The authors report the results of a large cohort of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) patients receiving afatinib within a compassionate-use program (CUP) after reversible EGFR-TKI failure. Acknowledging the constraints of data collection in a CUP, afatinib appears to be safe and to confer some clinical benefit in this population.

Keywords: Afatinib, Non-small cell lung cancer, Epidermal growth factor receptor, Gefitinib, Erlotinib

Abstract

Background.

Afatinib, an irreversible ErbB family blocker, demonstrated superiority to chemotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with EGFR-mutated non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). Afatinib is also active in patients progressing on EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs). We report the results of a large cohort of NSCLC patients receiving afatinib within a compassionate-use program (CUP).

Patients and Methods.

Patients with advanced NSCLC progressing after one line or more of chemotherapy and one line or more of EGFR-TKI treatment with either an EGFR mutation or documented clinical benefit were enrolled. Data collection was not monitored or verified by central review. The intention of this CUP was to provide controlled preregistration access to afatinib for patients with life-threatening diseases and no other treatment option.

Results.

From May 2010 to October 2013, 573 patients (65% female; median age: 64 years [range: 28–89 years]) were enrolled, with strong participation of community oncologists. Comorbidities were allowed, including second malignancies in 11% of patients. EGFR mutation status was available in 391 patients (72%), and 83% tested mutation positive. Median time to treatment failure (TTF) of 541 patients treated with afatinib was 3.7 months (range: 0.0 to >29.0 months). Median TTF was 4.0 and 2.7 months in patients with adenocarcinomas and squamous cell carcinomas, respectively, and 4.6 months in patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC. Adverse events were generally manageable.

Conclusion.

Afatinib was able to be given in a real-world setting to heavily pretreated patients with EGFR-mutated or EGFR-TKI-sensitive NSCLC. Acknowledging the constraints of data collection in a CUP, afatinib appears to be safe and to confer some clinical benefit in this population.

Implications for Practice:

This analysis of a large cohort of patients treated mainly in the community oncology setting confirms the activity of afatinib, an irreversible ErbB family blocker, in heavily pretreated metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. In particular, patients with tumors harboring somatic EGFR mutations derive a clinical meaningful benefit from afatinib, despite progressing on prior treatments with reversible EGFR inhibitors gefitinib or erlotinib. In some patients receiving multiple EGFR-targeting lines, the second and third lines provided prolonged disease control. Maintaining ErbB blockade by afatinib is an attractive strategy in EGFR-dependent lung cancer with acquired resistance to gefitinib or erlotinib.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cancer fatality, with an annual death toll of at least 1.4 million persons on a global scale [1]. The majority of lung cancers are histologically grouped as non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC), with pulmonary adenocarcinoma evolving as the predominating subtype. Recently, morphology-based classification of lung cancer has been complemented by additional parameters to better discriminate distinct lung cancer biologies and corresponding clinical entities. Comprehensive genomic analyses of NSCLC have revealed multiple subgroups that are characterized by recurring somatic gene aberrations [2–4]. This has been paralleled by the development of pharmacotherapies to specifically treat biologically defined tumors. Somatic mutations of the gene encoding the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), in particular those clustering in EGFR exons 19 and 21, result in the expression of a structurally altered receptor with oncogenic properties. Lung cancers expressing mutant EGFR depend on its oncogenic signal and thus are exquisitely sensitive to reversible ATP-competitive inhibitors of the EGFR tyrosine kinase [5, 6]. Several prospective randomized clinical trials in patients with metastatic EGFR-mutated NSCLC have proven that reversible EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (EGFR-TKIs) gefitinib and erlotinib are more effective than platinum-based chemotherapy in terms of response rate, progression-free survival, and patient-reported outcomes [7–10]. Despite their impressive activity, EGFR-TKIs provide only transient disease control, with acquisition of gatekeeper mutations of the drug target and activation of surrogate signaling pathways being the main causes of treatment failure [11]. Pharmacologic strategies to improve treatment of EGFR-dependent cancers include the development of more potent and covalently binding inhibitors and mutation-specific inhibitors [12–14]. Afatinib, an irreversible ErbB family blocker, has shown preclinical activity in cancer models resistant to EGFR-TKIs. Based on the LUX-Lung 3 trial, afatinib has recently gained approval for treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutated NSCLC [15, 16]. Afatinib has also demonstrated activity in NSCLC patients progressing after pretreatment with reversible EGFR-TKIs gefitinib or erlotinib [17, 18]. This suggests a distinct or clinically more potent mechanism of action of afatinib on lung cancers depending on mutant EGFR. It is now established that, next to pivotal clinical trials, additional sources of information are required to better value the safety and clinical utility of a novel drug. This is particularly important in oncology because newly registered anticancer agents will very likely be prescribed in settings and for clinical indications that do not always comply with the strict guidance and inclusion and exclusion criteria of a pivotal clinical trial. To this end, we analyzed a comprehensive clinical database including 541 patients with heavily pretreated NSCLC who were treated with afatinib in the German compassionate-use program (CUP) for afatinib.

Methods

Compassionate-Use Program

The afatinib CUP was initiated by Boehringer Ingelheim GmbH (Ingelheim, Germany, http://www.boehringer-ingelheim.com) in May 2010 after public reporting of the results of the LUX-Lung 1 trial [17, 19]. Patients with advanced NSCLC who were ineligible to participate in one of the actively accruing afatinib phase III trials were offered afatinib treatment within the CUP. Key inclusion criteria were failure of at least one line of cytotoxic chemotherapy and disease progression after clinical benefit from erlotinib or gefitinib. Clinical benefit was defined as complete or partial response or stable disease for at least 6 months [20]. Alternatively, somatic mutations of EGFR or HER2 had to be documented. Additional inclusion criteria comprised age ≥18 years, absence of an established treatment option, and written informed consent. Afatinib was given as continuous oral treatment at a starting dose of 50 mg/day. Lower starting doses of 40 mg or 30 mg were allowed at the discretion of the treating physician. Dose modifications (10-mg steps, maximum dose 50 mg/day) and de-escalations (10-mg steps, minimum dose 30 mg/day) were allowed. One treatment cycle was defined as 30 days. The protocol was approved by the responsible ethics committee (Medical Board of the State Rhineland-Palatine, 837.105.10[7114]), and the required regulatory authorities (Federal Institute for Drugs and Medical Devices and regional authorities) were informed. As required by law, the CUP was stopped with market availability of afatinib (Gilotrif/Giotrif; Boehringer Ingelheim).

Clinical Database

Participating physicians were asked to report a pseudonymized clinical data set for each patient including sex, age, comorbidities, disease stage, prior therapies, and EGFR mutation status to control CUP eligibility criteria. Reporting of adverse events, including tumor progression, was mandatory.

