Abstract

Background

Most people who quit smoking relapse within a year of quitting. Little is known about what prompts renewed quitting after relapse or how often this results in abstinence.

Purpose

To identify rates, efficacy, and predictors of renewed quit attempts after relapse during a one-year follow-up.

Methods

Primary care patients in a comparative effectiveness trial of smoking cessation pharmacotherapies reported daily smoking every 6–12 weeks for 12 months to determine relapse, renewed quitting, and 12-month abstinence rates.

Results

Of 894 known relapsers, 291 (33%) renewed quitting for at least 24 hours and 99 (34%) of these were abstinent at follow-up. The average latency to renewed quitting was 106 days and longer latencies predicted greater success. Renewed quitting was more likely for older, male, less dependent smokers, and later abstinence was predicted by fewer depressive symptoms and longer past abstinence.

Conclusions

Renewed quitting is common and produces meaningful levels of cessation.

Keywords: tobacco, smoking cessation, relapse, renewed quitting, chronic care

Currently, more than 1 billion people smoke cigarettes worldwide (1). Tobacco use kills 5.4 million people each year and remains the leading preventable cause of morbidity and mortality in the world (2). Although between 40 and 50% of cigarette smokers quit smoking for at least 24 hours annually (3,4), few remain smoke-free for at least six months (3,5), and metaanalyses suggest that even with available treatments, abstinence rates rarely exceed 35% (5). Despite the low likelihood of achieving success in each individual quit attempt, more than half of all ever-smokers in the U.S. have quit (6). This suggests that analyzing a single quit attempt does not effectively capture how change in smoking behavior occurs. Some smokers may make multiple quit attempts before achieving long-term abstinence. In order to understand the change process for such individuals, it is necessary to study these renewed attempts to quit after relapse (7).

Although repeated attempts are often required for smokers to achieve lasting abstinence (4), recent research also suggests that there may be a subpopulation of smokers for whom frequent efforts to quit are linked to lower odds of success (8,9). Given the low probability of quitting successfully in a single quit attempt (estimated as low as 5% in the population and as high as 35% in smoking cessation pharmacotherapy trials; 4–6), however, the path to lasting abstinence and its health benefits must go through renewed quit attempts after relapse (which we will refer to as "recycling" in this manuscript for the sake of brevity).

Previous research has shown that self-reported motivation to quit remains high among many relapsers following relapse (8,10–13), although there are few studies tracking cessation efforts or outcomes in the months following a failed index quit attempt. One study that looked at renewed quitting in a representative sample of adult smokers from Australia, Canada, the U.K., and the U.S. reported that nearly 6% of people who had attempted to quit and relapsed in the past month at a baseline survey reported attempting to quit again in the next 12 months (9). Other research using the four-country International Tobacco Control (ITC) sample suggested that smokers make an average of about two quit attempts per year, which suggests that self-defined quit attempts commonly occur within 12 months of a failed quit attempt (4). Another recent study of adult smokers found that, among 40 smokers who expressed an interest in quitting in the next three months, nine (23%) showed a pattern of renewed intentions after a failure to fulfill an earlier intention to quit, in just a 28 day period (14). Only two (5%) smokers who quit for a calendar day and returned to smoking for seven days re-established full-day abstinence, however. This is in line with other research highlighting the divide between self-reported quit attempts and those defined by 24-hour abstinence (15). Taken together, this evidence suggests that while recycling attempts do occur, they occur at fairly low rates in the population. Research is needed to understand the factors that influence recycling which may suggest interventions to increase the rate of renewed quitting after relapse.

Additionally, the spontaneous rate of recycling among treatment-seeking smokers who relapse in cessation trials is not known. Recycling may be more common among treatment seekers than the broader population of smokers, as seeking treatment may be a sign of greater motivation to quit. Treatment seeking may also be a sign of greater tobacco dependence (relative to the majority of smokers who attempt to quit without treatment and the majority of former smokers who have quit without treatment (16,17)). In addition, relapsing while using treatment may be more demoralizing or confidence-sapping than relapsing during an unassisted cessation attempt. Previous research has documented significant and substantial drops in motivation to quit following relapse in smokers engaged in treatment (18). As such, extant findings of population recycling rates may not apply to treatment-seeking smokers, particularly those enrolled in treatment clinical trials. In addition, because treatment seekers are already engaged in treatment and followed by health care providers, it may be possible to find ways to promote recycling beyond spontaneous rates through intervention (e.g.,12,19).

The current study sought to estimate the prevalence of behaviorally defined recycling attempts following relapse among primary care patients enrolled in a randomized clinical trial of smoking cessation pharmacotherapies (20) during a 12-month follow-up period. In addition, a secondary aim was to examine predictors of recycling attempts and self-reported motives for quitting prior to and following relapse. We also sought to identify predictors of final smoking status (i.e., point-prevalence abstinence at the end of follow-up) and describe the use of cessation aids during recycling efforts.

Past research has examined many predictors of cessation efforts, such as motivation to quit (13); social norms (21); stage of change (22); nicotine dependence level (13); environmental barriers to smoking (e.g., price increases, smoking restrictions; 23); beliefs about smoking and quitting (23–25); and specific concerns about smoking (e.g., health concerns; 8,25–27). A comprehensive review of this literature is beyond the scope of the current paper, but recent population studies of self-reported attempts to quit suggest that past quitting behavior (particularly recency of quit attempts, 9,25); desire or plans to quit (8,25), and health concerns (25) are positive predictors of quit attempts whereas positive attitudes about smoking and higher levels of nicotine dependence (25) predict reduced odds of trying to quit. It is not clear, however, whether the results of these studies will extend to renewed quitting shortly after relapse in the context of pharmacotherapy and counseling. The current study will examine relations between baseline variables including number of past quit attempts, nicotine dependence dimensions, depressive symptoms, and recency of relapse as predictors of recycling attempts in smokers enrolled in a pharmacotherapy comparative effectiveness trial.

In addition, the current study will examine self-reported motives for quitting for both the index quit attempt at the start of the clinical trial and the first recycling attempt during the one-year follow-up period. Although the same factors may prompt index and renewed quitting efforts, it is possible that some motives persist more following relapse or predict greater success in recycling efforts than do others. Identifying the motives related to recycling may help us identify targets for motivational interventions designed to encourage renewed cessation attempts.

Recent studies (8,9,23) have shown that the predictors of cessation attempts differ from predictors of cessation success, which has important public health implications. Some factors, such as recency or number of past quit attempts, may positively predict quit attempts but be associated with greater relapse risk (9,23), perhaps due to demoralization or self-regulatory resource depletion (28). For this reason, and to estimate the impact of recycling on distal smoking cessation outcomes, it is important to examine the rates and predictors of abstinence at the end of the follow-up period in the current study. Furthermore, there may be an optimal period of delay in which people can recover from and gain perspective on a relapse before trying to quit again. The current study will explore this by examining the relation between the latency of recycling after relapse and later point-prevalence abstinence. The current study will also explore individual differences that predict recycling success, which may suggest ways to tailor re-quitting encouragement and treatment to individual smokers’ needs. For example, people who are more dependent on nicotine (25,29,30) or depressed (31,32) may need new or more intensive treatments to help them turn renewed quitting efforts into lasting abstinence. Older smokers who may have more experience quitting or pressing need to quit (33), and those with longer periods of past abstinence (13), in contrast, may need less support to achieve lasting abstinence upon recycling. Studying renewed quitting efforts is an important research priority that may help update our understanding of how cessation unfolds for smokers and guide future intervention development and tailoring.

