SUMMARY

The asexual forms of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum are adapted for chronic persistence in human red blood cells, continuously evading host immunity using epigenetically regulated antigenic variation of virulence-associated genes. Parasite survival on a population level also requires differentiation into sexual forms, an obligatory step for further human transmission. We reveal that the essential nuclear gene, P. falciparum histone deacetylase 2 (PfHda2), is a global silencer of virulence gene expression and controls the frequency of switching from the asexual cycle to sexual development. PfHda2 depletion leads to dysregulated expression of both virulence-associated var genes and PfApiAP2, a transcription factor controlling sexual conversion, and is accompanied by increases in gametocytogenesis. Mathematical modeling further indicates that PfHda2 has likely evolved to optimize the parasite's infectious period by achieving low frequencies of virulence gene expression switching and sexual conversion. This common regulation of cellular transcriptional programs mechanistically links parasite transmissibility and virulence.

INTRODUCTION

Eukaryotic pathogens often encounter a trade-off between the establishment of infection within a host and transmission to subsequent hosts. In diverse pathogens persistence relies on clonal phenotypic variation associated with epigenetically regulated low frequency stochastic switches (Verstrepen and Fink, 2009). Persistence of Plasmodium falciparum, the most clinically significant cause of human malaria, within the human bloodstream is largely due to phenotypic switching between polymorphic members of the ~60 member var gene family that encodes for the PfEMP1 (P. falciparum Erythrocyte Membrane Protein 1) cytoadherence protein. This process of antigenic variation allows for sequestration of infected red blood cells in the microvasculature, thereby preventing clearance by the spleen (Baruch et al., 1995; Smith et al., 1995; Su et al., 1995).

Switches in expression of var genes and other virulence-associated, clonally variant multigene families are in part mediated by the presence of distinct histone modifications and variants (Lopez-Rubio et al., 2007; 2009; Petter et al., 2011). Active or silent chromatin states at individual loci within P. falciparum are written and maintained by the concerted actions of histone modifying enzymes such as the class III sirtuin histone deacetylases (HDACs) PfSir2a and PfSir2b (Duraisingh et al., 2005; Freitas-Junior et al., 2005; Tonkin et al., 2009) and the histone methyltransferases PfSET10 and PfSET2 (also known as PfSETvs) (Jiang et al., 2013; Volz et al., 2012). Histone deacetylases promote transcriptional silencing by removing acetyl groups on histones. This facilitates H3K9 methylation (H3K9me3), P. falciparum heterochromatin protein 1 (PfHP1) binding (Flueck et al., 2009; Lopez-Rubio et al., 2009; Pérez-Toledo et al., 2009), heterochromatin formation and reduced accessibility for transcription (Coleman et al., 2012; Duraisingh et al., 2005; Scherf et al., 1998).

In addition to control of adhesive phentoypes and immune evasion in eukaryotic pathogens, epigenetic regulation has been shown to have a role in regulating developmental transitions (Saksouk et al., 2005; Sonda et al., 2010). In each asexual cycle of the P. falciparum blood-stage, a small subpopulation of parasites converts to the sexual gametocyte form required for transmission to the mosquito vector. Recently, genetic determinants for sexual differentiation have been identified in P. falciparum (Eksi et al., 2012; Ikadai et al., 2013; Rovira-Graells et al., 2012; Silvestrini et al., 2010; Young et al., 2005). However, the molecular basis for the frequency of switching from the asexual cycle to sexual development remains obscure. Unlike bacterial and viral pathogens where pathogen load directly correlates with the probability of transmission, P. falciparum relies upon an antigenically distinct, avirulent gametocyte form that makes up only a small fraction of parasites in the blood. Indeed, from an evolutionary perspective it remains unclear why so few transmission stages are produced (Mideo and Day, 2008; Pollitt et al., 2011).

Here, we demonstrate that the class II HDAC protein, P. falciparum histone deacetylase 2 (PfHda2), is essential for asexual proliferation in vitro. Through conditional depletion, we identify a role for PfHda2 both as a global regulator of virulence gene expression and as a regulator of the frequency of P. falciparum gametocyte conversion, with transcriptional activation predominantly at heterochromatin-enriched loci. These data, in combination with mathematical modeling, suggest that PfHda2 is a critical component of shared epigenetic regulatory machinery that has evolved to provide low frequency switch rates for both antigenic variation and transmission gene expression programs that enhance the duration of parasite infectiousness.

RESULTS

P. falciparum Hda2 is an essential nuclear class II histone deacetylase

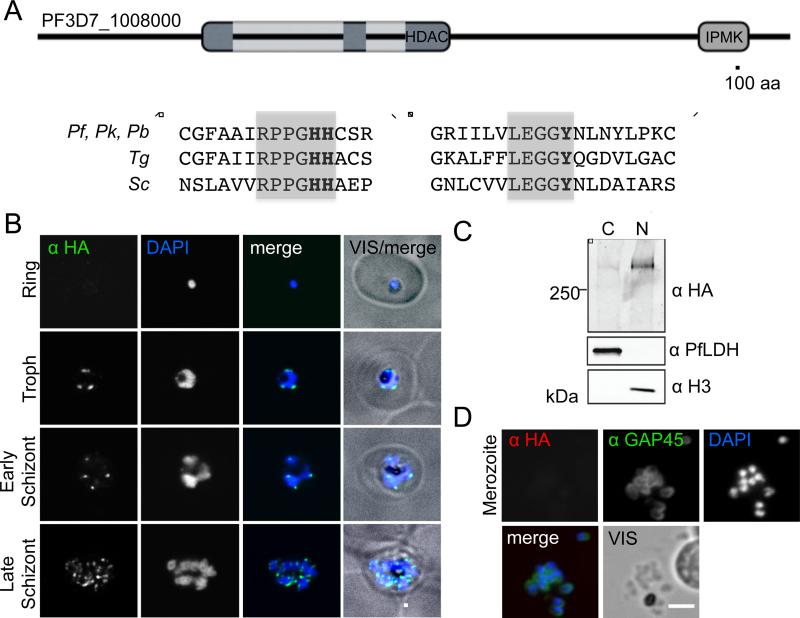

We bioinformatically identified PF3D7_1008000 as one of two >250 kDa putative histone deacetylases (HDAC) within the P. falciparum genome. PF3D7_1008000 contained both of the predictive sequences of a class II enzyme, RPPGHH and LEGGY (catalytic residues in bold) (Figure 1A, Figure S1A) (Grozinger et al., 1999) and was renamed PfHda2. In addition to the HDAC domain, PfHda2 contains an inositol polyphosphate multikinase (IPMK) domain at its C-terminus. IPMKs sequentially generate IP4 and IP5 from the soluble second messenger IP3 (Nalaskowski et al., 2002). This combination of HDAC and IPMK domains is unique to the alveolate phylum including other Plasmodium spp, Toxoplasma, Theileria, Paramecium and Tetrahymena (Figure S1B and Table S1). PF3D7_1472200, the second large HDAC identified, is another class II enzyme that was named PfHda1, although it lacks any homology with PfHda2 outside the HDAC core.

Figure 1. PfHda2 is an essential nuclear histone deacetylase.

A. Schematic of PF3D7_1008000 protein highlighting HDAC and IPMK domains. Light grey: low complexity sequence interrupting the HDAC domain. Box: Class II HDAC motifs with catalytic residues in bold. Pf: Plasmodium falciparum, Pk: Plasmodium knowlesi, Pb: Plasmodium berghei, Tg: Toxoplasma gondii, Sc: Saccharomyces cerevisiae. See also Figure S1. B. Immunofluorescence detection of PfHda2-HA in the perinuclear region of late stage asexual P. falciparum. Scale bar = 3 µm C. Cellular fractionation of PfHda2-HA parasites to separate the nuclear (N) and cytoplasmic (C) compartments. Histone H3-nuclear control, PfLDH-cytoplasmic control D. Immunofluorescence did not detect PfHda2-HA in merozoites co-stained with anti-GAP45.

