SUMMARY

Chromatin organization and dynamics are integral to global gene transcription. Histone modification influences chromatin status and gene expression. PTEN plays multiple roles in tumor suppression, development and metabolism. Here we report on the interplay of PTEN, histone H1 and chromatin. We show that loss of PTEN leads to dissociation of histone H1 from chromatin and decondensation of chromatin. PTEN deletion also results in elevation of histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16, an epigenetic marker for chromatin activation. We found that PTEN and histone H1 physically interact through their C-terminal domains. Disruption of the PTEN C-terminus promotes the chromatin association of MOF acetyltransferase and induces H4K16 acetylation. Hyperacetylation of H4K16 impairs the association of PTEN with histone H1, which constitutes regulatory feedback that may deteriorate chromatin stability. Our results demonstrate that PTEN controls chromatin condensation, thus influencing gene expression. We propose that PTEN regulates global gene transcription profiling through histones and chromatin remodeling.

INTRODUCTION

Understanding of PTEN function has undergone explosive growth in the last decade, commensurate with its broad spectrum of activity and importance of this molecule to the cell. The extent and complexity of our knowledge regarding PTEN continues to increase and it is likely that there are more PTEN functions awaiting characterization. PTEN suppresses tumorigenesis by multiple mechanisms and is therefore recognized as a powerful tumor suppressor (Freeman et al., 2003; Li et al., 1997; Maehama and Dixon, 1998; Myers et al., 1998). PTEN is also essential for development as homologous deletion causes embryonic lethality in mice (Di Cristofano et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 1998). One of the canonical functions of PTEN is regulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway via lipid phosphatase activity (Cantley and Neel, 1999; Maehama and Dixon, 1998; Myers et al., 1998). PTEN also possesses phosphatase-independent functions in the nucleus, which are often mediated through protein-protein interactions (Baker, 2007; Li et al., 2006a; Shen et al., 2007; Song et al., 2011). Chromatin organization plays a critical role in gene regulation, and PTEN is known to have significant regulatory function in the nucleus. However, there have been limited studies to date that have examined PTEN as a potential modulator of chromatin structure and histone modification.

Accumulating evidence suggests that PTEN status influences gene expression. Microarray studies have revealed global changes in gene transcription profiles following PTEN depletion (Carver et al., 2011; Li et al., 2006b; Mulholland et al., 2012; Vivanco et al., 2007) or overexpression (Hong et al., 2000; Matsushima-Nishiu et al., 2001). However, the mechanism by which PTEN regulates gene transcription and expression profiles remains elusive. Transcriptional activation is associated with opening of the chromatin structure, including the higher-order chromatin structure (Berger, 2007). Therefore, it is possible that PTEN may play a role in chromatin remodeling and gene regulation.

Chromatin, together with its associated linker histones, is a highly condensed structure that allows compaction of the genome into the nucleus of the cell (Gilbert et al., 2004). This condensation also serves to suppress physiological activities dependent on access to DNA strands, such as transcription (Narlikar et al., 2002). Histone H1 is one of the key structural components of chromatin and is involved in the organization and stabilization of higher-order condensed chromatin structure (Bednar et al., 1998). Histone H1 binds to nucleosomes and shows a dynamic binding affinity for chromatin (Misteli et al., 2000), which allows modulation of chromatin architecture and the transcriptional regulation of target genes. Based on studies in Drosophila, Tetrahymena and other model organisms, histone H1 is generally a transcriptional repressor (Ura et al., 1997). Recent work in mouse embryonic stem cells showed that histone H1 can promote gene silencing by regulating DNA methylation and histone H3 methylation (Yang et al., 2013). Histone H1 is necessary for repression of pluripotency genes and its depletion impairs embryonic stem cell differentiation (Zhang et al., 2012). A more detailed study of this mechanism demonstrated that sequence-specific or basal transcription factors are required to displace H1 during transcriptional activation (Vicent et al., 2011).

Compacted chromatin is highly dynamic and may also undergo regional alterations in condensation. Chromatin structure can be modulated by posttranslational histone modifications, which may result either in alteration of the intrinsic properties of chromatin or in generation of anchoring regions for structural proteins (Taverna et al., 2007). One of the most commonly studied histone modifications related to chromatin structure is acetylation. Acetylation abolishes the charge attraction between the histones and DNA, resulting in decondensation of chromatin, which facilitates transcription (Lu et al., 2008). Specifically, acetylation of histone H4 at lysine 16 (H4K16) can interfere with DNA fiber compaction, and acetylation at this particular site is associated with active chromatin (Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006). Structural effects that lead to fiber decondensation and increased folding of nucleosomal arrays have been demonstrated to be secondary to acetylation of K16 in the H4 tail (Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006).

In this study, we investigated the relationship between PTEN function and chromatin structure and found that loss of PTEN leads to chromatin decondensation. Here we show that PTEN is involved in dynamic equilibrium of the chromatin structure, where loss of PTEN is associated with increased H4K16 acetylation and the open structure of active chromatin. Conversely, physical interaction of PTEN with histone H1 serves to maintain chromatin in a condensed status and repress the level of H4K16 acetylation. Through this mechanism, PTEN participates in genome-wide transcriptional regulation. Our study demonstrates features of a novel PTEN pathway that mediates resetting of gene expression profiles via alteration of chromatin structure.

RESULTS

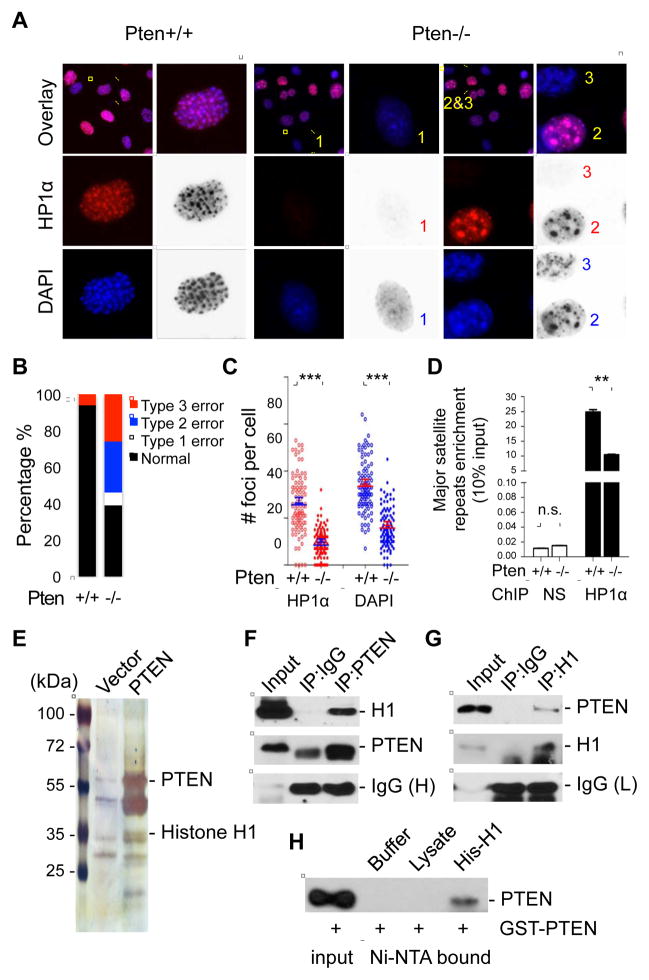

Loss of Pten Impairs Heterochromatic Distribution of HP1α

Nuclear PTEN maintains chromosomal integrity and contribute to the stabilization of intact centromeres in the nucleus (Shen et al., 2007). This led us to further investigate the role of PTEN in controlling higher order chromatin structure. The HP1 proteins, primarily HP1α, are fundamental elements of chromosomal architecture that are enriched in heterochromatin (Cheutin et al., 2003) and yet are also involved in euchromatic gene expression regulation (Kwon and Workman, 2011). Heterochromatic centers are highly condensed regions of heterochromatin with repetitive tandem DNA that can be visualized by DAPI staining. To investigate potential differences in the chromatin architecture between Pten knockout (Pten−/−) MEFs and wild-type (Pten+/+) MEFs, we examined HP1α and DAPI localization using immunofluorescence. In Pten+/+ MEFs, there was punctate nuclear staining of HP1α that showed extensive overlap with the DAPI-stained nuclear foci. In contrast, HP1α signals in Pten−/− cells exhibited several different types of abnormalities, including complete diffusion accompanied by similarly diffused DAPI signals (type 1), fewer enlarged foci (type 2) and exclusion from DAPI-stained heterochromatin (type 3, Figure 1A). Cumulative errors of HP1α foci formation occurred in over 60% of Pten null cells (Figure 1B). These errors may indicate abnormal chromocenter formation or redistribution of HP1α from heterochromatic foci to a homogenous pool, which is linked to impaired chromatin structural organization in the nucleus. There was a marked reduction in the number of HP1α foci in the nuclei of Pten−/− cells, as compared to that of Pten+/+ cells (Figure 1C). To further demonstrate the displacement of HP1 from pericentromeric heterochromatin, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay to assess the binding capacity of HP1α to pericentric major satellite repeats. A significant reduction in HP1α binding to major satellite DNA was observed in Pten−/− cells as compared with wild-type cells (Figure 1D). These data demonstrate that PTEN is important for the maintenance of pericentromeric HP1α, which is important for normal chromatin organization and gene silencing in constitutively heterochromatic regions.

