Abstract

The human papillomavirus (HPV) E1∧E4 protein is the most abundantly expressed viral protein in HPV-infected epithelia. It possesses diverse activities, including the ability to bind to the cytokeratin network and to DEAD-box proteins, and in some cases induces the collapse of the former. E1∧E4 is also able to prevent the progression of cells into mitosis by arresting them in the G2 phase of the cell cycle. In spite of these intriguing properties, the role of this protein in the life cycle of the virus is not clear. Here we report that after binding to and collapsing the cytokeratin network, the HPV type 16 E1∧E4 protein binds to mitochondria. When cytokeratin is not present in the cell, E1∧E4 appears associated with mitochondria soon after its synthesis. The leucine cluster within the N-terminal portion of the E1∧E4 protein is pivotal in mediating this association. After the initial binding to mitochondria, the E1∧E4 protein induces the detachment of mitochondria from microtubules, causing the organelles to form a single large cluster adjacent to the nucleus. This is followed by a severe reduction in the mitochondrial membrane potential and an induction of apoptosis. HPV DNA replication and virion production occur in terminally differentiating cells which are keratin-rich, rigid squamae that exfoliate after completion of the differentiation process. Perturbation of the cytokeratin network and the eventual induction of apoptotic properties are processes that could render these unyielding cells more fragile and ease the exit of newly synthesized HPVs for subsequent rounds of infection.

Papillomaviruses infect the skin and mucosa of many different hosts, including humans (1). In order to multiply in these tissues, these viruses have evolved and adapted their life cycle to the biology of the epithelium. Human papillomaviruses (HPVs) gain entry into the epithelium via microlesions, which allow them to infect the epithelial basal cells. While the viral episomes remain at a low copy number in basal cells, cellular proliferation leads to the generation of a pool of cells that contain viral DNA. Amplification of the HPV genome and the production of infectious virions do not occur until the infected cells undergo terminal differentiation (11, 19). The amplification of papillomavirus DNA usually begins when infected keratinocytes differentiate into spinous cells (17). This is followed by the production of viral capsid proteins and the assembly of infectious particles. In order to replicate in differentiating cells, the E6 and E7 proteins of HPV stimulate the production of proteins required for DNA synthesis. This causes the differentiating cells to enter S phase (24, 26). The E6 and E7 proteins are able to do this largely because they can inactivate the p53 (32) and pRb (15, 27) proteins, respectively. It is noteworthy that in spite of inactivating two major tumor suppressor functions in the cell, normal productive HPV infections do not cause uncontrolled cellular proliferation leading to tumorigenesis. At most, hyperproliferation of the basal layers may occur, but this is limited, and the infected cells do eventually undergo terminal differentiation. There are instances, however, when the presence of HPV DNA in cells can lead to the onset of cervical cancer (39). Cervical cancers exhibit three common features. Firstly, the viral DNA is almost always integrated into the cellular genome (7); secondly, the E6 and E7 genes are always preserved and expressed; and thirdly, the HPV E2 and E4 genes are lost or not expressed (5). Hence, it appears that prevention against tumorigenesis of HPV-containing cells is lost when accidental integration of the viral DNA disrupts the E2-E4 open reading frames (ORFs) of the virus.

It is understandable why the expression of the HPV E6 and E7 proteins, which are tailored for the express purpose of manipulating the cell's environment to favor HPV DNA replication, can inadvertently induce and support tumorigenesis. However, until recently, it was less clear why the absence of the E2 and E4 proteins was coupled to HPV-induced cancers. These two proteins are encoded by the same DNA strand, but they are translated from different ORFs. The E2 ORF encodes a 42-kDa protein whose principal function is to bind the HPV-encoded E1 protein and to replicate the viral DNA (9, 21). Furthermore, the E2 protein also exhibits cell cycle inhibitory properties, and when expressed at very high levels, is able to induce apoptosis (10, 18, 36). The E4 protein is the most abundantly expressed HPV protein and accumulates in differentiating cells of the upper epithelial layers. It is synthesized from a spliced mRNA, E1∧E4, which encodes five amino acids from the E1 ORF spliced to the protein encoded by the E4 ORF (6, 14, 28). The first activity described for the 10-kDa HPV type 16 (HPV16) E1∧E4 protein was its ability to bind and collapse the cytokeratin network (13). The function of this intriguing property remains speculative, with the most likely explanation being that cytokeratin reorganization serves to facilitate the exit of the virus from the cell. This is especially relevant in view of where mature HPV particles are synthesized. They are made in terminally differentiated squamae that are keratin-rich, and it has been suggested that E4 may contribute to virus release by perturbing the cytokeratin network and increasing cell fragility. In addition to interacting with cytokeratins, E4 also binds to a DEAD-box protein (12). The function of this association is not yet clear, largely because the function of this DEAD-box protein is poorly defined. This notwithstanding, it is known that DEAD-box proteins regulate gene expression at various levels (22, 29). Hence, E1∧E4 may regulate the expression of either cellular or viral genes, or both, by binding to DEAD-box proteins. Lately, the HPV16 E1∧E4 protein was observed to arrest cells at the G2 phase of the cell cycle (8). This activity, which is independent of the association with cytokeratins or DEAD-box proteins, is seen not only in mammalian cells, but also in fission yeast, suggesting that this effect is likely to be elicited via very basic regulatory pathways in the cell. The antiproliferative properties possessed by the E1∧E4 and E2 proteins may be the reason that their absence allows E6- and E7-expressing keratinocytes to undergo continuous proliferation that can lead to the onset of cervical cancer.

We set out to study E1∧E4 function in greater detail by asking what other activities E1∧E4 possesses apart from its interaction with cytokeratins. We report here new properties of the E1∧E4 protein and discuss how these are relevant not only in the context of the viral life cycle, but also in the context of HPV-induced cancers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines, vectors, recombinant viruses, transfection, infection, and antibodies.

HeLa and Saos-2 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle medium containing 5% fetal calf serum, penicillin, and streptomycin. The HPV16 E1∧E4 gene was cloned into the mammalian expression vector MV11 at the BamHI and EcoRI sites and was sequenced. The E4 gene in this vector is under the control of the cytomegalovirus immediate-early promoter (12). A recombinant adenovirus expressing the HPV16 E1∧E4 protein (rAdE1∧E4) was generated with adenovirus type 5 DNA with a deletion of the E1a, E1b, and E3 regions. The HPV16 E1∧E4 gene was expressed under the control of the immediate-early cytomegalovirus promoter. The transfection of HeLa cells was performed by using GenePorter or Lipofectamine 2000 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). Infections of HeLa and Saos-2 cells were carried out with recombinant adenoviruses at a multiplicity of infection of 5. The following antibodies were obtained from various sources: anti-keratin (NeoMarkers), anti-tubulin (Sigma), anti-rhodamine-phalloidin (Sigma), and anti-cytochrome c (Santa Cruz). Mitotracker Red was obtained from Molecular Probes. Annexin V and terminal deoxynucleotidyltransferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay kits were obtained from Roche.

