Abstract

Schizosaccharomyces pombe utilizes two opposing signaling pathways to sense and respond to its nutritional environment. Glucose detection triggers a cyclic AMP signal to activate protein kinase A (PKA), while glucose or nitrogen starvation activates the Spc1/Sty1 stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK). One process controlled by these pathways is fbp1+ transcription, which is glucose repressed. In this study, we isolated strains carrying mutations that reduce high-level fbp1+ transcription conferred by the loss of adenylate cyclase (git2Δ), including both wis1− (SAPK kinase) and spc1− (SAPK) mutants. While characterizing the git2Δ suppressor strains, we found that the git2Δ parental strains are KCl sensitive, though not osmotically sensitive. Of 102 git2Δ suppressor strains, 17 strains display KCl-resistant growth and comprise a single linkage group, carrying mutations in the cgs1+ PKA regulatory subunit gene. Surprisingly, some of these mutants are mostly wild type for mating and stationary-phase viability, unlike the previously characterized cgs1-1 mutant, while showing a significant defect in fbp1-lacZ expression. Thus, certain cgs1− mutant alleles dramatically affect some PKA-regulated processes while having little effect on others. We demonstrate that the PKA and SAPK pathways regulate both cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription, providing a mechanism for cross talk between these two antagonistically acting pathways and feedback regulation of the PKA pathway. Finally, strains defective in both the PKA and SAPK pathways display transcriptional regulation of cgs1+ and pka1+, suggesting the presence of a third glucose-responsive signaling pathway.

Eukaryotic cells employ a variety of signal transduction pathways to regulate growth and developmental responses to changes in their environment. Often, more than one signal transduction pathway regulates a given biological process. Signals generated by one pathway may moderate the function of other signaling pathways, a phenomenon referred to as cross talk. Alternatively, signaling pathways may act independently to produce a regulatory outcome.

The fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe regulates many growth and developmental processes in response to nutrient conditions through the action of two opposing signal transduction pathways. Glucose triggers the activation of adenylate cyclase, resulting in a cyclic AMP (cAMP) signal, which activates the cAMP-dependent protein kinase A (PKA) (3, 15, 24). Nutrient starvation activates a stress-activated protein kinase (SAPK) pathway, which is also activated by osmotic, oxidative, and heat stress (8, 10, 31, 34). Cells lacking adenylate cyclase (git2+/cyr1+) display characteristics of glucose-starved cells even while growing in nutrient-rich conditions in that they efficiently mate and sporulate and they actively transcribe the fbp1+ gene, which is normally subject to glucose repression (15, 23). Cells carrying mutations affecting the Wis1 SAPK kinase (SAPKK) or the Spc1/Sty1 SAPK fail to respond to stress resulting in temperature-sensitive and osmotically sensitive growth and stationary-phase inviability (8, 37). These mutants are also conjugation defective, presumably due to the inability to transmit nutrient starvation signals (33, 34).

Several proteins acting downstream of the PKA and SAPK pathways to regulate fbp1+ transcription have been identified. The bZIP transcriptional activator Atf1 is phosphorylated and activated by the Spc1 SAPK and forms a heterodimeric complex with Pcr1, which is involved in response to osmotic stress, high-level oxidative stress, and nutrient starvation (19, 35, 39, 40). Electrophoretic mobility shift assays demonstrated that the Atf1-Pcr1 dimer binds to an fbp1+ control element, UAS1, and that this binding activity is positively regulated by the SAPK pathway and negatively regulated by the PKA pathway (29). A second control element, UAS2 (29), resembles the budding yeast stress response element (STRE) (25) and is bound by the Rst2 zinc finger protein, which is negatively regulated by PKA (13, 22). Finally, fbp1+ transcription is negatively regulated by a pair of partially redundant homologs of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tup1 corepressor (20, 41), Tup11 and Tup12, and positively regulated by the CCAAT box-binding factor (14, 18, 28).

In an effort to identify additional genes involved in nutrient monitoring and fbp1+ transcriptional regulation, we isolated strains carrying suppressor mutations that reduce the unregulated transcription of an fbp1-ura4+ reporter conferred by a git2 deletion (git2Δ). Although complementation analyses produced ambiguous results, we were able to identify mutations in the wis1+ SAPKK gene and the spc1+/sty1+ SAPK gene by phenotypic and linkage analyses. A third linkage group appeared to identify a novel gene based on the fact that while transcription of an fbp1-lacZ reporter was greatly reduced in these strains, mating competence and stationary-phase viability were largely unaffected. However, these strains turn out to carry unusual alleles of cgs1+, encoding the PKA regulatory subunit. We show that transcription of both cgs1+ and pka1+ are positively regulated by the SAPK pathway and negatively regulated by the PKA pathway, thus mimicking fbp1+ transcriptional regulation, though to a lesser degree. Remarkably, strains lacking adenylate cyclase and carrying a mutation in either wis1+ or spc1+ display glucose-repressible regulation of cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription, although the absolute levels are reduced. This observation suggests that additional mechanisms outside of these two signaling pathways exist to regulate transcription with respect to carbon source.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Yeast strains, media, and genetic tests.

S. pombe strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. The fbp1::ura4+ allele is a translational fusion that disrupts the fbp1+ gene, and the ura4::fbp1-lacZ allele is a disruption of the ura4+ gene by the fbp1-lacZ translational fusion (16). The git2::LEU2+ (15), git2::his7+ (1), and wis1::LEU2+ (37) gene deletions have been previously described. Standard rich media YEA and YEL (12) were supplemented with 2% Casamino Acids. PM (S. pombe minimal) medium (38) was supplemented with required nutrients at a concentration of 75 mg/liter, except for l-leucine, which was added to a concentration of 150 mg/liter. Media contained 3% glucose for standard culturing of cells, 8% glucose for culturing of cells under glucose-repressed conditions, and 0.1% glucose plus 3% glycerol for culturing of cells under derepressing conditions. Unless otherwise noted, all strains were grown at 30°C. Sensitivity to 5-fluoroorotic acid (5-FOA) was determined on synthetic complete (SC), SC-Leu, SC-Ade-Leu, and SC-His solid media containing 8% glucose, 50 mg of uracil/liter, and 0.4 g of 5-FOA/liter (16). Crosses were carried out on either malt extract agar (12) containing 0.4% glucose or synthetic sporulation agar (12). Dominance-recessiveness tests and complementation tests were carried out as previously described (16).

TABLE 1.

List of strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| 972 h− | |

| FWP101 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 |

| FWP185 | h90ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 cgs1-1 |

| FWP190 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+ |

| FWP193 | h+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 his7-366 git2::LEU2+cgs1-1 |

| CHP483 | h90ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 |

| CHP551 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his7-366 git2::his7+ |

| CHP720 | h−ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 wis1::LEU2+ |

| CHP725 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 sty1-1 |

| CHP742 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 his7-366 git2::LEU2+cgs1-1 |

| JSP2 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+wis1-2 |

| JSP3 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+wis1-3 |

| JSP4 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+wis1-4 |

| JSP10 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+cgs1-10 |

| JSP12 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+spc1-12 |

| JSP13 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+spc1-13 |

| JSP29 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 his7-366 git2::LEU2+wis1-29 |

| JSP102 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his7-366 git2::his7+spc1-102 |

| JSP109 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his7-366 git2::his7+spc1-109 |

| JSP163 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his7-366 git2::his7+wis1-163 |

| JSP180 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his7-366 git2::his7+cgs1-180 |

| JSP205 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his7-366 git2::his7+cgs1-205 |

| JSP215 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his7-366 cgs1-205 |

| JSP216 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 lys1-131 his3-D1 cgs1-205 |

| JSP220 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 his7-366 his3-D1 git2::his7+cgs1-10 |

| JSP227 | h−fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M216 his7-366 his3-D1 git2::his7+cgs1-180 |

| JSP230 | h90fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ leu1-32 ade6-M210 cgs1-10 |

| RJP1 | h+fbp1::ura4+ura4::fbp1-lacZ ade6-M216 leu1-32 his3-D1 his7-366 git2::his7+cgs1+ |

Isolation of suppressor mutations.

