Abstract

Endothelial cell survival and antiapoptotic pathways, including those stimulated by extracellular matrix, are critical regulators of vasculogenesis, angiogenesis, endothelial repair, and shear-stress-induced endothelial activation. One of these pathways is mediated by αvβ3 integrin ligation, downstream activation of nuclear factor-κB, and subsequent up-regulation of osteoprotegerin (OPG). In this study, the mechanism by which OPG protects endothelial cells from death was examined. Serum-starved human microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs) plated on the αvβ3 ligand osteopontin were protected from cell death. Immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that OPG formed a complex with tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) in HMECs under these conditions. Furthermore, inhibitors of TRAIL, including recombinant soluble TRAIL receptors and a neutralizing antibody against TRAIL, blocked apoptosis of serum-starved HMECs plated on the nonintegrin attachment factor poly-d-lysine. Whereas TRAIL was unable to induce apoptosis in HMECs plated on osteopontin, the addition of recombinant TRAIL did increase the percentage of apoptotic HMECs plated on poly-d-lysine. This evidence indicates that OPG blocks endothelial cell apoptosis through binding TRAIL and preventing its interaction with death-inducing TRAIL-receptors

INTRODUCTION

Endothelial apoptosis is an important regulator of angiogenesis, vasculogenesis, vascular pruning, and shear stress-induced endothelial activation (Dimmeler et al., 1996; Dimmeler and Zeiher, 2000). Angiogenesis, the formation of capillaries from preexistent blood vessels is an essential process in development, reproduction, and tissue repair but also occurs in the adult under pathological conditions such as ischemic disease, arthritis, and the growth of solid tumors. Many angiogenic factors, including vascular endothelial growth factor, angiopoietin-1, and basic fibroblast growth factor, act in part by promoting endothelial cell survival or inhibiting endothelial cell apoptosis (Alon et al., 1995; Karsan et al., 1997; Hayes et al., 1999; Kwak et al., 1999). The interaction of endothelial cells and extracellular matrix through integrins also has been found to be important for cell survival (Meredith et al., 1993). The ligation of αvβ3 integrin has been implicated in angiogenesis because studies using neutralizing antibodies or cyclic peptide antagonists induced endothelial cell apoptosis and thereby blocked angiogenesis (Brooks et al., 1994a,b; Friedlander et al., 1996). A potential mechanism for αvβ3-mediated survival in endothelial cells was identified using rat aortic endothelial cells (RAECs) (Scatena et al., 1998). In that study, the αvβ3 ligand osteopontin (OPN) protected RAECs from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis by activating a nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB)-dependent survival pathway. NF-κB-dependent, antiapoptotic genes in RAECs were subsequently identified using subtractive hybridization (Malyankar et al., 2000). Osteoprotegerin (OPG) was identified as one of the induced genes and was shown to have increased mRNA and protein levels in RAECs plated on OPN. The addition of recombinant OPG to RAECs with inactive NF-κB prevented apoptosis in a dose-dependent manner, thus implicating OPG as a downstream mediator of αvβ3-mediated survival.

OPG is a secreted glycoprotein that exists as both a 60-kDa monomer and a 120-kDa disulfide-linked dimer and is a soluble member of the tumor necrosis factor (TNF) receptor superfamily (Simonet et al., 1997). In bone, OPG inhibits osteoclastogenesis by binding receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB ligand (RANKL) and thereby prevents the interaction of receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB (RANK) and RANKL (Lacey et al., 1998; Yasuda et al., 1998). Consistent with this, transgenic mice overexpressing OPG have decreased numbers of osteoclasts and a corresponding increase in the amount of bone (Simonet et al., 1997). Likewise, OPG-deficient mice have decreased bone density (Bucay et al., 1998; Mizuno et al., 1998; Yun et al., 2001). OPG also was found to regulate B cell maturation and development; populations of peripheral B cells are elevated in OPG null mice and OPG null dendritic cells (ex vivo) have an increased ability to stimulate T cells (Yun et al., 2001). Most relevant to the present studies, OPG has been implicated as a mediator of cell survival. Indeed, OPG has been shown to bind TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) and thereby inhibit TRAIL-induced apoptosis of Jurkat cells (Emery et al., 1998).

In the present study, we investigated the mechanism by which OPG acts as a survival factor in endothelial cells. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that OPG binds TRAIL and thereby prevents apoptosis of serum-starved human microvascular endothelial cells (HMECs). Our studies suggest that OPG inhibits serum starvation-induced endothelial apoptosis by binding TRAIL and preventing TRAIL receptor-induced death. Furthermore, the studies suggest that endothelial cells are sensitized to TRAIL-induced death by serum and adhesion deprivation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Human dermal microvascular endothelial cells and EGM-2-MV media were purchased from Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville (Walkersville, MD). Recombinant rat OPN was prepared as described previously (Martin et al., 2003). Antibodies against OPG and TRAIL and the soluble TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 fusion proteins were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). Recombinant TRAIL was purchased from Upstate Biotechnology (Waltham, MA). Polyvinylidene difluoride membranes and Renaissance chemiluminescence reagents were purchased from PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences (Boston, MA). Zetaprobe GT membranes were purchased from Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA). The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit was purchased from Biomedica Gruppe (Southbridge, MA) and the Seize primary immunoprecipitation kit was purchased from Pierce Chemical (Rockford, IL).

Hoechst Staining

Cells were plated onto four-well chamber slides at ∼75% confluence. A 1 in 10 dilution was made from a concentrated stock of Hoechst dye (4 mg/ml). Fifty microliters of the diluted dye was added to each well to make a final concentration of 4 μg/ml in the media. The dye was incubated on the cells for 30 min at 37°C. The media were then removed, the cells rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde. The cells were then washed three times with PBS, coverslipped with Vectashield mounting media, and sealed with varnish. The slides were then examined by fluorescence microscopy for punctate nuclear staining and rounded nuclei indicative of apoptosis.

