Abstract

Visual transduction is the process in the eye whereby absorption of light in the retina is translated into electrical signals that ultimately reach the brain. The first challenge presented by visual transduction is to understand its molecular basis. We know that maintenance of vision is a continuous process requiring the activation and subsequent restoration of a vitamin A–derived chromophore through a series of chemical reactions catalyzed by enzymes in the retina and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). Diverse biochemical approaches that identified key proteins and reactions were essential to achieve a mechanistic understanding of these visual processes. The three-dimensional arrangements of these enzymes' polypeptide chains provide invaluable insights into their mechanisms of action. A wealth of information has already been obtained by solving high-resolution crystal structures of both rhodopsin and the retinoid isomerase from pigment RPE (RPE65). Rhodopsin, which is activated by photoisomerization of its 11-cis-retinylidene chromophore, is a prototypical member of a large family of membrane-bound proteins called G protein–coupled receptors (GPCRs). RPE65 is a retinoid isomerase critical for regeneration of the chromophore. Electron microscopy (EM) and atomic force microscopy have provided insights into how certain proteins are assembled to form much larger structures such as rod photoreceptor cell outer segment membranes. A second challenge of visual transduction is to use this knowledge to devise therapeutic approaches that can prevent or reverse conditions leading to blindness. Imaging modalities like optical coherence tomography (OCT) and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) applied to appropriate animal models as well as human retinal imaging have been employed to characterize blinding diseases, monitor their progression, and evaluate the success of therapeutic agents. Lately two-photon (2-PO) imaging, together with biochemical assays, are revealing functional aspects of vision at a new molecular level. These multidisciplinary approaches combined with suitable animal models and inbred mutant species can be especially helpful in translating provocative cell and tissue culture findings into therapeutic options for further development in animals and eventually in humans. A host of different approaches and techniques is required for substantial progress in understanding fundamental properties of the visual system.

Keywords: rhodopsin, photoreceptors, phototransduction, G protein–coupled receptor(s), receptor phosphorylation, membrane proteins, signal transduction, protein structure, vision

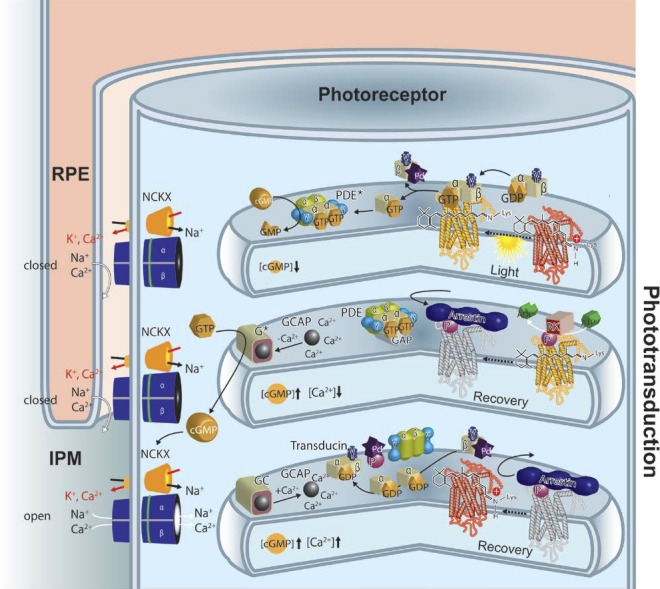

The last 30 years of visual system research have resulted in a greater understanding of cellular signal transduction processes in the eye than in any other organ of human body. Signaling pathways, initiated by activation of rod and cone visual pigments, orchestrate precise changes in cGMP and Ca2+ that act as second messengers to generate electrical signals.1–8 In 1994, when at the University of Washington, I asked: “Is vertebrate phototransduction solved? Although the general mechanism of photoactivation is now known in great detail, key steps in the sequence of reactions associated with the quenching, light adaptation, channel function, and restoration of the dark state of photoreceptors remain to be elucidated. Among many questions, a few seem to be critical for understanding phototransduction and related hormonal-transduction systems: How is the rhodopsin structure related to the activated and quiescent states of the receptor? ….”9 Detailed progress has been made in elucidating G protein inactivation,10 rhodopsin kinase and arrestin structure/function,11–13 and guanylate cyclase-activating proteins' (GCAPs) regulation of guanylate cycles,14,15 among other processes. Although far from complete and quantitative (Fig. 1), today we have a solid conceptual framework for the processes of visual pigment photoactivation, signal amplification, and quenching of the phototransduction cascade.1–8

Figure 1.

Phototransduction in a rod outer segment. Phototransduction can be described in three stages shown from top to bottom in this cartoon. When light strikes rhodopsin (red), it causes isomerization of the 11-cis-retinylidene chromophore to an all-trans configuration and a conformational change in the opsin protein. This, in turn, leads to formation of a complex with the heterotrimeric G protein, transducin. Nucleotide exchange in the transducin α-subunit from guanosine diphosphate to GTP causes dissociation of transducin with formation of the transducin α-subunit. This subunit interacts with tetrameric cGMP–specific PDE6, whereas the transducin βγ-subunit complexes with phosducin. One activated rhodopsin molecule can activate dozens of transducin molecules in this first amplification stage of phototransduction. Displacement of the inhibitory γ-subunit activates PDE in the second amplification step of phototransduction. The resulting decrease in the concentration of cGMP is associated with a decrease in intradiscal Ca2+ concentration because cGMP is a ligand for cGMP-gated cation channels (shown in blue in the plasma membrane), nonselective channels that also allow passage of Ca2+ in their cGMP-bound state. The low Ca2+-level is maintained by the light-insensitive Na+/Ca2+-K+ exchanger, which extrudes Ca2+ ions out against a gradient in exchange for Na+ and K+ ions. Each of the above-activated molecules needs to return to its inactive state before absorption of the next photon. Thus, rhodopsin is phosphorylated at its C-terminus by GRK1 (or rhodopsin kinase [RK]), followed by binding of arrestin, a capping protein. Guanosine triphosphate is hydrolyzed by the α-subunit of transducin with the help of a GTPase-activating protein. Guanylate cyclase 1 and GC2 (GC, light/dark-brown box) are activated by Ca2+-binding proteins (GCAP1 and GCAP2, black ball) in their Ca2+-free forms to restore cGMP levels and open the cyclic nucleotide–gated cation channels in the plasma membrane. Guanylate cyclase-activating proteins are inactivated and GC activities return to their dark condition. Once GTP is hydrolyzed by the α-subunit of transducin along with phosphorylation of phosducin, the heterotrimeric G protein is restored. Opsin recombines with 11-cis-retinal and the rhodopsin thus formed is ready to be photoactivated. Note that all these processes take place on the cytoplasmic surfaces of disc and plasma membranes.

Tremendous progress has been made at the molecular level, specifically in five areas of phototransduction research. These include: molecular and atomic resolution structural studies of membrane and soluble proteins that contribute to this signaling cascade2; groundbreaking improvements in understanding of the visual (retinoid) cycle16; advancement in understanding the cell biology of the visual system17–20 with multiple advanced imaging modalities21–27; identification of disease-causing genes for a vast number of retinal/eye disorders28; and pursuit of novel concepts, along with animal and human trials of therapeutics, to prevent or stabilize vision loss, or restore vision in blind individuals.

We have been pioneers in applying novel technologies to obtain detailed molecular insights and, more recently, therapeutics. My presentation is not intended to be fully comprehensive or to upstage original discoveries, but rather to provide an overview of the recent progress from the perspective of my own laboratory's research. It is also important to point out that without fundamental molecular-level research into the secrets of life, progress in translational research would be markedly diminished. Understanding the richness and complexity of the underlying basic science is essential when addressing challenges posed by the complexity of visual perception and eye diseases such as AMD, glaucoma, or diabetic retinopathy. A comprehensive and integrated understanding of the visual system is indeed crucial for the discovery of mechanism-based novel treatments for blinding diseases.

Rhodopsin at the Center of Vision

Rhodopsin's function as a light receptor in the eye was recognized over a century ago.29–31 This transmembrane protein has been the major focus of research, perhaps more than any other protein of the visual system. Without rhodopsin and its homologous cone pigments, there would be no image-forming vision.32–35 Rhodopsin also has a special place in biological research because it is a prototypical member of the G protein–coupled receptor (GPCR) family, a vast class of cell surface proteins that transmit signals across cellular plasma membranes via transmembrane domains in response to binding by hormones, neurotransmitters, odorant and taste molecules.

Rhodopsin is composed of an opsin protein covalently attached to a light-sensitive chromophore, 11-cis-retinal. The peptide sequence of opsin, the first among GPCRs, was determined by Ovchinnikov36,37 in the former Soviet Union (Shemyakin Institute of Bioorganic Chemistry, USSR Academy of Sciences) and Hargrave38 (University of Illinois) in the United States, followed shortly by the cloning of its gene by Nathans and Hogness39,40 (Johns Hopkins University). Based on several biochemical techniques, a topology including seven membrane-spanning α-helical domains was proposed for rhodopsin that compares favorably with the one that was determined almost 2 decades later by x-ray crystallography.41,42 Mutations in the opsin gene are major causes of inherited blinding disorders.43 The mutation of P23H that causes autosomal-dominant retinitis pigmentosa (RP), was the first that linked a human blinding disease to a specific gene.44 To date, over 100 mutations in the opsin gene have been identified that are linked to this disease with just a few that cause autosomal recessive RP.43,45 The signaling properties of rhodopsin were also at the forefront of GPCR research. Fung et al.46 (Stanford University) demonstrated that the visual signal is amplified in the retina when one photoactivated receptor activates many molecules of the rod-specific G protein called transducin. Photoactivated rhodopsin is also a substrate for rhodopsin kinase (or G protein–coupled receptor kinase [GRK1]).47 In the early 1970s, it was found that rhodopsin binds, when activated and phosphorylated, to a capping protein known as S-antigen (soluble antigen; today, this protein is called arrestin), which is implicated in ocular uveitis.48 Thereafter, all-trans-retinylidene is hydrolyzed and released from the active site.49 Phosphorhodopsin is dephosphorylated by protein phosphatase 2A50,51 and returns to the ground state. The biochemical characterization of rhodopsin signaling was instrumental for the studies of other GPCRs, as the majority of them use similar mechanisms for propagation and termination of hormonal signals.