A final aim of the study was to describe the use of cessation aids during spontaneous recycling attempts to determine the prevalence and efficacy of aid use. Underuse of currently available effective cessation aids may be one reason many smokers need to make multiple attempts to quit. Population studies suggest fewer than half of smokers use any cessation aid during their quit attempts and even fewer use the most effective treatments (17,34). The current study will provide new information about the use of various cessation aids prior to the index quit attempt and during the renewed quit attempt. This information may inform the development of relapse recovery interventions.

Method

Data Source

The current project is a secondary data analysis of follow-up data from a randomized clinical effectiveness trial of five smoking cessation pharmacotherapies among primary care patients in Wisconsin (20). Patients were randomly assigned to receive one of five nicotine dependence treatments: nicotine lozenge, nicotine patch, bupropion SR, nicotine lozenge with nicotine patch, or nicotine lozenge with bupropion SR. Study participants received a supply of medications to use for 8 (bupropion or patch) to 12 (nicotine lozenge) weeks during their index quit attempt. All patients were offered toll-free individual telephone counseling and counselors from the state-sponsored tobacco quit line proactively called study participants to enroll them in a four-session counseling protocol. The present study used data during the one year period following the index quit attempt to examine renewed quitting behavior after relapse.

Participants

From October 2005 to May 2007, 1,346 patients were enrolled in the baseline study during routine visits to one of 12 primary care clinics. To be eligible for the study, participants had to be 18 years old, smoke at least 10 cigarettes per day during the past 6 months, and be motivated to quit. Patients were excluded from the study on the basis of medical history of contraindications to any of the study pharmacotherapies; currently using bupropion; allergies; history of eating disorders, bipolar disorder, or psychosis; contemplation of self-harm within the past two weeks; or dependence on drugs or alcohol. Due to contraindications of nicotine replacement therapy use in pregnancy (5), female participants were required to use an acceptable method of birth control while using study pharmacotherapy, and pregnant and breast-feeding women or those planning to become pregnant were excluded. In exchange for participating in the study, subjects received pharmacotherapies at no cost.

Procedure

Patients were screened for eligibility by primary care clinic staff and referred to investigators who called interested patients to collect oral assent, verify eligibility, conduct baseline assessment over the phone, and randomize subjects to treatment. Enrolled subjects provided written informed consent at their clinic pharmacy while picking up assigned medications. Of the 1,504 patients who completed telephone screening and verbally assented to participation, 1,346 picked up their assigned medication and signed consent. Follow-up telephone interviews among these 1,346 enrollees were conducted 12, 18, 24, 30, 42, and 52 weeks post-quit to evaluate smoking status. For relapsed smokers who reported recycling, a separate survey was administered over the phone assessing their reasons for attempting to quit again and use of any cessation aids for this renewed quit attempt.

Measures

Measures were intentionally kept brief to reduce participant burden and preserve the ‘real-world’ nature of this effectiveness study.

The Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (FTND)

The FTND was developed to measure physical nicotine dependence (35). Total scores on the six-item questionnaire range from zero to 10, with higher scores indicating greater levels of nicotine dependence. The FTND has shown fair internal consistency, positive relations with smoking (35,36), and good test-retest reliability (37).

Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68)

Two items from the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (38) subscale on social and environmental goads (i.e., prods) to smoke were included (“A lot of my friends or family smoke”, and “I’m around smokers much of the time”) to assess environmental risk for relapse. Two additional items from the craving subscale of the WISDM-68 (“I usually want to smoke right after I wake up”, “How strong are your urges when you first wake up in the morning?”) were also administered. These were the four items from the WISDM that seemed to best predict relapse proneness in the early stages of the development of the Wisconsin Predicting Patients’ Relapse Questionnaire (WI-PREPARE, 39). Scores on each pair of items were averaged to create an index of environmental risk and morning craving, respectively. Higher nicotine dependence scores have been shown to relate to smoking heaviness and relapse (30,38).

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8)

The PHQ-8 is an eight-item questionnaire used to screen patients for depressive disorders in the past year (40). Total scores range from zero to 24, and scores greater than 10 indicate depression (41). The PHQ-8 exhibits good reliability and validity (42). Research suggests depression is negatively related to the ability to quit smoking (31,32).

Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS)

The PANAS (43) consists of two 10-item mood scales designed to provide brief measures of experiences of positive and negative affect. Participants respond on a 5-point scale from 1 (very slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely) to indicate to what extent they experienced positive feelings such as “excited,” “strong,”, “alert,” and “inspired” or negative feelings such as “upset,” “scared,” “hostile,” and “ashamed” in the past week. Higher scores indicate stronger affect. These scales demonstrate high internal consistency (Positive scale Cronbach’s alpha=.89, Negative scale alpha=.85) and good validity related to clinical measures of mood and affect (43,44).

Smoking History

Items included age first smoked, number of past quit attempts, length of longest quit attempt, time since last quit attempt, and initial reasons for quitting.

Demographics

A brief demographic questionnaire was administered to characterize the sample in terms of age, gender, race, ethnicity, marital status, level of education, employment status, and household income.

Smoking Status

To reduce the influence of recall biases in self-reported smoking behavior, smokers were asked to complete timeline follow-back calendars every 6–12 weeks during the 12-month period. Such calendar methods have been shown to be fairly accurate in comparisons with prospective and real-time data (45,46) and were better suited to this effectiveness study than more frequent abstinence monitoring. Following recommendations to maximize the real-world application of the findings of this effectiveness study, biochemical verification of abstinence was not obtained (47). The operational definition of recycling was based on the conventional definitions of initial cessation and relapse used in epidemiological studies (3,48). Making a recycling attempt was defined as abstaining from smoking for one full day after smoking seven days in a row at some point during the one-year follow-up period. Subjects had to have failed to quit or relapsed (smoked daily for a week) in order to be eligible to attempt to recycle. Subjects who alternated between smoking and being abstinent without ever smoking daily for a week were considered still engaged in the initial quit attempt rather than engaging in a new recycling attempt. Subjects who did not provide follow-up data were assumed not to have recycled. The primary outcome from the renewed quit attempt was intent-to-treat point-prevalence abstinence at the end of the 52-week follow-up, defined as not smoking in the seven days prior to the final follow-up one year after the index quit attempt. In order to account for the variable onset of recycling attempts (people attempted to renew quitting at different times across the follow-up period), we also examined a secondary outcome of seven-day point-prevalence abstinence from smoking two months after the onset of the renewed quit attempt.

