Abstract

The antioxidant activities of vidarikand (Pueraria tuberosa), shatavari (Asparagus racemosus) and ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) extracts (aqueous and ethanolic) were evaluated and compared with BHA using β-carotene bleaching assay, DPPH assay and Rancimat method. Phenolic contents of ethanolic extracts of herbs were high compared to their aqueous extracts. The ethanolic extracts showed more antioxidant activity (β-carotene–linoleic acid model system) than their aqueous counterparts. In DPPH system also, ethanolic extracts were superior to that of aqueous extracts. The ethanolic extracts of the herbs were more effective in preventing the development of the peroxide value and conjugated diene in ghee compared to their aqueous extracts. Ethanolic extracts of herbs showed the higher induction period as compared to their aqueous counter parts in the Rancimat. Antioxidant activity of the herbs decreased in the order vidarikand > ashwagandha > shatavari. Thus, the ethanolic extract of vidarikand was having the maximum antioxidant activity among all the herbs.

Keywords: Ghee (Butter oil), Vidarikand (Pueraria tuberosa), Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus), Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) antioxidant activity, Radical-scavenging activity, Phenolic content, Rancimat

Introduction

Ghee considered as the Indian name for clarified butterfat, is usually prepared from cow milk or buffalo milk or combination thereof and has a pleasing and appetizing aroma. About 30–35 % of the milk produced in India (112 million tons in 2009–2010) is converted into ghee (Varkey 2010). Ghee is the most widely used milk product in the Indian sub-continent and is considered as the supreme cooking and frying medium. It has considerably longer shelf-life as compared to other indigenous dairy products. Ghee undergoes oxidative degradation during storage, resulting in alteration of major quality parameters such as colour, flavour, aroma and nutritive value affecting suitability for consumption. The primary autoxidation products are hydroperoxides, which have no taste and flavour, while their degradation products, called secondary oxidation products have detectable taste and flavor (Choe and Min 2006).

In recent decades, there has been great interest in screening essential oils and various plant extracts for natural antioxidants because of their good antioxidant properties. In order to prolong the storage of foods, several synthetic antioxidants such as butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) and butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) are used currently, but these substances are inappropriate for chronic human consumption, as recent publications have mentioned their toxic properties for human health and the environment (Ito et al. 1986; Stich 1991). Hence, the development of alternative antioxidants of natural origin has attracted considerable attention and is thought to be a desirable development (Jia et al. 2007). The majority of published work in the area of natural antioxidants has focused on tocopherols (Wagner and Elmadfa 1998). Crude extracts of herbs and spices and other plant materials rich in phenolics are of increasing interest in the food industry because they retard oxidative degradation of lipids and thereby improve the quality and nutritional value of food. However, addition of herbal extracts in dairy products is a newly emerged area (Rowan 2000). Merai et al. (2003) reported that water-insoluble fraction of Tulsi (Ocimum sanctum L.) leaves possess good antioxygenic properties and phenolic substances present in Tulsi leaves were the main factors in extending the oxidative stability of ghee (butterfat).

Pueraria tuberosa (vidarikand), Asparagus racemosus (shatavari) and Withania somnifera (ashwagandha) belonging to family fabaceae, asparagaceae and solanaceae, respectively have an esteemed place in Ayurveda. The active components of Pueraria tuberosa are puerarin, daidzein, genistein and daidzin (Debra et al. 2006; Kim et al. 2003; Pandey et al. 2007); Asparagus racemosus are steroidal glycosides, saponins, polyphenols, flavonoids, galactose and vitamins (Thomsen 2002) and Withania somnifera are steroidal lactones (withanolides), sitoindosides and steroidal alkaloids. All these herbs have been reported to possess several therapeutic properties. They are also known to possess antioxidant activity in vivo condition (Verma et al. 2009) as well as in animal models (Bhatnagar et al. 2005). Tanwar et al. (2008) reported hypolipidemic activity of Pueraria tuberosa as elucidated by concurrent feeding to Wister rats. The levels of total serum cholesterol, triglycerides, VLDL and LDL cholesterol, raised (152 to 285 %) by feeding cholesterol, were subsequently lowered significantly, mainly due to isoflavonoids present in it. Asparagus racemosus is reported to have immunostimulant, antihepatotoxic and antioxytocic activities (Goyal et al. 2003), and antioxidant and anti-diarrheal activities in laboratory animals (Bhatnagar et al. 2005). Withania somnifera is one of the major herbal components of geriatric tonics, this plant is also claimed to have potent aphrodisiac, rejuvenative and life prolonging properties (Sharma 1997).