To characterize the timing of its expression and localization, immunofluorescence assays were performed against endogenously epitope-tagged PfHda2 (Figure S1C). Concentrated foci of PfHda2 localized near the nuclear periphery, a largely heterochromatic subcompartment that has been linked to both the activation and silencing of clonally variant genes (Coleman et al., 2012; Duraisingh et al., 2005; Dzikowski et al., 2007; Freitas-Junior et al., 2005; Ralph et al., 2005; Voss et al., 2006). This localization persisted through S-phase and schizogony with the numbers of PfHda2 foci increasing with the dividing parasite nucleus (Figure 1B, Movies S1 and S2). Cellular fractionation confirmed PfHda2 localization to the nuclear fraction (Figure 1C). PfHda2 protein was not detected in free merozoites suggesting rapid degradation at the end of the asexual cycle (Figure 1D).

Depletion of PfHda2 impairs P. falciparum proliferation in vitro

To determine the cellular function of PfHda2, we attempted to directly disrupt the gene. PfHda2-null parasites were not generated despite multiple attempts using single and double homologous recombination approaches (Figure S2A). The failure of multiple approaches to disrupt the PfHda2 locus strongly suggests the full-length protein is essential in the asexual cycle of P. falciparum.

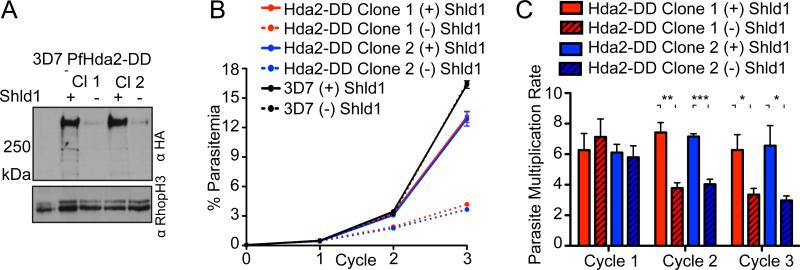

Given the essential nature of PfHda2, we targeted the C-terminus of the endogenous protein with a destabilization domain (DD) for conditional protein expression (Figures S2B and S2C) (Armstrong and Goldberg, 2007). Removing Shield-1 (Shld1) from a synchronous culture of early ring stage PfHda2-DD parasites caused an ~95% depletion in PfHda2 protein levels in schizont stage cultures (Figure 2A). Parasite proliferation was unaffected in the first cycle post-knockdown but decreased two-fold in each successive cycle due to a defect in intracellular growth (Figures 2B, 2C and S2D). When egress and invasion were assayed, knockdown schizonts transitioned to rings with a similar efficiency as wildtype (Figures S2E and S2F). DNA content analysis confirmed knockdown parasites progressed normally until a DNA replication defect emerged in a subpopulation of schizonts during S-phase in the second cycle following knockdown (Figures S2E and S2G). Thus, PfHda2 depletion profoundly impacts the parasite's ability to proliferate.

Figure 2. Conditional expression of PfHda2 reveals a growth defect following protein knockdown.

A. Western blots demonstrate knockdown in two PfHda2-DD clones.

B. Proliferation of wildtype and knockdown parasites monitored by flow cytometry. Data are representative of five similar experiments, mean ± SD of triplicate measurements within one experiment.

C. Parasite multiplication rate (PMR) was determined for PfHda2-DD parasites over three cycles. Data are averages of five independent experiments. (Mean ± SEM, unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test, * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, ***p<0.005). See also Figure S2.

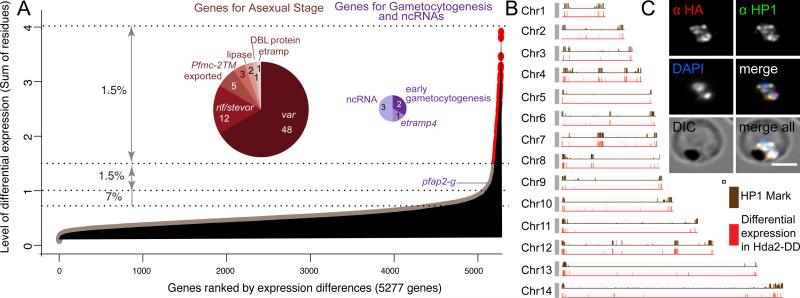

PfHda2 regulates expression of heterochromatic genes

To determine the impact of PfHda2 knockdown on P. falciparum gene expression, DNA microarrays were used to examine global transcripts at six hour intervals from the schizont stage of the first asexual cycle to the end of the second cycle. While the majority of genes were unaffected by PfHda2 knockdown, approximately 3% of the genome showed a differential expression greater than two-fold (top 1.5% with Z-score > 3.4; top 1.5-3% with Z-score > 1.6) (Figure 3A). An additional 7% of genes showed 1.7-fold differential expression (top 3-8% with Z-score > 1) (Figure 3A and Table S2). An independent non-parametric estimate showed a similar fraction of differentially expressed genes (11%) (Wilcoxon Signed Rank Test, p <0.05). Progression through the transcriptional cascade was nearly identical (r>0.8 Pearson correlation) in wildtype and PfHda2 knockdown parasites until 86 hours post invasion and remained high (r>0.7 Pearson correlation) for the remainder of the cycle. Transcriptional changes observed prior to 86 hours are therefore not consequences of changes in growth. Dysregulation of gene expression was largely limited to two distinct classes of genes; multigene families exhibiting variant expression throughout the asexual cycle and genes associated with gametocytogenesis (Figure 3A and Table S2) (Eksi et al., 2012; Ikadai et al., 2013; Rovira-Graells et al., 2012; Silvestrini et al., 2010; Young et al., 2005).

Figure 3. Knockdown of PfHda2 leads to transcriptional dysregulation of heterochromatin enriched loci.

A. Global changes in transcriptional regulation following PfHda2 knockdown were analyzed by DNA microarray. The level of differential expression is shown as the sum of the absolute log2 (normalized expression) difference of paired timepoints, as an attribute of overall differential expression over the growth cycle. Gene groups in the top 1.5% most highly dysregulated genes are highlighted. See also Table S2.

B. PfHda2-regulated genes demonstrate significant overlap with PfHP1 occupancy (Flueck et al., 2009) (Pearson's r = 0.6). See also Figure S3 and Table S3.

C. Immunofluorescence detected colocalization of PfHda2 with PfHP1 in schizont stage parasites.

Transcriptional silencing of members of multigene families has been shown to correlate with regions of facultative heterochromatin and the H3K9me3-binding heterochromatin protein PfHP1, while H3K9 acetylation (H3K9ac) marks active genes (Flueck et al., 2009; Lopez-Rubio et al., 2009). We find that 69% of genes dysregulated following PfHda2 knockdown are also bound by PfHP1 (Figures 3B, S3A and S3B and Table S3) (Flueck et al., 2009) and co-localization of PfHda2-HA and PfHP1 was observed by imunofluorescence assay (Figure 3C). Additionally, PfHda2-regulated genes were significantly H3K9me3-enriched and largely lacked H3K9ac (Figures S3C and S3D) (Salcedo-Amaya et al., 2009). PfHda2 knockdown affected neither PfHP1 localization nor its total protein abundance at this level of resolution (Figures S3E and S3F), nor did it lead to global changes in histone acetylation (Figure S3G) suggesting a highly targeted role for PfHda2 in the mobilization of PfHP1 bound heterochromatin.

