Abstract

Decomposition of soil organic matter (SOM) is sensitive to vegetation and climate change. Here, we investigated the influence of changes in forest types on the mineralization of soil carbon (C) and nitrogen (N), and their temperature sensitivity (Q10) and coupling relationships by using a laboratory soil incubation experiments. We sampled soils from four forest types, namely, a primary Quercus liaotungensis forest (QL), Larix principis-rupprechtii plantation (LP), Pinus tabulaeformis plantation (PT), and secondary shrub forest (SS) in temperate northern China. The results showed that soil C and N mineralization differed significantly among forest types. Soil C and N mineralization were closely coupled in all plots, and C:N ratios of mineralized SOM ranged from 2.54 to 4.12. Forest type significantly influenced the Q10 values of soil C and N mineralization. The activation energy (Ea) of soil C and N mineralization was negatively related to the SOM quality index in all forest types. The reverse relationships suggested that the carbon quality-temperature (CQT) hypothesis was simultaneously applicable to soil C and N mineralization. Our findings show that the coupled relationships of soil C and N mineralization can be affected by vegetation change.

Soil organic matter (SOM) is a major terrestrial pool for soil organic carbon (C) and nitrogen (N). Soil C mineralization is the process in which soil organic C is mineralized by microbial decomposers to inorganic C, resulting in CO2 emissions. Similarly, soil N mineralization is the process in which soil organic N is mineralized to inorganic forms (mainly NH4+ and NO3−) by microbial decomposition which provide the available N for plant growth1,2. Soil C and N mineralization is a central process in SOM decomposition, and has a critical influence on the structure and function of terrestrial ecosystems3,4; soil C and N cycles are closely coupled5,6. SOM decomposition rates increase with increasing temperature, which is commonly expressed as an exponential function7,8. Under global warming scenarios, increasing temperature may accelerate SOM decomposition and consequently release more CO2 from soil to the atmosphere and create a positive feedback to warming9. An alternative scenario is that increased SOM decomposition rates would result in more soil N being available for vegetation growth, which may enhance CO2 uptake by plants and offset, to some extent, the CO2 generated from SOM decomposition and even create a negative feedback6,10. Therefore the different C:N ratios of C and N mineralization in SOM decomposition would regulate soil available N supply and influence plant growth and production; they would also be key factors that affect the C budget in terrestrial ecosystems11,12. The issue would become more complicated because of the variation in soil properties and new SOM input due to changes in vegetation types. The intrinsic relationship of the soil C and N mineralization process is still unclear, although some studies have reported a soil C and N coupling cycle5,13. It is therefore important to understand how vegetation changes influence coupled soil C and N mineralization, and whether the availability of these nutrients may be varied by changes in mineralization processes.

The average global atmospheric temperature is predicted to increase by at least 2°C by the end of the 21st century14. Many studies have investigated the response of SOM decomposition to changes in temperature, which is commonly expressed as temperature sensitivity (Q10) and represent the ratio of SOM decomposition rates at one temperature to a temperature 10°C lower7,8. To date, some studies have shown that Q10 values varied according to spatial scale and vegetation type15,16. Because of the lack of measured Q10 values for different ecosystems or land-use types, most models of C and N cycling assigned Q10 a constant value of approximately 217,18, which has resulted in uncertainty in estimating and predicting the effect of climate change on terrestrial ecosystems.

SOM decomposition involves a series of biochemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes with different Q10 values that are produced by microorganisms; temperature has a strong influence on microorganisms and enzyme production and activity19. The carbon quality-temperature (CQT) hypothesis, based on the principles of thermodynamics and enzyme kinetics, has been proposed to explain SOM decomposition and substrate quality. This hypothesis assumes that the decomposition of lower-quality substrates with recalcitrant molecular structure requires higher activation energy (Ea) and thus has a greater Q10 value20,21. However, whether the hypothesis is simultaneously applicable to both soil microbial C and N mineralization especially for different vegetation types has not been experimentally verified, although it have been proved for soil C mineralization22,23 or N mineralization19 alone. Soil C and N mineralization processes have accelerated under global climate change, and changes in Q10 values may affect SOM composition and have strong effects on the C budget of terrestrial nutrient cycling ecosystems. Understanding the changes in Q10 of C and N mineralization in different vegetation types is therefore essential for predicting SOM decomposition under warming scenarios17,18.

To clarify the effects of vegetation changes on soil C and N mineralization, we selected four forest types that are widely distributed in temperate northern China and represent different types of vegetation changes. We performed a laboratory soil incubation experiment under different temperature conditions. The main objectives of this study were to (1) investigate the influence of forest type on soil C and N mineralization and their coupled relationships, (2) explore the influence of forest type on the Q10 of SOM decomposition, and (3) verify the assumption that the CQT hypothesis applies to not only C mineralization but also N mineralization simultaneously.

Results

Soil properties

Changes in forest types had a significant influence on soil pH, SOM content, and total N in soil (Table 1). Moreover, the C:N ratio of soil and litter varied among different forest types and were in the order: PT > LP > QL > SS. The C:N ratio of litter especially differed significantly in all forest types (P < 0.05).

