Highlights

-

•

Global gene expression analysis identifies glial specific transcriptomes.

-

•

Different glial subtypes have distinct but overlapping transcriptomes.

-

•

foxO and tramtrack69 are novel regulators of glial subtype specific proliferation.

Keywords: Glia, Drosophila, Cortex, Perineurial, foxO, Tramtrack

Abstract

Glial cells constitute a large proportion of the central nervous system (CNS) and are critical for the correct development and function of the adult CNS. Recent studies have shown that specific subtypes of glia are generated through the proliferation of differentiated glial cells in both the developing invertebrate and vertebrate nervous systems. However, the factors that regulate glial proliferation in specific glial subtypes are poorly understood. To address this we have performed global gene expression analysis of Drosophila post-embryonic CNS tissue enriched in glial cells, through glial specific overexpression of either the FGF or insulin receptor. Analysis of the differentially regulated genes in these tissues shows that the expression of known glial genes is significantly increased in both cases. Conversely, the expression of neuronal genes is significantly decreased. FGF and insulin signalling drive the expression of overlapping sets of genes in glial cells that then activate proliferation. We then used these data to identify novel transcription factors that are expressed in glia in the brain. We show that two of the transcription factors identified in the glial enriched gene expression profiles, foxO and tramtrack69, have novel roles in regulating the proliferation of cortex and perineurial glia. These studies provide new insight into the genes and molecular pathways that regulate the proliferation of specific glial subtypes in the Drosophila post-embryonic brain.

Glia play many critical roles in the development and maintenance of the nervous system. During development glia provide targets to ensure correct axonal pathfinding. In the mature nervous system glia provide trophic support by ensheathing neuronal cell bodies, processes and synapses. In the mammalian central nervous system (CNS) glia have also been shown to regulate synaptic transmission through modulation of neurotransmitter levels at ‘tripartite synapses’ (Perea et al., 2009). These functions are performed by different classes of glia, such as astrocytes that associate with neuronal cell bodies and synapses, and oligodendrocytes that form myelin sheaths around axons (Freeman and Doherty, 2006). The Drosophila CNS also contains several different essential glial classes, such as cortex glia that ensheath neuronal cell bodies and sub-perineurial/perineurial glia that form the blood brain barrier (Hartenstein, 2011).

Up to 50% of the cells in the human brain are glia (Azevedo et al., 2009). To provide sufficient glia for the mature CNS to function correctly, glial cells must be generated either from stem cell populations or through the proliferation of differentiated glia. In both the developing and adult mammalian CNS radial glia act as neural stem cells, which generate a variety of neuronal and glial subtypes (Rowitch and Kriegstein, 2010). Transcription factors (TFs) such as OLIG2, PAX6 and NKX6.1 control glial subtype differentiation from radial glial neural stem cells (Rowitch and Kriegstein, 2010).

In the Drosophila embryonic ventral nerve cord (VNC) glia are generated by asymmetric division of neuroglioblast stem cells (Ito et al., 1995). Glial cell fate in the embryonic VNC is regulated by the TF glial cells missing (gcm), which is necessary for and sufficient to induce gliogenesis (Hosoya et al, 1995, Jones et al, 1995). By contrast, in the Drosophila post-embryonic brain two major glial populations, cortex and perineurial glia, are generated by symmetric division of differentiated glial cells (Avet-Rochex et al, 2012, Awasaki et al, 2008, Colonques et al, 2007, Pereanu et al, 2005). Importantly, large scale genesis of glia through symmetric division of differentiated glial cells has also recently been observed in mammals, where differentiated astrocytes proliferate to generate large glial populations in the postnatal mouse brain (Ge et al., 2012). Therefore, gliogenesis through the proliferation of differentiated glia in the post-embryonic brain is conserved in flies and mammals. However, the genes that regulate the cell division of astrocytes are not known and the genetic regulation of proliferation of specific glial subtypes in Drosophila has only begun to be explored.

Two major questions arise from these studies of glial proliferation: (1) What are the factors that define glial subtype identity? (2) What are the factors and pathways that regulate the proliferation of specific glial subtypes? We have recently shown that proliferation of cortex and perineurial glia in the post-embryonic brain is driven by the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and insulin receptor (InR)/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathways, which differentially regulate cortex and perineurial glial proliferation (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012). However, the molecular mechanism by which these pathways regulate the proliferation of these specific glial subtypes is not known. To address these questions we have characterised global gene expression profiles from Drosophila postembryonic CNS tissue that is enriched for proliferating glial cells driven by either FGF or InR signalling. These two pathways have differential effects on specific glial subtypes, which are reflected in the respective gene expression profiles. To test the efficacy of these expression datasets we focused on TFs. We show that two of the TFs identified, kayak and hairy, are indeed expressed specifically in glia. Finally we show that another two of the TFs identified, foxO and tramtrack69, regulate the proliferation of specific glial subtypes.