Colonies of adenylate cyclase deletion strains FWP190 and CHP551 (Table 1) (15) were patched to medium containing 5-FOA and incubated at 30°C for up to 21 days. Patches were observed daily for evidence of colony formation. 5-FOA-resistant colonies were single-colony purified and retested on 5-FOA-containing medium. Only one colony per patch was selected to ensure independence of the suppressor mutations. In order to verify that 5-FOA-resistant colonies had reduced levels of transcription from the fbp1+ promoter, β-galactosidase activity expressed from an fbp1-lacZ reporter was assayed. Strains that were 5-FOA resistant and determined to have at least a twofold reduction in β-galactosidase activity were further analyzed.

β-Galactosidase assays.

Strains were grown in YEL or PM medium under glucose-repressing conditions (8% glucose) to exponential phase (approximately 107 cells/ml). Cells were subcultured under repressing (8% glucose) or derepressing (0.1% glucose plus 3% glycerol) conditions and grown for 24 h to a final cell density of 5 × 106 to 1 × 107 cells/ml. Protein extracts were prepared and assayed for β-galactosidase activity as previously described. Total soluble protein in the extracts was determined by bicinchoninic acid assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.). The final values represent specific activity per milligram of soluble protein.

Cloning of cgs1+.

Strains JSP216 (cgs1-205) and JSP220 (cgs1-10) were transformed to His+ on PM-His (8% glucose) medium with an S. pombe genomic library in plasmid pBG2 (30). Transformants were replica plated to PM-His medium containing 3% potassium gluconate as the sole carbon source to screen for plasmids that restored gluconate transport, which is regulated in a manner similar to that of fbp1+ transcription (4). Approximately 1.0 × 105 His+ transformants were screened, and candidates that grew on gluconate-based media were single-colony purified. β-Galactosidase assays were performed on candidate transformants to identify those in which fbp1-lacZ expression was elevated under repressing conditions. Candidate plasmids were rescued into Escherichia coli by the Smash and Grab method (17) for plasmid purification and used to retransform JSP220. DNA sequence analysis of four independently isolated plasmids that restore constitutive gluconate utilization and fbp1-lacZ expression showed that all the plasmids carried the cgs1+ gene. A fifth plasmid that conferred gluconate utilization, but only weakly elevated fbp1-lacZ expression, was shown to carry the sak1+ gene (43).

Gap repair cloning of mutant alleles of cgs1+.

To facilitate gap repair cloning of mutant alleles of the cgs1+ gene, a deletion derivative of pJS29 (cgs1+) was created by digestion with BsrGI and SnaBI blunting of the BsrGI sticky end by Klenow fill-in and by ligation with T4 DNA ligase (New England Biolabs) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The plasmid was designated pJS29D.

Gap repair of mutant alleles of cgs1+ from strains JSP216 (cgs1-205), JSP220 (cgs1-10), and JSP227 (cgs1-180) was accomplished by digesting pJS29D with SnaBI to linearize the plasmid and by transforming the host strains to His+ on PM-His (8% glucose). Plasmids were recovered from purified colonies into E. coli and digested with SacI to confirm gap repair. The cgs1+ allele present in CHP551 was also cloned by gap repair and sequenced to determine whether the putative mutation observed in both the cgs1-10 and cgs1-205 alleles was present in the original parental strains. This was accomplished by mating JSP217 (cgs1-10 his3-D1 git2-2::his7+) by CHP551 (cgs1+ his3+ git2-2::his7+) to produce strain RJP1 (cgs1+ his3-D1 git2-2::his7+). The resulting gap-repaired plasmids pJS10, pJS180, pJS205, and pJS551 were sequenced by using ABI Big Dye Terminators on an ABI 377XL automated sequencer (Bioserve Biotechnologies, Ltd., Laurel, Md.) with custom oligonucleotides used to completely sequence both strands from approximately 370 base pairs upstream from the cgs1+ start codon to 400 base pairs downstream from the cgs1+ stop codon.

PCR analysis of the cgs1+ transcription unit.

To determine whether the mutation found in cgs1-10 and cgs1-205 was upstream or downstream from the cgs1+ transcriptional start site, PCR was carried out with either strain 972 genomic DNA or SPLE1 cDNA library DNA (18) by using the Failsafe PCR system (Epicentre, Madison, Wis.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Oligonucleotides F1 (5′ AGTCAGGGCATTGCGTAGTAC 3′, beginning 300 bp upstream from the cgs1+ start codon), F2 (5′ CTTGTGGTTGATTAAAGTGTCAGG 3′, beginning 124 bp upstream from the cgs1+ start codon), and F3 (5′ GAAAAGCTGAAAGCTGAGCG 3′, beginning 94 bp downstream from the cgs1+ start codon) were used in combination with R1 (5′ GGGTAATATTTAGTTCGGGCCT 3′, beginning 866 bp downstream from the cgs1+ start codon in the genomic DNA and 601 bp downstream of the cgs1+ start codon in the cDNA).

Northern hybridization analysis.

RNA samples were prepared from exponential-phase cultures grown in YE5S (YE medium supplemented with adenine, leucine, uracil, histidine, and lysine at 225 mg/liter) containing either 8% glucose (repressing conditions) or 0.1% glucose plus 3% glycerol (derepressing conditions) as previously described (11). RNA analysis was performed as follows: a 10- to 15-μg sample of total RNA was denatured with glyoxal, separated on a 1.2% agarose gel prepared in 15 mM sodium phosphate (pH 6.5), and transferred to a GeneScreen hybridization membrane (Dupont NEN Research Products). The his3+ probe has been described previously (2). Other gene-specific probes were produced by PCR amplification from genomic DNA with the appropriate primers. All probes were labeled with [α-32P]dCTP by using a Prime-a-Gene labeling kit (Promega). Analysis of mRNA levels was achieved by using a BAS1500 Phosphoimager (Fuji) and TINA analysis software.

RESULTS

Isolation of extragenic suppressors of an adenylate cyclase deletion.

Cells carrying an adenylate cyclase deletion (git2Δ) are defective in glucose detection and are derepressed for glucose-repressed processes including fbp1+ transcription, sexual development, and gluconate transport (4, 15, 23). The constitutive expression of an fbp1-ura4+ reporter fusion in a git2Δ strain confers sensitivity to 5-FOA in a glucose-rich medium, whereas cells that are able to glucose-repress fbp1-ura4+ transcription or are defective in fbp1-ura4+ transcription are 5-FOA resistant (Fig. 1). We have identified a collection of extragenic suppressors of the adenylate cyclase deletion by selecting for 5-FOA-resistant derivatives of strains FWP190 and CHP551 and by screening candidates for reduced β-galactosidase expression from an fbp1-lacZ reporter fusion integrated at the ura4+ locus (see Materials and Methods) (Fig. 1). From this selection and screen, we have identified 102 strains in which expression of the fbp1+ promoter-driven reporters is reduced anywhere from 2- to 100-fold. The general designation nft (nonderepressible fbp1+ transcription) was given to the genes identified by these suppressor mutations.

