E22 of the Aβ15–23 peptide strands and K16′, V18′, and E22′ of the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands.

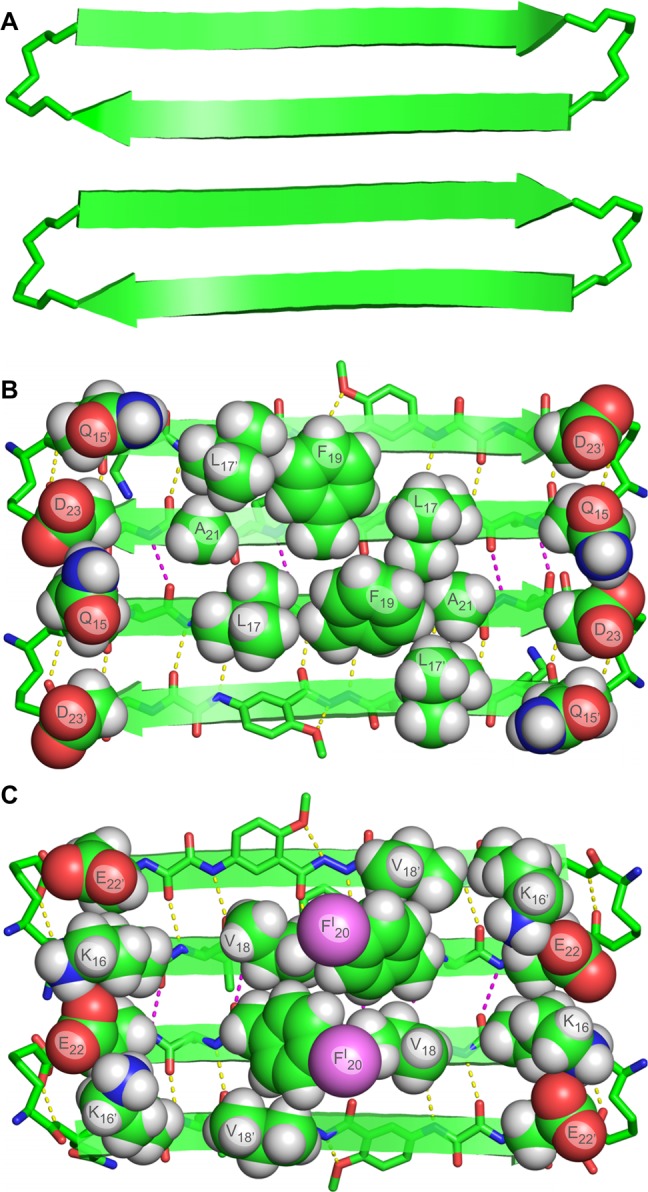

The hydrogen-bonded dimers assemble to form an extended β-sheet that runs the length of the crystal lattice. The Aβ15–23 hybrid strands form the interfaces between the dimers. At the interfaces, the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands are not fully aligned, but rather are shifted out of alignment by two residues toward the C-termini. As a result of the shift in alignment, the β-strands comprising the β-sheets are not orthogonal to the axis formed by the extended β-sheet, but rather are rotated approximately 20° from orthogonality. The resulting assembly of the dimers resembles a herringbone pattern. Figure 3A illustrates the assembly of the hydrogen-bonded dimers.

Figure 3.

Assembly of hydrogen-bonded dimers in the X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3. (A) Extended β-sheet that runs the length of the crystal lattice. (B) Packing of the extended β-sheets to form a two-layered structure.

The extended β-sheets formed by the hydrogen-bonded dimers pack through the VF faces to form a two-layered structure. The dimers comprising each layer do not overlap directly. Instead, each dimer in one layer sits over the interface between two dimers in the opposite layer. Figure 3B illustrates the packing of the two layers.

The Hao amino acids come together at the interface between the hydrogen-bonded dimers, tilting alternately upward and downward and stacking to accommodate hydrogen-bonding interactions between the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands.17 Figure 4A illustrates the interaction between the Hao amino acids at the interface. The side chains of the V18, FI20, and V18′ residues create a hydrophobic core that runs along the axis formed by the extended β-sheet. Figure 4B illustrates the structure of the hydrophobic core. The stacked Hao amino acids and the iodine of FI20 help fill the void created by the absence of F20′ in the Aβ15–23 hybrid strand. The 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol solvent that crystallizes with macrocyclic β-sheet 3 packs alongside the hydrophobic core and further stabilizes the two-layered structure through additional hydrophobic interactions.

Figure 4.

(A) Interaction between the Hao amino acids at the interface between dimers in the X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3. (B) Hydrophobic core formed by the side chains of the V18, FI20, and V18′ residues, between the layers of the extended β-sheets in the X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet 3.

Solution-State Studies of Macrocyclic β-Sheets 3–6

In aqueous solution, macrocyclic β-sheet 3 forms discrete tetramers comprising a sandwich formed by two hydrogen-bonded dimers. The solution-state tetramer is similar in structure to that which we have previously observed for macrocyclic β-sheets 1.9 The dimer subunits form through hydrogen bonding between the Aβ15–23 peptide strands, with the β-strands shifted out of alignment by two residues toward the C-termini. The dimer subunits assemble to form the tetramer through hydrophobic interactions between the LFA faces.