1. Results and discussion

1.1. Global gene expression profiling of glia in the post-embryonic CNS

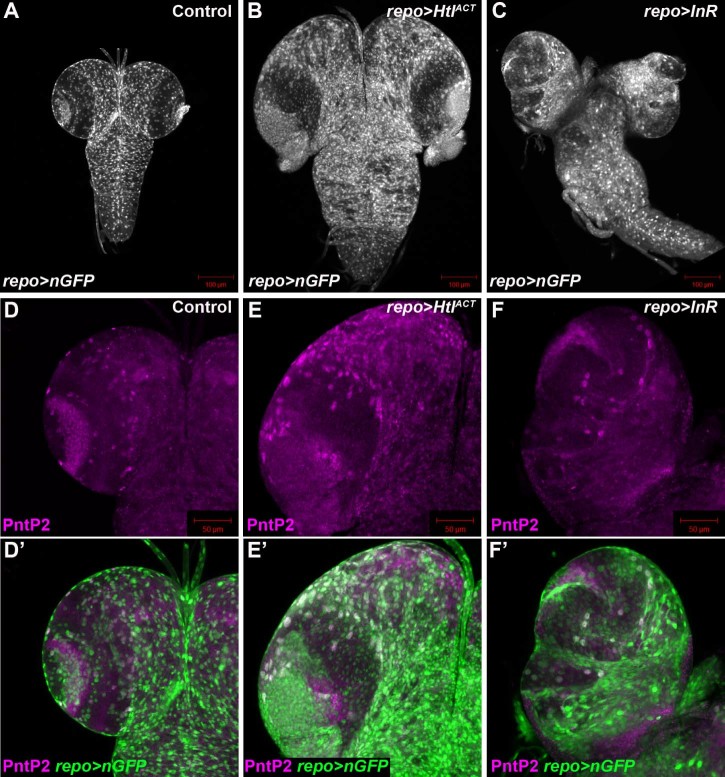

We have recently shown that the proliferation of two glial subtypes in the Drosophila post-embryonic brain is regulated through the concerted action of the FGF and InR/mTOR pathways. Cortex glia require FGF signalling and the InR, but not downstream components of the InR/mTOR pathway, whereas perineurial glia require both FGF and InR signalling pathways for proliferation. Pan-glial activation of either pathway causes glial overproliferation (Fig. 1B,C). However, specific glial sub-types respond differently to the expression of each receptor. The majority of superficial glia in larval brains from animals overexpressing an activated form of the FGF receptor (HtlACT) in glia expressed both the pan-glial protein Repo and pointedP2 (PntP2), a marker of cortex glia (Fig. 1E,E'). By contrast, glial-specific overexpression of the InR resulted in the proliferation of Repo expressing, but not PntP2 expressing glia (Fig. 1F,F'). These data suggest that these two receptors promote glial proliferation, but that the glial subtypes that proliferate are partially distinct.

Fig. 1.

Generation of larval CNS tissue enriched in glia. (A) Late third instar larval CNS expressing nuclear GFP in glia using repo-Gal4 (repo>nGFP). (B,C) Overexpression of HtlACT (B), or the InR (C) in glia using repo-Gal4 causes glial overproliferation. Glia are marked by the expression of nuclear GFP as in A. (D–F') Overexpression of HtlACT (E), but not the InR (F), in glia using repo-Gal4 causes overproliferation of PntP2 expressing cortex glia. PntP2 expression shown in magenta (D–F') and glia (green in D–E') are marked by the expression of nuclear GFP as in (A–C).

The glial overproliferation phenotype caused by overexpression of HtlACT and the InR (Fig. 1B,C) provided the opportunity to determine the global gene expression profile of glia in these tissues by comparing transcript levels from CNS tissue overexpressing either HtlACT, or the InR in glia, to that of control CNS tissue. We postulated that CNS tissue from larvae with increased glial numbers would be significantly enriched for the expression of glial genes, compared to CNS tissue from control larvae. Therefore, we dissected the CNS from third instar larvae overexpressing either HtlACT, or the InR in glia (using repo-Gal4), or from control larvae. RNA isolated from CNS tissue was then used for microarray gene expression analysis (see Experimental procedures).

1.2. Glial specific FGF and InR pathway activation results in different but overlapping glial enriched gene expression profiles

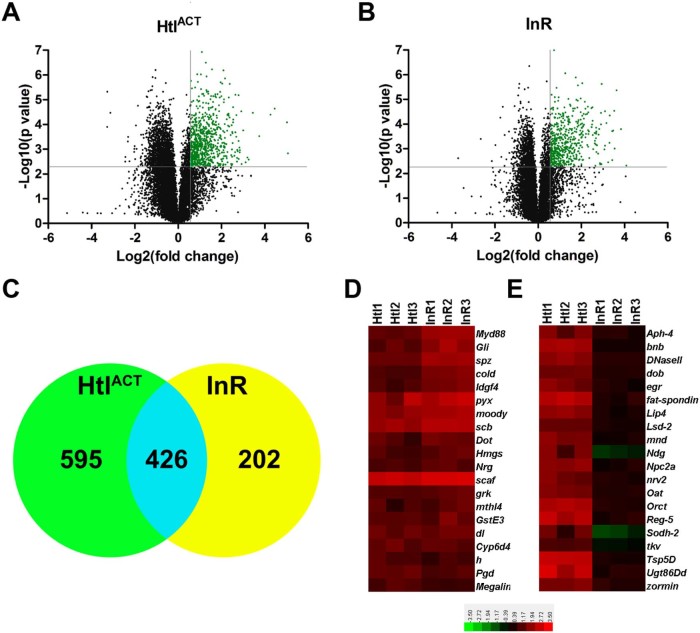

Analysis of transcript expression levels showed that the expression of 1021 genes was increased ≥1.5 fold and 583 genes increased ≥2 fold in HtlACT overexpressing CNS tissue (Fig. 2A, Supplementary Table S1). Expression of the glial-specific gene repo was increased 2.5 fold, while expression of pnt (the probe sequence was common to both pntP1 and pntP2 isoforms) was increased 4.96 fold (Supplementary Table S1). We previously showed that the number of Repo expressing superficial glia in HtlACT overexpressing brains was increased 2.27 fold, while the number of PntP2 expressing cortex glia was increased 3.65 fold (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012). Therefore, the changes in expression of repo and pnt correlate with the increase in glial numbers in HtlACT overexpressing tissue. Moreover, expression of other genes previously established to have roles in glial biology including bangles (bnb) (Ng et al., 1989), wrapper (Noordermeer et al., 1998), gliotactin (Gli) (Auld et al., 1995), kruppel (Kr) (Romani et al., 1996), sinuous (sinu), pickel (pck) (Stork et al., 2008), myoglianin (myo) (Lo and Frasch, 1999), held out wings (how) (Edenfeld et al., 2006), glial lazarillo (Glaz) (Sanchez et al., 2000), inebriated (ine) (Yager et al., 2001), neuroglian (Nrg) (Banerjee et al., 2006), Contactin (Cont) (Banerjee et al., 2006), moody, G protein α i subunit (G-ialpha65A, Gαi) and locomotion defects (loco) (Schwabe et al., 2005), were all significantly increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S1). GO analysis of cellular processes of genes with significantly increased expression in HtlACT tissue showed that the classes ‘establishment of the glial blood–brain barrier’ and ‘septate junction assembly’ were significantly over-represented (Supplementary Table S8). Taken together these data strongly suggest that this dataset is significantly enriched for glial-expressed genes. The GO analysis also showed that genes involved in small molecule, lipid and carbohydrate metabolism were significantly over-represented (Supplementary Table S8), suggesting that these proliferating glial cells are highly metabolically active.

