Abstract

The use of in vivo Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) data to determine the molecular architecture of a protein complex in living cells is challenging due to data sparseness, sample heterogeneity, signal contributions from multiple donors and acceptors, unequal fluorophore brightness, photobleaching, flexibility of the linker connecting the fluorophore to the tagged protein, and spectral cross-talk. We addressed these challenges by using a Bayesian approach that produces the posterior probability of a model, given the input data. The posterior probability is defined as a function of the dependence of our FRET metric FRETR on a structure (forward model), a model of noise in the data, as well as prior information about the structure, relative populations of distinct states in the sample, forward model parameters, and data noise. The forward model was validated against kinetic Monte Carlo simulations and in vivo experimental data collected on nine systems of known structure. In addition, our Bayesian approach was validated by a benchmark of 16 protein complexes of known structure. Given the structures of each subunit of the complexes, models were computed from synthetic FRETR data with a distance root-mean-squared deviation error of 14 to 17 Å. The approach is implemented in the open-source Integrative Modeling Platform, allowing us to determine macromolecular structures through a combination of in vivo FRETR data and data from other sources, such as electron microscopy and chemical cross-linking.

Mapping the organization and function of the cell requires characterization of the structure and dynamics of biological assemblies (1, 2). However, the construction of models consistent with experimental data is often hampered by data sparseness due to incomplete measurements, data noise due to measurement errors, data ambiguity due to multiple copies of the same component in the assembly, and data mixture due to multiple structural states in a compositionally and conformationally heterogeneous sample.

Traditional modeling aims to find a single structural model by minimizing the difference between the data computed from the model and the experimental data. The noise in the data is typically not modeled accurately and thus biases the estimate of model precision. In contrast, Bayesian structural modeling (3, 4) interprets experimental data more objectively by explicitly accounting for data noise and prior knowledge about the system. Here, we developed a Bayesian approach that converts data from in vivo Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET)1 spectroscopy into quantitative distance restraints suitable for structural modeling. The approach is available as part of the open-source Integrative Modeling Platform (IMP) (5, 6). IMP is a platform for integrative structure determination of macromolecular assemblies, based on a variety of experimental data, such as electron microscopy images and density maps, chemically cross-linked residue pairs, small angle x-ray scattering profiles, and various proteomics data (2, 7–10).

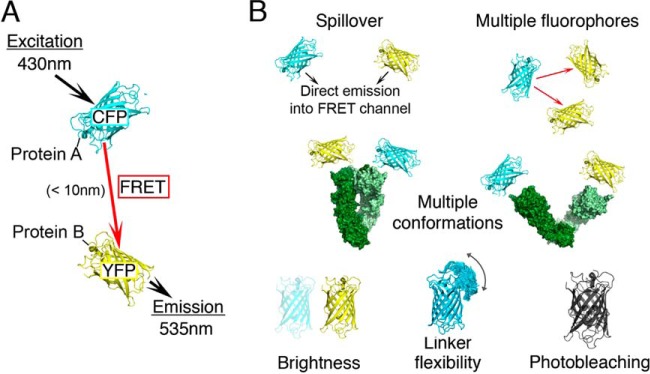

FRET is a powerful technique for studying protein–protein interactions both in vitro and in living cells (11, 12). FRET occurs when two spectrally matched fluorescent molecules are in close proximity and excitation energy is transferred from the donor to the acceptor fluorophore through nonradiative dipole–dipole coupling (Fig. 1A). The efficiency of this process (13) is a common experimentally derived variable of in vitro single-molecule experiments (14). It has been used to probe distances over the range of 1 to 10 nm, resulting in spatial restraints for modeling the structure of the studied complex (15, 16).

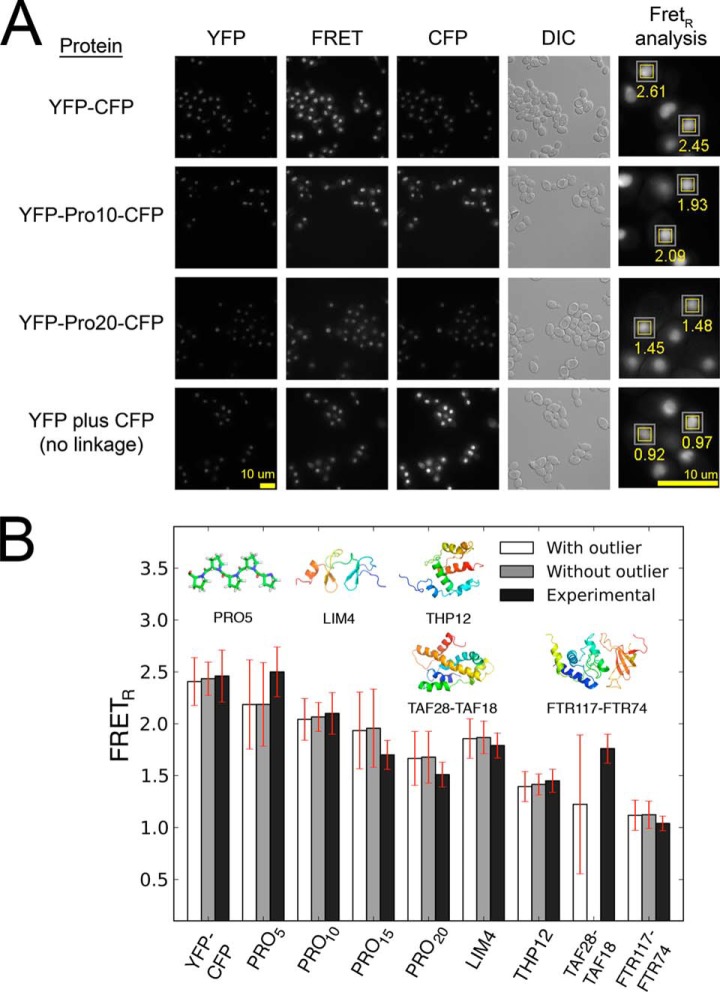

Fig. 1.

In vivo FRET microscopy. A, two proteins of interest are tagged with pairs of colored variants of GFP, typically CFP and YFP. When CFP is illuminated (λex = 430 nm) and the two fluorophores are sufficiently close, energy transfer occurs and fluorescence is measured at both CFP (λem = 470 nm) and YFP (λem = 535 nm) excitation wavelengths. The efficiency of energy transfer can be used to measure the distance between the two proteins. Typically, only the protein termini of each subunit are tagged with GFP; the total number of FRETR data points per complex that can be used in structural modeling is thus N(2N − 1), where N is the number of subunits in the complex. B, a quantitative use of in vivo FRET data is complicated by data sparseness, multiple conformations, signal contributions from multiple donors and acceptors, uneven fluorophore brightness, photobleaching, flexibility of the linker connecting the fluorophore to the tagged protein, and spillover of donor and acceptor fluorescence.

Compared with in vitro FRET, in vivo FRET measurements present several additional challenges (17) (Fig. 1B) that mainly originate from the use of donor–acceptor pairs of color variants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) (18, 19). Despite significant progress (20), these proteins are not ideal FRET partners, and four sources of noise that affect in vitro FRET are amplified. First, the unequal brightness of the two fluorophores can lead to different saturation levels in the donor and acceptor images. Second, the emission and excitation wavelengths of the GFP variants are broad and lead to contamination of the emission from energy transfer with light derived from direct emission from both donor and acceptor (direct acceptor excitation and spectral cross-talk). Third, in the case of the common FRET pair CFP–YFP, YFP is photobleached with exposure to the CFP excitation light and thus becomes gradually inactive during data collection. Fourth, fluorescent proteins are often attached to the tagged protein by means of long, flexible linkers that increase the structural variability of the system. In addition, some complexes may be composed of proteins that do not have 1:1 stoichiometry, and this complicates the interpretation of FRET data in terms of distances between individual components. Many of these problems can be overcome with the use of an experimental approach that measures fluorescence lifetimes of FRET donors (21). However, in many situations in live cells in which a complex is in low abundance, fluorescence lifetime measurements are not feasible (22).