Rhodopsin was the first GPCR whose electron density projection maps were determined from two-dimensional (2D) crystals analyzed by EM.52,53 However, no high-resolution structure was available, making it difficult to understand the activation mechanism and effect of disease-causing mutations. It was difficult to envision the possibility of crystallizing rhodopsin because the mass of the hydrophilic domain of this protein was small, and thus the contact area between molecules within the crystal limited. Obviously rhodopsin purification and crystallization required detergent, another major obstacle to its crystallization. Many groups were trying to crystallize this receptor, but we were the one that got there first. Research assistant Van Hooser supplied high quality rod outer segment preparations from freshly isolated bovine retinas to a postdoctoral fellow in my laboratory, Okada, who a few years later obtained the first three-dimensional (3D) diffracting crystals suitable for x-ray crystallography.54 It was an iterative process that only few could stick to and clearly Tetsuji had motivation, talent, and support to optimize the initial hit in crystallization. Perhaps the single-most important breakthrough was understanding the properties of rhodopsin and how it behaves under different experimental conditions. A collaboration with R Stenkamp, D Taylor (both from University of Washington), and M Miyano (Structural Biophysics Laboratory, RIKEN Harima Institute, Japan) then led to a major breakthrough: the three-dimensional atomic structure of rhodopsin, the first of any GPCR (Fig. 2).42 Even today, the rhodopsin structure remains the only structure of a native GPCR with a covalently bound ligand that has not been modified in terms of its amino acid sequence; and it also contains posttranslational modifications that are native to the mammalian retina, including palmitoylation, N-terminal acetylation, a disulfide bridge, and Asn2 and Asn15 glycosylation (each with [Man]3[GlcNAc]3 groups). The structure of rhodopsin contains seven transmembrane helices with the chromophore bound via the protonated Schiff base approximately two-thirds of the way from the cytoplasmic surface, as predicted by biophysical methods.55 The cytoplasmic side revealed an unexpected helix 8 that runs parallel to the surface of the membrane. Another unexpected feature was a “plug” formed by intradiscal loops that create a β-sheet structure beneath the chromophore. Among the three cytoplasmic loops, the C3-loop has displayed the most diverse conformations among the different crystal structures of rhodopsin. A specific retinoid-binding pocket allows only some cis-retinoids (11-cis-, 9-cis-, 7-cis- and several double cis-retinals) to bind to opsin.32 The structure explained several dozen biochemical reports on the structure/function relationships of rhodopsin, mostly proposed via mutagenesis studies (for reviews see Refs. 2–4, 16, 56–68).

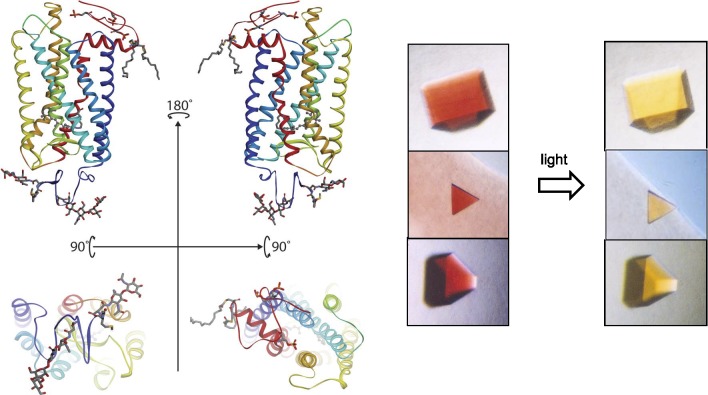

Figure 2.

Rhodopsin structure and crystals. Left top: ribbon drawings of rhodopsin (PDB accession code: 1F88)42 in the plane of a disc membrane (two views rotated by 180°). Bottom: the intradiscal side (left) and cytoplasmic side (right) of this receptor. Right: a photo-stable crystal form of the dark inactive state (left) and light-exposed activated state (right) of the receptor. Crystal pictures are reproduced from Salom D, Le Trong I, Pohl E, et al. Improvements in G protein-coupled receptor purification yield light stable rhodopsin crystals. J Struct Biol. 2006;156:497–504. Copyright © 2006 Elsevier, Inc.; Salom D, Lodowski DT, Stenkamp RE, et al. Crystal structure of a photoactivated deprotonated intermediate of rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:16123–16128. Copyright © 2006 The National Academy of Sciences of the USA; and Salom D, Padayatti PS, Palczewski K. Crystallization of G protein–coupled receptors. Methods Cell Biol. 2013;117:451–468.299 Copyright © 2013 Elsevier, Inc., with permission from Elsevier, Inc. and the National Academy of Sciences.

Although initial efforts were focused on ground-state rhodopsin, our attention then turned toward solving the structure of activated rhodopsin which occurs only transiently. A renewed effort by Salom et al.69 led to generation of crystals that could be activated by light while retaining their crystallographic integrity (Fig. 2, right). With the help of another postdoctoral fellow, Lodowski,70 the structure of these crystals was solved. The major breakthrough that Salom et al.69 employed was the use of ammonium sulfate for protein concentration, eliminating the excess of detergent. This precipitation technique was not known for membrane proteins. Moreover, crystals with a high content of detergent/lipids appeared to be unstable when exposed to light. Discovery came as a result of hard and persistent work. To our surprise, upon activation, the conformational changes in rhodopsin were not as complex as proposed from earlier EPR studies.71,72 After solving the opsin structures with and without a fragment of transducin, other intermediates, and constitutively active mutants of rhodopsin, a more complete picture of the activation process emerged.73–85 Rhodopsin photoactivation causes the isomerization of 11-cis- to all-trans-retinylidene and, subsequently, a cascade of irreversible conformational changes until rhodopsin reaches its meta I state.67 This transition leads to a change in the counterion of the protonated Schiff base, and a new network of hydrogen bonds is established within the chromophore-binding site.61,86 Meta I remains in an equilibrium with the meta II state. During transition from the meta I to meta II state, glutamate (Glu)113 is neutralized. This reaction can be readily monitored by changes in the absorption of rhodopsin from approximately 500 nm (in meta I) to 380 nm (in meta II).87 Meanwhile, as many as 30 water molecules, which fill the transmembrane segment of rhodopsin, become reorganized and unlock the “E/DRY” motif on the cytoplasmic side of the protein along with protonation of Glu134, a key residue in this microdomain.68 Recent computational studies revealed that a hydrophobic layer of amino acid residues next to the characteristic NPxxY motif forms a gate, opening a continuous water channel upon receptor activation.88 In addition, the end region of helix VI moves toward the cytoplasmic side.67,89,90 Finally, another change occurs in the NPxxY motif of helix VII and helix VIII conserved in GPCRs.91 These changes are considered critical during the activation process for all GPCRs.

To summarize, the rhodopsin x-ray structure: dispelled the myth that GPCRs cannot be crystalized; provided the three-dimensional positions of all amino acid residues including new unanticipated structural elements; set the field on the right track toward understanding rhodopsin photoactivation; outlined the binding pocket of visual chromophore; and firmly established a key role for water molecules in a hydrogen bonding network within the hydrophobic core of this protein.

Today, our structural questions are answered in large part by x-ray crystallography. However, x-ray crystallography only captures proteins in their most thermodynamically favorable conformations under the particular crystallization conditions. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) techniques are also well suited to reveal the structural dynamics of proteins.92–95 Along with the above-mentioned changes in photoactivated rhodopsin, relaxation (i.e., increased flexibility) of this receptor allows the functional docking of transducin and activation of this G protein. Key remaining unsolved issues are: more detailed structural organization of rhodopsin in native membranes and its functional consequences; the molecular mechanisms of photoisomerized chromophore release and rebinding of newly made 11-cis-retinal to unliganded opsin; the biochemical cycle of rhodopsin in the cell, including its synthesis, membrane insertion, intracellular transport, disc formation and shedding through phagocytosis by the RPE, and degradation; how pathogenic mutations change the structure/function of rhodopsin; and a new classification of these mutants based of their function rather than older classifications based on cellular localization in experimental cell lines or the capability to bind 11-cis-retinal.

Rhodopsin Is Critical for the Organization of Rod Outer Segments

Rhodopsin is an essential component of the elongated retinal ciliary compartment of the rod cell called the “outer segment.”5,32,96 In mice, rod outer segments have a length of 23.6 ± 0.4 μm and a diameter of 1.22 ± 0.12 μm.99 Each mammalian rod outer segment consists of 600 to 1000 or more (810 ± 10 in mice) distinct flattened discs enclosed by the plasma membrane.97–99 Rhodopsin resides in disc membranes as their major component (>90% of total protein), and is less densely packed in the plasma membrane.100 Approximately half of the surface of each disc is occupied by rhodopsin, with the remainder filled mostly with lipids, cholesterol, and less abundant proteins.100–102 Moreover, rhodopsin constitutes ~50% of the protein mass of rod outer segment plasma membranes. Functional differences between the two populations of rhodopsin in the plasma and disc membranes remain unknown. Higher levels of cholesterol in the plasma membrane compared with disc membranes could decrease rhodopsin's activity. Absence of rhodopsin leads to rudimentary ciliary structures and eventually to death of rod cells.103,104 Diminution of rhodopsin expression proportionally decreases the size of rod outer segment structures, while maintaining the same density of rhodopsin as in native discs,98,105 whereas overexpression of rhodopsin results in enlargement of these structures that ultimately causes their instability.105–107

Early work using biophysical approaches by Chabre108 (Laboratoire de Biophysique Moléculaire et Cellulaire, Grenoble, France), Saibil109 (Department of Biological Sciences and ISMB Birkbeck College, London, UK), and Cone,110 and Poo111 (Johns Hopkins University) suggested that rhodopsin is monomeric and moves rapidly within the discs. Such mobility was arguably required for high speed phototransduction. For example, Poo111 and Cone110 thought that they measured the mobility of rhodopsin in frog disc membranes,111 but full recovery of rhodopsin absorption was never observed in the bleached area. Recent studies found an explanation,112 namely that rhodopsin in such membranes undergoes transitions from rhodopsin (~500 nm) → meta II (~380 nm) → meta III (~480 nm). Thus, what was measured by Poo111 and Cone110 was a partial return to absorption in the meta III state. More recent work appears to add more evidence for “fast diffusing monomers of rhodopsin” within the disc113–115 while another catalytic aspect adds to the confusion. Rhodopsin, in its monomeric state, can activate transducin either in detergent or in size-controlled membranes called nanodiscs.116,117 Thus, unlike family C GPCRs (neurotransmitter receptors),118 oligomerization is not required for signal transduction by rhodopsin, at least in model systems.

