Abstract

Recent studies of the Cas9/sgRNA system in Drosophila melanogaster genome editing have opened new opportunities to generate site-specific mutant collections in a high-throughput manner. However, off-target effects of the system are still a major concern when analyzing mutant phenotypes. Mutations converting Cas9 to a DNA nickase have great potential for reducing off-target effects in vitro. Here, we demonstrated that injection of two plasmids encoding neighboring offset sgRNAs into transgenic Cas9D10A nickase flies efficiently produces heritable indel mutants. We then determined the effective distance between the two sgRNA targets and their orientations that affected the ability of the sgRNA pairs to generate mutations when expressed in the transgenic nickase flies. Interestingly, Cas9 nickase greatly reduces the ability to generate mutants with one sgRNA, suggesting that the application of Cas9 nickase and sgRNA pairs can almost avoid off-target effects when generating indel mutants. Finally, a defined piwi mutant allele is generated with this system through homology-directed repair. However, Cas9D10A is not as effective as Cas9 in replacing the entire coding sequence of piwi with two sgRNAs.

Keywords: CRISPR, Cas9, off-target, nickase, piwi

Recent studies of the CRISPR (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat) system have broad applications in genome editing (Deltcheva et al. 2011; Gasiunas et al. 2012; Jinek et al. 2012; Cong et al. 2013; Mali et al. 2013b). The CRISPR system provides adaptive immunity against invading viruses and plasmids in bacteria and archaea (Deveau et al. 2010; Bhaya et al. 2011; Terns and Terns 2011; Wiedenheft et al. 2012). In the type II CRISPR system, transcript from the CRISPR array is first processed into small CRISPR RNA (crRNA). Together with trans-encoded tracrRNA, crRNA then guides CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) to cleave foreign double-stranded DNA with sequence specificity provided by base-pairings between the crRNA and the target DNA. It has been shown that type II Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9, when guided by a single-guide-RNA (sgRNA), a crRNA-tracrRNA chimera, can generate DNA double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in vitro (Jinek et al. 2012; Cong et al. 2013; Mali et al. 2013b). In addition, a three-nucleotide (NGG) protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence in the DNA is required for the S. pyogenes Cas9/sgRNA system to target and cleave the double strand.

The Cas9/sgRNA system has been successfully applied in Drosophila melanogaster to generate DSBs in the genome and induce indel mutations through nonhomologous end joining (NHEJ) or sequence-specific mutations through homology-directed repairs (HDRs) for recessive viable genes (Baena-Lopez et al. 2013; Bassett et al. 2013; Gratz et al. 2013; Kondo and Ueda 2013; Ren et al. 2013; Sebo et al. 2013; Yu et al. 2013; Gratz et al. 2014; Xue et al. 2014; Yu et al. 2014). However, potential off-target DSBs might result in unexpected indel mutations, especially when relying on NHEJ, thus increasing the complexity of analyzing mutants of interest (Fu et al. 2013; Hsu et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2014). Cas9 has a RuvC nuclease domain that targets the DNA strand noncomplementary to the sgRNA and a HNH nuclease domain that targets the complementary strand (Supporting Information, Figure S1A), and mutations in either one of the two domains convert Cas9 into a DNA nickase (Jinek et al. 2014; Nishimasu et al. 2014). Previous reports showed that Cas9 nickase with a pair of offset sgRNAs that target opposite strands of DNA are capable of inducing DSBs in vitro while almost avoiding off-target DSBs (Mali et al. 2013a; Ran et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2014). In addition, coupled with one sgRNA, Cas9 nickase has been used to generate sequence-specific mutations through the HDR pathway in vitro (Cong et al. 2013; Hsu et al. 2013; Ran et al. 2013). However, less is known regarding the performance of Cas9 nickase with a pair of sgRNAs in replacing entire coding sequences of genes through HDR in vivo.

Here, we developed transgenic flies that specifically express Cas9 nickase in the germline via the nanos regulatory sequence. We then tested the indel mutation rate of Cas9 nickase with paired DNA constructs of sgRNAs and found that neighboring sgRNAs −1 to 26 bp apart that supposedly leave a 5′ overhang can efficiently generate DSBs and induce mutations. In addition, we have observed that one sgRNA does not trigger mutations in Cas9 nickase transgenic flies, suggesting that the Cas9 nickase system significantly prevents off-target effects. However, Cas9D10A is not as effective as Cas9 nuclease in replacing the entire coding sequence of essential genes such as piwi using two sgRNAs through HDR.

Materials and Methods

sgRNA and nos-Cas9D10A vector construct

sgRNAs were designed using the online CRISPR design tool (http://www.flyrnai.org/crispr/) and were cloned into the U6b-sgRNA-short vector as previously described (Ren et al. 2013). To express Cas9 nickases in Drosophila germ cells, we utilized a previously constructed nos-Cas9 plasmid (Ren et al. 2013) containing wild-type Cas9, approximately 700 base pairs of the nos promoter, the nos 5′UTR, and the nos 3′UTR. The attB donor sequence and a wild-type vermillion+ marker were also included in the nos-Cas9 plasmid. The Cas9D10A gene was generated by converting the tenth GAT codon into GCT using the AccuPrime Pfx DNA Polymerase Kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Cas9H840A gene was constructed in the same way by converting the 840th CAT codon into GCT. The sequences of the nos-Cas9D10A and nos-Cas9H840A plasmids are shown in Figure S2. The oligonucleotides used for cloning are listed in Table S1.

Donor vector construct for HDR at the piwi locus

The piwi-4XP3-mCherry donor construct was based on the pBluescript plasmid. The left homologous arm of piwi was amplified from genomic extract with primers piwi-L-F and piwi-L-R and was cloned into the AvrII and NheI sites. The right homologous arm was amplified with primers piwi-R-F and piwi-R-R and was cloned into the BamHI and SpeI sites. The selection marker 4XP3-mCherry was constructed on a different pBluescript vector first. The gene encoding the red fluorescent protein mCherry was amplified with primers mCherry-F and mCherry-R and was cloned into the XhoI and KpnI sites. The 4XP3 promoter sequence (Horn et al. 2000) was synthesized and cloned into the HindIII and XhoI sites. The SV40 3′UTR sequence was amplified with primers SV40-F and SV40-R and was cloned into the KpnI and EcoRV sites. The selection marker 4XP3-mCherry was then cut and inserted between the left and right homologous arms of piwi to finish the piwi-4XP3-mCherry construct. All PCR fragments were amplified with pfu DNA polymerase (TransGen Biotech, Beijing). The donor construct was confirmed by sequencing (Invitrogen, Beijing).

