Abstract

Previous studies have reported that the Asp1104His polymorphism in Xeroderma Pigmentosum complementation group G (XPG) was associated with the susceptibility to colorectal cancer (CRC), although the results were inconsistent. This study was aim to investigate whether there existed an association between XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and CRC risk in the Chinese population, and a further meta-analysis was performed to consolidate the results. We found that XPG Asp1104His polymorphism was associated with a significantly increased CRC risk (dominant model: His/His + Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp, adjusted OR = 1.39, 95% CI = 1.14–1.69). Stratification analysis by clinical characteristics indicated that the His/His + Asp/His genotypes were associated with increased CRC susceptibility in patients with moderately differentiated grade, but not in poorly and well differentiated grade. Furthermore, a total of 5 eligible studies, including 2,649 CRC cases and 2,848 controls, were recruited for the meta-analysis. We identified that the meta-analysis reported a similar result in dominant model (OR = 1.35; 95% CI = 1.20–1.51). Especially, when stratified by ethnicity, an evidently increased risk was identified in the Asian population. In conclusion, our findings suggest that XPG Asp1104His polymorphism may increase the susceptibility of CRC, especially in Asian populations.

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in males and the second in females, with over 1.2 million new cases and 608,700 deaths estimated in every year1. The development of CRC has been demonstrated as a complex process caused by many factors, such as environmental and genetic mutation2. Many studies indicated that DNA damage was significantly associated with cancer development, which caused errors during DNA synthesis. Besides, it has reported that the DNA repair capacity was related to the inherited factors. Therefore, individuals with inherited impairment in DNA repair capacity are often associated with increased risk of cancers3.

Emerging evidence have demonstrated that the DNA damage repair can be activated by various pathways, including nucleotide excision repair (NER), base excision repair (BER), mismatch repair (MMR), double-strand break repair (DSBR), and direct repair (DR). Among these, the NER is mainly responsible for repairing bulky DNA damage, such as DNA adducts caused by UV radiation, mutagenic chemicals and chemotherapeutic drugs4. Besides, many key NER genes, such as ERCC1, XPA, XPB/ERCC3, XPC, XPD/ERCC2, XPE/DDB1, XPF/ERCC4, and XPG/ERCC5, have been identified, which play vital roles in DNA damage repairing and maintaining genome integrity.

Xeroderma Pigmentosum complementation group G (XPG), also named ERCC5, is located on chromosome 13q22-q33, consisting of 15 exons and 14 introns5. XPG is a member of the flap structure-specific endonuclease 1 (FEN1) family and encodes a protein of 1186 amino acids. It has reported that a defective XPG plays a pivotal role in the initiation of carcinogenesis and leads to DNA repair defects, genomic instability, and failure of gene transcription modulation6,7,8. To date, at least six single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in XPG gene have been identified, and the common Asp1104His polymorphism (rs17655 G/C, minor allele frequency > = 0.444, CHB in HapMap), regarded as a tagSNP, was widely investigated for its relationship to the risk of different cancers9. Recently, some studies have reported that Asp1104His polymorphisms in XPG were associated with risk of CRC; but, the results remained inconsistent. Thus, we genotyped the XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and evaluated its association with CRC susceptibility in an independent Chinese population.

Results

Study Characteristics

A total of 878 CRC cases and 884 healthy controls were recruited in our analysis, and the characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Except that more individuals with family history of cancer were in cases than that in controls (23.5% in CRC cases; 9.8% in controls, P < 0.001), there were no significant difference in distributions of age, sex, smoking status and drinking status (P = 0.632, 0.125, 0.187 and 0.222, respectively). Among the CRCs, 52.3% of patients suffered from colon cancer, and 47.7% from rectum cancer. Moreover, 7.1%, 77.1%, and 15.8% of cases were classified as poor, moderate and well differentiation grade, respectively. The Dukes A, B, C, and D stages were 7.0%, 44.6%, 36.6%, and 11.8%, respectively. The genotype distributions of the XPG polymorphism between the cases and controls are listed in Table 2. The genotype frequencies of XPG Asp1104His polymorphism were 32.6% (Asp/Asp), 52.3% (Asp/His) and 15.1% (His/His) in the cases, which were significantly different from those in the controls (40.2%, 45.8%, 14.0%). Besides, the XPG C (His) allele frequency was 52.6% among the cases, while 47.4% among the controls, indicating a significantly statistically difference (P = 0.008). The observed genotype frequencies among the controls were in agreement with the HWE (P = 0.622). Furthermore, the MAF of XPG Asp1104His is 0.369 in the controls, which was about the same as that in HapMap-CHB database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov).

