Abstract

Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) are members of a family of tetrameric intracellular Ca2+-release channels (CRCs). While it is well known in mammals that RyRs and IP3Rs modulate multiple physiological processes, the roles of these two CRCs in the development and physiology of insects remain poorly understood. In this study, we cloned and functionally characterized RyR and IP3R cDNAs (named TcRyR and TcIP3R) from the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. The composite TcRyR gene contains an ORF of 15,285 bp encoding a protein of 5,094 amino acid residues. The TcIP3R contains an 8,175 bp ORF encoding a protein of 2,724 amino acids. Expression analysis of TcRyR and TcIP3R revealed significant differences in mRNA expression levels among T. castaneum during different developmental stages. When the transcript levels of TcRyR were suppressed by RNA interference (RNAi), an abnormal folding of the adult hind wings was observed, while the RNAi-mediated knockdown of TcIP3R resulted in defective larval–pupal and pupal–adult metamorphosis. These results suggested that TcRyR is required for muscle excitation-contraction (E-C) coupling in T. castaneum, and that calcium release via IP3R might play an important role in regulating ecdysone synthesis and release during molting and metamorphosis in insects.

Calcium (Ca2+) is a key second messenger that plays important physiological roles in various cells. There are two main Ca2+ mobilizing systems in eukaryotic organisms including Ca2+ influx through the plasma membrane and Ca2+ release from internal stores. Ryanodine receptors (RyRs) and inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors (IP3Rs) are large tetrameric intracellular Ca2+-release channels (CRCs) located in the endo/sarcoplasmic reticulum (ER/SR) of cells. An increasing number of both RyR and IP3R functional genes have been identified in a variety of multicellular eukaryotes ranging from Caenorhabditis elegans to humans1, and recently, putative RyR/IP3R homologs have also been identified in unicellular organisms2,3. In mammals, three isoforms of RyRs (RyR1, RyR2 and RyR3) and IP3Rs (IP3R1, IP3R2 and IP3R3) have been identified, which are encoded by separate genes and show distinct cellular distribution patterns. While the IP3Rs are approximately half the size of the RyRs, these two receptors show similarities in their regulation, and a recent study indicated that RyRs and IP3Rs have co-evolved from an ancestral unicellular RyR/IP3R1.

In contrast to mammals, only one of each RyR (DmRyR) and IP3R (DmIP3R) gene was identified in Drosophila melanogaster4,5,6, which showed approximately 45% and 60% amino acid identity with the three mammalian RyRs and IP3Rs, respectively. Compared with IP3Rs, insect RyRs have attracted increasing attention due to the discovery of diamide insecticides including the compounds flubendiamide, chlorantraniliprole (RynaxypyrTM) and cyantraniliprole (Cyazypyr™)7,8. Functional expression studies of the recombinant silkworm RyR (sRyR) in HEK293 cells have suggested that the insecticide flubendiamide is mainly incorporated into the transmembrane domains (residues 4111-5084) of sRyR9. Recently, a short segment of the C-terminus transmembrane region of DmRyR (residues 4610-4655) was found to be critical to diamide insecticide sensitivity10. Additionally, it was reported that high levels of diamide cross-resistance in Plutella xylostella are associated with a target-site mutation (G4946E) in the COOH-terminal membrane-spanning domain of the RyR11. Beyond the recent characterization of RyRs in moths and fruit flies, little molecular characterization of insect IP3Rs has been performed.

It is well known in mammals that RyRs and IP3Rs modulate a wide variety of Ca2+-dependent physiological processes1,12. However, information about the physiological processes affected by their function in insects is still limited. In the present study, we cloned RyR and IP3R cDNAs (named as TcRyR and TcIP3R) from the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. We report the expression patterns of the TcRyR and TcIP3R transcripts. We also explored the roles of these two CRC genes in the development and physiology of T. castaneum by in vivo RNA interference (RNAi).

