Abstract

Currently there several diagnostic techniques that re used by radiologists and pulmonary physicians for lung cancer diagnostics. In several cases pneumothorax (PNTX) is induced and immediate action is needed. Both radiologists and pulmonary physicians can insert a chest tube for symptom relief. However; only pulmonary physicians and thoracic surgeons can provide a permanent solution for the patient. The final solution would be for a patient to undergo surgery for a final solution. In our current work we will provide all those diagnostic cases where PNTX is induced and treatment from the point of view of expert radiologists and pulmonary physicians.

Keywords: Pneumothorax (PNTX), bronchoscopy, transbrochial needle aspiration, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS)

Introduction

Bronchoscopy was initially developed in 1895 for the purpose of removing foreign bodies from the main stem bronchi, when Gustav Killian removed a piece of bone from the right main-stem bronchus of a 36-year-old man. In the year 1968, Shigeto Ikeda introduced flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy for clinical use. It became more used that rigid bronchoscopy and it was confirmed in 1980’s, that flexible bronchoscopy with topical anesthesia was safer than rigid bronchoscopy (1,2). Although new studies suggest that the annual referral rate for rigid bronchoscopy has been rising since 2007, which demonstrates the varying diagnostic and therapeutic modalities available and highlight the favorable morbidity rates and 100% diagnostic rates for this safe procedure, this book chapter will focus on flexible bronchoscopy transbronchial biopsy, its associated complications—primarily pneumothorax (PNTX), and management strategies (3,4).

Nearly 500,000 bronchoscopies are done each year in the United States. The number and complexity of procedures that can be performed in the bronchoscopy unit is increasing. These procedures carry inherent risks, and patient safety is of paramount concern. Flexible bronchoscopy is an invasive procedure that is utilized to visualize the nasal passages, pharynx, larynx, vocal cords, and tracheal bronchial tree. It is utilized for both the diagnosis and treatment of lung disorders. The procedure may be performed in an endoscopy suite, the operating room, the emergency department, a radiology suite, or at the bedside in the ICU. Flexible bronchoscopy has revolutionized the practice of pulmonary medicine, enhanced our understanding of pulmonary disease, and has evolved into the most commonly used invasive diagnostic as well as therapeutic procedure. Bronchoscopy is widely carried out today by pulmonologists, thoracic surgeons, critical care specialists, otolaryngologists, anesthesiologists and pediatric pulmonologists (1,5).

Many interventional bronchology procedures for the diagnosis and treatment of lung illnesses can be performed on an outpatient basis or during a short hospital stay. The problem most responsible for complicating outpatient management, after needle biopsy was performed, is not the presence of the PNTX per se, but an increase in the size of the PNTX that requires chest tube placement and patient hospitalization. The risks and benefits of the procedure and knowledge of the wishes of the patient will enable the management decision to be tailored to the needs of the individual (6,7).

Bronchoscopic lung biopsy

Lung biopsy is a relatively frequently performed procedure with considerable benefit for patient management but it may, on rare occasions, give complications or even result in the death of the patient. It is a multidisciplinary procedure involving respiratory physicians, bronchologists, radiologists and surgeons with an interest in chest diseases. It is integral in the diagnosis and treatment of many thoracic diseases, and is an important alternative to more invasive surgical procedures.

Classification of lung biopsies may be done according to the method of access (percutaneously, bronchoscopically, open operation) or by the reason for biopsy (sampling of diffuse lung disease or obtaining tissue from a mass when malignancy is suspected) (8,9).

Biopsy via a bronchoscope is useful for proximal endobronchial lesions but is unable to access more peripheral lesions. Transbronchial biopsy is generally done with two main types of forceps; cup forceps (without teeth) and the alligator forceps (saw-toothed). It is noted that the alligator-type forceps are being used less than the cup, as the teeth tend to tear tissue and cause hemoptysis (1).