Statistical Analyses

Patient demographics were analyzed descriptively. Time to treatment failure (TTF) was defined as time from start of afatinib treatment to the end of treatment for any cause. If the exact start date was not reported, it was set as 7 days after shipment of afatinib to the site. If the end date was not reported, it was set as the day of the last drug order. The clinical database was locked on December 31, 2013. Patients remaining on treatment (n = 95) were censored. Survival curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method for TTF and overall survival. A Cox proportional hazards model was applied to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The significance level was set at p < .05. Patients receiving less than 2 months of afatinib before stopping due to progressive disease or death were classified as “progressive disease” as best response. Patients receiving afatinib for more than 4 months were classified as “stable disease” as best response if not reported differently. Analyses were undertaken using MedCalc version 12.1.4.0 (MedCalc Software bvba, Ostend, Belgium, http://www.medcalc.org).

Results

Patient Characteristics and Pretreatments

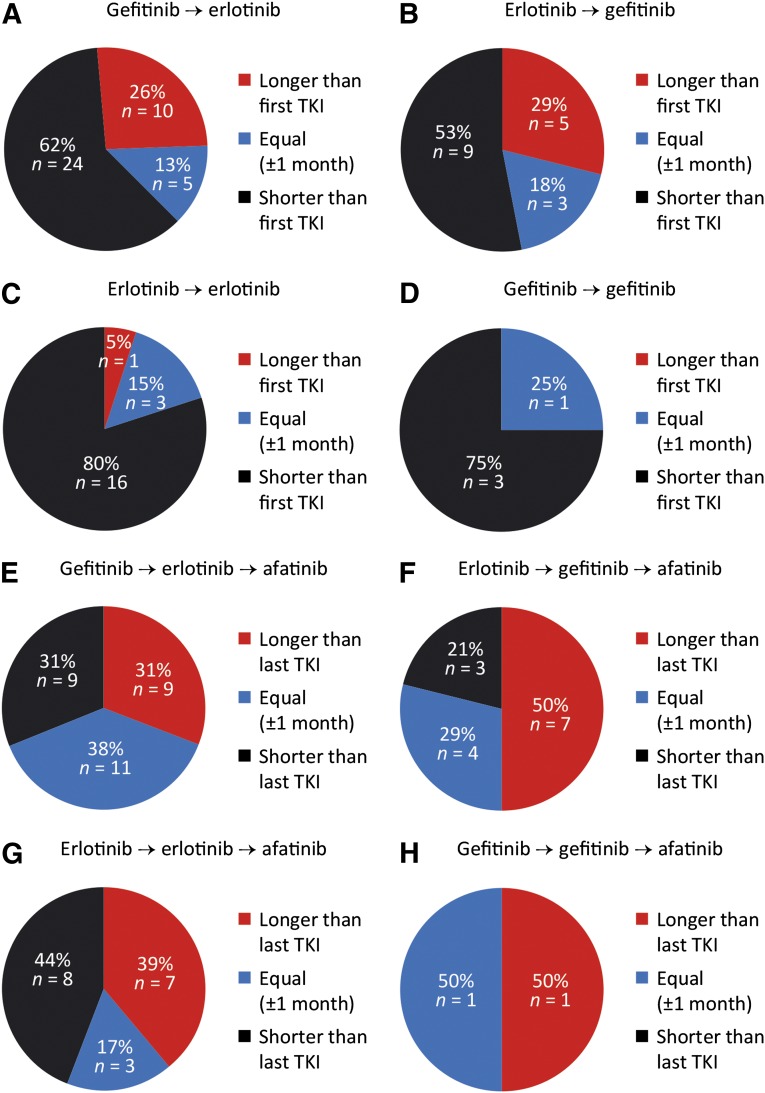

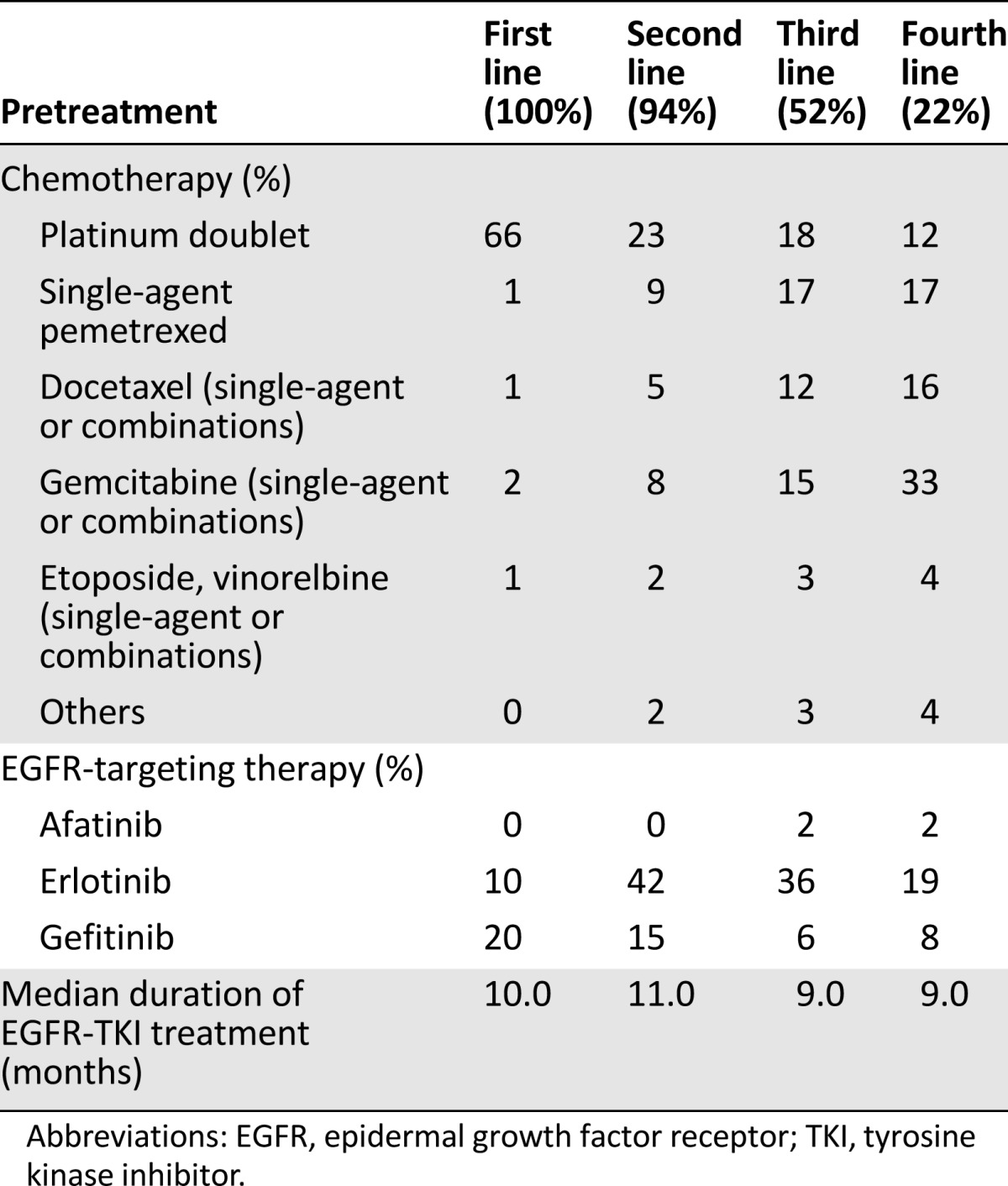

In total, 573 patients (65% female; median age: 64 years [range: 28–89 years]) (Table 1) from 118 sites (27 university hospitals, 64 hospitals, 27 oncology practices) (supplemental online Table 1) were registered in the CUP between May 2010 and October 2013. The majority of patients (92%) had pulmonary adenocarcinomas, and 11% of patients had a history of one other malignancy or more (Table 1). Median time from primary diagnosis of lung cancer to enrollment in the CUP was 27.2 months. Due to rapid disease deterioration, 32 patients received no afatinib treatment, resulting in 541 evaluable patients. The most frequently applied first-line treatments included platinum doublets (66%) or EGFR-TKIs (30%). The most abundant second-line treatments were an EGFR-TKI (56%) or chemotherapy (42%). Third-line treatments comprised single-agent