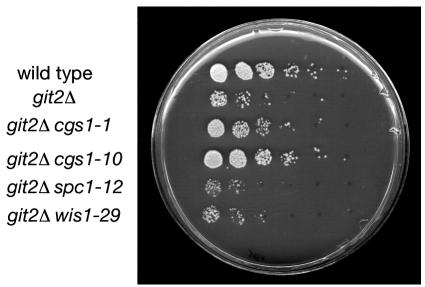

FIG. 1.

Phenotypic analysis of adenylate cyclase deletion and nft− suppressor strains. Approximately 105 cells of strains FWP101 (wild type [w.t.]), FWP190 (git2Δ), JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10), JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12), and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) were spotted to the indicated growth medium and photographed after 3 days of growth (5 days for the YEA plus gluconate plate).

Dominance-recessiveness and complementation testing of suppressor mutants.

Initial attempts to characterize the adenylate cyclase suppressor mutations involved dominance-recessiveness and complementation tests. For 83 of the 102 nft− strains, most, but not all, diploid colonies obtained by mating a git2Δ nft+ strain and a git2Δ nft− strain were 5-FOA sensitive, indicating that these nft− mutations are recessive (data not shown). For 15 strains, most, but not all, of the diploid colonies produced were 5-FOA resistant, indicating that these nft− mutations are dominant or semidominant. For the remaining four strains, we were unable to identify diploid colonies to test dominance or recessiveness.

Complementation tests of recessive nft− mutants were carried out in the same manner as the dominance-recessiveness test except that diploid strains were constructed by mating two recessive git2Δ nft− strains. All crosses produced both 5-FOA-resistant and 5-FOA-sensitive diploid colonies, preventing the assignment of complementation groups. Even subsequent efforts with strains known to carry wis1−, spc1−, or cgs1− mutant alleles that suppress the adenylate cyclase deletion failed to give clear complementation results (data not shown).

To address whether gene conversion contributed to the presence of 5-FOA-resistant diploids in all of the complementation tests, we revisited the fact that some 5-FOA-resistant diploids were obtained in crosses of git2Δ nft+ and git2Δ nft− that largely produced 5-FOA-sensitive diploids. If these rare diploid 5-FOA-resistant colonies had undergone a gene conversion event, then all four progeny should inherit the nft− mutant allele. Tetrad dissection revealed that progeny from such 5-FOA-resistant diploids were all 5-FOA resistant (nft−), while progeny from the 5-FOA-sensitive diploids formed by the same mating mixture segregated 2:2 for growth on 5-FOA-containing medium. Thus, it is likely that gene conversion is partly responsible for the heterogeneous growth of the diploids, which prevented us from placing the nft− suppressor mutations into complementation groups.

Identification of wis1− and spc1− mutants among the git2Δ suppressor strains.

Previous studies from our laboratory and others have uncovered a requirement for the Spc1 SAPK pathway in the derepression of fbp1+ transcription (7, 34). In addition to a defect in fbp1+ transcription, strains carrying mutations in the wis1+ SAPKK gene or the spc1+ SAPK gene display temperature-sensitive and osmotically sensitive growth and a mating defect (8, 27, 32, 33). Our mutant strain collection includes nine temperature-sensitive strains that morphologically resemble wis1− or spc1− mutants. These strains are also defective in the use of gluconate as a carbon source, consistent with either the loss of SAPK activation or the hyperactivation of PKA (Fig. 1, 4, and 5). Linkage analyses show that JSP12, JSP13, JSP102, and JSP109 carry mutations tightly linked to the sty1-1 mutant allele of spc1+, while JSP2, JSP3, JSP4, JSP29, and JSP163 carry mutations tightly linked to the wis1Δ::LEU2+ deletion allele. For example, tetrad dissection of crosses of JSP12 with CHP725 (sty1-1) and of JSP29 with CHP720 (wis1Δ::LEU2+) produced 13 and 18 parental ditype tetrads, respectively (0:4 for growth at 37°C). In addition, tetrad dissection of strain JSP12 or JSP29 crossed with strain CHP551 (git2Δ) showed that the suppressor mutation segregated 2:2 in the cross and cosegregated with the temperature-sensitive phenotype (data not shown). We have therefore been able to use linkage analyses to identify strains carrying suppressor mutations in the spc1+ SAPK gene and the wis1+ SAPKK gene in our mutant collection.

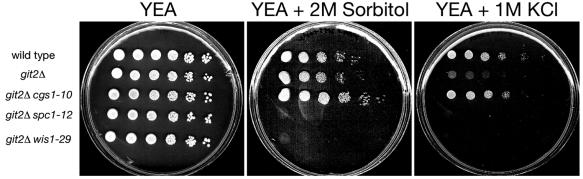

FIG. 4.

Characterization of mutants for salt-sensitive versus osmotically sensitive growth. Strains FWP101 (wild type), FWP190 (git2Δ), JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10), JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12), and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) were grown in YEL liquid medium to exponential phase and adjusted to 107 cells/ml. Five fivefold serial dilutions were carried out, and 4 μl of each culture was spotted onto YEA, YEA plus 2 M sorbitol, and YEA plus 1 M KCl plates. The plates were photographed after 3 days of growth.

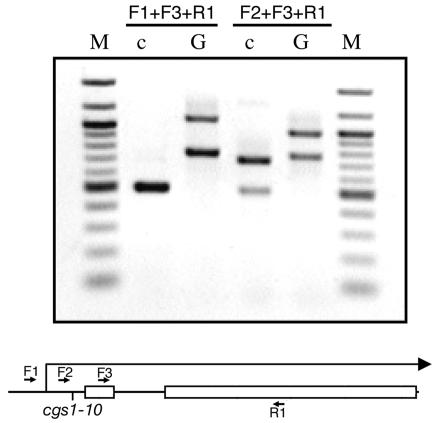

FIG. 5.

PCR analysis of cgs1+ transcriptional start site. The schematic shows exons 1 and 2 of cgs1+ (open boxes), the intervening intron, the relative locations to which the three forward (F1, F2, and F3) and one reverse (R1) PCR primers bind, and the site of the nucleotide altered by the cgs1-10 mutation. PCR was carried out with two forward primers and one reverse primer, as indicated above the lanes. Template DNA was either genomic DNA from strain 972 (lanes labeled G) or plasmid DNA from the SPLE1 cDNA library (lanes labeled c). The PCR products were subjected to electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel, with a 100-bp ladder (lanes labeled M) as a size standard.

The adenylate cyclase deletion (git2Δ) confers salt-sensitive, but not osmotically sensitive, growth.