Though a large number of plants worldwide show strong antioxidant activities (Baratto et al. 2003; Katalynic et al. 2006) the effect of antioxidant properties of herbs extracts on oxidative stability of ghee (butter fat) have not been elucidated before. The objectives of this study were to: (1) Evaluate and compare total phenolic content, antioxidant capacity using β-carotene bleaching assay, and radical-scavenging activity using DPPH assay of the herb extracts and (2) To determine the effect of added herb extracts on oxidative stability of ghee during accelerated oxidation condition.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and reagents

β-carotene, linoleic acid, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazylhydrate free radical (DPPH), Folin–Ciocalteu’s reagent and Tween-40 were obtained from Sigma Chemical Co., USA. Organic solvents, namely, chloroform and gallic acid (Loba Chemie Pvt. Ltd., Mumbai, India) and ethyl acetate (RFCL Ltd, New Delhi, India) were used. Sodium carbonate was obtained from Qualigens fine chemicals, Mumbai, India.

Herb extracts

The aqueous and ethanolic extract of herbs (Pueraria tuberosa, Asparagus racemosus and Withania somnifera) was obtained from National Botanical Research Institute (NBRI), Lucknow,Uttar Pradesh, India.

Preparation of aqueous extract

Extraction from the plant material was carried with distilled water by heating in hot water bath. The extracted material was filtered and concentrated using rotary evaporator at 55–60 °C. Concentrated material of herb was lyophilised to obtain lyophilised aqueous extract of herbs. The resulting dried plant material in the form of powder was used for further study.

Preparation of ethanolic extract

Extraction from the plant material was carried with 95 % ethanol at room temperature by cold percolation process. The extracted material was filtered and concentrated using rotary evaporator at 45 °C. Concentrated material of herb was lyophilised to obtain lyophilised ethanolic extract of herbs. The dried plant material in the form of powder was used for further study.

Synthetic antioxidants

The synthetic antioxidant, butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA) was obtained from Sigma chemicals, USA.

Addition of antioxidants

The aqueous herb extracts were initially added to cream @ 1.0 % (w/w) and then ghee was prepared by direct creamery method. Ethanolic extracts of herbs as well as BHA were added directly to the freshly prepared ghee at the rate of 0.5 % and 0.02 % (w/w), respectively. Ghee without any added herb extract served as control.

Total phenolic content

Total phenolic content of herb extracts were analyzed by Folin Ciocalteu method (Kahkonen et al.1999). 400 μl of appropriately diluted sample was taken in a test tube. 2,000 μl of diluted Folin-Ciocalteu’s reagent was added to it and mixed with vortex mixer. After 3 minutes 1,600 μl of sodium carbonate solution was added and incubated under dark at room temperature for 30 min. For blank preparation 400 μl of distilled water was taken instead of sample. Absorbance of the samples was measured against blank at 765 nm using Ultraviolet–visible spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter DU 720, USA).

β-carotene–linoleic acid model system

The antioxidant activity of herb extracts and synthetic antioxidants was determined according to the procedure of Marco (1969) with the following modification. (Ethanol was used as a solvent instead of methanol for sample preparation). The herb extracts (200 ppm), and BHA (200 ppm) were dissolved in ethanol and incorporated into a β-carotene–linoleic acid model system independently and the activity was monitored spectrophotometrically at 470 nm.

Radical-scavenging activity by DPPH model system

The radical-scavenging activity of herb extracts and synthetic antioxidants was determined according to the procedure of Blois (1958) with minor modification (Ethanol was used as a solvent instead of methanol for sample preparation). The compounds at a concentration of 200 ppm in methanol (1 ml) were taken in test tubes and 4 ml of 0.1 mM methanolic solution of DPPH was added to these tubes and shaken vigorously. The tubes were allowed to stand at 27 °C for 20 min. The control was prepared, as above without any extract and methanol was used for the baseline correction. Optical densities (OD) of the samples were measured at 517 nm. Radical-scavenging activity was expressed as the inhibition percentage.