Hence, classical diffusion studies implicating monomeric rhodopsin provided only indirect evidence and more direct imaging methods were needed. With this background, a very active and productive collaboration developed between my laboratory and a world expert in atomic force microscopy (AFM) and membrane biology, Andreas Engel from Biozentrum (Basel, Switzerland). Atomic force microscopy is a high-resolution method that can image electronic orbitals of heavy metals or individual atoms (see Ref. 119 for review). For biological systems immersed in water, this technique also provides impressive resolution. Years of work produced high-resolution images of rhodopsin in native membranes that revealed a densely packed track of dimeric rhodopsin under various experimental conditions (Fig. 3).120,121 This result was validated by a number of complementary biochemical and biophysical techniques.122–124 Indeed, postdoctoral fellow Jastrzebska125 demonstrated that rhodopsin's oligomeric arrangement is sensitive to the concentration and nature of detergents, but that under mild conditions a row of rhodopsin dimers can be isolated. This finding is consistent with the oligomeric structures of many, if not all GPCRs.126 A theoretical model has been generated but remains to be verified experimentally (Fig. 3).99 As shown by cross-linking studies, one interface can be formed through an asymmetric dimer-dimer interaction mediated by helix I and helix 8 contacts that is present in native membranes.127 Periole and colleagues128 (Rockefeller University) also employed coarse-grain molecular dynamics to provide evidence for self-assembly of rhodopsin in membranes. The affinity between two opsin molecules as measured by Kd is ~10−5 M.129 Thus, considering the 5 mM concentration of this receptor in disc membranes, most of rhodopsin should exist in an oligomeric state. This oligomeric structure of rhodopsin is likely to be essential for the maintenance of a stable disc structure. Another postdoctoral fellow, Park,130–132 took this project further by working with Daniel Muller's group (ETH Zürich, Switzerland) to discern the energetics of protein unfolding by using single molecule force microscopy. This technique is a variant of AFM, which can identify stable structural segments that join together to form a native protein. Experimental evidence for the functional relationships between rhodopsin dimerization and phototransduction, or rhodopsin transport and disc formation is still a goal of active research.

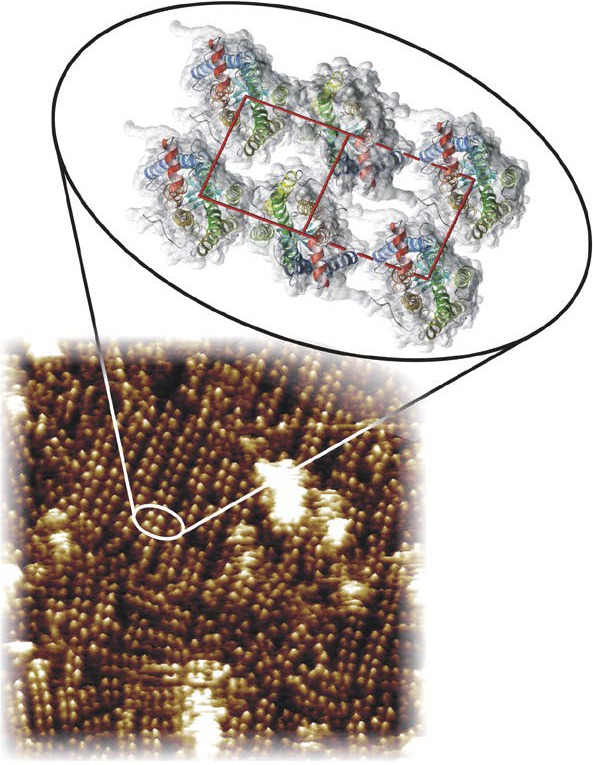

Figure 3.

Organization of rhodopsin in disc membranes. An AFM tomograph (tilted by 5°) shows the paracrystalline arrangement of rhodopsin dimers in a native disc membrane. The rhodopsin molecules protrude from the lipid bilayer by 1.4 ± 0.2 nm or one-fourth of their mass. Inset shows a model for the packing arrangement of rhodopsin molecules within the paracrystalline arrays in native disc membranes (PDB accession code: 1N3M).99 Helices of rhodopsin are colored as follows: helix I in blue, helix II in light blue, helix III in green, helix IV in light green, helix V in yellow, helix VI in orange, and helix VII and cytoplasmic helix 8 in red. The red box shows the close contacts between four molecules of rhodopsin. The dashed-line rectangle shows the longer contacts with neighboring dimers of rhodopsin. The native membrane structure and the molecular model of rhodopsin are reproduced from Liang Y, Fotiadis D, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Palczewski K, Engel A. Organization of the G protein-coupled receptors rhodopsin and opsin in native membranes. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:21655–21662. Copyright © 2003 The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc.; and Fotiadis D, Liang Y, Filipek S, Saperstein DA, Engel A, Palczewski K. Atomic-force microscopy: rhodopsin dimers in native disc membranes. Nature. 2003;421:127–128, with permission from the American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and Nature Publishing Group.

In retrospect, it would make sense that rhodopsin would arrange into higher order oligomers because it exists at high concentrations in discs. The density of rhodopsin in native rod discs can be estimated on the basis of the amount of rhodopsin in the retina and, more specifically, in the rod outer segments, in conjunction with the size of the rod outer segment and the number of lipid molecules per one molecule of rhodopsin (approximately 60; see Ref. 133 for review). Given that the mouse retina contains ~6.4 × 106 rods, the number of discs per retina is ~5 × 109. Consequently, the total amount of rhodopsin per eye is ~650 pmoles or 650 × 10−12 moles × 6.022 × 1023 molecules/mole = 3.96 × 1014 rhodopsin molecules. Thus, there are ~8 × 104 rhodopsin molecules packed per disc. This high density is only somewhat lower than that in 2D crystals of rhodopsin. Such a density leaves two options: rhodopsin is either organized in a highly ordered arrangement or there is a well-developed repulsion system that allows rhodopsin to remain monomeric while surrounded by less than two full belts of phospholipids. The existence of such a hypothetical repulsion system is questionable because the hydrophobic transmembrane segment of rhodopsin lacks charged residues. Charged amino acids are located exclusively at the interface of the membranes and water.

Another push in the imaging technology was our work spearheaded by Nickel from the laboratory of Baumeister and Paul Park97 once again. We used cryoelectron tomography to visualize the detailed morphology of the rod outer segment from the retina of mice in three dimensions. This new technique for vision research allowed us to preserve the structure of rod outer segments because the native tissue was quickly frozen in liquid ethane without any ice formation, thus preserving the sample under the most native conditions. Vitrified rod outer segments were among the largest structures imaged by this tomographic technique. We demonstrated the existence of spacer structures connecting adjacent discs that provided an accurate framework for the space within which phototransduction occurs. Several years later, the same technique was employed to image the connecting cilium.134

Proteins Interacting With Rhodopsin

In rod outer segments, rhodopsin interacts with four proteins involved in phototransduction.135 Rhodopsin couples with transducin following photoactivation. With a molar ratio to rhodopsin in rod outer segments of approximately 1:10, transducin is the second-most abundant membrane-associated protein of this structure. Although it is possible that rhodopsin and transducin are precoupled, this nonproductive complex would not permit nucleotide exchange on the α-subunit of transducin.133 Transducin was the first phototransduction protein to be crystalized in different subunit states.136–139 A few dozen transducin molecules are activated by a single photoactivated rhodopsin.1,140

Interaction between rhodopsin and transducin has been studied by a number of biophysical techniques.2,133,141,142 However, isolation of the rhodopsin-G protein complex was a major accomplishment. Jastrzebska143 was the first to isolate the rhodopsin-transducin complex in solution and determine its structure by negative-stain EM. Both her biochemical and structural data were consistent with a pentameric assembly of the photoactivated rhodopsin-transducin complex.144–146 Each rhodopsin monomer within this complex plays a different structural role, as revealed biochemically.147 This complex was detergent-sensitive, and upon increasing the concentration of n-dodecyl-β-D-maltoside from 1 to 5 mM,145 one of the two rhodopsin monomers dissociated suggesting that they cooperate to form a dimer by hydrophobic interactions. Understanding the molecular changes that occur within transducin during this nucleotide exchange was also advanced by recent studies.148–150 Another protein that recognizes photoactivated rhodopsin is rhodopsin kinase or GRK1.12,47 In mice, GRK1 is expressed in both rod and cone photoreceptor cells.12 Lack of this protein causes Oguchi disease, congenital stationary night blindness, associated with fundus discoloration and a profound decrease in dark adaptation.151,152 As a postdoctoral fellow (in Hargrave's laboratory University of Florida), I purified this enzyme from bovine retina and extensively characterized its properties.153–155 This was a challenging project because rhodopsin kinase is farnesylated and methylated at a Cys residue in the C-terminus causing the protein to stick to membranes and hydrophobic surfaces.156 The enzyme was sequenced and cloned in collaboration with Lorenz157 from the Lefkowitz group (Duke University). Many years later, it was crystallized by (reviewed by Homan and Tesmer158) Singh et al.159 (University of Michigan; Fig. 4A), revealing that its main structural domain is related to those of several other GRKs in the human genome. A cone variant of rhodopsin kinase, G protein–coupled receptor kinase 7, is expressed in several vertebrate species, including humans.160–162