Northern Blot Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from HMECs plated on poly-d-lysine (PDL) and OPN for 3 and 6 h. Northern blot analysis was carried out by electrophoretic separation of 12.5 μg of total RNA by using formaldehyde-agarose gels and subsequent transfer to a Zetaprobe GT membrane. The OPG cDNA insert was labeled using the Multiprime kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) and [α-32P]dCTP, whereas the 18S probe was end-labeled using T4 kinase (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) and [γ-32P]dATP; hybridization was performed as described previously (Giachelli et al., 1991).

OPG ELISA

Media from HMEC plated on PDL or OPN for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h was collected and concentrated 20-fold by using Microcon filters (10-kDa molecular weight cutoff) (Amicon, Beverly, MA). A volume of 50 μl of concentrated media was added to each well, and the plate was incubated overnight at 4°C. Substrate and conjugate were added according to the manufacturer's instructions, and the absorbance was read at 450 nm. OPG concentrations were determined by interpolation from a standard curve generated with recombinant human OPG.

Immunoprecipitation

HMECs were plated on OPN or PDL coated plates for 24 h. The cells were then lysed in an immunoprecipitation (IP) buffer containing 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 0.5 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, and 0.2 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride. Media also were collected, the cells spun down at 15,000 rpm for 5 min, and added to 10× IP buffer. Antibody (monoclonal anti-TRAIL) or mouse IgG was immobilized onto agarose gel by using sodium cyanoborohydride as directed by the Seize primary immunoprecipitation kit instructions. The antibody conjugate was washed and stored overnight. Immunoprecipitation was carried out in IP buffer; samples were rotated overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed four times with 500 μl of buffer containing 0.025 M Tris, pH 7.2, and 0.15 M NaCl and eluted three times in 50 μl of Immunopure IgG elution buffer. Then, 12.5 μl of 5× sample buffer and 4 μl of 1 M dithiothreitol were added to each sample before boiling for 5 min followed by separation on 12.5% SDS-PAGE gels.

Western Blot Analysis

SDS-PAGE (12.5%) gels were run and subsequently transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. The membranes were then blocked in 10% milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween 20 overnight at 4°C. Primary antibodies were added for 2 h at room temperature followed by the appropriate horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary at a dilution of 1:2500. Membranes were exposed to chemiluminescence reagents for 1 min, and bands were detected by exposing the membrane to x-ray film.

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting (FACS) Analysis

HMECs were plated on bovine serum albumin (BSA) or OPN for 4 h, trypsinized, and resuspended in PBS/0.2% BSA/0.02% NaN3 containing 10 μg/ml anti-TRAIL-R1, anti-TRAIL-R2, anti-TRAIL-R3, or anti-TRAIL-R4 antibody or 10 μg/ml goat IgG. The cells were incubated on ice for 30 min and subsequently incubated for 30 min on ice with a 1:50 dilution of a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled rabbit anti-goat secondary antibody. The cells were then analyzed using flow cytometry at the Cell Analysis Facility (Department of Immunology, University of Washington).

RESULTS

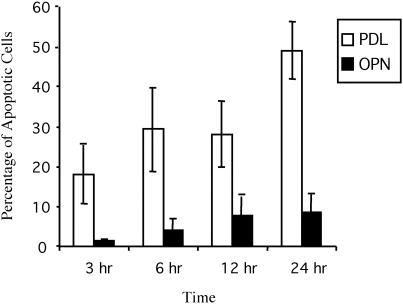

Osteopontin Promotes the Survival of HMECs in the Absence of Serum

Previous studies have demonstrated that OPN protects RAECs from serum deprivation-induced apoptosis through its interaction with the αvβ3 integrin and the subsequent activation of NF-κB (Scatena et al., 1998). OPG was subsequently identified as an NF-κB–dependent survival factor for the RAECs (Malyankar et al., 2000). To determine whether HMECs also survived on osteopontin through the production of OPG, HMECs were plated on PDL and OPN for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h. HMECs bind to PDL through charge-charge interactions, but cell surface integrins are not engaged, resulting in no NF-κB activation. HMECs were then stained with Hoechst, and the number of apoptotic cells was determined (Figure 1). At 3 h, 18% of the HMECs plated on PDL were apoptotic (compared with 1.6% plated on OPN). This increased to 49.1% by 24 h, whereas only 8.6% of HMECs plated on OPN were apoptotic. Therefore, consistent with studies in RAECs, OPN promotes the survival of HMECs in the absence of growth factors.

Figure 1.

HMEC survival is increased in cells plated on OPN compared with PDL. HMECs were plated on either OPN or PDL in the absence of serum for 3, 6, 12, or 24 h. Nuclei were then stained with Hoechst dye, and the number of apoptotic cells was determined in three fields at 40×. The percentage of apoptotic cells was then calculated. Cells were considered to be apoptotic on the basis of nuclear condensation and fragmentation. The experiment was repeated three times, and error bars indicate standard deviations for triplicate determinations (analysis of variance, p < 0.0001).

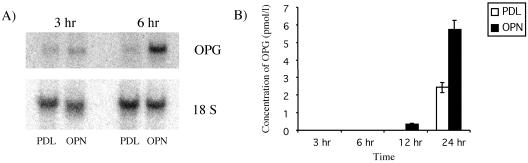

OPN Promotes OPG Synthesis and Secretion

To determine whether OPN promotes the survival of HMECs through the production of OPG, cells were plated on PDL and OPN for 3 and 6 h, and RNA was isolated. Northern blot analysis was carried out using a probe for OPG (Figure 2A). Increased OPG RNA was detected from HMECs plated on OPN at 3 h, and a further increase was found at 6 h. This increase in OPG RNA suggests that OPG may act to promote the survival of these cells in the absence of growth factors.

Figure 2.

OPG RNA and secretion into the media are increased in HMECs plated on OPN. (A) HMECs were plated on either OPN or PDL for 3 and 6 h and the RNA isolated. The samples were run on an agarose gel, and Northern blot analysis was performed. OPG RNA from HMECs plated on OPN was increased at 3 h and was further increased at 6 h. (B) HMECs were plated on either OPN or PDL for 3, 6, 12, or 24 h, and the media were collected and stored at -20°C. The media were concentrated 20-fold by using Microcon filters, and the amount of OPG was quantitated using a sandwich ELISA. A twofold increase in OPG was found in HMECs plated on OPN at 12 and 24 h. Results are representative of three independent experiments; error bars represent standard deviations (analysis of variance, p < 0.0001; three replicates).