chemotherapy (pemetrexed 17%, gemcitabine 15%, docetaxel 12%) or an EGFR-TKI (42%). The majority of patients were enrolled in the CUP for third- or fourth-line treatment, but individual patients with up to 12 prior treatment lines were registered. A group of 31 patients (6%) with documented contraindications for chemotherapy were enrolled after failure of first-line gefitinib or erlotinib treatment. Median duration of prior EGFR-TKI therapy was 10 months in first-line treatment, 11 months in second-line treatment, and 10 months in third-line treatment. Seven patients had been pretreated with afatinib within controlled clinical trials (Table 2).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

Table 2.

Pretreatments

EGFR Mutation Testing

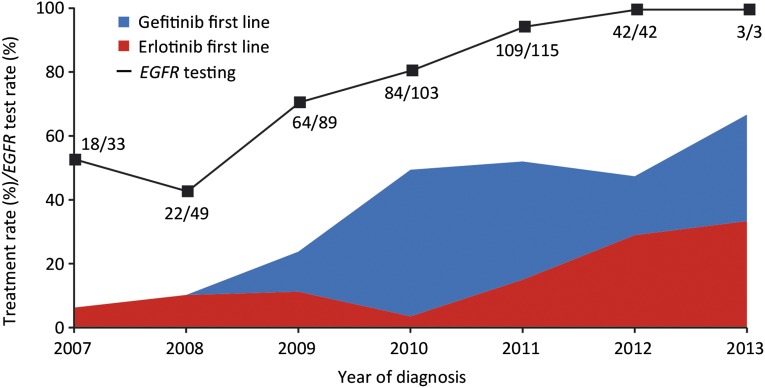

Documentation of EGFR mutation status from local testing using assay methodology accepted by the German Society of Pathology was available for 391 patients (72%). Of those, 327 patients (83%) tested EGFR mutation positive, and 63 patients had EGFR wild-type tumors. The majority of EGFR aberrations were common mutations (in-frame deletion at EGFR exon 19, point mutation at EGFR exon 21 leading to L858R amino acid substitution). EGFR testing rates were highest in oncology practices and university hospitals (>70%) (supplemental online Table 1). Interestingly, the lowest rates for EGFR testing were reported from lung hospitals, five of which were specialized lung cancer centers certified by the German Cancer Society. The use of EGFR mutation testing increased over time. In patients registered in 2011 or later, EGFR mutation status was known in 95% of cases. Still, only 51% of those patients received an EGFR-TKI as first-line treatment (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Fraction of patients with first-line treatment with gefitinib or erlotinib (patients with EGFR-mutated cancer) and overall rate of EGFR testing. The actual numbers of tested patients and patients diagnosed per year are also given.

Abbreviation: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Efficacy of Afatinib Treatment

