Abstract

AIM: To evaluate the accuracy of methylation of genes in stool samples for diagnosing colorectal tumours.

METHODS: Electronic databases including PubMed, Web of Science, Chinese Journals Full-Text Database and Wanfang Journals Full-Text Database were searched to find relevant original articles about methylated genes to be used in diagnosing colorectal tumours. A quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies tool (QADAS) was used to evaluate the quality of the included articles, and the Meta-disc 1.4 and SPSS 13.0 software programs were used for data analysis.

RESULTS: Thirty-seven articles met the inclusion criteria, and 4484 patients were included. The sensitivity and specificity for the detection of colorectal cancer (CRC) were 73% (95%CI: 71%-75%) and 92% (95%CI: 90%-93%), respectively. For adenoma, the sensitivity and specificity were 51% (95%CI: 47%-54%) and 92% (95%CI: 90%-93%), respectively. Pooled diagnostic performance of SFRP2 methylation for CRC provided the following results: the sensitivity was 79% (95%CI: 75%-82%), the specificity was 93% (95%CI: 90%-96%), the diagnostic OR was 47.57 (95%CI: 20.08-112.72), the area under the curve was 0.9565. Additionally, the results of accuracy of SFRP2 methylation for detecting colorectal adenomas were as follows: sensitivity was 43% (95%CI: 38%-49%), specificity was 94% (95%CI: 91%-97%), the diagnostic OR was 11.06 (95%CI: 5.77-21.18), and the area under the curve was 0.9563.

CONCLUSION: Stool-based DNA testing may be useful for noninvasively diagnosing colorectal tumours and SFRP2 methylation is a promising marker that has great potential in early CRC diagnosis.

Keywords: Colorectal carcinoma, Colorectal adenoma, Stool, Methylation, Meta-analysis

Core tip: The analysis of stool methylation markers as a non-invasive test is important for the early diagnosis of colorectal tumours. However, no consensus has been reached with regard to the role of stool methylation markers in colorectal tumour diagnosis. We performed a meta-analysis of 37 articles, and the pooled results showed that stool methylation markers could be used as a valuable diagnostic and predictive tool for colorectal tumours, and that SFRP2 methylation serves as a promising marker with great potential in early colorectal cancer diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in Western countries[1,2]. A 5-year survival rate for stage I CRC has reached 90%[3], but less than 10% for CRC cases who have distant metastases[4]. However, most CRC patients are diagnosed in the middle or late stages because no typical symptoms for the early stage of CRC exist[5]. Therefore, the diagnosis of CRC in early stages has great importance for reducing CRC mortality.

Early diagnosis of colorectal cancer will help to reduce mortality and the costs for surgery. Currently, the colonoscopy screening test is of high efficacy, but the acceptability of this procedure in the general public is rather low. As an available non-invasive method, faecal testing has a unique advantage when compared to other screening modalities. Although faecal occult blood testing (FOBT) has been confirmed to reduce mortality due to CRC, the test has little or no impact on the incidence of CRC because of its low-level sensitivity to adenoma[6], i.e., a sensitivity of only 10%-20%[7]. Compared to FOBT, the most important advantage of a methylation marker test in stool samples is its higher accuracy and sensitivity for the diagnosis of premalignant lesions of CRC[8].

DNA methylation often occurs in the early stages of CRC, and many studies have been performed on the diagnosis of colorectal tumours by determining the methylation of genes in stool samples. However, the results of these studies are variable although inspiring. Thus, this meta-analysis will be conducted to assess the accuracy of the detection of colorectal tumours by the methylation of genes in stool samples.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Search strategy

A literature search was performed independently by two investigators (Zhang H and Qi J) using the following databases: Pubmed, Web of Science, Chinese Journals Full-Text Database and Wanfang Journals Full-Text Database. All references that were cited in these studies and all published reviews were also searched. All English and Chinese references for analysis were published before January 2014. The following keywords were used in the search strategy: “colon/rectal/colorectal”, “cancer/tumours”, “stool”, and “methylation”. In this meta-analysis, 2 × 2 tables were constructed from each study for the true-positive, false-negative, and true-negative and false-positive values.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Eligible studies were required to meet all of the following criteria: (1) the data were independent; (2) the CRC was diagnosed using DNA methylation analysis in stool sample; (3) the patients were diagnosed with colorectal cancer or colorectal adenomas by pathology; and (4) the colonoscopy result of the control individuals was normal.

Exclusion criteria for this meta-analysis were as follows: (1) studies on secondary CRC or primary CRC with other organ metastases; and (2) studies on CRC patients receiving chemotherapy or curative surgery.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The following data were extracted from each study: author, year of publication, country or region, sample size, the name of genes, the detection method of methylation and the study design. The data were independently extracted by two investigators (Zhang H and Qi J), and discrepancies were solved by a third investigator (Zhu YQ) and collective discussion. Quality Assessment of Studies of Diagnostic Accuracy (QUADAS)[9] was used to assess the quality of the primary studies with diagnostic accuracy, and quality scoring was appraised based on the empirical evidence, the experts’ opinions and the formal consensus. Score of 1, 0 and -1 were given to the articles that were in compliance with the standards completely, unclear or out of standards, respectively, and the full score was 14.

Statistical analysis

All statistics were calculated and then combined using a random-effects model and 95%CI as effect measurements. The diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) reflects the relationship between the result of the diagnostic test and the disease. The summary receiver operation characteristic (SROC) curve displays the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity and represents a global summary of test performance. We used the Q-value, which is the intersection point of the SROC curve with a diagonal line from the left upper corner to the right lower corner of the receiver operation characteristic (ROC) space, which corresponds to the highest value of sensitivity and specificity for the test. The positive likelihood ratio (PLR) represents the value by which the odds of the disease increase when a test is positive, whereas the negative likelihood ratio (NLR) shows the value by which the odds of the disease decrease when a test is negative. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the χ2 test, and alpha significance testing was performed at the two-tailed 0.05 level. The professional statistical software programs (Meta-DiSc 1.4 and SPSS 13.0) were used for analysis. Publication bias was assessed by Egger analysis.

RESULTS

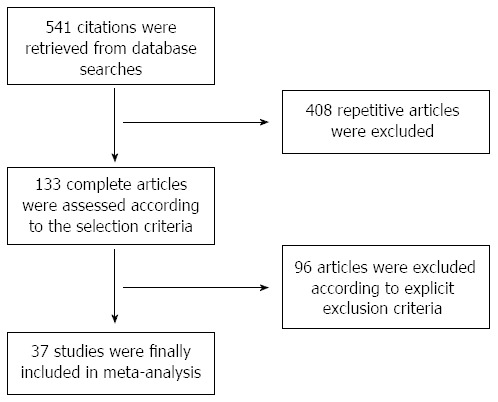

The literature search retrieved 541 citations, 408 of which were excluded because they were duplicates. Of the 133 potentially eligible studies, 96 publications were excluded because they did not investigate colorectal tumour or human stool studies (n = 21), included no diagnostic value studies (n = 20), were reviews (n = 27) or had overlapping data (n = 28). Finally, 37 studies that focused on the target patient spectrum were included (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study selection.