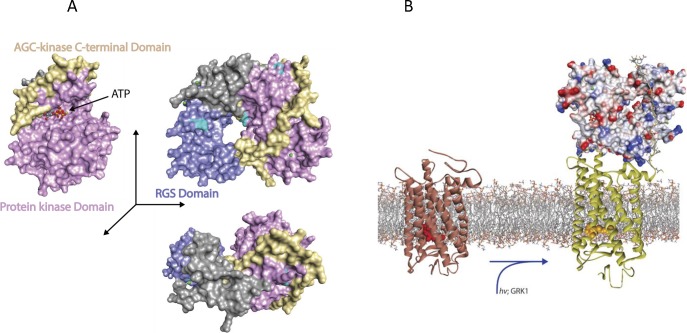

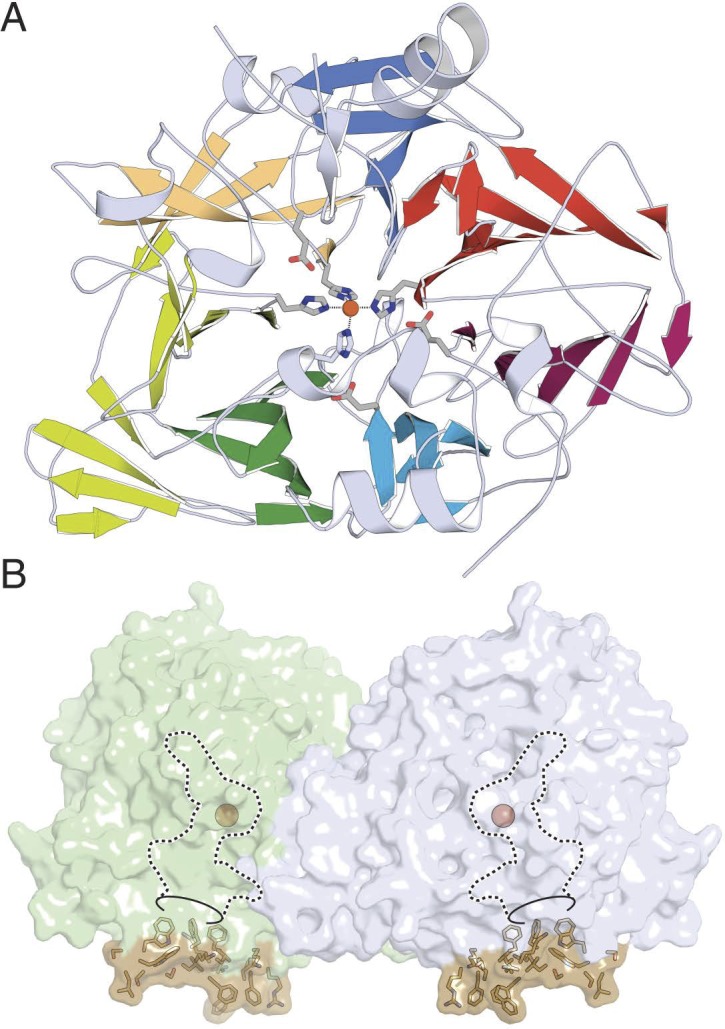

Figure 4.

Structure of rhodopsin kinase (GRK1) and phosphorylation of rhodopsin. (A) Overview of GRK1 with bound ATP (PDB accession code: 3C4W).159 The structural domain of regulators of G protein signaling is colored blue, the protein kinase domain violet, and the AGC-kinase C-terminal domain yellow. Atoms of the substrate ATP are shown as spheres. (B) Conceptual model of GRK1 docked to monomeric activated rhodopsin. Rhodopsin (PDB accession code: 1U19)300 is activated by light (PDB accession code: 3PQR)74 and only then does GRK1 bind to the cytoplasmic surface of the receptor. G protein–coupled receptor kinase 1 is rendered as molecular surface, rhodopsin as a bundle of transmembrane helices with connecting cytoplasmic and intradiscal loops. The active site of GRK1 could have access to the C-tail of a neighboring unactivated rhodopsin (not shown) in dimeric or oligomeric forms, allowing phosphorylation of an additional nonactivated rhodopsin in rod outer segments (high-gain phosphorylation).301

We have concurrently studied rhodopsin phosphorylation in vitro and in vivo with a relatively novel application, namely mass spectrometry (MS).163,164 Photoactivated rhodopsin can be phosphorylated at multiple sites because the recognition domain of GRK, which is essential for binding to the core of the helical bundle of rhodopsin, is separated from the active site that binds the C-terminal peptide of rhodopsin (Fig. 4B).165 The C-terminal peptide of rhodopsin that contains all its phosphorylation sites binds to the kinase active site with low affinity165 and, because of their proximity, it is phosphorylated at multiple different sites, though Ser336, Ser338, and Ser343 are preferred.166,167 Kennedy et al.167 expanded this work by correlating rhodopsin phosphorylation with visual cycle processes and dark adaptation. By regulating the life-time of individual rhodopsin molecules, these multiple phosphorylation sites are essential for reproducible and accurate single-photon responses of rod photoreceptors.168,169

Once rhodopsin is photoactivated and phosphorylated, it binds arrestin.170 During purification, we also noted that bovine retina has a shorter form of arrestin, called p44, that differs by replacement of the C-terminal tail of arrestin with a single amino acid.171–173 This form arises from alternative splicing of the gene.173 Importantly, p44 binds to photoactivated rhodopsin without phosphorylation.171 From this and other biochemical assays, it was proposed that the C-terminal part of arrestin blocks access to photoactivated rhodopsin unless it is dislodged by the phosphorylated C-terminal domain of rhodopsin.174,175 This mechanism and the identified bipartite structure of arrestin appear to be consistent with subsequent x-ray crystallographic studies.176–178 Arrestin interacts with clathrin adaptor protein 2, regulating survival of photoreceptors in mice.179 Similar to rhodopsin kinase mutations, mutations in arrestin are associated with Oguchi disease. Interestingly, cone cells express a different variant of arrestin called cone arrestin or arrestin 4.152

Finally, phosphorylated rhodopsin needs to be dephosphorylated. The phosphatase involved in the visual system is protein phosphatase 2A, identified by biochemical isolation and characterized with a specific inhibitor.50,51 For effective deactivation of rhodopsin, phosphatase 2A should not act on phosphorylated active rhodopsin. Arrestin prevents such reactivation by blocking the dephosphorylation of photoactivated and phosphorylated rhodopsin until the spent all-trans-retinal chromophore is released or until rhodopsin is regenerated. Although phosphatase 2A is a ubiquitous phosphatase, it remains to be determined which one of its two catalytic subunits encoded by two different genes is involved in catalyzing rhodopsin dephosphorylation. This problem could possibly be resolved by genetic approaches.

Guanylate Cyclases and Their Regulators

Two major soluble messengers in photoreceptor cells are Ca2+ and cGMP. With the discovery of cGMP as the second messenger of phototransduction, there remained the question of how Ca2+ affects this process, even though electrophysiological measurements clearly indicated its role.180 Koch and Stryer181 (Stanford University) made the fundamental discovery that Ca2+ affected guanylate cyclase (GC) activity in biochemical assays (Fig. 5A). Moreover, it appeared that this regulation was mediated by soluble Ca2+-binding proteins (CaBPs). The fact that higher GC activity was observed at low Ca2+ concentrations (as with light-exposed photoreceptor cells) was especially unusual for biological signaling. This behavior contrasts with that of the typical and ubiquitous Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin, which affects its targeted effector molecules only when loaded with Ca2+.182 Initially, a Ca2+-binding protein called recoverin was proposed to fulfill this GC regulatory function,183 but neither recombinant recoverin nor highly purified preparations of native recoverin displayed any activity.184,185 Instead, recoverin was later proposed to play a role in regulating rhodopsin phosphorylation or synaptic transmission.186 The putative activator of GC was left unidentified. Isolation of the putative GC regulator was extremely challenging. First, it was difficult to accurately measure GC activity. This problem occurs because GC activity is lower by an order of magnitude than that of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) phosphodiesterase (PDE), which quickly hydrolyzes cGMP. This difficulty is exacerbated further because bovine retina obtained from a slaughterhouse has already had a significant fraction of rhodopsin bleached (up to 10%), which further activates PDE. The second major problem is that soluble factor(s) in rod outer segment extracts are unstable. Additionally, it appeared that the protein(s) was inactivated by aggregation or irreversible binding to virtually any surface. These major obstacles made purification of the GC activator difficult if not impossible. We solved the first problem by using thio-α–guanosine triphosphate (GTP) as a substrate for GC.187 The resulting product was cyclic-thio-GMP, which is resistant to hydrolysis by PDE. The second problem was overcome by a herculean effort, assaying thousands of samples under different conditions in a shoulder-to-shoulder collaboration with my postdoctoral fellow colleague, Gorczyca.188 The protein we isolated had the expected properties, and therefore we called it guanylate cyclase-activating protein (GCAP). It was quickly cloned in collaboration with W Baehr (Baylor College of Medicine and later University of Utah).189 A bacterially expressed fragment of GCAP was also obtained as a source for developing a monoclonal antibody that recognized both GCAP and a second factor called GCAP2 in the retina.190 Dizhoor et al.,191 in the J Hurley laboratory (University of Washington), independently purified GCAP2 by an alternative method. Molecular cloning and genomic analysis revealed GCAP3 in the human genome and many other GCAPs in lower vertebrates.192,193 Such GCAPs also could play roles in either rod or cone functions depending on their localization.

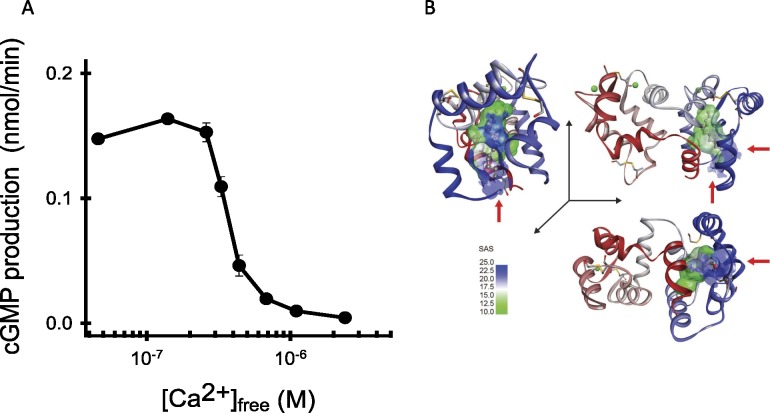

Figure 5.

Regulation of GC in photoreceptors. (A) Sensitivity of GC to physiological concentrations of free Ca2+ in rods and cones. (B) Structure of myristoylated GCAP1 in three orientations (PDB accession code: 2R2I).201 The N-terminal domain is colored blue (EF-hand 1 and EF-hand 2) and the C-terminal domain is red (EF-3 and EF-4). Ca2+ ions and the myristoyl groups are shown as dark-green spheres and green space–filling shapes, respectively. The surface is made semitransparent to reveal the buried myristoyl group. Red arrows point toward the myristoyl group. SAS, solvent accessibility surface.