Figure 1. PTEN regulates HP1α heterochromatic distribution and is physically associated with histone H1.

(A) Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs were subjected to immunofluorescent staining for HP1α. DNA was counterstained with DAPI. The selected cell was magnified and foci of HP1α or DAPI are also shown in both color and inverted gray scale. In Pten+/+ cells HP1α exhibited a speckled pattern confined to DAPI-dense heterochromatic regions, while three types of abnormal HP1α distribution were found in the nucleus of Pten−/− cells as indicated. Type 1, complete diffusion of HP1α and DAPI; Type 2, fewer (<10) enlarged foci of HP1α and DAPI; and type 3, HP1α diffusion with relative retention of DAPI foci.

(B) Stacked column chart illustrating the proportion of cells with different abnormalities of heterochromatic distribution in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs.

(C) HP1α and DAPI foci were counted in randomly selected Pten+/+ and Pten−/− cells (n=100. ***, p<0.001).

(D) ChIP-qPCR analysis of HP1α binding to major satellite repeats. A non-specific antibody (NS) was used as a control. **, p<0.01; n.s., no significance.

(E) Identification of histone H1 as a PTEN-associated protein by a FLAG-HA-PTEN pull-down assay.

(F and G) Reciprocal immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting of PTEN and histone H1 in Pten+/+ MEFs.

(H) In vitro binding assays using purified His-Histone H1 and GST-PTEN proteins.

See also Figure S1.

Identification of Histone H1 as a Novel PTEN-Interacting Protein

To identify potential interacting partners of nuclear PTEN in chromatin regulation, FLAG-HA (FH) tandem affinity purification was performed using nuclear extracts from HeLa cells with ectopic FH-PTEN. Bound proteins were eluted and resolved with SDS-PAGE. Mass spectrometry analysis of these PTEN interacting proteins identified several subtypes of histone H1 (Figure 1E).

As our experimental results indicated PTEN is involved in modulation of chromatin architecture, we then asked if PTEN physically interacts with histone H1. As several subtypes of histone H1 were identified by mass spectrometry, we employed two different antibodies that recognize histone H1, a pan-histone H1 antibody that recognizes different subtypes and a homemade antibody that specifically recognizes the H1.2 subtype of histone H1. To evaluate the association of PTEN with histone H1 in vivo, lysates of HeLa cells overexpressing FH-PTEN were immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG then immunoblotted with anti-H1.2 antibody (Figure S1A). This assay was repeated in wild-type MEFs and DLD-1 human colorectal adenocarcinoma cells, and in both these assays, PTEN was found to interact with both histone H1 in vivo (Figures 1F, 1G, S1B and S1C). In vitro assay also confirmed a direct interaction between PTEN and histone H1 (Figure 1H).

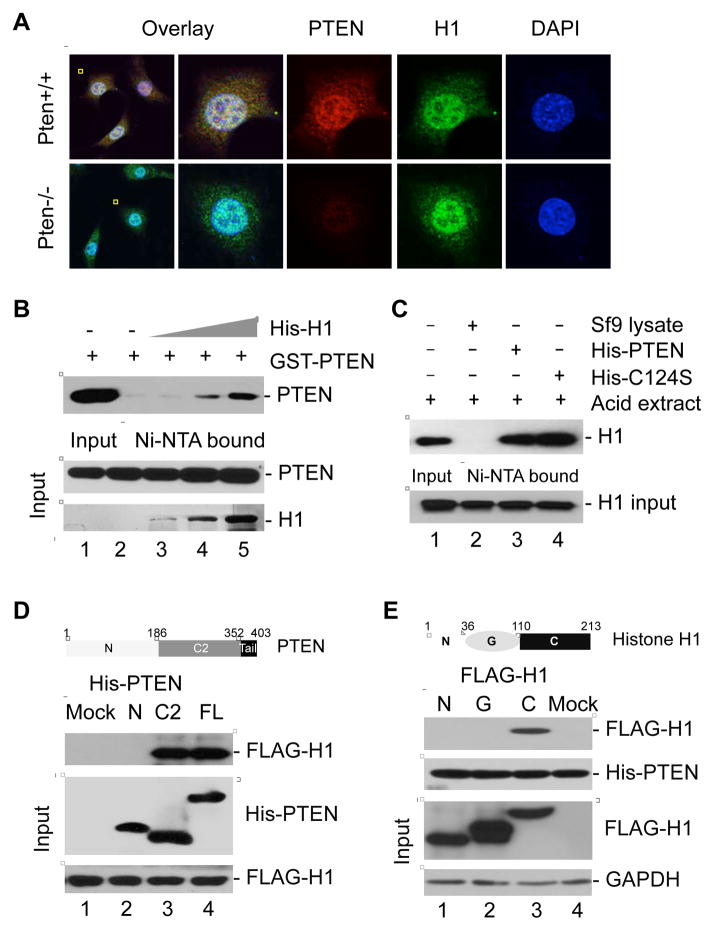

PTEN Interacts with the Histone H1 C-terminal Region

The physical association between PTEN and histone H1 was subsequently evaluated by immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy. We observed overlap of PTEN (red) and histone H1 (green) signals (Figure 2A), illustrating that a significant portion of nuclear PTEN may co-localize with histone H1. In addition, PTEN interacted with histione H1 in dose-dependent manner (Figure 2B). To determine whether PTEN phosphatase activity is required for the interaction of PTEN and histone H1, an in vitro binding assay comparing purified wild-type PTEN and a phosphatase-dead PTEN mutant (C124S) was carried out with purified histone H1. Histone H1 interacted equally well with both wild-type and phosphatase-dead PTEN (Figure 2C), indicating that PTEN interaction with histone H1 is phosphatase-independent. To further confirm this observation, FLAG-tagged histone H1.2 was incubated with full-length PTEN, the PTEN N-terminus, or the PTEN C2-domain for binding assays. Interestingly, histone H1 bound to full length PTEN and to the PTEN C2-domain, but not to the N-terminus, indicating that this interaction is mediated by the C2-domain (Figure 2D). Since the PTEN phosphatase domain is in its N-terminal region, these results argue that the PTEN-histone H1 interaction is independent of PTEN phosphatase activity.

Figure 2. PTEN physically interacts with the C-terminal region of histone H1.

(A) Confocal microscopy showing merged signals (yellow) of PTEN (red) with histone H1 (green) in Pten+/+ MEFs. Pten−/− cells were included as a control.

(B) GST-tagged PTEN was purified and incubated with increasing doses of purified His-H1.2 for in vitro detection of their direct association.

(C) His-tagged wild-type PTEN and a phosphatase-deficient PTEN mutant C124S were purified prior to incubation with an equal amount of acid-extracted native histones for detection of PTEN-bound histone H1.

(D) In vitro binding assay with FLAG-tagged full-length histone H1 and His-tagged different domains of PTEN as indicated. The domain structure of PTEN is given above the data.

(E) Different domains of histone H1.2 with a FLAG tag were used for in vitro binding assay with His-tagged full length PTEN. The diagram above the data shows different domains of histone H1.2.

To map the PTEN-binding domain of histone H1, three FLAG-tagged peptide segments of histone H1.2 spanning amino acids 1–36 (N-terminus), 37–110 (globular domain), and 111–213 (C-terminus) (Figure 2E), were expressed in 293T cells. Cell lysates were incubated with His-tagged full length PTEN on Ni-NTA beads. Immunoblotting of the Ni-NTA-bound elutes with an anti-FLAG antibody showed that only the C-terminus of H1 interacted with PTEN (Figure 2E), suggesting that the PTEN-related function with histone H1 resides in the C-terminal region.

