Abstract

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX) is an extracellular transmembrane homodimeric zinc metalloenzyme that has been validated as a prognostic marker and therapeutic target for several types of aggressive cancers. CA IX shares a close homology with other CA isoforms, making the design of CA IX isoform selective inhibitors challenging. In this paper, we describe the development of a new class of CA IX inhibitors that comprise a sulfamate as the zinc binding group, a variable linker, and a carbohydrate “tail” moiety. Seven compounds inhibited CA IX with low nM Ki values of 1–2 nM and also exhibited permeability profiles to preferentially target the binding of extracellular CA IX over cytosolic CAs. The crystal structures of two of these compounds in complex with a CA IX-mimic (a variant of CA II, with active site residues that mimic CA IX) and one compound in complex with CA II have been determined to 1.7 Å resolution or better and demonstrate a selective mechanism of binding between the hydrophilic and hydrophobic pockets of CA IX versus CA II. These compounds present promising candidates for anti-CA IX drugs and the treatment for several aggressive cancer types.

Introduction

A characteristic feature of many solid tumors and hypoxia-treated cancer cells in culture is the expression of carbonic anhydrase IX (CA IX),1 an extracellular facing enzyme that catalyzes the interconversion of CO2 and H2O to HCO3– and a H+. CA IX works in concert with cell membrane transporters to regulate the pH of tumor cells, thereby enabling them to manage the acid load due to the metabolic transition known as the Warburg effect.2 The action of CA IX maintains the intracellular pH (pHi) of solid tumors within the tight range needed for cell survival and growth, while at the same time the extracellular pH (pHe) becomes more acidic, promoting tumor growth and metastasis.3 The expression of CA IX in a broad range of solid tumor types is associated with a poor patient prognosis, and more recently the enzyme has been established as a therapeutic target for several aggressive cancers.2a,2c,4 Because the CA IX expression profile in healthy cells is restricted to a few tissues (stomach and GI tract), there is substantial interest in investigating CA IX as a diagnostic and novel drug target for cancer management.2,4,5

A diverse collection of aromatic and heterocyclic compounds with primary sulfonamide or sulfamate zinc binding functional groups (ZBGs) are known with CA inhibition activity. The ZBG of these compounds bind with the CA active site in an invariant manner, however, interactions of the remainder of the compound with the CA active site are variable and this has allowed a range of CA binding configurations and CA isozyme selectivity profiles. Our group recently established synthetic methodology to incorporate either the primary sulfonamide or primary sulfamate ZBGs directly onto monosaccharide scaffolds. When compared to conventional CA inhibitors, these novel glycoconjugates have poor cell membrane passive diffusion characteristics, a property that leads to the selective inhibition of CA IX owing to the extracellular facing active site of this enzyme.6 Glycosidic inhibitors of carbonic anhydrase IX comprising a classical aromatic sulfonamide pharmacophore have been reviewed previously.7 This alternate inhibitor design has delivered improved selectivity for CA IX when compared to optimizing CA IX efficacy alone. In this study, we extend our focus on preparing sulfamate-based glycoconjugate CA inhibitors to modulate selective CA IX inhibition through the combination of structure–activity and structure–property relationships. We then examined the interactions of selected compounds when binding to wild-type CA II and a CA IX-mimic. The use of the CA IX-mimic is a powerful and relatively new structural tool in the field of CA drug discovery. This CA IX-mimic construct was engineered by site-directed mutagenesis of residues in the active site of CA II to residues unique to CA IX, such that the active site of the CA IX-mimic is analogous to wild-type CA IX.6 The advantage of the CA IX-mimic is that it extremely stable and readily crystallizes, allowing, for the first time, direct structural insight into CA II versus CA IX inhibitor binding with a range of novel small molecules.8 The CA II to CA IX-mimic mutations are A65S, N67Q, E69T, I91L, F131V, K170E, and L204A.8a Here we present the first study reporting structural insights of sulfamate small molecules binding to the catalytic site of CA IX via use of the CA IX-mimic.6,7

Results and Discussion

Compound Design and Synthesis

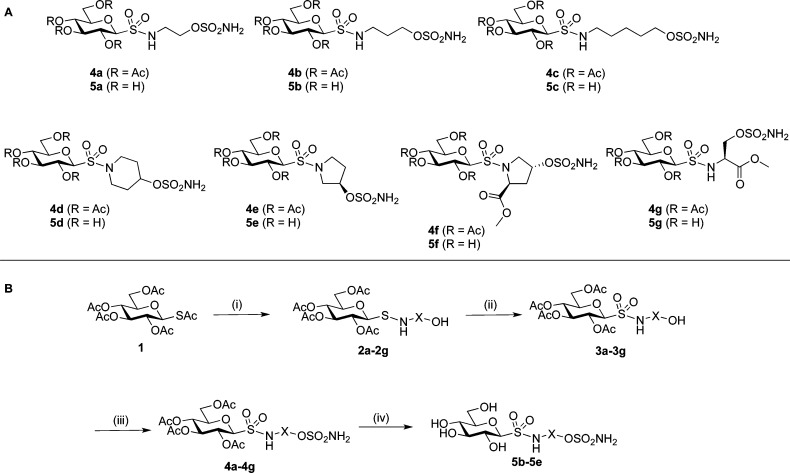

The primary goal of this study was to move away from the classical aromatic sulfonamide CA inhibitor structure toward novel chemical entities with an alternate pharmacophore for CA binding. We designed and synthesized a series of carbohydrate-based sulfamate compounds to build upon our earlier success with this approach to CA IX inhibitor design, Scheme 1.9 Sulfamates have been shown to feature in the structures of compounds with important medicinal applications.10 The glucose moiety is common to all target compounds, and the glucose moiety is bridged via a sulfonamide functionality to a variable linker region (X) that terminates with the primary sulfamate ZBG, Scheme 1.6e,11 These compounds are novel, and sulfamates of this level of diversity have not been investigated for CA inhibition previously. The origin of the linker region diversity is the selected panel of primary (a–c) and secondary (d–g) amino alcohols that were chosen to probe potential CA active site interactions through altering the linker length, steric bulk, and stereochemistry close to the ZBG. In particular, it is hoped that these compounds will form different interactions with CA II and CA IX, exploiting their seven key amino acid active site residue differences, and providing a structure-based starting point to guide future inhibitor design.

Scheme 1. (A) Carbohydrate-Based Sulfamate Target Compounds with a Variable Linker Region 4a–4g and 5a–5g; (B) Synthetic Approach Towards Target Carbohydrate:Sulfamate Compounds Showing Variable Linker Region as ‘X’.

Reagents and conditions. (i) (a) 2.5 equiv BrCH(CO2Et)2, MeOH, rt, 20 min, (b) 3.0 equiv amino alcohol a–g, rt, 1 h; (ii) 6.0 equiv mCPBA, CH2Cl2, rt, 1–5 h; (iii) ClSO2NCO, HCO2H, DMA 0 °C → rt, 3 h; (iv) NaOH, MeOH, 0 °C to rt, 2–4 h; then Amberlite IR120-H+.

The synthetic approach toward the acylated carbohydrate-based sulfamates 4a–4g proceeded in three steps commencing from 2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-S-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranose6e,9a1 and a panel of seven amino alcohols, a–g, Scheme 1. Reaction of 1 with a–g gave the corresponding sulfonamides terminating in a primary or secondary alcohol group, 2a–2g, which were either purified (2f and 2g) or immediately oxidized (2a–2e) to give the sulfonamide-bridged glycoconjugates 3a–3g. Next, sulfamoylation of the terminal alcohol functionality of 3a–3g using sulfamoyl chloride (generated in situ from formic acid and chlorosulfonylisocyanate) gave the target sulfamates 4a–4g in yields of 44–79%. Lastly, the fully deprotected compounds 5a–5g were prepared by deacetylation with standard Zemplén conditions.12 The fully deprotected sulfamates 5b–5e were synthesized in almost quantitative yields from 4b–4e, however, glycoconjugates 5a, 5f, and 5g contained byproducts that could not be separated. Using either milder basic deacetlyation conditions with ammonia13 or acidic deacetylation conditions (AcCl14 or TsOH15 as catalysts) did not give 5a, 5f, and 5g.