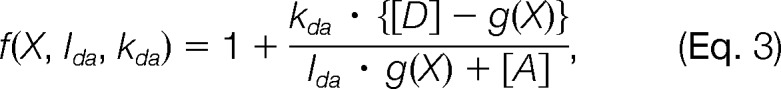

The measurement of additional observables has been proposed to supplement the FRET efficiency as a way to address some of these problems (23). Among these observables is the FRETR index (24–26), a ratio that measures the fluorescence intensity at donor excitation and acceptor emission wavelengths relative to a calculated baseline expected in the absence of FRET. Our Bayesian approach computes this observable for a given structure while accounting for all sources of uncertainty of the in vivo FRETR data listed above, as well as for the presence of multiple distinct conformations in the sample (28, 29).2 As a result, we can now use FRETR data to determine the molecular architectures of protein complexes in vivo.

Computational Methods and Experimental Procedures—

The FRETR Index

FRETR (24, 25) is an index of relative FRET in cells, based on the measurement of fluorescence intensities IYFP, IFRET, and ICFP by an epifluorescence microscope configured with three filter set combinations. In this work, we used filter sets from Chroma® that yielded the YFP (excitation filter at λex = 500 nm, emission filter at λem = 535 nm), FRET (λex = 430 nm, λem = 535 nm), and CFP (λex = 430 nm, λem = 470 nm) images. The baseline fluorescence detected in the FRET image that is not the result of FRET is quantified by the spillover factors Sd and Sd, measured in two separate experiments where YFP and CFP are expressed individually. The Sd factor quantifies the cross-talk between donor and acceptor emission spectra in the filter sets, and the Sa factor quantifies the direct excitation of the acceptor. In an experiment in which YFP and CFP are co-expressed and energy transfer is measured, FRETR measures the fold-increase in the intensities in the FRET image relative to a computed and expected baseline.

|

where Stot = Sd · ICFP+Sa · IYFP.

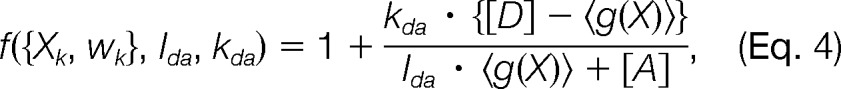

Bayesian Model of FRETR Data

The Bayesian approach (3, 4) estimates the probability of a model given information available about the system, including prior knowledge and newly acquired experimental data. In the multi-state modeling of FRETR data, the model M consists of a set of N modeled structures X = {Xk}, their relative populations in the sample {wk}, and additional parameters defined below. The posterior probability p(M|D, I) of model M, given data D and prior information I, is

where the likelihood function p(D|M, I) is the probability of observing data D given M and I, and the prior p(M|I) is the probability of model M given I. To define the likelihood function, one needs a forward model f(X) that predicts the data point that would have been observed for structure(s) X and a noise model that specifies the distribution of the deviation between the observed and predicted data points. The Bayesian scoring function S(M) is defined as S(M) = −log[p(D|M, I)·p(M|I)] which ranks alternative models the same as the posterior probability.

Forward Model

An ensemble of CFPs and YFPs that are continuously excited by external radiation can return to the ground state through different independent decay pathways, including fluorescence and energy transfer from excited donors to non-excited acceptors. Following Förster theory (13), the rate of energy transfer between donor i and acceptor j is conveniently written as , where Rij is the distance between the two fluorophores and R0 is the Förster radius. The donor fluorescence quantum yield Qd is the ratio between the fluorescence rate kFd and the total rate of decay and is proportional to the donor brightness. In general, R0 depends on the orientation factor κ2 of the interacting dipoles. We adopt the common assumption that donor and acceptor sample their orientations randomly on the time scale of the measurement (30), so that κ2 = 2/3. This is considered particularly valid for fluorescent proteins attached by long, flexible linkers to targeted proteins. The linkers do not adopt a fixed conformation. Finally, the MD simulations described in “Results” showed that the linkers were sufficiently long to allow for orientational averaging during the time of image acquisition.

In the limit of rapid de-excitation and slow excitation rate (SI), the donor and acceptor fluorescence intensities are IdF = Qd · kdX · g(X) and IaF = Qa · {kaX · [A] + kdX · ([D] − g(X))} where quantifies the donor fluorescent intensity in terms of CFP and YFP concentrations and relative proximities. Fi is computed from the Förster expression that relates the rate of energy transfer and distance Rij between the two fluorophores i and j (13): · [D] and [A] are the CFP donor and YFP acceptor concentrations, respectively, and kXd and kXd are their excitation rates. The FRETR forward model (supplemental Fig. S1A) is

|

where Ida is the ratio of CFP and YFP fluorescence in two FRET images when each fluorescent protein is expressed individually at equal levels in separate cells. This quantity is treated as a free parameter, but its value is restrained by the experimental measurement (Idaexp and σIdaexp). kda = kdX,430/kaX,430 is the ratio between donor and acceptor excitation rates at λex = 430 nm; it is determined by the ratio between CFP and YFP absorption cross-sections at 430 nm. However, because each fluorescent protein has a different absorption spectrum and the excitation wavelength varies with the filter set, kda is treated as a free parameter and is inferred along with the coordinates and the other unknown parameters.

Multi-state Forward Model

For FRET measurements of complexes within living cells, the observed FRETR may arise from multiple conformations of the complex. In such a case, FRETR should be expressed in terms of partial contributions resulting from the individual conformations Xk and proportional to their relative populations wk. The single-state forward model (Eq. 3) can be generalized to take into account multiple states.

|

where 〈g(X)〉 = ∑kwkg(Xk).

Photobleaching

YFP fluorophores are photochemically destroyed by prolonged exposure to radiation at wavelengths near the CFP absorption peak. For in vivo measurements, the observed FRETR is thus averaged over multiple copies of the system in which photobleached fluorophores do not contribute to the signal. Thus, the same multi-state forward model described above (Eq. 4) can be used, except that wk corresponds to the proportion of molecules that are both non-photobleached and in state Xk.

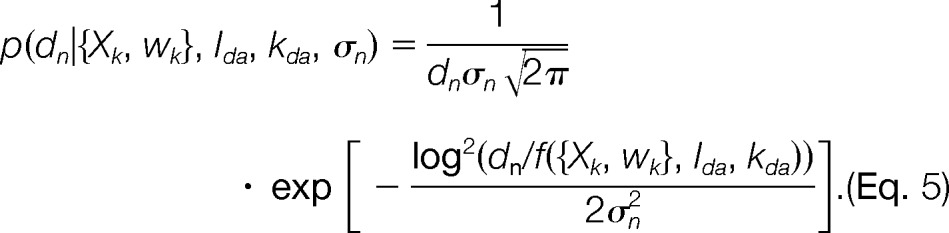

Likelihood Function

The likelihood function p(D|M, I) for dataset D = {dn} of NF independently measured FRETR values is a product of likelihood functions p(dn|{Xk, wk}, Ida, kda, σn) for each data point. Because the observed FRETR values were strictly positive and unbounded, we modeled the uncertainty with a log-normal distribution:

|

To account for varying levels of noise in the data, each data point has an individual uncertainty σn.