At the end of the 20th century, advances in genome sequencing of mammalian species allowed us to identify many other Ca2+-binding proteins. Subsequent cloning efforts yielded a family of CaBPs, eight in total, that are related to GCAPs and calmodulin.194–196 The most studied, CaBP4, is specifically expressed in photoreceptors where it localizes to synaptic terminals and regulates L-type Cav1.4 channels, specifically the Cav1.4 α1-subunit, shifting the activation of Cav1.4 to hyperpolarized voltages in transfected cells.197 The phenotype of mice lacking CaBP4 is similar to incomplete congenital stationary night blindness in humans.198 Nuclear magnetic resonance structures of CaBP1 were determined for both Mg2+-bound and Ca2+-bound states and their structural interactions with the inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate receptor fragment.199,200

Today, we have the crystal structures of GCAP1 with its hydrophobic myristoylated tail (Fig. 5B),201 GCAP2,202 and GCAP3,203 all in their Ca2+-bound forms. Thus, it would be desirable to solve the structure of Ca2+ free GCAP, which is the active state. A vast number of reports have described the biochemical properties of these and other neuronal Ca2+-binding proteins.196 Mouse models have revealed the critical function of both GCAP1 and GCAP2 in phototransduction.15 Human cone-rod dystrophy can be caused by mutations in the GCAP1 gene.204 Along with these studies, key advances were also made in the molecular characterization of membrane-bound GC1 and GC2.205–207 However, no structural data on retinal GCs are yet available, thus we can make only rudimentary speculations about their interactions with GCAPs. It remains unknown how Ca2+ dissociation changes the conformation of GC-GCAP complexes, and how GCs are specifically activated by GCAPs.

Restoration of Photoactive Visual Pigments: the Retinoid (Visual) Cycle

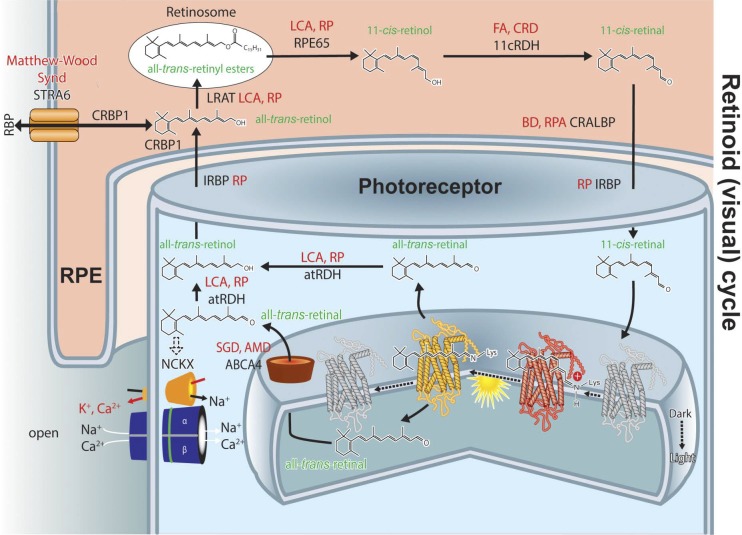

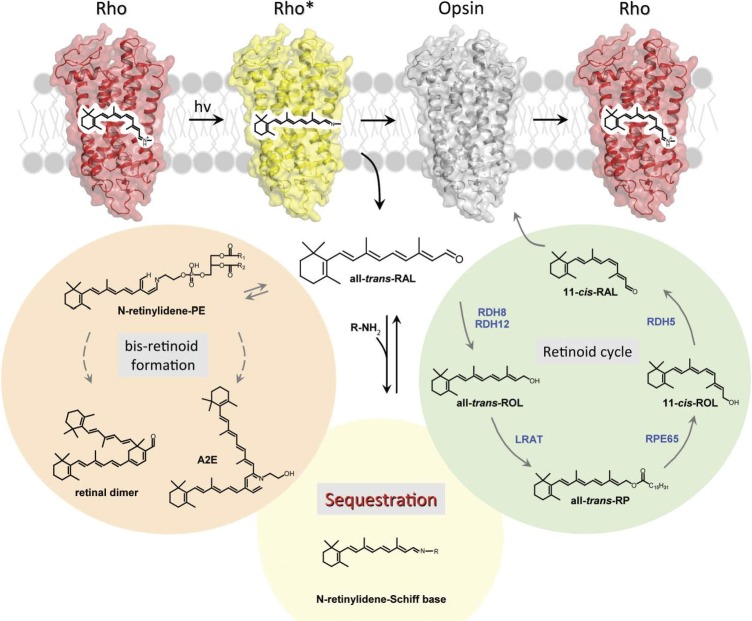

Equally important to phototransduction is the mechanism that allows resetting to dark conditions after light stimulation. Rhodopsin and other visual pigments are first inactivated by the action of rhodopsin kinase and arrestin (its different spliced forms), but eventually photoactivated rhodopsin needs to be returned to its inactive dark state (Fig. 1). The all-trans-retinal released from photoactivated rhodopsin must be converted back to 11-cis-retinal. This metabolic transformation, termed the retinoid (visual) cycle, occurs in the photoreceptor cells and the adjacent RPE (Fig. 6). Philip Kiser et al.,16 recently reviewed this process in detail and here I will emphasize just a few key points.

Figure 6.

The visual (retinoid) cycle. This metabolic renewal of 11-cis-retinal takes place in photoreceptor outer segments and the RPE. First, all-trans-retinylidene is hydrolyzed from opsin and all-trans-retinal diffuses to the cytoplasmic side where it is reduced to an alcohol by membrane associated all-trans-retinol RDH. Lack of adequate RDH activity can lead to LCA (or RP); all diseases are depicted in red letters. A fraction of all-trans-retinal is released into the intradiscal side. There all-trans-retinal and phosphatidylethanolamine form a Schiff base and together are transported into the cytoplasmic side via ABCA4. Lack of ABCA4 transport activity is associated with Stargardt disease, whereas polymorphisms in this gene are associated with AMD. Retinol diffuses from the cytoplasm to the RPE where it becomes esterified by LRAT to form fatty acid retinyl esters. Such esters have a propensity to coalescence, thermodynamically driving the transfer from photoreceptor to RPE cells. The esters then serve as substrates for the isomerization reaction catalyzed by the 65-kDa protein, RPE65. The resulting product, 11-cis-retinol, is oxidized to 11-cis-retinal by the 11-cis-retinol specific RDH5 and dual specificity (cis and trans-retinols) RDHs, including RDH10; 11-cis-retinal diffuses back into the photoreceptor outer segments, a process thermodynamically driven by the formation of stable visual pigments. Essential for transporting and protecting these retinoids are intracellular and extracellular retinoid-binding proteins such as CRALBP, CRBP1, IRBP and retinol-binding protein 4 (RBP4). Inactivating mutations in the LRAT and RPE65 genes are causes of childhood blindness because these genes are nonredundant, whereas mutations in RDHs and retinoid-binding proteins have less severe effects but can be associated with RP, cone-rod dystrophy, fundus albipunctatus, fundus albescens or Bothnia dystrophy. Retinoids are retained in the eye as a result of LRAT activity. In the bloodstream, retinoids are bound to RBP4 and then enter the eye by passive transport with the help of STRA6. Mutations in the STRA6 gene cause Matthew-Wood Syndrome, a severe disease that includes obesity and mental retardation, as well as faulty eye development and blindness, indicating the importance of STRA6 for retinol transport into the brain and eye.

Our general contribution to this area of vision research is multifold. We have applied rigorous chemical analyses together with novel animal models that serve as in vivo tests wherein both the retina and RPE are naturally kept together, eliminating many artifacts associated with isolated retina or the RPE from cell culture. This work has been supported by analytical and spectroscopic analyses as well as modern electrophysiological and imaging techniques. Moreover, we have used both high- and low-resolution methods of structural biology to gain insights into pivotal steps of isomerization, retinol esterification, and properties of retinoid-binding proteins.24,208–233

The photoisomerized all-trans-retinal chromophore is released into the cytoplasm, where it is reduced to the corresponding alcohol by retinol dehydrogenases (RDHs).16 However, a fraction of all-trans-retinal in rods escapes into the intradiscal space. Within the rims of discs resides the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter member 4 (ABCA4) transporter from the ABC transporter superfamily.234,235 This protein transports all-trans-retinal and the excess of 11-cis-retinal that is unbound to opsin in the form of lipid conjugates (N-retinylidene-phosphatidylethanolamine).234,235 A postdoctoral fellow, Tsybovsky,236 provided the first glimpse into the molecular organization and functional rearrangements of this protein by using EM and single-particle reconstruction to obtain an 18-Å resolution structure. Notably, significant conformational changes in the cytoplasmic and transmembrane regions of ABCA4 were observed upon binding of a nonhydrolyzable ATP analog. Lack of functional ABCA4 causes toxicity due to accumulation of free retinals, which leads to production of retinal adducts, including N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine (A2E). In humans, this abnormality is characteristic of a juvenile form of macular degeneration called Stargardt disease.237

Retinoids also undergo redox reactions catalyzed by a number of enzymes such as short-chain retinol dehydrogenases (SDR) and alcohol dehydrogenases.238,239 Postdoctoral fellow Maeda, used genetic approaches to identify specific enzymes involved in the redox reaction process.239 This work continues today because of the number of overlapping and redundant activities found. Several key enzymes were identified: RDH8, a photoreceptor outer segment enzyme; retSDR, an abundant cone protein; RDH12, an inner segment enzyme; RDH5, which is a specific 11-cis-retinol RDH; RDH11 in the RPE; and several others.239,240 Based on genetic work in mice, it appears that other dehydrogenases are also involved in the full retinoid cycle.223 Perhaps another extremely important candidate is RDH10; further advancement in elucidating the role of this enzyme in the retinoid cycle is expected.