Fig. 2.

Glial enriched larval CNS gene expression profiles. (A,B) Volcano plots of transcript expression levels from larval CNS tissue overexpressing HtlACT (A), or the InR (B) in glia using repo-Gal4. Transcripts whose expression increased ≥1.5 fold with a p value ≤0.05 are shown in green. (C) Venn diagram showing the numbers of genes whose expression was significantly increased ≥1.5 fold in either HtlACT overexpressing CNS tissue (green circle), InR overexpressing CNS tissue (yellow circle), or in both conditions (blue overlap). (D,E) Heat maps representing expression levels (log2) of 20 genes whose expression was similar (D), or significantly different (E) in HtlACT (Htl1-3) and InR (InR1-3) overexpressing CNS tissue.

In tissue overexpressing the InR in glia the expression of 628 genes were significantly increased ≥ 1.5 fold and 383 genes ≥ 2 fold (Fig. 2, Table S2). repo expression was significantly increased (1.68 fold), which correlates well with the 1.64-fold increase in Repo-expressing superficial glia in InR overexpressing brains (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012). The fact that there were fewer differentially upregulated genes in InR overexpressing tissue than in HtlACT overexpressing tissue may reflect the smaller increase in glial numbers in InR overexpressing tissue, compared to HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Fig. 1B,C) (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012). Of the 628 genes whose expression was increased in InR overexpressing tissue, 426 were also increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Fig. 2, Table S3). However, 32% (202) of genes with increased expression in InR overexpressing tissue were not significantly increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Fig. 2, Table S4), suggesting differences in the gene expression landscape, or glial subtypes, in these two tissues. As with HtlACT expressing tissue, expression of a number of genes with characterised functions in glial biology were significantly increased in InR overexpressing tissue including Gli, pck, sinu, moody, Cont and Nrg (Supplementary TableS2), all of which were also increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S1). As expected from the lack of increase in cortex glia in InR overexpressing tissue (Fig. 1F), expression of pnt was not significantly increased in InR overexpressing tissue. Similar to HtlACT overexpressing tissue, GO analysis showed that genes involved in the establishment of the blood brain barrier and septate junction assembly were over-represented in tissue overexpressing the InR (Supplementary Table S9). However, unlike HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S8), metabolic genes were not over-represented in InR overexpressing tissue. Furthermore, genes involved in the innate immune response were enriched in this tissue, but not in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S9). Thus, overexpression of the InR in glia results in a gene expression profile that overlaps with, but has significant differences to that of glia overexpressing HtlACT.

We hypothesised that neuronal specific genes would be over-represented in the group of genes whose expression was significantly decreased in tissue overexpressing HtlACT or the InR in glia. The expression of 1654 genes was significantly decreased ≥1.5 fold in CNS tissue overexpressing HtlACT in glia (Supplementary Table S5), while the expression of 240 genes were significantly decreased ≥1.5 fold in InR overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S6). Of the 240 genes whose expression was significantly decreased in InR overexpressing tissue 89% (213) were also decreased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S7). GO analysis of genes with significantly decreased expression in tissue overexpressing HtlACT in glia showed that cellular processes including ‘generation of neurons’, ‘neuron differentiation’, ‘neuron development’, ‘axonogenesis’, ‘axon guidance’, ‘neuroblast differentiation’ and ‘synaptic transmission’ were all over-represented (Supplementary Table S9). Very few GO classes were over-represented in the group of genes with significantly decreased expression from tissue overexpressing the InR in glia, but one of these was ‘neuropeptide signalling pathway’ (Supplementary Table S11). These bioinformatic analyses suggest that the group of genes with differentially decreased expression is strongly enriched for genes expressed in neurons in the larval CNS. However, this group may also include genes whose expression in glia is suppressed by overexpression of HtlACT or the InR.

