Abstract

Histone deacetylases (HDACs) are important regulators of gene expression as part of transcriptional corepressor complexes. Here, we demonstrate that caspases can repress the activity of the myocyte enhancer factor (MEF)2C transcription factor by regulating HDAC4 processing. Cleavage of HDAC4 occurs at Asp 289 and disjoins the carboxy-terminal fragment, localized into the cytoplasm, from the amino-terminal fragment, which accumulates into the nucleus. In the nucleus, the caspase-generated fragment of HDAC4 is able to trigger cytochrome c release from mitochondria and cell death in a caspase-9–dependent manner. The caspase-cleaved amino-terminal fragment of HDAC4 acts as a strong repressor of the transcription factor MEF2C, independently from the HDAC domain. Removal of amino acids 166–289 from the caspase-cleaved fragment of HDAC4 abrogates its ability to repress MEF2 transcription and to induce cell death. Caspase-2 and caspase-3 cleave HDAC4 in vitro and caspase-3 is critical for HDAC4 cleavage in vivo during UV-induced apoptosis. After UV irradiation, GFP-HDAC4 translocates into the nucleus coincidentally/immediately before the retraction response, but clearly before nuclear fragmentation. Together, our data indicate that caspases could specifically modulate gene repression and apoptosis through the proteolyic processing of HDAC4.

INTRODUCTION

Cell death by apoptosis is a genetically regulated program that plays a fundamental role during development and tissue homeostasis in metazoans (Cryns and Yuan, 1998). The family of cysteine proteases named caspase, represents the critical enzymatic activity that executes the apoptotic program (Shi, 2002). Caspases work in a hierarchical order; regulative caspases cleave and activate effector caspases, which in turn process a few hundred proteins known as death substrates (Fischer et al., 2003). Caspases, through the cleavage of death substrates, control cell survival and the morphological changes that orchestrate the apoptotic phenotype (Cryns and Yuan, 1998).

Transcription factors such as myocyte enhancer factor (MEF)2 (NF–E2-related factor 2), serum response factor (SRF), CREB (cAMP response element-binding protein), FOXO3a (forkhead box-03a), and NRF2 are cleaved by caspases during apoptosis, and this processing induces loss of their transcriptional activity and suppression of their prosurvival functions (Ohtsubo et al., 1999; Bertolotto et al., 2000; Francois et al., 2000, Drewett et al., 2001; Li et al., 2001; Okamoto et al., 2002; Charvet et al., 2003; Fischer et al., 2003). This implies that caspases can act as indirect modulators of the expression of prosurvival genes and can therefore be considered as transcriptional repressors.

In eukaryotic cells, the genetic information is packaged into chromatin, a highly organized macromolecular complex composed of DNA, histones, and nonhistone proteins (Kornberg and Lorch, 2002). Posttranslational modifications of histones such as acetylation, phosphorylation, and methylation can locally modulate the higher order nucleosome architecture and play an important role in the control of gene expression (Woodcock and Dimitrov, 2001). Histone acetylation is regulated by two family of enzymes, the histone acetyl transferases (HATs) and the histone deacetylases (HDACs), which catalyze, respectively, the addition or the hydrolysis of acetyl groups to lysine residues of nucleosomal histones (Hassig and Schreiber, 1997).

Eighteen different HDACs have been identified and grouped into three distinct classes based on sequence homology to distinct yeast HDACs. Class I HDACs, which includes HDAC1, 2, 3, 8, and 11, shows similarity to yeast RPD3 protein. Class II HDACs is characterized by sequence homology to yeast HDA1 and can be subdivided into class IIa, which includes HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9, and class IIb to which HDAC6 and 10 belong. Finally, HDACs belonging to class III show sequence similarity to Sir2, a yeast transcriptional repressor that requires NAD+ as a cofactor for its deacetylase activity (Grozinger and Schreiber, 2002; Peterson, 2002; Verdin et al., 2003).

Posttranslational modifications of histones have been already observed during apoptosis. Phosphorylation of histone H2A, H2B, and H3 and also dephosphorylation of histone H1 characterize cell death (Waring et al., 1997; Ajiro, 2000; Kratzmeier et al., 2000; Rogakou et al., 2000). More recently, it has been reported that caspase-cleaved MstI kinase phosphorylates histone H2B at serine 14 (Cheung et al., 2003). However, how these alterations could promote changes in chromatin architecture during apoptosis is unclear.

Little is known about the modification of histone acetylation and on the function of HDACs during apoptosis. We decided to investigate whether caspases could modulate histone acetylation through the proteolytic processing of HDACs. Here, we report that caspases can modulate HDAC activity in a highly restricted manner. HDAC4 is cleaved by caspase-2 and -3, whereas HDAC1, 2, 3, and 6 are not, and HDAC5 is cleaved with reduced efficiency only by caspase-3. Caspase-dependent processing of HDAC4 occurs at Asp 289 and severs the carboxy-terminal fragment, which localizes into the cytoplasm, from the amino-terminal fragment, which accumulates into the nucleus. HDAC4 binds and represses MEF2, the activity of which is critical for different biological responses, including cell survival and apoptosis (Mao et al., 1999; Youn et al., 1999). The caspase-cleaved amino-terminal fragment of HDAC4 triggers cell death and acts as a strong repressor of the transcription factor MEF2C. Finally, a deletion of the amino-terminal caspase-cleaved fragment of HDAC4, which has lost the repressive activity, was also unable to trigger cell death, thus strengthening the association between the apoptotic function of HDAC4 and its repressional activity

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Culture Conditions, Transfection, Microinjection, and Time-Lapse Analysis

Cells were grown in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/ml), glutamine (2 mM), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml) at 37°C in 5% CO2 atmosphere. Transfections were performed using the calcium phosphate precipitation method. U2OS cells stably expressing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-HDAC4 or GFP-HDAC4/D289E were selected for resistance to G418. Small interfering RNA (siRNA) for caspase-2 was purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO), based on a previously published sequence and transfected as described in Lassus et al. (2002). Nucleotides GC (99/100) were changed to AT in the mutated siRNA. Microinjection was performed using the Automated Injection system (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany) as described previously (Paroni et al., 2002). Tetramethylrhodamine B isothiocyanate (TRITC)-dextran, 66 kDa (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), was used at the concentration of 1 mg/ml. Time-lapse studies were performed using a laser scan microscope (Leica TCS NT) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37°C.

Reporter Gene Assays

For luciferase assays, HeLa cells grown in 3-cm-diameter culture dishes were transfected at 30–40% confluence with the indicated mammalian expression plasmids. Cells were collected and luciferase activity was measured and normalized for Renilla luciferase activity by using the Dual Luciferase Reporter assay system, according to manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI).

HDAC Assay

Histone deacetylase assay was carry out using the HDAC colorimetric assay kit Color deLys (BIOMOL Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA). Nuclear extracts from HeLa cells suspended in the digestion buffer (100 mM PIPES, pH 6.5, 2 mM EDTA, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM dithiothreitol, 10 μg/ml CLAP [chymostatin, leupeptin, antipain, pepstatin), were incubated in the presence of caspase-3 for 1 h and then assayed for HDAC activity. Trichostatin-A (TSA) was used at 1 μM final concentration.

Antibody Production and Western Blotting

Rabbits were immunized with recombinant histidine-tagged GFP purified from Escherichia coli. For anti-GFP antibody purification from antiserum, GFP was fused to glutathione S-transferase (GST) and cross-linked to glutathione-Sepharose as described previously (Paroni et al., 2001). Similarly anti-HDAC antiserum was produced against histidine-tagged HDAC4 fragment 359–651 and purified against the same fragment fused to GST.

Western blotting were performed as described previously (Paroni et al., 2001). The following primary antibodies were used: anti-HDAC4, anticaspase-2, anti-GFP, anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich), anti-p85 poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) fragment (Promega), anti-actin, and anti-tubulin (Henderson et al., 2003). As secondary antibodies, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) or goat anti-mouse (Euroclone, Westyorkshire, United Kingdom) were used. Blots were developed with Super Signal West Pico or Dura, as recommended by the manufacturer (Pierce Chemical). Triton X-100 extraction buffer (20 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA 1 mM dithiothreitol, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 10 μg/ml CLAP (chymostatin, leupeptin, antipain, pepstatin), 10 μg/ml cytochalasin B, and 0.5% Triton X-100) was used to prepare crude nuclear and cytosolic extracts.

Immunofluorescence Microscopy

For indirect immunofluorescence microscopy, cells were fixed with 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline for 20 min at room temperature. After permeabilization, coverslips were treated with the anti-cytochrome c (Promega), the anti-caspase-2, or with anti-FLAG (Sigma-Aldrich) antibodies, diluted in phosphate-buffered saline. After washing, they were incubated with the relative Alexa Fluor 546-conjugated secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR). Cells were examined with a laser scan microscope (Leica TCS NT) equipped with a 488–534 λ Ar laser and a 633 λ He-Ne laser.

In Vitro Proteolytic Assay

Caspase-2 and -3 were expressed in bacteria and purified as described previously (Henderson et al., 2003). The cDNAs of the different HDACs were in vitro translated with 35S by using the TNT-coupled reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). One microliter of each, in vitro-translated, was incubated with recombinant caspase-2 or caspase-3 in 15 μl of the appropriate digestion buffer (final volume) for 1 h at 37°C. Reactions were terminated by adding 1 volume of SDS gel loading buffer and boiling for 3 min.

