Abstract

The RNA-binding protein CHLAMY 1 from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii binds specifically to UG(≥7) repeat sequences situated in the 3′ untranslated regions of several mRNAs. Its binding activity is controlled by the circadian clock. The biochemical purification and characterization of CHLAMY 1 revealed a novel type of RNA-binding protein. It includes two different subunits (named C1 and C3), whose interaction appears necessary for RNA binding. One of them (C3) belongs to the proteins of the CELF (CUG-BP-ETR-3-like factors) family and thus bears three RNA recognition motif domains. The other is composed of three lysine homology domains and a protein-protein interaction domain (WW). The subunits C1 and C3 have theoretical molecular masses of 45 and 52 kDa, respectively, and are present in nearly equal amounts during the circadian cycle. At the beginning of the subjective night, both can be found in protein complexes of 100 to 160 kDa. However, during subjective day when binding activity of CHLAMY 1 is low, the C1 subunit in addition is present in a high-molecular-mass protein complex of more than 680 kDa. These data indicate posttranslational control of the circadian binding activity of CHLAMY 1. Notably, the C3 subunit shows significant homology to the rat CUG-binding protein 2. Anti-C3 antibodies can recognize the rat homologue, which can also be found in a protein complex in this vertebrate.

RNA-binding proteins are involved in the regulation of a variety of biological processes (5, 10, 15). They often contain conserved domains of RNA binding in one or multiple copies. The RNA recognition motif (RRM) and lysine homology (KH) domains are conserved from bacteria to humans. A recent study showed that there are 196 RRM and 26 KH domain proteins in the fully sequenced model plant Arabidopsis thaliana (19).

In past years, it became evident that RNA-binding proteins are also involved in circadian-controlled processes (reviewed in reference 24). Circadian rhythms are biological rhythms whose period is about 24 h under constant conditions of light and temperature. Regulation via positive and negative feedback loops represents a key control mode of the circadian oscillator itself (7, 12, 32), as demonstrated in all model systems investigated so far. In all cases, the presence of transcription factors and their temporal involvement in multiprotein complexes with other clock-relevant proteins represents a major regulatory mechanism. Such a time-dependent protein-protein interaction has not been demonstrated up to now with circadian RNA-binding proteins, whose function has been extensively studied in only a few systems. Among the few identified clock-controlled RNA-binding proteins is the glycine-rich RNA-binding protein in Arabidopsis spp., AtGRP7, which is part of a slave oscillator and is involved in splicing processes (13, 35). Another example is the lark protein in Drosophila spp. that functions as a regulatory element of the clock output controlling adult eclosion (21). Another one, FMR1, whose defect causes inherited mental retardation in humans, is conserved in Drosophila spp., and its mutation affects circadian behavior (reviewed in reference 9). Recently, it was found that this protein has a protein dimerization domain (2).

In the marine bioluminescent dinoflagellate Gonyaulax polyedra, it was shown that translational regulation of the luciferin-binding protein (28), which is a component of the bioluminescent system, involves an RNA-binding protein named CCTR (25). CCTR recognizes a UG repeat sequence in the lbp 3′ untranslated region (UTR), and its binding activity is negatively correlated with translation of lbp mRNA, suggesting that it acts as a translational repressor. Notably, a CCTR homologue protein (named CHLAMY 1) is conserved in the green model alga Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Binding activity of CHLAMY 1 also changes in a circadian manner; it increases at the end of the day phase and decreases again at the end of the night phase (23). The CCTR and CHLAMY 1 proteins can efficiently recognize UG repeat sequences of a minimum length of seven repeats (27). CHLAMY 1 was shown to bind to several mRNAs of C. reinhardtii bearing a UG repeat of 7 to 16 repeat units in their 3′ UTRs (40). The highest binding activity of CHLAMY 1 was observed with mRNAs which encode proteins of nitrogen and carbon metabolism (24, 40).

UG- and CUG-binding proteins (CUG-BPs) have also been identified in animals of the mammalian system, showing that they are evolutionarily highly conserved. Thus, TDP-43 can bind a minimum of six UG single-stranded dinucleotide stretches and is involved in splicing control. It contains two RRM domains (4). The CUG-BP is a highly conserved protein which recognizes CUG repeats (16, 38). It is proposed to play a role in the pathogenesis of myotonic dystrophy, which is caused by nuclear accumulation of the transcripts of the myotonin protein kinase gene containing expanded CUG repeats in its 3′ UTR (20). It was shown that the CUG-BP can also bind specifically to UG dinucleotide repeats (37). This RNA-binding protein belongs to the CELF (CUG-BP-ETR-3-like factors) family. Members of this family have three RRM domains in common, whereby a spacer separates the first two domains from the third domain at the C terminus (16). Another CUG-BP (CUG-BP2) shares the same domain architecture as CUG-BP1. It has been characterized in epithelial cells (29), and its RNA expression pattern in embryonic rodent brain has been determined (17).

We were very interested in the characterization of CHLAMY 1 in the green model alga C. reinhardtii. This alga, whose entire genome has been released recently by the Department of Energy, already serves as a model for studying specific biological processes such as the assembly of photosynthetic complexes (33), microtubule motors (31), or circadian rhythms (14, 26). These processes can not only be investigated at a molecular genetics level but also efficiently at the biochemical level, since this alga can be easily grown in large amounts. In past years, many molecular tools have been developed for C. reinhardtii. Currently, its transcriptome is under investigation, and functional proteome approaches are being developed (8, 11, 39).

Here, we have shown that CHLAMY 1 is a heterodimer that includes two different subunits (theoretical masses, 45 and 52 kDa). One, named C1, contains three KH and a WW (protein-protein interaction) domain. The other, named C3, bears three RRM domains. Both subunits are present in nearly equal amounts during the circadian cycle, suggesting posttranslational control of binding activity. At the time point of high binding activity of CHLAMY 1, both subunits are part of protein complexes of about 100 to 160 kDa. In contrast, when binding activity is low, the C1 subunit can also be found in a protein complex of ≥680 kDa. While the domain architecture of C1 identifies it as a new type of RNA-binding protein, C3 belongs to the CELF family, which has so far been best characterized in mammals. We intend to show that a C3 homologue is expressed in different rat brain tissues, including the suprachiasmatic nuclei (SCN) and retina, and that it can also be found in protein complexes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture.

Chlamydomonas cells (wild-type strains 137 C and SAG 73.72) were grown at 24°C under stirring in high salt acetate medium under a 12-h light-12-h dark cycle (LD 12-12) with a light intensity of 300 μE per m2 per sec (1 E = 1 mol of photons). Thereby, the light intensity was measured at the top of 5-liter flasks, which were used for large-scale growth of C. reinhardtii. For some experiments, cells were grown under LD cycles to a cell density of 7 × 105 cells per ml and then put under constant conditions of a lower light flux (LL; 40 μE/m2/sec) before harvesting. The beginning of the light period is defined as time zero (LD 0 or LL 0), and the end is LD 12.

Preparation of crude extracts of C. reinhardtii.

Cells were grown to a cell density of ca. 2 × 106 to 3 × 106 cells per ml, harvested by centrifugation, and stored frozen in liquid nitrogen. For extracts, cells were resuspended in an extraction buffer (80 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, complete proteinase inhibitor cocktail [ROCHE; 50% according to their protocol]). Lysis and removal of cell debris was carried out as described before (23).

Growth of Rattus norvegicus and preparation of crude extracts.

