Abstract

Mediator complex is a molecular hub integrating signaling, transcription factors, and RNA polymerase II (RNAPII) machinery. Mediator MED23 is involved in adipogenesis and smooth muscle cell differentiation, suggesting its role in energy homeostasis. Here, through the generation and analysis of a liver-specific Med23-knockout mouse, we found that liver Med23 deletion improved glucose and lipid metabolism, as well as insulin responsiveness, and prevented diet-induced obesity. Remarkably, acute hepatic Med23 knockdown in db/db mice significantly improved the lipid profile and glucose tolerance. Mechanistically, MED23 participates in gluconeogenesis and cholesterol synthesis through modulating the transcriptional activity of FOXO1, a key metabolic transcription factor. Indeed, hepatic Med23 deletion impaired the Mediator and RNAPII recruitment and attenuated the expression of FOXO1 target genes. Moreover, this functional interaction between FOXO1 and MED23 is evolutionarily conserved, as the in vivo activities of dFOXO in larval fat body and in adult wing can be partially blocked by Med23 knockdown in Drosophila. Collectively, our data revealed Mediator MED23 as a novel regulator for energy homeostasis, suggesting potential therapeutic strategies against metabolic diseases.

Keywords: FOXO1, liver Med23-knockout mice, gluconeogenesis, insulin resistance, obesity, diabetes

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is a worldwide epidemic that affects more than 315 million people1,2. Obesity, impaired glucose metabolism and dyslipidemia are the main features of this pathology, all of which are closely related to insulin resistance and a high risk of cardiovascular disease3,4. The liver plays a central role in energy homeostasis mainly through several insulin-mediated events. Thus, multiple signaling pathways orchestrate distinctive gene expression programs that control hepatic energy metabolism. In the fed state, insulin normalizes blood glucose levels by increasing glucose uptake in peripheral tissues, such as skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, and by suppressing gluconeogenesis in the liver. In addition to carbohydrate metabolism, insulin regulates lipid metabolism by promoting lipid synthesis and inhibiting lipid degradation5. Much of this metabolic regulation occurs at gene expression level, which is subject to sophisticated signaling and transcriptional control6,7.

A key transcription cofactor is the highly conserved Mediator complex, which has multiple subunits and is involved in various biological processes by transmitting information between gene-specific transcription factors and RNA polymerase II (RNAPII)8,9,10. In addition to its classic recruitment role in RNAPII preinitiation complex assembly, Mediator is a critical complex at multiple post-recruitment steps, such as the transition of RNAPII from pause to elongation as well as transcription termination11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19. The Mediator complex also participates in the regulation of chromatin architecture20, epigenetic silencing21, and mRNA processing22.

Recent studies have revealed that specific interactions between transcription factors and several well-defined Mediator subunits control a wide range of physiological functions; however, the functions and mechanisms of the Mediator complex in the development of different metabolic diseases remain to be elucidated. We recently reported that the Mediator subunit MED23 serves as a critical link in transducing insulin signaling to the transcriptional cascade during adipocyte differentiation23 and that Med23 deficiency facilitates smooth muscle cell differentiation while suppressing adipogenesis24. Given that muscle and adipose tissue are deeply engaged in fuel metabolism, we hypothesized that MED23 may play an important role in the regulation of energy homeostasis. Since the liver is a major organ in the regulation of energy homeostasis, in the present study, we generated a liver-specific Med23-knockout (LMKO) mouse. Using this model, we observed that hepatic MED23 is crucially involved in glucose and lipid metabolism and in the development of diet-induced obesity. Furthermore, we found that acute ablation of hepatic Med23 in a diabetic mouse model was effective in reversing insulin resistance and its consequences. These findings reveal a novel role for the Mediator complex in the regulation of metabolic gene transcription and suggest MED23 as a potential target to treat pathologies underlying insulin resistance states, including T2D, obesity and metabolic syndrome.

Results

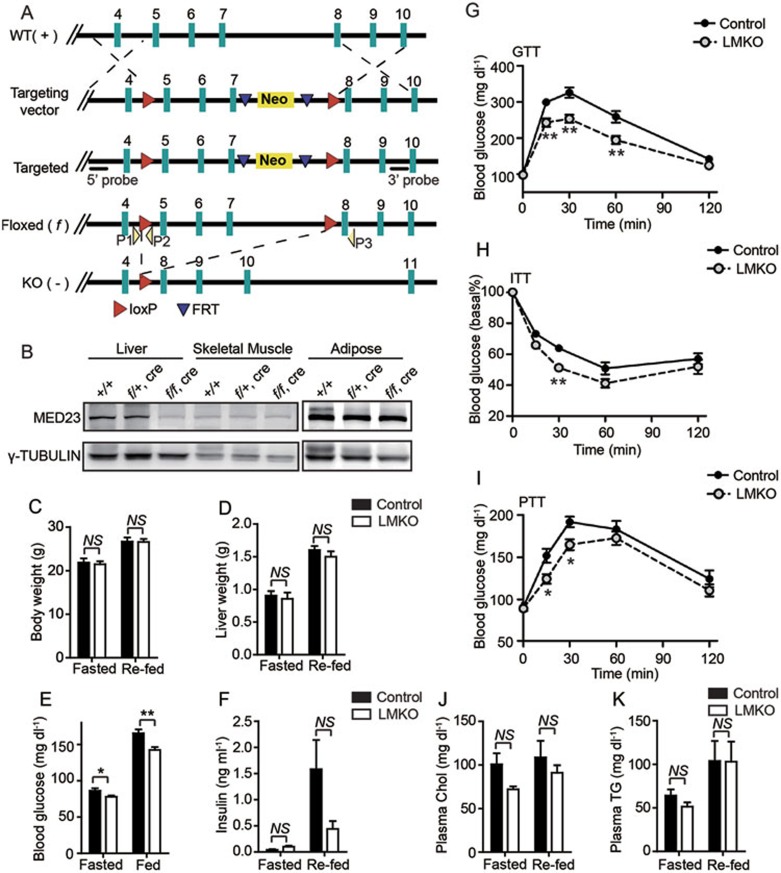

Establishment of LMKO mice

To investigate the role of MED23 in energy homeostasis, we first generated a conditional Med23-knockout mouse (Med23flox) with LoxP sites flanking exons 5-7 of Med23 allele (Figure 1A). LMKO mice (Albumin-Cre/Med23flox/flox) were obtained by crossing Med23flox/flox mice with mice that expressed Cre recombinase driven by the Albumin promoter (Supplementary information, Figure S1A). Deletion of LoxP-flanked exons generates a stop codon before exon 8. Littermate Med23flox/flox mice were used as controls. LMKO and control mice were born in accordance with Mendelian ratio. LMKO mice were barely distinguishable and showed unchanged fertility compared with control mice. Immunoblot confirmed specific and efficient Med23 deletion in the liver of LMKO mice but not in skeletal muscle or adipose tissue (Figure 1B). Histological analysis of LMKO livers suggested normal morphology (Supplementary information, Figure S1B), and analysis of albumin, aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) plasma levels suggested normal liver function of the LMKO mice (Supplementary information, Table S1). MED23 depletion did not affect the protein level of other Mediator subunits, such as CDK8 and MED1 (Supplementary information, Figure S1C). Moreover, we observed that MED6 could still be co-immunoprecipitated with CDK8, indicating that the core Mediator complex remained relatively stable (Supplementary information, Figure S1D). Previous experiments carried out in mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or stem cells have revealed that MED23, MED16, and MED24 form a stable sub-complex, and that the loss of Med23 can result in reduced levels of MED16 and MED24 in the Mediator complex25,26. Therefore, to assess the consequences of Med23 deletion in liver cells, we established a stable cell line with Med23 knockdown using the hepatic AML12 cells, and then we performed co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) experiments using CDK8 antibody. Interestingly, we found that deletion of Med23 in hepatic cells did not change MED16 content in the complex and resulted in a slight decrease of MED24 (Supplementary information, Figure S1E), evidencing that MED23 was the major component that was decreased in the liver of LMKO mice. On the other hand, knockdown of Med16 in AML12 cells resulted in a considerable decrease of MED23 and MED24 in the Mediator complex, suggesting that MED16 is the component responsible for connecting the sub-module to the Mediator complex.

Figure 1.

Establishment and functional analysis of LMKO mice. (A) The targeting strategy for Med23-conditional knockout mouse. (B) Immunoblot of MED23 in various tissues isolated from mice of different genotypes. (C-D) Body weight (C) and liver weight (D) in LMKO and control mice under fasted (24 h fast) and re-fed (24 h feeding following 24-h fast) states; n = 6 for each group. (E) Blood glucose measured under fasted (24 h fast) and random-fed states; n = 9 for each group. (F) Serum insulin levels under fasted (18 h fast) or re-fed (4 h feeding following 18-h fast) states. n = 6 for each group. (G-I) Glucose tolerance test (GTT; n = 10/group) (G), insulin tolerance test (ITT; n = 7/group) (H) and pyruvate tolerance test (PTT; n = 10/group) (I). Blood glucose levels were measured at the indicated times. The experiments were repeated at least three times during different days, showing similar results. (J-K) Cholesterol (Chol) (J) and triglyceride (TG) (K) levels under fasted (18 h fast) or re-fed (4 h feeding following 18-h fast) states. n = 6 for each group. For panel C-K, data are presented as mean ± SEM. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs control by Student's t-test.