PTEN Controls H1 Dynamic Motility on Chromatin and Higher Order Chromatin Structure

The C-terminus of histone H1 is critical for high-affinity binding to chromatin (Hendzel et al., 2004). This led us to ask whether PTEN affects the binding of histone H1 to chromatin. To answer this question, a salt extraction assay was used to investigate the association of histone H1 with chromatin in the presence and absence of PTEN. As shown in Figure 3A, the amount of histone H1 extracted with buffers containing 50 to 250 mM NaCl was much greater for nuclei isolated from Pten−/− cells than for those isolated from Pten+/+ cells. This observation was confirmed in two independent PTEN deficient systems, MEFs and DLD-1 cells (Figure 3A and S2A), in which loss of PTEN resulted in diminished binding of histone H1 to chromatin. Further sequential chromatin fractionation revealed that in the absence of Pten, chromatin-bound histone H1 was reduced whereas the soluble nuclear fraction contained a higher level of histone H1 (Figure 3B). These data indicate that Pten deletion results in redistribution of histone H1 and the removal of histone H1 from chromatin. A concomitant alteration of HP1α distribution was also observed, in which PTEN depletion reduced chromatin-bound HP1α (Figure 3B). These data illustrate the importance of PTEN in maintaining chromatin enrichment of both histone H1 and HP1α.

Figure 3. PTEN modulates dynamic motility of histone H1 in chromatin and loss of Pten leads to chromatin decondensation.

(A) Increasing concentrations of NaCl was used to extract nuclei from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs, followed by quantification of histone H1 and Npm1 released from nucleosomes. Lamin B was used to confirm equal protein loading in each pair of samples.

(B) A sequential cell fractionation procedure was used to separate cytoplasmic, nuclear soluble and chromatin fractions prior to immunoblot analysis of indicated protein molecules in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− cells.

(C) Co-immunoprecipitation of histone H1 with Hp1α and Npm1 in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs.

(D) FRAP analysis of GFP-histone H1 in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs (n=15). Bright GFP-H1 regions in the nucleus were selected for photo-bleaching and recovery observation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05.

(E) Chromatin accessibility assessed by sensitivity to Micrococcal nuclease (MNase) digestion. Nuclei from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs were prepared and digested with 0.2U/μl MNase for increasing periods of time. The MNase digestion profile is shown with mono-, di- and tri-nucleosomal repeats as indicated.

(F) Dose-dependent MNase digestion pattern of the chromatin from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs.

See also Figure S2.

We also noticed that loss of Pten reduced not only the amount of HP1α bound to chromatin (Figure 3B) but also reduced HP1α associated with histone H1 (Figure 3C). These results imply that PTEN maintains an H1-HP1α complex on chromatin, and in the absence of PTEN, this complex dissociates from chromatin and these proteins dissociate from each other. It is reported that NPM1 is a histone H1 chaperone (Gadad et al., 2011) and can modulate histone H1 transport and dynamics in nucleus. Interestingly, Pten deletion increased the association of histone H1 with its chaperone NPM1 (Figure 3C). These data suggest that induced formation of the H1-NPM1 complex in Pten-deficient cells leads to dissociation of both molecules from chromatin.

The dynamic binding properties of histone H1 to chromatin in vivo can regulate higher order chromatin structure (Contreras et al., 2003; Misteli et al., 2000). It has generally been recognized that GFP-H1 may serve as an indicator for chromatin plasticity (Meshorer et al., 2006). We therefore used this well-characterized GFP fusion protein combined with photobleaching to examine the dynamic binding affinity of histone H1 to chromatin in vivo. GFP-H1 was transiently expressed in both Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs. The overall recovery kinetics of GFP-H1 in Pten−/− nuclei was found to be significantly faster than recovery in Pten+/+ cells (Figure 3D), which was reversible by ectopic PTEN (Figure S2B). These observations indicate that PTEN can regulate the dynamic motility of H1 in vivo.

In order to determine whether absence of PTEN alters the overall level of chromatin condensation, we evaluate the chromatin condensation status using the Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) assay. MNase preferentially cleaves the linker regions between nucleosomes, and an open chromatin structure is consequently more readily cleaved than a closed chromatin structure. When digested with MNase over a time course or with increasing concentrations of MNase, nuclei prepared from Pten−/− cells showed much greater sensitivity to digestion than those from Pten+/+ cells (Figures 3E and 3F), suggesting that the linker regions in PTEN deficient cells were more accessible and therefor the chromatin was less condensed overall. This digestion profile was also observed in DLD-1 cells with PTEN deletion (Figures S2C and S2D). These results indicate that PTEN impacts the global structure of chromatin. Taken together with the previously observed interaction of PTEN and histone H1, these findings raise the possibility that PTEN acts cooperatively with histone H1 in chromatin organization.

PTEN Represses Global Acetylation Levels of H4K16

Acetylation adds negative charge to nucleosomes and thus loosens chromatin fibers resulting in overall chromatin decondensation (Clayton et al., 2006). We therefore sought to determine whether the chromatin decondensation observed in Pten−/− cells is associated with an increase in histone acetylation. Multiple site-specific acetylation antibodies against either histone H3 or H4 were used to screen for changes in acetylation status in Pten null cells. We observed a significant induction of histone H4 acetylation only at K16 (Figure S3A). Acetylation of H4K16 prevents condensation of nucleosome arrays into chromatin fibers and this modification is a marker for transcriptionally active chromatin (Akhtar and Becker, 2000; Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006).

As the amount of histone H1 released from chromatin increases with higher concentrations of NaCl, lysis buffers containing various concentrations of NaCl were used to collect lysates for immunoblotting of H4K16 acetylation. Lysates prepared with higher NaCl concentrations (400 mM) allowed greater release of core histones into the lysate. Consistent with our results using whole cell extracts (Figure S3A), lysates prepared with 100 and 400 mM NaCl both showed stronger H4K16 acetylation signals in PTEN null cells than that in PTEN wild-type cells (Figures 4A and S3B). However, H3K27 acetylation signals remained the same. Trichostatin A (TSA) is a histone deacetylase inhibitor that causes a general increase in acetylation and affects chromatin structure by inducing global histone hyperacetylation (Marks et al., 2001; Yoshida et al., 1995). When MEFs were treated with TSA to increase H4K16 acetylation levels, the presence of Pten was still capable of off-setting the effect of TSA and reducing acetylation to some extent (Figure S3C). These data demonstrate that PTEN depletion alters the acetylation status of histone H4 and induces H4K16 acetylation.

Figure 4. Loss of PTEN induces acetylation of histone H4 at K16 whereas enforced H4K16 acetylation Impairs PTEN-H1 interaction.

(A) Evaluation of acH4K16 and acH3K27 levels in low-salt and high-salt extractions from Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs.

(B) Chromatin-associated Hp1α, Mof and acH4K16 were evaluated in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs. Soluble and chromatin fractions were prepared and subjected to Western blotting with antibodies to indicated proteins.

(C) Human DLD-1 cells were treated with 2.5 μg/ml TSA for 12 h prior to immunoblot analysis of chromatin-bound H1 and HP1α.

(D) The association between PTEN and histone H1 was examined in DLD-1 cells with and without TSA treatment.

(E) Pten+/+ MEFs were transfected with wild type histone H4 or an acetylation-mimicking mutant K16Q, followed by PTEN immunoprecipitation and subsequent detection of histone H1.

See also Figure S3.

Histone acetylation is highly dynamic and is generally regulated by the opposing action of two families of enzymes, histone acetyltransferases and histone deacetylases (Bannister and Kouzarides, 2011). As our experimental observations indicated that PTEN prevents histone acetylation, we elected to explore the mechanism by which this occurs. The global enhancement of H4K16 acetylation associated with decreased levels of PTEN led us to consider the possibility PTEN complexes with a particular histone deacetylase. The major H4K16-specific histone acetyltransferase is MOF, which has high substrate specificity for H4K16 (Gupta et al., 2008). MOF is a component of a multi-subunit histone acetyltransferase complex that is responsible for most of the histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16 in mammalian cells (Dou et al., 2005; Smith et al., 2005). Since MOF is both necessary and sufficient for H4K16 acetylation in mammals (Dou et al., 2005; Li et al., 2012), it is possible that PTEN might affect the loading of MOF on histone H4 with consequent changes in the level of H4K16 acetylation. A comparison of the expression patterns of MOF in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− cells showed no significant difference in its mRNA or protein levels (data not shown). MOF binding on chromatin, which is closely correlated with the H4K16 acetylation level (Lu et al., 2010), was then evaluated by a chromatin retention assay. As expected, chromatin-bound MOF was elevated in Pten−/− cells (Figure 4B), and at the same time chromatin-bound acH4K16 was increased in Pten−/− cells. These data suggest that PTEN may prevent MOF from acetylating H4K16 on chromatin.