DNA purification and embryo injection

DNA plasmid solution was thoroughly mixed with 1/10 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2, AMRESCO) and 5 volumes of absolute ethanol, stored at −20° for 2 hr, and centrifuged at 21,000×g. The DNA pellet was washed twice in 70% ethanol, twice in 100% ethanol, and re-suspended in injection buffer for the appropriate concentration. The Drosophila embryos were injected using previously described protocols (Ren et al. 2013). The injection concentrations of sgRNA plasmids were at 100 ng/µL when one sgRNA was used and at 100 ng/µL each when two sgRNAs were used. The concentration of the donor template for HDR was at 400 ng/µL.

Fly stocks and mutation screening

All flies were cultured on standard cornmeal food at 25°. The P{nos-Cas9D10A}attP2 stock was previously established (Ren et al. 2013). The P{nos-Cas9D10A}attP40, P{nos-Cas9D10A}attP2, P{nos-Cas9H840A}attP40, and P{nos-Cas9H840A}attP2 fly stocks were established according to a previously described protocol (Ni et al. 2008).

To score for germline mutations, G0 adult flies that developed from injected y[1] sc[1] v[1];; P{nos-Cas9D10A}attP2 or y[1] sc[1] v[1];; P{nos-Cas9H840A}attP2 embryos were crossed to y[1] w[67c23] for white mutations. The F1 progeny were screened for the first 6 d after eclosion. The heritable mutation rate was calculated as the number of all mutant F1 progeny divided by the number of all progeny screened for a given sgRNA target. Successful piwiHDR-mCherry mutants were screened by the expression of mCherry in the eyes under a Leica MZ10F fluorescent microscope. Mutagenesis events were confirmed by sequencing of F1 adults, and the detection primers are listed in Table S1.

Genomic DNA extraction

Fly genomic DNA was purified via phenol-chloroform extraction. Single flies were homogenized in 400 μL of lysis buffer (1× PBS, 0.2% SDS, and 200 μg/mL proteinase K) and incubated at 50° for 1 hr, followed by extraction in 400 μL of phenol-chloroform. The mixture was then centrifuged at 21,000×g for 20 min at 4°, and the supernatant was then transferred to a new tube. An equal volume of isopropanol was added, and the tube was vortexed thoroughly. The mixture was then kept at −20° for at least 1 hr, followed by centrifugation at 21,000×g for 20 min at 4°. The supernatant was removed, and the DNA pellet was washed with 500 μL of 75% ethanol, followed by centrifugation at 21,000×g for 5 min at 4°. Finally, the pellet was dried for 10 min and re-suspended in 30 μL of DNase-free water.

Off-target analysis

To investigate the possibility of off-target cleavage by Cas9 nickase/sgRNA, we searched the fly genome for potential off-targets containing no more than four mismatches to the on-target, followed by a PAM sequence. Primers flanking the potential off-targets were used to PCR-amplify these regions for analysis by sequencing. For sequencing analysis, genomic DNA from a single fly was used as template, and the defined DNA fragment was amplified by specific primers (Table S2).

Immunostaining of ovaries

Ovaries were dissected in cold PBS and fixed in PBS with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, then washed with PBT (PBS and 0.3% Triton X-100) five times for 15 min each. The ovaries were incubated in 0.5% goat serum diluted in PBT for 1 hr. Appropriate primary antibodies were added to PBS and incubated at 4° overnight, then washed with PBT five times for 15 min each. Appropriate secondary antibodies were then added and incubated at 25° for 2 hr; they were washed with PBT five times for 15 min each. After the last wash, the stained ovaries were mounted in Fluoromount mounting media (F4680; Sigma). Images were obtained with an inverted Zeiss LSM780 fitted with a UV laser.

The following primary and secondary antibodies were used: mouse monoclonal anti-Hts antibody 1B1 (DSHB, 1:100); rabbit anti-Piwi (1:200; Santa Cruz sc-98264); FITC-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch); and TRITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:200; Jackson ImmunoResearch).

Results

Generating Cas9 nickase transgenic fly lines

The Cas9/sgRNA system has been introduced into Drosophila melanogaster to generate heritable mutations. However, sgRNAs may induce off-target cuttings on DNA sequences other than the intended target due to tolerated mismatches between sgRNAs and DNA. To reduce or prevent off-target effects, we deactivated either the RuvC nuclease activity of Cas9 by converting the 10th amino acid Asn (D) to Ala (A) (Figure 1A) or the HNH activity by changing the 840th residue His (H) to Ala (A) (Figure S1B). We then integrated the Cas9D10A transgene into an attP2 site on chromosome 3, or into an attP40 site on chromosome 2 (Ni et al. 2008). Cas9H840A transgenic flies were generated in the same manner. Similar to wild-type control, transgenic Cas9D10A flies and Cas9H840A flies that specifically express Cas9 nickases in the germlines are healthy and fertile.

Figure 1.