Results

cDNA Cloning and characterization of TcRyR and TcIP3R in Tribolium castaneum

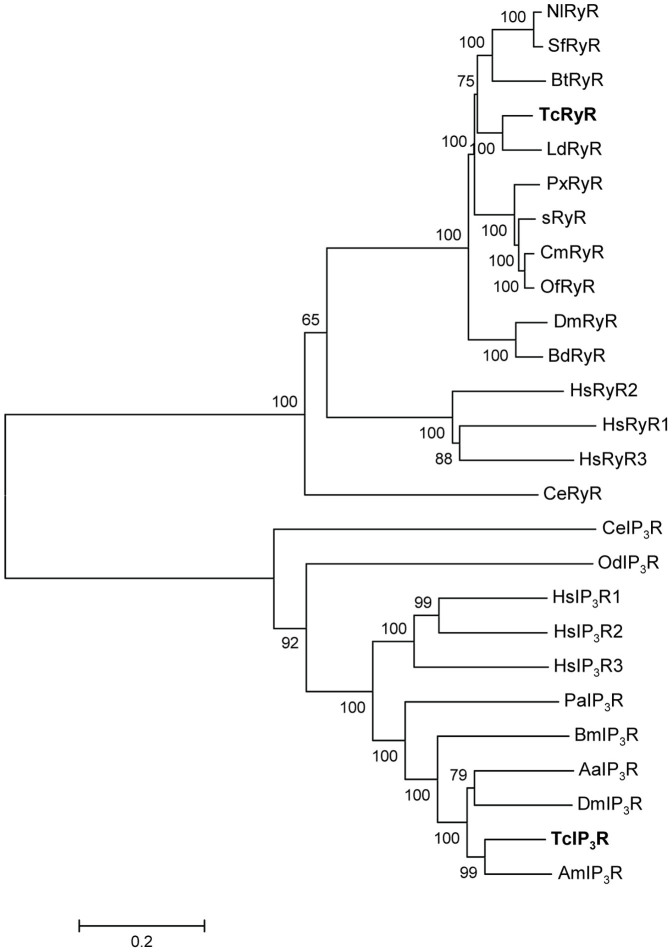

RT-PCR was used to amplify the entire coding sequences of the RyR and IP3R cDNAs from T. castaneum. A total of 12 and 6 overlapping cDNA fragments were obtained for TcRyR and TcIP3R, respectively (Table 1). Compilation of the cDNA clones resulted in a 15,308 bp contiguous sequence containing a 15,285 bp ORF for TcRyR and an 8,231 bp contiguous sequence containing an 8,175 bp ORF for TcIP3R. Amino acid sequence alignments showed that the encoded 5,094 amino acid residues of TcRyR and 2,724 amino acid residues of TcIP3R share 78% and 70% overall amino acid identity with the D. melanogaster DmRyR and DmIP3R, respectively. The overall amino acid identities of TcRyR with its human homologues, HsRyR1, HsRyR2 and HsRyR3, were 44%, 46% and 44%, respectively, while identities of TcIP3R with human homologues HsIP3R1, HsIP3R2 and HsIP3R3 were 61%, 58% and 53%, respectively. Phylogenetic analyses were consistent with these proteins representing RyR and IP3R homologues, respectively (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Oligonucleotide primers used for RT-PCR and RT-qPCR.