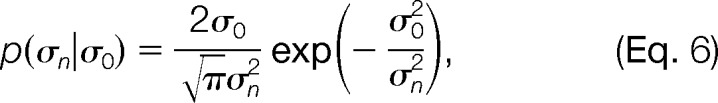

Prior

The prior distribution p(M|I) is a product of priors on the state coordinates Xk, relative populations wk, forward model parameters Ida and kda, and uncertainties σn. The priors on the coordinates p(Xk) include terms to maintain the correct stereochemistry of the system, to avoid steric clashes between components, and to incorporate information other than FRETR data. The priors p(wk) are uniform distributions over the range from 0 to 1, with the constraint ∑k wk = 1. The priors p(σn) are unimodal distributions (31):

|

where σ0 corresponds to an unknown experimental uncertainty; the heavy tail of the distribution allows for outliers (supplemental Fig. S1C). The prior p(σ0) is a uniform distribution over the range from 0.001 to 0.01. If all FRETR values are measured with the same filter sets and fluorescent proteins, the same values of Ida and kda can be used for all data points. The prior p(Ida|Idaexp, σIdaexp) is a normal distribution in which Idaexp and σIdaex are the average and standard error of the experimental measurements. The prior p(kda) is a uniform distribution over the range from 1 to 15, based on typical ratios of CFP to YFP absorption cross-sections (32).

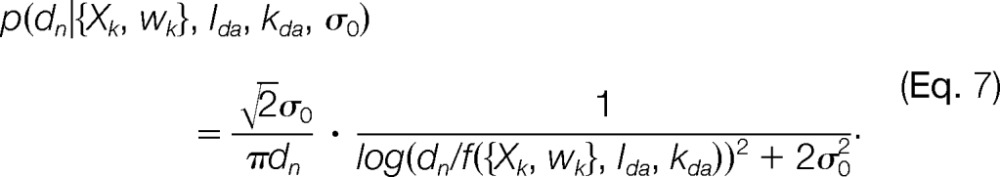

To facilitate sampling of the posterior distribution, we eliminate its dependence on the uncertainties σn by integrating the likelihood function and prior p(σn σ0) with respect to σn. Thus, the marginal likelihood function (supplemental Fig. S1B) is

|

A detailed description is provided in the supplemental material.

Kinetic Monte Carlo

KMC simulations (33, 34) were performed on in silico models of multiple CFP donors and YFP acceptors (one CFP–one YFP, two CFP–one YFP, and one CFP–two YFP). At each KMC step, one of the following reactions was randomly chosen on the basis of their rates: (a) excitation of either a single non-excited YFP (kxa) or (b) CFP (kXd); (c) de-excitation of a single excited YFP by either fluorescence (kFa) or (d) other pathways; or (e) de-excitation of a single excited CFP by fluorescence (kFd), (f) energy transfer to a non-excited YFP (kETij), or (g) other pathways. The rate of decay via pathways other than fluorescence was defined by the CFP and YFP quantum yields of fluorescence Qd and Qa, which were both set at 0.5. The factor kETij was equal to where the Förster radius R0 was set at 4.9 nm. kFd and kFa were set (35) at 0.4 ns−1. Simulations were run for multiple values of kdX,430 and kaX,430, and kaX,500 was calculated from supplemental Eq. S1. The distance between CFP and YFP was varied between 3 and 10 nm in steps of 0.5 nm. For each choice of the parameters, FRETR was calculated from Eq. 1 based on the results of three 0.1-s KMC runs used to simulate imaging experiments with 0.1-s exposures. The intensities in the CFP, FRET, and YFP images were calculated from the number of reactions of a given type occurring during the simulations. Based on experimental measurements, Sd and Sa were set at 0.831 and 0.249, respectively. To account for photobleaching, YFPs were randomly labeled as inactive during the acquisition of the CFP image (with the probability set at 0.3) and then removed from the list of possible reactions. FRETR was thus calculated by averaging quantities over 3200 independent KMC simulations.

Molecular Dynamics

MD simulations were performed with GROMACS4 (36) and PLUMED (37, 38), using the AMBER99SB-ILDN (39) all-atom force field. An implicit solvent based on the Generalized Born formalism combined with the Still method (40) for calculating the Born radii was used. Temperature was controlled by the Bussi–Donadio–Parrinello (41) thermostat. A cutoff of 1.5 nm was used for electrostatic and Lennard–Jones interactions. The parallel tempering algorithm (42) was used to accelerate sampling.

Parallel Tempering Simulation of GFP and Linker

The crystal structure of recombinant wild-type green fluorescent protein (PDB code 1GFL (43)) was used as a template. Modeler 9v8 (44) was used to model the C-terminal residues (HGMDELYKGA) present in the GFP sequence, but not in the crystal structure, and the GlyAla motif at the N terminus. The first 7 and the last 14 residues were treated as flexible segments based on the fluctuations observed in a preliminary MD run. The positions of the other heavy atoms of the protein were restrained by a harmonic potential, with the spring constant equal to 9 × 103 kJ · mol−1 · nm−2. 32 replicas were distributed over a temperature range from 300 to 500 K. Simulations were carried out for an aggregate time of 1 μs.

Combined Parallel Tempering and Metadynamics Simulations of Polyprolines

The polyproline constructs YFP–(PRO)n–CFP with n = (0, 5, 10, 15, 20) were simulated through a combination of parallel tempering and metadynamics (45–47). 16 to 40 replicas were used to span a temperature range from 300 to 600 K. A collective variable measuring the number of prolines in cis and trans conformations was used to accelerate proline cis–trans isomerization. For an n-mer peptide, this collective variable was defined (48) as Ω = ∑i=1n−1 cosωi where the torsional angle ω formed by the quadruplet Cα–C–N–Cα was equal to 0° for the cis isomer and to 180° for the trans isomer. The well-tempered (49) variant of metadynamics was used, with a bias factor equal to 30 and an initial deposition rate of 1 kJ · mol−1 · ps−1. YFPs and CFPs were not simulated at atomistic resolution; only the residues belonging to the flexible N- and C-terminal fragments defined in the previous paragraph were explicitly modeled. The fluorescent proteins were instead represented as virtual atoms defined in the fixed reference frame of the first and last modeled residues. Restraints on all distances between virtual and other atoms were used to enforce steric repulsion. A reweighting algorithm (50) was applied to obtain the unbiased distribution of distances between the two virtual atoms representing the center of the fluorophores. Simulations were carried out for an aggregate time ranging from 1 to 8 μs.

Parallel Tempering Simulations of Other Proteins

The NMR structures of the THP12-carrier protein from yellow meal worm (PDB code 1C3Y (51)) and the fourth LIM domain of PINCH protein (PDB code 1NYP (52)), as well as the crystal structures of the human TBP-associated factor hTAF(II)28/hTAF(II)18 heterodimer (here abbreviated as TAF28-TAF18) (PDB code 1BH8 (53)) and the ferrodoxin:thioredoxin reductase (PDB code 1DJ7 (54)), were used as templates. Modeler was used to model the flexible linkers at the N and C termini. Preliminary short MD simulations at 300 K were carried out to measure the fluctuations in terms of distance-root-mean-square (dRMS) deviation from the native state. A restraint on the dRMS was then used during the parallel tempering simulations to avoid unfolding at high temperatures. The terminal flexible residues were not considered in the dRMS calculation. Multiple replicas (from 16 to 64) were used to span a temperature range from 300 to 600 K. YFPs and CFPs were not simulated explicitly (see previous paragraph).