Animals of the inbred strain LEW/Ztm were bred and raised under controlled environmental conditions (12-12 LD cycle, lights on at 0600 h, room temperature 22 ± 1°C) with food and water supplied ad libitum. Animals were killed by decapitation at the indicated time. A dim red light source (<1 lx) was used during the dark period. Tissues were cut out and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The extraction buffer was identical to the one used for the C. reinhardtii crude extract. Cells were disrupted by ultrasound sonification with a Bioblock Scientific Vibra Cell 72405 instrument. Fifteen- to 20-s steps were chosen with 24 impulses/min till the tissues appeared homogenous. After each step, the extract was put on ice for 1 min. The extract was then centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and the supernatant was used for the further assays.

Purification of CHLAMY 1.

Proteins from a crude extract were stepwise precipitated with ammonium sulfate, and the 12 to 24% fraction was pooled for further analysis. Precipitated proteins were dissolved and dialyzed against extraction buffer (see above). Specific RNA affinity chromatography was based on the protocol of Mehta and Driscoll (22). One-milliliter streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads (Promega) were washed four times with 0.5 ml of buffer B (5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 0.5 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 1 M NaCl) by using a magnet provided by Promega. Then, 20 μg of biotinylated transcript was synthesized in the presence of biotinylated CTP (biotin-14-CTP; Gibco BRL) in addition to the unmodified nucleotides by a procedure described before (40). The molar ratio of CTP to biotin-14-CTP was set at 2:1. The biotinylated transcript was added to the beads in a total volume of 0.2 ml in buffer B and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with slight agitation. Nonbound transcript was removed by 10 washing steps with 0.5 ml of buffer B for each step. Then, the beads were equilibrated eight times in 0.5 ml of buffer E (80 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0, 2 mM dithiothreitol, 5% [vol/vol] glycerol, 0.5% [vol/vol] Igepal CA-630, 25 μg of yeast RNA/ml). Meanwhile, 1 mg of the dialyzed proteins from the 12 to 24% ammonium sulfate fraction was incubated for 20 min on ice with 1 mg of poly(G) as a nonspecific competitor. This reaction mix was then added to the equilibrated streptavidin beads and incubated for 2 h at 4°C under slight agitation. Nonbound proteins were removed by several washing steps with buffer E (one time with 0.2 ml and four times with 0.5 ml) and consequently with buffer E lacking yeast RNA (six times with 0.5 ml). Elution of the bound proteins was carried out in 0.2 ml of 3 M NaCl, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), and 5% (vol/vol) glycerol for 45 min at room temperature with slight agitation.

Tryptic digestion and Edman degradation of the Coomassie-stained subunits of CHLAMY 1.

The Tryptic digestion and Edman degradation steps were performed at the sequencing facility of the Biochemistry Department (R. Deutzmann) at the University of Regensburg according to their protocols.

Mobility shift assays.

All assays, including the competition experiments, were carried out in the presence of nonspecific competitor RNA poly(G) as described earlier (40). RNA-protein complexes were resolved in a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel containing 10% glycerol that was electrophoresed at 150 V for ca. 3 h at room temperature.

Supershift assays.

After the incubation of the proteins with poly(G) and the radiolabeled transcript (40), 0.5 μl of polyclonal antibody directed against C1/2, C3, or preimmune serum were added to the binding reaction. Additionally, 0.5 μl of RNAsin (Promega) was added to prevent the RNase activity which had been detected in the rabbit serum. After 20 min of incubation at room temperature, the samples were loaded on a native gel (see “Mobility shift assays” above).

Library screening.

The construction of the cDNA library was based on the Stratagene protocol and has been described before (40). Screening of the Lambda-Zap expression library with peptide antibodies was conducted as described in the manual from Stratagene. Plasmids carrying major parts of the c1 and c3 cDNAs (see Fig. 4A and 5A) were excised in vivo according to the Stratagene protocol and labeled as pCS30 (c1) and pCS31 (c3).

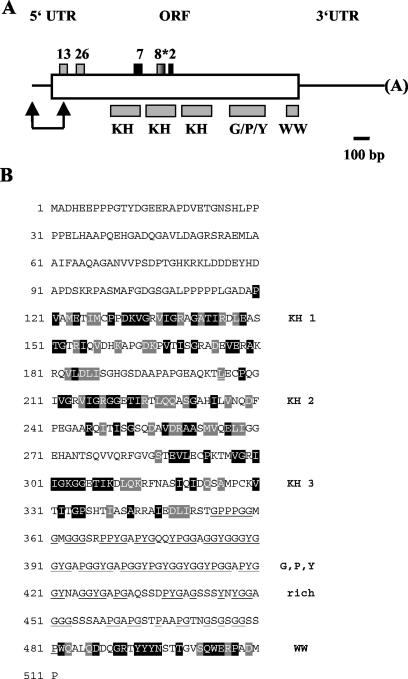

FIG. 4.

Domain architecture and amino acid composition of the protein encoded by the c1 cDNA. (A) Positions of the 5′ UTR, ORF, and the 3′ UTR are shown. It should be noted that the 5′ UTR may not be complete. The two arrows indicate a sequence part, which is not contained in our c1 cDNA clone, whose sequence can be found under GenBank accession number AY505473. Sequences of this N-terminal part have been obtained from the EST clone BI721496 (length, 579 bp), which has 381 bp overlapping with our cDNA clone. A BLAST search had been carried out for conserved domain architecture. Relevant domains are labeled. KH domains are known to be involved in RNA binding; the WW domain is a protein-protein interaction domain. G/P/Y indicates a region which is rich in Gly, Pro, and Tyr. The positions of the sequenced peptides (see Table 1) are indicated by gray (deriving from the C1 subunit) and black (deriving from the C2 subunit) boxes. Peptide 8* (from C2) overlaps in its sequence with peptide 16 (from C1). (B) The amino acid sequence of the c1 ORF is presented. The KH and WW domains have been compared to their standard domains (smart accession no. SM0322 for KH and SM0456 for WW). Identical amino acids have been highlighted in black, functionally similar amino acids in gray. The amino acids Gly, Pro, and Tyr, which frequently appear between the third KH and the WW domain, are underlined.

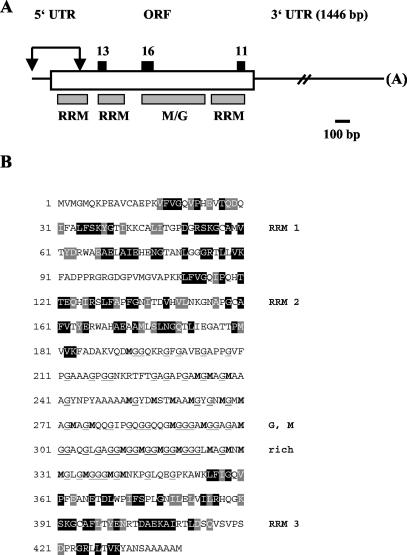

FIG. 5.

Domain architecture and amino acid composition of the protein encoded by the c3 cDNA. (A) Positions of the 5′ UTR, ORF, and the 3′ UTR are shown. It should be noted that the 5′ UTR may not be complete. The two arrows indicate a sequence part, which is not contained in our c3 cDNA clone, whose sequence can be found under GenBank accession number AY505474. Sequences of this N-terminal part have been obtained from the EST clone AV641734 (length, 506 bp), which has 168 bp overlapping with our cDNA clone. A BLAST search had been carried out for conserved domain architecture. Relevant domains are labeled. RRM domains are known to be involved in RNA binding. G and M indicate a region which is rich in Met and Gly. The positions of the sequenced peptides (see Table 1) are indicated by black boxes. (B) The amino acid sequence of the c3 ORF is presented. The RRM domains have been compared to their standard domain (smart accession no. SM0360). Identical amino acids have been highlighted in black, functionally similar amino acids in gray. The amino acids Met and Gly, which frequently appear between the second and third RRM domain, are indicated in bold (Met) or are underlined (Gly).

Preparation of plasmid constructs for overexpression of C1 and C3.

