Abstract

In a complex inflammatory airways disease such as asthma, abnormalities in a plethora of molecular and cellular pathways ultimately culminate in characteristic impairments in respiratory function. The ability to study disease pathophysiology in the setting of a functioning immune and respiratory system therefore makes mouse models an invaluable tool in translational research. Despite the vast understanding of inflammatory airways diseases gained from mouse models to date, concern over the validity of mouse models continues to grow. Therefore the aim of this review is two-fold; firstly, to evaluate mouse models of asthma in light of current clinical definitions, and secondly, to provide a framework by which mouse models can be continually refined so that they continue to stand at the forefront of translational science. Indeed, it is in viewing mouse models as a continual work in progress that we will be able to target our research to those patient populations in whom current therapies are insufficient.

1. From ‘bench to beside’: Do animal models still have a role to play?

Asthma is an inflammatory disease of the airways which continues to pose a substantial burden both in regards to patient morbidity and to healthcare utilization. The worldwide prevalence of self-reported asthma symptoms is 11.6% in children (1), 13.7% in adolescents (1) and 8.6% in adults (2). Recent findings suggest that 85% of asthmatics currently taking controller therapy in the United States remain uncontrolled (3) while in a study of severe asthmatics, over 15% had at least one emergency department visit in the three months preceding enrolment (4). It is for these reasons that we need to understand asthma pathogenesis better to develop more efficacious treatments.

Like all other fields of medical science, research into asthma encompasses the entire spectrum of research from in vitro cell preparations to large-scale clinical trials. Animal models stand firmly as the translational bridge between these boundaries, allowing detailed and definitive investigation of molecular pathways in a functioning immune and respiratory system. The ability to accommodate in vivo emergent phenomena such as homeostasis, positive/negative feedback and redundancy of intact animals allows thorough investigation of in vitro findings before they progress to clinical trials. However, the debate as to the validity of animal models in modern research has been reignited following findings that several mouse models of injury were unable to recapitulate the genetic responses in their respective human counterparts (5). Whilst the conclusions are not necessarily novel, these findings come at a particularly sensitive time in which governments have responded to animal rights concerns by introducing legislation limiting the use of animals in research (6). The best way to ensure relevance of animal research and promote successful translation is to continually strive to refine our models so they integrate current clinical findings of disease characteristics, pathways and specific patient phenotypes (7). In this way we will target research to those patients who are in need of alternative treatment strategies while ensuring that our models have the greatest chance of providing the transit across the translation divide.

The current Prospect aims to be a starting point in evaluating current animal models of asthma while providing a stimulus towards more refined and specific models. We feel it is therefore important to begin with a brief discussion of the clinical features of asthma before evaluating how well, or not, the currently employed models recapitulate the human disease. Although researchers have used several different animals in models of asthma (reviewed in (8, 9)) we will focus solely on the mouse as the overwhelmingly preferred model in contemporary research. The Prospect will conclude by offering a brief discussion of specific clinically relevant scenarios which we believe animal models offer great potential.

2. What are we trying to model – At the “bedside” of Patients with Asthma

Asthma is traditionally described as a chronic inflammatory disease of the airways which begins early in life. Patients with asthma often have a family history of the disease as well as allergies, rhinitis and/or eczema. The disease presents symptomatically as episodic periods of wheeze, breathlessness, chest tightness and/or cough which are most particularly present during the night and early morning. Symptoms of asthma are due to airway obstruction caused by airway narrowing and closure of small airways, which is reversible either spontaneously or following treatment in most, but not all, patients. Since the clinical presentation of asthma is due to underlying impairments in lung function, it is not surprising that the disease is clinically confirmed with measures of lung function. Airway obstruction is measured using spirometry as the volume of gas forcibly expired during 1s (FEV1) which provides a non-specific measure of the impairment in lung function. This is usually repeated following administration of bronchodilator therapy to quantify the reversibility of airway obstruction. The presence of residual obstruction has further implications, as discussed below.

In response to inhaled allergens, the initial airway obstruction in allergic asthmatics peaks within an hour and is referred to as the early asthmatic response (EAR). However, a proportion of asthmatic subjects subsequently develop a late asthmatic response (LAR) which develops and peaks from three hours to 24 hours post-exposure (10). These episodes of airway obstruction in asthma are due to another characteristic feature of asthma; the predisposition of the airways of patients with asthma to narrow excessively in response to a stimulus, termed airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR). AHR comprises both increased sensitivity to response as well as excessive bronchoconstriction, whereby there is no measurable response plateau (Figure 1A). Although the airway obstruction underlying the clinical manifestation of asthma is considered reversible, structural airway changes can lead to permanent reductions in airway caliber. These changes are collectively termed airway remodeling and may include subepithelial fibrosis, airway smooth muscle hypertrophy/hyperplasia, angiogenesis, mucous cell metaplasia and changes in extracellular matrix composition (11). It is also worth noting that although the airway inflammation characteristic of asthma has long been considered mediated by eosinophillic inflammatory cells, our understanding now includes patients with airway inflammation associated with elevated neutrophils with or without increased eosinophils (12) as well as other cells of adaptive immunity and inflammation.

Figure 1. Comparison of lung anatomy between human and mouse.

Computed tomography (CT) lung slice images from a 26 year old male (a) and a BALB/c control mouse (b, with μCT) showing the substantially greater relative airway caliber in mice. Maximum intensity projection images from a control mouse (c) and a mouse challenged with ovalbumin (d), both exposed to room air. Again note the large airway size relative to total lung size and the monopodial branching pattern, in which one daughter airway is much larger than the other. The human lung image was provided by Dr Jeffrey Klein, Department of Radiology, University of Vermont College of Medicine. Mouse lung images were provided by Dr Lennart K. Lundblad, Department of Medicine, University of Vermont College of Medicine (see Lundblad et al (64) for methodological details).