Retinoids are delivered from the circulation either in chylomicrons or bound to the protein RBP4. The main transport mechanism into cells involves stimulated by retinoic acid 6 (STRA6) receptors identified by Kawaguchi and colleagues (University of California Los Angeles).241 This transport does not require ATP, but rather an intracellular enzyme called lecithin:retinol acyl transferase or LRAT242,243; LRAT is highly expressed in stellate cells of the liver and in the RPE, the main reservoir for esterified retinol. In the RPE, LRAT functions to trap retinol from the circulation and from photoreceptors after bleaching; LRAT reduces the intracellular retinol concentration, which then drives the uptake of retinol by STRA6. Once esterified, fatty acid retinyl esters have a high propensity to form intracellular lipid droplets called retinosomes. First identified by a postdoctoral fellow in my laboratory, Imanishi, these structures were further characterized in subsequent studies.244–248 The first insights into the mechanism of esterification on a structural level came from the work of Golczak (Fig. 7).249,250 Another former fellow, Moise, also solved the structure of an LRAT-related protein in an independent study.251 Lack of LRAT or STRA6 causes severe abnormalities in humans. Inactivating mutations in the LRAT gene lead to Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA).252 Moreover, mice lacking this enzyme cannot store retinoids and are blind.253,254 Mutations in STRA6 also cause developmental abnormalities including microophthalmia (known as Matthew-Wood syndrome255–258). Importantly, treatment with pharmacological doses of vitamin A can restore vitamin A transport across these barriers and rescue the vision of Stra6−/− mice.259

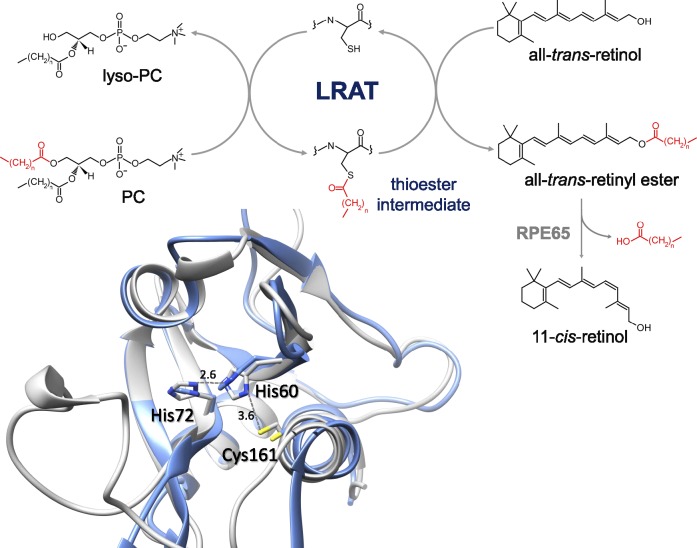

Figure 7.

Enzymatic mechanism of LRAT and the architecture of its active site. Transfer of an acyl moiety from phospholipid onto vitamin A occurs in two catalytic steps. The acyl moiety is first transferred onto a catalytic Cys residue forming a thioester. This thioester is then cleaved by a nucleophilic attack from retinol's activated hydroxyl group causing subsequent formation of the final retinyl ester product and restoration of the LRAT active site. A model of the human LRAT catalytic domain based on a LRAT/HRASLS3 chimeric protein reveals that the overall structure of the catalytic domain resembles the archetypical α/β fold of a NlpC/P60 protein. The architecture of the LRAT active site (blue) shows the positions of key residues involved in catalysis in relation to the native HRASLS3 protein depicted in gray (PDB accession code: 4DOT).250 The catalytic Cys161 residue is located at the N-terminus of a helix packed against a core of β-sheets containing the conserved His60 and His72 residues.

The heart of the chromophore regeneration pathways lies in the isomerization of all-trans-retinyl esters to 11-cis-retinol.260–262 My laboratory first observed that only a subset retinyl esters (or another speculated intermediate) participate in this reaction, but there was also a large storage fraction.263 The process has yet to be fully elucidated, but it appears that retinyl esters within the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), not retinosomes, participate directly in the reaction.264 However, retinosomes could constitute dynamic storage vesicles for the esters. A previously well-known protein without an assigned biochemical function, RPE65, was later identified as the visual cycle retinoid isomerase by three independent groups.260–262 Retinoid isomerization and enzymatic oxidative cleavage of carotenoids are catalyzed by a family of evolutionarily conserved, nonheme iron-containing enzymes named carotenoid cleavage oxygenases. Even though the reaction catalyzed by RPE65 does not represent oxygenase activity, RPE65 belongs to this family.16,265 Kiser,218,266 a former graduate student and now a junior faculty member in the Department of Pharmacology at Case Western Reserve University, took up the challenge of crystalizing this protein from native bovine RPE (Fig. 8), an immense feat that revealed the mechanism of isomerization catalyzed by this protein. The basic RPE65 structural motif is a seven-bladed β-propeller, with the catalytic Fe2+ located in the center of the protein. Two structures of RPE65 were determined in its lipidated and delipidated forms.216 Our data strongly support retinoid isomerization due to the Lewis acidity of iron that promotes ester cleavage via alkyl-oxygen bond scission to release the acid and generate a resonance-stabilized carbocation intermediate, with eventual production of the 11-cis-retinol product.264 Previous biochemical studies of RPE65, combined with a proper structural context helped to reveal the mechanism of isomerization more than any of the studies separately.16,264 This area of research is still very active because it concerns the fundamentals of catalytic isomerization. Mutations in RPE65 are known to be responsible for LCA.267 Mice lacking this enzyme recapitulate the human condition.268 Moreover, animal studies of this mutation were critical in developing several promising therapies.214,269

Figure 8.

Crystal structure of RPE65. (A) Cartoon representation showing the beta-propeller fold of RPE65. The catalytic iron, located on the propeller axis, is coordinated by four conserved histidine (His) residues. Three second sphere Glu residues are also important active site components. Residues of Glu and His are shown in stick representations. (B) Dimeric structure of RPE65. The hydrophobic patches that mediate RPE65 membrane association (brown) are oriented in parallel. The entrance to the active site cavity (dashed black lines) is surrounded by residues comprising the hydrophobic patch (PDB accession code: 4F2Z I).266

Retinoids need to be shuttled between different organelles and protected from isomerization, oxidation, and condensation.228,270 Thus, key retinoid-binding proteins are critical for maintaining proper retinoid isomeric and oxidation states. Cellular retinaldehyde–binding protein (CRALBP) in the RPE and Müller cells, and extracellular interphotoreceptor retinoid–binding protein (IRBP) are two major carriers involved.16 The structure of CRALBP—with its unanticipated isomerase activity—has been elucidated,271–273 whereas the structure of IRBP has only been partially characterized.274 Inactivating mutations in either one of these binding proteins can cause retinal degenerative disease.275,276

Phototransduction and Retinoid Cycle: Separate or Together?

Experimentally, phototransduction and the retinoid cycle have typically been investigated in separate contexts. However, these processes are functionally linked and should not be considered as separate signaling and metabolic transformation entities (Supplementary Fig. S1). For example, when measuring cellular electrophysiological responses of rods and cones, photoreceptors typically are removed from the surrounding RPE. Additionally, little attention is paid to the fact that although retinol and retinal coexist in a redox equilibrium, only the aldehyde causes activation of opsin and is cytotoxic. Conversely, just a few minutes after death, the retinoid cycle largely ceases to function in dissected eyes. Thus, even though the structures of both the retina and RPE are intact, the cells cannot produce 11-cis-retinal. Indeed, this two-cell system that evolved from primordial photoreceptor and helper cells, still poses many experimental challenges. Therefore, it is critically important to consider the two processes, phototransduction and the retinoid cycle, as biologically fully integrated (Supplementary Fig. S1).

All of our molecular studies have led to a better mechanistic understanding of the system, which in turn has provided insights into targeted therapeutic strategies that we are now testing and developing to enter the clinical sphere.

Multiphoton Imaging of the Retinoid Cycle in Vision

It is hard to believe that just a few years ago researchers and ophthalmologists did not have imaging techniques such as optical coherence tomography and scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (SLO) available at their practice. Even more recently, new techniques for imaging retinoid cycle intermediates were developed based on the nonlinear optical process, two-photon (2PO) excitation. The low energy of light (i.e., red to infrared) used in such techniques is less damaging, produces less noise, and results in improved penetration into the eye compared with conventional imaging modalities. These novel technological breakthroughs can be applied for clinical purposes as well.

In previous sections, I described the technological advances used to reveal fundamental molecular properties of the visual system. In this section I will link these new technologies to translational research. For in imaging the retina using 2PO, we had three important advantages: (1) the prior use of 2PO excitation microscopy for the discovery of retinosomes 244,245; trans-scleral imaging allowing high-resolution images of RPE and other cell types; (2) the simultaneous visualization of multiple fluorescent molecules; and (3) no need for contrast enhancing agents as the natural fluorescence of retinoid derivatives allows retinal imaging.16 But scientists continued to make progress, and I was lucky here because of the engineering contributions of Palczewska24,277 (Polgenix, Inc., Cleveland, OH, USA); and productive collaborations with many investigators including J. Hunter and D. Williams (University of Rochester) and David Piston (Vanderbilt University)24,277 now allows imaging of fluorophores in living mammals including primate eyes. Although the fluorescence quantum yield of retinols and retinyl esters is low, they can easily be visualized due to their high localized tissue concentrations (Fig. 9). Combining imaging with genetics and spectrally sensitive detectors allowed us to further characterize the structures of retinosomes. Mice without the Lrat gene cannot synthesize retinyl esters, and consequently they lack retinosomes. Mice without the Rpe65 gene cannot transform retinyl esters to 11-cis-retinal; thus they have inflated retinosome-like structures full of retinoids.24 Retinosome fluorescence increases or decreases as a function of rhodopsin activation and retinoid cycle enzyme activities, and thus this provides a measure of photoreceptor-RPE function. The enlarged retinosomes can even be imaged by 3-photon excitation, providing a way to visualize retinoid dynamics at longer wavelengths of light (~1 μm).24 Mice carrying the double gene deletions Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− feature a massive accumulation of retinal condensation products in the retina, including A2E. These condensation products are readily visible because their fluorescence quantum yield is extremely high compared with that of retinol. Moreover, the ratio between condensation products and retinosomes increases with age in mice, suggesting that this could be a good indicator of aging processes, Stargardt disease or AMD.24

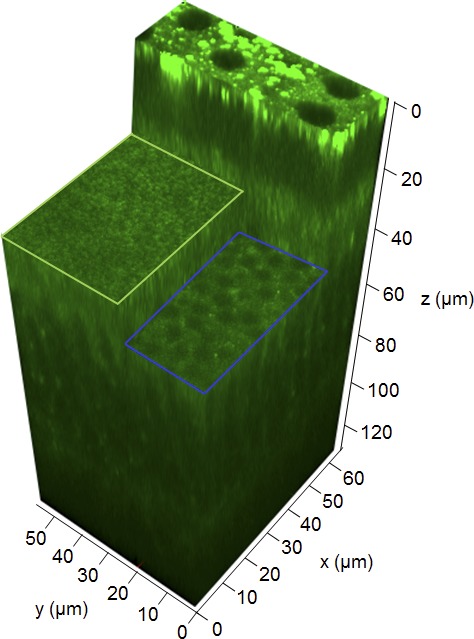

Figure 9.