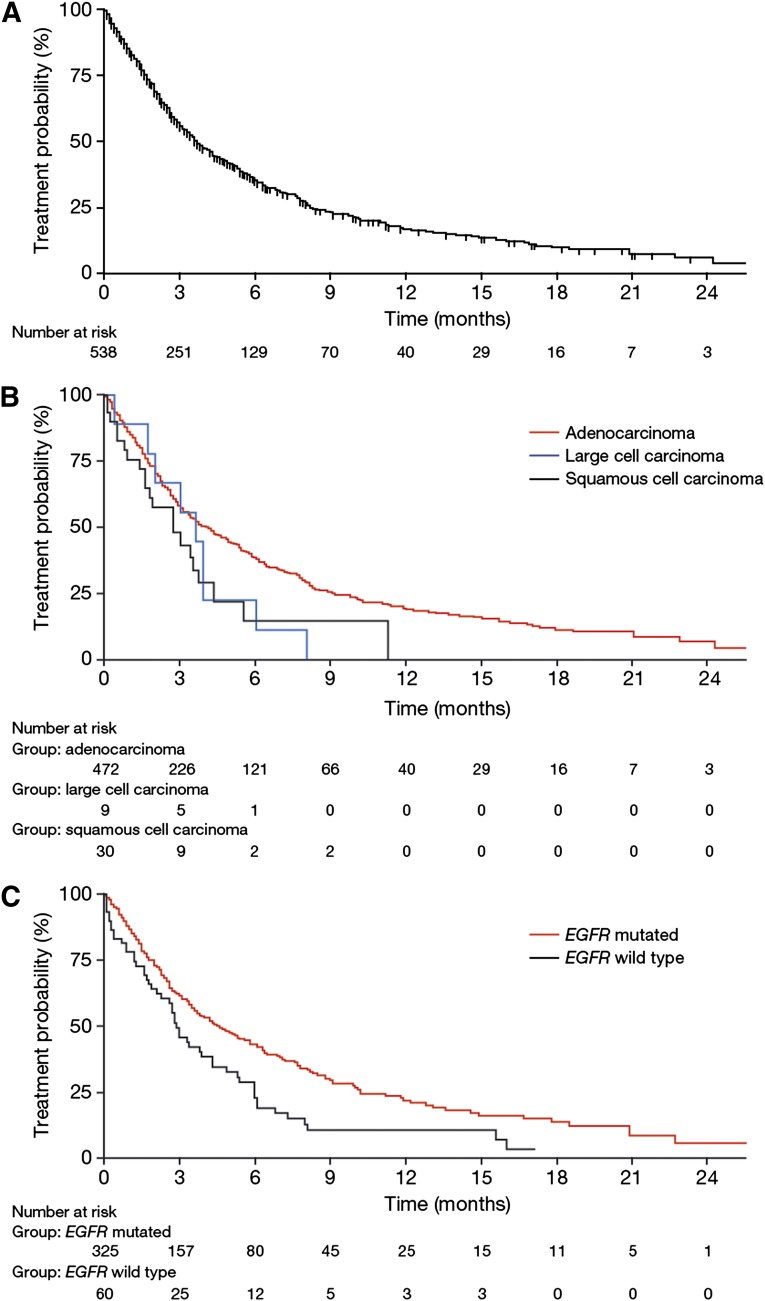

The majority of patients (74%) were registered in the CUP for third- or fourth-line treatment with afatinib. Clinical efficacy of afatinib was determined by calculating the TTF for each patient. Median TTF for the entire population was 3.7 months (range: 0.0 to ongoing at 29.0 months) (Fig. 2A). Median survival of the cohort was 16.0 months (range: 0.0 to ongoing at 29.0 months). However, follow-up reports after progression on afatinib were not mandatory, and death was reported in only 23% of patients. Hence, overall survival data from the CUP are less robust than TTF results.

Figure 2.

Time to treatment failure with afatinib for the entire cohort (A), in relation to lung cancer histology (B), and in relation to EGFR mutational status (C).

Abbreviation: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor.

Patients with adenocarcinoma exhibited a median TTF of 4.0 months, which was comparable to patients with large cell carcinomas (3.6 months) but numerically longer than in patients with squamous cell carcinomas (2.7 months) (Fig. 2B). Differences in number of prior treatment lines could not explain the longer median TTF in patients with adenocarcinoma (median prior treatment lines: 3 [range: 1–12 lines]) than squamous cell carcinoma (median prior treatment lines: 3 [range: 2–6 lines]). Median TTF in patients with documented EGFR-mutated NSCLC was 4.6 months (range: 0.0 to ongoing at 27.7 months) compared with 2.9 months (range: 0.1 to ongoing at 17.1 months) in patients with EGFR wild-type lung cancers (HR: 0.63; 95% CI: 0.44–0.90; p = .0024) (Fig. 2C).

Data regarding best response, as described in the patients’ routine radiology reports, were retrieved for 193 patients; a further 164 patients were classified with progressive disease as best response or stable disease by applying the described criteria (end of treatment due to progression or death within 2 months or receiving treatment for more than 4 months, respectively). In addition, 15% (n = 52) had a partial or mixed response, 55% (n = 196) had stable disease, and 31% (n = 109) had progressive disease as best response.

Safety and Tolerability

Reported adverse events of any grade included diarrhea (29%), skin or mucosal toxicity (31%), nausea or vomiting (6%), and fatigue (5%). Serious adverse events were reported in 79 patients (15%), two of which were fatal (one case of diarrhea and one case of renal failure). One case of life-threatening supraventricular tachycardia was reported. Afatinib treatment was discontinued in 59 patients (13%) due to side effects (supplemental online Table 2). The majority of treatment discontinuations (61%) occurred in cycle 1 or 2. Dose reductions were attempted in only 4 of these patients (7%). The most important reasons for permanent treatment discontinuation were disease progression (51%), death (19%), and loss to follow-up (17%). At the time of closure of the CUP due to market availability of afatinib, 28% of patients were still on active treatment.

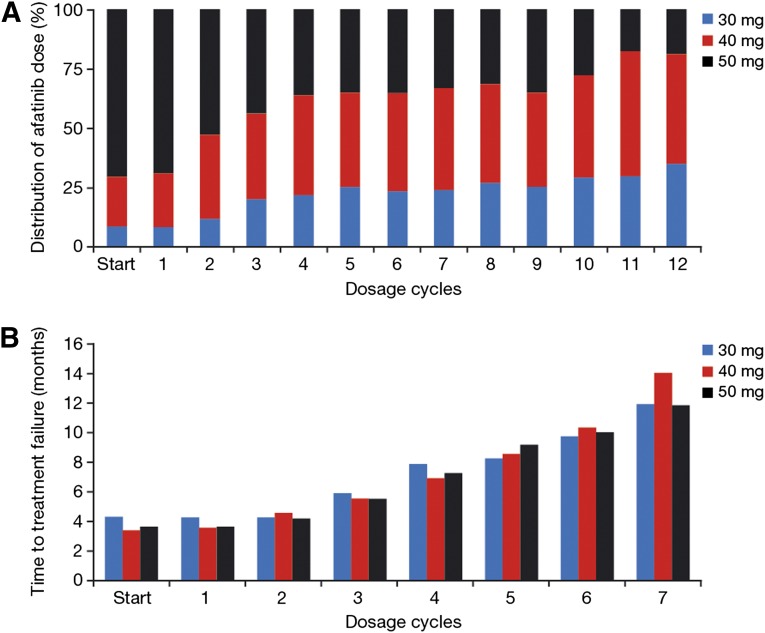

The starting dose of the CUP was defined as 50 mg/day afatinib; however, the actual starting dose could be varied by the treating physician depending on the individual patient’s tolerability of prior EGFR-TKI treatment and general performance status. Accordingly, starting doses were unevenly distributed from 50 mg (66%) to 40 mg (23%) to 30 mg (11%). Afatinib dose was escalated by one step in 9% and by two 10-mg increments in 1% of patients. The rate of dose reductions clearly depended on the afatinib starting dose (Fig. 3A). Main reasons for dose reductions were diarrhea (70% of dose reductions) and skin adverse events (24%). Dose reductions from a starting dose of 50 mg to 40 mg were required in 42% of patients. Moreover, 10% required two reduction steps to 30 mg. In contrast, 73% of patients starting on 40 mg afatinib maintained this dose level, whereas only 18% required reduction to 30 mg. Patients starting on 30 mg afatinib maintained this dose level in 69% of cases, whereas 31% were escalated to 40 mg (22%) or 50 mg (18%).

Figure 3.

Prevalence and impact of afatinib dose modifications. (A): Relative distribution of afatinib dose per cycle (cycles 1–12). (B): Median time to treatment failure in relation to afatinib dose calculated for each cycle (cycles 1–7).

The wide range and frequency of dose modifications in this CUP prompted us to study the impact of afatinib dose on treatment outcome. To exclude bias from early progression, which should be numerically over-represented in the group of patients starting with 50 mg (66% of patients) and under-represented in the groups starting at 40 mg (23%) and 30 mg (11%), we calculated the median TTF per dose level for each of the first 7 treatment cycles. This analysis revealed no difference in efficacy among the three dose levels (Fig. 3B).