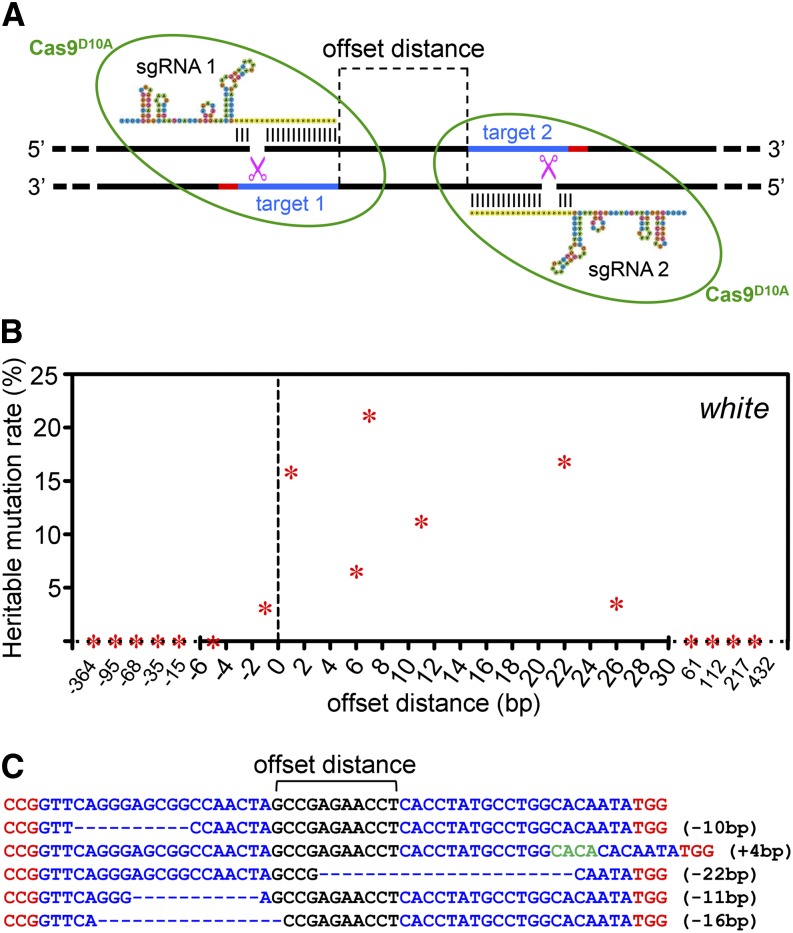

A pair of sgRNAs targeting close regions in the genome can introduce indel mutations in transgenic Cas9D10A nickase flies. (A) Diagram showing two neighboring Cas9D10A/sgRNA ribonucleoproteins targeting the fly genome. The D10A mutation converts Cas9 into a nickase that targets only the strand complementary to the sgRNA. Each Cas9D10A nickase is shown as a green circle. The sgRNA targets are shown in blue and the PAMs are shown in red. The single-strand cutting sites are shown by the magenta scissors. The offset distance is measured from the PAM-distal end of an sgRNA target to that of the other. If the PAMs are facing outward away from each other as shown in this diagram, then the distance is a positive number. (B) Scatter plot showing the relationship between heritable white mutation rate and sgRNA distance when using offset pairs in the Cas9D10A transgenic flies. Heritable mutation rate is calculated as number of the white-eyed mutant F1 flies divided by total F1 flies screened. (C) Representative sequencing results showing mutations generated with Cas9D10A transgenic flies and a pair of sgRNAs with offset distance of 11 bp. The sgRNA targets are in blue, and the PAMs are shown in red. Mutations with deleted nucleotides are shown with dashed lines, and inserted nucleotides are shown in green.

Cas9 nickase efficiently generates heritable mutants when coupled with a pair of offset sgRNAs

To examine the mutagenesis efficiency of Cas9 nickase, we constructed a series of sgRNA vectors to target the white (w) gene and introduced pairs of them into P{nos-Cas9D10A}attp2 embryos by co-injection (Figure 1B). We then crossed the injected G0s to w flies and evaluated the heritable mutation rates by screening for white-eyed F1 progeny.

Consistent with previous in vitro data from cell culture, only offset sgRNA pairs that supposedly leave a 5′ overhang after Cas9D10A cleavage can generate mutations, and such pairs with an offset range (PAM-distal end of an sgRNA to that of the other) from −1 to 26 bp had the ability to produce a mutagenesis rate up to 21.2%, with an average mutation rate of 11.2% (Figure 1B, Table 1). In addition, almost no indel mutants were generated with sgRNA offset distance outside of this range (Figure 1B, Table 1). Interestingly, sgRNA pairs complementing the same DNA single strand did not generate any mutants. Taken together, these results show that the efficiency of heritable mutation is dependent on the proper distance as well as orientations between the two sgRNA targets.

Table 1. Heritable mutation rates of sgRNAs with the wild-type Cas9 or Cas9D10A nickase.

| Gene Name (CG#) | sgRNA Offset (bp)* | sgRNA Name | sgRNA Target Sequence | Heritable Mutation Rate (%)** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Cas9 | With Cas9D10A | Both sgRNAs with Cas9D10A | ||||

| white (CG2759) | −364 | white-J | CTGCGGCGATCGAAAGGCAA | 57.1 | ND | 0 |

| white-F | CGCCGGAGGACTCCGGTTCA | 18.1 | ND | |||

| −95 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-K | GCTGCATTAACCAGGGCTTC | 64.1 | ND | |||

| −68 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-L | CCAAAAACTACGGCACGCTC | 78.6 | 0 | |||

| −35 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-F | CGCCGGAGGACTCCGGTTCA | 18.1 | ND | |||

| −15 | white-D | AGGTGAGGTTCTCGGCTAGT | 57.1 | <0.1% | 0.2 | |

| white-R | CCGAGAACCTCACCTATGCC | 58.6 | 0 | |||

| −5 | white-D | AGGTGAGGTTCTCGGCTAGT | 57.1 | <0.1% | 0 | |

| white-H | CACCTATGCCTGGCACAATA | 42.4 | ND | |||

| −1 | white-Q | GATCCTCTTGGCCCATTGCC | 52.6 | ND | 3.2 | |

| white-B | CAGGAGCTATTAATTCGCGG | 61.8 | <0.1% | |||

| 1 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 15.9 | |

| white-R | CCGAGAACCTCACCTATGCC | 58.6 | 0 | |||

| 6 | white-D | AGGTGAGGTTCTCGGCTAGT | 57.1 | <0.1% | 6.6 | |

| white-I | GGCACAATATGGACATCTTT | 52.1 | 0 | |||

| 7 | white-D | AGGTGAGGTTCTCGGCTAGT | 57.1 | <0.1% | 21.2 | |

| white-C | GCACAATATGGACATCTTTG | 43.7 | 0 | |||

| 11 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 11.3 | |

| white-H | CACCTATGCCTGGCACAATA | 42.4 | ND | |||

| 22 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 16.9 | |

| white-I | GGCACAATATGGACATCTTT | 52.1 | 0 | |||

| 26 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 3.6 | |

| white-A | CAATATGGACATCTTTGGGG | 81.6 | 0 | |||

| 61 | white-F | CGCCGGAGGACTCCGGTTCA | 18.1 | ND | 0 | |

| white-A | CAATATGGACATCTTTGGGG | 81.6 | 0 | |||

| 112 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-G | AGCGACACATACCGGCGCCC | 80.1 | <0.1% | |||

| 217 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-A | CAATATGGACATCTTTGGGG | 81.6 | 0 | |||

| 432 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-O | TTATCGGCTCCCTAACGGCC | 71.4 | ND | |||

ND, Not done.