Recycling Reasons and Methods

At follow-up interviews, those who reported making a renewed quit attempt were asked to rate the importance of reasons for quitting on a four-point scale (from 0=not at all to 3=extremely important) and to report which cessation methods they used during the renewed quit attempt. Information on recycling reasons and methods was available for 50.8% of recyclers (n=148). Due to problems in the follow-up data collection procedure, not all smokers who reported recycling were asked about recycling reasons and methods.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS version 20.0 software (Armonk, NY). To address the first study aims, descriptive analyses were used to characterize the prevalence of renewed quitting among both the full sample of non-abstinent participants (n=1138) and among only the relapsers retained through follow-up (n=874). Descriptive analyses were also used to characterize smoker ratings of the importance of specific reasons for quitting and the types of cessation aids or methods used prior to the index attempt and during the recycling attempt. Paired sample t-tests were used to evaluate significant differences in quitting reasons between the index and first recycling attempts and Cohen’s d effect sizes were calculated (49).

For descriptive purposes, analysis of variance contrasts comparing all relapsers to non-relapsers and comparing recyclers to relapsers who did not recycle were conducted to identify baseline and demographic differences among these groups. In addition, to examine possible predictors of recycling attempts and successful abstinence following recycling, we conducted a series of logistic regression analyses. These regression models controlled for variables related to attrition because the final sample of those eligible to recycle (those who were retained and relapsed) differed significantly on several characteristics (age, marital status, income, years smoked, WISDM social goads score, as described below) from those who dropped out and did not provide information on smoking outcome. We looked for differences in renewed quit attempt rates and later abstinence rates as a function of combination versus monotherapy treatments in the parent study and found no significant differences, so treatment condition was not included in further analyses. Candidate predictors of recycling attempts and successful abstinence after recycling included: nicotine dependence (total FTND score and WISDM craving subscale items); depression score (PHQ-8 total); smoking history variables (number of past quit attempts; longest duration of past abstinence, coded 0=less than one month, 1=greater than one month); and demographics (age and gender). Non-significant predictors were trimmed from the models. Effect sizes for the regression analyses are presented as odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals.

The first logistic regression model predicted the probability of recycling (i.e., quitting for 24 hours) among those who relapsed and were retained through follow-up (n=874). A separate logistic regression model predicted the probability of achieving seven-day point-prevalence abstinence at the 52-week follow-up in those who recycled at least once (n=291). Due to missing data on the recycling questionnaire, separate logistic regressions were run to evaluate how quitting reasons or cessation aids related to abstinence success in this smaller sample (n=148). A final logistic regression evaluated how the odds of achieving abstinence was related to the latency between relapse and the first recycling attempt while controlling for other predictors related to recycling. To account for the fact that smokers recycled at different points in the follow-up period and smokers who waited longer to recycle after relapse had fewer remaining days in the follow-up period in which to relapse, the primary outcome in the model examining recycling latency effects on later abstinence was 7-day point-prevalence abstinence 2 months after the recycling attempt (n=247).

Results

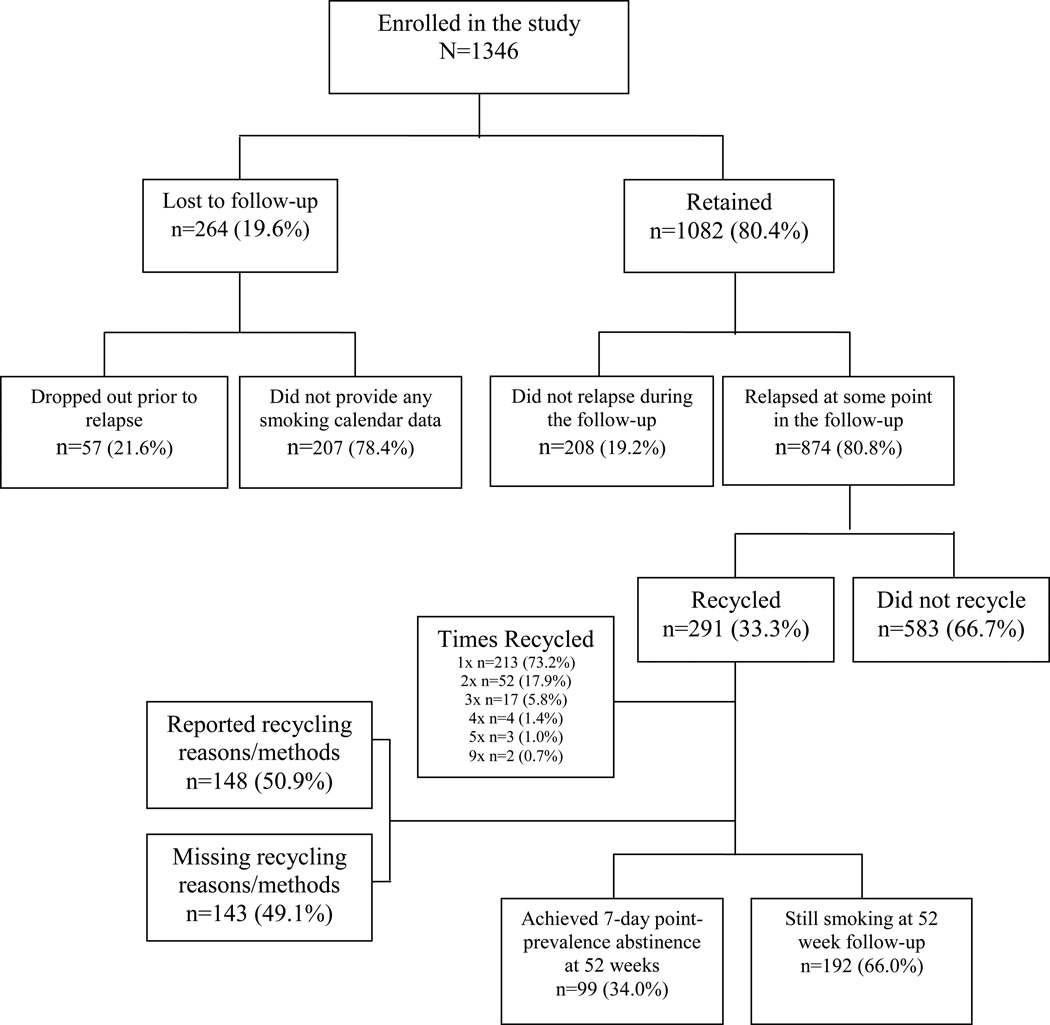

In the total sample (N=1,346), 55.9% (n=753) of subjects were female, 87.3% (n=1,175) self-identified as White, 9.5% (n=128) as African American, and 3.0% (n=43) as a member of another racial or ethnic minority. In terms of education, 13.0% (n=172) had less than a high school education, 44.4% (n=597) were high school graduates, 33.1% (n=445) had attended some college, and 9.8% (n=132) were college graduates. On average, smokers in the total sample had attempted to quit 5.6 (SD=9.3) times in the past and had smoked for 25.7 years (SD=11.6). Subjects (N=1,346) provided data on their daily smoking pattern for an average of 286.2 (SD=150.6) days during the post-quit period. Figure 1 depicts participant flow and retention through follow-up. Relative to those who supplied data, subjects lost to follow-up were significantly: younger (lost: M=41.0, SD=12.2, retained: M=45.2, SD=11.8, t(1344)=4.34, p<.001); had smoked fewer years (lost: M=23.0, SD=11.7, retained: M=26.4, SD=11.4, t(1344)=5.09, p<.001); had more exposure to smokers (based on items from the WISDM-68 social goads subscale) (lost: M=9.0, SD=3.4, retained: M=8.5, SD=3.6, t(1340)=−2.30, p=.020); were less likely to be married (lost: 45.4%, retained: 56.9%, χ2(1,N=1345)=19.06, p<.001); and were more likely to report annual income below the sample median ($50,000) (lost: 64.4%, retained: 55.6%, χ2(1,N=1280)=6.32, p=.012). Consequently, age (which was collinear with years smoked), exposure to smokers, marital status (coded 0=unmarried, 1=married), and annual income (coded 0=less than $50,000, 1=greater than or equal to $50,000) were included as control variables in all regression models to account for this differential attrition.