Biopsy of diffuse infiltrates is more likely to provide diagnosis than small peripheral nodules. Overall yield from bronchoscopic lung biopsy is reported to be 72%. The American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society Consensus recommends bronchoscopic lung biopsy not for the diagnosis of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias but for the exclusion of sarcoidosis, infections and lymphangitis carcinomatosis (10,11). Transbronchial biopsy of diffuse lung disease may be assisted by some imaging guidance. High resolution computed tomography (CT) might be helpful in deciding which areas should be targeted to improve diagnostic yield and areas that should be avoided, such as bullae or vascular abnormalities. Because it does not cross the pleura, PNTX is much less common than in percutaneous biopsy (12).

Technique

Ideally, the technique must not only be able to diagnose malignancy but also to make a definite diagnosis if the lesion is benign. transbronchial needle biopsy (TBNB) usually begins with review of the chest radiograph and, in most instances, is greatly facilitated by a CT scan. Knowledge of the anatomy is critical for selecting the proper anatomic location for the needle aspiration or biopsy. This is true for selecting the proper location of a peripheral lesion that is to be sampled. For peripheral lesions, fluoroscopy is used to localize the lesion (12).

At minimum, the equipment needed is a bronchoscope, light source, cytology brushes, biopsy forceps, needle aspiration catheters, suction apparatus, supplemental oxygen, fluoroscopy (C-arm), pulse oximetry, sphygmomanometer, and equipment for resuscitation including an endotracheal tube. A video monitor is a useful accessory, but not required. Fluoroscopy may be needed to facilitate certain transbronchial biopsy procedures (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A bronchoscopy suite.

Both therapeutic and diagnostic procedures can be performed during flexible bronchoscopy. Depending on the indication, the following diagnostic procedures can be performed: BAL, endobronchial or transbronchial biopsies, cytologic wash or brush, and TBNA, endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS), and autofluorescence bronchoscopy. Therapeutic procedures and selected stent placement can all be accomplished through flexible bronchoscopy (5).

Indications

The first indication for fiberoptic bronchoscopy is identification of an indeterminate lung lesion identified on the chest X-ray. When transbronchial biopsy is added to flexible bronchoscopy, the most common indications are those conditions in which histopathology is important in therapeutic decision making, such as lung transplantation and rare or unusual parenchymal lung diseases. Diagnostic and staging information in the presence of malignancy in mediastinal lymph nodes, are also indications for TBNB.

Most contraindications to flexible bronchoscopy are relative rather than absolute they include: uncooperative patient, recent myocardial infarction, tracheal obstruction or stenosis, moderate to severe hypoxemia or any degree of hypercarbia, uremia and pulmonary hypertension (possible serious hemorrhage after biopsy), unstable asthma, bleeding disorders, immunosuppression, respiratory failure or insufficiency, cardiac arrhythmias. Special attention must be paid to respiratory and bleeding status. In unstable patients or prolonged procedures, rigid bronchoscopy may be preferred (1,5).

Safety of TBNB in patients with COPD and pulmonary hypertension

Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is being used increasingly as a diagnostic and research tool in patients with COPD to assess airway pathology and the effects of treatment. Previous reports have shown bronchoscopy and bronchial biopsy procedures to be safe in asthmatic patients, but there is little safety data specific to COPD. Guidelines suggest that bronchoscopy may be safer in patients with COPD than with asthma because of lower levels of bronchial hyperresponsiveness. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy is a relatively invasive procedure for investigating patients with COPD, but it allows for the detection of coexisting endobronchial pathology and allows multiple samples of both tissue and fluid phase material to be obtained for research or diagnostic purposes (13,14).

Patients with pulmonary hypertension (PH) are considered to be at risk for complications associated with flexible bronchoscopy. Although previous reports suggest that transbronchial biopsies increase the risk for hemorrhage in this population, review of patients with diagnosis of PH who underwent flexible bronchoscopy at the Cleveland Clinic between 2002 and 2005. Total of 90 patients, showed that flexible bronchoscopy can be performed safely in patients with mild to moderate PH. Transbronchial biopsies were not associated with worsening hypoxemia or an increased risk of hemorrhage. Prospective studies with hemodynamic measurements are necessary to confirm these findings (15).