Immunofluorescence staining.

Cells were grown on glass coverslips and infected or transfected with the appropriate vectors. After the designated times, cells were fixed with 5% formalin in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10 min, followed by three rinses with PBS. Permeabilization and blocking were performed with a mixture containing 0.5% NP-40, 5% milk, and 1% fetal calf serum in PBS for 30 min. After a single rinse with PBS, 50 to 100 μl of antibodies diluted appropriately in PBS plus 5% milk was layered on the cells. After 1 h, the cells were washed three times with PBS. Secondary antibodies diluted in PBS plus 5% milk were then layered on the cells; after 30 min, the cells were washed as described above; and after the last washing, the slides with cells were rinsed twice with distilled water. The slides were mounted with a DABCO (30%)-glycerol (70%) solution at pH 7.2.

RESULTS

Association with and collapse of the cytokeratin network by the HPV16 E1∧E4 protein.

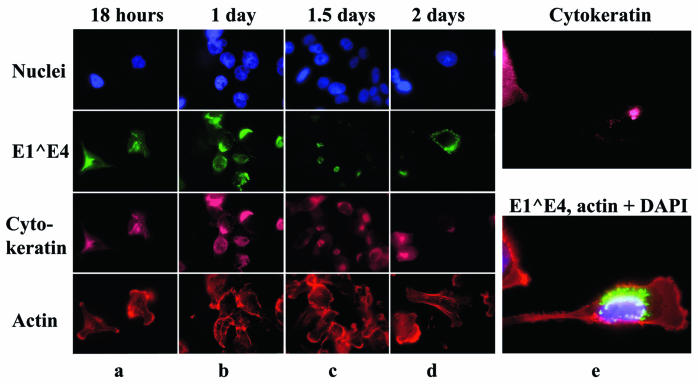

Although HPV16 E1∧E4 expressed from a recombinant vaccinia virus collapses the cytokeratin network very efficiently (13), this approach is not suitable for studying other activities of E1∧E4 because of the lytic nature of vaccinia virus infections. As an alternative, we constructed and used a eukaryotic vector (MV11E1∧E4) that expresses the E1∧E4 protein from the immediate-early promoter of cytomegalovirus. HeLa cells transfected with MV11E1∧E4 showed high levels of E1∧E4 protein expression. Within 18 h, the E1∧E4 proteins were observed to associate with the cytokeratin network of the cell (Fig. 1a). This was followed by the collapse of the cytokeratin network, apparently from the plasma membrane towards the nucleus, leading to the cytokeratin network appearing as a cage around the nucleus (Fig. 1b). Soon after this, the cage-like network was reduced to a single bundle beside the nucleus (Fig. 1c). Importantly, the E1∧E4 protein did not visibly perturb the actin or microtubule networks (also see Fig. 2). After the complete collapse of the cytokeratin network, the continued expression of the protein resulted in E1∧E4 proteins appearing as dots in the cytoplasm (Fig. 1d and e [shows a higher magnification]; other high-magnification images are shown in Fig. 2 and 5). Control experiments showed that cells not expressing E1∧E4 were not stained by an E4-specific antibody, and they did not show the changes attributable to the E1∧E4 protein (for examples, see Fig. 2e, 3a, and 7). Note that the time points reported here are approximate. At each time point, several types of E1∧E4 localization were apparent. The differences lay in the frequency of each type of E1∧E4 localization at any one time. Early after transfection, most cells had E1∧E4 associated with the cytokeratin network, while few cells showed collapsed cytokeratin associated with the E1∧E4 protein and even fewer cells showed E1∧E4 proteins as dots. At later time points, most E1∧E4-expressing cells had collapsed the cytokeratin and most cells exhibited E1∧E4 as cytoplasmic dots. This is consistent with the notion that cells that express a lot of E1∧E4 protein collapse the cytokeratin network more quickly and appear as dots at earlier time points than cells that possess small amounts of the protein.

FIG. 1.

Association of HPV16 E1∧E4 protein with the cytokeratin network. (a to d) HeLa cells were transfected with the MV11E4 vector, and at various times thereafter were fixed and stained as follows: the nuclei were stained with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole), the cytokeratin network was stained with antibodies against keratin, actin was stained with rhodamine-conjugated phalloidin, and E1∧E4 was stained with an Alexa-conjugated anti-E4 antibody. Anti-keratin antibodies were detected with a Cy5-conjugated secondary antibody. The different fluorophores were visualized by using different filters. (e) HeLa cells were transfected with MV11E1∧E4 and stained as described above after 3 days.

FIG. 2.

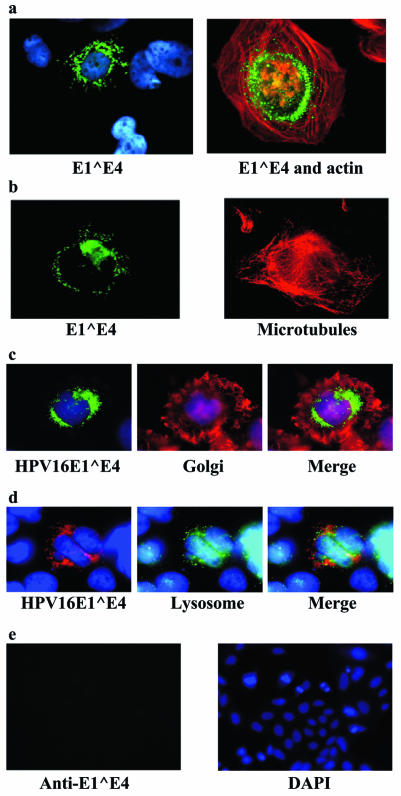

HPV16 E1∧E4 expression in Saos-2 cells lacking cytokeratins. Saos-2 cells were infected with a recombinant adenovirus expressing the E1∧E4 gene (rAdE1∧E4). (a and b) Twenty hours after infection, the cells were fixed and stained for nuclei (blue), E1∧E4 (green), actin (red), and microtubules (also red). (c) Golgi staining. Twenty-four hours after infection, cells were fed wheat germ agglutinin (Molecular Probes) at 1 μg/ml for 15 min, fixed, and processed for immunofluorescence. (d) Lysosome staining. The same procedure was used as that described for panel c, but the cells were fed Lucifer Yellow CH lithium salt (Molecular Probes) at 1 mg/ml. After 1.5 h, they were washed once with fresh medium and incubated in fresh medium without Lucifer Yellow CH for 30 min before being fixed and processed for immunofluorescence. (e) The control vector rAdbeta-galactosidase was used to infect Saos-2 cells at an multiplicity of infection of 100. After 24 h, the cells were fixed and stained with anti-HPV16 E1∧E4 antibodies conjugated to Alexa488. The nuclei were stained with DAPI.