Radical-scavenging activity of ghee samples by DPPH assay

The capacity of antioxidants to quench DPPH radicals in ghee was determined before and after accelerated oxidation tests (Espin et al. 2000). Ethyl acetate was used as a better solvent for hydrophobic compounds. 0.2 ml of the ghee sample was added to 3.8 ml of ethyl acetate to obtain 4 ml of the mixture followed by addition of 1 ml of DPPH (6.09 × 10−5 mol/L) solution in ethyl acetate (total volume, 5 ml). After 10 min. had elapsed the absorbance was measured at 520 nm wavelength. The reference sample used was 1 ml of DPPH solution and 4 ml ethyl acetate. Radical-scavenging activity was expressed as the inhibition percentage.

Peroxide value

Peroxide value of ghee samples were determined by the method as described in IS: 3508 (1966). 1 gm of molten fat was weighed accurately into a 250 ml glass stoppered Erlenmeyer flask. 20 ml of mixed solvent was added and flask was then swirled until the dissolution of fat. 0.5 ml of saturated KI was then added to the flask and kept undisturbed for 1 min. The mixture was heated on boiling water bath up to boiling and tip of the flask was closed with finger after vapours started to form and boiling was continued for 30 sec. Generated vapors condensed under stream of cold tap water. 25 ml of distilled water was added followed by 0.5 ml of 1 % starch indicator. At this point dark blue/brown color appeared. The mixture was then titrated against 0.002 N Na2S2O3 until disappearance of color. Blank test without sample was also conducted simultaneously.

Conjugated dienes

Conjugated dienes were determined as per the method of AOAC (1995). 0.1 g of the sample was weighted into a 100 ml volumetric flask and volume was made up using iso-octane. Absorbance reading of this iso-octane solution was taken at 233 nm by using spectrophotometer against a solvent blank i.e. iso-octane.

Accelerated test - rancimat 743

The resistance to auto-oxidation was measured using Rancimat 743 (Metrohm, Herisau,Switzerland) instrument at 120 °C with airflow rate of 20 L/h. The oxidative stability was expressed as induction period (h) or oxidative stability index (h). A 3.0 g sample of completely melted ghee weighed accurately into each of the reaction vessels. The vessels were then placed in the heating block of the Rancimat apparatus. The reaction vessels were then connected to the measuring vessels via connecting tube. 60 ml of deionised water was measured into each of the measuring vessels, containing the electrodes. The measuring vessels were also placed in the Rancimat apparatus. All parts were connected to the apparatus as per the operating instructions, and the test was carried out until the endpoints of all the samples were reached, with a maximum allowable limit of 48 hours.

Statistical analysis

Data reported were expressed as mean values of three replicates with standard errors. In experiments, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a subsequent least significant difference (LSD) test was applied to test for any significant differences (P < 0.05) in the mean values as described by Snedecor and Cochran (1994).

Results and discussion

Ghee samples stored in hot air oven at 80 ± 1 °C were analyzed at regular intervals of 0, 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18 and 21 days for peroxide value, conjugated dienes and radical-scavenging activity by DPPH assay. Accelerated stability test (Rancimat) was also used to determine the induction period (IP) or oxidative stability index (OSI) of freshly prepared ghee samples.

The results obtained after the addition of herb extracts (aqueous and ethanolic) to ghee were compared with those obtained with BHA, the most widely used synthetic antioxidantin the food industry.

Total Phenolic content

The amount of total phenolics, varied widely in herb extracts and results are presented in Table 1. The calculation of total phenolic content of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of herbs was carried out using the standard curve of gallic acid and presented as mg gallic acid equivalents (GAE) per gram. The ethanolic extracts of vidarikand, shatavari and ashwagandha contained higher amount of phenolic compounds (44.8 ± 0.14, 24.99 ± 0.74 and 23.95 ± 0.37 mg GAE/g of herb extract, respectively) than their aqueous counterparts (24.95 ± 0.18, 14.49 ± 0.44 and 20.88 ± 0.41 mgGAE/g, respectively). Thus phenolic content was highest in the ethanolic extract of vidarikand followed by ethanolic extract of shatavari, aqueous extract of vidarikand, ethanolic extract of ashwagandha, aqueous extract of ashwagandha and aqueous extract of shatavari. Significant differences (P > 0.05) between the results of aqueous and ethanolic extracts of herbs were likely due to difference in the solubility of antioxidative compounds inthe water and ethanol and/or due to the difference in the temperatures used in their preparation. The amount of polyphenols in the extract is also dependent on the extraction method.

Table 1.

