Abstract

The incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) has increased in the past several years, yet our understanding of its pathogenesis remains limited. To test the hypothesis that microRNAs (miRNAs) are altered in children with EoE, miRNAs were profiled in esophageal mucosa biopsies obtained from patients with active disease (n = 5) and healthy control subjects (n = 6). Fourteen miRNAs were significantly altered between groups; four of these miRNAs were decreased in EoE patients. A panel of five miRNAs (miR-203, miR-375, miR-21, miR-223, and miR-142-3p) were selected for validation in an independent set of samples from control (n = 22), active disease (n = 22), inactive disease (n = 22), and gastroesophageal reflux disease (n = 6) patients. Each panel miRNA was significantly altered among groups. miRNA changes in esophageal biopsies were not reflected in the circulating RNA pool, as no differences in panel miRNA levels were observed in sera collected from the four patient groups. In addition, in contrast to previous studies, no change in esophageal miRNA levels was detected following treatment that resolved esophageal eosinophilia. In an effort to identify the ramifications of reduced esophageal miR-203, miR-203 activity was inhibited in cultured epithelial cells via expression of a tough decoy miRNA inhibitor. Luciferase reporter assays demonstrated that miR-203 does not directly regulate human IL-15 through targeting of the IL-15 3′-untranslated region. From these experiments, it is concluded that miRNAs are perturbed in the esophageal mucosa, but not the serum, of pediatric EoE patients. Further investigation is required to decipher pathologically relevant consequences of miRNA perturbation in this context.

Keywords: eosinophilic esophagitis, microRNA, serum microRNA, circulating microRNA, atopic disease

eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by infiltration of eosinophils into the esophageal mucosa in response to allergen exposure. Other prominent histological features of EoE include elevated levels of B and T cells, activated mast cells, and basal cell hyperplasia (1, 3, 43, 45). In young children, EoE can lead to feeding refusal/intolerance and failure to thrive, while older children often complain of chronic dysphagia and food impaction. Other complications include esophageal stricture and spontaneous perforation. Genome-wide association analyses have identified EoE risk variants, most notably, mapping to regions that include thymic stromal lymphopoietin, a cytokine elevated in EoE, and CAPN14, a protein-coding gene expressed in the esophagus and upregulated by IL-13 (20, 33, 38). However, despite a rapid increase in EoE diagnoses in children and adults, the instigating and perpetuating mechanisms of the disease remain largely unknown (9). Differentiated epithelial cells of the gastrointestinal tract facilitate cross talk with the external environment by regulating local innate and adaptive immune cells (31, 37, 54). Thus, changes in the architecture and differentiation status of the esophageal epithelium associated with EoE are likely to perturb local homeostatic immune signaling.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are regulatory RNAs that function to destabilize target mRNAs by recruiting RNA-induced silencing complex machinery. miRNAs are potent modulators of inflammatory signaling cascades (19, 34, 47) and are necessary for homeostatic maintenance in the gastrointestinal tract (5, 28). Changes in esophageal miRNAs have been observed in EoE and other esophageal pathologies (11, 24, 26, 51). Using a quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR)-based platform, T. X. Lu et al. (26) profiled miRNAs in human esophageal biopsies from healthy subjects and pediatric EoE patients. They identified 21 upregulated and 11 downregulated miRNAs in the EoE sample group. Subsequently, S. Lu et al. (24) found six esophageal miRNAs to be altered in pediatric EoE patients. Yet virtually nothing is known regarding the consequences of altered miRNA regulation in these contexts. In addition, T. X. Lu et al. reported altered circulating miRNAs in EoE, raising the possibility of a novel, noninvasive biomarker.

The goals of this study were to assess mucosal miRNA abundance in the esophagus of pediatric EoE patients and healthy controls and to independently validate the miRNA changes reported in previous studies. Esophageal miRNAs were profiled in pediatric EoE patients and healthy controls, and the results were confirmed in large, independent sample sets. Some of the most abundant esophageal miRNAs were perturbed in EoE patients. However, changes in esophageal miRNA levels were not reflected in the circulating miRNA fraction. Longitudinal analyses found that esophageal miRNA levels did not track with improved eosinophil counts following medical and dietary therapy. Luciferase reporter assays suggested that miR-203 does not regulate human IL-15, despite the presence of a predicted miR-203 binding site within its 3′-untranslated region (UTR).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patient samples.

Each patient or parent/guardian provided informed consent to participate in the study. Esophageal biopsies and/or blood samples were obtained during upper endoscopy as part of an Institutional Review Board-approved study at the Children's Hospital of Philadelphia Research Institute. Control samples were obtained from patients whose endoscopy and histology results were normal, despite upper gastrointestinal symptoms. EoE and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) diagnoses were determined by the treating physician according to clinical, endoscopic, and histological findings. Active EoE was defined by a peak eosinophil count of ≥15 per high-power field (hpf), along with symptoms of esophageal dysfunction and a lack of response to ≥6 wk of proton pump inhibitor treatment (13, 23). Inactive EoE patients were those who were previously diagnosed with active EoE but had <15 eosinophils per hpf at the time of biopsy. GERD patients were defined as having symptoms consistent with reflux esophagitis but <10 eosinophils per hpf on biopsy. Patient demographic and clinical information is provided in Tables 1 and 2. Esophageal biopsies collected during endoscopy were immediately flash-frozen and stored at −80°C until they were processed. Blood samples were stored at room temperature for 30 min, centrifuged twice sequentially at 855 g for 10 min each to remove blood cells, and stored at −80°C until they were processed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients in case-control experiments

| EoE |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Active | Inactive | Healthy | GERD | |

| Serum subjects | ||||

| n | 17 | 17 | 10 | 12 |

| Eos/hpf | 42.5 ± 15.6 | 2.2 ± 2.2* | Not detected | 3.7 ± 2.9* |

| Age, yr | 9.7 ± 4.8 | 9.1 ± 5.0 | 8.5 ± 6.1 | 10.1 ± 5.9 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 16 (90) | 16 (90) | 9 (90) | 10 (80) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 16 (90) | 16 (90) | 9 (90) | 11 (90) |

| History of atopy, n (%) | 16 (90) | 16 (90) | 4 (40) | 6 (50) |

| Asthma | 10 (60) | 10 (60) | 1 (10) | 5 (40) |

| Atopic rhinitis | 9 (50) | 10 (60) | 1 (10) | 2 (20) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 9 (50) | 5 (30) | 2 (20) | 4 (30) |

| Age at EoE diagnosis, yr | 7.9 ± 6.0 | 6.2 ± 5.1 | ||

| EoE treatment, n (%) | ||||

| None | 6 (35) | 0 (0)* | ||

| Diet | 10 (59) | 16 (94)* | ||

| STS | 1 (6) | 0 (0) | ||

| Diet and STS | 0 (0) | 1 (6) | ||

| Tissue subjects | ||||

| N | 27 | 22 | 28 | 6 |

| Eos/hpf | 39.1 ± 15.7 | 2.2 ± 3.3* | Not detected | 3.8 ± 2.1* |

| Age, yr | 10.8 ± 4.6 | 8.6 ± 4.8 | 9.6 ± 5.2 | 8.6 ± 7.1 |

| Sex, male, n (%) | 20 (91) | 20 (91) | 24 (86) | 6 (100) |

| Race, white, n (%) | 20 (91) | 20 (91) | 26 (93) | 5 (83) |

| History of atopy, n (%) | 19 (86) | 19 (86) | 19 (68) | 3 (50) |

| Asthma | 8 (36) | 13 (59) | 13 (46) | 3 (50) |

| Atopic rhinitis | 12 (55) | 10 (45) | 2 (7) | 2 (33) |

| Atopic dermatitis | 15 (68) | 7 (32) | 6 (21) | 1 (17) |

| Age at EoE diagnosis, yr | 9.4 ± 5.3 | 6.2 ± 4.9 | ||

| EoE treatment, n (%) | ||||

| None | 17 (63) | 0 (0)* | ||

| Diet | 7 (26) | 20 (91)* | ||

| STS | 2 (7) | 2 (9) | ||

Values for continuous variables are means ± SD. EoE, eosinophilic esophagitis; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; Eos, eosinophils; hpf, high-power field; STS, swallowed topical steroids. No statistical difference by analysis of variance between groups for age, sex, race, or atopy, unless otherwise indicated.