Safety of new bronchoscopic modalities

In 2007, a randomized trial study was performed on 120 patients, to examine influence of new bronchoscopic modalities on incidence of pneumothoraces, using EBUS and electromagnetic navigation bronchoscopy (ENB). These two modalities have increased the diagnostic yield of bronchoscopic diagnosis. All procedures were performed via flexible bronchoscopy and transbronchial forceps biopsies were obtained without fluoroscopic guidance. The PNTX rates ranged from 5% to 8%, with no significant differences between the groups. Four cases were treated with chest drains. No cases of bleeding that required therapeutic interventions, were recorded. It was concluded that combined EBUS and ENB improved the diagnostic yield of flexible bronchoscopy without compromising safety (16).

Complications

Diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy with TBNB is usually very safe procedure as long as some basic precautions are taken. Two most common complications are bleeding and PNTX. Major complications such as bleeding, respiratory depression, cardiorespiratory arrest, arrhythmia, pneumomediastinum and PNTX occur in <1% of cases. Hemorrhage is more likely in uraemic or immunosuppressed patients. Significant bleeding rarely occurs even after a major vessel puncture. Fever and bacteremia have been reported following the procedure, although this may be related to the bronchoscopic procedure itself rather than this specific technique. Mortality is rare, with a reported death rate of 0% to 0.04% in >68,000 procedures. Therefore, caution should be taken and healthcare providers must be prepared for these emergencies (1,5,7,17). According to recent nationwide survey from Japan, the complication rate after forceps biopsy for a peripheral pulmonary lesion was 1.79%. In comparison, in USA a review of 173 procedures from university hospital has reported a complication rate of 6.8% after TBB (18,19).

Bleeding

The reported incidence of bleeding after TBNB has varied from 0% to 26% in different series (20). The risk of bleeding is significantly higher in patients with underlying renal insufficiency (12,13). A major bleeding complication after transbronchial biopsy is unnerving but the bleeding can be controlled in the majority of cases in the bronchoscopy room without adverse patient outcome. The most effective way to control the bleeding is to maintain the bronchoscope in wedged position into bleeding segment till a blood clot is formed (21,22).

Pneumothorax

Definition of PNTX is presence of gas in the pleural space. By cause, it can be spontaneous, traumatic and iatrogenic. Occult pneumothoraces are a relatively recent radiological phenomenon. They are defined as pneumothoraces detected with thoracic or abdominal CT that were not diagnosed on preceding supine anteroposterior chest radiography. However, most pneumothoraces are iatrogenic and caused by a physician during surgery, central line placement, lung biopsy or bronchoscopy. PNTX is a rare complication of bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsy (23-25).

Acutely symptomatic pneumothoraces may develop at the time of the transbronchial biopsy procedure and require immediate drainage. Smaller or better tolerated pneumothoraces will be detected on post bronchoscopy chest radiographs. Acute presentation is usually with acute ipsilateral chest pain and dyspnoea. Clinical findings may be minimal or may include diminished breath sounds and mediastinal shift. In a tension PNTX the patient may become tachycardic and hypotensive and develop cyanosis. Monitoring of oxygen saturation is advised, together with the administration of oxygen as necessary. In an acutely unwell patient a chest radiograph or CT scan can be used to identify whether symptoms relate to pulmonary haemorrhage or PNTX (12).

Timing of chest radiography

Several studies have shown that most significant pneumothoraces will be detected on a chest radiograph performed 1 hour after the procedure, although they may not be visible on radiographs taken immediately after the procedure (26-28). Occasional delayed pneumothoraces have been reported more than 24 hours after biopsy, despite the absence of a PNTX on chest radiographs taken 4 hours after biopsy (29,30).