Table 1. Distribution of selected variables between colorectal cancer cases and controls.

| Cases (n = 878) | Controls (n = 884) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| variables | n | % | n | % | Chi-square P -value |

| Age (mean+SD) | 60.0 ± 12.9 | 60.3 ± 13.7 | 0.632 | ||

| Sex | 0.125 | ||||

| Male | 541 | 61.6 | 513 | 58.0 | |

| Female | 337 | 38.4 | 371 | 42.0 | |

| Smoking status | 0.187 | ||||

| Never | 580 | 66.1 | 610 | 69.0 | |

| Ever | 298 | 33.9 | 274 | 31.0 | |

| Drinking status | 0.222 | ||||

| Never | 636 | 72.4 | 663 | 75.0 | |

| Ever | 242 | 27.6 | 221 | 25.0 | |

| Family history of cancer | <0.001 | ||||

| No | 672 | 76.5 | 797 | 90.2 | |

| Yes | 206 | 23.5 | 87 | 9.8 | |

| Tumor site | |||||

| Colon | 459 | 52.3 | |||

| Rectum | 419 | 47.7 | |||

| Tumor grade | |||||

| Low | 62 | 7.1 | |||

| Intermediate | 677 | 77.1 | |||

| High | 139 | 15.8 | |||

| Dukes stage | |||||

| A | 61 | 7.0 | |||

| B | 392 | 44.6 | |||

| C | 321 | 36.6 | |||

| D | 104 | 11.8 | |||

SD: standard deviation.

Table 2. Distribution of genotypes of XPG Asp1104His and their associations with risk of colorectal cancer.

| Gentypes | Cases(n = 878) n/% | controls(n = 884) n/% | Crude OR(95%CI) | Adjusted OR(95%CI)* | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp/Asp | 286 | 32.6 | 355 | 40.2 | 1.00(reference) | 1.00(reference) | |

| Asp/His | 459 | 52.3 | 405 | 45.8 | 1.41(1.15–1.73) | 1.41(1.15–1.74) | 0.001 |

| His/His | 133 | 15.1 | 124 | 14.0 | 1.33(1.00–1.78) | 1.34(1.00–1.79) | 0.048 |

| His/His +Asp/His | 592 | 67.4 | 529 | 59.8 | 1.39(1.14–1.69) | 1.40(1.15–1.70) | <0.001 |

| His allele | 725 | 52.6 | 653 | 47.4 | 1.20(1.05–1.37) | 0.008 | |

*Adjusted for age, sex, and smoking and drinking status in logistic regression model.

Effects in association between XPG Asp1104His and CRC risk

We adjusted age, sex, smoking status, and drinking status for multivariate logistic regression analysis, revealing that the individuals with the His/His or Asp/His had a significantly increased risk of CRC (His/His vs Asp/Asp, adjusted OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 1.06–1.11; Asp/His vs Asp/Asp, adjusted OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.15–1.74), compared with the Asp/Asp genotype; besides, the His/His + Asp/His genotypes were related to higher CRC susceptibility (adjusted OR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.15–1.70). In the stratification analyses on the dominant model, as shown in Table 3, the His/His + Asp/His genotypes were associated with an increased risk of CRC in every subgroup except for the female. Moreover, the relationships of XPG Asp1104His polymorphism to the clinicopathological characteristics were also evaluated (Table 4). The risk effect of His/His + Asp/His genotypes was found in each group of tumor site and Dukes stage (all P < 0.05); however, only in the subgroup of moderately differentiated grade, we identified a significant increased risk (adjusted OR = 1.44, 95% CI = 1.17–1.78), but not in the subgroup of poorly and well differentiated grade (OR = 1.20, CI = 0.70–2.06; OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 0.87–1.85).