Metabolic analysis in LMKO mice

To study the consequences of hepatic Med23 ablation, 8-12-week old LMKO and control mice were fasted for 24 h and were then fed chow diet for additional 24 h. There were no significant differences in body or liver weights between LMKO and control mice (Figure 1C and 1D). Body composition, including lean mass and fat mass measured by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), was comparable between LMKO and control mice (Supplementary information, Table S1). Fed and 24 h-fasting plasma glucose concentrations were lower in LMKO mice than those in controls (Figure 1E). Moreover, plasma insulin levels in the re-fed state tended to be lower in LMKO mice compared with controls (Figure 1F). These data suggested that LMKO mice would be more insulin responsive than the control mice. To evaluate the ability of the whole system in the glucose clearance, we tested the mice with glucose tolerance test (GTT). When challenged with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) glucose load, the LMKO mice showed a faster decline of plasma glucose levels compared to control mice (Figure 1G), indicating an enhanced glucose tolerance in LMKO mice. Insulin tolerance test (ITT) is a method to measure insulin sensitivity (IS) using blood glucose as a marker of systemic response, such as glucose utilization and suppression of gluconeogenesis, in response to i.p. insulin injection. LMKO mice showed more significant reduction of the blood glucose level at 30 min than controls (Figure 1H), indicating higher IS in response to insulin than controls. Pyruvate tolerance test (PTT) is a method to measure the hepatic gluconeogenesis after i.p. injection of pyruvate (a precursor for hepatic gluconeogenesis). Following pyruvate injection, LMKO mice showed lower blood glucose levels than controls (Figure 1I), indicating that the capacity of LMKO mice in converting pyruvate into glucose is less efficient than that of controls. In addition to alterations in glucose metabolism, serum triglyceride (TG) and total cholesterol (Chol) levels tended to decrease in LMKO mice after fasting (Figure 1J and 1K), whereas hepatic TG, Chol, and non-esterified fatty acid (NEFA) levels remained largely unchanged in LMKO mice compared with controls at both fasted and re-fed states (Supplementary information, Table S1). Taken together, these findings show that LMKO mice displayed enhanced glucose tolerance and IS, and subsequently an improved glucose and lipid profile.

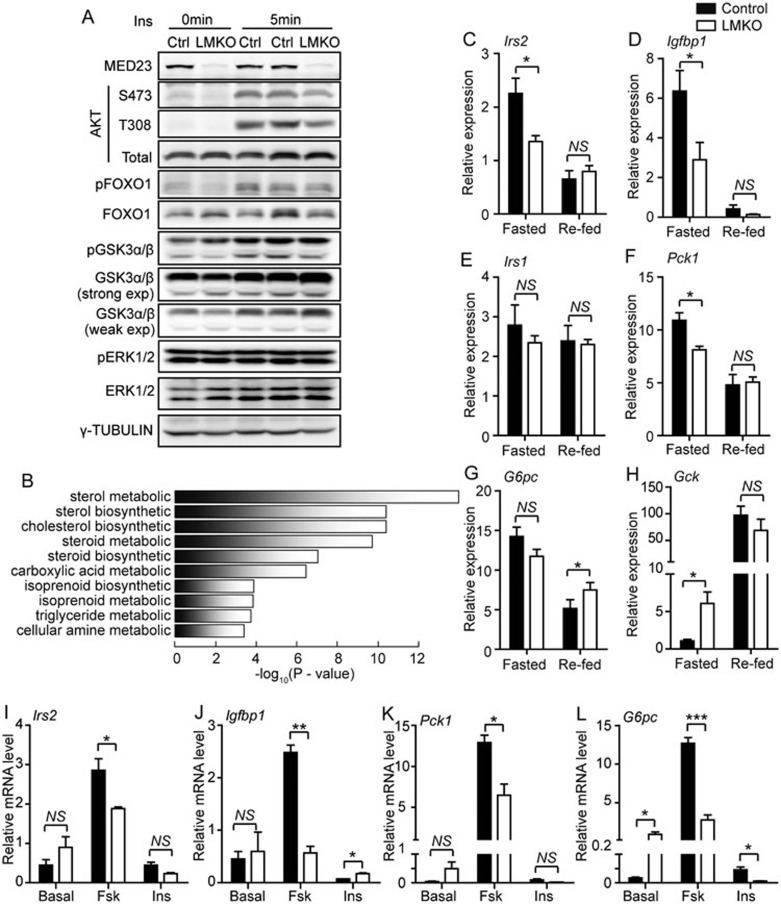

Analysis of insulin signaling and downstream target genes in LMKO mice

The enhanced IS observed in the LMKO mice led us to speculate that hepatic insulin signaling was improved in these mice. However, we did not find significant differences in AKT, GSK3α/β, FOXO1, or ERK phosphorylation between livers from LMKO and control mice after insulin injection (Figure 2A). Moreover, primary hepatocytes isolated from LMKO and control mice responded similarly when exposed to either insulin or glucagon (Supplementary information, Figure S2A and S2B). We then further analyzed the insulin/IRS/PI-3K/AKT downstream pathway, which could be responsible for the enhanced IS in LMKO mice. Considering MED23 as a transcription cofactor that may regulate gene expression at the transcriptional level, genome-wide mRNA expression profile of LMKO and control mouse livers was assessed using mRNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) method. About 492 genes were downregulated by ≥ 1.5-fold in LMKO mice compared with controls in the fasted condition and these genes were revealed to be associated with lipid, carboxylic acid, and amino acid metabolic processes by gene ontology (GO) analysis (Figure 2B), which was consistent with the phenotype observed in the LMKO mice. Using quantitative-PCR (Q-PCR), we confirmed that expression levels of several key genes involved in lipid and glucose metabolism were decreased in LMKO mice compared to controls (Supplementary information, Figure S2C). These results suggest that MED23 may be involved in the regulation of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism.

Figure 2.

Analysis of insulin signaling and downstream target genes in LMKO mice and primary hepatocytes. (A) Immunoblot of phosphorylated (p) or total AKT, FOXO1, GSK3α/β and ERK in LMKO and control livers. Overnight-fasted mice were injected with either saline or insulin (Ins, 1 U/kg). exp, exposure. Experiments and immunoblot assays were repeated independently three times and the results were consistent. (B) Gene ontology (GO) analysis of genes downregulated (fold change ≥ 1.5) in livers of LMKO mice fasted 24 h. (C-H) Q-PCR analysis of gene expression in livers of LMKO and control mice under fasted (18 h fast) or re-fed (4 h feeding following 18-h fast) states. n = 7 for each group under fasted states, n = 6 for control and n = 7 for LMKO under re-fed state. (I-L) Q-PCR analysis of gene expression in response to forskolin (3 h) or insulin (3 h) in control and LMKO primary hepatocytes. n = 3 for each well and experiments were repeated independently. For panel C-L, data are presented as mean ± SEM. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs control by Student's t-test.

Expression of FOXO1 target genes in liver was changed by hepatic Med23 ablation

In the liver, FOXO1 is one of the most important transcription factors regulating energy homeostasis targeted by insulin27. FOXO1 is active during fasting and is inhibited by insulin after feeding, which drives the nuclear exclusion of FOXO1 via Akt-dependent phosphorylation28,29. A liver-specific Foxo1-knockout mouse displays a lower level of plasma glucose and enhanced glucose tolerance primarily because of decreased gluconeogenesis30, which resembles the phenotype of LMKO mouse. To examine the potential interplay between FOXO1 and MED23, we identified 252 FOXO1 target genes in the mouse liver based on a previous report31 and found that these genes were markedly enriched within the set of differentially expressed genes in LMKO vs control mice after fasting (P = 10−14; Supplementary information, Figure S2D).