Plasmid Construction

pFLAGCMV5 constructs expressing HDAC-4 full length, HDAC4Δ1-289 (HDAC4ΔN), and HDAC4Δ289-1084 (HDAC4ΔC) were generated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with pCDNA 3.1 Myc-HisHDAC4 as template and the following set of primers containing EcoRI cloning sites: primer Up-FL 5′CATGAATTCATGAGCTCCCAAAGCCATCCA3′, primer Do-FL 5′CATGAATTCGCAGGGGCGGCTCCTCTTCCAT3′, primer Up-Δ289-1084 5′CATGAATTCATGTCCGCGTGCAGCAGCGCCCCA3′, and primer Do-Δ1-289 5′CATGAATTCGTCTGTGACATCCAACGGACG3′,

To generate pCDNA3HDAC4-FL, -HDAC4ΔN, and -HDAC4ΔC, the relative EcoRI fragments were subcloned from the respective pFLAGCMV5 constructs. In vitro mutagenesis to generate HDAC4D289E mutant was performed using the Gene-Taylor kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The following sets of primer were used: primer Up-middle 5′AGCGTCCGTTGGATGTCACAGAGTCCGCGTGCAG 3′, primer Do-middle 5′TGTGACATCCAACGGACGCTTTTTTAGAGC3′. pFLAGCMV5 construct expressing HDAC4/1-165 was generated by PCR with pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔC as template and the following set of primers containing EcoRI and BamH1 cloning sites: primer Up-FL 5′CATGAATTCATGAGCTCCCAAAGCCATCCA3′, primer Down-165 5′CATGGATCCGGCACTCTCTTTGCCCTTCTC3′.

pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4/1-165 was used to generate pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4Δ166-184 by inserting the fragment 185–289 of HDAC4 containing BamH1 sites and obtained by PCR with pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔC as template and the following set of primers; Up-185 5′CATGGATCCGCGCTGGCCCACCGGAATCTG3′, Down-289N 5′CATGGATCCGTCTGTGACATCCAACGGACG3′.

All constructs generated were sequenced to check for the respective introduced mutations, deletions, and the translating fidelity of the inserted PCR fragments.

RESULTS

HDAC4 Is Cleaved by Caspase-2 and Caspase-3

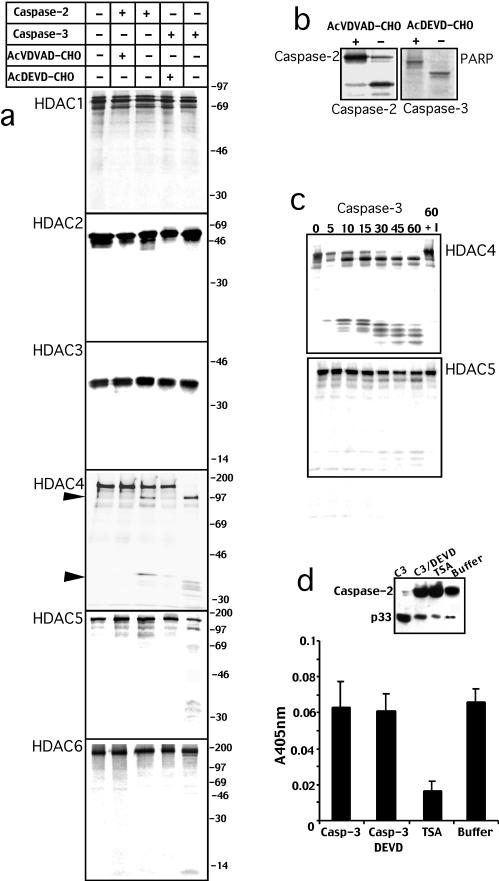

To investigate the ability of caspases to modulate HDAC activity during apoptosis, we used an in vitro proteolytic assay. For this study, caspase-2 and caspase-3 were selected because caspase-2 is localized in the nuclear compartment (Paroni et al., 2002; Baliga et al., 2003), and it is still unclear how it can regulate apoptosis, whereas caspase-3 plays a major role as an effector caspase during apoptosis (Fischer et al., 2003). Recombinant caspase-2 and caspase-3 were incubated with in vitro translated HDACs 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 in the presence or absence of the specific inhibitors. As shown in Figure 1a, incubation of HDAC4 with recombinant caspase-2 generates two fragments of ∼97 and 34 kDa, indicating the existence of a single caspase-2 cleavage site. The proteolytic processing of HDAC4 was inhibited by the presence of the specific caspase-2 inhibitor Ac-VDVAD-CHO. Caspase-3 processed HDAC4 into an ∼97-kDa fragment similarly to caspase-2, whereas the 34-kDa fragment was further proteolyzed into smaller fragments. Ac-DEVD-CHO, a specific caspase-3 inhibitor, suppressed caspase-3–dependent processing of HDAC4. HDAC1, 2, 3, and 6 were not cleaved neither by caspase-2 nor by caspase-3 under these experimental conditions. Caspase-3, but not caspase-2, was also able to process HDAC5, albeit with lower efficiency compared with HDAC4. The proteolytic processing of caspase-2 and PARP, caspase-2– and caspase-3–specific substrates, respectively (Paroni et al., 2001), has been included in Figure 1b for comparison.

Figure 1.

HDAC4 is a new caspase-2 and caspase-3 substrate. (a) [35S]Methionine-labeled in vitro-translated products of the indicated HDACs were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with recombinant caspase-2, caspase-3, and the specific inhibitors or with buffer alone as indicated. (b) [35S]Methionine-labeled in vitro-translated caspase-2 and PARP were incubated for 1 h at 37°C, respectively, with recombinant capase-2 and caspase-3 in the presence or absence of the specific inhibitor as indicated. (c) [35S]Methionine-labeled in vitro-translated HDAC4 and HDAC5 were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with recombinant caspase-3 for the indicated minutes or for 60 min in the presence of the specific inhibitor (60+I). (d) HeLa nuclear extracts were incubated with recombinant caspase-3 (C3), caspase-3 and the specific inhibitor (C3/DEVD), with TSA or with buffer alone. Caspase-2 processing was detected by Western blot by using the specific antibody. Deacetylase activity, measured with the colorimetric activity assay, was reported as absorption at 405 nm. Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for three independent experiments.

The ability of caspase-3 to cleave HDAC5, with low efficiency, has been confirmed by an in vitro proteolytic time course. The same enzymatic units of caspase-3 that produced a full processing of HDAC4 within 30 min, triggered only a partial processing of HDAC5 after 60 min of incubation (Figure 1c).

These results suggest that during apoptosis caspases could modulate HDAC4 and perhaps HDAC5 activities. However, because other HDACs were not cleaved by caspase-2 and -3, it could be postulated that the overall HDAC activity in apoptotic cells is unaffected by caspases. To confirm this hypothesis we decided to evaluate HDAC activity in nuclear extracts incubated with caspase-3. The inset in Figure 1d shows that recombinant caspase-3 efficiently process caspase-2 in HeLa nuclear extracts. Next, we measured, by using a colorimetric assay, HDAC activity in nuclear extracts incubated with caspase-3, caspase-3 plus Ac-DEVD-CHO, or with the HDAC inhibitor TSA. We did not observe changes in HDAC activity when nuclear extracts were incubated with caspase-3, whereas TSA efficiently suppressed HDAC activity. Hence, we can suggest that caspase-2 and -3 selectively modulate HDAC4 function during apoptosis.

HDAC4 Is Cleaved at Aspartic Acid 289 In Vitro and during Apoptosis In Vivo

HDAC4 belongs to the class IIa of histone deacetylases that exhibit tissue-specific expression and nuclear cytoplasmic shuttling (Verdin et al., 2003). Class IIa HDACs contains two regions, each encompassing one-half of the protein: a carboxy-terminal catalytic domain resembling that of yeast HDA1 and an amino terminus regulatory domain (Figure 2a). HDAC4 interacts with multiple partners, including members of the MEF2 family of transcription factors and the 14-3-3 chaperone proteins (Grozinger and Schreiber, 2000; McKinsey et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000; Borghi et al., 2001; Miska et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2001).

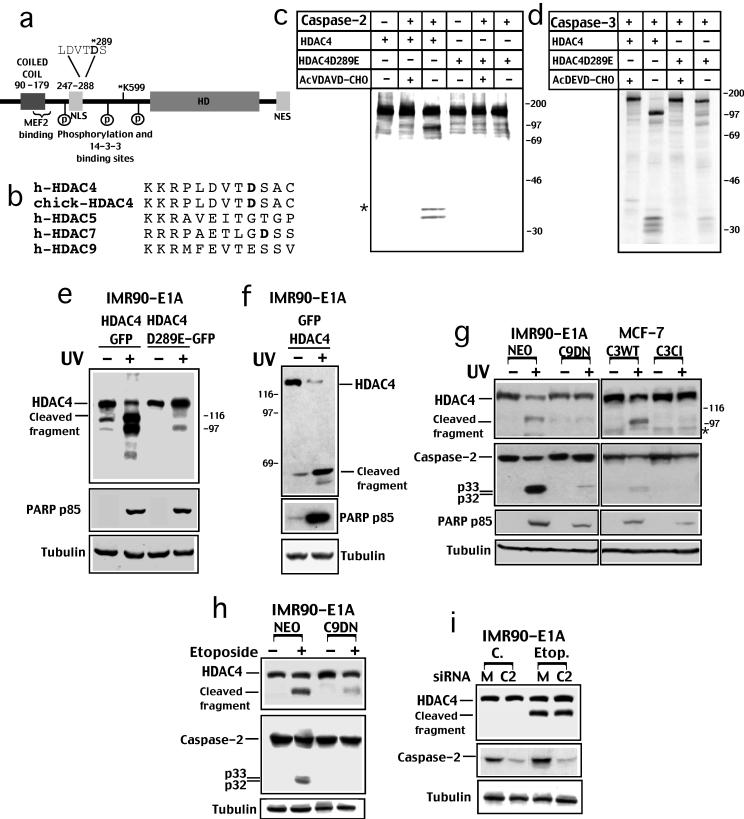

Figure 2.

