SUMMARY

Mammalian cells possess mechanisms to detect and defend themselves from invading viruses. In the cytosol, the RIG-I-like receptors (RLRs), RIG-I (retinoic acid-inducible gene I; encoded by DDX58) and MDA5 (melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5; encoded by IFIH1) sense atypical RNAs associated with virus infection1,2. Detection triggers a signalling cascade via the adaptor MAVS that culminates in the production of type I interferons (IFN-α/β; hereafter IFN), key antiviral cytokines. RIG-I and MDA5 are activated by distinct viral RNA structures and much evidence indicates that RIG-I responds to RNAs bearing a triphosphate (ppp) moiety in conjunction with a blunt-ended, base-paired region at the 5′-end (reviewed in 1-3). Here we show that RIG-I also mediates antiviral responses to RNAs bearing 5′-diphosphates (5′pp). Genomes from mammalian reoviruses with 5′pp termini, 5′pp-RNA isolated from yeast L-A virus, and base-paired 5′pp-RNAs made by in vitro transcription or chemical synthesis, all bind to RIG-I and serve as RIG-I agonists. Furthermore, a RIG-I-dependent response to 5′pp-RNA is essential for controlling reovirus infection in cultured cells and in mice. Thus, the minimal determinant for RIG-I recognition is a base-paired RNA with 5′pp. Such RNAs are found in some viruses but not uninfected cells, indicating that recognition of 5′pp-RNA, like that of 5′ppp-RNA, acts as a powerful means of self/non-self discrimination by the innate immune system.

RIG-I contributes to IFN production by cells infected with reovirus or transfected with the double-stranded (ds)RNA segments of the reovirus genome4-7. Short stretches of dsRNA have been thought to be responsible5 but this is hard to reconcile with the fact that RIG-I activation depends on its C-terminal domain (CTD), which caps RNA ends rather than folding over stems8-11. The CTD contains a pocket that accommodates 5′ppp-RNA allowing for extensive interactions with the α- and β-phosphates but, interestingly, less so with the γ-phosphate8,9,11. Furthermore, an earlier RIG-I CTD structure showed a complex with a 5′ di-rather than tri-phosphate RNA, possibly as a result of 5′ppp-RNA hydrolysis during crystallisation11. Notably, all 10 reovirus genome segments display a free 5′pp on the [-] strand as a result of triphosphate processing by a viral phosphohydrolase12 (also see Supplementary Fig. 1 and Extended Text for Supplementary Fig. 1). We therefore hypothesized that a 5′pp blunt-ended, base-paired RNA such as found in reovirus genomic RNA can bind RIG-I and serve a physiological agonist for antiviral immunity.

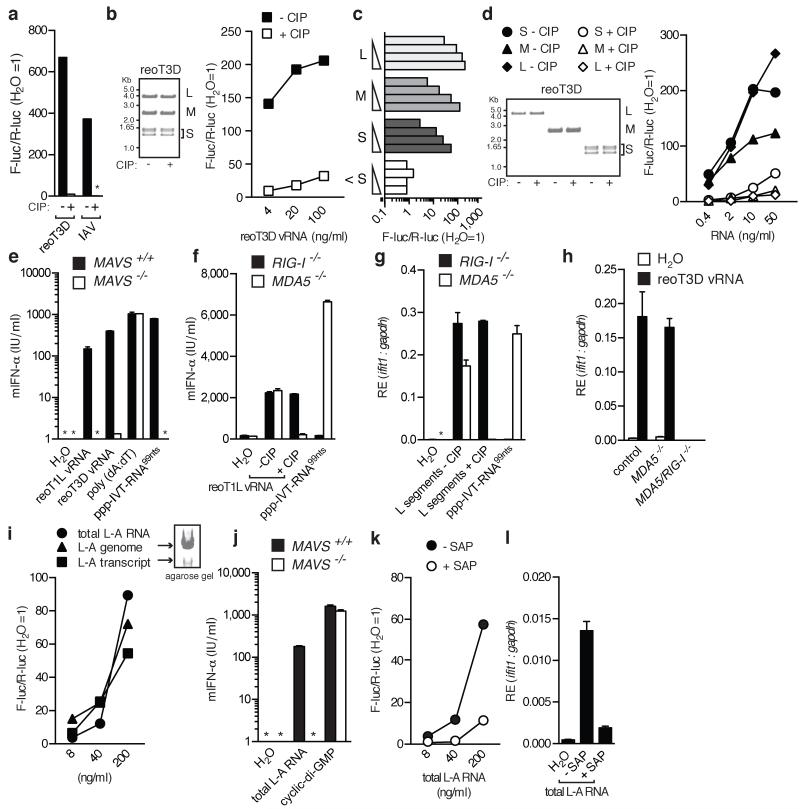

First, we assessed the 5′-phosphate-dependence of stimulation by reovirus RNA. RNA extracted from cells infected with reovirus strain type 3 Dearing (reoT3D) or isolated from reoT3D virus particles (viral RNA; vRNA) induced the expression of an IFN-β reporter gene following transfection into HEK293 cells (Fig. 1a, b). Calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP; Fig. 1a, b) treatment substantially reduced the stimulatory activity of reovirus vRNA, like it did of RNA from IAV-infected cells, a known 5′ppp-dependent RIG-I stimulus13,14. Similar results were obtained using reovirus strain type 1 Lang (reoT1L) and a distinct 5′-polyphosphatase (Extended data Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1i). The response to total reovirus vRNA could be recapitulated using purified large (L), medium (M), and small (S) genome segments (Fig. 1c, d and Extended data Fig. 1b) but not short (<20 residues, labeled <S; Fig. 1c) ssRNA oligonucleotides encapsidated within purified virions12.

Fig. 1. RNA from reovirus and L-A virus requires 5′-phosphates to induce a RIG-I-dependent response.

(a-d) RNA samples were tested in an IFN-β promoter reporter assay in HEK293 cells: (a) RNA from reoT3D- or IAV-infected cells +/−CIP, (b) reoT3D vRNA +/−CIP, (c) reoT1L genome segments, and (d) reoT3D segments +/− CIP. For (b) and (d), RNA integrity was verified by gel electrophoresis. (e) IFN-α levels from transfected DCs. (f-h) IFN-α levels (f) or relative expression (RE) of ifit1 (g-h) from control (MDA5+/−), RIG-I−/−, MDA5−/− or RIG-I/MDA5−/− MEFs transfected with reo vRNA (f,h) or isolated reoT1L L segments (g) +/− CIP. Water and ppp-IVT-RNA99nts are controls. For (e-h), cells were treated with ribavirin to block virus replication. (i) Total L-A RNA (genome and transcript), L-A genomes and L-A transcripts were analysed as in (a). (j) Total L-A RNA was analysed as in (e). (k-l) Total L-A RNA +/− shrimp alkaline phosphatase (SAP) was analysed as in (a) or transfected into MDA5−/− DCs and analysed as in (g). Water, ppp-IVT-RNA99nts, poly(dA:dT) and cyclic-di-GMP were included as controls. All experiments were performed at least twice. For PCR and IFN-α data, the mean (±s.d.) of triplicate technical replicates is shown (* = not detected).

The role of RIG-I versus MDA5 in responses to reovirus is unclear4-7. HEK293 cells used for reporter assays respond strongly to RIG-I agonists but poorly to triggers of MDA5 (data not shown). To dissect pathways involved in 5′pp-RNA recognition, we therefore switched to mouse cells (dendritic cells [DCs] or mouse embryonic fibroblasts [MEFs]) that display sensitivity to agonists of either RLR (Fig. 1e-h). RIG-I- or MDA5-deficient cells showed the expected loss of IFN-response to selective RIG-I or MDA5 agonists (ppp-IVT-RNA99nts or Vero-EMCV-RNA, respectively) but retained the capacity to respond to reovirus vRNA (Fig. 1f, g and data not shown). Abrogation of the response to reovirus vRNA was only observed in MAVS-deficient or RIG-I/MDA5 doubly-deficient MEFs (Fig. 1e, h)5. However, compensation in RIG-I-sufficient but MDA5-deficient (MDA5−/−) cells was lost upon vRNA treatment with phosphatase, even though the same treatment did not impact RIG-I−/− cells (Fig. 1f-g). Thus, when RIG-I is the dominant RLR (MDA5−/− mouse cells or HEK293 human cells), responses to reovirus RNA are sensitive to phosphatase treatment. These data indicate that reovirus genome segments can activate both MDA5 and RIG-I irrespective of their length but that 5′-diphosphates on the reovirus genome are required for RIG-I but not MDA5 activation. A role for 5′-diphosphate-moieties in RIG-I activation by viruses was further confirmed using the L-A totivirus, a dsRNA virus commonly found in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, that synthesises transcripts with a 5′pp terminus and is thought to harbour a genome with capped or diphosphate 5′-ends15,16 (Fig 1i-l and Extended Data Fig. 1c and d). Thus, 5′-diphosphate-bearing RNAs of two distinct viral origins act as agonists for RIG-I.

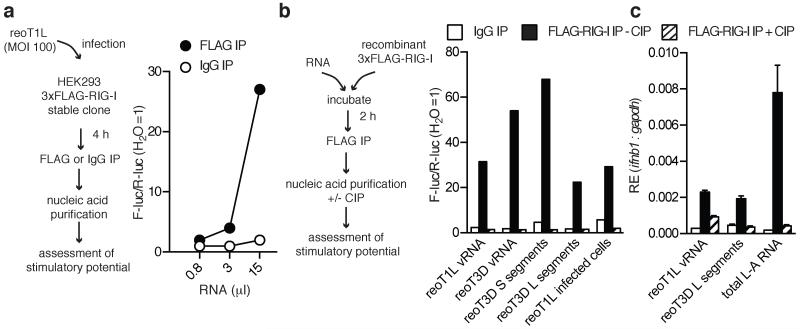

To determine whether RIG-I associates with 5′pp-containing viral RNA in infected cells, nucleic acids were purified from FLAG-tagged RIG-I that was precipitated from cells infected with either reoT1L or reoT3D. In both cases, we recovered stimulatory RNA from anti-FLAG but not from control immunoprecipitations (Fig. 2a and Extended Data Fig. 2). Similar results were obtained when recombinant FLAG-tagged-RIG-I was incubated with total reovirus vRNA, purified S and L segments or with L-A virus genomic and transcript RNA (Fig. 2b and c). In all cases, the stimulatory activity of RNA associated with RIG-I precipitates was lost after treatment with phosphatase (Fig. 2b and c). Thus, RIG-I can directly bind viral RNAs bearing 5′-diphosphates.