P < 0.05 vs. active EoE.

Table 2.

Characteristics of patients in longitudinal experiments

| Responding (n = 12) | Nonresponding (n = 12) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age at 1st biopsy, yr | 11.7 ± 4.5 | 8.5 ± 5.1 |

| Age at diagnosis, yr | 10.0 ± 4.6 | 6.6 ± 6.3 |

| Sex, male, % | 91.7 | 75.0 |

| Race, white, % | 50.0* | 75.0 |

| History of atopy, % | 100.0 | 83.3 |

| Asthma, % | 100.0* | 58.3 |

| Allergic rhinitis, % | 58.3 | 41.7 |

| Atopic dermatitis, % | 66.7 | 50.0 |

| Eos/hpf | ||

| 1st biopsy | 37.7 ± 22.3 | 32.1 ± 15.1 |

| 2nd biopsy | 2.9 ± 4.3 | 53.0 ± 32.9 |

| Time between biopsies, wk | 33.8 ± 25.0 | 28.0 ± 20.4 |

| Intervention between biopsies, n (%) | ||

| Elemental diet | 1 (8) | 1 (8) |

| Elimination diet | ||

| Multiple foods | 1 (8) | 3 (25) |

| Single food | 1 (8) | 5 (33) |

| STS | ||

| OVB | 6 (50) | 0 (0) |

| Fluticasone | 2 (17) | 1 (8) |

| Diet and STS | 1 (8) | 2 (17) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 0 (0) | 1 (8) |

Values for continuous variables are means ± SD. OVB, oral viscous budesonide.

P < 0.05 vs. nonresponding (by χ2 test).

RNA isolation.

Flash-frozen esophageal biopsies were pulverized in microcentrifuge tubes on dry ice using a chilled pestle and immediately processed. Total RNA from esophageal tissue or 60 μl of serum was isolated using the mirVana miRNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. During serum RNA isolation, the exogenous Caenorhabditis elegans miRNAs cel-miR-54 and cel-miR-238 [22.5 and 15 pM, respectively, added as normalizing controls (30)] and MS2 RNA [3 μg, used to increase RNA recovery (2)] were added immediately following serum denaturation. For serum samples used in the profiling experiment, 3 μl of a spike solution containing exogenous miR-302a, miR-302d, and miR-372 (5, 5, and 10 pM, respectively) were added as positive controls. RNA samples were eluted in a volume of 100 μl.

miRNA profiling.

Tissue miRNA levels were profiled using the nCounter human version 1 miRNA expression assay kit (nanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA). Data were processed after removal of all counts of miRNAs measured by the nCounter human version 1 kit that are no longer recognized by miRBase release 20 (15, 53). Individual miRNA counts were normalized to the total counts for each sample. Serum miRNA levels were profiled using the TaqMan Low Density Array Human MicroRNA Panels A and B version 2.0 (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY). Three microliters of total serum RNA were used as input in a 7.5-μl RT reaction. Twelve cycles of cDNA preamplification were then performed using 2.5 μl of the RT reaction product as input according to the manufacturer's instructions. Serum miRNA array data were normalized using the median threshold cycle (Ct) of each array, and individual miRNA levels were calculated as 2(Ct,median − Ct,miRNA).

Quantitative RT-PCR.

RT was performed using the TaqMan MicroRNA RT and miRNA assay kits (Life Technologies) with 33.3 ng of tissue RNA or 3.33 μl of eluted serum RNA as input. Amplification was performed in duplicate using TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix and miRNA assay kits (Life Technologies). Tissue miRNA data were normalized to the mean Ct of RNU44 and RNU48 levels. Serum miRNA data were normalized to the mean Ct of cel-miR-54 and cel-miR-238. miRNA levels were calculated as 2(Ct,median − Ct,miRNA). Interplate calibration was performed with four calibrator samples using the method of Hellemans et al. (17).

Cell culture and luciferase assays.

A 601-bp fragment containing 492 bp of the human IL-15 3′-UTR was amplified from IMAGE consortium cDNA clone 40044736 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and subcloned into pMiRCheck2 (16). The miR-203 sensor plasmid was constructed by replacement of the XhoI-NotI fragment of pMiRCheck2 with a double-stranded oligonucleotide containing two miR-203 target sequences (miR-203 reverse complement, with a central bulged mismatch) separated by a five-nucleotide spacer. A tough decoy (“TuD” miRNA inhibitor) expression vector platform “pEN TuDparent,” analogous to that described by Xie et al. (50), was generated by ligation of a double-stranded oligonucleotide (hU6TuD-top/hU6TuD-bot) into NdeI-XbaI-digested pEN_hu6 miRc2 (41). pEN_TuDctrl and pEN_TuD203 were generated by replacement of the BfuAI fragment in pEN TuDparent with double-stranded oligonucleotides containing scrambled miRNA binding sites or sites that act as decoys for miR-203. The resulting plasmids constitutively express TuD hairpins from the RNA polymerase III-dependent human U6 promoter. Oligonucleotides utilized in this study are listed in Table 3. MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma epithelial cells (American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and penicillin-streptomycin. For luciferase reporter experiments, 5.0 × 104 cells were seeded in 24-well plates and transfected 24 h later with 900 ng of expression vector and 10 ng of luciferase reporter using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Promega, Madison, WI) in the absence of antibiotics. Lysates were collected 24 h after transfection and assayed for Renilla and firefly luciferase activities using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System (Promega).

Table 3.

Oligonucleotides used in subcloning experiments

| Oligonucleotide/Primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

| hU6TuD | |

| Top | TATGCTTACCGTAACTTGAAAGTATTTCGATTTCTTGGCTTTATATATCTTGTGGAAAGGACGAAACACCGACGGCGCTAGGATCATCTGCTGCAGGTAAGCTTGAGGTATATAGAATTCCAACCTGCTGCTATGATCCTAGCGCCGTCTTTTTTTAT |

| Bottom | CTAGATAAAAAAAGACGGCGCTAGGATCATAGCAGCAGGTTGGAATTCTATATACCTCAAGCTTACCTGCAGCAGATGATCCTAGCGCCGTCGGTGTTTCGTCCTTTCCACAAGATATATAAAGCCAAGAAATCGAAATACTTTCAAGTTACGGTAAGCA |

| TuDctrl | |

| Top | CATCAACGTGTAACACGTCATCTTATACGCCCACAAGTATTCTGGTCACAGAATACAACGTGTAACACGTCATCTTATACGCCCACAAG |

| Bottom | TCATCTTGTGGGCGTATAAGATGACGTGTTACACGTTGTATTCTGTGACCAGAATACTTGTGGGCGTATAAGATGACGTGTTACACGTT |

| TuD203 | |

| Top | CATCAACCTAGTGGTCCTCTACAAACATTTCACCAAGTATTCTGGTCACAGAATACAACCTAGTGGTCCTCTACAAACATTTCACCAAG |

| Bottom | TCATCTTGGTGAAATGTTTGTAGAGGACCACTAGGTTGTATTCTGTGACCAGAATACTTGGTGAAATGTTTGTAGAGGACCACTAGGTT |

| 203 sensor | |

| Top | TCGAGATAACTAGTGGTCCCAACATTTCACACACACTAGTGGTCCCAACATTTCACTTATGC |

| Bottom | GGCCGCATAAGTGAAATGTTGGGACCACTAGTGTGTGTGAAATGTTGGGACCACTAGTTATC |

| IL-15 PCR | |

| Forward | AATATTCTCGAGTGTAACAGAATCTGGATGCAA |

| Reverse | AATATTGCGGCCGCTTCCTCTGTTTGCTATGCTT |

Statistical analyses.

Expression profiling data sets from the nCounter and TaqMan low-density array experiments were analyzed using Statistical Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) software (Stanford University, Stanford, CA) (44). All other statistical analyses were performed using Stata 11.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). The correlation heat map was created using Matrix2png (35). Hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using complete linkage with Euclidean distance for all esophageal miRNAs detected above background in all samples. Differences in miRNA levels were determined using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance by ranks. To control for multiple testing, post hoc comparisons were performed using Holm-Bonferroni-corrected P values. Correlations among variables were determined using the Spearman rank-order correlation test with Bonferroni-corrected P values. Longitudinal changes in miRNA levels were determined using multilevel mixed-effects linear regression. The critical significance level α was defined as 0.05.