Table 3. Association between XPG Asp1104His Genotypes and demographic characteristics.

| Genotypes | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asp/Asp | His/His + Asp/His | ||||||

| Variables | n(cases/controls) | % | n(cases/controls) | % | P | Adjusted* OR(95% CI) | P for interaction |

| Total | 286/355 | 32.6/40.2 | 592/529 | 67.4/59.8 | <0.001 | 1.40 (1.15–1.70) | |

| Age | |||||||

| ≤60 | 142/172 | 32.3/42.9 | 298/229 | 67.7/57.1 | 0.002 | 1.57 (1.18–2.09) | |

| >60 | 144/183 | 32.9/37.9 | 294/300 | 67.1/62.1 | 0.05 | 1.31 (1.00–1.74) | |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 178/218 | 32.9/42.5 | 363/295 | 67.1/57.5 | 0.001 | 1.52 (1.18–1.96) | |

| Female | 108/137 | 32.1/37.0 | 229/234 | 67.9/63.0 | 0.111 | 1.30 (0.94–1.79) | |

| Smoking status | |||||||

| Never | 194/237 | 33.5/38.9 | 386/378 | 66.5/61.1 | 0.041 | 1.28 (1.01–1.63) | 0.172 |

| Ever | 92/118 | 30.9/43.1 | 206/156 | 69.1/56.9 | 0.002 | 1.72 (1.21–2.43) | |

| Drinking status | |||||||

| Never | 209/260 | 32.9/39.2 | 427/403 | 67.1/60.8 | 0.014 | 1.33 (1.06–1.68) | 0.367 |

| Ever | 77/95 | 31.8/43.0 | 165/126 | 68.2/57.0 | 0.016 | 1.62 (1.10–2.40) | |

| family history of cancer | |||||||

| No | 222/316 | 33.0/39.7 | 450/481 | 67.0/60.3 | 0.007 | 1.35 (1.09–1.67) | 0.330 |

| Yes | 39/64 | 31.1/44.8 | 142/48 | 68.9/55.2 | 0.028 | 1.81 (1.07–3.07) | |

CI confidence interval, OR odds ratio.

*Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, and drinking status in logistic regression model.

Table 4. Association between XPG Asp1104His Genotypes and Clinical Characteristics of Colorectal Cancer.

| Asp/Asp | His/His+Asp/His | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | n/% | n/% | Crude OR(95%CI) | Adjusted *OR(95% CI) | P |

| Controls(n = 884) | 355/40.2 | 529/59.8 | 1.00 (reference) | 1.00 (reference) | |

| Cases(n = 878) | 286/32.6 | 592/67.4 | 1.39 (1.14–1.69) | 1.40 (1.15–1.70) | <0.001 |

| Tumor site | |||||

| Colon | 144/31.4 | 315/68.6 | 1.47 (1.16–1.86) | 1.48 (1.16–1.87) | 0.001 |

| Rectum | 142/33.9 | 277/66.1 | 1.31 (1.03–1.67) | 1.32 (1.03–1.69) | 0.026 |

| Tumor grade | |||||

| Low | 22/35.5 | 40/64.5 | 1.22 (0.71–2.09) | 1.20 (0.70–2.06) | 0.507 |

| Intermediate | 216/31.9 | 461/68.1 | 1.43 (1.16–1.77) | 1.44 (1.17–1.78) | <0.001 |

| High | 48/34.5 | 91/65.5 | 1.27 (0.88–1.85) | 1.27 (0.87–1.85) | 0.216 |

| Dukes stage | |||||

| A+B | 144/31.8 | 309/68.2 | 1.44 (1.13–1.83) | 1.15 (1.14–1.84) | 0.002 |

| C+D | 142/33.4 | 283/66.6 | 1.34 (1.05–1.70) | 1.35 (1.06–1.72) | 0.017 |

*Adjusted for age, sex, smoking, and drinking status in logistic regression model.