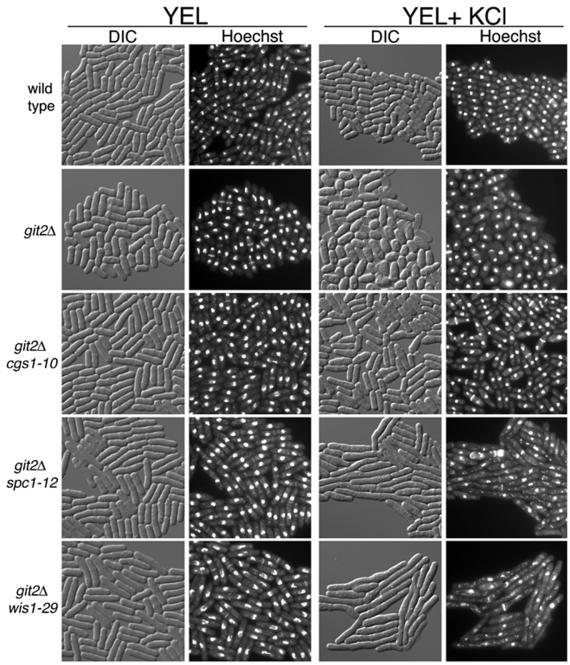

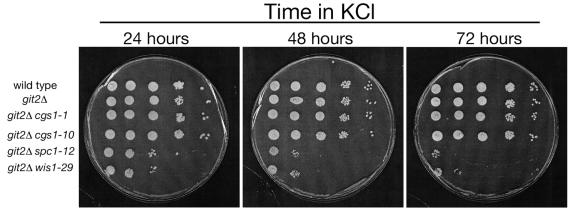

While screening the nft− mutant strains for temperature-sensitive and osmotically sensitive growth, we were surprised to see that the parental git2Δ strains themselves were severely defective for growth on YEA medium containing 1 M KCl (Fig. 1). However, microscopic examination of cells grown in YEL plus 1 M KCl for 24 h showed that unlike JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12) and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29), cells that elongate and die, cells of the parental strain FWP190 (git2Δ) appear to simply arrest growth (Fig. 2). This finding was confirmed by spot tests for viable cells grown in YEL medium with 1 M KCl and then plated onto YEA medium. JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12) and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) cells showed a rapid loss of viability when plated out on YEA medium (no added KCl), while FWP190 (git2Δ) cells remained fully viable even after 3 days of exposure to KCl, during which time the growth of the cells remained arrested (Fig. 3). Under the same conditions, cells of strains FWP101 (git2+) and JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10) showed no growth defect or loss of viability in medium containing 1 M KCl (Fig. 1 to 3).

FIG. 2.

Microscopic examination of cells after 24 h of growth in the presence of 1 M KCl. Strains FWP101 (wild type), FWP190 (git2Δ), JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10), JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12), and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) were grown to exponential phase in YEL liquid medium and then subcultured for 24 h in YEL in the presence or absence of 1 M KCl. Cells were stained with 1 μg of Hoechst 33342 stain/ml to stain the DNA prior to photographing.

FIG. 3.

Survival of S. pombe strains in the presence of 1 M KCl. Strains FWP101 (wild type), FWP190 (git2Δ), CHP742 (git2Δ cgs1-1), JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10), JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12), and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) were grown to exponential phase in YEL liquid medium and subcultured at 2 × 107 cells/ml in YEL plus 1 M KCl. After 24, 48, and 72 h, cells were washed with YEL medium and adjusted to 2 × 107 cells/ml along with four 10-fold serial dilutions. Five microliters of each culture was spotted to a YEA plate and grown for 3 days before photographing.

Cells exposed to 1 M KCl are subjected to both osmotic stress and salt stress. To determine whether the growth defect seen in FWP190 (git2Δ) cells is due to a defect in either osmotic stress response or salt stress response, we compared the growth of these strains on YEA medium containing 2 M sorbitol (osmotic stress without salt stress) to the growth on YEA medium containing 1 M KCl (both osmotic and salt stress). As seen in Fig. 4, the FWP190 (git2Δ) cells can grow in the presence of 2 M sorbitol, which is lethal to JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12) and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) cells. Therefore, the loss of adenylate cyclase appears to confer a salt-sensitive, but not an osmotically sensitive, growth defect.

Identification of KCl-resistant, mating-competent nft− mutants.

Of the 102 nft− suppressor mutants, 17 displayed modest to vigorous growth in the presence of 1 M KCl (data not shown). Of these 17 mutants, 15 showed no obvious defect in conjugation or sporulation, suggesting that they represent mutations in genes other than the cgs1+ PKA regulatory subunit gene and the genes of the SAPK pathway. Crosses of strains JSP10, JSP180, and JSP205 with git2Δ strains FWP190 or CHP551 showed that these suppressor mutations segregated as a single nuclear mutation. Pairwise crosses involving all 17 mutants produced only parental ditype tetrads (only 5-FOA-resistant progeny), indicating that these mutations comprised a single linkage group. Strain JSP10 (nft-10) was chosen as a representative of this linkage group for further analysis due to its high level of osmotically resistant growth (Fig. 1 to 3) and mating competence.

nft-10, nft-180, and nft-205 are alleles of cgs1+.

Strains carrying mutations in the linkage group that includes nft-10 are defective in utilizing gluconate as a carbon source, presumably due to a defect in gluconate transport (Fig. 1). This is not surprising, as previous studies have shown that gluconate transport is positively regulated by the SAPK pathway and negatively regulated by glucose through the PKA pathway (4, 5). To clone the gene defective in JSP10, we constructed strains JSP216 (nft-205 git2Δ his3-D1) and JSP220 (nft-10 git2Δ his3-D1) and screened a genomic library in pBG2 (30) for plasmids able to restore growth on PM-His with 3% gluconate as the carbon source. From approximately 100,000 His+ transformants, 92 transformants were identified as being able to utilize gluconate as a carbon source. β-Galactosidase assays of fbp1-lacZ expression in the candidate transformants identified four plasmids that fully suppressed the nft-205 or nft-10 mutation and one plasmid that partially suppressed the nft-10 mutation (data not shown). These plasmids were rescued into E. coli and subjected to DNA sequence analysis. All four plasmids that conferred complete suppression carry the cgs1+ gene, while plasmid pJS6, which partially suppresses the nft-10 mutation, carries the sak1+ gene (43).

To investigate whether the KCl-resistant nft− mutations represent unusual alleles of cgs1+ (in that most of the strains are mating competent) or whether cgs1+ was cloned as a multicopy suppressor, we crossed strain JSP215 (nft-205) by strain FWP193 (cgs1-1) to determine whether these mutations are genetically linked. The 22 tetrads examined were all parental ditypes, in that none of the progeny could grow on YEA plus gluconate or PM plus gluconate medium, thus placing nft-205 and cgs1-1 within 2.3 cM of each other.

To directly determine if these nft− mutations fall within the cgs1+ gene, we constructed a plasmid to facilitate the gap repair of the cgs1 alleles from these mutant strains (see Materials and Methods). Plasmid pJS29D was linearized with SnaBI and used to transform strains JSP220, JSP216, and JSP227 in order to rescue the cgs1 alleles from strains carrying the nft-10, nft-205, and nft-180 mutations. The transformants carrying the gap-repaired plasmid were sensitive to 5-FOA, indicating that the plasmid-borne allele of cgs1 could suppress the nft− mutation (data not shown). In contrast, transformants carrying the pJS29D plasmid remained 5-FOA resistant and failed to grow on PM plus gluconate medium due to the host nft− mutation.

Sequence analysis of the cloned alleles of cgs1 indicated that nft-10 and nft-205 are identical, displaying the same C-to-A transversion. Surprisingly, the altered nucleotide is 95 nucleotides upstream from the translational start codon. To test whether this might represent an unrelated single-nucleotide polymorphism in our strain background, we crossed the wild-type cgs1+ allele from strain CHP551 into a his3-D1 background and repeated the gap repair cloning of this cgs1+ allele. Sequence analysis showed a C in this position, consistent with the sequence from the S. pombe genome project (42). Sequence analysis of the nft-180 allele identified a T-to-A transversion, changing codon 86 from a leucine to a stop codon. We have therefore renamed these alleles as cgs1-10, cgs1-205, and cgs1-180.