Total phenolic content, antioxidant activity and radical scavenging activity (%Inhibition) of herb extracts (ethanolic and aqueous)

| Herb extracts | Phenolic content (mg of GAE/g) | Antioxidant activities at 200 ppm Concentration | % Inhibition at 200 ppm Concentration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vidarikand ethanolic | 44.8 ± 0.14a | 86.0 ± 0.13a | 72.8 ± 0.34a |

| Vidarikand aqueous | 24.9 ± 0.18b | 84.4 ± 0.18a | 51.1 ± 0.44b |

| Shatavari ethanolic | 24.9 ± 0.74b | 67.7 ± .15b | 62.8 ± 0.34c |

| Shatavari aqueous | 14.4 ± 0.44c | 49.9 ± 0.19c | 40.1 ± 0.44d |

| Ashwagandha ethanolic | 23.9 ± 0.37b | 63.2 ± 0.14d | 60.1 + 0.23e |

| Ashwagandha aqueous | 20.8 ± 0.41e | 44.3 ± 0.11e | 44.2 + 0.36f |

| BHA | – | 89.9 ± 0.16f | 91.2 ± 0.23g |

Data are presented as means of three determinations ± SEM (n = 3). Means with different superscripts letters are significantly different (P < 0.05). GAE Gallic acid equivalent, BHA Butylated hydroxyl anisol

β-carotene–linoleic acid model system

The antioxidant activity of herbs (aqueous and ethanolic), as well as butylated hydroxyl anisole (BHA) were evaluated at 200 ppm using the β-carotene–linoleic acid coupled oxidation model system and the results are presented in Table 1. The ethanolic extracts of vidarikand, shatavari and ashwagandha showed more antioxidant activity (86.05 ± 0.13 %, 63.22 ± 0.14 % and 67.70 ± 0.15 %, respectively) than their aqueous extracts (84.44 ± 0.18 %, 44.33 ± 0.11%and 49.93 ± 0.19 %, respectively). This difference between antioxidant activity of ethanolic and aqueous extracts of herbs might be attributed to the higher temperature used in the preparation of the later causing damage to some compounds with antioxidant activity and/or different solubility of antioxidant compounds in water and ethanol (Philip et al. 2010).

Radical-scavenging activity by DPPH model system

The radical-scavenging activity of herbs (aqueous and ethanolic), were evaluated at 200 ppm in the DPPH system and the results are presented in Table 1. It is evident from the table that radical-scavenging potential of ethanolic extracts of herbs was significantly higher than the aqueous extracts of herbs, but significantly lower than BHA, with a percent inhibition of 91.21 ± 0.23 %.

Highest radical scavenging potential among herbs was observed in ethanolic extract of vidarikand whereas aqueous extract of shatavari showed the weakest radical-scavenging potential. Several studies showed that there is a difference between antioxidant capacity of ethanolic and aqueous extract of herbs. For example, Philip et al. (2010) reported that the ethanolic extract of A. paniculata leaves had a higher stable DPPH free radical scavenging activity (86.87 %) and higher content of total phenolic compounds (75.86 ± 0.82 mg of GAE/g) than its aqueous extract.

A combination of different methods of antioxidant activity evaluation can give more reliable results than a single method alone. Several studies (Cai et al. 2004; Beta et al. 2005; Tawaha et al. 2007; Othman et al. 2007) found a good correlation between total content of phenolic compounds and the antioxidant activity of different plants. Thus, we can conclude that our results were consistent with the above findings except for the ethanolic extract of ashwagandha and aqueous extract of vidarikand, which were in agreement with the findings of Nsimba et al. (2005) who showed that the antioxidant activity of Chenopodium quinoa and Amaranthusspp. seeds, determined using three different assays (carotene bleaching, FRAP and DPPH), poorly correlated with the total content of phenolic compounds. There were also non-significant relationships between the antioxidant activities (FRAP, DPPH and carotene bleaching assays) and total contents of phenolic compounds for fifteen genotypes of selected Turkey Zizyphus jujube Mill Fruits (Kamiloğlu et al. 2009).