Table 1. Basic characteristics of the experimental plots.

| Forest type | Dominant species | Location | Altitude (m a.s.l.) | pH | Soil organic matter (%) | Soil total nitrogen (%) | C/N ratio of soil | C/N ratio of litter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quercus liaotungensis (QL) | Quercus liaotungensis, Acer mono | 39°57′32.20″N115°25′26.33″E | 1318 | 6.90 ± 0.47b | 6.92 ± 0.71 b | 0.30 ± 0.03 b | 13.11 ± 0.68 ab | 47.65 ± 0.73 c |

| Larix principis-rupprechtii plantation (LP) | L. principis-rupprechtii, Q. liaotungensis, Ulmus davidiana | 39°57′34.30″N115°25′49.92″E | 1302 | 7.05 ± 0.18ab | 10.36 ± 1.61a | 0.46 ± 0.07 a | 13.54 ± 1.42 ab | 51.53 ± 0.66 b |

| Pinus tabulaeformis plantation (PT) | P. tabulaeformis, Q. liaotungensis, U. davidiana | 39°58′11.09″N115°25′52.06″E | 1278 | 6.58 ± 0.49 b | 6.90 ± 0.81 b | 0.30 ± 0.05 b | 13.73 ± 1.73 a | 82.85 ± 2.62 a |

| Secondary shrub forest (SS) | Spiraea pubescens Deutzia grandiflora | 39°57′48.93″N115°26′28.01″E | 1265 | 7.44 ± 0.01 a | 5.97 ± 0.12 b | 0.29 ± 0.04 b | 11.61 ± 1.30 b | 28.58 ± 0.27 d |

Data are represented as means ± 1 SD (n = 4). The same superscript letters within each column indicate no significant difference among forest types at the P < 0.05 level (ANOVA).

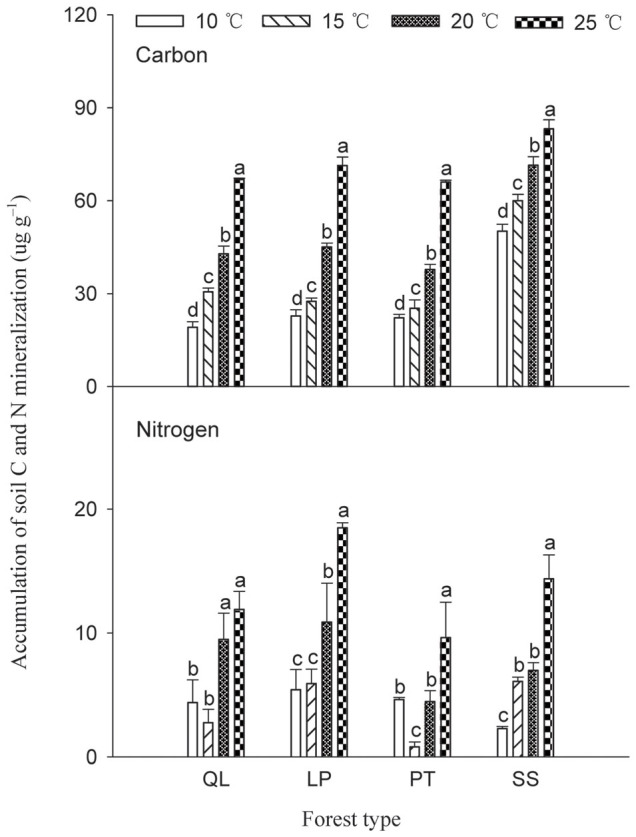

Soil C and N mineralization

Cumulative soil C mineralization differed significantly among four forest types (P < 0.0001, Table 2) and was the highest in SS, followed (in decreasing order) by LP, QL and PT (Figure 1). Incubation temperature also had a significant positive effect on soil C mineralization (P < 0.0001), and there was a significant interactive effect of forest type and temperature on soil C mineralization (P < 0.0001; Table 2). Both forest type and incubation temperature had significant effects on soil N mineralization (P < 0.0001), with apparent interactive effects (P < 0.0001; Table 2). Cumulative soil N mineralized in all temperature treatments was the highest in LP, followed by SS, QL and PT (Figure 1).

Table 2. Influence of forest type and incubation temperature on soil C and N mineralization.

| C mineralization | N mineralization | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | P | F | P | |

| Forest type (FT) | 710.83 | <0.0001 | 30.922 | <0.0001 |

| Temperature (T) | 1452.387 | <0.0001 | 134.224 | <0.0001 |

| FT × T | 18.855 | <0.0001 | 6.511 | <0.0001 |

Figure 1. Influence of incubation temperature on cumulative soil C and N mineralization according to forest type.

QL, Q. liaotungensis; LP, L. principis-rupprechtii; PT, P. tabulaeformis; SS, secondary shrub forest. Same letters within a forest type indicate no significant differences (P < 0.05).

