Abstract

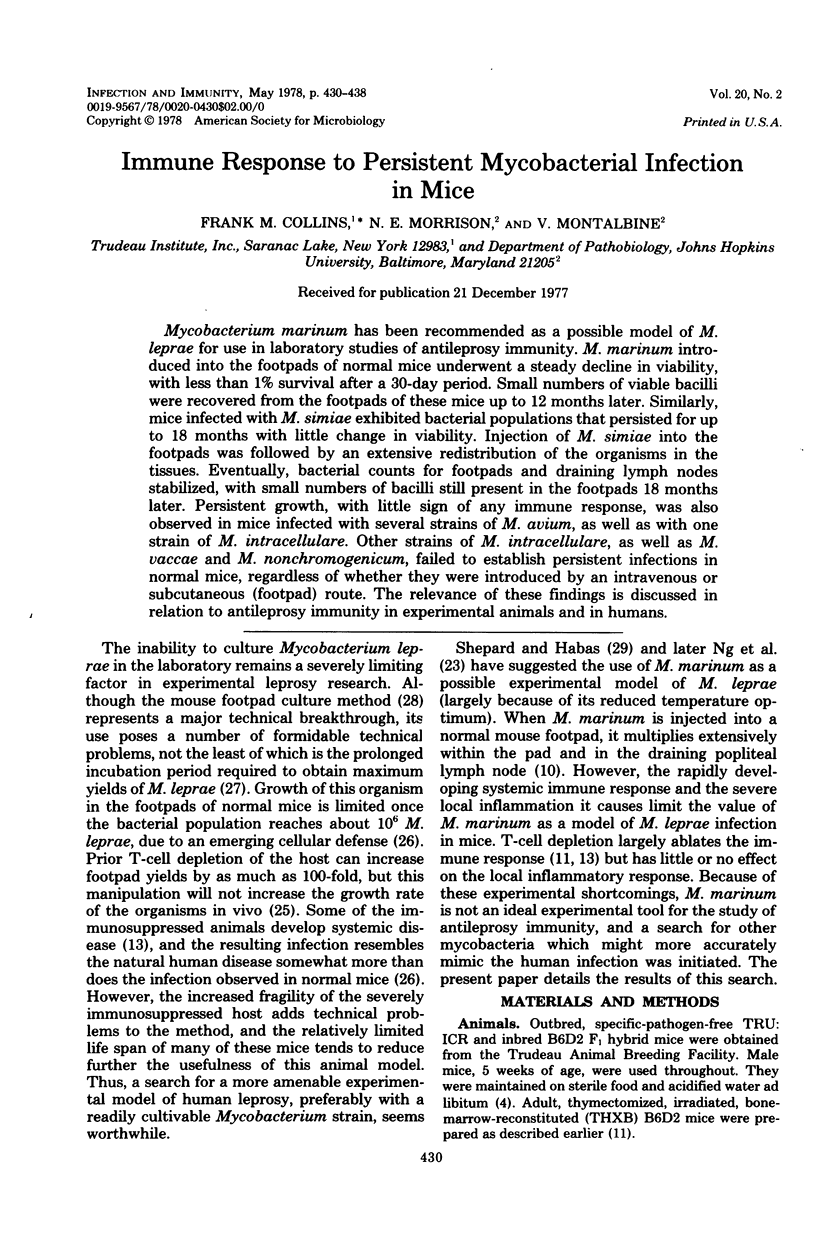

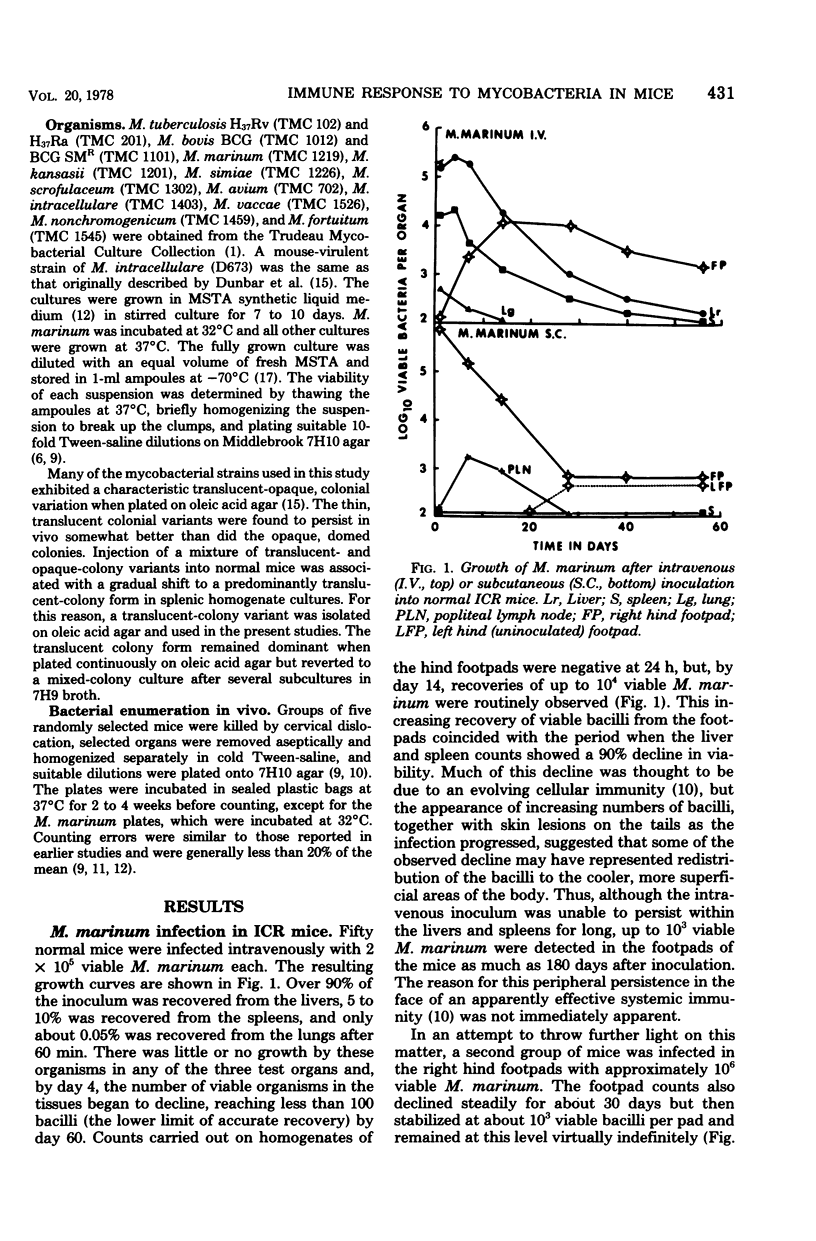

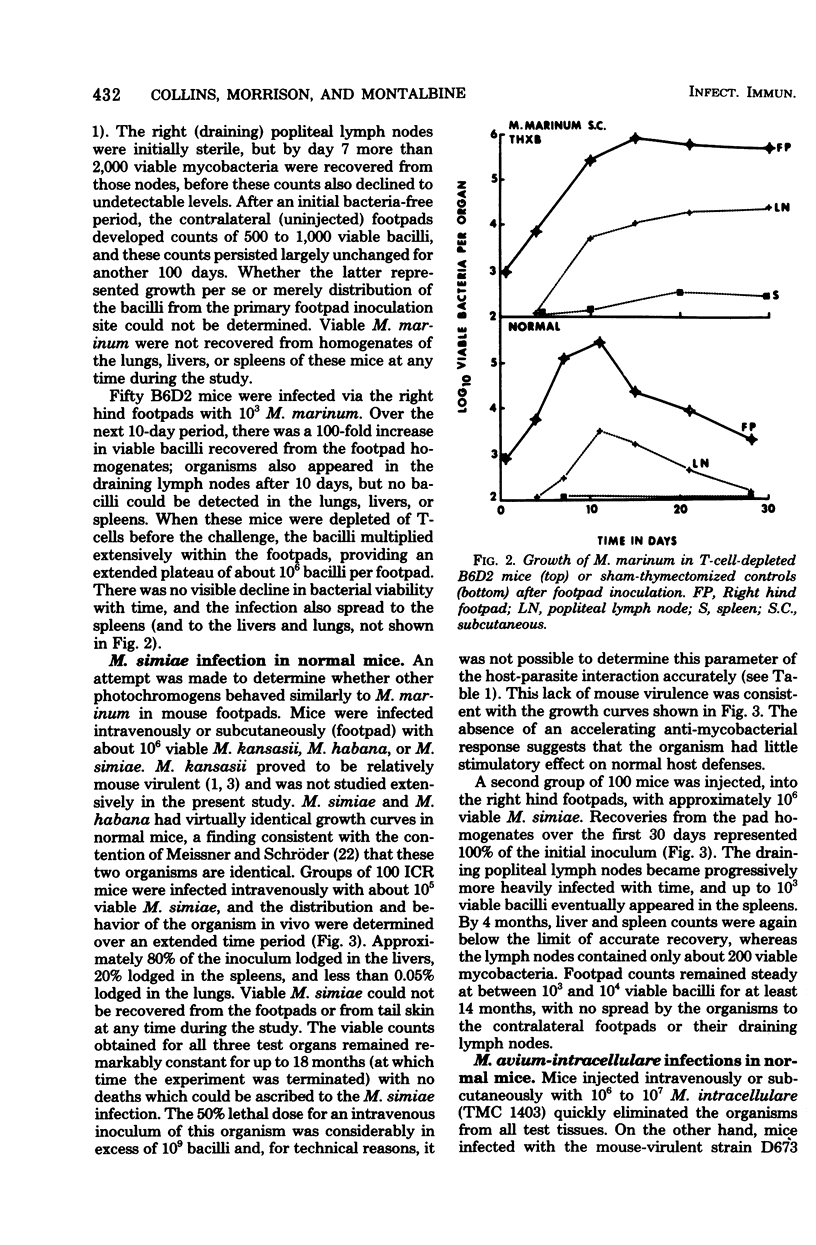

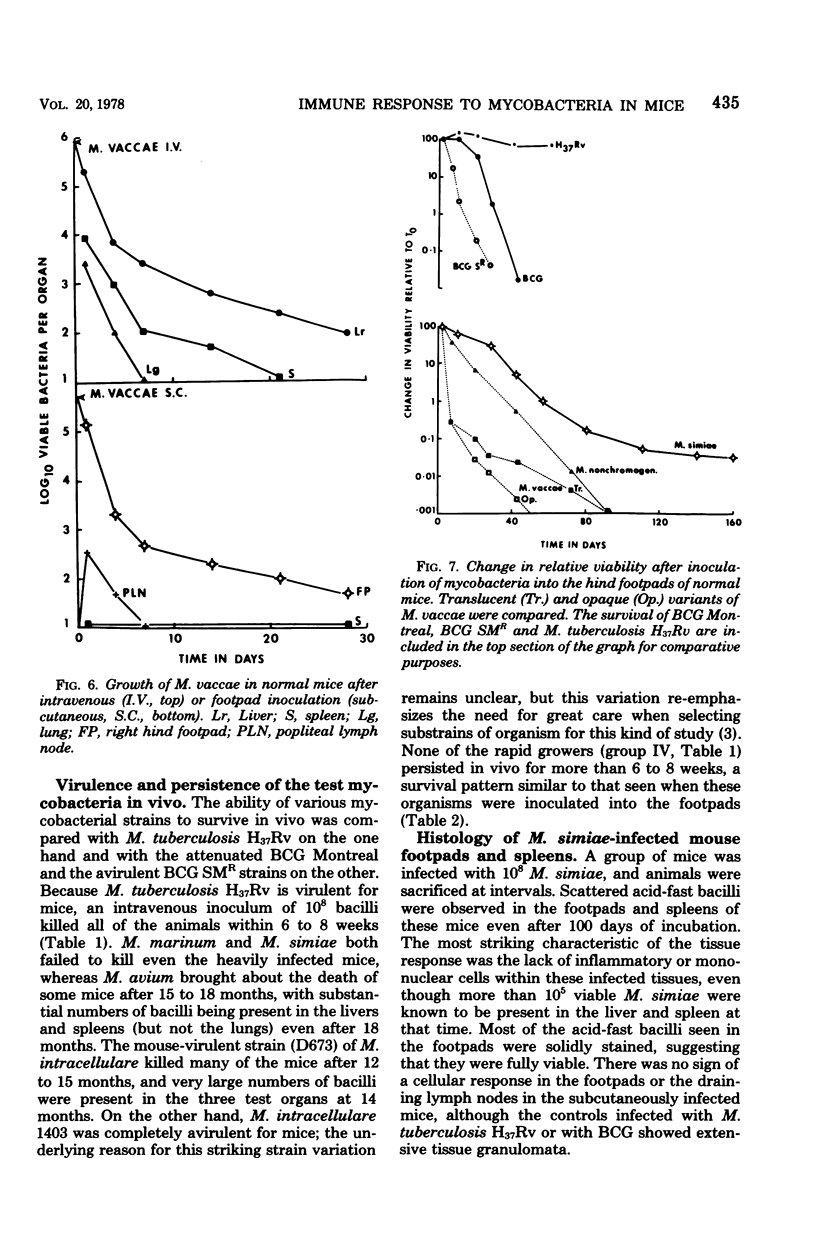

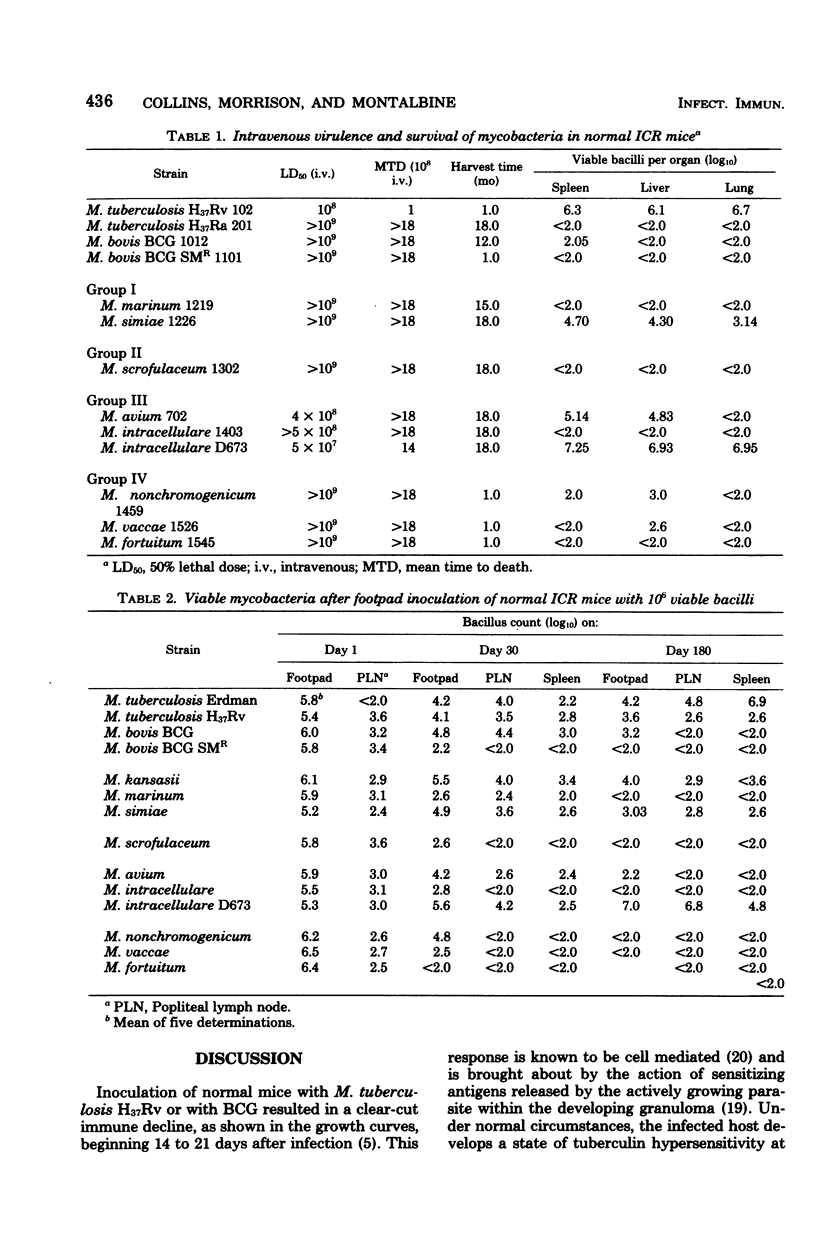

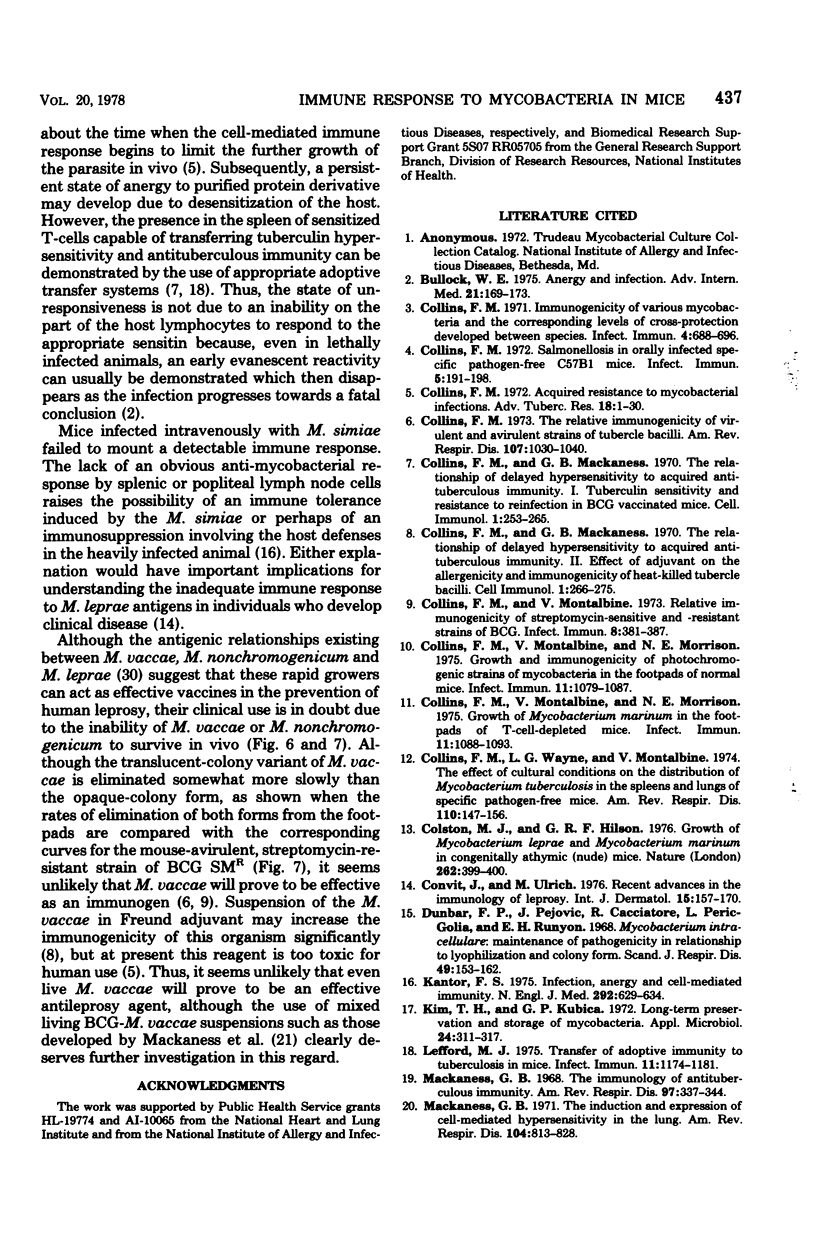

Mycobacterium marinum has been recommended as a possible model of M. leprae for use in laboratory studies of antileprosy immunity. M. marinum introduced into the footpads of normal mice underwent a steady decline in viability, with less than 1% survival after a 30-day period. Small numbers of viable bacilli were recovered from the footpads of these mice up to 12 months later. Similarly, mice infected with M. simiae exhibited bacterial populations that persisted for up to 18 months with little change in viability. Injection of M. simiae into the footpads was followed by an extensive redistribution of the organisms in the tissues. Eventally, bacterial counts for footpads and draining lymph nodes stabilized, with small numbers of bacilli still present in the footpads 18 months later. Persistent growth, with little sign of any immune response, was also observed in mice infected with several strains of M. avium, as well as with one strain of M. intracellulare. Other strains of M. intracellulare, as well as M. vaccae and M. nonchromogenicum, failed