3. Evaluating the mouse in models of asthma

3.1. Acknowledging the obvious: differences in lung anatomy

Before we consider the pathophysiological features of current mouse models it is important not to overlook the obvious – the respiratory anatomy of the mouse is considerably different from that of a human (Figure 1). Firstly, mice are quadrupeds. Heterogeneous ventilation distribution within the lungs both at baseline and during bronchoconstriction appears to be an important pathophysiological feature of human asthma, and since ventilation distribution is heavily influenced by gravity, this distinction may not be trivial. The number of airway branches is worth consideration, with mice and men lying on opposite ends of the spectrum (six to eight and ~23, respectively). Moreover, the branching pattern is distinct between mice and humans. The branching pattern in humans is symmetrical and dichotomous with daughter airways subtended at 45 degrees and of equal size and diameter. In contrast, branching in mice, as in all non-primates, is monopodial, in which one daughter airway is much larger than the other. Compared to humans, mice have large airway calibers for their respective lung sizes (13) (see also Figure 1), while humans have a collateral network of small airways which is not apparent in mice. These differences in anatomy are likely to affect ventilation distribution and thus aerosol distribution, potentially confounding studies of AHR, airway obstruction, structural changes and development of novel aerosolized treatments.

3.2. Models of allergic airways disease

Animal models of allergic airways diseases have been widely used to recapitulate the pathophysiology associated with recurrent exposure to allergens seen in human asthma. Since mice, like the majority animals, do not naturally develop a periodic inflammatory airways disease reminiscent of asthma, mouse models require a protocol of sensitization to an allergen and subsequent re-exposure to elicit an allergic response. A common protocol is the ovalbumin model in which mice are injected with ovalbumin and an adjuvant, with subsequent exposure to aerosolized or intranasal ovalbumin via the airways. Adjuvants commonly used are aluminium salts and the gram negative bacterial cell wall component, lipopolyssachride (LPS). Aluminium salts enhance antibody responses and activate innate immune cells, which then lead to TH-2 cell responses (14). LPS activates toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) on airway epithelial cells (15), initiating downstream pro-inflammatory signaling. While the ovalbumin model has been largely responsible for the tremendous understanding gained from mouse models of asthma, several points of criticism have been raised questioning its physiological relevance to human asthma. Firstly, extended provocation with ovalbumin leads to tolerance in at least some strains of mice, reducing its applicability in modelling chronic asthma (16). Secondly, the route of sensitization to ovalbumin is via intraperitoneal injection, whereas an asthmatic patient may be sensitized via the airway. Lastly, ovalbumin is not amongst the myriad of allergens considered important triggers for asthma, adding further motivation for researchers to develop more relevant methods of inducing allergic airways disease.

To address concerns with the applicability of ovalbumin models, allergens that are directly relevant to human asthma, such as Aspergillus fumigatus (17), cockroach antigens (18) and ragweed extracts (19), are being employed. The most commonly employed allergen is house dust mite extract (HDM), a multifaceted allergen to which 50–85% of asthmatics are allergic (20). HDM extract contains many allergenic components, including fecal matter, LPS, chitin (a glucose derivative) and proteins, such as Dermatophagoides pteronyssinus, all of which are hypothesized to be involved in the human allergic response. Exposure to HDM induces allergic airways disease in mice via TLR4 triggering of airway structural cells, as well as production of pro-inflammatory cytokines thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interleukin 25 (IL-25) and IL-33 (21).

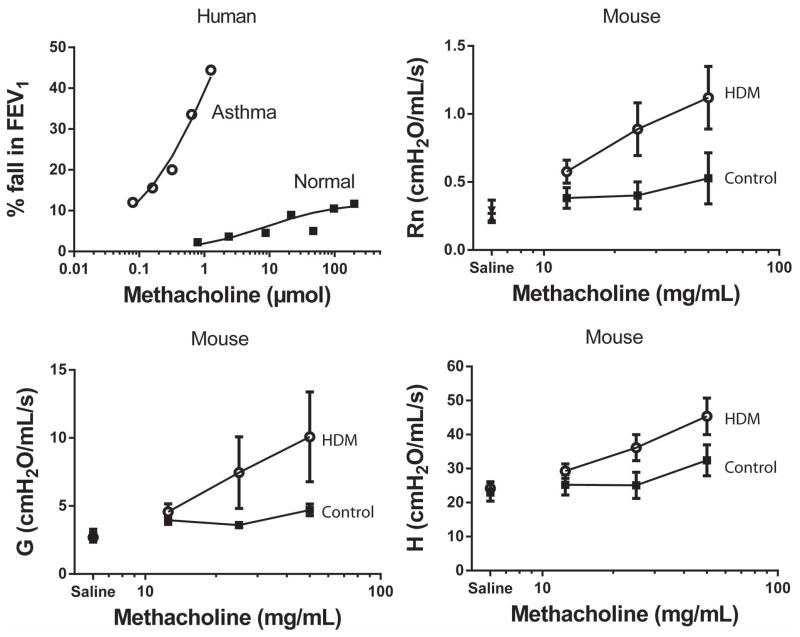

Common manifestations of the ovalbumin model include eosinophilic and lymphocytic infiltration in the lung while addition of LPS as an adjuvant to the ovalbumin model promotes increased neutrophils into the airways (22). Similarly, HDM exposure, likely due to the presence of LPS, leads to a mixed airway inflammatory phenotype consisting of both eosinophils and neutrophils (23). Airway obstruction representative of the EAR is only evident in at most 50% of mice following ovalbumin challenge while an LAR does not occur with the traditional protocol (24). However, models extending re-exposure past four challenges have reported LAR in mice (25), although there is a small window before tolerance to ovalbumin occurs. In the HDM model, an EAR is evident following three weeks of challenge but not following one week, despite elevated airway inflammation at both time points (26). To the best of our knowledge we are unaware of any studies which have investigated the LAR in HDM models of asthma. Importantly, the magnitude of airway obstruction in mice is substantially less than that which can occur during an exacerbation in asthma patients, most likely due to the relatively large airway caliber in mice. Robust and substantial AHR to non-specific bronchoprovocation is a characteristic feature of mouse models of allergic asthma, although marked variability in the severity exists between strains (27). While ovalbumin and HDM lead to varying degrees of AHR, it is worth noting that this mostly represents the increase in the maximal response plateau such as seen in moderate to severe asthmatic patients (Figure 2). However, increased sensitivity can be induced through disruption of airway epithelial integrity following acid aspiration (28) or the airway treatment with highly cationic proteins such as poly-L-lysine (29). Both ovalbumin (30) and HDM (31) models induce features of airway remodeling, such as airway smooth muscle hypertrophy/hyperplasia, subepithelial fibrosis, mucous goblet cell hyperplasia and increased fibronectin.