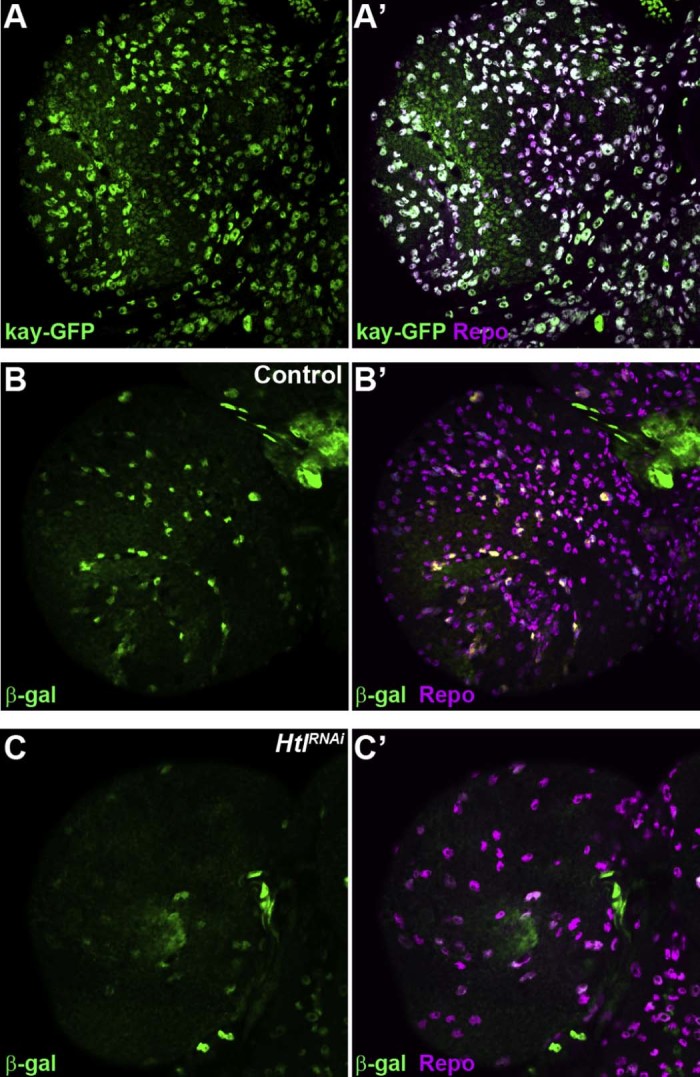

1.3. Expression analysis of TFs expressed in superficial glia in the post-embryonic brain

Although several of the genes whose expression was significantly increased in both HtlACT and InR overexpressing CNS tissue had been previously shown to function in glia, we sought to experimentally test the efficacy of the microarray datasets as a source of genes that are expressed in cortex glia and/or surface glia (perineurial and sub-perineurial glia) in the brain. We focused on TFs, as these frequently play important roles in gliogenesis. The expression of 21 TFs was significantly increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Table 1), while the expression of 10 TFs was significantly increased in InR overexpressing tissue (Table 2). Fifteen of the TFs whose expression was increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue were not increased in InR tissue (Table 1), while four (kni, kay, Usf and ci) were unique to InR overexpressing tissue (Table 2). We tested antibodies against several of the TFs identified (Dorsal, Krüppel, Knirps, cubitus interruptus, FoxO and Mef2), but these gave either weak staining or high background staining in the larval brain (data not shown). However, a GFP fusion of kayak showed expression in both cortex and surface glia in the larval brain (Fig. 3A). Also, a lacZ enhancer trap in hairy (hE11) showed clear β-galactosidase expression specifically in cortex glia (Fig. 3B). Moreover, inhibition of glial proliferation by knock-down of htl using repo-Gal4 caused a dramatic reduction in the number of hairy expressing glia (Fig. 3C). These results further validate the glial enriched gene expression datasets as a source of glial-expressed genes and also as a means of identifying genes whose expression is specific at least to cortex glia.

Table 1.

TFs with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlAct CNS tissue.

| Gene | Fold expression change | Characterised role in glia |

|---|---|---|

| pointed (pnt)* | 4.96 | Yes (Klambt, 1993) |

| Kruppel (Kr)* | 3.9 | Yes (Romani et al., 1996) |

| CG3328* | 3.65 | No |

| Pif1A | 2.9 | No |

| Hnf4* | 2.17 | No |

| dorsal (dl) | 2.72 | Yes (Kato et al., 2009) |

| CrebA* | 2.62 | No |

| Repo | 2.5 | Yes (Xiong et al., 1994) |

| Hairy (h)* | 2.23 | Yes (Giangrande, 1995) |

| tramtrack (ttk) | 2.1 | Yes, this study and (Badenhorst, 2001) |

| Xbp1* | 1.88 | Yes (Sone et al., 2013) |

| foxO* | 1.87 | Yes, this study and (Lavery et al., 2007) |

| Gemini (gem)* | 1.83 | No |

| Edl* | 1.83 | Yes (Yamada et al., 2003) |

| NFAT* | 1.83 | No |

| CG2678 | 1.71 | No |

| Mef2* | 1.66 | No |

| CG13188 | 1.63 | No |

| cup* | 1.55 | No |

| luna* | 1.54 | No |

| Eaf* | 1.52 | No |

Expression not significantly increased in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

Table 2.

TFs with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

| Gene | Fold expression change | Characterised role in glia |

|---|---|---|

| dorsal (dl) | 2.88 | Yes (Kato et al., 2009) |

| CG2678 | 2.48 | No |

| knirps (kni)* | 2.31 | No |

| kayak (kay)* | 2.01 | Yes (Macdonald et al., 2013) |

| Pif1A | 2.0 | No |

| Usf* | 1.9 | No |

| tramtrack (ttk) | 1.82 | Yes, this study and (Badenhorst, 2001) |

| CG13188 | 1.75 | No |

| repo | 1.68 | Yes (Xiong et al., 1994) |

| cubitus interruptus (ci)* | 1.54 | Yes (Rangarajan et al., 2001) |

Expression not significantly increased in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue.

Fig. 3.

kayak and hairy are expressed in glia in the brain. (A,A') Superficial layer of a late third instar larval brain expressing kayak-GFP (kay-GFP) stained for GFP (green) and Repo (magenta) expression. (B,B') β-Galactosidase expression (green) in the superficial layer of a control brain from a hE11 enhancer trap larva, co-stained for Repo expression (magenta). (C,C') β-Galactosidase expression (green) in the superficial layer of a repo-Gal4>htlRNAi third instar larval brain carrying the hE11 enhancer trap, co-stained for Repo expression (magenta).

1.4. foxO and tramtrack regulate glial proliferation in the Drosophila post-embryonic brain