Benchmark

The benchmark was carried out with the open-source IMP (5, 6), version develop-c47408c. The benchmark results and scripts are available online. The method was tested on 11 ternary and 5 quaternary complexes of known structure, selected from 3D Complex (55). For each pair of subunits in the complex, simulated data were generated for all combinations of the N and C termini of the pair, corresponding to 12 and 24 data points for ternary and quaternary complexes, respectively. Low- and high-noise datasets were generated by setting σ0 equal to 0.001 and 0.01, respectively. The average of 50 different random extractions from the marginal likelihood distribution (Eq. 7) was used to simulate the average from repeated experiments, with the typical standard deviation equal to 0.04 and 0.19 for low- and high-noise data, respectively. The typical standard deviation for in vivo data is 0.15. Different percentages (100% and 50%) of the total amount of data were used to assess the role of data sparseness in modeling accuracy. To model linker flexibility, a Gaussian mixture model was fit on a set of 5000 probes of radius equal to 10 Å using 10 Gaussian components. The conformation of each subunit was obtained from the crystal structure of the entire complex; it was represented with Cα atoms for each residue and treated as an independent rigid body. An excluded volume potential was used to avoid steric clashes between subunits. Coordinates, forward model, and likelihood parameters were sampled via a Gibbs sampling scheme combined with a simulated annealing Monte Carlo algorithm. A Monte Carlo move of each rigid subunit consisted of a random rotation and translation of at most 17° and 1.0 Å, respectively. A Monte Carlo move of the forward model parameters kda, Ida, and σ0 consisted of a random perturbation of at most 0.3, 0.3, and 0.001, respectively. Temperature was varied between 1.0 and 5.0 kBT. The initial positions were randomized in a cubic box with dimensions of 100 Å. For each structure and choice of parameters, 20 independent simulated annealing Monte Carlo runs were performed. A total of 2560 tests were conducted, each for a total of 3 × 107 simulated annealing Monte Carlo steps (supplemental Fig. S9).

In Vivo FRETR Measurements

Saccharomyces cerevisiae strains expressing the YFP and CFP tagged proteins were grown and imaged as previously described (25). The fluorescent proteins were linked to the target proteins through unstructured linkers. Exposure times were either 0.08 or 0.1 s for each image, allowing for a prolonged sampling of an ensemble of proteins such that each can adopt different relative orientations of the fluorescent proteins. Expression of all constructs was driven by the strong TEF promoter. Importantly, all constructs were engineered with a nuclear localization signal, resulting in two advantages. First, the uniform nuclear fluorescence was used as an indication of proper protein folding, and second, nuclear localization allowed the cytoplasm to be used to measure a local background in the cell. All constructs were integrated into the host genome to ensure uniform cell-to-cell gene expression. Plasmids used for integrating the constructs are described in supplemental Table S1.

Image analysis was performed with FRETSCAL, an integrated collection of MATLAB scripts with a graphical user interface. FRETSCAL identifies an area of interest (AOI) within the images and calculates FRETR for each AOI. FRETSCAL has user-controlled selection criteria that (i) define the size of the AOI, (ii) set a maximum pixel intensity of the AOI to ensure that selected AOIs are within the linear range of the image acquisition CCD camera, (iii) set a minimum signal-to-background ratio, (iv) set a maximum cutoff value for the width of a Gaussian fit of the intensity values within the AOI, and (v) define other parameters that automate AOI selection and analysis. The software is open source and is available online at the MATLAB Central website.

A single value of FRETR is calculated as a ratio of the mean background subtracted value of the whole nuclear region in the FRET image divided by the projected value if there was no energy transfer. The projected value is calculated from the corresponding nuclei in the YFP and CFP images of the same field. The projected value is the sum of the mean background subtracted value of the whole nuclear region in the YFP image multiplied by the YFP spillover factor plus the mean background subtracted value of the whole nuclear region in the CFP image multiplied by the CFP spillover factor. The spillover factors are determined as described above under the FRETR heading.

All images used in this study are available online from the YRC Public Image Repository. In addition, a composite image is shown that displays the FRETSCAL output. In the online composite image, the nuclei that satisfied the selection criteria used in FRETSCAL are framed in yellow. The corresponding background pixels are shown in gray.

RESULTS

Our Bayesian approach for determining a macromolecular architecture from in vivo FRET data is based on a microscopic interpretation (forward model) of the experimental observable FRETR in terms of structural models and other parameters. It is thus crucial to first assess the validity of the forward model. To do so, we began with computational validation by means of KMC simulations (33, 34) of in silico models of multiple CFP donors and YFP acceptors. We then proceeded with comparisons of FRETR predictions from molecular dynamics simulations to in vivo experimental data that were collected from yeast cells expressing constructs of CFP and YFP separated by any one of nine defined linkers and protein structures. Finally, the accuracy of structural modeling using synthetic FRETR data and the structures of each individual subunit was assessed via comparison of native molecular architectures of 16 protein complexes with their models computed with our Bayesian approach.

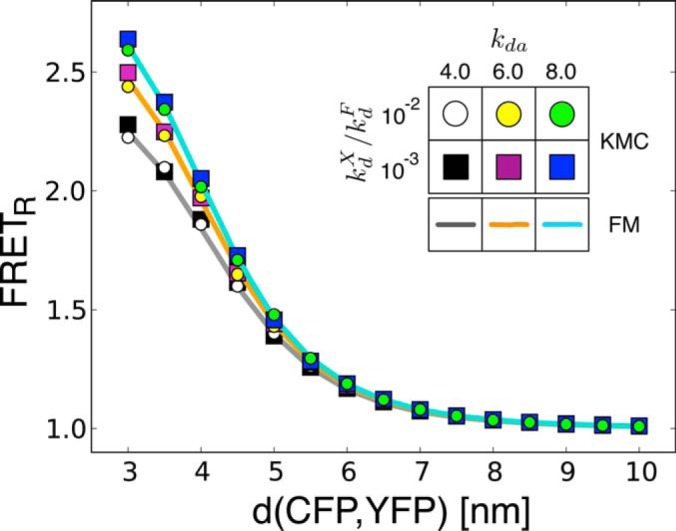

Kinetic Monte Carlo Validation of the Forward Model

Based on the physics of fluorescent molecules, we derived master equations that express the excitation and emission of an ensemble of FRET donors and acceptors as visualized with a fluorescent microscope (supplemental Eqs. S2A and S2B). The FRETR forward model (Eq. 4) is derived from an approximate solution of these master equations in the limit of rapid de-excitation and slow excitation rate. As a validation of this approximation, the value of the FRETR predicted by Eq. 4 was compared with the results of KMC simulations governed by the master equations S2A and S2B. The KMC simulations described the evolution of an in silico model of multiple CFP donors and YFP acceptors and computed FRETR in every excitation/de-excitation regime. For this comparison, we represented CFP and YFP as dimensionless points whose distance and other parameters were varied (“Computational Methods and Experimental Procedures”).

FRETR changed smoothly with the distance between a single CFP and YFP over the range from 3 to 10 nm (Fig. 2). When the CFP excitation rate kXd was much smaller than its fluorescent rate kFd (kXd/kFD < 0.05), excellent agreement was found between FRETR from the forward model and KMC simulations, with deviations of less than 1% under all conditions (supplemental Fig. S2A).

Fig. 2.

KMC validation of the forward model. FRETR was calculated from KMC simulations of a system consisting of one CFP donor and one YFP acceptor. CFP and YFP were represented as dimensionless points that correspond to the centers of the fluorophore. FRETR was computed with varying distance between fluorophores, donor excitation rate kdX/kdF, and donor/acceptor excitation rate ratio kda = kdX,430/kaX,430 (circles and squares). kdF was set (35) at 0.4 nm−1. The YFP photobleaching ratio during the acquisition of the CFP image was set at 0.3. In the regime of low excitation and fast de-excitation (kdX/kdF < 0.05), the value of FRETR predicted by the forward model (lines) was in excellent agreement with KMC simulations (error analysis in supplemental Fig. S2).

FRETR was also computed from KMC simulations of systems of two CFPs and one YFP (supplemental Fig. S3A) and of one CFP and two YFPs (supplemental Fig. S3B). The behavior of FRETR differs in the two cases. When multiple donors surround a single acceptor, adjacent donors compete for non-excited acceptors. In contrast, a relative abundance of acceptors increases the chance of energy transfer. However, the effect on energy transfer is shaped by the relative rates of excitation and emission of the donor and acceptor (supplemental Fig. S3C). In the limit of rapid de-excitation and slow excitation rate, the agreement between the forward model and KMC simulations was still excellent in both cases, with deviations of less than 1% under all conditions (supplemental Figs. S2B and S2C).