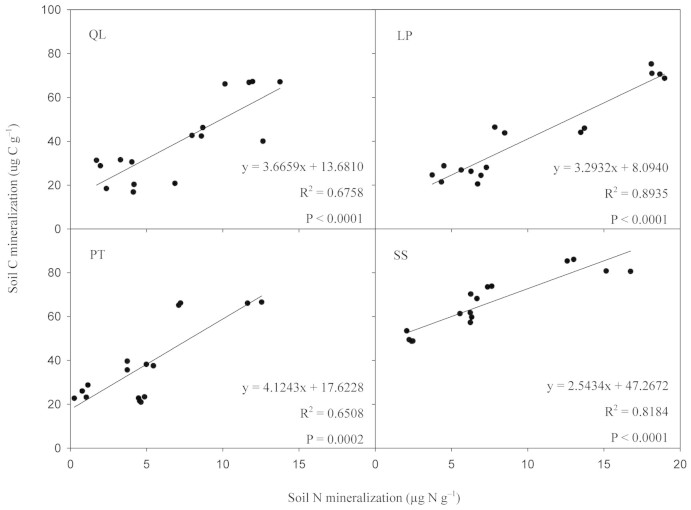

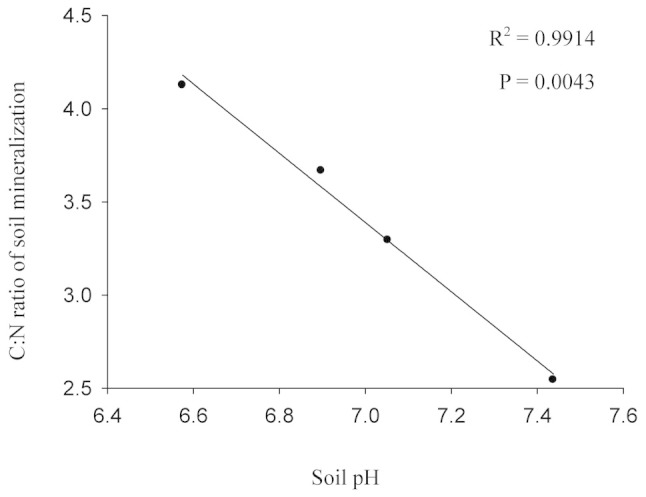

Coupling of soil C and N mineralization

Soil C and N mineralization were closely coupled, as seen in the C:N ratio of decomposed SOM in all forest types (P < 0.0001; Figure 2). The C:N ratios of decomposed SOM were 3.67, 3.29, 4.12 and 2.54 in the QL, LP, TP, and SS plots, respectively. There was a significant positive linear correlation between soil C and N mineralization and a relatively stable C:N ratio under different forest types. In addition, the C:N ratios of SOM decomposition showed a significant negative correlation with soil pH (R2 = 0.99, P = 0.0043; Figure 3), but was not related to soil C and N content or soil C:N ratio.

Figure 2. Correlation between soil C and N mineralization under different forest types.

QL, Q. liaotungensis; LP, L. principis-rupprechtii; PT, P. tabulaeformis; SS, secondary shrub forest.

Figure 3. Relationship between C:N ratio of soil mineralization and soil pH for all forest types.

Influence of forest type on the Q10 of SOM decomposition

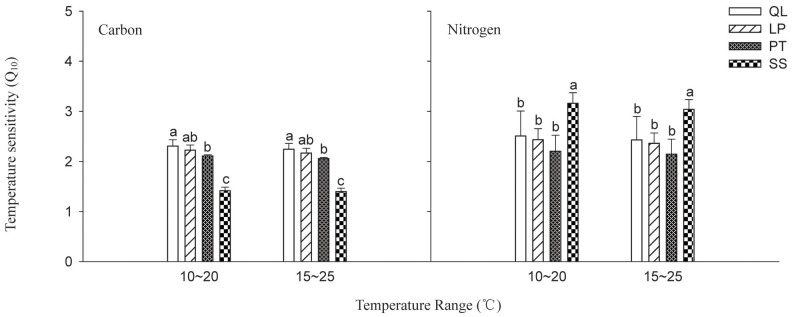

Forest type changes significantly influenced the Q10 values of soil C mineralization (F = 167.63, P < 0.0001). The Q10 value varied from 1.40 to 2.31, depending on temperature and was the highest in QL, followed by LP, PT, and SS (Figure 4). The Q10 value of soil N mineralization (2.14–3.16) also significantly differed among forest types (F = 12.13, P < 0.0001) in descending order as SS > QL > LP > PT (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Effects of forest type on the temperature sensitivity (Q10) of soil C and N mineralization.

Q10 was calculated using the Arrhenius equation (Eqs. 8 and 9). QL, Q. liaotungensis; LP, L. principis-rupprechtii; PT, P. tabulaeformis; SS, secondary shrub forest. Same letters within a forest type indicate no significant differences(P < 0.05).