CA Inhibition

The aim of this study was to generate glycoconjugate sulfamates for targeting cancer-associated CA IX. Both CA IX and CA XII have an extracellular facing active site with expression upregulated in a wide selection of hypoxic tumors, however, CA XII has more widespread constitutive expression than CA IX, so it is of general interest to evaluate new compounds for inhibition of both CA IX and CA XII enzymatic activity so as to provide a better understanding of the compounds potential as a cancer therapeutic. The CA inhibition data to block the interconversion of CO2 and H2O yielding HCO3– and a H+ for the 11 high purity sulfamates 4a–4g and 5b–5e was measured for CA I, CA II, CA IX, and CA XII, and results are presented in Table 1. The selectivity ratios for CA IX and CA XII inhibition over the intracellular and physiologically dominant CA I and CA II are also presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Inhibition, Permeability, and Isozyme Selectivity Ratio Data for Human CA Isozymes I, II, IX, and XII with Compounds 4a–4g and 5b–5e.

|

Ki (nM)b |

selectivity ratioc |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| compd | cLogPa | CA I | CA II | CA IX | CA XII | I/IX | II/IX | I/XII | II/XII |

| 4a | –0.76 | 1050 | 94 | 215 | 9 | 5 | <1 | 117 | 10 |

| 4b | –0.51 | 1350 | 525 | 215 | 94 | 6 | 2 | 14 | 6 |

| 4c | –0.39 | 350 | 10 | 2 | 9 | 175 | 5 | 39 | 1 |

| 4d | –0.93 | 2400 | 265 | 2 | 60 | 1200 | 133 | 40 | 4 |

| 4e | –0.30 | 1550 | 110 | 2 | 8 | 775 | 55 | 194 | 14 |

| 4f | –0.01 | 9500 | 725 | 2 | 1 | 4750 | 363 | 9500 | 725 |

| 4g | –0.89 | >20000 | 190 | 115 | 85 | >174 | 2 | >235 | 2 |

| 5b | –2.65 | 9000 | 5 | 2 | 1 | 4500 | 3 | 9000 | 5 |

| 5c | –2.53 | 2400 | 6400 | 2 | 21 | 1200 | 3200 | 114 | 305 |

| 5d | –3.07 | >20000 | >20000 | 11 | 85 | >1800 | >1800 | >235 | >235 |

| 5e | –2.44 | 2400 | 185 | 2 | 34 | 1200 | 93 | 71 | 5 |

Calculated using ChemDraw Ultra 12.

Errors in the range of ±5% of the reported value, from three determinations.

Selectivity is determined by the ratio of Kis for CA isozyme relative to CA IX and XII.

All compounds showed weakest inhibition at CA I compared to CA II, CA IX, and CA XII. This weaker CA I inhibition, typically with Kis in the micromolar range, is a common observation for reported primary sulfonamide and sulfamate compounds. As CA I is considered an off-target CA isozyme, this weak CA I inhibition is a desirable attribute for the compounds of this study. For CA II, CA IX, and CA XII, the SAR is more variable and more interesting in terms of the goal to deliver improved inhibitors targeting hypoxic tumors. The inhibition profile for all compounds depended on both the linker as well as the acetylation status of the glucose moiety. The former affects the positioning of the ligand relative to the active site residues, while the later impacts on the steric bulk as well as hydrogen bonding capacity of the “tail” moiety. At CA II the Ki values exhibited a broad range from 5 nM for 5b to >20000 nM for 5d. Compounds with CA IX efficacy and selectivity as well as compounds with good efficacy at both CA II and CA IX would be useful probe compounds for establishing the potential of CA inhibitors in treating hypoxic tumors or impeding metastasis.

Of the compounds with acetylated glucose “tail” moieties, 4c, 4d, 4e, and 4f, were shown to be excellent CA IX inhibitors, with Ki values of ∼2 nM, while the remaining acetylated compounds 4a, 4b, and 4g were ∼50–100-fold poorer CA IX inhibitors (Kis of 215, 215, and 115 nM, respectively). Compounds 4a–4c have the sulfamate ZBG attached to a linear ethyl, propyl, or butyl linker, respectively, while 4d, 4e, and 4f have a six (4d) or five (4e and 4f) membered piperidine or pyrrolidine ring system, respectively, directly attached to the sulfamate moiety. Compound 4g is an analogue of 4b, however, the propyl linker has a substituent that results in a T-shaped ligand close to the ZBG. The SAR at CA IX for the acetylated compounds reveals several trends: First, the steric bulk of the ring system that separates the glucosyl sulfonamide “tail” from the ZBG is preferred over the short linear alkyl chains (ethyl and propyl) as linker, however, for 4c, where the linker is a linear butyl group, this trend is broken and this compound has a comparable Ki to the cyclic systems (Ki = 2 nM). This indicates that both the five-membered or six-membered ring and the butyl chain position the glycosyl sulfonamide moiety to form favorable interactions with CA IX active site residues that is not possible with the shorter linked 4a and 4b or branched compound 4g. The deacetylated compounds 5b–5e are all good inhibitors of CA IX (Kis 2–11 nM). When comparing each acetylated inhibitor with its deacetylated counterpart, the 4b/5b pair of compounds stand out (4bKi = 215 nM, 5bKi = 2 nM), and this ∼100-fold difference in inhibition shows that 4b has potential as a produg for 5b and the removal of the acetyl masking groups from 4b would lead to reinstatement of the CA IX binding 100-fold on formation of 5b. Our group has previously demonstrated the in vitro metabolic stability, plasma stability, and plasma protein binding characteristics important for prodrugs for the acetyl group when presented on a glucose scaffold.16 The inhibition of CA XII, the other tumor-associated CA, revealed two noteworthy compounds with subnanomolar Ki values, compounds 4f (Ki = 1 nM) and 5b (Ki = <1 nM). Compounds with this activity level are relatively uncommon. Both 4f and 5b are also very potent CA IX inhibitors, with with Kis of 2 nM. These compounds may be valuable probes for cells in which CA IX inhibition leads to upregulation of CA XII expression.5a,17 The remaining sulfamates have CA XII Ki values of 8–94 nM. Compound 4b showed good selectivity for CA XII over CA I and CA II, while compound 5b had good selectivity for CA XII over CA I but was equipotent at CA II. In summary, the qualitative SAR analysis of these novel sulfamates has revealed several compounds with valuable inhibition activity and selectivity for CA IX. Lastly, the cLogP values for all compounds are less than zero (Table 1), indicating that these compounds are likely to have limited membrane permeability, also improving the targeting of the extracellular facing CA IX active site over intracellular CAs.

Crystallographic Studies

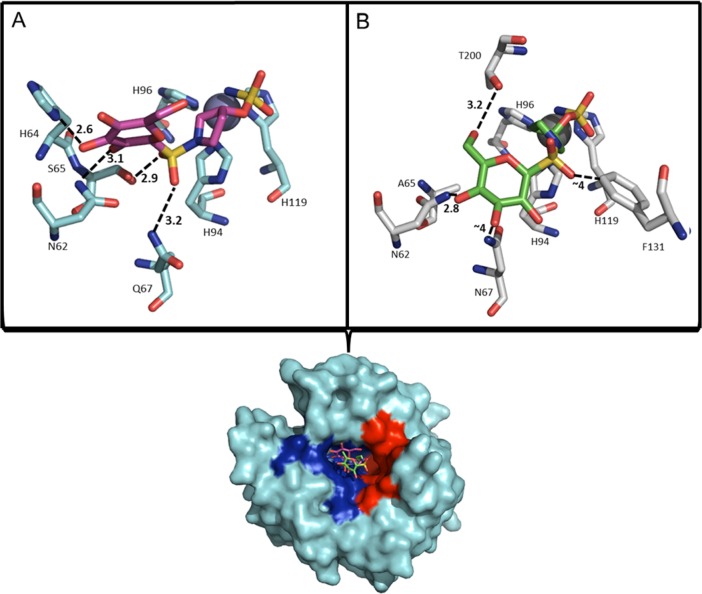

X-ray crystallography was used to analyze the mode of binding of the CA IX selective sulfamoylpyrrolidinyl compound, 5e, in complex with CA II (CA II Ki = 185 nM) and the CA IX-mimic (CA IX Ki = 2 nM) to gain insight in to the ∼90-fold selectivity of 5e for CA IX. The structural analysis of the CA IX-mimic in complex with 5e (Figure 1A) reveals that 5e binds with the primary sulfamate group interacting directly with the catalytic zinc. Furthermore, binding of 5e induces complete displacement of the ordered water network of the CA active site, stabilization of residue H64 (which facilitates proton transfer during catalysis), and ordering of N-terminal residues that are not typically observed in crystal structures of CA II.8,9 The “tail” region of 5e, comprising the sulfonamide-bridged glucose moiety, interacts primarily with the hydrophilic pocket of the enzyme (Figure 1; surface rendition). Specifically, interactions between the nitrogen of the imidazole ring of H64 and the amine of N62 form predicted stabilizing hydrogen bonds with the 3′ or 2′ hydroxyl of the glucose moiety, respectively, and interactions between the carbonyl of Ser65 and the amine of Q67 with one each of the oxygen atoms of the sulfonamide-bridging moiety. The distances between the nitrogen of the imidazole ring of H64 and the 3′ hydroxyl of the glucose moiety (2.6 Å) imply a strong hydrogen bond interaction. Potential van der Waals interactions also contribute to stabilizing the “tail” region of 5e within the hydrophilic pocket of the CA IX-mimic. The side chain of S65 exists as a dual conformer that shows a minor fluctuation in bond distance between the carbonyl of S65 and the 2′ hydroxyl of the sugar moiety. Stabilization of this interaction may induce stronger binding events between ligands and CA IX. The interactions involving S65 and Q67 most likely result in the significant increase in binding events observed in CA IX-mimic over CA II. Furthermore, the replacement of F131 with a valine between CA II and CA IX, respectively, may induce favorable entry of larger ligands such as 5e into the active site of CA IX and thus contribute to an increase in affinity.