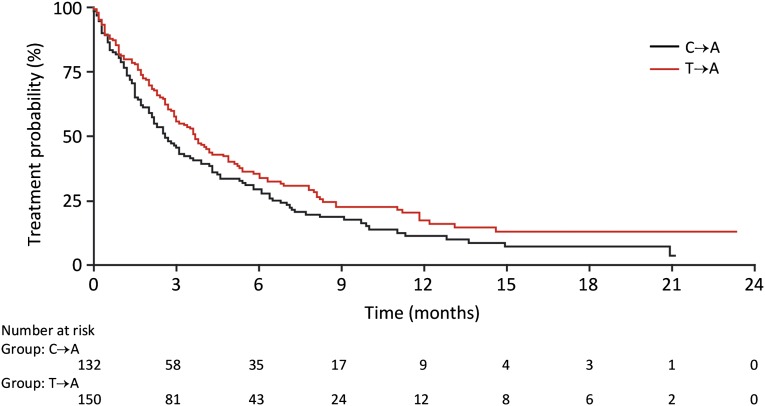

Impact of Immediate Pretreatment Type on Efficacy of Afatinib

It has been postulated that cancer subclones depending on the initially predominating mutant EGFR may repopulate the tumor once the selective pressure of EGFR-TKI treatment is relieved [21]. In line with such theoretical considerations and experimental evidence, the concepts of “rapid cycling” and “EGFR-TKI rechallenge” have been developed [22–24]. Against this background, we analyzed the potential impact of the treatment type immediately prior to enrollment into the afatinib CUP. In 250 patients, afatinib was used as salvage treatment directly after chemotherapy (C→A), whereas 289 patients went on afatinib at progression on EGFR-TKI (T→A). There was no difference (HR: 0.93) (Fig. 4A) in median TTF between group C→A (3.6 months [range: 0.0 to ongoing at 27.7 months]) and group T→A (3.8 months [range: 0.0 to ongoing at 29.0 months]). When this analysis was restricted to patients with confirmed EGFR-mutant NSCLC, a different picture emerged. The median TTF of 134 patients with EGFR-mutant tumors belonging to the C→A group amounted to only 2.6 months (range: 0.0 to ongoing at 21.1 months), which was significantly shorter (HR: 0.77; 95% CI [range: 0.59–1.0]; p = .048) than the median TTF of 151 patients with EGFR-mutant NSCLC belonging to the T→A group (3.7 months [range: 0.0 to ongoing at 23.3 months]) (Fig. 4B). More patients in the C→A group received afatinib at sixth line or higher (second or third line: 22%; fourth or fifth line: 25%; sixth line or higher: 53%) than patients in the T→A group (second or third line: 13%; fourth or fifth line: 51%; sixth line or higher: 36%).

Figure 4.

Time to treatment failure in relation to immediate pretreatment (chemotherapy followed by afatinib versus TKI followed by afatinib).

Abbreviations: C→A: afatinib directly after chemotherapy; EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; T→A: afatinib on progression with EGFR-TKI; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Intraindividual TTF of Reversible EGFR-TKI and Afatinib