Figure 2. Airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) to methacholine in human subjects and in mice.

The response to increasing doses of methacholine in an asthmatic patient (

, 20 year old male, baseline FEV1 of 97% predicted) and a healthy, non-asthmatic subject (■, 27 year old male, baseline FEV1 of 92% predicted). Note that the asthmatic patient has a provocative dose causing a 20% fall in forced expiratory volume in one second (PD20FEV1) of 0.3μmol of methacholine whereas the non-asthmatic subject does not reach a 20% fall even at a dose > 500-fold higher. The response to methacholine in mice following either 15 instillations of control (PBS, ■) or house dust mite (HDM,

, 20 year old male, baseline FEV1 of 97% predicted) and a healthy, non-asthmatic subject (■, 27 year old male, baseline FEV1 of 92% predicted). Note that the asthmatic patient has a provocative dose causing a 20% fall in forced expiratory volume in one second (PD20FEV1) of 0.3μmol of methacholine whereas the non-asthmatic subject does not reach a 20% fall even at a dose > 500-fold higher. The response to methacholine in mice following either 15 instillations of control (PBS, ■) or house dust mite (HDM,

) measured as central airway narrowing (Rn), peripheral tissue resistance (G) and tissue elastance (H). In contrast to ovalbumin models, house dust mite challenge results in greater central airway (Rn) effects whereas AHR following ovalbumin challenge is predominantly characterized by airway closure (H).

) measured as central airway narrowing (Rn), peripheral tissue resistance (G) and tissue elastance (H). In contrast to ovalbumin models, house dust mite challenge results in greater central airway (Rn) effects whereas AHR following ovalbumin challenge is predominantly characterized by airway closure (H).

Although there is great appreciation that sensitization and subsequent development of allergic airways disease in the mouse is a complex process involving a variety of cell types and recruitment time courses, there have been few studies of the time course of development of pathophysiology. In the ovalbumin model, eosinophilic airway inflammation resolves within days of the final challenge while AHR and remodeling persist up to eight weeks (32). We have recently reported a comprehensive investigation into the time course of response to HDM from an hour after single challenge up to 15 instillations (23). Airway neutrophilia occurred following three daily HDM exposures which persisted between 6 and 24 hours following exposure; however, following five daily exposures, neutrophils no longer predominated in the bronchoalveolar fluid (BALF), which was instead characterized by marked increases in airway eosinophils. Interestingly, both eosinophils and neutrophils were increased following 15 challenges. Additionally, AHR was only evident following 10 and 15 challenges, whereas features of airway remodeling, such as mucus metaplasia, collagen deposition and ASM hypertrophy/hyperplasia, required 15 HDM challenges. These data suggest remodeling and AHR may not be directly linked pathologies while raising further questions as to the time-course and role of airway inflammation. This dissociation between AHR and other pathophysiological features of asthma has also been highlighted in human asthma (33).

3.3. Antigen-independent models of allergic asthma

There are several mouse models of asthma that result in an allergic airways disease without the requirement of sensitization and re-exposure to an antigen. These include intratracheal instillation with cationic proteins, such as poly-l-lysine, ozone and chlorine. These models most likely represent damage to the airway epithelium with subsequent consequences for downstream pro-inflammatory signaling. Cationic protein and chlorine exposure may also reduce the barrier role of the epithelium thus rendering underlying structures such as the airway smooth muscle more accessible. Acute exposure to these injurious molecules results in airway neutrophilia, AHR and increased collagen deposition (Figure 3). Interestingly, AHR following cationic protein instillation is associated with increased sensitivity but no change in the maximum response (34), whereas ozone and chlorine lead to AHR associated only with an increased maximal response as seen in antigen-induced AHR. Higher doses of chlorine also appear to induce increased sensitivity to methacholine as measured by changes in tissue stiffness (35).

Figure 3. Representation of the different types of airway hyperresponsiveness (AHR) induced by antigen-dependent and several antigen-independent models of allergic airways disease.

Antigen-dependent models, such as ovalbumin sensitization and re-exposure, predominantly induce an increase in the maximal response plateau. Similarly, ozone and chlorine exposure lead to an increase in the maximal response plateau; however, high doses of chlorine appear to also replicate the increased sensitivity (leftward shift) that is characteristic of AHR in patients with asthma. In contrast, cationic proteins cause an increase in sensitivity to bronchoconstricting stimulus without altering the maximal response plateau.

4. Moving past blanket models – phenotypic approaches to animal models of asthma

An emerging concept is that the clinical presentation of asthma is the culmination of widely heterogeneous underlying disease pathology. As the preceding discussion illustrated, heterogeneous mechanisms characterize animal models as well. With personalized medicine the end goal, researchers have turned to cluster analyses in an attempt to characterize specific patient phenotypes based upon various clinical, inflammatory and physiological characteristics. The two main cluster analyses of patients with asthma report surprisingly similar phenotypic groups (36, 37). Both studies report a group of atopic asthmatics with severe lung function impairment and elevated eosinophillic airway inflammation despite optimal treatment. Similarly, both report an obese female population with non-atopic disease and a subgroup of severe asthmatics associated with late-onset disease. Furthermore, there appears to be a group without eosinophillic airway inflammation, with suggestions of patients both with elevated neutrophillic inflammation and without airway inflammation. Understanding the mechanisms underlying each phenotypic group remains the ultimate path towards personalized medicine and provides important avenues for development and study of phenotypic mouse models of asthma, as discussed below (Table 2).