Offset distance of a given sgRNA pair is measured from PAM-distal end of an sgRNA to that of the other. When the PAMs are facing outward relative to each other, the distance is a positive number. If the PAMs are facing inward toward each other, then the distance is a negative number.

The heritable mutation rate is calculated as the number of white-eyed F1s divided by the number of all F1s observed.

To examine the extent of the indels, we randomly sequenced mutant flies from the group of offset sgRNA pairs with distance of 11 bp. From the sequencing results of six independent F1 mutants, we found that indel mutations occurred around the targeted region (Figure 1C).

To evaluate the Cas9H840A nickase, we performed a similar mutagenesis test as described above. Unlike Cas9D10A, Cas9H840A was designed to cut only the DNA strand that was not complementary to the sgRNA (Figure S1B). Thus, sgRNA pairs with an offset distance of less than −30 bp should leave a 5′ overhang (Figure S1B). Consistent with transgenic Cas9D10A flies, only neighboring sgRNA pairs could trigger DSBs with Cas9H840A flies (Table 2). However, the mutagenesis rates of Cas9H840A flies were much lower compared with Cas9D10A flies, reaching only up to 1.5% (Table 2).

Table 2. Heritable mutation rates of sgRNAs with the wild-type Cas9 or Cas9H840A nickase.

| Gene Name (CG#) | sgRNA Offset (bp)* | sgRNA Name | sgRNA Target Sequence | Heritable Mutation Rate (%)** | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| With Cas9 | With Cas9H840A | Both sgRNAs with Cas9H840A | ||||

| white (CG2759) | −88 | white-K | GCTGCATTAACCAGGGCTTC | 64.1 | ND | 0.8 |

| white-S | GAGGACTCCGGTTCAGGGAG | 78.5 | 0 | |||

| −84 | white-F | CGCCGGAGGACTCCGGTTCA | 18.1 | 0 | 0.8 | |

| white-L | CCAAAAACTACGGCACGCTC | 78.6 | 0 | |||

| −69 | white-K | GCTGCATTAACCAGGGCTTC | 64.1 | ND | 0.8 | |

| white-P | CCTCCGGCGGACTGGGTGGC | 80.2 | 0 | |||

| −68 | white-F | CGCCGGAGGACTCCGGTTCA | 18.1 | 0 | 1.1 | |

| white-M | GCTCCGGCCACCCAGTCCGC | 63.6 | 0 | |||

| −42 | white-S | GAGGACTCCGGTTCAGGGAG | 78.5 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| white-N | CCGGCCACCCAGTCCGCCGG | 33.2 | 0 | |||

| −35 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 1.5 | |

| white-F | CGCCGGAGGACTCCGGTTCA | 18.1 | 0 | |||

| −15 | white-D | AGGTGAGGTTCTCGGCTAGT | 57.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-R | CCGAGAACCTCACCTATGCC | 58.6 | 0 | |||

| −5 | white-D | AGGTGAGGTTCTCGGCTAGT | 57.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-H | CACCTATGCCTGGCACAATA | 42.4 | ND | |||

| −1 | white-Q | GATCCTCTTGGCCCATTGCC | 52.6 | ND | 0 | |

| white-B | CAGGAGCTATTAATTCGCGG | 61.8 | 0 | |||

| 1 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-R | CCGAGAACCTCACCTATGCC | 58.6 | 0 | |||

| 7 | white-D | AGGTGAGGTTCTCGGCTAGT | 57.1 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-C | GCACAATATGGACATCTTTG | 43.7 | 0 | |||

| 11 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-H | CACCTATGCCTGGCACAATA | 42.4 | ND | |||

| 22 | white-E | TAGTTGGCCGCTCCCTGAAC | 32.3 | 0 | 0 | |

| white-I | GGCACAATATGGACATCTTT | 52.1 | 0 | |||

ND, Not done.

Offset distance of a given sgRNA pair is measured from PAM-distal end of an sgRNA to that of the other. When the PAMs are facing outward relative to each other, the distance is a positive number. If the PAMs are facing inward toward each other, then the distance is a negative number.

The heritable mutation rate is calculated as the number of white-eyed F1s divided by the number of all F1s observed.

The survival and fertile G0 rates were evaluated for the Cas9D10A and Cas9H840A methods (Table S3) and compared with those of wild-type Cas9. We also focused on the survival and fertile G0 rates of sgRNA pairs that successfully generated heritable mutants with Cas9 nickase (Figure S3). However, no significant improvements in G0 survival and fertile rates were observed when applying either version of the Cas9 nickase with paired sgRNAs compared with Cas9 nuclease and one sgRNA (Figure S3).

No off-target effects detected when using Cas9D10A flies

The major purpose of applying the Cas9D10A nickase is to reduce or prevent off-target effects associated with Cas9. Previous studies demonstrate that the numbers and positions of mismatches in nucleotides between the sgRNA and the DNA target affect the rate of off-target cuts, and as many as five mismatches could be tolerated for Cas9 to introduce DSBs in vitro (Fu et al. 2013; Hsu et al. 2013; Cho et al. 2014). To test whether the Cas9D10A/sgRNA limits off-target effects, we individually introduced the sgRNAs targeting w into P{nos-Cas9D10A}attp2 or P{nos-Cas9}attp2 embryos by microinjection. We then evaluated the heritable mutation rates as described above and found that single sgRNA never generated heritable mutants in Cas9D10A transgenic flies at a rate of more than 0.1%, despite the fact that they efficiently produced mutations with an average rate of 53.1% in wild-type Cas9 nuclease flies (Table 1). To test the H840A mutation that deactivates the HNH domain, we also injected sgRNA plasmids into P{nos-Cas9H840A}attp2 embryos. As expected, we did not find mutation with Cas9H840A flies using one sgRNA (Table 2).