RESULTS

Profiling of esophageal miRNA in pediatric EoE.

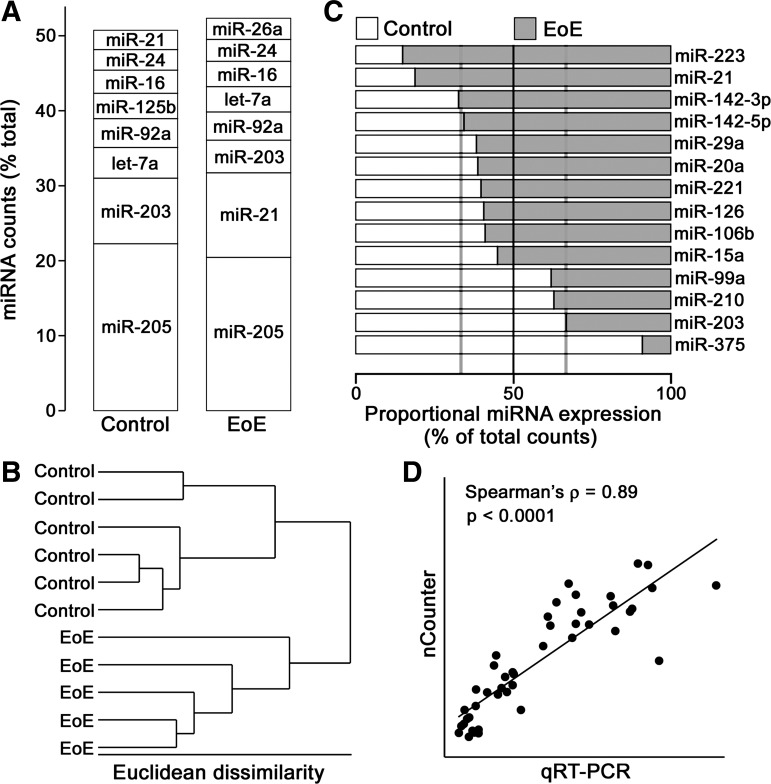

Esophageal miRNAs in biopsies obtained from pediatric patients with EoE (n = 5) and controls (n = 6) were profiled using the nCounter human version 1 miRNA expression assay kit. This platform can detect >600 human miRNAs without the need for input amplification. miR-205 was the most abundant miRNA in both sample groups, accounting for >20% of the total miRNA in the esophageal mucosa (Fig. 1A, Table 4). In both groups, the eight most-abundant miRNAs together accounted for >50% of the total miRNA detected. Hierarchical cluster analysis revealed that esophageal miRNA levels distinguish healthy esophageal tissue from esophageal tissue of EoE patients (Fig. 1B). SAM determined that 14 miRNAs were significantly altered between groups (Fig. 1C). Four miRNAs, including miR-203, the second-most-abundant miRNA in control samples, were decreased in EoE patients. To confirm the results of the profiling experiment, four differentially expressed miRNAs (miR-21, miR-142-3p, miR-375, and miR-203) were measured by qRT-PCR in the same sample set. These miRNAs were selected on the basis of highest abundance among altered miRNAs in control or active EoE samples (Table 4). As shown in Fig. 1D, miRNA levels were highly correlated between platforms.

Fig. 1.

Esophageal microRNA (miRNA) profiling in pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). A: column graph displaying the 8 most-abundant miRNAs in esophageal biopsies from control and EoE patients as determined by the nCounter platform. miRNA levels are presented as percentage of total miRNA counts. B: dendogram showing results of complete linkage hierarchical cluster analysis using the 74 miRNAs detected above background in each sample. C: column graph displaying relative levels of each of 14 miRNAs significantly altered between control and EoE samples as determined by Statistical Analysis of Microarrays. Gray vertical lines represent thresholds for a 2-fold difference in expression between groups. D: scatterplot of relative miR-21, miR-142-3p, miR-375, and miR-203 levels as determined by the nCounter platform and TaqMan quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) assays. Levels of the 4 miRNAs were significantly correlated between detection methods. ρ, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

Table 4.

miRNA abundance in esophageal biopsies

| Healthy Controls |

Active EoE Patients |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| miRNA | Abundance, % total counts | miRNA | Abundance, % total counts |

| miR-205 | 23.40 | miR-205 | 20.93 |

| miR-203 | 9.15 | miR-21 | 10.42 |

| let-7a | 4.30 | miR-203 | 4.82 |

| miR-92a | 4.06 | miR-92a | 3.87 |

| miR-125b | 3.55 | let-7a | 3.65 |

| miR-16 | 3.21 | miR-16 | 3.40 |

| miR-24 | 2.87 | miR-26a | 2.92 |

| miR-21 | 2.73 | miR-24 | 2.92 |

| miR-1260 | 2.63 | miR-1260 | 2.82 |

| miR-26a | 2.44 | miR-125b | 2.63 |

| let-7 g | 2.32 | let-7 g | 2.24 |

| miR-200c | 2.21 | miR-142-3p | 2.11 |

| miR-23a | 2.09 | miR-451 | 2.05 |

| miR-451 | 1.79 | miR-23a | 1.89 |

| miR-200b | 1.57 | miR-126 | 1.84 |

| let-7b | 1.44 | miR-200c | 1.78 |

| miR-375 | 1.43 | miR-29a | 1.74 |

| miR-126 | 1.33 | miR20a + 20b | 1.60 |

| miR-23b | 1.28 | let-7b | 1.34 |

| miR-99a | 1.18 | miR-221 | 1.20 |

| miR-29a | 1.14 | miR-200b | 1.20 |

| miR-15b | 1.11 | miR-223 | 1.18 |

| let-7f | 1.11 | let-7f | 1.12 |

| miR-20a + 20b | 1.05 | miR-23b | 1.10 |

| miR-30b | 1.04 | miR-15a | 1.08 |

| miR-142-3p | 1.03 | miR-30b | 1.03 |

| miR-103 | 1.01 | ||

miRNA, microRNA.

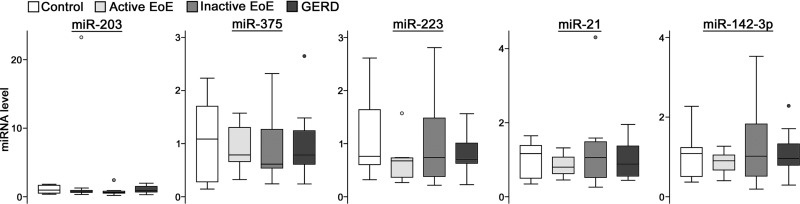

Validation of EoE-specific changes in esophageal miRNA.