| primer | Sequence (5′ to 3′) | Description (cDNA position) |

|---|---|---|

| 617.TcRyRF1 | AGAATGGCGGAGGCCGAAG | RyR RT-PCR product P1(1-1208) |

| 618.TcRyRR1 | ACTCTCGCAGTTCTGGATTC | |

| 619.TcRyRF2 | GACTTCAGTAGGAGTCAAGA | RyR RT-PCR product P2(1165-2569) |

| 620.TcRyRR2 | TGGAAGTGTCTACAGGGTTT | |

| 621.TcRyRF3 | GAAAGCCTCCTCCCGCAACA | RyR RT-PCR product P3(2434-2855) |

| 622.TcRyRR3 | ATTCGCCTTCTCCATAGTCT | |

| 623.TcRyRF4 | GGTTCAGACAGTCCTCCGTG | RyR RT-PCR product P4(2790-5356) |

| 624.TcRyRR4 | AGGCGGCATAAAGAGTCAAA | |

| 625.TcRyRF5 | CGCTGTATTGATGTATTGGA | RyR RT-PCR product P5(5275-6654) |

| 626.TcRyRR5 | CCACATTTCGGCAACATCTT | |

| 627.TcRyRF6 | GTACAATTTCATAAACGCCG | RyR RT-PCR product P6(6381-8034) |

| 628.TcRyRR6 | TCGGTAGACTGTGTGTAAAG | |

| 629.TcRyRF7 | CACTCCTCATCCAACACAGC | RyR RT-PCR product P7(7949-9416) |

| 630.TcRyRR7 | CAAAACAGGGAAGCCACCAT | |

| 656.TcRyRF12 | TTCATCCACCTTCAGTCGCA | RyR RT-PCR product P8(9222-11018) |

| 657.TcRyRR12 | TGCCAAGACATTTCGTCAGC | |

| 633.TcRyRF9 | GTTTTGATAATGCCCACAGC | RyR RT-PCR product P9(10702-12302) |

| 634.TcRyRR9 | AAACCTCCAACAGCGTCCCA | |

| 635.TcRyRF10 | GCTATCGGTGTTGCTAGTCA | RyR RT-PCR product P10(12187-13847) |

| 636.TcRyRR10 | GCACGATGACTGTAAGCACC | |

| 637.TcRyRF11 | AACCTGTTGTTACTGAACCT | RyR RT-PCR product P11(13784-15115) |

| 638.TcRyRR11 | AGTTGTGCTCTTGTTGGACG | |

| 682.TcRyRF13 | CATCGTTATTCTTCTGGCTA | RyR RT-PCR product P12(14934-15308) |

| 683.TcRyRR13 | CTGAAAGTGAATAGGAAGTG | |

| 734.TcIP3RF1 | CTGAAAACGCTCCAAAAACC | IP3R RT-PCR product P1(1-1647) |

| 735.TcIP3RR1 | CGTGTCTTGGGTCGTTCAGT | |

| 736.TcIP3RF2 | TTTGGACAACAACGGGGACG | IP3R RT-PCR product P2(1586-3158) |

| 737.TcIP3RR2 | AAAAATGCCCTCAGCTTGAC | |

| 738.TcIP3RF3 | TACCCGCTCGTCATGGATAC | IP3R RT-PCR product P3(2949-4296) |

| 739.TcIP3RR3 | ATGGCAGTAAACTATGACAC | |

| 740.TcIP3RF4 | AAGACACTGTATGGACGAGG | IP3R RT-PCR product P4(4175-5698) |

| 741.TcIP3RR4 | TCTTCTCTTAACTCGTCACT | |

| 742.TcIP3RF5 | CAAACAAGACGGGAAAGATT | IP3R RT-PCR product P5(5609-6999) |

| 743.TcIP3RR5 | TCCGTATGCCTGTCTCCCTA | |

| 744.TcIP3RF6 | CTCTTCTGGGTTAGTAGTTA | IP3R RT-PCR product P6(6795-8231) |

| 745.TcIP3RR6 | GACTAGGACAAGTTATCAAC | |

| 800.Tcrps3F1 | ACCGTCGTATTCGTGAATTGAC | RT-qPCR |

| 801.Tcrps3R1 | ACCTCGATACACCATAGCAAGC | |

| 806.TcRyRF | AAGGGGTATCCTGATTTGGG | RT-qPCR (7198-7400) |

| 807.TcRyRR | TTCGCATCTACGATAGCACG | |

| 808.TcIP3RF | GTGACTTGAGCCAGGCTTTC | RT-qPCR (5491-5621) |

| 809.TcIP3RR | CCCGTCTTGTTTGTCCTCAT |

Figure 1. Phylogenetic tree of the RyR and IP3R families.

A multiple alignment of TcRyR and TcIP3R amino acid sequences with representative RyR and IP3R isoforms was performed and used as the input for phylogenetic analysis. The Neighbor-joining tree was generated using MEGA5 with 1000 bootstrapping. RyR sequences are obtained from the following GenBank entries: DJ085056 for Bombyx mori (sRyR); AET09964 for Plutella xylostella (PxRyR); BAA41471 for Drosophila melanogaster (DmRyR); AFK84957 for Bemisia tabaci (BtRyR); JQ799046 for Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (CmRyR); AHW99829 for Sogatella furcifera (SfRyR); AHW99830 for Leptinotarsa decemlineata (LdRyR); AHY02115 for Bactrocera dorsalis (BdRyR); AGH68757 for Ostrinia furnacalis (OfRyR); KF306296 for Nilaparvata lugens (NlRyR); BAA08309 for Caenorhabditis elegans (CeRyR); NM_-000540 for Homo sapiens RyR1 (HsRyR1); NM_001035 for Homo sapiens RyR2 (HsRyR2); NM_001243996 for Homo sapiens RyR3 (HsRyR3). IP3R sequences are obtained from the following GenBank entries: AAN13240 for D. melanogaster (DmIP3R); EAT33105 for Aedes aegypti(AaIP3R); XP_004923625 for B. mori (BmIP3R); XP_006564780 for Apis mellifera (AmIP3R); CCD63765 for C. elegans (CeRyR); AAT47836 for Oikopleura dioica(OdIP3R); AAC61691 for Panulirus argus (PaIP3R); NP_001161744 for Homo sapiens IP3R1 (HsIP3R1); NP_002214 for Homo sapiens IP3R2 (HsIP3R2); NP_002215 for Homo sapiens IP3R3 (HsIP3R3).

The sequence alignments also revealed the conservation of critical amino acid residues within TcRyR and TcIP3R. For example, a glutamate residue proposed to be involved in the Ca2+ sensitivity of the rabbit RyR3 (E3885)13 and RyR1 (E4032)14 was detected in TcRyR (E4140). Additionally, residues corresponding to I4897, R4913, and D4917 of the rabbit RyR1, which were recently shown to play an important role in the activity and conductance of the Ca2+release channel15, were also conserved in TcRyR (I4950, R4966, D4970). Eleven amino acid residues known to be important for the strict recognition of IP3 within the IP3-binding core domain of the mouse IP3R116 were conserved in TcIP3R (R267, T268, T269, G270, R271, R496, K500, R503, Y560, R561, K562). Seven residues in the NH2-terminal suppression domain of the mouse IP3R1 critical for the suppression of IP3 binding17 were also found in TcIP3R (L31, L33, V34, D35, R37, R55, K128).

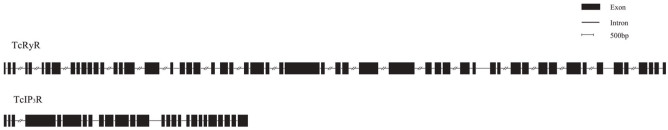

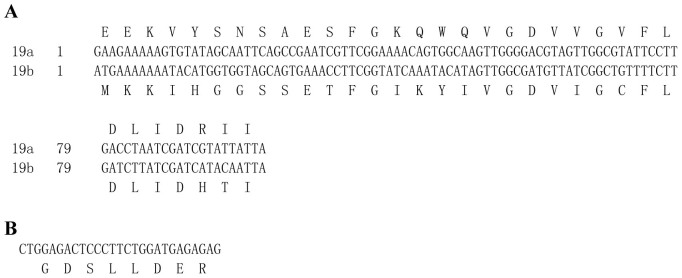

The genomic structures of TcRyR and TcIP3R were predicted by comparing the composite cDNA sequences with the genomic sequences retrieved from contigs in the whole genome shotgun release for T. castaneum18 (Fig. 2). The TcRyR comprises 55 exons ranging in size from 54 bp to 1462 bp including a pair of mutually exclusive exons (19a/19b, Fig. 3A), which were confirmed by multiple cDNA clone sequence alignment and were conserved in other insect RyRs6,19,20. The TcIP3R was split into 26 exons ranging in size from 71bp to 1269 bp. The 5′ donor and 3′ acceptor site sequences in both TcRyR and TcIP3R were in agreement with the GT/AG consensus sequence, except the 5′ donor sequence (GC) for intron 7 in TcRyR. Additionally, the alignment of multiple cDNA clone sequences also revealed one alternative splice site in TcIP3R, which is located between amino acid residues 922–929 and forms the optional exon encoding GDSLLDER (Fig. 3B). This alternative splice site was first reported in the insect IP3Rs, but it was conserved in the human IP3R121.