In all the KMC simulations mentioned above, we included the effect on YFP photobleaching during the experiment. To examine this effect directly, we investigated a model system of multiple YFP acceptors. As expected, with fewer acceptors available because of photobleaching, energy transfer was attenuated at all CFP–YFP distances (compare value in supplemental Fig. S4A with that in supplemental Fig. S4B); again, the FRETR computed by the forward model, which included the effect of YFP photobleaching (supplemental Fig. S4C), agreed with that from the KMC simulations that included photobleaching (supplemental Fig. S4B).

These comparisons demonstrate that the approximate expression for FRETR given by the forward model (Eq. 4) agrees well with more complex (and far more computationally expensive) simulations based on a more comprehensive physical treatment.

In Vivo Experimental Validation of the Forward Model

We further validated the FRETR forward model by comparing the predictions from MD simulations to in vivo experimental data that we collected on nine proteins of known structure that were expressed in S. cerevisiae (supplemental Table S1). These nine systems included a tandem YFP–CFP; YFP–[Pro]n–CFP in which n was equal to 5, 10, 15, or 20 prolines; and four constructs in which CFP and YFP were attached to the N or C termini of proteins of known structure. The latter four constructs were as follows: (i) YFP-THP12-CFP; (ii) YFP-Lim4-CFP; (iii) YFP -TAF28-CFP co-expressed with TAF18; and (iv) FTR117-CFP co-expressed with FTR74-YFP. Finally, a control measurement on the co-expressed but unlinked YFP and CFP pair showed no energy transfer (FRETR = 1.04). In each case hundreds of images of hundreds of cells were acquired. A sample set of images is shown in Fig. 3A. All the images used in the dataset are available online at the YRC Public Image Repository. Automated processing of the images was accomplished with the software FRETSCAL. The large number (n ≥ 200) of identified AOIs provided a strong statistical foundation for the FRETR measurements used in the Bayesian analysis.

Fig. 3.

Experimental validation of the forward model. FRETR values were determined for nine proteins of known structure. The proteins were stably expressed in S. cerevisiae with nuclear localization signals (see “Computational Methods and Experimental Procedures”). A, a sample of captured images. A 4× enlargement of one region shows the FRETR values determined by FRETSCAL. B, FRETR values measured in vivo on nine proteins of known structure (black bars) compared with the values predicted by the forward model (white bars). The Bayesian parameters were inferred by maximizing the posterior probability on the set of nine measurements. The fit was repeated excluding the outlier data point (TAF28-TAF18) and yielded similar results (gray bars), demonstrating the ability of the Bayesian approach to tolerate outliers. Red error bars indicate experimental standard error and inferred uncertainty.

In comparing our forward model against experimental data, we took into account the dependence of the measured FRETR on the presence of multiple conformations in the sample. To do so, we used MD simulations combined with advanced sampling techniques to explore the conformational landscape of the test structures. Although polyproline peptides have often been employed as a spectroscopic ruler, several experimental (56–58) and computational (48, 57) studies have questioned the role of polyproline as a “rigid rod” in a single dominant conformation. Prolyl isomerization from the trans to cis isomer, whose activation energy is on the order of 10 to 20 kcal/mol (59, 60), converts the left-handed polyproline II helix (PPII) to the more compact right-handed polyproline I helix (PPI). Thus, a heterogeneous population of structures with distinct patterns of cis and trans isomers of proline is expected to be present in a cell.

The conformational landscape of polyprolines in solution was predicted by all-atom MD simulations in implicit solvent using parallel tempering (42) and metadynamics (45, 46). These techniques allow (i) exhaustive sampling by accelerating proline trans-cis isomerization and (ii) estimates of the equilibrium relative populations {wk} of the conformers (Eq. 4). The polyproline II helix was favored over the polyproline I helix across all lengths studied (supplemental Fig. S5), in agreement with previous computational (48) and experimental results (61). The conformational landscape of the other constructs was also explored using similar computational approaches. Finally, simulations of the tandem YFP–CFP showed that the linkers at the N and C termini were sufficiently long to allow for orientational averaging of the fluorophores on the time scale of the FRET experiment (supplemental Fig. S6).

To compare the FRETR forward model with experimental data, we calculated the weighted average of g(X), which depends on the model coordinates (Eq. 4), as the ensemble average over the MD conformations (supplemental Figs. S7A and S7B). We inferred the forward model parameters kda and Ida, along with the uncertainty σ0, by maximizing the posterior distribution, which was defined based on all nine data points using the mean experimental value kexpda = 6.0 and standard error σIexpda = 2.0. Using the inferred parameters (kda = 7.7, Ida = 6.6, and σ0 = 0.05), we found good agreement between the forward model and measured FRETR values (Fig. 3B, white and black bars, respectively), except for one outlier, TAF28-TAF18. When the procedure was repeated without the outlier (Fig. 3B, gray bars), the inferred parameter values kda = 7.5 and Ida = 6.2 changed minimally, and the data uncertainty σ0 dropped from 0.05 to 0.03, as expected upon removal of an outlier data point. Thus, the forward model and associated parameters can effectively account for the influence of components of wide-field fluorescence microscopy, such as installed filter sets and illumination intensity, on the measurement of the efficiency of fluorescence energy transfer. The FRETR forward model can accurately relate FRETR values and fluorophore distances.

Finally, to improve the computational efficiency of the forward model, we fit an efficient Gaussian mixture model to the expensive all-atom MD simulations of the linker (SI), without a significant decrease in the accuracy of the forward model (supplemental Fig. S8).

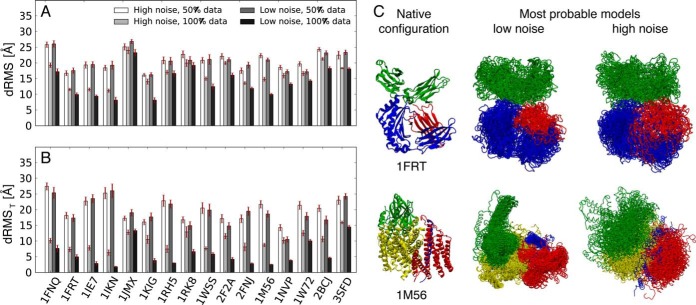

Benchmark of Modeling Accuracy

The accuracy of the molecular architectures modeled based on synthetic FRETR data, given the knowledge of the structure of each subunit, was mapped with the aid of known structures for 16 protein complexes of three and four subunits (55). For this benchmark, we used synthetic FRETR data that were computed by first applying our FRETR forward model (Eq. 4) to all pairs of N and C termini of each subunit in the native structures and then adding noise (Eq. 7). The accuracy was defined as the Cα dRMS deviation between the native structure and the most probable model found by the sampling algorithm in IMP, averaged on 20 independent runs. The use of synthetic data in this benchmark allowed us to map the accuracy of structural modeling from FRETR data as a function of the level of data noise and sparseness, with (supplemental Table S2) and without (supplemental Table S3) taking the linker flexibility into account. A flowchart explaining the different steps of the benchmark is presented in supplemental Fig. S9. It is conceivable, however, that the accuracy of models computed from real FRETR data might be worse than that from the simulated data, despite our effort to include noise in the simulated data. Real FRETR data for the FTR117-FTR74 case were not used as a benchmark case, because the flexibility and the resulting demand on sampling made it difficult to run the benchmark a very large number of times.

