Abstract

It remains extraordinarily challenging to elucidate endogenous protein-protein interactions and proximities within the cellular milieu. The dynamic nature and the large range of affinities of these interactions augment the difficulty of this undertaking. Among the most useful tools for extracting such information are those based on affinity capture of target bait proteins in combination with mass spectrometric readout of the co-isolated species. Although highly enabling, the utility of affinity-based methods is generally limited by difficulties in distinguishing specific from nonspecific interactors, preserving and isolating all unique interactions including those that are weak, transient, or rapidly exchanging, and differentiating proximal interactions from those that are more distal. Here, we have devised and optimized a set of methods to address these challenges. The resulting pipeline involves flash-freezing cells in liquid nitrogen to preserve the cellular environment at the moment of freezing; cryomilling to fracture the frozen cells into intact micron chunks to allow for rapid access of a chemical reagent and to stabilize the intact endogenous subcellular assemblies and interactors upon thawing; and utilizing the high reactivity of glutaraldehyde to achieve sufficiently rapid stabilization at low temperatures to preserve native cellular interactions. In the course of this work, we determined that relatively low molar ratios of glutaraldehyde to reactive amines within the cellular milieu were sufficient to preserve even labile and transient interactions. This mild treatment enables efficient and rapid affinity capture of the protein assemblies of interest under nondenaturing conditions, followed by bottom-up MS to identify and quantify the protein constituents. For convenience, we have termed this approach Stabilized Affinity Capture Mass Spectrometry. Here, we demonstrate that Stabilized Affinity Capture Mass Spectrometry allows us to stabilize and elucidate local, distant, and transient protein interactions within complex cellular milieux, many of which are not observed in the absence of chemical stabilization.

Insights into many cellular processes require detailed information about interactions between the participating proteins. However, the analysis of such interactions can be challenging because of the often-diverse physicochemical properties and the abundances of the constituent proteins, as well as the sometimes wide range of affinities and complex dynamics of the interactions. One of the key challenges has been acquiring information concerning transient, low affinity interactions in highly complex cellular milieux (3, 4).

Methods that allow elucidation of such information include co-localization microscopy (5), fluorescence protein Förster resonance energy transfer (4), immunoelectron microscopy (5), yeast two-hybrid (6), and affinity capture (7, 8). Among these, affinity capture (AC)1 has the unique potential to detect all specific in vivo interactions simultaneously, including those that interact both directly and indirectly. In recent times, the efficacy of such affinity isolation experiments has been greatly enhanced through the use of sensitive modern mass spectrometric protein identification techniques (9). Nevertheless, AC suffers from several shortcomings. These include the problem of 1) distinguishing specific from nonspecific interactors (10, 11); 2) preserving and isolating all unique interactions including those that are weak and/or transient, as well as those that exchange rapidly (10, 12, 13); and 3) differentiating proximal from more distant interactions (14).

We describe here an approach to address these issues, which makes use of chemical stabilization of protein assemblies in the complex cellular milieu prior to AC. Chemical stabilization is an emerging technique for stabilizing and elucidating protein associations both in vitro (15–20) and in vivo (3, 12, 14, 21–29), with mass spectrometric (MS) readout of the AC proteins and their connectivities. Such chemical stabilization methods are indeed well-established and are often used in electron microscopy for preserving complexes and subcellular structures both in the cellular milieu (3) and in purified complexes (30, 31), wherein the most reliable, stable, and established stabilization reagents is glutaraldehyde. Recently, glutaraldehyde has been applied in the “GraFix” protocol in which purified protein complexes are subjected to centrifugation through a density gradient that also contains a gradient of glutaraldehyde (30, 31), allowing for optimal stabilization of authentic complexes and minimization of nonspecific associations and aggregation. GraFix has also been combined with mass spectrometry on purified complexes bound to EM grids to obtain a compositional analysis of the complexes (32), thereby raising the possibility that glutaraldehyde can be successfully utilized in conjunction with AC in complex cellular milieux directly.

In this work, we present a robust pipeline for determining specific protein-protein interactions and proximities from cellular milieux. The first steps of the pipeline involve the well-established techniques of flash freezing the cells of interest in liquid nitrogen and cryomilling, which have been known for over a decade (33, 34) to preserve the cellular environment, as well as having shown outstanding performance when used in analysis of macromolecular interactions in yeast (35–39), bacterial (40, 41), trypanosome (42), mouse (43), and human (44–47) systems. The resulting frozen powder, composed of intact micron chunks of cells that have great surface area and outstanding solvent accessibility, is well suited for rapid low temperature chemical stabilization using glutaraldehyde. We selected glutaraldehyde for our procedure based on the fact that it is a very reactive stabilizing reagent, even at lower temperatures, and because it has already been shown to stabilize enzymes in their functional state (48–50). We employed highly efficient, rapid, single stage affinity capture (36, 51) for isolation and bottom-up MS for analysis of the macromolecular assemblies of interest (52–54). For convenience, we have termed this approach Stabilized Affinity-Capture Mass Spectrometry (SAC-MS).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Equipment

Rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG); sodium monohydrogenphosphate; ammonium sulfate; glycine (Gly); hydrochloric acid, HCl; formic acid; acetic acid; triethylamine; glycerol; CHAPS; magnesium chloride; Triton X 100; Tween 20; Tris hydrochloride; 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES); sodium chloride; dithiothreitol; urea; glutaraldehyde (EM grade); ammonium bicarbonate; and iodoacetamide, were obtained from Sigma; M270 Epoxy DynabeadsTM was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). TPCK-treated modified trypsin from Bos taurus was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). EDTA-free protease inhibitor mixture was from Roche. Optima grade methanol, water, acetonitrile, and chloroform were obtained from Fisher Scientific. The planetary ball mill, model PM100, was from Retsch (Haan, Germany), Ultimate HPLC system from LC Packings/Dionex, and the ESI/ETD-LTQ XL-Orbitrap instrument was from Thermo Electron (San Jose, CA).

Yeast Strains

Described in the Supplemental Table S8.