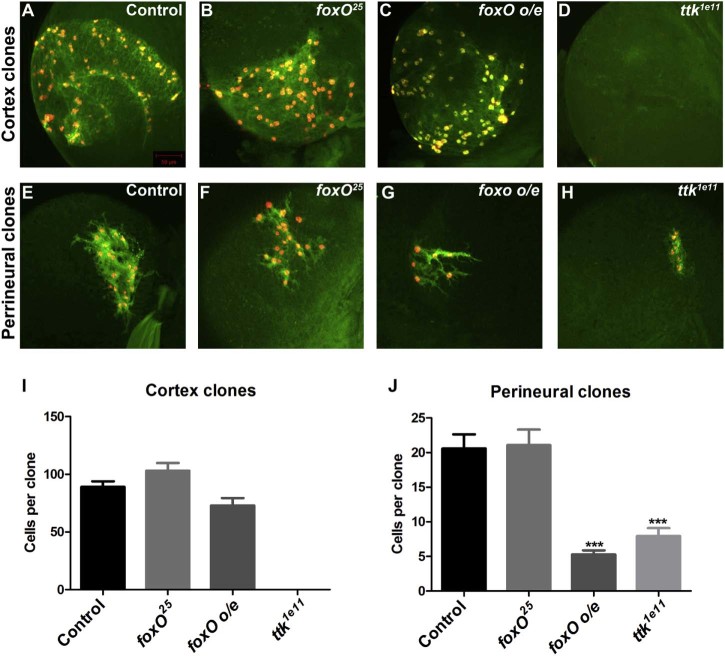

To test whether the glial enriched gene expression datasets could be used to identify genes involved in the regulation of glial proliferation in the post-embryonic brain we focused on two of the TFs identified in these datasets, foxO and tramtrack (ttk) (Table 1, Table 2). foxO and ttk have both been found previously to have roles in glial development in Drosophila, but their potential roles in glial proliferation in the post-embryonic brain are not known. FoxO is a negative regulator of growth, acting downstream of the InR and PI3K (Eijkelenboom and Burgering, 2013). FoxO has been shown to act in the InR pathway to regulate perineurial glial size in the peripheral nervous system (Lavery et al., 2007). ttk is a transcriptional repressor that acts to inhibit the expression of neuronal genes in embryonic glial development and to negatively regulate the proliferation of embryonic longitudinal glia (Badenhorst, 2001).

To test the requirement for foxO in cortex and perineurial glia we generated repo-MARCM clones homozygous for a loss-of-function (LOF) mutation in foxO (foxO25). Loss of foxO did not affect the size of either cortex or perineurial glial clones (Fig. 4B,F,I,J). FoxO regulates growth control downstream of the InR, but foxO mutants do not have a growth phenotype, whereas overexpression of foxO inhibits growth (Junger et al., 2003). We therefore overexpressed foxO using repo-MARCM and found that this did not affect cortex clones but caused a significant reduction in perineurial glial clone size (Fig. 4C,G,I,J). Therefore, foxO is sufficient to inhibit glial proliferation specifically in perineurial glia.

Fig. 4.

foxO and ttk69 regulate glial proliferation in the postembryonic brain. (A–D) Representative repo-MARCM cortex clones marked with GFP (green) and nuclear-RFP (red) expression. (E–H) Representative repo-MARCM perineurial clones marked with GFP (green) and nuclear-RFP (red) expression. (I) Quantification of cortex repo-MARCM clone sizes. Average clone size of FRT82B control clones (n = 10), foxO25 (n = 9), foxO overexpression (o/e) (n = 8) and ttk1e11 clones (no cortex clones were observed in >50 brains). (J) Quantification of perineurial repo-MARCM clone sizes. Average clone size of FRT82B control clones (n = 34), foxO25 (n = 49), foxO overexpression (o/e) (n = 24) and ttk1e11 clones (n = 24). Data are represented as mean +/− SEM. ***p < 0.001.

Ttk is a transcriptional repressor and its first characterised functional role was in cell fate determination in the Drosophila eye (Xiong and Montell, 1993). Drosophila has two Ttk isoforms, Ttk88 and Ttk69, which differ in their carboxyl-terminal DNA binding zinc finger domains (Harrison, Travers, 1990, Read, Manley, 1992). ttk88 is not required for glial development in the Drosophila embryo, whereas loss of ttk69 causes increased proliferation of longitudinal glia (Badenhorst, 2001). Surprisingly, LOF repo-MARCM analysis of ttk using ttk1e11, an allele specific to the Ttk69 isoform (Lai and Li, 1999), demonstrated that ttk69 is positively required in both cortex and perineurial glia. We did not observe a single cortex clone that was mutant for ttk69 and perineurial ttk69 clones were significantly smaller than control clones (Fig. 4D,H–J). Therefore, ttk69 is a key regulator of both cortex and perineurial glial proliferation in the Drosophila post-embryonic brain.

The proliferative potential of differentiated glia has recently been demonstrated in both the Drosophila and vertebrate CNS, but the genetic regulation of this process is poorly understood. We profiled the global gene expression pattern of CNS tissue enriched for different subsets of glial cells through activation of either FGF or InR signalling. Our data and analyses strongly suggest that these glial transcriptomes are highly enriched for overlapping but distinct sets of glial genes and can be used as a resource for identification of novel glial genes expressed in specific glial subtypes. Conversely, the set of genes whose expression is decreased provides a resource of neuronally expressed genes. As a proof-of-principle we then used these data to identify two genes that specifically regulate cortex and perineurial glial proliferation in the post-embryonic brain.

Three studies have previously attempted to identify glial genes by gene expression profiling, all in the Drosophila embryo (Altenhein et al, 2006, Egger et al, 2002, Freeman, Doherty, 2006). The first two studies induced gliogenesis by ectopic expression of gcm in the embryonic nervous system (Egger et al, 2002, Freeman et al, 2003). Freeman et al. (2003) found a high rate of false positives (88%) when the differentially regulated genes were analysed by in situ hybridisation and suggested a similar rate of false positives in the genes identified by Egger et al. (2002). In addition to microarray analysis Freeman et al. combined expression databases and computational analysis of gcm target genes to identify 45 new Drosophila glial genes (Freeman et al., 2003). With the goal of improving on these earlier studies Altenhein et al., in addition to ectopic gcm expression, used gcm mutant embryos to identify glial genes (Altenhein et al., 2006). Surprisingly, there was not a great deal of overlap between the differentially regulated genes identified in these three studies (Altenhein et al., 2006). Similarly, we found a relatively low degree of overlap between the genes identified in these previous studies and the genes with significantly increased expression from larval CNS tissue overexpressing HtlACT in glia. Twenty-one per cent (68 of 328) of the glial genes identified by Altenhein et al. (2006), 31% (14 of 45) of the glial genes identified by Freeman et al. (2003), and 9% (23 of 257) of the glial genes from the Egger et al. (2002), study were present in our HtlACT significantly increased gene set (Supplementary Table S1). To some extent this is not surprising as our study used the late third instar larval CNS and induced gliogenesis through overexpression of HtlACT, rather than overexpression or loss of gcm. The differences may also reflect the different gene expression patterns of glia generated through glial cell division and glia generated through ectopic differentiation from neuroglioblast precursors.

The first question we aimed to address using gene expression profiling was the identity of factors that define specific glial subtypes. Overexpression of HtlACT and the InR drives the proliferation of different but overlapping glial subtypes and this is reflected in the sets of genes whose expression was significantly increased in either tissue. Focusing on TFs we found that kayak is expressed in cortex and surface glia, while hairy expression is specific to cortex glia. Taken together our data extend our previous work demonstrating that cortex and surface glial have distinct gene expression signatures that define each glial subtype.