The pES1 vector, which contains a major part of the c1/2 open reading frame (ORF), was constructed by cloning a 2,101-bp fragment (from +69 bp from the start codon to the end of the cDNA sequence, including the entire 3′ UTR) from pCS30 digested with XhoI and BamHI into the multiple cloning site of the expression vector pQE31 (QIAGEN) which had been digested with SalI and BamHI. The pBZ2 vector, which contains a major part of the c3 ORF, was constructed by cloning a 1,662-bp fragment (from +198 bp from the start codon to the end of the cDNA sequence, including the entire 3′ UTR) from pCS31 digested with HincII and BamHI into the multiple cloning site of the expression vector pQE31 that had been digested with SmaI and BamHI. The pQE vector bears a six-His tag before its multiple cloning site, which can be used for purifying the overexpressed proteins. Thus, pES1 encodes the N-terminal six-His tag and 489 amino acids of the entire C1/2 512 amino acids; pBZ2 also encodes the N-terminal six-His tag and 394 amino acids of the entire C3 460 amino acids.

Protein overexpression, detection, and purification.

pES1 and pBZ2, recombinant expression plasmids encoding major parts of the CHLAMY 1 subunits (see above), were transformed into Escherichia coli strain SG13009 (QIAGEN). The E. coli cells were cultured according to the QIAGEN manual concerning pQE strains. Overexpression, detection, and purification of the proteins were also carried out by following the protocols of the supplier (QIAGEN), with some minor modifications. The time of IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) induction was set to 4 h. Complete protease inhibitor cocktail (ROCHE) was added to the denaturing lysis buffer according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

Production of antibodies.

Antisera were produced against two selected peptides (ASGAHILVNQDFPEGA for C1/2 and CQIPQHTTEQHIR for C3), which were coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin. In addition, antibodies were produced against the overexpressed and purified CHLAMY 1 subunits (C1 and C3) under denaturing conditions. All the antibody procedures were carried out at EUROGENTEC, Belgium, according to their protocol.

Coimmunoprecipitation.

Immunoprecipitations were performed by a modified procedure of Adams et al. (1). Portions (600 μg) of protein from a Chlamydomonas crude extract were incubated with 50 μl of each antiserum in 450 μl of NETN buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5% [vol/vol] Nonidet P-40) and incubated for 1 h at 4°C under slight rotation. Then, 100 μl of 3× prewashed (in NETN buffer) slurry of protein A-Sepharose (AMERSHAM BIOSCIENCES) was added and incubated for another 45 min at 4°C under slight rotation. Antigen-antibody complexes bound to protein A-Sepharose were washed with 200 μl of NETN, including 80 mM NaCl, and consequently NETN buffer. The protein A-Sepharose beads were then dried in a speed vacuum, and 140 μl of denaturing sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) buffer was added before boiling the sample for 5 min. After centrifugation for 2 min at 15,000 × g, the supernatant was used for further analysis in Western blots.

Western blot analysis.

The standard Western blot analysis follows the protocol of Sambrook et al. (34), with the following exception. As blocking substance, the commercially available soya-based Slimfast powder was used instead of milk powder. Antisera were diluted 1:100 and 1:500. Monoclonal anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G clone RG-96 peroxidase conjugate (SIGMA) was used as the secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:6,700. Signals were detected by chemoluminescence.

Sucrose density gradients.

Linear sucrose density gradients were produced from 6 to 14% sucrose in 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.7), 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) buffer, and 80 mM NaCl by using a gradient mixer and a peristaltic pump at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. After overlaying the sample onto the gradient (either with standard proteins from Bio-Rad or 3 mg of crude extract), a centrifugation step was carried out at 74,100 × g for 16 h at 4°C in a swing-out rotor. Two charges of tubes were used for the sucrose density gradients which had either a total volume of 37 or 35 ml. Protein concentration was determined with the Bradford assay according to their protocol. Peak fractions of the different standard proteins were verified by denaturing SDS-PAGE.

RESULTS

The RNA-binding protein CHLAMY 1 interacts as a heteromeric complex with a UG repeat sequence.

Circadian binding activity of CHLAMY 1 reaches its maximum at the beginning of the night between LD 10 and 14 (23). In order to purify this RNA-binding protein and use peptide sequences for cloning its cDNA, cells were harvested at the beginning of the night. For its purification, we developed a procedure including two major steps: an ammonium sulfate precipitation step, which pulls down CHLAMY 1 efficiently, and a specific RNA chromatography step (Fig. 1A). We found that CHLAMY 1 can be precipitated with very low amounts of ammonium sulfate (12 to 24%) from a crude extract. The enrichment was verified in mobility shift assays via the binding activity of CHLAMY 1 to one of its target RNAs, namely the glutamine synthetase 2 (gs2) 3′ UTR (40) (Fig. 1B). To ensure specific binding activity, all assays contained an excess of nonspecific competitor RNA [poly(G)]. In addition, a mutated gs2 transcript (gs2mut), which lacks five of the seven UG repeats from the gs2 3′ UTR (40), was used as a negative control. CHLAMY 1 requires at least seven UG repeats for efficient binding (27) and thus cannot interact with the gs2mut transcript.

FIG. 1.

Purification scheme for CHLAMY 1. (A) Procedure applied for the purification of CHLAMY 1. A CTP-biotinylated transcript (gs2wt) containing the gs2 3′ UTR, which bears seven UG repeats (40), was bound to paramagnetic streptavidin beads according to the procedure described in Materials and Methods. Dialyzed proteins from a 12 to 24% ammonium sulfate precipitation step were incubated with the RNA-bound beads in the presence of poly(G) as nonspecific competitor RNA. After several washing steps, which removed nonbound proteins, CHLAMY 1 was eluted with high salt. A parallel approach with the gs2mut transcript, which lacks five of the seven UG repeats and cannot be recognized by CHLAMY 1, served as negative control. (B and C) Autoradiograms of mobility shift assays using either the 32P-labeled gs2wt transcript or its mutagenized version, gs2mut. The radiolabeled transcripts do not contain biotinylated nucleotides. For the binding reaction, the samples were incubated in the presence of poly(G) with crude extracts (CE lanes) from Chlamydomonas cells that were harvested at the beginning of the night (LD 12). In addition, dialyzed proteins from a 12 to 24% ammonium sulfate precipitation (AS lanes) of the crude extract mentioned above were also used. RNA-protein complexes were resolved in nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gels containing 10% glycerol. (B) With both crude extracts and ammonium sulfate, the wild-type transcript (gs2wt) (lanes 3 and 5) and its mutagenized form (gs2mut) (lanes 4 and 6) were used. Lanes 1 and 2 labeled with RNA demonstrate the mobility of the transcripts (gs2wt and gs2mut) alone. (C) Autoradiogram of mobility shift assays using the 32P-labeled gs2wt transcript in the presence of proteins from the ammonium sulfate step (lane 2). In lanes 3 and 4, a 200× molar excess of unlabeled gs2wt (lane 3) or gs2mut (lane 4) transcripts, both containing biotinylated CTP, were added to the binding reaction. Lane 1 shows the mobility of the transcript alone.

Proteins from the ammonium sulfate step were then subjected to a specific RNA affinity chromatography approach. For this step, the wild-type gs2 transcript (gs2wt) was used again, as well as the gs2mut transcript as negative control. In this case, the transcripts were synthesized in the presence of a modified nucleotide, namely biotinylated CTP. In mobility shift competition assays, it was verified that CHLAMY 1 can indeed interact with a CTP-biotinylated gs2wt transcript by using such a transcript as competitor RNA (Fig. 1C). This proof was important since we had noticed before that CHLAMY 1 cannot interact with a UTP-biotinylated transcript (data not shown), most likely due to steric inhibition of binding caused by the biotin residues within the UG repeat binding site. Both transcripts (gs2wt and gs2mut) were bound via their biotin residues to streptavidin-coated paramagnetic beads. The transcript-containing beads were then incubated with dialyzed proteins from the 12 to 24% ammonium sulfate fraction in the presence of poly(G).