Yeast Culture

The yeast culture was prepared according to the protocol described in (36). All yeast strains were harvested in the mid-log phase (2–3 × 107 cells/ml) by centrifugation. The cell pellet was immediately flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. Flash-frozen yeast cell pellets were subjected to mechanical cell disruption in the planetary ball mill in 3 min cycles at the liquid nitrogen temperature. Cycles were repeated until complete cell wall disruption was achieved as assessed by light microscopy after each grinding cycle.

Antibody Conjugation to Magnetic Dynabeads

Rabbit IgG was covalently immobilized on the surface of Epoxy M270 Dynabeads using the protocol recommended by the manufacturer, and optimized for rabbit IgG. A solution containing 0.1 m phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 1.5 m ammonium sulfate, and 0.5 mg/ml of rabbit IgG was used in the immobilization step. An aliquot of 20 μl of this solution was used per milligram of Dynabeads. The suspension was incubated overnight at 30 °C. Unreacted epoxy groups were quenched by rapid wash with 100 mm Gly solution (acidified by HCl, pH 2.5). The acid was then neutralized by rapid wash with fresh 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.8. The beads were washed with 100 mm triethylamine solution, followed by four washes with PBS solution and two washes with PBS containing 0.5% Triton X-100. The detergent was removed by PBS washes and the beads were subsequently transferred into a PBS-glycerol (1:1 v/v) solution and stored at −20 °C (45).

Affinity Isolation of Protein A-tagged Complexes from the Yeast Cell Lysate

The frozen yeast powder (−196 °C) was mixed with the extraction buffer at RT in 1 to 4 (wt/wt) ratio in combination with glutaraldehyde (see below). The resulting solution was shaken until completely homogenized and kept on ice. After 5 min, 1 m Tris buffer (pH 8) was added to a final concentration of 100 mm. Undissolved material was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. Magnetic beads with the conjugated antibody were added to the supernatant and the vial containing the suspension was incubated at 4 °C with a gentle tumbling motion. After 1h, the beads were removed from the cell lysate and washed five times with the extraction buffer. Affinity-isolated protein complexes were eluted from the beads using a solution of 1% (wt/v) SDS and 20 mm Tris, pH 8 (36). [See Supplementary Method for detailed information about extraction buffer optimization].

Glutaraldehyde Stabilization

Glutaraldehyde can undergo rapid aldol condensation at room temperature when exposed to pH 7–8 (55). To minimize the effect of proteins being modified by oligomeric glutaraldehyde in the stabilization experiments, we stored the stabilizing reagent frozen and added it to the extraction buffer just before addition to the frozen yeast powder. The concentration of glutaraldehyde was optimized by monitoring the efficiency of affinity capture of the bait protein in association with its interactors (see, e.g. supplemental Fig. S3).

Trypsin Proteolysis

Disulfide bonds in the denatured, affinity-isolated proteins were reduced by treatment with 20 mm DTT at 60 °C for 1h. Free cysteinyl residues were alkylated for 40 min at room temperature and in the dark with freshly prepared 50 mm iodoacetamide. Proteins were separated from detergents and other small molecules by methanol-chloroform precipitation(56). An aliquot of 20 μl of 8 m urea solution in 100 mm Tris pH 8 was added to the protein pellet, and the solution was subjected to an ultrasonic bath for 5 min. The solution obtained was diluted with 140 μl of 25 mm ammonium bicarbonate. An aliquot containing 100 ng of trypsin was added to each sample, and the solution was incubated at 37 °C overnight. Peptide mixture was desalted using a C18 Stage tip (57).

LC-MS

Liquid chromatography was performed using an Ultimate HPLC equipped with a FAMOS auto sampler. The system consisted of a trap column—5 mm (L) × 0.3 mm (ID), 10 μm particle size, PepMap C18-resin (LC Packings)—and an in-house packed PicoFrit column—13 cm (L) × 75 μm (ID), 3 μm particle size, C18 Reprosil Pur C18-AQ (Dr. Maisch GmbH). The system was operated with a measured flow rate of 200 nl/min and the column eluate was electrosprayed at 1.8 kV into the heated ion transfer capillary (275 °C) of the mass spectrometer (ESI/ETD-LTQ XL-Orbitrap, Thermo). Peptide mixtures were separated using a linear 1-hour acetonitrile gradient. Solvent A consisted of 5%v acetonitrile and 0.1%v formic acid in water, and solvent B of 5%v water and 0.1%v formic acid in acetonitrile. Eluted peptides were MS analyzed either using a method for fragmentation of the ten most abundant ions measured from an MS1 scan (top 10) or using an MS1-only method. Precursor masses were measured on the Orbitrap analyzer at a resolution of 60,000. MS/MS experiments were performed with CID activation, and fragment ions were analyzed in the linear ion trap analyzer. For label-free quantification, each sample was subjected to five LC-MS runs (two using the top-10 method for peptide identification and three with MS1-only method for more accurate intensity-based label-free quantification). We selected a 3 min window of retention time to match peaks between chromatographic runs. Protein identifications were performed using both X!Tandem (version SLEDGEHAMER) and MaxQuant (version 1.4.1.2)(58) against the Saccharomyces cerevisiae database, whereas label-free quantification was performed using the MaxQuant software. [Refer to the supplemental Material section for more experimental details.] The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium (59) via the PRIDE partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD001262.

RESULTS

We present here the SAC-MS methodology as a means to preserve protein-protein interactions in complex cellular environments. Our approach utilizes a combination of mild glutaraldehyde treatment, optimized affinity capture, and bottom-up MS analyses of the isolated proteins. A salient and crucial feature of our procedure, which sets it apart from many other crosslinking-MS approaches, is the use of substoichiometric amounts of glutaraldehyde with respect to the number of reactive lysine side chains and terminal amino groups. This low molar ratio is optimized for stabilization of native interactions, efficient affinity isolation, and minimal interference with MS readout. Although glutaraldehyde has been widely used for stabilization purposes in electron and optical microscopy (5, 30, 32, 60, 61), it has been seldom used with MS in the cellular context, and in these cases, it has been used largely for visualization of low molecular mass metabolites (62). Indeed, in the MS context, glutaraldehyde has often been considered detrimental (63). Our present approach differs from much of the prior works that used MS as a readout tool for protein interactions in complex cellular milieux in that we do not use denaturing conditions to isolate the stabilized assemblies, and we make no attempt to isolate and identify the cross-linked peptides themselves (16, 18, 27). Thus, while our strategy does not provide classical amino acid-to-amino acid crosslinking information, it does provide protein association and proximity information for stable, weak, and even transient interactions within the cellular milieu.