4.1. Age-associated models of asthma

The majority of mouse models utilize animals within a very tight age range which could be considered representative of adolescence. Although this is in part due to cost restraints of housing mice for months, our understanding of the effect of age in the manifestation and progression of asthma is therefore limited. Mice 3–6 months of age reflect early adulthood whereas 10–15 month old mice are representative of middle age (38). Models utilizing both are likely to contribute to our understanding of adult-onset asthma and whether there are distinct consequences for treatment in this patient phenotype (39). Furthermore, immune senescence in the mouse occurs after 18 months of age and therefore this age range could provide much needed understanding applicable to asthma in the elderly. Initial data suggests that mice sensitized to ovalbumin at six months or older show reduced severity of AHR, increased eosinophilic airway inflammation and increased mucus metaplasia (40). The clinical relevance of these findings warrants further investigation.

4.2. Models of obese asthma

Mouse models have contributed greatly to our understanding of the effect of obesity on respiratory health. This is in part attributable to the number of different models available. Diet-induced obesity in mice is induced through the use of a high fat diet consisting of 60% fat (compared to standard chow of 10% fat). There are two models in which genetic modification of the activity of leptin, a satiety hormone, leads to excessive weight gain; genetic deletion of leptin itself (ob/ob) or the leptin receptor (db/db). Similarly, excessive weight gain is induced in mice genetically deficient in an enzyme involved in eating behaviors, carboxypeptidase E (Cpefat). There is much variation in the speed and extent to which each model develops obesity, with ob/ob and db/db excessive obese by eight weeks of age whereas weight gain in diet-induced and Cpefat is comparatively delayed (41). Interestingly, although all obese mouse models are innately hyperresponsive (ie without sensitization) the development of AHR appears to correspond to the time-course of weight gain (41). This innate AHR is not associated with airway inflammation but rather appears dependent upon the production of IL-17A by innate lymphoid cells in the lung (42). This should prove to be a promising area of future research (43).

4.3. Models of severe asthma

There is a clear lack of mouse models of severe asthma which are needed to better understand this important patient population. A recent model of co-expression of both systemic interleukin-5 and lung eotaxin-2 (I5/E2) replicates many features of severe asthma (44). Unlike other mouse models, I5/E2 double transgenic mice also replicate the eosinophil degranulation seen in human patients. Non-challenged I5/E2 mice had exaggerated airway remodeling compared to WT mice challenged with ovalbumin and such severe AHR that methacholine challenges frequently led to death.

The expression of IL-17 from CD4+ memory T cells, referred to as TH-17 cells, appears to play an important role in neutrophillic airway inflammation and AHR that is steroid resistant in mouse models of asthma (45). Additionally, a recent model utilizing sensitization with a combination of ovalbumin, HDM and cockroach appears to result in increased AHR and asthma pathophysiology that was steroid resistant (46). It is evident from the above that these two models represent different yet equally informative pictures of severe disease – the former exaggerated pathophysiology and the latter two steroid-resistance – and future research is needed to determine which features of both models represent the human phenotype/s.

5. The role of animal models in translational research

5.1. Enhanced mechanistic understanding from transgenic mouse models

The overwhelming popularity of the mouse as a model of asthma is largely based upon technologies allowing for genetic manipulation not yet widely available in other animals (reviewed in (47)). Utilizing transgenic mouse models of asthma has provided in-depth understanding of the role of a plethora of cytokines, receptors and other molecules in the pathophysiology of human asthma. One example from our laboratory is the role of the pro-inflammatory signaling pathway, Nuclear Factor-kappaB (NF-κB), which was shown to be elevated in the airway epithelium of patients with asthma (48). To fully elucidate the complex role of airway epithelial NF-κB, we first utilized a transgenic model whereby a mutant of the inhibitor of NF-κB, IκBα, was constitutively overexpressed in CC10 expressing cells (CC10-NF-κBSR), thus preventing the activation of NF-κB in ciliated airway epithelial cells. Using the ovalbumin model, the CC10-NF-κBSR transgenic mouse demonstrated reduced eosinophilia, mucus metaplasia, and inflammatory cytokines; however, there was no observed difference in AHR (49). In contrast, following HDM exposure, CC10-NF-κBSR mice displayed attenuated neutrophilia, airway remodeling and AHR (23). These studies demonstrated a critical role of airway epithelial NF-κB in asthma models but also illustrate that the specific effects of NF-κB on pathophysiology are dependent upon the particular model utilized.

To further unravel the complexities of epithelial NF-κB activation in asthma models, a transgenic mouse was created in which Inhibitory kappa B kinase beta (IKKβ), a kinase crucial to activation of NF-κB, was inducibly deleted from the ciliated airway epithelium via the doxycycline/CC10-tet/op-cre system (ie an inducible knockout). Epithelial inhibition of IKKβ, and thus NF-κB, during the sensitization phase of the ovalbumin model resulted in marked decreases in structural remodeling, mucus metaplasia, eosinophilia and AHR (50). Additional studies utilized mice in which a phosphomimetic mutant of IKKβ (CA-IKKβ) was conditionally expressed under the CC10 promoter, facilitating increased activation of NF-κB in the epithelium. Following sensitization to ovalbumin, activation of NF-κB in the epithelium during subsequent re-exposure resulted in enhanced AHR, neutrophilia, eosinophilia, and airway smooth muscle hyperplasia/hypertrophy (51). Alternatively, NF-κB activation within the epithelium during the initial exposure of ovalbumin was sufficient to cause sensitization in the absence of other adjuvants (52). Together these findings, obtained through the sophisticated use of mouse transgenic models, suggest a critical role of NF-κB activation in the airway epithelium in both sensitization to antigen and response to subsequent re-exposure. This genetic paradigm will allow for further investigation and eventual unravelling of the signaling pathways activated when topical agents are inhaled and represents a rigorous approach to address mechanistic hypotheses.