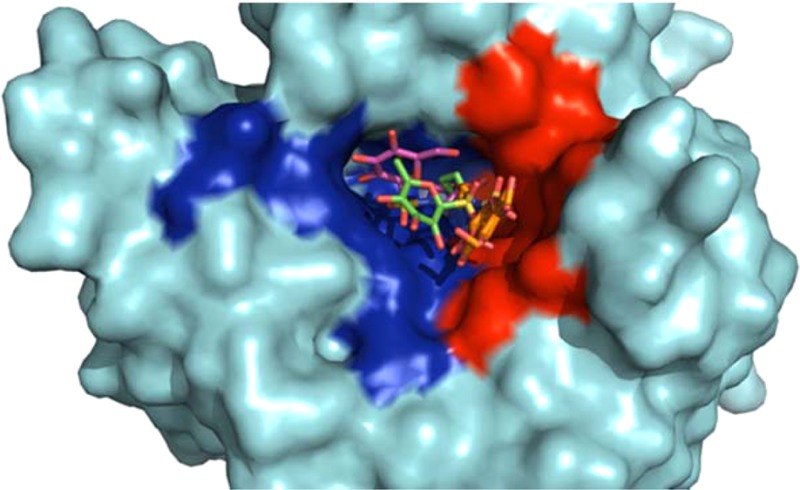

Figure 1.

(A) CA IX-mimic (cyan) and 5e (magenta). (B) CA II (gray) and 5e (green) as they correlate to a surface representation depicting the location of 5e. Highlighted hydrophobic (red) and hydrophilic (blue) residues. Specific interactions and hydrogen-bond distances (Å) are shown. Figure was made using PyMol.16 Residues are as labeled (CA II numbering).

The structural analysis of the CA II_5e complex (Figure 1B) reveals the expected primary sulfamate interaction with the zinc as observed in the structure of the CA IX-mimic_5e complex. The CA II_5e complex also shows complete displacement of the ordered water network of the CA active site, ordering of the N-terminal residues and stabilization of the imidazole group of H64. In addition the “tail” region of 5e interacts primarily with the hydrophilic pocket (Figure 1; surface rendition) of the CA II active site, however with fewer interactions than the CA IX-mimic. Primary interactions occur between the amine of N62, and the carbonyl of T200, forming potential H-bonds (2.8 and 3.2 Å, respectively) with the 4′ and 2′ hydroxyl groups of the glucose moiety of 5e, respectively. A weaker interaction is predicted to occur between the amine of N67 and the 3′ hydroxyl of 5e (bond distance of ∼4 Å). Additional weak hydrophobic interactions are observed between the oxygen of the sulfonamide bridge and the benzyl ring of F131. A structural overlay of the CAII_5e and CA IX-mimic_5e structures (rmsd = 0.11 Å) reveals distinct differences in binding mode of the “tail” of 5e (not shown). The sugar moiety of 5e bound in the CA IX-mimic active site has greater interactions with residues in the hydrophilic cleft, most likely due to the A65S and N67Q residue differences between CA II and the CA IX-mimic. The addition of these interactions most likely contributes to the increased affinity the ligand has for CA IX. Both structures are stabilized by interactions observed between the amine of Q92 and the sulfonamide bridge (not shown).

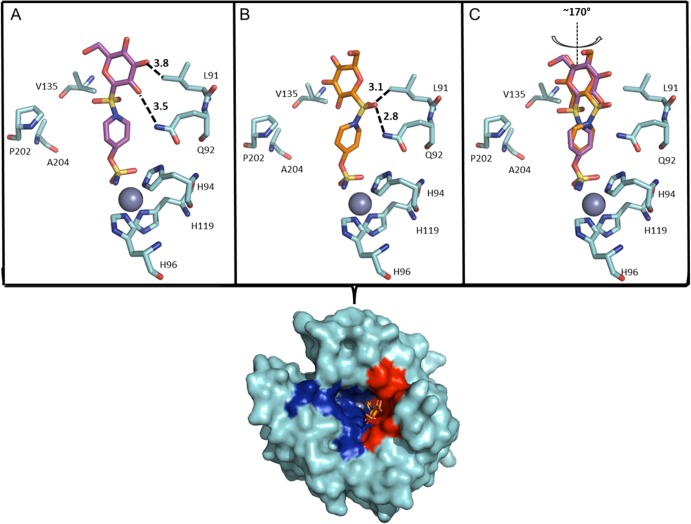

We next turned our attention to investigate the mode of binding of the sulfamoylpiperidinyl compound, 5d, in complex with the CA IX-mimic. Compound 5d has >3 orders of magnitude selectivity for CA IX (Ki = 11 nM) over CA II (Ki = >20000 nM). Similar to the sulfamoylpyrrolidinyl compound 5e, compound 5d binds to the CA IX-mimic active site with the primary sulfamate group interacting directly with the zinc and displacing the zinc bound hydroxyl and ordered water network, however, unlike 5e, there is no observable N-terminal ordering or stabilization of the H64. Interestingly, the electron density maps indicate that 5d binds in two different conformations in the active site of CA IX-mimic (Figure 2C). In both conformations, the orientation of the sulfamate interacting with the zinc is conserved, but there is an observable ∼170° rotation at the S–N bond of the sulfonamide bridging moiety resulting in the −NH–SO2– group of each of the two conformers of 5d pointing in the opposite directions (Figure 2C). This leads to two sets of different interactions observed between the “tail” region of 5d with interfacing residues of the CA IX-mimic. We propose that conformation 1 is stabilized by a weak hydrogen bond (3.5 Å) between the amine of Q92 and the 3′ hydroxyl of the glucose moiety (Figure 2A). Alternatively, conformation 2 appears to be stabilized through an interaction of a bridging sulfonamide oxygen and the same amine of Q92, most likely forming a stronger hydrogen bond (2.8 Å) (Figure 2B). In addition, both conformations appear to be stabilized by weak van der Waals interactions within the hydrophobic cleft of the CA IX-mimic active site (Figure 2; surface rendition), specifically with L91.

Figure 2.

(A) CA IX-mimic (cyan) and 5d. (A) Conformation 1 (purple) and (B) conformation 2 (orange) as they correlate to a surface representation depicting the location of 5d. Highlighted hydrophobic (red) and hydrophilic (blue) residues. Specific interactions and hydrogen bond distances (Å) are shown. (C) An overlay of each conformation of 5d. Note: there is a 170° rotation observed between sulfonamide bridges that distinguishes the two conformers. Figure was made using PyMol.16 Residues are as labeled (CA II numbering).

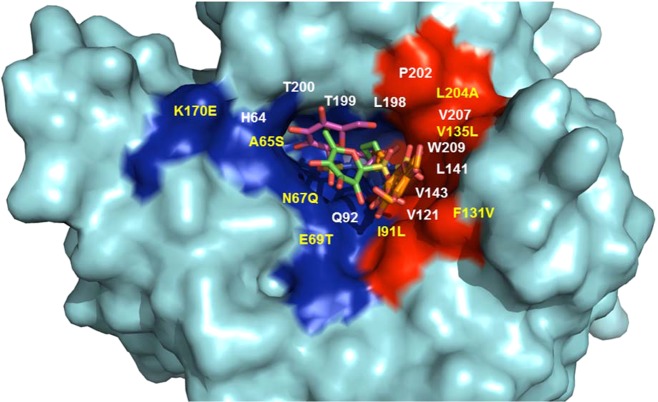

Interestingly, this observation appears in contrast to the binding events of 5e, which interacts more closely with the hydrophilic residues of the active site. This explains the difference between binding observed by our inhibition data. Compound 5e, despite showing a ∼90-fold difference in inhibition between CA IX and CA II, still inhibits CA II with nanomolar affinity. This is due to the conserved regions of the hydrophilic pockets of CA II and CA IX, allowing for relatively high binding to occur between each isoform (Figure 3). Specifically, residues N62 and Q92 are conserved between CA II and CA IX and also interact directly with compound 5e, hence observable nanomolar inhibition between both isoforms. In contrast, however, the hydrophobic pocket of CA IX versus CA II shows higher variability (Figure 3). This is indicative of the binding observed by compound 5d where there is a much larger difference (>1000-fold) between CA II and CA IX. A similar but less pronounced relationship (>100-fold) was observed for 4d, the per-O-acetylated analogue of 5d. Specifically, the substitutions of I91L and F131V contribute highly to the difference in binding. L91 has been classified as a key residue that makes up one of the “selective pockets” observed in the CA active site.18 As shown in the CA IX-mimic, this residue interacts directly with compound 5d, most likely contributing to the increased inhibition. As mentioned previously, the residue at position 131 seems to act as “steric-blocker” such that it impedes bulky compounds entering the CA active site. The absence of a phenylalanine at position 131 in CA IX allows compounds, such as 5d, to readily enter the active site and interact with the hydrophobic pocket. Figure 3 summarizes the overall modes of binding between both compound 5e and 5d and their generic interactions with both the hydrophilic and hydrophobic pockets. In addition, variable residues are highlighted within each pocket. It should be noted that attempts were made to complex 5d with wild-type CA II in order to obtain structural data. However, due to the aforementioned attributes, we were unsuccessful in attempts to bind 5d to CA II for structural comparisons.

Figure 3.