H4K16 Hyperacetylation Impairs Histone H1 Loading on Chromatin and PTEN-H1 Association

In order to obtain a comprehensive understanding of PTEN function in regulating molecular events involved in chromatin condensation, we designed experiments to delineate the interrelationship between PTEN-H1 interaction and H4K16 acetylation. We first assessed whether and how H4K16 acetylation status may affect the PTEN-H1 interaction as well as the chromatin enrichment of both H1 and HP1α. Global histone acetylation was induced by TSA treatment or H4K16 hyperacetylation was mimicked using a mutant protein. First, we evaluated the levels of chromatin-bound H1 and HP1α in response to TSA treatment. As shown in Figure 4C, TSA greatly increased H4K16 acetylation and consequently diminished chromatin-bound H1 and HP1α. Next, we analyzed PTEN-H1 interaction and found that TSA treatment dramatically diminished the association of PTEN with histone H1 (Figure 4D). In a similar manner, overexpression of an acetylation-mimicking H4 mutant K16Q significantly reduced PTEN-H1 interaction (Figure 4E). These results indicate that H4K16 hyperacetylation impairs the interaction of PTEN with histone H1.

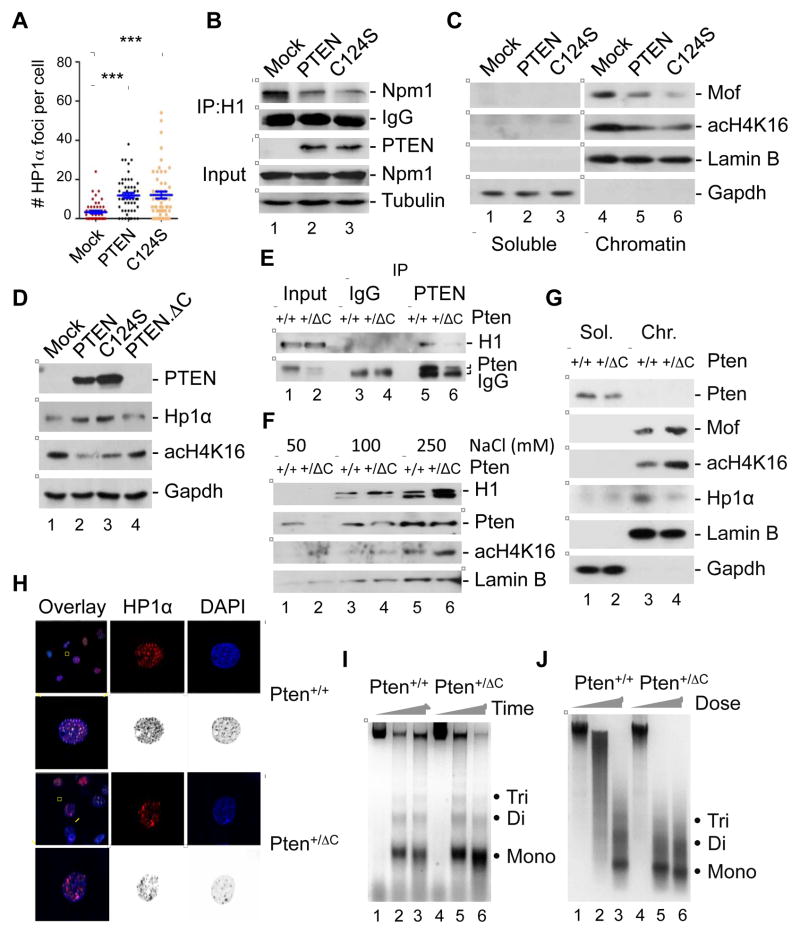

Regulation of H4K16 Acetylation and Chromatin Loading of HP1α is Independent of PTEN Phosphatase Activity

The binding region of PTEN with histone H1 mapped to the C-terminus of PTEN (Figure 2D), and a phosphatase-dead PTEN mutant C124S can bind histone H1 in vitro (Figure 2C). We next sought to determine whether the phosphatase activity of PTEN is required for regulating chromatin association of acH4K16 and HP1α. We found that both wild-type PTEN and the phosphatase-deficient C124S mutant increased chromatin loading of HP1α (Figure S4A). In agreement with these observations, both wild-type PTEN and the C124S mutant were able to restore HP1α heterochromatic foci formation (Figure 5A). We have shown that loss of Pten may induce NPM1-mediated dissociation of histone H1 from chromatin (Figures 3B and S3A). Therefore, PTEN maintains the chromatin association of histone H1 by blocking the H1-NPM1 interaction. We found that wild-type PTEN and the phosphatase-deficient C124S mutant were equally capable of reducing the H1-NPM1 interaction (Figure 5B). In addition, PTEN suppressed the levels of chromatin-bound MOF and acH4K16 in a phosphatase-independent manner (Figure 5C).

Figure 5. PTEN promotes chromatin association of histone H1 and suppresses H4K16 acetylation in a C-terminus-dependent but phosphatase-independent manner.

(A) Pten−/− MEFs transfected with PTEN or a phosphatase-deficient mutant C124S were immunofluorescent stained for HP1α. Numbers of nuclear HP1α foci are summarized in the graph (n=53). ***, p<0.001.

(B and C) Pten−/− MEFs transfected with wild-type PTEN and a phosphatase-deficient PTEN mutant (C124S) were subjected to evaluation of H1-NPM1 association (B) and chromatin-bound MOF and acH4K16 (C).

(D) HP1α expression and H4K16 acetylation were examined in Pten−/− MEFs transfected with wild-type full length PTEN, the phosphatase-dead C124S mutant and a truncated PTEN with C-terminal deletion, PTEN.ΔC.

(E) MEFs isolated from mouse embryo with heterozygous Pten C-terminal deletion (Pten+/ΔC) and a wild-type control embryo (Pten+/+) were used for evaluation of PTEN-H1 interaction by PTEN immunoprecipitation and histone H1 immunoblotting.

(F–J) Pten+/+ and Pten+/ΔC MEFs were subjected to salt extraction assay for examination of histone H1 retention and H4K16 acetylation (F), chromatin association of Mof, acH4K16 and Hp1α (G), immunofluorescent staining of HP1α (H), and MNase sensitivity (I and J).

See also Figure S4.

Deletion of the Pten C-terminus Reduces HP1α Chromatin Loading and Induces H4K16 Acetylation, Leading to Chromatin Decondensation

Although both wild-type PTEN and the C124S mutant were able to suppress H4K16 acetylation as well as to elevate HP1α expression and restore HP1α foci, a PTEN mutant lacking the C-terminus failed to do so (Figures 5D and S4B), indicating that the PTEN C-terminal region plays an indispensable role. In order to further determine the importance of the PTEN C-terminal region in histone modification and chromatin organization, we have recently generated a mouse strain with heterozygous deletion of the Pten C-terminus (Pten+/ΔC) (Sun et al., 2014). MEFs were isolated from Pten+/ΔC and Pten+/+ embryos and used for evaluation of the capacity of PTEN binding to histone H1, chromatin accessibility and chromatin association of HP1α, MOF, and histone H4. We found that C-terminal deleted Pten was less able to interact with histone H1 as compared with wild-type Pten (Figure 5E). A salt extraction assay revealed elevated chromatin dissociation of histone H1 in Pten+/ΔC MEFs (Figure 5F), similar to previous observations in Pten−/− cells (Figure 3A). In addition, chromatin-bound MOF and acH4K16 were greatly induced in Pten+/ΔC cells as compared with that in Pten+/+ cells (Figure 5G). Interestingly, Pten C-terminal deletion dramatically reduced the level of HP1α associated with chromatin (Figure 5G), in agreement with observations in the Pten depletion system (Figures 3B and 4B). This phenomenon was further confirmed by immunofluorescence data that indicated Pten+/ΔC cells exhibited diffuse HP1α signals with much less intensity (Figure 5H). Pten C-terminal deletion also resulted in an elevation of H1-NPM1 interaction (Figure S4C). As a consequence, chromatin became more accessible to MNase digestion (Figures 5I and 5J), in a manner similar to that observed in Pten null cells. These data suggest that the C-terminal region of PTEN is responsible for histone-chromatin interplay and chromatin condensation, which may account for the broad spectrum of PTEN biological function.