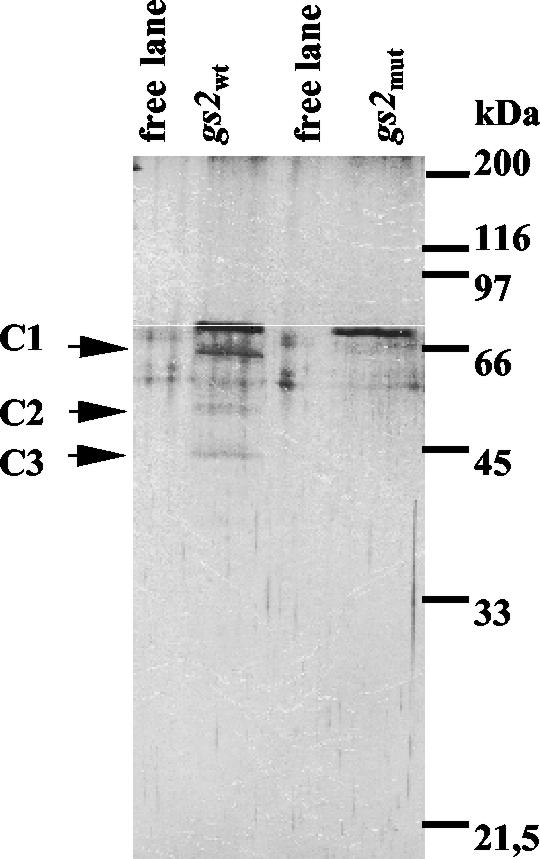

After several washing steps, which removed nonspecific proteins, proteins bound either to the biotinylated RNA or the streptavidin beads were eluted by high salt. Subsequently, they were dialyzed and visualized on a denaturing SDS-polyacrylamide gel by silver staining (Fig. 2). Proteins that could be identified with both the gs2wt and the gs2mut transcript were not further considered, because they do not specifically interact only with the UG repeat region. They could have binding affinity to biotin or streptavidin. Three proteins having molecular masses of about 60, 52, and 45 kDa were found with the gs2wt transcript only and not with the UG repeat mutated transcript. One way to interpret these data is that CHLAMY 1 includes three different subunits. However, it was also possible that, despite the addition of proteinase inhibitor, the 60-kDa protein may have been degraded. Later investigations (see below) have shown that two of the subunits (the 60-kDa one, named C1, and the 52-kDa one, named C2) are indeed encoded by one cDNA, while the third subunit (the 45-kDa one, named C3) is encoded by a separate cDNA. Therefore, CHLAMY 1 appeared to represent a heteromeric complex of two different subunits (C1 and C3).

FIG. 2.

CHLAMY 1 is composed of different subunits. CHLAMY 1 was purified in parallel with either the gs2wt or gs2mut transcript as described for Fig. 1A. Eluted proteins were dialyzed, electrophoresed on an SDS-12.5% polyacrylamide gel along with a molecular weight standard, and visualized by silver staining. Two free lanes demonstrate background bands caused by the silver staining procedure.

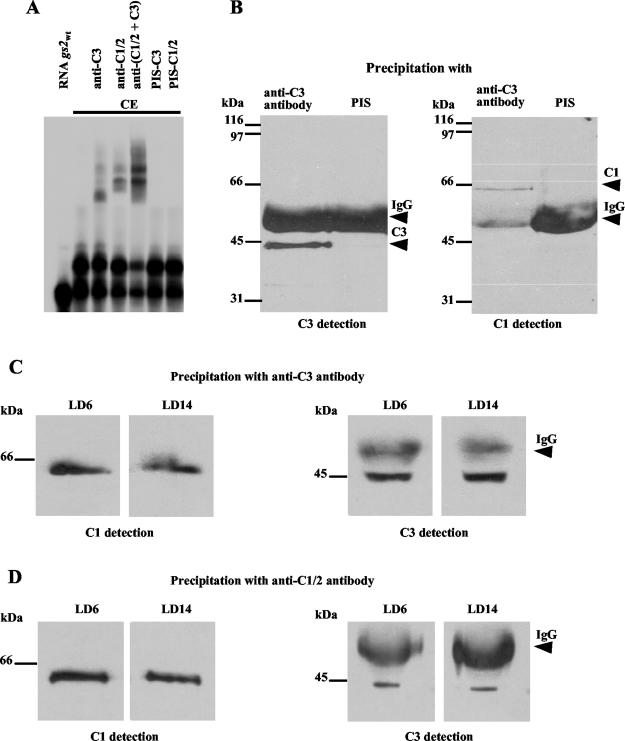

To confirm that CHLAMY 1 indeed binds as the C1-C3 complex to the UG-containing RNA, we performed supershift assays with polyclonal antibodies directed against C1/2 or C3. For this purpose, major parts of the two cDNAs were overexpressed in E. coli; subsequently, the subunits were purified and used for the production of polyclonal antibodies (see Material and Methods). The antibodies were added to the binding reaction with proteins from a C. reinhardtii crude extract (LD 14), poly(G), and the gs2wt transcript. In one case, only anti-C3 or anti-C1/2 antibody was added, and in the other case, they were put there in combination (Fig. 3A). As a negative control, preimmune sera were applied. The RNA-CHLAMY 1 complex was clearly shifted in some part with both the anti-C3 and the anti-C1/2 antibody. Shifts were even stronger when both antibodies were combined in one binding reaction. These results show that CHLAMY 1 includes the C1-C3 complex.

FIG. 3.

Protein-protein interaction of the C1 and C3 subunits and their interaction with the UG-containing gs2wt transcript. (A) Autoradiogram of supershift assays using the 32P-labeled gs2wt transcript. The first lane labeled with RNA demonstrates the mobility of the transcript (gs2wt) alone. For the binding reaction, the samples were incubated in the presence of poly(G) with a crude extract (CE lanes) from Chlamydomonas cells that were harvested at the beginning of the night (LD 14). In some cases, anti-C3 antibody (lane 3) and anti-C1/2 antibody (lane 4) were added to the binding reaction as described in Materials and Methods. In one case, anti-C1/2 and anti-C3 antibodies were added together to the binding reaction (lane 5). As a negative control, C3 (lane 6) and C1/2 (lane 7) preimmune sera (PIS) were added to the binding reaction. RNA-protein complexes were resolved in a nondenaturing 4% polyacrylamide gel containing 10% glycerol. (B) Coimmunoprecipitation assays were carried out with proteins from crude extracts of Chlamydomonas cells, which had been grown in continuous light. Precipitation was done according to the procedure described in Materials and Methods with polyclonal antibodies directed against the C3 subunit or with preimmune serum as control. Precipitated proteins were denatured, separated by SDS-9% PAGE, and subjected to a Western blot analysis with antibodies directed either against the C3 (C3 detection) or the C1 (C1 detection) subunit. Cross-reactions of immunoglobulin G (IgG) with the secondary antibody (see Materials and Methods) are indicated. (C and D) Coimmunoprecipitation assays were carried out with proteins from crude extracts of Chlamydomonas cells, which were grown under a LD cycle and harvested either at LD 6 or at LD 14. Coimmunoprecipitation was performed with the antibodies directed against either the C3 (C) or the C1 (D) subunit. Precipitated proteins were treated as described for panel B and examined in Western blot analysis for the presence of both subunits (C3 and C1 detection).