Accelerated oxidation studies

Peroxide value

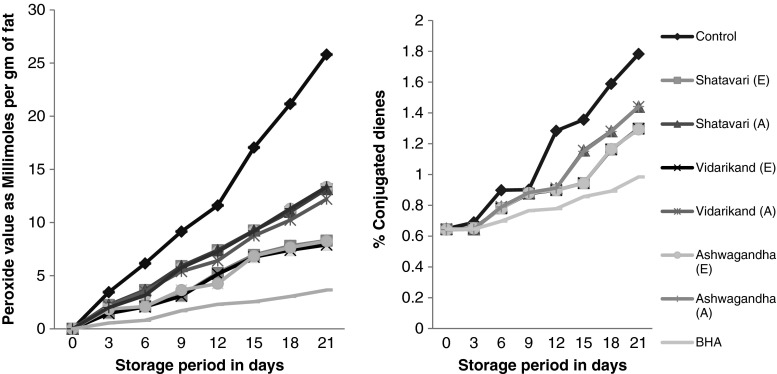

Peroxide value (PV) represents primary reaction products of lipid oxidation, which can be measured by their ability to liberate iodine from potassium iodide. It is considered to represent the quantity of active oxygen (mg) contained in 1 g of lipid. The results obtained after addition of herbs(aqueous and ethanolic), to ghee on the peroxide development are presented in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Changes in peroxide value and conjugated dienes of BHA and ghee containing herb extracts during storage at 80 ± 1 °C. (n = 3) E Ethanolic; A Aqueous; BHA Butylated hydroxyl anisol

It was observed that the herb extracts (aqueous and ethanolic) significantly (P < 0.05) lowered the peroxide value throughout 21 days of storage at 80 ± 1 °C as compared to the control. Our findings were in agreement with Zia-ur-Rehman et al. (2003) who reported that addition of ginger extract to sunflower oil greatly inhibited the rise in peroxides under accelerated conditions. In southern Indian villages, people use the fresh leaves of Moringa oleifera during preparation of cow and buffalo ghee to increase its shelf life (Perumal and Becker 2003). However, ghee incorporated with aqueous extracts of herbs showed a significant (P < 0.05) rise in peroxide value as compared with their ethanolic extracts, which indicates that ghee containing ethanolic extracts were more effective than the ghee containing aqueous extracts of herbs in retarding peroxides development. The peroxide values of ghee containing any extract of herbs was significantly (P > 0.05) higher than the synthetic (BHA) throughout 21 days of storage at 80 ± 1 °C as shown in Fig. 1. However, Merai et al. (2003) reported that addition of 0.6 % of silica gel charcoal treated fraction of Tulsi leaves powder to ghee was more effective than the BHA at 0.02 % until the peroxide value of 5 meq of peroxide oxygen was reached.

Conjugated dienes

According to Silva et al. (1999) the polyunsaturated fatty acid oxidation occurs with the formation of hydroperoxides and the double bond displacement followed by the formation of consequent conjugated dienes (CD). Over 90 % of hydroperoxides formed by lipoperoxidation have a conjugated dienic system resulting from stabilization of the radical state by double bond rearrangement. These relatively stable compounds absorb in the UV range (235 nm) forming a shoulder on the main absorption peak of nonconjugated double bonds (200–210 nm), so they can be measured in the UV spectrum by absorption spectrophotometry (Gillam et al. 1931).

Figure 1 shows that herb extracts (aqueous and ethanolic) were significantly (P < 0.05) capable of lowering conjugated dienes formation throughout 21 days of storage at 80 ± 1 °C as compared to the control, but significantly (P < 0.05) less effective in retarding conjugated dienes formation as compared to BHA. The ethanolic extract of herbs significantly (P < 0.05) lowered conjugated dienes formation as compared to the aqueous extract of same herbs. Inhibition of conjugated dienes by natural antioxidants were also reported by Frankel et al. (1996) and Siddiq et al. (2005) who assessed the antioxidant activity of rosemary and Moringa oleifera in several oil types and observed inhibited diene formation as compared to the control.

Evaluation of radical scavenging activity (RSA) of ghee samples towards DPPH radicals

The ghee incorporated with herb extracts, BHA and control ghee were evaluated for the potential to quench the DPPH radicals before oxidation and after completing the accelerated tests and the results are presented in Table 2. It is evident from Table 2 that on zero day (before oxidation), the radical scavenging activity of ghee incorporated with ethanolic and aqueous extracts of all the herbs showed more radical scavenging activity compared to the control ghee. However, the radical scavenging activity of ghee containing BHA had the maximum antioxidant activity among all the additives used.

Table 2.