Figure 2. Schematic diagrams of the genomic organization for TcRyR and TcIP3R.

Figure 3. Nucleotide and inferred amino acid sequences of alternative exons in TcRyR and TcIP3R.

Conserved structural domains in TcRyR and TcIP3R

Similar to the mammalian RyR and IP3R proteins22, several structural domains common to both CRCs were identified including the suppressor-domain-like domain (SD), MIR (Mannosyltransferase, IP3R and RyR) domain, two RIH (RyR and IP3R Homology) domains, and an RIH–associated (RIHA) domain. The sequence identities between these common domains of TcRyR and TcIP3R range from 14.6% to 25.4% (Table 2). Additionally, six transmembrane helices (TM1 to TM6) were predicted in the COOH-terminal region of both TcRyR (4438–4460,4624–4646,4701–4723,4843–4865,4891–4913, 4971–4990) and TcIP3R (2266–2288, 2295–2317, 2343–2365,2386–2408, 2431–2453, 2546–2568). The GGGXGD motif between TM5 and TM6 that acts as the selectivity filter was also conserved in TcRyR (4947–4952) and TcIP3R (2521–2526). Like mammalian RyRs, three copies of a repeat termed SPRY (SPla and RyR) domain (659–795, 1084–1205, 1540–1680) and four copies of a repeat termed RyR domain(846–940, 959–1053, 2826–2919, 2942–3030) were also predicted in TcRyR.

Table 2. Percentage of amino acid sequence identity between the conserved domains of TcRyR and TcIP3R.

| SD | MIR | RIH | RIHA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TcRyR | 11-200 | 211-390 | 437-642/2218-2448 | 3979-4104 |

| TcIP3R | 5-228 | 236-424 | 463-667/1196-1376 | 1946-2061 |

| identity | 21.8 | 14.6 | 18.8/15.1 | 25.4 |

Developmental expression of TcRyR and TcIP3R

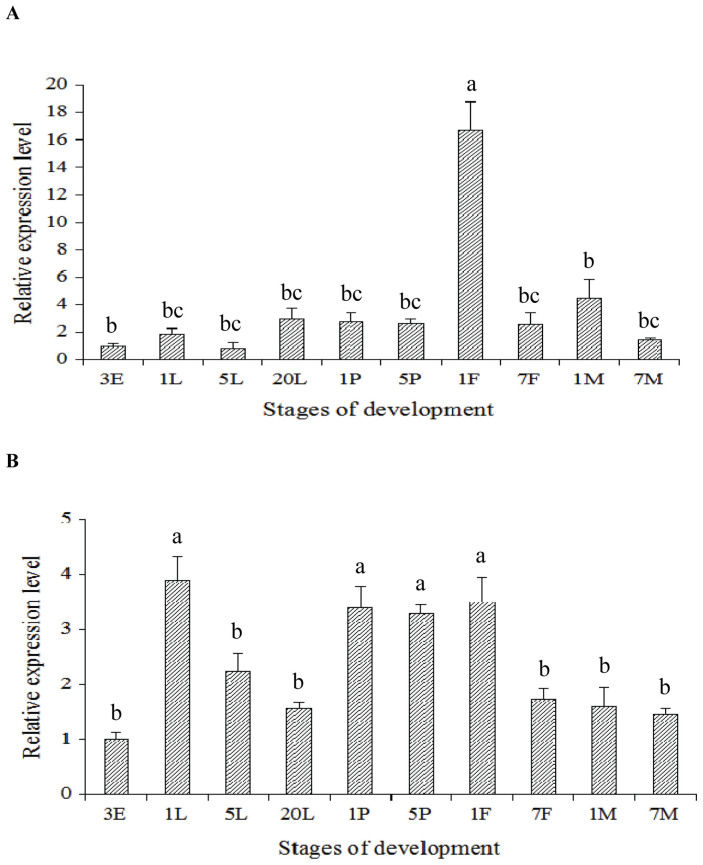

To gain understanding of the developmental expression of TcRyR and TcIP3R in T. castanuem, the mRNA levels of these two CRC genes were analyzed using RT-qPCR at different developmental stages of T. castanuem insects, including 3-day-old eggs, 1-, 5- and 20-day-old larvae, 1- and 5-day-old pupae, 1- and 7-day-old female adults, and 1- and 7-day-old male adults. The developmental expression pattern revealed that the mRNA levels of TcRyR were highest in the 1-day-old female adults, while there was no significant difference among the egg, larval and pupal stages (Fig. 4A). The highest and lowest mRNA expression levels of TcIP3R were observed in the 1-day-old larvae and 3-day-old eggs, respectively (Fig. 4B).

Figure 4. Relative mRNA expression levels of TcRyR (A) and TcIP3R (B) in the different development stages of Tribolium castaneum.

The relative expression level was expressed as the mean ± SE (N = 3), with the 3-day old egg as the calibrator. The different lowercase letters above the columns indicate significant differences at the P<0.05 level. 3E: 3-day-old egg; 1L: 1-day-old larvae; 5L: 5-day-old larvae; 20L: 20-day-old larvae;1P: 1- day-old pupa; 5P: 5-day-old pupa; 1F: 1-day-old female adult; 7F: 7-day-old female adult; 1M: 1-day-old male adult; 7M: 7-day-old male adult.