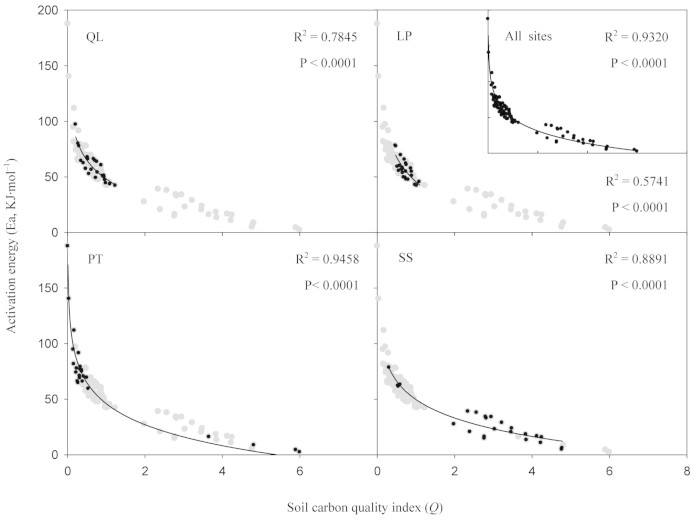

CQT hypothesis in relation to soil microbial C and N mineralization

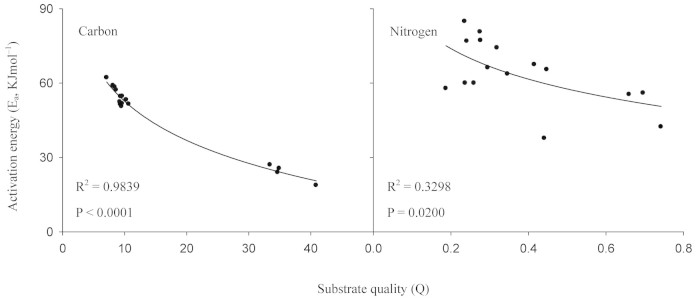

Ea of SOM decomposition significantly decreased with the increasing quality index of SOM (Q)(R2 = 0.98, P < 0.0001 for soil C mineralization; R2 = 0.36, P = 0.0145 for soil N mineralization; Figure 5). Logarithmic equations can well fit the negative relationships between Ea and Q (Figure 5). Additionally, the Ea values of soil C mineralization logarithmically decreased with the increasing Q index in all plots (R2 = 0.78, P < 0.0001 for QL; R2 = 0.57, P < 0.0001 for LP; R2 = 0.95, P < 0.0001 for PT; R2 = 0.89, P < 0.0001 for SS; Figure 6). Therefore, the CQT hypothesis of SOM decomposition is applicable to both soil microbial C and N mineralization in different forest types.

Figure 5. Relationship between activation energy (Ea) of C and N mineralization and soil substrate quality index (Q).

Fitted equation: Ea = a + b × ln(Q). Ea represents activation energy; a and b are coefficients; Q represents soil substrate quality index, calculated from Eq. 10.

Figure 6. Changes in the relationships between activation energy (Ea) and soil carbon quality index (Q) in different forest types.

Fitted equation: Ea = a + b × ln(Q). Ea represents activation energy; a and b are coefficients; Q represents soil substrate quality index, calculated from Eq. 10. QL, Q. liaotungensis; LP, L. principis-rupprechtii; PT, P. tabulaeformis; SS, secondary shrub forest.

Discussion

Forest type has substantial impact on soil C and N mineralization. In forest ecosystems, litter can be the major source of SOM, and changes in dominant plants species can affect the quality and quantity of litter input, SOM decomposition process, and nutrient cycling24,25,26,27. Agren et al.28 found that the stoichiometry of C and N exerted a strong interaction on litter decomposition and showed large scale variations in different regions. In our results, the C:N ratio of litter was significantly different in the four forests and was positively correlated with the C:N of SOM to some extent. Thus, forest type can influence litter quality, soil biochemical properties28,29, SOM quality30, and microbial community structure31, all of which can influence SOM decomposition. In addition, habitat changes have complex effects on SOM decomposition by affecting soil temperature, moisture, nutrient availability, and microbial community32,33,34. Ouyang et al.35 reported that soil C and N mineralization increases with the successional stage. Soil C and N mineralization was significantly higher in natural forests than in pine forest plantations. Wu et al.36 suggested that soil C mineralization would be the highest in a secondary forest and lowest in a plantation.

Both soil microbial C and N mineralization increased significantly with increasing temperature in all forest types. As global warming progresses, increased surface temperatures will promote SOM decomposition. Accelerated decomposition rates will result in greater quantities of CO2 being emitted into the atmosphere, thus exacerbating the greenhouseeffect9. However, higher availability of soil N and other nutrients due to SOM decomposition can facilitate photosynthesis and growth, leading to enhanced sequestration of atmospheric CO26,10. Primary productivity in many terrestrial ecosystems is limited by available N in the soil, so the ratio of available C to N will directly influence the response of vegetation to climate change4; this highlights the importance of soil C:N mineralization ratios under changing climate conditions.

Our findings demonstrated the coupling effects of soil C and N mineralization in SOM decomposition and revealed that forest type can influence this coupled relationship in view of the mineralized C:N ratios. The variation in soil mineralized C:N ratios could be attributed primarily to the differences in litter and root content, and microbial community composition among the vegetation types30. The relationships between soil C and N mineralization in different forest types were closely related to soil pH, which influenced the composition of soil microorganism31. Although the C:N ratios of mineralization differed among forest types, the mineralized C:N ratio was relatively stable within a given forest. The mechanisms that control the coupling relationship of soil C and N mineralization need to be studied further. In our study, the mineralized N was calculated by the different values of soil inorganic N (NH4+-N + NO3−-N) before and at the end of the incubation experiment, which represented the soil net N mineralization. Calculation methods that do not account for soil N immobilization in the incubation process would show some uncertainties. In practice, some reasons promote us to select the methods. First, net N mineralization in the soil should include the total effects of mineralization and immobilization. However, the immobilized N can be re-mineralized, which is an integral part of the mineralization-immobilization turnover; it is therefore very difficult to accurately estimate the mineralization and remobilization rates37,38. Secondly, according to Koch et al.19 and Wang et al.39, soil N immobilization may not be a major N flux during the short incubation period. Therefore, most studies calculated net N mineralization in the soil as the amount of N released from the indigenous organic N pool, not including immobilized N4,26,40,41,42. Theoretically, C:N ratio of soil C and N mineralization could be equal to C:N ratio of SOM, so we supposed that immobilization should explain to some extent the difference of C:N between SOM and soil C and N mineralization in different forest types40. However, changes in SOM properties and microbial N utilization strategies should play more important roles in determining the different ratios of soil C and N mineralization. The underlying mechanisms for above assumption need to study in the future.