Surface representation depicting the location of 5e (in both CA II and CA IX-mimic) and 5d (in CA IX-mimic, only). Highlighted hydrophobic (red) and hydrophilic (blue) residues. Relative location of interfacing residues are labeled. Residues that differ between CA II and CA IX (and CAIX mimic) (yellow) and that are conserved (white). Figure was made using PyMol.16

Conclusion

In summary, CA IX inhibitors have a role to play in balancing pH to support cancer therapy by limiting the survival and metastasis of hypoxic tumors. Specifically, we present the design, synthesis, biological evaluation, and structural study of carbohydrate-based sulfamates of the motif [sulfamate]-[variable linker]-[sugar] as CA IX inhibitors. Seven of the novel sulfamates of this study were shown to be excellent CA IX inhibitors with Ki values of 1.9–2.4 nM, including the acetylated glucose “tail” moieties 4c, 4d, 4e, and 4f and the deacetylated compounds 5b, 5c, and 5e. Of these, several had 2–3 orders of magnitude selectivity for the inhibition of CA IX over CA I and CA II and so may be useful in vivo in a setting where off-target CAs are abundant. The use of the CA IX-mimic has provided important structural information that may be used to improve the potency and selectivity of these compounds. Our structural analysis indicates that there exist two distinct modes of binding between CA IX and CA II of compound 5e, however, in both cases, this compound interacts with the hydrophilic pocket of the enzyme. As this pocket is generally conserved between CA II and CA IX, it may account for the nanomolar binding affinities between both enzymes. In contrast, compound 5d, which showed a differential inhibition profile between CA II and CA IX, binds to the CA IX active via interactions with the hydrophobic pocket. This region in the CA active site contains more variability between residues of CA II versus CA IX. As a result, this region has been termed as one of the “selective pockets” in the CA active site. Overall, these compounds provide promise in terms of targeting the extracellular active site of CA IX. We anticipate that our findings will bring the field a step closer to valuable compounds capable of rising to the challenge of targeting CA IX therapeutically for the treatment of several cancers.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All starting materials, reagents, and solvents were purchased from commercial suppliers. 1-S-Acetyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranose (1) was prepared as described previously.19 TLC plates were visualized with UV light, ninhydrin stain (1 g of ninhydrin in 100 mL of EtOH containing 3% (v/v) acetic acid), and/or orcinol stain (1 g of orcinol monohydrate in a mixture of EtOH:H2O:H2SO4 72.5:22.5:5 mL). Silica gel flash chromatography was performed using silica gel 60 Å (230–400 mesh). 1H NMR were acquired at 500 MHz and 13C NMR at 125 MHz at 30 °C. 1H and 13C NMR acquired in DMSO-d6 are reported in ppm relative to residual solvent proton (δ 2.50 ppm) and carbon (δ 39.5 ppm) signals, respectively. Assignments for 1H NMR were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY, while assignments for 13C NMR were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. Multiplicity is indicated as follows: s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), m (multiplet), dd (doublet of doublet), ddd (doublet of doublet of doublet), br (broad). Coupling constants are reported in hertz (Hz). Melting points for nonhygroscopic compounds were measured and are uncorrected. High and low resolution electrospray ionization mass spectra were acquired using electrospray as the ionization technique in positive ion and/or negative ion modes as stated. Purity of all compounds was ≥95%.

Synthesis Methods

General Procedure 1: Synthesis of Sulfenamide Linked Glycoconjugates

Diethyl bromomalonate (2.5 equiv) was added to a solution of 1-S-acetyl-2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranose (1) (1 equiv) in anhydrous MeOH. The reaction was stirred at rt under nitrogen for 20 min, then the desired amino alcohol (a–g) (3.0 equiv) added. The reaction was stirred at rt under nitrogen until complete as evidenced by TLC (hexane/EtOAc), typically 1 h. The solvent was removed and the residue dissolved in CH2Cl2 and washed with brine (×3). The combined aqueous fractions were back extracted with CH2Cl2 (×3). The combined organic fractions were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and the solvent removed to give the crude sulfenamides 2a–2g. The amino acid methyl ester derived sulfenamides 2f and 2g were purified with flash chromatography (hexane/EtOAc), while sulfenamides 2a–2e had low stability and were used immediately in the next reaction without further purification or characterization.

General Procedure 2: Oxidation of Sulfenamide Linked Glycoconjugates

To a solution of the sulfenamide derivative (1.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 at 0 °C was added meta-chloroperoxybenzoic acid (6.0 equiv) in CH2Cl2 dropwise over ∼20 min. The reaction was warmed to rt and left until full conversion of the starting material, as evidenced by TLC (hexane/EtOAc), typically 1–5 h. The reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 and quenched with NaHCO3(satd). The organic fraction was separated and washed with NaHCO3(satd) (×1) and brine (×2). The aqueous fractions were back extracted with CH2Cl2 (×2). The combined organic fractions were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated to give the expected sulfonamides. The crude products were purified using flash chromatography (hexane/EtOAc) to give sulfonamides 3a–3g.

General Procedure 3: Conversion of Sulfonamide Linked Glycoconjugates to Sulfamates

The glycoconjugate precursor (1.0 equiv) was dried under vacuum and solubilized in anhydrous N,N-dimethylacetamide (15 equiv) under argon. Sulfamoyl chloride (3.8 equiv) was prepared from formic acid and chlorosufonyl isocyanate as described previously.9a,20 The precursor solution was added slowly to the flask containing sulfamoyl chloride, and the mixture was stirred for 10 min, then warmed to room temperature and stirred for 1 h. The crude reaction mixture was diluted in EtOAc, washed with brine (×3), and the aqueous fractions back extracted with EtOAc (×2). The combined organic fractions were dried over MgSO4, filtered, and concentrated. The crude products were purified using flash chromatography (hexane/EtOAc) to give sulfamates 4a–4g.

General Procedure 4: Deacetylation of Glycoconjugates

The deacylated glycoconjugates were prepared by treating a solution of the per-O-acetylated glucose sulfamate precursor (1.0 equiv) in methanolic sodium methoxide in methanol (25%) at rt. Complete deacetylation was observed after ∼2–4 h (TLC). The reaction mixture was neutralized with Amberlite IR-120 [H+], filtered, and the resin washed with MeOH (×3). The methanol was evaporated under reduced pressure and the residue redissolved in water and lyophilized to afford fully deprotected glycoconjugates 5b–5e. Glycoconjugates 5a, 5f, and 5g could not be purified sufficiently for characterization.

Methyl N-[(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucosyl)thio]-l-4′-hydroxyprolinate (2f)

The title compound was synthesized from l-4-hydroxyproline methyl ester (f) using general procedure 1 and isolated as a white solid (809 mg, 1.59 mmol, 65%). Rf 0.12 (hexane/EtOAc 1/1); mp 80–82 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.28 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.05 (d, J = 4.0 Hz, 1H, OH), 5.02 (d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.88 (t, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.74 (dd, J = 10.4, 9.3 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.22–4.16 (m, 1H, H-4′), 4.14 (dd, J = 12.3, 5.4 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 4.03 (dd, J = 12.5, 2.5 Hz, 1H, H-6b), 3.98–3.91 (m, 2H, H-5, H-2′), 3.62 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.43 (dd, J = 10.0, 5.1 Hz, 1H, H-3′a), 3.06 (dd, J = 9.9, 3.5 Hz, 1H, H-3′b), 2.07–2.01 (m, 4H, H-5′a, 1 × CH3), 1.99 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.98 (s, 3H, CH3), 1.98–1.92 (m, 4H, H-5′b, 1 × CH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 173.2 (CO2CH3), 170.0, 169.5, 169.2, 169.0 (4 × OCOCH3), 86.5 (C-1), 74.4 (C-5), 73.1 (C-3), 68.9 (C-4, C-4′), 68.0 (C-2), 67.9 (C-2′), 66.4 (C-5′), 65.0 (C-3′), 61.9 (C-6), 51.7 (CO2CH3), 20.4, 20.3, 20.28, 20.25 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 508.1 [M + H]+, 530.1 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C20H29NO12SNa [M + Na]+ 530.1303, found 530.1321.

Methyl N-[(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucosyl)thio]-l-serinate (2g)

The title compound was synthesized from l-serine methyl ester (g) according to general procedure 1 and isolated as colorless syrup (322 mg, 670 mmol, 77%). Characterization data for 2g is consistent with literature values.21

N-2′-Hydroxyethyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (3a)

Sulfonamide 3a was prepared from crude N-2′-hydroxyethyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfenamide (2a) according to general procedure 2. The title compound was obtained as a white solid (333 mg, 731 μmol, 30% over two steps). Rf 0.24 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 121–123 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.46 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, NH), 5.38 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.19 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 5.01–4.82 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 4.68 (t, J = 5.5 Hz, 1H, OH), 4.23–4.12 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6a), 4.08–4.00 (m, 1H, H-6b), 3.45–3.41 (m, 2H, CH2OH), 3.08–3.04 (m, 2H, NCH2), 2.02, 2.00, 1.95, 1.95 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.0, 169.5, 169.2, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.9 (C-1), 74.4 (C-5), 72.8 (C-3), 67.64 (C-2), 67.62 (C-4), 61.8 (C-6), 60.5 (CH2OH), 45.5 (NCH2), 20.44, 20.42, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 478.1 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C16H25NO12SNa [M + Na]+ 478.0990, found 478.1005.

N-3′-Hydroxypropyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (3b)

Sulfonamide 3b was prepared from crude N-3′-hydroxypropyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfenamide (2b) according to general procedure 2. The title compound was obtained as a white solid (130 mg, 277 μmol, 39% over two steps). Rf 0.18 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 105–107 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.48 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 5.39 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.18 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.96–4.87 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 4.42 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, OH), 4.21–4.14 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6a), 4.07–4.00 (m, 1H, H-6b), 3.43 (dt, J = 6.9, 5.6 Hz, 2H, CH2OH), 3.08–3.04 (m, 2H, NCH2), 2.02, 1.99, 1.95, 1.94 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), 1.63–1.57 (m, 2H, CH2), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.1, 169.6, 169.3, 168.7 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.5 (C-1), 74.5 (C-5), 72.8 (C-3), 67.65, 67.64 (C-2, C-4), 61.8 (C-6), 58.1 (CH2OH), 40.4 (NHCH2), 33.0 (C-2′), 20.48, 20.46, 20.36, 20.3 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 492.1 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C17H27NO12SNa [M + Na]+ 492.1146, found 492.1154.