Radical-scavenging activity and oxidative stability of herb extracts and BHA incorporated ghee samples

| Samples | Storage period in days | Induction Period (h) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 21 | ||

| Control | 20.6 ± 0.31a | 5.4 ± 0.29a | 10.5 ± 1.01a |

| BHA | 82.9 ± 0.43b | 74.8 ± 0.51b | 20.6 ± 0.92f |

| Vidarikand ethanolic | 62.0 ± 0.45c | 43.9 ± 0.38c | 17.9 ± 1.01c |

| Vidarikand aqueous | 58.7 ± 0.57d | 37.8 ± 0.15d | 14.7 ± 1.09b |

| Shatavari ethanolic | 46.0 ± 0.45e | 39.9 ± 0.38e | 16.8 ± 0.17c |

| Shatavari aqueous | 33.7 ± 0.57f | 25.8 ± 0.15f | 13.5 ± 0.14b |

| Ashwagandha ethanolic | 38.9 ± 0.31g | 33.7 ± 0.22g | 15.5 ± 0.27ce |

| Ashwagandha aqueous | 25.6 ± 0.14h | 20.6 ± 0.20h | 15.5 ± 0.27ce |

Data are presented as means of three determinations ± SEM (n = 3). Means with different superscripts letters in a column (a,b,c) are significantly different (P < 0.05). BHA Butylated hydroxyl anisol

Ghee incorporated with ethanolic extracts of herbs showed stronger activity in quenching DPPH radicals in system both before and after oxidation as compared to their aqueous extracts. This could be due to presence of higher amount of total phenolic compound in ethanolic extract of herbs. Furthermore, the radical scavenging activity of ghee added with herb extracts (ethanolic and aqueous) showed a significantly lower value than with BHA. Before and after the accelerated storage of the samples (i.e. on zero day and 21st day) at 80 ± 1 °C, the ability to quench free DPPH radicals was in the following order : BHA > vidarikand (ethanolic) > vidarikand (aqueous) > shatavari (ethanolic) > ashwagandha (ethanolic) > shatavari (aqueous) > ashwagandha (aqueous) > control.

It can be concluded that BHA had the strongest activity in quenching DPPH radicals in system before and after oxidation. In the same system shatavari (aqueous) extract had the lowest antioxidant activity and a very low capacity to quench radicals both before and after oxidation.

Evaluation of antioxidative potential of ghee samples by using Rancimat 743

The effect of herb extracts (ethanolic and aqueous) and BHA incorporation on oxidative stability of ghee was evaluated by Rancimat equipment and results are presented in Table 2. The induction time was used as a major indicator of antioxidative potential of antioxidants used. The induction period (IP) is also known as oxidative stability index (OSI) measured as the time required to reach an endpoint of oxidation corresponding to either a level of detectable rancidity or a sudden change in the rate of oxidation (Frankel 1993; Presa-Owens and Lopez-Sabater 1995).

The ethanolic extracts of herbs were found to be more effective in stabilizing ghee against oxidative deterioration as compared to their aqueous extracts. However, induction periods of both aqueous and ethanolic extracts of herbs added ghee was found to be significantly higher than that of control ghee. Nahak and Sahu (2010) reported that phenolic compounds are considered to be the most important antioxidative components of herb and other plant materials, and a good correlation exist between the concentrations of plant phenolics and the total antioxidant capacities. BHA (IP 20.14 ± 0.28) added ghee also showed significantly higher (P < 0.05) antioxidative effectiveness as compared to herbs (ethanolic and aqueous) extracts added ghee.

The antioxidative effectiveness of BHA added ghee was found to be significantly higher (P < 0.05) than all the other ghee samples. The antioxidant activity of herb extracts and BHA in ghee as measured by Rancimat was in the following order: BHA > vidarikand(ethanolic) > shatavari(ethanolic) > ashwagandha(ethanolic) > vidarikand(aqueous) > shatavari(aqueous) > ashwagandha(aqueous) > control.

Conclusion

A positive correlation between antioxidant potential of the herbs and their total phenolic content was found except for the ethanolic extract of ashwagandha and aqueous extract of vidarikand. Total phenolic content, antioxidant activity, determined by the β-carotene linoleic acid model assay and radical scavenging activity, determined by the DPPH assay was more for the ethanolic extract of herbs as compared to their aqueous extracts. Ghee incorporated with the herbs ethanolic extract showed better radical scavenging activity as compared to the ghee incorporated with the aqueous extract of the same. Aqueous and ethanolic extracts of herbs were found to be capable of retarding oxidative degradation in ghee but were less effective than BHA. Ethanolic extracts of herbs showed the higher induction period as compared to their aqueous extracts in the Rancimat. Hence all the herbs could be used as a natural antioxidant to preserve the food system apart from providing other beneficial benefits and would be preferred over BHA to minimize adverse effects on mankind.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Agriculture Innovation Project (component 4: Basic and strategic research C30029), Indian Council of Agricultural Research. New Delhi, India.