The second question we aimed to address was the identity of novel genes and pathways that regulate the proliferation of specific glial subtypes. TFs such as dorsal, foxO and ci, whose expression was significantly increased in HtlACT and InR overexpressing tissue (Table 1, Table 2), are known to regulate cell proliferation in other contexts and so are good candidates as regulators of glial proliferation. Mef2 had not been previously shown to have a role in glia, but was differentially upregulated in HtlACT (but not InR) overexpressing CNS tissue (Table 1). Mef2 has recently been shown to act synergistically with Notch to activate cell proliferation by inducing the expression of the matrix metalloproteinase Mmp1 and the TNF ligand eiger (egr) in Drosophila (Pallavi et al., 2012). Interestingly, the expression of both Mmp1 and egr are also increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S1). Mef2 has also been identified as a transcriptional target of dorsal in the embryonic mesoderm (Stathopoulos et al., 2002), suggesting a potential hierarchical relationship between dorsal and Mef2 in regulating glial proliferation in the larval CNS.

A second TF that had not been previously recognised to have a role in glia, but whose expression was significantly increased in InR overexpressing tissue (Table 2), is the gap gene knirps. knirps is required for embryonic segmentation and has also been shown to act downstream of Decapentaplegic (Dpp) signalling in the Drosophila tracheal system (Chen et al., 1998). Dpp signalling regulates glial proliferation in the Drosophila eye (Rangarajan et al., 2001) and Dpp expression is significantly increased in both HtlACT and InR overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Tables S1 and S2). Expression of the Dpp receptors thickvein (tkv) and glass bottom boat (gbb) are also significantly increased in HtlACT overexpressing tissue (Supplementary Table S1). Thus, knirps may act downstream of Dpp signalling to regulate the proliferation of cortex glia.

To test whether two of the TFs we identified were required for proliferation of either cortex or perineurial glia we used repo-MARCM LOF analysis. We found that foxO is not necessary for glial proliferation, but is sufficient to specifically inhibit the proliferation of perineurial glia. FoxO is a negative regulator of growth and upon activation of the InR pathway FoxO is phosphorylated by AKT, which causes FoxO to be sequestered in the cytoplasm (Junger et al., 2003). We previously proposed a model in which PI3K signalling acts together with the FGF pathway to regulate perineurial glial proliferation, whereas PI3K signalling is not required for cortex glia proliferation (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012). The inhibition of perineurial but not cortex glial proliferation by foxO overexpression fits well with this model and extends our previous findings, suggesting that FoxO acts as a negative regulator of perineurial glial proliferation downstream of InR/PI3K signalling specifically in perineurial glia.

We also found that ttk69 is positively required for the proliferation of both cortex and perineurial glia. Although ttk69 is a negative regulator of longitudinal glial proliferation in the Drosophila embryo (Badenhorst, 2001), ttk69 is positively required to promote photoreceptor development in the late pupal stage during Drosophila eye development (Lai and Li, 1999), thus a positive role for ttk69 is not unprecedented. ttk69 is absolutely required for cortex glial proliferation but only partially required in perineurial glia. This phenotype is very similar to the requirement for components of the FGF pathway in glial proliferation (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012). We therefore suggest that Ttk69 acts downstream of FGF signalling to regulate cortex and perineurial glial proliferation in the larval brain.

1.5. Conclusions

Future studies will fully dissect the roles of foxO and ttk in glial proliferation, but our data demonstrate that the glial transcriptomes we have characterised can be used to identify genes that have key roles in regulating subtype specific glial proliferation in the larval brain.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Drosophila stocks

Flies were maintained on standard yeast, glucose, agar food at 25 °C unless otherwise stated. hE11 was from David Ish-Horowicz and FRT82B,foxO25 from Helen McNeill. FRT82B, Kay-GFP, UAS-HtlACT, UAS-InR, UAS-foxO, FRT82B, ttk1e11, UAS-RedStinger and repo-Gal4 were from the Bloomington Stock Center. The repo-MARCM stock genotype was as described previously (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012), but using UAS-RedStinger instead of UAS-nLacZ to visualise nuclei: UAS-RedStinger; repo-flp, repo-Gal4, UAS-actinGFP; FRT82B, tub-Gal80. Knock-down of htl was performed as described previously (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012).

2.2. Immunofluorescence and imaging

Antibody staining was performed as previously described (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012). Antibodies were mouse anti-Repo (DSHB, 1/100), rat anti-PntP2 (Avet-Rochex et al., 2012; 1/500), chicken anti-β-galactosidase (Abcam, 1/1000), rabbit anti-GFP (Molecular Probes, 1/1000). Secondary antibodies were from Invitrogen. Imaging was performed on a Zeiss LSM 710 and images were processed in Adobe Photoshop.

repo-MARCM clone sizes were quantified manually in ImageJ by quantifying numbers of RFP positive nuclei per clone. Statistical analysis was performed in GraphPad Prism using one way ANOVA with Dunnett's post hoc test.

2.3. Microarray experiments and data analysis

For microarray analysis, the complete CNS from 10–15 wandering third instar larvae were dissected in PBS on ice and then transferred into 100 µl of cold lysis buffer from the Absolutely RNA Microprep kit (Stratagene) and vortexed for 5 s. Total RNA was then prepared using this kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. For each genotype RNA samples were prepared in triplicate and stored at −80 °C. cRNA was prepared from 500 ng of total RNA using the Ambion Premier kit (Ambion) and hybridisations were performed using the Genechip 3'IVT kit (Affymetrix) on Genechip Drosophila Genome 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix). Imaging of the arrays was performed using the Affymetrix GCS3000 microarray system.