Forest type significantly influence the Q10 of soil C and N mineralization. Here, the Q10 values of soil C and N mineralization varied from 1.40 to 2.31 and from 2.14 to 3.16, respectively. Koch et al.19 reported Q10 values for soil C and N decomposition as 1.5–2.7 and 1.3–2.8, respectively. A meta-analysis by Raich and Schlesinger43 demonstrated that the Q10 values of SOM decomposition ranged from 1.3 to 3.3 worldwide. Changes in the vegetation altered plant species composition and litter quality26, thus influencing soil C:N ratios and microbial community composition29,30,44, all these factors affect SOM decomposition and temperature sensitivity. He et al.45 demonstrated that high N:C ratios in added substrates enhanced SOM decomposition rates and temperature sensitivity.

We found that the highest Q10 values for C mineralization in QL plots and the highest Q10 values for N mineralization in SS plots. The findings suggested that decomposition in natural forests would be more sensitive to global warming than that in artificial plantations. However, most biogeochemical models still consider Q10 as a constant of about 217,18, which leads to large uncertainty in estimating soil C and N cycling at regional and global scales. Understanding the effects of vegetation change on Q10 is critical for accurately predicting the responses of terrestrial ecosystems to climate change.

The CQT hypothesis is applicable to both soil C mineralization and N mineralization simultaneously. The principles of enzyme kinetics suggest that the energy required for SOM decomposition is correlated with substrate quality22. The higher Ea associated with the breakdown of recalcitrant substrates should result in a greater Q10, which provided the foundation of CQT hypothesis20. Craine et al.21 used 28 soils from Alaska to Puerto Rico and demonstrated that the Ea decreased with soil C mineralization rates at 20°C. Scientists defined the SOM quality by mineralization rate and verified the CQT hypothesis, where they assumed that the high quality substrate is easy to decompose and thus has higher mineralization rates. Moreover, Hartley and Ineson46 found that the Q10 of soil respiration increased significantly with incubation time, and they assumed that substrate recalcitrance increased with the depletion of the labile soil organic C pool and supported the hypothesis. Xu et al.47 showed that Q10 values increased with increasing soil depth, which corresponded to a decrease in labile C and increase in recalcitrant C with depth48. Similarly, other studies have verified the CQT hypothesis by distinguishing the high and low C quality subjectively23,49,50. In practice, it is difficult to evaluate the changes in labile and recalcitrant SOM because soil compounds are composed of several discrete pools with different lability51 and exhibit a wide range of kinetic properties52. To avoid the above mentioned problems, we used a classic exponential equation to calculate the SOM quality index19,50 and directly link it to the activation energy to verify the CQT hypothesis for both soil microbial C and N mineralization.

Our results showed that activation energy decreased significantly with increasing C and N quality, which was well illustrated by logarithmic equations for all forest types (Figure 5 and 6). The findings presented here indicate that the CQT hypothesis applies to not only soil C but also soil N mineralization simultaneously and is independent on forest type. Our findings provide new insights for the applicability of the CQT hypothesis and suggest new avenues for research on the decomposition of other elements and their biochemical cycles. On the basis of these results and the underlying enzyme kinetics, we assumed that the mineralization of other elements in SOM, such as P or S, may also comply with the CQT hypothesis; however, this requires further study.

Methods

Study area

Large expanses of a primary forest dominated by Quercus liaotungensis in temperate northern China have been degraded to secondary mixed conifer and broadleaved forests and many secondary shrubs as a result of anthropogenic activity over the last century. Besides, plantations of Larix principis-rupprechtii and Pinus tabulaeformis have increased since the 1950s with the implementation of restoration programs in the region.

The Dongling Mountains are located west of Beijing (39°55′–40°05′N, 115°20′–115°35′E) at an average elevation of approximately 1330 m. This region has a temperate continental monsoon climate with a mean annual temperature and precipitation of 11°Cand639 mm. The soils are classified as forest brown and cinnamon soils, which are rich in organic matter53. We selected four experimental plots, namely, a primary Q. liaotungensis forest (QL), L. principis-rupprechtii plantation (LP), P. Tabulaeformis plantation (PT), and secondary shrub forest (SS), respectively. These four forest types are widely distributed in northern China. The experimental plots are distributed within the same upper basalt platform and have similar primary vegetation but different disturbance history (Table 1).

Soil sampling

Soil sampling was conducted in early August 2013. We randomly established four plots (30 m × 40 m) in each forest type and collected 15–20 surface soil samples (0–10 cm) in each plot by using a5-cm-diameter soil auger. The soil samples were sieved (<2 mm), and roots and visible organic debris were removed by hand. Approximately 100 g of each soil sample was air-dried for analysis of chemical properties, and the remaining soil was stored at 4°C.

Chemical analyses

The C concentration in soil and litter (%) was measured using a modified Mebius method54. The N concentration of soil and litter (%) was measured with a modified Kjeldahl wet-digestion procedure55, using a 2300 Kjeltec Analyzer Unit (FOSS, Sweden). Soil pH was measured in a soil-water slurry (1:2.5, w/w) with an Ultrameter-2 pH meter (Myron L. Company, California, USA). Soil water-holding capacity (WHC, %) and gravimetric moisture content (%) were measured at the Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing45.