FIG. 5.

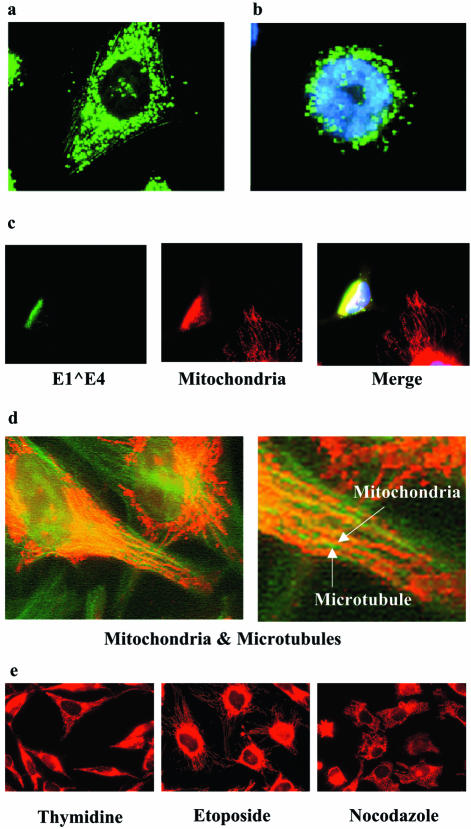

HPV16 E1∧E4-associated mitochondria are displaced from microtubules. Saos-2 cells were infected with rAdE1∧E4, fixed, and then stained with Alexa-conjugated anti-E4 antibodies 24 h (a) and 32 h (b) after infection. (c) HeLa cells were transfected with MV11E1∧E4, fed Mitotracker Red, and then stained with Alexa-conjugated anti-E4 antibodies 48 h after transfection. (d) HeLa cells were fed Mitotracker Red for 15 min, fixed, and stained with antibodies against microtubules. Two magnifications are shown. (e) HeLa cells were treated with thymidine, etoposide, or nocodazole for 24 h, after which Mitotracker Red was added to the medium for 15 min prior to fixing and visualization.

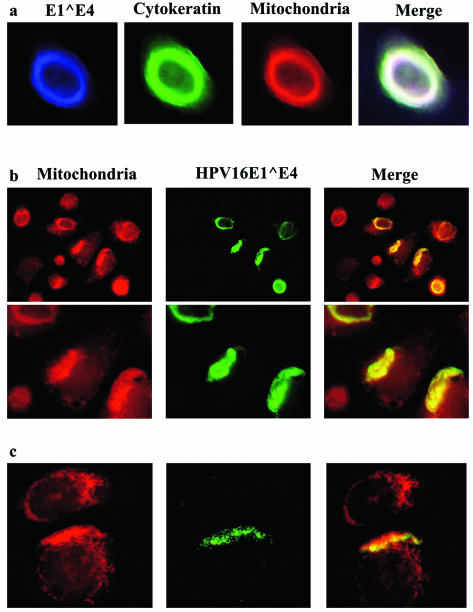

FIG. 3.

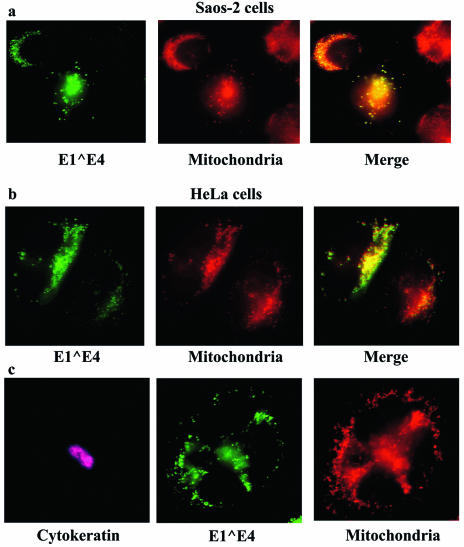

HPV16 E1∧E4 protein associates with mitochondria. (a) Saos-2 cells were infected with rAdE1∧E4, and after 24 h the cells were fed Mitotracker Red. Fifteen minutes later, the cells were fixed and stained with Alexa-conjugated anti-E4 antibodies. (b) HeLa cells were transfected with the MV11E1∧E4 vector, and after 50 h the cells were fed Mitotracker Red and treated as described above for Saos-2 cells. (c) HeLa cells were transfected with MV11E1∧E4. Two days later, Mitotracker Red was added to the medium for 15 min and the cells were fixed and stained for cytokeratin (pink) and E1∧E4 (green) by using appropriate antibodies.

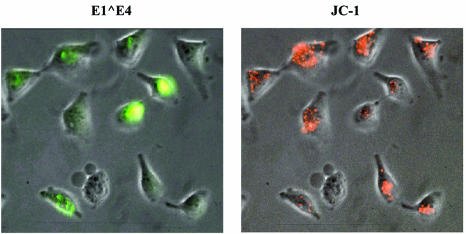

FIG. 7.

E1∧E4 reduces mitochondrial membrane potential. HeLa cells were transfected with MV11E1∧E4. Forty-eighty hours later, the cells were stained with JC-1 for 20 min, analyzed, and photographed, after which the cells were fixed and stained with Alexa-conjugated antibodies against E4 and DAPI.

HPV16 E1∧E4 proteins appear as dots in cells that lack cytokeratins.

To verify whether the appearance of E1∧E4 proteins as dots is dependent on time or on the absence of cytokeratins, we expressed the E1∧E4 protein from Saos-2 cells, an osteosarcoma cell line that expresses vimentin intermediate filaments instead of keratins. Within 24 h of expression, the E1∧E4 protein appeared as dots in all of the cells (Fig. 2a). Importantly, there was no fibrous staining of the E1∧E4 protein. This was the case even at earlier time points after E1∧E4 expression (data not shown). These dots were not associated with the actin (Fig. 2a) or microtubule (Fig. 2b) networks. In addition, these networks were still intact, without any visible alterations. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that when cytokeratins are present in cells, such as HeLa cells, the E1∧E4 protein of HPV16 binds to them efficiently and eventually collapses the cytokeratin network. After this, the E1∧E4 protein appears as dots in the cytoplasm. When cytokeratin is not present in the cell, E1∧E4 appears as dots very soon after its synthesis. Hence, the dotted appearance of E1∧E4 is not dependent on time but seems to be dependent on the absence of cytokeratin.