Because OPG functions as an extracellular molecule, we investigated the amount of OPG secreted into the media at 3, 6, 12, and 24 h of incubation on OPN. The media were collected and concentrated 20-fold by using Microcon filters. HMECs plated on OPN secreted two times more OPG into the media as cells plated on PDL (Figure 2B). Using the standard curve to interpolate the absorbance of the samples at 24 h, it was found that HMEC plated on OPN secreted 5.7 pmol/l OPG compared with 2.4 pmol/l on PDL. Although the levels of OPG are increased in HMECs plated on PDL at 24 h, these levels do not seem to be protective. Several explanations are possible; the increased levels of OPG may be too late to inhibit the progression of apoptosis or alternately OPN may initiate other synergistic survival pathways not induced on PDL.

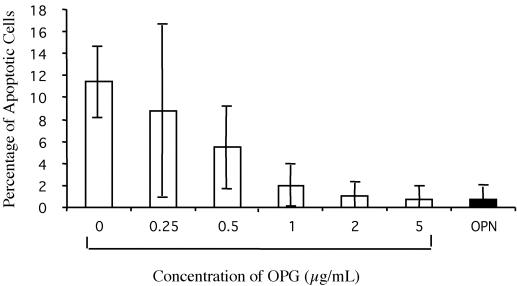

Recombinant OPG Prevents Apoptosis of HMECs Plated on PDL in the Absence of Serum

Recombinant OPG inhibits RAEC apoptosis when NF-κB is inactive (Malyankar et al., 2000). HMECs were plated on PDL for 10 h in the presence of OPG-Fc at concentrations ranging from 0 to 5 μg/ml and on OPN (Figure 3). Apoptotic nuclei were stained and counted as described previously, and the percentage of apoptotic cells was calculated. At 0.5 μg/ml, the percentage of apoptotic cells was reduced by one-half, and this was further decreased at higher concentrations of OPG-Fc. Thus, OPG-Fc inhibits apoptosis of HMECs in a dose-dependent manner.

Figure 3.

Recombinant OPG-Fc inhibits apoptosis of HMECs. HMECs were plated on PDL for 10 h in the presence of OPG-Fc concentrations ranging from 0 to 5 μg/ml and on OPN. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst dye and counted in three fields at 40×. The percentage of apoptotic nuclei was then determined. The experiment was repeated three times, and error bars indicate standard deviations (analysis of variance, p < 0.0001; three replicates).

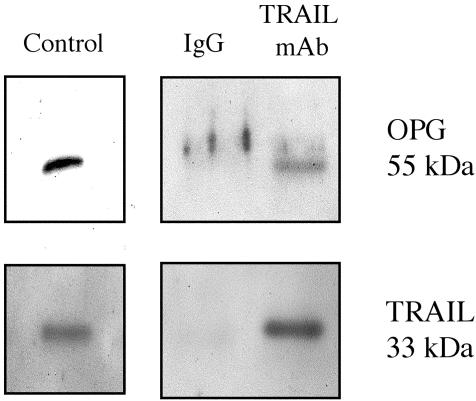

TRAIL and OPG Are Coimmunoprecipitated by a Monoclonal Antibody (mAb) against TRAIL

Because OPG has been found to bind to TRAIL and inhibit the apoptosis of Jurkat cells (Emery et al., 1998), we were interested in determining whether OPG bound TRAIL in HMECs and thereby inhibited serum-induced apoptosis. The amount of TRAIL protein was measured by Western blot in HMECs plated on OPN compared with HMECs plated on PDL and was not found to be changed (our unpublished data), demonstrating that only OPG is upregulated by OPN adhesion. FACS analysis using an anti-TRAIL antibody also indicated that no differences existed in the amount of cell surface TRAIL between surviving HMECs (plated on OPN) and apoptotic HMECs (plated on BSA) (our unpublished data).

To isolate the complex of OPG and TRAIL, HMECs were plated on OPN for 16 h, and the lysates were collected in an IP buffer. A mAb against TRAIL was cross-linked to agarose gel by using sodium cyanoborohydride. This antibody conjugate was then incubated with the cell lysates at 4°C over-night and subsequently washed with IP buffer. The proteins were eluted off the agarose gel in three fractions. Each fraction was loaded separately onto a 12.5% SDS-PAGE gel and then analyzed by Western blot. Both TRAIL and OPG were detected in the eluted fractions. Recombinant TRAIL and OPG were loaded as positive controls. This result indicated that TRAIL and OPG form a complex in the lysates of HMECs plated on OPN, which can be immunoprecipitated using an anti-TRAIL antibody (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

TRAIL and OPG coimmunoprecipitate. HMECs were plated on OPN for 16 h, and the lysates were collected in an IP buffer. Mouse IgG and a mAb against TRAIL were each cross-linked to agarose, and each conjugate was then incubated with the cell lysates at 4°C overnight. The bound proteins were eluted off the agarose gel and analyzed by Western blot. Both TRAIL and OPG were detected in the eluted fractions. Recombinant TRAIL and OPG were loaded as positive controls. This result indicated that TRAIL and OPG form a complex that can be immunoprecipitated using an anti-TRAIL antibody. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Soluble TRAIL-Receptors and Anti-TRAIL Neutralizing Antibody Inhibit HMEC Apoptosis Induced by the Absence of Serum

