Abstract

Mass-specific basal metabolic rate (mass-specific BMR), defined as the resting energy expenditure per unit body mass per day, is an important parameter in energy metabolism research. However, a mechanistic explanation for magnitude of mass-specific BMR remains lacking. The objective of the present study was to validate the applicability of a proposed mass-specific BMR model in healthy adults. A mechanistic model was developed at the organ-tissue level, mass-specific BMR = Σ(Ki × Fi), where Fi is the fraction of body mass as individual organs and tissues, and Ki is the specific resting metabolic rate of major organs and tissues. The Fi values were measured by multiple MRI scans and the Ki values were suggested by Elia in 1992. A database of healthy non-elderly non-obese adults (age 20 – 49 yrs, BMI <30 kg/m2) included 49 men and 57 women. Measured and predicted mass-specific BMR of all subjects was 21.6 ± 1.9 (mean ± SD) and 21.7 ± 1.6 kcal/kg per day, respectively. The measured mass-specific BMR was correlated with the predicted mass-specific BMR (r = 0.82, P <0.001). A Bland-Altman plot showed no significant trend (r = 0.022, P = 0.50) between the measured and predicted mass-specific BMR, versus the average of measured and predicted mass-specific BMR. In conclusion, the proposed mechanistic model was validated in non-elderly non-obese adults and can help to understand the inherent relationship between mass-specific BMR and body composition.

Keywords: magnetic resonance imaging, organ, specific resting metabolic rate, tissue

Introduction

Estimates of daily energy requirements are crucial for the control and prevention of over- or under-nutrition due to excessive or insufficient intake of food energy [1]. Although daily energy requirements of free-living subjects can be measured using the doubly labeled water technique or indirect calorimetry, these methods are performed only under laboratory conditions and in small groups of individuals [2].

Mass-specific basal metabolic rate (mass-specific BMR), defined as the resting energy expenditure per unit body mass per day, is an important parameter in energy metabolism research. For example, mass-specific BMR of the Reference Man is 24.0 kcal/kg per day [3]. In young adult men and non-pregnant non-lactating women, daily energy requirements can be roughly calculated from mass-specific BMR by multiplying physical activity levels (PAL) and body mass. To simplify calculations, the PAL of adult population can be grouped as light, moderate or heavy, depending on subject’s occupational or other work [1]. For a 20 to 30-yrs-old female population with moderately active lifestyle and body mass of 55 kg, for example, the average mass-specific BMR and PAL are 23.7 kcal/kg per day and 1.85, respectively. The daily energy requirements of the population can be calculated as 23.7 × 1.85 × 55 = 2410 kcal/day.

Although mass-specific BMR is a cornerstone of daily energy requirements and body weight regulation, the concept of mass-specific BMR per se may not reflect the inherent relationship between energy expenditure and body composition. This gap in energy metabolism research stimulated us to explore the body composition basis of mass-specific BMR.

The aim of the present study was to develop and evaluate a mechanistic mass-specific BMR model at the organ-tissue level. We hypothesized that the magnitude of mass-specific BMR can be quantitatively explained by the combination of variables of the proposed model.

Methods

Model development

As all organs and tissues in the human body are metabolically active, whole-body resting energy expenditure (REE) can be represented by the sum of the products of individual organ/tissue masses (Ti) and the specific resting metabolic rate of individual organs and tissues (Ki) [4, 5],

| [1] |

As mass-specific BMR was defined as the resting energy expenditure per unit body mass (BM) per day, a mechanistic model can be developed from equation 1,

| [2] |

where Fi is the fraction of body mass as individual organs and tissues, and i is the number of individual organs and tissues (i = 1, 2, …, n).

According to equation 2, the magnitude of mass-specific BMR is dependent on the combination of two model variables, Fi and Ki. The Fi values of individual organs and tissues can be measured by multi-scan magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

The Ki values of healthy young adults were suggested by Elia [6], including 200 for liver, 240 for brain, 440 for heart and kidneys, 13 for skeletal muscle, 4.5 for adipose tissue and 12 for residual mass (all in kcal/kg per day). The Ki value of the residual mass is accounted for by average metabolic activities of skin, intestines, as well as bones, lungs and other organs and tissues present in small amounts.