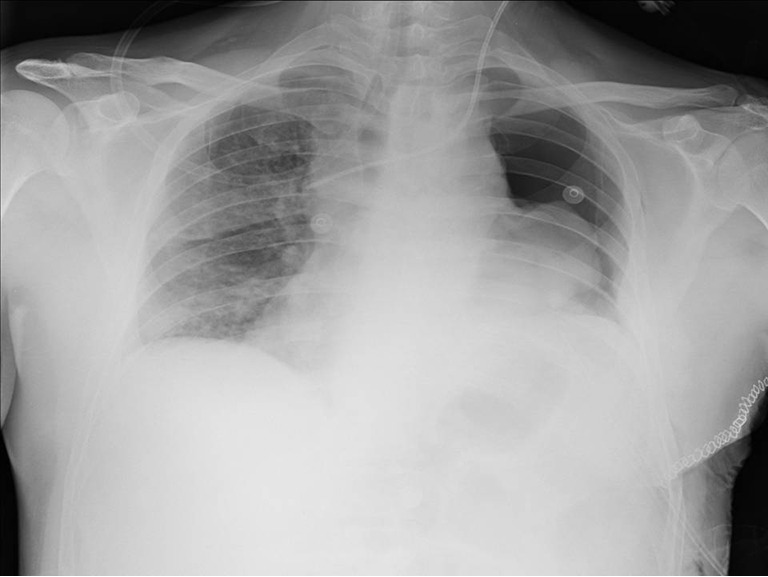

The need for routine chest X-ray after fiberoptic bronchoscopy was advised but never fully implemented, so a very recent study on 454 patients was done in 2013 to assess the incidence of post bronchoscopy PNTX and to determine the need for routine post- fiberoptic bronchoscopy X-rays. Of 454 total fiberoptic bronchoscopies, only 1 case (0.22%) resulted in iatrogenic PNTX which was diagnosed clinically, confirmed with chest X-ray and required thoracotomy. From the data obtained it was concluded that routine chest X-ray after fiberoptic bronchoscopy may not be cost-effective or even medically necessary in patients without clinical evidence of PNTX (12) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Routine chest X-ray after transbronchial needle biopsy (TBNB) reveals partial pneumothorax on the left.

PNTX is reported in literature in 1-6% of patients after TBNB. Mild to moderate PNTX can cause disproportionate symptoms due to underlying pulmonary limitation in some patients undergoing flexible bronchoscopy. Appropriate fluoroscopic guidance during TBNB reduces the risk of PNTX. Chest roentgenogram is recommended to be performed after ½ to 1 h after completion of biopsies, when the PNTX is clinically suspected despite normal findings on immediate post-bronchoscopy fluoroscopy. Fluoroscopic examination detects PNTX immediately after the biopsies, but in some cases slowly developing delayed PNTX can manifest several hours after completion of procedure. If no symptoms develop for 4 hours after completion of procedure, a clinically significant PNTX is unlikely (22,31,32).

Failure to control coughing during transbronchial biopsy greatly increases the risk of PNTX. Patients receiving positive pressure ventilation are also more likely to develop PNTX after TBNB. Risk may also be higher in presence of bullous emphysema and in patients with pneumocystis pneumonia. There are potential advantages of fluoroscopy when performing transbronchial biopsies in subjects with localized peripheral lesions. Severity of symptoms and the extent on chest roentgenogram dictate the management of PNTX after TBNB (17,33).

A large study was published in 2011 by Garcha, et al. of incidence and management of PNTX post-flexible bronchoscopy (FB). Out of 2,365 patients who underwent FB, 14 developed PNTX. Majority of the patients (93%) who developed PNTX had undergone transbronchial biopsies. Average number of transbronchial biopsy procedures was 5. Incidence of PNTX was 0.006%, with a mortality rate of 0.0004%. This complication rate reported was much lower than in previously published studies. Lung nodules and lung infiltrates were the most common indication for FB. Majority of patients were asymptomatic and PNTX was detected on routine fluoroscopy post procedure. 21% developed chest pain post procedure leading to the diagnosis. All of the patients required a tube thoracostomy for management of PNTX and were admitted to hospital for a short stay and there was one death directly related to development of tension PNTX. Although TBNB is assumed to be primary risk for PNTX, the majority of patients had other associated peripheral lung instrumentation. In new advanced techniques that were employed (ENB and EBUS), only 2 had pneumothoraces, representing 7% of the cases after ENB and EBUS (34).

In addition, two large retrospective studies of over 4,000 cases, using bronchoscopy with transbronchial biopsies, the latter in lung transplant recipients, showed no deaths and overall major and minor complication rates of 0.5% and 0.8%, respectively (19,35). Somewhat higher incidence of PNTX was reported to be 14% in a group of patients having transbronchial biopsies, while being mechanically ventilated (36).