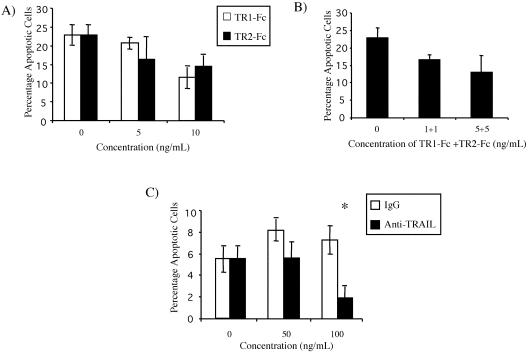

Because OPG, a TRAIL-binding molecule, inhibited the apoptosis of HMECs due to serum deprivation, we used two different approaches to investigate the role of TRAIL in HMEC apoptosis. First, the effect of recombinant soluble TRAIL receptor-Fc fusion proteins for TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 (designated TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc respectively) was investigated. HMECs were plated on PDL for 18 h; TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc were added at 0, 5, and 10 ng/ml to cells plated on PDL (Figure 5A). Both TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc inhibited serum-induced apoptosis of HMECs. Treating HMEC with a combination of TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc did not result in increased inhibition (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Soluble TRAIL receptors and neutralizing antibody against TRAIL promotes HMEC survival. (A) HMECs were plated on OPN or PDL for 18 h. TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc were added at concentrations of 0, 5, and 10 ng/ml to cells plated on PDL. Both TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc inhibited serum withdrawal-induced apoptosis (analysis of variance, p < 0.003; three replicates). (B) Treatment of HMECs with a combination of TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc did not result in increased inhibition. (C) Similarly, HMECs were plated on PDL in the presence of a neutralizing monoclonal anti-TRAIL at concentrations of 50 and 100 ng/ml. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined at 16 h. Treatment of cells with anti-TRAIL resulted in a decrease in the percentage of apoptotic cells. At 100 ng/ml, a threefold difference was seen between IgG and antibody-treated cells (*, Fisher's protected least significant difference, p < 0.02). Both soluble TRAIL receptors and an anti-TRAIL mAb inhibited endothelial cell apoptosis. The experiments were repeated three times, and error bars indicate standard deviations.

Next, the effect of a neutralizing anti-TRAIL antibody on HMEC apoptosis was determined. HMECs were plated on PDL for 16 h in the presence of anti-TRAIL or mouse IgG at 0, 50, and 100 ng/ml. The addition of an anti-TRAIL neutralizing antibody to HMECs plated on PDL for 16 h decreased the percentage of apoptotic cells (Figure 5C). Although no difference in apoptosis was noted at 50 ng/ml, the percentage of apoptotic cells decreased from 7.3 to 1.9% at 100 ng/ml. Therefore, TRAIL is at least partly responsible for the apoptosis of HMECs plated on PDL.

Serum Deprivation Combined with Loss of αvβ3 Signaling Sensitizes HMECs to Death Induced by Exogenous TRAIL

The addition of recombinant TRAIL induces apoptosis in a number of cell lines but was thought to have no effect on normal cells (reviewed in Degli-Esposti, 1999). However, recent studies have questioned this assumption because TRAIL induced apoptosis in normal human hepatocytes (Jo et al., 2000), keratinocytes (Leverkus et al., 2000), and in human brain slices (damage was noted in neurons, oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, and microglial cells) (Nitsch et al., 2000). In addition, several studies have found that TRAIL can induce apoptosis in endothelial cells; in one study HMECs and human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) were resistant to TRAIL-induced apoptosis unless the glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-linked decoy receptor TRAIL-R3 was removed through pretreatment with phospholipase C (Sheridan et al., 1997). A second study was unable to find TRAIL expression in HUVECs but found a small increase (10–20%) in cell lysis in HUVECs that had been exposed to TRAIL overnight (Gochuico et al., 2000). An additional study indicated that both HUVECs and HMECs are susceptible to TRAIL-induced apoptosis and that cell death was increased by cotreatment with cycloheximide (Li et al., 2003). Thus, under some conditions, endothelial cells may become sensitized to death induced by TRAIL.

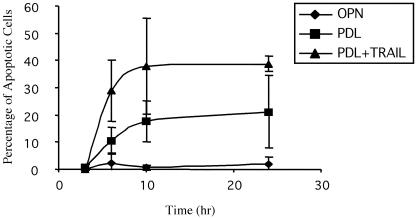

To determine whether TRAIL could increase the rate of apoptosis; HMECs were plated on PDL and 200 ng/ml recombinant human TRAIL was added 30 min later. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined at 3, 6, 10, and 24 h. Treatment of cells plated on PDL with TRAIL resulted in a two- to threefold increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells (Figure 6). HMECs also were plated on OPN and on PDL in the absence of TRAIL. TRAIL has no effect on the apoptotic rate of HMECs plated on OPN either in the presence or absence of PI-PLC (which removes the GPI-linked TRAIL-R3) (our unpublished data). Thus, serum deprivation combined with loss of αvβ3 signaling sensitizes HMECs to death induced by exogenous TRAIL.

Figure 6.

TRAIL enhances apoptosis of HMECs plated on PDL. HMECs were plated on PDL and recombinant TRAIL was added 30 min later at a concentration of 200 ng/ml. The percentage of apoptotic cells was determined at 3, 6, 10, and 24 h. Treatment of cells plated on PDL with TRAIL resulted in a two- to threefold increase in the percentage of apoptotic cells. HMECs also were plated on OPN and on PDL in the absence of TRAIL. TRAIL has no effect on the apoptotic rate of HMEC plated on OPN (our unpublished data). The results shown are representative of three independent experiments; error bars indicate standard deviations for triplicate determinations (analysis of variance, p < 0.0001).