Fig. 2. RIG-I associates with 5′-diphosphate-bearing viral RNAs.

(a) Left, Experimental procedure. Right, IFN-β promoter reporter assay of RNA from RIG-I-precipitates. (b-c) (b, left) Experimental procedure using the following input RNA: reoT1L or reoT3D vRNA, reoT3D S or L segments, RNA isolated from reoT1L-infected cells, or total L-A RNA. (b, left) IFN-β promoter reporter assay or (b, right) ifnb1 expression from IFN-pre-treated MDA5−/− DCs (c) following transfection of RNA from RIG-I-precipitates treated +/−CIP. For PCR data, the mean (±s.d) of triplicate technical replicates is shown. All experiments were performed at least twice.

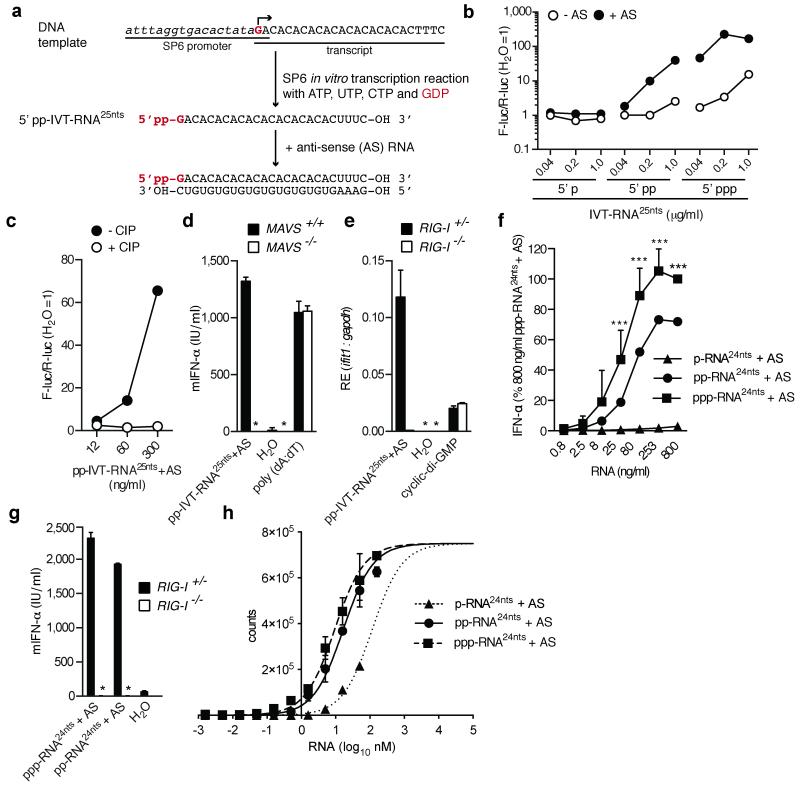

Previous data suggested that in vitro transcribed (IVT)-RNA with a 5′pp does not serve as a RIG-I agonist17. The IVT-RNA in question bore a single guanosine residue at the 5′ end to permit generation of 5′pp when GDP instead of GTP was included in the transcription reaction17. However, because transcriptional elongation requires a triphosphate-bearing nucleoside to form the phosphodiester bond, GDP also prevented the generation of the polymerase copy-back IVT base-paired by-products later demonstrated to be required for RIG-I stimulation18,19. We therefore re-synthesised the short 5′-diphosphate transcript (5′pp-IVT-RNA25nts) but this time annealed it to complementary (anti-sense [AS]) synthetic RNA to form the requisite base-paired structure (Fig. 3a). As expected18,19, a control 5′p-IVT-RNA25nts synthesised using GMP was not stimulatory independently of hybridisation to AS RNA (Fig. 3b). In contrast, the positive control 5′ppp-IVT-RNA25nts made with GTP was stimulatory even without AS annealing (Fig. 3b), as a consequence of the aforementioned by-products18,19. Most notably, 5′pp-IVT-RNA25nts was also stimulatory but only when annealed to the AS strand (Fig. 3b). Treatment with phosphatase resulted in a complete loss of stimulatory activity (Fig. 3c), demonstrating strict dependence on the 5′-diphosphate-moieties, and the response was MAVS and RIG-I dependent (Fig. 3d and e), as predicted. Stimulatory activity was preserved in gel purified 5′pp-IVT-RNA25nts+AS (data not shown) and the purity of all guanosine batches used to generate the 5′ mono-, di- or tri-phosphate IVT RNAs was verified by liquid-chromatography mass spectrometry (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Further excluding a role for contamination, no stimulatory RNA was generated even when a 5′p-IVT-RNA reaction was deliberately “spiked” with up to 10% GTP (Extended Data Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3. De novo generated base-paired 5′-diphosphate RNA triggers RIG-I.

(a) Experimental procedure used to generate 5′pp-IVT-RNA25nts. (b-c) IFN-β promoter reporter assay of IVT-RNA25nts+/−AS (b) and pp-IVT-RNA25nts+AS +/−CIP (c). (d-g) IFN-α levels (d,f,g) or ifit1 expression (e) from DCs (d) MEFs (e,g) or human PBMCs (f) transfected with indicated RNAs. Water, poly(dA:dT) or cyclic-di-GMP were included as controls (*not detected). For (f), the value obtained for 800ng/ml of [ppp-RNA24nts+AS] was set to 100%. Mean values (+s.d.) from four donors are shown (***P<0.0001). (h) AlphaScreen of RIG-I and synthetic RNA ligands (±s.d.). Units are proportional to RIG-I-ligand complex concentration. One experiment of two is shown.

To strengthen these observations, we chemically synthesised a 5′ppp-RNA of 24nts (5′ppp-RNA24nts)20 and subjected half of the sample to enzymatic hydrolysis of the γ-phosphate using the 5′-RNA triphosphatase activity of the vaccinia virus capping enzyme to generate 5′pp-RNA24nts. The purity of both 5′ppp-RNA24nts and 5′pp-RNA24nts was validated (Extended Data Fig. 3c) and the RNAs were annealed to AS RNA (+AS) and assessed for IFN-inducing ability. 5′pp-RNA24nts+AS was clearly stimulatory for both human and mouse cells in a RIG-I-dependent manner (Fig. 3f,g) and only 3-fold less active than the 5′ppp-RNA24nts+AS control (Fig. 3f). Binding assays showed that RIG-I has similar affinity for both RNAs (apparent Kd of 16.7 nM for 5′pp-RNA24nts+AS versus 9.4 nM for 5′ppp-RNA24nts+AS) but binds 5′p-RNA24nts+AS much more weakly (Fig. 3h). The latter also failed to induce IFN (Fig. 3f), consistent with reports that ligand binding is necessary but not sufficient for RIG-I activation10,21. Altogether, we conclude that, similar to natural 5′pp-containing viral RNA, man-made 5′pp-base-paired RNAs trigger a RIG-I-dependent response.

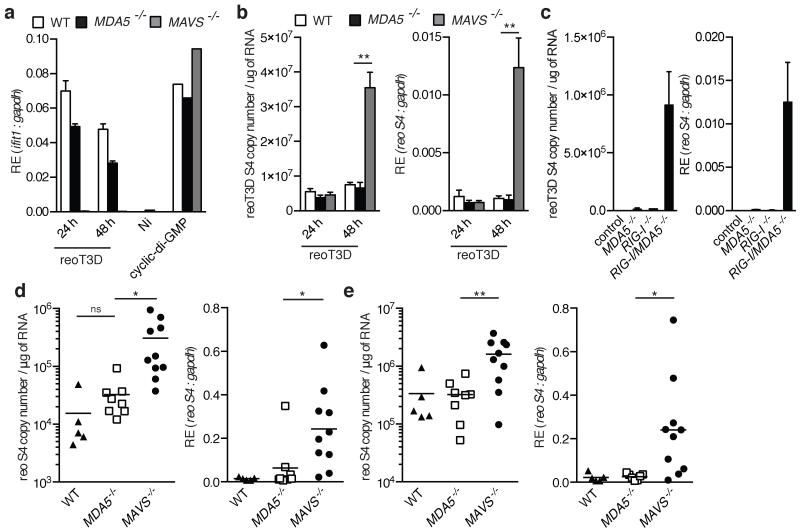

Lastly, to assess the physiological importance of our findings, we studied the innate immune response to reovirus infection in MDA5- or MAVS-deficient cells and mice. At 48 h post-infection, there was an increase in reoT3D S4 genome segment copy number in DCs incapable of responding to MDA5 or RIG-I agonists (MAVS−/−) compared with MDA5-deficient cells in which the RIG-I pathway is intact (Fig. 4a and b). As reported for MEFs6, the control of viral replication correlated with the respective capacity of MAVS−/− and MDA5−/− DCs to produce IFN following infection (Fig. 4a and b). Importantly, there was little difference between WT and MDA5−/− DCs, indicating that RIG-I alone can serve to control reovirus infection in these cells. This conclusion was confirmed using MEFs deficient for either or both RLRs, in which an increase in viral burden was only observed in RIG-I/MDA5-doubly deficient cells (Fig. 4c). Finally, MDA5−/− and MAVS−/− mice were perorally infected with reovirus. Reovirus replication in the intestine and the mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) was significantly greater in RIG-I-signaling-incompetent mice (MAVS−/−) compared with RIG-I-signaling-competent mice (MDA5−/−; Fig. 4d and e). Taken together, these data demonstrate that RIG-I can control the replication of reovirus, which bears a 5′-diphosphate dsRNA genome.

Fig. 4. RIG-I is required for control of reovirus infection.