According to equation 2 with the assumed stable Ki values suggested by Elia [6], a working formula for the mass-specific BMR (in kcal/kg per day) can be developed,

| [3] |

By using multiple scan MRI with assumed stable density of individual organs and tissues, we measured the fraction of body mass as liver, brain, heart, kidneys, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue [7]. The fraction of residual mass was calculated as one minus the sum of fractions of liver, brain, heart, kidneys, skeletal muscle and adipose tissue,

| [4] |

In the present study the mass-specific BMR model was assessed by examining the goodness of fit in healthy non-elderly non-obese adults. Specifically, the applicability of equation 3 was evaluated by comparing the predicted mass-specific BMR against the measured mass-specific BMR as the criterion.

Subjects

Existing mass-specific BMR and organ/tissue data were collected at the Institute of Human Nutrition and Food Science, Christian-Alberchts University, Kiel, Germany. The total study population (n = 106) included 49 men and 57 women. All of the subjects participated in earlier reported studies [8, 9]. IRB approvals were obtained and subjects signed an informed consent at the German site. In order to exclude the potential influences of growth, aging, adiposity, race and diseases, only non-elderly (20–49 years) non-obese (BMI <30.0 kg/m2) healthy Caucasians were included in this study.

Mass-specific BMR

The indirect calorimetry technique was applied to estimate REE in a post-absorptive state. No food or calorie containing beverage was consumed after 7 p.m. the night before study, until the REE and all body composition tests were completed the following morning. REE was measured between 7 a.m. and 9 a.m. with subjects resting comfortably on a bed with a plastic transparent ventilated hood placed over their heads for 30 min. Continuous gas exchange measurements (Vmax Spectra 29n, SensorMedics, Bithoven, The Netherlands) were made to analyze the rates of O2 consumption and CO2 production. The details of the REE measurement have been described [8]. The magnitude of mass-specific BMR was calculated as the ratio of REE to body mass.

Body composition

Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg in fasting subjects wearing minimal clothing. Height was measured with a stadiometer to the nearest 0.1 cm.

The masses of individual organs and tissues were obtained by summing pixels from images obtained with a 1.5-T Magnetom Vision MRI scanner (Siemens, Erlangen, Germany). The details of the MRI protocol for organs/tissues measurement have been previously described [8].

All MRI images were segmented manually by using TomoVision 4.3 Software (Slice-O-Matic, Montreal, Canada). Each organ and tissue was analyzed by the same observer who was blinded to the time point and subject identity. The intra-observer CVs based on comparison of repeated segmentations were 0.07% for liver, 1.8% for brain, 1.7% for heart and 1.0% for kidneys. The technical errors for measurement of the same scan on two separate days by the same observer were 0.7 ± 0.1% (mean ± SD) for skeletal muscle and 1.1 ± 1.2% for adipose tissue, respectively.

The fractions of body mass as individual organs and tissues (i.e., Fi) were calculated from the sum of all cross-sectional areas multiplied by the slice thickness and the gaps between slices [7],

| [5] |

where S is the cross-sectional area of individual organ and tissue; BM is body mass; d is the density of individual organ and tissue; g is the gap (distance) between consecutive images; i is the image number; and t is the thickness of each image.

Body composition (body fat mass and fat-free mass) was measured with a dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA) scanner (Hologic QDR 4500A, Waltham, MA, software version V8.26a:3). Subjects lay supine with arms and legs at their sides during the 10 min scan. The between-measurement technical error for fat in the same person is 1.2%. The %fat was calculated as the percentage of body mass as fat mass. In some subjects skeletal muscle and adipose tissue masses were calculated from DXA-estimation, as previously described [8, 10].