PTEN Modulates Gene Transcription Profiling through Regulation of H1 and acH4K16 Accessibility to Gene Promoters

Histone H1 is a structural component of chromatin, and its depletion is associated with a less condensed chromatin status. As such, PTEN loss may give rise to an open chromatin structure, and presumably thus lead to alterations of the gene expression profile. Previous studies of Pten−/− MEFs have in fact shown that the absence of PTEN alters gene expression (Carver et al., 2011; Li et al., 2006b; Mulholland et al., 2012; Vivanco et al., 2007). However, it is unknown whether PTEN C-terminal deletion may also alter the gene expression profile. We therefore took advantage of MEFs lacking the Pten C-terminus for microarray analysis and found large-scale changes in global gene expression profiles. Interestingly, over 70% of the total differentially expressed genes were upregulated and the percentage was even higher when only counting those with greater than 2-fold induction by Pten C-terminal deletion (Figure S5A). These data suggest that chromatin is less compact in cells lacking functional Pten, leading to overall activation of gene transcription. In order to examine how these affected genes reflect a global alteration of chromatin organization, we mapped both upregulated and downregulated genes on each chromosome (Figure S5B). Although regional clusters formed by genes in one direction versus the other, these differentially expressed genes interspersed throughout the genome. These observations illustrate that regional depletion of Pten C terminus caused a global alteration of the gene transcription profile.

Microarray analysis was repeated in two pairs of MEFs including Pten+/ΔC and Pten−/−, to compare with their counterpart control cells. Combined data confirmed the dominant upregulation of gene transcription, as indicated in volcano plot and heat map (Figures 6A and 6B). Through use of Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com), we chose a number of commonly upregulated genes for verification. These included the oncogenes Kras, Braf and Akt1; survival factors Bcl2 and Nfkb2; estrogen receptor Esr1, as well as tumor invasive factor Cd44 (Table S1). As shown in Figures 6C, 6D and S6A, the expression of multiple genes was elevated in PTEN−/−, Pten−/− and Pten+/ΔC cells, as compared to that in their counterpart control cells. These results indicate that PTEN affects gene expression patterns, likely through its C-terminal region.

Figure 6. Deletion of PTEN or Pten C terminus alters gene expression profiles and impacts the interplay of H1 and acH4K16 occupancy on gene promoters.

(A and B) Two pairs of MEFs (Pten+/+ and Pten−/−; Pten+/+ and Pten+/ΔC) were used for microarray analysis. Data were combined and processed in volcano plot (A) and heat map (B) to show significantly altered genes (p< 0.05) in cells lacking Pten or its C terminus. FC, fold change.

(C and D) Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis of Pten-regulated genes in two cell systems, PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells (C), and Pten+/+ and Pten+/ΔC MEFs (D).

(E and F) ChIP-qPCR analysis of non-specific antibody, histone H4, histone H1, and acH4K16 occupancy on the BCL2 and CD44 promoters in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− cells. Data are normalized and presented as mean ± SEM. *, p<0.05, **, p<0.01, ***, p<0.001.

See also Figures S5 and S6; Tables S1 and S2.

Based on our observation of the reduction of histone H1 incorporation in chromatin and induction of H4K16 acetylation in PTEN null cells, we propose that these changes may influence gene transcriptional regulation. We used histone H1 and acH4K16 antibodies to evaluate their promoter occupancy. Two upregulated genes confirmed by RT-PCR, BCL2 and CD44, were selected for assay by chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP). PTEN deletion reduced the ability of histone H1 to bind the promoters of BCL2 and CD44, whereas occupancy of acH4K16 on the promoters of these two genes was increased in PTEN−/− cells (Figures 6E and 6F). The upregulation of CD44 was confirmed in both Pten−/− and Pten+/ΔC cells (Figure S6B). Interestingly, PTEN depletion also reduced occupancy of HP1α and H3K9me3, on the CD44 promoter (Figure S6B), suggesting that transcription upregulation observed in PTEN-deficient cells may be attributed to release of the HP1α/H2K9me3 repressive marks from gene promoters. Moreover, we found a significant increase of MOF bound to the gene promoter (Figure S6D), wherease knockdown of Mof in Pten null cells partially reversed gene transcriptional upregulation (Figure S6E). Together, these data demonstrate a functional interplay between histone H1 and H4K16 acetylation in transcriptional regulation of PTEN target genes.

DISCUSSION

Regulation of the chromatin structure is a complex process, which is shaped by a broad range of epigenetic modifications including histone acetylation. In this study, we describe a previously unrecognized PTEN function, wherein PTEN acts to alter chromatin structure and plays a role in epigenetic regulation. We demonstrate that PTEN interacts with histone H1 in vivo and in vitro. These two molecules act cooperatively to repress H4K16 acetylation, and to maintain chromatin condensation as well as heterochromatic occupancy of HP1α. This mechanism appears to be a part of the cellular machinery that controls gene expression profiles through regulation of DNA accessibility and hierarchical levels of chromatin organization.

In this study PTEN deletion resulted in chromatin decondensation. Increases in chromatin sensitivity to MNase and susceptibility to histone extraction associated with PTEN deletion were too pronounced to be explained by changes at specific gene loci alone, and this PTEN associated mechanism thus appears to be global in its effect on chromatin. Both histone H1 occupancy and H4K16 deacetylation contribute to chromatin compaction (Robinson et al., 2008). Histone H1 modulates higher-order chromatin structure in vitro by stabilizing the interaction of nucleosomes and chromatin fibers (Catez et al., 2004; Phair et al., 2004). H4K16 acetylation inhibits the formation of compact 30-nanometer-like fibers and thus represents active chromatin (Shogren-Knaak et al., 2006). Although most of the previous research in this area has been conducted in model organisms such as Tetrahymena and Drosophila, in this study we have demonstrated that this model also applies in mammalian cells. Our data demonstrate that PTEN controls higher order chromatin structure not only through stabilization of linker histone H1 on chromatin but also through suppression of core histone acetylation. It is of importance to note that H4K16 hyperacetylation and PTEN-H1 dissociation may constitute a positive feedback regulation that facilitates accumulation of errors in histone loading and modification, leading to deterioration of chromatin architecture. H4K16 acetylation induced by disruption of PTEN may further disrupt PTEN interaction with histone H1, creating a highly open chromatin structure accessible for gene expression. This discovery provides the first mechanistic link between PTEN and epigenetic modification of chromatin.

Transcription regulation is a major regulatory mechanism in the hierarchy of the machinery that controls a cell. For example, p53 tumor suppressor acts as a transcription factor that regulates the transcription of a large number of downstream genes involved in critical cellular functions (Beckerman and Prives, 2010). As a tumor suppressor with a similar potency, PTEN has also been found to be important in controlling a wide range of cellular and physiological activities, such as chromosome stability and metabolism (Song et al., 2012; Yin and Shen, 2008). PTEN is also essential for embryonic development (Di Cristofano et al., 1998; Suzuki et al., 1998). To better understand how PTEN controls multiple fundamental biological processes, research efforts have been made to explore PTEN functions beyond its phosphatase activity. Previous studies using microarray analysis have revealed alteration of gene expression profiles following changes in PTEN status (Carver et al., 2011; Hong et al., 2000; Li et al., 2006b; Matsushima-Nishiu et al., 2001; Mulholland et al., 2012; Vivanco et al., 2007). However, there has been no explanation for how PTEN controls gene expression at the transcription level. Our study provides a mechanism underlying PTEN function in gene transcription modulation through interplay with histones and chromatin. Unlike canonical transcription factors, PTEN regulates global profiles of gene transcription. Instead of binding to specific gene promoters, PTEN physically interacts with histone H1 and maintains a condensed chromatin status and HP1α enrichment, thus suppressing gene transcription. In addition, PTEN can also represses gene transcription through inhibition of H4K16 acetylation as loss of PTEN results in elevation of acH4K16 that opens chromatin structure for transcription. Our findings significantly expand upon the current view of PTEN function in hierarchical control of fundamental biological processes and help understand potency of PTEN in embryonic development and tumor suppression.