(a-c) ifit1 (a) or reovirus gene segment S4 genome expression ([b-c], right panel) and copy number per μg of RNA ([b-c], left panel) in reoT3D infected DCs (a-b) or control (RIG-I+/−) MDA5−/−, RIG-I−/−, and MDA5/RIG-I−/− MEFs. Mean of triplicate biological replicates (±s.d.) is shown. Cyclic-di-GMP was included as a control. **P≤0.01 (unpaired t-test). (d-e) Abundance of reovirus gene segment S4 determined as in (b) from intestine (d) and MLN (e) of mice following peroral infection with reovirus strain T3SA+. Data were pooled from two experiments. Each symbol represents an individual mouse. Line represents the mean of each group. *P<0.03 and **P<0.008 (unpaired t-test).

The detection of virus infection is crucial for the successful initiation of innate and adaptive antiviral responses. Virus recognition can be mediated by RIG-I through the sensing of viral genomes bearing blunt-ended, base-paired termini with 5′-triphosphates1-3. Here, we show that a diphosphate at the 5′-end of blunt-ended, base-paired RNA is in fact sufficient to activate RIG-I. These findings provide physiological meaning to recent structural data demonstrating that the RIG-I CTD can accommodate both 5′pp and 5′ppp-RNA8,9,11. They also reiterate the importance of end-rather than stem-based recognition of RNA by RIG-I9,10,22 and thereby raise the possibility that some viral and synthetic 5′ppp-free RIG-I agonists bear a 5′pp-moiety that contributes to activity. In this regard, the commonly used IFN-inducing stimulus polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid (poly[I:C]) is a homopolymer synthesised from inosine and cytidine diphosphate likely to contain a certain proportion of 5′-ends bearing diphosphates (Extended Data Fig. 4a)23. We noticed that the stimulatory capacity of some batches of poly(I:C) can be decreased by phosphatase treament, especially when this is coupled with mild RNase treatment to free up strands (Extended Data Fig. 4b-c). A role for 5′-diphosphates in poly(I:C) and reovirus recognition by RIG-I offers an alternative explanation for the observation that short poly(I:C) or short reovirus RNA segments preferentially activate RIG-I versus MDA55. Rather than RIG-I and MDA5 detecting different dsRNA lengths, perhaps it is the ratio of 5′pp-ends to stems that dictates which RLR dominates in recognition. Notably, many viruses display 5′ppp-RNAs in infected cells as a result of utilising a primer-independent mechanism for RNA synthesis. However, viruses such as reoviruses and poxviruses24 encode 5′-RNA triphosphatases that catalyze hydrolysis of the γ-phosphate in viral genomes or primary transcripts to generate 5′pp-RNAs. In contrast, host cytosolic RNAs (mRNA, tRNA, or rRNA) are uniformly devoid of both 5′ppp- and 5′pp-structures25. Thus, the capacity of RIG-I to respond to base-paired RNAs with either a 5′ di- or tri-phosphate does not compromise self-nonself discrimination but extends the universe of viruses that can be detected by a single innate immune sensor.

METHODS

Reagents

Poly(dA:dT) (PO833) and ribavirin were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used at 500 ng/ml and 400 μM final concentration, respectively. Cyclic diguanosine monophosphate (cyclic-di-GMP) was purchased from BioLog Life Science Institute (Bremen, Germany) and used at a concentration of 1 μg/ml. Recombinant IFN-A/D was purchased from PBL Assay Science (Piscataway, NJ).

For production of recombinant RIG-I used in Fig. 2, the 3xFLAG-human RIG-I DNA sequence13 was amplified using forward primer 5′-actcgagttatggactacaaagaccatgacgg-3′ and reverse primer 5′-ttgcggccgctcatttggacatttctgctggatcaa-3′ and cloned into the pBacPAK-His3-GST plasmid. Recombinant 3xFLAG-human RIG-I was expressed as a GST-tagged protein in SF9 insect cells using a baculovirus expression system and purified in a single step by affinity chromatography using glutathione-sepharose matrix (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom). The protein was eluted by GST tag cleavage using 3C enzymatic digestion. A final polishing step was accomplished using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). Protein purity was verified by acrylamide gel electrophoresis, and protein yield was quantified using a Nanodrop apparatus (ThermoScientific, Waltham, MA).

Cells

All cells were mycoplasma negative and cultured using tissue-culture treated polystyrene plates (Falcon, Fisher Scientific International Inc., Hampton, NH) in an incubator with 5-10% CO2 and at 37 °C. HEK293 cells were provided by Dr. Friedemann Weber (Freiburg, Germany). Vero and L929 cells were obtained from Cancer Research UK Cell Services. Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Gibco®, Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) supplemented to contain 10% FCS (Autogen Bioclear UK, Ltd, Mile Elm, United Kingdom), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 U/ml streptomycin, and 0.3 μg/ml glutamine was used as growth medium. HEK293 cells stably expressing 3xFLAG-RIG-I have been described13. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF) bone marrow-derived DCs were prepared as described26. MDA5−/− and RIG-I−/− and littermate control MEFs were prepared from 12.5-day embryos using standard protocols. RIG-I/MDA5-deficient MEFs were generated by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome engineering27. A target sequence in the first exon of murine RIG-I (CTACATGAGTTCCTGGCTCG AGG [PAM motif underlined]) was chosen and appropriate oligonucleotides were cloned into the BbsI site of pX458 (pSpCas9(BB)-2A-GFP; obtained from the laboratory of Feng Zhang via Addgene (Cambridge, MA; plasmid 48138)) according to the cloning protocol provided by the Zhang lab (www.genome-engineering.org). MDA5-deficient MEFs immortalized with simian virus 40 large T antigen7 were transfected with the RIG-I targeting pX458 vector using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Twenty-four hours post-transfection, GFP-positive cells were FACS sorted and cultured at limiting dilution to pick individual colonies. The absence of functional RIG-I was verified in several clones by assessing loss of ifit1 induction by quantitative PCR following transfection of a known RIG-I agonist (ppp-IVT-RNA99nts). In experiments in which these RIG-I/MDA5-deficient MEFs were used, the parental immortalized MDA5−/− MEF line was included as control.

Human PBMCs were isolated as described11 from whole human blood of healthy, voluntary donors by Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Biochrom Berlin, Germany) and cultured in RPMI 1640 supplemented to contain 10% FCS, 1.5 mM L-glutamine, 100 U/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin.

Viruses

All infection work was carried out according to the requirements for handling biological agents in Advisory Committee on Dangerous Pathogens hazard groups. Reovirus strains type 1 Lang (T1L) and type 3 Dearing (T3D) were recovered by plasmid-based reverse genetics from cloned T1L and T3D cDNAs, respectively28. The reovirus strain T1L used for mass spectrometry analysis was a kind gift from Søren Paludan, Aarhus University, Denmark. For in vivo infections, the T3SA+ strain was used as it readily binds to sialic acid and enhances reovirus infection through adhesion to the cell surface29. Reovirus T3SA+ was generated by reassortment of reovirus strains T1L and type 3 clone 44-MA29. Virions were purified as described30. IAV strain A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 H1N1 was provided by Dr. Thomas Muster (University of Vienna, Austria), and EMCV was obtained from Dr. Ian Kerr.

Nucleic acid preparations

Reovirus genomic RNA was extracted from purified viral particles using TRIzol®LS (Life Technologies). L-A virus transcripts were generated by in vitro transcription using purified L-A virions as described15. Electrophoresis using 0.8% agarose gels in Tris/borate/EDTA buffer (89 mM Tris, 89 mM boric acid, 2 mM EDTA, pH 8.3) was used to separate reovirus L, M, S, and < S segments and L-A virus genomes from transcripts. Bands were visualized following ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich) staining using a UV transilluminator and a Dimage Xt digital camera (Minolta, Osaka, Japan). The 1Kb Plus DNA ladder from Life Technologies was used as a reference. RNA segments were purified from gels by adding one volume of UltraPure™ phenol (Life Technologies) per volume of gel and precipitated using ethanol. For mass spectrometry analysis, reovirus genome segments were purified by differential LiCl precipitation31. Single-stranded RNA was removed by addition of 2M LiCl, incubated overnight at 4°C and centrifugated at 16,000 rcf for 20 minutes. Subsequently, long dsRNA was precipitated by addition of LiCl to 4M final concentration. The final supernatant (4M LiCl), which contains small RNAs, was discarded. Purity and integrity of dsRNA-preparations was assessed using agarose gel electrophoresis followed by ethidium bromide staining.

For the isolation of RNA from reovirus infected cells, one 80% confluent 145 cm2 plate of L929 cells was infected at an MOI of 1 plaque forming unit (PFU)/cell. Forty-eight hours later, RNA was isolated using TRIzol® (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A similar protocol was used for the isolation of RNA from IAV or EMCV-infected Vero cells at 24 h post-infection. 800ng/ml of RNA was used for reporter assays.

ppp-IVT-RNA99nts, which corresponds to the first 99 nucleotides of the neomycin-resistance marker, was prepared using in vitro transcription as described13 and used at concentrations of 200-500 ng/ml. ppp-IVT-RNA933nts corresponds to 933 nucleotides of the Renilla luciferase coding sequence. The double-stranded ppp-IVT-RNA933nts was generated by annealing sense and anti-sense ppp-IVT-RNA933nts, respectively. To synthesise p-, pp-, and ppp-IVT-RNA25nts, DNA oligonucleotides sense [5′-AAAGGATCCATTTAGGTGACACTATAGACACACACACACACACACACTTTCTCGAGAAA-3′] and antisense [5′-TTTCTCGAGAAAGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTGTCTATAGTGTCACCTAAATGGATCCTTT-3′] were annealed and cloned into pcDNA3.1/V5-His-TOPO. The resulting plasmid was digested with XhoI and BglII (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA) and gel-purified (QIAquick Gel Extraction kit, QIAGEN). The in vitro transcription was carried out overnight at 37°C with Sp6 RNA polymerase (Sp6 MEGAscript kit, Ambion®, Life Technologies) using GMP, GDP, or GTP (purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Carbosynth (Compton, United Kingdom). After DNaseT1 treatment (Ambion) and size-exclusion purification (Illustra™ microspin G25 column; GE Healthcare), the RNA was purified using Ultra Pure™ phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol (25:24:1) (Life Technologies) and precipitated using ethanol. The purified RNA was annealed to a synthetic anti-sense RNA oligonucleotide (5′-GAAAGUGUGUGUGUGUGUGUGUGUC-3′; Sigma-Aldrich) by heating for 5 min at 65°C, followed by cooling to room temperature before storage at −20°C.