While the cgs1-10 mutation falls outside of the open reading frame, it creates a potential out-of-frame ATG start codon for a nine-codon open reading frame that would terminate only 65 nucleotides from the authentic cgs1+ start codon. Alternatively, this nucleotide may be part of a cis-acting element required for cgs1+ transcription. We therefore examined whether this nucleotide falls within the cgs1+ transcription unit by carrying out PCR on genomic DNA and on DNA from the SPLE1 cDNA library (18), as shown in Fig. 5. PCR was performed by using a forward primer (F3) that is internal to exon 1 as a control and an upstream experimental forward primer (F1 or F2) to identify the approximate 5′ end of the transcription unit. As shown in Fig. 5, when either pair of forward primers is combined with a reverse primer (R1), internal to exon 2, two bands are produced when genomic DNA is used (lanes marked G). In contrast, PCRs with the SPLE1 cDNA library (lanes marked c) as a template produce only one band in the F1+F3+R1 reaction and two bands in the F2+F3+R1 reaction. Therefore, the transcriptional start site appears to be between the sites to which the F1 and F2 primers anneal. The F2 primer binds immediately upstream of the site of the cgs1-10 mutation; thus, this mutation falls within the 5′ untranslated region and most likely exerts its effect by creating a novel translational start site that reduces translation from the authentic translational start site.

cgs1-10 mutants are conjugation proficient and viable in stationary phase, but are severely defective in fbp1-lacZ expression.

As mentioned above, our preliminary characterization of the cgs1− mutants in our strain collection led us to believe that these strains carried mutations in a gene other than cgs1+, as most strains failed to display characteristics associated with the cgs1-1 allele. These phenotypes include a severe conjugation defect and a rapid loss of viability in stationary phase (9). We therefore reexamined these phenotypes in both cgs1-1 and cgs1-10 strains to determine whether there is indeed a difference in their effects on various PKA-regulated processes. For our conjugation assay (Table 2), we also examined the effects of pregrowing cells on YEA rich medium versus PM defined medium and of mating done on malt extract agar complex medium versus synthetic sporulation agar defined medium. For wild-type cells, all combinations of pregrowth and mating media produce similar high-efficiency mating. For cgs1-1 mutant cells, pregrowth on YEA medium results in a nearly 100-fold loss of mating efficiency, as expected. More surprisingly, we found that pregrowth of the cgs1-1 strain on PM medium reduces the mating efficiency defect to only fourfold (Table 2). Consistent with our preliminary observation, cgs1-10 cells display a nearly wild-type level of mating when pregrown on PM medium, although there is about a 10-fold reduction in mating for cells pregrown on YEA medium. To test for stationary-phase viability, we cultured strains in YEL liquid medium for 7 to 14 days before plating for viable cells in a spot assay. Figure 6 shows a typical result from cells grown for 9 days before plating was done. Unexpectedly, FWP190 git2Δ cells show reduced viability relative to FWP101 wild-type cells. CHP742 (git2Δ cgs1-1) cells show a partial loss of viability, while JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10) cells remain fully viable, consistent with our initial observation. Finally, JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12) and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) cells show the most severe loss in viability. We have carried out similar studies with git2+ cgs1-1 and git2+ cgs1-10 cells. Both strains show a reduction in viability with respect to the wild-type control strain, with the defect being more pronounced in the cgs1-1 strain than in the cgs1-10 strain (data not shown). Therefore, in both a git2Δ and a git2+ background, the cgs1-1 mutation causes a greater loss of viability in stationary phase than does the cgs1-10 mutation.

TABLE 2.

Effect of cgs1+ mutations and growth media on conjugation efficiencya

| Genotype | % Conjugation

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| YEA to SPA | YEA to MEA | PM to SPA | PM to MEA | |

| Wild type | 57.9 ± 8.2 | 59.0 ± 8.4 | 70.2 ± 9.9 | 75.6 ± 2.9 |

| cgs1-1 | 0.5 ± 0.1 | 0.8 ± 0.5 | 15.7 ± 6.7 | 18.7 ± 7.4 |

| cgs1-10 | 5.0 ± 3.2 | 5.3 ± 3.6 | 56.5 ± 9.3 | 60.6 ± 8.4 |

Homothallic strains CHP483 (cgs1+), FWP185 (cgs1-1) and JSP230 (cgs1-10) were pregrown on the indicated solid medium for 24 h before mating. Cells were collected and adjusted to 109 cells/ml before spotting 10 μl to the indicated mating medium. After 27 h, cells were collected, and the numbers of vegetative cells, zygotes, and asci were determined for 200 to 1,200 cells (depending upon the efficiency of mating). Each ascus or zygote was counted as two cells. The values represent the average ± the standard deviation from four independent experiments.

FIG. 6.

Stationary-phase viability assay. Strains FWP101 (wild type), FWP190 (git2Δ), CHP742 (git2Δ cgs1-1), JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10), JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12), and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) were grown to exponential phase in YEL liquid medium and subcultured at 107 cells/ml in YEL liquid medium and grown for 9 days, after which cultures were adjusted to 8 × 107 cells/ml. Five fivefold serial dilutions were carried out, and 4 μl of each culture was spotted onto YEA. The plates were photographed after 3 days of growth.

Our examination of the mating phenotype and the stationary-phase viability phenotype associated with the cgs1-10 and cgs1-1 mutations suggests that the cgs1-10 mutation has a lesser effect on Cgs1 function than does the cgs1-1 mutation. We therefore compared their ability to reduce the high level of fbp1-lacZ expression conferred by an adenylate cyclase deletion (Table 3). As we observed a difference in the mating efficiency of such mutants depending on the growth media (Table 2), we carried out β-galactosidase assays for cells grown in either YEL or PM liquid medium. In either medium, the cgs1-1 and cgs1-10 mutations confer an equivalent defect in fbp1-lacZ expression (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Effect of mutations in git2+ and cgs1+ on fbp1-lacZ expressiona

| Strain | Relevant genotype | β-Galactosidase activity

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cells grown in YEL

|

Cells grown in PM

|

||||

| Repressed | Derepressed | Repressed | Derepressed | ||

| FWP101 | git+ | 23 ± 4 | 1,492 ± 232 | 9 ± 1 | 1,586 ± 83 |

| FWP190 | git2Δ | 3,002 ± 928 | 3,602 ± 696 | 1,513 ± 168 | 1,853 ± 253 |

| CHP742 | git2Δ cgs1-1 | 17 ± 2 | 64 ± 8 | 3 ± 0 | 11 ± 2 |

| JSP10 | git2Δ cgs1-10 | 10 ± 3 | 44 ± 8 | 4 ± 1 | 23 ± 10 |

β-Galactosidase activity was determined from two to four independent cultures as described in Materials and Methods. The average ± standard error represent specific activity per mg of soluble protein.

cgs1+ and pka1+ are transcriptionally regulated by the PKA and SAPK pathways.