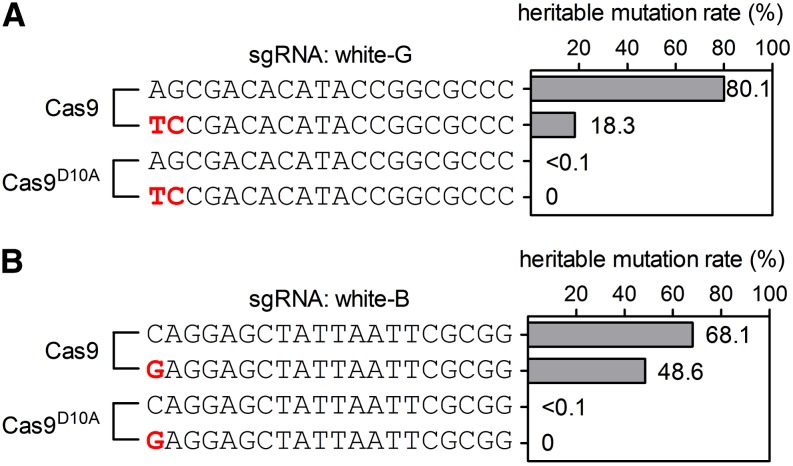

We also tested the mutagenesis efficiency of sgRNAs with mismatches to the intended targets. We first showed that two sgRNAs generated heritable mutants at rates of 80.1% and 68.1% with the Cas9 nuclease, respectively, but almost did not generate DSBs with the Cas9 nickase (Figure 2). We then constructed two sgRNAs with one or two mismatches to the intended target and tested their mutagenesis efficiency. The mismatched sgRNA can still generate mutants at rates of 18.3% and 48.6% with the Cas9 nuclease, but not with the nickase. Although these results were not direct evaluations of off-target mutations, they suggested that one or two mismatch off-target cuts were likely to happen with wild-type Cas9, but not with Cas9 nickase.

Figure 2.

Mismatched sgRNA generates heritable mutants with Cas9 nuclease, but not with Cas9D10A nickase. (A and B) Mutagenesis efficiency of sgRNAs and sgRNAs with mismatches (red). The mutagenesis efficiency of sgRNAs is tested in Cas9 or Cas9D10A transgenic flies. Each row in (A) and (B) represents an sgRNA sequence and its mutagenesis rate. (A) Mutagenesis efficiency of white-G and a white-G derivative with two mismatches. (B) Mutagenesis efficiency of white-B and a white-B derivative with one mismatch. Very low mutagenesis efficiency (<0.1%) is detected with white-G and white-B when introduced into Cas9D10A. Mismatched sgRNAs can introduce mutations when expressed in Cas9 flies, but not with Cas9D10A nickase flies.

We further examined five potential off-target sites (Figure S4) from three groups of F1 white-eyed mutants that generated from Cas9 nickase and pairs of sgRNAs. With eight genomes sequenced at each site, we did not detect any mutations induced by mismatched targeting of fewer than four nucleotides. Taken together, our in vivo experiments demonstrate that the application of Cas9 nickase almost avoids DSBs when guided by one sgRNA, and thus can remarkably limit off-target mutations.