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics from the database were expressed as the group mean ± standard deviation (SD). The significance of differences in REE, mass-specific BMR, organs/tissues and body composition between the men and women were evaluated by Student’s t test, and the statistical significance was set at P <0.05. The applicability of the mechanistic mass-specific BMR model was tested by examining the association between measured and predicted mass-specific BMR with use of simple linear regression analysis. We explored for bias in the measured and predicted mass-specific BMR relation using the analysis of Bland and Altman [11]. Data was analyzed by using Microsoft EXCEL 2000 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) and SAS v8 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Subject characteristics

The characteristics and body composition of all subjects and the two gender groups are presented in Table 1. Body mass, height, BMI and fat-free mass were significantly greater in the men than in the women (all P <0.001). However, body fat mass and %fat were significantly lower in the men than in the women (all P <0.001).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics and body composition.

| All subjects | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 106 | 49 | 57 |

| Age (yrs) | 36.1 ± 10.4 | 38.6 ± 11.0 | 33.9 ± 9.3* |

| Body mass (kg) | 73.6 ± 12.4 | 81.6 ± 10.6 | 66.6 ± 9.2*** |

| Height (m) | 1.74 ± 0.08 | 1.80 ± 0.06 | 1.69 ± 0.06*** |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 24.1 ± 2.9 | 25.1 ± 2.6 | 23.2 ± 2.8*** |

| Fat (kg) | 17.9 ± 6.6 | 15.3 ± 6.5 | 20.3 ± 5.9*** |

| %Fat | 25.2 ± 8.4 | 19.2 ± 6.2 | 30.5 ± 6.3*** |

| Fat-free mass (kg) | 55.7 ± 11.7 | 66.3 ± 6.5 | 46.3 ± 5.6*** |

| Liver (kg) | 1.39 ± 0.25 | 1.54 ± 0.26 | 1.27 ± 0.18*** |

| Brain (kg) | 1.33 ± 0.11 | 1.40 ± 0.08 | 1.26 ± 0.09*** |

| Heart (kg) | 0.31 ± 0.08 | 0.37 ± 0.07 | 0.26 ± 0.06*** |

| Kidneys (kg) | 0.29 ± 0.06 | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.26 ± 0.05*** |

| Skeletal muscle (kg) | 26.6 ± 6.5 | 32.4 ± 3.7 | 21.5 ± 3.2*** |

| Adipose tissue (kg) | 19.4 ± 6.3 | 17.1 ± 6.2 | 21.4 ± 5.7*** |

| Residual mass (kg) | 24.3 ± 5.3 | 28.5 ± 4.3 | 20.7 ± 3.0*** |

All values are mean ± SD. Student t test between the men and women,

, P <0.05;

P <0.001.

Abbreviations: %fat, percentage of body mass as fat; BMI, body mass index.

Fractions of major organs and tissues (Fi)

The masses of four organs with high resting metabolic rate (i.e., liver, brain, heart and kidneys) and three tissues with low resting metabolic rate (i.e., skeletal muscle, adipose tissue and residuals) for all subjects and both gender groups are presented in Table 1. There were significant differences in adipose tissue mass (men < women, P <0.001) and in the masses of the other six organs and tissues (men > women, all P <0.001).

The fractions of body mass as the seven organs and tissues are presented in Table 2. There were no significant gender differences in Fliver and Fkidneys. However, there were significant differences in Fheart, FSM and Fresiduals (men > women, all P <0.001) and in Fbrain and FAT (men < women, all P <0.001).

Table 2.

Fractions of body mass as major organs and tissues.

| All subjects | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fliver | 0.0191 ± 0.0027 | 0.0189 ± 0.0025 | 0.0193 ± 0.0028 |

| Fbrain | 0.0185 ± 0.0029 | 0.0175 ± 0.0025 | 0.0193 ± 0.0029*** |

| Fheart | 0.0043 ± 0.0009 | 0.0046 ± 0.0010 | 0.0040 ± 0.0007*** |

| Fkidneys | 0.0039 ± 0.0007 | 0.0040 ± 0.0007 | 0.0039 ± 0.0006 |

| FSM | 0.359 ± 0.052 | 0.399 ± 0.036 | 0.323 ± 0.034*** |

| FAT | 0.265 ± 0.081 | 0.205 ± 0.055 | 0.318 ± 0.061*** |

| Fresidual | 0.330 ± 0.044 | 0.351 ± 0.041 | 0.312 ± 0.039*** |

All values are mean ± SD. Student t test between the men and women;

P <0.001.