Study characteristics

Of the 37 studies, 7 were Chinese and 30 were English, and they included 4484 patients (Table 1). These studies were performed in 10 countries or regions (including China, the United States, the Netherlands, Spain, Japan, Germany, Iran, Hong Kong, Austria and South Korea). In these studies, 34 evaluated CRC, and 26 evaluated colorectal adenoma. Twenty-four studies focused on the methylation of a single gene, and the other 13 studies involved the methylation of multiple genes.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the included studies in the meta-analysis and quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy scores

| Ref. | Country/region | Methylation of genes | n |

CRC |

Adenoma |

Normal |

Blind design | Detection method | QUADAS score | |||

| + | - | + | - | + | - | |||||||

| Ahlquist et al[10] 2012 | Ireland | Vimentin/NDRG4/BMP3/TFPI2 | 98 | 26 | 4 | 18 | 4 | 5 | 41 | Yes | QuARTS | 11 |

| Bosch et al[11] 2011 | The Netherlands | PHACTR3 | 185 | 40 | 25 | 6 | 13 | 4 | 97 | Unclear | qMSP | 10 |

| GATA4 | 160 | 29 | 11 | 3 | 16 | 6 | 95 | |||||

| OSMR | 185 | 25 | 40 | 4 | 15 | 7 | 94 | |||||

| Ahlquist et al[12] 2011 | Ireland | PHACTR3 | 639 | 214 | 38 | 51 | 43 | 29 | 264 | Yes | QuARTS | 11 |

| Azuara et al[13] 2010 | Spain | RARB2/P16/MGMT/APC | 98 | 25 | 13 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 20 | Yes | MS-MCA | 10 |

| RARB2 | 85 | 11 | 23 | 7 | 31 | 0 | 13 | |||||

| P16 | 77 | 9 | 21 | 6 | 28 | 0 | 13 | |||||

| MGMT | 80 | 9 | 19 | 3 | 34 | 0 | 15 | |||||

| APC | 77 | 9 | 19 | 9 | 25 | 0 | 15 | |||||

| Tang et al[14] 2011 | China | SFRP2 | 262 | 142 | 27 | 29 | 34 | 2 | 28 | Yes | MSP | 9 |

| Baek et al[15] 2009 | South Korea | Vimentin/MGMT/MLH1 | 149 | 45 | 15 | 31 | 21 | 5 | 32 | Yes | MSP | 9 |

| MLH1 | 149 | 18 | 42 | 6 | 46 | 0 | 37 | |||||

| Vimentin | 149 | 23 | 37 | 8 | 44 | 0 | 37 | |||||

| MGMT | 149 | 31 | 29 | 19 | 33 | 5 | 32 | |||||

| Li et al[16] 2009 | United States | Vimentin | 80 | 9 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 36 | Unclear | Methyl-BEAMing | 5 |

| Melotte et al[17] 2009 | The Netherlands | NDRG4 | 150 | 42 | 33 | NR | NR | 3 | 72 | Yes | qMSP | 11 |

| Ausch et al[18] 2009 | United States | IGTA4 | 37 | NR | NR | 7 | 2 | 6 | 22 | Unclear | qMSP | 4 |

| Hellebrekers et al[19] 2009 | The Netherlands | GATA4 | 150 | 44 | 31 | NR | NR | 9 | 66 | Yes | qMSP | 10 |

| Mayor et al[20] 2009 | Spain | EN1 | 60 | 8 | 22 | NR | NR | 1 | 29 | Unclear | MS-MCA | 7 |

| Kim et al[21] 2009 | United States | OSMR/SFRP1 | 42 | 12 | 8 | 6 | 11 | 0 | 5 | Yes | qMSP | 9 |

| OSMR | 201 | 35 | 54 | 2 | 14 | 4 | 92 | |||||

| SFRP1 | 52 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 15 | |||||

| Nagasaka et al[22] 2009 | Japan | SFRP2 | 253 | 53 | 31 | 18 | 38 | 9 | 104 | Unclear | COBRA | 10 |

| RASSF2 | 253 | 38 | 46 | 7 | 49 | 6 | 107 | |||||

| Glöckner et al[23] 2009 | United States | TFPI2 | 129 | 44 | 14 | 7 | 19 | 2 | 43 | Yes | qMSP | 12 |

| Wang et al[24] 2008 | China | SFRP2 | 133 | 60 | 9 | 21 | 13 | 2 | 28 | Yes | MethyLight | 8 |

| Oberwalder et al[25] 2008 | Australia | SFRP2 | 19 | NR | NR | 6 | 7 | 0 | 6 | Yes | MethyLight | 9 |

| Itzkowitz et al[26] 2008 | United States | Vimentin | 80 | 9 | 13 | 9 | 11 | 2 | 36 | Yes | MSP | 13 |

| Huang et al[27] 2007 | China | SFRP2/HPP1/MGMT | 97 | 50 | 2 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 23 | Yes | MSP | 8 |

| SFRP2 | 97 | 49 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 1 | 23 | |||||

| HPP1 | 97 | 37 | 15 | 12 | 9 | 0 | 24 | |||||

| MGMT | 97 | 25 | 27 | 6 | 15 | 0 | 24 | |||||

| Itzkowitz et al[28] 2007 | United States | Vimentin/HLTF | 162 | 31 | 9 | NR | NR | 19 | 103 | Yes | MSP | 13 |

| HLTF | 162 | 15 | 25 | NR | NR | 9 | 113 | |||||

| Vimentin | 162 | 29 | 11 | NR | NR | 16 | 106 | |||||

| Abbaszadegan et al[29] 2007 | Hong kong | p16 | 45 | 5 | 20 | NR | NR | 0 | 20 | Unclear | MSP | 8 |

| Zhang et al[30] 2007 | Germany | SFRP1 | 44 | 16 | 4 | 7 | 0 | 2 | 15 | Yes | MSP | 9 |

| Leung et al[31] 2007 | Hong kong | SFRP2/MGMT/MLH1/HLTF/ATM/APC | 75 | 16 | 4 | 18 | 7 | 3 | 27 | Yes | MSP | 13 |