5′ppp-RNA24nts (GACGCUGACCCUGAAGUUCAUCUU) was synthesised chemically as described20. 5′pp-RNA24nts was generated by incubating 5′ppp-RNA24nts with vaccinia virus capping enzyme (Epicentre, Illumina, Madison, WI) for 3 h at 37°C in absence of GTP and S-adenosyl methionine, otherwise according to the manufactures protocol. 5′p-RNA24nts and AS RNA was derived from Biomers, (Ulm, Germany) or Eurogentec, (Seraing, Belgium). Quality control was performed by mass spectrometry as described11. MALDI ToF characterization of 5′ppp-RNA24nts and 5′pp-RNA24nts was performed and spectra were measured using a Bruker Biflex III with linear detection mode and a proprietary Sequenom matrix by Metabion/Martinsried (Germany). For stimulation assays, RNAs were annealed with non-modified oligos with complementary sequence.

Enzymatic treatment of RNA

CIP, SAP (New England Biolabs) and RNA 5′-polyphosphatase (Epicenter) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For Terminator nuclease (Epicenter) digestion, RNA was denaturated for 3 min at 98°C and immediately cooled on ice (melt and snap cool) after which Terminator N buffer and 1μl of Terminator nuclease with or without 0.5μl vaccinia virus capping enzyme were added. The mixture was incubated for 30 min at 30°C and another 30 min at 37°C. With all enzymatic treatments, control reactions omitting enzymes were carried out in parallel. RNA samples were recovered by extraction with phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol or TRIzol®. Nucleic acid pellets were resuspended in RNase/DNase free water (Ambion), and concentrations were measured using the Nanodrop (Thermo Scientific). ReoT3D vRNA samples treated with or without Terminator N were spiked with 10 μg of human RNA to ensure efficient precipitation and to quantify precipitation efficiency (qPCR of GAPDH, data not shown). For RNase T2 digestion of reovirus genome, 40 μg of RNA was diluted to 0.3 μg/μl and denatured by heating for 3 min to 90°C. Subsequently, the RNA was incubated with 150U of RNase T2 (MoBiTec GmbH, Göttingen, Germany) in 125 mM NH4Ac for 4 h at 37°C. To ensure a complete reaction, the digest was then heated for 60 sec at 90°C, another 150 U of RNase T2 were added and incubation was continued for 1 hour at 37°C. Quantitative digestion was verified by agarose gel electrophoresis and the digestion products were analysed by ESI-LC-MS.

Detection of IFN stimulatory activity

The IFN-β luciferase promoter reporter was employed as described13. Cells (1-2.5 × 105) were plated in 0.5 ml of antibiotic-free medium and transfected one day later with a mix of 0.125 μg of IFN-β luciferase promoter reporter (F-luc) and 0.025 μg of Renilla luciferase control (R-luc) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). After 8 h, various concentrations of samples (e.g., IVT-RNA) were transfected into cells using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase activity was quantified 24 h later using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System from Promega (Fitchburg, WI). Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase, and fold inductions were calculated relative to a control transfection with water only (F-luc/R-luc). 50, 10, 2, and 0.4 ng/ml of L, M, S and < S reovirus segments were used in reporter assays (Fig 1).

For assays using MEFs, 5 × 104 cells/well were plated into wells of 24-well plates and transfected with test or control RNAs using Lipofectamine 2000. After incubation overnight (16 h), murine IFN-α (multiple subtypes) in culture supernatants was quantified by ELISA as described32, or MEF RNA was extracted. A similar protocol was employed for assays using bone-marrow derived DCs. Where indicated, cells were IFN-pre-treated as a means to upregulate RLR-expression with 500 units/ml of IFN-A/D (PBL Assay Science) for 24 h. DCs were transfected with 200ng/ml of reoT1L or reoT3D vRNA or 100ng/ml of total L-A RNA.

For assay using PBMCs, 4 × 105 cells were cultured in 96-well plates for stimulation experiments. To inhibit TLR7/8 activity, cells were pre-incubated with 2.5μg/ml chloroquine for 30 min before transfection of RNA using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies). Human IFN-α levels in culture supernatants 20 h post-transfection were determined by ELISA as described11.

Quantitative PCR for ifnb1 and ifit1

For real-time quantitative (q)PCR of cell-culture samples, total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) combined with QIAshedder (Qiagen) and RNase-free DNaseI treatment (Qiagen). Mouse tissues (intestine and MLN) were first homogenized using stainless steel beads and the TissueLyzer II (Qiagen). RNA was extracted using TRIzol®, treated with DNase I, and purified using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen). To measure ifnb1 and ifit1 expression, cDNA was prepared following instructions in the SuperScript II kit (Life Technologies). Real-time PCR reactions were carried out using an ABI 7500 Fast or ViiA™ 7 real-time PCR system with TaqMan universal master mix and the following primers: ifnb1 (Mm00439546_s1), ifit1 (Mm00515153_m1), and gapdh (4352932E) (Applied Biosystems®, Life Technologies). Relative expression (RE) was determined using the AB 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) and analysed by Comparative CT Method using the SDS v1.3.1 Relative Quantification Software.

Reovirus replication assay and quantitative PCR

For in vitro replication assays, 2 × 106 DCs or 3 × 105 MEFs were seeded into wells of 6-well plates (Corning, Corning, NY) and adsorbed in triplicate with reovirus T3D at an MOI of 0.1 PFU/cell for 1 h at room temperature in serum-free medium, washed once with PBS, and incubated in serum-containing medium for various intervals. Twenty-four or forty-eight hours post-infection RNA from each sample was purified as described above and quantified by RT-qPCR using a modification of a previously described protocol33. Following in vitro and in vivo assays, reovirus S4 vRNA was quantified using 1-4 μg of total RNA extract. Forward (S4 83F, 5′-CGCTTTTGAAGGTCGTGTATCA-3′) primer was used for reverse transcription before reverse (S4 153R, 5′-CTGGCTGTGCTGAGATTGTTTT-3′) primer was added for qPCR amplification. The S4-specific fluorogenic probe used was 5′-dFAM-AGCGCGCAAGAGGGATGGGA-BHQ-1-3′ (Biosearch Technologies, Petaluma, CA). After denaturing RNA for 3 min at 95°C, reverse transcription was performed for 15 min at 50 °C and terminated by incubation for 3 min at 95°C. Subsequently, 40 cycles of qPCR were performed (95°C for 15 sec; 60°C for 30 sec). Reovirus S4 copy numbers were calculated relative to a standard curve prepared using 10-fold dilutions of purified reovirus T3D vRNA as template RNA. The final S4 RNA copy number was normalized to the total sample RNA used per reaction. The S4 segment threshold cycle (Ct) value of each sample was also used to determine the relative expression of S4 to that of gapdh.

Reovirus strand specific reverse transcription and quantitative PCR

Strand-specific reverse transcription was carried out by mixing reoT3D vRNA with reverse primers ([+] strand-specific reverse transcription) or forward primers ([-] strand-specific reverse transcription), as indicated below, heating to 98°C and snap-cooling on ice before incubating for 5 min at 60°C. Reverse transcription was performed at 42°C for 30 min (Revert AID, Thermo Scientific). Subsequently, 40 cycles of qPCR were performed (95°C for 15 sec; 60°C for 20 sec; 72°C for 20 sec) using EvaGreen qPCR master mix (Biotium, Hayward, USA). Primers used were:

| 1A T3D L1 75-5′ | CACTGACCAATCGAATGACG |

| 1A′ T3D L1 262-3′ | GCACACGGTTTAGAGCATCA |

| 1B T3D L1 3525-5′ | TGTGCAATTAGCCAGAGTGG |

| 1B′ T3D L1 3718-3′ | TCGCAGTCATTACCATTCCA |

| 2A T3D L2 31-5′ | GGTGAGACTTGCAGACTCGTT |

| 2A′ T3D L2 130-3′ | CCCCGGATTAGCATCTAGG |

| 2B T3D L2 3780-5′ | TGCTACCTCAAGATTGGGATG |

| 2B′ T3D L2 3902-3′ | GCTCACGAGGGACAGTGAG |

| 3A T3D L3 31-5′ | GAAGACAAAGGGCAAATCCA |

| 3A′ T3D L3 130-3′ | GCCAGCCTTATTGTTTTGCTT |

| 3B T3D L3 3741-5′ | CGCAGATACAACTGCCTGAA |

| 3B′ T3D L3 3856-3′ | TTGGGAGGATGAGGATCAAG |

| 4A T3D M1 16-5′ | GGCTTACATCGCAGTTCCTG |

| 4A′ T3D M1 120-3′ | GAAACGTCATTCGCGTCAG |

| 4B T3D M1 2178-5′ | GAGCTGCATACAGTGCGAGA |

| 4B′ T3D M1 2298-3′ | GCGCGTACGTAGTCTTAGCC |

| 5A T3D M2 19-5′ | ACTCTGCAAAGATGGGGAAC |

| 5A′ T3D M2 120-3′ | CGATGGTACAGCGGTAGATG |

| 5B T3D M2 2089-5′ | AATCGTCTAATCGCCGAGTG |

| 5B′ T3D M2 2199-3′ | ATTTGCCTGCATCCCTTAAC |

| 6A T3D M3 20-5′ | TGGCTTCATTCAAGGGATTC |

| 6A′ T3D M3 138-3′ | ATCCACAGACGGAGTGAAGG |

| 6B T3D M3 2129-5′ | CAGCTGATGGTGTTGCTGAC |

| 6B′ T3D M3 2228-3′ | CGGGAAGGCTTAAGGGATTA |

| 7A T3D S1 18-5′ | TCCTCGCCTACGTGAAGAAG |

| 7A′ T3D S1 163-3′ | GGGTGATCCGGAGGATAGTA |

| 7B T3D S1 1268-5′ | AGCAGTGGCAGGATGGAGTA |

| 7B′ T3D S1 1374-3′ | GAAACTACGCGGGTACGAAA |

| 8A T3D S2 53-5′ | GGTTTGGTGGTCTGCAAAAT |

| 8A′ T3D S2 178-3′ | TAGCTAAACCCCTCCCAAGG |

| 8B T3D S2 1218-5′ | GCAATGGGGACGAGGTAATA |

| 8B′ T3D S2 1319-3′ | GTCAGTCGTGAGGGGTGTG |

| 9A T3D S3 19-5′ | GTCGTCACTATGGCTTCCTCA |

| 9A′ T3D S3 118-3′ | AGGACCGCAGCATGACATA |

| 9B T3D S3 1083-5′ | TGACGCCAGTGATGCTAGAC |

| 9B′ T3D S3 1186-3′ | TCACCCACCACCAAGACAC |

| 10A T3D S4 54-5′ | GGTCATCAGGTCGTGGACTT |

| 10A′ T3D S4 153-3′ | CTGGCTGTGCTGAGATTGTT |

| 10B T3D S4 1039-5′ | CTCCTGCTGCTCTCACAATG |

| 10B′ T3D S4 1148-3′ | CTGTGAAGATGGGGGTGTTT |

Mice and in vivo infection studies

All mice used in this study were bred in specific pathogen-free (SPF) conditions by the Cancer Research UK - Biological Resources Unit. Experiments were performed in accordance with national and institutional guidelines for animal care and approved by the Institutional Animal Ethics Committee Review Board, Cancer Research UK. Wild-type C57BL/6J mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). The C57BL/6 MAVS−/− (also known as Cardif−/−) mice were provided by Dr. Jürg Tschopp (deceased). RIG-I (Ddx58) B6;129X1(ICR)-Ddx58tm1Aki and MDA5 (Ifih1) B6;129X1-Ifih1tm1Aki mice were obtained from Dr. Shizuo Akira (Japan) and backcrossed once to C57BL/6J mice. For infection studies, 6-8-week-old male or female mice were inoculated perorally with 109 PFU of reovirus T3SA+ in 200 μl borate-buffered saline (0.13 M NaCl, 0.25 mM CaCl2, 1.5 mM MgCl2 × 6H20, 20 mM H3BO3, and 0.15 mM Na2B4O7 × 10H2O) containing 5 g/L of gelatine (Sigma-Aldrich). Forty-eight hours post-infection, mice were euthanized, and organs (intestine and MLNs) were harvested and processed. Investigator was blinded when processing and assessing outcome by giving a unique number to each animal, which was independent of genotype. No randomization to experimental groups was required for these studies and minimum sample size of n=5 per group was chosen.

RIG-I immunoprecipitation

For immunoprecipitation (IP) studies using stable FLAG-RIG-I clones, one 80% confluent 145 cm2 plate of HEK293 cells stably expressing FLAG-RIG-I was washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and infected with reoT1L at an MOI of 100 PFU/cell in FCS-free medium. Cells were incubated for 1 h at 37°C and 10% CO2 before adding an equivalent volume of medium supplemented to contain 20% FCS. Four hours later, cells were washed with ice-cold PBS and lysed in 4 ml of ice-cold buffer C (0.5% NP40, 20mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl; 2.5mM MgCl2; complete protease inhibitor [Roche Applied Sciences], 0.1 U/ml RNasin [Promega]). Lysates were incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 15 min to remove cell debris. Resulting supernatants were divided equally and incubated with α-FLAG M2 antibody (Sigma-Aldrich) or control mIgG1 (BD Biosciences, Franklin, NJ) for 1.5-2 h at 4°C on a rotating wheel before adding Gamma Bind Plus Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). Two hours later, beads were collected by centrifugation and washed five times for 2 min with 1-1.5 ml of buffer C. Bead samples were divided for RNA extraction with Ultra Pure™ phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol (25:24:1) (Life Technologies) or subjected to immunoblotting. RNA isolated from beads was resuspended in 20μl of RNase-free water and transfected into HEK293 cells expressing the IFN-β reporter. For IP using recombinant RIG-I, 1 μg of purified protein was incubated with different RNA in lysis buffer C for 2 h at 4°C on a rotating shaker. The rest of the IP was performed using the protocol employed for the RIG-I IP from infected cells.

Alpha Screen RIG-I-binding assay

The binding affinity of RNA for (His6)-FLAG-tagged wild-type RIG-I was determined as described18 using an amplified luminescent proximity homogenous assay (AlphaScreen; Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA). Purified (His6)-FLAG-RIG-I was incubated with increasing concentrations of biotinylated RNA (non-triphosphorylated antisense RNA is 5′biotinylated) for 1 hour at 37°C in buffer (50 mM Tris/pH7.4, 100 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween20, 0.1% BSA) and subsequently incubated for 30 min at 25°C with (His6)-FLAG-RIG-I-binding nickel-chelate acceptor beads (Perkin-Elmer) and biotin-RNA-binding streptavidin donor beads (Perkin Elmer).

Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis

Samples of GMP, GDP, and GTP were analysed by LC-MS using an Agilent 1100 LC-MSD. Analysis was carried out using a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C8 Rapid Resolution HT 3.0 × 50 mm 1.8 micron column. Buffer A is 1% acetonitrile and 0.08% trifluoroacetic acid in milliQ water, and Buffer B is 90% acetonitrile and 0.08% trifluoroacetic acid in milliQ water. Flow rate was 0.425 mls/min, and the gradient was 0% – 40% Buffer B over 8 min. The MS was conducted with positive polarity, fragmentor voltage was 170, drying gas flow 12 L/min, drying gas temperature 350°C, and nebuliser pressure 40 psig. Mass spectra were registered in full-scan mode (m/z 200 to 3000 step size 0.15). RNA samples were analysed by electrospray ionization (ESI) -LC-MS performed by Axolabs GmbH (Kulmbach, Germany) using a Dionex Ultimate3000 RS system coupled to a Bruker maXis Q-ToF mass spectrometer. The samples were analysed with an improved version of the protocol established for ribonucleotide digestion analysis34. Analysis of 4 pmol and 50 pmol of an equimolar solution of chemically synthesised pp-RNA24nts and ppp-RNA24nts treated with RNase T2 served as control. Characterisation of reovirus genome RNA was performed with 50 μl (13 μg) of the RNase T2 digest.

Poly(I:C) studies

Poly(I:C) was obtained from Amersham (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) and treated or not with the dsRNA-specific endoribonuclease, RNase III from Ambion (Life Technologies) as specified by the manufacturer. Digestion was performed at room temperature and halted at 1 min or 5 min following enzyme addition using 125 mM EDTA. Poly(I:C) samples were purified using Ultra Pure™ phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol (25:24:1) (Life Technologies) and precipitated using ethanol before being treated with CIP and re-purified as done following RNase III treatment. A fraction of the samples were electrophoresed in 0.8% agarose gels and visualized using ethidium bromide, whereas another fraction was transfected into SV40 large T antigen-immortalized MDA5−/− or RIG−/− MEFs. Cells (5 × 104) in aliquots of 0.5 ml antibiotic-free medium were placed into wells of 24-well plates and transfected one day later. For the IFN-βluciferase promoter reporter assay, cells were transfected with a mix of 0.3 μg of IFN-βluciferase promoter reporter (F-luc) and 0.05 μg of Renilla luciferase control (R-luc) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After 8 h, various concentrations of samples were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000. Luciferase activity was quantified 24 h later using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay System from Promega. Firefly luciferase activity was normalized to Renilla luciferase, and fold inductions were calculated relative to a control transfection using water only (F-luc/R-luc). For RT-qPCR analysis of ifit1 levels, cells were transfected with various concentrations of samples using Lipofectamine 2000. Samples were harvested 16 h later, and RNA was extracted as described above.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired, two-tailed, Student’s t-tests or two-way ANOVAs. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Supplementary Material

(a) Total RNA purified from reoT1L particles (vRNA) was treated or not with calf intestinal phosphatase (+/− CIP). RNA integrity was verified by gel electrophoresis (left panel) or transfected into HEK293 cells to determine its capacity to stimulate the IFN-β promoter using a reporter assay (right panel). (b) L, M, and S reoT1L genome segments were isolated by gel fractionation and treated or not with CIP. An aliquot of the treated samples was electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel to validate RNA integrity (left panel), whereas another was transfected into HEK293 cells to determine its capacity to stimulate the IFN-β promoter using a reporter assay (right panel). (c-d) Total L-A RNA as well as gel-purified L-A genomes and transcripts (as in Fig. 1i) were transfected into RIG-I+/− or RIG-I−/− MEFs (c) and MDA5+/+ or MDA5−/− DCs (d). After incubation for 16 h, the relative expression (RE) of ifit1 over gapdh (c) or murine IFN-α levels (d) were determined. Water and ppp-IVT-RNA99nts, poly(dA:dT), or RNA isolated from Vero cells infected with encephalomyocarditis virus (Vero-EMCV-RNA) were included as controls (* = none detected). All experiments were performed at least twice; one representative experiment is shown.

This experiment was conducted exactly as in Fig. 2a but using strain reoT3D.

(a) Representative LC-MS spectra of GMP, GDP, and GTP sources used for the preparation of IVT-RNAs in Fig. 3. Asterisks indicate the expected mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of the different guanosines. (b) IVT-RNA25nts were generated as depicted in Fig. 3a using GMP, GTP, or GMP spiked with GTP (GMP + 10% GTP) before being annealed to AS RNA and tested using the IFN-β promoter reporter assay following transfection into HEK293 cells. (c) Spectra of 5′pp-RNA24nts and 5′ppp-RNA24nts following MALDI ToF characterization (a.i., absolute intensity). Ions with two charges (m2+) appear exactly at half the expected (m+) mass/charge (m/z) ratio.