HPV16 E1∧E4 proteins associate with mitochondria.

The appearance of dots in the cytoplasm could be caused by protein aggregates or could result from the association of E1∧E4 with subcellular structures. Organelle-specific dyes were used to stain cells expressing the E1∧E4 protein. Staining for the Golgi apparatus and lysosomes did not convincingly exhibit colocalization with the E1∧E4 dots (Fig. 2c and d). The expression of a protein unrelated to E1∧E4 gave no staining with the E4-specific antibody at all (Fig. 2e). Mitochondrial staining with Mitotracker Red (Molecular Probes), however, showed an exact colocalization of these organelles with E1∧E4 (Fig. 3a). To determine if this would also be seen in keratin-containing cells after the collapse of the cytokeratin network, we tested E1∧E4 for a mitochondrial association in HeLa cells. As was the case for Saos-2 cells, the E1∧E4 protein in HeLa cells associated with the mitochondria (Fig. 3b), and this occurred after the collapse of the cytokeratin network (Fig. 3c).

To follow up this intriguing observation by using keratinocytes, we expressed the HPV16 E1∧E4 protein in W12 cells. These are keratinocytes that are derived from a low-grade cervical lesion and that harbor approximately 1,000 episomal copies of HPV DNA per cell. When ectopically expressed in these cells, the E1∧E4 protein not only bound to cytokeratins but also associated with mitochondria. As a consequence, mitochondria, together with the cytokeratin network, were localized to the perimeter of the nuclei (Fig. 4a). Interestingly, when the cytokeratin network was observed as a bundle adjacent to the nucleus, the majority of mitochondria were also thus localized (Fig. 4b; the field shown includes some cells that are negative for E4 serving as an internal negative control for the anti-E4 antibody). In some W12 cells, the E1∧E4 staining was dot-like and clearly localized to the mitochondria (Fig. 4c). Although not all of the mitochondria were bound by E1∧E4, the majority were. This observation revealed that the binding of E1∧E4 to mitochondria is not necessarily a late event that only occurs after the collapse and disappearance of the cytokeratin network, as observed in HeLa cells. Instead, the mitochondrial association and cytokeratin association can occur simultaneously. It is noteworthy that the expression of HPV16 E1∧E4 in W12 cells is always transient. For reasons that are not known to us, the protein is expressed in only a subset of transfected or infected cells, and even in these cells, expression soon ceases. Although this is also observed with Saos-2 and HeLa cells, these cells are better at expressing HPV16 E1∧E4, with at least a small proportion (<5%) of cells continuing expression even after 72 h.

FIG. 4.

Colocalization of HPV16 E1∧E4 protein with mitochondria and cytokeratin in W12 keratinocytes. (a) W12 cells were infected with rAdE1∧E4 for 24 h, after which Mitotracker Red was added to the cells. The cells were fixed and stained with antibodies against rAdE1∧E4 (blue) and pan-cytokeratin (green). (b) The same procedure was used as that described for panel a, but different magnifications were used. Cells were stained with antibodies against rAdE1∧E4 (green) and with Mitotracker Red. Pictures in the bottom row are at a higher magnification than those in the top row. (c) Same as panel b, but showing granular mitochondrial and E4 staining in some W12 cells.

E1∧E4-associated mitochondria are displaced from their usual location on microtubules.

Initially, the E1∧E4-mitochondrion dots were evenly distributed in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5a), but they later localized around the nucleus (Fig. 5b) and eventually formed a single cluster adjacent to the nucleus (Fig. 5c). Hence, in addition to associating with mitochondria, the E1∧E4 protein causes mitochondria to be relocalized. To further study this relocalization, we first verified whether mitochondria were indeed located on the microtubule network as was previously described (2). Mitotracker Red was added to the medium of the cells for 20 min prior to fixing and staining of the cells with antibodies against microtubules (Fig. 5d). The results showed that the array of mitochondria ran parallel to that of the microtubule network. At a higher magnification (Fig. 5d, right panel), the mitochondria were seen to be arranged on the microtubule fibers. Interestingly, as was pointed out above, the microtubule networks in E1∧E4-expressing cells were not perturbed (Fig. 2b). Hence, E1∧E4 proteins relocalize mitochondria by removing them from the microtubule network without disrupting the latter. Consistent with this observation, the disruption of microtubules by nocodazole did not result in the redistribution of the mitochondria into a single cluster as did E1∧E4. Instead, the mitochondria in nocodazole-treated cells were mostly dispersed randomly throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 5e).

Mitochondria are attached to microtubules via associations with several proteins, two of which, dynein and kinesin, are motor proteins (20, 23, 34). Costaining of E1∧E4 and kinesin or dynein did not reveal any convincing colocalization between these proteins (data not shown). Since the E1∧E4 protein can induce the arrest of cells in the G2 phase (8), the displacement of the mitochondria from the microtubules could be a consequence of this arrest. To test this, we arrested cells at various phases of the cell cycle by using specific drugs and stained their mitochondria with Mitotracker Red. Cells blocked at the late G1 and early S phases by thymidine exhibited a mitochondrial distribution that was uniform throughout the cytoplasm. Mitochondria in cells blocked at G2 by treatment with etoposide were concentrated around the nucleus, while mitochondria in nocodazole-treated cells were disorganized throughout the cytoplasm (Fig. 5e). The results showed that while mitochondrial localization and distribution change with the cell cycle, the aggregation of mitochondria into a single cluster beside the nucleus, as induced by E1∧E4, is not an event that occurs during any phase of the normal cell cycle.

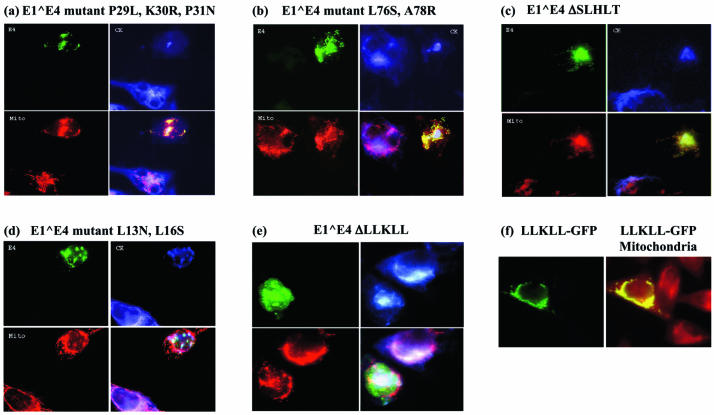

The leucine cluster of HPV16 E1∧E4 is necessary and sufficient to mediate the association with mitochondria.