HDAC4 is cleaved at aspartic acid 289 in vitro and during apoptosis in vivo. (a) Schematic structure of HDAC4 pointing out the putative caspase-2 and -3 cleavage site at Asp 289. The NLS in the amino-terminal region and the NES in the carboxy-terminal are evidenced. The HDAC catalytic domain and corepressor (N-CoR and SMRT) binding region is evidenced (HD). A coiled-coil region at the amino terminus, including the MEF2 binding domain, is also evidenced. The amino-terminal region also mediates the interaction with the transcriptional corepressor CtBP. Binding sites for the 14-3-3 proteins are marked as P. Lysine 599 represents the sumoylated residue. (b) Comparison of the human HDAC4 amino acid sequences containing the caspase-2 and -3 consensus cleavage site with chick-HDAC4, HDAC5, HDAC7, and HDAC9, the putative cleaved Asp residues are shown in bold. (c) [35S]Methionine-labeled in vitro-translated HDAC4 and the point mutant HDAC4/D289E were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with caspase-2, with caspase-2 and the specific inhibitor, or with buffer alone as indicated. The asterisk points out a second cleaved band, which originates from a different translation start codon. (d) [35S]Methionine-labeled in vitro translated HDAC4 and the point mutant HDAC4/D289E were incubated for 1 h at 37°C with caspase-3 or with caspase-3 and the specific inhibitor as indicated. (e) IMR90-E1A cells were transfected with pEGFPN1-HDAC4 (HDAC4-GFP) or with pEGFPN1-HDAC4/D289E (HDAC4/D289E-GFP). After 18 h cells were UV irradiated (+) or left untreated (-). Cells were lysed 12 h later, and equal amounts of lysates were subjected to Western immunoblotting by using the anti-GFP antibody to visualize HDAC4 or the indicated antibodies. HDAC4 cleaved fragment is indicated. (f) IMR90-E1A cells were transfected with pEGFPC2-HDAC4 (GFP-HDAC4). After 18 h cells were UV irradiated (+) or left untreated (-). Cells were lysed and equal amounts of proteins were subjected to Western immunoblotting by using the anti-GFP antibody, to visualize HDAC4, or the indicated antibodies. HDAC4 cleaved fragment is indicated. (g) IMR90-E1A, IMR90-E1A/C9DN, MCF-7/C3WT and MCF-7/C3CI cells were UV irradiated or left untreated. Cells were lysed and equal amounts of proteins were subjected to Western immunoblotting by using the indicated antibodies. * points to a faint band detectable in MCF-7 cells that could represent either a nonspecific signal or a degradation product. (h) IMR90-E1A cells expressing neomycin (NEO) or catalytically inactive caspase-9 (C9DN) were treated or not with etoposide (25 μg/ml). After 18 h, cells were lysed, and equal amounts of proteins were subjected to Western immunoblotting by using the indicated antibodies. 1) Western blot of IMR90-E1A cell lysates treated or not with etoposide (25 μg/ml) shows the effect of caspase-2 siRNA (siRNAC2) transfection on HDAC4 processing. Mutated siRNA (siRNAM) was used as a control.

To identify the caspase cleavage site in HDAC4 responsible for generating the ∼34- and ∼97-kDa fragments, we examined its sequence for caspase-2 and -3 cleavage motifs and found a potential cleavage site at aspartic 289 (LDVTD) that could generate processed products of the expected size. The putative caspase-2 and -3 cleavage site is conserved between human and chick HDAC4, but it was not present in other class IIa HDACs (Figure 2b).

To verify the cleavage of HDAC4 at the described consensus site, Asp residue 289 was changed to Glu by site-directed mutagenesis and in vitro-translated HDAC4/D289E was incubated with recombinant caspase-2 (Figure 2c) or caspase-3 (Figure 2d). Fragments of the expected size were generated when HDAC4wt was digested with caspase-2 or -3. Instead, the point mutant HDAC4/D289E was not cleaved when incubated with caspase-2 and the cleavage was dramatically reduced in the case of incubation with caspase-3. Similar results were obtained when the HDAC4/D289A mutant was used (our unpublished data). The asterisk in Figure 2c points to a second fragment observed when hemagglutinin (HA)-tagged HDAC4 was incubated with caspase-2. This second fragment originates from a second translation start codon (our unpublished data). It is important to note that the different cleaved fragments observed after processing of HDAC4 with caspase-3 were all dramatically reduced in the case of the D289E mutant. This evidence indicates that only after cleavage at Asp289 further processing of the amino-terminal region can occur. Interestingly, different Asp residues at aa 234 and 237 that could represent further caspase-cleavage sites are present within the amino-terminal fragment of HDAC4.

Having demonstrated that HDAC4 is cleaved by caspases in vitro at Asp289, we wanted to investigate whether it is also cleaved by caspases in vivo during apoptosis. To this end, we fused HDAC4 and the mutant HDAC4/D289E with GFP at their carboxy- or amino-terminals to visualize both cleaved fragments. IMR90-E1A cells were transfected with the different GFP constructs, UV irradiated, or left untreated, and cell lysates were prepared for Western analysis by using an anti-GFP antibody. As shown in Figure 2, e and f, HDAC4 was processed in UV-treated IMR90-E1A cells. Both the amino- and the carboxy-terminal fragments were detected with a size similar to the in vitro generated fragments. Cleavage was inhibited when HDAC4/D289E was expressed, even though caspases were active, as confirmed by the detection of PARP p85-cleaved fragment. Similar results were obtained when HDAC4/D289A mutant was expressed (our unpublished data). Of note, in apoptotic cells, the carboxy-terminal fragment was further proteolyzed into smaller fragments. Because these additional proteolytic events were dramatically reduced in the case of the mutant HDAC4/D289E, it is possible that they occur, as demonstrated above for the amino-terminal region, only after the caspase cleavage at Asp 289.

To investigate whether endogenous HDAC4 was processed during apoptosis, we generated an antibody against HDAC4 (aa 359–651). This antibody recognizes a band of ∼140 kDa in various cell lines, which shows the same electrophoretic motility of the overexpressed HDAC4 (our unpublished data). Next, we used IMR90-E1A fibroblasts treated with UV to evaluate HDAC4 processing during apoptosis. Processing of HDAC4 to a 97-kDa band similar to the in vitro generated fragment can be specifically observed in UV treated IMR90-E1A cells (Figure 2g). This HDAC4 fragment shows the same electrophoretic motility of the deleted version of HDAC4 (Δ1–289), which corresponds to the caspase-generated carboxy-terminal fragment of HDAC4 (our unpublished data). Appearance of HDAC4 processing is parallel to the activation of caspase-2 and the generation of p85 PARP fragment (Figure 2g). Processing of endogenous HDAC4 during apoptosis occurred in parallel to caspase-2 activation and PARP cleavage, even in Jurkat T cells treated with 40 μM of etoposide (our unpublished data).

To understand the role of different caspases in the cleavage of HDAC4 in vivo, we used cell lines containing defined mutations in caspase-9 and caspase-3. We used MCF-7, a cell line that does not express functional caspase-3 and IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells, which express a dominant negative form of caspase-9 (Fearnhead et al., 1998). For comparison, MCF-7 cells either with caspase-3 WT (C3WT) or with its catalytically inactive form C3CI were used. As shown in Figure 2g, HDAC4 processing can be observed in UV-treated MCF-7/C3WT, but it is undetectable in UV-treated MCF-7/C3CI. As reported previously (Paroni et al., 2001), caspase-2 processing was largely impaired in UV-treated MCF-7C3CI cells, whereas PARP cleavage, even though reduced, was detectable. Similar results were obtained in IMR90-E1A/C9DN where HDAC4, PARP and caspase-2 processing were reduced in response to UV irradiation. To confirm the role of caspase-9 in HDAC4 processing, we incubated IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells with etoposide. As illustrated in Figure 2h, HDAC4 processing in response to etoposide-induced apoptosis was again largely impaired in cells expressing catalytically inactive caspase-9. We also explored the role of caspase-2 in the cleavage of HDAC4 during etoposide-induced apoptosis. Caspase-2 expression was down-regulated by specific siRNA as reported previously (Lassus et al., 2002). HDAC4 cleavage after etoposide treatment was efficiently induced in cells showing reduced levels of caspase-2.

These results suggest that caspase-3 and the mitochondrial pathway are critical in triggering HDAC4 processing after genotoxic stress.