N-5′-Hydroxypentyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (3c)

Sulfonamide 3c was prepared from crude N-5′-hydroxypentyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfenamide (2c) according to general procedure 2. The title compound was obtained as a white solid (235 mg, 471 μmol, 19% over two steps). Rf 0.28 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 104–106 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.52 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 5.39 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.18 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.97–4.83 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 4.32 (t, J = 5.1 Hz, 1H, OH), 4.22–4.12 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6a), 4.09–3.98 (m, 1H, H-6b), 3.40–3.37 (m, 2H, CH2OH), 3.06–2.91 (m, 2H, NCH2), 2.01, 1.99, 1.95 1.94 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), 1.46–1.38 (m, 4H, CH2-2′, CH2-4′), 1.35–1.21 (m, 2H, CH2-3′), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.9, 169.5, 169.2, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.6 (C-1), 74.4 (C-5), 72.8 (C-3), 67.6 (C-4 and C-2), 61.8 (C-6), 60.6 (CH2OH), 43.1 (NCH2), 32.0, 29.7 (C-2′, C-4′), 22.6 (C-3′), 20.4, 20.4, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 520.1 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C19H31NO12SNa [M + Na]+ 520.1459, found 520.1480.

N-4′-Hydroxypiperidinyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (3d)

Sulfonamide 3d was prepared from crude N-4′-hydroxypiperidyinyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfenamide (2d) according to general procedure 2. The title compound was obtained as a white solid (182 mg, 367 μmol, 15% over two steps). Rf 0.20 (hexane/EtOAc 1/1); mp 156–158 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.36 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.20 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 5.13 (d, J = 9.8 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.93 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.79 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1H, OH), 4.22–4.15 (m, 1H, H-5), 4.14–4.10 (m, 2H, H-6a/b), 3.69–3.62 (m, 1H, CHOH), 3.55–3.45 (m, 2H, NCH2), 3.17–3.05 (m, 2H, NCH2), 2.05, 2.01, 1.97, 1.96 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), 1.78–1.70 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.47–1.36 (m, 2H, CH2), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.0, 169.5, 169.2, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.6 (C-1), 74.6 (C-5), 72.6 (C-3), 67.6 (C-2), 67.1 (C-4), 64.5 (CHOH), 61.7 (C-6), 43.7, 43.5 (2 × NCH2), 33.9, 33.8 (2 × CH2), 20.5, 20.4, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 518.1 [M + Na+]. HRMS: Calcd for C19H29NO12SNa [M + Na]+ 518.1303, found 518.1298.

N-3′- R-Hydroxypyrrolidinyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (3e)

Sulfonamide 3e was prepared from crude N-3′-R-hydroxypiperidyinyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl) sulfenamide (2e) according to general procedure 2. The title compound was obtained as a white solid (334 mg, 694 μmol, 38% over two steps). Rf 0.58 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 218–220 °C. 1H NMR (400 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.32 (t, J = 9.0 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.27–5.18 (m, 2H, H-1, H-2), 5.07 (d, J = 3.7 Hz, 1H, OH), 4.92 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.35–4.27 (m, 1H, CHOH), 4.17–4.07 (m, 3H, H-5, H-6a/b), 3.53–3.46 (m, 1H, CH2-2′a), 3.46–3.37 (m, 2H, CH2-5′), 3.19 (dd, J = 10.4, 2.7, 1H, CH2-2′b), 2.02, 1.99 (2 × s, 2 × 3H, 2 × CH3), 1.98–1.93 (m, 7H, CH2-4′a, 2 × CH3), 1.80–1.74 (m, 1H, CH2-4′b), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.0, 169.5, 169.2, 168.5 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.1 (C-1), 74.6 (C-5), 72.7 (C-3), 69.3 (C-2), 67.5 (C-4), 67.2 (CHOH), 61.7 (C-6), 55.5 (C-2′), 46.9 (C-5′), 33.8 (C-4′), 20.44, 20.37, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 504.1 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C18H27NO12SNa [M + Na]+ 504.1146, found 504.1163.

Methyl N-[(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucosyl)sulfonyl]-l-4′-hydroxyprolinate (3f)

The title compound was synthesized from 2f according to general procedure 2 and isolated as a white solid (197 mg, 365 μmol, 25%). Rf 0.34 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 165–167 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 5.42–5.26 (m, 3H, H-2, H-3, OH), 5.23 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.95 (t, J = 9.6 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.51 (dd, J = 8.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 4.35–4.31 (m, 1H, CHOH), 4.18 (dd, J = 12.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 4.16–4.03 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6b), 3.66 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.56 (dd, J = 10.1, 3.8 Hz, 1H, CH2-5′a), 3.49 (dd, J = 10.2, 4.9 Hz, 1H, CH2-5′b), 2.19 (ddd, J = 13.2, 8.7, 5.0 Hz, 1H, CH2-3′a), 2.09–2.04 (m, 1H, CH2-3′b), 2.04, 1.99, 1.95, 1.94 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 172.3 (CO2CH3), 170.0, 169.5, 169.1, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 87.0 (C-1), 74.5 (C-5), 72.7 (C-3), 68.3 (C-4), 67.3 (C-2), 67.1 (CHOH), 61.6 (C-6), 59.2 (C-2′), 56.3 (C-5′), 52.1 (CO2CH3), 40.0 (C-3′, under DMSO), 20.4, 20.4, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 562.1 [M + Na+]. HRMS: calcd for C20H29NO14SNa [M + Na]+ 562.1201, found 562.1215.

Methyl N-[(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucosyl)sulfonyl]-l-serinate (3g)

The title compound was synthesized from 2g according to general procedure 2 and isolated as a white solid (148 mg, 288 mmol, 69%). Characterization data for 3g is consistent with literature values.21

N-2′-Sulfamoylethyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (4a)

The title compound was synthesized from 3a according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white solid (96 mg, 179 μmol, 44%). Rf 0.36 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 139–141 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.85 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.51 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.37 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.21 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.97–4.90 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 4.23–4.11 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6a), 4.10–3.98 (m, 3H, H-6b, CH2OSO2NH2), ∼ 3.33 (m, 2H, NCH2 under water signal), 2.02, 1.99, 1.96, 1.95 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.0, 169.5, 169.2, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 86.2 (C-1), 74.6 (C-5), 72.8 (C-3), 67.9 (C-2), 67.5 (C-4), 67.6 (CH2OSO2NH2), 61.7 (C-6), 42.2 (NCH2), 20.5, 20.4, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C HSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 557 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C16H26N2O14S2Na [M + Na]+ 557.0718, found 557.0743.

N-3′-Sulfamoylpropyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (4b)

The title compound was synthesized from 3b according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white solid (94 mg, 172 μmol, 68%). Rf 0.38 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 140–142 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.68 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.43 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.39 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.20 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, H-2), 5.04–4.87 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 4.26–4.14 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6a), 4.11–4.01 (m, 3H, H-6b, CH2OSO2NH2), 3.12–3.09 (m, 2H, NCH2), 2.03, 2.00, 1.97, 1.95 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), 1.87–1.81 (m, 2H, CH2), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.1, 169.6, 169.3, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.6 (C-1), 74.5 (C-5), 72.8 (C-3), 67.58, 67.56 (C-2, C-4), 66.6 (CH2OSO2NH2), 61.8 (C-6), 40.0 (NCH2, under DMSO), 29.5 (C-2′), 20.5, 20.4, 20.34, 20.26 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 571 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C17H28N2O14S2Na [M + Na]+ 571.0874, found 571.0891.

N-5′-Sulfamoylpentyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (4c)

The title compound was synthesized from 3c according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white solid (171 mg, 296 μmol, 73%). Rf 0.24 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 114–116 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.57 (t, J = 5.7 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.38 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.39 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.19 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 4.95–4.89 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 4.25–4.14 (m, 2H, H-5, H-6a), 4.09–3.97 (m, 3H, H-6b, CH2OSO2NH2), 3.02–2.98 (m, 2H, NCH2), 2.02, 2.00, 1.96, 1.95 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), 1.69–1.59 (m, 2H, CH2-4′), 1.51–1.46 (m, 2H, CH2-2′), 1.42–1.30 (m, 2H, CH2-3′), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.9, 169.5, 169.2, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.6 (C-1), 74.4 (C-5), 72.8 (C-3), 68.9 (C-4), 67.6 (C-2), 61.7 (CH2OSO2NH2), 59.7 (C-6), 42.8 (NCH2), 29.3 (C-2′), 27.9 (C-4′), 22.2 (C-3′), 20.5, 20.4, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 599 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C19H32N2O14S2Na [M + Na]+ 599.1187, found 599.1200.

N-4′-Sulfamoylpiperidinyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (4d)

The title compound was synthesized from 3d according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white solid (84 mg, 146 μmol, 52%). Rf 0.34 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 180–182 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.49 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.36 (t, J = 9.2 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.22 (t, J = 9.3 Hz, 1H, H-2), 5.17 (d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.95 (t, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.61 (dt, J = 7.7, 3.7 Hz, 1H, CHOSO2NH2), 4.24–4.17 (m, 1H, H-5), 4.13 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 2H, H-6a/b), 3.51–3.40 (m, 2H, NCH2), ∼ 3.30 (m, 2H, NCH2, under H2O), 2.05, 2.01 (2 × s, 2 × 3H, 2 × CH3), 1.99–1.93 (m, 8H, 2 × CH3, CH2), 1.77 (ddt, J = 12.7, 8.1, 3.7 Hz, 2H, CH2), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.0, 169.5, 169.2, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.6 (C-1), 74.72 (CHOSO2NH2), 74.69 (C-5), 72.6 (C-3), 67.5 (C-4), 67.0 (C-2), 61.7 (C-6), 43.01, 42.98 (2 × NCH2) 31.0 (2 × CH2), 20.5, 20.34, 20.32, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 597.0 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C19H30N2O14S2Na [M + Na]+ 597.1031, found 597.1038.

N-3′-R-Sulfamoylpyrrolidinyl-S-(2,3,4,6-tetra-O-acetyl-1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (4e)

The title compound was synthesized from 3e according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white solid (177 mg, 317 μmol, 61%). Rf 0.43 (hexane/EtOAc 1/3); mp 140–142 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.62 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.36–5.30 (m, 1H, H-3), 5.29–5.21 (m, 2H, H-1, H-2), 5.07 (dt, J = 5.2, 2.7 Hz, 1H, CHOSO2NH2), 5.00–4.93 (m, 1H, H-4), 4.14 (d, J = 3.9 Hz, 3H, H-5, H-6a/b), 3.67 (dd, J = 11.4, 4.6 Hz, 1H, CH2-2′a), 3.61 (dt, J = 9.0, 3.1 Hz, 1H, CH2-4′a), 3.55 (dd, J = 11.4, 1.1 Hz, 1H, CH2-2′b), 3.38 (td, J = 9.7, 6.9 Hz, 1H, CH2-4′b), 2.28–2.12 (m, 2H, CH2-5′), 2.03, 2.00, 1.97, 1.95 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 169.9, 169.5, 169.1, 168.5 (4 × OCOCH3), 85.3 (C-1), 78.7 (C-5), 74.7 (CHOSO2NH2), 72.6 (C-3), 67.3 (C-2), 67.1 (C-4), 61.5 (C-6), 53.3 (C-2′), 46.6 (C-5′), 31.5 (C-4′), 20.4, 20.34, 20.29, 20.2 (4 × CH3) (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 583 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C18H28N2O14S2Na [M + Na]+ 583.0874, found 583.0897.

Methyl N-[(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucosyl)sulfonyl]-l-4′-sulfamoylprolinate (4f)

The title compound was synthesized from 3f according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white solid (210 mg, 339 μmol, 61%). Rf 0.31 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 166–168 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.68 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.36–5.22 (m, 3H, H-1, H-2, H-3), 5.07–5.03 (m, 1H, CHOSO2NH2), 4.99 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-4), 4.54 (dd, J = 8.6, 5.2 Hz, 1H, H-2′), 4.20–4.09 (m, 3H, H-5, H-6a/b), 3.79 (d, J = 4.8 Hz, 2H, CH2-5′), 3.69 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.60 (ddd, J = 13.9, 8.7, 5.6 Hz, 1H, CH2-3′a), 2.38–2.33 (m, 1H, CH2-3′b), 2.03, 1.99, 1.95 (3 × s, 2 × 3H, 1× 6H, 4 × CH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 171.5 (CO2CH3), 170.0, 169.5, 169.1, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 86.5 (C-1), 76.4 (CHOSO2NH2), 74.7 (C-5), 72.6 (C-3), 67.2 (C-4), 66.9 (C-2), 61.4 (C-6), 58.5 (C-2′), 53.8 (C-5′), 52.4 (OCH3), 35.9 (C-3′), 20.4, 20.32, 20.28, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 641.0 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C20H30N2O16S2Na [M + Na]+ 641.0929, found 641.0957.

Methyl N-[(2,3,4,6-Tetra-O-acetyl-β-d-glucosyl)sulfonyl]-l-sulfamoylserinate (4g)

The title compound was synthesized from 3g according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white solid (110 mg, 186 μmol, 79%). Rf 0.35 (hexane/EtOAc 1/2); mp 116–118 °C. 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 8.59 (d, J = 8.6 Hz, 1H, NH), 7.62 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.38 (t, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-3), 5.20 (t, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-2), 5.02–4.85 (m, 2H, H-1, H-4), 4.38–4.34 (m, 1H, CH), 4.24–4.16 (m, 3H, H-6a, CH2OSO2NH2), 4.11 (ddd, J = 10.0, 4.4, 2.2 Hz, 1H, H-5), 3.98 (dd, J = 12.6, 2.3 Hz, 1H, H-6b), 3.72 (s, 3H, OCH3), 2.02, 1.99, 1.96, 1.95 (4 × s, 4 × 3H, 4 × CH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 170.0 (CO2CH3), 169.5, 169.1, 168.8, 168.6 (4 × OCOCH3), 86.5 (C-1), 74.5 (C-5), 72.7 (C-3), 68.6 (CH2OSO2NH2), 67.33 (C-4), 67.25 (C-2), 61.3 (C-6), 55.5 (CH), 52.6 (OCH3), 20.42, 20.38, 20.3, 20.2 (4 × OCOCH3), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 615 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C18H28N2O16S2Na [M + Na]+ 615.0772, found 615.0789.

N-3′-Sulfamoylpropyl-S-(1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (5b)

The title compound was synthesized from 4b according to general procedure 4 and isolated as a white highly hygroscopic solid (47 mg, 123 μmol, 96%). Rf 0.47 (MeCN/H2O 9/1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.41 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 7.01 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, NH), 5.15–5.09 (m, 2H, OH-2, OH-3), 5.04 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, OH-4), 4.48 (t, J = 6.1 Hz, 1H, OH-6), 4.21 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.07 (t, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H, CH2OSO2NH2), 3.69 (ddd, J = 12.3, 6.9, 2.4 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 3.48–3.40 (m, 1H, H-2), 3.30–3.22 (m, 3H, H-3, H-5, H-6b), 3.13–3.02 (m, 3H, H-4, NCH2), 1.89–1.77 (m, 2H, CH2), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 89.0 (C-1), 81.1 (C-5), 77.5 (C-2), 70.5 (CH2OSO2NH2), 69.7 (C-3), 66.7 (C-4), 61.1 (C-6), 40.0 (NCH2, under DMSO), 29.4 (C-2′), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 403 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C9H20N2O10S2Na [M + Na]+ 403.0452, found 403.0450.

N-5′-Sulfamoylpentyl-S-(1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (5c)

The title compound was synthesized from 4c according to general procedure 4 and isolated as a white highly hygroscopic solid (51 mg, 125 μmol, 96%). Rf 0.53 (MeCN/H2O 9/1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.38 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 6.89 (t, J = 5.9 Hz, 1H, NH), 5.12–5.08 (m, 2H, OH-2, OH-3), 5.04 (d, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, OH-4), 4.45 (t, J = 6.7 Hz, 1H, OH-6), 4.18 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 4.01 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 2H, CH2OSO2NH2), 3.68 (ddd, J = 12.2, 6.6, 2.0 Hz, 1H, H-6a), 3.52–3.39 (m, 2H, H-2, H-6b), 3.28–3.21 (m, 2H, H-3, H-5), 3.05 (td, J = 9.2, 5.2 Hz, 1H, H-4), 3.01–2.96 (m, 2H, NCH2), 1.66–1.60 (m, 2H, CH2-4′), 1.51–1.42 (m, 2H, CH2-2′), 1.39–1.33 (m, 2H, CH2-3′), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 89.0 (C-1), 81.0 (C-5), 77.4 (C-2), 70.5 (CH2OSO2NH2), 69.7 (C-3), 68.9 (C-4), 61.1 (C-6), 42.6 (NCH2), 29.2, 27.9 (C-2′, C-4′), 22.2 (C-3′), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 431 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C11H24N2O10S2Na [M + Na]+ 431.0765, found 431.0766.

N-4′-Sulfamoylpiperidinyl-S-(1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (5d)

The title compound was synthesized from 4d according to general procedure 3 and isolated as a white highly hygroscopic solid (39 mg, 97 μmol, 95%). Rf 0.50 (MeCN/H2O 9/1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.47 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.28–5.21 (m, 1H, OH-2), 5.13 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H, OH-3), 5.05 (d, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H, OH-4), 4.58–4.53 (m, OH-6, CHOSO2NH2), 4.39 (d, J = 9.4 Hz, 1H, H-1), 3.78–3.67 (m, 1H, H-6a), 3.60–3.40 (m, 5H, H-2, H-3, H-6b, NCH2), 3.26–3.16 (m, 3H, H-5, NCH2), 3.09 (td, J = 9.6, 5.6 Hz, 1H, H-4), 2.02–1.99 (m, 2H, CH2), 1.74–1.68 (m, 2H, CH2), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 90.2 (C-1), 81.3 (C-5), 77.6, 75.5 (C-2, C-3), 70.3 (CHOSO2NH2), 69.3 (C-4), 60.8 (C-6), 43.4, 42.6 (2 × NCH2), 31.2, 31.1 (2 × CH2), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 429 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C11H22N2O10S2Na [M + Na]+ 429.0608, found 429.0613.