To determine which region of the E1∧E4 protein is responsible for mitochondrial association, we expressed four E1∧E4 mutants in cells and stained for their presence and localization. The mutants are summarized in Table 1. The P29L K30R P31N mutant is an E1∧E4 protein whose proline-rich region has been disrupted by point mutations. The L76S A78R mutant is an E1∧E4 mutant protein with changes to two amino acids (residues 76 and 78) that are conserved in other E1∧E4 proteins of mucosal HPVs. The L13N L16S mutant is an E1∧E4 protein whose leucine cluster has been disrupted by the replacement of two leucine residues with asparagine and serine, respectively. The ΔSLHLT mutant is an E1∧E4 protein with a deletion of five amino acids within the region that is conserved between the E1∧E4 proteins of mucosal HPVs.

TABLE 1.

HPV16 E1∧E4 mutant protein sequences

| Protein | Sequencea |

|---|---|

| E1∧E4wt | MADPAAATKYPLLKLLGSTWPTTPPRPIPKPSPWAPKKHRRLSSDQDQSQTPETPATPLSCCTETQWTVLQSSLHLTAHTKDGLTVIVTLHP |

| E1∧E4 P29L K30R P31N | MADPAAATKYPLLKLLGSTWPTTPPRPILRNSPWAPKKHRRLSSDQDQSQTPETPATPLSCCTETQWTVLQSSLHLTAHTKDGLTVIVTLHP |

| E1∧E4 L76S A78R | MADPAAATKYPLLKLLGSTWPTTPPRPIPKPSPWAPKKHRRLSSDQDQSQTPETPATPLSCCTETQWTVLQSSLHSTRHTKDGLTVIVTLHP |

| E1∧E4 L13N L16S | MADPAAATKYPLNKLSGSTWPTTPPRPIPKPSPWAPKKHRRLSSDQDQSQTPETPATPLSCCTETQWTVLQSSLHLTAHTKDGLTVIVTLHP |

| E1∧E4 ΔSLHLT | MADPAAATKYPLLKLLGSTWPTTPPRPIPKPSPWAPKKHRRLSSDQDQSQTPETPATPLSCCTETQWTVLQS-----AHTKDGLTVIVTLHP |

| E1∧E4 ΔLLKLL | MADPAAATKYP-----GSTWPTTPPRPIPKPSPWAPKKHRRLSSDQDQSQTPETPATPLSCCTETQWTVLQSSLHLTAHTKDGLTVIVTLHP |

The leucine cluster, the proline-rich region, and the mucosal homology domain are indicated with italics, bold-type, and underlining, respectively.

E1∧E4 proteins with mutations in either the proline-rich domain or the mucosal HPV conserved region retained the abilities to collapse the cytokeratin network and to associate with mitochondria (Fig. 6a to c). Although the E1∧E4 protein with point mutations within the leucine cluster could still bind and disrupt the cytokeratin network, its ability to do so was somewhat diminished. Importantly, this protein could not associate with mitochondria (Fig. 6d). An E1∧E4 mutant (E4ΔLLKLL) that lacks the entire leucine cluster was also defective in associating with the mitochondria (Fig. 6e). Since this mutant also could not associate with cytokeratins, it could be argued that this is the cause of the protein's inability to bind mitochondria. However, proof that the leucine cluster of HPV16 E1∧E4 is the mitochondrion localization signal is provided by the targeting of green fluorescent protein to the mitochondria when the former was fused to the HPV E1∧E4 leucine cluster (Fig. 6f).

FIG. 6.

The leucine cluster of E1∧E4 is required to mediate its association with mitochondria. (a to e) HeLa cells were transfected with E1∧E4 mutants in vector MV11. Approximately 60 h later, Mitotracker Red was added for 15 min and the cells fixed and stained with antibodies against keratin (revealed with Cy5-conjugated secondary antibodies) (blue) and Alexa-conjugated antibodies against E1∧E4 (green). Mitochondria are stained red. (f) HeLa cells were transfected with the MV11LLKLLGFP vector, which expresses GFP fused to the leucine cluster sequence from HPV16 E1∧E4. Fifty hours later, the cells were fed Mitotracker Red and fixed. LLKLLGFP is stained green and mitochondria are stained red.

E1∧E4 protein severely reduces mitochondrial membrane potential.

To ascertain whether the E1∧E4 protein, by associating with the mitochondria, affects their membrane potential, we expressed E1∧E4 from Saos-2 or HeLa cells, followed by staining of the mitochondria with JC-1, a membrane-potential-dependent dye that stains very active mitochondria red. Cells expressing high levels of E1∧E4 exhibited much reduced JC-1 staining, whereas adjacent cells expressing low or undetectable levels of E1∧E4, serving as internal controls, did not. The results revealed that E1∧E4-containing cells show a marked reduction in highly active mitochondria (Fig. 7). Although the reduction of JC-1 staining could be interpreted as a sign that the mitochondria were not functioning, this is unlikely to be the case since Mitotracker Red, also a membrane-potential-dependent dye, clearly stained E1∧E4-associated mitochondria (Fig. 3 to 5). Mitotracker Red, a much more sensitive and fixable dye, stains red regardless of the magnitude of the membrane potential. We have not observed any E1∧E4 dots in cells that did not also stain with Mitotracker Red. Together, these results indicate that although E1∧E4 clearly causes a marked drop in the mitochondrial membrane potential, it does not cause a complete loss of the potential.

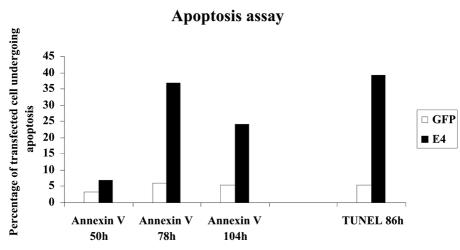

HPV16 E1∧E4 protein induces apoptosis.

To determine if the reduction in the membrane potential of mitochondria was caused by large pores in the membrane, which would also allow the exit of other mitochondrial components, we expressed the E1∧E4 protein and then looked at the localization of cytochrome c in these cells. Staining showed that the cytochrome c in E1∧E4-expressing cells was confined within the mitochondria (data not shown). This was also the case in cells whose mitochondrial distribution was disrupted by E1∧E4. Hence, it is unlikely that large pores are made in the mitochondrial membrane to allow a major efflux of mitochondrial components into the cytoplasm. However, 36% of E1∧E4-expressing cells were positive for annexin V staining and 39% of E1∧E4-positive cells were also positive in a TUNEL assay, both of which are indicators of apoptosis (Fig. 8). Importantly, apoptosis was maximal approximately 80 h after E1∧E4 expression. This may infer that apoptosis is initiated only after a threshold level of E1∧E4 protein is attained. When taken together, these observations suggest that although the HPV16 E1∧E4 protein does not appear to induce gross visible damage to the mitochondria, it can induce apoptosis in the long term. Clearly, not all E1∧E4-expressing cells undergo apoptosis, and it is conceivable that cells that do are those that express E1∧E4 at high levels.