Caspase-2 Cleaves HDAC4 In Vivo in Cells Overexpressing a Caspase-9 Dominant Negative Form

The in vitro studies show that caspase-3 is much more efficient in cleaving HDAC4 than caspase-2. This is not surprising because recombinant caspase-2 has Kcat/Km values for cleavage of its peptide substrate that are 100-1000 lower than those for caspase-3 (Thornberry et al., 1997). Despite this, we decided to use caspase-2 as a tool to induce HDAC4 processing in vivo and thus to study the specific effect of caspases on HDAC4 nuclear/cytosolic shuttling. Caspase-2 is an ideal candidate for this experiment, because when overexpressed, it becomes active after oligomerization mediated by caspase recruitment domain-dependent homotypic interactions. To this aim, we used IMR90-E1AC9DN cells to exclude the amplificatory function of the apoptosome (Paroni et al., 2001). Cells were cotransfected with the HDAC4-GFP or HDAC4/D289E-GFP and caspase-2 wt or the catalytically inactive mutant (CI) caspase-2/C303G (Figure 3a). Cell lysates were produced 24 h later and subjected to Western blot analysis. HDAC4-GFP was efficiently cleaved, generating a carboxy-terminal fragment of the expected size when caspase-2 was coexpressed, whereas when the caspase-2/CI was coexpressed, this cleavage was largely impaired. Similarly to the in vitro cleavage data, when the mutant HDAC4/D289E-GFP was coexpressed with caspase-2, HDAC4 processing was suppressed. We also coexpressed caspase-2 together with HDAC4 fused with GFP at the amino terminus (GFP-HDAC4) to detect the appearance of the amino-terminal cleaved fragment (Figure 3b). As a positive control of caspase-2 activity, we used Bid-GFP (Paroni et al., 2001) (Figure 3c). Cell lysates were analyzed for caspase-2 expression and actin as a loading control. Activation of the ectopically expressed caspase-2 wt can be monitored by the appearance of p32 and p18 forms, whereas processing at p33 can be observed even when caspase-2/CI was expressed.

Figure 3.

Caspase-2 cleaves HDAC4 in cells expressing caspase-9/DN. (a) Cells were transfected with pcDNA3-caspase-2, pcDNA3-caspase-2-C303G, with pEGFPN1-HDAC4, or with pEGFPN1-HDAC4/D289E as indicated. Cell lysates were generated and subjected to Western immunoblotting using anti-GFP, anticaspase-2 and anti-actin antibodies. (b) Cells were transfected with pcDNA3-caspase-2, pcDNA3-caspase-2-C303G, or with pEGFPC2-HDAC4 as indicated. Cell lysates were generated and subjected to Western immunoblotting by using anti-GFP, anti-caspase-2, and anti-actin antibodies. (c) Cells were transfected with pcDNA3-caspase-2, pcDNA3-caspase-2-C303G, or with pEGFPN1-Bid as indicated. Cell lysates were generated and subjected to Western immunoblotting by using anti-GFP, anti-caspase-2, and anti-actin antibodies. (d) Cells were transfected with pcDNA3-caspase-2, pcDNA3-caspase-2-C303G, or with pcDNA3-β-cateninΔ1-134 as indicated. Cell lysates were generated and subjected to Western immunoblotting by using anti-β-catenin and anti-caspase-2 antibodies.

The β-catenin Δ1-134 deleted version, used as a negative control because it is not cleaved by caspase-2 in vitro (our unpublished data), was efficiently cleaved when coexpressed with caspase-2 (Figure 3d); hence, we cannot completely exclude that efficient processing of HDAC4 is an indirect consequence of caspase-2 proteolytic activity.

Caspases Regulate HDAC4 Intracellular Trafficking

Nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling of HDAC4 is mediated by a nuclear localization sequence (NLS) present in the amino-terminal region and by a carboxy-terminal nuclear export sequence (NES) (Miska et al., 1999; McKinsey et al., 2001; Wang et al., 2001) (Figure 2a). To investigate whether caspases could regulate the intracellular trafficking of HDAC4, carboxy-terminal FLAG tagged HDAC4 and the deleted versions corresponding to the caspase cleaved forms were overexpressed in IMR90-E1A cells, and their subcellular localization was investigated by immunofluorescence. As illustrated in Figure 4a, expression of full-length HDAC4 resulted in a cytoplasmic localization in 30–40% of the cells. Expression of the carboxy-terminal fragment HDAC4ΔN, which lacks the NLS and the MEF2 binding region resulted in a cytoplasmic localization in 90% of the cells. In contrast, the amino-terminal fragment HDAC4ΔC, which lacks the NES and the two binding sites for 14-3-3 proteins, showed a nuclear localization in >90% of the cells.

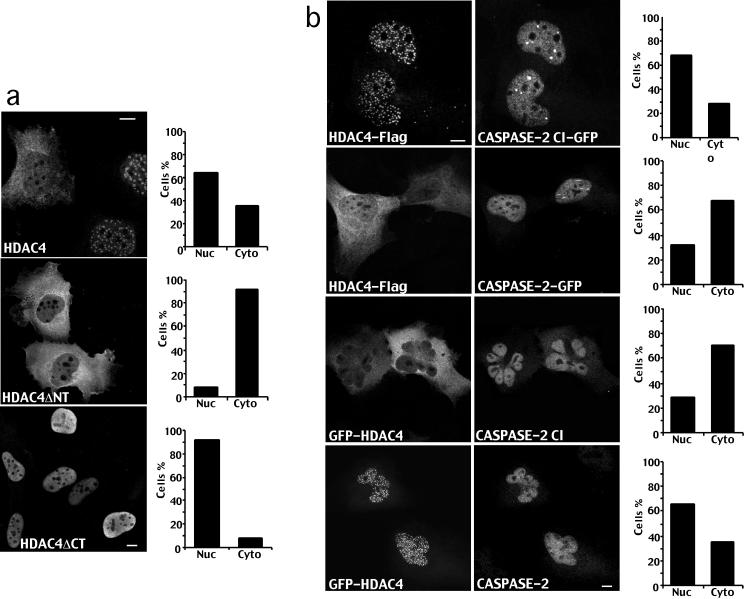

Figure 4.

Caspase-2 regulates the intracellular trafficking of HDAC4. (a) Immunofluorescence analysis of IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells expressing FLAG-tagged full-length HDAC4 and the HDAC4ΔN or HDAC4ΔC deletion derivatives as indicated. Cells after transfection with the relative constructs were fixed and processed for immunofluorescence to visualize HDAC4 by using an anti-FLAG antibody. Bar, 15 μm. Approximately 500 cells were scored for the quantitative analysis reported in the diagrams. (b) Immunofluorescence analysis of IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells coexpressing carboxy-terminal FLAG-tagged full-length HDAC4, GFP-tagged caspase-2 wt or caspase-2/CI, and analysis of cells coexpressing amino-terminal GFP-tagged full-length HDAC4, caspase-2 wt, or caspase-2/CI as indicated. Caspase-2 was visualized by using the specific antibody. Bar, 15 μm. Approximately 500 cells were scored for the quantitative analysis reported in the diagrams.

Next, we coexpressed caspase-2 and HDAC4 in IMR90-E1A/C9DN because caspase-2 cleaves HDAC4 independently from caspase-9 in vivo and, in this cell line, caspase-2 cannot induce a full apoptotic phenotype (Paroni et al., 2002), which renders the morphological analysis more accurate.

As shown in Figure 4b, when caspase-2/CI was coexpressed together with HDAC4, the deacetylase was localized both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm as described above. Coexpression of caspase-2 wt increases the percentage of cells showing accumulation of HDAC4 in the cytoplasm up to 70%, thus suggesting that caspase-2 triggers the accumulation of the HDAC4 carboxy-terminal fragment into the cytoplasm through the processing at Asp 289. Western blot analysis confirmed that 80–90% of HDAC4 was processed by caspase-2 in cells overexpressing both genes (our unpublished data).

To investigate the accumulation in the nucleus of the amino-terminal fragment of HDAC4 upon caspase-2 cleavage, we used an amino-terminus GFP-tagged HDAC4. Overexpression of GFP-HDAC4 in IMR90-E1A leads to a cytoplasmic localization of HDAC4 in 65–75% of cells contrary to carboxy-terminal FLAG-tagged HDAC4, which showed a cytoplasmic localization in 30–40% of the cells. We suggest that this difference could depend on the FLAG that could interfere with the normal presentation of the carboxy-terminal NES.

Figure 4b illustrates that when caspase-2/CI was coexpressed together with GFP-HDAC4, the deacetylase showed a nuclear localization in ∼25% of the transfected cells. On the contrary, when GFP-HDAC4 was coexpressed with caspase-2 wt, the percentage of cells showing accumulation of HDAC4 in the nucleus increased up to 60%, thus suggesting that the amino-terminal fragment of the HDAC4 accumulates into the nucleus after the caspase-2–dependent processing at Asp 289.

In Vivo Analysis of HDAC4 Nuclear/Cytoplasmic Shuttling after Caspase Processing

To confirm that caspase cleavage of HDAC4 can regulate its nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling, we performed a time-lapse analysis. The nuclei of IMR90-E1A/C9DN were microinjected with pcDNA3-caspase-2 and pEGFPC2-HDAC4, and soon after cells were subjected to a time-course analysis. Frames were collected every 2 min during a 12-h period. Selected frames of a representative experiment are shown in Figure 5a. GFP-HDAC4 was initially detected as a diffuse cytoplasmic staining. After a certain time from microinjection, small aggregates in the cytoplasm were evident as described previously (Miska et al., 1999). After 3.39 h from microinjection, initial accumulation of HDAC4 was evident, and the almost complete nuclear translocation of HDAC4 was observed within 40 min. (at 4.20 h from microinjection). Interestingly cytoplasmic aggregates of HDAC4 were dissolved probably as a consequence of the caspase-dependent processing.