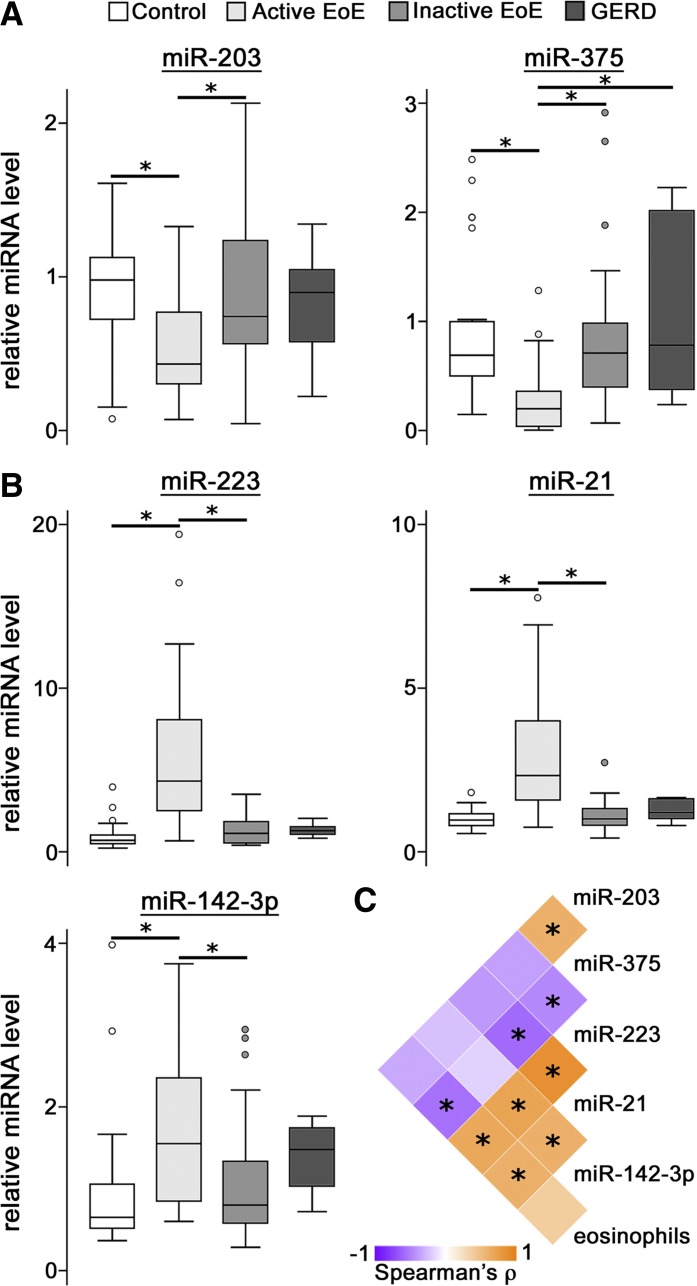

To confirm EoE-associated changes in esophageal miRNAs, qRT-PCR was performed on samples from a distinct set of control (n = 22), active EoE (n = 22), inactive EoE (n = 22), and GERD (n = 6) patients. A panel of five miRNAs from those identified as significantly altered in active EoE by the profiling experiment were selected for validation based on a twofold change in mean expression between controls and EoE samples. Each panel miRNA was significantly altered among the four patient groups of the validation set (Fig. 2, A and B). All panel miRNAs were altered in active EoE patients compared with inactive EoE patients and healthy controls. All three miRNAs elevated in active EoE patients were positively correlated with each other (Fig. 2C). In addition, eosinophil counts were significantly negatively correlated with miR-375 and positively correlated with miR-223 and miR-21. However, when the analysis was restricted to active EoE samples, eosinophil counts were not significantly correlated with any panel miRNA (data not shown). This finding may be due to the discontinuous nature of inflammation observed in the disease.

Fig. 2.

Confirmation of EoE-associated esophageal miRNAs. A and B: box plots showing decreased (A) or elevated (B) relative levels of panel miRNAs in active EoE patients. miRNA levels are scaled such that the mean of control samples is equal to 1. Each miRNA was significantly altered at Kruskal-Wallis P < 0.05. Box, 1st–3rd quartiles; line, median; whiskers, adjacent values; ○, data points outside adjacent values. *Holm-Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.05. C: heat map showing correlation among panel miRNAs and eosinophil counts. Correlation among all samples was determined using the Spearman rank-order correlation test. *Bonferroni-corrected P < 0.05. GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; ρ, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient.

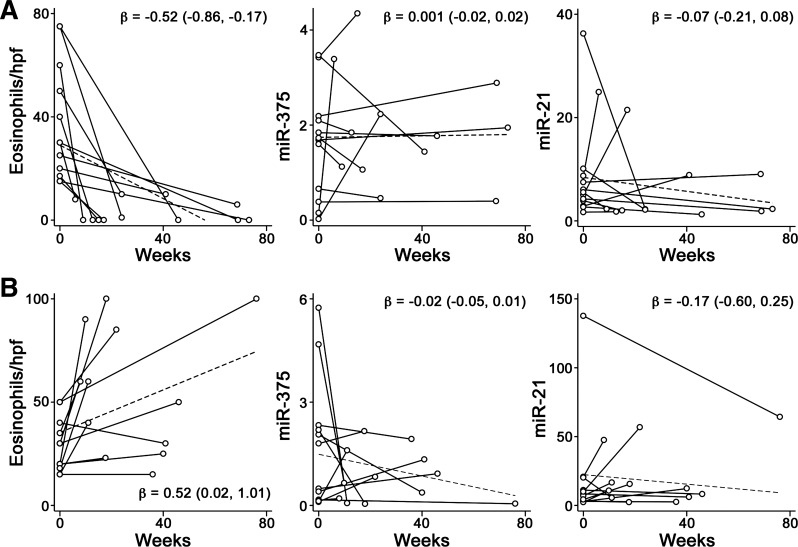

Esophageal miRNA levels are unchanged following treatment.

Changes in esophageal miRNAs in response to corticosteroid treatment have been demonstrated in EoE patients (24). Here, a longitudinal study of esophageal miRNA levels was performed in patients that responded (n = 12) or did not respond (n = 12) to therapeutic intervention (Table 2). All patients had a maximum eosinophil count of ≥15 per hpf at the initial time point. After treatment, patients were classified as responding to treatment if eosinophil counts were ≤10 per hpf or as nonresponding if eosinophil counts were ≥15 per hpf. miR-375 and miR-21 were selected for analysis, because the P values for these miRNAs were the lowest among those decreased and increased, respectively, in the case-control study. Despite a significant drop in eosinophil counts at the follow-up time point, esophageal miR-375 and miR-21 levels were not altered in the responding group (Fig. 3A). The nonresponding group had significantly higher eosinophil counts at the second time point but also showed no change in miRNA levels (Fig. 3B). When the analyses were restricted to those patients receiving only steroid treatment, miRNA levels remained unchanged.

Fig. 3.

Longitudinal study of esophageal miRNAs in EoE patients. A and B: spaghetti plots showing eosinophil and miRNA levels in esophageal biopsies from patients with improved (A) or unimproved (B) eosinophilia (n = 12 each) at a follow-up clinical visit. Eosinophil numbers are presented as highest count in a high-power field (hpf). miRNA levels were normalized as described in materials and methods. Dashed lines indicate least-squares lines. β, Slope of the least-squares line. 95% confidence intervals of β are shown in parentheses.

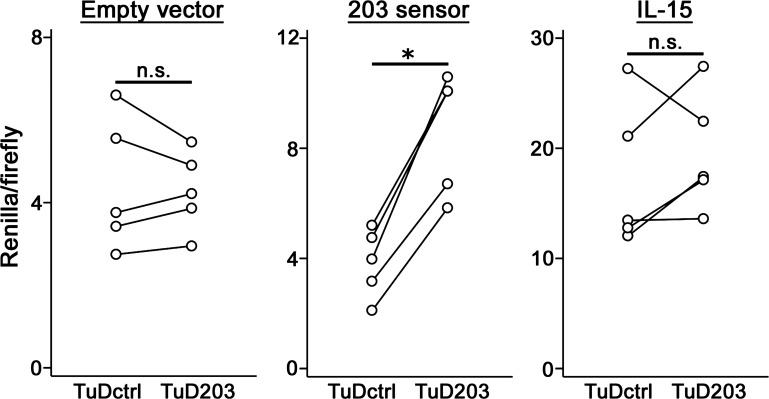

IL-15 is not a direct target of miR-203.

The reduction of miR-203 in EoE represents a dramatic shift in esophageal miRNA content, and the accompanying loss of target regulation may affect relevant pathological signaling pathways. IL-15, a cytokine required for allergen-induced inflammation, has been implicated in EoE pathogenesis (6, 33, 34, 49). Bioinformatic methods predict a miR-203 binding site in the human IL-15 3′-UTR (10, 18, 35). To determine if IL-15 mRNA is targeted by miR-203, human MCF-7 cells were transfected with a luciferase reporter construct containing a 492-bp region of the 3′-UTR of human IL-15 that includes the predicted miR-203 binding site. MCF-7 cells, instead of a human esophageal epithelial cell line, were selected, because they are highly amenable to efficient transfection and express elevated levels of miR-203 (21). A construct expressing a TuD RNA targeting mature miR-203 (TuD203) was used to inhibit miR-203 activity in MCF-7 cells. To demonstrate the efficacy of TuD203, MCF-7 cells were cotransfected with pMiRCheck2 expressing Renilla luciferase with two tandem miR-203 recognition sites in the 3′-UTR (203 sensor) and TuD203. Renilla luciferase expression was significantly derepressed in the presence of TuD203 (Fig. 4). However, miR-203 inhibition by TuD203 did not affect luciferase activity in cells transfected with the IL-15 3′-UTR reporter plasmid, suggesting that human IL-15 is not regulated by miR-203.