Incubation experiment

The incubation experiment was conducted using soils from the four forest types (QL, LP, PT, and SS) in the middle of August 2013. First, 40-g samples of fresh soil were placed in incubation bottles and adjusted to 60% WHC, which is considered optimal for microbial activity. All samples were maintained for 1 week at 15°C to avoid the pulse of mineralization. After that, the samples were incubated for 2 weeks at the four treatment temperatures (10, 15, 20, and 25°C) with four replications in incubators with constant temperature and 85% humidity. The soil moisture of the incubated samples was adjusted at 3-d intervals on a weight basis.

Soil C mineralization

Rates of soil C mineralization were measured on the basis of the soil respiration rates six times on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 10, and 14 by using an automatic system described by He et al.45 (Figure. S1). The system consisted of a Li-7000 analyzer, an electric water bath to control incubation temperature, an air-flow controller, soda-lime equipment to control the initial CO2 concentration, an auto-sampler on a turn-plate, automatic transformation valves to control the sample bottle, and a data collector. In practice, the system first automatically lowered the CO2 concentration by using a bypass system of soda lime and then recorded the changes in CO2 concentration as it steadily increased. Rates of soil C mineralization were calculated from the slope of CO2 concentration and specific transformation factors as follows:

|

where CMR is the soil respiration rate (μg C g−1 h−1); K is the slope of CO2 concentration; V is the volume of the incubation bottle and gas tube; m is soil dry weight; α is the transformation coefficient of CO2 mass, and β is the transformation coefficient of time.

Accumulation of mineralized soil C was calculated as:

|

where CM is the cumulative soil C mineralized; ti is the time of measurement; and CMRi is the soil C mineralization rate at ti.

Soil net N mineralization

Soil N mineralization is the process that soil organic N be mineralized into inorganic forms (NH4+-N + NO3−-N), however, at the same time, the mineralized inorganic N can be immobilized into organic forms, thus soil net N mineralization is the net balance between N mineralization and N immobilization. As N immobilization is an integral part of the mineralization-immobilization turnover, moreover the immobilized N can be re-mineralized, it is hard to distinguish the two processes and accurately estimate the mineralization and remobilization rates. Besides, the immobilization is lower during the turnover, therefore we use soil N mineralization in the paper to represent soil net N mineralization as as many related manuscripts. The samples for measuring soil N mineralization were incubated for 2 weeks, and the experiment was conducted simultaneously with that for soil C mineralization. In brief, 40 g of soil samples were mixed with 100 ml of 0.5 M K2SO4 solution and shocked for 1 h; after the N minerals were extracted and filtered, concentrations of ammonium (NH4+-N) and nitrate (NO3−-N) were analyzed using a flow injection autoanalyzer (FUTURA, Alliance Instruments, France)before and at the end of the experiment. Soil N mineralization was calculated by the different values of the inorganic N (NH4+-N + NO3−-N) contents in the soil before and after incubation. The soil N mineralization rate and accumulation were expressed as:

|

|

|

|

|

where ti and ti+1 are the initial and ending time for the incubation, respectively; Δt is the duration of the incubation; c[NH4+-N]t and c[NH4+-N]t+1 are the concentrations of NH4+-N before and after incubation, respectively; c[NO3−-N]t and c[NO3−-N]t+1 are the concentrations of NO3−-N before and after incubation, respectively; L is the volume of solution leached; Aamm, Anit, and NM are the cumulative NH4+-N, NO3−N, and total N mineralized, respectively; and NMR is the N mineralization rate.

Statistical analysis

We calculated the activation energy (Ea) and temperature sensitivity (Q10) of soil C mineralization on the basis of the Arrhenius equation:

|

where A is a pre-exponential parameter; R is the gas constant (8.314 J mol−1); and T is temperature in Kelvin (K).

Eq. (8) was used to calculated Ea and Q10 as follows:

|

where T1 and T2 are temperatures in K and give the 10-K temperature range for the corresponding Q10 (i.e., T2 = T1 + 10).

The carbon quality (Q) of SOM was calculated as:

|

where Q is the carbon quality index of SOM (the exponential constant or activity at 0°C; b is the exponential parameter of the equation; and T is temperature (°C). The Ea and Q10 values for soil N mineralization and the N quality of SOM were similarly calculated using Eqs. 8–10.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS v. 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Univariate analysis was used to explore the effects of forest type and temperature on soil C and N mineralization and their temperature sensitivity. Differences in soil C and N mineralization according to temperatures and differences in Q10 among different forest types were examined using one-way ANOVA with a significance level of P < 0.05. Regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationships between soil C and N mineralization; C:N ratio of soil mineralized; and soil pH, Ea, and substrate quality. The regression equations assessed the values of R2, P value, as well as the Akaike information criterion.

Author Contributions

Q.Q. and C.W. analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. N.H. and Z.Z. supervised the project and commented on the contents of the manuscript. Q.Q., Q.W. and J.X. collected the datasets and conducted the data pre-processing. X.W. and H.S. revised and edited the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the State Key Basic Research Development Program [2010CB833501], the Environmental Public Welfare Scientific Research Project [201209028], the Natural Science Foundation of China (31290221), and the Kezhen Distinguished Talents in Institute of Geographic Sciences and Natural Resources Research, CAS (2013RC102).

