Abstract

Background

To date, few studies have been conducted evaluating predictors of treatment seeking for substance use disorders as persons make the transition from preadolescence (a period of very low substance use) to young adulthood (a period of peak substance use). The few studies of this area which have been conducted to date have generally been limited by their use of a cross-sectional rather than a longitudinal study design. We have conducted a longitudinal etiology study (CEDAR) to assess whether an index of behavioral undercontrol called the Transmissible Liability Index (TLI) measured during preadolescence serves as a predictor of the development of substance use disorders (SUD) and of treatment utilization during young adulthood. Our recent work has focuses on subjects with cannabis use disorders (CUD), since CUD are the most common SUD. In recent analyses, we found that TLI serves as a predictor of the development of cannabis use disorder (CUD) among young adults (Kirisci et al., 2009).

Objective

In the current study, we hypothesized that TLI as assessed during preadolescence would predict treatment seeking a decade later when the subjects were young adults.

Method

The 375 participants in this study were initially recruited when they were 10–12 years of age. TLI status was determined at baseline, and subsequent assessments were conducted at 12–14, 16, 19, and 22 years of age. Variables examined included TLI as well as demographic variables. Path analyses were conducted.

Results

Of the 375 subjects recruited at age 10–12, 92 subjects (24.5%) were diagnosed with a CUD by the age of 22. TLI as assessed during pre-adolescence (at age 10 to 12) was found to be associated with substance-related treatment during young adulthood (age 19 and at age 22).

Conclusions

These findings confirmed our hypothesis that TLI assessed during preadolescent years serves as a predictor of treatment at age 19 and at age 22.

1. Introduction

Substance use disorders are uncommon in preadolescent years, but rise to their peak levels in late adolescence and young adulthood. A variety of factors have been reported to be linked to the development of substance use disorders (SUD) and associated phenomena such as treatment utilization for SUD. For example, a recent review by Zucker and colleagues (2011) listed several factors that have been reported to be associated with the development of SUD, such as antisocial comorbidity in a parent, involvement with deviant peers, poor parenting, exposure to abuse or conflict, low social competence in early childhood, or early use of substances. The conclusions of that review are consistent with our own findings concerning factors associated with the development of SUD (Clark, Cornelius, & Vanyukov, 2002; Clark, Cornelius, Wood, et al., 2004; Clark, Cornelius, Kirisci, et al, 2005; Cornelius, Clark, Reynolds, et al., 2007). However, little research had focused on predictors of treatment of substance use disorders during the transition from preadolescent years to the young adult years (McRae et al, 2003; Nordstrom et al, 2007; Cornelius et al., 2007). The few studies of this area which have been conducted to date have generally been limited by their use of a cross-sectional rather than longitudinal study design.

Our own research group has been conducting a large longitudinal study of the development of substance use disorders (SUD) and related phenomena (such as treatment for SUD) among subjects as they make the transition from preadolescence to adulthood. This study has focused on the role of transmissible liability for substance use disorders, as measured by a construct called the Transmissible Liability Index (TLI)(Kirisci et al, 2009), which serves as a continuous measure of behavioral undercontrol (Ridenour et al, In Press). Our previous results have demonstrated that TLI assessed during pre-adolescent years serves a significant predictor of cannabis use disorder among young adults (Kirisci et al., 2009). However, it is unclear whether TLI assessed during preadolescent years also serves as a predictor of treatment seeking for substance use disorders during young adulthood. That information could facilitate identification of individuals who would ultimately be in need of treatment for their substance use disorder, and thus could facilitate targeted early interventions.

In this longitudinal study, we evaluated the relationship between the TLI and treatment seeking for SUD treatment among subjects transitioning from preadolescence to young adulthood, after controlling for other relevant factors such as demographic variables (Cornelius, Clark, et al., 2007; Kirisci et al., 2009; Cornelius et al, 1995; Cornelius et al, 1996). Specifically, we evaluated associations between liability for SUD, as measured by TLI, and treatment seeking at age 19 and at age 22. We also tested mediating and moderating effects for treatment seeking.