Fig. 4.

Effect of miR-203 on the IL-15 3′-untranslated region (UTR). Paired dot plots show Renilla/firefly luciferase activity in MCF-7 human breast adenocarcinoma epithelial cells cotransfected with a luciferase reporter and a tough decoy (TuD) construct. TuD203 expression construct significantly increased Renilla luciferase activity in cells cotransfected with the 203 sensor construct, but not in cells cotransfected with an empty vector or the IL-15 construct. Each data point represents mean of 3 technical replicates. Lines indicate paired experiments performed in parallel. *P < 0.05 (Wilcoxon's signed-rank test). ns, No significant difference between groups. TuDctrl, TuD containing scrambled sequence binding sites; TuD203, TuD containing miR-203 binding sites.

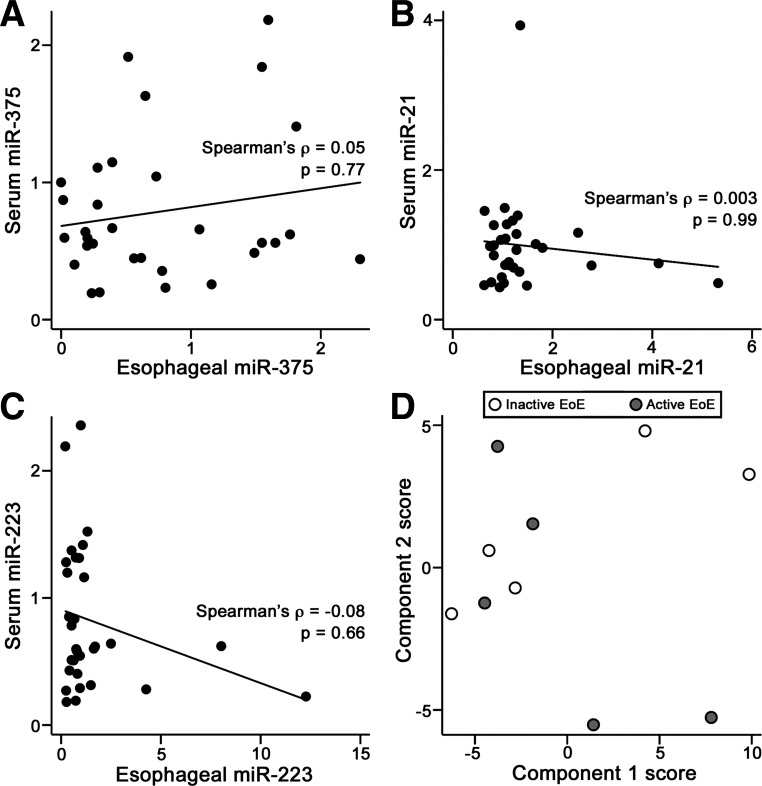

Esophageal miRNA changes are not reflected in the circulating RNA pool.

Altered levels of circulating miRNAs have been reported in pediatric EoE (26). Here, circulating levels of EoE-associated esophageal miRNAs were measured in sera of control (n = 11), active EoE (n = 12), inactive EoE (n = 12), and GERD (n = 12) patients via qRT-PCR. No significant difference between groups was observed for any of the panel miRNAs (Fig. 5). Among the 27 patients for whom both esophageal and serum miRNAs were measured, there was no significant correlation between esophageal and serum levels for any of the five panel miRNAs (Fig. 6, A–C; data not shown). To determine if other circulating miRNAs are altered in pediatric EoE, serum miRNAs were profiled in patients with active EoE (n = 5) and inactive EoE (n = 5) using a low-density qRT-PCR array platform. No discernable separation between sample groups was evident following principal component analysis (Fig. 6D). SAM analysis revealed that no miRNAs were significantly altered between sample groups (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Serum miRNAs in pediatric EoE. Box plots display relative serum levels of the 5 panel miRNAs. miRNA levels were normalized as described in materials and methods and scaled such that the mean of control samples is equal to 1. No significant differences in miRNA levels were observed among the sample groups. Box, 1st–3rd quartiles; line, median; whiskers, adjacent values; ○, data points outside adjacent values.

Fig. 6.

Serum miRNAs in pediatric EoE. A–C: scatterplots of miR-375, miR-21, and miR-223 levels in serum and esophagus of 31 patients. Each data point indicates a single subject. Solid lines indicate linear least-squares lines. miRNA levels were scaled such that the mean of control samples is equal to 1. D: score plot showing the first 2 components of a principal component analysis using data from the 80 serum miRNAs detected in all active and inactive EoE samples (n = 5 each). Components 1 and 2 together account for >52% of total variance. ρ, Spearman's rank correlation coefficient. No discernable separation is observed between active and inactive EoE samples.

DISCUSSION

The present study has characterized miRNA abundance in esophageal biopsies of control and pediatric patients with EoE, an important advance in our knowledge of miRNA in this disease. In EoE patients, miR-375 showed the largest reduction by fold change, consistent with a previous study (26). However, because miR-375 was the 17th-most-abundant miRNA in the esophageal mucosa of controls (accounting for 1.43% of measured transcripts), the more abundant miR-21 and miR-203 showed larger changes in transcript numbers. The second-most-abundant esophageal miRNA in control subjects, miR-203, was reduced twofold in EoE. This reduction of miR-203 may reflect the basal layer hyperplasia and the loss of differentiated epithelium observed in EoE. Indeed, miR-203 expression is over fivefold higher in the differentiated epithelium than the basal layer in the human esophagus (56). However, basal layer hyperplasia is also a prominent feature of reflux esophagitis, and no difference in miR-203 was observed between control and GERD patients. In contrast, the large increase in miR-21, miR-223, and miR-142-3p transcripts in the EoE mucosa may reflect the influx and expansion of immune cells characteristic of the disease, as these miRNAs are highly expressed in myeloid and lymphoid cell populations (8, 25, 49). miR-21 is widely expressed and is abundant in differentiated epithelial cells and basal cells of the human esophagus (56); hence, the increase in EoE tissue may, instead, result from expansion of the basal layer. Transcripts targeted by miR-21, including transforming growth factor-β1 and suppressor of cytokine signaling 5, may play an important role in pediatric EoE pathogenesis (12, 14, 27).

Esophageal miRNA-203 expression is elevated in the differentiated epithelium layer compared with underlying basal cells (56). The reduction of miR-203 in EoE may alter immune cell regulation. miR-203 has been shown to repress the expression of inflammatory modulators, including TNFα, IL-24, and suppressor of cytokine signaling 3, in keratinocytes (36). IL-15, a γ-chain family cytokine produced by several cell types, including keratinocytes, is required for allergen-induced T helper type 2 (Th2) cell immune responses in vivo (39, 40). IL-15 mRNA levels are elevated in the esophagus of pediatric EoE patients, and IL-15 induces epithelial eotaxin production in a mouse model of EoE (7, 57). The 3′-UTR of IL-15 contains a predicted miR-203 binding site, but miR-203 was not found to negatively regulate IL-15 in vitro. Although no evidence of transcript regulation was identified via luciferase assay, definitive evidence will require experiments detecting endogenous mRNA and protein levels following miR-203 perturbation in human esophageal epithelial cells. Interestingly, a single-nucleotide polymorphism (rs10519613) located in the predicted miR-203 binding site of the IL-15 3′-UTR is associated with an increased risk of psoriasis vulgaris (55), pediatric asthma (4), and minimal residual disease (52). The possibility remains that rs10519613 alters miR-203-loaded RNA-induced silencing complex functionality at this location. Recent studies have demonstrated that overexpression of miR-203 alters the expression of IL-6, a Th2 cytokine elevated in the plasma of EoE patients (6, 42, 48). Studies are needed to characterize the miR-203 target transcriptome and ascertain the pathophysiological consequences of reduced miR-203 in pediatric EoE. In addition, studies examining the modulation of esophageal miRNA expression by cytokines linked to EoE pathogenesis, including the Th2 cytokines IL-15 and IL-13, may provide valuable insight (20, 29).