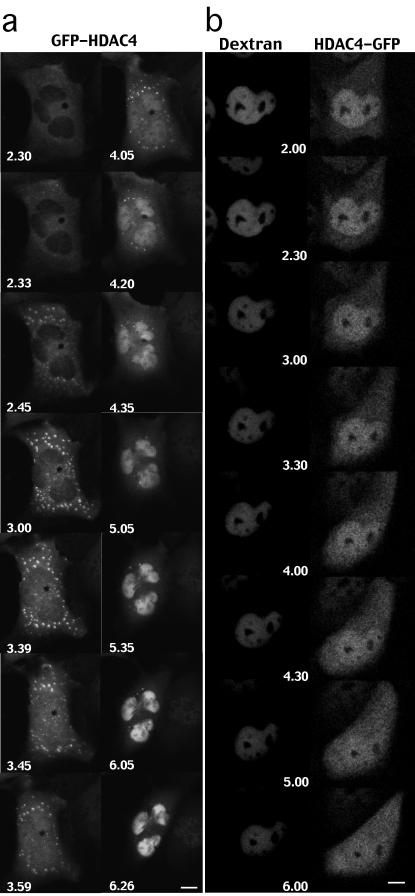

Figure 5.

In vivo analysis of HDAC4 nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling after caspase activation. (a) Time-lapse images of IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells expressing GFP-HDAC4, amino-terminal tagged, and caspase-2. Frames at selected time points after microinjection (as indicated) of a representative cell injected with pEGFPC2-HDAC4 (10 ng/μl) and pcDNA3-caspase-2 (80 ng/μl) are shown. Bar, 15 μm. (b) Time-lapse images of IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells double stained for HDAC4-GFP, carboxy-terminal tagged, and dextran. Frames at selected times after microinjection (as indicated) of a representative cell injected with pEGFP-N1-HDAC4 (10 ng/μl), pcDNA3-caspase-2 (80 ng/μl) and 66-kDa dextran (1 mg/ml) are shown. Bar, 15 μm.

Previous studies have indicated that caspase-2 can alter nuclear permeability independently from caspase-9 (Paroni et al., 2002). To exclude an indirect effect of caspase-2 on HDAC4 nuclear/cytoplasmic trafficking, as a consequence of an alteration on the diffusion limits of the nuclear pores, fluorescent 66-kDa dextran was used to mark the integrity of the nuclear barrier. The nuclei of IMR90-E1A/C9DN were microinjected with pcDNA3-caspase-2, dextran-TRITC 66-kDa and pEGFPN1-HDAC4, and soon after cells were subjected to a time-course analysis. Frames were collected every 2 min during a 12-h period. Selected frames of a representative experiment are shown in Figure 5b. Dextran was well confined in the nucleus even when HDAC4-GFP staining increased in the cytoplasm (Figure 5b, 5.00 h). This cytoplasmic accumulation of HDAC4-GFP became more evident at later times (Figure 5b, 6.00 h), and again TRITC-dextran staining was confined to the nucleus. This result indicates that accumulation of HDAC4-GFP into the cytoplasm is not a consequence of changes in the nuclear barrier integrity.

The Amino-Terminal Fragment of HDAC4 Activates the Intrinsic Apoptotic Pathway

To determine whether caspase cleavage of HDAC4 promotes apoptosis, we transiently cotransfected IMR90-E1A cells with full-length HDAC4, with its deleted amino-(HDAC4ΔN) and carboxy-terminal (HDAC4ΔC) versions, or with P0 as control. GFP was used as a reporter, and the appearance of apoptotic cells was analyzed in vivo 44 h after transfection.

As outlined in Figure 6a, HDAC4ΔC induced cell death, whereas neither the full-length HDAC4 nor the HDAC4ΔN efficiently induced apoptosis in IMR90-E1A cells. The proapoptotic effect of HDAC4ΔC was also observed after its ectopic expression in U2OS cells (our unpublished data).

Figure 6.

The amino-terminal fragment of HDAC4 activates the intrinsic apoptotic pathway. (a) In IMR90-E1A cells, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔN, pFLAG-CMV5-HDAC4ΔC, and pcDNA3-P0 were cotransfected together with pEGFPN1, as a reporter. The appearance of apoptotic cells was scored after 44 h from transfection. Cells showing a collapsed morphology and presenting extensive membrane blebbing were scored as apoptotic. Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for eight independent experiments. (b) In IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔN, pFLAGCM-V5-HDAC4ΔC, and pcDNA3-P0 were cotransfected together with pEGFPN1, as a reporter. The appearance of apoptotic cells was scored after 44 h from transfection. Cells showing a collapsed morphology and presenting extensive membrane blebbing were scored as apoptotic. Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for five independent experiments. (c) In IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4, pFLAGCMV5-HDA-C4ΔN, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔC, and pcDNA3-P0 were cotransfected together with pEGFPN1, as reporter. After 44 h, immunofluorescence assay was performed using anti-cytochrome c antibody and cells were scored for cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for three independent experiments. (d) In IMR90-E1A and in IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔN, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔC and pcDNA3-P0 were cotransfected together with pEGFPN1, as a reporter. Cell lysates were generated and subjected to Western immunoblotting by using the indicated antibodies.

To characterize the apoptotic pathway triggered by HDAC4ΔC, we used IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells that are resistant to different apoptotic insults (Fearnhead et al., 1998). P0, HDAC4, HDAC4ΔC, and HDAC4ΔN were cotransfected in IMR90-E1A/C9DN together with GFP as a reporter, and the appearance of apoptotic cells was scored in vivo 44 h later. As shown in Figure 6b, the ability of HDAC4ΔC to induce cell death was reduced in cells defective for caspase-9. To confirm the role of caspase-9 in the apoptotic pathway triggered by HDAC4ΔC, we took again advantage of IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells to evaluate its effect on the release of cytochrome c into the cytoplasm. Overexpression of HDAC4ΔC was able to trigger cytochrome c release from mitochondria, thus indicating that its overexpression activates the intrinsic apoptotic pathway (Figure 6c).

To confirm the activation of a caspase-9–dependent apoptotic pathway, P0, HDAC4, HDAC4ΔC, and HDAC4ΔN were transfected together with GFP, as a control of transfection efficiency, in IMR90-E1A and IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells. Cells extracts were prepared 44 h later and analyzed for PARP processing. Figure 6d shows that processing of PARP occurred only in IMR90-E1A cells expressing HDAC4ΔC, even though similar levels of the fragments were present in IMR90-E1A/C9DN cells. HDAC4, HDAC4ΔN, and P0 were unable to trigger PARP processing when overexpressed in IMR90-E1A cells. Interestingly, even though transfection efficiency was similar in the different experiments (see GFP levels), HDAC4ΔC was present at higher levels compared with HDAC4 and HDAC4ΔN, thus suggesting that it is more stable. In contrast, HDAC4ΔN was detectable mainly as proteolyzed fragments. This pattern of HDAC4 expression was equally observed in four distinct experiments.

The Amino-Terminal Fragment of HDAC4 (HDAC4ΔC) Acts as a Potent Repressor of MEF2-dependent Transcription

Different studies have established that HDAC4 negatively regulates MEF2-dependent transcription (Wang et al., 1999; Miska et al., 1999; Verdin et al., 2003). Depending from the cellular context, members of the MEF2 family of transcription factors link calcium-dependent signaling pathway to the expression of genes regulating cell division, differentiation, and apoptosis (McKinsey et al., 2002). Therefore, we evaluated whether the proapoptotic function of HDAC4ΔC was coupled to an effect on MEF2 transcriptional activity. HeLa cells were transfected with MEF2C, with a reporter containing three binding sites for MEF2C upstream of the luciferase coding sequence and with expression plasmids for HDAC4, HDAC4ΔC, HDAC4ΔN (Figure 7a). HeLa cells have abundant MEF2 binding site activity, which leads to luciferase expression also in the absence of MEF2C overexpression (Miska et al., 1999; Figure 7c). As shown in Figure 7b, MEF2 reporter can be further activated by exogenous MEF2C. This MEF2C-driven reporter was repressed when HDAC4 was introduced in HeLa cells. In the case of HDAC4ΔC, the repression activity was increased, whereas coexpression of HDAC4ΔN slightly reinforced MEF2C transcription.

Figure 7.

HDAC4ΔC acts as a potent repressor of MEF2C-dependent transcription. (a) Schematic representation of the transfection experiments. (b) HeLa cells were transfected with 3 × -MEF2-Luc reporter (1 μg), internal control pRL-CMV(20 ng), pcDNA3.1-MEF2C (1 μg), pFLAGCMV5 (0.5 μg), and pFLAGCMV5 containing full-length HDAC4 and its deleted derivatives (0.5 μg). TSA (330 nM) was added as indicated. Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for six independent experiments. (c) HeLa cells were transfected with 3 × -MEF2-Luc reporter (1 μg), internal control pRL-CMV(20 ng), pcDNA3.1-MEF2C (1 μg), pFLAGCMV5 (0.5 μg), and pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔC (0.5 μg). Cell lysates were produced at the indicated times. Expression of transfected proteins was verified using Western blotting (our unpublished data). Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for three independent experiments. (d) HeLa cells were transfected with 3 × -MEF2-Luc reporter (1 μg), internal control pRL-CMV(20 ng), pcDNA3.1-MEF2C (1 μg), pFLAGCMV5 (0.5 μg), and pFLAGCMV5 containing full-length HDAC4, HDAC4ΔC, and its deleted derivatives (0.5 μg) as indicated. Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for three independent experiments. (e) In IMR90-E1A cells pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔC/Δ166-184, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4/1-165, pFLAGCMV5-HDAC4ΔC, and pcDNA3-P0 were cotransfected together with pEGFPN1, as a reporter. The appearance of apoptotic cells was scored after 44 h from transfection. Cells showing a collapsed morphology and presenting extensive membrane blebbing were scored as apoptotic. Data represent arithmetic means ± SD for six independent experiments.