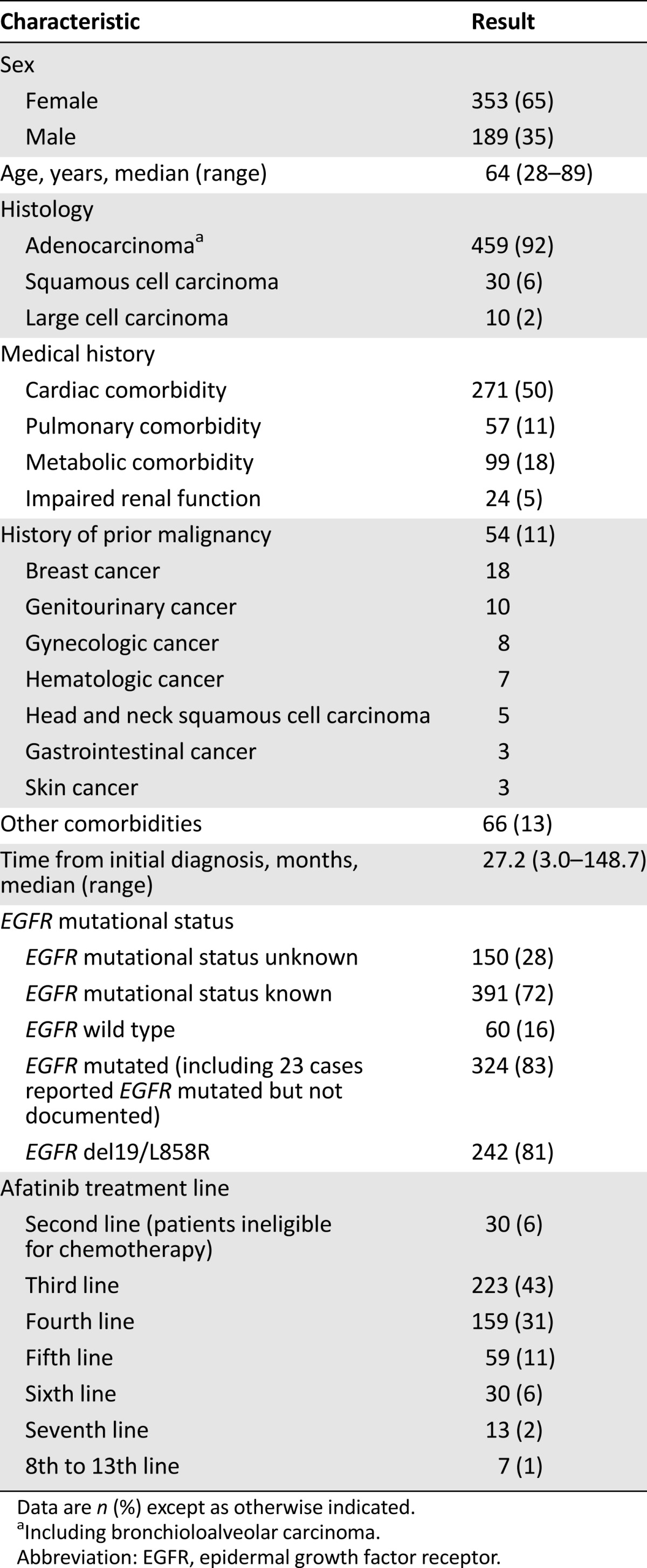

Overall, 80 patients (15%) were enrolled in the afatinib CUP following pretreatment with both reversible EGFR-TKIs, gefitinib and erlotinib. This provided an opportunity to compare the individual TTF of each drug in those individual patients. Because the probability of treatment response decreases with the number of prior EGFR-targeting therapies, this analysis was purely exploratory and hypothesis generating. Only 34% of these patients had received chemotherapy between the two EGFR-TKI treatment lines. In patients switched from gefitinib to erlotinib or vice versa, 82% went directly to the other EGFR-TKI. The duration of disease control with the next EGFR-targeting agent was classified as shorter than, equal to (±1 month), or longer than the time of disease control with the first EGFR-TKI. The predominant treatment sequence was gefitinib followed by erlotinib (49%), whereas 25% of patients were rechallenged with erlotinib after prior treatment with erlotinib, 21% received gefitinib following prior treatment with erlotinib, and 5% were re-exposed to gefitinib after prior treatment with gefitinib. When the reversible EGFR-TKI was changed (56 of 80 patients, 70%), the individual TTF with the second EGFR-TKI was equal to or longer than TTF with the first EGFR-TKI in 38% (15 of 39) to 47% (8 of 17) of patients (Fig. 5A, 5B). In contrast, rechallenge with the same EGFR-TKI resulted in equal or longer individual TTF in only 20% (4 of 20) to 25% (1 of 4) of patients (Fig. 5C, 5D).

Figure 5.

Efficacy of sequential EGFR-targeting therapies. (A–D): Efficacy of second treatment line with a reversible EGFR-TKI. (E–H): Efficacy of afatinib as third EGFR-targeting agent (patients still on afatinib treatment were excluded).

Abbreviations: EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; TKI, tyrosine kinase inhibitor.

Next, we studied in these patients the duration of disease control with afatinib. Again, we classified the individual time of disease control with afatinib as shorter than, equal to, or longer than the TTF with the prior reversible EGFR-TKI. Despite the fact that all patients had been pretreated with at least two independent lines of gefitinib and/or erlotinib, the duration of disease control with afatinib as the third or higher EGFR-targeting agent was equal to or longer than TTF with the prior EGFR-TKI in 69% (20 of 29) (Fig. 5E), 79% (11 of 14) (Fig. 5F), 56% (10 of 18) (Fig. 5G), or 50% (1 of 2) (Fig. 5H) of patients.

Discussion

The introduction and validation of biomarker-guided treatment of patients with EGFR-mutated metastatic lung cancers with gefitinib and erlotinib has been one of the greatest recent achievements in thoracic oncology. It is an epidemiologically most relevant clinical application of the personalized oncology paradigm in metastatic cancer and can be placed next to treatments targeting the estrogen receptor and HER2 in metastatic breast cancer. However, the clinical response of EGFR-mutated NSCLC to reversible EGFR-TKIs is variable, and disease is only transiently controlled. In particular, acquired resistance to EGFR-TKIs is intensely studied at the preclinical, translational, and clinical levels. Still, there is no formal consensus as to which is the optimal current treatment option for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC progressing on gefitinib or erlotinib. Most oncologists agree that clinically progressing patients who have received first-line EGFR-TKI treatment should be exposed to platinum-doublet chemotherapy if feasible. In current practice, multiple alternative or complementing strategies are applied, such as the addition of locally ablative therapies in patients with single-site progression [25], switching patients to the alternative EGFR-TKI [26], and combining EGFR-TKIs with chemotherapy [27]. Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines include afatinib as another treatment option in this setting [28], although this is not in compliance with the current label. Until the actual value of some of these strategies has been determined by ongoing controlled clinical trials, everyday treatment decisions have to be made based on the best available evidence.

To this end, we have undertaken a comprehensive analysis of the clinical database of a large national CUP of afatinib [12, 29]. Afatinib recently received approval by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and the European Medicines Agency for its strong activity in first-line treatment of patients with advanced or metastatic EGFR-mutated NSCLC [15, 16]. This CUP, however, enrolled heavily pretreated patients enriched for benefit from prior treatment with gefitinib and/or erlotinib, based on EGFR mutation status, objective response, or prolonged disease control. The intention of the afatinib CUP was to provide a treatment option for patients with no further established therapeutic option. Consequently, only a minimal and unconfirmed data set was required for inclusion, no structured data collection was rolled out, and no source data verification was performed. This limits the quality and generalizability of the data obtained by this analysis. Nevertheless, highly relevant clinical information can be drawn from this database, which includes 541 patients treated with afatinib. For example, 11% of patients had a second primary cancer and thus would have been excluded from participation of pivotal trials, which usually form the basis for regulatory approval. Because patients with second cancers are common in oncology practice, it is reassuring to know that the treatment and safety outcomes of this subgroup did not differ from those of the entire CUP population.

The main finding of our analysis is that afatinib may provide a clinically meaningful benefit to NSCLC patients that have progressed after pretreatment with chemotherapies and at least one reversible EGFR-TKI. Bearing all limitations in mind, these results support, under real-world conditions, the result of the LUX-Lung 1 study [19], which demonstrated significantly prolonged progression-free survival but not overall survival with afatinib treatment compared with placebo in a clinically enriched patient population. Although under-reporting, especially of lower grade adverse events, can be assumed, the CUP safety data add to the evidence gathered by the pivotal trials of afatinib. The median TTFs of 3.7 months for the entire CUP population and 4.6 months for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC compare favorably with the results from prospectively controlled trials of chemotherapy [30, 31] or targeted agents, which were studied mainly in second-line treatment [17, 32–37]. The CUP safety data add to the evidence gathered by the pivotal trials of afatinib, which were conducted for regulatory approval. Importantly, these results have been obtained largely in a community oncology setting, in which the vast majority of lung cancer patients are treated. By exploratory subgroup analysis, we interrogated the potential impact of a “treatment holiday” from EGFR-TKI on the outcome of re-exposure to a second or third EGFR-targeting agent. Rather unexpectedly, we observed that patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC fared better when they were put directly on afatinib following progression on gefitinib or erlotinib. Another surprising observation was made in the subgroup of 80 patients that had received at least three lines of EGFR-targeting therapy. In 41% (23 of 56) of patients who switched from gefitinib to erlotinib or vice versa, the time on treatment was equal or longer on the second reversible inhibitor than on the previous one. Moreover, 67% (42 of 63) of patients receiving afatinib as their third EGFR-targeting treatment experienced TTF equal to or longer than TTF with their previous EGFR-TKI. Certainly, this may be biased by both the patient’s and the physician’s attitudes toward the next EGFR-targeting therapy based on the positive experience of a prior clinical benefit, which would have been disregarded by the formal definition of progressive disease based on sum diameter calculations from imaging data. However, our results may actually better reflect the treatment outcome as assessed by the patient and the treating physician, which are among the most relevant endpoints in palliative cancer therapy.

Finally, the CUP enabled us to gain insights into contemporary clinical practice in Germany, which is the most highly populated country in Western and Central Europe. It is reassuring that while the CUP was active from 2010 to 2013, the fraction of patients that were ever tested for somatic EGFR mutations increased from 45% to 100%; however, a much smaller fraction of patients actually received gefitinib or erlotinib as first-line treatment. This might also have been influenced by the lack of full reimbursement for molecular testing in the German health care system.