2. Material and methods

2.a. Data collection and procedures

The subjects in this study were part of a longitudinal research study examining the etiology of SUD in families, known as the Center for Education and Drug Abuse Research, or CEDAR. The children were recruited through their biological fathers and initially assessed in late childhood at ages 10 through 12 years of age. The recruitment procedure was designed to yield a group of children at high average risk for SUD, identified by having fathers with a lifetime history of drug use disorders (abuse or dependence involving illicit substances) and a comparison group at low average risk, identified by having fathers without SUD or other major mental disorders. Fathers were the focus of recruitment rather than mothers because of the higher rate of SUD among the fathers. Also, the TLI has been shown to have 80% heritability when it was focused on the fathers, and in a family study predicted SUD outcome by age 19 with 68% accuracy (Kirisci et al, 2009). Fathers were considered to have a SUD if they ever met DSM criteria for abuse or dependence involving substances other than nicotine, caffeine, or alcohol. Diagnoses were made according to DSM-III-R, the most recent DSM edition when the study was initiated.

Multiple recruitment sources were used to minimize bias that could potentially occur if all of the subjects were recruited from one source. Approximately 89% of the families were recruited from the community through public service announcements and advertisements a well as by direct telephone contact conducted by a market research firm, and 11% were recruited from clinical sources (Cornelius et al, 2007; Cornelius et al., 2008). Psychosis, mental retardation, and neurological injury were exclusionary criteria for participation of the family. Prior to participation in the study, written informed consent was obtained from husbands and wives, and assent was obtained from offspring. The offspring were the focus of the current study. The study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. The subjects were recruited at age 10–12, and follow-up evaluations were conducted at ages 12–14, 16, 19, and 22, which covered the peak years for initiation of CUD and other SUD.

2.b. Participants

A total of 375 subjects were included in this ongoing study, including 92 subjects who met diagnostic criteria for a CUD and 283 of whom did not. The number of subjects with a CUD increased from 0% at the age 10–12 assessment to 5% (n=19) at the age 16 assessment, 16% (n=59) at the age 19 assessment, and 24.5% (n=92) at the age 22 assessment. The 92 subjects with a CUD at age 22 included 74 males (80.4%) and 18 females (19.6%), of whom 56 (60.9%) were Caucasian and 36 (39.1%) were African American.

2.c. Measures

Diagnostic evaluation was conducted with an expanded version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID)(Spitzer et al., 1987), which was the most recent DSM edition when the study was initiated. Offspring psychopathology was assessed with the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children-Epidemiologic Version (K-SADS-E) (Orvaschel et al., 1982). The onset date of each diagnosis was determined to the nearest month. Each family member was individually administered the research protocol in a private room by a different clinical associate. The diagnostic interviews were documented by a staff of experienced clinical associates. Training the clinical associates involved observation of several interviews and conducting joint interviews in the presence of an experienced interviewer. The training procedures were found to produce inter-rater reliabilities exceeding 0.80 for all major diagnostic categories. Diagnoses were determined in a consensus conference using the best estimate diagnostic procedure (Kosten & Rounsaville, 1992). The diagnostic data, in conjunction with all available pertinent medical records and social and legal history, were reviewed in a clinical case conference chaired by a board-certified psychiatrist and another psychiatrist or psychologist and the clinical associates who conducted the interviews. Treatment for SUD was assessed on the Treatment History Questionnaire (Cornelius et al,, 2001; Clark, Pollock, Mezzich, et al, 2001). That observer-rated instrument provides the frequency and timing of treatment episodes for substance use disorders in substance treatment facilities, as described by the participants. Additional information concerning the assessments and the validity of those assessment instruments has been provided elsewhere (Vanyukov et al. 1996; Clark et al., 2001; Cornelius, Kirisci, et al., 2010).

2.d. Study hypotheses

We hypothesized that TLI, as assessed at age 10 to 12, would be associated with treatment seeking for substance use disorders among persons with a cannabis use disorder at age 19 and at age 22.