5.2. Using mouse models to instruct clinical research

There are a plethora of studies in which pharmacological intervention reduces asthma pathophysiology in mouse models yet many of these fail to survive to clinical practice. One factor often overlooked is toxicity which cannot be entirely predicted by animal models except in the case of overt clinical signs. Another contributing issue is whether or not the mouse models have been appropriately interpreted to ensure that any clinical studies are targeted towards the appropriate patient populations. The case of IL-13 in asthma is one such example. IL-13 was first implicated in asthma after discovery that expression was increased in asthmatic patients (53). Subsequent studies in mice suggested a causal role of IL-13 since IL-13 neutralization in ovalbumin challenged mice decreased AHR, airway eosinophils and mucus production while administration of IL-13 to non-sensitized mice induced asthma pathophysiology (54). However, further investigation revealed that IL-13 was critical for development of AHR associated with airway inflammation but not for chronic AHR associated with airway remodeling (55), suggesting that anti-IL-13 treatment would only be efficacious in those with persistent eosinophillic airway inflammation. Indeed, these findings were recently translated into a clinical trial reporting that treatment with an IL-13 neutralizing monoclonal antibody in patients with uncontrolled asthma led to improvements in lung function only in patients with elevated FeNO, a biomarker for eosinophilic airway inflammation (56). A similar situation occurred with IL-5, in which a monoclonal antibody against IL-5 showed no benefits in general populations of asthmatics but was effective at reducing several disease outcomes in a selective phenotype of patients with eosinophilia despite oral corticosteroids (57).

6. Moving Forward

Severe disease accounts for the majority of morbidity and mortality in human asthma, and thus refinement of severe mouse models is an important direction in the development of novel and clinically relevant therapies. A recent consensus statement from the European Respiratory Society and American Thoracic Society (58) defined severe asthma as patients who remain uncontrolled on, or only reach control with, high dose inhaled corticosteroids or frequent systemic corticosteroids. Uncontrolled asthma is assessed by either poor symptom control, the requirement for “bursts” of systemic corticosteroids, exacerbations requiring hospitalization or airflow limitation not responsiveness to bronchodilator. Some of these features are difficult to recapitulate in mice but we suggest that important features of a model of severe asthma may include resistance to corticosteroids, exaggerated structural remodeling and excessive/fatal bronchoconstriction in response to either allergen or methacholine inhalation. It is likely that the pathophysiology in severe asthmatics who remain uncontrolled and those who reach control involve distinct underlying mechanisms. Therefore it is also likely that several models of severe asthma will be needed to understand this clinically important patient population.

Our understanding of asthma now includes those patients who develop the disease very early in life and those who develop the disease after adolescence. It appears that adult-onset disease is less associated with airway inflammation than early-onset asthma yet there are no recognized treatment options for this population. Understanding the mechanisms leading to the initiation of asthma pathophysiology post-development is therefore an important avenue of future research. Furthermore, elderly asthmatics have increased morbidity and mortality (16) which could be due to the effects of age (such as immune senescence and increased neutrophilia) confounding asthma pathophysiology or a synergistic mechanism resulting in distinct pathophysiology. Similarly, we do not know whether current therapies are less effective in elderly asthmatics or changes in physiology, such as reduced elastic recoil, reduce the ability for therapies to reach the site of abnormality. Animal models, if well-conceived, could shed light on this dilemma.

The aging population is also growing, and little is known about the combined effects of age and obesity. It is unknown whether a patient who becomes obese during middle age has different pathophysiology as a patient who was obese during lung development, and, maybe more importantly, whether obesity during development is a disease modifier later in life independent of weight loss. Similarly, epidemiological data suggests that maternal obesity is associated with infant wheezing and that weight gain during pregnancy increases the risk of asthma in offspring (59). Mouse models provide an exciting potential to allow investigation of the pathophysiological effect of maternal obesity and to differentiate a direct effect of obesity from effects of dietary deficiency.

The changing climate in which we live has many consequences for respiratory health which will potentially impact the development and severity of asthma. Ground ozone levels rise during extreme heat conditions and when combined with drought could substantially increase the number of days in which ozone levels exceed air quality guidelines (60). Since projections suggest such conditions will increase in frequency and intensity (61) exposure to ozone is likely to continue to rise. Acute increases in ozone are known to worsen asthma symptoms yet we do not know whether repeated spikes or sustained increases in ground ozone levels may alter the response to treatment, modify pathophysiology or contribute to the development of asthma. Furthermore, obesity may exaggerate the effects of ozone on respiratory health (62), particularly in those with AHR (63). However, the clinical relevance or underlying mechanisms of the interaction between obesity, asthma and ozone levels is yet to be determined and animal models would be useful in unraveling these relationships.

7. Conclusion

Mouse models have contributed substantially to our understanding of the underlying pathophysiology in asthma. Although no mouse model of allergic airways disease encompasses all features of the human disease, careful comparison of the clinical manifestations of human asthma reveal that current models recapitulate many characteristic inflammatory, structural and physiological pathology. However, careful considerations should be given to the type of model employed, method of measurement of lung function and timing of intervention so as to best model the clinical situation. Furthermore, we must continue to strive to refine our models in light of new clinical information so that rather than replicating “asthma”, mouse models are able to reflect specific phenotypes of asthmatic patients. In doing so, we will continue to drive the translation of not only disease understanding but the development of novel treatments in those whom current therapies are insufficient.

Table 1.