We observed that LMKO mice presented significantly decreased mRNA levels of the typical FOXO1 target genes such as insulin receptor substrate 2 (Irs2)32 and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 1 (Igfbp1)33,34 after fasting compared with control mice, as determined by Q-PCR (Figure 2C and 2D). Remarkably, this difference disappeared 4 h after re-feeding (Figure 2C and 2D), a physiological situation in which FOXO1 is excluded from the nucleus by the action of the insulin. In contrast, the expression level of Irs1, which is not a FOXO1 target gene, remained largely unchanged between LMKO and control mice disregarding the feeding status (Figure 2E). Similar to previous reports35,36, in the present study, IRS1 probably supports a relatively normal hepatic insulin signaling cascades when IRS2 is lost. Moreover, the expression levels of other FOXO1 target genes, including phosphoenol pyruvate carboxykinase (Pck1)34 and glucose-6-phosphatase (G6pc)37, which are key rate-limiting genes of gluconeogenesis, were also reduced in LMKO mice compared to controls after 18 h fasting, and the differences between LMKO and control mice were eliminated after re-feeding (Figure 2F and 2G). Interestingly, glucokinase (Gck) gene, which has been found to be negatively regulated by FOXO138, was upregulated in LMKO livers under fasting condition, while exhibiting indistinguishable increase between LMKO and control livers after re-feeding (Figure 2H). In addition, expression levels of Dhcr7, the enzyme regulating the last step of Chol formation39, and Trib1, the protein modulating the expression of lipogenic genes40, both of which were reported to have a FOXO1-binding site (IRE)31, were significantly decreased in LMKO livers compared with control livers under fasting state (Supplementary information, Figure S2C). These data suggest that liver Med23 deletion may partially impair FOXO1-driven gene expression, which are also consistent with the fact that the enhanced systemic IS was observed only in LMKO mice in the fasting but not in the fed state, when FOXO1 is inactivated.

Med23 ablation reduced FOXO1 target gene expression in primary hepatocytes

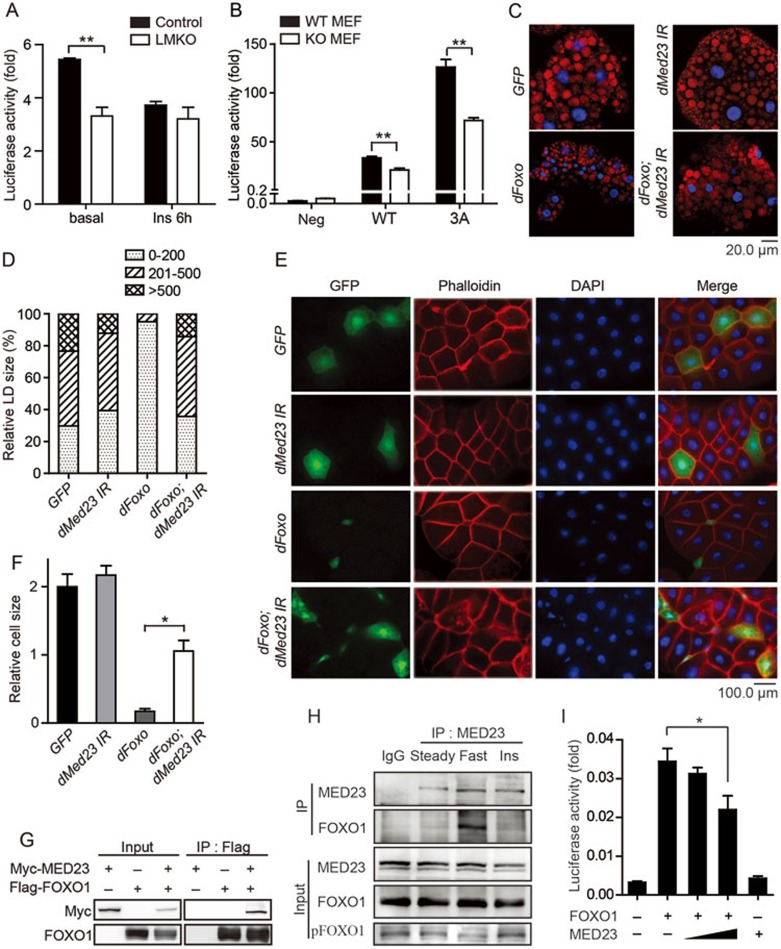

Since FOXO1 target genes can be stimulated by forskolin through mimicking the glucagon signaling pathway30,41, we further analyzed the FOXO1 target gene expression in LMKO and control primary hepatocytes. We found that the expression of Irs2, Igfbp1, Pck1 and G6pc was lower in LMKO primary hepatocytes than that in control cells upon forskolin treatment, confirming that MED23 plays a key role in controlling gluconeogenic gene expression (Figure 2I-2L). Consequently, glucose output was significantly decreased in isolated primary hepatocytes from LMKO mice compared with controls (Supplementary information, Figure S2E), which underlies the diminished glucose production that was observed during the PTT in the LMKO mice (Figure 1I). Furthermore, acute Med23 depletion in isolated Med23flox/flox primary hepatocytes using adenoviruses expressing Cre recombinase (Ad-cre), attenuated the response of FOXO1 target genes Pck1 and G6pc to forskolin (Supplementary information, Figure S2F-S2H), which also led to diminished glucose output (Supplementary information, Figure S2I). Reporter assays with a promoter reporter containing FOXO1-binding IRE sites revealed that the activity was decreased by about 50% in Med23-depleted primary hepatocytes compared with controls, suggesting the involvement of MED23 in the transcription regulation of FOXO1 target genes (Figure 3A). In addition, insulin stimulation abrogated this difference, most likely due to insulin-induced FOXO1 inactivation (Figure 3A). Moreover, the transcriptional activity of FOXO1 measured by GAL4-FOXO1 system (GAL4-DBD-FOXO1) was lower in Med23−/− MEFs compared to wild-type MEFs, and the activity of the constitutively active FOXO1 mutant GAL4-DBD-FOXO13A (with three alanine substitutions that inhibit Akt-mediated phosphorylation42) was also reduced in Med23−/− MEFs than in wild-type MEFs (Figure 3B). Collectively, these results suggest that MED23 is involved in gluconeogenesis by modulating FOXO1 transcription activity.

Figure 3.

Functional association of MED23 and FOXO1. (A) FOXO1-targeted reporter activity at basal level or with insulin (Ins) treatment in control and LMKO primary hepatocytes. (B) GAL4-FOXO1-driven reporter analysis in WT and Med23−/− (KO) MEFs. 3A: a constitutively active mutant of FOXO1, in which three amino acid residues responsible for phosphorylation were replaced with alanine. (C, D) Nile red staining (C) and quantification (D) of the effects of dFOXO overexpression and/or Med23 knockdown by ppl-Gal4 on the size of lipid droplets in the fat body in Drosophila. (E, F) Phalloidin staining (E) and quantification (F) of the effects of dFOXO overexpression and/or MED23 knockdown by act>CD2>Gal4 on the cell size in the fat body in Drosophila. (G) Co-IP of overexpressed MED23 with FOXO1. Myc-tagged MED23 and Flag-tagged FOXO1 was cotransfected into 293T cells. Whole-cell extract was used for immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody, followed by immunoblotting. (H) Co-IP experiments with anti-MED23 antibody in AML12 hepatocytes cultured in different mediums. “Steady” means cells were cultured steadily DMEM with 10% FBS (glucose: 4.5 g/L); “Fasted” means cells were starved for 12 h in serum-free low glucose medium (glucose: 1 g/L); “Ins” means 12 h fasted cells were stimulated with 100 nM insulin for 1 h. (I) FOXO1-targeted reporter activity was regulated by MED23 in AML12 hepatocytes. Each experiment was performed in triplicate and was repeated independently two times, obtaining similar results (A, B and I). Co-IP assays were repeated more than 3 times and the results were similar (G, H). For panel A, B, F and I, data are presented as mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, vs control by Student's t-test. For all the panels, absence of * or numbers indicates that the statistical analysis was non-significant.

Genetic interaction between dFOXO and MED23 in Drosophila

We next examined whether there is a genetic interaction between MED23 and dFOXO in Drosophila, which offers convenient tools for genetic manipulations. Drosophila fat body is functionally equivalent to mammalian liver and white adipose tissue (WAT), and is the main tissue for TG storage. Ectopically expressed dFOXO in the fat body resulted in significantly reduced size of lipid droplets (LDs). Although the knockdown of MED23 had no effect on the size of LDs, it partially blocked the effect of dFOXO on the size of LDs (Figure 3C and 3D). Using clonal analysis in the fat body, we could label individual cells overexpressing dFOXO. These cells, which were marked with the GFP fluorescence, had severely reduced size than the surrounding wild-type cells. Simultaneous knockdown of MED23 in these cells could partially reverse the effect of dFOXO on fat body cell size (Figure 3E and 3F). The functional interaction between dFOXO and MED23 could also be observed in other tissues. Ectopic expression of dFOXO in the region between the L3 and L4 longitudinal veins in the wing prevented formation of the anterior crossvein. Simultaneous knockdown of MED23 in this region partially rescued this phenotype (Supplementary information, Figure S3A and S3B). Together, these results reveal that dFOXO functions partly via MED23 in Drosophila, suggesting that the functional interaction between FOXO and MED23 is evolutionarily conserved.