Furthermore, the HDAC4-dependent repression was reduced, but it was still present when the cells were treated with TSA, whereas HDAC4ΔC-dependent repression was unaffected by the presence of TSA. The repressive activity of HDAC4ΔC was also confirmed in IMR90-E1A cells (our unpublished data).

Having demonstrated a potent repression activity of the HDAC4ΔC, we next decided to exclude that this repression was not an indirect consequence of its ability to trigger apoptosis. Hence we performed a time-course experiment to evaluate MEF2C transcription in cells coexpressing HDAC4ΔC at early times from transfection when apoptosis was undetectable. As shown in Figure 8c, HDAC4ΔC-dependent repression was seen also at early time-points from transfection thus indicating that it is not a consequence of cell death.

Figure 8.

In vivo analysis of HDAC4 nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling during UV induced cell death. (a) Subcellular localization of HDAC4 in U2OS cells as revealed by biochemical fractionation. Crude nuclear (N) and cytosolic (C) extracts were prepared as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS, and western blots were performed using the indicated antibodies. Histones were visualized by Coomassie Blue staining. (b) Time-lapse images of a representative U2OS/GFP-HDAC4 cell after UV irradiation. Bar, 15 μm. (c) Time-lapse sequences of UV irradiated U2OS/GFP-HDAC4 cells. Each position along the x-axis represents a single cell. • marks translocation of GFP-HDAC4 into the nucleus. ▵ marks evident nuclear fragmentation. (d) Time-lapse images of a representative U2OS/GFP-HDAC4/D289E cell UV irradiated. Bar, 15 μm.

Finally we wanted to explore whether the repression activity of the caspase-cleaved amino-terminal fragment of HDAC4 (HDAC4ΔC) was required to trigger cell death. To this aim we generated a deletion encompassing aa 166–184 and a second deletion lacking aa from 166–289. These deletions were next analyzed for their ability to repress MEF2C transcription. Both deletions were expressed at similar levels but showed a different subcellular distribution when ectopically expressed: HDAC4ΔC/Δ166–184 was localized in the nuclear compartment whereas the HDAC4/1–165 fragment was detectable throughout the cells both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm (data not shown).

HeLa cells were transfected with MEF2C, its reporter, and with expression plasmids for HDAC4ΔC, HDAC4ΔC/Δ166-184, HDAC4/1-165, or an empty vector as a control. The larger deletion (HDAC4/1-165) was unable to repress MEF2C driven reporter, whereas the shorter deletion (HDAC4ΔC/Δ166-184) efficiently repressed MEF2C-dependent transcription. Next, we analyzed these deletions for their ability to trigger cell death. As exemplified in Figure 7e, the amino-terminal fragment (Δ166-184), which retains the transcriptional repressive function, induced cell death similarly to HDAC4ΔC, whereas the deletion 166-289, which avoids any repressive activity, was unable to trigger cell death.

Overall, these data suggest that there is a strong association between the apoptotic function of HDAC4ΔC and its repressional activity.

Nuclear Accumulation of HDAC4ΔC during Apoptosis In Vivo

To investigate HDAC4 nuclear/cytoplasmic trafficking during apoptosis in vivo, we generated U2OS cells stably expressing GFP-HDAC4 and GFP-HDAC4/D289E. As described above for IMR90-E1A cells, GFP-HDAC4 can be localized both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm of U2OS cells, even though the cytosolic localization was prevalent (our unpublished data). The subcellular localization of the endogenous HDAC4 in U2OS, when analyzed by biochemical fractionation, was exclusively cytosolic (Figure 8a), and similar results were obtained in IMR90-E1A cells (our unpublished data).

Next, UV-irradiated U2OS/GFP-HDAC4 cells were subjected to time-lapse analysis. Frames were collected every 3 min for 24 h. The analysis has been focused on cells showing GFP-HDAC4 staining in the cytosol. Selected frames of a representative experiment are shown in Figure 8b. GFP-HDAC4 accumulated into the nucleus in response to UV irradiation, coincidentally/immediately before the retraction response, but clearly before evident nuclear fragmentation. Nuclear accumulation of GFP-HDAC4 was never observed in untreated cells during 36 h of analysis (our unpublished data). Histogram presented in Figure 8c summarizes the results obtained from various experiments where each position along the x-axis represents a single cell.

When the same analysis was performed in U2OS/GFP-HDAC4/D289E cells, we did not observe, at any time, nuclear accumulation of GFP staining after UV irradiation. Selected frames of a representative experiment are shown in Figure 8d.

DISCUSSION

Caspases promote cell death either by the cleavage-dependent inactivation of survival factors or by the cleavage-dependent activation of proapoptotic factors (Cryns and Yuan, 1998). The caspase-dependent turn-off of survival pathways can be attempted at a transcriptional level by the cleavage of transcription factors regulating the expression of prosurvival genes (Fischer et al., 2003). Processing of transcription factors generally results in a drastic decrease of their activity, which suggests that caspases can act as transcriptional corepressors.

HDACs are important regulators of gene expression as part of transcriptional corepressor complexes (Grozinger and Schreiber, 2002; Peterson, 2002; Verdin et al., 2003). Here, we report that caspases can selectively modulate HDACs function during apoptosis. Our evidence demonstrates that HDAC4, but not HDAC1, 2, 3, and 6, is specifically cleaved by caspase-2 and -3 in vitro, whereas HDAC5 is cleaved in vitro by caspase-3, but at a much lower extent with respect to HDAC4.

Experiments in MCF-7 cells expressing caspase-3/CI or caspase-3/WT, and IMR90-E1A cells expressing C9DN, indicate that the apoptosome and the subsequent activation of caspase-3 play the major role in HDAC4 processing after genotoxic stress.

HDAC4 belongs to the class IIa of HDACs and shows the highest expression in heart, skeletal muscle and brain. HDAC4 is part of large multiprotein complexes that mediate its recruitment to specific promoters (Figure 9) (Verdin et al., 2003). HDAC4 interacts with the MEF2 family of transcription factors and with SRF through the amino-terminal region (Miska et al., 1999; Youn et al., 2000; Davis et al., 2003). In addition, the amino-terminal region is also involved in the binding of the transcriptional repressor C-terminal-binding protein (CtBP) and of BCL6, a sequence-specific transcriptional repressor that is involved in the pathogenesis of non-Hodgkin's B-cell lymphomas (Zhang et al., 2001; Lemercier et al., 2002; Verdin et al., 2003).

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the effect of caspase activation on HDAC4 and its partners. Cytoplasmic relocalization of HDAC4 carboxy-terminal fragment could trigger the dissociation from the SMRT/N-CoR–HDAC3 complex (Fischle et al., 2002).

HDAC4 interacts with two closely related corepressors, silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptor (SMRT) and nuclear receptor corepressor (N-CoR), through the carboxy-terminal region, including the HDAC domain (Huang et al., 2000). HDAC4 is enzymatically inactive; however, a deacetylase activity arises from the presence of HDAC3 in the SMRT/N–CoR complex (Fischle et al., 2002). Further HDAC4 partners are represented by heterochromatin protein 1, which mediates transcriptional repression by recruiting histone methyltransferase (Zhang et al., 2002) and by the recent described p53BP1 (Kao et al., 2003).

HDAC4, similarly to other class IIa members, can shuttle in a regulated manner between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, and the phosphorylation-dependent binding to 14-3-3 proteins mediates their cytoplasmic localization (Grozinger and Schreiber, 2000; McKinsey et al., 2000; Wang et al., 2000; Miska et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2001). The Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase and a still unidentified kinase can mediate phosphorylation of HDAC4, 5, 7, and 9 and promote their nuclear export (Verdin et al., 2003).

We demonstrate that HDAC4 nuclear/cytoplasmic shuttling is regulated by caspases. Caspase-dependent cleavage of HDAC4 occurs at Asp 289 and provokes the separation of the amino-terminal region, including the MEF binding sequence and the NLS, from the carboxy-terminal region that includes the HDAC domain and the NES. The corresponding amino-terminal and carboxy-terminal fragments show an exclusively nuclear and cytoplasmic localization, respectively.

Class II HDACs play multiple biological roles being involved in the myogenesis, in the negative selection of thymocyte, in the regulation of Epstain-Barr virus, and probably in neuronal survival (Verdin et al., 2003). The relationships between the subcellular localization of class IIa HDACs and their biological functions have been characterized more in detail during myogenesis. HDAC4, similarly to HDAC5 and 7, when overexpressed in C2C12 cells can accumulate into the nucleus where it represses MEF2-dependent transcription and muscle differentiation (Lu et al., 2000; Miska et al., 2001). However, HDAC4 is mainly cytosolic in proliferating C2C12 cells and relocalizes to the nucleus in myotubes, whereas HDAC5 is prevalently nuclear in myoblasts and translocates into the cytoplasm when cells differentiate (Miska et al., 2001; Zhao et al., 2001).