N-3′-R-Sulfamoylpyrrolidinyl-S-(1-thio-β-d-glucopyranosyl)sulfonamide (5e)

The title compound was synthesized from 4e according to general procedure 4 and isolated as a white highly hygroscopic solid (68 mg, 173 μmol, 97%). Rf 0.56 (MeCN/H2O 9/1). 1H NMR (500 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 7.58 (s, 2H, OSO2NH2), 5.26 (d, J = 6.1, 1H, OH-2), 5.12 (d, J = 5.4, 1H, OH-3), 5.08–5.00 (m, 2H, OH-4, CHOSO2NH2), 4.56 (t, J = 5.3 Hz, 1H, OH-6), 4.53 (d, J = 9.5 Hz, 1H, H-1), 3.76–3.68 (m, 2H, H-6a/b), 3.69–3.63 (m, 1H, H-3), 3.51–3.46 (m, 2H, H-2, H-5), 3.44–3.40 (m, 1H, H-4), 3.34–3.27 (m, 2H, CH2-5′), 3.25–3.21 (m, 1H, CH2-2′a), 3.09–3. 05 (m, 1H, CH2-2′b), 2.36–2.34 (m, 1H, CH2-4′a), 2.09–2.01 (m, 1H, CH2-4′b), assignments were confirmed by 1H–1H gCOSY. 13C NMR (125 MHz, DMSO-d6) δ 89.3 (C-1), 81.3 (C-5), 79.1 (C-2), 77.6 (CHOSO2NH2), 70.3 (C-3), 69.4 (C-4), 60.9 (C-6), 52.7 (C-2′), 46.7 (C-5′), 31.4 (C-4′), assignments were confirmed by 1H–13C gHSQC. LRMS (ESI+): m/z 415 [M + Na]+. HRMS: calcd for C10H20N2O10S2Na [M + Na]+ 415.0452, found 415.0449.

Protein Expression, Purification, and CA IX-Mimic Design

Wild-type CA II and CA IX-mimic were expressed and purified using BL21DE3 competent cells as described by Pinard et al.7 The CA IX-mimic used for this study was designed and engineered previous by Genis et al.6 (containing two active site mutations) and reconstructed by Pinard et al.7 (to contain seven active site mutations). The mimic utilized the well-studied and crystallizable CA II, with seven point mutations in the active site that creates a chimeric CA IX active site that can be used for structural analysis. Active site mutations in the CA IX-mimic include: A65S, N67Q, E69T, I91L, F131V, K170E, and L204A. Purity of each enzyme was checked by SDS-PAGE. Concentrations were determined by UV/vis spectroscopy and measured at 43 and 55 mg/mL for CA IX-mimic and CA II, respectively.

X-ray Crystallography

Purified CA II and CA IX-mimic were crystallized in 1.6 M Na-citrate, 50 mM Tris, pH 7.8, using hanging drop vapor diffusion.8a,22 Wells formed crystals for both enzymes were observed after 5 days. Stock solutions of each compound were made using deionized water and to a final concentration of ∼50 mM for each ligand. Crystals were than soaked with desired compound solution 24 h prior to data collection. Diffraction data was collected “in-house” using an RU-H3R rotating Cu anode (λ = 1.5418 Å) operating at 50 kV and 22 mA utilizing an R-Axis IV+2 image plate detector (Rigaku, USA). Each data set was processed using HKL2000.23 All data sets were scaled to a P21 space group with statistics summarized in Table 2. Initial phases for each data set were determined using molecular replacement methods using PDB 3KS3(24) as a search model. Molecular replacement, model refinements, and generation of ligand restraint files were performed using Phenix25 suite of programs. Models for ligand–protein complexes and PDB files for ligands were generated using Coot.26 Coot26b was also used to determine bond lengths and angles used for analysis. Figures for publication were generated using PyMol.27

Table 2. X-ray Crystallography Statistics for Data Processing and Refinement of Ligand Bound CAIX-Mimic and CA II Crystal Structures.

| sample | CAIX-mimic_5e | CAIX-mimic_5d | CAII_5e |

|---|---|---|---|

| PDB accession no. | 4R5A | 4R59 | 4R5B |

| space group | P21 | ||

| cell dimensions (Å; deg) | a = 42 ± 0.4, b = 42 ± 0.4, c = 72 ± 0.3; β = 104 ± 0.4 | ||

| resolution (Å) | 20.0–1.64 | 19.9–1.74 | 19.86–1.50 |

| total reflections | 29753 | 35999 | 37836 |

| Rsyma (%) | 6.2 (31.0) | 7.0 (60.0) | 6.0 (41.5) |

| I/Iσ | 15.35 (3.7) | 18.74 (1.39) | 12.78 (2.87) |

| completeness (%) | 93.2 (87.9) | 92.0 (92.3) | 93.2 (96.5) |

| Rcrystb (%) | 15.5 (19.9) | 15.7 (28.2) | 15.7 (27.0) |

| Rfreec (%) | 18.5 (24.5) | 20.5 (34.4) | 18.5 (26.9) |

| no. of protein atoms | 2124 | 2111 | 2106 |

| no. of water molecules | 242 | 211 | 233 |

| no. of ligand molecules | 24 | 50e | 24 |

| Ramachandran stats (%): favored, allowed, outliers | 95.8, 3.44, 0.76 | 96.5, 3.5, 0.0 | 96.5, 2.69, 0.77 |

| av B factors (Å2): main-chain, side-chain, solvent, ligandd | 16.7, 21.3, 22.4, 29.8 | 16.5, 20.9, 36.4,28.0 | 21.1, 25.4, 32.6, 32.5 |

Rsym = (∑|I – ⟨I⟩|/∑ ⟨I⟩) × 100.

Rcryst = (∑|Fo – Fc|/∑ |Fo|) × 100

Rfree is calculated in the same way as Rcryst, except it is for data omitted from refinement (5% of reflections for all data sets).

Values in parentheses correspond to the highest resolution shell.

Total ligand atoms for both conformations of 5d, hence one conformation contains 25 atoms.

CA Inhibition Assay

An Applied Photophysics stopped-flow instrument was used for assaying the CA-catalyzed CO2 hydration activity.28 IC50 values were obtained from dose response curves working at seven different concentrations of test compound by fitting the curves using PRISM (www.graphpad.com) and nonlinear least-squares methods; values represent the mean of at least three different determinations as described by us previously.29 The inhibition constants (Ki) were then derived by using the Cheng–Prusoff equation as follows: Ki = IC50/(1 + [S]/Km), where [S] represents the CO2 concentration at which the measurement was carried out and Km the concentration of substrate at which the enzyme activity is at half maximal. All enzymes used were recombinant, produced in Escherichia coli as reported earlier.30 The concentrations of enzymes used in the assay were: hCA I, 10.4 nM; hCA II, 8.3 nM; hCA IX, 8.0 nM; hCA XII, 12.4 nM.

Acknowledgments

This research was financed by the Australian Research Council (grant nos. DP110100071, FT10100185 to S.-A.P.), two EU grants of the seventh framework program (Metoxia and Dynano projects to C.T.S.), and R.M. was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health grant CA165284.

Glossary

Abbreviations Used

- CA

carbonic anhydrase

- Ki

inhibition constant

- ZBG

zinc binding group

Supporting Information Available

1H and 13C NMR spectra of compounds 2f, 2g, 3a–3g, 4a–4g, and 5b–5e. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Accession Codes