Abbreviations: Fliver, fraction of body mass as liver; Fbrain, fraction of body mass as brain; Fheart, fraction of body mass as heart; Fkidneys, fraction of body mass as kidneys; FSM, fraction of body mass as skeletal muscle; FAT, fraction of body mass as adipose tissue; Fresidual, fraction of body mass as residual mass.

Measured and predicted mass-specific BMR

The measured REE and mass-specific BMR are 1581 ± 247 kcal/day (mean ± SD) and 21.6 ± 1.9 kcal/kg per day for all subjects, respectively (Table 3). There were significant differences in REE between the men and women (1780 ± 188 vs. 1407 ± 137 kcal/day, P <0.001). However, there were no significant differences in mass-specific BMR between the men and women (21.9 ± 1.7 vs. 21.3 ± 2.1 kcal/kg per day, P = 0.10).

Table 3.

Resting energy expenditure and mass-specific basal metabolic rate.

| All subjects | Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|---|

| REE (kcal/day) | 1581 ± 247 | 1780 ± 188 | 1407 ± 137*** |

| Measured mass-specific BMR (kcal/kg per day) | 21.6 ± 1.9 | 21.9 ± 1.7 | 21.3 ± 2.1 |

| Predicted mass-specific BMR (kcal/kg per day) | 21.7 ± 1.6 | 22.1 ± 1.6 | 21.3 ± 1.6* |

| Measured - Predicted mass-specific BMR | −0.06 ± 1.11 | −0.13 ± 1.12 | 0.01 ± 1.10 |

All values are mean ± SD. Student t test between the men and women;

, P <0.05;

P <0.001.

Abbreviations: measured mass-specific BMR, measured mass-specific basal metabolic rate; predicted mass-specific BMR, predicted mass-specific basal metabolic rate by equation 3; REE, resting energy expenditure.