References

- Manzoni S. & Porporato A. Soil carbon and nitrogen mineralization: Theory and models across scales. Soil Biol Biochem 41, 1355–1379 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Xia J. Y., Niu S. L. & Wan S. Q. Response of ecosystem carbon exchange to warming and nitrogen addition during two hydrologically contrasting growing seasons in a temperate steppe. Global Change Biol 15, 1544–1556 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- Vourlitis G. L. & Zorba G. Nitrogen and carbon mineralization of semi-arid shrubland soil exposed to long-term atmospheric nitrogen deposition. Biol Fert Soils 43, 611–615 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub M. N. & Schimel J. P. Interactions between carbon and nitrogen mineralization and soil organic matter chemistry in arctic tundra soils. Ecosystems 6, 129–14 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- Gardenas A. I. et al. Knowledge gaps in soil carbon and nitrogen interactions - From molecular to global scale. Soil Biol Biochem 43, 702–717 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Sokolov A. P. et al. Consequences of considering carbon-nitrogen interactions on the feedbacks between climate and the terrestrial carbon cycle. J Climate 21, 3776–3796 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Hamdi S., Moyano F., Sall S., Bernoux M. & Chevallier T. Synthesis analysis of the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration from laboratory studies in relation to incubation methods and soil conditions. Soil Biol Biochem 58, 115–126 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Wang X. G., Zhua B., Gao M. R., Wang Y. Q. & Zheng X. H. Seasonal variations in soil respiration and temperature sensitivity under three land-use types in hilly areas of the Sichuan Basin. Aust J Soil Res 46, 727–734 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Post W. M. Report of a workshop on climate feedbacks and the role of peatlands, tundra, and boreal ecosystems in the global carbon cycle. ORNL/TM-11457 (Oak Ridge Natn Lab., Oak Ridge Tennessee, 1990).

- McGuire A. D. et al. Interactions between carbon and nitrogen dynamics in estimating net primary productivity for potential vegetation in North America. Global Biogeochem Cy 6, 101–124 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty S. et al. Carbon and nitrogen mineralization kinetics in soil of rice-rice system under long term application of chemical fertilizers and farmyard manure. Eur J Soil Biol 58, 113–121 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Wardle D. A. et al. Ecological linkages between aboveground and belowground biota. Science 304, 1629–1633 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaehle S. Terrestrial nitrogen - carbon cycle interactions at the global scale. Philos T R Soc B 368, 10.1098/rstb.2013.0125 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stocker T. F. et al. IPCC, 2013: Climate Change 2013:. The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change: CambridgeUnivPress, Cambridge, United Kingdom and NewYork, NY, USA (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Janssens I., Carrara A. & Ceulemans R. Annual Q10 of soil respiration reflects plant phenological patterns as well as temperature sensitivity. Global Change Biol 10, 161–169 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Reichstein M., Bednorz F., Broll G. & Kätterer T. Temperature dependence of carbon mineralisation: conclusions from a long-term incubation of subalpine soil samples. Soil Biol Biochem 32, 947–958 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Qi Y., Xu M. & Wu J. G. Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration and its effects on ecosystem carbon budget: nonlinearity begets surprises. Ecol Model 153, 131–142 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Schimel D. et al. Contribution of increasing CO2 and climate to carbon storage by ecosystems in the United States. Science 287, 2004–2006 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch O., Tscherko D. & Kandeler E. Temperature sensitivity of microbial respiration, nitrogen mineralization, and potential soil enzyme activities in organic alpine soils. Global Biogeochem Cy 21, 10.1029/2007gb002983 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- Conant R. T. et al. Experimental warming shows that decomposition temperature sensitivity increases with soil organic matter recalcitrance. Ecology 89, 2384–2391 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craine J. M., Fierer N. & McLauchlan K. K. Widespread coupling between the rate and temperature sensitivity of organic matter decay. Nat Geosci 3, 854–857 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Bosatta E. & Agren G. I. Soil organic matter quality interpreted thermodynamically. Soil Biol Biochem 31, 1889–1891 (1999). [Google Scholar]

- Haddix M. L. et al. The Role of Soil Characteristics on Temperature Sensitivity of Soil Organic Matter. Soil Sci Soc Am J 75, 56–68 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Gill R. A. & Burke I. C. Ecosystem consequences of plant life form changes at three sites in the semiarid United States. Oecologia 121, 551–563 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser B., Turrion M. B., Solomon D., Ni A. & Zech W. Soil organic matter quantity and quality in mountain soils of the Alay Range, Kyrgyzia, affected by land use change. Biol Fert Soils 31, 407–413 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Sun S. H., Liu J. J. & Chang S. X. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon and nitrogen mineralization: impacts of nitrogen species and land use type. Plant Soil 372, 597–608 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Vargas D. N., Bertiller M. B., Ares J. O., Carrera A. L. & Sain C. L. Soil C and N dynamics induced by leaf-litter decomposition of shrubs and perennial grasses of the Patagonian Monte. Soil Biol Biochem 38, 2401–2410 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Agren G. I., Hyvonen R., Berglund S. L. & Hobbie S. E. Estimating the critical N:C from litter decomposition data and its relation to soil organic matter stoichiometry. Soil Biol Biochem 67, 312–318 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- Bauhus J., Pare D. & Cote L. Effects of tree species, stand age and soil type on soil microbial biomass and its activity in a southern boreal forest. Soil Biol Biochem 30, 1077–1089 (1998). [Google Scholar]