Coordinates and structure factors for CA IX-mimic_5d, CA IX-mimic_5e, and CA II_5e have been deposited with the PDB, with accession code 4R59, 4R5A, and 4R5B, respectively.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Wykoff C. C.; Beasley N. J.; Watson P. H.; Turner K. J.; Pastorek J.; Sibtain A.; Wilson G. D.; Turley H.; Talks K. L.; Maxwell P. H.; Pugh C. W.; Ratcliffe P. J.; Harris A. L. Hypoxia-inducible expression of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrases. Cancer Res. 2000, 60, 7075–7083. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Svastova E.; Hulikova A.; Rafajova M.; Zatovicova M.; Gibadulinova A.; Casini A.; Cecchi A.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T.; Pastorek J.; Pastoreková S. Hypoxia activates the capacity of tumor-associated carbonic anhydrase IX to acidify extracellular pH. FEBS Lett. 2004, 577, 439–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li Y.; Wang H.; Tu C.; Shiverick K. T.; Silverman D. N.; Frost S. C. Role of hypoxia and EGF on expression, activity, localization and phosphorylation of carbonic anhydrase IX in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2011, 1813, 159–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mahon B. P.; McKenna R. Regulation and role of carbonic anhydrase IX and use as a biomarker and therapeutic target in cancer. Res. Trends Curr. Top. Biochem. Res. 2013, 15, 1. [Google Scholar]; b Neri D.; Supuran C. T. Interfering with pH regulation in tumours as a therapeutic strategy. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery 2011, 10, 767–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrases: novel therapeutic applications for inhibitors and activators. Nature Rev. Drug Discovery 2008, 7, 168–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Höckel M.; Vaupel P. Tumor hypoxia: Definitions and current clinical, biologic, and molecular aspects. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2001, 93, 266–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Moulder J. E.; Rockwell S. Tumor hypoxia: its impact on cancer therapy. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 1987, 5, 313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald P. C.; Winum J.-Y.; Supuran C. T.; Dedhar S. Recent developments in targeting carbonic anhydrase IX for cancer therapeutics. Oncotarget 2012, 3, 84–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Morris J. C.; Chiche J.; Grellier C.; Lopez M.; Bornaghi L. F.; Maresca A.; Supuran C. T.; Pouyssegur J.; Poulsen S.-A. Targeting hypoxic tumor cell viability with carbohydrate-based carbonic anhydrase IX and XII inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 6905–6918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Krall N.; Pretto F.; Decurtins W.; Bernardes G. J. L.; Supuran C. T.; Neri D. A small-molecule drug conjugate for the treatment of carbonic anhydrase IX expressing tumors. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2014, 53, 4231–4235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wilkinson B. L.; Bornaghi L. F.; Houston T. A.; Innocenti A.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. A novel class of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: glycoconjugate benzene sulfonamides prepared by “click-tailing”. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 6539–6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wilkinson B. L.; Bornaghi L. F.; Houston T. A.; Innocenti A.; Vullo D.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: inhibition of isozymes I, II, and IX with triazole-linked O-glycosides of benzene sulfonamides. J. Med. Chem. 2007, 50, 1651–1657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wilkinson B. L.; Bornaghi L. F.; Houston T. A.; Innocenti A.; Vullo D.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. Inhibition of membrane-associated carbonic anhydrase isozymes IX, XII and XIV with a library of glycoconjugate benzenesulfonamides. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2007, 17, 987–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Wilkinson B. L.; Innocenti A.; Vullo D.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrases with glycosyltriazole benzene sulfonamides. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 1945–1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lopez M.; Bornaghi L. F.; Innocenti A.; Vullo D.; Charman S. A.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. Sulfonamide linked neoglycoconjugates—a new class of inhibitors for cancer-associated carbonic anhydrases. J. Med. Chem. 2010, 53, 2913–2926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Singer M.; Lopez M.; Bornaghi L. F.; Innocenti A.; Vullo D.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. Inhibition of carbonic anhydrase isozymes with benzene sulfonamides incorporating thio, sulfinyl and sulfonyl glycoside moieties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19, 2273–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Winum J.-Y.; Poulsen S.-A.; Supuran C. T. Therapeutic applications of glycosidic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Med. Res. Rev. 2009, 29, 419–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Winum J.-Y.; Colinas P.; Supuran C. T. Glycosidic carbonic anhydrase IX inhibitors: a sweet approach against cancer. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1419–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Pinard M. A.; Boone C. D.; Rife B. D.; Supuran C. T.; McKenna R. Structural study of interaction between brinzolamide and dorzolamide inhibition of human carbonic anhydrases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 7210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Alterio V.; Di Fiore A.; D’Ambrosio K.; Supuran C. T.; De Simone G. Multiple binding modes of inhibitors to carbonic anhydrases: how to design specific drugs targeting 15 different isoforms?. Chem. Rev. 2012, 112, 4421–4468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Supuran C. T. Structure-based drug discovery of carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 2012, 27, 759–772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Supuran C. T.; McKenna R.. Carbonic Anhydrase: Mechanism, Regulation, Links to Disease, And Industrial Applications; McKenna R.; Frost S., Eds.; Springer Verlag: Heidelberg, 2014; Vol. 75, pp 291–323. [Google Scholar]

- a Lopez M.; Trajkovic J.; Bornaghi L.; Innocenti A.; Vullo D.; Supuran C.; Poulsen S. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel carbohydrate-based sulfamates as carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2011, 54, 1481–1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Lopez M.; Vu H.; Wang C. K.; Wolf M. G.; Groenhof G.; Innocenti A.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. Promiscuity of carbonic anhydrase II. Unexpected ester hydrolysis of carbohydrate-based sulfamate inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 18452–18462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillane W.; Malaubier Sulfamic acid and its N- and O- substituted derivatives. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114, 2507–2598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez M.; Bornaghi L. F.; Driguez H.; Poulsen S.-A. Synthesis of sulfonamide-bridged glycomimetics. J. Org. Chem. 2011, 76, 2965–2975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zemplén G. Degradation of the reducing bioses. I. Direct determination of the constitution of cellobiose. Ber. Dtsch. Chem. Ges. 1926, 59, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa T.; Numata M.; Asai M.; M T.; Shinkai S. Colorimetric calcium-response of b-lactosylated m-oxo-bis-[5,15-meso-diphenylporphyrinatoiron(III)]. Tetrahedron 2005, 7783–7788. [Google Scholar]

- Yeom C.-E.; Lee S. Y.; Kim Y. J.; Kim B. M. Mild and chemoselcective deacetylation method using a catalytic amount of acetyl chloride in methanol. Synlett 2005, 10, 1527–1530. [Google Scholar]

- González A. G.; Brouard I.; León F.; Padrón J. I.; Bermejo J. A facile chemoselective deacetylation in presence of benzoyl and p-bromobenzoyl groups using p-toluenesulfonic acid. Tetrahedron Lett. 2001, 42, 3187–3188. [Google Scholar]

- a Carroux C. J.; Moeker J.; Motte J.; Lopez M.; Bornaghi L. F.; Katneni K.; Ryan E.; Morizzi J.; Shackleford D. M.; Charman S. A.; Poulsen S.-A. Synthesis of acylated glycoconjugates as templates to investigate in vitro biopharmaceutical properties. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2013, 23, 455–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Carroux C. J.; Rankin G. M.; Moeker J.; Bornaghi L. F.; Katneni K.; Morizzi J.; Charman S. A.; Vullo D.; Supuran C. T.; Poulsen S.-A. A prodrug approach toward cancer-related carbonic anhydrase inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 9623–9634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiche J.; Ilc K.; Laferriere J.; Trottier E.; Dayan F.; Mazure N. M.; Brahimi-Horn M. C.; Pouyssegur J. Hypoxia-inducible carbonic anhydrase IX and XII promote tumor cell growth by counteracting acidosis through the regulation of the intracellular pH. Cancer Res. 2009, 69, 358–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal M.; Kondeti B.; McKenna R. Insights towards sulfonamide drug specificity in alpha carbonic anhydrases. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013, 21, 1526–1533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibatullin F. M.; Shabalin K. A.; Jänis J. V.; Shavvac A. G. Reaction of 1,2-trans-glycosyl acetates with thiourea: a new entry to 1-thiosugars. Tetrahedron Lett. 2003, 44, 7961–7964. [Google Scholar]

- a Okada M.; Iwashita S.; Koizumi N. Efficient general method for sulfamoylation of a hydroxyl group. Tetrahedron Lett. 2000, 41, 7047–7051. [Google Scholar]; b Neres J.; Labello N. P.; Somu R. V.; Boshoff H. I.; Wilson D. J.; Vannada J.; Chen L.; Barry C. E.; Bennett E. M.; Aldrich C. C. Inhibition of siderophore biosynthesis in Mycobacterium tuberculosis with nucleoside bisubstrate analogues: structure–activity relationships of the nucleobase domain of 5′-O-[N-(salicyl)sulfamoyl]adenosine. J. Med. Chem. 2008, 51, 5349–5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez M. L.; Bornaghi L. F.; Poulsen S.-A. Synthesis of sulfonamide-conjugated glycosyl-amino acid building blocks. Carbohydr. Res. 2014, 386, 78–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genis C.; Sippel K. H.; Case N.; Cao W.; Avvaru B. S.; Tartaglia L. J.; Govindasamy L.; Tu C.; Agbandje-McKenna M.; Silverman D. N.; Rosser C. J.; McKenna R. Design of a carbonic anhydrase IX active-site mimic to screen inhibitors for possible anticancer properties. Biochemistry 2009, 48, 1322–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otwinowski Z.; Minor W.. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode; Elsevier: New York, 1997; Vol. 276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avvaru B. S.; Kim C. U.; Sippel K. H.; Gruner S. M.; Agbandje-McKenna M.; Silverman D. N.; McKenna R. A short, strong hydrogen bond in the active site of human carbonic anhydrase II. Biochemistry 2010, 49, 249–251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovanov A. P.; Hautbergue G. M.; Wilson S. A.; Lian L.-Y. A simple method for improving protein solubility and long-term stability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 8933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Debreczeni J. É.; Emsley P. Handling ligands with Coot. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2012, 68, 425–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Emsley P.; Cowton K. Coot: Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. D: Biol. Crystallogr. 2004, 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, version 1.5.0.4; Schrödinger, LLC.

- Khalifah R. G. The carbon dioxide hydration activity of carbonic anhydrase. J. Biol. Chem. 1971, 246, 2561–2573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez M.; Drillaud N.; Bornaghi L. F.; Poulsen S.-A. Synthesis of S-glycosyl primary sulfonamides. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 2811–2816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Winum J.-Y.; Vullo D.; Casini A.; Montero J.-L.; Scozzafava A.; Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors: inhibition of cytosolic isozymes I and II and the membrane-bound, tumor associated isozyme IX with sulfamates also acting as steroid sulfatase inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 2003, 46, 2197–2204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Vullo D.; Innocenti A.; Nishimori I.; Pastorek J.; Scozzafava A.; Pastoreková S.; Supuran C. T. Carbonic anhydrase inhibitors. Inhibition of the transmembrane isozyme XII with sulfonamides—a new target for the design of antitumor and antiglaucoma drugs?. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2005, 15, 963–969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.