A retrospective study published in 2004. In Chest journal, reviewed all patients with iatrogenic PNTX during 4-year period. Out of 86 patients, the most common cause reported to be central venous catheter placement, then thoracentesis, transthoracic needle aspiration biopsy (ten patients) and only one patient with PNTX after TBNB (37).

Management options

Where a PNTX is detected following a transbronchial biopsy procedure, the management options include observation, aspiration, or drain insertion. This decision will be affected by factors such as the size of PNTX, co-existent lung pathology such as emphysema affecting respiratory reserve, and severity of symptoms. BTS guidelines on the management of PNTX suggest initial treatment by aspiration, with subsequent drainage if a leak and significant PNTX persist (38). Supplemental oxygen and observation in the hospital is sufficient in most cases. Moderately symptomatic patients with significant PNTX may be managed with Heimlich’s valve placed in the bronchoscopy suite. These patients can be discharged with Heimlich’s valve after 4-6 h of observation, if repeat chest roentgenogram shows no further increase in PNTX. Patients who develop severe symptoms or tension PNTX, and those who fail to show resolution of PNTX with Heimlich’s valve require chest tube placement. Chest tube should also be placed without further delay when PNTX develops on mechanical ventilation (22). In the UK most clinicians attach drains to an underwater seal, but the Heimlich one way flutter valve is an alternative. This valve allows prolonged drainage for a PNTX and outpatient management. If the PNTX continues to enlarge or the patient develops surgical emphysema, the flutter valve can be replaced by a system attached to an underwater seal (39).

A major PNTX requiring drainage is reported to be in 3.5% of patients undergoing bronchoscopy (40-50) from which transbronchial biopsy specimens were taken (51-62).

Conclusions

Transbronchial biopsy is an essential skill for every bronchoscopist. TBNB is usually performed in outpatient setting under conscious sedation. If successfully performed, it may spare patients additional, more invasive procedures or surgery. Hemoptysis and PNTX are the two leading complications of TBNB, occurring in less than 2% of cases. PNTX is one of the major complications of FB, which can be life threatening if not managed in timely fashion. A major PNTX requiring drainage reported to be in 3.5% of patients undergoing bronchoscopy from which transbronchial biopsy specimens were taken. All bronchoscopists must develop proficiency in performing TBNB and managing complications that can arise after the procedure.