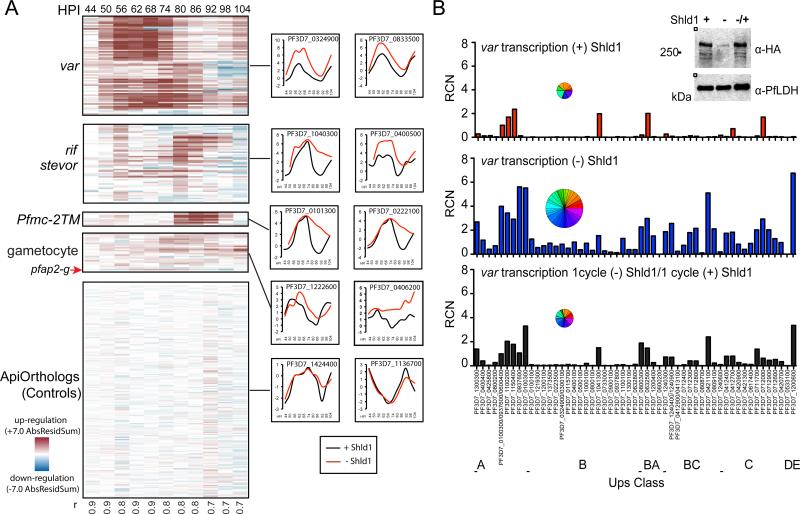

PfHda2 is a global regulator of var gene expression

We identified specific gene families over-represented in the transcriptional change dataset following PfHda2 knockdown (Figure 4A). The most highly changed gene class was the var multigene family (Figure 4A). 86% of the family was represented among the most differentially expressed genes indicating that PfHda2 is a global regulator of var gene silencing. Other multigene families were also dysregulated, including Pfmc-2TM (73%) and rif/stevor (46%) (Figure 4A). Despite the significant increases in var gene expression following knockdown, the temporal profile of var activation and silencing was maintained. In contrast, the transcriptional profiles of Pfmc-2TM and rif/stevor, which peak later in the cell cycle, generally demonstrated a slow decay phenotype where the expression peak was unaffected by PfHda2 knockdown, but was comparatively slow to turn off (Figure S4A).

Figure 4. PfHda2 knockdown leads to global activation of var genes.

A. The gene families with the strongest dysregulation (var, rif, stevor, Pfmc-2TM and genes associated with gametocytogenesis (Eksi et al., 2012; Ikadai et al., 2013; Rovira-Graells et al., 2012; Silvestrini et al., 2010; Young et al., 2005)) are compared to a control set of ortholog genes conserved across the apicomplexan species (ApiOrthologs). Individual gene representatives are shown (log2 R/G). r = Pearson correlation coefficients comparing PfHda2 knockdown and wildtype at each time point.

B. Global var transcription following PfHda2 knockdown (upper and middle panels). Upregulation of var transcription following PfHda2 knockdown is reversible following readdition of Shld1 (bottom panel). Pie charts sized to the total summation of RCN contain slices proportional to expression of each transcript. Data shown are from one representative experiment of three (-Shld1) or two (reversion) biological replicates that yielded similar results. Inset: PfHda2-DD protein expression was restored upon re-addition of Shld1 after one cycle of knockdown. See also Figure S4.

We used the conditional knockdown strain to more closely study the quantitative expression of the entire var gene repertoire (Salanti et al., 2003). We observed a universal loss of transcriptional repression across all classes with an overall ~8-fold increase in total var transcripts (Figure 4B). UpsB, the most sub-telomeric subset, demonstrated the greatest fold change in var expression, likely due to this class having the tightest silencing prior to PfHda2 knockdown. Conversely, upsA, with the greatest expression in the wildtype strain, showed the smallest relative change. As expected, transcriptional activation at specific var loci was associated with increased H3K9Ac and decreased H3K9me3 as determined by ChIP, implying that the observed changes represent bona fide activation of previously silent var promoters (Figure S4B).

To determine whether dysregulation of var expression is reversible within the asexual mitotic cell cycle or requires passage through the insect for meiosis, we used the destabilization domain system to revert the PfHda2 protein knockdown by returning Shld1 to the parasite culture. Rescue of the PfHda2 knockdown resulted in a return of silencing across all var classes, demonstrating the reversibility of PfHda2-mediated epigenetic regulation of this process (Figure 4B). Rescue of the PfHda2 knockdown also reversed the parasites’ growth defect, but only after a one cycle delay, similar to that observed for the initial knockdown growth phenotype (Figure S4C).

Telomere length has previously been associated with changes in var gene expression following the deletion of PfSir2a histone deacetylase (Tonkin et al., 2009). We find no telomere-associated changes after a single cycle of PfHda2 knockdown, implying that var expression is not directly linked to telomere length (Figure S4D). After two months of PfHda2 knockdown, however, changes in telomere length were observed, suggesting PfHda2 may play a role in the long-term maintenance of chromosome structure (Figure S4D).

PfHda2 depletion leads to increased gametocyte conversion

In addition to an impact on multigene families encoding virulence genes, PfHda2 knockdown also dysregulated genes associated with gametocytogenesis (Figure 4A). Nearly 40% of our defined set of sexual-stage gametocyte genes (Eksi et al., 2012; Ikadai et al., 2013; Rovira-Graells et al., 2012; Silvestrini et al., 2010; Young et al., 2005) were associated with HP1-bound heterochromatin and >70% were dysregulated following PfHda2 knockdown (Figure 5A, S5A). Of the heterochromatin-marked gametocyte genes, the most strongly dysregulated gene following PfHda2 knockdown was PF3D7_1222600 (pfap2-g) (Figure S5A), encoding the PfApiAP2 transcription factor shown recently to be required for the transcriptional switch to gametocytogenesis (Kafsack et al., 2014; Sinha et al., 2014). Additionally, the heterochromatinized genes (Pfge2, Pfge7, Pfge8) on chromosome 14 undergo a 1.7 fold or greater differential expression. Other genes are differentially expressed in the PfHda2 knockdown but are not heterochromatin-marked suggesting they may be downstream targets of PfAP2-g. The effect on global var gene dysregulation we find with the PfHda2 knockdown resembles that seen with the methyltransferase PfSET2 knockout (Jiang et al., 2013), however in stark contrast, dysregulation of gametocyte gene expression is unique to PfHda2 knockdown (Figure S5B). Supporting this difference, var loci are enriched with H3K36me3, the histone modification made by PfSET2, while this mark is reduced at the pfap2-g locus (Figure S5C).