- Lovett G. M., Weathers K. C. & Arthur M. A. Control of nitrogen loss from forested watersheds by soil carbon: Nitrogen ratio and tree species composition. Ecosystems 5, 712–718 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- Hogberg M. N., Hogberg P. & Myrold D. D. Is microbial community composition in boreal forest soils determined by pH, C-to-N ratio, the trees, or all three? Oecologia 150, 590–601 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conant R. T. et al. Temperature and soil organic matter decomposition rates - synthesis of current knowledge and a way forward. Global Change Biol 17, 3392–3404 (2011). [Google Scholar]

- Cusack D. F., Torn M. S., McDowell W. H. & Silver W. L. The response of heterotrophic activity and carbon cycling to nitrogen additions and warming in two tropical soils. Global Change Biol 16, 2555–2572 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Hobbie S. E., Schimel J. P., Trumbore S. E. & Randerson J. R. Controls over carbon storage and turnover in high-latitude soils. Global Change Biol 6, 196–210 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang X. J. et al. Soil organic carbon and nitrogen mineralization along a forest successional gradient in Southern China. Chin J Appl Ecol 18, 1688–1694 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. G., Zhang X. Q. & Xu D. Y. The mineralization of soil organic carbon under different land use in the LiuPan mountain forest zone. Acta Phytoecol Sin 28, 530–538 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- Barraclough D. N−15 isotope dilution techniques to study soil nitrogen transformations and plant uptake. Fert Res 42, 185–192 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. A., Hart S. C., Shanks C. A. & Firestone M. K. Measuring gross nitrogen mineralization, immobilization, and nitrification by N−15 isotopic pool dilution in intact soil cores. J Soil Sci 42, 335–349 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- Wang W. J., Chalk P. M., Chen D. & Smith C. J. Nitrogen mineralisation, immobilisation and loss, and their role in determining differences in net nitrogen production during waterlogged and aerobic incubation of soils. Soil Biol Biochem 33, 1305–1315 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- Cote L., Brown S., Pare D., Fyles J. & Bauhus J. Dynamics of carbon acid nitrogen mineralization in relation to stand type, stand age and soil texture in the boreal mixedwood. Soil Biol Biochem 32, 1079–1090 (2000). [Google Scholar]

- Matus F. J., Lusk C. H. & Maire C. R. Effects of soil texture, carbon input rates, and litter quality on free organic matter and nitrogen mineralization in Chilean rain forest and agricultural soils. Commun Soil Sci Plan 39, 187–201 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Turan M. et al. Temperature sensitivity of soil respiration is affected by nitrogen fertilization and land use. Acta Agr Scand B-S P 60, 427–436 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Raich J. W. & Schlesinger W. H. The global carbon-dioxide flux in soil respiration and its relationship to vegetation and climate. Tellus B 44, 81–99 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- Priha O., Grayston S. J., Hiukka R., Pennanen T. & Smolander A. Microbial community structure and characteristics of the organic matter in soils under Pinus sylvestris, Picea abies and Betula pendula at two forest sites. Biol Fert Soils 33, 17–24 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- He N. P. et al. Changes in the temperature sensitivity of SOM decomposition with grassland succession: implications for soil C sequestration. Ecol Evol 3, 5045–5054 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartley I. P. & Ineson P. Substrate quality and the temperature sensitivity of soil organic matter decomposition. Soil Biol Biochem 40, 1567–1574 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Zhou Y., Ruan H. H., Luo Y. Q. & Wang J. S. Temperature sensitivity increases with soil organic carbon recalcitrance along an elevational gradient in the Wuyi Mountains, China. Soil Biol Biochem 42, 1811–1815 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Fang C. M., Smith P., Moncrieff J. B. & Smith J. U. Similar response of labile and resistant soil organic matter pools to changes in temperature. Nature 433, 57–59 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wetterstedt J. A. M., Persson T. & Agren G. I. Temperature sensitivity and substrate quality in soil organic matter decomposition: results of an incubation study with three substrates. Global Change Biol 16, 1806–1819 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- Xu X., Luo Y. Q. & Zhou J. Z. Carbon quality and the temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon decomposition in a tallgrass prairie. Soil Biol Biochem 50, 142–148 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- Smith P. et al. A comparison of the performance of nine soil organic matter models using datasets from seven long-term experiments. Geoderma 81, 153–225 (1997). [Google Scholar]

- Davidson E. A. & Janssens I. A. Temperature sensitivity of soil carbon decomposition and feedbacks to climate change. Nature 440, 165–173 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou J. H., Mi X. C., Liu C. R. & Ma K. P. Tree competition and species coexistence in a Quercus-Betula forest in the Dongling Mountains in northern China. Acta Oecol 30, 117–125 (2006). [Google Scholar]

- Nelson D. W. & Sommers L. E. Total carbon, organic carbon, and organic matter. Page, A. L., Miller, R. H. & Keeney, D. R., editors. In: Methods of soil analysis. American Society of Agronomy and Soil Science Society of American, Madison, Wisconsin, USA (1982). [Google Scholar]

- Gallaher R. N., Weldon C. O. & Boswell F. C. A semiautomated procedure for total nitrogen in plant and soil samples. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 40, 887–889 (1976). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information