When 100% of the data points were used, the accuracy of the predicted structure of the complex was 13.9 Å and 14.8 Å for ternary and quaternary complexes, respectively. This accuracy was marginally reduced to 16.1 Å and 17.4 Å when noisy data were used. The weak dependence on the noise level resulted from the small standard error of FRETR obtained by averaging FRETR over many (∼100) independent experiments. In contrast, the accuracy was strongly dependent on data sparseness. When only 50% of the data points were used, the accuracy decreased to a range from 20.4 Å to 21.5 Å, depending on the number of subunits and the noise level. This result emphasizes the need to compile as much information as possible from in vivo measurements.

Because FRETR data provide information about the distance between the protein termini, we expected much greater accuracy in determining the positions of the terminal residues (dRMST in supplemental Tables S2 and S3). Indeed, the accuracy was 5.2 Å to 9.3 Å for ternary complexes and 7.1 Å to 11.6 Å for quaternary complexes, depending on the noise level.

Finally, the accuracy was also affected by the linker flexibility (supplemental Table S3). In particular, the positions of the tagged termini were inferred with greater accuracy (〈ΔdRMST〉 = 2.2 Å) when the simulated data were created and the sampling was performed without the linker flexibility. However, the inclusion of the linker flexibility had a relatively small effect on the accuracy (〈ΔdRMS〉 = 1.1 Å). Thus, the presence of a flexible linker, while allowing orientational averaging of the fluorophores (supplemental Fig. S6), does not dramatically affect the accuracy of our approach.

DISCUSSION

Many observables have been introduced to quantify in vivo FRET (23). Fluorescence lifetime microscopy overcomes many of the problems associated with epifluorescence microscopy, but it is technically challenging and applicable only for complexes with a robust fluorescence signal (21, 22, 62–65). Many FRET indexes have successfully processed steady-state epifluorescence images to yield significant insights into the dynamics of protein associations in live cells (22, 23, 66). However, this work represents the first case in which the supporting theory and structural predictions from a FRET metric have been modeled and tested both in silico, with molecular dynamic simulations, and in vivo, with benchmark protein complexes.

Although our Bayesian approach could be adapted to incorporate other FRET metrics, or even FRET efficiencies derived from fluorescence lifetime microscopy, we chose the metric FRETR. To our knowledge this is the only live-cell FRET metric in which structural arrangements predicted from in vivo measurements were directly confirmed in vitro by means of single particle analysis. FRETR measurements of the γ-tubulin complex in yeast predicted the location of the N and C termini of two proteins, Spc97 and Spc98, in the complex (25). Fluorescent proteins linked to these ends were later directly visualized at the predicted locations via electron microscopy (67). FRETR has also been used to analyze the structure of the yeast spindle pole body (24, 68) and cohesion architecture (69), and more recently the organization of the yeast kinetochore (26). Of course FRETR also has limitations, and it is most appropriate for experimental conditions in which the proteins in a complex are uniformly tagged with a fluorescent protein, gene expression is tightly regulated and typically driven from native promoters, and free unincorporated proteins do not interfere with the FRET measurements (17, 23–25). We showed that our FRETR forward model is accurate, first by comparing the predicted value (Eq. 4) with that computed from KMC simulations of an in silico model of multiple CFP donors and YFP acceptors. Excellent agreement was found for typical conditions of fluorescence microscopy,3 where CFPs and YFPs were not saturated by the incident illumination. In addition, KMC simulations on systems of multiple donors and acceptors (supplemental Fig. S3) illustrated the expected asymmetry of the one CFP–two YFP and two CFP–one YFP experiments and suggested that data from experiments in which the positions of YFP and CFP are swapped provide independent and thus useful information and should not be averaged (24).

We also validated the forward model using experimental data by comparing predicted FRETR to in vivo data collected on nine proteins of known structure, including fluorescent proteins separated by polyproline peptides of different lengths (Fig. 3B). Accurate modeling of the experimental data required explicit modeling of multiple conformations in the sample (supplemental Figs. S5 and S7). Although in this study the relative populations {wk} were predetermined by MD simulations, in general they can be inferred along with the coordinates of the system and other parameters using multi-state Bayesian scoring functions (27–29).

We demonstrated that the Bayesian approach is robust with respect to the presence of outlier data points. Collecting FRETR data in living cells requires tagging a complex with CFP–YFP pairs that might perturb the system and affect its structure. As a result, a data point might not correctly represent the native structure of the complex and thus might be inconsistent with other information, including other FRETR measurements. For example, the FRETR value predicted for TAF28-TAF18 was significantly different from the observed one (Fig. 3B). This discrepancy might arise from several other factors besides structural changes due to the insertion of the fluorophores, such as non-converged MD simulations and inaccuracy of the molecular mechanics force field. Importantly, for each data point, an uncertainty parameter is either inferred or marginalized (31), allowing those points that are not consistent with the bulk of the data to be properly down-weighted in the construction of the model.

The results of the benchmark (Fig. 4 and supplemental Table S2) indicated the importance of using multiple data points to model a structure. Synthetic FRETR data between all pairs of subunit N and C termini determined the structure of ternary and quaternary complexes with an accuracy of ∼15 Å (Cα dRMS), whereas using only 50% of the data decreased the accuracy to ∼20 Å. The greatest structural uncertainty is in the orientation between the subunits. The accuracy can thus be improved if further data are collected. Typically, only the protein termini of each subunit are tagged with GFP; the total number of FRETR data points per complex that can be used in structural modeling is thus N(2N − 1), where N is the number of subunits of the complex. However, in principle fluorescent proteins can be inserted at positions other than the protein termini, although such insertions might be more likely to alter the structure of the complex.

Fig. 4.

Benchmark of a set of complexes modeled using simulated FRETR data. A, B, accuracy of the modeled structures as a function of data sparseness and level of noise. Accuracy was quantified using the average Cα dRMS deviation between the crystallographic structure and the 20 most probable models, each one from an independent run, calculated on the entire complex (A) and on the N- and C-terminal residues (B); red error bars indicate standard error of the mean. C, most probable models of the complex of rat neonatal Fc receptor with Fc (PDB code 1FRT (73)) and of cytochrome c oxidase from Rhodobacter sphaeroides (PDB code 1M56 (27)), with low- and high-noise datasets, and with all pairwise FRETR indices.

Like any search-based approach, our method requires a sufficiently thorough configurational sampling algorithm. Here, we used advanced sampling techniques, including Gibbs sampler MC with simulated annealing (70) and MD combined with parallel tempering and metadynamics (47). We explicitly assessed whether sampling was sufficiently thorough by demonstrating the convergence of the model as a function of the number of sampled models (supplemental Fig. S7).

Compared with other methods that mostly deal with in vitro FRET data (15, 16), our approach treats all noise sources that characterize measurements in living cells, accounts for sample heterogeneity, and is robust to outlier data points. Furthermore, our approach is more general, because it allows the use of in vivo data collected in both bulk experiments, where multiple CFP and YFP contribute to the measured FRETR, and single-molecule experiments (71), in which a single CFP–YFP pair is present; in the latter application, the observed FRETR is not the ratio of average intensities in the different images (Eq. 4), but the average of FRETR measured on samples in which the YFP is either active or photobleached.

Finally, we implemented our method in IMP, an open-source platform for integrative structural modeling of macromolecular systems (5). Through IMP, FRETR data can be combined with information obtained via other methods, such as electron microscopy, chemical and cysteine cross-linking, small angle x-ray scattering, proteomics, and other theoretical or statistical analyses, in an integrative or hybrid approach (5, 72). The uncertainty in the orientation of the subunits based on FRETR data alone could thus be resolved by considering additional complementary data, even if sparse and noisy. The Bayesian approach is expected to be even more useful in integrative modeling than modeling based on FRETR data alone, because data from different experiments can in principle be properly weighted and thus seamlessly integrated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to David Sivak and Charles Asbury for commenting on the manuscript and to Ben Webb for help in setting up the benchmark. We also thank Peter Schurmann for the clone of FTR, Peter L. Davies for the clone of THP12, Christophe Romier for the hTAF clones, and Jun Qin for the clone of the Lim4.