Data normalisation was performed using the Microarray Suite version 5 (MAS 5.0) statistical algorithm using the Affymetrix Expression Console software. Probes where the detection p-value (calculated using the intensity value of a perfect match to a mismatch sequence) was >0.06 in any of the samples were classed as ‘absent’ (A) and excluded from further analysis. Using this criterion, 8638 and 8779 unique probes were included for control versus HtlACT tissue and control versus InR tissue respectively. Relative differences in gene expression were calculated using the array statistical programme Significance Analysis of Microarrays (SAM) (Tusher et al., 2001). SAM uses gene expression measurements and a response variable to determine if the expression of any genes is significantly related to the response. We used a two class unpaired response type, using log2 of the raw expression values, selecting genes whose expression had increased either ≥1.5 or decreased ≤1.5 fold with a false discovery rate of 0.58% (repo-Gal4>HtlACT) and 0.56% (repo-Gal4>InR).

Volcano plots were generated using GraphPad Prism 5. Heat maps were generated from log2 values of the expression change values using Cluster 3.0 (Eisen et al., 1998) and Java Treeview (Saldanha, 2004). The data discussed in this publication have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus (Edgar et al., 2002) and are accessible through GEO Series accession number GSE46317 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE46317).

2.4. Gene ontology (GO) analysis

GO enriched cellular processes in the differentially regulated gene sets were determined using the Generic GO Term Finder (Boyle et al., 2004). The complete gene list (excluding absent probes) from which the differentially regulated genes were identified was used as the background population.

Acknowledgements

The work was funded by King's College London and the Wellcome Trust (WT088460MA and WT089622MA).

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at doi:10.1016/j.gep.2014.09.001.

Appendix. Supplementary material

The following are the supplementary data to this article:

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in both repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue and repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue, but not repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly decreased expression ≤ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly decreased expression ≤ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue. 22

Genes with significantly decreased expression ≤ 1.5 fold in both repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT and repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly increased expression ≥1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly increased expression ≥1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly decreased expression ≤1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly decreased expression ≤1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.