Generate piwi null mutant through homology-directed repair

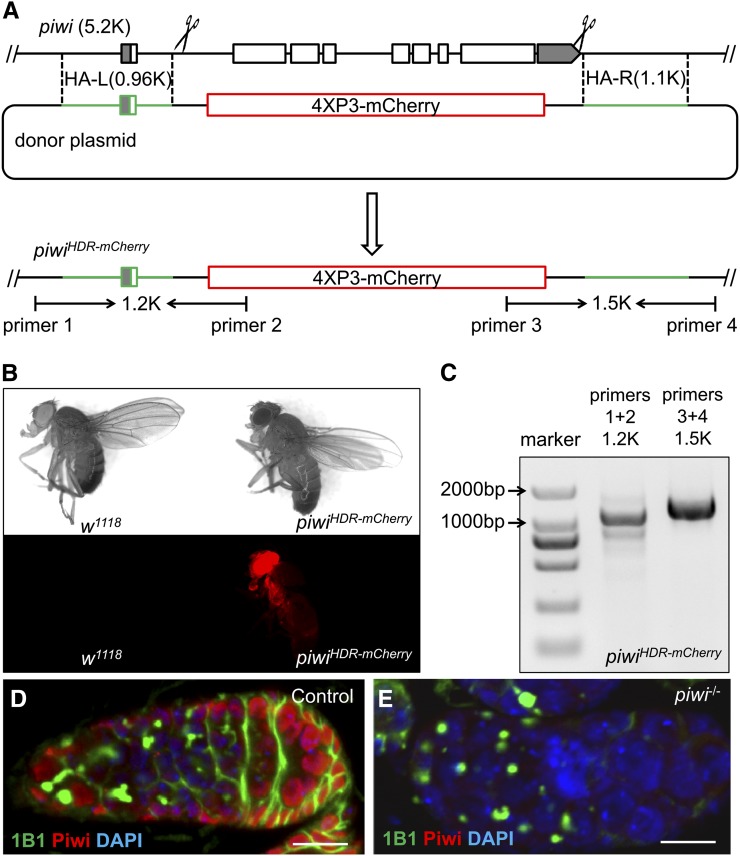

Because Cas9D10A can efficiently generate indel mutants through the NHEJ pathway, we then evaluated the efficiency of Cas9D10A in HDR. Wild-type Cas9 nuclease had been successfully applied in generating mutants through HDR (Baena-Lopez et al. 2013; Gratz et al. 2014; Yu et al. 2014; Xue et al. 2014). Ideally, complete loss-of-function mutants need to dispose of entire coding sequences. To precisely replace the entire coding sequence, the approach we developed involved the transgenic Cas9 flies, two sgRNAs, and a plasmid DNA donor with a selective marker (Materials and Methods; Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Mutagenesis through Cas9/sgRNA-induced HDR. (A) Diagrams showing the genomic region around the piwi locus, the donor plasmid as the repair template, and the mutation after HDR. The piwi donor piwi-4XP3-mCherry contains a 4XP3-mCherry sequence (red box) to replace most of the coding sequence of piwi. The two homologous arms (HA-L and HA-R; green) of the donor template are 0.96k bp and 1.1k bp, respectively. The piwi coding sequences are denoted by the white boxes, and the 5′ and 3′ UTRs are denoted by the shaded boxes. The Cas9/sgRNA cutting sites are denoted by the scissors. Successful replacement can be detected by mCherry expression in the fly eyes, or by PCR using the primer pairs shown as the arrows. (B) Images of w1118 control and piwiHDR-mCherry mutant flies under bright-field (top) or epifluorescent light sources (bottom). (C) Agarose gel electrophoresis result confirming successful piwi HDR mutation by PCR using primers shown in (A). (D and E) Confocal images of germaria from w1118 control (D) and piwiHDR-mCherry homozygous (piwi−/−; E) flies, stained with anti-Piwi (red), 1B1 (anti-Hts; green), and DAPI (blue). 1B1 shows the expression of Hu-li tai shao (Hts), a spectrosome/fusome protein. Note the morphology of the germarium is disrupted by extra GSC-like cells with round spectrosomes (E). Scale bars, 10 μm. Anterior, left.

We chose piwi for this test because known piwi loss-of-function mutants are homozygous viable but sterile, allowing for evaluation of the HDR efficiency of germline-essential genes. piwi, first discovered in Drosophila, is a key regulator of the expression of a group of small RNAs called piwi-associated RNAs (piRNAs) (Lin and Spradling 1997; Aravin et al. 2006; Girard et al. 2006; Grivna et al. 2006; Lau et al. 2006). Additionally, piwi is required both nonautonomously for the proper production of female germ line cells and autonomously in the germline stem cells (GSCs) before adulthood (Cox et al. 1998; Szakmary et al. 2005; Aravin et al. 2006; Megosh et al. 2006; Malone et al. 2009; Jin et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2014), but less is known regarding its roles in the GSCs during adulthood. Furthermore, existing piwi mutant alleles are P-element insertions or imprecise excisions of these inserts.

Through co-injection of two sgRNA plasmids targeting piwi and a DNA donor template with homologous arms to piwi, we evaluated HDR mutation rates on the piwi locus using embryos from P{nos-Cas9}attp2 and P{nos-Cas9D10A}attp2 flies, respectively. Successful HDR mutants were screened in the F1 generation for 4XP3 promoter-driven mCherry expression in the eyes (Figure 3B) and confirmed by PCR (Figure 3C). Wild-type Cas9 nuclease-generated heritable mutants occurred at a rate of 30.5% (111/364), whereas Cas9D10A nickase yielded mutations at a very low rate (<0.3%) (Table 3).

Table 3. Results of mutagenesis through HDR.

| Method | Embryos | G0 Adult | HDR Rate, % (n) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Survival Rate, %* | Fertile | Fertile Rate, %** | HDR-Yielding G0/Fertile G0 | HDR-Positive G1/Total G1 | ||

| Cas9 | 50 | 7 | 14 | 3 | 42.9 | 66.7 (2/3) | 30.5 (111/364) |

| Cas9D10A | 54 | 8 | 14.8 | 8 | 100 | 12.5 (1/8) | 0.29 (3/1021) |

The survival rate is calculated as the percentage of total G0 adults divided by embryos injected.

The fertile rate is calculated as the percentage of fertile G0 flies divided by total G0 adults.

We collected six successful F1 piwi HDR mutants with mCherry expression in the eyes and sequenced the break points. Three lines were generated with wild-type Cas9 and three were with Cas9D10A nickase (from the same G0). All six lines had the same sequencing results at both break points (Figure S5). We then sequenced potential off-target sites of both sgRNAs in the genome (Figure S6) and found no off-target mutation in any of the six mutant lines. All six lines were homozygous viable but sterile. These mutant lines were collectively named piwiHDR-mCherry, and one line generated with Cas9D10A nickase was used for the subsequent imaging experiments. Immunostaining with an antibody specifically against Piwi showed no expression of piwi in piwiHDR-mCherry homozygous (piwi−/−) fly ovaries, further supporting that piwiHDR-mCherry was a protein null allele (Figure 3, D and E). A previously reported germline tumor phenotype (Jin et al. 2013; Ma et al. 2014) was also observed in piwi−/− ovaries (Figure 3E).

Discussion

Consistent with previous in vitro data, Cas9 nickase can efficiently generate indel mutations in vivo in D. melanogaster with a pair of sgRNAs. While this manuscript was under review, an article showing one example of using the Cas9D10A nickase and one pair of sgRNAs to generate indel mutants in yellow was published (Port et al. 2014). We determined that the distance between the two sgRNA targets and their orientations are the keys to successful generation of indel mutants using the Cas9 nickase. Cas9D10A is more efficient than Cas9H840A. The reason for this difference in performance is unclear, but recent studies of the crystal structure of Cas9 suggest that it might be related to the positioning of the incoming DNA with the Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein (Jinek et al. 2014; Nishimasu et al. 2014). In all five kinds of indel mutations generated by Cas9D10A coupled with the two 11-bp-apart sgRNAs, we noticed that at least one of the sgRNA targets remains intact, which supports the notion that DSBs triggered by two sgRNAs might have occurred multiple times until one of the two targeted DNA sequences is mutated and thus is no longer recognized by the sgRNA (Cho et al. 2014).

Our results show that only paired sgRNAs that are close enough can generate indel mutations with Cas9 nickase. The numbers of hydrogen bonds of the base pairs located between the two nicks generated by the system might be important in determining whether DSBs happen. The epigenetic status of the genomic locus may also play a role as far-separated sgRNAs can generate mutations with Cas9 nickase in cell cultures (Cho et al. 2014). The orientation of the sgRNAs determines the binding orientation of Cas9 on the target DNA. Thus, the fact that only sgRNA pairs that supposedly leave a 5′ overhang can generate DSBs may reflect a physical encumbrance between the two nickases in a certain orientation when they are close on the target DNA (Nishimasu et al. 2014).