Footnotes

Author contributions: M.B., T.N.D., E.G.M., and A.S. designed research; M.B. and E.G.M. performed research; M.B., B.A.S., M.R., D.J., R.R., and E.G.M. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; M.B., R.P., S.K., D.R., and E.G.M. analyzed data; M.B., T.N.D., E.G.M., and A.S. wrote the paper.

* This work was funded by NIH Grant Nos. R01 GM083960 (A.S.), U54 RR022220 (A.S.), and P41 GM103533 (E.M. and T.D.) and was supported by SNSF through Grant Nos. PBZHP3-133388 and PA00P3_139727 (R.P.).

This article contains supplemental material.

This article contains supplemental material.

2 Bonomi, M., Pellarin, R., Spill, Y., Nilges, M., DeGrado, W., and Sali, A., in preparation.

3 For example, when collecting data for the yeast spindle pole body, 1.5 mW of light from the source illuminates the sample, corresponding to a photon per fluorophore every ∼50 ns. The excitation rate is of course smaller than implied by this photon flux (kdX/kdF < 0.05), because the YFP and CFP absorption cross-sections are typically much smaller than the fluorophore area.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- FRET

- Förster resonance energy transfer

- FRETR

- index of relative FRET in cells

- IMP

- Integrative Modeling Platform

- dRMS

- distance-root-mean-square

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- CFP

- cyan fluorescent protein

- YFP

- yellow fluorescent protein

- KMC

- kinetic Monte Carlo

- MD

- Molecular Dynamics

- AOI

- area of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sali A., Glaeser R., Earnest T., Baumeister W. (2003) From words to literature in structural proteomics. Nature 422, 216–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Alber F., Dokudovskaya S., Veenhoff L., Zhang W., Kipper J., Devos D., Suprapto A., Karni-Schmidt O., Williams R., Chait B., Rout M., Sali A. (2007) Determining the architectures of macromolecular assemblies. Nature 450, 683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rieping W., Habeck M., Nilges M. (2005) Inferential structure determination. Science 309, 303–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Habeck M., Nilges M., Rieping W. (2005) Bayesian inference applied to macromolecular structure determination. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 72, 031912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Russel D., Lasker K., Webb B., Velazquez-Muriel J., Tjioe E., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Peterson B., Sali A. (2012) Putting the pieces together: integrative modeling platform software for structure determination of macromolecular assemblies. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alber F., Forster F., Korkin D., Topf M., Sali A. (2008) Integrating diverse data for structure determination of macromolecular assemblies. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 77, 443–477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bau D., Sanyal A., Lajoie B. R., Capriotti E., Byron M., Lawrence J. B., Dekker J., Marti-Renom M. A. (2011) The three-dimensional folding of the alpha-globin gene domain reveals formation of chromatin globules. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 107–114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Lasker K., Forster F., Bohn S., Walzthoeni T., Villa E., Unverdorben P., Beck F., Aebersold R., Sali A., Baumeister W. (2012) Molecular architecture of the 26S proteasome holocomplex determined by an integrative approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 1380–1387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Velazquez-Muriel J., Lasker K., Russel D., Phillips J., Webb B. M., Schneidman-Duhovny D., Sali A. (2012) Assembly of macromolecular complexes by satisfaction of spatial restraints from electron microscopy images. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 18821–18826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fernandez-Martinez J., Phillips J., Sekedat M. D., Diaz-Avalos R., Velazquez-Muriel J., Franke J. D., Williams R., Stokes D. L., Chait B. T., Sali A., Rout M. P. (2012) Structure-function mapping of a heptameric module in the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 196, 419–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Selvin P. R. (2000) The renaissance of fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 730–734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jares-Erijman E. A., Jovin T. M. (2003) Fret imaging. Nat. Biotechnol. 21, 1387–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Förster T. (1948) Zwischenmolekulare Energiewanderung und Fluoreszenz. Intermolecular energy transfer and fluorescence Annalen der Physik 437, 55–75 [Google Scholar]

- 14. Roy R., Hohng S., Ha T. (2008) A practical guide to single-molecule FRET. Nat. Methods 5, 507–516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Brunger A. T., Strop P., Vrljic M., Chu S., Weninger K. R. (2011) Three-dimensional molecular modeling with single molecule FRET. J. Struct. Biol. 173, 497–505 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kalinin S., Peulen T., Sindbert S., Rothwell P. J., Berger S., Restle T., Goody R. S., Gohlke H., Seidel C. A. (2012) A toolkit and benchmark study for FRET-restrained high-precision structural modeling. Nat. Methods 9, 1218–1225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Piston D. W., Kremers G. J. (2007) Fluorescent protein FRET: the good, the bad and the ugly. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giepmans B. N., Adams S. R., Ellisman M. H., Tsien R. Y. (2006) The fluorescent toolbox for assessing protein location and function. Science 312, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lam A. J., St-Pierre F., Gong Y., Marshall J. D., Cranfill P. J., Baird M. A., McKeown M. R., Wiedenmann J., Davidson M. W., Schnitzer M. J., Tsien R. Y., Lin M. Z. (2012) Improving FRET dynamic range with bright green and red fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods 9, 1005–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kremers G. J., Gilbert S. G., Cranfill P. J., Davidson M. W., Piston D. W. (2011) Fluorescent proteins at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 124, 157–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Becker W. (2012) Fluorescence lifetime imaging—techniques and applications. J. Microsc. 247, 119–136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Zeug A., Woehler A., Neher E., Ponimaskin E. G. (2012) Quantitative intensity-based FRET approaches—a comparative snapshot. Biophys. J. 103, 1821–1827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Berney C., Danuser G. (2003) FRET or no FRET: a quantitative comparison. Biophys. J. 84, 3992–4010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Muller E. G., Snydsman B. E., Novik I., Hailey D. W., Gestaut D. R., Niemann C. A., O'Toole E. T., Giddings T. H., Jr., Sundin B. A., Davis T. N. (2005) The organization of the core proteins of the yeast spindle pole body. Mol. Biol. Cell 16, 3341–3352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kollman J. M., Zelter A., Muller E. G., Fox B., Rice L. M., Davis T. N., Agard D. A. (2008) The structure of the gamma-tubulin small complex: implications of its architecture and flexibility for microtubule nucleation. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 207–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Aravamudhan P., Felzer-Kim I., Gurunathan K., Joglekar A. P. (2014) Assembling the protein architecture of the budding yeast kinetochore-microtubule attachment using FRET. Curr. Biol. 24, 1437–1446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Svensson-Ek M., Abramson J., Larsson G., Tornroth S., Brzezinski P., Iwata S. (2002) The X-ray crystal structures of wild-type and EQ(I-286) mutant cytochrome c oxidases from Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Mol. Biol. 321, 329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Street T. O., Zeng X., Pellarin R., Bonomi M., Sali A., Kelly M. J., Chu F., Agard D. A. (2014) Elucidating the mechanism of substrate recognition by the bacterial Hsp90 molecular chaperone. J. Mol. Biol. 426, 2393–2404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Molnar K. S., Bonomi M., Pellarin R., Clinthorne G. D., Gonzalez G., Goldberg S. D., Goulian M., Sali A., DeGrado W. (2014) Cys-scanning disulfide crosslinking and Bayesian modeling probe the transmembrane signaling mechanism of the histidine kinase, PhoQ. Structure, 22, 1239–1251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stryer L. (1978) Fluorescence energy-transfer as a spectroscopic ruler. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 47, 819–846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sivia D. S., Skilling J. (2006) Data Analysis: A Bayesian Tutorial, 2nd ed., Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strohhofer C., Forster T., Chorvat D., Kasak P., Lacik I., Koukaki M., Karamanou S., Economou A. (2011) Quantitative analysis of energy transfer between fluorescent proteins in CFP-GBP-YFP and its response to Ca2+. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 17852–17863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bortz A. B., Kalos M. H., Lebowitz J. L. (1975) New algorithm for Monte-Carlo simulation of Ising spin systems. J. Comput. Phys. 17, 10–18 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Young W. M., Elcock E. W. (1966) Monte Carlo studies of vacancy migration in binary ordered alloys—I. P. Phys. Soc. Lond. 89, 735 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kremers G. J., Goedhart J., van Munster E. B., Gadella T. W. J. (2006) Cyan and yellow super fluorescent proteins with improved brightness, protein folding, and FRET Forster radius. Biochemistry 45, 6570–6580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hess B., Kutzner C., van der Spoel D., Lindahl E. (2008) GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Bussi G., Camilloni C., Provasi D., Raiteri P., Donadio D., Marinelli F., Pietrucci F., Broglia R. A., Parrinello M. (2009) PLUMED: a portable plugin for free-energy calculations with molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 180, 1961–1972 [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tribello G. A., Bonomi M., Branduardi D., Camilloni C., Bussi G. (2014) PLUMED 2: new feathers for an old bird. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 604–613 [Google Scholar]