(a) Schematic representation of inosinic acid or cytidylic acid homopolymer synthesis from inosine 5′-diphosphate or cytidine 5′-diphosphate through the action of polynucleotide phosphorylase, which when annealed form the synthetic dsRNA analogue poly(I:C). Whether the synthesised polynucleotides carry a 5′ di- or mono-phosphate or a mixture of both is unclear. (b) IFN-pre-treated MDA5−/− or RIG-I−/− immortalized MEFs were transfected with poly(I:C) +/− CIP. IFN induction was quantified 16 h later using an IFN-β promoter reporter assay. (c) Poly(I:C) was first cleaved with RNase III for 1 or 5 min before being treated or not with CIP (+/−). Samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis to verify digestion (left panel) or transfected into IFN-pre-treated MDA5−/− MEFs (right panel). Cells were harvested 16 h post-transfection, and IFN-responses were assessed by RT-qPCR for ifit1 expression. Water and ppp-IVT-RNA99nts were included as controls. RE, relative expression. All experiments were performed at least twice; one representative experiment is shown. For PCR data, the mean (±s.d.) of triplicate technical replicates is shown.

(a-d) ESI-LC-MS analysis of RNase T2 treated synthetic 5′-ppRNA24nts and 5′-pppRNA24nts (a) and reovirus RNA (b-d). (a) ESI-LC-MS chromatogram of an RNase T2-treated equimolar solution of 5′-ppRNA24nts and 5′-pppRNA24nts (2 pmol/16 ng each). The assigned digestion products were confirmed by ESI-MS. (b) ESI-LC-MS profile of the RNase T2 digestion products of 13 μg (0.8 pmol) reoT1L genomic RNA. (c,d) Deconvoluted ESI-MS spectra of the 5′-terminal fragments 5′-ppGp (c, RT 16.11 min, calculated [M-H]: 523.0, found [M-H]: 522.1, 544.0 [+Na], 566.0 [+2Na], 588.0 [+3Na]) and 5′-pppGp (d, RT 16.6 min, calculated [M-H]: 603.0, found [M-H]: 602.0). (e) ppp-, pp- or OH-RNA24nts were treated (+) or not (-) with Terminator N before being electrophoresed. (f) ppp-IVT-RNA933nts (sense and anti-sense strands) were generated by in vitro transcription. Upper gel: Single-stranded ppp-IVT-RNA933nts was subjected (+) or not (-) to vaccinia virus encoded RNA 5′-triphosphorylase, cleaving the γ-phosphate and resulting in the generation of pp-IVT-RNA933nts and treated (+) or not (-) with Terminator N. Lower gel: ppp-dsRNA derived from annealing of ppp-IVT-RNA933nts and its complementary anti-sense were first denatured by melting and fast cooling before adding the indicated enzyme combinations. The resulting electrophoresed samples are shown. (g) Expected outcome of the denaturation and digestion with Terminator N ± 5′-triphosphohydrolase of the reported and one of the possible scenarios of 5′ terminal structures present on reovirus genome segments. (h) Results of 5′ terminus strand-specific qPCR for all 10 reovirus segments (L1-L3, M1-M3, S1-S4) following treatment of reoT3D vRNA with Terminator N ± 5′-triphosphohydrolase as depicted in (g). Location of the primers used is indicated on top diagram. Data (±s.d.) normalized to the mean relative expression obtained for two untreated controls (set to 1). (i) Indicated amounts of reoT1L vRNA treated (+) or not (-) with RNA 5′-polyphosphatase were analysed by IFN-β promoter reporter assay in HEK293 cells.

Extended Text for Supplementary Figure 1

To confirm the presence of 5′pp on the negative strand of reovirus genome segments we used two different approaches. First, we analysed the phosphorylation status of the 5′-terminal nucleotide of reovirus genomic RNA by enzymatic digestion coupled to ESI-LC-MS analysis. We used the base-unspecific endonuclease RNase T2 to completely digest the RNA yielding 3′-monophosphate single nucleotides. The digestion products were resolved by ESI-LC-MS allowing separation of the phosphate-bearing 5′-terminal nucleotide from the internal 5′-hydroxyl nucleotides and simultaneous characterisation of the fragments by mass spectrometry. This requires high sensitivity analysis given the obvious scarcity of 5′-terminal nucleotides relative to internal ones (1 to ~ 2,350). As such, we first validated the approach using chemically-synthesised 5′-ppRNA24nts and 5′-pppRNA24nts. The RNA24nts oligonucleotide comprises a 5′-terminal guanosine residue, like reovirus genomic RNA. Simultaneous analysis of the 5′-diphosphate and 5′-triphosphate digestion products showed that the 5′-terminal fragments 5′-ppGp and 5′-pppGp elute at a time prior to and well separated from the 3′-monophoshate adenosine peak (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Comparable peak intensities for both species confirmed that the 5′-terminal di- and tri-phosphate moieties are preserved during analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1a). These data indicate that mass spectrometry can be used for the identification of 5′-ppGp and 5′-pppGp at amounts as low as 2 pmol (equivalent to 16 ng of RNA24nts).

Next, we digested comparable molar amounts (13 μg, equivalent to 8 pmol) of reovirus genomic RNA segments and analysed the digest by ESI-LC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 1b-d). As expected by the length of reovirus genome segments (2350 bp on average) compared to the 24 nucleotide standards used for validation, the reovirus RNA digest contained a much larger excess of 3′-monophosphate nucleotides, which resulted in peak broadening and slightly increased retention times (RT) during chromatographic separation (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Nevertheless, the UV-profile revealed a defined peak at retention time (RT) 16.1 minutes and a minor peak at RT 16.6 minutes, which could be assigned to 5′-ppGp (Supplementary Fig. 1c) and 5′-pppGp (Supplementary Fig. 1d), respectively, based on the ESI-MS spectra. Both relative UV-absorbance and ESI-MS signal intensity showed 5′-ppGp as the predominant species. 5′-pppGp was only detected in trace amounts, which may be attributable to a small degree of contamination by short single-stranded 5′ppp oligoribonucleotides that are also present within the virus particle35. Indeed, to isolate reovirus genomic RNA in the amounts required for mass spectrometry analysis, we had to resort to differential LiCl precipitation rather than gel separation (see Methods), which may not have fully eliminated the content of short oligonucleotides. Due to the much shorter length of the latter compared to that of reovirus genome segments (~ 2-20 bases per 5′ppp versus an expected ~ 4,700 bases per 5′pp), the presence of as little as ~ 0.04-0.4% contamination would be predicted to release into the digestion product amounts of pppGp comparable to the ppGp released by the genome segments. It is worth reiterating that our data indicate that these short ssRNA oligonucleotides do not trigger RIG-I activation (Fig. 1c), consistent with the idea that, in addition to possessing a 5′ppp, RIG-I agonists require a minimum length of 19bp as well as base-pairing at the 5′-end. In sum, the mass spectrometry data are consistent with the textbook depiction of reovirus genomes bearing a 5′-ppGp and not a 5′-pppGp on the negative strand. Of note, the analysis focused on the characterisation of 5′-ppGp and 5′-pppGp termini. The presence of a capped 5′-terminus on the positive strand, leading to release of m7G-ppp-GmCp-fragments by RNase T2 digestion, was not sampled in our analysis.

To further confirm the presence of 5′-ppGp and absence of 5′-pppGp on the reovirus genome, we used a second approach involving the selective digestion of 5′-diphosphate but not 5′-triphosphate RNA (Supplementary Fig. 1e-h). This method uses Terminator Nuclease (Terminator N), a 5′-phosphate-dependent exonuclease previously thought to exclusively digest 5′p-RNA and leave intact RNAs with a 5′ppp, a 5′OH or a 5′cap structure. We serendipitously found that Terminator N also digests RNAs bearing a 5′-diphosphate. Indeed, synthetic p- or pp-RNA24nts but not OH- or ppp-RNA24nts are digested following Terminator N treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Furthermore, a single-stranded triphosphorylated RNA prepared by in vitro transcription (ppp-IVT-RNA933nts) became sensitive to Terminator N digestion when treated with vaccinia virus-encoded 5′-triphosphohydrolase (part of the capping enzyme) to selectively cleave the γ-phosphate (Supplementary Fig. 1f, top panel). As Terminator N is specific for ssRNA, we added a melting and fast cooling step to denature dsRNA (e.g., double-stranded ppp-IVT-RNA933nts) and render it similarly sensitive to Terminator N after γ-phosphate trimming with vaccinia virus 5′ triphosphohydrolase (Supplementary Fig. 1f, bottom panel). Having established a protocol to selectively digest 5′pp but not 5′ppp dsRNA, we used Terminator N to assess the presence of 5′pp and the absence of 5′ppp on the termini of reovirus genome segments (Supplementary Fig. 1g). When reovirus genomic RNA was denatured and treated with Terminator N, the 5′pp containing [-] strand but not the 5′-capped [+] strand of all 10 reovirus segments became selectively digested as assessed using strand-specific qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Analogous results where obtained when reovirus genomic RNA was treated with Terminator N and 5′-triphosphohydrolase (Supplementary Fig. 1h). The latter control eliminates the possibility that a fraction of the [+] strand RNA contains a 5′ppp rather than a cap as this would have resulted in digestion and consequent decrease in the PCR signal for the [+] strand (Supplementary Fig. 1g). In sum, the disappearance after Terminator N treatment of the PCR signal for each of the [-] strands of reovirus genomic RNA segments together with the resistance of the corresponding [+] strands to the same treatment after 5′-triphosphohydrolase digestion allows us to conclude that there is no 5′ppp on the reovirus genome. We cannot ascertain, given the specificity of Terminator N, whether a 5′ monophosphate might be present on a fraction of the negative strands of reovirus genome segments. Yet, pGp was not detected by continuous MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1b and data not shown) and, in any case, 5′p RNAs are not expected to activate RIG-I (Fig. 3 and references 18,19). Consistent with that notion, treatment of reovirus genomic RNA segments with RNA 5′-polyphosphatase (which removes 5′pp and 5′ppp RNA leaving a 5′p) resulted in a complete loss of stimulatory potential (Supplementary Fig. 1i).