Figure 1.

Participant Retention and Outcome Diagram

Recycling Frequency and Success

A total of 291 (25.6%) of the 1138 enrollees who relapsed or were lost to follow-up and 33.3% of the 874 subjects known to relapse made at least one recycling attempt (i.e., quit for at least one day) during the study follow-up period. The average lag between the date of the recycling attempt onset and the follow-up interview at which this was reported was 39.9 days (SD=25.6) and no lag was longer than 80 days, well within the 20-week period in which test-retest reliability for smoking calendar methods has been found to be good (45). Selected demographics and baseline smoking history variables that differed between subjects who never relapsed, those who relapsed and recycled, and those who relapsed and did not recycle are summarized in Table 1. On average, participants initiated their first new quit attempt 156.4 days after their index quit attempt in the parent study (SD=112.1) and 106.0 days after relapse (SD=101.2). Most smokers who recycled did so only once (73.2%). The frequency of recycling attempts is presented in Figure 1. Few smokers recycled two or more times, and baseline demographic and smoking history characteristics did not significantly differ between those who recycled once and those who recycled multiple times (ƞ2=.000–.009). As such, all subsequent analyses focus on the first recycling attempt made by subjects.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics.

| Did Not Relapse | Relapsed, Recycled | Relapsed, Did Not Recycle | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | N | Mean | Std Dev | N | Mean | Std Dev | N | Mean | Std Dev |

| Current age | 208 | 47.6* | 11.5 | 291 | 46.0† | 12.2 | 583 | 43.8 | 11.6 |

| FTNDa Total Score | 208 | 4.8* | 1.9 | 290 | 5.0† | 2.1 | 583 | 5.3 | 2.0 |

| PHQb Total Score | 208 | 5.0* | 4.4 | 291 | 6.1 | 4.8 | 583 | 6.2 | 5.0 |

| WISDM-68c Craving | 207 | 13.4 | 3.9 | 291 | 13.2† | 4.2 | 582 | 14.2 | 4.0 |

| WISDM-68c Social Goads | 208 | 7.9* | 3.7 | 291 | 8.4 | 3.6 | 581 | 8.8 | 3.6 |

| Negative PANASd | 208 | 5.4* | 2.6 | 291 | 6.0 | 2.8 | 579 | 6.1 | 2.8 |

| Age started daily smoking | 208 | 18.4* | 5.0 | 291 | 17.9† | 5.0 | 583 | 16.8 | 4.0 |

| How motivated are you to stop smoking? (0–10) | 208 | 8.8* | 1.5 | 291 | 8.4 | 1.7 | 582 | 8.3 | 1.7 |

| Baseline Cigarettes per day | 208 | 19.6 | 8.2 | 291 | 19.7† | 8.3 | 583 | 21.2 | 9.2 |

| Last quit attempt (years) | 194 | 5.0 | 5.9 | 277 | 4.0 | 5.2 | 544 | 4.5 | 5.8 |

| Measure | N | n | Percent | N | n | Percent | N | n | Percent |

| Married | 208 | 134* | 64.4% | 291 | 175† | 60.1% | 582 | 307 | 52.7% |

| Female | 208 | 94* | 45.2% | 291 | 156 | 53.6% | 583 | 350 | 60.0% |

p<.05 for the contrast between smokers who never relapsed (left-hand column) and smokers who relapsed (composite of the middle and right-hand columns).

p<.05 for the contrast between smokers who relapsed and did not recycle (quit for at least 24 hours, middle column) and those who relapsed and subsequently recycled (right-hand column)

FTND: Fagerström Test of Nicotine Dependence (Heatherton et al., 1991)

PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire used to screen for depressive disorders in the past year (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002)

WISDM-68: Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (Piper et al., 2004)

Negative PANAS: Negative mood scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (Watson et al., 1988)

Thirty-four percent (n=99) of the 291 subjects (7.4% of the total sample) who made a recycling attempt (i.e., quit for at least 24 hours post-relapse) at some point during the preceding year achieved intent-to-treat seven-day point-prevalence abstinence at the one-year follow-up interview. This is in addition to the 208 (15.4% of 1,346 enrollees) of smokers who quit successfully in the initial cessation trial and did not relapse. Thus, recycling accounted for nearly a third (32.2%) of successful abstinence at one year post-quit.

Predictors of Recycling Attempts

The first logistic regression predicted the probability of recycling (i.e., quitting for at least 24 hours) among those who relapsed (n=824) (Table 2). Results indicated that baseline craving score (on the WISDM) was negatively related to the probability of recycling and age was positively related to recycling. In addition, there was a marginally significant relation between gender and renewing a quit attempt, such that women were less likely to recycle than were men. Annual income data was not reported for n=50 participants and excluding income from the model did not change the pattern of results.

Table 2. Regression Predicting Recycling Attempt.

Unadjusted (univariate) and adjusted (multivariate) regression coefficients for predictors of recycling attempts (recycled vs. relapsed and did not recycle) among smokers who relapsed following the initial quit attempt (n=824) controlling for variables related to attrition. OR=Odds Ratio. 95% CI=95% Confidence Interval.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 1.015 | [1.003–1.027] | 0.015 | 1.020 | [1.007–1.034] | 0.004 |

| WISDM-68a Social Goads | 0.973 | [0.936–1.012] | 0.170 | 0.978 | [0.937–1.021] | 0.321 |

| Married (1=yes, 0=no) | 1.351 | [1.016–1.798] | 0.039 | 1.325 | [0.958–1.834] | 0.089 |

| Income (1=≥$50,000; 0=<$50,000) | 1.076 | [0.805–1.440] | 0.620 | 0.870 | [0.627–1.207] | 0.403 |

| Gender (1=female, 0=male) | 0.769 | [0.579–1.022] | 0.070 | 0.742 | [0.546–1.008] | 0.056 |

| WISDM-68a Craving | 0.950 | [0.919–0.983] | 0.003 | 0.936 | [0.903–0.970] | 0.000 |

WISDM-68: Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) (Piper et al., 2004)

Reasons for Quitting

The reported importance of reasons for making the initial quit attempt and the first subsequent recycling attempt are compared in Table 3. The reasons viewed as most important by subjects for the renewed quit attempt were: disliking being addicted; wanting to adopt a healthier lifestyle; protecting the health of family members; setting an example for one’s children; the cost of cigarettes; and current health problems. Mean ratings for other reasons for quitting were below the midpoint on the scale (i.e., rated as somewhat important or less). Correlations between ratings of the importance of reasons for quitting during the initial quit attempt and the recycling attempt were significant but modest (ranging between r=.26 and r=.39, all ps <.05) for all items except those related to family (r=.62 for setting an example for one’s children and r=.46 for children’s or family health, ps <.05) and one’s own health problems (r=.14, n.s.).