2.e. Plan of Analyses

Based on the concept of common transmissible liability to SUD, the transmissible liability index has been developed at the Center for Education and Drug Abuse Research (CEDAR) and has been utilized in this project. The TLI is a method enabling quantification of this latent trait utilizing high risk design for a SUD and item response theory. The rationale and method of deriving the TLI have been described in prior reports (Vanyukov et al., 2003a, b; Vanyukov et al., 2009; Kirisci et al., 2009; Ridenour et al., In Press). The construction of the Transmissible Liability Index (TLI) was a multi-stage process. First, items were selected from psychological and psychiatric questionnaires and aggregated into conceptual domains. Emphasis in item selection focused on characteristics indicating deficient psychological self-regulation spanning cognitive, emotion, and behavior domains of measurement. After the selection of the initial pool of items was completed, exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis conducted. Constructs reflecting the measurement domains that distinguished offspring of father with and without substance use disorders (indicating transmissible SUD liability) were retained. Next, the constructs were submitted to confirmatory factor analysis to ensure unidimensionality of the index. Lastly, item response theory (IRT) analysis was performed to calibrate the items (determine item discrimination and threshold parameters). The TLI derived in this fashion thus contained the fewest and most robust items, accounting for 26% of item variance and having internal reliability of 0.87 (Kirisci et al., 2009). In the current analyses, a path analysis was conducted to test associations and to assess mediation effects associated with TLI, after allowing for factors such as demographic variables and socioeconomic status (SES) Dohrenwend et al., 1992). Mediated paths were tested using the method described by Sobel (1982), as updated by Mackinnon (2008). Path analyses using that method have been found to be a productive method of assessing mediated paths in our previous work involving adolescent substance use disorders (Kirisci et al., 2004; Kirisci et al., 2009).

3. Results

A total of 375 subjects were included in this ongoing study, including 92 subjects who met diagnostic criteria for a CUD and 283 of whom did not. The number of subjects with a CUD increased from 0% at the age 10–12 assessment to 5% (n=19) at the age 16 assessment, 16% (n=59) at the age 19 assessment, and 24.5% (n=92) at the age 22 assessment. The 92 subjects with a CUD included 74 males (80.4%) and 18 females (19.6%), of whom 56 (60.9%) were Caucasian and 36 (39.1%) were African American. Fourteen subjects had received substance related treatment by age 22. In addition to outpatient therapy, ten of those subjects (10.9%) had also participated in detoxification, 5 (5.4%) had participated in rehabilitation, and five (5.4%) reported medication treatment for emotional problems.

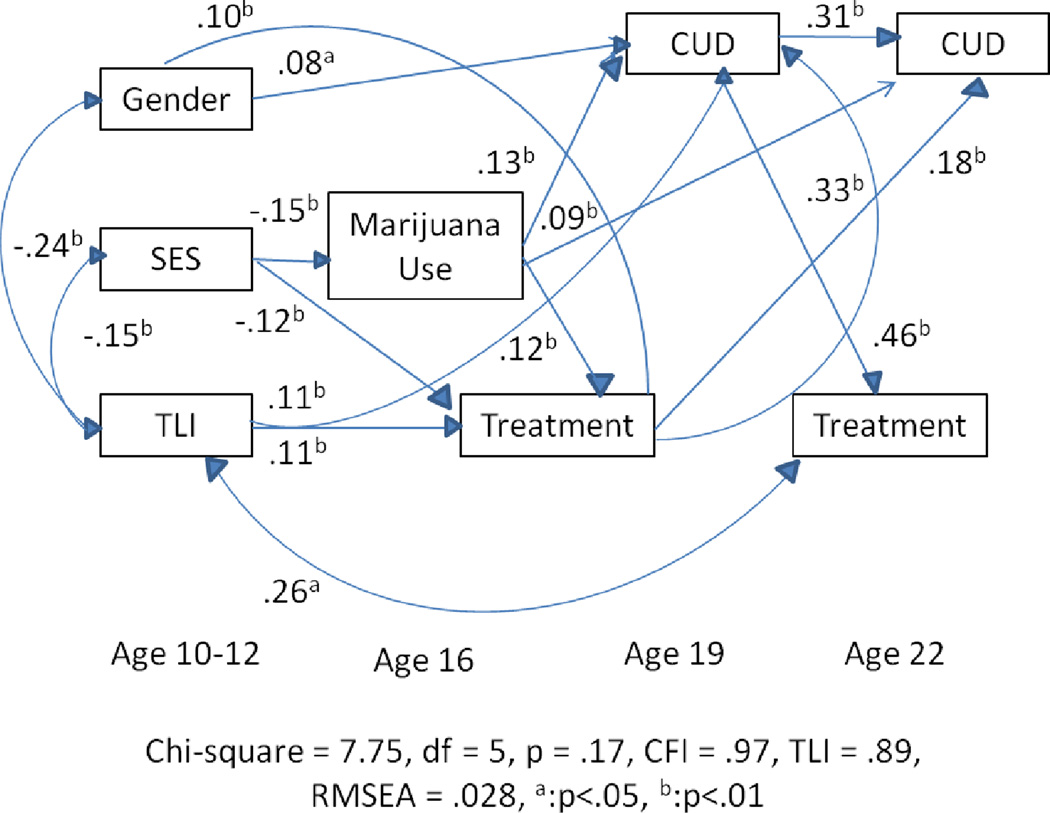

Path analysis (Fig. 1) demonstrated the following correlational findings:

Higher TLI was associated with a higher likelihood of receiving treatment (b=0.26, z=2.07, p=−.039) at age 22, (b=0.11, z=2.71, p=0.007) at age 19, and a higher likelihood of CUD (b=0.11, z=2.32, p=0.020) at age 19.