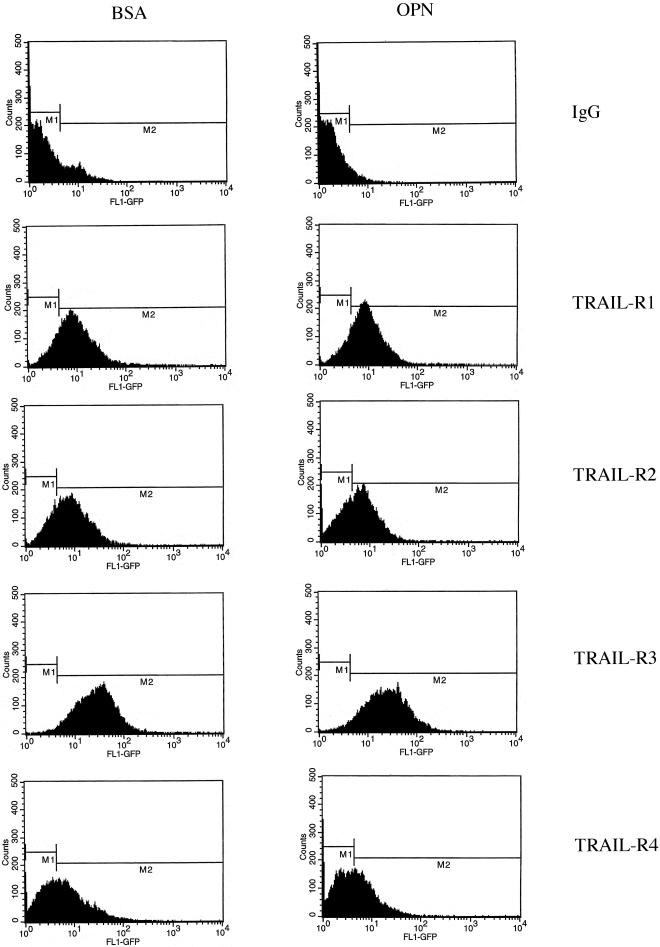

TRAIL-R Expression on the Cell Surface Is Unchanged in HMECs under Conditions of Survival

Expression of TRAIL-R has been suggested to regulate the susceptibility of cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (Sheridan et al., 1997). However, a number of studies have challenged such a correlation (Zhang et al., 1999). To determine whether modulation of TRAIL-R levels could explain the enhanced susceptibility of HMECs on PDL, HMECs were plated under conditions of apoptosis (cells kept in suspension by plating on BSA) and survival (OPN) for 4 h, trypsinized, and incubated with anti-TRAIL-R antibodies. The cells were then incubated with an FITC-labeled secondary antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry (Figure 7). The peak fluorescence intensity was calculated for each TRAIL-R and the values are shown in Table 1. FACS analysis of cell surface TRAIL-R demonstrated that the amount of TRAIL-R expression on the surface of surviving (plated on OPN) versus apoptotic (plated on BSA) cells was unchanged. Western blot analysis of HMEC lysates plated on PDL or OPN for 3, 6, 12, and 24 h confirmed that there were no changes in TRAIL-R expression (our unpublished data). Thus, modulation of TRAIL-R on the surface of HMECs does not explain the enhance susceptibility of these cells to exogenous TRAIL-induced death under conditions of serum and adhesion deprivation. Furthermore, these results confirm that up-regulation of OPG is the only change that occurs in the expression of the TRAIL-R as a result of adhesion to OPN.

Figure 7.

TRAIL-receptor expression on the cell surface is unchanged in HMECs plated on BSA and OPN. The expression of TRAIL-R on the cell surface was examined under conditions of survival (OPN) and apoptosis (cells kept in suspension by plating on BSA). HMECs were plated on OPN or BSA for 4 h and resuspended in a buffer containing 10 μg/ml goat IgG or 10 μg/ml antibody against one of TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2, TRAIL-R3, or TRAIL-R4. The cells were then incubated with a FITC-labeled anti-goat antibody and analyzed by flow cytometry. No changes were found in the expression of TRAIL-R between HMECs plated on BSA and those plated on OPN. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Table 1.

Peak fluorescence intensity of TRAIL-receptors in HMEGs plated on BSA and OPN

| Mean | Linear fluorescence intensitya | Peak fluorescence intensityb | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA IgG | 3.5 | 1.2 | |

| BSA anti-TRAIL-R1 | 24.0 | 2.7 | 2.2 |

| BSA anti-TRAIL-R2 | 16.2 | 1.9 | 1.6 |

| BSA anti-TRAIL-R3 | 51.4 | 8.0 | 6.7 |

| BSA anti-TRAIL-R4 | 14.3 | 1.8 | 1.5 |

| OPN IgG | 2.1 | 1.1 | |

| OPN anti-TRAIL-R1 | 18.7 | 2.1 | 1.9 |

| OPN anti-TRAIL-R2 | 12.3 | 1.6 | 1.4 |

| OPN anti-TRAIL-R3 | 37.0 | 4.5 | 4.1 |

| OPN anti-TRAIL-R4 | 9.1 | 1.4 | 1.3 |

The expression of TRAIL-R on the cell surface was examined under conditions of survival (OPN) and apoptosis (cells kept in suspension by plating on BSA). FACS analysis of HMEC-plated on OPN or BSA and subsequently resuspended in a buffer containing 10 μg/ml goat IgG or 10 μg/ml of antibody against one of TRAIL-R1, TRAIL-R2, TRAIL-R3, or TRAIL-R4 is shown in Figure 7. Linear fluorescence intensity (LFI) and peak fluorescence intensity values were then calculated. No changes were found in the expression of TRAIL-R between HMECs plated on OPN and those plated on BSA. Results are representative of three independent experiments.

Linear fluorescence intensity = 2(mean/17)

Linear fluorescence intensity TRAILR(1-4)/linear fluorescence intensity IgG

DISCUSSION

In the present study, recombinant OPG promoted the survival of HMECs under conditions of serum deprivation, and HMECs plated on the extracellular matrix protein OPN had increased OPG RNA and protein secretion into the media. These results confirm our previous observations that OPG is up-regulated in response to adhesion on OPN and promotes survival in RAECs (Malyankar et al., 2000) and extends these findings to primary HMECs. OPG has been found to neutralize the cell death mediator TRAIL (Emery et al., 1998), making it a logical candidate in our system. Indeed, immunoprecipitation of OPG with an anti-TRAIL mAb demonstrated that OPG and TRAIL form a complex in the lysate of HMECs plated on OPN. To further test the hypothesis that TRAIL was mediating HMEC cell death, we specifically neutralized TRAIL with soluble TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc molecules and with a specific TRAIL neutralizing antibody. We found that these molecules were able to prevent apoptosis. Finally, we were able to show that TRAIL enhanced apoptosis of HMECs plated on PDL. These findings indicate that OPG protects HMECs against serum starvation-induced cell death, in part, by binding TRAIL and blocking TRAIL-R–induced apoptosis.