RNAi of TcRyR and TcIP3R

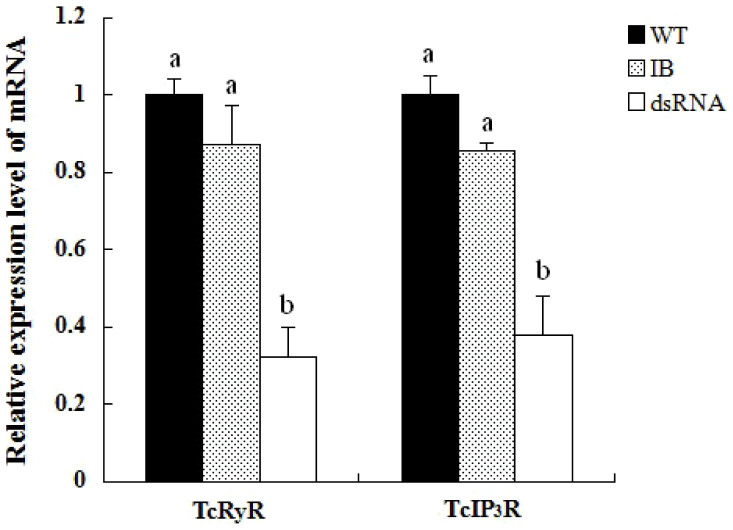

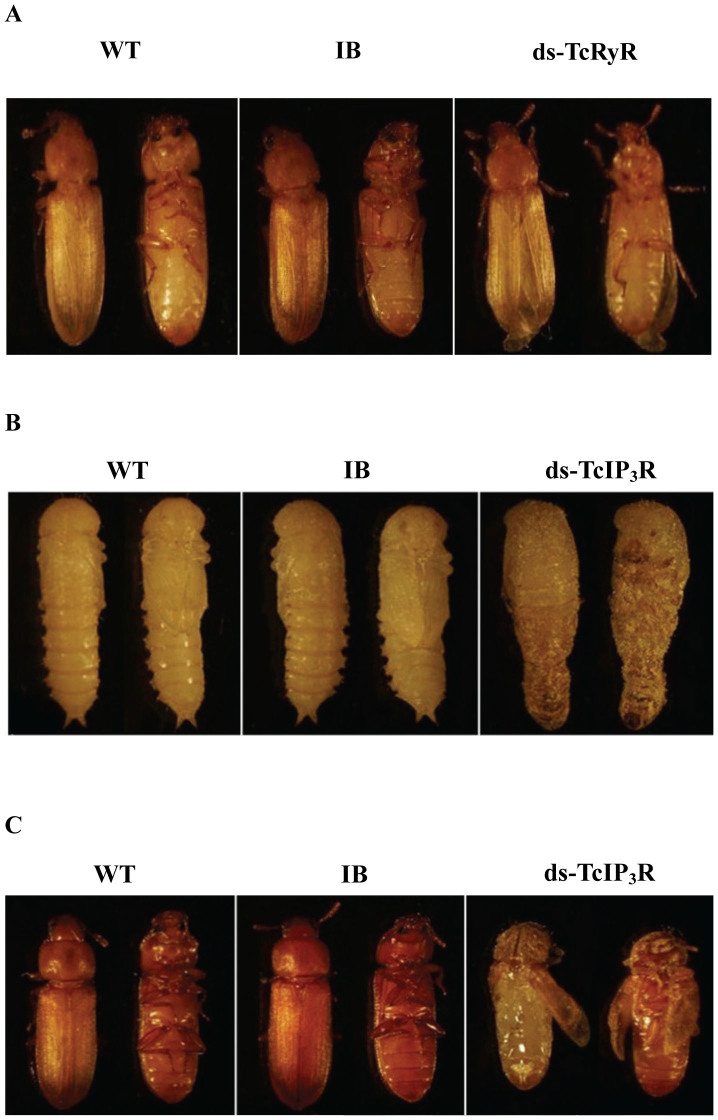

We employed RNAi to investigate the putative function of TcRyR and TcIP3R. The silencing effects of dsTcRyR and dsTcIP3R were detected by qPCR on the sixth day after the dsRNA injection. The results showed that the transcript levels of TcRyR and TcIP3R in the injected larvae were significantly suppressed by 67.86% and 61.99%, respectively, compared with those in the uninjected wild-type larvae (Fig. 5). While the injected larvae with dsTcRyR underwent normal larval–larval and larval–pupal molts and developed into adults, the hind wings of 65.9% of the individual adults could not fold properly (Fig. 6A), and all individual adults lost their ability to crawl early in adulthood and died two weeks later. In the group treated with dsTcIP3R, 64.7% of the larvae were unable to cast their molts completely and could not undergo normal larval–pupal metamorphosis (Fig. 6B), and thus died entrapped in their larval cuticles during the pupal stage. While the rest of the larvae could develop into pupae, the pupae could not undergo normal pupal-adult metamorphosis (Fig. 6C).

Figure 5. Expressions of TcRyR and TcIP3R transcripts in the uninjected wild-type larvae (WT group), the buffer-injected larvae (IB group), and the dsRNA injected group.

Figure 6. RNAi phenotypes of TcRyR and TcIP3R.