Female gender was associated with a higher likelihood of receiving treatment at age 19 (b=.10, z=3.46, p<0.001), and with a higher likelihood of having a CUD (b=0.08, z=2.30, p=0.022) at age 19.

Lower socioeconomic status (SES) (Dohrenwend et al, 1992) was associated with more marijuana use (b=−.15, z=−3.91, p<0.001) and with a higher likelihood of receiving treatment (b=−.12, z=−3.30, p=0.001) at age 19.

Higher TLI was correlated with lower SES (b=−.15, z=−3.97, p<0.001) and male gender (b=.24, z=−6.44, p<0.001).

Higher use of marijuana was associated with a higher likelihood of CUD (b=0.13, z=2.87, p=0.004) at age 19 and (b=0.09, z=2.83, p=0.005) at age 22, and was associated with a higher likelihood of getting drug related treatment (b=0.12, z=3.49, p<0.001) at age 19.

Subjects with CUD at age 19 were more likely to receive treatment (b=0.46, z=6.27, p<0.001) at age 22, and were more likely to be diagnosed with CUD (b=0.31, z=4.28, p<0.001) at age 22.

Subjects who received drug related treatment at age 19 were more likely to be diagnosed with CUD at age 22 (b=0.18, z=4.33, p<0.001).

Subjects who were diagnosed with CUD at age 19 were associated with receiving treatment at age 19 (b=0.33, z=3.24, p<.001).

Fig. 1. Path Analysis.

Variables: (1) Gender: 1 = male, 2 = female; (2) SES: Socioeconomic status; (3) TLI: transmissable liability index; (4) Treatment: treated drug problems (1 = yes, 0 = no); (5) CUD: cannabis use disorder diagnosis (1 = yes, 0 = no).

Four statistically significant mediators were also noted:

Substance related treatment at age 19 mediated between TLI and CUD at age 19 (b=0.02, z=2.20, p=0.028).

Substance related treatment at age 19 mediated between marijuana use and CUD at age 22 (b=0.02, z=2.64, p=0.008)

Marijuana use mediated between SES and substance related treatment at age 19 (b=−.02, z=−2.62, p=0.009).

CUD at age 19 mediated between marijuana use and substance related treatment at age 19 (b=.06, z=3.37, p=0.001).

4. Discussion

The findings of this longitudinal study confirmed our hypothesis that the index of behavioral undercontrol called the Transmissible Liability Index (TLI), as assessed at age 10 to 12, was associated with treatment seeking among persons with a cannabis use disorder at age 19 and also at age 22. In other words, characteristics noted at age 10 to 12, as assessed by TLI, were shown to be associated with treatment seeking about a decade later as the youth were entering young adulthood. Thus, treatment seeking ten years later was predicted by characteristics noted long before the development of the substance use disorder being studied.

In our current study, it was also noted that female gender and lower SES were associated with a higher likelihood of receiving treatment for substance related problems in our youthful population. Also, the majority of subjects with a CUD in our study did not receive treatment for their substance use problems. Further studies are warranted to clarify the effects of demographic factors and other factors on treatment use patterns among young persons with CUD and other SUD.

There are limitations to our research design that should be noted when interpreting our findings. First, the sample was not a random sample from across the United States, so the results may not generalize to the United States as a whole. Also, the study sample was primarily male, so the results of the study may not generalize to women. However, this study had the methodological advantage of being a longitudinal study, while most studies of SUD have been cross-sectional studies or brief longitudinal studies. Future studies are warranted to clarify the etiology, the optimal treatment modalities, and the optimal treatment utilization patterns for adolescents and young adults with CUD and other SUD (Vanyukov, Tarter, Kirisci, et al, 2003; Dennis et al, 2004). For example, future etiology studies are warranted to longitudinally study the separate behaviors assessed in the TLI. The results of those future etiology studies and treatment outcome studies will have important implications for health professionals, clinicians, and treatment consumers. Furthermore, in the current era of health care reform in the United States, studies are warranted to translate research findings among adolescents and young adults into public policy, in order to maximize the effectiveness of treatment provided for SUD (Cornelius & Clark, 2007).