Several miRNAs identified here as significantly altered in pediatric EoE have been associated with EoE. Of the 32 miRNAs found by T. X. Lu et al. (26) to be altered in EoE esophageal biopsies, 7 are among the 14 miRNAs identified by the profiling experiment performed here (Table 5). In addition, T. X. Lu et al. identified miR-106b*, the passenger strand miRNA of miR-106b, as upregulated in EoE. Subsequently, S. Lu et al. (24) measured 12 miRNAs, including miR-142-3p, miR-21, and miR-203, in esophageal biopsies obtained from pediatric EoE patients and healthy controls. miR-21 was increased and miR-203 was decreased in EoE, in accordance with the results presented here and by T. X. Lu et al. In contrast, S. Lu et al. found no difference in miR-142-3p levels between groups.

Table 5.

Summary of esophageal miRNA expression in EoE

| Previous Studies |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| T. X. Lu et al. (26) | S. Lu et al. (24) | Present Study | |

| Array comparison | aEoE (n = 10), HC (n = 8), iEoE (n = 6), CE (n = 5) | aEoE (n = 7), iEoE (n = 7) (longitudinal study) | aEoE (n = 5), HC (n = 6) |

| Platform | Life Technologies TaqMan array | Life Technologies TaqMan array | nanoString nCounter |

| aEoE vs. HC | Upregulated: miR-886-5p, miR-886-3p, miR-222*, miR-7, miR-29b, miR-642, miR-339-5p, miR-21, miR-21*, miR-142-5p, miR-146a, miR-146b, miR-142-3p, miR-132, miR-592, miR-92a-1*, miR-223*, miR-223, miR-801, miR-106b* | N/A | Upregulated: miR-223, miR-21, miR-142-3p, miR-142-5p, miR-29a, miR-20a, miR-221, miR-126, miR-106b, miR-15a |

| Downregulated: miR-375, miR-211, miR-210, miR-365, miR-203, miR-193a-5p, miR-193b, miR-193a-3p, let-7c, miR-144*, miR-30a-3p | Downregulated: miR-99a, miR-210, miR-203, miR-375 | ||

| aEoE vs. iEoE | Upregulated: miR-886-5p, miR-886-3p, miR-222*, miR-21, miR-21*, miR-142-5p, miR-146a, miR-146b, miR-142-3p, miR-132, miR-592, miR-223*, miR-223, miR-801, miR-106b* | Upregulated: miR-214, miR-146b-5p, miR-146a, miR-145, miR-142-3p, miR-21, miR-29b, miR-339-3p, miR-100, miR-10a, miR-223, miR-324-5p, miR-99a, miR-34a, miR-195, miR-125-5p, miR-140-5p, miR-502-3p, miR-150, miR-29a, miR-99b, miR-139-3p, miR-126, miR-342-3p, miR-181a, miR-93, miR-27a, miR-152, miR-27b, miR-152, miR-27b, miR-29c, miR-222, miR-155 | N/A |

| Downregulated: miR-375, miR-211, miR-210, miR-365, miR-203, miR-193a-5p, miR-193b, miR-193a-3p, let-7c, miR-144*, miR-30a-3p | Downregulated: miR-361-5p, miR-147, miR-203, miR-489 | ||

| Validation comparison | aEoE (n = 7–17), HC (n = 7–17) | aEoE (n = 8), HC (n = 10) | aEoE (n = 22), HC (n = 22), iEoE (n = 22), GERD (n = 6) |

| Platform | Life Technologies TaqMan RT-PCR | Life Technologies TaqMan RT-PCR | Life Technologies TaqMan RT-PCR |

| aEoE vs. HC | Upregulated: miR-21, miR-223 | Upregulated: miR-214, miR-146b-5p, miR-146a, miR-21 | Upregulated: miR-223, miR-21, miR-142-3p |

| Downregulated: miR-375, let-7c, miR-203 | Downregulated: miR-203, miR-489 | Downregulated: miR-203, miR-375 | |

| Age of aEoE subjects, yr | 9.3 (1.9–32.3) | 7.8 (1.3–16.0) | 10.8 (1.7–18.0) |

Age is presented as mean (range). aEoE, active EoE; HC, healthy controls; iEoE, inactive EoE; CE, chronic esophagitis; N/A, not applicable.

T. X. Lu et al. (26) reported that 27 of 32 esophageal miRNAs altered in active EoE were unaffected in patients with inactive disease. Similarly, all five of the miRNAs chosen for validation in the present case-control study were significantly altered between active and inactive EoE patients. In a longitudinal study, S. Lu et al. (24) profiled miRNAs in esophageal biopsies in EoE patients before and after corticosteroid treatment and found that 32 miRNAs were upregulated and 4 were downregulated following treatment (Table 5). However, no significant change in esophageal miR-375 or miR-21 was observed in the present longitudinal study of responding or nonresponding patients. This finding seemingly contradicts the longitudinal study by S. Lu et al. and the differential expression observed in the present case-control study and the study of T. X. Lu et al. The possibility remains that therapeutic intervention more rapidly alters intraepithelial eosinophil numbers than miRNA levels. A more thorough examination of temporal changes in esophageal miRNAs during treatment is necessary to address this issue.

Three miRNAs, miR-375, miR-21, and miR-223, were found to significantly correlate with peak eosinophils per hpf, consistent with the findings of T. X. Lu et al. (26). However, in contrast to the study of T. X. Lu et al., miR-203 and miR-142-3p levels in the present study did not correlate with eosinophils per hpf. The relationship between tissue miRNA and eosinophil counts presents the possibility for a novel diagnostic and surrogate biomarker, as tissue miRNA expression changes or miRNA release following injury can be reflected in the circulating miRNA pool (22, 32, 46). This corollary offers the possibility of a novel diagnostic and surrogate biomarker for EoE, for which invasive endoscopic testing is currently used for diagnosis and management. Indeed, T. X. Lu et al. identified an increase in miR-146a, miR-146b, and miR-223 in the plasma of EoE patients compared with healthy controls (26). In contrast, in the present experiments, no significant difference in serum miRNAs between the four sample groups was found. Although different starting materials and normalization techniques were used, these factors alone are unlikely to explain these contradictory findings. The need for reliable, noninvasive biomarkers of EoE warrants continued investigation of circulating miRNA in this patient population.

Several limitations to the current study should be considered. Because of the discontinuous nature of inflammation in EoE, disease activity may differ between biopsies used for histological observation and those processed for RNA analyses. This may in part explain the discrepancies between the present study and previous studies. In addition, sample sizes in the present study precluded subgroup analyses for lack of statistical power. miRNA changes identified in pediatric patients may not occur in the adult population; no reports have addressed miRNAs in adult EoE patients. Finally, newly discovered human miRNAs are not measured by the nCounter human version 1 platform; sequencing of esophageal miRNAs in EoE patients may identify additional disease-specific changes. Recent increases in EoE diagnoses in children warrant continued investigation of the role of miRNAs in the disease.

GRANTS

This study was funded in part by the American Partnership For Eosinophilic Disorders. A. M. Zahm is supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award for Individual Postdoctoral Fellows (F32).

DISCLOSURES

J. R. Friedman is currently employed at Janssen Research and Development.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

A.M.Z., C.M.-K., and J.R.F. are responsible for conception and design of the research; A.J.B. recruited the study subjects and managed specimen and clinical data collection and storage; A.M.Z., C.M.-K., D.M.T., C.L.L.G., and N.J.H. performed the experiments; A.M.Z., C.M.-K., and C.L.L.G. analyzed the data; A.M.Z., C.M.-K., D.M.T., C.L.L.G., and J.R.F. interpreted the results of the experiments; A.M.Z. prepared the figures; A.M.Z. and C.M.-K. drafted the manuscript; A.M.Z., C.M.-K., D.M.T., C.L.L.G., N.J.H., and J.R.F. approved the final version of the manuscript; C.M.-K., N.J.H., and J.R.F. edited and revised the manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the patients who generously gave their consent to participate in the study.