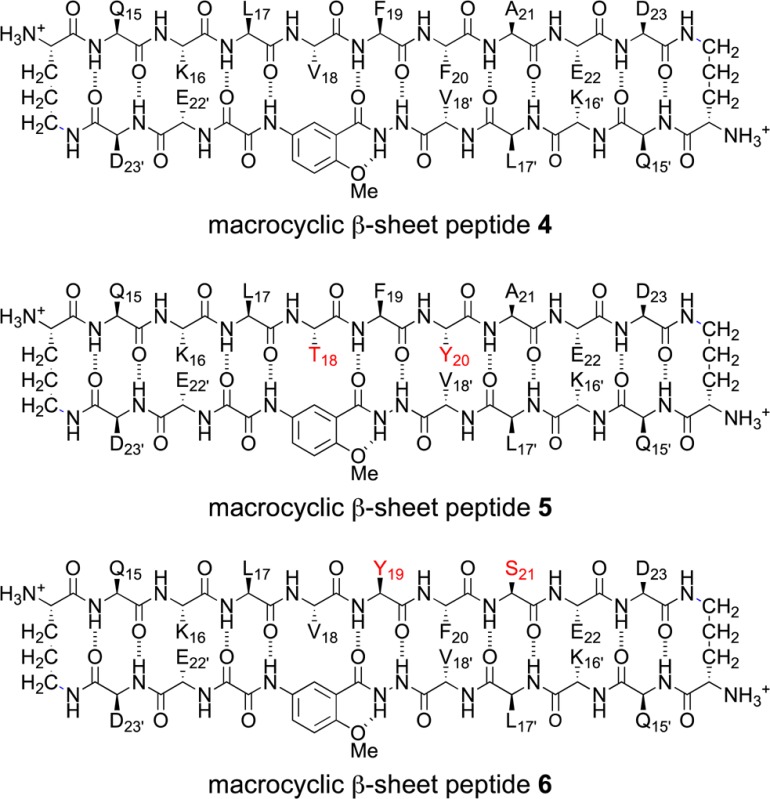

We studied the

folding and supramolecular assembly of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 and homologues 4, 5, and 6 by 1H NMR NOESY and DOSY experiments on the trifluoroacetate

(TFA) salts in D2O solution. Macrocyclic β-sheet 4 is a homologue of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 with phenylalanine in place of p-iodophenylalanine

in the Aβ15–23 peptide strand (F20 in place of FI20). Macrocyclic β-sheet 5 is a double mutant in which the hydrophobic residues V18 and F20 in the Aβ15–23 peptide strand are rendered more hydrophilic by hydroxylation: V18 is replaced by threonine and F20 is replaced

by tyrosine (V18T,F20Y). Macrocyclic β-sheet 6 is another double mutant in which the hydrophobic residues

F19 and A21 in the Aβ15–23 peptide strand are rendered more hydrophilic by hydroxylation: F19 is replaced by tyrosine and A21 is replaced by

serine (F19Y,A21S).

1H NMR studies establish that macrocyclic β-sheets 3, 4, and 5 form tetramers comprising hydrogen-bonded dimer subunits at low millimolar concentrations.18 The three macrocycles exhibit 1H NMR spectra with similar features (Figure S1). All three macrocycles show downfield shifting of the α-protons characteristic of β-sheet structure, magnetic anisotropy of the δ-linked ornithine pro-R and pro-S δ-protons characteristic of well-defined turn structures,10 and upfield shifting of the F19 aromatic resonances characteristic of tertiary and quaternary structure (Figures S1–S2, Table S1).19 In contrast, macrocyclic β-sheet 6 is monomeric at low millimolar concentrations and is less well folded than macrocyclic β-sheets 3–5, exhibiting less downfield shifting of the α-protons and less magnetic anisotropy of the δ-linked ornithine pro-R and pro-S δ-protons (Figure S1).20