We have previously demonstrated that PTEN maintains centromere stability (Shen et al., 2007). Results in this study corroborate these earlier findings by providing additional evidence that PTEN maintains the integrity of heterochromatin. Impaired heterochromatic HP1α foci formation and elevated kinetics of histone H1 exchange in the nuclei of Pten−/− cells account for chromatin decondensation, and these are potential causes of genomic instability. Therefore, PTEN function in tumor suppression may be attributed to its combined role in maintaining chromosomal stability and equilibrium of chromatin dynamics, as well as in regulation of epigenetic modification of chromatin.

Structural maintenance and functional regulation of chromatin domains involve dynamic motility and activity of chromatin-bound proteins. We provide evidence that PTEN governs chromatin structure by modulating chromatin-binding capacities and dynamics of proteins important for chromatin architecture, which ultimately influences gene transcription. We therefore propose that PTEN functions as a transcriptional repressor and PTEN modulates gene transcription through histone code editing and chromatin remodeling. Epigenetic alterations and chromatin remodeling play a vital role in both embryonic development and tumorigenesis, and our findings suggest this mechanism likely contributes to PTEN function in these processes. Our data represent a significant contribution to better understanding of the diverse function of PTEN in development and tumor suppression, which paves the way for further investigation of PTEN function in editing histone code and remodeling chromatin status. Our findings also suggest that global transcription deregulation secondary to PTEN loss or mutation may be a significant driving force in tumor development.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Affinity Purification of PTEN Protein Complex and Mass Spectrometry

Nuclear extracts were prepared from HeLa cells transfected with an empty plasmid or a plasmid with FLAG-HA-tagged PTEN. After incubation with M2 anti-FLAG resin (Sigma) and sequential wash, FLAG-HA-PTEN complex was then eluted by 3xFLAG peptide. Elutes were combined and concentrated for SDS-PAGE and silver staining. Visible protein bands were excised from the gel and subjected to mass spectrometric analysis.

Micrococcal Nuclease Sensitivity Assay and Salt Extraction Analyses

The micrococcal nuclease sensitivity assay and salt extraction analysis of chromatin were performed essentially as described previously (Kinkley et al., 2009; Kishi et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2011). The reactions were performed with different time points or increasing concentrations of MNase and quenched by adding EDTA. For salt extraction analysis, pelleted nuclei were resuspended in buffer A [0.32 M sucrose, 15 mM HEPES (pH 7.9), 60 mM KCl, 2 mM EDTA, 0.5 mM EGTA, 10% glycerol (v/v)] and incubated at 4°C for 30 min with various concentrations of NaCl.

Immunofluorescence and Confocal Microscopy

Exponentially growing cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PHEM (60 mM Pipes, 25 mM Hepes, 10 mM EGTA, and 2 mM MgCl2, pH 6.9) and permeablized for immunostaining with specified antibodies. Images were acquired using a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss 510 LSM). HP1α heterochromatic localization was quantified by manually counting HP1α foci in Z-stacked fluorescence images of 50–100 randomly chosen cells from at least two independent experiments.

FRAP

FRAP experiments were performed as previously described (Kishi et al., 2012; Melcer et al., 2012; Nissim-Rafinia and Meshorer, 2011). Live-cell microscopy was performed at 37 °C with a Leica SP5 inverted confocal microscope with a 488-nm argon laser line and a 63× objective. Scanning was bidirectional at the highest possible rate with a 14× zoom and a pinhole of 1 airy unit. Regions of interest (ROI) were selected from bright GFP-H1 regions in the nucleus and five single prebleach images were acquired before application of two iterations of bleach pulses. After bleaching, single-section images were then collected at 2-s intervals for 60 s. The bleached area was a square with 1212 pixels. Completeness of bleaching in three dimensions was confirmed by inspection of image stacks of fixed cells. All recovery and loss curves were generated from background-subtracted images. The fluorescence signal measured in the ROI was singly normalized to the prebleach signal. FRAP in an in vitro culture was calculated as R = (It – Ibg)/(Ib–Ibg), where Ib is the average intensity in the ROI before bleaching, It is the average intensity in the region of interest at time point t, and Ibg is the background signal determined in a region outside of the cell nucleus. Given that the bleaching efficiency in FRAP analysis in slice culture was different between the cells because of the differing depths from the sliced surface, the intensity in the ROI immediately after bleaching was normalized to 0. Data were analyzed by repeated measures ANOVA and are represented as mean ± SEM at each time point.

Chromatin Fractionation and Retention Assay

Sequential chromatin fractionation was performed as described previously (Mendez and Stillman, 2000). Cytosolic, nuclear soluble and chromatin fractions were then subjected to Western analysis of H1, HP1α and PTEN. For the chromatin retention assay, cells were lysed with NETN-100 buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0,100 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 0.5 % Nonidet P-40). Soluble fractions were collected by centrifugation and the pellets were washed followed by treatment with 0.2 M HCl to release histones or chromatin-bound proteins.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

ChIP assays were performed as described previously (Shen et al., 2007). Chromatin immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were column-purified for quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis (primers provided in Table S2) on an Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system. For statistical analysis, unpaired and two-tailed t-tests were performed with a 95% confidence interval.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. PTEN is physically associated with histone H1, related to Figure 1

(A) HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-HA-tagged PTEN were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody followed by immunoblotting with a histone H1.2 antibody.

(B and C) Reciprocal immunoprecipitation and Western analysis of PTEN-histone H1 interaction in DLD-1 cells.

Figure S2. PTEN maintains histone H1-mediated chromatin compaction, related to Figure 3

(A) Salt extraction assay in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells.

(B) FRAP analysis of GFP-histone H1 in Pten−/− MEFs with and without ectopic PTEN (n=13). Bright GFP-H1 regions in the nucleus were selected for photo-bleaching and recovery observation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, p<0.01.

(C and D) Time- and dose-dependent MNase assay in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells.

Figure S3. Loss of PTEN induces H4K16 acetylation, related to Figure 4

(A) Depletion of Pten induces H4K16 acetylation (acH4K16), shown by Western blot analysis of multiple histone acetylation markers in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs.

(B) Evaluation of acH4K16 and acH3K27 levels in low-salt and high-salt extractions from PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells.

(C) H4K16 acetylation was examined in TSA-treated Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs by Western analysis.

Figure S4. PTEN restores HP1 chromatin loading in a phosphatase-independent manner and loss of Pten C-terminus increases H1-NPM1 interaction, related to Figure 5

(A) Pten−/− MEFs with ectopic PTEN or the C124S mutant were subjected to chromatin fractionation and immunoblotting with specific antibodies as indicated.

(B) Immunofluorescence analysis of HP1α foci formation in Pten−/− MEFs transfected with wild-type PTEN, phosphatase-deficient C124S mutant and C-terminal truncated PTEN mutant (PTEN.ΔC) with a FLAG tag. FLAG immunofluorescence was used to label cells with positive transfection signals.

(C) Soluble and chromatin fractions extracted from Pten+/+ and Pten+/ΔC MEFs were subjected to histone H1 immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting analysis of NPM1.

Figure S5. PTEN C-terminal deletion leads to alterations of the global transcription profile, related to Figure 6

(A) Microarray analysis in Pten+/ΔC MEFs revealed a large number of genes that were differentially expressed as compared to Pten+/+ cells.

(B) Distribution of transcriptionally altered genes (fold change >2) on chromosomes.

Figure S6. PTEN depletion affects the accessibility of HP1α and MOF to gene promoters, related to Figure 6

(A) Quantitative real-time PCR verification of gene upregulation in Pten−/− MEFs as compared to wild type cells.

(B) Western blotting of Cd44 in two pairs of MEFs as indicated.

(C) ChIP-qPCR analysis of the CD44 promoter bound to HP1α or H3K9me3 in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells. A non-specific antibody was used as a control.

(D) MOF was immunoprecipitated from PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells for analysis of its binding capacity to the SP2 promoter.

(E) qPCR analysis of Bcl2 and Braf in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− with or without siMof.

Table S1. Selected pathways and gene affected by Pten C-terminal deletion, related to Figure 6

Table S2. List of oligonucleotide primer sequences used in this study, related to Figure 6

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Guangxi Wang, Zhong Zhang, Kristy Lamb, and other members of our laboratories for technical assistance and critical discussion. We thank Dr. Jiyang Yu (Merck Research Laboratories, NJ) for assistance with microarray analysis and Dr. Laifong Lee for helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by NIH grants R01GM100478 and R01CA133008 to W.H.S. and Y.Y., China National Major Scientific Program (973 Project-2010CB912202), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Key Project-30930021), Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Major Project-5100003), and Shu Fan Education and Research Foundation.