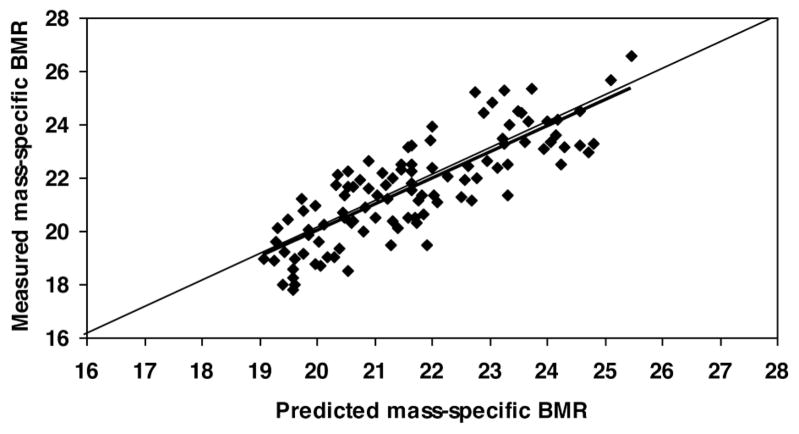

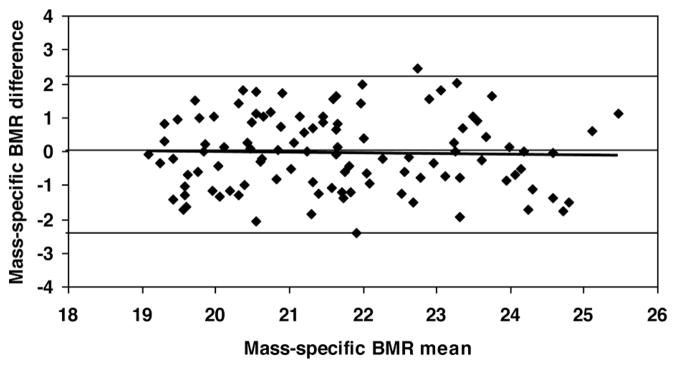

According to equation 3, predicted mass-specific BMR was calculated (Table 3). The predicted mass-specific BMR is correlated with measured mass-specific BMR in all subjects (Figure 1; r = 0.821, P <0.001). Differences between measured and predicted mass-specific BMR is −0.06 ± 1.10 kcal/kg per day with 95% CI from −2.3 to 2.2 kcal/kg per day. A Bland-Altman plot shows that there is no significant trend (r = 0.022, P = 0.50) between the difference of measured and predicted mass-specific BMR versus the average of measured and predicted mass-specific BMR for all subjects (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

The measured mass-specific basal metabolic rate versus predicted mass-specific basal metabolic rate (in kcal/kg per day). The linear regression line for all subjects is shown: measured mass-specific BMR = 0.985 × predicted mass-specific BMR + 0.27; r = 0.821, P <0.001; n = 106. Predicted mass-specific BMR was calculated by equation 3.

Figure 2.

The difference between measured and predicted mass-specific BMR versus the mean of measured and predicted mass-specific BMR (in kcal/kg per day). Mass-specific BMR difference = −0.0152 × mass-specific BMR mean + 0.27; r = 0.022, P >0.50; n = 106. Predicted mass-specific BMR was calculated by equation 3. The linear regression line, zero difference line and the lines representing 2 SDs for the differences (−2.3, 2.2 kcal/kg per day; indicated by the upper and lower lines) are shown.

Discussion

Whole body resting energy expenditure, as well as mass-specific BMR, are two important parameters in energy metabolism research [12]. In the present study a mechanistic mass-specific BMR model was developed which was then well evaluated in healthy young adults. We thus provided new insights into the fundamental linkage between mass-specific BMR and body composition at the organ-tissue level.

The human body contains heterogeneous organs and tissues in the characters of energy metabolism. According to the Ki values suggested by Elia [6], seven major organs and tissues can be divided into three sub-groups: four organs with high resting metabolic rate (i.e., liver, brain, heart and kidneys with Ki value from 200 to 440 kcal/kg per day), two tissues with Ki value of 12 – 13 kcal/kg per day (i.e., skeletal muscle and residuals), and adipose tissue with low Ki value of 4.5 kcal/kg per day.

Based on the measured Fi and Elia’s Ki values, we calculated the factorials of observed mass-specific BMR, i.e., Σ(Ki × Fi)/measured mass-specific BMR (Table 4). Although the four organs accounted for only about 4.5% of body mass, their contribution to mass-specific BMR was as high as ~55%. In contrast, although adipose tissue accounted as high as 21% and 32% of body mass in the men and women, respectively, its contribution to the mass-specific BMR was only 4.2% in the men and 6.7% in the women. In obese subjects with a large excess in body fat, however, the contribution of adipose tissue to mass-specific BMR could increase up to 10% or more [13].

Table 4.

Factorials of measured mass-specific basal metabolic rate.

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Fi | Σ (Ki × Fi)/mass-specific BMR | Fi | Σ(Ki × Fi)/mass-specific BMR | |

| 4 organs | 0.0450 | 0.536 | 0.0465 | 0.554 |

| SM + Residual | 0.750 | 0.428 | 0.635 | 0.372 |

| AT | 0.205 | 0.042 | 0.318 | 0.067 |

Abbreviations: 4 organs, the sum of liver, brain, heart and kidneys masses; AT, adipose tissue; Fi, fraction of body mass as major organs and tissues; Ki, specific resting metabolic rates of individual organ and tissue; mass-specific BMR, mass-specific basal metabolic rate in the men (21.9 kcal/kg per day) and women (21.3 kcal/kg per day); SM, skeletal muscle.