To verify the protein-protein interaction of the C1 and C3 subunits, we carried out immunoprecipitation assays. For this purpose, the anti-C1/2 and -C3 antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate either the C1/2 or C3 subunit and to determine if the other subunit would coimmunoprecipitate. The assay was established with antibodies directed against the C3 subunit. A crude extract was prepared from cells grown in constant light, and proteins were precipitated with the C3 antibodies. As expected, the C3 subunit could be detected among the precipitated proteins in a subsequent Western blot analysis (Fig. 3B). When the precipitated proteins were examined for the presence of the C1 subunit, this subunit could also be identified, confirming the interaction of the subunits.

The immunoprecipitation assays were then repeated with cells grown under a LD cycle which were harvested at either LD 6 (low binding activity of CHLAMY 1) or LD 14 (high binding activity of CHLAMY 1). When antibodies directed against the C3 subunit were used, the same results as above were observed at both time points (Fig. 3C). In parallel, when antibodies against the C1 subunit were used, not only this subunit but also the C3 subunit could be precipitated at both time points (Fig. 3C). The C2 subunit was not significantly present in either of these precipitations, suggesting that it indeed presents a degradation product of the C1 subunit that is produced during the purification procedure. Thus, the native CHLAMY 1 complex includes the C3 (45-kDa) and the C1 (60-kDa) subunits that are present at equal amounts at the two chosen times of the LD cycle.

Both cDNAs encoding CHLAMY 1 subunits contain conserved RNA binding motifs.

In order to clone the cDNAs encoding CHLAMY 1, the protein complex was stoichiometrically purified to about 100 pmol for each subunit according to the procedure mentioned above. All three potential subunits were separated by SDS-PAGE, visualized by Coomassie staining, excised from the gel, and treated with trypsin. Sequences of the resulting peptides were determined by Edman degradation. Sequences of up to 24 amino acids were determined (Table 1). One of the peptides in subunit C1 (peptide 16) was identical in its overlapping part with one from subunit C2 (peptide 8). The overlapping part of these peptides (ASGAHILVNQDFPEGA) as well as a part of peptide 13 (QIPQHTTEQHIR) from the C3 subunit were coupled to keyhole limpet hemocyanin and then used for the production of peptide antibodies. A cDNA expression library (40) was screened with these peptide antibodies. Two different cDNAs were found in this way. One of them, called c1/2, contains all peptides that could be identified in the C1 and C2 subunits (Fig. 4A). The other one contained all peptides that were found in the C3 subunit (Fig. 5A). Thus, we concluded that the C1 and C2 subunits are encoded from one cDNA and the C3 subunit is encoded from a different cDNA. In the meantime, the genes belonging to these cDNAs could be identified on scaffolds 75 (c1) and 86 (c3) with the help of the C. reinhardtii genome project (version 2) of the U.S. Department of Energy (V. Tolchkov, A. Nykytenko, and M. Mittag, unpublished data).

TABLE 1.

Peptide sequences from the different CHLAMY 1 subunitsa

| Subunit and peptide | Sequence |

|---|---|

| Subunit C1 | |

| C1-13 | XPVVETGNSHLPP |

| EMQIIE | |

| LL | |

| C1-16 | TIQQASGAHILVNQDFPEG* |

| QVEDLI | |

| C1-26 | XXAEMLATIFAAQAGAN |

| IGP | |

| Subunit C2 | |

| C2-2 | XITISGSQ |

| C2-7 | XVLDLISGHHDDAA |

| GGSS | |

| C2-8 | XLQQASGAHILVNQDFPEGA* |

| Subunit C3 | |

| C3-1 | TLLVK |

| DSQVSVPSDPR | |

| C3-13 | XLFVXQIPQHTTEQHIR |

| C3-16 | XFGAVEGAPPGVFPGAAAGPGGNKR |

X, not determinable; *, peptides which are overlapping in sequence. Underlines indicate amino acids that are not clear. Amino acids underneath the sequence indicate positions where it is not clear which amino acid is valid. Bold indicates amino acids that are found in the C1/2 or C3 ORF.

Both cDNAs comprised the major part of the ORFs and the entire 3′ UTRs. The N termini and part of the 5′ UTRs could be assembled by sequence comparison with available expressed sequence tag (EST) sequences (Fig. 4A and 5A). Thus, the c1 cDNA encodes a protein of 51,706 Da, and the c3 cDNA encodes a protein of 44,979 Da. While the C3 subunit migrates according to its molecular mass in SDS-PAGE, the C1 subunit migrates at a higher apparent mass of ca. 60 kDa. This was observed not only in C. reinhardtii extracts but also in the recombinant protein overexpressed in E. coli (data not shown).

Bioinformatic analysis of the cDNAs showed that both contain conserved domains of RNA binding motifs. The c1/2 cDNA bears three KH domains and, in addition, a domain known for protein-protein interaction, the WW domain (Fig. 4A and B). Such an RNA-binding protein containing three KH domains and a WW domain could not be found up to now in BLAST searches and seems to represent a novel type of RNA-binding protein. Also of note is the presence of a 130-amino-acid-long region between the third KH and the WW domain, which contains numerous Gly (n = 51), Pro (n = 19), and Tyr (n = 16).

The c3 cDNA contains three RRM domains separated by a spacer of 170 amino acids which is rich in Met (n = 27) and Gly (n = 56) (Fig. 5A and B). Such RNA-binding proteins, with two RRM domains at the N terminus and one at the C terminus of a protein separated by a spacer, are already known in mammals and other organisms (see below) and belong to the so called CELF family.

Circadian binding activity of CHLAMY is not correlated with the amounts of its subunits.

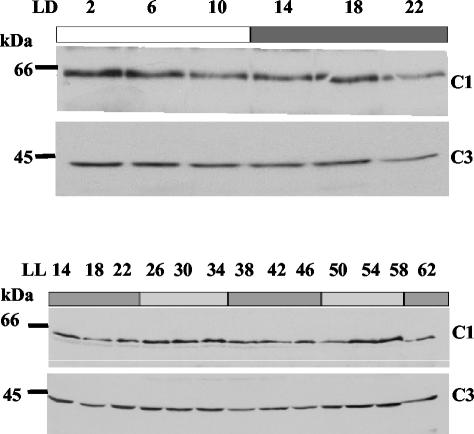

CHLAMY 1-binding activity increases at the end of the day phase and is high until the end of the night phase (23). Therefore, it seemed tempting to assume that the amount of the subunits would change in a parallel manner. To check for this, the polyclonal antibodies raised against the C1 and C3 subunit were used in Western blot analysis (Fig. 6). Cells were harvested either during an LD or a LL cycle, and protein crude extracts were prepared. Surprisingly, the amounts of both the C3 and C1/2 subunits did not correlate with the binding activity of CHLAMY 1. At the beginning of the night phase, when its binding activity is high, both subunits were present at similar or even lower amounts as in the day phase. This could be found under both LD and LL conditions. Therefore, the increase of binding activity at the beginning of the night phase is not due to changes in the amounts of the subunits. Thus, a posttranslational mechanism seems likely to contribute to the circadian binding activity of CHLAMY 1.

FIG. 6.

The amounts of the C1 and C3 subunits do not correlate with circadian binding activity of CHLAMY 1. Chlamydomonas cells were grown under a light-dark cycle (LD) or under continuous dim light (LL) and cells were harvested at the indicated time points. Proteins from a crude extract were denatured and 100 μg per lane was electrophoresed by SDS-9% PAGE. Western blot analysis was carried out by using the antibodies directed against either the C3 or the C1 subunit. To control for equal amounts of loaded proteins, another gel was run in parallel and the proteins were stained by Coomassie stain (data not shown).

Circadian-controlled multicomplex formation of CHLAMY 1 subunits.