Experimental Approach

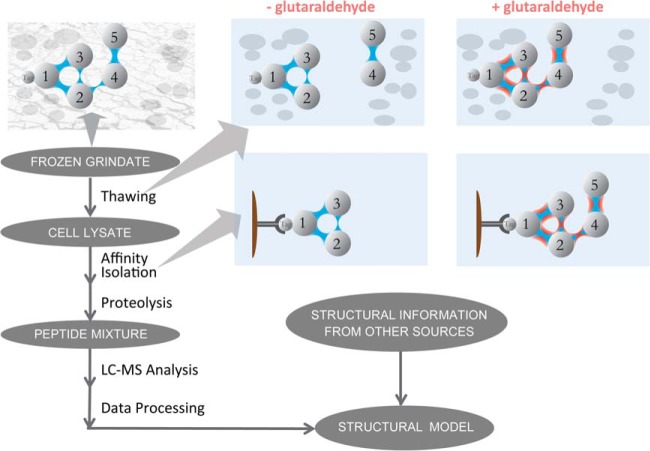

Fig. 1 illustrates the workflow of our SAC-MS pipeline for targeted protein interaction and proximity analysis. The protein of interest is tagged at its endogenous locus within the genome. After preparing the tagged cell strains under states in which we wish to determine the interactions of the targeted protein, these states are literally “frozen in place” by rapidly plunging these cells into liquid nitrogen. These cells are then subjected to cryomilling at the temperature of liquid nitrogen (10, 36, 51) when the cellular material is rendered brittle. Most importantly, the resulting submicron frozen pieces represent largely intact cell fragments, where local interactions are largely maintained. Working with the resulting frozen grindates has three advantages. The first is that biological material obtained under a range of conditions over an extended period of time can be stored stably at low temperature until needed (35, 36, 51). The second is that the stabilizing reagent glutaraldehyde can be introduced directly to the frozen grindate, ensuring that this highly toxic reagent may rapidly stabilize the macromolecular assemblies of interest without the perturbing physiological effects that it induces in live cells (64). The third advantage is that, during thawing, diffusion of the stabilizing reagent to the targeted intact endogenous subcellular assemblies is rapid, thereby providing fast stabilization.

Fig. 1.

The Stabilized Affinity-Capture Mass Spectrometry (SAC-MS) pipeline for targeted determination of specific protein-protein interactions and proximities in cellular milieux.

We chose glutaraldehyde as a stabilizing reagent because it is highly reactive, even at low temperatures, thus minimizing the dissociation of the assemblies prior to their stabilization. It has been shown that the stabilizing effect of glutaraldehyde depends strongly on its concentration and the protein concentration (30). In general, as we increase the molar ratio of glutaraldehyde-to-lysyl residues in the cell grindate, the level of lysine modification increases. Although increased levels of modification normally result in increased degrees of stabilization, such modifications may compromise the efficiency of the affinity isolation step. Consequently, we optimized the molar ratio to obtain the desired level of stabilization while maintaining an efficient affinity isolation. In the cases shown below, this molar ratio was selected to be ∼1:5 between glutaraldehyde and lysine residues in the protein complex samples.

The protein assemblies of interest are affinity-isolated from identical aliquots of frozen grindate after thawing in the nondenaturing extraction buffer in both the presence and the absence of glutaraldehyde, which allows us to specifically analyze the effects of the stabilizing reagent. This enables identification and quantitation of both proximal and distant interactors as well as those that are transient and/or weak (see below). Protein identification was performed after proteolysis of the affinity-isolated complexes followed by LC-MS analysis of the resulting proteolytic mixture (9). Finally, the resulting data are incorporated into structural and functional models that describe the system under study.

The experimental design for the SAC-MS pipeline is flexible and can be adjusted to address specific questions concerning particular macromolecular assemblies of interest. Here, we explore the functionality of our approach through a series of illustrative examples.

Targeted Elucidation of Local, Distant, and Transient Protein Interactions within the Cellular Milieu: Interactions in the Vicinity of the Heptameric Nup84 Subcomplex

As a first case, we explored proteins interacting both directly and indirectly with the yeast nuclear pore complex (NPC) (38, 39) protein component, Nup84. In budding yeast, the NPC is a 50 MDa protein assembly consisting of ∼500 protein subunits (involving 30 distinct proteins termed nucleoporins). NPCs, which are integral to the nuclear envelope, are the sole mediators of nucleocytoplasmic traffic. Nup84 interacts with six other NPC proteins—Nup120, Nup85, Nup145c, Nup133, Seh1, and Sec13—to form a stable heptameric assembly (570 kDa), the so-called Nup84 complex (65, 66). Sixteen copies of this Nup84 complex form the outer rings of the NPC (67).