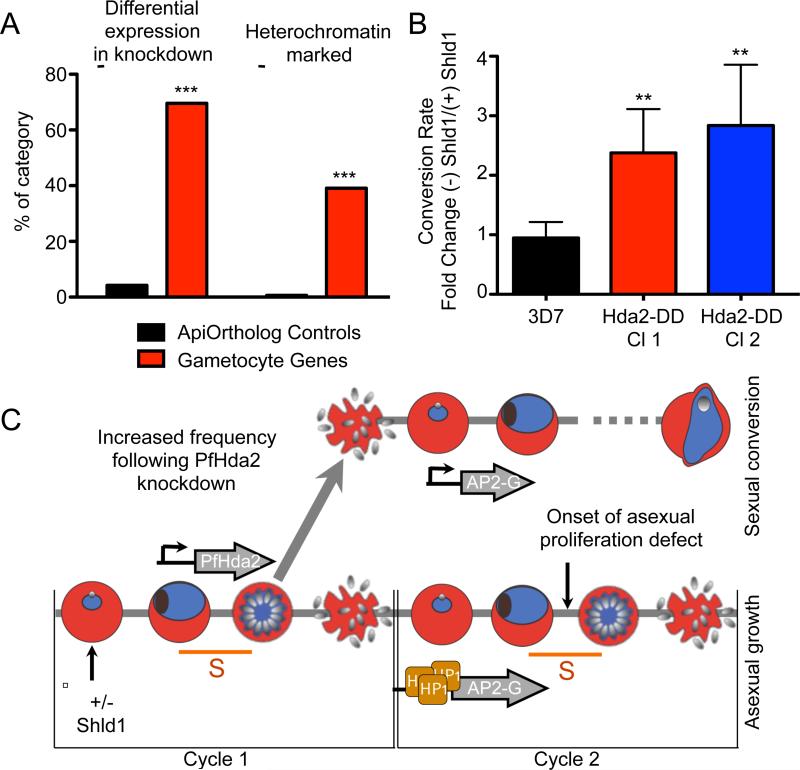

Figure 5. PfHda2 knockdown increases gametocyte conversion.

A. Specific transcripts of genes previously defined as markers of early gametocytes were compared with the apicomplexan ortholog control set to assess changes in the level of differential expression following PfHda2 knockdown and heterochromatin through association with PfHP1 (Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test *** p<0.001).

B. The conversion rate to gametocytes was calculated from two clones of PfHda2-DD parasites and the 3D7 parental line following Shld1 removal. Data are averaged from three biological replicates (Mean ± 95% CI, unpaired, two-tailed Student's t-test, ** p<0.005).

C. Model depicting how PfHda2 function in one cycle alters the frequency of sexual conversion through activation of the pfap2-g locus in the next cycle. See also Figure S5.

To determine whether PfHda2 knockdown leads to an increase in the phenotypic rate of conversion to gametocytes, we measured gametocyte production in PfHda2 wildtype and knockdown parasite cultures. We observed a three-fold increase in the conversion rate in knockdown parasites (Figures 5B, S5D and S5E). This increase in conversion rate was partially reversed upon re-addition of Shld1 to ring stage cultures for two cycles following one cycle of depletion (Figure S5F). In contrast to the var genes, we observed no significant changes in histone modification at the pfap2-g locus following knockdown, consistent with a switch to activation of this locus within only a subset of parasites (Figure S4B). Given the expression of PfHda2 in S-phase and pfap2-g in rings, our data support a role for PfHda2 in passing on an epigenetic signature for the expression of pfap2-g in the next cycle (Figure 5C), explaining the observation that commitment to gametocytogenesis occurs in the previous asexual cycle (Eksi et al., 2012).

Shared epigenetic regulation of antigenic variation and gametocyte conversion optimizes parasite infectious period

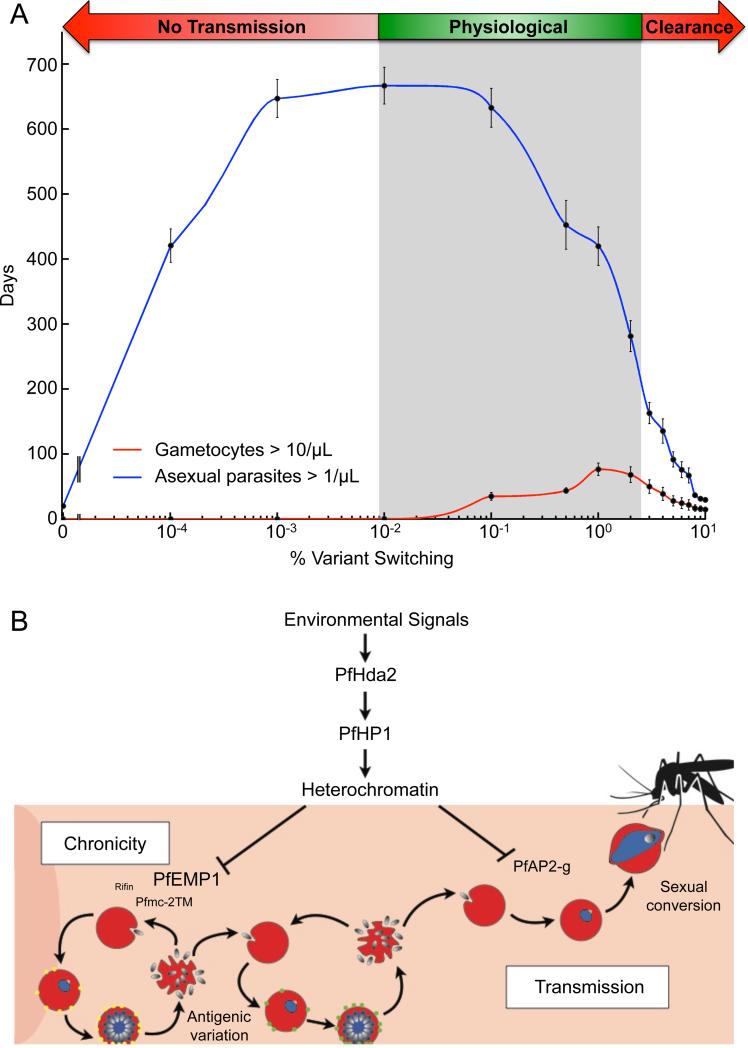

Our findings have two significant implications for the understanding of the evolution of P. falciparum malaria parasites. First, although an evolutionary trade-off between virulence and transmission has been postulated for a wide range of pathogen systems, PfHda2 provides a mechanistic link between the expression of malaria virulence factors and the production of transmission stages in malaria parasites. Second, a variety of hypotheses have been put forward to explain the evolution of ‘reproductive restraint’ associated with the paucity of P. falciparum transmission stages in the blood (Mideo and Day, 2008; Pollitt et al., 2011). Using a mathematical model, which allows us to examine the possible in vivo implications of our findings, we explored the parasite dynamics within the host when shared epigenetic machinery controls rates for both antigenic variation and gametocyte conversion. We find that low, but nonzero, switch rates of var gene expression maximize the length of infection, with the duration of infectiousness to anopheline mosquitoes showing a similar relationship but at marginally higher switch rates (Figure 6A). When var switching rates are too rapid the parasite quickly presents most of its antigenic variants to the immune system, reducing the duration of infection. However, if the var switching rate is close to zero, the parasite will be unable to evade the immune response and be cleared without the production of sufficient gametocytes to ensure transmission (Figure 6A). In contrast, because the expansion of the asexual population during each round of replication is large enough that rapid proliferation can continue even with substantial rates of switching to transmission stages, the infectious period is comparatively insensitive to increases in gametocyte conversion rate. In combination with our experimental results, therefore, our findings suggest that investment in transmission stages is inextricably linked to the control of antigenic variation, and that reproductive restraint may in fact represent a byproduct of adaptation for chronicity via antigenic variation (Figure 6B).

Figure 6. Evolution of shared machinery for transcriptional control of persistence and transmission leads to optimal parasite infectiousness.

A. Mathematical modeling of blood-stage parasite population dynamics within a single infection demonstrates an optimal level of variant switching and gametocyte conversion to obtain the highest number of days of infectiousness (measured by the number of days with greater than 10 gametocytes/μL, red line). Physiological % variant switching (shaded) also is consistent with the longest infections (measured by the number of days with microscopically detectable asexual parasites, blue line). Variant switching rate and gametocyte conversion rate are varied together, as under shared epigenetic control, with the value on the x-axis representing the rate of both. See also Table S4.