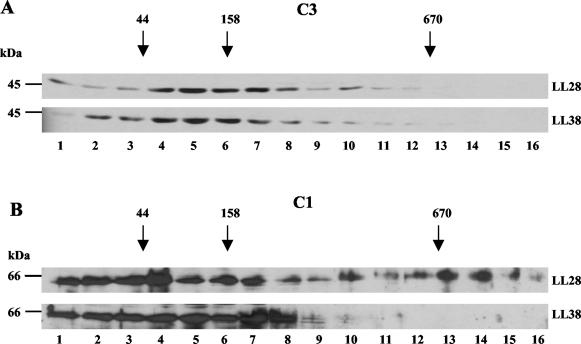

The immunoprecipitation assays had confirmed that CHLAMY 1 includes two different subunits which interact, but it could not answer the question of whether the native CHLAMY 1 complex has only one C1 and one C3 subunit. An alternative was that more than one C1 and C3 subunit could form a complex. To investigate these possibilities, we decided to determine the native molecular mass of the CHLAMY 1 subunits in sucrose density gradients. Also, it was of interest to find out which posttranslational mechanism regulates circadian binding activity. One possibility includes differential formation of the subunits. This could be accomplished either by adding more than one subunit per complex or by including novel subunits at certain circadian times. For this purpose, cells which had been synchronized by a LD cycle were grown under circadian conditions (LL) and harvested at LL 28 and LL 38. The time point LL 28 represents the middle of the subjective day when CHLAMY 1-binding activity is low (23); LL 38 represents the beginning of the subjective night. At this time point CHLAMY 1-binding activity is high. Cells from these two points of time were then used for the preparation of crude extracts.

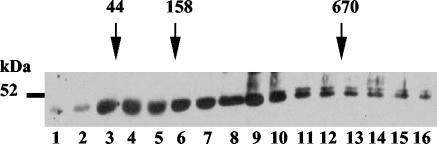

The separation of proteins within the sucrose density gradients was evaluated with standard proteins of known molecular mass (670, 158, and 44 kDa). If the C1 and C3 subunits were in a complex with one subunit each, a native molecular mass of about 100 kDa could be expected. If they are also present individually, additional peaks at around 45 and 52 kDa should be found. When proteins of the different sucrose gradient fractions were examined in a Western blot analysis for the presence of the C1 and C3 subunits (Fig. 7), it was found that some complexes were peaking around 100 kDa. This indicates that the C3 and C1 subunits are present in a complex with a 1:1 ratio at both circadian time points. But there were also complexes of around 160 kDa visible, as well as peaks accounting for the free subunits. Importantly, the C1 subunit was also found in a large protein complex of more than 680 kDa; however, this was only at LL 28 when the binding activity of CHLAMY 1 is low. This association suggests that the binding activity at different circadian times is controlled in concert with the differential multiprotein complex formation.

FIG. 7.

Formation of multiprotein complexes bearing the C1 and C3 subunits during day and night phases. Cells were grown under a LD cycle and then put under LL. They were harvested in the middle of subjective day (LL 28) and at the beginning of subjective night (LL 38). Crude extracts were prepared according to the procedure in Materials and Methods. For each gradient, equal amounts of proteins were loaded on a linear 6 to 14% sucrose density gradient. The gradients were centrifuged at 74,100 × g for 16 h at 4°C. Fraction numbering starts with the low percentage (6%). In parallel, a gradient with proteins of known molecular masses was run. Aliquots of the fractions were electrophoresed by SDS-9% PAGE and analyzed in Western blots for the presence of the C3 (A) and C1 (B) subunits.

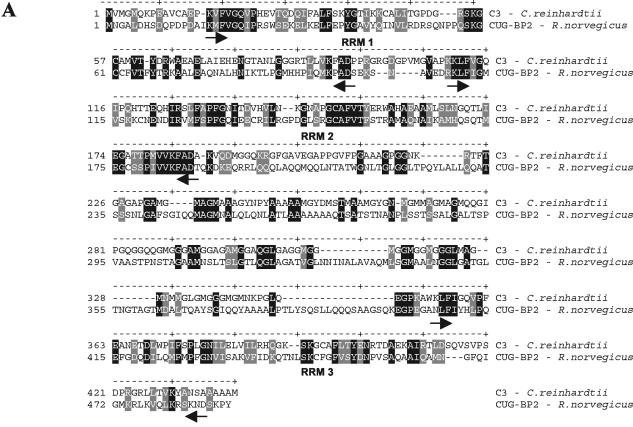

The C3 subunit is conserved in mammals and is also involved in multiprotein complexes.

CUG-BPs and members of the CELF family in mammals and other organisms have the same domain structure as the C3 subunit of C. reinhardtii (Fig. 8A). They are known to be involved in different posttranscriptional processes, including mRNA stability, translational, and splicing control (16). Changes in the repeat length of CUGs can result in severe diseases, like muscular dystrophy. Interestingly, patients suffering from this disease also have defects in the circadian system (30). Thus, we wanted to examine if the homologue of the C3 subunit would be expressed in tissues related to major functions of the circadian clock such as the SCN or retina. The presence of proteins of the CELF family had already been checked in different tissues of mice (16). However, in this approach different brain areas and the retina have not been especially investigated. We chose the rat (R. norvegicus) for our investigations; its CUG-BP2 shows relatively high homology to C3 (Fig. 8A). It encodes a protein of a theoretical mass of 52 kDa. We checked if the antibodies directed against the C3 subunit of C. reinhardtii would recognize a protein of this size. As a negative control, the Western blot analysis was also carried out with preimmune serum. Indeed, a protein of about 52 kDa specifically interacted with the anti-C3 antibody in the retina as well as in the examined brain tissues. These include the hypothalamus, SCN, cerebellum, cortex, and bulbus olfactorius (Fig. 8B).

FIG. 8.

The C3 subunit shows significant homology to the rat CUG-BP2 (52 kDa) and belongs to the CELF family. The anti-C3 antibody of C. reinhardtii can recognize a 52-kDa protein in different rat brain tissues and in the retina. (A) The amino acid sequence of C3 was aligned with rat CUG-BP2 (NP_058893) by using the DNA Star program by Clustal W. Identical amino acids are marked in black, functionally similar ones in gray. The positions of the three RRM domains are indicated. (B) Rats were sacrificed at the beginning of the day (LD 2) and different brain tissues were taken. Crude extracts of rat brain tissues were prepared as described in Materials and Methods. Proteins were electrophoresed by SDS-9% PAGE and used for Western analysis with either preimmune serum (PIS) as control or anti-C3 antibody (C3).

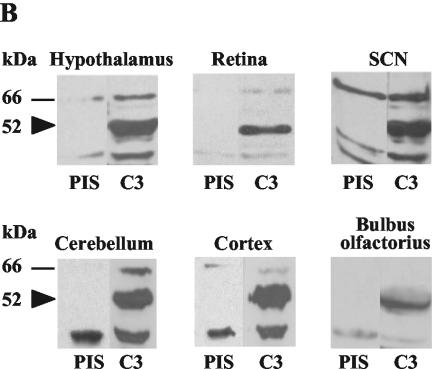

Since the C3 subunit of C. reinhardtii interacts with another protein and can be found in a protein complex, we wanted to check if the mammalian C3 homologue in the brain would also be a part of a protein complex there. For its biochemical characterization, it was useful to choose a brain tissue that was not too small in size. Thus, we selected the cortex, where the presence of the C3 subunit had been demonstrated (Fig. 9). Albeit some part of the C3 homologue is present as a monomer in this tissue, a major part is associated in multiprotein complexes ranging in apparent molecular masses between the 158- and 670-kDa standard proteins (Fig. 9).

FIG. 9.