| SFRP2 | 75 | 6 | 14 | 3 | 22 | 2 | 28 | |||||

| MGMT | 75 | 4 | 16 | 3 | 22 | 0 | 30 | |||||

| MLH1 | 75 | 4 | 16 | 3 | 22 | 0 | 30 | |||||

| HLTF | 75 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 1 | 29 | |||||

| ATM | 75 | 5 | 15 | 5 | 20 | 0 | 30 | |||||

| APC | 75 | 4 | 16 | 4 | 21 | 0 | 30 | |||||

| Petko et al[32] 2005 | United States | MGMT/CDKN2A/MLH1 | 48 | NR | NR | 16 | 13 | 7 | 12 | Yes | MSP | 9 |

| CDKN2A | 48 | NR | NR | 9 | 20 | 3 | 16 | |||||

| MGMT | 48 | NR | NR | 14 | 15 | 5 | 14 | |||||

| MLH1 | 48 | NR | NR | 0 | 29 | 2 | 17 | |||||

| Lenhard et al[33] 2005 | Germany | HIC1 | 71 | 11 | 15 | 4 | 9 | 0 | 32 | Yes | MSP | 11 |

| Chen et al[34] 2005 | United States | Vimentin | 263 | 43 | 51 | 6 | 44 | 8 | 111 | Yes | MSP | 11 |

| Müller et al[35] 2004 | Australia | SFRP2/SFRP5 | 39 | 20 | 3 | NR | NR | 8 | 8 | Unclear | MethyLight | 5 |

| SFRP2 | 39 | 19 | 4 | NR | NR | 4 | 12 | |||||

| SFRP5 | 39 | 18 | 5 | NR | NR | 5 | 11 | |||||

| Xu et al[36] 2012 | China | SFRP2 | 90 | 20 | 10 | 15 | 15 | 1 | 29 | Unclear | MSP | 5 |

| Kang et al[37] 2011 | China | MGMT/MAL/CDKN2A | 119 | 64 | 5 | 17 | 7 | 2 | 24 | Unclear | MSP | 7 |

| MAL | 119 | 54 | 15 | 14 | 10 | 1 | 25 | |||||

| CDKN2A | 119 | 36 | 33 | 10 | 14 | 0 | 26 | |||||

| MGMT | 119 | 38 | 31 | 9 | 15 | 1 | 25 | |||||

| Zhang et al[38] 2011 | China | Vimentin/OSMR/TFPI2 | 107 | 52 | 8 | 13 | 4 | 4 | 26 | Unclear | MSP | 9 |

| Vimentin | 107 | 32 | 28 | 5 | 12 | 0 | 30 | |||||

| OSMR | 107 | 41 | 19 | 7 | 10 | 0 | 30 | |||||

| TFPI2 | 107 | 45 | 15 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 26 | |||||

| Fu et al[39] 2010 | China | Vimentin | 22 | 5 | 9 | NR | NR | 0 | 8 | Unclear | MSP | 5 |

| Ling et al[40] 2009 | China | P16 | 108 | 47 | 14 | 16 | 11 | 1 | 19 | Unclear | MSP | 7 |

| Cheng et al[41] 2007 | China | SFRP2 | 97 | 49 | 3 | 11 | 10 | 1 | 23 | Unclear | MSP | 5 |

| Zhao et al[42] | China | NDRG4 | 114 | 64 | 20 | NR | NR | 3 | 27 | Unclear | MSP | 6 |

| 2009 | ||||||||||||

| Chang et al[43] 2010 | South Korea | IGTA4/SFRP2/P16 | 86 | 21 | 9 | 18 | 7 | 1 | 30 | Yes | MSP | 8 |

| IGTA4 | 86 | 11 | 19 | 4 | 21 | 0 | 31 | |||||

| SFRP2 | 86 | 18 | 12 | 11 | 14 | 0 | 31 | |||||

| P16 | 86 | 12 | 18 | 6 | 19 | 1 | 30 | |||||

| Zhang et al[44] 2013 | China | SPG20 | 126 | 77 | 19 | NR | NR | 0 | 30 | Unclear | MSP | 7 |

| Carmona et al[45] 2013 | Spain | AGTR1/WNT2/SLIT2 | 102 | 50 | 14 | NR | NR | 4 | 34 | Unclear | Pyrosequencing | 10 |

| AGTR1 | 107 | 14 | 54 | NR | NR | 2 | 37 | |||||

| WNT2 | 91 | 21 | 31 | NR | NR | 1 | 38 | |||||

| SLIT2 | 108 | 37 | 34 | NR | NR | 2 | 35 | |||||

| 9-Sep | 61 | 7 | 28 | NR | NR | 0 | 26 | |||||

| Vimentin | 55 | 18 | 15 | NR | NR | 3 | 19 | |||||

| Guo et al[46] 2013 | China | FBN1 | 105 | 54 | 21 | NR | NR | 2 | 28 | MSP | 6 | |

+: Represents the number of individuals when the DNA methylation test was positive; -: Represents the number of individuals when the DNA methylation test was negative; MSP: Methylation-specific PCR; NR: Not reported; n: Total number.

Genes evaluated in these studies were mainly involved in three types of regulation pathways: the Wnt pathway, the DNA damage repair pathway and other pathways. Five genes of the Wnt pathway were involved in 11 studies: secreted frizzled-related proteins (SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP5), Adenomatous Polyposis Coli (APC) and WNT2. Two genes of the DNA damage repair pathway were involved in 7 of the studies: O-6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase (MGMT) and MutL Homologue 1(MLH1). Twenty-nine studies involved 22 genes of other pathways: Vimentin, Oncostain M Receptor-β (OSMR), Phosphatase and Actin Regulator 3 (PHACTR3), Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A), Tissue Factor Pathway Inhibitor (TFPI2), Hyperplastic Polyposis Protein Gene (HPP1), GATA4, Human Lactoferrin (HLTF), ATM, Ras Association Domain Family2 (RASSF2), RARB2, Hypermethylated In Cancer 1 (HIC), Engrailed gene (EN1), N-Myc Downstream-Regulated Gene family (NDRG4), IGTA4, T-cell differentiation protein (MAL), Spastic Paraplegia-20 ISPG20), Fibrillin-1 (FBN1), AGTR1, SLIT2, SEPT9 and Angiotensin II type 1 receptor gene (AGTR1).

Qualitative and quantitative methods were the two main types of methods used for methylation detection. The qualitative method included methylation-specific PCR (MSP) and methylation-specific melting curve analysis (MS-MCA). The quantitative method included Methyl-BEAMing; quantitative MSP (qMSP); MethyLight; combined bisulfite restriction analysis (COBRA); pyrosequencing; and quantitative, allele-specific, real-time target and signal amplification (QuARTS).