MED23-dependent recruitment of Mediator and RNAPII at the FOXO1 target genes

We then characterized the functional interaction between MED23 and FOXO1 in mammalian cells. Interestingly, we found that overexpressed myc-tagged MED23 could be co-immunoprecipitated with flag-tagged FOXO1 in 293T cells (Figure 3G). Furthermore, endogenous FOXO1 can be pulled down efficiently by anti-MED23 antibody in AML12 hepatocytes cultured under fasting condition, while insulin addition eliminated the precipitated FOXO1 signal (Figure 3H). Unlike FOXO1, another key gluconeogenic transcription factor CREB43 failed to bind to MED23 in a co-IP experiment (Supplementary information, Figure S3C). We further probed the interaction between MED23 and FOXO1 with a reporter assay in AML12 cells. We observed that the overexpression of MED23 results in a decrease of the luciferase activity in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 3I). Presumably, the excessive monomeric MED23 could compete with the endogenous MED23 within the Mediator complex, thus impairing the recruitment of Mediator complex. Indeed, chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays with anti-CDK8 antibody revealed the reduced binding of Mediator to the promoters of FOXO1 target genes Igfbp1 and Pck1 in LMKO livers (Supplementary information, Figure S3D-S3E). Accordingly, RNAPII binding at the Pck1 and Igfbp1 coding regions was also attenuated in LMKO livers (Supplementary information, Figure S3F-S3G). These results suggest that the interaction between MED23 and FOXO1 is, at least in part, responsible for controlling the gluconeogenic gene expression in the liver.

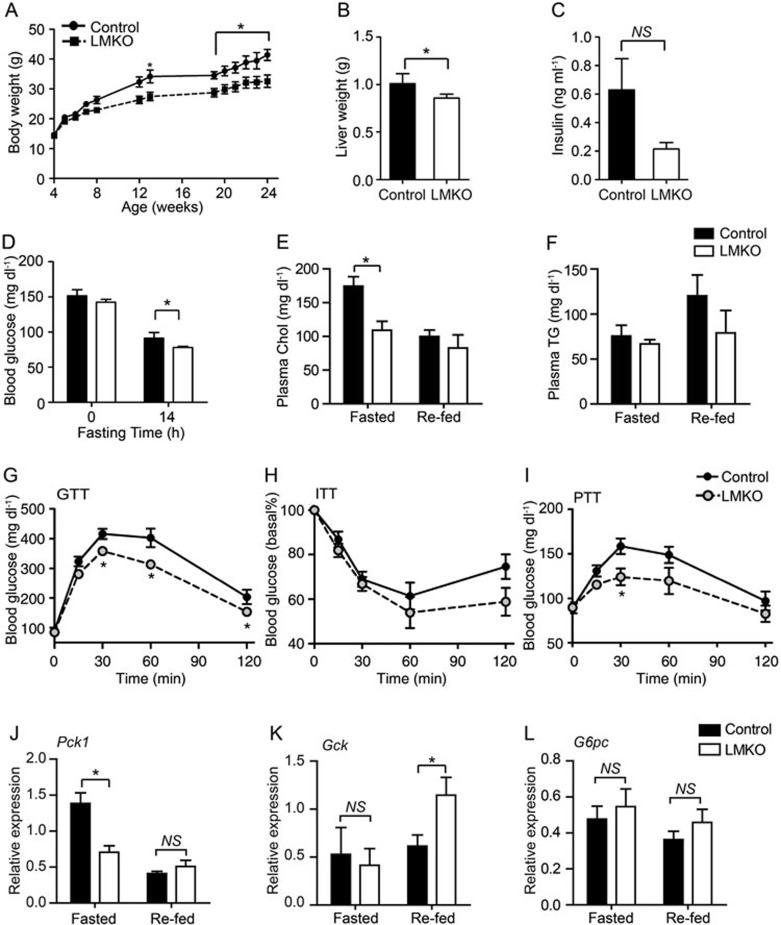

Hepatic deletion of Med23 improves glucose and lipid metabolism in HFD-fed mice

As chronic increases in hepatic gluconeogenesis and disrupted lipid metabolism contribute to the development of T2D, we examined whether LMKO mice were refractory to T2D development. LMKO and control mice were challenged with a high-fat diet (HFD) at the age of 4 weeks for 2 months. HFD is a very common treatment for inducing obesity. Mice fed with a HFD develop insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and impaired glucose metabolism, thus constituting an excellent model of T2D44. During HFD feeding, the LMKO mice were more resistant to HFD-induced obesity than control animals, as evidenced by lower body weight characterized by significantly decreased fat mass and liver weight (Figure 4A and 4B, Supplementary information, Table S2). Fasting glycaemia was decreased and plasma insulin levels were prone to be lower in LMKO animals vs controls (Figure 4C and 4D). Furthermore, LMKO mice showed reduced plasma Chol levels, but similar concentrations of adiponectin and leptin, as well as liver lipid contents at fasting state compared with those of control mice. On the other hand, plasma Chol levels at re-fed state, plasma TG and NEFA levels at both fasting and re-fed states were similar in LMKO and control mice (Figure 4E and 4F, Supplementary information, Table S2). In addition, LMKO animals exhibited increased glucose tolerance, enhanced IS, and decreased glucose production (Figure 4G-4I). We further analyzed the downstream target genes of FOXO1 in these mice. After 8 weeks under the HFD, the Pck1 mRNA level was significantly reduced in LMKO mice compared to controls after 18 h fasting, but the difference in gene expression could be eliminated after re-feeding (Figure 4J). Furthermore, Gck gene, which has been found to be negatively regulated by FOXO1, was upregulated in LMKO livers under re-feeding conditions, while showing a similar level to control livers during fasting state (Figure 4K). Finally, the expression level of G6pc was similar between control and LMKO mice in both fasting and re-feeding states (Figure 4L). Altogether, the above results revealed that the hepatic Med23 deletion protected mice from HFD-induced obesity and insulin resistance. Mechanistically, a few key gluconeogenic genes, targeted by FOXO1, exhibited reduced expression by hepatic Med23 deletion.

Figure 4.

Glucose and cholesterol homeostasis in control and LMKO mice under HFD condition. Control and LMKO mice were fed on HFD for 8 weeks starting at the age of 4 weeks. (A) Analysis of body weight changes during HFD feeding (n = 6 for control, n = 7 for LMKO). (B) Liver weight of LMKO and control mice (n = 5/group). (C) Plasma insulin level of LMKO and control mice under overnight fasted state (n = 5/group). (D) Blood glucose level at the indicated times (n = 6/group). (E) Plasma cholesterol level at both fasted (18 h) and re-fed (4 h) states (n = 6/group). (F) Plasma TG level at both fasted (18 h) and re-fed (4 h) states (n = 6/group). (G-I) Glucose tolerance test (GTT) (G), insulin tolerance test (ITT) (H) and pyruvate tolerance test (PTT) (I) (n= 6-9 per group). Blood glucose levels were meseasured at the indicated times. HFD feeding experiments were performed three times and results were similar. (J-L) Q-PCR analysis of gene expression in livers of LMKO and control mice fed on HFD for 8 weeks under fasted (18 h fast) and re-fed states. n = 4 for each group. For all the panels, data are presented as mean ± SEM. NS, not significant, *P < 0.05, vs control by Student's two-tailed t-test. For all the panels, absence of * or numbers indicates that the statistical analysis was non-significant.

Considering that the differences in body weight may confound the glucose and lipid metabolism in LMKO mice, we acutely deleted Med23 in the livers of HFD-fed control mice using the Ad-cre viruses. Med23 expression was reduced by 50% in the livers of Ad-cre mice compared with mice injected with adenoviruses expressing unspecific shRNA (Ad-ctrl mice) as determined by Q-PCR (Supplementary information, Figure S4A). Importantly, despite that both the liver and body weights were similar after Ad-cre or Ad-ctrl injection (Supplementary information, Figure S4B and S4C), Ad-cre mice still had decreased fed and fasting blood glucose levels (Supplementary information, Figure S4D) without alterations in plasma insulin levels, compared with Ad-ctrl mice (Supplementary information, Figure S4E). ALT and AST plasma levels were similar between mice injected with Ad-ctrl and Ad-cre (Supplementary information, Figure S4F), indicating similar level of liver damage in both groups. Importantly, mice that were injected with Ad-cre consistently featured an improved lipid profile as evidenced by lower fasting plasma Chol concentrations than controls (Supplementary information, Figure S4G). Ad-cre mice also demonstrated better glucose tolerance (Supplementary information, Figure S4H), less gluconeogenesis (Supplementary information, Figure S4I), and similar IS compared with Ad-ctrl mice (Supplementary information, Figure S4J).