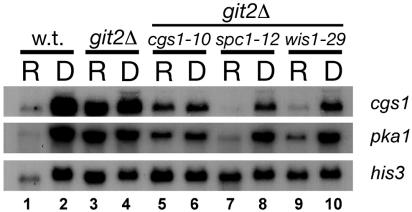

The differential effect of the cgs1-10 mutation on fbp1-lacZ expression relative to mating efficiency and stationary-phase viability led us to examine transcriptional regulation of cgs1+ and pka1+ under different growth conditions and in different mutant backgrounds. We hypothesized that the cgs1-10 mutation, which presumably reduces Cgs1 translation, may have a greater effect when this allele is transcribed at a low level than when its transcription is elevated. We therefore examined whether cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription is regulated by glucose and the involvement, if any, of the PKA and SAPK pathways. As shown in Fig. 7 (lanes 1 and 2), we observed that both cgs1+ and pka1+ are transcriptionally induced by glucose starvation. This regulation is lost in both git2Δ cells (lanes 3 and 4), which show high levels of expression regardless of carbon source, and in git2Δ cgs1-10 cells (lanes 5 and 6), which show reduced levels of expression regardless of carbon source. Thus, PKA activity appears to negatively regulate both cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription, possibly serving as a feedback mechanism to reduce PKA activity subsequent to glucose detection and cAMP signaling. Meanwhile, the SAPK signaling pathway positively regulates transcription of these genes, as the loss of either Spc1 or Wis1 activity results in an overall reduction of transcription, although the severalfold regulation is similar to that seen in wild-type cells (Fig. 7, lanes 7 to 10). These results suggest that there is cross talk between these two nutrient detection pathways, but that a third glucose-responsive regulatory mechanism must exist.

FIG. 7.

Transcription of cgs1+ and pka1+ in strains defective in PKA or SAPK signaling. Strains FWP101 (wild type), FWP190 (git2Δ), JSP10 (git2Δ cgs1-10), JSP12 (git2Δ spc1-12), and JSP29 (git2Δ wis1-29) were grown to exponential phase in YE5S liquid medium containing either 8% glucose (lanes labeled R) or 0.1% glucose with 3% glycerol (lanes labeled D). The RNA was isolated and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have isolated a large number of strains carrying mutations that suppress the loss of adenylate cyclase in fission yeast. While characterizing the suppressor mutations for additional phenotypes such as sterility, osmotic sensitivity, and temperature sensitivity, we found that the parental git2Δ strains are unable to grow on media containing 1 M KCl. The sensitivity of cAMP pathway mutants to KCl has also been noted in a study by Yang et al. (44) on the role of the phospholipase B homolog Plb1, whose loss confers phenotypes similar to those of adenylate cyclase mutants and is suppressed by the overexpression of genes such as gpa2+ and git3+ that are required for the activation of adenylate cyclase. As we have shown here, the cAMP pathway mutants are not actually osmotically sensitive but are salt sensitive. A reexamination of the growth phenotypes of a plb1Δ strain reveals that, similar to cAMP pathway defects, the loss of Plb1 confers salt sensitivity and not osmotic sensitivity (C. S. Hoffman, unpublished data). It is quite possible that other S. pombe mutants that are thought to display osmotically sensitive growth are actually only salt sensitive.

The ability of cgs1− mutations to suppress the KCl-sensitive growth conferred by an adenylate cyclase deletion was unexpected in that for many phenotypes, cgs1− mutants behave similarly to SAPK pathway mutants. Strains carrying mutations in cgs1+, wis1+, or spc1+/sty1+ have been shown to be defective in mating, stationary-phase viability, and fbp1+ transcription, although cgs1− mutants do not display the temperature-sensitive growth phenotype seen in wis1− and spc1− mutants (9, 15, 33, 34, 37). Based on the morphology of wis1−, spc1−, and adenylate cyclase mutants after exposure to KCl (Fig. 2), we propose the following model for the roles of the SAPK and PKA kinases in response to KCl stress. As previously shown, KCl stress leads to the phosphorylation and activation of the Spc1/Sty1 SAPK (27, 32), which presumably causes a growth arrest such that wis1− or spc1− mutants continue to grow in the presence of KCl, leading to rapid cell death of elongated cells (Fig. 2 and 3). During the growth arrest, wild-type cells modulate gene expression or protein activities to permit growth without a loss of viability. PKA activity is required for this resumption of growth such that adenylate cyclase mutants arrest growth upon exposure to KCl but then fail to resume growing while remaining viable (Fig. 2 and 3).

While cloning cgs1+, we also cloned the sak1+ gene as a weak multicopy suppressor of the cgs1-10 mutation. The sak1+ gene encodes an essential DNA binding protein and was originally identified in fission yeast as a multicopy suppressor of the mating defect conferred by the cgs1-1 allele (43). In that study, overexpression of sak1+ slightly increased fbp1-lacZ expression in a cgs1-1 strain, but these transformants did not respond to glucose starvation with a further increase in expression. Therefore, the significance of Sak1 function in fbp1+ transcription is unclear.

We have shown that the cgs1-10 and cgs1-1 mutations confer equivalent defects in fbp1-lacZ expression (Table 3) while causing significantly different effects on mating efficiency (Table 2) and stationary-phase viability (Fig. 6). Thus, these PKA-regulated processes appear to be sensitive to different levels of kinase activity, as has been shown for various processes in budding yeast spore morphogenesis that are controlled by the Smk1 kinase (36). Presumably, the cgs1-1 allele, for which the sequence of the mutation is not known, results in a greater loss of Cgs1 function and therefore a greater activation of PKA than does the cgs1-10 allele, which retains a wild-type coding region. Processes such as conjugation and stationary-phase viability may require a higher level of PKA activity to confer a mutant phenotype, allowing one to distinguish between the cgs1-1 and cgs1-10 alleles, while fbp1+ transcriptional regulation may be more sensitive to the increase in PKA activity conferred by either cgs1-1 or cgs1-10. Alternatively, differences in cgs1 transcription may affect the degree to which the cgs1-10 mutation, which is likely to reduce the translation of an otherwise wild-type Cgs1 protein, alters PKA activity. The assay of fbp1-lacZ expression is carried out on exponentially growing cells, while the conjugation and stationary-phase viability assays are not. Indeed, previous microarray studies show that transcription of cgs1+ and pka1+ are coordinately induced during meiosis (26) and in response to a variety of stresses (6). These changes in the transcription of cgs1+ and pka1+ may allow cells to modulate PKA activity in a cAMP-independent manner. In addition, such transcriptional regulation may vary the degree to which the cgs1-10 mutation in the 5′ untranslated region affects Cgs1 activity as a function of growth conditions. This is due to the fact that the cgs1-10 and cgs1-180 alleles appear to encode partially functional products, as the overexpression of these alleles in gap-repaired transformants confers 5-FOA-resistant growth, a reflection of reduced fbp1-ura4 expression. Since the mutation in the cgs1-180 allele creates a stop codon at codon 86, it is likely that some readthrough occurs to allow the translation of a reduced amount of a functional product, similar to the proposed effect of the cgs1-10 mutation.