Colorectal carcinoma meta-analysis

The colorectal carcinoma results were pooled from 34 studies and are shown in Table 2. The meta-analysis showed that the sensitivity and specificity of the detection of colorectal carcinoma by the methylation of genes were 73% (95%CI: 71%-75%) and 92% (95%CI: 90%-93%), respectively. The positive likelihood ratio was 8.07 (95%CI: 6.26-10.41), the negative likelihood ratio was 0.31 (95%CI: 0.25-0.38), the diagnostic odds ratio was 31.49 (95%CI: 23.25-42.64), and the symmetric area under the curve was 0.9281.

Table 2.

Methylation of pooled genes for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer

| Wnt pathway | DNA damage repair pathway | Other pathways | SE (95%CI) | SP (95%CI) | DOR (95%CI) | AUC |

| Wnt pathway | DNA damage repair pathway | Other pathways | 73% (71%-75%) | 92% (90%-93%) | 31.49 (23.25-42.64) | 0.928 |

| Wnt pathway | - | - | 72% (68%-75%) | 93% (90%-96%) | 33.99 (17.99-60.50) | 0.931 |

| - | DNA damage repair pathway | - | 42% (36%-47%) | 97% (94%-99%) | 12.87 (5.98-27.72) | 0.730 |

| - | - | Other pathways | 57% (55%-59%) | 94% (93%-95%) | 20.17 (15.18-26.80) | 0.921 |

| SFRP2 | - | - | 79% (75%-82%) | 93% (90%-96%) | 47.57 (20.08-112.72) | 0.957 |

| - | MGMT | - | 47% (40%-53%) | 95% (90%-98%) | 11.67 (5.10-26.67) | 0.709 |

| - | MLH | - | 28% (18%-39%) | 100% (95%-100%) | 23.68 (3.02-185.44) | 0.500 |

| - | - | Vimentin | 49% (43%-54%) | 93% (90%-95%) | 13.81 (8.57-22.27) | 0.847 |

| - | - | OSMR | 47% (40%-54%) | 95% (91%-98%) | 14.66 (5.06-42.47) | 0.225 |

| - | - | P16 | 50% (42%-58%) | 98% (92%-100%) | 24.39 (7.26-81.96) | 0.975 |

| SFRP2 | MGMT | - | 69% (66%-72%) | 94% (91%-96%) | 33.24 (16.76-65.93) | 0.946 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | - | 72% (68%-75%) | 94% (92%-96%) | 43.03 (20.15-91.87) | 0.953 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | Vimentin | 64% (60%-67%) | 93% (92%-95%) | 24.93 (15.34-40.50) | 0.928 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | OSMR | 65% (62%-69%) | 95% (93%-96%) | 33.10 (17.12-63.98) | 0.951 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | P16 | 68% (64%-71%) | 95% (93%-97%) | 38.86 (20.11-67.54) | 0.952 |

SE: Sensitivity; SP: Specificity; DOR: Diagnostic odds ratios; AUC: The area under the curve; CI: Confidence interval; MLH: MutL Homologue; MGMT: O-6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase.

Heterogeneity was significant for the sensitivity (P < 0.001), specificity (P = 0.0008), positive likelihood ratio (P = 0.0025), negative likelihood ratio (P < 0.001), and diagnostic odds ratios (P = 0.0340).

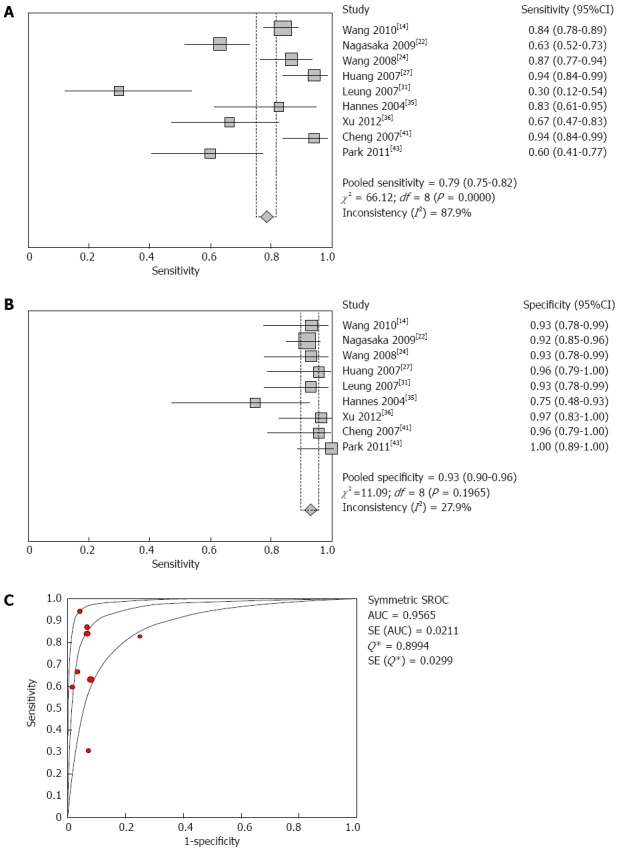

Of the involved regulation mechanisms, we found that DOR and AUC of the methylated genes belonging to the Wnt pathway were higher than those of genes of the DNA damage repair pathway and other pathways. The sensitivity, specificity, DOR and AUC of different methylated genes in the three types of pathways were calculated (Table 2), and the results indicated that the accuracy of faecal SFRP2 methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma was higher than that of other genes, with a sensitivity of 79% (95%CI: 75%-82%) (Figure 2A), a specificity of 93% (95%CI: 90%-96%) (Figure 2B), a diagnostic OR of 47.57 (95%CI: 20.08-112.72), and an area under the curve of 0.9565 (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of SFRP2 methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. A: Shows the sensitivity of SFRP2 methylation in stool samples used for colorectal carcinoma diagnosis. The point estimates of specificity from each study are shown as red squares; B: Shows the specificity of SFRP2 methylation in stool samples used for colorectal cancer diagnosis. The point estimates of specificity from each study are shown as blue squares; C: Shows the summary receiver operating characteristic curves (SROC) of SFRP2 methylation assays used for diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma. Red circles represent each study that was included in the meta-analysis. The size of each study is indicated by the size of the red circle. SROC curves summarize the overall diagnostic accuracy. Error bars indicate the 95%CI, and df indicates the degrees of freedom.