TRAIL is a type II transmembrane protein with a molecular mass of 33 kDa and is a member of the tumor necrosis family of ligands (Wiley et al., 1995). TRAIL shares the highest homology with FasL with 28% amino acid identity at the C-terminal sequence. There are five TRAIL receptors, including OPG. Two receptors, TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 (Pan et al., 1997; Schneider et al., 1997; Walczak et al., 1997), contain sequences homologous to the death domains of Fas and tumor necrosis factor receptor-1 in their cytoplasmic regions and are able to induce apoptosis via caspase activation pathways. TRAIL-R3, which lacks a cytoplasmic domain and is linked to the cell membrane through a glycophospholipid anchor (Pan et al., 1997; Schneider et al., 1997; Sheridan et al., 1997), and TRAIL-R4, which contains a truncated death domain (Degli-Esposti et al., 1997; Pan et al., 1998), are considered decoy receptors for TRAIL along with OPG. Both OPG and TRAIL have been implicated in vascular pathology; OPG expression was increased in vascular smooth muscle after balloon injury (Zhang et al., 2002), and the gene for TRAIL was associated with endothelial apoptosis in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (Kim et al., 2001).

TRAIL has emerged as a cytotoxic factor for a variety of transformed cells, but it was originally not found to induce death in normal cells (Wiley et al., 1995; Pan et al., 1997). However, recent studies have shown that normal hepatocytes and keratinocytes are susceptible to specific versions of recombinant TRAIL (Jo et al., 2000; Leverkus et al., 2000; Lawrence et al., 2001; Qin et al., 2001). The level of expression of each TRAIL receptor has been proposed as the mechanism by which cells may be protected from TRAIL-medicated cytotoxicity, but this may be cell type dependent. For example, in various melanoma cell lines little correlation was found between expression of death-inducing receptors (TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2) or decoy receptors (TRAIL-R3 and TRAIL-R4) and relative susceptibilities to TRAIL (Zhang et al., 1999). However, another study in endothelial cells, considered to be resistant to TRAIL-mediated cytotoxicity, found that expression of TRAIL-R3 decoy receptor seems to be important in protection against TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Indeed, removal of the GPI-linked TRAIL-R3 receptor sensitized HUVECs to TRAIL (Sheridan et al., 1997; Zhang et al., 2000). Moreover, HUVECs that were treated with 2-methoxyestradiol demonstrated an up-regulation of both TRAIL-R2 and TRAIL, which resulted in increased susceptibility to TRAIL-induced apoptosis (LaVallee et al., 2003). In contrast, one recent paper has suggested that treatment of HUVECs with TRAIL promotes survival after serum reduction through Akt phosphorylation (Secchiero et al., 2003). These authors also found that inhibitors to the PI3K/Akt pathway such as LY294002 were able to sensitize HUVECs to TRAIL-induced apoptosis.

In our study recombinant TRAIL was able to increase the number of apoptotic cells in HMEC plated on PDL but not OPN, suggesting that lack of integrin ligation sensitizes HMECs to endogenous TRAIL. Consistent with this idea, exogenously added TRAIL had no effect on HMEC plated on OPN even after PI-PLC treatment to remove TRAIL-R3 (our unpublished data). Furthermore, no difference was noted in the expression of TRAIL-receptors (R1, R2, R3, and R4) between dying HMECs plated on PDL (or BSA) and surviving HMECs plated on OPN as examined by FACS analysis and Western blot. Only OPG, the third decoy receptor was up-regulated in HMECs on OPN, suggesting that the OPN-induced increase in OPG in endothelial cells may shift the balance toward inhibition of apoptosis by blocking TRAIL function.

Several mechanisms can be proposed to explain these results. First, it might be that the OPG alone, secreted by HMEC in response to OPN, is able to neutralize the exogenously added TRAIL. Second, there may be other pathways induced by integrin ligation that modulate TRAIL-induced apoptosis. Akt has been previously shown to mediate matrix-induced survival of normal epithelial cells (Khwaja et al., 1997) and is activated in response to αvβ3 ligation in endothelial cells (Scatena, unpublished observation). Several antiapoptotic pathways have been correlated with resistance to TRAIL. Bcl-xL an inhibitor of mitochondrial changes associated with cell death and the short splice form of c-FLIP, an inhibitor of caspase-8 activation were found to be up-regulated in TRAIL-resistant cells (Burns and El-Deiry, 2001). Smac/DIABLO (Deng et al., 2002) and caspase-3–cleaved IκBα (Kim et al., 2002a) also have been associated with TRAIL sensitivity.

The inhibition of HMECs apoptosis by the soluble TRAIL receptors (TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc) as well as OPG implies that an extrinsic, TRAIL-mediated cell death pathway is responsible for growth factor withdrawal-induced apoptosis in HMECs. Interestingly, a role for death ligands/receptors in triggering loss of anchorage-induced cell death (anoikis) in endothelial and epithelial cells also is supported by findings implicating the activation of the Fas/caspase-8 death pathway (Frisch, 1999; Rytomaa et al., 1999; Aoudjit and Vuori, 2001). The ability of OPG to fully inhibit endothelial cell apoptosis unlike the soluble TRAIL-R (TR1-Fc and TR2-Fc) suggests that these molecules may have different affinities for TRAIL. However, studies using isothermal titration calorimetry have found that at 37°C OPG actually has a lower affinity for TRAIL compared with TRAIL-R1 and TRAIL-R2 (Truneh et al., 2000). An alternate explanation may be that OPG interacts with a second apoptosis-inducing molecule. At this time, the only other known ligand for OPG is RANKL, which is known to mediate osteoclast survival (Lacey et al., 2000). RANKL was found to be angiogenic in a subcutaneous Matrigel assay in mice (Kim et al., 2002b) and inhibited HUVEC apoptosis induced by serum deprivation (Kim et al., 2003), but in our hands it had no effect on HMEC apoptosis (our unpublished data).