Knockdown of Med23 in liver improves glucose and lipid homeostasis in db/db mice

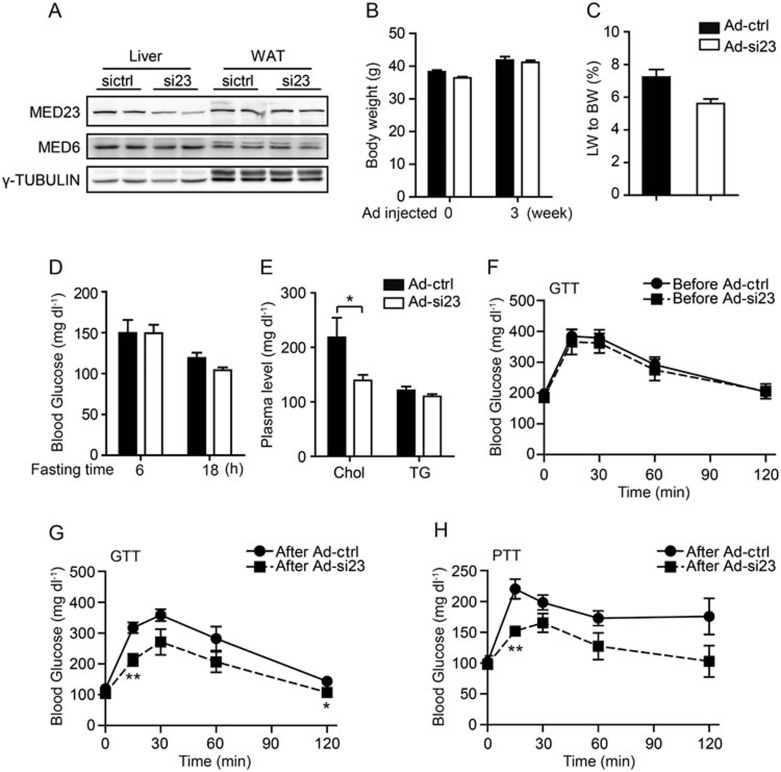

The significant role of MED23 in gluconeogenesis and Chol synthesis led us to speculate that acute liver deletion of Med23 could reverse the alterations associated with insulin resistance. Diabetic mouse (db/db) has been used as an animal model of T2D for many years45. Genetically, db/db mice were characterized by a G-to-T point mutation in Lepr (leptin receptor), which led to a defective leptin signal transduction46. The db/db mouse develops obesity, insulin resistance, hyperglycemia, and resistance to leptin. To test our hypothesis, we injected a group of db/db mice with adenoviruses expressing Med23 shRNA (Ad-si23) to specifically reduce hepatic MED23 expression. Importantly, MED23 expression in WAT was not affected (Figure 5A). As a control, we used another group of db/db mice injected with adenoviruses expressing unspecific shRNA (Ad-ctrl). As expected, both groups featured similar body weight before and after adenovirus treatment (Figure 5B). The ratio of liver weight to body weight and blood glucose level under short-term fasting were not different between Ad-si23 and Ad-ctrl mice, while under long-term fasting, the blood glucose levels in Ad-si23 mice were slightly decreased compared to Ad-ctrl mice (Figure 5C and 5D). Strikingly, fasting plasma Chol levels were lower in Ad-si23 mice than in Ad-ctrl mice (Figure 5E). We also measured the glucose tolerance of these two groups of db/db mice. Noteworthily, we found that glucose tolerance was significantly improved in Ad-si23 mice with Med23 knockdown when compared with Ad-ctrl mice before or after adenoviruse treatment (Figure 5F and 5G). Consistent with mice on chow diet or HFD diet, Ad-si23 db/db mice showed decreased gluconeogenesis (Figure 5H). Furthermore, we investigated the expression pattern of MED23 in the livers of HFD-induced obese mice and db/db mice and found no significant difference between control and these mice (Supplementary information, Figure S5A and S5B), suggesting that the mechanism of MED23 in regulating glucose and lipid homeostasis in these two models was not simply by differential expression of MED23 itself. Overall, we demonstrated that compromising the function of the liver MED23 can relieve the main disorders associated to T2D, such as glucose intolerance and dyslipidemia.

Figure 5.

Glucose homeostasis after acute Med23 knockdown in diabetic mice. db/db mice were injected with Ad-ctrl or Ad-si23 (adenoviruses expressing shRNA targeting Med23). n = 5 per group. (A) Immunoblot of MED23 in db/db mice infected with the indicated adenoviruses (2 weeks after Ad injection). (B) Body weight of db/db mice before or 3 weeks after Ad injection. (C) Ratio of liver weight to body weight (18 h fasting). (D) Blood glucose level at fasted states. (E) Fasted plasma cholesterol and TG levels. (F) Glucose tolerance test of mice before Ad injection. (G) Glucose tolerance test of mice 2 weeks after Ad injection. (H) Pyruvate tolerance test of mice (3 weeks after Ad injection). For panels B-H, data are mean ± SEM. *P< 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs control by Student's two-tailed t-test. For all the panels, absence of * or numbers indicates that the statistical analysis was non-significant.

Discussion

In the present study, we first generated liver-specific Med23-deleted mice and we identified Mediator MED23 as an important regulator of energy homeostasis. Further analyses reveled that LMKO mice were resistant to diet-induced obesity and attenuated its related pathological consequences. Finally, using both in vitro and in vivo experiments, we identified MED23 as a specific cofactor in FOXO1-regulated gluconeogenesis and Chol synthesis.

Since its discovery, the Mediator complex has been recognized as a central player in eukaryotic gene regulation and it has now become clear that it is involved in a wide range of signaling pathways. In recent years, many studies revealed that different transcription factors target distinct Mediator subunits, leading to gene-specific physiological effects8,9,47, including regulation of lipid metabolism and energy homeostasis48,49,50,51,52,53,54. In the present study, we described a novel mechanism involving the Mediator complex, which, through the subunit MED23, plays a major role in the regulation of energy homeostasis by modulating gluconeogenesis and Chol synthesis during fasting state. Consequently, LMKO mice featured lower fasting blood glucose and Chol levels, compared to control mice.

Hepatic gluconeogenesis is essential for providing energy for glucose-dependent tissues such as the brain and red blood cells during fasting; however, it is abnormally elevated in T2D55,56. In the present study, gluconeogenic capacity as measured by PTT was reduced in LMKO mice. Accordingly, RNA sequence profiling revealed that, in the LMKO livers, the set of genes related to sterol and carboxylic acid metabolism featured a significantly diminished expression. Specifically, in the fasting state, the expression levels of the genes Pck1 and G6pc, which encode the rate-limiting enzymes for gluconeogenesis, as well as Dhcr7, which regulates Chol synthesis, were lower in Med23-deficient livers compared to controls. In addition, in isolated primary hepatocytes, the forskolin-stimulated expression of Pck1 and G6pc was largely attenuated and the glucose output ability was decreased in Med23-deleted hepatocytes. These observations reveal that MED23 is a critical regulator of gluconeogenesis.

To understand how MED23 regulates gluconeogenesis and gluconeogenic gene expression, we investigated the transcription regulators that function through MED23. Multiple lines of evidence implicate the FOXO1 transcription factor in this process: (i) Genome-wide FOXO1 target genes, identified by ChIP-Seq in mouse livers31, were markedly enriched in the set of genes downregulated in livers from LMKO mice in the fasting state compared to controls. (ii) Hepatic Med23 deficiency attenuates the FOXO1-driven transcription of gluconeogenic genes when FOXO1 is active but fails to modulate FOXO1 target gene expression when FOXO1 is inactivated. (iii) The expression of Gck, which is repressed by FOXO1, was increased in LMKO mice in a fasting state, suggesting that transcriptional repression by FOXO1 is also MED23-dependent. Again, feeding eliminated the differences in Gck expression between LMKO and control mice. (iv) Further analysis showed that the activities of reporters driven by FOXO1 measured by GAL4-FOXO1 system were decreased significantly in Med23−/− cells compared to controls. (v) In Drosophila, the effect of dFOXO in larval fat body and in adult wing could be partially rescued by Med23 knockdown, suggesting the evolutionarily conserved functional interaction between FOXO and MED23. (vi) Med23 deficiency resulted in decreased binding of Mediator and RNAPII at the promoter of the FOXO1 target genes in the LMKO liver cells, most likely due to the disrupted association between FOXO1 and Mediator without MED23. (vii) FOXO1 was observed to be co-immunoprecipitated with MED23 in 293T cells and in a hepatic cell line. Overall, our data support that MED23 functions as a cofactor with FOXO1 by modulating the expression of its target genes. In addition, the interplay between FOXO1 and MED23 is further suggested by the observation that the LMKO mice phenocopy liver-specific Foxo1-knockout mice, with both displaying mild hypoglycemia and enhanced glucose tolerance due to decreased gluconeogenesis30.

It is worthy to note that MED23 may regulate glucose metabolism via alternative pathways. For example, CREB, which regulates gluconeogenesis by interacting with RNAPII via the coactivator CBP43,57, was reported to share with FOXO1 several target genes involved in glucose metabolism58,59,60. However, in the present study, CREB did not co-immunoprecipitate with MED23, suggesting that MED23 and CREB might not be directly associated. Moreover, nuclear receptors might be also involved in glucose and lipid metabolism via MED23, as nuclear receptors including HNF4, PPARs, LXRs, RXR, FXR, PXR, and CAR61, have been reported to actively participate in energy homeostasis in the liver. Thus, it would be interesting to test the possible interplay between MED23 and any nuclear receptors under metabolic regulation. Finally, the modest attenuation in gene expression in KO livers and cells suggests a partial metabolic regulatory role for Mediator MED23. FOXO1 may cooperate with other cofactors, such as PGC-1α59 and TORC260, to overcome the loss of MED23. In addition, FOXO1 itself may bind to additional Mediator component(s). These alternative mechanisms are consistent with the mild phenotype of LMKO mice. The mechanism by which multiple cofactors coordinate the sophisticated gene network to respond to the dynamic metabolic signals remains a challenge for future research.