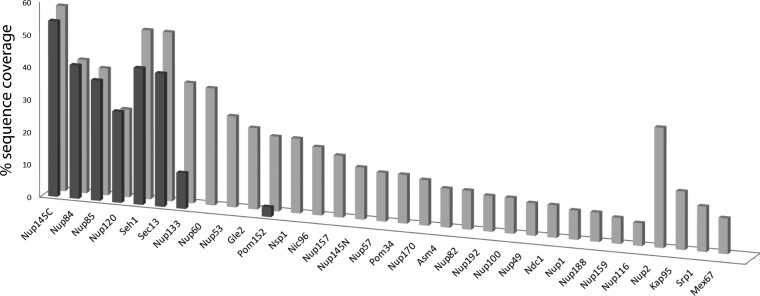

For affinity isolation of the Nup84 complex, we selected conditions that were slightly harsher than those previously reported by our group (35), so that the most labile component, Nup133, was significantly dissociated from the complex during isolation. These conditions were chosen to allow us to assess whether glutaraldehyde treatment enhances the stabilization of this labile subunit. We employed MS protein coverage as a means of evaluating such stabilization, where coverage was defined as the proportion of the protein observed in our LC-MS analyses. Fig. 2 compares the MS coverage of proteins identified after affinity capture of Nup84-PrA in the absence or presence of relatively gentle glutaraldehyde treatment (molar ratio of glutaraldehyde to lysine residues of 1:5; 5-min treatment at ≤4 °C prior to quenching). It is important to note that all conditions used in this comparative analysis were kept identical except for the presence of glutaraldehyde in the extraction buffer. The data were analyzed by the X!Tandem search engine (68), with the output list of identified proteins ordered by expectation values, and filtered by abundance (supplemental Tables S1–S4).

Fig. 2.

Targeted determination of proximal, distal, and transient protein interactors of the yeast nuclear pore complex protein Nup84. Protein A-tagged Nup84 was affinity-isolated in the absence or presence of the stabilizing reagent glutaraldehyde (see Fig. 1). The bars provide the percentage sequence coverage of affinity-isolated protein interactors in the absence (dark) and presence (light) of glutaraldehyde stabilization. For the same experiments, comparable results were obtained when the amounts of affinity captured proteins were estimated by spectral counting (supplemental Fig. S1).

The results summarized in Fig. 2 yielded four major findings. First, the coverage of protein A-tagged Nup84, the bait protein, was essentially unchanged with and without glutaraldehyde treatment, demonstrating that treatment at these levels did not significantly compromise the affinity capture and the MS analysis steps. This observation is noteworthy because treatments with aldehyde reagents have previously been observed to adversely affect both the efficiency of affinity isolation (69) and the quality of MS readouts (70, 71). Second, MS coverage of the most labile component, Nup133, increased significantly (more than 3-fold) in the presence of glutaraldehyde when compared with the other six components of the Nup84 complex, which differ by an average of only 1.12 ± 0.12. Third, upon this gentle glutaraldehyde treatment, we observed significant yields of 21 additional nucleoporins beyond the seven components of the Nup84 complex, demonstrating extensive stabilization of specifically interacting proteins at a distance. Finally, we observe several additional proteins that are known to interact dynamically or transiently with the NPC complex, including nucleocytoplasmic transporters (Kap95, Kap60, and Mex67) (72, 73) and the mobile NPC-associated factor, Nup2 (74).

One major question is the extent to which we observe a change in nonspecific associations in the affinity-capture experiments performed in the absence and presence of glutaraldehyde. supplemental Tables S1 and S2 compare the proteins identified in the absence and presence of glutaraldehyde, respectively, otherwise isolated under identical conditions. Using a high confidence expectation cutoff of 10−20, in the absence of glutaraldehyde, we observed the expected seven members of the Nup84 complex plus a small but significant contribution from the integral membrane nucleoporin Pom152, as well as nine other proteins not known to be associated with the NPC. It is noteworthy that all of these non-NPC proteins have abundances that are between 10-fold to more than 100-fold higher than the NPC components (67) (supplemental Tables S1 and S2). Thus, using a filter that eliminates proteins with abundances >10-fold larger than the NPC components, we are left with just the eight nucleoporins (supplemental Table S3). Applying the same criteria to the glutaraldehyde-treated affinity-captured material yielded 28 nucleoporins, four known transient or mobile NPC interactors, as well as three other proteins (Supplemental Table S4). Two of these three have chaperone activities (Sgt2 and Tcp1) (75–78), whereas the other (Spt5) (79) is a nuclear protein with no known association with the NPC. Thus, these proteins must be categorized as either contaminants or associations that have not been previously described. In either case, the enhancement of specific interactions using glutaraldehyde stabilization was profound. We conclude that such stabilization can enhance distant specific interactions, both stable and transient.

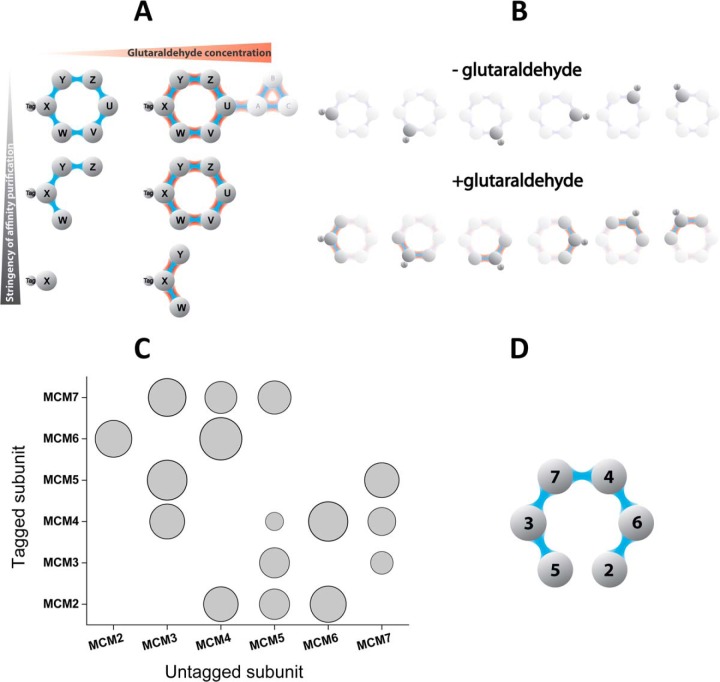

Deciphering Protein–Protein Connectivity within Complexes in the Cellular Milieu: Connectivity of the Six-subunit MCM Replication Helicase

Next, we investigated whether SAC-MS can provide detailed information about the connectivity of subunits within a protein assembly. For this purpose, we chose to investigate the MCM replication helicase from S. cerevisiae (80), a member of a well conserved subclass of eukaryotic hetero-hexameric AAA ATPases (81). Because the six proteins making up the MCM complex are known to form a doughnut shaped assembly with a central hole (82, 83), each protein can be connected to a maximum of only two other specific subunits, providing a convenient test bed for the ability of SAC-MS to determine this connectivity. Because SAC-MS on a stable complex (e.g. MCM) is simply likely to enhance the interaction with other more distant interactors, as shown in Fig. 2, we reasoned that it would be necessary to destabilize the complex partially in order to observe details of the local interaction, as illustrated schematically in Fig. 3A. Thus, we chose isolation conditions, which in the absence of chemical stabilization, were sufficiently stringent to isolate mainly the tagged MCM protein alone (Fig. 3A, bottom left). However, under the same stringency, but after glutaraldehyde stabilization, we reasoned that subunits proximal to the tagged protein might be observed with increased probability (Fig. 3A, bottom right).