We similarly observed that HDAC4 is mainly cytosolic in IMR90-E1A and in U2OS cells. In stably transfected U2OS cells, GFP-HDAC4 showed a cytosolic localization in ∼70% of the cells; but during UV-induced apoptosis, it translocates into the nucleus in a caspase-dependent manner, coincidentally/immediately before the retraction response, but clearly before nuclear fragmentation. Overall, our data suggest that HDAC4 translocation into the nucleus during cell death is dependent on a caspase cleavage of the amino-terminal region and that this cleavage is an early event during the execution phase of the apoptotic program.

When ectopically expressed, the amino-terminal fragment of HDAC4 (HDAC4ΔC) induced apoptosis by activating the mitochondrial pathway, as demonstrated by the dependence on caspase-9, the release of cytochrome c, and the processing of PARP. Class IIa HDACs contain multiple, independent repressive domains (Verdin et al., 2003). The amino-terminal region of HDAC4 but also that of HDAC-7 and HDAC-9/MITR are able to repress transcription in the absence of their deacetylase domains (Dressel et al., 2001; Wang et al., 1999; Sparrow et al., 1999; Chan et al., 2003). We observed that the proapoptotic function of HDAC4ΔC was correlated to an efficient repression of MEF2C transcriptional activity. Surprisingly, HDAC4ΔC showed a stronger MEF2-repressive activity compared with the full-length HDAC4. Different explanations can be evoked: 1) HDAC4ΔC shows an exclusively nuclear localization, whereas HDAC4 was nuclear in ∼60% of the cells. 2) The subnuclear localization of the two proteins was different because HDAC4-FLAG, when localized into the nucleus, was present in speckle-like structures (Wu et al., 2001), whereas HDAC4ΔC-FLAG showed a diffuse nuclear staining. 3) From our studies, it seems that HDAC4 lacking the carboxy-terminal region is more stable of the full-length protein. It is possible that all these aspects account for the increased repressive activity of the caspase-cleaved amino-terminal segment of HDAC4.

Removal of aa 166-289 from HDAC4ΔC abolished its repressional activity and the proapoptotic function. These data further support the link between the repressional and the cell death activities of HDAC4. Curiously, the deletion HDAC4ΔC/Δ166-185, which should remove the previously reported MEF2 binding site (Wang and Yang, 2001), was still able to repress MEF2C transcription. Repression of MEF2C by the HDAC4 fragments lacking this putative binding site has already been observed (Wang et al., 1999). Two possible explanations can be evoked: 1) An additional MEF2C binding site could exist in HDAC4ΔC. 2) It could be possible that HDAC4ΔC/Δ166-185 is recruited, through different interactors, to MEF2 promoter independently from the binding to MEF2. Interestingly within the amino-terminal region of HDAC4 an oligomerization domain has been mapped (Wang and Yang, 2001; Kirsh et al., 2002). Therefore, HDAC4ΔC/Δ166-185 could interact with endogenous HDAC4 and be recruited in the complex containing MEF2C.

Diverse cellular decisions are controlled by the MEF2 family of transcription factors in different cell types (McKinsey et al., 2002), including proapoptotic (Youn et al., 1999) and prosurvival functions (Mao et al., 1999). Protection from apoptosis has been observed in postmitotic neurons. RNA interference on MEF2A, revealed a critical role of this factor in the neuronal activity-dependent survival of granule neurons (Gaudilliere et al., 2002). Moreover, when the same cells were challenged to apoptosis by K+ withdrawal, MEF2A and MEF2D underwent a caspase-mediated processing (Li et al., 2001). Caspase-dependent processing of MEF2 family members has also been investigated in mature cerebrocortical neurons in response to excitotoxic insults. In this cellular system, the caspase-dependent cleavage of MEF2 transcription factors generates fragments that act in a dominant-interfering manner to abrogate MEF2-dependent neuroprotection (Okamoto et al., 2002). Similarly caspase-dependent cleavage of SRF, another prosurvival factor that is regulated by HDAC4, inhibits its transcriptional activity (Bertolotto et al., 2000; Drewett et al., 2001).

This evidence suggests that caspases act in coordinated manner to suppress the survival pathways regulated by SRF and MEF2 transcription factors both in “cis” by the direct cleavage of the transcription factors and in “trans” by regulating HDAC4 function. In this scenario, when a limited level of caspases is activated by mitochondria, HDAC4 cleavage could sustain the apoptotic signal by acting on mitochondria in a sort of amplificatory loop.

Interestingly ectopically expressed HDAC5 promotes apoptosis (Huang et al., 2002), and in a transgenic mouse model the inducible expression of a signal resistant form of HDAC5 in cardiomyocytes resulted in sudden death of the mice. Cardiomyocytes death and dramatic changes in mitochondrial morphology were observed (Czubryt et al., 2003). MEF2 and HDAC5 regulate in an opposite manner peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) expression, a master regulator of mitochondria biogenesis (Puigserver et al., 1998; Wu et al., 1999). Because HDAC4ΔC controls cell survival through the mitochondrial pathway, it will be interesting to evaluate whether PCG-1α expression is modulated by HDAC4ΔC and whether PCG-1α can counteract apoptosis induced by this deletion.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. Seto, (University of South Florida, Tampa, FL), T. Kouzarides (University of Cambridge, Cambridge, United Kingdom), C. Grozinger andS.L. Schreiber (Harvard University, Boston, MA) for the expression plasmids encoding the different HDACs. We also thank S. Goruppi (Tufts-New England Medical Center, Boston, MA) and S. Ferrari (Universitá di Modena e Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy) for MEF2C expression plasmid and Luc reporter and E. di Centa (Universitá di Udine, Udine, Italy) for DNA sequencing. Our work is supported by grants from Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro and Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche-Ministero dell'Istruzione, dell'Università e della Ricerca progetto COMETA. G.P. received a fellowship from the Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0624. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E03-08-0624.

Abbreviations used: C9DN, caspase-9 dominant negative; CtBP, C-terminal binding protein; HDAC, histone deacetylase; MEF, myocyte enhancer factor; NES, nuclear export sequence; NLS, nuclear localization sequence; NEO, neomycin; N-CoR, nuclear receptor corepressor; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α, (PGC-1α); SRF, serum response factor, (SRF); SMRT, silencing mediator for retinoid and thyroid receptor.