Table 3.

Importance Rating of Reasons to Quit Smoking.

| Motive importance (from 0–3) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reason | Baseline Rating (N=148) |

Recycling Rating (N=148) |

Pearson Correlation |

Cohen's d | ||

| Mean | Std Dev | Mean | Std Dev | |||

| Dislike being addicted | 2.3 | 0.8 | 2.0** | 0.9 | 0.2 | −0.34 |

| For children or family health | 2.2 | 0.9 | 1.9** | 1.0 | 0.4 | −0.32 |

| Adopting a healthy lifestyle | 2.2 | 0.8 | 2.0** | 0.8 | 0.2 | −0.30 |

| Health problems | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.6** | 1.0 | 0.1 | −0.30 |

| Example for children | 1.8 | 1.2 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 0.6 | −0.04 |

| Cost | 1.6 | 1.0 | 1.6 | 1.0 | 0.4 | −0.06 |

| Encouragement of friend/relative | 1.5 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 1.0 | 0.2 | −0.06 |

| Advice of MD or health professional | 1.4 | 1.0 | 1.5 | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.10 |

| Friend/relative smoking related illness | 1.4 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 0.3 | −0.12 |

| Willpower | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.3* | 1.0 | 0.2 | 0.20 |

| Home smoking restrictions | 0.8 | 1.1 | 0.8 | 1.0 | 0.3 | −0.02 |

| Workplace smoking restrictions | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.6 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.00 |

Table 3. Smokers rated reasons for quitting smoking from 0–3 at the index quit attempt and if they reported a recycling attempt. Average importance ratings were compared and effect size estimates of the difference were calculated. Significant differences are labeled ** p<.01, * p<.05.

Differences between initial importance ratings for the entire sample (N=1,346) and just those who recycled (n=148) were compared to later importance ratings for the recycling attempt (n=148) and the pattern of results did not differ, so the results for the sample of recyclers are presented for economy.

Predictors of Recycling Success

A second logistic regression model predicted successful abstinence among those who recycled (n=291) (Table 4). Seven-day point-prevalence abstinence at the 52-week follow-up was positively related to quitting for longer than one month in the past and negatively related to baseline depression severity. Annual income was missing for n=15 participants and excluding income in this model only affected the depression estimate slightly (Odds Ratio=.95, 95% CI Odds Ratio 0.90–1.01 in this alternate model).

Table 4. Regression Predicting Recycling Success.

Unadjusted (univariate) and adjusted (multivariate) regression coefficients predicting the odds of recycling success (7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 52 week follow-up) among those who recycled (n=291) while controlling for variables related to attrition, excluding income. OR=Odds Ratio. 95% CI=95% Confidence Interval.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 1.017 | [0.997–1.038] | 0.091 | 1.017 | [0.996–1.039] | 0.123 |

| WISDM-68a Social Goads | 0.959 | [0.896–1.026] | 0.220 | 0.963 | [0.897–1.033] | 0.288 |

| Married (1=yes, 0=no) | 1.425 | [0.861–2.359] | 0.168 | 1.246 | [0.734–2.114] | 0.416 |

| PHQb Total Score | 0.935 | [0.884–0.988] | 0.017 | 0.939 | [0.887–0.994] | 0.030 |

| Quit for longer than 1 month in the past (1=yes, 0=no) | 1.834 | [1.110–3.030] | 0.018 | 1.914 | [1.144–3.202] | 0.013 |

WISDM-68: Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) (Piper et al., 2004)

PHQ: Patient Health Questionnaire used to screen for depressive disorders in the past year (Kroenke & Spitzer, 2002)

The number of days between relapse and a first renewed quit attempt (n=247, M=86.38, SD=82.89) was positively related to seven-day point-prevalence abstinence two months later, when controlling for other predictors related to recycling (Table 5). That is, those who waited longer to renew quitting after a relapse were more likely to be smoke-free two months later than were those who renewed quitting more quickly.

Table 5. Regression Predicting Recycling Success: Time since Relapse.

Unadjusted (univariate) and adjusted (multivariate) regression coefficients predicting the odds of achieving abstinence (7-day point prevalence abstinence 2 months after recycling) based on the time interval between relapse and recycling (n=247). OR=Odds Ratio. 95% CI=95% Confidence Interval.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 0.998 | [0.978–1.019] | 0.860 | 0.999 | [0.977–1.021] | 0.918 |

| WISDM-68a Social Goads | 0.966 | [0.900–1.037] | 0.342 | 0.178 | [0.879–1.024] | 0.949 |

| Married (1=yes, 0=no) | 1.179 | [0.700–1.985] | 0.536 | 1.611 | [0.882–2.943] | 0.121 |

| Income (1=≥$50,000; 0=<$50,000) | 0.854 | [0.507–1.441] | 0.555 | 0.730 | [0.409–1.300] | 0.285 |

| Quit for longer than 1 month in the past (1=yes, 0=no) | 1.646 | [0.984–2.754] | 0.058 | 2.095 | [1.199–3.658] | 0.009 |

| Latency since relapse | 1.003 | [1.000–1.006] | 0.079 | 1.003 | [1.000–1.007] | 0.039 |

WISDM-68: Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) (Piper et al., 2004)

Separate logistic regressions analyzed whether particular reasons for initiating a renewed quit attempt or particular cessation aids used during this attempt predicted seven-day pointprevalence abstinence at 52 weeks (n=148) (Table 6). Endorsing a desire to test one’s willpower as a motive for initiating a renewed quit attempt was associated with lower odds of abstinence at 52 weeks.

Table 6. Regression Predicting Recycling Success: Reasons and Methods for Recycling.

Unadjusted (univariate) and adjusted (multivariate) regression coefficients predicting the odds of recycling success (7-day point-prevalence abstinence at 52 week follow-up) from reported reasons and methods for recycling among smokers who answered the recycling questionnaire (n=148). OR=Odds Ratio. 95% CI=95% Confidence Interval.