Importantly, the livers of LMKO mice exhibit overall normal development and function. Despite reduced glucose and lipid production, LMKO mice were able to maintain glucose and lipid levels in a normal range when fed a chow diet, which is consistent with prior observations from mouse model with hepatic ablation of FOXO130. Another interesting finding of the present study was that depletion of Med23 effectively protected mice against diet-induced obesity, and acute deletion of Med23 significantly relieved the disorders associated to obesity and T2D, highlighting the pathophysiological implications of this work.

Overall, this study revealed the important role that Mediator subunit MED23 plays in energy homeostasis, thus providing new insight into the molecular mechanism of insulin resistance and T2D. Pathophysiological importance of this study is also evidenced by the fact that the current high number of T2D patients is expected to nearly double by 2030, highlighting the need of further knowledge for therapeutic strategies.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatment

Med23-floxed (Med23flox) mice were generated through homologous recombination24. Briefly, exons 5-7 of Med23 were floxed by two LoxP sites. After targeting vector delivery, ES cells were screened by PCR. The Med23-floxed mice were backcrossed with C57/BL6J mice for more than two generations. To inactivate Med23 in the liver, we crossed Med23flox/flox mice with Albumin-Cre transgenic mice on C57BL/6J genetic background. The littermates were screened by genotyping, and mice with two copies of LoxP sites and Cre were characterized as LMKO mice (Albumin-Cre/Med23flox/flox). These mice were genotyped by PCR (primer sequences for Med23-F: 5′-GCGGCCGCTATATGCACTGTTAGTGATT-3′, Med23-R: 5′-GTCGACCTTAGAAGAAAGCTCAAACAT-3′ Albumin-F: 5′-gCggTCTggCAgTAAAAACTATC-3′ Albumin-R: 5′-gTgAAACAgCATTgCTgTCACTT-3′ F: forward primer, R: reverse primer). Male mice were employed in all the experiments.

All other mice were from Shanghai Laboratory Animal Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences. For chow diet, 8-12-week old mice were used for experiments. For HFD (60% fat calories; D12492, Research Diet), mice were fed from the age of 4 weeks to the time indicated. Adenovirus infection was performed by tail vein injection with 7 × 108 infectious unit (IFU) per HFD-fed 6-week mouse or with 5 × 109 IFU per 8-week old db/db mouse. Total body fat content of mice was measured by NMR using the Minispec Mq7.5 (Bruker, Germany). Randomization to determine the diet and the feeding status of the mice was carried out using the different dates of birth of each batch of mice. In order to avoid bias in the results, investigators were blinded during sample collection and processing. All animals were maintained and all animal experiments were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences.

Reagents, antibodies, cell lines and plasmids

Insulin, forskolin, glucagon were from Sigma-Aldrich. Anti-Flag beads and Dynal beads were from Sigma-Aldrich. Proteinase inhibitors and Collagenase D were from Roche. Antibodies for co-IP were as follows: MED23 (Novus, NB200-338) and IgG from different species (Santa Cruz). Antibodies for immunoblot were as follows: MED23 (BD Pharmingen, #550429), pGSK3α/β (Cell Signaling, #8566), GSK3α/β (Santa Cruz, sc-7291), MED6 (Santa Cruz, sc-9434), MED16 (Benthyl, A303-668A), MED24 (Benthyl, A301-472A), MED18 (Benthyl, A300-777A), pAKT Ser473 (Cell Signaling, #9271), pAKT Thr308 (Cell Signaling, #9275), AKT (Cell Signaling, #9272), pFOXO1 Ser256 (Cell Signaling, #9461), FOXO1 (Cell Signaling, #2880), pCREB Ser133 (Cell Signaling, #9198), CREB (Cell Signaling, #9197) and γ-tubulin (Sigma-Aldrich, T6557). Antibodies for ChIP were as follows: CDK8 (Santa Cruz, sc-1521), RNAPII (Santa Cruz, sc-899), MED1 (Bethyl, #A300-793A). Immortalized MEF cells and 293T cells were described previously23, and AML12 cell line was given by Dr Jianguo Song62 (Shanghai Institutes for Biological Sciences, CAS, China). Cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination with MyoAlert® Mycoplasma Detection kit (Lonza, #LT07-318) and cells without mycoplasma contamination were used for experiments. For knockdown of Med23 and Med16 in AML12 hepatocytes, retrovirus-mediated shRNA expression was used as described23. The sequences of the oligonucleotides cloned into pSIREN-RetroQ were si-Med23, gagataagtaagttacatg; si-Med16, gagttcgtccttgacatga; and si-Ctrl, gtgcgctgctggtgccaac. Mouse Foxo1 plasmid and its mutants were generously given by Dr A Miyajima (The University of Tokyo, Japan) and GAL4-DBD-FOXO1 and its mutants were cloned based on these constructs. Mouse Med23 was amplified from pMSCV-mMed23 as described63 and was cloned into pcDNA3-5×Myc and −3×Flag vector.

Glucose tolerance, insulin tolerance and pyruvate tolerance tests

For GTTs, mice fed on regular diet were injected i.p. with D-glucose (2 g/kg body weight) after overnight fast, while mice fed on HFD or db/db mice were injected with D-glucose (1 g/kg body weight) after overnight fast. For ITTs, insulin was injected i.p. to mice (0.75 U/kg) fasted 6 h. For PTTs, mice were injected i.p. with pyruvate (2 g/kg) after 18-h fasting. Blood was collected from tail tip at the indicated time points and the glucose was determined using a glucometer (ACCU-CHEK, Roche)64.

Primary hepatocyte culture

Primary hepatocytes were isolated from 8-12-week old mice by collagenase perfusion as described previously65. Cells were plated on 12-well or 24-well tissue culture dishes (Cellbind, Corning) and cultured in M199 medium with 10% FBS for 4-6 h before transfection or infection. Before insulin (100 nM) or glucagon (100 nM) stimulation, cells were fasted in serum-free M199 medium for 14 h.

Plasmid transfection

Targefect-Hepatocyte (Targeting systems) was used for the transient transfection assay of FOXO1 or CREB reporter (Qiagen) activity. Transfection was done according to the kit instruction. Cells were cultured in serum-free M199 medium for 14 h after 42 h transfection, and then forskolin (10 μM) or insulin (100 nM) was added at the indicated time66. For Figure 3I, we used 100 ng FOXO1 reporter (Qiagen), 200 ng FOXO1 expression vector and 50 ng or 100 ng MED23 expression vector as indicated per well (24-well plate). Luciferase expression was quantified using dual-luciferase system (Promega) as described before23.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Co-immunoprcipitation in cells was described previously22. Simply, cells or tissues were lysed in buffer A (1% NP-40, 10% glycerol, 135 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris, pH 8.0, supplemented with protein inhibitors). Lysates were added with 20 μl anti-Flag beads or 4 μg indicated antibody or control IgG and incubated overnight. For antibodies, Protein-A beads (Millipore) were added 2 h before washing with buffer A for four times.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation

Mouse livers (0.2 g) for ChIP assays were freshly isolated and washed with pre-cooled phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The tissue was homogenized with homogenizer (IKA) with a final concentration of 1% formaldehyde in DMEM and the homogenate was rotated on a shaker for 15 min at room temperature followed by the addition of glycine to a final concentration of 0.125 M. The following procedures were performed as described previously67. DNA pulled down by ChIP was analyzed by Q-PCR with SYBR Premix Ex TaqTM(TAKARA). See Supplementary information, Table S4 for the primer sequences used for ChIP DNA analysis.

Fly strains

The following strains were used for ubiquitous or tissue-specific gene expression or knockdown: actin-Gal4, ppl-Gal4, dpp-Gal4, hs-flp;act>CD2>Gal4 uas-GFP, uas-dFOXO. The MED23 RNAi line (34658) was from the Bloomington Stock Center. As a negative control, w1118 wild-type or GFP flies were crossed with the Gal4 driver lines. An additional uas-GFP was present in some crosses to keep the total number of UAS constructs equal.

Clonal analysis

The dFOXO-overexpression and/or MED23-knockdown fly lines were crossed with the hs-flp;act>CD2>Gal4 uas-GFP line without heat shock. Fat bodies from stop-wandering larvae were dissected in PBS and fixed for 30 min in 4% formaldehyde/PBS. After fixation, the samples were washed with 0.2% Triton/PBS, incubated with Phalloidin-Alexa Fluor 555 (1:500, Molecular Probes) in PBS-T for 20 min and washed three times in PBS-T before mounting and imaging. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (1:10 000, Invitrogen). Quantification was performed with the ImageJ software.