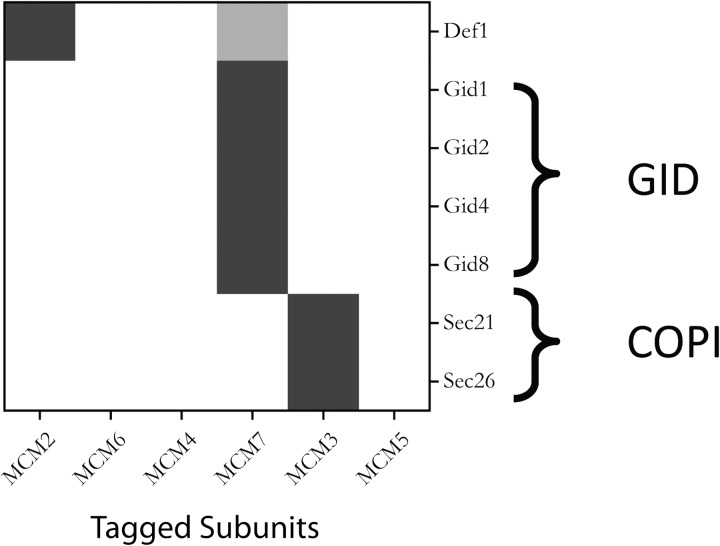

Fig. 3.

Using SAC-MS for deciphering connectivity for the MCM 2–7 protein complex. A, General scheme illustrating the trade-off between the degree of retained protein associations and stringency of the affinity purification. In SAC-MS experiments, the affinity-capture conditions may provide information on both local and distal interactors (top), but mildly destabilizing conditions may assist in identifying more local interactions (bottom). B, The introduction of genomic tags at different positions in the protein complex in conjunction with mildly destabilizing SAC-MS conditions (Fig. 3A bottom) can provide information about subunit connectivity within the complex. C, Experimentally determined glutaraldehyde-induced increase of MS peak intensities for nontagged MCM components. The SAC-MS experiment was performed under mildly destabilizing conditions (Fig. 3A bottom) using all the individually protein A-tagged MCM subunits (Fig. 3B). The vertical axis indicates which MCM subunit was genomically tagged for the experiment; whereas the horizontal axis indicates the measured protein. The area under the circle is proportional to the logarithm of the increase in MS signal intensity that is associated with the measured intensity for the same MCM component in the glutaraldehyde-treated sample (+) compared with the glutaraldehyde-free sample (–). D, Connectivity model for the MCM complex obtained using data from Fig. 3C (also in the Supplementary Method).

We performed these experiments using six different strains of yeast containing respectively genomically tagged Mcm2, Mcm3, Mcm4, Mcm5, Mcm6, and Mcm7. The affinity capture conditions were sufficiently stringent so as to dissociate the complex considerably, but still mild enough so as to be nondenaturing (supplementary Methods), leading to the isolation of the tagged protein as the dominant species at much higher levels than the other subunits in each case (supplemental Table S5; and illustrated schematically in Fig. 3A, left column). Under these same affinity-capture conditions, but in the presence of glutaraldehyde, we observed a significant increase in MS signals for some of the untagged MCM subunits, as depicted in Fig. 3B, and by the quantitative experimental results provided in Fig. 3C. Although each subunit did not respond equally to stabilization, the experimentally observed enhancements provided sufficient information to unambiguously assign the connectivity between the six MCM subunits (supplemental Tables S5–S7, and supplementary Methods). The set of connectivities determined using this approach (Fig. 3D) agrees with the partially elucidated set previously obtained via affinity isolation of overexpressed MCM subunits after crosslinking with DSP in crude D. melanogaster embryo extract (84), the in vitro pairwise association experiments of S. cerevisiae MCM subunits (85), and most recently, with the set obtained by negative stain electron microscopy of D. melanogaster MCM subunits overexpressed in baculovirus (82). This leads us to conclude that SAC-MS can provide reliable connectivity information from endogenous complexes stabilized in their cellular environment.

Exploring Labile Protein Interactions within the Cellular Milieu: Interactions of Non-chromatin Bound MCM Subunits