Clinical Phenotypes of human asthma and their corresponding mouse models

| Human Phenotype | Mouse model |

|---|---|

| Allergic: antigen-dependent | Ovalbumin + adjuvant (Al(OH)3 or LPS) House dust mite Aspergillus fumigatus Cockroach Ragweed |

| Allergic: antigen-independent (injury models) | Cationic protein Ozone Chlorine Hydrogen Chloride |

| Obese | Diet induced Cpefat Db/Db Ob/Ob |

| Severe eosinophilic | IL-5 + Eotaxin-2 HDM + ovalbumin + cockroach (mixed inflammatory profile) |

| Severe neutrophilic | TH-17 transfer/IL-17 HDM + ovalbumin + cockroach (mixed inflammatory profile) |

| Adult onset | > 6 months (?) |

| Elderly asthma | > 18 months (?) |

Traditional mouse models of asthma have focused on allergic airways disease and have predominantly utilized sensitization and re-exposure to a variety of antigens. However, several models are available which are independent of antigen and most likely represent consequences of injury to the airway epithelium. Cluster analyses of human patients with asthma have discovered several specific phenotypes which have begun to be recapitulated in mouse models. Obesity models are the most prevalent of the phenotypic asthma models and have contributed greatly to our understanding of the effect of obesity on asthma pathophysiology. In contrast, there are currently limited models of severe disease and their clinical relevance is yet to be determined. Although the effect of aging in mouse models of asthma has been reported, much is still to be elucidated as to the effect of differences on treatment response and disease progression. Cpefat = mice with a genetic deficiency in carboxypeptidase an enzyme involved in the regulation of eating behaviors, ob/ob = mice deficient in leptin, db/db = mice deficient in the leptin receptor, IL-5 = interleukin-5, IL-17 = interleukin-17.

Acknowledgments

DGC is a recipient of a CJ Martin Fellowship from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (# 1053790).

JET is supported by a T32 grant from the National Institutes of Health (HL076122).

JDN is supported by a T32 grant from the National Institutes of Health (ES07122).