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (P50 DA05605, R01 DA019142, R01 DA14635, K02 DA017822, and the NIDA Clinical Trials Network); from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (R01 AA013370, R01 AA015173, R01 AA14357, R01 AA13397, K24 AA15320, K05 DA031248 and K02 AA000291).

References

- Agosti V, Nunes E, Levin F. Rates of psychiatric comorbidity among U.S. residents with lifetime cannabis dependence. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:643–652. doi: 10.1081/ada-120015873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony JC, Warner LA, Kessler RC. Comparative epidemiology of dependence on tobacco, alcohol, controlled substances, and inhalants: Basic findings from the National Comorbidity Survey. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 1994;2:244–268. [Google Scholar]

- Budney AJ, Roffman R, Stephens RS, Walker D. Marijuana dependence and its treatment. Addiction Science & Clinical Practice, December. 2007;4(1):4–16. doi: 10.1151/ascp07414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Posttraumatic stress disorder and drug disorders: Testing causal pathways. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:1435–1442. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Cornelius MS, Kirisci L, Tarter RE. Childhood risk categories for adolescent substance involvement: a general liability typology. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Cornelius J, Vanyukov M. Childhood antisocial behavior and adolescent alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Research & Health. 2002;26:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Cornelius JR, Wood DS, Vanyukov ME. Psychopathology risk transmission in children of parents with substance use disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:685–691. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.4.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark DB, Pollock NK, Mezzich A, Cornelius J, Martin C. Diachronic assessment and the emergence of substance use disorders. Journal of Child and Adolescent Substance Abuse. 2001;10:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Grant BF, Colliver JD, Glantz MD. Prevalence of marijuana use disorders in the United States 1991–1992 and 2001–2002. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291(17):2114–2121. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.17.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compton WM, Pringle B. Services research on adolescent drug treatment. Commentary on the “The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: Main findings from two randomized trials”. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27(3):195–196. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Bukstein O, Salloum I, Clark D. In: Treatment of co-occurring alcohol, drug, and psychiatric disorders, Chapter 16, in volume XVII entitled Alcohol Problems in Adolescents and Young Adults, in the series of books entitled Recent Developments in Alcoholism. Marc Galanter., editor. Vol. 2005. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. pp. 349–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Clark DB. In: Translational research involving adolescent substance abuse,” Chapter 16, in Translation of Addictions Science into Practice: Update and Future Directions. Peter Miller, David Kavanagh., editors. New York, NY: Elsevier Press; 2007. pp. 341–360. [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Clark DB, Reynolds M, Kirisci L, Tarter R. Early age of first sexual intercourse and affiliation with deviant peers predict development of SUD: A prospective longitudinal study. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:850–854. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Fabrega H, Cornelius MD, Mezzich JE, Maher PJ, Salloum IM, Thase ME, Ulrich RF. Racial effects n the clinical presentation of alcoholics at a psychiatric hospital. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1996;37:102–108. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(96)90569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Jarrett PJ, Thase ME, Fabrega H, Haas GL, Jones-Barlock A, Mezzich JE, Ulrich RF. Gender effects on the clinical presentation of alcoholics at a psychiatric hospital. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 1995;36:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0010-440x(95)90251-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB, Hayes J, Tarter R. PTSD contributes to teen and young adult cannabis use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Kirisci L, Reynolds M, Clark DB, Hayes J, Tarter R. PTSD contributes to teen and young adult cannabis use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2010;35:91–94. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.09.007. American Journal of Psychiatry, 152:358–364, 1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Pringle J, Jernigan J, Kirisci L, Clark DB. Correlates of mental health service utilization and unmet need among a sample of male adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26:11–19. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00075-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornelius JR, Reynolds M, Martz BM, Clark DB, Kirisci L, Tarter R. Premature mortality among males with substance use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33:156–160. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Hall W, Lynskey M. Exploring the association between cannabis use and depression. Addiction. 2003;98:1493–1504. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00437.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M, Godley SH, Diamond G, Tims FM, Babor T, Donaldson J, Liddle H, Titus JC, Kaminer Y, Webb C, Hamilton N, Funk R. The Cannabis Youth Treatment (CYT) Study: main findings from two randomized trials. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2004;27:197–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dohrenwend B, Levav I, Shrout P, Schwartz S, Naveh G, Link B, Skodal A, Steuve A. Socioeconomic status and psychiatric disorder. the causation-selection issue. Science. 1992;225:946–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1546291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Hollon SD. What can specificity designs say about causality in psychopathology research? Psychological Bulletin. 1991;110:129–136. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.110.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Fielding B, Lahey BB, Dulcan M, Narrow W, Reiger D. Representativeness of clinical samples of youths with mental disorders: a preliminary population-based study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106(1):3–14. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. Second Edition. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Tarter R, Mezzich A, Ridenour T, Reynolds M, Vanyukov M. Prediction of cannabis use disorder between boyhood and young adulthood: clarifying the phenotype and environtype. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:36–47. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Vanyukov M, Reynolds M, Habeych M. Relation between cognitive distortions and neurobehavior disinhibition on the development of substance use during adolescence and substance use disorder by young adulthood: a prospective study. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;76:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirisci L, Tarter R, Mezzich A, Ridenour T, Reynolds M, Vanukov M. Prediction of cannabis use disorder between boyhood and young adulthood: Clarifying the phenotype and environtype. The American Journal on Addictions. 2009;18:36–47. doi: 10.1080/10550490802408829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosten TA, Rounsaville BJ. Sensitivity of psychiatric diagnosis based on the best estimate procedure. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:1225–1227. doi: 10.1176/ajp.149.9.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley MS. Treatment of adolescent depression: frequency of services and impact on functioning in young adulthood. Depression and Anxiety. 1998;7:47–52. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1520-6394(1998)7:1<47::aid-da6>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP. Introduction to Statistical Mediation Analysis. New York, NY: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Marijuana Treatment Project Research Group. Brief treatments for cannabis dependence: findings from a randomized multisite trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72:455–466. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McRae AL, Budney AJ, Brady KT. Treatment of marijuana dependence: a review of the literature. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2003;24:369–376. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(03)00041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom BR, Levin FR. Treatment of cannabis use disorders: a review of the literature. The American Journal on Addictions. 2007;16:331–342. doi: 10.1080/10550490701525665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orvaschel H, Puig-Antich J, Chambers WJ, Tabrizi MA, Johnson R. Retrospective assessment of prepubertal major depression with the Kiddie-SADS-E. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1982;21:392–397. doi: 10.1016/s0002-7138(09)60944-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour TA, Kirisci L, Tarter R, Vanyukov MM. Could a continuous measure of individual transmissible risk be useful in clinical assessment of substance use disorder ?: Findings from the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.018. (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobell MD. Asymptotic confidence intervals for indirect effects in structural equation models. In: Leinhardtp S, editor. Sociological Methodology. Washington, DDS: American Sociological Association; 1982. pp. 290–312. [Google Scholar]