- 39. Lindorff-Larsen K., Piana S., Palmo K., Maragakis P., Klepeis J. L., Dror R. O., Shaw D. E. (2010) Improved side-chain torsion potentials for the Amber ff99SB protein force field. Proteins 78, 1950–1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Qiu D., Shenkin P. S., Hollinger F. P., Still W. C. (1997) The GB/SA continuum model for solvation. A fast analytical method for the calculation of approximate Born radii. J. Phys. Chem. A 101, 3005–3014 [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. (2007) Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126 014101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Sugita Y., Okamoto Y. (1999) Replica-exchange molecular dynamics method for protein folding. Chem. Phys. Lett. 314, 141–151 [Google Scholar]

- 43. Yang F., Moss L. G., Phillips G. N. (1996) The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 1246–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Sali A., Blundell T. L. (1993) Comparative protein modelling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234, 779–815 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Laio A., Parrinello M. (2002) Escaping free-energy minima. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12562–12566 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Barducci A., Bonomi M., Parrinello M. (2011) Metadynamics. Wires Comput. Mol. Sci. 1, 826–843 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bussi G., Gervasio F. L., Laio A., Parrinello M. (2006) Free-energy landscape for beta hairpin folding from combined parallel tempering and metadynamics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 13435–13441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Moradi M., Babin V., Roland C., Darden T. A., Sagui C. (2009) Conformations and free energy landscapes of polyproline peptides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 20746–20751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barducci A., Bussi G., Parrinello M. (2008) Well-tempered metadynamics: a smoothly converging and tunable free-energy method. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100 020603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bonomi M., Barducci A., Parrinello M. (2009) Reconstructing the equilibrium Boltzmann distribution from well-tempered metadynamics. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 1615–1621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rothemund S., Liou Y. C., Davies P. L., Krause E., Sonnichsen F. D. (1999) A new class of hexahelical insect proteins revealed as putative carriers of small hydrophobic ligands. Struct. Fold. Des. 7, 1325–1332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Velyvis A., Vaynberg J., Yang Y. W., Vinogradova O., Zhang Y. J., Wu C. Y., Qin J. (2003) Structural and functional insights into PINCH LIM4 domain-mediated integrin signaling. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 558–564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Birck C., Poch O., Romier C., Ruff M., Mengus G., Lavigne A. C., Davidson I., Moras D. (1998) Human TAF(II)28 and TAF(II)18 interact through a histone fold encoded by atypical evolutionary conserved motifs also found in the SPT3 family. Cell 94, 239–249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Dai S. D., Schwendtmayer C., Schurmann P., Ramaswamy S., Eklund H. (2000) Redox signaling in chloroplasts: cleavage of disulfides by an iron-sulfur cluster. Science 287, 655–658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Levy E. D., Pereira-Leal J. B., Chothia C., Teichmann S. A. (2006) 3D complex: a structural classification of protein complexes. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2, 1395–1406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Schuler B., Lipman E. A., Steinbach P. J., Kumke M., Eaton W. A. (2005) Polyproline and the “spectroscopic ruler” revisited with single-molecule fluorescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 2754–2759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Best R. B., Merchant K. A., Gopich I. V., Schuler B., Bax A., Eaton W. A. (2007) Effect of flexibility and cis residues in single-molecule FRET studies of polyproline. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19064–19066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Doose S., Neuweiler H., Barsch H., Sauer M. (2007) Probing polyproline structure and dynamics by photoinduced electron transfer provides evidence for deviations from a regular polyproline type II helix. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 17400–17405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Fischer S., Dunbrack R. L., Karplus M. (1994) Cis-trans imide isomerization of the proline dipeptide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 116, 11931–11937 [Google Scholar]

- 60. Jhon J. S., Kang Y. K. (1999) Imide cis-trans isomerization of N-acetyl-N′-methylprolineamide and solvent effects. J. Phys. Chem. A 103, 5436–5439 [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kakinoki S., Hirano Y., Oka M. (2005) On the stability of polyproline-I and II structures of proline oligopeptides. Polym. Bull. 53, 109–115 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Sikor M., Mapa K., von Voithenberg L. V., Mokranjac D., Lamb D. C. (2013) Real-time observation of the conformational dynamics of mitochondrial Hsp70 by spFRET. EMBO J. 32, 1639–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Alber F., Chait B. T., Rout M. P., Sali A. (2008) Integrative structure determination of protein assemblies by satisfaction of spatial restraints. In Protein-Protein Interactions and Networks: Identification, Characterization and Prediction (Panchenko A., Przytycka T., Eds), pp. 99–114, Springer-Verlag, London, UK [Google Scholar]

- 64. Visser A. J. W. G., Laptenok S. P., Visser N. V., van Hoek A., Birch D. J. S., Brochon J. C., Borst J. W. (2010) Time-resolved FRET fluorescence spectroscopy of visible fluorescent protein pairs. Eur. Biophys. J. Biophys. 39, 241–253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Raicu V., Singh D. R. (2013) FRET spectrometry: a new tool for the determination of protein quaternary structure in living cells. Biophys. J. 105, 1937–1945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Hoppe A. D., Scott B. L., Welliver T. P., Straight S. W., Swanson J. A. (2013) N-way FRET microscopy of multiple protein-protein interactions in live cells. PLoS One 8 e64760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Choy R. M., Kollman J. M., Zelter A., Davis T. N., Agard D. A. (2009) Localization and orientation of the gamma-tubulin small complex components using protein tags as labels for single particle EM. J. Struct. Biol. 168, 571–574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Mathieson E. M., Suda Y., Nickas M., Snydsman B., Davis T. N., Muller E. G., Neiman A. M. (2010) Vesicle docking to the spindle pole body is necessary to recruit the exocyst during membrane formation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Biol. Cell 21, 3693–3707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. McIntyre J., Muller E. G., Weitzer S., Snydsman B. E., Davis T. N., Uhlmann F. (2007) In vivo analysis of cohesin architecture using FRET in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 26, 3783–3793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Kirkpatrick S., Gelatt C. D., Jr., Vecchi M. P. (1983) Optimization by simulated annealing. Science 220, 671–680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Coelho M., Maghelli N., Tolic-Norrelykke I. M. (2013) Single-molecule imaging in vivo: the dancing building blocks of the cell. Integr. Biol. 5, 748–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Ward A. B., Sali A., Wilson I. A. (2013) Integrative structural biology. Science 339, 913–915 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Burmeister W. P., Huber A. H., Bjorkman P. J. (1994) Crystal-structure of the complex of rat neonatal Fc receptor with Fc. Nature 372, 379–383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.