Current affiliation of C. Menard-Katcher: Department of Pediatrics at the University of Colorado School of Medicine and Gastrointestinal Eosinophil Disease Program at Children's Hospital Colorado.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abonia JP, Blanchard C, Butz BB, Rainey HF, Collins MH, Stringer K, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME. Involvement of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 126: 140–149, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen D, Fog JU, Biggs W, Salomon J, Dahslveen IK, Baker A, Mouritzen P. Improved microRNA quantification in total RNA from clinical samples. Methods 50: S6–S9, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhattacharya B, Carlsten J, Sabo E, Kethu S, Meitner P, Tavares R, Jakate S, Mangray S, Aswad B, Resnick MB. Increased expression of eotaxin-3 distinguishes between eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Hum Pathol 38: 1744–1753, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierbaum S, Nickel R, Zitnik S, Ahlert I, Lau S, Deichmann KA, Wahn U, Heinzmann A. Confirmation of association of IL-15 with pediatric asthma and comparison of different controls. Allergy 61: 576–580, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biton M, Levin A, Slyper M, Alkalay I, Horwitz E, Mor H, Kredo-Russo S, Avnit-Sagi T, Cojocaru G, Zreik F, Bentwich Z, Poy MN, Artis D, Walker MD, Hornstein E, Pikarsky E, Ben-Neriah Y. Epithelial microRNAs regulate gut mucosal immunity via epithelium-T cell crosstalk. Nat Immunol 12: 239–246, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blanchard C, Stucke EM, Rodriguez-Jimenez B, Burwinkel K, Collins MH, Ahrens A, Alexander ES, Butz BK, Jameson SC, Kaul A, Franciosi JP, Kushner JP, Putnam PE, Abonia JP, Rothenberg ME. A striking local esophageal cytokine expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol 127: 208–217, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blanchard C, Wang N, Stringer KF, Mishra A, Fulkerson PC, Abonia JP, Jameson SC, Kirby C, Konikoff MR, Collins MH, Cohen MB, Akers R, Hogan SP, Assa'ad AH, Putnam PE, Aronow BJ, Rothenberg ME. Eotaxin-3 and a uniquely conserved gene-expression profile in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest 116: 536–547, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen CZ, Li L, Lodish HF, Bartel DP. MicroRNAs modulate hematopoietic lineage differentiation. Science 303: 83–86, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 12: 589–596, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dweep H, Sticht C, Pandey P, Gretz N. miRWalk-database: prediction of possible miRNA binding sites by “walking” the genes of three genomes. J Biomed Inform 44: 839–847, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fassan M, Volinia S, Palatini J, Pizzi M, Baffa R, De Bernard M, Battaglia G, Parente P, Croce CM, Zaninotto G, Ancona E, Rugge M. MicroRNA expression profiling in human Barrett's carcinogenesis. Int J Cancer 129: 1661–1670, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frankel LB, Christoffersen NR, Jacobsen A, Lindow M, Krogh A, Lund AH. Programmed cell death 4 (PDCD4) is an important functional target of the microRNA miR-21 in breast cancer cells. J Biol Chem 283: 1026–1033, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Justinich C, Putnam PE, Bonis P, Hassall E, Straumann A, Rothenberg ME. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. Gastroenterology 133: 1342–1363, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gabriely G, Wurdinger T, Kesari S, Esau CC, Burchard J, Linsley PS, Krichevsky AM. MicroRNA 21 promotes glioma invasion by targeting matrix metalloproteinase regulators. Mol Cell Biol 28: 5369–5380, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Griffiths-Jones S. The microRNA registry. Nucleic Acids Res 32: D109–D111, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hand NJ, Horner AM, Master ZR, Boateng LA, LeGuen C, Uvaydova M, Friedman JR. MicroRNA profiling identifies miR-29 as a regulator of disease-associated pathways in experimental biliary atresia. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 54: 186–192, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hellemans J, Mortier G, De Paepe A, Speleman F, Vandesompele J. qBase relative quantification framework and software for management and automated analysis of real-time quantitative PCR data. Genome Biol 8: R19, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.John B, Enright AJ, Aravin A, Tuschl T, Sander C, Marks DS. Human microRNA targets. PLoS Biol 2: e363, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jurkin J, Schichl YM, Koeffel R, Bauer T, Richter S, Konradi S, Gesslbauer B, Strobl H. miR-146a is differentially expressed by myeloid dendritic cell subsets and desensitizes cells to TLR2-dependent activation. J Immunol 184: 4955–4965, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kottyan LC, Davis BP, Sherrill JD, Liu K, Rochman M, Kaufman K, Weirauch MT, Vaughn S, Lazaro S, Rupert AM, Kohram M, Stucke EM, Kemme KA, Magnusen A, He H, Dexheimer P, Chehade M, Wood RA, Pesek RD, Vickery BP, Fleischer DM, Lindbad R, Sampson HA, Mukkada VA, Putnam PE, Abonia JP, Martin LJ, Harley JB, Rothenberg ME. Genome-wide association analysis of eosinophilic esophagitis provides insight into the tissue specificity of this allergic disease. Nat Genet 46: 895–900, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Landgraf P, Rusu M, Sheridan R, Sewer A, Iovino N, Aravin A, Pfeffer S, Rice A, Kamphorst AO, Landthaler M, Lin C, Socci ND, Hermida L, Fulci V, Chiaretti S, Foa R, Schliwka J, Fuchs U, Novosel A, Muller RU, Schermer B, Bissels U, Inman J, Phan Q, Chien M, Weir DB, Choksi R, De Vita G, Frezzetti D, Trompeter HI, Hornung V, Teng G, Hartmann G, Palkovits M, Di Lauro R, Wernet P, Macino G, Rogler CE, Nagle JW, Ju J, Papavasiliou FN, Benzing T, Lichter P, Tam W, Brownstein MJ, Bosio A, Borkhardt A, Russo JJ, Sander C, Zavolan M, Tuschl T. A mammalian microRNA expression atlas based on small RNA library sequencing. Cell 129: 1401–1414, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laterza OF, Lim L, Garrett-Engele PW, Vlasakova K, Muniappa N, Tanaka WK, Johnson JM, Sina JF, Fare TL, Sistare FD, Glaab WE. Plasma microRNAs as sensitive and specific biomarkers of tissue injury. Clin Chem 55: 1977–1983, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, Burks AW, Chehade M, Collins MH, Dellon ES, Dohil R, Falk GW, Gonsalves N, Gupta SK, Katzka DA, Lucendo AJ, Markowitz JE, Noel RJ, Odze RD, Putnam PE, Richter JE, Romero Y, Ruchelli E, Sampson HA, Schoepfer A, Shaheen NJ, Sicherer SH, Spechler S, Spergel JM, Straumann A, Wershil BK, Rothenberg ME, Aceves SS. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol 128: 3–20, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lu S, Mukkada VA, Mangray S, Cleveland K, Shillingford N, Schorl C, Brodsky AS, Resnick MB. MicroRNA profiling in mucosal biopsies of eosinophilic esophagitis patients pre and post treatment with steroids and relationship with mRNA targets. PLos One 7: e40676, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lu TX, Lim EJ, Itskovich S, Besse JA, Plassard AJ, Mingler MK, Rothenberg JA, Fulkerson PC, Aronow BJ, Rothenberg ME. Targeted ablation of miR-21 decreases murine eosinophil progenitor cell growth. PLos One 8: e59397, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lu TX, Sherrill JD, Wen T, Plassard AJ, Besse JA, Abonia JP, Franciosi JP, Putnam PE, Eby M, Martin LJ, Aronow BJ, Rothenberg ME. MicroRNA signature in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis, reversibility with glucocorticoids, and assessment as disease biomarkers. J Allergy Clin Immunol 129: 1064–1075, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y, Xiao J, Lin H, Bai Y, Luo X, Wang Z, Yang B. A single anti-microRNA antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotide (AMO) targeting multiple microRNAs offers an improved approach for microRNA interference. Nucleic Acids Res 37: e24, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McKenna LB, Schug J, Vourekas A, McKenna JB, Bramswig NC, Friedman JR, Kaestner KH. MicroRNAs control intestinal epithelial differentiation, architecture, and barrier function. Gastroenterology 139: 1654–1664, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mishra