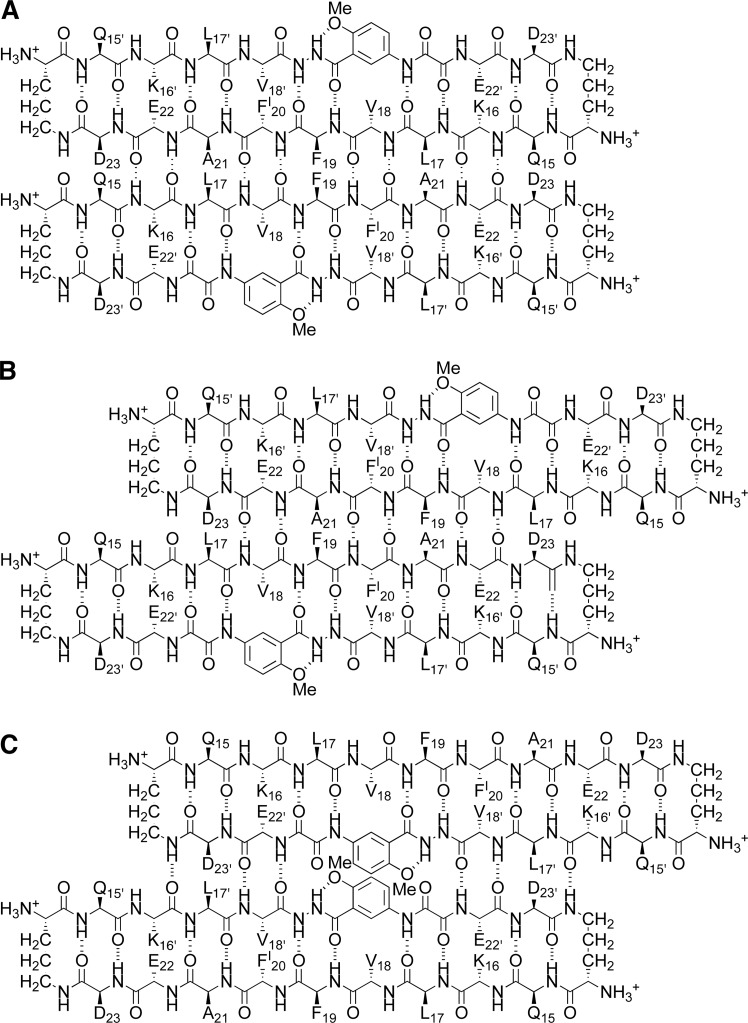

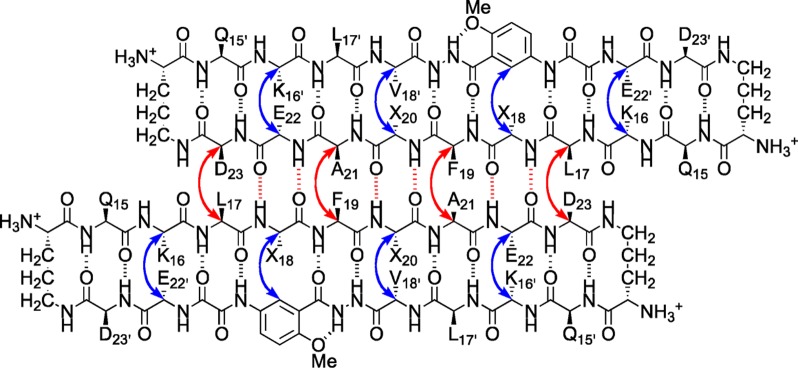

In the NOESY spectra, macrocyclic β-sheets 3, 4, and 5 exhibit a rich array of NOE crosspeaks associated with folding and dimerization (Figures S3–S5). The macrocycles exhibit key NOEs between α-protons associated with folding: K16 and E22′; V18 or T18 and the proton at the 6-position of the Hao residue; F20I, F20, or Y20 and V18′; and E22 and K16′. The macrocycles also exhibit key NOEs between α-protons associated with dimerization: L17 and D23; and F19 and A21. Table 2 summarizes the key NOEs observed for each macrocycle; Figure 5 illustrates the structures of the dimers.

Table 2. Key NOEs Observed for Peptides 3, 4, and 5a.

| peptide | K16–E22′b | X18–Hao6 | X20–V18′ | E22–K16′b | L17–D23b | F19–A21b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | obsc | obs | obs | –c,d | obs | –d |

| 4 | obs | obs | obs | obs | obs | obs |

| 5 | obs | obs | obs | obs | obs | obs |

500 MHz NOESY spectra at 2.0 mM in D2O at 298 K.

Assignments of K16 vs K16′, L17 vs L17′, E22 vs E22′, and D23 vs D23′ are inferred from the observed pattern of NOEs.

Assignment of K16–E22′ vs E22–K16′ is arbitrary.

NOEs not observed due to overlap of the resonances. (3: X18 = V, X20 = FI; 4: X18 = V, X20 = F; 5: X18 = T, X20 = Y)

Figure 5.

Hydrogen-bonded dimers formed by macrocyclic β-sheet peptides 3–5 in aqueous solution. Key NOEs associated with dimerization and folding are shown with red and blue arrows. (3: X18 = V, X20 = FI; 4: X18 = V, X20 = F; 5: X18 = T, X20 = Y).

DOSY studies show that the hydrogen-bonded dimers are subunits of tetramers, which are the stable species in aqueous solution.18,19,21,22 In the DOSY spectra macrocyclic β-sheets 3, 4, and 5 exhibit diffusion coefficients of 10.1–10.7 × 10–7 cm2/s (Table 3). These values are comparable to those that we have observed previously for similar tetramers and are 0.58–0.61 times smaller than that of macrocyclic β-sheet 6, which is monomeric.9,23,24

Table 3. Diffusion Coefficients (D) of Peptides 3–6 at 2.0 mM in D2O at 298 K.

| peptide | MWmonomera (Da) | MWtetramera (Da) | D (10–7 cm2/s) | oligomer state |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 2380 | 9522 | 10.1 | tetramer |

| 4 | 2254 | 9018 | 10.3 | tetramer |

| 5 | 2272 | 9090 | 10.7 | tetramer |

| 6 | 2286 | NA | 17.4 | monomer |

Molecular weight calculated for the neutral (uncharged) macrocycle.