In conclusion, we have found that OPG acts as a survival factor for HMECs plated on OPN in the absence of serum due to its ability of bind and block TRAIL-induced apoptosis. The mechanism by which TRAIL induces apoptosis is not fully understood, but it is thought to be mediated by one or more downstream molecules that result in caspase-8 and caspase-3 activation. These downstream molecules and events are also likely to be regulated because the susceptibility of HMECs to TRAIL does not seem to be solely determined by TRAIL-R expression. The interaction of TRAIL and OPG in endothelial cells under conditions of serum deprivation may represent a mechanism of survival that occurs under ischemic conditions. Further elucidation of the function of these two molecules and the downstream effects of their interaction will result in a more complete understanding of endothelial cell survival and angiogenesis under pathological conditions.

Article published online ahead of print. Mol. Biol. Cell 10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0059. Article and publication date are available at www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0059.

References

- Alon, T., Hemo, I., Itin, A., Pe'er, J., Stone, J., and Keshet, E. (1995). Vascular endothelial growth factor acts as a survival factor for newly formed retinal vessels and has implications for retinopathy of prematurity. Nat. Med. 1, 1024-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoudjit, F., and Vuori, K. (2001). Matrix attachment regulates Fas-induced apoptosis in endothelial cells: a role for c-Flip and implications for anoikis. J. Cell Biol. 152, 633-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, P.C., Clark, R.A., and Cheresh, D.A. (1994a). Requirement of vascular integrin avb3 for angiogenesis. Science 264, 569-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks, P.C., Montgomery, A.M.P., Rosenfeld, M., Reisfeld, R.A., Hu, T., Klier, G., and Cheresh, D.A. (1994b). Integrin avb3 antagonists promote tumor regression by inducing apoptosis of angiogenic blood vessels. Cell 79, 1157-1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bucay, N., et al. (1998). Osteoprotegerin-deficient mice develop early onset osteoporosis and arterial calcification. Genes Dev. 12, 1260-1268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns, T.F., and El-Deiry, W.S. (2001). Identification of inhibitors of TRAIL-induced death (ITIDs) in the TRAIL-sensitive colon carcinoma cell line SW480 using a genetic approach. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 37879-37886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degli-Esposti, M.A. (1999). To die or not to die - the quest of the TRAIL receptors. J. Leukoc. Biol. 65, 535-542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degli-Esposti, M.A., Dougall, W.C., Smolak, P.J., Waugh, J.Y., Smith, C.A., and Goodwin, R.G. (1997). The novel receptor TRAIL-R4 induces NF-kB and protects against TRAIL-mediated apoptosis, yet retains an incomplete death domain. Immunity 7, 813-820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng, Y., Lin, Y., and Wu, X. (2002). TRAIL-induced apoptosis requires Bax-dependent mitochondrial release of Smac/DIABLO. Genes Dev. 16, 33-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler, S., Haendeler, J., Rippmann, V., Nehls, M., and Zeiher, A.M. (1996). Shear stress inhibits apoptosis of human endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 399, 71-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler, S., and Zeiher, A.M. (2000). Endothelial cell apoptosis in angiogenesis and vessel regression. Circ. Res. 87, 434-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery, J. G., et al. (1998). Osteoprotegerin is a receptor for the cytotoxic ligand TRAIL. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14363-14367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedlander, M., Theesfeld, C.L., Sugita, M., Fruttiger, M., Thomas, M.A., Chang, S., and Cheresh, D.A. (1996). Involvement of integerins avb3 and avb5 in ocular neovascular diseases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 9764-9769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch, S.M. (1999). Evidence for a function of death-receptor-related, death-domain-containing proteins in anoikis. Curr. Biol. 9, 1047-1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giachelli, C.M., Majesky, M., and Schwartz, S.M. (1991). Developmentally regulated cytochrome P-450IA1 expression in cultured rat vascular smooth muscle cells. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 3981-3986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gochuico, B.R., Zhang, J., Ma, B.Y., Marshak-Rothstein, A., and Fine, A. (2000). TRAIL expression in vascular smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. 278, L1045-L1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.J., Huang, W.Q., Mallah, J., Yang, D., Lippman, M.E., and Li, L.Y. (1999). Angiopoietin-1, and its receptor Tie-2 participate in the regulation of capillary-like tubule formation and survival of endothelial cells. Microvasc. Res. 58, 224-237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo, M., Kim, T.-H., Seol, D.-W., Esplen, J.E., Dorko, K., Billiar, T.R., and Strom, S.C. (2000). Apoptosis induced in normal human hepatocytes by tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Nat. Med. 6, 564-567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsan, A., Yee, E., Poirier, G.G., Zhou, P., Craig, R., and Harlan, J.M. (1997). Fibroblast growth factor-2 inhibits endothelial cell apoptosis by Bcl-2-dependent and independent mechanisms. Am. J. Pathol. 151, 1775-1784. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khwaja, A., Rodriguez-Viciana, P., Wennstrom, S., Warne, P.H., and Downward, J. (1997). Matrix adhesion and Ras transformation both activate a phosphoinositide 3-OH kinase and protein kinase B/Akt cellular survival pathway. EMBO J. 16, 2783-2793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, H.-H., Shin, H.S., Kwak, H.J., Ahn, K.Y., Kim, J.-H., Lee, H.J., Lee, M.-S., Lee, Z.H., and Koh, G.Y. (2003). RANKL regulates endothelial cell survival through the phostphatidylinositol 3′-kinase/Akt signal transduction pathway, FASEB J. 17, 2163-2165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., Wu, H., Hawthorne, L., Rafii, S., and Laurence, J. (2001). Endothelial cell apoptotic genes associated with the pathogenesis of thrombotic microangiopathies: an application of oligonucleotide genechip technology. Microvasc. Res. 62, 83-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, K.-W., Kim, B.-J., Chung, C.-W., Jo, D.-G., Kim, I.-K., Song, Y.-H., Kwon, Y.-K., Woo, H.-N., and Jung, Y.-K. (2002a). Caspase cleavage product lacking amino-terminus of IkBa sensitizes resistant cells to TNF-α and TRAIL-induced apoptosis. J Cell Biochem. 85, 334-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y.-M., Kim, Y.-M., Lee, Y.M., Kim, H.-S., Kim, J.D., Choi, Y., Kim, K.-W., Lee, S.-Y., and Kwon, Y.