There are very low levels (<0.1%) of mutation when one sgRNA is introduced into Cas9D10A flies. The exact mechanism of these mutations is not known, but random events such as nearby additional nicking by the base excision repair pathway might trigger DSBs. In addition, very low rates of mutation induced by DNA nicks have been reported (McConnell et al. 2009; Van Nierop et al. 2009; Certo et al. 2011; Chan et al. 2011; Davis and Maizels 2011; Metzger et al. 2011; Kim et al. 2012; Ramirez et al. 2012; Gabsalilow et al. 2013; Xu and Gupta 2013; Katz et al. 2014). In practice, the <0.1% mutation rate by Cas9 nickase along with one sgRNA can be ignored when inducing DSBs. In addition, we did not detect any mutations when sgRNAs carrying one or two mismatches to the DNA target were introduced into Cas9D10A flies (Figure 2). These results demonstrate that the use of transgenic Cas9 nickase flies can largely avoid off-target DSBs.

Previous studies show that Cas9 nuclease is efficient in triggering HDR at a specific genomic site in vitro (Cong et al. 2013; Hsu et al. 2013; Ran et al. 2013). However, screening for null mutants is laborious and expensive. Here, we demonstrate that the donor vector carrying a selectable marker makes the procedure faster and cheaper. In contrast to wild-type Cas9 nuclease, Cas9D10A nickase is not as effective in our experimental settings in generating piwi null mutants. One possibility is that our donor vector introduces large replacement DNA sequence into the fly genome (4.8k bp of genomic sequence with 1.9k bp of repair template) and, thus, single-strand DNA breaks may not allow the whole replacement sequence to be used as a repair template through HDR. We also cannot exclude the possibility that a NHEJ-mediated defined deletion event happens initially with the Cas9 nuclease and the two sgRNAs before HDR. This would bring the genomic regions corresponding to the two homologous arms of the donor closer for the following HDR event, which is unlikely to take place with Cas9 nickase, based on our data (Figure 1B). Finally, the orientations of the DNA nicks might affect the efficiency of HDR. Our results demonstrate that certain strategies using Cas9 nuclease in HDR may not be suitable for Cas9 nickase, but do not rule out the possibility of using Cas9 nickase in knocking-in small DNA fragments into the fly genome at a specific site through HDR.

The application of Cas9 nickase almost avoids off-target effects, and Cas9 nickases with paired offset sgRNAs can generate heritable mutants in D. melanogaster. These results show the advantages of applying transgenic Cas9 nickase flies, especially when off-target effects are particularly concerned. However, the mutagenesis efficiency of an sgRNA pair with the Cas9 nickase is at least two-fold lower compared with either one of the sgRNA pair using the wild-type Cas9 (Table 1). Finding and constructing a pair of sgRNAs require additional effort and time. In summary, pros and cons of the Cas9 nickase system should be weighed before deciding whether to apply the nickase or to rely on the wild-type Cas9 nuclease.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Norbert Perrimon, professor at Harvard Medical School, and Dr. Babak Javid, professor at Tsinghua University, for critical comments regarding the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (20131351195 and 31301008), the Specialized Research Fund for the Doctoral Program of Higher Education of China (20121018577, 20120002110056, and 20120141120046), Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2013CFB031), the National Basic Research Program (973 Program) (2013CB835100), the Tsinghua-Peking Center for Life Sciences, and HBUT Starting Grant (BSQD12142). We declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: H. D. Lipshitz