The rat C3 homologue is also present in protein complexes. Rats were sacrificed at the beginning of the day (LD 2). A crude extract of the cortex was prepared according to the procedure from Materials and Methods. Aliquots of the fractions were loaded on a linear 6 to 14% sucrose density gradient (for details, see the legend for Fig. 7). Aliquots of the fractions were electrophoresed by SDS-9% PAGE and analyzed in Western blots with anti-C3 antibody for the presence of the 52-kDa rat C3 homologue. Due to slightly smaller tubes (see Materials and Methods), peaks of the standard proteins do not migrate to the same positions as the ones from the sucrose gradients of Fig. 7.

DISCUSSION

Biochemical purification of CHLAMY 1.

We have used a biochemical approach to isolate and characterize the circadian RNA-binding protein CHLAMY 1 from C. reinhardtii which binds specifically to UG(≥7) repeat sequences (23, 27). It was shown earlier that several mRNAs of C. reinhardtii bear such a motif in their 3′ UTR and that CHLAMY 1 can bind to the different 3′ UTRs (40). The purification of CHLAMY 1 was carried out with a two-step procedure involving a 12 to 24% ammonium sulfate step followed by a specific RNA affinity purification, which is based on the interaction of the biotinylated target transcript (gs2wt) with paramagnetic streptavidin beads. Importantly, an efficient control could be added by using a mutagenized gs2 transcript which lacks several UG repeats. In mobility shift assays, it was shown that there are no RNA-binding proteins interacting with this transcript in the presence of nonspecific competitor RNA. Thus, the 70-kDa protein (Fig. 2) that appeared with both purifications (gs2wt and gs2mut) most likely represents a protein that shows affinity to either biotin or streptavidin. Clearly, the C1 (60-kDa), the C2 (52-kDa), and the C3 (45-kDa) subunits specifically appear with the wild-type transcript. Thereby, the C2 subunit may be a degradation product of C1. It is not significantly present in the immunoprecipitation assays. The C1 and C2 subunits are encoded by the same cDNA, in which all sequenced peptides of both subunits can be found.

In supershift assays we could confirm that both the C1 and C3 subunits are bound to the UG-containing gs2wt transcript. In addition, the specific protein-protein interaction of the C1 and C3 subunits was demonstrated in immunoprecipitation assays. In both light and dark conditions, their interaction could be shown. This interaction was found in concert with the formation of the 100- to 160-kDa protein complexes, which are present during subjective day and night.

Domain architecture of the C1 subunit and its potential significance in the temporal binding activity of CHLAMY 1.

The C1 subunit bears three subsequent KH domains in the middle of the protein which are known to be involved in RNA binding (5, 10). In addition, it has a WW motif at its C terminus. By using BLAST searches, we could not find an RNA-binding protein sequence that has the same domain architecture as the C1 subunit, thus indicating that it is a novel type of RNA-binding protein. The WW motif is known as a protein-protein interaction module that binds to short Pro-rich motifs (36). One major group binds the minimal core consensus Pro-Pro-X-Tyr and the other Pro-Pro-Leu-Pro. A third group selects Pro flanked by Arg or Lys, and the group IV has a preference for phospho-Ser-Pro or phospho-Thr-Pro. In this context, it is striking that the spacer region between the third KH and the WW domain is very rich in Pro, but there are also several Pro situated at the N terminus of C1. Immediately before the WW domain, a Thr-Pro as well as a Ser-Pro sequence occur, but we have no direct indication so far that the Ser and Thr are phosphorylated. Only the slightly higher mobility of C1 in the fractions of the >680-kDa complex on SDS-PAGE indicates that this might be possible.

Thus, the C1 subunit could be involved in a protein-protein interaction with itself in addition to its interaction with the C3 subunit. Since this subunit can be found in protein complexes of ca. 100 to 160 kDa and during subjective day even in a >680-kDa complex (Fig. 7), it might be that this high-molecular-mass complex represents a homomer of this protein. But, we also cannot rule out that the >680-kDa complex contains some cellular target RNA attached to C1 or some novel interaction partner. Since C3 does not seem to be present in a significant amount in this large complex (Fig. 7), we exclude that it might contain a UG-bearing RNA, whose recognition is based on the C1-C3 complex (Fig. 2 and 3). The first hypothesis that the >680-kDa complex might represent a C1 homomer is indeed supported by very recent data. Native C1 protein that has been isolated from E. coli overexpressing C1 can also be found in a >680-kDa complex (K. Prager, E. Schmidt, D. Iliev, and M. Mittag, unpublished data). Potential temporal phosphorylation triggering of such formation would be an intriguing mechanism, since many essential clock proteins in model organisms like Neurospora spp., Drosophila spp., and mice are regulated by phosphorylation (3, 18, 32, 41).

The slight increase in the amount of C1 during subjective day, which is negatively correlated with the binding activity of CHLAMY 1, can be explained by the additional existence of the >680-kDa complex, which contains C1, at LL 28 but not at LL 38. It seems possible that this complex is involved in the decrease of CHLAMY 1-binding activity during subjective day, e.g., by interacting with the lower-molecular-mass complexes and thus preventing their binding to the UG repeat sequence.

Domain architecture of the evolutionarily conserved C3 subunit and its significance.

In contrast to C1, the C3 subunit can be grouped into the CELF family of known RNA-binding proteins. These RNA-binding proteins consist of three RRM domains separated by a spacer between the second and third RRM domains. They are very diverse in their function, which has been pointed out earlier, and have been found to interact not only with CUG but also with UG and even AU repeat sequences (16, 29, 37). The spacer region has been postulated to be involved in protein-protein interaction (16). Thus, it could represent the region of C3 that interacts with C1. Another possible interaction domain of C3 could be the small region between the first and second RRM domains, which contains a Pro-Pro-Arg motif that is a potential target for the WW domain situated on C1.

The spacer between RRM 2 and 3 in the C3 subunit is especially interesting since it contains numerous Met (n = 27), which is rather unusual for a protein. A Met-rich region has been described in the protein signal recognition particle 54 (SRP54), which is an integral part of the mammalian SRP (6). In this case, this region is involved in binding the SRP RNA and a signal peptide. Also, two poly-Ala stretches can be found in C3; one of them is situated in the spacer and the other at its C terminus. Such stretches also occur in some chloroplast RNA-binding proteins such as Nac2 (emb/CAB96529). BLAST amino acid alignments showed a significant homology of the C3 subunit to members of the CELF family, especially to the CUG-BPs. Thereby, the closest homology was found to the well conserved RRM domains. However, in the case of the rat CUG-BP2, also named Etr-r3 (17), some homology to C3 was also visible in the spacer region (Fig. 8A), which also contains several Met. In total, C3 contains 35 Met and the rat CUG-BP2 contains 20 Met.

Thus, it was interesting for us to check if the anti-C3 antibody would recognize its mammalian rat homologue of 52 kDa. We found some cross-reaction in the master seat of the mammalian clock, the SCN, as well as in other brain tissues, including the hypothalamus, cerebellum, bulbus olfactorius, and cortex, as well as the retina.

Since the UG-binding protein of the dinoflagellate G. polyedra (25) and CHLAMY 1 are known to represent protein complexes, we examined if the rat C3 homologue would also be part of a protein complex or if it was present in its unbound monomeric form. In the selected tissue, the cortex, the C3 homologue is indeed present in protein complexes. Thus, the formation of protein complexes of CUG/UG-binding proteins appears to be evolutionarily conserved.

Acknowledgments

We thank Jay C. Dunlap, Woody Hastings, and Einar J. Stauber for helpful suggestions concerning the manuscript. We also appreciate the helpful comments of some unknown referees.