-G. (2002b). T.N.F-related activation-induced cytokine (TRANCE) induces angiogenesis through the activation of Src and PLC in human endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 6799-6805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak, H.J., So, J.N., Lee, S.J., Kim, I., and Koh, G.Y. (1999). Angiopoietin-1 is an apoptosis survival factor for endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 448, 249-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, D.L., et al. (2000). Osteoprotegerin ligand modulates murine osteoclat survival in vitro and in vivo. Am. J. Pathol. 157, 435-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacey, D.L., et al. (1998). Osteoprotegerin ligand is a cytokine that regulates osteoclast differentiation and activation. Cell 93, 165-176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVallee, T.M., Zhan, X.H., Johson, M.S., Herbstritt, C.J., Swartz, G., Willliams, M.S., Hembrough, W.A., Green, S.J., and Pribluda, V.S. (2003). 2-methoxyestradiol up-regulates death receptor 5 and induces apoptosis through activation of the extrinsic pathway. Cancer Res. 63, 468-475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence, D., et al. (2001). Differential hepatocyte toxicity of recombinant Apo2L/TRAIL versions. Nat. Med. 7, 383-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leverkus, M., Neumann, M., Menglihg, T., Rauch, C.T., Brocker, E.-B., Krammer, P.H., and Walczak, H. (2000). Regulation of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand sensitivity in primary and transformed human keratinocytes. Cancer Res. 60, 553-559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.H., Kirkiles-Smith, N.C., McNiff, J.M., and Pober, J.S. (2003). TRAIL induces apoptosis and inflammatory gene expression in human endothelial cells. J. Immunol. 171, 1526-1533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malyankar, U.M., Scatena, M., Suchland, K.L., Yun, T.J., Clark, E.A., and Giachelli, C.M. (2000). Osteoprotegerin is an avb3-induced, NF-kB-dependent survival factor for endothelial cells. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 20959-20962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin, S.M., Ganapathy, R., Kim, T.-K., Leach-Scampavia, D., Giachelli, C.M., and Ratner, B.D. (2003). Characterization and analysis of osteopontin-immobilized poly(2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate) surfaces. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. 67A, 334-343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meredith, J.E., Fazeli, B., and Schwartz, M.A. (1993). The extracellular matrix as a cell survival factor. Mol. Biol. Cell 4, 953-961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, A., et al. (1998). Severe osteoporosis in mice lacking osteoclastogenesis inhibitory factor/osteoprotegerin. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 247, 610-615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nitsch, R., Bechmann, I., Deisz, R.A., Haas, D., Lehmann, T.N., Wendling, U., and Zipp, F. (2000). Human brain-cell death induced by tumour-necrosis-factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand. Lancet 356, 827-828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, G., Ni, J., Wei, Y.-F., Yu, G.-L., Gentz, R., and Dixit, V.M. (1997). An antagonist decoy receptor and a death domain-containing receptor for TRAIL. Science 277, 815-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan, G., Ni, J., Yu, G.-L., Wei, Y.-F., and Dixit, V.M. (1998). TRUNDD, a new member of the TRAIL receptor family that antagonizes TRAIL signaling. FEBS Lett. 424, 41-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin, J.-Z., Chaturvedi, V., Bonish, B., and Nickoloff, B.J. (2001). Avoiding premature apoptosis of normal epidermal cells. Nat. Med. 7, 385-386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rytomaa, M., Martins, L.M., and Downward, J. (1999). Involvement of FADD and caspase-8 signalling in detachment-induced apoptosis. Curr. Biol. 9, 1043-1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scatena, M., Almeida, M., Chaisson, M.L., Fausto, N., Nicosia, R.F., and Giachelli, C.M. (1998). NF-κB mediates avb3 integrin-induced endothelial cell survival. J. Cell Biol. 141, 1083-1093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, P., Bodmer, J.-L., Thome, M., Hofmann, K., Holler, N., and Tschopp, J. (1997). Characterization of two receptors for TRAIL. FEBS Lett. 416, 329-334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secchiero, P., Gonelli, A., Carnevale, E., Milani, D., Pandolfi, A., Zella, D., and Zauli, G. (2003). TRAIL promotes the survival and proliferation of primary human vascular endothelial cells by activating the Akt and ERK pathways. Circulation 107, 2250-2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan, J.P., et al. (1997). Control of TRAIL-induced apoptosis by a family of signaling and decoy receptors. Science 277, 818-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonet, W.S., et al. (1997). Osteoprotegerin: A novel secreted protein involved in the regulation of bone density. Cell 89, 309-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truneh, A., et al. (2000). Temperature-sensitive differential affinity of TRAIL for its receptors. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 23319-23325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walczak, H., et al. (1997). TRAIL-R 2, a novel apoptosis-mediating receptor for TRAIL. EMBO J. 16, 5386-5397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley, S.R., et al. (1995). Identification and characterization of a new member of the TNF family that induces apoptosis. Immunity 3, 673-682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yasuda, H., et al. (1998). Osteoclast differentiation factor is a ligand for osteoprotegerin/osteoclastogenesis-inhibitory factor and is identical to TRANCE/RANKL. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 3597-3602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun, T.J., et al. (2001). Osteoprotegerin, a crucial regulator of bone metabolism also regulates B cell development and function. J. Immunol. 166, 1482-1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Fu, M., Myles, D., Zhu, X., Du, J., Cao, X., and Chen, Y.E. (2002). PDGF induces osteoprotegerin expression in vascular smooth muscle cells by multiple signal pathways. FEBS Lett. 521, 180-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.D., Franco, A., Myers, K., Gray, C., Nguyen, T., and Hersey, P. (1999). Relation of TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) receptor and FLICE-inhibitory protein expression to TRAIL-induced apoptosis of melanoma. Cancer Res. 59, 2747-2753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.D., Nguyen, T., Thomas, W.D., Sanders, J.E., and Hersey, P. (2000). Mechanisms of resistance of normal cells to TRAIL induced apoptosis vary between different cell types. FEBS Lett. 482, 193-199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]