References

- AOAC (1995) Official methods of analysis of AOAC International, 16th edn, Vol. II pp 988

- Baratto MC, Tattini M, Galardi C, Pinelli P, Romani A, Visiolid F, Basosi R, Poqni R. Antioxidant activity of Galloyl quinic derivatives isolated from Pistacialentiscusleaves. Free Radic Res. 2003;37:405–412. doi: 10.1080/1071576031000068618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beta T, Nam S, Dexter JE, Sapirstein HD. Phenolic content and antioxidant activity of pearled wheat and roller-milled fractions. Cereal Chem. 2005;82(4):390–393. doi: 10.1094/CC-82-0390. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bhatnagar M, Sisodiya SS, Bhatnagar R (2005) Antiulcer and antioxidant activity of Asparagus racemosus WILLD and Withania somnifera DUNAL in rats. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci 1056:261–270 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Blois MS. Antioxidant determination by the use of stable free radical. Nature. 1958;181:1199–1200. doi: 10.1038/1811199a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cai Y, Luo Q, Sun M, Corke H. Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds of 112 traditional Chinese medicinal plants associated with anticancer. Life Sci. 2004;74:2157–2184. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe E, Min DB. Mechanisms and factors for lipid oxidation. Compr Rev Food Sci. 2006;F5:169–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1541-4337.2006.00009.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Debra L, Bemis JL, Capodice JE, Costello GC, Vorys A, Dev S. A selection of prime ayurvedic plant drugs: ancient—modern concordance. New Delhi: Anamaya Pub; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Espin JC, Soler-Rivas C, Wichers HJ. Characterization of the total free radical scavenger capacity of vegetable oils and oil fractions using 2, 2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl radical. J Agr Food Chem. 2000;48:648–656. doi: 10.1021/jf9908188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel EN. In search of better methods to evaluate natural antioxidants and oxidative stability in food lipids. Trends Food Sci Tech. 1993;4:220–225. doi: 10.1016/0924-2244(93)90155-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Frankel EN, Huang SW, Prior E, Aeschbach R. Evaluation of antioxidant activity of rosemary extracts, carnosol and carnosic acid in bulk vegetable oils and fish oil and their emulsions. J Sci Food Agric. 1996;72:201–208. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0010(199610)72:2<201::AID-JSFA632>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gillam AE, Heilbron IM, Hilditch TP, Morton RA. Spectrographic data of natural fats and their fatty acids in relation to vitamin A. Biochemical J. 1931;25:30–38. doi: 10.1042/bj0250030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goyal RK, Singh J, Lal H (2003) Asparagus racemosus – an update. Indian J Med Res 57:408–414 [PubMed]

- IS: 3508 (1966) Indian standards, methods for sampling and test for ghee (butter fat). Bureau of Indian Standards, New Delhi

- Ito N, Hirose M, Fukushima H, Tsuda T, Shirai T, Tatenatsu M. Studies on antioxidants: their carcinogenic and modifying effects on chemical carcinogens. Food Chem Toxicol. 1986;24:1071–1092. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(86)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia ZB, Tao F, Guo L, Tao GJ, Ding XL. Antioxidant properties of extracts from juemingzi (Cassia tora L.) evaluated in vitro. LWT. 2007;40:1072–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2006.05.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kahkonen MP, Hopia AI, Vuorela HJ. Antioxidant activity of plant extracts containing phenolic compounds. J Agr Food Chem. 1999;47:3954–3962. doi: 10.1021/jf990146l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamiloğlu O, Ercisli S, Sengül M, Toplu C, Serçe S. Total phenolics and antioxidant activity of jujube (Zizyphus jujube Mill.) genotypes selected from Turkey. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:303–307. [Google Scholar]