B. Proposed model for use of a common silencing regulator, PfHda2, to mobilize heterochromatin and control switch rates for both antigenic variation and gametocyte conversion genes.

DISCUSSION

The variegated expression associated with epigenetic regulation is exquisitely suited for the low frequency switches in gene expression underlying antigenic variation, a process required by many eukaryotic pathogens for persistence in hosts (Domergue et al., 2005; Duraisingh et al., 2005; Freitas-Junior et al., 2005; Prucca et al., 2008; Rudenko et al., 1995). Here, we demonstrate that an epigenetic regulator, the class II histone deacetylase PfHda2, is essential for blood-stage proliferation of P. falciparum. Employing a conditional protein expression strategy, we find a critical role for this regulator in two fundamental parasitic processes that exhibit clonal variation: antigenic switching and gametocyte conversion.

Variant expression of the var family of virulence genes is epigenetically regulated by several non-essential histone modifying proteins including the sirtuin histone deacetylases, PfSir2a and PfSir2b, which appear to impart a ‘division of labour’ by regulating specific var gene subsets (Duraisingh et al., 2005; Tonkin et al., 2009). This differs from PfHda2 which, like the histone methyltransferase PfSET2 (Jiang et al., 2013), is a global regulator of the var gene family. Depletion of PfHda2 also affects the transcription of other non-var genes that exhibit clonal variation, including a dramatic upregulation of members of the MC-2TM family (Lavazec et al., 2007). The majority of genes in this altered set were marked with PfHP1, likely defining a fundamental genetic circuit wherein PfHda2 nucleates heterochromatin formation (Figure 6B). Similarly, in fission yeast the class II HDAC Clr3 is required for the nucleation and maintenance of heterochromatin at centromeres and the mating locus (Yamada et al., 2005).

Strikingly, unlike PfSET2 and the sirtuins, we find that PfHda2 regulates gametocyte gene expression. The ApiAP2 transcription factor PfAP2-g has recently been identified as a critical switch for transcription of gametocyte genes (Kafsack et al., 2014; Sinha et al., 2014), and this gene becomes activated following depletion of PfHda2. Previous work has mapped the time of gametocyte commitment to the schizont-stage in the asexual cell-cycle preceding the formation of gametocytes (Bruce et al., 1990; Eksi et al., 2012). This commitment period is consistent with PfHda2 peak expression in the late trophozoite and schizont stages, which include the DNA synthesis phase of the asexual cycle (Figure 5C). This contrasts with PfHP1, which is expressed constitutively through the asexual cycle (Flueck et al., 2009). Indeed, the PfHda2 ortholog in the evolutionarily-related alveolate parasite Tetrahymena thermophila deacetylates newly synthesized histones (Smith et al., 2008) and fission yeast Clr3 inhibits histone turnover for the maintenance of heterochromatin (Aygün et al., 2013).

While a low switch rate between var genes has almost certainly evolved to promote chronicity, it has long been questioned why P. falciparum gametocyte conversion rates are so low. Theoretically, it is difficult to account for the evolution of this “reproductive restraint” (McKenzie and Bossert, 1998; Mideo and Day, 2008; Taylor and Read, 1997). Studies of human infectiousness suggest that low gametocyte densities can be efficiently transmitted to mosquitoes (Bousema and Drakeley, 2011; Churcher et al., 2013). This implies that there is unlikely to be a strong selective disadvantage to moderate or low conversion rates, and our model indicates that long infections with low sexual conversion rates provide optimal transmission potential (Figure 6A). We propose that the low rates of gametocyte conversion observed in P. falciparum evolved as a consequence of the shared epigenetic machinery with var switching, which drives these distinct phenotypic switches.

With little selective disadvantage to small variations in gametocyte conversion rates, the epigenetic frequencies may have been principally determined by the strong selective pressure for antigenic variation. Unlike the disparate collection of multigene families employed by Plasmodium spp. during asexual development, the core machinery for regulating the production of transmission stages in all Plasmodia, such as ApiAP2-g, appears conserved. If the genetic mechanism controlling gametocyte conversion rates evolved prior to regulators of var switch rates, then reproductive restraint may not be adaptive for sexual conversion per se, but driven by the need to optimize low switch rates for antigenic variation. These low switch rates (~1% per generation) may therefore represent a particular strategy for P. falciparum chronicity in areaswhere mosquito vector availability is seasonal or unreliable. The resulting low levels of gametocyte conversion and transmission may themselves represent exploitation of a biological niche as, at the other extreme, several hemosporidians, including hepatocystis and hemoproteus, bypass blood-stage schizogony and antigenic variation altogether, and immediately form gametocytes after entering the circulation (Martinsen et al., 2008).

It remains to be seen whether PfHda2 activity is modulated in a physiological setting to translate environmental signals into changes in transcriptional programs for antigenic variation and virulence. Importantly, PfHda2 could provide a mechanistic link between var gene dysregulation and sensing of the host environment in severe disease (Merrick et al., 2012; Warimwe et al., 2012). Sexual conversion rates are also thought to be influenced by host signals such as anemia, reticulocyte concentration, cytokines and microvesicles (Baker, 2010; Mantel et al., 2013; Regev-Rudzki et al., 2013) and PfHda2 may play a central role in coordinating the frequency of sexual conversion and antigenic variation in response to these signals.

Despite the fact that antigenic variation and sexual conversion are not required for proliferation in vitro, we find that the class II PfHda2 is an essential gene, validating it as a target for pharmacological inhibition. However, the exact nature of PfHda2 activity remains to be elucidated. PfHda2 conspicuously contains both protein deacetylase and IPMK domains, an alveolate-specific adaptation that suggests they are functionally linked. Both, or either of these domains could be responsible for the mobilization of heterochromatin. PfHda2, therefore, has great potential for selective inhibition and indeed, several HDAC-targeted inhibitors have been identified that are toxic to parasites at low nanomolar concentrations, including FDA-approved HDAC inhibitors (Patel et al., 2009). Future studies will determine which phenotypes result from the function of either of the two domains, or indeed whether PfHda2 is a scaffold for a larger silencing complex as is the case for many class II deacetylase enzymes.

In summary, we have identified PfHda2 as a key regulator of antigenic variation and the frequency of gametocyte conversion. In a related paper, Brancucci et al. find that the conditional depletion of PfHP1 also has profound effects on var gene expression, gametocyte conversion and proliferation. This is consistent with our proposition that PfHda2 is an upstream regulator of PfHP1, required for heterochromatin formation and gene silencing. Interplay of PfHda2 with other levels of regulation are expected to be important. For instance, the translational repressor PfPuf2 has been shown to be required for gametocyte conversion while suppressing proliferation (Miao et al., 2010). It has been suggested that introducing control programs may increase malaria parasite virulence in some circumstances (Mackinnon et al., 2008). Sharing of core epigenetic machinery suggests that the selection against one of these fundamental parasitic processes during drug or vaccine interventions might have an unexpected effect on the other with serious public health implications.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Parasite culture and Transgenic Parasites

The 3D7 strain of P. falciparum was obtained from the Walter and Eliza Hall Institute (Melbourne, Australia). Parasites were cultured as previously described (Trager and Jensen, 1976). Targeting plasmids were constructed and transfected into P. falciparum 3D7 using single crossover recombination (Duraisingh et al., 2002).