Previous observations showed that the magnitude of mass-specific BMR is not stable across adulthood, varying from 18.2 to 28.9 kcal/kg per day in men and from 16.8 to 26.9 kcal/kg per day in women (Table 5). For a given gender and body mass, mass-specific BMR is lower in elderly than in young adults, revealing that aging leads to a progressive decrease in mass-specific BMR. For a given gender and age range, mass-specific BMR is higher in underweight adults and lower in overweight and obese adults than in normal weight adults [1]. Although logically acceptable, these well-known observations have never been fully and quantitatively explained.

Table 5.

Mass-specific basal metabolic rate (in kcal/kg per day) for men and women with diverse age and body mass.

| Age (yrs) | Body mass (kg) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 45 | 50 | 55 | 60 | 65 | 70 | 75 | 80 | 85 | 90 | |

| Men | ||||||||||

| 18 – 29.9 | 28.9 | 27.6 | 26.6 | 25.7 | 24.9 | 24.3 | 23.7 | 23.2 | 22.7 | |

| 30 – 59.9 | 28.9 | 27.3 | 26.0 | 24.9 | 23.9 | 23.1 | 22.4 | 21.7 | 21.2 | |

| ≥60 | 23.5 | 22.4 | 21.5 | 20.8 | 20.1 | 19.5 | 19.1 | 18.6 | 18.2 | |

| Women | ||||||||||

| 18 – 29.9 | 25.6 | 24.6 | 23.7 | 22.9 | 22.3 | 21.8 | 21.3 | 20.9 | 20.5 | |

| 30 – 59.9 | 26.9 | 25.0 | 23.5 | 22.2 | 21.1 | 20.2 | 19.4 | 18.7 | 18.1 | |

| ≥60 | 23.7 | 22.3 | 21.1 | 20.1 | 19.2 | 18.5 | 17.9 | 17.3 | 16.8 | |

Data source: FAO/WHO/UNU, 2004 [Ref. 1].

According to the proposed mechanistic model (i.e., equation 2), the magnitude of mass-specific BMR could be explained by model variables operating jointly: Fi and Ki. There may be two possible explanations for the above observations. First, the fraction (Fi) of body mass as the four organs with high metabolic rate is lower in elderly and/or obese adults than in young normal-weight adults. Thus the decline of mass-specific BMR could be explained, at least partly, by the reduction in Fi values of the four organs that occurs with aging and/or high adiposity. Previous studies, however, suggested that even after adjusting for Fi values, the magnitude of mass-specific BMR may still be lower in elderly and/or obese adults compared with young normal-weight adults [14, 15].

Second, the specific metabolic rates (Ki) of individual organs and tissues may be lower in elderly and/or obese adults than in young normal-weight adults [16, 17]. In the present study, equation 3 was based on the assumption that the Ki values suggested by Elia [6] are stable across adulthood. Our recent studies revealed that the Ki values decline with aging and adiposity [18, 19]. This decline of Ki values could be explained, at least partly, by reduction in the cellularity of the four organs that occurs with aging and/or high adiposity [17, 20]. Further study is needed to evaluate its applicability of the proposed mass-specific BMR model in elderly and/or obese adults.

In conclusion, the proposed model delineated the physiological basis for the magnitude of mass-specific BMR in healthy young adults. This mechanistic model revealed the inherent relationship between mass-specific BMR and body composition at the organ-tissue level.

Acknowledgments

Supported by USA National Institute of Health Grant DK081633 and German Research Foundation, DFG Mu 714/8-3

We are grateful to those subjects who are included in this study. ZMW was responsible for all aspects of the study including study design, model development and manuscript writing. BS was responsible for MRI organs/tissues scan segmentation procedures. AB-W and MM provided existing database and were responsible for manuscript writing. This project was supported by awards USA DK081633 from the NIDDK, and German Research Foundation, DFG Mu 714/8-3. Each author declares no conflict of interest regarding any company or organization sponsoring this study. The content is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of NIDDK and German Research Foundation.