The results of meta-analysis

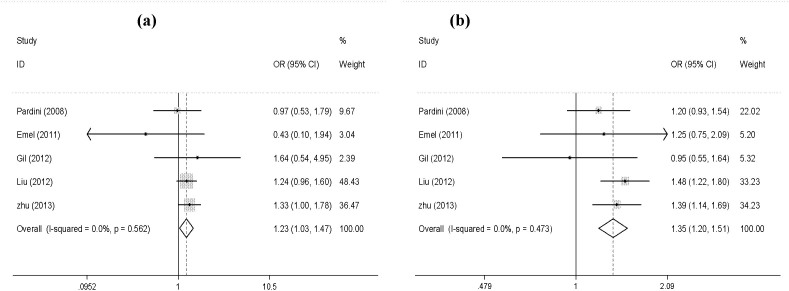

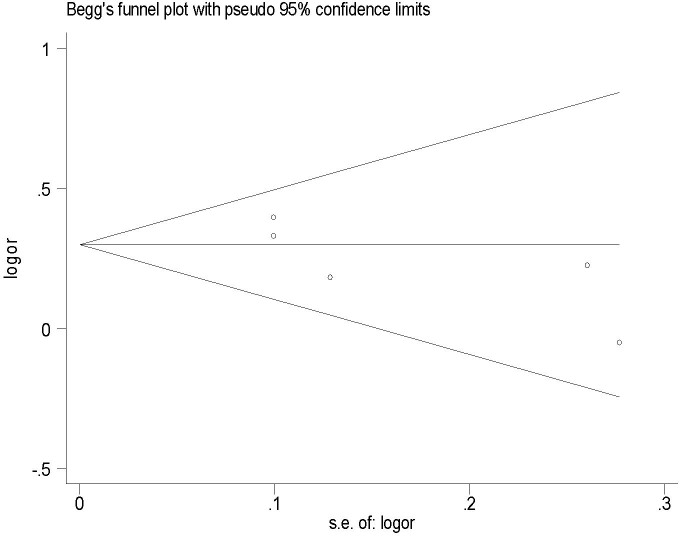

A total of five eligible studies2,10,11,12, including 2649 cases and 2848 controls were recruited for meta-analysis (Table S1). We observed a significant association between XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and CRC risk under homozygote comparison (His/His vs. Asp/Asp: OR = 1.24; 95% CI: 1.03–1.47; P = 0.02; Figure 1a), and dominant model (His/His + Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp: OR = 1.35; 95% CI: 1.20–1.51; P < 0.001; Figure 1b). When stratified by ethnicity, an evidently increased risk was identified in the Asian populations: His/His vs. Asp/Asp: OR = 1.28; 95% CI: 1.05–1.55; P = 0.012 (Figure S1a); Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp: OR = 1.49; 95%CI:1.29–1.73; P < 0.001 (Figure S1b); His/His + Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp: OR = 1.44; 95% CI: 1.25–1.65; P < 0.001 (Figure S1c). No heterogeneities were observed in our meta-analysis (all P > 0.1; Table 5). We used the Begg's rank correlation method and Egger's weighted regression method to assess publication bias. Fortunately, there was no obvious publication bias in this meta-analysis (His/His vs. Asp/Asp: Begg's test P = 0.327, Egger's test P = 0.326, t = −1.17, 95% CI = −3.020–1.394; His/His + Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp: Begg's test P = 0.142, Egger's test P = 0.139, t = −2.01, 95% CI = −4.394–0.997) (Figure 2).

Figure 1. The association between XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and colorectal cancer under: (a) homozygote comparison (His/His vs. Asp/Asp); (b) dominant model (His/His + Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp).

Table 5. Meta-analysis of the association between the XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and colorectal cancer risk.

| His/His vs. Asp/Asp | Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp | His/His + Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp | His/His vs. Asp/His + Asp/Asp | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stratification | No. case/control | OR (95%CI) | P/Phe | OR (95%CI) | P/Phe | OR (95%CI) | P/Phe | OR (95%CI) | P/Phe |

| Total | 2649/2848 | 1.24(1.03–1.47) | 0.020/0.562 | 0.85(0.69–1.05) | 0.127/0.303 | 1.35(1.20–1.5) | 0/0.473 | 0.97(0.83–1.14) | 0.750/0.430 |

| Ethnicity | |||||||||

| Asian | 1906/1969 | 1.28(1.05,1.55) | 0.012/0.473 | 1.49(1.29,1.73) | 0/0.418 | 1.44(1.25,1.65) | 0/0.636 | 0.98(0.83,1.16) | 0.285/0.797 |

| Caucasian | 743/879 | 0.97(0.59,1.58) | 0.900/0.372 | 1.19(0.96,1.48) | 0.109/0.397 | 1.16(0.94,1.44) | 0.147/0.718 | 0.92(0.57,1.48) | 0.720/0.262 |

Figure 2. Funnel plot of publication bias for XPG Asp1104His polymorphisms with CRC risk (based on a dominant model).