References

- 1.Asher MI, Montefort S, Bjorksten B, Lai CK, Strachan DP, Weiland SK, Williams H. Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC Phases One and Three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):733–43. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.To T, Stanojevic S, Moores G, Gershon AS, Bateman ED, Cruz AA, Boulet LP. Global asthma prevalence in adults: findings from the cross-sectional world health survey. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:204. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Colice GL, Ostrom NK, Geller DE, Anolik R, Blaiss M, Marcus P, Schwartz J, Nathan RA. The CHOICE survey: high rates of persistent and uncontrolled asthma in the United States. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2012;108(3):157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2011.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chipps BE, Zeiger RS, Borish L, Wenzel SE, Yegin A, Hayden ML, Miller DP, Bleecker ER, Simons FE, Szefler SJ, Weiss ST, Haselkorn T. Key findings and clinical implications from The Epidemiology and Natural History of Asthma: Outcomes and Treatment Regimens (TENOR) study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(2):332–42. e10. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seok J, Warren HS, Cuenca AG, Mindrinos MN, Baker HV, Xu W, Richards DR, McDonald-Smith GP, Gao H, Hennessy L, Finnerty CC, Lopez CM, Honari S, Moore EE, Minei JP, Cuschieri J, Bankey PE, Johnson JL, Sperry J, Nathens AB, Billiar TR, West MA, Jeschke MG, Klein MB, Gamelli RL, Gibran NS, Brownstein BH, Miller-Graziano C, Calvano SE, Mason PH, Cobb JP, Rahme LG, Lowry SF, Maier RV, Moldawer LL, Herndon DN, Davis RW, Xiao W, Tompkins RG. Genomic responses in mouse models poorly mimic human inflammatory diseases. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(9):3507–12. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222878110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Animal research: a balancing act. Nat Med. 2013;19(10):1191. doi: 10.1038/nm.3382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Of men, not mice. Nat Med. 2013;19(4):379. doi: 10.1038/nm.3163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zosky GR, Sly PD. Animal models of asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(7):973–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Corry DB, Irvin CG. Promise and pitfalls in animal-based asthma research: building a better mousetrap. Immunol Res. 2006;35(3):279–94. doi: 10.1385/IR:35:3:279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Boonsawat W, Salome CM, Woolcock AJ. Effect of allergen inhalation on the maximal response plateau of the dose-response curve to methacholine. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1992;146(3):565–9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/146.3.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bosse Y, Pare PD, Seow CY. Airway wall remodeling in asthma: from the epithelial layer to the adventitia. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8(4):357–66. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simpson JL, Scott R, Boyle MJ, Gibson PG. Inflammatory subtypes in asthma: assessment and identification using induced sputum. Respirology. 2006;11(1):54–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2006.00784.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gomes RF, Bates JH. Geometric determinants of airway resistance in two isomorphic rodent species. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2002;130(3):317–25. doi: 10.1016/s0034-5687(02)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lambrecht BN, Kool M, Willart MA, Hammad H. Mechanism of action of clinically approved adjuvants. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21(1):23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu MY, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos E, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282(5396):2085–8. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yiamouyiannis CA, Schramm CM, Puddington L, Stengel P, Baradaran-Hosseini E, Wolyniec WW, Whiteley HE, Thrall RS. Shifts in lung lymphocyte profiles correlate with the sequential development of acute allergic and chronic tolerant stages in a murine asthma model. Am J Pathol. 1999;154(6):1911–21. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65449-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mehlhop PD, van de Rijn M, Goldberg AB, Brewer JP, Kurup VP, Martin TR, Oettgen HC. Allergen-induced bronchial hyperreactivity and eosinophilic inflammation occur in the absence of IgE in a mouse model of asthma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94(4):1344–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim J, Merry AC, Nemzek JA, Bolgos GL, Siddiqui J, Remick DG. Eotaxin represents the principal eosinophil chemoattractant in a novel murine asthma model induced by house dust containing cockroach allergens. J Immunol. 2001;167(5):2808–15. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.5.2808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wild JS, Sigounas A, Sur N, Siddiqui MS, Alam R, Kurimoto M, Sur S. IFN-gamma-inducing factor (IL-18) increases allergic sensitization, serum IgE, Th2 cytokines, and airway eosinophilia in a mouse model of allergic asthma. J Immunol. 2000;164(5):2701–10. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.5.2701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson RP, Jr, DiNicolo R, Fernandez-Caldas E, Seleznick MJ, Lockey RF, Good RA. Allergen-specific IgE levels and mite allergen exposure in children with acute asthma first seen in an emergency department and in nonasthmatic control subjects. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1996;98(2):258–63. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(96)70148-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hammad H, Chieppa M, Perros F, Willart MA, Germain RN, Lambrecht BN. House dust mite allergen induces asthma via Toll-like receptor 4 triggering of airway structural cells. Nat Med. 2009;15(4):410–6. doi: 10.1038/nm.1946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson RH, Whitehead GS, Nakano H, Free ME, Kolls JK, Cook DN. Allergic sensitization through the airway primes Th17-dependent neutrophilia and airway hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(8):720–30. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0573OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tully JE, Hoffman SM, Lahue KG, Nolin JD, Anathy V, Lundblad LK, Daphtary N, Aliyeva M, Black KE, Dixon AE, Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM. Epithelial NF-kappaB Orchestrates House Dust Mite-Induced Airway Inflammation, Hyperresponsiveness, and Fibrotic Remodeling. J Immunol. 2013;191(12):5811–21. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zosky GR, Larcombe AN, White OJ, Burchell JT, Janosi TZ, Hantos Z, Holt PG, Sly PD, Turner DJ. Ovalbumin-sensitized mice are good models for airway hyperresponsiveness but not acute physiological responses to allergen inhalation. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38(5):829–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nabe T, Zindl CL, Jung YW, Stephens R, Sakamoto A, Kohno S, Atkinson TP, Chaplin DD. Induction of a late asthmatic response associated with airway inflammation in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2005;521(1–3):144–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Phillips JE, Peng R, Harris P, Burns L, Renteria L, Lundblad LK, Fine JS, Bauer CM, Stevenson CS. House dust mite models: Will they translate clinically as a superior model of asthma? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.12.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levitt RC, Mitzner W. Expression of airway hyperreactivity to acetylcholine as a simple autosomal recessive trait in mice. FASEB J. 1988;2(10):2605–8. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.2.10.3384240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen GB, Leclair TR, von Reyn J, Larrabee YC, Cloutier ME, Irvin CG, Bates JH. Acid aspiration-induced airways hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2009;107(6):1763–70. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00572.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Turi GJ, Ellis R, Wattie JN, Labiris NR, Inman MD. The effects of inhaled house dust mite on airway barrier function and sensitivity to inhaled methacholine in mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;300(2):L185–90. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00271.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMillan SJ, Lloyd CM. Prolonged allergen challenge in mice leads to persistent airway remodelling. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(3):497–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.01895.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Johnson JR, Wiley RE, Fattouh R, Swirski FK, Gajewska BU, Coyle AJ, Gutierrez-Ramos JC, Ellis R, Inman MD, Jordana M. Continuous exposure to house dust mite elicits chronic airway inflammation and structural remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169(3):378–85. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200308-1094OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leigh R, Ellis R, Wattie J, Southam DS, De Hoogh M, Gauldie J, O’Byrne PM, Inman MD. Dysfunction and remodeling of the mouse airway persist after resolution of acute allergen-induced airway inflammation. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2002;27(5):526–35. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0048OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brusasco V, Crimi E, Barisione G, Spanevello A, Rodarte JR, Pellegrino R. Airway responsiveness to methacholine: effects of deep inhalations and airway inflammation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1999;87(2):567–73. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1999.87.2.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bates JH, Wagers SS, Norton RJ, Rinaldi LM, Irvin CG. Exaggerated airway narrowing in mice treated with intratracheal cationic protein. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2006;100(2):500–6. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.01013.