FIG. 8.

HPV16 E1∧E4 induces apoptosis. HeLa cells were transfected with MV11E1∧E4, and after the indicated times, they were either stained with an anti-annexin V antibody or subjected to a TUNEL assay. After photography, the cells were fixed and stained with Alexa-conjugated antibodies against E4. The results were scored as the percentages of apoptotic cells among the E1∧E4-expressing cells or of apoptotic cells among control GFP-expressing cells.

DISCUSSION

The HPV16 E1∧E4 protein associates efficiently and rapidly with the cytokeratin network by interacting directly with cytokeratins (35), although the binding may be enhanced in the presence of other proteins. Keratin association leads to the eventual reorganization of the cytokeratin network in vivo as well as in vitro (35). Interestingly, the collapse of the network appears to initiate from the plasma membrane, and it has been suggested that HPV16 E1∧E4 may destabilize the keratin network by acting as a specific cross-linker (35). Once collapsed, the cytokeratin appears as a cluster beside the nucleus. The work we report here suggests that further expression of E1∧E4 results in the protein appearing as dots in the cytoplasm and that these dots correspond to mitochondria. The time dependence and step-wise fashion of these two activities in HeLa cells suggest that the E1∧E4 protein has a higher affinity for cytokeratin than for mitochondria. However, this was not the case in W12 keratinocytes, in which E1∧E4 was seen to associate with cytokeratin and mitochondria at the same time. This difference may be caused by a higher affinity of E1∧E4 for the keratin types present in HeLa cells than for those in W12 cells. Whatever the reason, it is clear that E1∧E4 can associate with both cytokeratins and mitochondria. Since E1∧E4 rarely collapses the cytokeratin network entirely in vivo, the association of E1∧E4 with mitochondria is difficult to detect, as it is masked by the extensive E1∧E4-cytokeratin staining. However, cells lacking (Saos-2) or with low levels of (HeLa) cytokeratin permit the visualization of the E1∧E4-mitochondria interaction.

During the course of our investigations, we consistently observed that although we could transfect or infect cells efficiently, only a subset of the cells actually expressed the E1∧E4 protein. This was particularly stark for W12 cells. Furthermore, of the subpopulation of cells that expressed E1∧E4, only a very small percentage continued to make the protein after 3 or 4 days. The reason for this transient expression is not known, but it has been observed by others and is a stumbling block to carrying out biochemical experiments and Western blot analyses. This feature may be linked to the observation that HPV L1 and L2 proteins are poorly expressed (if at all) in proliferating cells but are synthesized in differentiating cells. Since HPV16 E1∧E4 is produced in great abundance in differentiating epithelial cells and is barely detectable in basal cells, it would be interesting to determine whether the expression of this protein is also limited by mechanisms similar to those inhibiting L1 and L2 expression.

The use of E1∧E4 mutants allowed the dissection of the protein's various activities and the assignment of these activities to specific parts of the protein. The N-terminal region of the E1∧E4 protein was shown to be responsible for targeting the protein to cytokeratin (31). The C-terminal domain (at least the last 27 amino acid residues) is required for the binding of E1∧E4 to the DEAD-box protein (12), and the region between amino acids 17 and 45 was shown to be responsible for arresting cells at the G2 phase of the cell cycle (8). The present work revealed that the leucine cluster LLKLL, when mutated, fails to target the E1∧E4 protein to the mitochondria. This was also seen with an E4 mutant that lacked the LLKLL sequence altogether. The fact that the LLKLL sequence is required and sufficient for this activity was confirmed by the use of an LLKLL-green fluorescent protein (GFP) fusion protein which also targeted mitochondria. Other mitochondrion-targeting protein sequences have been identified previously, but they differ from that of E1∧E4 in sequence and length (38). It is intriguing that the E1∧E4 mitochondrion-targeting sequence is so short. It is unlikely that all proteins possessing an LLKLL sequence will be localized to the mitochondria. Other factors that are as yet unknown are likely to influence the final outcome. The LLKLL region, together with the 12 preceding amino acids, is required for the interaction of E1∧E4 with the cytokeratin network (31, 35). Hence, it appears that the LLKLL region serves at least two functions, depending on the context of the protein.

The E1∧E4 protein does more than just associate with mitochondria, as their distribution is greatly perturbed: the mitochondria, which are normally aligned on the microtubule network, are displaced and aggregated. Intriguingly, this is executed without disruption of the microtubules. The possibility that microtubule motor proteins are targets of E1∧E4 was dispelled when antibodies against kinesin and dynein did not convincingly colocalize with E1∧E4 in the cell. Changes to the mitochondrial distribution in the cell during the cell cycle could theoretically be responsible for their redistribution. This is especially significant in view of E1∧E4's ability to impose a G2 arrest. This possibility was tested by observing cells arrested at G1, G2, or the mitotic phase. Mitochondria in G1 cells were uniformly distributed throughout the cytoplasm, while those in G2 cells accumulated around the periphery of the nucleus. When microtubules were disrupted, the mitochondrial distribution was disorganized and haphazard. None of these changes resembled those induced by E1∧E4. Hence, we conclude that cell cycle arrest in G2 or any other phase is not the means by which E1∧E4 induces the change in mitochondrial distribution. The collapse of cytokeratin, the establishment of a G2 block, and the disruption of the normal mitochondrial distribution appear to be uncoupled activities.

Bryan et al. (4) have previously shown that the E1∧E4 proteins can self-associate. Recent studies have suggested that HPV16 E1∧E4 can act as a keratin cross-linker and can cause keratin reorganization by bundling keratin filaments together (35). It is possible that under such circumstances, mitochondria are also tethered to the keratin filaments and become reorganized as the keratin filaments are rearranged. The different cytoskeletal proteins in the cell do interact with each other. Our observations with W12 cells, in which E1∧E4, mitochondria, and cytokeratins colocalized, lend support to this reasoning. This cross-linking ability of E1∧E4 would also be expected to cluster mitochondria in the absence of cytokeratin, as was seen with Saos-2 cells.