References

- 1.FAO/WHO/UNU. Report of Joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation. Rome: 2004. Human Energy Requirements; pp. 35–50. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Durnin JVGA. Energy requirements: general principles. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1996;50:S2–S10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Snyder WS, Cook MJ, Nasset ES, Karhausen LR, Howells GP, Tipton IH. Report of the Task Group on Reference Man. Oxford, United Kingdom: Pergamon Press; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gallagher D, Belmonte D, Deurenberg P, Wang ZM, Krasnow N, Pi-Sunyer FX, Heymsfield SB. Organ-tissue mass measurement allows modeling of REE and metabolically active tissue mass. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:E249–58. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.275.2.E249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang ZM, Heshka S, Zhang K, Boozer C, Heymsfield SB. Resting energy expenditure: Systematic organization and critique of prediction methods. Obes Res. 2001;9:331–6. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elia M. Organ and tissue contribution to metabolic rate. In: Kinney JM, Tucker HN, editors. Energy Metabolism: Tissue Determinants and Cellular Corollaries. New York: Raven Press; 1992. pp. 61–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ross R, Janssen I. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. In: Heymsfield SB, Lohman TG, Wang ZM, Going SB, editors. Human Body Composition. 2. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2005. pp. 89–108. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosy-Westphal A, Reinecke U, Schlorke T, Illner K, Kutzner D, Heller M, Muller MJ. Effect of organ and tissue masses on resting energy expenditure in underweight, normal weight and obese adults. Int J Obesity. 2004;28:72–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Later W, Bosy-Westphal A, Hitze B, Kossel E, Glüer CC, Heller M, Müller MJ. No evidence of mass dependency of specific organ metabolic rate in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1004–9. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/88.4.1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, Wang ZM, Heymsfield SB, Baumgartner RN, Gallagher D. Total-body skeletal muscle mass: Estimation by new dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry method. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:378–83. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.2.378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986;1:307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hulbert AJ, Else PL. Basal metabolic rate: history, composition, regulation, and usefulness. Physiol Biochem Zool. 2004;77:869–76. doi: 10.1086/422768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schutz Y, Jequier E. Resting energy expenditure, thermic effect of food, and total energy expenditure. In: Bray GA, Bouchard CB, editors. Handbook of Obesity. 2. New York and Basel: Marcel Dekker, Inc; 2004. pp. 615–29. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gallagher D, Allen A, Wang ZM, Heymsfield SB, Krasnow N. Smaller organ tissue mass in the elderly fails to explain lower resting metabolic rate. In Vivo Body Composition Studies. In: Yasumura S, Wang J, Pierson RN Jr, editors. Ann N Y Acad Sci. Vol. 904. 2000. pp. 449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Robert S, Dallal DE. Energy working paper No. 8R prepared for the joint FAO/WHO/UNU Expert Consultation on Energy in Human Nutrition. 2001. Energy requirements and aging. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Keys A, Taylor HL, Grande F. Basal metabolism and age of adult man. Metab. 1973;22:579–87. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(73)90071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wang ZM, Heshka S, Heymsfield SB, Shen W, Gallagher D. A cellular level approach to predicting resting energy expenditure across the adult years. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:799–806. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.4.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang ZM, Ying Z, Bosy-Westphal A, Zhang J, Schautz B, Later W, Heymsfield SB, Müller MJ. Specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues across adulthood: Evaluation by mechanistic model of resting energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:1369–77. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang ZM, Ying Z, Bosy-Westphal A, Zhang J, Schautz B, Later W, Heymsfield SB, Müller MJ. Evaluation of specific metabolic rates of major organs and tissues: Comparison between non-obese and obese women. Obesity. 2011 doi: 10.1038/oby.2011.256. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang ZM, Heshka S, Wang J, Gallagher D, Deurenberg P, Chen Z, Heymsfield SB. Metabolically-active portion of fat-free mass: A cellular body composition level modeling analysis. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:E49–E53. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00485.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]