Nile Red staining

The dFOXO-overexpression and/or MED23-knockdown fly lines were crossed with the ppl-Gal4 line and fat bodies from stop-wandering larvae were used for Nile Red staining. A 10% stock solution of Nile Red (Sigma-Aldrich) in dimethyl sulfoxide was diluted 1:10 000 in a mixture of 1 × PBS, 30% glycerol, and DAPI. Four to six stop-wandering larvae were dissected, and LDs were mounted and visualized with an Olympus FV-10-ASW confocal microscope. Three to seven images were taken for each genotype, and quantification was performed using the ImageJ software.

Biochemical parameters of blood and liver

Blood and tissues were collected from mice under anesthesia with isoflurane. Blood collected was allowed to clot for 2 h at room temperature, then centrifuged to collect serum. Serum Chol, TG, and NEFA were enzymatically measured with commercial kits (Wako). AST, ALT, and albumin were measured with commercial kits (Shensuoyoufu, Shanghai, China). Insulin (Mercodia), Leptin (Alpco) and Adiponectin (Alpco) levels were measured according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Histological analysis

Tissues were fixed in 4% PFA and then embedded in paraffin. Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

Adenovirus infection of primary hepatocytes

Adenoviruses encoding nonspecific control siRNA or Cre-recombinase were generously provided by Dr Yong Liu (Institute for Nutritional Sciences, SIBS, CAS). Primary hepatocytes were infected with adenovirus (MOI = 7) for 14 h as previously described65. At 36 - 48 h post-infection, primary hepatocytes were exposed to forskolin (10 μM), insulin (100 nM), and glucagon (100 nM) for the indicated times. Glucose output was performed as described64.

RNA and protein analysis

Total RNA isolation, reverse transcription, and Q-PCR were performed as described23. Endogenous mRNAs were normalized to 18S rRNA. See Supplementary information, Table S3 for the primer sequences used for Q-PCR analysis. Mouse tissues were quickly excised and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Tissue was homogenized in tissue lysis buffer (1% NP-40, 137 mM NaCl, 1 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 20 mM Tris, pH 7.4, supplemented with protein inhibitors). The protein concentration was measured with commercial BCA kits (Thermo) for co-IP and immunoblot. Immunoblot was performed as previously described22.

Liver lipids extraction

Liver lipids were extracted by chloroform-methanol method following the protocol described65.

RNA-Seq and GO analysis

Livers were collected from control and LMKO mice fasted 24 h (fast) or fasted 24 h then re-fed 24 h (re-fed) (n= 2 for each group). RNA was extracted by TRIZOL (Invitrogen), and cDNA library was constructed using TruSeq RNA-Seq Sample Prep Kits (Illumina) and was subjected to 76 bases of sequencing on Genome analyzer IIx (Illumina) according to Illumina's standard protocols. Raw reads were mapped to mouse reference genome (NCBI Build 37, mm9) by tophat68 with default parameters. Uniquely mapped reads were filtered and delivered to Cufflinks69 for assembling transcripts. Cuffdiff69 was applied to compare gene expression of LMKO to that of control under fasting and re-fed state. GO for the identified genes was performed by DAVID70 and the top 10 GO categories were selected according to P-value. RNA-Seq data reported in this study has been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/, accession no. GSE48966).

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as the mean ± SEM. unless otherwise indicated. Distribution was tested using the modified Shapiro-Wilks method. When parameters followed Gaussian distribution, Student's t-test was used to compare the different groups, while the Mann-Whitney test (U-test) was employed for data that did not follow the normal distribution. Differences were considered significant at P < 0.05 in the bilateral situation. The absence of * in the graphs indicates that there is no statistic difference between groups. The sample size was estimated based on previously reported studies. Analyses were carried out using the SPSS (Chicago, IL, USA) statistical software package SPSS version 16.0®.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Dang-Sheng Li, Yi Liu, Gen-Sheng Feng, and Arnie Berk for critical reading of the manuscript, Drs Li-Jian Hui, Bao-Liang Song, Yong Liu, Yi-Guo Wang, and Zhong-Zhou Yang for discussions, Jing-Wen Yin for knockout design, MARC of Nanjing University for help with generating the Med23flox mice, Xing Fu for technical help and analysis with RNA-Seq. This study was supported in part by grants from the Chinese Academy of Sciences (XDA01010401), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (2009CB941100 and 2011CB510104), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81030047 to G W, and 31322039 to H S).

Footnotes

(Supplementary information is linked to the online version of the paper on the Cell Research website.)

Supplementary Material

Characterization of LMKO mice and the Mediator complex with Med23 deletion.

Effect of Mediator MED23 deletion on signaling and expression of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism.

Mediator MED23 functions as a cofactor of FOXO in Drosophila and in mice livers.

Effect of acute deletion of Med23 in glucose and cholesterol homeostasis in diet-induced obesity mice.

Analysis of MED23 levels in disease mice model.

General characteristics from control and LMKO mice after 8 weeks under regular chow