A. Injection of dsRNA for TcRyR resulted in abnormal folding of the adult hind wings. B. Injection of dsRNA for TcIP3R resulted in defective larval–pupal metamorphosis. C. Injection of dsRNA for TcIP3R resulted in defective pupal-adult metamorphosis.

Discussion

Developing insecticides that act on novel biochemical targets is important for crop protection due to the ability of insects to rapidly evolve insecticide resistance. It has been suggested that insect calcium channels would offer an excellent insecticide target for commercial exploitation23,24, and the recent discovery of diamide insecticides has prompted the studies on insect RyRs. However, no insecticidal compounds targeting IP3Rs have been reported so far in the literature, and the studies on insect IP3R are solely limited to Drosophila. In this study, we cloned and characterized RyR and IP3R genes from T. castaneum. As with other invertebrates, the sequencing data evidenced the existence of only a single RyR and IP3R gene, TcRyR and TcIP3R, in T. castaneum, which was supported by homology searches on the T. castaneum genomic database. The amino acid identities of TcRyR with human homologues (44–46%) were considerably lower than those observed with TcIP3R (53%–61%), which may suggest that RyRs are better targets for insecticidal molecules with lower mammalian toxicity.

Despite the large difference in size and the low amino acid identity between TcRyR and TcIP3R, these two CRCs share a similar architecture consisting of NH2-terminal modular regulatory domains that contain an RIH-RIH-RIHA arrangement and a COOH-terminal transmembrane (TM) domain that contains the conserved GGGXGD motif. The RIH-RIH-RIHA arrangement is also found in many “ancestral CRC” eukaryotic proteins, but it is undetectable in any prokaryotic protein25. In both RyRs and IP3Rs, the conserved GGGXGD motif acts as the selectivity filter, which enables the channels to discriminate between ions. Mutagenesis of residues in this region of both RyR and IP3R alters the channel conductance26,27,28. Recently, it was found that an IP3R in which the COOH-terminal transmembrane region was replaced with that from the RyR1 was blocked by ryanodine, indicating that activation mechanisms were conserved between IP3R and RyR29. These conserved structural features and activation mechanisms suggested that an ancient duplication event probably gave rise to these two classes of intracellular CRC genes. A recent study revealed that RyRs might arise from pre-existing, ancestral IP3R-like channels present in prokaryotes by incorporating promiscuous ‘RyR’ and ‘SPRY’ domains via horizontal gene transfer25.

Both RyRs and IP3Rs contribute to Ca2+ signals and play important roles in a vast array of physiological processes, as has been investigated in knockout mouse models. RyR1 knockout mice die perinatally due to respiratory failure caused by defective excitation-contraction (E–C) coupling in the diaphragm30, and RyR2 knockout mice died at approximately embryonic day 10 with morphological abnormalities in the heart tube31. In contrast, RyR3 knockout mice are viable but exhibited impairments in memory functions and social interaction32,33,34. IP3R-knockout studies have revealed that IP3R1-deficient mice die in utero or by the weaning period, and the survivors have severe behavioral abnormalities in the form of ataxia and epileptic seizures35, whereas IP3R2 and IP3R3 double knock-out mice exhibit hypoglycemia and deficits of olfactory mucus secretion, suggesting that these two isoforms play key roles in the exocrine physiology and perception of odors36,37.

While knockout studies of the mammalian RyR and IP3R have demonstrated their critical role in development and physiology, the functional characterization of the insect RyR and IP3R is still limited. In this study, the contribution of TcRyR and TcIP3R to the developmental and physiological outcomes was assessed by in vivo RNAi. Our data show that the suppression of the TcRyR transcript in the late larval stage leads to abnormalities in the folding of the hind wings and crawling behavior in adults. It has been reported in the neopterous insects that the third axillary sclerite and muscle were involved in the folding of the wing into the rest position38,39. On the other hand, it has been reported in Drosophila that crawling movements were powered by muscle contractions40. Thus, the abnormal phenotype observed in this study might be due to the impairment of muscle EC-coupling. This is consistent with previous findings showing that mutant fruit flies lacking RYR expression (Ryr16) display impairment of muscle EC-coupling in the larval development41, and mutant Caenorhabditis elegans with a defective RyR gene (unc-68) exhibit diminished muscle function and decreased movement42. On the other hand, when the mRNA expression levels of TcIP3R were suppressed in the late larval stage, defects were observed in larval–pupal and pupal-adult metamorphosis. A similar result was also observed in Drosophila that disruption of the Drosophila IP3R gene leads to lowered levels of ecdysone and delayed larval molting43. These results suggest that calcium release via IP3R might play an important role in regulating ecdysone synthesis and release during molting and metamorphosis in insects. Further research is needed to confirm this hypothesis.

Methods

Insects

The Georgia-1 (GA-1) strain of T. castaneum was cultured on 5% (w/w) yeasted flour at 30°C and 40% RH under standard Conditions44.

Total RNA isolation and reverse transcription

Total RNAs were extracted using the SV total RNA isolation system (Promega, Madison, WI) according to the manufacturer's instructions. First-strand cDNA was synthesized from 5 µg of total RNA using the Primescript™ First-Strand cDNA Synthesis kit (TaKaRa, Dalian, China), according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Polymerase chain reaction

The amino acid sequences of RyR and IP3R from D. melanogaster (GenBank: BAA41471 and AAN13240) were searched against BeetleBase (http://www.bioinformatics.ksu.edu/blast/bblast.html), and the regions with significant hits were manually annotated to identify the putative transcript and translation products. The ClustalW algorithm45 was used to align protein sequences to further support annotation predictions. Specific primer pairs were designed based on the sequences identified above (Table 1). PCR reactions were performed with LA Taq™ DNA polymerase (TaKaRa, Dalian, China).