Discussion

In the NER pathway, XPG cleaves the damaged DNA 3′ to the damaged site, nonenzymatically participates in the 5′ incision and stabilizes the DNA repair complex to the damaged DNA13. The SNPs in the coding region of the EECC5/XPG gene may result in a subtle alteration of the ERCC5/XPG activity and modulation of cancer susceptibility14. Berhane N et al. indicated that an amino acid changing from an acidic aspartic acid residue to a basic histidine residue could affect the protein structure of XPG, and thus influence the protein–protein interactions and the stability of the preincision complex XPG C-terminus15. To date, it has been proven that XPG SNPs were associated with some cancers, such as lung cancer16 and breast cancer17. These implied a certain link between the XPG polymorphisms and the development of certain cancers.

The association between CRC and XPG Asp1104His polymorphism has been widely studied2,10,18. Liu et al. have suggested that the XPG Asp1104His polymorphism contributed to the increased risk for CRC and also was associated with shorter PFS for the CRC patients receiving oxaliplatin-based chemotherapy10. However, Mort R et al. reported that XPG Asp1104His were not associated with CRC risk19. In addition, no previous studies examined the association between the XPG Asp1104His SNP and the risk of CRC with demographic characteristics and clinic pathological parameters. Thus, we conducted a hospital-based case-control study and meta-analysis to comprehensively evaluate the association of the Asp1104His polymorphisms with CRC.

In this study, we investigated the association between the XPG Asp1104His and CRC susceptibility. Our findings showed a significant increased frequency of the variant allele in cases (C-allele 0.526) compared to controls (C-allele 0.474). We found that the XPG Asp1104His was related to an increased the risk of CRC in codominant and dominant model, as Liu et al.9 reported. In subgroup analysis, the male in the dominant model of XPG Asp1104His seemed to be more susceptible to CRC, but not the female (Table 3). The reason might be that women have relatively healthy living habits and particular physiological mechanisms, which protect them from CRC. Furthermore, in the subgroup of clinicopathology characteristics, we observed that the Asp/His+His/His genotype were associated with a significantly increased risk of intermediate grade CRC, but not the low and high grade CRC. This phenomenon may be due to the relatively small number of patients with low and high grade CRC; and in the subgroups of tumor location and tumor stage, the associations remained still. These results suggested that XPG Asp1104His polymorphism could help to diagnose CRC. As the cancer stage was correlated to prognosis, we inferred that the XPG Asp1104His polymorphism did not predict the progression of CRC based on our results.

Furthermore, our meta-analysis revealed that individuals with His/His and His/His+Asp/His genotype were more likely to susceptible to CRC, which was similar to the result of our study. In the subgroup of ethnicity, we found that the XPG His/His and Asp/His genotypes seemed to be more susceptible to CRC in Asians, but not in European. This might be account for ethnic differences and diverse live environment. In addition, it was also likely that the observed ethnic differences may be due to chance because studies with small sample size may have insufficient statistical power to detect a slight effect20.

Some limitations should be noted when interpreting our findings. Firstly, many exposure variables were not taken into account, such as diet in general, history of other cancer and chronic diseases, which may affect the reliability of the results. Thus, more comprehensive studies are needed to validate these findings. Secondly, the sample sizes in our case-control study and meta-analysis study both are relatively small and might not provide sufficient power to assess the association between XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and CRC risk. Thirdly, our study population only included the Chinese; studies with ethnically diverse populations are warranted.

In conclusion, our study showed that the XPG Asp1104His polymorphism appeared to confer susceptibility to CRC. Further well-designed studies with larger sample sizes will be needed to confirm the impact of XPG Asp1104His polymorphism on CRC susceptibility.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the institutional review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University. The informed written consent was obtained from all subjects. In addition, the methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines. And, all experimental protocol was approved by the institutional review board of the First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University.