Conclusion

This analysis of observational data provides important real-world evidence in support of further exploration of the activity and safety of afatinib-based treatment strategies for patients with EGFR-mutated NSCLC progressing after prior EGFR-targeting therapy.

See http://www.TheOncologist.com for supplemental material available online.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participating patients, physicians, and study nurses of this compassionate-use program. Editorial assistance, supported financially by Boehringer Ingelheim, was provided by Katie McClendon of GeoMed, part of KnowledgePoint360, an Ashfield Company, prior to submission of this article. The authors were fully responsible for all content and editorial decisions, were involved at all stages of manuscript development, and have approved the final version. Study group members are A. Abdollahi, A. Ammon, S.P. Aries, C. Arntzen, H.J. Achenbach, D. Atanackovic, A. Atmaca, N. Basara, D. Binder, B. Borchard, M. Bos, W. Brugger, S. Budweiser, K. Conrad, K. Corduan, D. Cortes-Incio, B. Dallmeier, C. Denzlinger, H.G. Derigs, N. Dickgreber, I. Dittrich, T. Düll, W. Engel-Riedel, M. Faehling, A. Fertl, J.R. Fischer, D. Fleckenstein, G. Folprecht, A. Forstbauer, Y. France, N. Frickhofen, S. Frühauf, M. Gardizi, T. Gauler, C. Gessner, W. Gleiber, E. Gökkurt, M. Görner, C. Grah, J. Greeve, J. Greiner, F. Griesinger, C. Grohé, W. Grüning, D. Guggenberger, S. Gütz, C. Hannig, D. Heigener, M. Heilmann, B. Heinrich, G. Hense, M. Hoiczyk, R.M. Huber, G. Illerhaus, G. Jacobs, P. Jung, K.O. Kambartel, J. Kern, J. Kersten, M. Kiehl, M. Kimmich, J. Kisro, H. Knipp, Y.D. Ko, J.U. Koch, C.H. Koehne, J. Kollmeier, A. Kommer, W. Körber, K. Kratz-Albers, G. Krause, R. Krügel, E. Laack, R. Leistner, U. Liebers, M. Lommatzsch, C. Maintz, C. Mozek, A. Matzdorff, M. Mohr, W. Neumeister, H. Nolte, T. Overbeck, M. Östreicher, J. Panse, T. Pelzer, K. Peters, M. Planker, A. Reissig, M. Ritter, A. Rittmeyer, S. Rösel, P. Sadjadian, B. Sandritter, M. Schatz, M. Scheffler, G. Schmid-Bindert, A. Schmittel, C.P. Schneider, W. Schneider-Kappus, F. Schneller, E. Schorb, J. Schreiber, F. Schüler, M. Schuler, A. Schulz-Abelius, C. Schumann, W. Schütte, S. Schütz, M. Schütz, M. Sebastian, M. Serke, D. Spissinger, W. Spengler, H. Staiger, U. Steffen, I. Stehle, H. Steiniger, K. Stengele, S. Steppert, J. Stöhlmacher-Williams, T. Strapatsas, B. Sulzbach, A. Tessmer, M. Thomas, B. Thöming, D. Ukena, B. Wagner, T. Wagner, D. Wagner-Hug, H. Wahn, T. Wehler, R. Wiewrodt, C. Witt, M. Wohlleber, J. Wolf, M. Wolf, K. Wricke, O. Zaba, I. Zander.

Footnotes

For Further Reading:Myung-Ju Ahn, Sang-We Kim, Byoung-Chul Cho et al. Phase II Study of Afatinib as Third-Line Treatment for Patients in Korea With Stage IIIB/IV Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Harboring Wild-Type EGFR. The Oncologist 2014;19:702–703.

Abstract:Background. This phase II single-arm trial evaluated afatinib, an irreversible inhibitor of the ErbB receptor family as third-line treatment of Korean patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and tumors with wild-type EGFR. Currently, no standard therapy exists for these patients.

Methods. Eligible patients had stage IIIB/IV wild-type EGFR lung adenocarcinoma and had failed to benefit from two previous lines of chemotherapy but had not received anti-EGFR treatment. Patients received oral afatinib at 40 mg per day until disease progression or occurrence of intolerable adverse events (AEs). The primary endpoint was confirmed objective tumor response (OR) rate (confirmed complete response [CR] or partial response [PR]). Secondary endpoints included disease control rate (DCR; OR or stable disease for ≥6 weeks), progression-free survival (PFS), and safety.

Results. Forty-two patients received afatinib treatment, and 38 of those were included in efficacy analyses. No confirmed CRs or PRs were reported. DCR was 24% (9 of 38 patients), with a median disease control duration of 19.3 weeks. Median PFS was 4.1 weeks (95% confidence interval: 3.9–8.0). Frequently reported AEs (mainly grades 1 and 2) were rash/acne (88%), diarrhea (62%), and stomatitis (57%).

Conclusion. Heavily pretreated patients with wild-type EGFR NSCLC treated with afatinib monotherapy did not experience an objective response and only 24% had disease stabilization lasting more than 6 weeks. AEs were manageable and consistent with the expected safety profile.

Author Contributions

Conception/Design: Martin Schuler, Angela Märten

Provision of study material or patients: Martin Schuler, Angela Märten

Collection and/or assembly of data: Jürgen R. Fischer, Christian Grohé, Sylvia Gütz, Michael Thomas, Martin Kimmich, Claus-Peter Schneider, Eckart Laack

Data analysis and interpretation: Martin Schuler, Angela Märten

Manuscript writing: Martin Schuler, Jürgen R. Fischer, Christian Grohé, Sylvia Gütz, Michael Thomas, Martin Kimmich, Claus-Peter Schneider, Eckart Laack, Angela Märten

Final approval of manuscript: Martin Schuler, Jürgen R. Fischer, Christian Grohé, Sylvia Gütz, Michael Thomas, Martin Kimmich, Claus-Peter Schneider, Eckart Laack, Angela Märten

Disclosures

Martin Schuler: Boehringer Ingelheim (C/A, RF); Angela Märten: Boehringer Ingelheim (E); Christian Grohé: Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Boehringer (C/A); Lilly, Novartis, Roche, Boehringer (H); Michael Thomas: Roche, Lilly, Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb (C/A); Bristol-Myers Squibb (H); Claus-Peter Schneider: Roche, Boehringer, AstraZeneca, TEVA, Lilly, Pfizer, Amgen, Novartis (SAB); Martin Kimmich: Boehringer-Ingelheim (C/A, SAB). The other authors indicated no financial relationships.