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p |

| Age | 1.001 | [0.975–1.028] | 0.934 | 1.021 | [0.990–1.054] | 0.185 |

| WISDM-68a Social Goads | 0.969 | [0.884–1.061] | 0.495 | 0.993 | [0.896–1.101] | 0.898 |

| Married (1=yes, 0=no) | 1.362 | [0.695–2.668] | 0.368 | 1.173 | [0.516–2.663] | 0.703 |

| Income (1=≥50,000; 0=<$50,000) | 1.694 | [0.868–3.305] | 0.123 | 1.778 | [0.800–3.951] | 0.158 |

| Willpower | 0.688 | [0.500–0.945] | 0.021 | 0.653 | [0.460–0.928] | 0.017 |

| Used medication (1=yes, 0=no) | 0.724 | [0.360–1.455] | 0.364 | 0.507 | [0.231–1.111] | 0.090 |

WISDM-68: Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) (Piper et al., 2004)

Methods for Quitting

Use of cessation aids prior to the index quit attempt and during the recycling attempt are summarized in Table 7. Most respondents used at least one resource or medication for cessation prior to the index quit attempt and during the recycling attempt. Gradual and abrupt quitting were both common (endorsed by over 70% of smokers) prior to the index attempt, but gradual quitting was rare (endorsed by fewer than 15% of smokers) during recycling attempts. Most methods were used at lower rates during the recycling attempt than in previous attempts, except that the medications provided in the study for the index quit attempt (nicotine lozenges, patches, and/or bupropion SR) were used at high rates (18–28%) during recycling, presumably because people had these medications left over from the index quit attempt. Use of methods not supported by evidence (e.g., laser treatments) was rare during recycling attempts. More than 10% of recyclers who were asked about cessation methods tried varenicline (approved by the FDA and made available in the middle of data collection for this study) during the one-year follow-up period. Use of any medication in the recycling attempt was not significantly related to achieving abstinence.

Table 7. Use of Smoking Cessation Aids.

Subjects reported all smoking cessation aids they had ever used prior to the index quit attempt (N=1,346) and could select multiple categories. This does not include information on the cessation aids used during the index quit attempt in the parent study because subjects were randomized to one of five pharmacotherapies, as described in the text. Subjects reported any smoking cessation aid they used during the first recycling attempt (n=148).

| Prior to Index Quit Attempt (N=1,346) |

First Recycling Attempt (N=148) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method | Frequency | Percent | Frequency | Percent |

| 1. Cold Turkey | 1,045 | 77.6% | 43 | 29.0% |

| 2. Cutting Back | 944 | 70.1% | 22 | 14.8% |

| 3. Switch Tobacco Form | 745 | 55.4% | 6 | 4.0% |

| 4. Quit with Others | 603 | 44.8% | 2 | 1.4% |

| 5. Self-Help | 301 | 22.4% | 1 | 0.6% |

| 6. Medication Support Program | 180 | 13.4% | 3 | 2.0% |

| 7. Counseling | 169 | 12.6% | 5 | 3.4% |

| 8. Hypnosis, Acupuncture, Laser | 266 | 19.8% | 3 | 2.0% |

| 9. Nicotine Patch | 599 | 44.5% | 39 | 26.4% |

| 10. Nicotine Lozenge | 93 | 6.9% | 42 | 28.4% |

| 11. Other Nicotine Replacement | 434 | 32.2% | 5 | 3.4% |

| 12. Bupropion | 416 | 30.9% | 27 | 18.2% |

| 13. Varenicline | Not assessed | 15 | 10.1% | |

| 14. Any help (items 4–14) | 1,065 | 79.1% | 105 | 71.0% |

Discussion

This study sought to describe renewed quitting efforts in the year following an initial, assisted quit attempt. Results indicated that recycling, or re-establishing at least 24 hours of abstinence after relapse, is both fairly common and often successful. In this large study, 33.3% of smokers who were known to relapse made another quit attempt within a year and 34.0% of those were able to achieve abstinence at the end of the follow-up period. Renewed quitting accounted for roughly one-third of all point prevalence abstinence one year after a target quit day. Among smokers who have previously used pharmacotherapy to aid in a quit attempt, our data suggest motives for initial and recycling quit attempts differ and many people use cessation aids when trying to recycle. However, the latter finding may reflect the availability of pharmacotherapy left over from the initial quit attempt in this clinical trial. Models of recycling attempts and successful abstinence from recycling identified some risk and protective factors that could suggest promising candidates for further research on recycling efforts and success.

The present study is among the first to document the rate of spontaneous recycling following relapse in a sample of treatment-seekers. These results provide important prospective information about the stability of cessation in a one-year period following an initial attempt and how often smokers rebound during that time after failing to quit initially with effective pharmacotherapies and counseling. The finding that one-third of smokers who relapsed (smoked at least seven days in a row after a target quit day) established at least 24-hours of abstinence within a year is promising and adds to data suggesting that smokers remain motivated to quit after failing to establish or maintain abstinence (7). This rate of renewed quitting is lower than the rate of reported willingness to re-quit after relapse in other studies (10,11) but higher than the 6% rate of self-reported renewed quit attempts in an 11-month follow-up period in a recent international population study (9). The rate of recycling in the present study is likely a better reflection of serious, committed cessation efforts, rather than stated intentions to quit.

Results indicated that recycling can be successful; 34.0% of recyclers went on to achieve seven-day point-prevalence abstinence at the one-year follow up. This means that 32.2% of the 307 subjects who achieved abstinence a year after the index attempt recycled at least once. This is only slightly lower than the rate reported in Lando et al. (7) where 41.0% of smokers who were abstinent one-year post quit reported relapsing at some point in the follow-up. The 34.0% abstinence rate among those who relapsed and recycled exceeds the one-year abstinence rate for the entire sample (22.8%) and for most prospective studies of cessation (e.g., 5), perhaps because those who renew quitting efforts within months of a failed attempt may be particularly motivated to quit. The definition of recycling used here (abstaining for at least a full day) may also reflect an ability to quit that is necessary to achieve long-term cessation. Consistent with past research (50), being able to achieve cessation for at least 24 hours may be a better predictor of sustained quitting than reported quitting intentions. Finally, it is possible that this abstinence rate is higher among recyclers than the whole sample because recycling attempts were more recent (occurring an average of 106 days following relapse) and the one-year abstinence rate does not reflect the full toll of relapse over 12 months following the beginning of the recycling attempt. Although these issues make it difficult to compare abstinence rates for recycling and index quit attempts, the absolute rate of abstinence among recyclers suggests that promoting recycling, at least at some delay after relapse, may meaningfully enhance long-term abstinence rates.

The most important self-reported reasons motivating a recycling attempt were health, family, and wanting to be free of addiction, rather than the costs of smoking or environmental restrictions on smoking. Interestingly, reasons for recycling were only moderately correlated with reasons for quitting during the initial quit attempt, with the exception of quitting for the health of one’s family or as an example for children. The importance of reasons for quitting therefore appears to be somewhat mutable. The average importance rating for most quitting motives was lower for the recycling attempt compared to the initial quit attempt, and the motives most likely to decrease over time were the ones rated highest at the initial quit attempt. This may reflect regression to the mean or the impact of relapse on cessation motivation. Further research is needed to understand and predict stability in cessation motivation.