Study population

We recruited CRC (CRC) cases and healthy controls from September 2010 to October 2013. Patients without restriction on age and sex were consecutively recruited at The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University, Nanjing, China. All of the cases were pathologically or histologically confirmed. The pathological stage of CRC at the time of diagnosis was classified into Dukes A, B, C, and D. Tumor grade was classified into well differentiated, moderately differentiated and poorly differentiated. Controls were randomly selected from a healthy screening campaign in the same region. The selection criteria for controls included cancer-free individuals and frequency matched to cases for sex and age. All of the participants were interviewed with a self-administered questionnaire after obtaining a written informed consent. After interview, about 5 ml of venous blood sample was collected from each subject.

Genotyping

Genomic DNA isolated from 5 ml whole blood was used to genotype XPG Asp1104His by using the TaqMan assay (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of primer and probe for each SNP are available on request. Genomic DNA of 50 ng and 0.56 mix (TaKaRa Bio, JPN) was used for each reaction and amplification was performed under the following conditions: 50°C for 2 min, 95°C for 10 min followed by 45 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec, and 60°C for 1 min. We assessed genotype data quality by typing 10% blinded replicate samples and the concordance rate was 100.0%.

Statistical analysis

For the case-control study, the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) for genotype distribution in controls was tested by a goodness-of-fit x2 test. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to evaluate association between the genotypes and risk of CRC according to the significant genetic models by univariate and multivariate unconditional logistic regression models, respectively. P <0.05 was considered as statistically significant, and all statistical tests were two sided. Statistical analyses were done using SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Meta-analysis

Eligibility of relevant studies

To further confirm the relationship between XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and CRC, we carried out a meta-analysis. The PubMed database was searched with terms “XPG”, “ERCC5”, “viceversa Xeroderma Pigmentosum group G”, “excision repair cross-complementing group 5″, “polymorphism”, “colorectal cancer”, as well as their combinations for all genetic studies on the relationship between XPG polymorphism and CRC risk up to March 2014. We also searched references in published articles and reviews on this topic in PubMed. Eligible studies had to meet the following criteria: (a) only case-control design; (b) studies exploring the correlation between CRC and XPG Asp1104His polymorphism. A total of 5 potential relevant studies (including our study) were retrieved through PubMed2,10,11,12.

Data extraction

Two investigators find the publications on the topic and then a selection of the detected studies independently according to the inclusion criteria listed above. Then, the following information was collected from each study: first author's name, year of publication, study design, ethnicity and numbers of cases and controls with the XPG Asp1104His genotypes, respectively (Table S1).

Statistical analysis

The chi-square based Q-test was used to evaluate the heterogeneity. The pooled OR was assessed in the fixed-effects model by Mantel–Haenszel method when P >0.05. Otherwise, the random-effects model by DerSimonian and Laird method was used21. The modified Egger's linear regression test was used to detect the potential publication bias. Crude ORs and 95% CIs were used to assess the intensity of the correlation between XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and CRC risk. The pooled ORs were evaluated on co-dominant model (His/Asp vs. Asp/Asp, His/His vs. Asp/Asp), dominant model (His/His + Asp/His vs. Asp/Asp, recessive model (His/His vs. Asp/His + Asp/Asp) and allele (His vs. Asp), respectively. Statistical analyses were used by STATA version 11.0 (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX, USA).

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: H.D., X.Z. and M.D. Performed the experiments: N.G. and M.D. Analyzed the data: H.D., Z.C. and M.W. Contributed analysis tools: Y.S., Z.Z., L.Z. and M.W. Wrote the main manuscript: H.D., X.Z. and M.D. Reference collection and data management: H.D., X.Z., M.D and N.G. Statistical analyses: H.D. and X.Z.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This study was partially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81472634), Health Department guidance project of Jiangsu Province (Z201201), the Program for Development of Innovative Research Team in the First Affiliated Hospital of NJMU and the Project Funded by the Priority Academic Program Development of Jiangsu Higher Education Institutions (JX10231801), the Jiangsu Province Clinical science and technology projects (Clinical Research Center, BL2012008) and the Summit of the Six Top Talents Program of Jiangsu Province (2013-WSN-034).