To examine the possibility that transcriptional regulation of cgs1+ might account for differential effects of the cgs1-10 mutation on PKA-regulated processes, we examined cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription in cells growing under glucose-rich and glucose-starved conditions. We found that cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription is regulated by glucose and by the PKA and SAPK pathways (Fig. 7), thus resembling fbp1+ transcriptional regulation at a qualitative level but not at a quantitative level. For all three genes, PKA acts to repress transcription, while the SAPK activity is required for high levels of transcription. However, unlike cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription, fbp1+ transcription varies on the order of 200-fold depending upon the carbon source (15, 16). It may be that cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription is controlled by a subset of the regulatory mechanisms that control fbp1+ transcription, including the Atf1-Pcr1 bZIP transcriptional activator, the CCAAT-binding factor, the Rst2 activator and Scr1 repressor zinc finger proteins, and the Tup11 and Tup12 corepressors (13, 14, 18, 29, 35). It should also be noted that the reduction of cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription under repressing conditions due to spc1− or wis1− mutation suggests that the basal level of SAPK signaling is sufficient for high-level transcription of these genes and that the activation of the SAPK pathway may not be required for transcriptional derepression of cgs1+, pka1+, or fbp1+. Alternatively, a loss of adenylate cyclase may lead to the activation of the Spc1/Sty1 SAPK under nonstress conditions allowing a wis1− or spc1− mutation to alter transcription in glucose-rich grown cells. However, such activation does not appear to be at the level of SAPK phosphorylation, which is similar in wild-type cells and PKA pathway mutants, including a git2Δ mutant (I. Samejima and P. Fantes, personal communication). It remains possible that the cAMP pathway mutations increase the nuclear localization of Spc1 without substantially changing its phosphorylation state, thus stimulating Spc1-dependent transcription.

As the cgs1-10 mutation caused a loss of regulation of cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription, it is likely that the differential effects of this mutation on fbp1+ transcription, mating, and stationary-phase viability are more a reflection of the different sensitivities of these processes to PKA activity than of changes in cgs1+ transcription under different growth conditions. In addition, our Northern blot analysis (Fig. 7) showed that mutations in the SAPK pathway genes cause a greater reduction in cgs1+ transcription than in pka1+ transcription. This may lead to a relative increase in the ratio of the PKA catalytic subunits to regulatory subunits, thus increasing PKA activity in the absence of cAMP and suggests that SAPK activity can negatively regulate PKA activity in a cAMP-independent manner.

The regulation of cgs1+ and pka1+ transcription observed in git2Δ spc1-12 and git2Δ wis1-29 strains (Fig. 7, lanes 7 to 10) is consistent with data from work by Stettler et al. (34), who showed that fbp1+ transcription is still regulated, though to a reduced extent, in strains carrying a deletion of wis1+ in combination with either a git2+ deletion or a pka1-261 point mutation. These studies suggest that at least one glucose-responsive mechanism acts in a PKA- and SAPK-independent manner. It is therefore possible that additional glucose signaling pathways and/or transcriptional regulators remain to be discovered in fission yeast and may be identified by the genes affected in the remaining uncharacterized nft− mutants present in our strain collection.

Unfortunately, our analysis of the genes identified in this mutant hunt was hampered by our inability to place these mutants into complementation groups. This was due to the heterogeneous growth of diploid strains constructed for both the dominance-recessiveness test and the complementation test. Problems with the assignment of dominance and recessiveness of alleles in fission yeast, though not well documented, are not uncommon. As such, S. pombe genetic nomenclature utilizes only lowercase letters in gene names (21), unlike budding yeast genetic nomenclature, which utilizes uppercase and lowercase letters to indicate dominant and recessive alleles, respectively. In addition, many fission yeast studies have used linkage analyses only to assign mutations to gene groups, as we did with the spc1− and wis1− mutants in our collection. Thus, it is likely that we will have to analyze the remaining members of this strain collection by linkage analyses with strains carrying mutations in candidate genes rst2+, atf1+, pcr1+, and the php genes encoding subunits of the CCAAT box-binding factor that are known positive regulators of fbp1+ transcription (13, 18, 29, 35) in an effort to identify whether any novel genes are represented among these adenylate cyclase suppressor strains.

Acknowledgments

We thank Peter Fantes and Anthony Annunziato for stimulating discussions and Itaru Samejima and Peter Fantes for sharing unpublished data.

This work was supported by a Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council project grant to S.K.W. (13/P11981) and by National Institutes of Health grant GM46226 to C.S.H.

REFERENCES

- 1.Apolinario, E., M. Nocero, M. Jin, and C. S. Hoffman. 1993. Cloning and manipulation of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe his7+ gene as a new selectable marker for molecular genetic studies. Curr. Genet. 24:491-495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baum, B., J. Wuarin, and P. Nurse. 1997. Control of S-phase periodic transcription in the fission yeast mitotic cycle. EMBO J. 16:4676-4688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Byrne, S. M., and C. S. Hoffman. 1993. Six git genes encode a glucose-induced adenylate cyclase activation pathway in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Cell Sci. 105:1095-1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caspari, T. 1997. Onset of gluconate-H+ symport in Schizosaccharomyces pombe is regulated by the kinases Wis1 and Pka1, and requires the gti1+ gene product. J. Cell Sci. 110:2599-2608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caspari, T., and S. Urlinger. 1996. The activity of the gluconate-H+ symporter of Schizosaccharomyces pombe cells is down-regulated by D-glucose and exogenous cAMP. FEBS Lett. 395:272-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen, D., W. M. Toone, J. Mata, R. Lyne, G. Burns, K. Kivinen, A. Brazma, N. Jones, and J. Bahler. 2003. Global transcriptional responses of fission yeast to environmental stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 14:214-229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dal Santo, P., B. Blanchard, and C. S. Hoffman. 1996. The Schizosaccharomyces pombe pyp1 protein tyrosine phosphatase negatively regulates nutrient monitoring pathways. J. Cell Sci. 109:1919-1925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Degols, G., K. Shiozaki, and P. Russell. 1996. Activation and regulation of the Spc1 stress-activated protein kinase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2870-2877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeVoti, J., G. Seydoux, D. Beach, and M. McLeod. 1991. Interaction between ran1+ protein kinase and cAMP dependent protein kinase as negative regulators of fission yeast meiosis. EMBO J. 10:3759-3768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaits, F., G. Degols, K. Shiozaki, and P. Russell. 1998. Phosphorylation and association with the transcription factor Atf1 regulate localization of Spc1/Sty1 stress-activated kinase in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 12:1464-1473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Greenall, A., A. P. Hadcroft, P. Malakasi, N. Jones, B. A. Morgan, C. S. Hoffman, and S. K. Whitehall. 2002. Role of fission yeast Tup1-like repressors and Prr1 transcription factor in response to salt stress. Mol. Biol. Cell 13:2977-2989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gutz, H., H. Heslot, U. Leupold, and N. Loprieno. 1974. Schizosaccharomyces pombe, p. 395-446. In R. C. King (ed.), Handbook of genetics. Plenum Press, New York, N.Y.