This study provides initial, exploratory information about promising candidates for further research on recycling efforts and success. In line with previous literature (8,9,23), our results indicate that the factors promoting quit attempts are distinct from those predicting long-term quitting success. This may suggest a need for complementary intervention approaches to improve rates of quit attempts and quitting success. Recycling attempts were less likely among smokers who were female, younger, and more nicotine dependent. This suggests certain treatment-seeking smokers may be less likely to persist in quitting after relapse. Furthermore, smokers higher in depression were less likely to achieve abstinence after recycling than were others, which may suggest a need for more intensive treatment to enhance cessation success in these smokers. Lastly, smokers who had quit for longer in the past were more likely to achieve abstinence at follow-up after their recycling attempt, consistent with past research (13). This suggests promoting recycling is beneficial because quit attempts over time may help people learn new skills to tolerate withdrawal or cope with craving. At the same time, promoting recycling shortly after relapse may be suboptimal, as suggested by theories of demoralization (9,28) and studies indicating greater relapse risk among smokers with more recent quit attempts and more failed quit attempts (9,23). Our results indicate recycling was more successful among smokers who delayed their re-quit attempt compared to smokers who attempted to quit earlier after a failed attempt. Thus, there may be an optimal delay after relapse where recycling is more likely to promote cessation. We were not able to explore the specific mechanisms that may account for the improved success of delayed recycling efforts in this study. Further research is needed to illuminate the time-course of processes influencing recycling efforts and success.

Descriptive analyses of cessation methods used indicated that more than 70% of smokers used some form of assistance or treatment both before the initial quit attempt and during the recycling attempt. The data also suggested that recyclers did not give up on pharamacotherapies from the initial, failed quit attempt, but instead used these medications at high rates in the recycling attempt. It is notable that 10% of those asked about methods used during the recycling attempt reported trying varenicline, the newest medication on the market. Use of medications did not predict point-prevalence abstinence following recycling, however, and it is not clear how long or consistently people used these medications. It is possible there was not sufficient variance in medication use in predicting long-term cessation from recycling because the largest effect of medication use may have been promoting the first 24 hours of cessation (recycling attempts).

The current study has important limitations. First, defining recycling as achieving at least 24 hours of abstinence may underestimate the number of renewed quit attempts by excluding attempts that resulted in shorter durations of abstinence. Second, we captured smokers at one point in their cessation history rather than at the very beginning of their efforts to quit (i.e., the index quit attempt is likely a renewed rather than first-ever quit attempt). Many smokers reported their most recent quit attempt prior to the index attempt was one year ago (25.3%) or sooner (13.6%). Although participant burden was minimized to preserve this study of effectiveness, smokers in the present sample agreed to participate in a research study using pharmacotherapies so findings may not generalize to smokers quitting on their own. Smokers lost to follow-up differed from those retained, which may further constrain generalizability. We attempted to control statistically for the factors associated with this differential attrition in models of recycling attempts and abstinence. In addition, although the modal number of recycling attempts was one, some subjects reported multiple recycling attempts. Only the first recycling attempt was analyzed however, as too few people (26.8%) made multiple attempts to permit meaningful comparisons across separate attempts. Future research would benefit from analyzing changes from one recycling attempt to the next.

The descriptive analyses of reasons for recycling and cessation methods used during recycling attempts are preliminary, as these data were collected for only half of the sample of smokers who met our definition of recycling due to problems in the data collection protocol. This likely occurred at random, but still limits the interpretation of these results. Additionally, recycling questionnaires were administered during scheduled follow-up interviews and thus there were significant time lags between the renewed quit attempt itself and the assessment of the reasons and methods used (an average of 5.5 weeks with a standard deviation of 3.5 weeks).

Despite these limitations, the present study provides important new information about the process of quitting smoking. This study provides valuable information about the spontaneous rate of recycling and promising candidates for future research on the factors related to renewed cessation attempts and successful abstinence. Results suggest that more than a quarter of relapsers recycle within a year and more than a third of recyclers achieve sustained (seven-day) abstinence within a year. Renewed quitting accounts for a substantial proportion of distal point-prevalence abstinence rates which has important implications for treatment efficacy studies, as some distal abstinence may reflect renewed quitting independent of treatment. Additionally, these findings provide empirical support for chronic care approaches to smoking intervention for smokers who do not initially achieve cessation. Smokers appear to recover fairly quickly from relapse and become adequately motivated for renewed quit attempts and quitting success. The fact that quitting success increased as a positive function of time since relapse supports the use of extended treatment rather than short-term encouragement to recycle immediately after cessation failure (see 51,52). In addition, the importance of reasons for recycling were only weakly correlated with reasons for quitting previously, suggesting that the factors that prompt recycling may differ from those that prompt earlier cessation efforts. Some groups of smokers may need encouragement to recycle and additional support to achieve abstinence during renewed quit attempts. Examining multiple quit attempts in smoking cessation studies may help us update treatment efforts to include ongoing treatment for smokers who relapse and identify ways to effectively promote lasting abstinence through continued engagement in the cessation process.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant 5P50DA019706 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and grant 1K05CA139871 from the National Cancer Institute. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health, the National Institute on Drug Abuse, or the National Cancer Institute.

None of the authors (KW Bold, AS Rasheed, DE McCarthy, TC Jackson, MC Fiore, TB Baker) have disclosures or conflicts of interest related to this article or study. GlaxoSmithKline provided research medication at no cost to study participants, but played no role in the design, implementation, analysis, or reporting of these results. All procedures, including the informed consent process, were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Tobacco Free Initiative. 2010 ( www.who.int/tobacco/mpower/tobacco_facts/en/index.html)

- 2.World Health Organization Global Report. Mortality attributable to tobacco. 2012 ( http://whqlibdocwhoint/publications/2012/9789241564434_engpdf)