(C/A) Consulting/advisory relationship; (RF) Research funding; (E) Employment; (ET) Expert testimony; (H) Honoraria received; (OI) Ownership interests; (IP) Intellectual property rights/inventor/patent holder; (SAB) Scientific advisory board

References

- 1.World cancer factsheet. Available at http://publications.cancerresearchuk.org/downloads/product/CS_FS_WORLD_A4.pdf Accessed February 28, 2014.

- 2.Weir BA, Woo MS, Getz G, et al. Characterizing the cancer genome in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2007;450:893–898. doi: 10.1038/nature06358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ding L, Getz G, Wheeler DA, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lynch TJ, Bell DW, Sordella R, et al. Activating mutations in the epidermal growth factor receptor underlying responsiveness of non-small-cell lung cancer to gefitinib. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2129–2139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paez JG, Jänne PA, Lee JC, et al. EGFR mutations in lung cancer: Correlation with clinical response to gefitinib therapy. Science. 2004;304:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1099314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rosell R, Carcereny E, Gervais R, et al. Erlotinib versus standard chemotherapy as first-line treatment for European patients with advanced EGFR mutation-positive non-small-cell lung cancer (EURTAC): A multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:239–246. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70393-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mitsudomi T, Morita S, Yatabe Y, et al. Gefitinib versus cisplatin plus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer harbouring mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor (WJTOG3405): An open label, randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:121–128. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70364-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maemondo M, Inoue A, Kobayashi K, et al. Gefitinib or chemotherapy for non-small-cell lung cancer with mutated EGFR. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:2380–2388. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0909530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu HA, Arcila ME, Rekhtman N, et al. Analysis of tumor specimens at the time of acquired resistance to EGFR-TKI therapy in 155 patients with EGFR-mutant lung cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2013;19:2240–2247. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li D, Ambrogio L, Shimamura T, et al. BIBW2992, an irreversible EGFR/HER2 inhibitor highly effective in preclinical lung cancer models. Oncogene. 2008;27:4702–4711. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gonzales AJ, Hook KE, Althaus IW, et al. Antitumor activity and pharmacokinetic properties of PF-00299804, a second-generation irreversible pan-erbB receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:1880–1889. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Targeting resistance in lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2013;3:OF9. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-ND2013-025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sequist LV, Yang JC, Yamamoto N, et al. Phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin plus pemetrexed in patients with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3327–3334. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.44.2806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang JC, Hirsh V, Schuler M, et al. Symptom control and quality of life in LUX-Lung 3: A phase III study of afatinib or cisplatin/pemetrexed in patients with advanced lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR mutations. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:3342–3350. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miller VA, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Afatinib versus placebo for patients with advanced, metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer after failure of erlotinib, gefitinib, or both, and one or two lines of chemotherapy (LUX-Lung 1): A phase 2b/3 randomised trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13:528–538. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Murakami H, Tamura T, Takahashi T, et al. Phase I study of continuous afatinib (BIBW 2992) in patients with advanced non-small cell lung cancer after prior chemotherapy/erlotinib/gefitinib (LUX-Lung 4) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2012;69:891–899. doi: 10.1007/s00280-011-1738-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller V, Hirsh V, Cadranel J, et al. Phase IIb/III double-blind randomized trial of afatinib (BIBW2992), an irreversible inhibitor of EGFR/Her1 and Her2 plus best supportive care (BSC) versus placebo + BSC in patients with NSCLC failing 1-2 lines of chemotherapy and erlotinib or gefitinib (LUX-Lung 1) Ann Oncol. 2010;21(suppl 8):LBA1a. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackman D, Pao W, Riely GJ, et al. Clinical definition of acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:357–360. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chmielecki J, Foo J, Oxnard GR, et al. Optimization of dosing for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer with evolutionary cancer modeling. Sci Transl Med. 2011;3:90ra59. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hata A, Katakami N, Yoshioka H, et al. Erlotinib after gefitinib failure in relapsed non-small cell lung cancer: Clinical benefit with optimal patient selection. Lung Cancer. 2011;74:268–273. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wong MK, Lo AI, Lam B, et al. Erlotinib as salvage treatment after failure to first-line gefitinib in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2010;65:1023–1028. doi: 10.1007/s00280-009-1107-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo R, Chen X, Wang T, et al. Subsequent chemotherapy reverses acquired tyrosine kinase inhibitor resistance and restores response to tyrosine kinase inhibitor in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:90. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Weickhardt AJ, Scheier B, Burke JM, et al. Local ablative therapy of oligoprogressive disease prolongs disease control by tyrosine kinase inhibitors in oncogene-addicted non-small-cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2012;7:1807–1814. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182745948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oxnard GR, Arcila ME, Chmielecki J, et al. New strategies in overcoming acquired resistance to epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitors in lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17:5530–5537. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goldberg SB, Oxnard GR, Digumarthy S, et al. Chemotherapy with erlotinib or chemotherapy alone in advanced non-small cell lung cancer with acquired resistance to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The Oncologist. 2013;18:1214–1220. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2013-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines). Non-small cell lung cancer, version 3. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/nscl.pdf Accessed March 4, 2014.

- 29.Solca F, Dahl G, Zoephel A, et al. Target binding properties and cellular activity of afatinib (BIBW 2992), an irreversible ErbB family blocker. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2012;343:342–350. doi: 10.1124/jpet.112.197756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hanna N, Shepherd FA, Fossella FV, et al. Randomized phase III trial of pemetrexed versus docetaxel in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:1589–1597. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shepherd FA, Dancey J, Ramlau R, et al. Prospective randomized trial of docetaxel versus best supportive care in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer previously treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:2095–2103. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.10.2095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shepherd FA, Rodrigues Pereira J, Ciuleanu T, et al. Erlotinib in previously treated non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:123–132. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thatcher N, Chang A, Parikh P, et al. Gefitinib plus best supportive care in previously treated patients with refractory advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a randomised, placebo-controlled, multicentre study (Iressa Survival Evaluation in Lung Cancer) Lancet. 2005;366:1527–1537. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67625-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ramalingam SS, Blackhall F, Krzakowski M, et al. Randomized phase II study of dacomitinib (PF-00299804), an irreversible pan-human epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitor, versus erlotinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:3337–3344. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.9433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herbst RS, Sun Y, Eberhardt WE, et al. Vandetanib plus docetaxel versus docetaxel as second-line treatment for patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer (ZODIAC): A double-blind, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:619–626. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(10)70132-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Boer RH, Arrieta Ó, Yang CH, et al. Vandetanib plus pemetrexed for the second-line treatment of advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: A randomized, double-blind phase III trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1067–1074. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.5717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Natale RB, Bodkin D, Govindan R, et al. Vandetanib versus gefitinib in patients with advanced non-small-cell lung cancer: Results from a two-part, double-blind, randomized phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2523–2529. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.