How E1∧E4 actually targets and disrupts the mitochondrial distribution remains to be elucidated. This notwithstanding, its consequence can be assessed. The main function of mitochondria is the generation of ATP, and a prerequisite for this is a potential difference between the mitochondrial membranes. Our experiments showed that E1∧E4 severely reduces the mitochondrial membrane potential. Either a gross rupture of the mitochondrial membrane or the opening of membrane channels could cause a depletion of the membrane potential. Since cytochrome c, a 12-kDa protein which rapidly escapes from the mitochondria to the cytosol during apoptosis, appeared to be confined within E1∧E4-associated mitochondria, it is fair to conclude that whatever E1∧E4 does to reduce membrane potential, it is not via the creation of large pores that would allow a rapid cytochrome c efflux. Cytochrome c could seep out at a low rate that is not detectable by the qualitative method of analysis used here. However, annexin V and TUNEL assays, which score the death of individual cells, revealed that approximately 35% of E1∧E4-expressing cells died. The cell death rate was highest approximately 80 h after the expression of the E1∧E4 protein, supporting the idea that this protein must be present either at high levels or for a prolonged period of time before death is induced. The E1∧E4 protein is present at exceedingly high levels during a natural HPV infection, especially in terminally differentiated cells of the epithelium, where it can comprise as much as 30% of the total cellular protein in lesions caused by HPV1. Hence, the induction of apoptosis by high levels of E1∧E4 cannot be attributed to nonphysiological levels of E1∧E4 protein in the cell. The slowness of cell death is consistent with the absence of a rapid loss of cytochrome c from the mitochondria.

It is important to remember that in the in vivo epithelium, E1∧E4 is expressed in terminally differentiating cells and that there are shared features between terminally differentiating cells and apoptotic cells. Weil et al. (37) demonstrated that caspase 3 is activated during normal epidermal differentiation, consistent with the observation that caspase inhibitors prevent the loss of nuclei during normal epithelial terminal differentiation. In addition, caspase 14 (16, 30) is specifically expressed in granular cells of the epithelium. Therefore, one may question whether there is a need for E1∧E4 to induce apoptosis. This question can be addressed by considering the main difference between apoptosis and terminal differentiation, which is that unlike apoptotic cells, terminally differentiated cells are not fragmented or lysed and subsequently phagocytosed. Instead, terminally differentiated keratinocytes are keratin-rich, rigid squamae that finally exfoliate. It is in these unyielding cells that HPV particles are synthesized and from which they must escape. In this light, the perturbation of the cytokeratin network and the eventual induction of apoptosis are processes that would render these cells more fragile and therefore ease the exit of newly synthesized HPVs. While this is not currently testable, continued improvements in cell culture systems for HPV production and assay should permit such investigations in the near future. The characteristics of skin diseases which are characterized by fragile epithelia resulting from a defective cytokeratin network (33), such as epidermolysis bullosa simplex, support the postulate that HPV-containing cells may be made pliable by a weakened cytokeratin network and rendered more fragile by apoptotic processes. Although apoptosis was observed in a subset of nondifferentiated cells expressing E1∧E4, care must be taken when extrapolating this observation to cells of the stratified epithelium. Since these cells are already differentiated to various degrees, it is quite possible that the familiar manifestations of apoptosis are not seen in these cells. This, however, does not mean that other less obvious properties of apoptosis that may be beneficial to HPV are not at work. It is interesting that E1∧E4 from HPV11 has been shown to associate with cornified envelopes (3) and to compromise their integrity. Collectively, the multiple activities of E1∧E4 that can physically weaken the host cell (cytokeratin rearrangement, an increased fragility of cornified envelopes, and apoptosis) bear witness to how important this feature is to the life cycle of the virus.

The activities of the E1∧E4 protein described above and reported previously are unlikely to promote cellular proliferation; rather, they would inhibit it. This may be the reason why, in spite of the ability of the E6 and E7 proteins to inactivate two tumor suppressor functions in the cell, HPV-containing cells do not progress to cancer. In the absence of E1∧E4 expression, as happens when the integrated HPV DNA is accidentally interrupted at the E4 ORF during viral DNA integration, E6- and E7-expressing cells acquire an increased proliferative capacity, setting the cell in the direction of tumorigenesis (25). The results reported here bear meaning not only for the life cycle of HPVs but also for the nature of the involvement of HPVs in cervical cancers.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sally Roberts for the kind gift of the E1∧E4ΔSLHLT and E1∧E4ΔLLKLL DNA clones to J.D.

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation, NCCR Molecular Oncology, and Cancer Research Switzerland. J.D. was supported by the United Kingdom Medical Research Council and the Royal Society.