Acknowledgements

Disclosure: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Bolliger CT, Mathur PN. Interventional Bronchoscopy. New York: S Karger Pub, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lukomsky GI, Ovchinnikov AA, Bilal A. Complications of bronchoscopy: comparison of rigid bronchoscopy under general anesthesia and flexible fiberoptic bronchoscopy under topical anesthesia. Chest 1981;79:316-21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bacon JL, Leaver SK, Madden BP. P200 Six Year Experience with Rigid Bronchoscopy: Complications, Indications and Changing Referral Patterns. Thorax 2012;67:A151-2 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee P, Mehta AC, Mathur PN. Management of complications from diagnostic and interventional bronchoscopy. Respirology 2009;14:940-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ernst A, Silvestri GA, Johnstone D, et al. Interventional pulmonary procedures: Guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians. Chest 2003;123:1693-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown KT, Brody LA, Getrajdman GI, et al. Outpatient treatment of iatrogenic pneumothorax after needle biopsy. Radiology 1997;205:249-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gurley MB, Richli WR, Waugh KA. Outpatient management of pneumothorax after fine-needle aspiration: economic advantages for the hospital and patient. Radiology 1998;209:717-22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaham D.Semi-invasive and invasive procedures for the diagnosis and staging of lung cancer. I. Percutaneous transthoracic needle biopsy. Radiol Clin North Am 2000;38:525-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yankelevitz DF, Vazquez M, Henschke CI. Special techniques in transthoracic needle biopsy of pulmonary nodules. Radiol Clin North Am 2000;38:267-79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Descombes E, Gardiol D, Leuenberger P.Transbronchial lung biopsy: an analysis of 530 cases with reference to the number of samples. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis 1997;52:324-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society . American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Manhire A, Charig M, Clelland C, et al. Guidelines for radiologically guided lung biopsy. Thorax 2003;58:920-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hattotuwa K, Gamble EA, O’Shaughnessy T, et al. Safety of bronchoscopy, biopsy, and BAL in research patients with COPD. Chest 2002;122:1909-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Da Conceiçao M, Genco G, Favier JC, et al. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy during noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation in patients with chronic obstructive lung disease with hypoxemia and hypercapnia. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim 2000;19:231-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diaz-Guzman E, Vadi S, Minai OA, et al. Safety of diagnostic bronchoscopy in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Respiration 2009;77:292-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eberhardt R, Anantham D, Ernst A, et al. Multimodality bronchoscopic diagnosis of peripheral lung lesions: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:36-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.British Thoracic Society Bronchoscopy Guidelines Committee , a Subcommittee of Standards of Care Committee of British Thoracic Society. British Thoracic Society guidelines on diagnostic flexible bronchoscopy. Thorax 2001;56Suppl 1:i1-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asano F, Aoe M, Ohsaki Y, et al. Deaths and complications associated with respiratory endoscopy: a survey by the Japan Society for Respiratory Endoscopy in 2010. Respirology 2012;17:478-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pue CA, Pacht ER. Complications of fiberoptic bronchoscopy at a university hospital. Chest 1995;107:430-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Milman N, Faurschou P, Munch EP, et al. Transbronchial lung biopsy through the fibre optic bronchoscope. Results and complications in 452 examinations. Respir Med 1994;88:749-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordasco EM, Jr, Mehta AC, Ahmad M. Bronchoscopically induced bleeding. A summary of nine years’ Cleveland clinic experience and review of the literature. Chest 1991;100:1141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mehta A, Jain P. eds. Interventional Bronchoscopy: A Clinical Guide. New York: Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ball CG, Hameed SM, Evans D, et al. Occult pneumothorax in the mechanically ventilated trauma patient. Can J Surg 2003;46:373-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ball CG, Kirkpatrick AW, Feliciano DV. The occult pneumothorax: what have we learned? Can J Surg 2009;52:E173-9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Patolia S, Zahir M, Schmidt F, et al. Bilateral pneumothorax after bronchoscopy without biopsy--a rare complication: case presentation and literature review. J Bronchology Interv Pulmonol 2012;19:57-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Charig MJ, Phillips AJ. CT-guided cutting needle biopsy of lung lesions--safety and efficacy of an out-patient service. Clin Radiol 2000;55:964-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown KT, Brody LA, Getrajdman GI, et al. Outpatient treatment of iatrogenic pneumothorax after needle biopsy. Radiology 1997;205:249-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traill ZC, Gleeson FV. Delayed pneumothorax after CT-guided percutaneous fine needle aspiration lung biopsy. Thorax 1997;52:581-2; discussion 575-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koh DM, Burke S, Davies N, et al. Transthoracic US of the chest: clinical uses and applications. Radiographics 2002;22:e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sun SW, Zabaneh RN, Carrey Z. Incidence of Pneumothorax after Fiberoptic Bronchoscopy (FOB) in Community-Based Hospital; Are Routine Post-procedure Chest Roentgenograms Necessary? Chest 2003;124:145S-a-146S [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tamm M, Sharples LD, Higenbottam TW, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome in heart-lung transplantation: surveillance biopsies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;155:1705-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Alamoudi OS, Attar SM, Ghabrah TM, et al. Bronchoscopy, indications, safety and complications. Saudi Med J 2000;21:1043-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ahmad M, Livingston DR, Golish JA, et al. The safety of outpatient transbronchial biopsy. Chest 1986;90:403-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcha PS, Santacruz JF, Jaber WS, et al. Pneumothorax Post Flexible Bronchoscopy. ATS Journals 2011;183:A2351 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Smith L, Singer JP, Hayes M, et al. An analysis of potential risk factors for early complications from fiberoptic bronchoscopy in lung transplant recipients. Transpl Int 2012;25:172-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.O’Brien JD, Ettinger NA, Shevlin D, et al. Safety and yield of transbronchial biopsy in mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med 1997;25:440-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kogos A, Alakhras M, Hossain Z, et al. Iatrogenic Pneumothorax: Etiology, Morbidity, and Mortality. Chest 2004;126:893S [Google Scholar]