Colorectal adenoma meta-analysis

Pooled colorectal adenoma analysis (Table 3), including 26 studies, provided the following results: the sensitivity and specificity of gene methylation for colorectal adenoma diagnosis were 51% (95%CI: 47%-54%) and 92% (95%CI: 90%-93%), respectively. The positive likelihood ratio was 5.52 (95%CI: 4.23-7.19), the negative likelihood ratio was 0.52 (95%CI: 0.44-0.61), and the diagnostic odds ratio and symmetric area under the curve were 12.61 (95%CI: 8.66-18.37) and 0.8830, respectively.

Table 3.

Methylation of pooled genes for the diagnosis of colorectal adenomas

| Wnt pathway | DNA damage repair pathway | Other pathways | SE(95%CI) | SP(95%CI) | DOR(95%CI) | AUC |

| Wnt pathway | DNA damage repair pathway | Other pathways | 51% (47%-54%) | 92% (90%-93%) | 12.61 (8.66-18.37) | 0.883 |

| Wnt pathway | - | - | 40% (35%-46%) | 95% (92%-97%) | 10.81 (6.43-18.16) | 0.932 |

| - | DNA damage repair pathway | - | 21% (17%-27%) | 95% (91%-97%) | 4.23 (2.01-8.88) | 0.672 |

| - | - | Other pathways | 32% (28%-35%) | 94% (93%-95%) | 7.78 (5.48-11.05) | 0.873 |

| SFRP2 | - | - | 43% (38%-49%) | 94% (91%-97%) | 11.06 (5.77-21.18) | 0.956 |

| - | MGMT | - | 29% (22%-36%) | 93% (87%-96%) | 4.42 (2.18-8.95) | 0.614 |

| - | MLH | - | 8% (4%-16%) | 98% (92%-100%) | 2.35 (0.14-40.83) | - |

| - | - | Vimentin | 23% (17%-31%) | 95% (92%-98%) | 8.30 (2.60-26.55) | 0.898 |

| - | - | OSMR | 25% (14%-39%) | 95% (91%-98%) | 5.20 (1.44-18.82) | 0.817 |

| - | - | P16 | 33% (23%-44%) | 97% (89%-100%) | 13.27 (3.40-51.83) | 0.97 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | - | 34% (29%-39%) | 95% (92%-97%) | 9.62 (4.64-19.93) | 0.947 |

| SFRP2 | MGMT | - | 38% (33%-42%) | 94% (91%-96%) | 7.85 (4.79-12.87) | 0.753 |

| SFRP2 | - | OSMR | 41% (35%-46%) | 95% (92%-96%) | 9.25 (5.13-16.69) | 0.948 |

| SFRP2 | - | Vimentin | 36% (32%-41%) | 95% (93%-96%) | 9.88 (5.55-17.57) | 0.946 |

| SFRP2 | - | P16 | 41% (36%-46%) | 95% (92%-97%) | 10.37 (6.21-17.31) | 0.948 |

| SFRP2 | MGMT | Vimentin | 34% (30%-38%) | 94% (92%-96%) | 7.81 (4.96-12.29) | 0.804 |

| SFRP2 | MGMT | OSMR | 36% (32%-41%) | 94% (92%-96%) | 7.25 (4.61-11.39) | 0.775 |

| SFRP2 | MGMT | P16 | 37% (33%-41%) | 94% (92%-96%) | 7.92 (5.14-12.21) | 0.772 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | Vimentin | 31% (27%-35%) | 95% (93%-97%) | 8.99 (4.95-16.31) | 0.944 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | OSMR | 33% (29%-38%) | 95% (93%-97%) | 8.37 (4.50-15.59) | 0.941 |

| SFRP2 | MLH | P16 | 34% (30%-38%) | 95% (93%-97%) | 9.98 (5.45-18.27) | 0.947 |

SE: Sensitivity; SP: Specificity; DOR: Diagnostic odds ratios; AUC: The area under the curve; MLH: MutL Homologue; MGMT: O-6-Methylguanine-DNA Methyltransferase.

Heterogeneity was also clear regarding sensitivity (P < 0.001), specificity (P = 0.0233), positive likelihood ratio (P = 0.1166), negative likelihood ratio (P < 0.001), and diagnostic odds ratios (P = 0.0565).

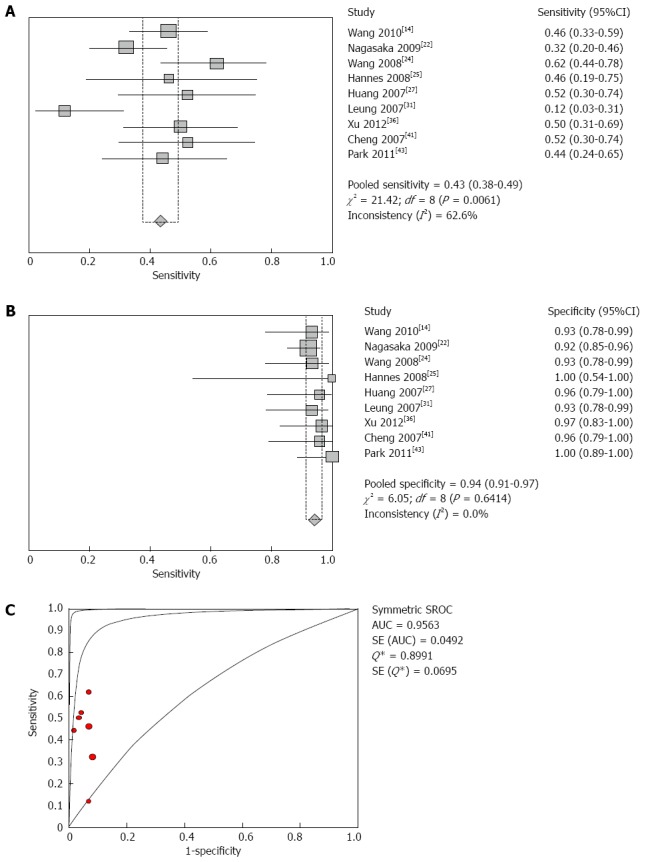

The DOR and AUC of the methylated Wnt pathway genes were higher than those of the genes of the DNA damage repair pathway and other pathways when grouping all of the genes by pathway for analysis. In these regulation mechanisms, we also found that the Wnt pathway was higher than the DNA damage repair pathway and the other pathway group. The sensitivity, specificity, DOR and AUC of the different methylated genes in the three types of pathways were calculated (Table 3), and the results indicated that the values of DOR and AUC of P16 and SFRP2 were higher than those of other genes, but the accuracy of faecal SFRP2 methylation for the diagnosis of colorectal adenoma was higher than that of P16 according to sensitivity (Figure 3A-C).

Figure 3.