References

- Jemal A. et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 61, 69–90, 10.3322/caac.20107 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canbay E. et al. Association of APE1 and hOGG1 polymorphisms with colorectal cancer risk in a Turkish population. Curr Med Res Opin 27, 1295–1302, 10.1185/03007995.2011.573544 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein C., Bernstein H., Payne C. M. & Garewal H. DNA repair/pro-apoptotic dual-role proteins in five major DNA repair pathways: fail-safe protection against carcinogenesis. Mutat Res 511, 145–178 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leibeling D., Laspe P. & Emmert S. Nucleotide excision repair and cancer. J Mol Histol 37, 225–238, 10.1007/s10735-006-9041-x (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emmert S., Schneider T. D., Khan S. G. & Kraemer K. H. The human XPG gene: gene architecture, alternative splicing and single nucleotide polymorphisms. Nucleic Acids Res 29, 1443–1452 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koeppel F. et al. Irofulven cytotoxicity depends on transcription-coupled nucleotide excision repair and is correlated with XPG expression in solid tumor cells. Clin Cancer Res 10, 5604–5613, 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0442 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L., Sturgis E. M., Eicher S. A., Spitz M. R. & Wei Q. Expression of nucleotide excision repair genes and the risk for squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer 94, 393–397, 10.1002/cncr.10231 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci R. et al. XPG mRNA expression levels modulate prognosis in resected non-small-cell lung cancer in conjunction with BRCA1 and ERCC1 expression. Clin Lung Cancer 10, 47–52, 10.3816/CLC.2009.n.007 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu C., Yin Q., Hu J., Weng J. & Wang Y. Quantitative assessment of the association between XPG Asp1104His polymorphism and bladder cancer risk. Tumour Biol 35, 1203–1209, 10.1007/s13277-013-1161-9 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D. et al. DNA repair genes XPC, XPG polymorphisms: relation to the risk of colorectal carcinoma and therapeutic outcome with Oxaliplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. Mol Carcinog 51 Suppl 1, E83–93, 10.1002/mc.21862 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardini B. et al. DNA repair genetic polymorphisms and risk of colorectal cancer in the Czech Republic. Mutat Res 638, 146–153, 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.09.008 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil J. et al. The C/A polymorphism in intron 11 of the XPC gene plays a crucial role in the modulation of an individual's susceptibility to sporadic colorectal cancer. Mol Biol Rep 39, 527–534, 10.1007/s11033-011-0767-5 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. L. et al. The association of XPG and MMS19L polymorphisms response to chemotherapy in osteosarcoma. Pak J Med Sci 29, 1225–1229 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiyohara C. & Yoshimasu K. Genetic polymorphisms in the nucleotide excision repair pathway and lung cancer risk: a meta-analysis. Int J Med Sci 4, 59–71 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhane N., Sobti R. C. & Mahdi S. A. DNA repair genes polymorphism (XPG and XRCC1) and association of prostate cancer in a north Indian population. Mol Biol Rep 39, 2471–2479, 10.1007/s11033-011-0998-5 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuli Y. et al. XPG is a novel biomarker of clinical outcome in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Pak J Med Sci 29, 762–767 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng Q., Lao X., Li R., Qin X. & Li S. Methodological remarks concerning a recent meta-analysis on XPG Asp1104His and XPF Arg415Gln polymorphisms and breast cancer risk. Breast Cancer Res Treat 139, 617–618, 10.1007/s10549-013-2526-x (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi A. D. et al. Red meat and poultry intake, polymorphisms in the nucleotide excision repair and mismatch repair pathways and colorectal cancer risk. Carcinogenesis 30, 472–479, 10.1093/carcin/bgn260 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mort R., Mo L. & McEwan C. et al. Lack of involvement of nucleotide excision repair gene polymorphisms in colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 89, 333–7 (2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Wacholder S., Chanock S., Garcia-Closas M., El Ghormli L. & Rothman N. Assessing the probability that a positive report is false: an approach for molecular epidemiology studies. J Natl Cancer Inst 96, 434–442 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantel N. & Haenszel W. Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. J Natl Cancer Inst 22, 719–748 (1959). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Information