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quitting smoking among adults-United States, 2001–2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1513–1519. Retrieved from http://wwwcdcgov/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Borland R, Partos TR, Yong H-H, Cummings KM, Hyland A. How much unsuccessful quitting activity is going on among adults smokers? Data from the International Tobacco Control Four Country cohort survey. Addiction. 2012;107:673–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03685.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. public health service clinical practice guideline. Respir Care. 2008;53:1217–1222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cigarette smoking among adults-United States, 2000. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2002;51:642–645. Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lando HA, McGovern PG, Barrios FX, Etringer BD. Comparative evaluation of American Cancer Society and American Lung Association smoking cessation clinics. Am J Public Health. 1990;80:554–559. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.5.554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borland R, Yong HH, Balmford J, et al. Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four country project. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:s4–s11. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Partos TR, Borland R, Yong HH, Hyland A, Cummings KM. The quitting rollercoaster: How recent quitting history affects future cessation outcomes (data from the International Tobacco Control 4-Country Cohort Study) Nicotine and Tob Res. 2013;15:1578–1587. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntt025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fu SS, Partin MR, Snyder A, et al. Promoting repeat tobacco dependence treatment: Are relapsed smokers interested? Am J Manag Care. 2006;12:235–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Joseph A, Rice K, An L, Mohiuddin A, Lando H. Recent quitters' interest in recycling and harm reduction. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:1075–1077. doi: 10.1080/14622200412331324893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carlini BH, McDaniel AM, Weaver MT, Kauffman RM, Cerutti B, Stratton RM, Zbikowski SM. Reaching out, inviting back: Using interactive voice response (IVR) technology to recycle relapsed smokers back to Quitline treatment-A randomized controlled trial. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:507–515. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhou X, Nonnemaker J, Sherril B, Gilsenan AW, Coste F, West R. Attempts to quit smoking and relapse: Factors associated with success or failure from the ATTEMPT cohort study. Addict Behav. 2009;34:365–373. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hughes JR, Solomon LJ, Fingar JR, Naud S, Helzer JE, Callas PW. The natural history of efforts to stop smoking: A prospective cohort study. Drug Alc Depend. 2013;128:171–174. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2012.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hughes JR, Callas PW. Definition of a quit attempt: A replication test. Nicotine Tob Res. 2010;12:1176–1179. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntq165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hughes JR, Gulliver SB, Fenwick JW, et al. Smoking cessation among self-quitters. Health Psychol. 1992;11:331–334. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.5.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shiffman S, Brockwell SE, Pillitteri JL, Gitchell JG. Use of smoking-cessation treatments in the United States. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34:102–111. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hedeker D, Mermelstein RJ. Application of random-effects regression models in relapse research. Addiction. 1996;91:S211–S229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Partin MR, An LC, Nelson DB, et al. Randomized trial of an intervention to facilitate recycling for relapsed smokers. Amer J Prev Med. 2006;31:293–299. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smith SS, McCarthy DE, Japuntich SJ, et al. Comparative effectiveness of 5 smoking cessation pharmacotherapies in primary care clinics. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:2148–2155. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van den Putte B, Yzer M, Willemsen MC, de Bruijn GJ. The effects of smoking self-identify and quitting self-identify on attempts to quit smoking. Health Psychol. 2009;28:535–544. doi: 10.1037/a0015199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Fairhurst SK, Velicer WF, Velasquez MM, Rossi JS. The process of smoking cessation: An analysis of precontemplation, contemplation, and preparation stages of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1991;59(2):295–304. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.2.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.West R, McEwen A, Bolling K, Owen L. Smoking cessation and smoking patterns in the general population: A 1-year follow-up. Addiction. 2001;96:891–902. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2001.96689110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dijkstra A, De Vries H, Bakker M. Pros and cons of quitting, self-efficacy, and the stages of change in smoking cessation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(4):758–763. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hyland A, Borland R, Li Q, et al. Individual-level predictors of cessation behaviors among participants in the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15:iii83–iii94. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hymnowitz N, Cummings KM, Hyland A, Lynn WR, Pechacek TF, Hartwell TD. Predictors of smoking cessation in a cohort of adult smokers followed for five years. Tob Control. 1997;6:S57–S62. doi: 10.1136/tc.6.suppl_2.s57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCaul KD, Hockemeyer JR, Johson RJ, Zetocha K, Quinlan K, Glasgow RE. Motivation to quit using cigarettes: A review. Addict Behav. 2006;31:42–56. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yzer MC, van den Putte B. Understanding smoking cessation: The role of smokers’ quit history. Psychol Addict Behav. 2006;20:356–361. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Japuntich SJ, Leventhal AM, Piper ME, Bolt DM, Roberts LJ, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Smoker characteristics and smoking-cessation milestones. Am J of Prev Med. 2011;40:286–294. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piper ME, McCarthy DE, Bolt DM, et al. Assessing dimensions of nicotine dependence: An evaluation of the Nicotine Dependence Syndrome Scale (NDSS) and the Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM) Nicotine Tob Res. 2008;10:1009–1020. doi: 10.1080/14622200802097563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Japuntich SJ, Smith SS, Jorenby DE, Piper ME, Fiore MC, Baker TB. Depression predicts smoking early but not late in a quit attempt. Nicotine Tob Res. 2007;9:677–686. doi: 10.1080/14622200701365301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niaura R, Britt DM, Shadel WG, et al. Symptoms of depression and survival experience among three samples of smokers trying to quit. Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15:13–17. doi: 10.1037/0893-164x.15.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferguson J, Bauld L, Chesterman J, Judge K. The English smoking treatment services: One-year outcomes. Addiction. 2005;100:59–69. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kotz D, Fidler J, West R. Factors associated with the use of aids to cessation in English smokers. Addiction. 2009;104:1403–1410. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02639.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heatherton TF, Kozlowski LT, Frecker RC, Fagerstrom KO. The Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. Br J Addict. 1991;86:1119–1127. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1991.tb01879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Payne TJ, Smith PO, McCracken LM, McSherry WC, Antony MM. Assessing nicotine dependence: A comparison of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire (FTQ) with the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence (FTND) in a clinical sample. Addict Behav. 1994;19:307–317. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90032-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pomerleau CS, Carton SM, Lutzke ML, Flessland KA, Pomerleau OF. Reliability of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire and the Fagerstrom Test for Nicotine Dependence. Addict Behav. 1994;19:33–39. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Piper ME, Piasecki TM, Federman EB, et al. A multiple motives approach to tobacco dependence: The Wisconsin Inventory of Smoking Dependence Motives (WISDM-68) J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72:139–154. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bolt DM, Piper ME, McCarthy DE, et al. The Wisconsin Predicting Patients’ Relapse questionnaire. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(5):481–492. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL. The PHQ-9: A new depression diagnostic and severity measure. Psychiatr Ann. 2002;32:509–515. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kroenke K, Strine TW, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, Berry JT, Mokdad AH. The PHQ-8 as a measure of current depression in the general population. J Affect Disord. 2009;114:163–173. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2008.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pressler SJ, Subramanian U, Perkins SM, et al. Measuring depressive symptoms in heart failure: Validity and reliability of the Patient Health Questionnaire–8. Am J Crit Care. 2011;20:146–152. doi: 10.4037/ajcc2010931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS Scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;47:1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS): Construct validity, measurement properties and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. Br J Clin Psychol. 2004;43:245-265.41. doi: 10.1348/0144665031752934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brown RA, Burgess ES, Sales SD, Whiteley JA, Evans DM, Miller IW. Reliability and validity of a smoking timeline follow-back interview. Psychol Addict Behav. 1998;12:101–112. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shiffman S. How many cigarettes do you smoke? Assessing cigarette consumption by global report, time-line follow-back, and ecological momentary assessment. Health Psychol. 2009;28:519–526. doi: 10.1037/a0015197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Society for Research on Nicotine & Tobacco (SRNT) subcommittee on biochemical verification. Biochemical verification of tobacco use and cessation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2002;4:149–159. doi: 10.1080/14622200210123581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shiffman S, Scharf DM, Shadel WG, et al. Analyzing milestones in smoking cessation: illustration in a nicotine patch trial in adult smokers. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:276–285. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cohen J. A power primer. Psychol Bull. 1992;112(1):155–159. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.112.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Westman EC, Behm FM, Simel DL, Rose JE. Smoking behavior on the first day of a quit attempt predicts long-term abstinence. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:335–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ellerbeck EF, Mahnken JD, Cupertino AP, et al. Effect of varying levels of disease management on smoking cessation: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(7):437–446. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-7-200904070-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Joseph AM, Fu SS, Lindgren B, et al. Chronic disease management for tobacco dependence: a randomized, controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(21):1894–1900. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]