Forest plot of SFRP2 methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal adenomas. A: Shows the sensitivity of SFRP2 methylation in stool samples for colorectal adenoma diagnosis; B: Shows the specificity of SFRP2 methylation in stool samples for colorectal adenoma diagnosis; C: Shows the summary receiver operating characteristic curves (SROC) of SFRP2 methylation assays for the diagnosis of colorectal adenomas.

Meta-regression

In the meta-regression analysis, the difference in relative diagnostic odds ratio values between the higher and lower quality studies was not significant. We also noted that the differences between blinded and non-blinded methods, qualitative and quantitative methods, single and multiple gene methylation did not reach statistical significance, indicating that these potential factors did not substantially affect the diagnostic accuracy, as shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Weighted meta-regression on the diagnostic accuracy of the methylation of genes assays

| Covariates | Coefficient | SE | P value | RDOR | 95%CI |

| QUADAS score1 | 0.062 | 0.413 | 0.881 | 1.06 | (0.46-2.47) |

| Detection method2 | -0.146 | 0.401 | 0.719 | 0.86 | (0.38-1.96) |

| Blinded design3 | -0.166 | 0.364 | 0.651 | 0.85 | (0.40-1.78) |

| Methylation genes4 | -0.036 | 0.444 | 0.936 | 0.96 | (0.39-2.39) |

QUADAS score, which was divided into studies with higher quality (QUADAS score ≥ 10) and those with lower quality (QUADAS score < 10);

Detection method, which was divided into qualitative and quantitative assay methods;

Blinded design: the study was included with or without blinded design;

Methylation genes, which were divided into single gene and combination genes.

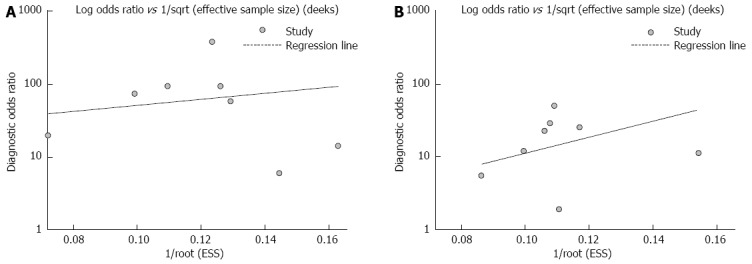

Publication bias

In our meta-analysis, publication bias was evaluated using the Egger test. The results showed no significant publication bias among the studies of SFRP2 methylation in faecal samples from CRC or adenoma patients (Figures 4A and B).

Figure 4.

Assessment of the publication bias in faecal SFPR2 methylation for the diagnosis of colorectal cancer (A) and adenomas (B). No significant publication biases were found in any of these studies (all P > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

It is widely accepted that DNA methylation in stool may be valuable for increasing the rate of CRC detection at earlier stages[47]. In the present study, we focused on the detection performance of gene methylation in stool samples for patients with colorectal tumours. Our analysis suggests that the specificity of SFRP2 methylation is high (93% for CRC and 94% for colorectal adenoma) for the detection of colorectal tumours; however, it has moderate (79%) and low sensitivity (43%) for diagnosing CRC and adenoma, respectively. Compared to FOBT, with a sensitivity of 14% for colorectal tumour diagnosis[48], the detection accuracy of faecal methylation biomarkers was higher as a CRC-screening method.

The diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) is an indicator of test accuracy. The value of the DOR ranges from 0 to infinity, and higher values indicate better discriminatory test performance. In this meta-analysis, we found that the DOR of faecal SFRP2 methylation for colorectal carcinoma and adenoma were 47.57 and 11.06, respectively, which indicated a high level of overall accuracy for CRC and a low level for adenoma. The SROC curve represents an overall measure of the discriminatory power of a test. The area under the curve of 1 for any test indicates that the test is excellent. Our data showed that the area under the curve (AUC) values of the SROC curve for faecal SFRP2 methylation for the diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma and adenoma were 0.9565 and 0.9563, respectively, which indicated that faecal SFRP2 methylation is an excellent diagnostic biomarker for colorectal tumours.

Because the DOR and SROC curve are not easy to use in clinical practice, the likelihood ratios are considered to be more clinically meaningful. For a high-quality diagnostic test, a PLR of > 10 or NLR < 0.1 is typically required. However, our meta-analysis showed that neither PLR nor NLR alone was adequate to confirm or exclude the diagnosis of colorectal carcinoma or adenoma. The PLR value was 9.12 in the diagnosis analysis of CRC, which suggested that patients with a positive faecal SFRP2 methylation assay had a nine-fold chance of being diagnosed with CRC rather than non-CRC. Therefore, a colonoscopy was necessary for patients with a positive faecal SFRP2 methylation assay to confirm the diagnosis of CRC with high probability. On the other hand, a NLR of 0.24 in the diagnosis analysis of CRC suggested that if a faecal SFRP2 methylation assay result was negative, the probability rate of the individual having CRC was 24%. For the diagnosis of colorectal adenoma, a PLR of 5.99 suggested a moderate necessity to consider colonoscopy for patients with a positive faecal SFRP2 methylation assay to confirm the diagnosis of colorectal adenoma. Moreover, the NLR was 0.60 in the diagnosis analysis of colorectal adenoma. These data suggest that a negative faecal SFRP2 methylation assay result should not be used alone as a justification for denying or discontinuing the screening of colorectal adenomas.

An aberrant Wnt signalling pathway is an early event in 90% of colorectal carcinomas. SFRPs are secreted glycoproteins that antagonise Wnt signalling by different direct or indirect mechanisms. Thus, the role of SFRPs as a negative regulator of Wnt signalling may have important significance in tumourigenesis. These epigenetic events are involved in the early steps of colon carcinogenesis, and changes in the status of DNA methylation are associated with early stages of the histologic progression of colon carcinoma. Our previous studies of CRC tissue showed that SFRP1 and SFRP2 were methylated in more than 80.6% of colorectal carcinomas[49]. Therefore, faecal SFRP2 methylation could be expected to be a biomarker for the screening of colorectal tumours. Although it cannot be generally used as a screening tool because of financial limitations, the analysis of methylation markers offers a variety of new opportunities for developing biomarkers at the molecular level of colorectal tumours.

Our meta-analysis had several limitations: (1) none of the included studies were multicentre or large-blinded, randomized, controlled trials; (2) conference abstracts and non-English and non-Chinese language studies were excluded, which might have led to publication bias; (3) studies on DNA methylation with statistical significance tend to be published and cited; and (4) due to the absence of case-mix difference analysis, smaller trials may show larger treatment effects than larger studies (e.g., patients with only localised vs metastatic disease).