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin JG, Campbell HR, Iijima H, Gautrin D, Malo JL, Eidelman DH, Hamid Q, Maghni K. Chlorine-induced injury to the airways in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;168(5):568–74. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200201-021OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Haldar P, Pavord ID, Shaw DE, Berry MA, Thomas M, Brightling CE, Wardlaw AJ, Green RH. Cluster analysis and clinical asthma phenotypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178(3):218–24. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200711-1754OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore WC, Meyers DA, Wenzel SE, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Jr, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston B, Jarjour NN, Sorkness R, Calhoun WJ, Chung KF, Comhair SA, Dweik RA, Israel E, Peters SP, Busse WW, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER. Identification of asthma phenotypes using cluster analysis in the Severe Asthma Research Program. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(4):315–23. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200906-0896OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Flurkey KC, JM, Harrison DE. The Mouse in Aging Research. In: Fox JGB, SW, Davisson MT, Newcomer CEQ, FW, Smith AL, editors. The Mouse in Biomedical Research: Normative Biology, Husbandry, and Models. Burlington, MA, USA: American College Laboratory Animal Medicine (Elsevier); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hanania NA, King MJ, Braman SS, Saltoun C, Wise RA, Enright P, Falsey AR, Mathur SK, Ramsdell JW, Rogers L, Stempel DA, Lima JJ, Fish JE, Wilson SR, Boyd C, Patel KV, Irvin CG, Yawn BP, Halm EA, Wasserman SI, Sands MF, Ershler WB, Ledford DK. Asthma in the elderly: Current understanding and future research needs--a report of a National Institute on Aging (NIA) workshop. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(3 Suppl):S4–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Busse PJ, Zhang TF, Srivastava K, Schofield B, Li XM. Effect of ageing on pulmonary inflammation, airway hyperresponsiveness and T and B cell responses in antigen-sensitized and -challenged mice. Clin Exp Allergy. 2007;37(9):1392–403. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2007.02775.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shore SA. Obesity, airway hyperresponsiveness, and inflammation. J Appl Physiol (1985) 2010;108(3):735–43. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00749.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kim HY, Lee HJ, Chang YJ, Pichavant M, Shore SA, Fitzgerald KA, Iwakura Y, Israel E, Bolger K, Faul J, DeKruyff RH, Umetsu DT. Interleukin-17-producing innate lymphoid cells and the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2014;20(1):54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.3423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sideleva O, Dixon AE. The many faces of asthma in obesity. J Cell Biochem. 2014;115(3):421–6. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ochkur SI, Jacobsen EA, Protheroe CA, Biechele TL, Pero RS, McGarry MP, Wang H, O’Neill KR, Colbert DC, Colby TV, Shen H, Blackburn MR, Irvin CC, Lee JJ, Lee NA. Coexpression of IL-5 and eotaxin-2 in mice creates an eosinophil-dependent model of respiratory inflammation with characteristics of severe asthma. J Immunol. 2007;178(12):7879–89. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.12.7879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McKinley L, Alcorn JF, Peterson A, Dupont RB, Kapadia S, Logar A, Henry A, Irvin CG, Piganelli JD, Ray A, Kolls JK. TH17 cells mediate steroid-resistant airway inflammation and airway hyperresponsiveness in mice. J Immunol. 2008;181(6):4089–97. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.6.4089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duechs MJ, Tilp C, Tomsic C, Gantner F, Erb KJ. Development of a Novel Severe Triple Allergen Asthma Model in Mice Which Is Resistant to Dexamethasone and Partially Resistant to TLR7 and TLR9 Agonist Treatment. PLoS One. 2014;9(3):e91223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rawlins EL, Perl AK. The a“MAZE”ing world of lung-specific transgenic mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012;46(3):269–82. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0372PS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hart LA, Krishnan VL, Adcock IM, Barnes PJ, Chung KF. Activation and localization of transcription factor, nuclear factor-kappaB, in asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158(5 Pt 1):1585–92. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.5.9706116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Poynter ME, Cloots R, van Woerkom T, Butnor KJ, Vacek P, Taatjes DJ, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM. NF-kappa B activation in airways modulates allergic inflammation but not hyperresponsiveness. J Immunol. 2004;173(11):7003–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.7003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Broide DH, Lawrence T, Doherty T, Cho JY, Miller M, McElwain K, McElwain S, Karin M. Allergen-induced peribronchial fibrosis and mucus production mediated by IkappaB kinase beta-dependent genes in airway epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(49):17723–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509235102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pantano C, Ather JL, Alcorn JF, Poynter ME, Brown AL, Guala AS, Beuschel SL, Allen GB, Whittaker LA, Bevelander M, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YM. Nuclear factor-kappaB activation in airway epithelium induces inflammation and hyperresponsiveness. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177(9):959–69. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-1096OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ather JL, Hodgkins SR, Janssen-Heininger YM, Poynter ME. Airway epithelial NF-kappaB activation promotes allergic sensitization to an innocuous inhaled antigen. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2011;44(5):631–8. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0106OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Naseer T, Minshall EM, Leung DY, Laberge S, Ernst P, Martin RJ, Hamid Q. Expression of IL-12 and IL-13 mRNA in asthma and their modulation in response to steroid therapy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;155(3):845–51. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.3.9117015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Grunig G, Warnock M, Wakil AE, Venkayya R, Brombacher F, Rennick DM, Sheppard D, Mohrs M, Donaldson DD, Locksley RM, Corry DB. Requirement for IL-13 independently of IL-4 in experimental asthma. Science. 1998;282(5397):2261–3. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5397.2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Leigh R, Ellis R, Wattie J, Donaldson DD, Inman MD. Is interleukin-13 critical in maintaining airway hyperresponsiveness in allergen-challenged mice? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170(8):851–6. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200311-1488OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Corren J, Lemanske RF, Hanania NA, Korenblat PE, Parsey MV, Arron JR, Harris JM, Scheerens H, Wu LC, Su Z, Mosesova S, Eisner MD, Bohen SP, Matthews JG. Lebrikizumab treatment in adults with asthma. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(12):1088–98. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1106469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nair P, Pizzichini MM, Kjarsgaard M, Inman MD, Efthimiadis A, Pizzichini E, Hargreave FE, O’Byrne PM. Mepolizumab for prednisone-dependent asthma with sputum eosinophilia. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(10):985–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chung KF, Wenzel SE, Brozek JL, Bush A, Castro M, Sterk PJ, Adcock IM, Bateman ED, Bel EH, Bleecker ER, Boulet LP, Brightling C, Chanez P, Dahlen SE, Djukanovic R, Frey U, Gaga M, Gibson P, Hamid Q, Jajour NN, Mauad T, Sorkness RL, Teague WG. International ERS/ATS guidelines on definition, evaluation and treatment of severe asthma. Eur Respir J. 2014;43(2):343–73. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00202013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harpsoe MC, Basit S, Bager P, Wohlfahrt J, Benn CS, Nohr EA, Linneberg A, Jess T. Maternal obesity, gestational weight gain, and risk of asthma and atopic disease in offspring: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(4):1033–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Emberson LD, Kitwiroon N, Beevers S, Büker P, Cinderby S. Scorched Earth: how will changes in the strength of the vegetation sink to ozone deposition affect human health and ecosystems? Atmos Chem Phys. 2013;13(14):6741–55. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Prudhomme C, Giuntoli I, Robinson EL, Clark DB, Arnell NW, Dankers R, Fekete BM, Franssen W, Gerten D, Gosling SN, Hagemann S, Hannah DM, Kim H, Masaki Y, Satoh Y, Stacke T, Wada Y, Wisser D. Hydrological droughts in the 21st century, hotspots and uncertainties from a global multimodel ensemble experiment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(9):3262–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1222473110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lu FL, Johnston RA, Flynt L, Theman TA, Terry RD, Schwartzman IN, Lee A, Shore SA. Increased pulmonary responses to acute ozone exposure in obese db/db mice. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2006;290(5):L856–65. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00386.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Alexeeff SE, Litonjua AA, Suh H, Sparrow D, Vokonas PS, Schwartz J. Ozone exposure and lung function: effect modified by obesity and airways hyperresponsiveness in the VA normative aging study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1890–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lundblad LK, Thompson-Figueroa J, Allen GB, Rinaldi L, Norton RJ, Irvin CG, Bates JH. Airway hyperresponsiveness in allergically inflamed mice: the role of airway closure. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(8):768–74. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200610-1410OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]