- 38.Henry M, Arnold T, Harvey J, et al. BTS guidelines for the management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax 2003;58Suppl 2:ii39-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shepard JA. Complications of Percutaneous Needle Aspiration Biopsy of the Chest: Prevention and Management. Semin Intervent Radiol 1994;11:181-6 [Google Scholar]

- 40.Milman N, Munch EP, Faurschou P, et al. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy in local anaesthesia: Indications, results and complications in 1323 examinations. Acta Endoscopica 1993;23:151-62 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tsakiridis K, Mpakas A, Kesisis G, et al. Lung inflammatory response syndrome after cardiac-operations and treatment of lornoxicam. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S78-98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P, Vretzkakis G, et al. Effect of lornoxicam in lung inflammatory response syndrome after operations for cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S7-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Argiriou M, Kolokotron SM, Sakellaridis T, et al. Right heart failure post left ventricular assist device implantation. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S52-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Madesis A, Tsakiridis K, Zarogoulidis P, et al. Review of mitral valve insufficiency: repair or replacement. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S39-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Siminelakis S, Kakourou A, Batistatou A, et al. Thirteen years follow-up of heart myxoma operated patients: what is the appropriate surgical technique? J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S32-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foroulis CN, Kleontas A, Karatzopoulos A, et al. Early reoperation performed for the management of complications in patients undergoing general thoracic surgical procedures. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S21-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nikolaos P, Vasilios L, Efstratios K, et al. Therapeutic modalities for Pancoast tumors. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S180-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bavnbek K, Ahsan SY, Sanders J, et al. Wound management and restrictive arm movement following cardiac device implantation - evidence for practice? Eur J Cardiovasc Nurs 2010;9:85-91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Spyratos D, Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, et al. Preoperative evaluation for lung cancer resection. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S162-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Porpodis K, Zarogoulidis P, Spyratos D, et al. Pneumothorax and asthma. J Thorac Dis 2014;6:S152-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Panagopoulos N, Leivaditis V, Koletsis E, et al. Pancoast tumors: characteristics and preoperative assessment. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S108-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Visouli AN, Darwiche K, Mpakas A, et al. Catamenial pneumothorax: a rare entity? Report of 5 cases and review of the literature. J Thorac Dis 2012;4Suppl 1:17-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zarogoulidis P, Chatzaki E, Hohenforst-Schmidt W, et al. Management of malignant pleural effusion by suicide gene therapy in advanced stage lung cancer: a case series and literature review. Cancer Gene Ther 2012;19:593-600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Papaioannou M, Pitsiou G, Manika K, et al. COPD Assessment Test: A Simple Tool to Evaluate Disease Severity and Response to Treatment. COPD 2014;11:489-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Boskovic T, Stanic J, Pena-Karan S, et al. Pneumothorax after transthoracic needle biopsy of lung lesions under CT guidance. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S99-107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Papaiwannou A, Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, et al. Asthma-chronic obstructive pulmonary disease overlap syndrome (ACOS): current literature review. J Thorac Dis 2014;6Suppl 1:S146-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zarogoulidis P, Porpodis K, Kioumis I, et al. Experimentation with inhaled bronchodilators and corticosteroids. Int J Pharm 2014;461:411-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bai C, Huang H, Yao X, et al. Application of flexible bronchoscopy in inhalation lung injury. Diagnostic Pathology 2013;8:174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zarogoulidis P, Kioumis I, Porpodis K, et al. Clinical experimentation with aerosol antibiotics: current and future methods of administration. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013;7:1115-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zarogoulidis P, Pataka A, Terzi E, et al. Intensive care unit and lung cancer: when should we intubate? J Thorac Dis 2013;5Suppl 4:S407-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hohenforst-Schmidt W, Petermann A, Visouli A, et al. Successful application of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation due to pulmonary hemorrhage secondary to granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Drug Des Devel Ther 2013;7:627-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zarogoulidis P, Kontakiotis T, Tsakiridis K, et al. Difficult airway and difficult intubation in postintubation tracheal stenosis: a case report and literature review. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2012;8:279-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]