to establish persistent infections in normal mice, regardless of whether they were introduced by an intravenous or subcutaneous (footpad) route. The relevance of these findings is discussed in relation to antileprosy immunity in experimental animals and in humans.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Bullock W. E. Anergy and infection. Adv Intern Med. 1976;21:149–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M. Immunogenicity of various mycobacteria and the corresponding levels of cross-protection developed between species. Infect Immun. 1971 Dec;4(6):688–696. doi: 10.1128/iai.4.6.688-696.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Mackaness G. B. The relationship of delayed hypersensitivity to acquired antituberculous immunity. I. Tuberculin sensitivity and resistance to reinfection in BCG-vaccinated mice. Cell Immunol. 1970 Sep;1(3):253–265. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(70)90047-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Mackaness G. B. The relationship of delayed hypersensitivity to acquired antituberculous immunity. II. Effect of adjuvant on the allergenicity and immunogenicity of heat-killed tubercle bacilli. Cell Immunol. 1970 Sep;1(3):266–275. doi: 10.1016/0008-8749(70)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Montalbine V., Morrison N. E. Growth and immunogenicity of photochromogenic strains of mycobacteria in the footpads of normal mice. Infect Immun. 1975 May;11(5):1079–1087. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.5.1079-1087.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Montalbine V., Morrison N. E. Growth of Mycobacterium marinum in the footpads of T-cell-depleted mice. Infect Immun. 1975 May;11(5):1088–1093. doi: 10.1109/tmag.1975.1058958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Montalbine V. Relative immunogenicity of streptomycin-sensitive and -resistant strains of BCG. Infect Immun. 1973 Sep;8(3):381–387. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.3.381-387.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M. Salmonellosis in orally infected specific pathogen-free C57B1 mice. Infect Immun. 1972 Feb;5(2):191–198. doi: 10.1128/iai.5.2.191-198.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M. The relative immunogenicity of virulent and attenuated strains of tubercle bacilli. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1973 Jun;107(6):1030–1040. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1973.107.6.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins F. M., Wayne L. G., v Montalbine The effect of cultural conditions on the distribution of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the spleens and lungs of specific pathogen-free mice. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1974 Aug;110(2):147–156. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1974.110.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colston M. J., Hilson G. R. Growth of Mycobacterium leprae and M. marinum in congenitally athymic (nude) mice. Nature. 1976 Jul 29;262(5567):399–401. doi: 10.1038/262399a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Convit J., Ulrich M. Recent advances in the immunology of leprosy. Int J Dermatol. 1976 Apr;15(3):157–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-4362.1976.tb00679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunbar F. P., Pejovic I., Cacciatore R., Peric-Golia L., Runyon E. H. Mycobacterium intracellulare. Maintenance of pathogenicity in relationship to lyophilization and colony form. Scand J Respir Dis. 1968;49(2):153–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kantor F. S. Infection, anergy and cell-mediated immunity. N Engl J Med. 1975 Mar 20;292(12):629–634. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197503202921210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim T. H., Kubica G. P. Long-term preservation and storage of mycobacteria. Appl Microbiol. 1972 Sep;24(3):311–317. doi: 10.1128/am.24.3.311-317.1972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefford M. J. Transfer of adoptive immunity to tuberculosis in mice. Infect Immun. 1975 Jun;11(6):1174–1181. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.6.1174-1181.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackaness G. B. The J. Burns Amberson LECTURE The induction and expression of cell-mediated hypersensitivity in the lung. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1971 Dec;104(6):813–828. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1971.104.6.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackaness G. B. The immunology of antituberculous immunity. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1968 Mar;97(3):337–344. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1968.97.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meissner G., Schröder K. H. Relationship between Mycobacterium simiae and Mycobacterium habana. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1975 Feb;111(2):196–200. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1975.111.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng H., Jacobsen P. L., Levy L. Analogy of Mycobacterium marinum disease to Mycobacterium leprae infection in footpads of mice. Infect Immun. 1973 Dec;8(6):860–867. doi: 10.1128/iai.8.6.860-867.1973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paul R. C., Stanford J. L., Carswell J. W. Multiple skin testing in leprosy. J Hyg (Lond) 1975 Aug;75(1):57–68. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400047069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees R. J. Enhanced susceptibility of thymectomized and irradiated mice to infection with Mycobacterium leprae. Nature. 1966 Aug 6;211(5049):657–658. doi: 10.1038/211657a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees R. J. New prospects for the study of leprosy in the laboratory. Bull World Health Organ. 1969;40(5):785–800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rees R. J., Weddell A. G., Palmer E., Pearson J. M. Human leprosy in normal mice. Br Med J. 1969 Jul 26;3(5664):216–217. doi: 10.1136/bmj.3.5664.216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shepard C. C., Habas J. A. Relation of infection to tissue temperature in mice infected with Mycobacterium marinum and Mycobacterium leprae. J Bacteriol. 1967 Mar;93(3):790–796. doi: 10.1128/jb.93.3.790-796.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanford J. L. Editorial: A vaccine for leprosy. Lepr Rev. 1976 Jun;47(2):87–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]