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

RT-qPCR reactions were performed on the Bio-Rad CFX 96 Real-time PCR system using SYBR® PrimeScript™ RT-PCR Kit II (Takara, Dalian, China) and gene specific primers (Table 1). The procedures for RT-qPCR were the same as those described by Zhu et al46. Ribosomal protein S3 (rps3, GenBank: CB335975) was used as an internal control47. The PCR reaction volume was 20 µL containing 2 µL of diluted cDNA, 0.4 μM of each primer, 10.0 µL SYBR Premix EX TaqTM II(2×)and 0.4 µLROX Reference Dye II(50×). Two types of negative controls were set up including a no-template control and a reverse transcription negative control. Thermocycling conditions were set as an initial incubation of 95°C for 30 s and 40 cycles of 95°C for 10 s and 60°C for 15 s. Afterwards, a dissociation protocol with a gradient from 57°C to 95°C was used for each primer pair to verify the specificity of the RT-qPCR reaction and the absence of primer dimer. The mRNA levels were normalized to rps3 with the ΔΔCT method using Bio-Rad CFX Manager 2.1 software. The means and standard errors for each time point were obtained from the average of three independent sample sets.

Cloning and sequence analysis

RT-PCR products were cloned into the pMD18-T vector (TaKaRa, Dalian, China) and sequenced. Nucleotide sequences from individual clones were assembled into a full-length contig using the ContigExpress program, which is part of the Vector NTI Advance 9.1.0 (Carlsbad, CA, Invitrogen) suite of programs. The sequence alignment was performed using ClustalW45 with the default settings. Transmembrane region predictions were made using the TMHMM Server v.2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/). Conserved domains were predicted using the Conserved Domains Database (NCBI) or by alignment to other published RyRs and IP3Rs.

RNAi

Double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) were synthesized using the MEGAclear™ Kit (Ambion, Austin, TX) based on nucleotides 502-1118 (617 bp) and 1136-1646 (511 bp) of the ORF region of the TcRyR and TcIP3R, respectively. Each 20-day-old larva was injected with 200 nL of a solution containing approximately 200 ng of dsRNA. On the sixth day after the dsRNA injection, the insects were used to detect the suppression of the TcRyR and TcIP3R transcript by RT-qPCR. Afterwards, the insects were reared under the standard conditions mentioned above, and the phenotypes were visually observed. The buffer-injected larvae (IB group) and the uninjected wild-type larvae (WT group) were set as controls in all injection experiments. Three replications were carried out with at least 30 insects in each control or treatment.

Database entries

The entire coding sequences of TcRyR and TcIP3R have been deposited in the GenBank and the accession numbers are KM216386 and KM216387, respectively.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: J.W., B.L. Performed the experiments: Y.L., C.L., J.G., W.W., L.H., X.G. Analyzed the data: Y.L., J.W., C.L., B.L. Wrote the paper: J.W., Y.L.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under grant no. 31171841, and sponsored by Qing Lan Project of Jiangsu Province, People's Republic of China.

References

- Amador F. J., Stathopulos P. B., Enomoto M. & Ikura M. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels: lessons from structure-function studies. FEBS J. 280, 5456–5470 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prole D. L. & Taylor C. W. Identification of intracellular and plasma membrane calcium channel homologues in pathogenic parasites. PLoS One 6, e26218 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai X. & Clapham D. E. Ancestral Ca2+ signaling machinery in early animal and fungal evolution. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 91–100 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasan G. & Rosbash M. Drosophila homologs of two mammalian intracellular Ca2+-release channels: identification and expression patterns of the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate and the ryanodine receptor genes. Development 116, 967–975 (1992). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa S. et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor in Drosophila melanogaster. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 16613–16619 (1992). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima H. et al. Isolation and characterization of a gene for a ryanodine receptor/calcium release channel from Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS Lett. 337, 81–87 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nauen R. Insecticide mode of action: return of the ryanodine receptor. Pest Manag. Sci 62, 690–692 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sattelle D. B., Cordova E. & Cheek T. R. Insect ryanodine receptors: molecular targets for novel pest control agents. Invertebr. Neurosci. 8, 107–119 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K. et al. Molecular characterization of flubendiamide sensitivity in lepidopterous ryanodine receptor Ca2+ release channel. Biochemistry 48, 10342–10352 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y. et al. Identification of a critical region in the Drosophila ryanodine receptor that confers sensitivity to diamide insecticides. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 43, 820–828 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troczka B. et al. Resistance to diamide insecticides in diamondback moth, Plutella xylostella (Lepidoptera: Plutellidae) is associated with a mutation in the membrane-spanning domain of the ryanodine receptor. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 42, 873–880 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foskett J. K., White C., Cheung K. H. & Mak D. O. Inositol trisphosphate receptor Ca2+ release channels. Physiol. Rev. 87, 593–658 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen S. R. W., Ebisawa K., Li X. & Zhang L. Molecular identification of the ryanodine receptor Ca2+ sensor. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 14675–14678 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G. G. & MacLennan D. H. Functional consequences of mutations of conserved, polar amino acids in transmembrane sequences of the Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) of rabbit skeletal muscle sarcoplasmic reticulum. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 31867–31872 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L. et al. Evidence for a role of the lumenal M3-M4 loop in skeletal muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor) activity and conductance. Biophys. J. 79, 828–840 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikoshiba K. The IP3 receptor/Ca2+ channel and its cellular function. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 74, 9–22 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosanac I. et al. Crystal structure of the ligand binding suppressor domain of type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Mol. Cell 17, 193–203 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards S. et al. The genome of the model beetle and pest Tribolium castaneum. Nature 452, 949–955 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Molecular characterization of a ryanodine receptor gene in the rice leaffolder, Cnaphalocrocis medinalis (Guenée). PLoS ONE 7, e36623 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J. et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a ryanodine receptor gene in brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens (Stål). Pest Manag. Sci. 70, 790–797 (2014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nucifora F. C. Jr, Li S. H., Danoff S., Ullrich A. & Ross C. A. Molecular cloning of a cDNA for the human inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor type 1, and the identification of a third alternatively spliced variant. Mol. Brain Res. 32, 291–296 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorrentino V., Barone V. & Rossi D. Intracellular Ca2+ release channels in evolution. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 10, 662–667 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall L. M. et al. Calcium channel as a new potential target for insecticides, in Molecular Actions of Insecticides on Ion Channels, ed. by Clark JM American Chemical Society, Washington, pp. 162–172 (1995). [Google Scholar]