To sum up, stool-based DNA methylation has been shown to be highly discriminatory in the detection of colorectal tumours. Our results demonstrate that SFRP2 methylation, as a non-invasive modality, shows promise for the accurate detection of CRC; however, a large number of studies are required to further confirm the role of faecal SFRP2 methylation for early and accurate CRC diagnosis.

COMMENTS

Background

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third-most common malignancy and the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in western countries. The diagnosis of CRC in early stages has great importance for reducing CRC mortality. Although significant advances have been achieved in diagnostic technologies, the current available modalities for diagnosing CRC remain suboptimal.

Research frontiers

DNA methylation often occurs during the early stages of colon tumours and has played an important role in oncology, especially in the early diagnosis of colorectal tumours. However, no consensus with regard to the role of stool methylation markers in colon tumours exists.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Stool methylation markers as an available non-invasive modality have high accuracy and sensitivity for the diagnosis of premalignant lesions of CRC. A few systematic reviews about the efficacy of stool methylation markers in colorectal tumour diagnosis exist. This article comprehensively assesses the accuracy of methylation genes in stool samples for diagnosing colorectal tumours.

Applications

Analysis of DNA methylation in stool samples may be used as a non-invasive test for the diagnosis of CRC, and SFRP2 methylation is a promising marker that has great potential in early CRC diagnosis.

Terminology

Diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) reflects the relationship between the result of the diagnostic test and the disease. The summary receiver operation characteristic (SROC) curve displays the trade-off between sensitivity and specificity and represents a global summary of test performance. The authors used the Q-value, the intersection point of the SROC curve with a diagonal line from the left upper corner to the right lower corner of the receiver operation characteristic (ROC) space, which corresponds to the highest value of sensitivity and specificity for the test. The positive likelihood ratio (PLR) represents the value by which the odds of the disease increase when a test is positive, whereas negative likelihood ratio (NLR) shows the value by which the odds of the disease decrease when a test is negative.

Peer review

This study reviewed 37 trials to evaluate the accuracy of stool methylation genes for diagnosing colorectal tumours. Based on these analyses, the authors conclude that stool SFRP2 methylation is a promising marker that has great potential in early CRC diagnosis. The analysis was carefully performed, and the results were clearly presented and summarized and provided valuable advice for early clinical diagnosis of colorectal tumours.

Footnotes

P- Reviewer: Dolcetti R, Konishi K, Liu T S- Editor: Qi Y L- Editor: Logan S E- Editor: Zhang DN