- 13.Higuchi, T., Y. Watanabe, and M. Yamamoto. 2002. Protein kinase A regulates sexual development and gluconeogenesis through phosphorylation of the Zn finger transcriptional activator Rst2p in fission yeast. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22:1-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirota, K., C. S. Hoffman, T. Shibata, and K. Ohta. 2003. Fission yeast Tup1-like repressors repress chromatin remodeling at the fbp1+ promoter and the ade6-M26 recombination hotspot. Genetics 165:505-515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman, C. S., and F. Winston. 1991. Glucose repression of transcription of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe fbp1 gene occurs by a cAMP signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 5:561-571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoffman, C. S., and F. Winston. 1990. Isolation and characterization of mutants constitutive for expression of the fbp1 gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Genetics 124:807-816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hoffman, C. S., and F. Winston. 1987. A ten-minute DNA preparation from yeast efficiently releases autonomous plasmids for transformation of Escherichia coli. Gene 57:267-272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Janoo, R. T., L. A. Neely, B. R. Braun, S. K. Whitehall, and C. S. Hoffman. 2001. Transcriptional regulators of the Schizosaccharomyces pombe fbp1 gene include two redundant Tup1p-like corepressors and the CCAAT binding factor activation complex. Genetics 157:1205-1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kanoh, J., Y. Watanabe, M. Ohsugi, Y. Iino, and M. Yamamoto. 1996. Schizosaccharomyces pombe gad7+ encodes a phosphoprotein with a bZIP domain, which is required for proper G1 arrest and gene expression under nitrogen starvation. Genes Cells 1:391-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keleher, C. A., M. J. Redd, J. Schultz, M. Carlson, and A. D. Johnson. 1992. Ssn6-Tup1 is a general repressor of transcription in yeast. Cell 68:709-719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kohli, J. 1987. Genetic nomenclature and gene list of the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Curr. Genet. 11:575-589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kunitomo, H., T. Higuchi, Y. Iino, and M. Yamamoto. 2000. A zinc-finger protein, Rst2p, regulates transcription of the fission yeast ste11+ gene, which encodes a pivotal transcription factor for sexual development. Mol. Biol. Cell 11:3205-3217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maeda, T., N. Mochizuki, and M. Yamamoto. 1990. Adenylyl cyclase is dispensable for vegetative cell growth in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:7814-7818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maeda, T., Y. Watanabe, H. Kunitomo, and M. Yamamoto. 1994. Cloning of the pka1 gene encoding the catalytic subunit of the cAMP-dependent protein kinase in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 269:9632-9637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marchler, G., C. Schuller, G. Adam, and H. Ruis. 1993. A Saccharomyces cerevisiae UAS element controlled by protein kinase A activates transcription in response to a variety of stress conditions. EMBO J. 12:1997-2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mata, J., R. Lyne, G. Burns, and J. Bahler. 2002. The transcriptional program of meiosis and sporulation in fission yeast. Nat. Genet. 32:143-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Millar, J. B., V. Buck, and M. G. Wilkinson. 1995. Pyp1 and Pyp2 PTPases dephosphorylate an osmosensing MAP kinase controlling cell size at division in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 9:2117-2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mukai, Y., E. Matsuo, S. Y. Roth, and S. Harashima. 1999. Conservation of histone binding and transcriptional repressor functions in a Schizosaccharomyces pombe Tup1p homolog. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19:8461-8468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neely, L. A., and C. S. Hoffman. 2000. Protein kinase A and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways antagonistically regulate fission yeast fbp1 transcription by employing different modes of action at two upstream activation sites. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20:6426-6434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohi, R., A. Feoktistova, and K. L. Gould. 1996. Construction of vectors and a genomic library for use with his3− deficient strains of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Gene 174:315-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samejima, I., S. Mackie, and P. A. Fantes. 1997. Multiple modes of activation of the stress-responsive MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. EMBO J. 16:6162-6170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shiozaki, K., and P. Russell. 1995. Cell-cycle control linked to extracellular environment by MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Nature 378:739-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shiozaki, K., and P. Russell. 1996. Conjugation, meiosis, and the osmotic stress response are regulated by Spc1 kinase through Atf1 transcription factor in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 10:2276-2288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stettler, S., E. Warbrick, S. Prochnik, S. Mackie, and P. Fantes. 1996. The wis1 signal transduction pathway is required for expression of cAMP-repressed genes in fission yeast. J. Cell Sci. 109:1927-1935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Takeda, T., T. Toda, K. Kominami, A. Kohnosu, M. Yanagida, and N. Jones. 1995. Schizosaccharomyces pombe atf1+ encodes a transcription factor required for sexual development and entry into stationary phase. EMBO J. 14:6193-6208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wagner, M., P. Briza, M. Pierce, and E. Winter. 1999. Distinct steps in yeast spore morphogenesis require distinct SMK1 MAP kinase thresholds. Genetics 151:1327-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warbrick, E., and P. A. Fantes. 1991. The wis1 protein kinase is a dosage-dependent regulator of mitosis in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. EMBO J. 10:4291-4299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Watanabe, Y., Y. Lino, K. Furuhata, C. Shimoda, and M. Yamamoto. 1988. The S. pombe mei2 gene encoding a crucial molecule for commitment to meiosis is under the regulation of cAMP. EMBO J. 7:761-767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Watanabe, Y., and M. Yamamoto. 1996. Schizosaccharomyces pombe pcr1+ encodes a CREB/ATF protein involved in regulation of gene expression for sexual development. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:704-711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilkinson, M. G., M. Samuels, T. Takeda, W. M. Toone, J. C. Shieh, T. Toda, J. B. Millar, and N. Jones. 1996. The Atf1 transcription factor is a target for the Sty1 stress-activated MAP kinase pathway in fission yeast. Genes Dev. 10:2289-2301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Williams, F. E., U. Varanasi, and R. J. Trumbly. 1991. The CYC8 and TUP1 proteins involved in glucose repression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae are associated in a protein complex. Mol. Cell. Biol. 11:3307-3316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wood, V., R. Gwilliam, M. A. Rajandream, M. Lyne, R. Lyne, A. Stewart, J. Sgouros, N. Peat, J. Hayles, S. Baker, D. Basham, S. Bowman, K. Brooks, D. Brown, S. Brown, T. Chillingworth, C. Churcher, M. Collins, R. Connor, A. Cronin, P. Davis, T. Feltwell, A. Fraser, S. Gentles, A. Goble, N. Hamlin, D. Harris, J. Hidalgo, G. Hodgson, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, S. Howarth, E. J. Huckle, S. Hunt, K. Jagels, K. James, L. Jones, M. Jones, S. Leather, S. McDonald, J. McLean, P. Mooney, S. Moule, K. Mungall, L. Murphy, D. Niblett, C. Odell, K. Oliver, S. O'Neil, D. Pearson, M. A. Quail, E. Rabbinowitsch, K. Rutherford, S. Rutter, D. Saunders, K. Seeger, S. Sharp, J. Skelton, M. Simmonds, R. Squares, S. Squares, K. Stevens, K. Taylor, R. G. Taylor, A. Tivey, S. Walsh, T. Warren, S. Whitehead, J. Woodward, G. Volckaert, R. Aert, J. Robben, B. Grymonprez, I. Weltjens, E. Vanstreels, M. Rieger, M. Schafer, S. Muller-Auer, C. Gabel, M. Fuchs, A. Dusterhoft, C. Fritzc, E. Holzer, D. Moestl, H. Hilbert, K. Borzym, I. Langer, A. Beck, H. Lehrach, R. Reinhardt, T. M. Pohl, P. Eger, W. Zimmermann, H. Wedler, R. Wambutt, B. Purnelle, A. Goffeau, E. Cadieu, S. Dreano, S. Gloux, et al. 2002. The genome sequence of Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Nature 415:871-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu, S. Y., and M. McLeod. 1995. The sak1+ gene of Schizosaccharomyces pombe encodes an RFX family DNA-binding protein that positively regulates cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated exit from the mitotic cell cycle. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:1479-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang, P., H. Du, C. S. Hoffman, and S. Marcus. 2003. The phospholipase B homolog Plb1 is a mediator of osmotic stress response and of nutrient-dependent repression of sexual differentiation in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe. Mol. Genet. Genomics 269:116-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]