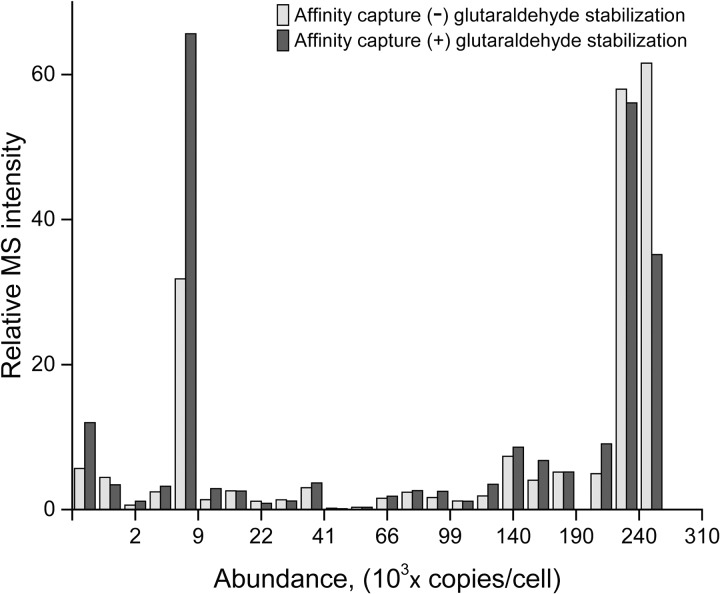

In our SAC-MS study of Nup84 described above, we identified both proximal and distant interactors within the nuclear pore complex (NPC). In addition to these stably interacting components, SAC-MS permitted us to identify transport factors transiently associated with the NPC. Here, we further explored how we might exploit this ability to identify interactions that are transient or unstable enough as to preclude their identification by our usual affinity capture experiments. Specifically, we identified SAC-MS-enhanced proteins with each of the six MCM subunits in the non-chromatin bound MCM fraction. We chose to investigate this fraction because it is much less studied than MCM complexes attached to the DNA-associated replication machinery (80, 83). Enrichment of this non-chromatin bound fraction was achieved by omitting DNase treatment and sonication steps during AC. This way, most of the chromatin associated MCM was removed during the centrifugation step, together with the chromatin and cell debris (Supplementary Methods). This was confirmed by LC-MS analysis of the affinity-captured proteins from the glutaraldehyde-treated samples, which did not show a significant presence of the known chromatin-associated proteins such as GINS and Cdc45 (86)(supplemental Tables S9–S20). We ran separate SAC-MS analyses on each of the six MCM subunits; with five technical replicates for each experiment, requiring 60 LC-MS runs. We observed 28 proteins to be significantly enhanced in the SAC-MS analysis with the requirement that the identification was made with a PEP value of less than 4 × 10−6 and MS2count ≥3 (supplemental Tables S9–S20). As in our analysis of Nup84 interactors above, we assumed that false positive interactors would largely arise from nonspecific interactions of abundant proteins. An important question arises as to whether our treatment with glutaraldehyde increases such nonspecific background (30). To answer this question, we compared the integrated MS response of peptides from identified proteins that were affinity-isolated with the six MCM subunits with and without glutaraldehyde treatment as a function of protein abundance (Fig. 4). We expected that the nonspecific components would be highly represented by the most abundant proteins and indeed that was where we detected the highest MS response. Significantly, we did not observe any increase in the MS response for the glutaraldehyde-treated sample compared with the nontreated one. Conversely, in the low abundance portion of the plot, where we would expect to observe a high percentage of specific interactions, we did in fact observe an increase in the integrated MS response for the six glutaraldehyde-treated samples. We conclude that SAC-MS experiments can be performed under conditions that do not significantly increase the nonspecific background. Thus, here too we chose to discriminate against false positives arising from abundant proteins by setting an abundance threshold at CAI ≤ 0.30 (i.e. copy number ≤ 25,000, arbitrarily chosen to be 10-fold higher than copy numbers for the MCM subunits). This strategy allowed us to identify nine putative interactors with the nonchromatin-bound MCM fraction. Interestingly, none of these has been previously observed to interact with the MCM subunits. In particular, we observe interaction with four members of the GID complex, an assembly of up to seven proteins that has been associated with polyubiquitination of enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis (87, 88).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of the proteome resulting from affinity co-capture using protein A-tagged MCM subunits in (–)-glutaraldehyde (light) and (+)-glutaraldehyde (dark) experiments. Peptide MS intensities for each type of experiment were binned together according to the abundance of the corresponding protein (MS intensities for the tagged MCM subunits were excluded). The protein abundances were estimated using codon adaptation indexes (CAI) (2). The results indicate that glutaraldehyde treatment provides stabilization of the specific interactors without a significant increase of highly abundant, nonspecific background.

To test the hypothesis that these previously unobserved interactions with members of the GID complex occur in vivo, we looked for the reciprocal interactions by tagging three of these— that is, Vid30 and Vid24 (Fig. 5) and Gid7 (87, 88). All three of these reciprocal affinity-capture experiments identified Mcm7, confirming the hypothesis. And, although we did not identify other members of the MCM complex in these experiments (according to Fig. 5), we did observe all nine known members of the GID complex in each affinity-capture experiment, as well as a putative 10th member (Ydl176w) (89), indicating that the GID complex itself was relatively stable under the conditions used. These experiments confirm the previously undescribed in vivo interaction of Mcm7 with the GID complex, showing that SAC-MS can provide a useful means for the identification of interactions that are not readily observed under typical affinity capture conditions.

Fig. 5.

Identification of specific interactors for the individual MCM subunits within the non-chromatin bound fraction. The heat map shows the relative increase of the MS signal for proteins with CAI ≤ 0.30 (i.e. with copy numbers ≤ 25,000). The horizontal axis represents protein A-tagged MCM subunits arranged in the order of their connectivity within the MCM complex as determined above. Proteins observed to interact with these MCM subunits are shown on the vertical axis grouped according to the similarity of their binding characteristics with the MCM subunits (see supplementary Methods for details of this hierarchical clustering). Only proteins with an MS/MS count ≥3 and an MS intensity enhancement greater than threefold with glutaraldehyde treatment are shown.

DISCUSSION

We have described a pipeline for the elucidation of local, distal, and transient protein interactions within the complex cellular milieu. Each step of the pipeline was tuned to achieve specific goals (Fig. 1). For example, we utilized genomic tags in the experiments described here, which can be readily introduced into budding yeast via homologous recombination. The advantages of their use include the ability to produce native levels of the tagged protein and the use of a single, high-affinity bait. Alternatively, for organisms where genomic tagging is not feasible, tagged proteins on plasmids could be introduced, or alternatively, antibodies, when available, could be employed for affinity capture.

Concerning the chemical stabilization step, the current pipeline incorporates cryomilling prior to the introduction of chemical stabilization. Advantages of this combination versus in vivo crosslinking include ease of sample handling, rapid chemical stabilization at low temperature, as well as obviating the need to consider in vivo physiological responses to toxic reagents.