Three-dimensional 2PO microscopic image of a retina and RPE in the intact eye of a 5-month-old C57BL/6J-Tyrc–2J mouse. The retinal pigmented epithelium is at the top of the image at z = 0 μm. A section through the retinal inner segments outlined by the light-green rectangle is shown at a location 30 μm away from the RPE. Another section through the outer nuclear layer outlined in blue is shown at a location 40 μm away from the RPE. Images were obtained with a 730-nm excitation wavelength.

Two-photon imaging allows noninvasive in vivo tracking of photoreceptor degeneration events in the presence and absence of pharmacological intervention. We also have used 2PO microscopy with 3D reconstruction methodology for the first time to observe damage to photoreceptors subjected to intense light in mice (Fig. 9).21 After such exposure, we found that retinoid-derived fluorescence increased strongly in rod outer segments along with a 3-fold expansion of these structures in Abca4−/− Rdh8−/− mice. In addition, infiltrated macrophages cleared the disrupted rod outer segment membranes. Transfer of both the fluorophores and membranous material required active phagocytosis. These exciting findings demonstrate that with respect to light-induced retinal degeneration in mice, the outer segments of rod photoreceptor cells are the primary sites of degeneration. Changes in photoreceptor cells were followed by secondary changes in the RPE.21 The use of a noninvasive 2PO imaging approach to assess the effectiveness of novel treatments for retinal degeneration is exemplified by recent reports. As discussed in more detail below, these advances have included the sequestration of toxic free all-trans-retinal,278 application of a systems pharmacology approach to treat retinal degeneration,279 rescue of vision by 9-cis-retinoids,212 and implantation of human induced pluripotent stem cells in mice with a defective RPE.211 We expected that as 2PO imaging matures, this technology will be extremely useful in drug discovery and development in small animal models (see Ref. 209 for review).

Recently we reported that multiple fluorophores can be repetitively and safely visualized by 2PO fluorescence through the front of the eye in live mice.280 Improvement in instrumentation, inclusion of dispersion compensation, image metrics feedback-based adaptive optics (AO) and development of a data acquisition algorithm led to identification of retinosomes and condensation products in the RPE by their characteristic localization, fluorescent spectral properties, and their absence in certain genetically modified or drug-treated mice.280 Sharma et al.281 imaged retinal ganglion cells tagged with an extrinsic label in the living mouse eye using a 2PO fluorescence AO-SLO, providing further evidence that measuring a functional response from various cell types is feasible. Next, using a chemical analysis that combined high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and MS, we measured the content of different fluorescent retinoids in monkey and human eyes to validate the potential of 2PO imaging for monitoring retinoid changes in human eyes.277 Moreover, based on emission at 480 nm, ex vivo images of inner and outer segments of rods and cones were obtained in primate eyes at different eccentricities. These results clearly indicate that human retina contains sufficient amounts of fluorescent retinoids for 2PO excitation imaging.277 Hunter and colleagues26 used a 2PO fluorescence AO-SLO to obtain fluorescent images of the macaque cone mosaic. Here the strongest signal was derived from cone inner segments. It also was noted that the fluorescence response increased following light stimulation. The current challenge is to connect the changes in multiple fluorescent molecules to retinal function, namely to enable 2PO imaging not only to display the structures, but also to quantify the dynamics of biochemical and electrophysiological photoreceptor responses in human retina.

A noninvasive 2PO imaging approach also has the potential to detect and monitor early molecular changes triggered by AMD and other human blinding diseases related to defects in retinoid metabolism. So how do we transition from the ex vivo imaging of mouse eye and the in vivo noninvasive imaging of mouse and monkey eyes to an acceptable instrument for human retinal imaging? Most importantly, we anticipate that fully developed, 2PO excitation–based imaging could provide functional information about human vision so that prophylactic therapies could be developed that prevent visual deterioration and blindness. The future challenge will be to create a next generation instrument that can be safely used in humans. Improvements in software, use of better lasers, higher sensitivity detectors, and improved optics along with other elements, such as identification of fluorophores based on lifetimes and other spectral properties, should be implemented in the new device.

Pharmacological Therapy for Retinal Diseases

Along with elucidating the structures of retinal proteins and their macromolecular coassembly by various structural methods, we also have used animal models to test and advance our hypotheses. Many useful mouse models were either generated in my laboratory and/or imported from our colleagues at different institutions. Experiments with these mice not only allowed us to test and verify ideas about physiological processes and pathological chains of events, but also to provide proof-of-principle that some of our experimental therapies will produce useful drugs to combat human blinding diseases.58,214,282

Van Hooser,283,284 using mice obtained from Redmond268 (National Eye Institute), discovered that 9-cis-retinal can restore visual pigments in Rpe65−/− mice. Later another research assistant, Batten,253,254 obtained the same result with newly generated Lrat−/− mice. Multiple functional assays indicated that these mice had significantly improved vision. Similar results followed in a dog model that recapitulated human LCA.215,285 The oral delivery and metabolism of 9-cis-retinal has been extensively reviewed by Palczewski.214 This retinoid and its derivatives are far more chemically stable than 11-cis-retinal; yet isorhodopsin, formed between 9-cis-retinal and opsin, undergoes the same photochemical processes and phototransduction as does native rhodopsin (Fig. 10). This idea was advanced to phase II clinical studies with children suffering from LCA due to mutations in the RPE65 and LRAT genes (http://clinicaltrials.gov/show/NCT01543906 provided in the public domain by ClinicalTrials.gov, a service of the US National Institutes of Health).

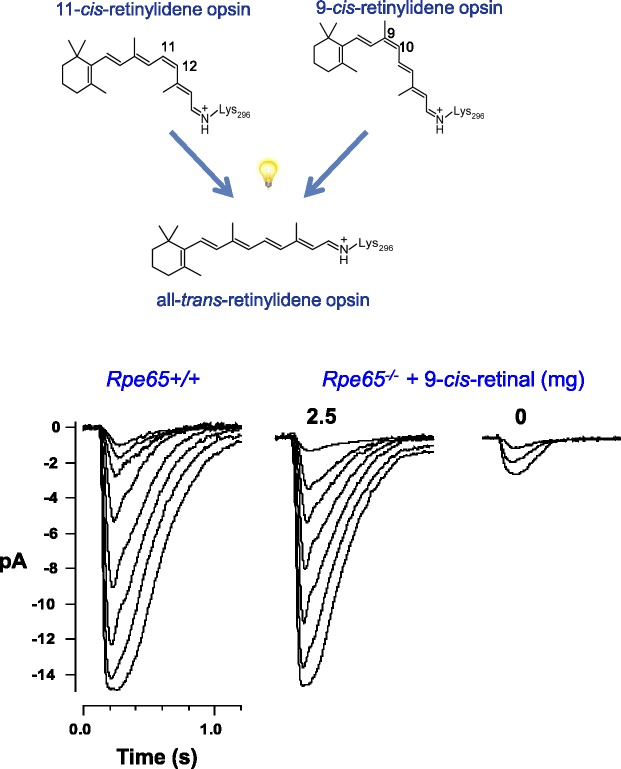

Figure 10.

Rescue of vision in LRAT- and RPE65-deficient mice. Above: Endogenous 11-cis-retinal bound to opsin (rhodopsin) can be replaced by 9-cis-retinal to form a functional pigment (isorhodopsin) that differs by only a 60% reduction in quantum yield and approximately a ~15-nm hypsochromic shift in maximal light absorption. These differences minimally affect vision. However, 9-cis-retinoids are chemically more stable than 11-cis-retinoids and can be pharmacologically formulated for use in the treatment of LCA; 11-cis-retinoids formed in situ in the eye are photo- and thermally unstable without protective retinoid-binding proteins. Both rhodopsin and isorhodopsin form active meta II rhodopsin intermediates. Below: stimulus response families for Rpe65+/+ or Rpe65−/− mice supplemented with 0 and 2.5 mg of 9-cis-retinal.283 Light flash (10 ms) strengths were increased in 2-fold steps from the dimmest intensity. Reproduced with permission from Van Hooser JP, Liang Y, Maeda T, et al. Recovery of visual functions in a mouse model of Leber congenital amaurosis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:19173–19182. Copyright © 2002 The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc.

We have demonstrated in many different experimental settings that free all-trans-retinal is perhaps the most toxic retinoid in the retina.24,278,286–289 When this aldehyde is not sequestered by binding proteins or rapidly reduced to retinol, it causes death to various experimental cells or degeneration of the retina in situ after exposure to intense light. The latter mechanism of degeneration could be operative in humans with Stargardt disease and AMD. We have provided evidence that retinal sequestration by newly developed and previously characterized primary amines can lower the level of all-trans-retinal and prevent accumulation of retinal condensation products, including A2E (Fig. 11).278,287 The mechanism involves temporary Schiff base formation between the aldehyde and amine that eliminates the toxic effect of retinal yet allows its release for reduction to retinol and reentry into the visual cycle when needed (Fig. 11).

Figure 11.

Preservation of retinal structure and function by sequestering excess all-trans-retinal. Once released from rhodopsin, all-trans-retinal can enter the retinoid cycle, form bis-retinoids such as A2E, or persist as a free toxic aldehyde that impairs multiple processes and leads to cell death. High levels of A2E are associated with Stargardt disease and AMD; A2E also accumulates with age without any obvious disease as evidenced by elevated fluorescent material in the eyes of healthy individuals. Treatment with primary amines that form a Schiff base can lower the excessive amounts of all-trans-retinal that accumulate in transgenic mice.278 The same strategy could be beneficial as a treatment for AMD and/or Stargardt disease. Reproduced from Maeda A, Golczak M, Chen Y, et al. Primary amines protect against retinal degeneration in mouse models of retinopathies. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:170–178; with permission from Nature Publishing Group.