- Bloomquist J. R. Ion channels as targets for insecticides. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 41, 163–190 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackrill J. J. Ryanodine receptor calcium release channels: an evolutionary perspective. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 740, 159–182 (2012) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao M. et al. Molecular identification of the ryanodine receptor pore-forming segment. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 25971–25974 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du G. G., Guo X., Khanna V. K. & MacLennan D. H. Functional characterization of mutants in the predicted pore region of the rabbit cardiac muscle Ca2+ release channel (ryanodine receptor isoform 2). J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31760–31771 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schug Z. T. et al. Molecular characterization of the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor pore-forming segment. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 2939–2948 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seo M. D. et al. Structural and functional conservation of key domains in InsP3 and ryanodine receptors. Nature 483, 108–112 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima H. et al. Excitation–contraction uncoupling and muscular degeneration in mice lacking functional skeletal muscle ryanodine-receptor gene. Nature 369, 556–559 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima H. et al. Embryonic lethality and abnormal cardiac myocytes in mice lacking ryanodine receptor type 2. EMBO J. 17, 3309–3316 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouzu Y., Moriya T., Takeshima H., Yoshioka T. & Shibata S. Mutant mice lacking ryanodine receptor type 3 exhibit deficits of contextual fear conditioning and activation of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II in the hippocampus. Mol. Brain Res. 76, 142–150 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galeotti N. et al. Different involvement of type 1, 2, and 3 ryanodine receptors in memory processes. Learn Mem. 15, 315–323 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo N. et al. Comprehensive behavioral phenotyping of ryanodine receptor type 3 (RyR3) knockout mice: decreased social contact duration in two social interaction tests. Front Behav. Neurosci. 3, 3 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M. et al. Ataxia and epileptic seizures in mice lacking type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor. Nature 379, 168–171 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Futatsugi A. et al. IP3 receptor types 2 and 3 mediate exocrine secretion underlying energy metabolism. Science 309, 2232–2234 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda N. et al. Decreased olfactory mucus secretion and nasal abnormality in mice lacking type 2 and type 3 IP3 receptors. Eur. J. Neurosci. 27, 2665–2675 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharplin J. Wing folding in Lepidoptera. Can. Ent. 96, 148–149 (1964). [Google Scholar]

- Rheuben M. B. & Kammer A. E. Structure and innervation of the third axillary muscle of Manduca relative to its role in turning flight. J. Exp. Biol. 131, 373–402 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckscher E. S., Lockery S. R. & Doe C. Q. Characterization of Drosophila larval crawling at the level of organism, segment, and somatic body wall musculature. J. Neurosci. 32, 12460–12471 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan K. M., Scott K., Zuker C. S. & Rubin G. M. The ryanodine receptor is essential for larval development in Drosophila melanogaster. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97, 5942–5947 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maryon E. B., Saari B. & Anderson P. Muscle-specific functions of ryanodine receptor channels in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Cell Sci. 111, 2885–2895 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh K. & Hasan G. Disruption of the IP3 receptor gene of Drosophila affects larval metamorphosis and ecdysone release. Curr. Biol. 7, 500–509 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haliscak J. P. & Beeman R. W. Status of malathion resistance in five genera of beetles infesting farm-stored corn, wheat and oats in the United States. J. Econ. Entomol. 76, 717–722 (1983). [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J. D., Higgs D. G. & Gibson T. J. CLUSTALW: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucl. Acids Res. 22, 4673–4680 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y., Xie Z., Wang J., Liu Y. & Wang J. Cloning and characterization of two genes coding for the histone acetyltransferases, Elp3 and Mof, in brown planthopper (BPH), Nilaparvata lugens (Stål). Gene 513, 63–70 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arakane Y. et al. Functional analysis of four neuropeptides, EH, ETH, CCAP and bursicon, and their receptors in adult ecdysis behavior of the red flour beetle, Tribolium castaneum. Mech. Dev. 125, 984–995 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]