The tetramer forms as a sandwich of hydrogen-bonded dimers. It is sandwiched through the hydrophobic face that displays L17, F19, and A21, and these residues help create the hydrophobic core of the tetramer (Figure 6). When F19 and A21 are rendered hydrophilic by hydroxylation in macrocyclic β-sheet 6, the hydrophobic core cannot form and the tetramer is disrupted.9 In contrast, when V18 and F20 are rendered hydrophilic by hydroxylation in macrocyclic β-sheet 5, the hydrophobic core is unaffected and the tetramer is not disrupted.

Figure 6.

Illustration of the tetramer formed by macrocyclic β-sheet peptides 3–5 in aqueous solution. The tetramer forms as a sandwich-like assembly of two hydrogen-bonded dimers, sandwiched through the LFA faces (3: X18 = V, X20 = FI; 4: X18 = V, X20 = F; 5: X18 = T, X20 = Y).

Discussion

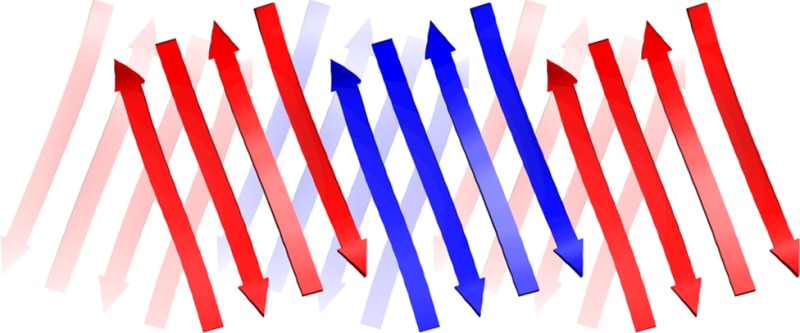

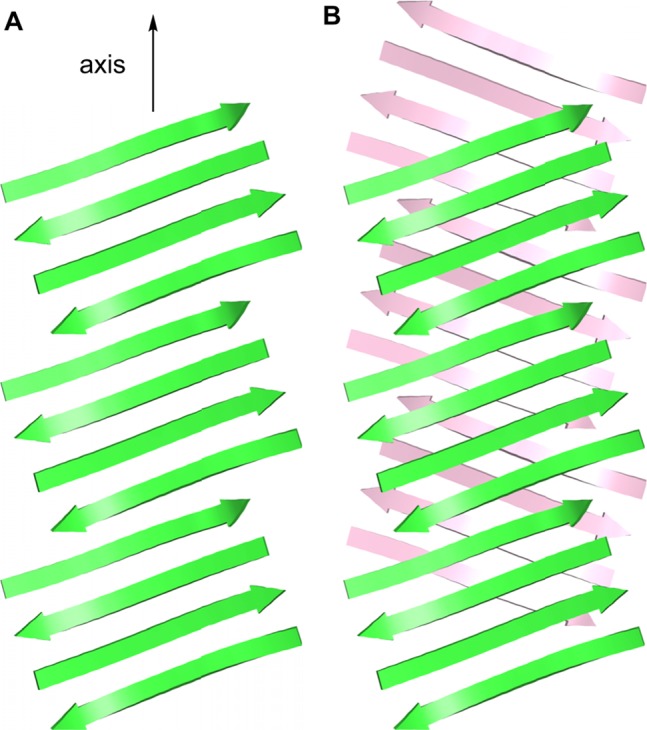

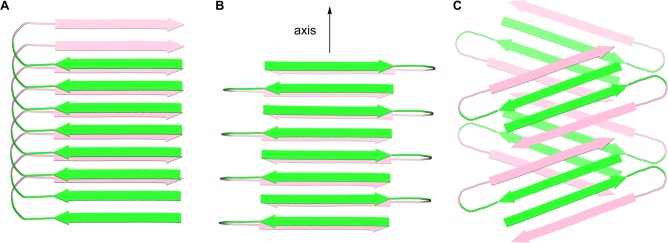

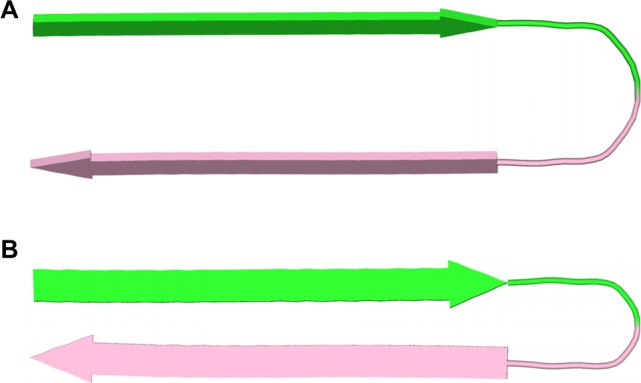

The extended layered β-sheet formed by the hydrogen-bonded dimers of 3 (Figure 3B) resembles the structures of amyloid fibrils.25,26 Amyloid fibrils consist of extended β-sheets composed of networks of hydrogen-bonded β-strands running the length of the fibril axis and laminated in pairs through hydrophobic interactions to form two-layered assemblies.2 In the fibrils formed by Aβ1–40, the hydrophobic central and C-terminal regions of the peptide assemble to form extended β-sheets that run the length of the fibril axis. The β-strands comprising the β-sheets are roughly orthogonal (90°) to the fibril axis. The molecules of Aβ form U-shaped turns, and the hydrophobic central and C-terminal β-strands pack in a face-to-face fashion through hydrophobic interactions. The resulting two-layered β-sheets make up the basic fibril structure, further assembling to form four-layered or triangular fibrils consisting of two or three of these subunits. Although most of the structures reported for Aβ1–40 fibrils involve parallel β-sheets, antiparallel β-sheets have been reported for Iowa mutant β-amyloid fibrils.27 Figure 7A,B illustrates the structures of the parallel and antiparallel two-layered β-sheets reported for Aβ1–40. Figure 8A illustrates the structure of the component U-shaped turns that make up these two-layered assemblies.