Glutaraldehyde was chosen here as the chemical stabilization reagent primarily for its high reactivity at low temperature. An essential component of the present pipeline is the comparison between proteins obtained under identical conditions, except for the absence or presence of glutaraldehyde prior to the protein extraction and affinity-capture step. This gives us the ability to assay sensitively only the effect of chemical stabilization prior to extraction and affinity capture. To render this strategy maximally informative, we found it necessary to tune the buffer mixtures used for protein extraction and affinity capture. As illustrated by the cartoon shown in Fig. 3A, we make these conditions increasingly more destabilizing as we focus on more local interactions. It is important to note that the present chemical stabilization treatment does not significantly decrease the affinity-capture efficiency, presumably because the glutaraldehyde-to-lysine (and terminal amines) molar ratio is low (∼1:5), and because buffer conditions are never so stringent as to denature the protein subunits. This high efficiency has important implications for the sensitivity of SAC-MS and makes it straightforward to compare affinity capture with and without chemical stabilization. In the future, this highly efficient, stabilized affinity-capture should also allow us to treat the isolated complexes with a second crosslinking reagent such as DSS in order to obtain conventional residue-to-residue crosslinking (16, 18, 20) information from endogenous complexes that normally dissociate during isolation (90).

Let us speculate as to what likely happens within a complex cellular milieu upon treatment with glutaraldehyde. Some fraction of the reacted glutaraldehyde moieties will link amines together within the milieu. By geometric and entropic considerations, the majority of these linkages will be intramolecular, with a smaller fraction being intermolecular. We hypothesize that the probability of crosslinking even directly interacting partners will be ≪1. This is precisely what we observe by direct experimental determination through gel-shift experiments visualized by Western blot against the bait protein Nup84-PrA (supplemental Fig. S2). The probability of crosslinking both directly interacting proteins together with more distant components will be much lower still, and again this is what we observe by experiment (supplemental Fig. S2). The results show that >90% of the Nup84 remains noncrosslinked, whereas just a few percent in total are crosslinked to the proximal subunits Nup133 and Nup145C. The amount of more distally crosslinked components is too low to be seen on the Western blot. Formation of intramolecular crosslinks within subunits of a complex can increase the conformation rigidity of the subunits(91, 92), thereby contributing to the stabilization of the overall complex. Intermolecular crosslinks will also stabilize the complex. When the ratio of the chemical stabilization reagent to reactive groups is low, as in our case, we expect and observe low yields of inter-subunit crosslinks. Because we observe significant stabilization of the complexes that we investigated, we infer that one of the major components of the stabilization is the result of intramolecular conformational rigidification. It should be noted that the low stoichiometries that we use in our SAC-MS experiments are not normally used by other workers(21–23). Rather, sufficiently large amounts of crosslinking reagent (typically 100–1000 fold higher than in the present case) are generally used to ensure efficient covalent linkage between the subunits of interest, so that these associated subunits can remain together under the highly denaturing conditions used in these experiments. In addition, typically the temperatures used are higher (25–37 °C versus <4 °C in the present case) and the reaction times are longer (30 min versus <5 min in the present case).

Of great importance is our observation that the mild glutaraldehyde treatment used for SAC-MS does not adversely affect the efficiency of the affinity-capture step. Thus, the sensitivity of the method is comparable with that of standard affinity-capture with MS readout. Because most of the affinity-captured complexes discussed here contain <200 putative associated proteins, conventional LC-MS can be readily applied for this analysis. Often, many of these detected proteins represent nonspecific associations of abundant cellular proteins (93). Here, we chose to use a simple abundance criterion to filter these out. We opted for this strategy because it effectively removes the majority of false positives, albeit at the expense of removing the occasional true positive. Although prior work using large amounts of crosslinking reagent can significantly increase the nonspecific background in chemically stabilized affinity-capture experiments (21, 22), we have shown that our low stoichiometry treatment is advantageous in that it stabilizes complexes without significantly increasing this background (Fig. 5). In the future, we plan to use our I-DIRT technique (10) for objectively differentiating specific from nonspecific interactors to further assess possible contributions to the background by glutaraldehyde stabilization. In addition, we plan to use I-DIRT in combination with SAC-MS to explore the utility of the method for capturing authentic transient and/or rapidly exchanging interactors.

Finally, as we add more and more tags and carry out SAC-MS experiments with each tagged protein, the interactomic datasets become increasingly large and multi-dimensional. We used a hierarchical clustering approach to sort this data, wherein we grouped proteins according to similarity in biochemical behavior. This allows us to extract interaction information within complex cellular milieux. In the future, we envisage extending this approach beyond that which is demonstrated here for the MCM complex subunits, by tagging judiciously chosen proteins and extending the SAC-MS analyses step-by-step across portions of a cell. For example, we determined that members of the GID complex interact with Mcm7. By tuning the affinity-capture conditions appropriately and using genomically tagged GID components, we can obtain detailed information about local connectivity within the GID complex, much as we did for the MCM complex, and determine unambiguously which GID subunit interacts with Mcm7. In addition, information about GID interactors could be obtained in a subunit-specific manner, as we did for the MCM complex, which could serve as the basis for further expanding the reach of the SAC-MS analyses and thus form the basis of a rudimentary “molecular microscope” (94).

We have shown several examples where SAC-MS allows us to stabilize and identify protein interactors that would otherwise be either attenuated or completely absent when affinity isolation is used without a chemical stabilization reagent. Therefore, for example, we saw that glutaraldehyde stabilization enhanced the somewhat labile Nup133 component of the Nup84 complex and allowed observation of most of the other NPC components as well as several transiently interacting transport factors. SAC-MS also allowed us to identify correctly the connectivity of the six subunits that form the MCM complex, as well as to identify the interaction of Mcm7 with the GID complex, an association not readily observable by standard affinity capture. Further work is needed to determine the full extent to which SAC-MS can illuminate such weak, transient or unstable interactions. For example, it will be interesting to use SAC-MS to investigate enzyme-substrate interactions, a class that is particularly challenging to study by regular affinity capture (90, 95, 96).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alan Tackett for providing protein A tagged yeast strains, and Júlio C. Padovan, Paul D. B. Olinares, Zhanna Hakhverdyan, and Michael Rout for useful discussion and advice on manuscript preparation. In addition, we thank Júlio C. Padovan for his help with proofreading the manuscript and data conversion prior to the submission to PRIDE repository.