REFERENCES

- 1.Antonsson, A., and B. G. Hansson. 2002. Healthy skin of many animal species harbors papillomaviruses which are closely related to their human counterparts. J. Virol. 76:12537-12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball, E. H., and S. J. Singer. 1982. Mitochondria are associated with microtubules and not with intermediate filaments in cultured fibroblasts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 79:123-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bryan, J. T., and D. R. Brown. 2000. Association of the human papillomavirus type 11 E1-E4 protein with cornified cell envelopes derived from infected genital epithelium. Virology 277:262-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bryan, J. T., K. H. Fife, and D. R. Brown. 1998. The intracellular expression pattern of the human papillomavirus type 11 E1-E4 protein correlates with its ability to self associate. Virology 241:49-60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Choo, K. B., C. C. Pan, and S. H. Han. 1987. Integration of human papillomavirus type 16 into cellular DNA of cervical carcinoma: preferential deletion of the E2 gene and invariable retention of the long control region and the E6/E7 open reading frames. Virology 161:259-261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chow, L. T., S. S. Reilly, T. R. Broker, and L. B. Taichman. 1987. Identification and mapping of human papillomavirus type 1 RNA transcripts recovered from plantar warts and infected epithelial cell cultures. J. Virol. 61:1913-1918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cullen, A. P., R. Reid, M. Campion, and A. T. Lorincz. 1991. Analysis of the physical state of different human papillomavirus DNAs in intraepithelial and invasive cervical neoplasm. J. Virol. 65:606-612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davy, C. E., D. J. Jackson, Q. Wang, K. Raj, P. J. Masterson, N. F. Fenner, S. Southern, S. Cuthill, J. B. Millar, and J. Doorbar. 2002. Identification of a G(2) arrest domain in the E1 wedge E4 protein of human papillomavirus type 16. J. Virol. 76:9806-9818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Del Vecchio, A. M., H. Romanczuk, P. M. Howley, and C. C. Baker. 1992. Transient replication of human papillomavirus DNAs. J. Virol. 66:5949-5958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desaintes, C., S. Goyat, S. Garbay, M. Yaniv, and F. Thierry. 1999. Papillomavirus E2 induces p53-independent apoptosis in HeLa cells. Oncogene 18:4538-4545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doorbar, J. 1998. Late stages of the papillomavirus life cycle. Papillomavirus Rep. 9:119-123. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Doorbar, J., R. C. Elston, S. Napthine, K. Raj, E. Medcalf, D. Jackson, N. Coleman, H. M. Griffin, P. Masterson, S. Stacey, Y. Mengistu, and J. Dunlop. 2000. The E1E4 protein of human papillomavirus type 16 associates with a putative RNA helicase through sequences in its C terminus. J. Virol. 74:10081-10095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Doorbar, J., S. Ely, J. Sterling, C. McLean, and L. Crawford. 1991. Specific interaction between HPV-16 E1-E4 and cytokeratins results in collapse of the epithelial cell intermediate filament network. Nature 352:824-827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Doorbar, J., A. Parton, K. Hartley, L. Banks, T. Crook, M. Stanley, and L. Crawford. 1990. Detection of novel splicing patterns in an HPV16-containing keratinocyte cell line. Virology 178:254-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dyson, N., P. M. Howley, K. Munger, and E. Harlow. 1989. The human papilloma virus-16 E7 oncoprotein is able to bind to the retinoblastoma gene product. Science 243:934-937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eckhart, L., W. Declercq, J. Ban, M. Rendl, B. Lengauer, C. Mayer, S. Lippens, P. Vandenabeele, and E. Tschachler. 2000. Terminal differentiation of human keratinocytes and stratum corneum formation is associated with caspase-14 activation. J. Investig. Dermatol. 115:1148-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egawa, K., A. Iftner, J. Doorbar, Y. Honda, and T. Iftner. 2000. Synthesis of viral DNA and late capsid protein L1 in parabasal spinous cell layers of naturally occurring benign warts infected with human papillomavirus type 1. Virology 268:281-293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fournier, N., K. Raj, P. Saudan, S. Utzig, R. Sahli, V. Simanis, and P. Beard. 1999. Expression of human papillomavirus 16 E2 protein in Schizosaccharomyces pombe delays the initiation of mitosis. Oncogene 18:4015-4021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frattini, M. G., H. B. Lim, J. Doorbar, and L. A. Laimins. 1997. Induction of human papillomavirus type 18 late gene expression and genomic amplification in organotypic cultures from transfected DNA templates. J. Virol. 71:7068-7072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habermann, A., T. A. Schroer, G. Griffiths, and J. K. Burkhardt. 2001. Immunolocalization of cytoplasmic dynein and dynactin subunits in cultured macrophages: enrichment on early endocytic organelles. J. Cell Sci. 114:229-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hibma, M. H., K. Raj, S. J. Ely, M. Stanley, and L. Crawford. 1995. The interaction between human papillomavirus type 16 E1 and E2 proteins is blocked by an antibody to the N-terminal region of E2. Eur. J. Biochem. 229:517-525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iost, I., and M. Dreyfust. 1994. mRNA can be stabilised by DEAD-box proteins. Nature 372:193-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khodjakov, A., E. M. Lizunova, A. A. Minin, M. P. Koonce, and F. K. Gyoeva. 1998. A specific light chain of kinesin associates with mitochondria in cultured cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 9:333-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mantovani, F., and L. Banks. 2001. The human papillomavirus E6 protein and its contribution to malignant progression. Oncogene 20:7874-7887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Middleton, K., W. Peh, S. A. Southern, H. M. Griffin, K. Sotlar, T. Nakahara, A. El-Sherif, L. Morris, R. Seth, M. Hibma, D. Jenkins, P. F. Lambert, N. Coleman, and J. Doorbar. 2003. Organization of human papillomavirus productive cycle during neoplastic progression provides a basis for selection of diagnostic markers. J. Virol. 77:10186-10201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Munger, K., J. R. Basile, S. Duensing, A. Eichten, S. L. Gonzalez, M. Grace, and V. L. Zacny. 2001. Biological activities and molecular targets of the human papillomavirus E7 oncoprotein. Oncogene 20:7888-7898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Munger, K., B. A. Werness, N. Dyson, W. C. Phelps, E. Harlow, and P. M. Howley. 1989. Complex formation of human papillomavirus E7 proteins with the retinoblastoma tumor suppressor gene product. EMBO J. 8:4099-4105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nasseri, M., R. Hirochika, T. R. Broker, and L. T. Chow. 1987. A human papillomavirus type 11 transcript encoding an E1∧E4 protein. Virology 159:433-439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pause, A., and N. Sonenberg. 1992. Mutational analysis of a DEAD-box RNA helicase: the mammalian translation initiation factor eIF-4A. EMBO J. 11:2643-2654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rendl, M., J. Ban, P. Mrass, C. Mayer, B. Lengauer, L. Eckhart, W. Declerq, and E. Tschachler. 2002. Caspase-14 expression by epidermal keratinocytes is regulated by retinoids in a differentiation-associated manner. J. Investig. Dermatol. 119:1150-1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roberts, S., I. Ashmole, S. Rookes, and P. Gallimore. 1997. Mutational analysis of the human papillomavirus type 16 E1∧E4 protein shows that the C terminus is dispensable for keratin cytoskeleton association but is involved in inducing disruption of the keratin filaments. J. Virol. 71:3554-3562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Scheffner, M., B. A. Werness, J. M. Huibregtse, A. J. Levine, and P. M. Howley. 1990. The E6 oncoprotein encoded by human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 promotes the degradation of p53. Cell 63:1129-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith, F. 2003. The molecular genetics of keratin disorders. Am. J. Clin. Dermatol. 4:347-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tanaka, Y., Y. Kanai, Y. Okada, S. Nonaka, S. Takeda, A. Harada, and N. Hirokawa. 1998. Targeted disruption of mouse conventional kinesin heavy chain, kif5B, results in abnormal perinuclear clustering of mitochondria. Cell 93:1147-1158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang, Q., S. Griffin, S. Southern, D. Jackson, A. Martin, P. McIntosh, C. Davy, P. Masterson, P. Walker, P. Laskey, M. Omary, and J. Doorbar. 2004. Functional analysis of the human papillomavirus type 16 E1∧E4 protein provides a mechanism for in vivo and in vitro keratin filament reorganization. J. Virol. 78:821-833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Webster, K., J. Parish, M. Pandya, P. L. Stern, A. R. Clarke, and K. Gaston. 2000. The human papillomavirus (HPV) 16 E2 protein induces apoptosis in the absence of other HPV proteins and via a p53-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 275:87-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weil, M., M. C. Raff, and V. M. Braga. 1999. Caspase activation in the terminal differentiation of human epidermal keratinocytes. Curr. Biol. 9:361-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang, C., A. Sriratana, T. Minamikawa, and P. Nagley. 1998. Photosensitisation properties of mitochondrially localised green fluorescent protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 242:390-395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.zur Hausen, H. 1987. Papillomaviruses in human cancer. Cancer 59:1692-1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]