Figure 7.

Cartoon representations of fibrils formed by Aβ. (A) Parallel β-sheet fibril composed of U-shaped turns in a staggered arrangement, observed for Aβ1–40.2c (B) Antiparallel β-sheet fibril composed of U-shaped turns, observed for the Iowa mutant Aβ1–40.27 (C) Fibril-like assembly of oligomers composed of β-hairpins, that we propose from the X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3. The green and pink colors represent the central and C-terminal regions of Aβ.

Figure 8.

Cartoon representations of U-shaped turns (A) and β-hairpins (B) composed of Aβ. In the U-shaped turns, the faces of the β-strands pack together.2c,27 In the proposed β-hairpins, the edges of the β-strands hydrogen bond together. The green and pink colors represent the central and C-terminal regions of Aβ.

The assembly formed by the hydrogen-bonded dimers of 3 (Figure 3B) differs notably from amyloid fibrils in that it is composed of discrete oligomeric subunits. While the two-layered β-sheets of the Aβ1–40 fibrils contain no subunit larger than the monomer, the fibril-like assemblies formed by macrocyclic β-sheet 3 are composed of oligomers consisting of two β-hairpin-like macrocycles, hydrogen bonded to form a four-stranded antiparallel β-sheet.

The X-ray crystallographic structure of the fibril-like assembly of oligomers formed by macrocyclic β-sheet 3 suggests that alternative fibril assemblies of Aβ1–40 or Aβ1–42 might also be possible.25,26 In a fibril-like assembly of oligomers formed by full-length Aβ, the hydrophobic central and C-terminal regions of the peptide could hydrogen bond to form a β-hairpin.28 The β-hairpins could then further assemble to form layered β-sheets through edge-to-edge hydrogen bonding and face-to-face hydrophobic interactions. In this assembly, the β-strands comprising the β-sheets are not orthogonal to the fibril axis, but rather are rotated approximately 20° from orthogonality. To compensate for this rotation, the β-sheets must shift registration by two residues for every two β-hairpins. Figure 7C illustrates a structure of this fibril-like assembly of oligomers; Figure 8B illustrates the structure of the component β-hairpins.

The solid-state and solution-state structures of macrocyclic β-sheets 3–5 show that Aβ15–23 can form both aligned and shifted antiparallel β-sheets. In the X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet 3, the Aβ15–23 peptide strand forms an aligned β-sheet, while the Aβ15–23 hybrid strand forms a shifted β-sheet. In the solution-state structure of macrocyclic β-sheets 3–5, the Aβ15–23 peptide strand forms a shifted β-sheet. Figure 9 illustrates these modes of supramolecular assembly.

Figure 9.

Interfaces between Aβ15–23 observed in the solid state and in solution. (A) Interface between monomer subunits within the dimer of macrocyclic β-sheet peptide 3 in the solid state. (B) Interface between monomer subunits within the dimer of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 in aqueous solution. (C) Interface between the dimers of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 in the solid state. In (A) and (B) the interface occurs between the Aβ15–23 peptide strands; in (C) the interface occurs between the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands.

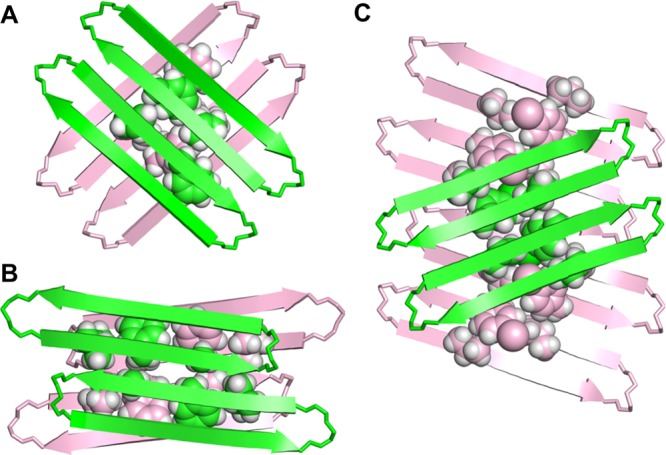

We have previously observed both aligned and shifted antiparallel β-sheets involving Aβ15–23 in the solid-state and solution-state structures of macrocyclic β-sheets 1. In the solid state, macrocyclic β-sheet 1a forms tetramers consisting of two hydrogen-bonded dimers sandwiched through the VF faces (Figure 10A).8 In these hydrogen-bonded dimers, the Aβ15–23 peptide strands are fully aligned. In aqueous solution, macrocyclic β-sheets 1a and 1b form tetramers consisting of two hydrogen-bonded dimers sandwiched through the LFA faces (Figure 10B).9 In these hydrogen-bonded dimers, the Aβ15–23 peptide strands are shifted out of alignment by two residues toward the C-termini. The fibril-like assembly of oligomers formed by macrocyclic β-sheet 3 differs from the solid-state and solution-state structures of macrocyclic β-sheets 1, in that it does not contain discrete tetramers. Instead, each dimer subunit overlaps with two dimers in the opposing layer (Figure 10C).