- Spear LP. The adolescent brain and age-related behavioral manifestations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2000;24:417–463. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(00)00014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M. Instruction Manual for the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-III-R (SCID, 4/1/87 revision) New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner FA, Anthony JC. From first drug use to drug dependence: developmental periods of risk for dependence upon marijuana, cocaine, and alcohol. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2002;26:479–488. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00367-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Kirisci L, Moss L, Tarter RE, Reynolds MD, Maher BS, Kirillova GP, Ridenour T, Clark DB. Measurement of the risk for substance use disorders: Phenotypic and genetic analysis of an index of common liability. Behavior Genetics. 2009;39:233–244. doi: 10.1007/s10519-009-9269-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Kirisci L, Tarter RE, Simkevitz HF, Kirillova GP, Maher BS, Clark DB. Liability to substance use disorders 2. A measurement approach. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:517–526. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.003. 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Neale MC, Moss HB, Tarter RE. Mating assortment and the liability to substance abuse. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 1996;42:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0376-8716(96)01255-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanyukov MM, Tarter RE, Kirisci L, Kirillova GP, Maher BS, Clark DB. Liability to substance use disorders: common mechanisms and manifestations. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2003;27:507–515. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Volkow ND, Li TK. Drug addiction: the neurobiology of behaviour gone awry. Nature Reviews and Neuroscience. 2004;5:963–970. doi: 10.1038/nrn1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zucker RA, Heitzeg MM, Nigg JT. Parsing the undercontrol-disinhibition pathway to substance use disorders: A multilevel developmental problem. Child Development Perspectives. 2011;5(4):248–255. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2011.00172.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]