In conclusion, our results confirm the absence of 5′ppp and the presence of an unblocked diphosphate36,37 at the 5′ terminus of the [-] strand of all 10 reovirus genome segments. Lastly, although our data demonstrate that 5′-diphosphates present on reovirus genome segments can activate RIG-I (Fig.1f,g), we cannot completely exclude the possibility that during the course of an infection other viral RNA species such as polymerase by-products with uncapped 5′ppp ends may also be generated. However, those products are dispensable for RLR activation, as previous reports have demonstrated that treatment of cells with ribavirin, which blocks reovirus transcription, has no effect on activation of the IFN pathway4.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Dr. Shizuo Akira and Dr. Jürg Tschopp (deceased) for generous gifts of mice and cells, as well as Nicola O’Reilly, the LRI Equipment Park (David Phillips), and the LRI Protein Analysis and Proteomics Facility (Roger George and Svend Kjaer) for technical assistance. We also thank Pierre Maillard and Kathryn Snelgrove for reading the manuscript, Paolo Tortora, Gianni Dehò and Miguel Freire for their insights on the synthesis of poly(I:C) and all members of the CRUK Immunobiology Laboratory for helpful discussions and comments. C.R.S., D.G., S.D. and A.G.V.V. are funded by Cancer Research UK, a prize from Fondation Bettencourt-Schueller, and a grant from the European Research Council (ERC Advanced Researcher Grant AdG-2010-268670). A.J.P and T.S.D. are supported by Public Health Service awards R01 AI038296 and R01 AI050800 and the Elizabeth B. Lamb Center for Pediatric Research. T.S. is supported by the Fundación Ramón Areces. G.H. and M.S. and W.B. are supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (www.dfg.de; SFB670 to MS and WB and GH, DFG SCHL1930/1-1 to MS, SFB704 to GH and WB, SFB832 and KFO177 to GH). GH and MS are supported by the DFG Excellence Cluster ImmunoSensation. GH is supported by the German Center of Infectious Disease (DZIF).

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Goubau D, Deddouche S, Reis e Sousa C. Cytosolic sensing of viruses. Immunity. 2013;38:855–869. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schlee M. Master sensors of pathogenic RNA – RIG-I like receptors. Immunobiology. 2013;218:1322–1335. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rehwinkel J, Reis e Sousa C. Targeting the viral Achilles’ heel: recognition of 5′-triphosphate RNA in innate anti-viral defence. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2013;16:485–492. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holm GH, et al. Retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and interferon-beta promoter stimulator-1 augment proapoptotic responses following mammalian reovirus infection via interferon regulatory factor-3. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:21953–21961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702112200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kato H, et al. Length-dependent recognition of double-stranded ribonucleic acids by retinoic acid-inducible gene-I and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1601–1610. doi: 10.1084/jem.20080091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loo Y-M, et al. Distinct RIG-I and MDA5 signaling by RNA viruses in innate immunity. J Virol. 2008;82:335–345. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01080-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pichlmair A, et al. Activation of MDA5 requires higher-order RNA structures generated during virus infection. J Virol. 2009;83:10761–10769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00770-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lu C, et al. The Structural Basis of 5′ Triphosphate Double-Stranded RNA Recognition by RIG-I C-Terminal Domain. Structure. 2010;18:1032–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Luo D, et al. Structural insights into RNA recognition by RIG-I. Cell. 2011;147:409–422. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang F, et al. Structural basis of RNA recognition and activation by innate immune receptor RIG-I. Nature. 2011;479:423–427. doi: 10.1038/nature10537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang Y, et al. Structural and functional insights into 5′-ppp RNA pattern recognition by the innate immune receptor RIG-I. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:781–787. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dermody TS, Sherry B, Parker JSL, Knipe DM, Howley PM. Fields Virology. Vol. 2. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rehwinkel J, et al. RIG-I Detects Viral Genomic RNA during Negative-Strand RNA Virus Infection. Cell. 2010;140:397–408. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baum A, Sachidanandam R, García-Sastre A. Preference of RIG-I for short viral RNA molecules in infected cells revealed by next-generation sequencing. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:16303–16308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005077107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujimura T, Esteban R. Yeast double-stranded RNA virus L-A deliberately synthesizes RNA transcripts with 5′-diphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:22911–22918. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.138982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujimura T, Esteban R. Cap-snatching mechanism in yeast L-A double-stranded RNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:17667–17671. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111900108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hornung V, et al. 5′-Triphosphate RNA Is the Ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006;314:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schlee M, et al. Recognition of 5′ Triphosphate by RIG-I Helicase Requires Short Blunt Double-Stranded RNA as Contained in Panhandle of Negative-Strand Virus. Immunity. 2009;31:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmidt A, et al. 5′-triphosphate RNA requires base-paired structures to activate antiviral signaling via RIG-I. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12067–12072. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900971106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldeck M, Tuschl T, Hartmann G, Ludwig J. Efficient Solid-Phase Synthesis of pppRNA by Using Product-Specific Labeling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2014;53:4694–4698. doi: 10.1002/anie.201400672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vela A, Fedorova O, Ding SC, Pyle AM. The thermodynamic basis for viral RNA detection by the RIG-I innate immune sensor. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:42564–42573. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.385146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohlway A, Luo D, Rawling DC, Ding SC, Pyle AM. Defining the functional determinants for RNA surveillance by RIG-I. EMBO Rep. 2013;14:772–779. doi: 10.1038/embor.2013.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grunberg-Manago M, Oritz PJ, Ochoa S. Enzymatic synthesis of nucleic acidlike polynucleotides. Science. 1955;122:907–910. doi: 10.1126/science.122.3176.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Decroly E, Ferron F, Lescar J, Canard B. Conventional and unconventional mechanisms for capping viral mRNA. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2011;10:51–65. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gerlier D, Lyles DS. Interplay between innate immunity and negative-strand RNA viruses: towards a rational model. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2011;75:468–490. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00007-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Inaba K, et al. Generation of large numbers of dendritic cells from mouse bone marrow cultures supplemented with granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1693–1702. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi T, Ooms LS, Ikizler M, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. An improved reverse genetics system for mammalian orthoreoviruses. Virology. 2010;398:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.11.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barton ES, Connolly JL, Forrest JC, Chappell JD, Dermody TS. Utilization of sialic acid as a coreceptor enhances reovirus attachment by multistep adhesion strengthening. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:2200–2211. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M004680200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Virgin HW, Bassel-Duby R, Fields BN, Tyler KL. Antibody protects against lethal infection with the neurally spreading reovirus type 3 (Dearing) J Virol. 1988;62:4594–4604. doi: 10.1128/jvi.62.12.4594-4604.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Diaz-Ruiz JR, Kaper JM. Isolation of viral double-stranded RNAs using a LiCl fractionation procedure. Prep. Biochem. 1978;8:1–17. doi: 10.1080/00327487808068215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Diebold SS, et al. Viral infection switches non-plasmacytoid dendritic cells into high interferon producers. Nature. 2003;424:324–328. doi: 10.1038/nature01783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Boehme KW, Frierson JM, Konopka JL, Kobayashi T, Dermody TS. The reovirus sigma1s protein is a determinant of hematogenous but not neural virus dissemination in mice. J Virol. 2011;85:11781–11790. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02289-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ablasser A, et al. cGAS produces a 2′-5′-linked cyclic dinucleotide second messenger that activates STING. Nature. 2013;498:380–384. doi: 10.1038/nature12306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellamy AR, Hole LV, Baguley BC. Isolation of the trinucleotide pppGpCpU from reovirus. Virology. 1970;42:415–420. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(70)90284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chow N-L, Shatkin AJ. Blocked and Unblocked 5′ Termini in Reovirus Genome RNA. J Virol. 1975;15:1057–1064. doi: 10.1128/jvi.15.5.1057-1064.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Banerjee AK, Shatkin AJ. Guanosine-5′-diphosphate at the 5′ termini of reovirus RNA: evidence for a segmented genome within the virion. J Mol Biol. 1971;61:643–653. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(71)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(a) Total RNA purified from reoT1L particles (vRNA) was treated or not with calf intestinal phosphatase (+/− CIP). RNA integrity was verified by gel electrophoresis (left panel) or transfected into HEK293 cells to determine its capacity to stimulate the IFN-β promoter using a reporter assay (right panel). (b) L, M, and S reoT1L genome segments were isolated by gel fractionation and treated or not with CIP. An aliquot of the treated samples was electrophoresed in a 0.8% agarose gel to validate RNA integrity (left panel), whereas another was transfected into HEK293 cells to determine its capacity to stimulate the IFN-β promoter using a reporter assay (right panel). (c-d) Total L-A RNA as well as gel-purified L-A genomes and transcripts (as in Fig. 1i) were transfected into RIG-I+/− or RIG-I−/− MEFs (c) and MDA5+/+ or MDA5−/− DCs (d). After incubation for 16 h, the relative expression (RE) of ifit1 over gapdh (c) or murine IFN-α levels (d) were determined. Water and ppp-IVT-RNA99nts, poly(dA:dT), or RNA isolated from Vero cells infected with encephalomyocarditis virus (Vero-EMCV-RNA) were included as controls (* = none detected). All experiments were performed at least twice; one representative experiment is shown.

This experiment was conducted exactly as in Fig. 2a but using strain reoT3D.

(a) Representative LC-MS spectra of GMP, GDP, and GTP sources used for the preparation of IVT-RNAs in Fig. 3. Asterisks indicate the expected mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of the different guanosines. (b) IVT-RNA25nts were generated as depicted in Fig. 3a using GMP, GTP, or GMP spiked with GTP (GMP + 10% GTP) before being annealed to AS RNA and tested using the IFN-β promoter reporter assay following transfection into HEK293 cells. (c) Spectra of 5′pp-RNA24nts and 5′ppp-RNA24nts following MALDI ToF characterization (a.i., absolute intensity). Ions with two charges (m2+) appear exactly at half the expected (m+) mass/charge (m/z) ratio.

(a) Schematic representation of inosinic acid or cytidylic acid homopolymer synthesis from inosine 5′-diphosphate or cytidine 5′-diphosphate through the action of polynucleotide phosphorylase, which when annealed form the synthetic dsRNA analogue poly(I:C). Whether the synthesised polynucleotides carry a 5′ di- or mono-phosphate or a mixture of both is unclear. (b) IFN-pre-treated MDA5−/− or RIG-I−/− immortalized MEFs were transfected with poly(I:C) +/− CIP. IFN induction was quantified 16 h later using an IFN-β promoter reporter assay. (c) Poly(I:C) was first cleaved with RNase III for 1 or 5 min before being treated or not with CIP (+/−). Samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis to verify digestion (left panel) or transfected into IFN-pre-treated MDA5−/− MEFs (right panel). Cells were harvested 16 h post-transfection, and IFN-responses were assessed by RT-qPCR for ifit1 expression. Water and ppp-IVT-RNA99nts were included as controls. RE, relative expression. All experiments were performed at least twice; one representative experiment is shown. For PCR data, the mean (±s.d.) of triplicate technical replicates is shown.