Figure 10.

Supramolecular assemblies of macrocyclic β-sheet peptides derived from Aβ15–23. (A) Tetramer of 1a observed in the solid state (PDB: 4IVH).8 (B) Tetramer of 1b (and 1a) observed in aqueous solution.9 (C) Fibril-like assembly of dimers of 3 observed in the solid state.

It is easy to imagine a mechanism, similar to crystallization, by which the fibril-like assemblies of oligomers catalyze oligomer formation.29 During crystal growth, the fibril-like oligomers of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 shown in Figure 3B must elongate by adding monomer subunits either one at a time or in small groups from tetramers or oligomers present in solution. A similar mechanism of growth can be hypothesized for the fibril-like assemblies of oligomers that we propose for full-length Aβ in Figure 7C, in which the exposed hydrogen-bonding edges and hydrophobic surfaces serve as a template that promotes the addition and folding of monomeric Aβ. The fibril-like assembly of oligomers can then serve as a reservoir of oligomers, dissociating organized dimers, tetramers, or other small homogeneous assemblies of soluble toxic amyloid oligomers. Such mechanisms for oligomer replication have been seen and discussed previously but have not been observed at atomic resolution.30 The X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 may thus provide a window at atomic resolution into a prion-like mechanism of amyloid oligomer propagation.

Conclusion

The X-ray crystallographic structure of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 provides new insights into the supramolecular assembly of peptides from β-amyloid, revealing a fibril-like assembly of hydrogen-bonded dimers. The dimers repeat along the fibril axis, to form an extended β-sheet, like in conventional amyloid fibrils. Unlike conventional amyloid fibrils, the β-strands comprising the β-sheets are rotated approximately 20° from orthogonality to the fibril axis, and a two-residue shift in alignment of the β-strands occurs at the juncture between the dimers. The β-sheets are layered and laminated through hydrophobic interactions. The dimers are not layered directly over each other, but rather are offset by two strands. As a result, the fibril-like assembly of dimers is not composed of discrete tetramers.

The fibril-like assembly of oligomers formed by macrocyclic β-sheet 3 offers the intriguing possibility that full-length Aβ may also be able to form similar assemblies, perhaps consisting of β-hairpins formed by the amyloidogenic central and C-terminal regions of Aβ. This model further suggests the provocative hypothesis that fibril-like assemblies of Aβ oligomers might catalyze Aβ oligomer formation and replication.

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health for grant support (5R01GM097562). J.D.P. thanks Dr. Nicholas Chim for helpful discussion of structure refinement. K.H.C. thanks Vertex Pharmaceuticals for support through the Vertex Scholars program. Use of the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, is supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under contract no. DE-AC02-76SF00515. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393).