References

- Ajiro, K. (2000). Histone H2B phosphorylation in mammalian apoptotic cells. An association with DNA fragmentation. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 439-443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baliga, B.C., Colussi, P.A., Read, S.H., Dias, M.M., Jans, D.A., and Kumar, S. (2003). Role of prodomain in importin-mediated nuclear localization and activation of caspase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4899-4905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertolotto, C., Ricci, J.E., Luciano, F., Mari, B., Chambard, J.C., and Auberger, P. (2000). Cleavage of the serum response factor during death receptor-induced apoptosis results in an inhibition of the c-FOS promoter transcriptional activity. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 12941-12947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borghi, S., Molinari, S., Razzini, G., Parise, F., Battini, R., and Ferrari, S. (2001). The nuclear localization domain of the MEF2 family of transcription factors shows member-specific features and mediates the nuclear import of histone deacetylase 4. J. Cell Sci. 114, 4477-4483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, J.K., Sun, L., Yang, X.J., Zhu, G., and Wu, Z. (2003). Functional characterization of an amino-terminal region of HDAC4 that possesses MEF2 binding and transcriptional repressive activity. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23515-23521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheung, et al. (2003). Apoptotic phosphorylation of histone H2B is mediated by mammalian sterile twenty kinase. Cell 113, 507-517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charvet, C., Alberti, I., Luciano, F., Jacquel, A., Bernard, A., Auberger, P., and Deckert, M. (2003). Proteolytic regulation of Forkhead transcription factor FOXO3a by caspase-3-like proteases. Oncogene 22, 4557-4568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cryns, V., and Yuan, J. (1998). Proteases to die for. Genes Dev. 12, 1551-1570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czubryt, M.P., McAnally, J., Fishman, G.I., and Olson, E.N. (2003). Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1 alpha (PGC-1 alpha) and mitochondrial function by MEF2 and HDAC5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 1711-1716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, F.J., Gupta, M., Camoretti-Mercado, B., Schwartz, R.J., and Gupta, M.P. (2003). Calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase activates serum response factor transcription activity by its dissociation from histone deacetylase, HDAC 4, Implications in cardiac muscle gene regulation during hypertrophy. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 20047-20058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drewett, V., Devitt, A., Saxton, J., Portman, N., Greaney, P., Cheong, N.E., Alnemri, T.F., Alnemri, E., and Shaw, P.E. (2001). Serum response factor cleavage by caspases 3 and 7 linked to apoptosis in human BJAB cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 33444-33451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dressel, U., Bailey, P.J., Wang, S.C., Downes, M., Evans, R.M., and Muscat, G.E. (2001). A dynamic role for HDAC7 in MEF2-mediated muscle differentiation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 17007-17013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnhead, H.O., Rodriguez, J., Govek, E.E., Guo, W., Kobayashi, R., Hannon, G., and Lazebnik, Y.A. (1998). Oncogene-dependent apoptosis is mediated by caspase-9. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 13664-13669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, U., Janicke, R.U., and Schulze-Osthoff, K. (2003). Many cuts to ruin: a comprehensive update of caspase substrates. Cell Death Differ. 10, 76-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischle, W., Dequiedt, F., Hendzel, M.J., Guenther, M.G., Lazar, M.A., Voelter, W., and Verdin, E. (2002). Enzymatic activity associated with class II HDACs is dependent on a multiprotein complex containing HDAC3 and SMRT/N-CoR. Mol. Cell 9, 45-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francois, F., Godinho, M.J., and Grimes, M.L. (2000). CREB is cleaved by caspases during neural cell apoptosis. FEBS Lett. 486, 281-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudilliere, B., Shi, Y., and Bonni, A. (2002). RNA interference reveals a requirement for myocyte enhancer factor 2A in activity-dependent neuronal survival. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 46442-4646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozinger, C.M., and Schreiber, S.L. (2000). Regulation of histone deacetylase 4 and 5 and transcriptional activity by 14-3-3-dependent cellular localization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 7835-7840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grozinger, C.M., and Schreiber, S.L. (2002). Deacetylase enzymes: biological functions and the use of small-molecule inhibitors. Chem. Biol. 9, 3-16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kao, G.D., McKenna, W.G,. Guenther, M.G., Muschel, R.J., Lazar, M.A., and Yen, T.J. (2003). Histone deacetylase 4 interacts with 53BP1 to mediate the DNA damage response. J. Cell Biol. 160, 1017-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirsh, O., et al. (2002). The SUMO E3 ligase RanBP2 promotes modification of the HDAC4 deacetylase. EMBO J. 21, 2682-2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg, R.D., and Lorch, Y. (2002). Chromatin and transcription: where do we go from here. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 249-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kratzmeier, M., Albig, W., Hanecke, K., and Doenecke, D. (2000). Rapid dephosphorylation of H1 histones after apoptosis induction. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 30478-30486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassig, C.A., and Schreiber, S.L. (1997). Nuclear histone acetylases and deacetylases and transcriptional regulation: HATs off to HDACs. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 1, 300-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson, C., Mizzau, M., Paroni, G., Maestro, R., Schneider, C., and Brancolini, C. (2003). Role of caspases, Bid, and p53 in the apoptotic response triggered by histone deacetylase inhibitors trichostatin-A (TSA) and suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA). J. Biol. Chem. 278, 12579-12589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, E.Y., Zhang, J., Miska, E.A., Guenther, M.G., Kouzarides, T., and Lazar, M.A. (2000). Nuclear receptor corepressors partner with class II histone deacetylases in a Sin3-independent repression pathway. Genes Dev. 14, 45-54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, Y., Tan, M., Gosink, M., Wang, K.K., and Sun, Y. (2002). Histone deacetylase 5 is not a p53 target gene, but its overexpression inhibits tumor cell growth and induces apoptosis. Cancer Res. 62, 2913-2922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lassus, P., Opitz-Araya, X., and Lazebnik, Y. (2002). Requirement for caspase-2 in stress-induced apoptosis before mitochondrial permeabilization. Science 297, 1352-1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemercier, C., Brocard, M.P., Puvion-Dutilleul, F., Kao, H.Y., Albagli, O., and Khochbin, S. (2002). Class II histone deacetylases are directly recruited by BCL6 transcriptional repressor. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 22045-22052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, M., Linseman, D.A., Allen, M.P., Meintzer, M.K., Wang, X., Laessig, T., Wierman, M.E., and Heidenreich, K.A. (2001). Myocyte enhancer factor 2A and 2D undergo phosphorylation and caspase-mediated degradation during apoptosis of rat cerebellar granule neurons. J. Neurosci. 21, 6544-6552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, J., McKinsey, T.A., Zhang, C.L., and Olson, E.N. (2000). Regulation of skeletal myogenesis by association of the MEF2 transcription factor with class II histone deacetylases. Mol. Cell. 6, 233-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao, Z., Bonni, A., Xia, F., Nadal-Vicens, M., and Greenberg, M.E. (1999). Neuronal activity-dependent cell survival mediated by transcription factor MEF2. Science 286, 785-790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey, T.A., Zhang, C.L., and Olson, E.N. (2000). Activation of the myocyte enhancer factor-2 transcription factor by calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase-stimulated binding of 14–3-3 to histone deacetylase 5. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 14400-14405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey, T.A., Zhang, C.L., and Olson, E.N. (2001). Identification of a signal-responsive nuclear export sequence in class II histone deacetylases. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 6312-6321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKinsey, T.A., Zhang, C.L., and Olson, E.N. (2002). MEF 2, a calcium-dependent regulator of cell division, differentiation and death. Trends Biochem. Sci. 27, 40-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miska, E.A., Karlsson, C., Langley, E., Nielsen, S.J., Pines, J., and Kouzarides, T. (1999). HDAC4 deacetylase associates with and represses the MEF2 transcription factor. EMBO J. 18, 5099-5107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miska, E.A., Langley, E., Wolf, D., Karlsson, C., Pines, J., and Kouzarides, T. (2001). Differential localization of HDAC4 orchestrates muscle differentiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 3439-3447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto, S., Li, Z., Ju, C., Scholzke, M.N., Mathews, E., Cui, J., Salvesen, G.S., Bossy-Wetzel, E., and Lipton, S.A. (2002). Dominant-interfering forms of MEF2 generated by caspase cleavage contribute to NMDA-induced neuronal apoptosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99, 3974-3979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsubo, T., Kamada, S., Mikami, T., Murakami, H., and Tsujimoto, Y. (1999). Identification of NRF2, a member of the NF-E2 family of transcription factors, as a substrate for caspase-3(-like) proteases. Cell Death Differ. 6, 865-872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paroni, G., Henderson, C., Schneider, C., and Brancolini, C. (2002). Caspase-2 can trigger cytochrome C release and apoptosis from the nucleus. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 15147-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paroni, G., Henderson, C., Schneider, C., and Brancolini, C. (2001). Caspase-2-induced apoptosis is dependent on caspase-9, but its processing during UV- or tumor necrosis factor-dependent cell death requires caspase-3. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21907-21915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.L. (2002). HDAC's at work: everyone doing their part. Mol. Cell. 9, 921-922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puigserver, P., Wu, Z., Park, C.W., Graves, R., Wright, M., and Spiegelman, B.M. (1998). A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell 92, 829-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogakou, E.P., Nieves-Neira, W., Boon, C., Pommier, Y., and Bonner, W.M. (2000). Initiation of DNA fragmentation during apoptosis induces phosphorylation of H2AX histone at serine 139. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 9390-9395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Y.,. (2002). Mechanisms of caspase activation and inhibition during apoptosis. Mol. Cell. 9, 459-470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow, D.B., Miska, E.A., Langley, E., Reynaud-Deonauth, S., Kotecha, S., Towers, N., Spohr, G., Kouzarides, T., and Mohun, T.J. (1999). MEF-2 function is modified by a novel co-repressor, MITR. EMBO J. 18, 5085-5098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry, N.A., et al. (1997). A combinatorial approach defines specificities of members of the caspase family and granzyme B. Functional relationships established for key mediators of apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17907-17911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdin, E., Dequiedt, F., and Kasler, H.G. (2003). Class II histone deacetylases: versatile regulators. Trends. Genet. 19, 286-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.H., Bertos, N.R., Vezmar, M., Pelletier, N., Crosato, M., Heng, H.H., Th'ng, J., Han, J., and Yang, X.J. (1999). HDAC4, a human histone deacetylase related to yeast HDA1, is a transcriptional corepressor. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 7816-7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.H., Kruhlak, M.J., Wu, J., Bertos, N.R., Vezmar, M., Posner, B.I., Bazett-Jones, D.P., and Yang, X.J. (2000). Regulation of histone deacetylase 4 by binding of 14–3-3 proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 6904-6912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.H., and Yang, X.J. (2001). Histone deacetylase 4 possesses intrinsic nuclear import and export signals. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 5992-6005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring, P., Khan, T., and Sjaarda, A. (1997). Apoptosis induced by gliotoxin is preceded by phosphorylation of histone H3 and enhanced sensitivity of chromatin to nuclease digestion. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 17929-17936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock, C.L., and Dimitrov, S. (2001). Higher-order structure of chromatin and chromosomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11, 130-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X., Li, H., Park, E.J., and Chen, J.D. (2001). SMRTE inhibits MEF2C transcriptional activation by targeting HDAC4 and 5 to nuclear domains. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 24177-24185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z., et al. (1999). Mechanisms controlling mitochondrial biogenesis and respiration through the thermogenic coactivator PGC-1. Cell 98, 115-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn, H.D., Sun, L., Prywes, R., and Liu, J.O. (1999). Apoptosis of T cells mediated by Ca2+-induced release of the transcription factor MEF2. Science 286, 790-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youn, H.D., Grozinger, C.M., and Liu, J.O. (2000). Calcium regulates transcriptional repression of myocyte enhancer factor 2 by histone deacetylase 4. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 22563-22567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.L., McKinsey, T.A., Lu, J.R., and Olson, E.N. (2001). Association of COOH-terminal-binding protein (CtBP) and MEF2-interacting transcription repressor (MITR) contributes to transcriptional repression of the MEF2 transcription factor. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.L., McKinsey, T.A., and Olson, E.N. (2002). Association of class II histone deacetylases with heterochromatin protein 1, potential role for histone methylation in control of muscle differentiation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7302-7312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X., Ito, A., Kane, C.D., Liao, T.S., Bolger, T.A., Lemrow, S.M., Means, A.R., and Yao, T.P. (2001). The modular nature of histone deacetylase HDAC4 confers phosphorylation-dependent intracellular trafficking. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35042-35048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]