Our work was supported by grants of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. We are thankful for the free delivery of information by the United States and Japanese genome projects of C. reinhardtii.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams, P. D., S. Seeholzer, and M. Ohn. 2002. Identification of associated proteins by coimmunoprecipitation. Protein-protein interaction: a molecular cloning manual, p. 59-74. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 2.Adinolfi, S., A. Ramos, S. R. Martin, P. F. Dal, P. Pucci, B. Bardoni, J. L. Mandel, and A. Pastore. 2003. The N-terminus of the fragile X mental retardation protein contains a novel domain involved in dimerization and RNA binding. Biochemistry 42:10437-10444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allada, R., P. Emery, J. S. Takahashi, and M. Rosbash. 2001. Stopping time: the genetics of fly and mouse circadian clocks. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 24:1091-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Buratti, E., and F. B. Baralle. 2001. Characterization and functional implications of the RNA binding properties of nuclear factor TDP-43, a novel splicing regulator of CFTR exon 9. J. Biol. Chem. 276:36337-36343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burd, C. G., and G. Dreyfuss. 1994. Conserved structures and diversity of functions of RNA-binding proteins. Science 265:615-621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemons,W. C., Jr., K. Gowda, S. D. Black, C. Zwieb, and V. Ramakrishan. 1999. Crystal structure of the conserved subdomain of human protein SRP54M at 2.1 Å resolution: evidence for the mechanism of signal peptide binding. J. Mol. Biol. 292:697-705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunlap, J. C. 1999. Molecular bases for circadian clocks. Cell 96:271-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fuhrmann, M. 2002. Expanding the molecular toolkit for Chlamydomonas reinhardtii—from history to new frontiers. Protist 153:357-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gao, F. B. 2002. Understanding fragile X syndrome: insights from retarded flies. Neuron 34:859-862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grishin, N. V. 2001. KH domain: one motif, two folds. Nucleic Acids Res. 29:638-643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grossman, A. R., E. E. Harris, C. Hauser, P. A. Lefebvre, D. Martinez, D. Rokhsar, J. Shrager, C. D. Silflow, D. Stern, O. Vallon, and Z. Zhang. 2003. Chlamydomonas reinhardtii at the crossroads of genomics. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1137-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harmer, S. L., P. Satchidananda, and S. A. Kay. 2001. Molecular bases of circadian rhythms. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 17:215-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heintzen, C., M. Nater, K. Apel, and D. Staiger. 1997. AtGRP7, a nuclear RNA-binding protein as a component of a circadian-regulated negative feedback loop in Arabidopsis thaliana. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:8515-8520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacobshagen, S., J. R. Whetstine, and J. M. Boling. 2001. Many but not all genes in Chlamydomonas reinhardtii are regulated by the circadian clock. Plant Biol. 3:592-597. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuersten, S., and E. B. Goodwin. 2003. The power of the 3′ UTR: translational control and development. Nat. Rev. Genet. 4:626-637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ladd, A. N., N. Charlet-B., and T. A. Cooper. 2001. The CELF family of RNA binding proteins is implicated in cell-specific and developmentally regulated alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:1285-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Levers, T. E., S. Tait, M. Birling, P. J. Brophy, and D. J. Price. 2002. Etr-r3/mNapor, encoding an ELAV-type RNA binding protein, is expressed in different cells in the developing rodent forebrain. Mech. Dev. 112:191-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu, Y., J. Loros, and J. C. Dunlap. 2000. Phosphorylation of the Neurospora clock protein FREQUENCY determines its degradation rate and strongly influences the period length of the circadian clock. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 4:234-239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorkovic, Z. J., and A. Barta. 2002. Genome analysis: RNA recognition motif (RRM) and K homology (KH) domain RNA-binding proteins from the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 30:623-635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu, X., N. A. Timchenko, and L. T. Timchenko. 1999. Cardiac elav-type RNA-binding protein (ETR-3) binds to RNA CUG repeats expanded in myotonic dystrophy. Mol. Hum. Genet. 8:53-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNeil, G. P., X. Zhang, G. Genova, and R. R. Jackson. 1998. A molecular rhythm mediating circadian clock output in Drosophila. Neuron 20:297-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta, A., and D. M. Driscoll. 1998. A sequence-specific RNA-binding protein complements apobec-1 to edit apolipoprotein B mRNA. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18:4426-4432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mittag, M. 1996. Conserved circadian elements in phylogenetically diverse algae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:14401-14404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mittag, M. 2003. The function of circadian RNA-binding proteins and their cis-acting elements in microalgae. Chronobiol. Int. 20:529-541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mittag, M., D. H. Lee, and J. W. Hastings. 1994. Circadian expression of the luciferin-binding protein correlates with the binding of a protein to the 3′ untranslated region of its mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 91:5257-5261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mittag, M., and V. Wagner. 2003. The circadian clock of the unicellular eukaryotic model organism Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. Biol. Chem. 384:689-695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mittag, M., and H. Waltenberger. 1997. In vitro mutagenesis of binding site elements of the clock-controlled proteins CCTR and Chlamy 1. Biol. Chem. 378:1167-1170. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morse, D., P. M. Milos, E. Roux, and J. W. Hastings. 1989. Circadian regulation of the synthesis of substrate binding protein in the Gonyaulax bioluminescent system involves translational control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 86:172-176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mukhopadhyay, D., C. W. Houchen, S. Kennedy, B. K. Dieckgraefe, and S. Anant. 2003. Coupled mRNA stabilization and translational silencing of cyclooxygenase-2 by a novel RNA binding protein, CUGBP2. Mol. Cell 11:113-126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okumura, K., Y. Aso, K. Tayama, N. Yoshida, Y. Takiguchi, Y. Takemura, and T. Inukai. 2002. Myotonic dystrophy associated with variable circadian rhythms of serum cortisol and isolated thyrotropin. Am. J. Med. Sci. 324:158-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pazour, G. J., and G. B. Witman. 2000. Forward and reverse genetic analysis of microtubule motors in Chlamydomonas. Methods 22:285-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reppert, S. M., and D. R. Weaver. 2002. Coordination of circadian timing in mammals. Nature 418:935-941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rochaix, J. D. 2002. Chlamydomonas, a model system for studying the assembly and dynamics of photosynthetic complexes. FEBS Lett. 529:34-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sambrook, J., E. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed., p. 18.15. Cold spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y.

- 35.Staiger, D., L. Zecca, W. D. A. Kirk, K. Apel, and L. Eckstein. 2003. The circadian clock regulated RNA-binding protein AtGRP7 autoregulates its expression by influencing alternative splicing of its own pre-mRNA. Plant J. 33:361-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudol, M., and T. Hunter. 2000. New wrinkles for an old domain. Cell 103:1001-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Takahashi, N., N. Sasagawa, K. Suzuki, and S. Ishiura. 2000. The CUG-binding protein binds specifically to UG dinucleotide repeats in a yeast three-hybrid system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 277:518-523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Timchenko, L. T., N. A. Timchenko, C. T. Caskey, and R. Roberts. 1996. Novel proteins with binding specificity for DNA CTG repeats and RNA CUG repeats: implications for myotonic dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 5:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wagner, V., M. Fiedler, C. Markert, M. Hippler, and M. Mittag. 2004. Functional proteomics of circadian expressed proteins from Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. FEBS Lett. 559:129-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waltenberger, H., C. Schneid, J. O. Grosch, A. Bareiss, and M. Mittag. 2001. Identification of target mRNAs from C. reinhardtii for the clock-controlled RNA-binding protein Chlamy 1. Mol. Genet. Genomics 265:180-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yang, Y., P. Cheng, Q. He, L. Wang, and Y. Liu. 2003. Phosphorylation of FREQUENCY protein by casein kinase II is necessary for the function of the Neurospora circadian clock. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23:6221-6228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]