General characteristics from control and LMKO mice after 8 weeks under HFD

Primer sequences used in the quantitative PCR analysis

Primer sequences for ChIP

References

- Guariguata L. By the numbers: new estimates from the IDF Diabetes Atlas Update for 2012. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98:524–525. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alberti KG, Zimmet P. Epidemiology: Global burden of disease-where does diabetes mellitus fit in. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2013;9:258–260. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2013.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muoio DM, Newgard CB. Mechanisms of disease: molecular and metabolic mechanisms of insulin resistance and beta-cell failure in type 2 diabetes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:193–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm2327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lusis AJ, Attie AD, Reue K. Metabolic syndrome: from epidemiology to systems biology. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:819–830. doi: 10.1038/nrg2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel AR, Kahn CR. Insulin signalling and the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Nature. 2001;414:799–806. doi: 10.1038/414799a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, Feng D, Wang Q, et al. Regulation of lipogenesis by cyclin-dependent kinase 8-mediated control of SREBP-1. J Clin Invest. 2012;122:2417–2427. doi: 10.1172/JCI61462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Monks B, Ge Q, Birnbaum MJ. Akt/PKB regulates hepatic metabolism by directly inhibiting PGC-1alpha transcription coactivator. Nature. 2007;447:1012–1016. doi: 10.1038/nature05861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik S, Roeder RG. The metazoan Mediator co-activator complex as an integrative hub for transcriptional regulation. Nat Rev Genet. 2010;11:761–772. doi: 10.1038/nrg2901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taatjes DJ. The human Mediator complex: a versatile, genome-wide regulator of transcription. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:315–322. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway RC, Conaway JW. Function and regulation of the Mediator complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2011;21:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knuesel MT, Taatjes DJ. Mediator and post-recruitment regulation of RNA polymerase II. Transcription. 2011;2:28–31. doi: 10.4161/trns.2.1.13950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer KD, Lin SC, Bernecky C, Gao Y, Taatjes DJ. p53 activates transcription by directing structural shifts in Mediator. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:753–760. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes NP, Bjerke G, Llorente B, et al. Gene-specific requirement for P-TEFb activity and RNA polymerase II phosphorylation within the p53 transcriptional program. Genes Dev. 2006;20:601–612. doi: 10.1101/gad.1398206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yao X, Huang Y, et al. Mediator MED23 regulates basal transcription in vivo via an interaction with P-TEFb. Transcription. 2013;4:39–51. doi: 10.4161/trns.22874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukundan B, Ansari A. Novel role for mediator complex subunit Srb5/Med18 in termination of transcription. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:37053–37057. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C111.295915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsten JO, Zhu X, Gustafsson CM. The multitalented Mediator complex. Trends Biochem Sci. 2013;38:531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2013.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Parmely TJ, Sato S, et al. Human mediator subunit MED26 functions as a docking site for transcription elongation factors. Cell. 2011;146:92–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conaway RC, Conaway JW. The Mediator complex and transcription elongation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1829:69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2012.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galbraith MD, Allen MA, Bensard CL, et al. HIF1A employs CDK8-mediator to stimulate RNAPII elongation in response to hypoxia. Cell. 2013;153:1327–1339. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kagey MH, Newman JJ, Bilodeau S, et al. Mediator and cohesin connect gene expression and chromatin architecture. Nature. 2010;467:430–435. doi: 10.1038/nature09380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding N, Zhou H, Esteve PO, et al. Mediator links epigenetic silencing of neuronal gene expression with x-linked mental retardation. Mol Cell. 2008;31:347–359. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Li W, Yao X, et al. Mediator complex regulates alternative mRNA processing via the MED23 subunit. Mol Cell. 2012;45:459–469. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Huang L, Huang Y, et al. Mediator MED23 links insulin signaling to the adipogenesis transcription cascade. Dev Cell. 2009;16:764–771. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin JW, Liang Y, Park JY, et al. Mediator MED23 plays opposing roles in directing smooth muscle cell and adipocyte differentiation. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2192–2205. doi: 10.1101/gad.192666.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens JL, Cantin GT, Wang G, Shevchenko A, Berk AJ. Transcription control by E1A and MAP kinase pathway via Sur2 mediator subunit. Science. 2002;296:755–758. doi: 10.1126/science.1068943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito M, Okano HJ, Darnell RB, Roeder RG. The TRAP100 component of the TRAP/Mediator complex is essential in broad transcriptional events and development. EMBO J. 2002;21:3464–3475. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z, White MF. Targeting forkhead box O1 from the concept to metabolic diseases: lessons from mouse models. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:649–661. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rena G, Guo S, Cichy SC, Unterman TG, Cohen P. Phosphorylation of the transcription factor forkhead family member FKHR by protein kinase B. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17179–17183. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae J, Park BC, Accili D. Insulin stimulates phosphorylation of the forkhead transcription factor FKHR on serine 253 through a Wortmannin-sensitive pathway. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:15982–15985. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.15982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Pocai A, Rossetti L, Depinho RA, Accili D. Impaired regulation of hepatic glucose production in mice lacking the forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 in liver. Cell Metab. 2007;6:208–216. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin DJ, Joshi P, Hong SH, et al. Genome-wide analysis of FoxO1 binding in hepatic chromatin: potential involvement of FoxO1 in linking retinoid signaling to hepatic gluconeogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:11499–11509. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Ou J, Bashmakov Y, et al. Insulin inhibits transcription of IRS-2 gene in rat liver through an insulin response element (IRE) that resembles IREs of other insulin-repressed genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:3756–3761. doi: 10.1073/pnas.071054598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo S, Rena G, Cichy S, et al. Phosphorylation of serine 256 by protein kinase B disrupts transactivation by FKHR and mediates effects of insulin on insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 promoter activity through a conserved insulin response sequence. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17184–17192. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.24.17184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall RK, Yamasaki T, Kucera T, et al. Regulation of phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase and insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 gene expression by insulin. The role of winged helix/forkhead proteins. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:30169–30175. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004898200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi CM, Ueki K, Kahn R. Complementary roles of IRS-1 and IRS-2 in the hepatic regulation of metabolism. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:718–727. doi: 10.1172/JCI23187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Dong X, Park S, Lin X, et al. Irs1 and Irs2 signaling is essential for hepatic glucose homeostasis and systemic growth. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:101–114. doi: 10.1172/JCI25735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakae J, Kitamura T, Silver DL, Accili D. The forkhead transcription factor Foxo1 (Fkhr) confers insulin sensitivity onto glucose-6-phosphatase expression. J Clin Invest. 2001;108:1359–1367. doi: 10.1172/JCI12876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota K, Sakamaki J, Ishida J, et al. A combination of HNF-4 and Foxo1 is required for reciprocal transcriptional regulation of glucokinase and glucose-6-phosphatase genes in response to fasting and feeding. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:32432–32441. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806179200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter FD. Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome: pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. Eur J Hum Genet. 2008;16:535–541. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkhardt R, Toh SA, Lagor WR, et al. Trib1 is a lipid- and myocardial infarction-associated gene that regulates hepatic lipogenesis and VLDL production in mice. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:4410–4414. doi: 10.1172/JCI44213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova MM, Vasquez DS, Ravnskjaer K, et al. Class IIa histone deacetylases are hormone-activated regulators of FOXO and mammalian glucose homeostasis. Cell. 2011;145:607–621. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.03.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekine K, Chen YR, Kojima N, et al. Foxo1 links insulin signaling to C/EBPalpha and regulates gluconeogenesis during liver development. EMBO J. 2007;26:3607–3615. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montminy M, Koo SH, Zhang X. The CREB family: key regulators of hepatic metabolism. Ann Endocrinol (Paris) 2004;65:73–75. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4266(04)95634-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzell MS, Ahren B. The high-fat diet-fed mouse: a model for studying mechanisms and treatment of impaired glucose tolerance and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2004;53(Suppl 3):S215–219. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.suppl_3.s215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman DL, Hummel KP. Studies with the mutation, diabetes, in the mouse. Diabetologia. 1967;3:238–248. doi: 10.1007/BF01222201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghilardi N, Ziegler S, Wiestner A, et al. Defective STAT signaling by the leptin receptor in diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:6231–6235. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.13.6231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grueter CE, van Rooij E, Johnson BA, et al. A cardiac microRNA governs systemic energy homeostasis by regulation of MED13. Cell. 2012;149:671–683. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Xiaoli, Zhao X, Yang F. The Mediator complex and lipid metabolism. J Biochem Pharmacol Res. 2013;1:51–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai L, Jia Y, Viswakarma N, et al. Transcription coactivator mediator subunit MED1 is required for the development of fatty liver in the mouse. Hepatology. 2011;53:1164–1174. doi: 10.1002/hep.24155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana R, Surapureddi S, Kam W, Ferguson S, Goldstein JA. Med25 is required for RNA polymerase II recruitment to specific promoters, thus regulating xenobiotic and lipid metabolism in human liver. Mol Cell Biol. 2011;31:466–481. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00847-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Vought BW, Satterlee JS, et al. An ARC/Mediator subunit required for SREBP control of cholesterol and lipid homeostasis. Nature. 2006;442:700–704. doi: 10.1038/nature04942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taubert S, Van Gilst MR, Hansen M, Yamamoto KR. A Mediator subunit, MDT-15, integrates regulation of fatty acid metabolism by NHR-49-dependent and -independent pathways in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 2006;20:1137–1149. doi: 10.1101/gad.1395406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grontved L, Madsen MS, Boergesen M, Roeder RG, Mandrup S. MED14 tethers mediator to the N-terminal domain of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma and is required for full transcriptional activity and adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:2155–2169. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01238-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabata M, Rodgers JT, Hall JA, et al. Cdc2-like kinase 2 suppresses hepatic fatty acid oxidation and ketogenesis through disruption of the PGC-1alpha and MED1 complex. Diabetes. 2014;63:1519–1532. doi: 10.2337/db13-1304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Inoue H, Ravnskjaer K, et al. Targeted disruption of the CREB coactivator Crtc2 increases insulin sensitivity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:3087–3092. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914897107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saltiel AR. New perspectives into the molecular pathogenesis and treatment of type 2 diabetes. Cell. 2001;104:517–529. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00239-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakajima T, Uchida C, Anderson SF, Parvin JD, Montminy M. Analysis of a cAMP-responsive activator reveals a two-component mechanism for transcriptional induction via signal-dependent factors. Genes Dev. 1997;11:738–747. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.6.738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhala US, Canettieri G, Screaton RA, et al. cAMP promotes pancreatic beta-cell survival via CREB-mediated induction of IRS2. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1575–1580. doi: 10.1101/gad.1097103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver P, Rhee J, Donovan J, et al. Insulin-regulated hepatic gluconeogenesis through FOXO1-PGC-1alpha interaction. Nature. 2003;423:550–555. doi: 10.1038/nature01667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Dentin R, Chen D, et al. A fasting inducible switch modulates gluconeogenesis via activator/coactivator exchange. Nature. 2008;456:269–273. doi: 10.1038/nature07349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans RM, Mangelsdorf DJ. Nuclear receptors, RXR, and the big bang. Cell. 2014;157:255–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K, Wang D, Song J. Cortactin is involved in transforming growth factor-beta1-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in AML-12 cells. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin (Shanghai) 2009;41:839–845. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmp070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X, Zhao M, Xia M, et al. Selective requirement for Mediator MED23 in Ras-active lung cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E2813–E2822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1204311109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luan B, Zhao J, Wu H, et al. Deficiency of a beta-arrestin-2 signal complex contributes to insulin resistance. Nature. 2009;457:1146–1149. doi: 10.1038/nature07617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Jiang L, Wang J, et al. Abrogation of hepatic ATP-citrate lyase protects against fatty liver and ameliorates hyperglycemia in leptin receptor-deficient mice. Hepatology. 2009;49:1166–1175. doi: 10.1002/hep.22774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Vera L, Fischer WH, Montminy M. The CREB coactivator CRTC2 links hepatic ER stress and fasting gluconeogenesis. Nature. 2009;460:534–537. doi: 10.1038/nature08111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Balamotis MA, Stevens JL, et al. Mediator requirement for both recruitment and postrecruitment steps in transcription initiation. Mol Cell. 2005;17:683–694. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Pachter L, Salzberg SL. TopHat: discovering splice junctions with RNA-Seq. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1105–1111. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–515. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang da W, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Characterization of LMKO mice and the Mediator complex with Med23 deletion.

Effect of Mediator MED23 deletion on signaling and expression of genes involved in glucose and lipid metabolism.

Mediator MED23 functions as a cofactor of FOXO in Drosophila and in mice livers.

Effect of acute deletion of Med23 in glucose and cholesterol homeostasis in diet-induced obesity mice.

Analysis of MED23 levels in disease mice model.

General characteristics from control and LMKO mice after 8 weeks under regular chow

General characteristics from control and LMKO mice after 8 weeks under HFD

Primer sequences used in the quantitative PCR analysis

Primer sequences for ChIP