(a-d) ESI-LC-MS analysis of RNase T2 treated synthetic 5′-ppRNA24nts and 5′-pppRNA24nts (a) and reovirus RNA (b-d). (a) ESI-LC-MS chromatogram of an RNase T2-treated equimolar solution of 5′-ppRNA24nts and 5′-pppRNA24nts (2 pmol/16 ng each). The assigned digestion products were confirmed by ESI-MS. (b) ESI-LC-MS profile of the RNase T2 digestion products of 13 μg (0.8 pmol) reoT1L genomic RNA. (c,d) Deconvoluted ESI-MS spectra of the 5′-terminal fragments 5′-ppGp (c, RT 16.11 min, calculated [M-H]: 523.0, found [M-H]: 522.1, 544.0 [+Na], 566.0 [+2Na], 588.0 [+3Na]) and 5′-pppGp (d, RT 16.6 min, calculated [M-H]: 603.0, found [M-H]: 602.0). (e) ppp-, pp- or OH-RNA24nts were treated (+) or not (-) with Terminator N before being electrophoresed. (f) ppp-IVT-RNA933nts (sense and anti-sense strands) were generated by in vitro transcription. Upper gel: Single-stranded ppp-IVT-RNA933nts was subjected (+) or not (-) to vaccinia virus encoded RNA 5′-triphosphorylase, cleaving the γ-phosphate and resulting in the generation of pp-IVT-RNA933nts and treated (+) or not (-) with Terminator N. Lower gel: ppp-dsRNA derived from annealing of ppp-IVT-RNA933nts and its complementary anti-sense were first denatured by melting and fast cooling before adding the indicated enzyme combinations. The resulting electrophoresed samples are shown. (g) Expected outcome of the denaturation and digestion with Terminator N ± 5′-triphosphohydrolase of the reported and one of the possible scenarios of 5′ terminal structures present on reovirus genome segments. (h) Results of 5′ terminus strand-specific qPCR for all 10 reovirus segments (L1-L3, M1-M3, S1-S4) following treatment of reoT3D vRNA with Terminator N ± 5′-triphosphohydrolase as depicted in (g). Location of the primers used is indicated on top diagram. Data (±s.d.) normalized to the mean relative expression obtained for two untreated controls (set to 1). (i) Indicated amounts of reoT1L vRNA treated (+) or not (-) with RNA 5′-polyphosphatase were analysed by IFN-β promoter reporter assay in HEK293 cells.

Extended Text for Supplementary Figure 1

To confirm the presence of 5′pp on the negative strand of reovirus genome segments we used two different approaches. First, we analysed the phosphorylation status of the 5′-terminal nucleotide of reovirus genomic RNA by enzymatic digestion coupled to ESI-LC-MS analysis. We used the base-unspecific endonuclease RNase T2 to completely digest the RNA yielding 3′-monophosphate single nucleotides. The digestion products were resolved by ESI-LC-MS allowing separation of the phosphate-bearing 5′-terminal nucleotide from the internal 5′-hydroxyl nucleotides and simultaneous characterisation of the fragments by mass spectrometry. This requires high sensitivity analysis given the obvious scarcity of 5′-terminal nucleotides relative to internal ones (1 to ~ 2,350). As such, we first validated the approach using chemically-synthesised 5′-ppRNA24nts and 5′-pppRNA24nts. The RNA24nts oligonucleotide comprises a 5′-terminal guanosine residue, like reovirus genomic RNA. Simultaneous analysis of the 5′-diphosphate and 5′-triphosphate digestion products showed that the 5′-terminal fragments 5′-ppGp and 5′-pppGp elute at a time prior to and well separated from the 3′-monophoshate adenosine peak (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Comparable peak intensities for both species confirmed that the 5′-terminal di- and tri-phosphate moieties are preserved during analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1a). These data indicate that mass spectrometry can be used for the identification of 5′-ppGp and 5′-pppGp at amounts as low as 2 pmol (equivalent to 16 ng of RNA24nts).

Next, we digested comparable molar amounts (13 μg, equivalent to 8 pmol) of reovirus genomic RNA segments and analysed the digest by ESI-LC-MS (Supplementary Fig. 1b-d). As expected by the length of reovirus genome segments (2350 bp on average) compared to the 24 nucleotide standards used for validation, the reovirus RNA digest contained a much larger excess of 3′-monophosphate nucleotides, which resulted in peak broadening and slightly increased retention times (RT) during chromatographic separation (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Nevertheless, the UV-profile revealed a defined peak at retention time (RT) 16.1 minutes and a minor peak at RT 16.6 minutes, which could be assigned to 5′-ppGp (Supplementary Fig. 1c) and 5′-pppGp (Supplementary Fig. 1d), respectively, based on the ESI-MS spectra. Both relative UV-absorbance and ESI-MS signal intensity showed 5′-ppGp as the predominant species. 5′-pppGp was only detected in trace amounts, which may be attributable to a small degree of contamination by short single-stranded 5′ppp oligoribonucleotides that are also present within the virus particle35. Indeed, to isolate reovirus genomic RNA in the amounts required for mass spectrometry analysis, we had to resort to differential LiCl precipitation rather than gel separation (see Methods), which may not have fully eliminated the content of short oligonucleotides. Due to the much shorter length of the latter compared to that of reovirus genome segments (~ 2-20 bases per 5′ppp versus an expected ~ 4,700 bases per 5′pp), the presence of as little as ~ 0.04-0.4% contamination would be predicted to release into the digestion product amounts of pppGp comparable to the ppGp released by the genome segments. It is worth reiterating that our data indicate that these short ssRNA oligonucleotides do not trigger RIG-I activation (Fig. 1c), consistent with the idea that, in addition to possessing a 5′ppp, RIG-I agonists require a minimum length of 19bp as well as base-pairing at the 5′-end. In sum, the mass spectrometry data are consistent with the textbook depiction of reovirus genomes bearing a 5′-ppGp and not a 5′-pppGp on the negative strand. Of note, the analysis focused on the characterisation of 5′-ppGp and 5′-pppGp termini. The presence of a capped 5′-terminus on the positive strand, leading to release of m7G-ppp-GmCp-fragments by RNase T2 digestion, was not sampled in our analysis.

To further confirm the presence of 5′-ppGp and absence of 5′-pppGp on the reovirus genome, we used a second approach involving the selective digestion of 5′-diphosphate but not 5′-triphosphate RNA (Supplementary Fig. 1e-h). This method uses Terminator Nuclease (Terminator N), a 5′-phosphate-dependent exonuclease previously thought to exclusively digest 5′p-RNA and leave intact RNAs with a 5′ppp, a 5′OH or a 5′cap structure. We serendipitously found that Terminator N also digests RNAs bearing a 5′-diphosphate. Indeed, synthetic p- or pp-RNA24nts but not OH- or ppp-RNA24nts are digested following Terminator N treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1e). Furthermore, a single-stranded triphosphorylated RNA prepared by in vitro transcription (ppp-IVT-RNA933nts) became sensitive to Terminator N digestion when treated with vaccinia virus-encoded 5′-triphosphohydrolase (part of the capping enzyme) to selectively cleave the γ-phosphate (Supplementary Fig. 1f, top panel). As Terminator N is specific for ssRNA, we added a melting and fast cooling step to denature dsRNA (e.g., double-stranded ppp-IVT-RNA933nts) and render it similarly sensitive to Terminator N after γ-phosphate trimming with vaccinia virus 5′ triphosphohydrolase (Supplementary Fig. 1f, bottom panel). Having established a protocol to selectively digest 5′pp but not 5′ppp dsRNA, we used Terminator N to assess the presence of 5′pp and the absence of 5′ppp on the termini of reovirus genome segments (Supplementary Fig. 1g). When reovirus genomic RNA was denatured and treated with Terminator N, the 5′pp containing [-] strand but not the 5′-capped [+] strand of all 10 reovirus segments became selectively digested as assessed using strand-specific qPCR (Supplementary Fig. 1h). Analogous results where obtained when reovirus genomic RNA was treated with Terminator N and 5′-triphosphohydrolase (Supplementary Fig. 1h). The latter control eliminates the possibility that a fraction of the [+] strand RNA contains a 5′ppp rather than a cap as this would have resulted in digestion and consequent decrease in the PCR signal for the [+] strand (Supplementary Fig. 1g). In sum, the disappearance after Terminator N treatment of the PCR signal for each of the [-] strands of reovirus genomic RNA segments together with the resistance of the corresponding [+] strands to the same treatment after 5′-triphosphohydrolase digestion allows us to conclude that there is no 5′ppp on the reovirus genome. We cannot ascertain, given the specificity of Terminator N, whether a 5′ monophosphate might be present on a fraction of the negative strands of reovirus genome segments. Yet, pGp was not detected by continuous MS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 1b and data not shown) and, in any case, 5′p RNAs are not expected to activate RIG-I (Fig. 3 and references 18,19). Consistent with that notion, treatment of reovirus genomic RNA segments with RNA 5′-polyphosphatase (which removes 5′pp and 5′ppp RNA leaving a 5′p) resulted in a complete loss of stimulatory potential (Supplementary Fig. 1i).

In conclusion, our results confirm the absence of 5′ppp and the presence of an unblocked diphosphate36,37 at the 5′ terminus of the [-] strand of all 10 reovirus genome segments. Lastly, although our data demonstrate that 5′-diphosphates present on reovirus genome segments can activate RIG-I (Fig.1f,g), we cannot completely exclude the possibility that during the course of an infection other viral RNA species such as polymerase by-products with uncapped 5′ppp ends may also be generated. However, those products are dispensable for RLR activation, as previous reports have demonstrated that treatment of cells with ribavirin, which blocks reovirus transcription, has no effect on activation of the IFN pathway4.