Southern and Western Blotting with Nuclear Fractionation

Preparation of genomic DNA and Southern blotting was performed as previously described (Dvorin et al., 2010). Telomere Restriction Fragment Southern blots were performed as previously described (Merrick et al., 2010). Western blot lysates were probed with the following primary antibodies: αHA (1:1000) (clone 3F10, Roche Applied Science), αH3 (1:5000) (Upstate), αPfLDH (1:2000) (gift of Michael T. Makler), αRhopH3 (1:500) (gift of Jean-Claude Doury), αAcetyl-Lysine (1:1000) (#9441, Cell Signaling), αH3Ac (1:2000) (06-599, Millipore), αH3K9Ac (1:2000) (07-442, Millipore), αH3K14Ac (1:1000) (06-911, Millipore), αH3K9Me3 (1:2000) (07-442, Millipore). A previously described P. falciparum nuclear and cytoplasmic fractionation protocol (Voss et al., 2002) was adapted to assay Hda2-HA nuclear localization.

Immunofluorescence Assays

HA-tagged proteins were visualized as previously described (Bushkin et al., 2010). Co-staining of HA-tagged PfHda2 with PfHP1 (1:500) (gift of Till Voss) or PfGAP45 (1:3000) (gift of Julian Rayner) was done as previously described (Flueck et al., 2009) (Extended Experimental Procedures).

PfHda2 Knockdown, Proliferation and Cell Cycle Timecourse Assays

PfHda2-HA-DD parasites were synchronized in at least two consecutive cycles as ring stage parasites with 5% D-sorbitol and washed 3X in incomplete media to remove Shld1. Pellets were then resuspended in complete RPMI-1640 and split into two identical cultures. Shld1 was returned to only one culture. Cultures were harvested as schizonts and western blots were performed as above. To measure proliferation, schizont-stage parasites were purified by MACS column (Milteny) or Percoll gradient (GE Lifesciences). Parasites were allowed to re-invade for 2-4 hours before sorbitol lysis as described above. Proliferation was assayed as previously described (Dvorin et al., 2010). Parasite multiplication rate was calculated as (cycle n parasitemia)/(cycle n-1 parasitemia). For timecourse experiments samples were stained with Sybr Green I every 8 hours and measured by flow cytometry with gating by DNA content or counted by thin smear.

Microarray Analysis

Tightly synchronized PfHda2-DD parasites treated ± Shld1 were grown under shaking conditions. Starting at 44 hours post Shld1 removal, samples were harvested in Trizol for RNA extraction every 6 hours for 66 hours. DNA microarray analysis of global transcription was performed as previously described (Painter et al., 2013) (Extended Experimental Procedures). The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE54806 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE54806).

var Expression Analysis and Chromatin Immunoprecipitation-qPCR of PfHda2 knockdown parasites

Highly synchronous parasites were obtained via MACS/Sorbitol purification as described above. After one full lifecycle, ring stage parasites were harvested for RNA, which was converted to cDNA and analyzed with specific 3D7 var primers as previously described (Merrick et al., 2010; Salanti et al., 2003). Chromatin immunoprecipitation-qPCR was performed as previously described (Coleman et al., 2012) (Extended Experimental Procedures).

Gametocyte Conversion Assays

Tightly synchronized ring stage parasites were treated +/− Shld1 at 2.5% parasitemia. Following reinvasion, parasitemia was determined using Sybr Green staining and flow cytometry. Cultures were then treated with heparin to stop subsequent reinvasion and allow monitoring of gametocyte formation. 96 hours post reinvasion, gametocytes were counted from triplicate wells by thin smear. Conversion rate was calculated as (gametocytes)/(starting parasitemia). For reversion assays, Shld1 was removed from the culture for one cycle and re-added for 2 subsequent cycles. Gametocytes formed from the initial Shld1 depletion were removed by percoll gradient to avoid obscuring the gametocyte counts.

Modeling

A discrete-time stochastic model introduced by Recker et. al. (Recker et al., 2011) of the blood-stage parasite dynamics of a P. falciparum infection was modified to include conversion to gametocytes. Here, asexual parasitemia at each 48-hour time step depends on a) asexual parasites in the previous time step, b) growth due to the release of multiple merozoites per parasite, c) removal by the various components of the immune response, and d) removal of a small fraction in the conversion process to gametocytes. The total parasite population is sub-divided by the antigentically-varying protein expressed, and during each time step the parasites have a small probability of switching the expressed variant. The immune response includes both an innate and an adaptive immune response equivalently applied against all variants and two additional adaptive responses, one variant specific and one cross reactive, that respond to particular subsets of variants. To incorporate the simultaneous epigenetic control of variant switching and gametocyte conversion, these were varied proportionally to determine the effects on infectiousness of their linked epigenetic control (Extended Experimental Procedures).

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

- The class II histone deacetylase, PfHda2, is essential in malaria parasites.

- Depletion of PfHda2 activates heterochromatic, variantly expressed genes such as var.

- PfHda2 regulates expression of genes required for initiation of sexual conversion.

- A molecular link between persistence and sexual conversion in malaria is revealed.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Katy Shaw Saliba and Deepali Ravel for aid with this work. Support for this research was provided by a National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship (B.I.C.), NIH T32 5T32HL007574-31, American Heart Association 13POST16850007 (K.M.S), HHMI fellowship of the Damon Runyon Cancer Research Foundation (B.F.C.K.), NIH/NIAID R21 AI105328 (M.M.), NIH R01 AI076276 with support from the Centre for Quantitative Biology (P50GM071508) (M.L.), Award U54GM088558 from the National Institute Of General Medical Sciences (L.M.C., C.O.B.) and a Burroughs Wellcome Fund New Investigator in the Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases Fellowship (M.T.D.).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

B.I.C. and K.M.S. designed and performed experiments, analyzed data and wrote the manuscript. R.H.Y.J. performed the phylogeneic, microarray and epigenetic mark analysis. L.M.C. performed the mathematical modeling. L.M.A. performed the microarray. M.G. performed the colocalization immunofluorescence. Y.L. performed the telomere restriction fragment blots. I.G. helped design gametocyte conversion assays. B.F.C.K. provided microarray analysis. M.M. supervised gametocyte conversion assays. M.L. supervised the microarray. C.O.B. supervised the modeling and wrote the manuscript. M.T.D. designed experiments, supervised the study and wrote the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information includes five supplemental figures with legends, two supplemental movies, four supplemental tables, extended experimental procedures and supplemental references.