A, Rothenberg ME. Intratracheal IL-13 induces eosinophilic esophagitis by an IL-5, eotaxin-1, and STAT6-dependent mechanism. Gastroenterology 125: 1419–1427, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell PS, Parkin RK, Kroh EM, Fritz BR, Wyman SK, Pogosova-Agadjanyan EL, Peterson A, Noteboom J, O'Briant KC, Allen A, Lin DW, Urban N, Drescher CW, Knudsen BS, Stirewalt DL, Gentleman R, Vessella RL, Nelson PS, Martin DB, Tewari M. Circulating microRNAs as stable blood-based markers for cancer detection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 105: 10513–10518, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nenci A, Becker C, Wullaert A, Gareus R, van Loo G, Danese S, Huth M, Nikolaev A, Neufert C, Madison B, Gumucio D, Neurath MF, Pasparakis M. Epithelial NEMO links innate immunity to chronic intestinal inflammation. Nature 446: 557–561, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ng EK, Chong WW, Jin H, Lam EK, Shin VY, Yu J, Poon TC, Ng SS, Sung JJ. Differential expression of microRNAs in plasma of patients with colorectal cancer: a potential marker for colorectal cancer screening. Gut 58: 1375–1381, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Noti M, Wojno ED, Kim BS, Siracusa MC, Giacomin PR, Nair MG, Benitez AJ, Ruymann KR, Muir AB, Hill DA, Chikwava KR, Moghaddam AE, Sattentau QJ, Alex A, Zhou C, Yearley JH, Menard-Katcher P, Kubo M, Obata-Ninomiya K, Karasuyama H, Comeau MR, Brown-Whitehorn T, de Waal Malefyt R, Sleiman PM, Hakonarson H, Cianferoni A, Falk GW, Wang ML, Spergel JM, Artis D. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Med 19: 1005–1013, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Connell RM, Chaudhuri AA, Rao DS, Baltimore D. Inositol phosphatase SHIP1 is a primary target of miR-155. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 7113–7118, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavlidis P, Noble WS. Matrix2png: a utility for visualizing matrix data. Bioinformatics 19: 295–296, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Primo MN, Bak RO, Schibler B, Mikkelsen JG. Regulation of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNFα and IL24 by microRNA-203 in primary keratinocytes. Cytokine 60: 741–748, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimoldi M, Chieppa M, Salucci V, Avogadri F, Sonzogni A, Sampietro GM, Nespoli A, Viale G, Allavena P, Rescigno M. Intestinal immune homeostasis is regulated by the crosstalk between epithelial cells and dendritic cells. Nat Immunol 6: 507–514, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, Gober L, Kim C, Glessner J, Frackelton E, Thomas K, Blanchard C, Liacouras C, Verma R, Aceves S, Collins MH, Brown-Whitehorn T, Putnam PE, Franciosi JP, Chiavacci RM, Grant SF, Abonia JP, Sleiman PM, Hakonarson H. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet 42: 289–291, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruckert R, Asadullah K, Seifert M, Budagian VM, Arnold R, Trombotto C, Paus R, Bulfone-Paus S. Inhibition of keratinocyte apoptosis by IL-15: a new parameter in the pathogenesis of psoriasis? J Immunol 165: 2240–2250, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ruckert R, Brandt K, Braun A, Hoymann HG, Herz U, Budagian V, Durkop H, Renz H, Bulfone-Paus S. Blocking IL-15 prevents the induction of allergen-specific T cells and allergic inflammation in vivo. J Immunol 174: 5507–5515, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shin KJ, Wall EA, Zavzavadjian JR, Santat LA, Liu J, Hwang JI, Rebres R, Roach T, Seaman W, Simon MI, Fraser ID. A single lentiviral vector platform for microRNA-based conditional RNA interference and coordinated transgene expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103: 13759–13764, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stanczyk J, Ospelt C, Karouzakis E, Filer A, Raza K, Kolling C, Gay R, Buckley CD, Tak PP, Gay S, Kyburz D. Altered expression of microRNA-203 in rheumatoid arthritis synovial fibroblasts and its role in fibroblast activation. Arthritis Rheum 63: 373–381, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tantibhaedhyangkul U, Tatevian N, Gilger MA, Major AM, Davis CM. Increased esophageal regulatory T cells and eosinophil characteristics in children with eosinophilic esophagitis and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann Clin Lab Sci 39: 99–107, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tusher VG, Tibshirani R, Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 98: 5116–5121, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vicario M, Blanchard C, Stringer KF, Collins MH, Mingler MK, Ahrens A, Putnam PE, Abonia JP, Santos J, Rothenberg ME. Local B cells and IgE production in the oesophageal mucosa in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Gut 59: 12–20, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang K, Zhang S, Marzolf B, Troisch P, Brightman A, Hu Z, Hood LE, Galas DJ. Circulating microRNAs, potential biomarkers for drug-induced liver injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 4402–4407, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang P, Hou J, Lin L, Wang C, Liu X, Li D, Ma F, Wang Z, Cao X. Inducible microRNA-155 feedback promotes type I IFN signaling in antiviral innate immunity by targeting suppressor of cytokine signaling 1. J Immunol 185: 6226–6233, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wei J, Huang X, Zhang Z, Jia W, Zhao Z, Zhang Y, Liu X, Xu G. MyD88 as a target of microRNA-203 in regulation of lipopolysaccharide or Bacille Calmette-Guerin induced inflammatory response of macrophage RAW264.7 cells. Mol Immunol 55: 303–309, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu H, Neilson JR, Kumar P, Manocha M, Shankar P, Sharp PA, Manjunath N. miRNA profiling of naive, effector and memory CD8 T cells. PLos One 2: e1020, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Xie J, Ameres SL, Friedline R, Hung JH, Zhang Y, Xie Q, Zhong L, Su Q, He R, Li M, Li H, Mu X, Zhang H, Broderick JA, Kim JK, Weng Z, Flotte TR, Zamore PD, Gao G. Long-term, efficient inhibition of microRNA function in mice using rAAV vectors. Nat Methods 9: 403–409, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang H, Gu J, Wang KK, Zhang W, Xing J, Chen Z, Ajani JA, Wu X. MicroRNA expression signatures in Barrett's esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 15: 5744–5752, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yang JJ, Cheng C, Yang W, Pei D, Cao X, Fan Y, Pounds SB, Neale G, Trevino LR, French D, Campana D, Downing JR, Evans WE, Pui CH, Devidas M, Bowman WP, Camitta BM, Willman CL, Davies SM, Borowitz MJ, Carroll WL, Hunger SP, Relling MV. Genome-wide interrogation of germline genetic variation associated with treatment response in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. JAMA 301: 393–403, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zahm AM, Hand NJ, Tsoucas DM, Le Guen CL, Baldassano RN, Friedman JR. Rectal microRNAs are perturbed in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease of the colon. J Crohns Colitis 8: 1108–1117, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zaph C, Troy AE, Taylor BC, Berman-Booty LD, Guild KJ, Du Y, Yost EA, Gruber AD, May MJ, Greten FR, Eckmann L, Karin M, Artis D. Epithelial-cell-intrinsic IKKβ expression regulates intestinal immune homeostasis. Nature 446: 552–556, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang XJ, Yan KL, Wang ZM, Yang S, Zhang GL, Fan X, Xiao FL, Gao M, Cui Y, Wang PG, Sun LD, Zhang KY, Wang B, Wang DZ, Xu SJ, Huang W, Liu JJ. Polymorphisms in interleukin-15 gene on chromosome 4q31.2 are associated with psoriasis vulgaris in Chinese population. J Invest Dermatol 127: 2544–2551, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhu L, Yan W, Rodriguez-Canales J, Rosenberg AM, Hu N, Goldstein AM, Taylor PR, Erickson HS, Emmert-Buck MR, Tangrea MA. MicroRNA analysis of microdissected normal squamous esophageal epithelium and tumor cells. Am J Cancer Res 1: 574–584, 2011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu X, Wang M, Mavi P, Rayapudi M, Pandey AK, Kaul A, Putnam PE, Rothenberg ME, Mishra A. Interleukin-15 expression is increased in human eosinophilic esophagitis and mediates pathogenesis in mice. Gastroenterology 139: 182–193, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]