Literature Cited

- Aravin A., Gaidatzis D., Pfeffer S., Lagos-Quintana M., Landgraf P., et al. , 2006. A novel class of small RNAs bind to MILI protein in mouse testes. Nature 442: 203–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baena-Lopez L. A., Alexandre C., Mitchell A., Pasakarnis L., Vincent J. P., 2013. Accelerated homologous recombination and subsequent genome modification in Drosophila. Development 140: 4818–4825 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassett A. R., Tibbit C., Ponting C. P., Liu J. L., 2013. Highly efficient targeted mutagenesis of Drosophila with the CRISPR/Cas9 system. Cell Reports 4: 220–228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhaya D., Davison M., Barrangou R., 2011. CRISPR-Cas systems in bacteria and archaea: versatile small RNAs for adaptive defense and regulation. Annu. Rev. Genet. 45: 273–297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Certo M. T., Ryu B. Y., Annis J. E., Garibov M., Jarjour J., et al. , 2011. Tracking genome engineering outcome at individual DNA breakpoints. Nat. Methods 8: 671–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. H., Stoddard B. L., Xu S. Y., 2011. Natural and engineered nicking endonucleases–from cleavage mechanism to engineering of strand-specificity. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: 1–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S. W., Kim S., Kim Y., Kweon J., Kim H. S., et al. , 2014. Analysis of off-target effects of CRISPR/Cas-derived RNA-guided endonucleases and nickases. Genome Res. 24: 132–141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., et al. , 2013. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339: 819–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox D. N., Chao A., Baker J., Chang L., Qiao D., et al. , 1998. A novel class of evolutionarily conserved genes defined by piwi are essential for stem cell self-renewal. Genes Dev. 12: 3715–3727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L., Maizels N., 2011. DNA nicks promote efficient and safe targeted gene correction. PLoS ONE 6: e23981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deltcheva E., Chylinski K., Sharma C. M., Gonzales K., Chao Y., et al. , 2011. CRISPR RNA maturation by trans-encoded small RNA and host factor RNase III. Nature 471: 602–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deveau H., Garneau J. E., Moineau S., 2010. CRISPR/Cas system and its role in phage-bacteria interactions. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 64: 475–493 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y., Foden J. A., Khayter C., Maeder M. L., Reyon D., et al. , 2013. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 822–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabsalilow L., Schierling B., Friedhoff P., Pingoud A., Wende W., 2013. Site- and strand-specific nicking of DNA by fusion proteins derived from MutH and I-SceI or TALE repeats. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: e83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasiunas G., Barrangou R., Horvath P., Siksnys V., 2012. Cas9-crRNA ribonucleoprotein complex mediates specific DNA cleavage for adaptive immunity in bacteria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109: E2579–E2586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girard A., Sachidanandam R., Hannon G. J., Carmell M. A., 2006. A germline-specific class of small RNAs binds mammalian Piwi proteins. Nature 442: 199–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz S. J., Cummings A. M., Nguyen J. N., Hamm D. C., Donohue L. K., et al. , 2013. Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics 194: 1029–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gratz S. J., Ukken F. P., Rubinstein C. D., Thiede G., Donohue L. K., et al. , 2014. Highly specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9-catalyzed homology-directed repair in Drosophila. Genetics 196: 961–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grivna S. T., Beyret E., Wang Z., Lin H., 2006. A novel class of small RNAs in mouse spermatogenic cells. Genes Dev. 20: 1709–1714 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn C., Jaunich B., Wimmer E. A., 2000. Highly sensitive, fluorescent transformation marker for Drosophila transgenesis. Dev. Genes Evol. 210: 623–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu P. D., Scott D. A., Weinstein J. A., Ran F. A., Konermann S., et al. , 2013. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 827–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin Z., Flynt A. S., Lai E. C., 2013. Drosophila piwi mutants exhibit germline stem cell tumors that are sustained by elevated Dpp signaling. Curr. Biol. 23: 1442–1448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Jiang F., Taylor D. W., Sternberg S. H., Kaya E., et al. , 2014. Structures of Cas9 endonucleases reveal RNA-mediated conformational activation. Science 343: 1247997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinek M., Chylinski K., Fonfara I., Hauer M., Doudna J. A., et al. , 2012. A programmable dual-RNA-guided DNA endonuclease in adaptive bacterial immunity. Science 337: 816–821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz S. S., Gimble F. S., Storici F., 2014. To nick or not to nick: Comparison of I-SceI single- and double-strand break-induced recombination in yeast and human cells. PLoS ONE 9: e88840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E., Kim S., Kim D. H., Choi B. S., Choi I. Y., et al. , 2012. Precision genome engineering with programmable DNA-nicking enzymes. Genome Res. 22: 1327–1333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo S., Ueda R., 2013. Highly improved gene targeting by germline-specific cas9 expression in Drosophila. Genetics 195: 715–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau N. C., Seto A. G., Kim J., Kuramochi-Miyagawa S., Nakano T., et al. , 2006. Characterization of the piRNA complex from rat testes. Science 313: 363–367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H., Spradling A. C., 1997. A novel group of pumilio mutations affects the asymmetric division of germline stem cells in the Drosophila ovary. Development 124: 2463–2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X., Wang S., Do T., Song X., Inaba M., et al. , 2014. Piwi is required in multiple cell types to control germline stem cell lineage development in the Drosophila ovary. PLoS ONE 9: e90267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P., Aach J., Stranges P. B., Esvelt K. M., Moosburner M., et al. , 2013a CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat. Biotechnol. 31: 833–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mali P., Yang L., Esvelt K. M., Aach J., Guell M., et al. , 2013b RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science 339: 823–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone C. D., Brennecke J., Dus M., Stark A., McCombie W. R., et al. , 2009. Specialized piRNA pathways act in germline and somatic tissues of the Drosophila ovary. Cell 137: 522–535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell S. A., Takeuchi R., Pellenz S., Davis L., Maizels N., et al. , 2009. Generation of a nicking enzyme that stimulates site-specific gene conversion from the I-AniI LAGLIDADG homing endonuclease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 5099–5104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megosh H. B., Cox D. N., Campbell C., Lin H., 2006. The role of PIWI and the miRNA machinery in Drosophila germline determination. Curr. Biol. 16: 1884–1894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger M. J., McConnell-Smith A., Stoddard B. L., Miller A. D., 2011. Single-strand nicks induce homologous recombination with less toxicity than double-strand breaks using an AAV vector template. Nucleic Acids Res. 39: 926–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ni J. Q., Markstein M., Binari R., Pfeiffer B., Liu L. P., et al. , 2008. Vector and parameters for targeted transgenic RNA interference in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Methods 5: 49–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishimasu H., Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Konermann S., Shehata S. I., et al. , 2014. Crystal structure of Cas9 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell 156: 935–949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port F., Chen H. M., Lee T., Bullock S. L., 2014. Optimized CRISPR/Cas tools for efficient germline and somatic genome engineering in Drosophila. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111: E2967–E2976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez C. L., Certo M. T., Mussolino C., Goodwin M. J., Cradick T. J., et al. , 2012. Engineered zinc finger nickases induce homology-directed repair with reduced mutagenic effects. Nucleic Acids Res. 40: 5560–5568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ran F. A., Hsu P. D., Lin C. Y., Gootenberg J. S., Konermann S., et al. , 2013. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell 154: 1380–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren X., Sun J., Housden B. E., Hu Y., Roesel C., et al. , 2013. Optimized gene editing technology for Drosophila melanogaster using germ line-specific Cas9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110: 19012–19017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sebo Z. L., Lee H. B., Peng Y., Guo Y., 2013. A simplified and efficient germline-specific CRISPR/Cas9 system for Drosophila genomic engineering. Fly (Austin) 8: 52–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakmary A., Cox D. N., Wang Z., Lin H., 2005. Regulatory relationship among piwi, pumilio, and bag-of-marbles in Drosophila germline stem cell self-renewal and differentiation. Curr. Biol. 15: 171–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terns M. P., Terns R. M., 2011. CRISPR-based adaptive immune systems. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 14: 321–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Nierop G. P., de Vries A. A., Holkers M., Vrijsen K. R., Goncalves M. A., 2009. Stimulation of homology-directed gene targeting at an endogenous human locus by a nicking endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 37: 5725–5736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiedenheft B., Sternberg S. H., Doudna J. A., 2012. RNA-guided genetic silencing systems in bacteria and archaea. Nature 482: 331–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu S. Y., Gupta Y. K., 2013. Natural zinc ribbon HNH endonucleases and engineered zinc finger nicking endonuclease. Nucleic Acids Res. 41: 378–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Z., M. Ren, M. Wu, J. Dai, Y. S. Rong et al., 2014 Efficient gene knock-out and knock-in with transgenic Cas9 in Drosophila. G3 (Bethesda) 4: 925–929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Chen H., Liu J., Zhang H., Yan Y., et al. , 2014. Various applications of TALEN- and CRISPR/Cas9-mediated homologous recombination to modify the Drosophila genome. Biol. Open 3: 271–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z., Ren M., Wang Z., Zhang B., Rong Y. S., et al. , 2013. Highly efficient genome modifications mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 in Drosophila. Genetics 195: 289–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.