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schetter AJ, Harris CC. Alterations of microRNAs contribute to colon carcinogenesis. Semin Oncol. 2011;38:734–742. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitz SD, Dawson DM, Willis J, Willson JK. Focus on colon cancer. Cancer Cell. 2002;1:233–236. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(02)00053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosch LJ, Carvalho B, Fijneman RJ, Jimenez CR, Pinedo HM, van Engeland M, Meijer GA. Molecular tests for colorectal cancer screening. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2011;10:8–23. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2011.n.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Murray T, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2008. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58:71–96. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Heresbach D, Manfredi S, D’halluin PN, Bretagne JF, Branger B. Review in depth and meta-analysis of controlled trials on colorectal cancer screening by faecal occult blood test. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:427–433. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200604000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tagore KS, Levin TR, Lawson MJ. The evolution to stool DNA testing for colorectal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19:1225–1233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.02005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger BM, Ahlquist DA. Stool DNA screening for colorectal neoplasia: biological and technical basis for high detection rates. Pathology. 2012;44:80–88. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e3283502fdf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J. The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahlquist DA, Taylor WR, Mahoney DW, Zou H, Domanico M, Thibodeau SN, Boardman LA, Berger BM, Lidgard GP. The stool DNA test is more accurate than the plasma septin 9 test in detecting colorectal neoplasia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:272–7.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosch LJ, Oort FA, Neerincx M, Khalid-de Bakker CA, Terhaar sive Droste JS, Melotte V, Jonkers DM, Masclee AA, Mongera S, Grooteclaes M, et al. DNA methylation of phosphatase and actin regulator 3 detects colorectal cancer in stool and complements FIT. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:464–472. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahlquist DA, Zou H, Domanico M, Mahoney DW, Yab TC, Taylor WR, Butz ML, Thibodeau SN, Rabeneck L, Paszat LF, et al. Next-generation stool DNA test accurately detects colorectal cancer and large adenomas. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:248–56; quiz e25-6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.10.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Azuara D, Rodriguez-Moranta F, de Oca J, Soriano-Izquierdo A, Mora J, Guardiola J, Biondo S, Blanco I, Peinado MA, Moreno V, et al. Novel methylation panel for the early detection of colorectal tumors in stool DNA. Clin Colorectal Cancer. 2010;9:168–176. doi: 10.3816/CCC.2010.n.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang D, Liu J, Wang DR, Yu HF, Li YK, Zhang JQ. Diagnostic and prognostic value of the methylation status of secreted frizzled-related protein 2 in colorectal cancer. Clin Invest Med. 2011;34:E88–E95. doi: 10.25011/cim.v34i1.15105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Baek YH, Chang E, Kim YJ, Kim BK, Sohn JH, Park DI. Stool methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction assay for the detection of colorectal neoplasia in Korean patients. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52:1452–149; discussion 1452-149;. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a79533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li M, Chen WD, Papadopoulos N, Goodman SN, Bjerregaard NC, Laurberg S, Levin B, Juhl H, Arber N, Moinova H, et al. Sensitive digital quantification of DNA methylation in clinical samples. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:858–863. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Melotte V, Lentjes MH, van den Bosch SM, Hellebrekers DM, de Hoon JP, Wouters KA, Daenen KL, Partouns-Hendriks IE, Stessels F, Louwagie J, et al. N-Myc downstream-regulated gene 4 (NDRG4): a candidate tumor suppressor gene and potential biomarker for colorectal cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:916–927. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ausch C, Kim YH, Tsuchiya KD, Dzieciatkowski S, Washington MK, Paraskeva C, Radich J, Grady WM. Comparative analysis of PCR-based biomarker assay methods for colorectal polyp detection from fecal DNA. Clin Chem. 2009;55:1559–1563. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2008.122937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hellebrekers DM, Lentjes MH, van den Bosch SM, Melotte V, Wouters KA, Daenen KL, Smits KM, Akiyama Y, Yuasa Y, Sanduleanu S, et al. GATA4 and GATA5 are potential tumor suppressors and biomarkers in colorectal cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3990–3997. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayor R, Casadomé L, Azuara D, Moreno V, Clark SJ, Capellà G, Peinado MA. Long-range epigenetic silencing at 2q14.2 affects most human colorectal cancers and may have application as a non-invasive biomarker of disease. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:1534–1539. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim MS, Louwagie J, Carvalho B, Terhaar Sive Droste JS, Park HL, Chae YK, Yamashita K, Liu J, Ostrow KL, Ling S, et al. Promoter DNA methylation of oncostatin m receptor-beta as a novel diagnostic and therapeutic marker in colon cancer. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6555. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nagasaka T, Tanaka N, Cullings HM, Sun DS, Sasamoto H, Uchida T, Koi M, Nishida N, Naomoto Y, Boland CR, et al. Analysis of fecal DNA methylation to detect gastrointestinal neoplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1244–1258. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Glöckner SC, Dhir M, Yi JM, McGarvey KE, Van Neste L, Louwagie J, Chan TA, Kleeberger W, de Bruïne AP, Smits KM, et al. Methylation of TFPI2 in stool DNA: a potential novel biomarker for the detection of colorectal cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:4691–4699. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang DR, Tang D. Hypermethylated SFRP2 gene in fecal DNA is a high potential biomarker for colorectal cancer noninvasive screening. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:524–531. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oberwalder M, Zitt M, Wöntner C, Fiegl H, Goebel G, Zitt M, Köhle O, Mühlmann G, Ofner D, Margreiter R, et al. SFRP2 methylation in fecal DNA--a marker for colorectal polyps. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23:15–19. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itzkowitz S, Brand R, Jandorf L, Durkee K, Millholland J, Rabeneck L, Schroy PC, Sontag S, Johnson D, Markowitz S, et al. A simplified, noninvasive stool DNA test for colorectal cancer detection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:2862–2870. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang ZH, Li LH, Yang F, Wang JF. Detection of aberrant methylation in fecal DNA as a molecular screening tool for colorectal cancer and precancerous lesions. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:950–954. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i6.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Itzkowitz SH, Jandorf L, Brand R, Rabeneck L, Schroy PC, Sontag S, Johnson D, Skoletsky J, Durkee K, Markowitz S, et al. Improved fecal DNA test for colorectal cancer screening. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:111–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abbaszadegan MR, Tavasoli A, Velayati A, Sima HR, Vosooghinia H, Farzadnia M, Asadzedeh H, Gholamin M, Dadkhah E, Aarabi A. Stool-based DNA testing, a new noninvasive method for colorectal cancer screening, the first report from Iran. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13:1528–1533. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i10.1528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W, Bauer M, Croner RS, Pelz JO, Lodygin D, Hermeking H, Stürzl M, Hohenberger W, Matzel KE. DNA stool test for colorectal cancer: hypermethylation of the secreted frizzled-related protein-1 gene. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1618–126; discussion 1618-126;. doi: 10.1007/s10350-007-0286-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leung WK, To KF, Man EP, Chan MW, Hui AJ, Ng SS, Lau JY, Sung JJ. Detection of hypermethylated DNA or cyclooxygenase-2 messenger RNA in fecal samples of patients with colorectal cancer or polyps. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1070–1076. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petko Z, Ghiassi M, Shuber A, Gorham J, Smalley W, Washington MK, Schultenover S, Gautam S, Markowitz SD, Grady WM. Aberrantly methylated CDKN2A, MGMT, and MLH1 in colon polyps and in fecal DNA from patients with colorectal polyps. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1203–1209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lenhard K, Bommer GT, Asutay S, Schauer R, Brabletz T, Göke B, Lamerz R, Kolligs FT. Analysis of promoter methylation in stool: a novel method for the detection of colorectal cancer. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:142–149. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00624-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen WD, Han ZJ, Skoletsky J, Olson J, Sah J, Myeroff L, Platzer P, Lu S, Dawson D, Willis J, et al. Detection in fecal DNA of colon cancer-specific methylation of the nonexpressed vimentin gene. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1124–1132. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Müller HM, Oberwalder M, Fiegl H, Morandell M, Goebel G, Zitt M, Mühlthaler M, Ofner D, Margreiter R, Widschwendter M. Methylation changes in faecal DNA: a marker for colorectal cancer screening? Lancet. 2004;363:1283–1285. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xu MH, Cai KY, Tu Y. Stool DNA methylation analysis in the early diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Linchang Xiaohuabing Zazhi. 2012;24:7–19. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kang YP, Cao FA, Chang WJ, Lou Z, Wang Y, Wu LL, Fu CG, Cao GW. Stool DNA methylation in the screening early colorectal cancer. Zhonghua Weichang Waike Zazhi. 2011;14:52–561. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang JP, Wang J, Gui YL, Zhu QQ, Xu ZW, Li JS. Stool DNA methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Zhonghua Yixue Zazhi. 2011;95:2482–2484. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fu L, Sheng JQ, Meng XM, Meng MM, Jin P, Li AQ, Wu ZT, Li SR. Stool Vimentin methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Weichangbing Ji Ganzabingxue Zazhi. 2010;19:601–603. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ling ZA, Chen LS, He CG. Stool P16 methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Jiezhichang Gangmen Waike. 2009;15:144–148. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng ZH. Stool SFRP2 methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Shandong Yiyao Zazhi. 2007;47:10–12. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao HX, Li QW, Dong WW, Duan XH, Zhu JH, Wang RL, Hao YX, Ye M, Xiao WH. Stool NDRG4 methylation in the diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Zhongguo Yiyao Daobao. 2012;9:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chang E, Park DI, Kim YJ, Kim BK, Park JH, Kim HJ, Cho YK, Sohn CI, Jeon WK, Kim BI, et al. Detection of colorectal neoplasm using promoter methylation of ITGA4, SFRP2, and p16 in stool samples: a preliminary report in Korean patients. Hepatogastroenterology. 2010;57:720–727. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang H, Song YC, Dang CX. Detection of hypermethylated spastic paraplegia-20 in stool samples of patients with colorectal cancer. Int J Med Sci. 2013;10:230–234. doi: 10.7150/ijms.5278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carmona FJ, Azuara D, Berenguer-Llergo A, Fernández AF, Biondo S, de Oca J, Rodriguez-Moranta F, Salazar R, Villanueva A, Fraga MF, et al. DNA methylation biomarkers for noninvasive diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:656–665. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Guo Q, Song Y, Zhang H, Wu X, Xia P, Dang C. Detection of hypermethylated fibrillin-1 in the stool samples of colorectal cancer patients. Med Oncol. 2013;30:695. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0695-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim MS, Lee J, Sidransky D. DNA methylation markers in colorectal cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29:181–206. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9207-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Turnbull BA, Ross ME. Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2704–2714. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Qi J, Zhu YQ, Luo J, Tao WH. Hypermethylation and expression regulation of secreted frizzled-related protein genes in colorectal tumor. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:7113–7117. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v12.i44.7113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]