Supporting Information Available

NMR spectra, mass spectra, and HPLC traces for macrocyclic β-sheet peptides 3–6. Crystallographic data in CIF and PDB format for macrocyclic β-sheet 3. The crystal structure of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 was deposited into the Protein Data Bank (PDB) with PDB code 4Q8D. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Hamley I. W. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 5147–5192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Benilova I.; Karran E.; De Stooper B. Nat. Neurosci. 2012, 15, 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Querfurth H. W.; LaFerla F. H. N N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 362, 329–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Larson M. E.; Lesné S. E. J. Neurochem. 2012, 192Suppl. 1125–139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Fändrich M. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 421, 427–440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Benzinger T. L.; Gregory D. M.; Burkoth T. S.; Miller-Auer H.; Lynn D. G.; Botto R. E.; Meredith S. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998, 95, 13407–13412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lührs T.; Ritter C.; Adrian M.; Riek-Loher D.; Bohrmann B.; Döbeli H.; Schubert D.; Riek R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2005, 102, 17342–17347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Petkova A. T.; Yau W.-M.; Tycko R. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 498–512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Paravastu A. K.; Leapman R. D.; Yau W.-M.; Tycko R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 18349–18354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e McDonald M.; Box H.; Bian W.; Kendall A.; Tycko R.; Stubbs G. J. Mol. Biol. 2012, 423, 454–461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Yu L.; Edalji R.; Harlan J. E.; Holzman T. F.; Lopez A. P.; Labkovsky B.; Hillen H.; Barghorn S.; Ebert U.; Richardson P. L.; Miesbauer L.; Solomon L.; Bartley D.; Walter K.; Johnson R. W.; Hajduk P. J.; Olejniczak E. T. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 1870–1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Cerf E.; Sarroukh R.; Tamamizu-Kato S.; Breydo L.; Derclaye S.; Dufrênes Y. V.; Narayanaswami V.; Goormaghtigh E.; Ruysschaert J.-M.; Raussens V. Biochem. J. 2009, 421, 415–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Chimon S.; Shaibat M. A.; Jones C. R.; Calero D. C.; Aizezi B.; Ishii Y. Nat. Struc. Mol. Bio. 2010, 14, 1157–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Streltsov V. A.; Varghese J. N.; Masters C. L.; Nuttall S. D. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 1419–1426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ma B.; Nussinov Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2002, 99, 14126–14131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tarus B.; Straub J. E.; Thirumalai D. J. Mol. Biol. 2005, 345, 1141–1156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Miller Y.; Ma B.; Nussinov R. Biophys. J. 2009, 97, 1168–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Ahmed M.; Davis J.; Aucoin D.; Sato T.; Ahuja S.; Aimoto S.; Elliott J. I.; van Nostrand W. E.; Smith S. O. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2010, 17, 561–567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Hilbich C.; Kisters-Woike B.; Reed J.; Masters C. L.; Beyreuther K. J. Mol. Biol. 1992, 228, 460–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wood S. J.; Wetzel R.; Martin J. D.; Hurle M. R. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 724–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Tjernberg L. O.; Callaway D. J. E.; Tjernberg A.; Hahne S.; Lilliehöök C.; Terenius L.; Thyberg J.; Nordstedt C. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 12619–12625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tjernberg L. O.; Näslund J.; Lindqvist F.; Johansson J.; Karlström A. R.; Thyberg J.; Terenius L.; Nordstedt C. J. Biol. Chem. 1996, 271, 8545–8548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Tjernberg L. O.; Lilliehöök C.; Callaway D. J. E.; Näslund J.; Hahne S.; Thyberg J.; Terenius L.; Nordstedt C. J. Biol. Chem. 1997, 272, 12601–12605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Soto C.; Kindy M. S.; Baumann M.; Frangione B. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996, 226, 672–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Findeis M. A.; Musso G. M.; Arico-Muendel C. C.; Benjamin H. W.; Hundal A. M.; Lee J. J.; Chin J.; Kelley M.; Wakefield J.; Hayward N. J.; Molineaux S. M. Biochemistry 1999, 38, 6791–6800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Balbach J. J.; Ishii Y.; Antzutkin O. N.; Leapman R. D.; Rizzo N. W.; Dyda F.; Reed J.; Tycko R. Biochemistry 2000, 39, 13748–13759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ishii Y.; Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6606–6607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Klimov D.; Thirumalai D. Structure 2003, 11, 295–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Petkova A. T.; Buntkowsky G.; Dyda F.; Leapman R. D.; Yau W. M.; Tycko R. J. Mol. Biol. 2004, 335, 247–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lu K.; Jacob J.; Thiyagarajan P.; Conticello V. P.; Lynn D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6391–6393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Mehta A. K.; Lu K.; Childers W. S.; Liang Y.; Dublin S. N.; Dong J.; Snyder J. P.; Pingali S. V.; Thiyagarajan P.; Lynn D. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 9829–9835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Liang Y.; Pingali S. V.; Jogalekar A. S.; Snyder J. P.; Thiyagarajan P.; Lynn D. G. Biochemistry 2008, 47, 10018–10026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Senguen F. T.; Lee N. R.; Gu X.; Ryan D. M.; Doran T. M.; Anderson E. A.; Nilsson B. L. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 486–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Senguen F. T.; Doran T. M.; Anderson E. A.; Nilsson B. L. Mol. BioSyst. 2011, 7, 497–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Colletier J.-P.; Laganowsky A.; Landau M.; Zhao M.; Soriaga A. B.; Goldschmidt L.; Flot D.; Cascio D.; Sawaya M. R.; Eisenberg D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011, 108, 16938–16943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Cheng P.-N.; Liu C.; Zhao M.; Eisenberg D.; Nowick J. S. Nat. Chem. 2012, 4, 927–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham J. D.; Chim N.; Goulding C. W.; Nowick J. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013, 135, 12460–12467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham J. D.; Demeler B.; Nowick J. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 5432–5442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowick J. S.; Brower J. O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 876–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowick J. S.; Chung D. M.; Maitra K.; Maitra S.; Stigers K. D.; Sun Y. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 7654–7661. [Google Scholar]

- Kabsch W. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 125–132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Evans P. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2006, 62, 72–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Evans P. R.; Murshudov G. N. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2013, 69, 1204–1214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; Adams P. D. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2003, 59, 1966–1973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Adams P. D.; Afonine P. V.; Bunkoczi G.; Chen V. B.; Davis I. W.; Echols N.; Headd J. J.; Hung L. W.; Kapral G. J.; Grosse-Kunstleve R. W.; McCoy A. J.; Moriarty N. W.; Oeffner R.; Read R. J.; Richardson D. C.; Richardson J. S.; Terwilliger T. C.; Zwart P. H. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 213–221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P.; Lohkamp B.; Scott W. G.; Cowtan K. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2010, 66, 486–501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen N. A.; Heine A.; de Prada P.; Redwan E.-R.; Yeates T. O.; Landry D. W.; Wilson I. A. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2002, 58, 2055–2059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- We were surprised to see this type of interaction between the Hao amino acids in the Aβ15–23 hybrid strands, having previously described it as “forbidden” (Figure 2B of reference (25b)). It thus appears that the Hao amino acid disfavors, but does not completely preclude, the formation of extended networks of β-sheets.