References

- Altenhein B., Becker A., Busold C., Beckmann B., Hoheisel J.D., Technau G.M. Expression profiling of glial genes during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 2006;296:545–560. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.04.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auld V.J., Fetter R.D., Broadie K., Goodman C.S. Gliotactin, a novel transmembrane protein on peripheral glia, is required to form the blood-nerve barrier in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;81:757–767. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90537-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avet-Rochex A., Kaul A.K., Gatt A.P., McNeill H., Bateman J.M. Concerted control of gliogenesis by InR/TOR and FGF signalling in the Drosophila post-embryonic brain. Development. 2012;139:2763–2772. doi: 10.1242/dev.074179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awasaki T., Lai S.L., Ito K., Lee T. Organization and postembryonic development of glial cells in the adult central brain of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:13742–13753. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4844-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azevedo F.A., Carvalho L.R., Grinberg L.T., Farfel J.M., Ferretti R.E., Leite R.E. Equal numbers of neuronal and nonneuronal cells make the human brain an isometrically scaled-up primate brain. J. Comp. Neurol. 2009;513:532–541. doi: 10.1002/cne.21974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badenhorst P. Tramtrack controls glial number and identity in the Drosophila embryonic CNS. Development. 2001;128:4093–4101. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.4093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee S., Pillai A.M., Paik R., Li J., Bhat M.A. Axonal ensheathment and septate junction formation in the peripheral nervous system of Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:3319–3329. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5383-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle E.I., Weng S., Gollub J., Jin H., Botstein D., Cherry J.M. GO::termFinder–open source software for accessing Gene Ontology information and finding significantly enriched Gene Ontology terms associated with a list of genes. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3710–3715. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.K., Kuhnlein R.P., Eulenberg K.G., Vincent S., Affolter M., Schuh R. The transcription factors KNIRPS and KNIRPS RELATED control cell migration and branch morphogenesis during Drosophila tracheal development. Development. 1998;125:4959–4968. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colonques J., Ceron J., Tejedor F.J. Segregation of postembryonic neuronal and glial lineages inferred from a mosaic analysis of the Drosophila larval brain. Mech. Dev. 2007;124:327–340. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edenfeld G., Volohonsky G., Krukkert K., Naffin E., Lammel U., Grimm A. The splicing factor crooked neck associates with the RNA-binding protein HOW to control glial cell maturation in Drosophila. Neuron. 2006;52:969–980. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edgar R., Domrachev M., Lash A.E. Gene expression omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–210. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger B., Leemans R., Loop T., Kammermeier L., Fan Y., Radimerski T. Gliogenesis in drosophila: genome-wide analysis of downstream genes of glial cells missing in the embryonic nervous system. Development. 2002;129:3295–3309. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.14.3295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eijkelenboom A., Burgering B.M. FOXOs: signalling integrators for homeostasis maintenance. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;14:83–97. doi: 10.1038/nrm3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen M.B., Spellman P.T., Brown P.O., Botstein D. Cluster analysis and display of genome-wide expression patterns. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1998;95:14863–14868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.25.14863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M.R., Doherty J. Glial cell biology in Drosophila and vertebrates. Trends Neurosci. 2006;29:82–90. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M.R., Delrow J., Kim J., Johnson E., Doe C.Q. Unwrapping glial biology: Gcm target genes regulating glial development, diversification, and function. Neuron. 2003;38:567–580. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00289-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge W.P., Miyawaki A., Gage F.H., Jan Y.N., Jan L.Y. Local generation of glia is a major astrocyte source in postnatal cortex. Nature. 2012;484:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature10959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giangrande A. Proneural genes influence gliogenesis in Drosophila. Development. 1995;121:429–438. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.2.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison S.D., Travers A.A. The tramtrack gene encodes a Drosophila finger protein that interacts with the ftz transcriptional regulatory region and shows a novel embryonic expression pattern. EMBO J. 1990;9:207–216. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08097.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartenstein V. Morphological diversity and development of glia in Drosophila. Glia. 2011;59:1237–1252. doi: 10.1002/glia.21162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosoya T., Takizawa K., Nitta K., Hotta Y. Glial cells missing: a binary switch between neuronal and glial determination in Drosophila. Cell. 1995;82:1025–1036. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90281-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K., Urban J., Technau G.M. Distribution, classification, and development of Drosophila glial cells in the late embryonic and early larval ventral nerve cord. Rouxs Arch. Dev. Biol. 1995;204:284–307. doi: 10.1007/BF02179499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B.W., Fetter R.D., Tear G., Goodman C.S. glial cells missing: a genetic switch that controls glial versus neuronal fate. Cell. 1995;82:1013–1023. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90280-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junger M.A., Rintelen F., Stocker H., Wasserman J.D., Vegh M., Radimerski T. The Drosophila forkhead transcription factor FOXO mediates the reduction in cell number associated with reduced insulin signaling. J. Biol. 2003;2:20. doi: 10.1186/1475-4924-2-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato K., Awasaki T., Ito K. Neuronal programmed cell death induces glial cell division in the adult Drosophila brain. Development. 2009;136:51–59. doi: 10.1242/dev.023366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klambt C. The Drosophila gene pointed encodes two ETS-like proteins which are involved in the development of the midline glial cells. Development. 1993;117:163–176. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai Z.C., Li Y. Tramtrack69 is positively and autonomously required for Drosophila photoreceptor development. Genetics. 1999;152:299–305. doi: 10.1093/genetics/152.1.299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery W., Hall V., Yager J.C., Rottgers A., Wells M.C., Stern M. Phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase and Akt nonautonomously promote perineurial glial growth in Drosophila peripheral nerves. J. Neurosci. 2007;27:279–288. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3370-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo P.C., Frasch M. Sequence and expression of myoglianin, a novel Drosophila gene of the TGF-beta superfamily. Mech. Dev. 1999;86:171–175. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00108-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald J.M., Doherty J., Hackett R., Freeman M.R. The c-Jun kinase signaling cascade promotes glial engulfment activity through activation of draper and phagocytic function. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1140–1148. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ng S.C., Perkins L.A., Conboy G., Perrimon N., Fishman M.C. A Drosophila gene expressed in the embryonic CNS shares one conserved domain with the mammalian GAP-43. Development. 1989;105:629–638. doi: 10.1242/dev.105.3.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordermeer J.N., Kopczynski C.C., Fetter R.D., Bland K.S., Chen W.Y., Goodman C.S. Wrapper, a novel member of the Ig superfamily, is expressed by midline glia and is required for them to ensheath commissural axons in Drosophila. Neuron. 1998;21:991–1001. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80618-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pallavi S.K., Ho D.M., Hicks C., Miele L., Artavanis-Tsakonas S. Notch and Mef2 synergize to promote proliferation and metastasis through JNK signal activation in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2012;31:2895–2907. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2012.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perea G., Navarrete M., Araque A. Tripartite synapses: astrocytes process and control synaptic information. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:421–431. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereanu W., Shy D., Hartenstein V. Morphogenesis and proliferation of the larval brain glia in Drosophila. Dev. Biol. 2005;283:191–203. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangarajan R., Courvoisier H., Gaul U. Dpp and Hedgehog mediate neuron-glia interactions in Drosophila eye development by promoting the proliferation and motility of subretinal glia. Mech. Dev. 2001;108:93–103. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(01)00501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read D., Manley J.L. Alternatively spliced transcripts of the Drosophila tramtrack gene encode zinc finger proteins with distinct DNA binding specificities. EMBO J. 1992;11:1035–1044. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05142.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romani S., Jimenez F., Hoch M., Patel N.H., Taubert H., Jackle H. Kruppel, a Drosophila segmentation gene, participates in the specification of neurons and glial cells. Mech. Dev. 1996;60:95–107. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00603-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowitch D.H., Kriegstein A.R. Developmental genetics of vertebrate glial-cell specification. Nature. 2010;468:214–222. doi: 10.1038/nature09611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saldanha A.J. Java Treeview–extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:3246–3248. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D., Ganfornina M.D., Torres-Schumann S., Speese S.D., Lora J.M., Bastiani M.J. Characterization of two novel lipocalins expressed in the Drosophila embryonic nervous system. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2000;44:349–359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwabe T., Bainton R.J., Fetter R.D., Heberlein U., Gaul U. GPCR signaling is required for blood-brain barrier formation in drosophila. Cell. 2005;123:133–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sone M., Zeng X., Larese J., Ryoo H.D. A modified UPR stress sensing system reveals a novel tissue distribution of IRE1/XBP1 activity during normal Drosophila development. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2013;18:307–319. doi: 10.1007/s12192-012-0383-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stathopoulos A., Van Drenth M., Erives A., Markstein M., Levine M. Whole-genome analysis of dorsal-ventral patterning in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 2002;111:687–701. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01087-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stork T., Engelen D., Krudewig A., Silies M., Bainton R.J., Klambt C. Organization and function of the blood-brain barrier in Drosophila. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:587–597. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4367-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tusher V.G., Tibshirani R., Chu G. Significance analysis of microarrays applied to the ionizing radiation response. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:5116–5121. doi: 10.1073/pnas.091062498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W.C., Montell C. Tramtrack is a transcriptional repressor required for cell fate determination in the Drosophila eye. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1085–1096. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.6.1085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong W.C., Okano H., Patel N.H., Blendy J.A., Montell C. repo encodes a glial-specific homeo domain protein required in the Drosophila nervous system. Genes Dev. 1994;8:981–994. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yager J., Richards S., Hekmat-Scafe D.S., Hurd D.D., Sundaresan V., Caprette D.R. Control of drosophila perineurial glial growth by interacting neurotransmitter-mediated signaling pathways. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2001;98:10445–10450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191107698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T., Okabe M., Hiromi Y. EDL/MAE regulates EGF-mediated induction by antagonizing Ets transcription factor Pointed. Development. 2003;130:4085–4096. doi: 10.1242/dev.00624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in both repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue and repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly increased expression ≥ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue, but not repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly decreased expression ≤ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue.

Genes with significantly decreased expression ≤ 1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue. 22

Genes with significantly decreased expression ≤ 1.5 fold in both repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT and repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly increased expression ≥1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly increased expression ≥1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly decreased expression ≤1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-HtlACT CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.

GO analysis (cellular processes) of genes with significantly decreased expression ≤1.5 fold in repo-Gal4, UAS-InR CNS tissue. p-value ≤0.01.