REFERENCES

- Armstrong CM, Goldberg DE. An FKBP destabilization domain modulates protein levels in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Meth. 2007;4:1007–1009. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aygün O, Mehta S, Grewal SIS. HDAC-mediated suppression of histone turnover promotes epigenetic stability of heterochromatin. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2013;20:547–554. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker DA. Malaria gametocytogenesis. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2010;172:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruch DI, Pasloske BL, Singh HB, Bi X, Ma XC, Feldman M, Taraschi TF, Howard RJ. Cloning the P. falciparum gene encoding PfEMP1, a malarial variant antigen and adherence receptor on the surface of parasitized human erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:77–87. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bousema T, Drakeley C. Epidemiology and infectivity of Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax gametocytes in relation to malaria control and elimination. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24:377–410. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00051-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce MC, Alano P, Duthie S, Carter R. Commitment of the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum to sexual and asexual development. Parasitology 100 Pt. 1990;2:191–200. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000061199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushkin GG, Ratner DM, Cui J, Banerjee S, Duraisingh MT, Jennings CV, Dvorin JD, Gubbels M-J, Robertson SD, Steffen M, et al. Suggestive evidence for Darwinian Selection against asparagine-linked glycans of Plasmodium falciparum and Toxoplasma gondii. Eukaryotic Cell. 2010;9:228–241. doi: 10.1128/EC.00197-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brancucci, et al. Heterochromatin Protein 1 Secures Survival and Transmission of Malaria Parasites. Cell Host & Microbe. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2014.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Churcher TS, Bousema T, Walker M, Drakeley C, Schneider P, Ouédraogo AL, Basáñez M-G. Predicting mosquito infection from Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte density and estimating the reservoir of infection. Elife. 2013;2:e00626. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman BI, Ribacke U, Manary M, Bei AK, Winzeler EA, Wirth DF, Duraisingh MT. Nuclear repositioning precedes promoter accessibility and is linked to the switching frequency of a Plasmodium falciparum invasion gene. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;12:739–750. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2012.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domergue R, Castaño I, Las Peñas, De A, Zupancic M, Lockatell V, Hebel JR, Johnson D, Cormack BP. Nicotinic acid limitation regulates silencing of Candida adhesins during UTI. Science. 2005;308:866–870. doi: 10.1126/science.1108640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraisingh MT, Triglia T, Cowman AF. Negative selection of Plasmodium falciparum reveals targeted gene deletion by double crossover recombination. International Journal for Parasitology. 2002;32:81–89. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(01)00345-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duraisingh MT, Voss TS, Marty AJ, Duffy MF, Good RT, Thompson JK, Freitas-Junior LH, Scherf A, Crabb BS, Cowman AF. Heterochromatin silencing and locus repositioning linked to regulation of virulence genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Cell. 2005;121:13–24. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorin JD, Martyn DC, Patel SD, Grimley JS, Collins CR, Hopp CS, Bright AT, Westenberger S, Winzeler E, Blackman MJ, et al. A plant-like kinase in Plasmodium falciparum regulates parasite egress from erythrocytes. Science. 2010;328:910–912. doi: 10.1126/science.1188191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzikowski R, Li F, Amulic B, Eisberg A, Frank M, Patel S, Wellems TE, Deitsch KW. Mechanisms underlying mutually exclusive expression of virulence genes by malaria parasites. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:959–965. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7401063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Research. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eksi S, Morahan BJ, Haile Y, Furuya T, Jiang H, Ali O, Xu H, Kiattibutr K, Suri A, Czesny B, et al. Plasmodium falciparum gametocyte development 1 (Pfgdv1) and gametocytogenesis early gene identification and commitment to sexual development. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8:e1002964. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flueck C, Bártfai R, Volz J, Niederwieser I, Salcedo-Amaya AM, Alako BTF, Ehlgen F, Ralph SA, Cowman AF, Bozdech Z, et al. Plasmodium falciparum heterochromatin protein 1 marks genomic loci linked to phenotypic variation of exported virulence factors. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000569. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freitas-Junior LH, Hernandez-Rivas R, Ralph SA, Montiel-Condado D, Ruvalcaba-Salazar OK, Rojas-Meza AP, Mâncio-Silva L, Leal-Silvestre RJ, Gontijo AM, Shorte S, et al. Telomeric heterochromatin propagation and histone acetylation control mutually exclusive expression of antigenic variation genes in malaria parasites. Cell. 2005;121:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozinger CM, Hassig CA, Schreiber SL. Three proteins define a class of human histone deacetylases related to yeast Hda1p. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 1999;96:4868–4873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikadai H, Shaw Saliba K, Kanzok SM, McLean KJ, Tanaka TQ, Cao J, Williamson KC, Jacobs-Lorena M. Transposon mutagenesis identifies genes essential for Plasmodium falciparum gametocytogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2013;110:E1676–E1684. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217712110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang L, Mu J, Zhang Q, Ni T, Srinivasan P, Rayavara K, Yang W, Turner L, Lavstsen T, Theander TG, et al. PfSETvs methylation of histone H3K36 represses virulence genes in Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2013;499:223–227. doi: 10.1038/nature12361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kafsack BFC, Rovira-Graells N, Clark TG, Bancells C, Crowley VM, Campino SG, Williams AE, Drought LG, Kwiatkowski DP, Baker DA, et al. A transcriptional switch underlies commitment to sexual development in malaria parasites. Nature. 2014;507:248–252. doi: 10.1038/nature12920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavazec C, Sanyal S, Templeton TJ. Expression switching in the stevor and Pfmc-2TM superfamilies in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;64:1621–1634. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rubio JJ, Gontijo AM, Nunes MC, Issar N, Hernandez-Rivas R, Scherf A. 5′ flanking region of var genes nucleate histone modification patterns linked to phenotypic inheritance of virulence traits in malaria parasites. Mol. Microbiol. 2007;66:1296–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.06009.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Rubio JJ, Mâncio-Silva L, Scherf A. Genome-wide analysis of heterochromatin associates clonally variant gene regulation with perinuclear repressive centers in malaria parasites. Cell Host Microbe. 2009;5:179–190. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon MJ, Gandon S, Read AF. Virulence evolution in response to vaccination: the case of malaria. Vaccine 26 Suppl. 2008;3:C42–C52. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.04.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel P-Y, Hoang AN, Goldowitz I, Potashnikova D, Hamza B, Vorobjev I, Ghiran I, Toner M, Irimia D, Ivanov AR, et al. Malaria-infected erythrocyte-derived microvesicles mediate cellular communication within the parasite population and with the host immune system. Cell Host Microbe. 2013;13:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinsen ES, Perkins SL, Schall JJ. A three-genome phylogeny of malaria parasites (Plasmodium and closely related genera): evolution of life-history traits and host switches. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2008;47:261–273. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenzie FE, Bossert WH. The optimal production of gametocytes by Plasmodium falciparum. J. Theor. Biol. 1998;193:419–428. doi: 10.1006/jtbi.1998.0710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick CJ, Dzikowski R, Imamura H, Chuang J, Deitsch K, Duraisingh MT. The effect of Plasmodium falciparum Sir2a histone deacetylase on clonal and longitudinal variation in expression of the var family of virulence genes. International Journal for Parasitology. 2010;40:35–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2009.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick CJ, Huttenhower C, Buckee C, Amambua-Ngwa A, Gomez-Escobar N, Walther M, Conway DJ, Duraisingh MT. Epigenetic dysregulation of virulence gene expression in severe Plasmodium falciparum malaria. J. Infect. Dis. 2012;205:1593–1600. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jis239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miao J, Li J, Fan Q, Li X, Li X, Cui L. The Puf-family RNA-binding protein PfPuf2 regulates sexual development and sex differentiation in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. J. Cell. Sci. 2010;123:1039–1049. doi: 10.1242/jcs.059824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mideo N, Day T. On the evolution of reproductive restraint in malaria. Proc. Biol. Sci. 2008;275:1217–1224. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2007.1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nalaskowski MM, Deschermeier C, Fanick W, Mayr GW. The human homologue of yeast ArgRIII protein is an inositol phosphate multikinase with predominantly nuclear localization. Biochem. J. 2002;366:549–556. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Painter HJ, Altenhofen LM, Kafsack BFC, Llinás M. Whole-genome analysis of Plasmodium spp. Utilizing a new agilent technologies DNA microarray platform. Methods Mol. Biol. 2013;923:213–219. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-026-7_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V, Mazitschek R, Coleman B, Nguyen C, Urgaonkar S, Cortese J, Barker RH, Greenberg E, Tang W, Bradner JE, et al. Identification and Characterization of Small Molecule Inhibitors of a Class I Histone Deacetylase from Plasmodium falciparum. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:2185–2187. doi: 10.1021/jm801654y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petter M, Lee CC, Byrne TJ, Boysen KE, Volz J, Ralph SA, Cowman AF, Brown GV, Duffy MF. Expression of P. falciparum var genes involves exchange of the histone variant H2A.Z at the promoter. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001292. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Toledo K, Rojas-Meza AP, Mâncio-Silva L, Hernández-Cuevas NA, Delgadillo DM, Vargas M, Martínez-Calvillo S, Scherf A, Hernandez-Rivas R. Plasmodium falciparum heterochromatin protein 1 binds to tri-methylated histone 3 lysine 9 and is linked to mutually exclusive expression of var genes. Nucleic Acids Research. 2009;37:2596–2606. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollitt LC, Mideo N, Drew DR, Schneider P, Colegrave N, Reece SE. Competition and the evolution of reproductive restraint in malaria parasites. Am. Nat. 2011;177:358–367. doi: 10.1086/658175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prucca CG, Slavin I, Quiroga R, Elías EV, Rivero FD, Saura A, Carranza PG, Luján HD. Antigenic variation in Giardia lamblia is regulated by RNA interference. Nature. 2008;456:750–754. doi: 10.1038/nature07585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ralph SA, Scheidig-Benatar C, Scherf A. Antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum is associated with movement of var loci between subnuclear locations. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.a. 2005;102:5414–5419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408883102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Recker M, Buckee CO, Serazin A, Kyes S, Pinches R, Christodoulou Z, Springer AL, Gupta S, Newbold CI. Antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum malaria involves a highly structured switching pattern. PLoS Pathog. 2011;7:e1001306. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Regev-Rudzki N, Wilson DW, Carvalho TG, Sisquella X, Coleman BM, Rug M, Bursac D, Angrisano F, Gee M, Hill AF, et al. Cell-cell communication between malaria-infected red blood cells via exosome-like vesicles. Cell. 2013;153:1120–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rovira-Graells N, Gupta AP, Planet E, Crowley VM, Mok S, Ribas de Pouplana L, Preiser PR, Bozdech Z, Cortés A. Transcriptional variation in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Genome Research. 2012;22:925–938. doi: 10.1101/gr.129692.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudenko G, Blundell PA, Dirks-Mulder A, Kieft R, Borst P. A ribosomal DNA promoter replacing the promoter of a telomeric VSG gene expression site can be efficiently switched on and off in T. brucei. Cell. 1995;83:547–553. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90094-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saksouk N, Bhatti MM, Kieffer S, Smith AT, Musset K, Garin J, Sullivan WJ, Cesbron-Delauw M-F, Hakimi M-A. Histone-modifying complexes regulate gene expression pertinent to the differentiation of the protozoan parasite Toxoplasma gondii. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:10301–10314. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.23.10301-10314.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salanti A, Staalsoe T, Lavstsen T, Jensen ATR, Sowa MPK, Arnot DE, Hviid L, Theander TG. Selective upregulation of a single distinctly structured var gene in chondroitin sulphate A-adhering Plasmodium falciparum involved in pregnancy-associated malaria. Mol. Microbiol. 2003;49:179–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo-Amaya AM, van Driel MA, Alako BT, Trelle MB, van den Elzen AMG, Cohen AM, Janssen-Megens EM, van de Vegte-Bolmer M, Selzer RR, Iniguez AL, et al. Dynamic histone H3 epigenome marking during the intraerythrocytic cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:9655–9660. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902515106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scherf A, Hernandez-Rivas R, Buffet P, Bottius E, Benatar C, Pouvelle B, Gysin J, Lanzer M. Antigenic variation in malaria: in situ switching, relaxed and mutually exclusive transcription of var genes during intra-erythrocytic development in Plasmodium falciparum. Embo J. 1998;17:5418–5426. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestrini F, Lasonder E, Olivieri A, Camarda G, van Schaijk B, Sanchez M, Younis Younis S, Sauerwein R, Alano P. Protein export marks the early phase of gametocytogenesis of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1437–1448. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900479-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinha A, Hughes KR, Modrzynska KK, Otto TD, Pfander C, Dickens NJ, Religa AA, Bushell E, Graham AL, Cameron R, et al. A cascade of DNA-binding proteins for sexual commitment and development in Plasmodium. Nature. 2014;507:253–257. doi: 10.1038/nature12970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JD, Chitnis CE, Craig AG, Roberts DJ, Hudson-Taylor DE, Peterson DS, Pinches R, Newbold CI, Miller LH. Switches in expression of Plasmodium falciparum var genes correlate with changes in antigenic and cytoadherent phenotypes of infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:101–110. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90056-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JJ, Torigoe SE, Maxson J, Fish LC, Wiley EA. A class II histone deacetylase acts on newly synthesized histones in Tetrahymena. Eukaryotic Cell. 2008;7:471–482. doi: 10.1128/EC.00409-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonda S, Morf L, Bottova I, Baetschmann H, Rehrauer H, Caflisch A, Hakimi M-A, Hehl AB. Epigenetic mechanisms regulate stage differentiation in the minimized protozoan Giardia lamblia. Mol. Microbiol. 2010;76:48–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2010.07062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su XZ, Heatwole VM, Wertheimer SP, Guinet F, Herrfeldt JA, Peterson DS, Ravetch JA, Wellems TE. The large diverse gene family var encodes proteins involved in cytoadherence and antigenic variation of Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes. Cell. 1995;82:89–100. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90055-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor LH, Read AF. Regul, editor. Why so few transmission stages? Reproductive restraint by malaria parasites. Parasitol. Today. 1997;13:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(97)89810-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonkin CJ, Carret CK, Duraisingh MT, Voss TS, Ralph SA, Hommel M, Duffy MF, Silva LMD, Scherf A, Ivens A, et al. Sir2 paralogues cooperate to regulate virulence genes and antigenic variation in Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2009;7:e84. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trager W, Jensen JB. Human malaria parasites in continuous culture. Science. 1976;193:673–675. doi: 10.1126/science.781840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verstrepen KJ, Fink GR. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms underlying cell-surface variability in protozoa and fungi. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2009;43:1–24. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volz JC, Bártfai R, Petter M, Langer C, Josling GA, Tsuboi T, Schwach F, Baum J, Rayner JC, Stunnenberg HG, et al. PfSET10, a Plasmodium falciparum methyltransferase, maintains the active var gene in a poised state during parasite division. Cell Host Microbe. 2012;11:7–18. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss TS, Healer J, Marty AJ, Duffy MF, Thompson JK, Beeson JG, Reeder JC, Crabb BS, Cowman AF. A var gene promoter controls allelic exclusion of virulence genes in Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Nature. 2006;439:1004–1008. doi: 10.1038/nature04407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voss TS, Mini T, Jenoe P, Beck H-P. Plasmodium falciparum possesses a cell cycle-regulated short type replication protein A large subunit encoded by an unusual transcript. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:17493–17501. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200100200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warimwe GM, Fegan G, Musyoki JN, Newton CRJC, Opiyo M, Githinji G, Andisi C, Menza F, Kitsao B, Marsh K, et al. Prognostic indicators of life-threatening malaria are associated with distinct parasite variant antigen profiles. Sci Transl Med. 2012;4:129ra45. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3003247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Fischle W, Sugiyama T, Allis CD, Grewal SIS. The nucleation and maintenance of heterochromatin by a histone deacetylase in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. 2005;20:173–185. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young JA, Fivelman QL, Blair PL, la Vega, de P, Le Roch KG, Zhou Y, Carucci DJ, Baker DA, Winzeler EA. The Plasmodium falciparum sexual development transcriptome: a microarray analysis using ontology-based pattern identification. Molecular and Biochemical Parasitology. 2005;143:67–79. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.