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Z.H.C. Y.Y. and W.H.S. designed the experiments; Z.H.C., M.Z., J.Y., and H.L. performed most of the experimental work. J.H. assisted Z.H.C. and H.L. in performing immunofluorescence and microscopic analysis; S.H. helped Z.H.C. and M.Z. with microarray analysis; P.W. helped perform ChIP and qPCR analysis; X.K. helped with cellular fractionation experiments; Z.H.C., M.A.M, Y.Y. and W.H.S. wrote the manuscript; and all authors edited and approved the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Akhtar A, Becker PB. Activation of transcription through histone H4 acetylation by MOF, an acetyltransferase essential for dosage compensation in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2000;5:367–375. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80431-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker SJ. PTEN enters the nuclear age. Cell. 2007;128:25–28. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bannister AJ, Kouzarides T. Regulation of chromatin by histone modifications. Cell Res. 2011;21:381–395. doi: 10.1038/cr.2011.22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckerman R, Prives C. Transcriptional regulation by p53. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2:a000935. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a000935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bednar J, Horowitz RA, Grigoryev SA, Carruthers LM, Hansen JC, Koster AJ, Woodcock CL. Nucleosomes, linker DNA, and linker histone form a unique structural motif that directs the higher-order folding and compaction of chromatin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14173–14178. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger SL. The complex language of chromatin regulation during transcription. Nature. 2007;447:407–412. doi: 10.1038/nature05915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantley LC, Neel BG. New insights into tumor suppression: PTEN suppresses tumor formation by restraining the phosphoinositide 3-kinase/AKT pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4240–4245. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver BS, Chapinski C, Wongvipat J, Hieronymus H, Chen Y, Chandarlapaty S, Arora VK, Le C, Koutcher J, Scher H, et al. Reciprocal feedback regulation of PI3K and androgen receptor signaling in PTEN-deficient prostate cancer. Cancer Cell. 2011;19:575–586. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catez F, Yang H, Tracey KJ, Reeves R, Misteli T, Bustin M. Network of dynamic interactions between histone H1 and high-mobility-group proteins in chromatin. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:4321–4328. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.10.4321-4328.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheutin T, McNairn AJ, Jenuwein T, Gilbert DM, Singh PB, Misteli T. Maintenance of stable heterochromatin domains by dynamic HP1 binding. Science. 2003;299:721–725. doi: 10.1126/science.1078572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton AL, Hazzalin CA, Mahadevan LC. Enhanced histone acetylation and transcription: a dynamic perspective. Mol Cell. 2006;23:289–296. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contreras A, Hale TK, Stenoien DL, Rosen JM, Mancini MA, Herrera RE. The dynamic mobility of histone H1 is regulated by cyclin/CDK phosphorylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:8626–8636. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.23.8626-8636.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Cristofano A, Pesce B, Cordon-Cardo C, Pandolfi PP. Pten is essential for embryonic development and tumour suppression. Nat Genet. 1998;19:348–355. doi: 10.1038/1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dou Y, Milne TA, Tackett AJ, Smith ER, Fukuda A, Wysocka J, Allis CD, Chait BT, Hess JL, Roeder RG. Physical association and coordinate function of the H3 K4 methyltransferase MLL1 and the H4 K16 acetyltransferase MOF. Cell. 2005;121:873–885. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman DJ, Li AG, Wei G, Li HH, Kertesz N, Lesche R, Whale AD, Martinez-Diaz H, Rozengurt N, Cardiff RD, et al. PTEN tumor suppressor regulates p53 protein levels and activity through phosphatase-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:117–130. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00021-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gadad SS, Senapati P, Syed SH, Rajan RE, Shandilya J, Swaminathan V, Chatterjee S, Colombo E, Dimitrov S, Pelicci PG, et al. The multifunctional protein nucleophosmin (NPM1) is a human linker histone H1 chaperone. Biochemistry. 2011;50:2780–2789. doi: 10.1021/bi101835j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbert N, Boyle S, Fiegler H, Woodfine K, Carter NP, Bickmore WA. Chromatin architecture of the human genome: gene-rich domains are enriched in open chromatin fibers. Cell. 2004;118:555–566. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Guerin-Peyrou TG, Sharma GG, Park C, Agarwal M, Ganju RK, Pandita S, Choi K, Sukumar S, Pandita RK, et al. The mammalian ortholog of Drosophila MOF that acetylates histone H4 lysine 16 is essential for embryogenesis and oncogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:397–409. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01045-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendzel MJ, Lever MA, Crawford E, Th’ng JP. The C-terminal domain is the primary determinant of histone H1 binding to chromatin in vivo. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:20028–20034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400070200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong TM, Yang PC, Peck K, Chen JJ, Yang SC, Chen YC, Wu CW. Profiling the downstream genes of tumor suppressor PTEN in lung cancer cells by complementary DNA microarray. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2000;23:355–363. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.23.3.4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinkley S, Staege H, Mohrmann G, Rohaly G, Schaub T, Kremmer E, Winterpacht A, Will H. SPOC1: a novel PHD-containing protein modulating chromatin structure and mitotic chromosome condensation. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:2946–2956. doi: 10.1242/jcs.047365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishi Y, Fujii Y, Hirabayashi Y, Gotoh Y. HMGA regulates the global chromatin state and neurogenic potential in neocortical precursor cells. Nat Neurosci. 2012;15:1127–1133. doi: 10.1038/nn.3165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon SH, Workman JL. The changing faces of HP1: From heterochromatin formation and gene silencing to euchromatic gene expression: HP1 acts as a positive regulator of transcription. Bioessays. 2011;33:280–289. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li AG, Piluso LG, Cai X, Wei G, Sellers WR, Liu X. Mechanistic insights into maintenance of high p53 acetylation by PTEN. Mol Cell. 2006a;23:575–587. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Hu Y, Huo Y, Liu M, Freeman D, Gao J, Liu X, Wu DC, Wu H. PTEN deletion leads to up-regulation of a secreted growth factor pleiotrophin. J Biol Chem. 2006b;281:10663–10668. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512509200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Yen C, Liaw D, Podsypanina K, Bose S, Wang SI, Puc J, Miliaresis C, Rodgers L, McCombie R, et al. PTEN, a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase gene mutated in human brain, breast, and prostate cancer. Science. 1997;275:1943–1947. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5308.1943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Li L, Pandey R, Byun JS, Gardner K, Qin Z, Dou Y. The histone acetyltransferase MOF is a key regulator of the embryonic stem cell core transcriptional network. Cell Stem Cell. 2012;11:163–178. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LY, Wood JL, Ye L, Minter-Dykhouse K, Saunders TL, Yu X, Chen J. Aurora A is essential for early embryonic development and tumor suppression. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31785–31790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805880200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu LY, Wu J, Ye L, Gavrilina GB, Saunders TL, Yu X. RNF8-dependent histone modifications regulate nucleosome removal during spermatogenesis. Dev Cell. 2010;18:371–384. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.01.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maehama T, Dixon JE. The tumor suppressor, PTEN/MMAC1, dephosphorylates the lipid second messenger, phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:13375–13378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.22.13375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks P, Rifkind RA, Richon VM, Breslow R, Miller T, Kelly WK. Histone deacetylases and cancer: causes and therapies. Nat Rev Cancer. 2001;1:194–202. doi: 10.1038/35106079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima-Nishiu M, Unoki M, Ono K, Tsunoda T, Minaguchi T, Kuramoto H, Nishida M, Satoh T, Tanaka T, Nakamura Y. Growth and gene expression profile analyses of endometrial cancer cells expressing exogenous PTEN. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3741–3749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melcer S, Hezroni H, Rand E, Nissim-Rafinia M, Skoultchi A, Stewart CL, Bustin M, Meshorer E. Histone modifications and lamin A regulate chromatin protein dynamics in early embryonic stem cell differentiation. Nat Commun. 2012;3:910. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez J, Stillman B. Chromatin association of human origin recognition complex, cdc6, and minichromosome maintenance proteins during the cell cycle: assembly of prereplication complexes in late mitosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:8602–8612. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.22.8602-8612.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshorer E, Yellajoshula D, George E, Scambler PJ, Brown DT, Misteli T. Hyperdynamic plasticity of chromatin proteins in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Dev Cell. 2006;10:105–116. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.10.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Misteli T, Gunjan A, Hock R, Bustin M, Brown DT. Dynamic binding of histone H1 to chromatin in living cells. Nature. 2000;408:877–881. doi: 10.1038/35048610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland DJ, Kobayashi N, Ruscetti M, Zhi A, Tran LM, Huang J, Gleave M, Wu H. Pten loss and RAS/MAPK activation cooperate to promote EMT and metastasis initiated from prostate cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2012;72:1878–1889. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-11-3132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers MP, Pass I, Batty IH, Van der Kaay J, Stolarov JP, Hemmings BA, Wigler MH, Downes CP, Tonks NK. The lipid phosphatase activity of PTEN is critical for its tumor supressor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13513–13518. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narlikar GJ, Fan HY, Kingston RE. Cooperation between complexes that regulate chromatin structure and transcription. Cell. 2002;108:475–487. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00654-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissim-Rafinia M, Meshorer E. Photobleaching assays (FRAP & FLIP) to measure chromatin protein dynamics in living embryonic stem cells. J Vis Exp. 2011 doi: 10.3791/2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phair RD, Scaffidi P, Elbi C, Vecerova J, Dey A, Ozato K, Brown DT, Hager G, Bustin M, Misteli T. Global nature of dynamic protein-chromatin interactions in vivo: three-dimensional genome scanning and dynamic interaction networks of chromatin proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:6393–6402. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.14.6393-6402.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson PJ, An W, Routh A, Martino F, Chapman L, Roeder RG, Rhodes D. 30 nm chromatin fibre decompaction requires both H4-K16 acetylation and linker histone eviction. J Mol Biol. 2008;381:816–825. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.04.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen WH, Balajee AS, Wang J, Wu H, Eng C, Pandolfi PP, Yin Y. Essential role for nuclear PTEN in maintaining chromosomal integrity. Cell. 2007;128:157–170. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shogren-Knaak M, Ishii H, Sun JM, Pazin MJ, Davie JR, Peterson CL. Histone H4-K16 acetylation controls chromatin structure and protein interactions. Science. 2006;311:844–847. doi: 10.1126/science.1124000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith ER, Cayrou C, Huang R, Lane WS, Cote J, Lucchesi JC. A human protein complex homologous to the Drosophila MSL complex is responsible for the majority of histone H4 acetylation at lysine 16. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:9175–9188. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.21.9175-9188.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MS, Carracedo A, Salmena L, Song SJ, Egia A, Malumbres M, Pandolfi PP. Nuclear PTEN regulates the APC-CDH1 tumor-suppressive complex in a phosphatase-independent manner. Cell. 2011;144:187–199. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MS, Salmena L, Pandolfi PP. The functions and regulation of the PTEN tumour suppressor. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrm3330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Z, Huang C, He J, Lamb KL, Kang X, Gu T, Shen WH, Yin Y. PTEN C-terminal deletion causes genomic instability and tumor development. Cell Rep. 2014;6:844–854. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki A, de la Pompa JL, Stambolic V, Elia AJ, Sasaki T, del Barco Barrantes I, Ho A, Wakeham A, Itie A, Khoo W, et al. High cancer susceptibility and embryonic lethality associated with mutation of the PTEN tumor suppressor gene in mice. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00488-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taverna SD, Li H, Ruthenburg AJ, Allis CD, Patel DJ. How chromatin-binding modules interpret histone modifications: lessons from professional pocket pickers. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:1025–1040. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ura K, Kurumizaka H, Dimitrov S, Almouzni G, Wolffe AP. Histone acetylation: influence on transcription, nucleosome mobility and positioning, and linker histone-dependent transcriptional repression. EMBO J. 1997;16:2096–2107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicent GP, Nacht AS, Font-Mateu J, Castellano G, Gaveglia L, Ballare C, Beato M. Four enzymes cooperate to displace histone H1 during the first minute of hormonal gene activation. Genes Dev. 2011;25:845–862. doi: 10.1101/gad.621811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco I, Palaskas N, Tran C, Finn SP, Getz G, Kennedy NJ, Jiao J, Rose J, Xie W, Loda M, et al. Identification of the JNK signaling pathway as a functional target of the tumor suppressor PTEN. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:555–569. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Chen Y, Lu LY, Wu Y, Paulsen MT, Ljungman M, Ferguson DO, Yu X. Chfr and RNF8 synergistically regulate ATM activation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:761–768. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang SM, Kim BJ, Norwood Toro L, Skoultchi AI. H1 linker histone promotes epigenetic silencing by regulating both DNA methylation and histone H3 methylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1708–1713. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1213266110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y, Shen WH. PTEN: a new guardian of the genome. Oncogene. 2008;27:5443–5453. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshida M, Horinouchi S, Beppu T. Trichostatin A and trapoxin: novel chemical probes for the role of histone acetylation in chromatin structure and function. Bioessays. 1995;17:423–430. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Cooke M, Panjwani S, Cao K, Krauth B, Ho PY, Medrzycki M, Berhe DT, Pan C, McDevitt TC, et al. Histone h1 depletion impairs embryonic stem cell differentiation. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002691. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. PTEN is physically associated with histone H1, related to Figure 1