- Macrocyclic β-sheet 5 shows predominantly or wholly the tetramer in the 1H NMR spectrum at concentrations as low as 0.1 mM in D2O at 298 K.

- The 1H NMR spectra of macrocyclic β-sheets 3 and 4 are broader than that of 5, suggesting that while the tetramers predominate for all of these peptides, the tetramers formed by the more hydrophobic peptides 3 and 4 may participate in minor equilibria with additional tetramers that differ in structure or oligomers that differ in molecularity.

- Macrocyclic β-sheet 6 shows only monomer in the 1H NMR spectrum at 2.0 mM in D2O at 298 K but shows resonances for both monomer and oligomer at 8.0 mM.

- a Berger S.; Braun S.. 200 and More NMR Experiments: A Practical Course; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2004; pp 515–517. [Google Scholar]; b Findeisen M.; Berger S.. 50 and More Essential NMR Experiments; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2012; pp 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- a Altieri A. S.; Hinton D. P.; Byrd R. A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995, 117, 7566–7567. [Google Scholar]; b Johnson C. S. Progr. NMR Spectrosc. 1999, 34, 203–256. [Google Scholar]; c Yao S.; Howlett G. J.; Norton R. S. J. Biomol. NMR 2000, 16, 109–119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Cohen Y.; Avram L.; Frish L. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 520–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Cohen Y.; Avram L.; Evan-Salem T.; Slovak S.; Shemesh N.; Frish L. In Analytical Methods in Supramolecular Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Schalley C. A., Ed; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, 2012; 197–285. [Google Scholar]

- Khakshoor O.; Demeler B.; Nowick J. S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 5558–5569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Polson A. J. Phys. Colloid Chem. 1950, 54, 649–652. [Google Scholar]; b Teller D. C.; Swanson E.; DeHaen C. Methods Enzymol. 1979, 61, 103–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fibril-like assemblies of oligomers have been proposed and observed previously for other macrocyclic β-sheet peptides containing amyloidogenic peptide sequences:; a Liu C.; Sawaya M. R.; Cheng P.-N.; Zheng J.; Nowick J. S.; Eisenberg D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 6736–6744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Liu C.; Zhao M.; Jiang L.; Cheng P.-N.; Park J.; Sawaya M. R.; Pensalfini A.; Gou D.; Berk A. J.; Glabe C. G.; Nowick J. S.; Eisenberg D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 20913–20918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroud J. C.; Liu C.; Teng P. K.; Eisenberg D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 7717–7722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Qiang W.; Yau W.-M.; Tycko R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 4018–4029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Qiang W.; Yau W.-M.; Luo Y.; Mattson M. P.; Tycko R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012, 109, 4443–4448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Tjenberg L. O.; Tjenberg A.; Bark N.; Yuan S.; Ruzsicska B. P.; Bu Z.; Thyberg J.; Callaway D. J. E. Biochem. J. 2002, 366, 343–351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hoyer W.; Grönwall C.; Jonsson A.; Ståhl S.; Härd T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2008, 105, 5099–5104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sandberg A.; Luheshi L. M.; Söllvander S.; de Barros T. P.; Macao B.; Knowles T. P. J.; Biverstål H.; Lendel C.; Ekholm-Petterson F.; Dubnovitsky A.; Lannfelt L.; Dobson C. M.; Härd T. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2010, 107, 15595–15600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The fibril-like assemblies of oligomers of macrocyclic β-sheet 3 are largely isolated from each other in crystal lattice, separated by channels containing water. The crystallographic structure may thus provide a model for amyloid oligomers in solution.

- a Lansbury P. T. Jr.; Caughey B. Chem. Biol. 1995, 2, 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Petkova A. T.; Leapman R. D.; Guo Z.; Yau W.-M.; Mattson M. P.; Tycko R. Science 2005, 307, 262–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Cremades N.; Cohen S. I.; Deas E.; Abramov A. Y.; Chen A. Y.; Orte A.; Sandal M.; Clarke R. W.; Dunne P.; Aprile F. A.; Bertoncini C. W.; Wood N. W.; Knowles T. P.; Dobson C. M.; Klenerman D. Cell 2012, 149, 1048–1059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Soto C. Cell 2012, 149, 968–977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Shahnawaz M.; Soto C. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 11665–11676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Nussbaum J. M.; Schilling S.; Cynis H.; Silva A.; Swanson E.; Wangsanut T.; Tayler K.; Wiltgen B.; Hatami A.; Rönicke R.; Reymann K.; Hutter-Paier B.; Alexandru A.; Jagla W.; Graubner S.; Glabe C. G.; Demuth H.-U.; Bloom G. S. Nature 2012, 485, 651–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g Morales R.; Duran-Aniotz C.; Castilla J.; Estrada L. D.; Soto C. Mol. Psychiatry 2012, 17, 1347–1353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Watts J. C.; Condello C.; Stöhr J.; Oehler A.; Lee J.; DeArmond S. J.; Lannfelt L.; Ingelsson M.; Giles K.; Prusiner S. B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 10323–10328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Stöhr J.; Condello C.; Watts J. C.; Bloch L.; Oehler A.; Nick M.; DeArmond S. J.; Giles K.; DeGrado W. F.; Prusiner S. B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2014, 111, 10329–10334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.