- Katalynic V, Milos M, Kulisic T, Jukic M. Screening of 70 medicinal plant extracts for antioxidant capacity and total phenols. Food Chem. 2006;94:550–557. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2004.12.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim C, Shin S, Ha H, Kim JM. Study of substance changes in flowers of Pueraria thunbergiana Benth during storage. Arch Pharmacol Res. 2003;26:210–213. doi: 10.1007/BF02976832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco GJ. A rapid method for evaluation of antioxidants. J Am Oil Chem Soc. 1969;46:594–598. [Google Scholar]

- Merai M, Boghra VR, Sharma RS. Extraction of antioxigenic principles from Tulsi leaves and their effects on oxidative stability of ghee. J Food Sci Tech. 2003;40:52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Nahak G, Sahu RK. Antioxidant activity in bark and roots of Neem (Azadirachta indica) and Mahaneem (Melia azedarach) Cont J Pharm Sci. 2010;4:28–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nsimba R, Kikuzaki H, Konishi Y. Antioxidant activity of various extracts and fractions of Chenopodium quinoa and Amaranthus spp. seeds. Food Chem. 2005;106:760–766. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.06.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Othman A, Ismail A, Ghani NA, Adenan I. Antioxidant capacity and phenolic content of cocoa beans. Food Chem. 2007;100:1523–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2005.12.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey N, Chaurasia JK, Tiwari OP, Tripathi YB. Antioxidant properties of different fractions of tubers from Pueraria tuberosaLinn. Food Chem. 2007;105:219–222. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.03.072. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perumal S, Becker K. Antioxidant properties of various solvent extracts of total phenolic constituents from three agroclimatic origins of Drumstick tree leaves. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51:2144–2155. doi: 10.1021/jf020444+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip K, Rafat A, Muniandy S. Antioxidant potential and content of phenolic compounds in ethanolic extracts of selected parts of Andrographis paniculata. J Med Plants Res. 2010;4:197–202. doi: 10.3923/rjmp.2010.197.205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Presa-Owens S, Lopez-Sabater MC. Shelf-life prediction of an Infant formula using an accelerated stability test (Rancimat) J Agric Food Chem. 1995;43:2879–2882. doi: 10.1021/jf00059a020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan C. Extracting the best from herbs. Food Eng Int. 2000;25:31–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma PV (1997). Dravyaguna Vigyan, Chowkambha Sanskrit Sansthan

- Siddiq A, Anwar F, Manzoor M, Fatima A. Antioxidant activity of different solvent extract of Moringa Oleifera leaves under accelerated storage of sunflower oil. Asian J Plant Sci. 2005;4:630–635. doi: 10.3923/ajps.2005.630.635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva FA, Borges MF, Ferreira AA. Methods for the evaluation of the degree of lipid oxidation and the antioxidant activity. Quimica Nova. 1999;22:94–103. doi: 10.1590/S0100-40421999000100016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snedecor GW, Cochran WG. Statistical methods. 8. New Delhi: Affiliated East–west Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Stich HF. The beneficial and hazardous effects of simple phenolic compounds. Mutat Res. 1991;259:307–324. doi: 10.1016/0165-1218(91)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanwar YS, Goyal S, Ramawat KG. Hypolipidemic effects of tubers of Indian kudzu (Pueraria tuberosa) J Herbal Med Toxicol. 2008;2:21–25. [Google Scholar]

- Tawaha K, Alali FQ, Gharaibeh M, Mohammad M, El-Elimat T. Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of selected Jordanian plant species. Food Chem. 2007;104:1372–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2007.01.064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomsen M (2002) Shatavari- Asparagus racemosus. http://www.phytomedicine.com.au/files/articles/shatavri.pdf, accessed on 26/04/2011

- Varkey TK (2010) India’s milk production rose to 112 m tonnes last fiscal. The Economic Times. http://articles.economictimes.indiatimes.news/275788221milk-production-milk-prices-cattle-feed, accessed on 26/04/2011

- Verma SK, Jain V, Vyas A, Singh DP. Protection against stress induced myocardial ischemia by Indian kudzu (Pueraria tuberosa) - a case study. J Herbal Med Toxicol. 2009;3:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner KH, Elmadfa I. Effects of tocopherols and their mixtures on the oxidative stability of olive oil and linseed oil under heating. Eur J Lipid Sci Tech. 1998;103:624–629. [Google Scholar]

- Zia-ur-Rehman, Salariya A, Mand HF. Antioxidant activity of ginger extract in sunflower oil. J Food Sci Agr. 2003;83:624–629. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.1318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]