(A) HeLa cells stably expressing FLAG-HA-tagged PTEN were subjected to immunoprecipitation with an anti-FLAG antibody followed by immunoblotting with a histone H1.2 antibody.

(B and C) Reciprocal immunoprecipitation and Western analysis of PTEN-histone H1 interaction in DLD-1 cells.

Figure S2. PTEN maintains histone H1-mediated chromatin compaction, related to Figure 3

(A) Salt extraction assay in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells.

(B) FRAP analysis of GFP-histone H1 in Pten−/− MEFs with and without ectopic PTEN (n=13). Bright GFP-H1 regions in the nucleus were selected for photo-bleaching and recovery observation. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. **, p<0.01.

(C and D) Time- and dose-dependent MNase assay in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells.

Figure S3. Loss of PTEN induces H4K16 acetylation, related to Figure 4

(A) Depletion of Pten induces H4K16 acetylation (acH4K16), shown by Western blot analysis of multiple histone acetylation markers in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs.

(B) Evaluation of acH4K16 and acH3K27 levels in low-salt and high-salt extractions from PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells.

(C) H4K16 acetylation was examined in TSA-treated Pten+/+ and Pten−/− MEFs by Western analysis.

Figure S4. PTEN restores HP1 chromatin loading in a phosphatase-independent manner and loss of Pten C-terminus increases H1-NPM1 interaction, related to Figure 5

(A) Pten−/− MEFs with ectopic PTEN or the C124S mutant were subjected to chromatin fractionation and immunoblotting with specific antibodies as indicated.

(B) Immunofluorescence analysis of HP1α foci formation in Pten−/− MEFs transfected with wild-type PTEN, phosphatase-deficient C124S mutant and C-terminal truncated PTEN mutant (PTEN.ΔC) with a FLAG tag. FLAG immunofluorescence was used to label cells with positive transfection signals.

(C) Soluble and chromatin fractions extracted from Pten+/+ and Pten+/ΔC MEFs were subjected to histone H1 immunoprecipitation followed by immunoblotting analysis of NPM1.

Figure S5. PTEN C-terminal deletion leads to alterations of the global transcription profile, related to Figure 6

(A) Microarray analysis in Pten+/ΔC MEFs revealed a large number of genes that were differentially expressed as compared to Pten+/+ cells.

(B) Distribution of transcriptionally altered genes (fold change >2) on chromosomes.

Figure S6. PTEN depletion affects the accessibility of HP1α and MOF to gene promoters, related to Figure 6

(A) Quantitative real-time PCR verification of gene upregulation in Pten−/− MEFs as compared to wild type cells.

(B) Western blotting of Cd44 in two pairs of MEFs as indicated.

(C) ChIP-qPCR analysis of the CD44 promoter bound to HP1α or H3K9me3 in PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells. A non-specific antibody was used as a control.

(D) MOF was immunoprecipitated from PTEN+/+ and PTEN−/− DLD-1 cells for analysis of its binding capacity to the SP2 promoter.

(E) qPCR analysis of Bcl2 and Braf in Pten+/+ and Pten−/− with or without siMof.

Table S1. Selected pathways and gene affected by Pten C-terminal deletion, related to Figure 6

Table S2. List of oligonucleotide primer sequences used in this study, related to Figure 6