Specifically, we started our search with Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved drugs that have some specific characteristics: (1) the chemical entity must contain a primary amine that can reversibly react with an aldehyde; (2) it must be delivered systemically to the eye and partition into membranes; thus, it would be a hydrophobic amine without charged groups such as a phosphate; and (3) it must have a good safety profile. It was especially important that drug can be tolerated at very high doses, because sequestration of the toxic retinal occurs by mass action. It was to our advantage that the selected test compounds primarily targeted infectious diseases, because such molecules are less likely to target human proteins. We avoided thiols and hydrazines, because thiols react with the retinal, producing a complicated mixture of condensation products and hydrazines react readily with ketones and aldehydes, displaying frequent toxicity.290 This last property could deprive eye of retinal, and cause problems with dark adaptation.278,287 Thus, only 24 compounds were tested in our mouse model of light-induced retinal degeneration. Further experimentation is ongoing to decide which of the tested compounds would best progress to clinical trial(s).

Modern drug discovery involves a long and challenging pathway to potential clinical application. We have investigated a transformative solution to this problem with a multidisciplinary systems pharmacology approach (Fig. 12).279,287 Systems pharmacology identifies and connects different biochemical signal transduction pathways that culminate in a common effector molecule/second messenger. G protein–coupled receptors—such as adrenergic, adenosine, or muscarinic receptors and 600 other GPCRs in the human genome282—play essential roles in cellular processes and are the most common types of receptors targeted by medications for disease treatment. An approach involving expression profiling on a genomic scale was used to guide the rational targeting of specific pathways, not only by combinations of novel therapeutics, but also combinations of currently existing FDA-approved drugs to combat complex diseases. This novel approach is also of interest to those pursuing mechanism-based pharmacological development of rational therapeutic strategies for treating disorders with complex etiologies (see Refs. 279, 287 for review; Fig. 12). Further development of systems pharmacology approaches is currently our focus for treating complex retinal diseases such as retinal degeneration from AMD and diabetic retinopathy.

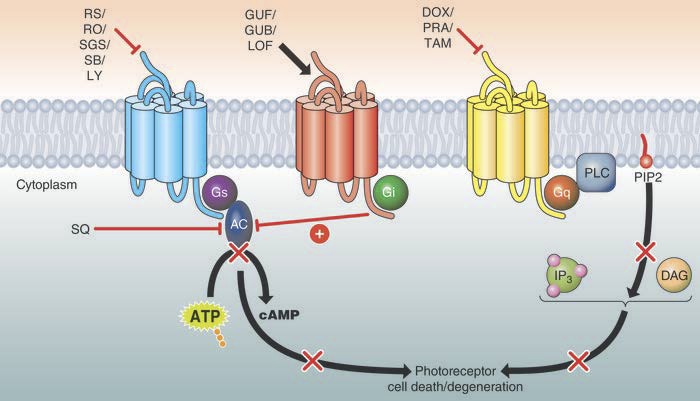

Figure 12.

Systems pharmacological strategies prevent the development of light-induced photoreceptor degeneration. In appropriate mouse models of human retinopathies, antagonists of multiple Gs-coupled GPCRs prevented photoreceptor cell death (red bar, top left). Moreover, pharmacological activation of Gi-coupled GPCRs (black arrow, top middle) that suppress adenylate cyclase activity (red bar, middle) preserved retinal structure and function against an environmental insult (prolonged exposure to intense illumination). Direct inhibition of AC was also beneficial (red line). Additionally, Gq-coupled GPCRs can participate in photoreceptor degeneration, and inhibition of these GPCRs also proved effective in protecting photoreceptors from light-induced degeneration (red bar, top right). Reproduced with permission from Chen Y, Palczewska G, Mustafi D, et al. Systems pharmacology identifies drug targets for Stargardt disease-associated retinal degeneration. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5119–5134. Copyright © 2013 American Society for Clinical Investigation.

Conclusions and Appreciations

Recent progress with next-generation DNA sequencing has opened many new avenues to complement the biochemical, structural biology, and imaging approaches to vision research. These methods will provide new insights into how photoreceptors are developed, organized, and postmitotically maintained. Work on miRNA spearheaded by postdoctoral fellow Sundermeier promises to contribute an even greater understanding of gene regulation in the coming years.291–294 Genetic analyses of retinas with varying cone-rod ratios and approaches to understanding physiological processes such as phagocytosis and pathophysiology of complex retinal diseases are being carried out by Mustafi and Kevany.295–298 These projects add a new dimension to current knowledge of fundamental processes required for mammalian vision that were either not accessible for study or limited by the shortcomings of conventional methodologies.291–298

Macular degeneration of the retina, in both juvenile and age-related forms, has multiple causes. Stargardt disease is an inheritable juvenile form that produces progressive vision loss and blindness, whereas the age-related form, AMD, probably results from the accumulated errors in biochemical pathways required for vision. A rational approach for early detection and successful therapy of this macular group of retinopathies is still lacking. In-depth genetic analyses followed by systems pharmacological approaches based on our understanding of cellular signaling networks and their molecular effectors that drive such degeneration offer a path to discovering critical targets for pharmacologic intervention. Fortunately, these efforts have already identified several cellular targets in human samples for potential drug therapy both under normal and diseased conditions.279 This undertaking represents a departure from classical pharmacology, involving combinatorial treatments with lower and safer doses designed to affect several cellular processes simultaneously to produce a desired therapeutic outcome. It is a well-kept secret that many scientific advances made in vision research transcend ophthalmology, promoting groundbreaking discoveries in other medical fields. The application of systems pharmacology to vision research has the potential to lead once again.

I have been extremely fortunate to be mentored by the best professors: Marian Kochman and Paul A. Hargrave. In turn, I have supervised over 90 students, postdocs, and technicians. More than 25 of them are already pursuing independent careers. Furthermore, our studies would not have achieved the levels they have without a group of outstanding collaborators, and many of their names are in the extensive reference list. None of these achievements would have been possible without the generous support of the University of Washington, Case Western Reserve University, Research to Prevent Blindness, and Foundation Fighting Blindness. But, my biggest thanks go to the National Eye Institute for its continuous and substantial support.

Acknowledgments

We thank Leslie T. Webster Jr, Akiko Maeda, Paul Park, Marcin Golczak, John J. Mieyal, Yoshikazu Imanishi, Andreas Engel, Arthur S. Polans, and the members of Palczewski's laboratory for their comments on this manuscript. We thank Lukas Hofmann, Marcin Golczak, Grazyna Palczewska, David Salom, Andreas Engel, Philip Kiser, and Yu Chen for figure preparation.

Supported by funding from the National Eye Institute, National Institutes of Health Grant R01EY008061 (KP), and the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Foundation.

KP is the John H. Hord Professor of Pharmacology.

Disclosure: K. Palczewski, None

References

- 1. Arshavsky VY, Lamb TD, Pugh EN Jr. G proteins and phototransduction. Annu Rev Physiol. 2002; 64: 153–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Orban T, Jastrzebska B, Palczewski K. Structural approaches to understanding retinal proteins needed for vision. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2014; 27: 32–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palczewski K, Orban T. From atomic structures to neuronal functions of G protein-coupled receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2013; 36: 139–164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Palczewski K. G protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2006; 75: 743–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Palczewski K. Chemistry and biology of vision. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287: 1612–1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Palczewski K. Thematic minireview series on focus on vision. J Biol Chem. 2012; 287: 1610–1611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yau KW, Hardie RC. Phototransduction motifs and variations. Cell. 2009; 139: 246–264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Luo DG, Xue T, Yau KW. How vision begins: an odyssey. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008; 105: 9855–9862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palczewski K. Is vertebrate phototransduction solved? New insights into the molecular mechanism of phototransduction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994; 35: 3577–3581 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Arshavsky VY, Wensel TG. Timing is everything: GTPase regulation in phototransduction. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2013; 54: 7725–7733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cideciyan AV, Zhao X, Nielsen L, Khani SC, Jacobson SG, Palczewski K. Null mutation in the rhodopsin kinase gene slows recovery kinetics of rod and cone phototransduction in man. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998; 95: 328–333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chen CK, Burns ME, Spencer M, et al. Abnormal photoresponses and light-induced apoptosis in rods lacking rhodopsin kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999; 96: 3718–3722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen J, Simon MI, Matthes MT, Yasumura D, LaVail MM. Increased susceptibility to light damage in an arrestin knockout mouse model of Oguchi disease (stationary night blindness). Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999; 40: 2978–2982 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Howes KA, Pennesi ME, Sokal I, et al. GCAP1 rescues rod photoreceptor response in GCAP1/GCAP2 knockout mice. EMBO J. 2002; 21: 1545–1554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mendez A, Burns ME, Sokal I, et al. Role of guanylate cyclase-activating proteins (GCAPs) in setting the flash sensitivity of rod photoreceptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001; 98: 9948–9953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kiser PD, Golczak M, Palczewski K. Chemistry of the retinoid (visual) cycle. Chem Rev. 2014; 114: 194–232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nemet I, Tian G, Imanishi Y. Submembrane assembly and renewal of rod photoreceptor cGMP-gated channel: insight into the actin-dependent process of outer segment morphogenesis. J Neurosci. 2014; 34: 8164–8174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Tian G, Ropelewski P, Nemet I, Lee R, Lodowski KH, Imanishi Y. An unconventional secretory pathway mediates the cilia targeting of peripherin/rds. J Neurosci. 2014; 34: 992–1006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sakami S, Kolesnikov AV, Kefalov VJ, Palczewski K. P23H opsin knock-in mice reveal a novel step in retinal rod disc morphogenesis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014; 23: 1723–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sokolov M, Lyubarsky AL, Strissel KJ, et al. Massive light-driven translocation of transducin between the two major compartments of rod cells: a novel mechanism of light adaptation. Neuron. 2002; 34: 95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maeda A, Palczewska G, Golczak M, et al. Two-photon microscopy reveals early rod photoreceptor cell damage in light-exposed mutant mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014; 111: E1428–E1437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carroll J, Kay DB, Scoles D, Dubra A, Lombardo M. Adaptive optics retinal imaging—clinical opportunities and challenges. Curr Eye Res. 2013; 38: 709–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]