Footnotes

Author contributions: R.I.S. and B.T.C. designed research; R.I.S. performed research; R.I.S. and B.T.C. contributed new reagents or analytic tools; R.I.S. and B.T.C. analyzed data; R.I.S. and B.T.C. wrote the paper.

* This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health Grants, P41 GM103314 and U54 GM103511.

This article contains Supplemental Figs. S1 to S3 and Tables S1 to S26.

This article contains Supplemental Figs. S1 to S3 and Tables S1 to S26.

1 The abbreviations used are:

- AC

- affinity capture

- CAI

- codon adaptation index

- DSP

- dithio-bis(succinimidyl propionate

- DSS

- disuccinimidyl suberate

- EM

- electron microscopy

- GID

- glucose-induced degradation complex

- GraFix

- gradient fixation

- IgG

- immunoglobulin G

- MCM

- mini-chromosome maintenance complex

- MS/MS

- tandem MS scan

- MS1

- precursor MS scan

- PEP

- posterior error probability

- PrA

- protein A tag, consists of 3.5 repeating units of the IgG binding domain of the Staphylococcus aureus protein A (1)

- QTAX

- quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in-vivo cross-linked protein complexes

- RNA

- ribonucleic acid

- RT

- room temperature

- SAC-MS

- Stabilized Affinity-Capture Mass Spectrometry

- DNA

- deoxyribonucleic acid

- TAP

- tandem affinity protein tag, consists of a calmodulin binding peptide, a TEV cleavage site, and two IgG binding domains of the Staphylococcus aureus protein A (2).

REFERENCES

- 1. Strambio-de-Castillia C., Tetenbaum-Novatt J., Imai B. S., Chait B. T., Rout M. P. (2005) A method for the rapid and efficient elution of native affinity-purified protein A tagged complexes. J. Proteome Res. 4, 2250–2256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ghaemmaghami S., Huh W., Bower K., Howson R. W., Belle A., Dephoure N., O'Shea E. K., Weissman J. S. (2003) Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature 425, 737–741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dettmer U., Newman A. J., Luth E. S., Bartels T., Selkoe D. (2013) In vivo cross-linking reveals principally oligomeric forms of α-synuclein and β-synuclein in neurons and non-neural cells. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 6371–6385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piston D. W., Kremers G. (2007) Fluorescent protein FRET: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Trends Biochem. Sci. 32, 407–414 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Buser C., McDonald K. (2010) Correlative GFP-immunoelectron microscopy in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 470, 603–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Uetz P., Giot L., Cagney G., Mansfield T. A., Judson R. S., Knight J. R., Lockshon D., Narayan V., Srinivasan M., Pochart P., Qureshi-Emili A., Li Y., Godwin B., Conover D., Kalbfleisch T., Vijayadamodar G., Yang M., Johnston M., Fields S., Rothberg J. M. (2000) A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 403, 623–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Gavin A., Aloy P., Grandi P., Krause R., Boesche M., Marzioch M., Rau C., Jensen L. J., Bastuck S., Dümpelfeld B., Edelmann A., Heurtier M., Hoffman V., Hoefert C., Klein K., Hudak M., Michon A., Schelder M., Schirle M., Remor M., Rudi T., Hooper S., Bauer A., Bouwmeester T., Casari G., Drewes G., Neubauer G., Rick J. M., Kuster B., Bork P., Russell R. B., Superti-Furga G. (2006) Proteome survey reveals modularity of the yeast cell machinery. Nature 440, 631–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krogan N. J., Cagney G., Yu H., Zhong G., Guo X., Ignatchenko A., Li J., Pu S., Datta N., Tikuisis A. P., Punna T., Peregrín-Alvarez J. M., Shales M., Zhang X., Davey M., Robinson M. D., Paccanaro A., Bray J. E., Sheung A., Beattie B., Richards D. P., Canadien V., Lalev A., Mena F., Wong P., Starostine A., Canete M. M., Vlasblom J., Wu S., Orsi C., Collins S. R., Chandran S., Haw R., Rilstone J. J., Gandi K., Thompson N. J., Musso G., Onge P. S., Ghanny S., Lam M. H. Y., Butland G., Altaf-Ul A. M., Kanaya S., Shilatifard A., O'Shea E., Weissman J. S., Ingles C. J., Hughes T. R., Parkinson J., Gerstein M., Wodak S. J., Emili A., Greenblatt J. F. (2006) Global landscape of protein complexes in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nature 440, 637–643 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chait B. T. (2011) Mass spectrometry in the postgenomic era. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 239–246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tackett A. J., DeGrasse J. A., Sekedat M. D., Oeffinger M., Rout M. P., Chait B. T. (2005) I-DIRT, a general method for distinguishing between specific and nonspecific protein interactions. J. Proteome Res. 4, 1752–1756 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Cox J., Mann M. (2011) Quantitative, high-resolution proteomics for data-driven systems biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 80, 273–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Epshtein V., Kamarthapu V., McGary K., Svetlov V., Ueberheide B., Proshkin S., Alex, Mironov E., Nudler E., Mironov A. (2014) UvrD facilitates DNA repair by pulling RNA polymerase backwards. Nature 505, 372–377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Collins M. O., Choudhary J. S. (2008) Mapping multiprotein complexes by affinity purification and mass spectrometry. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 19, 324–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Weisbrod C. R., Chavez J. D., Eng J. K., Yang L., Zheng C., Bruce J. E. (2013) In vivo protein interaction network identified with a novel real-time cross-linked peptide identification strategy. J. Proteome Res. 12, 1569–1579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Gingras A., Gstaiger M., Raught B., Aebersold R., Raught R. A. B. (2007) Analysis of protein complexes using mass spectrometry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 645–654 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Leitner A., Walzthoeni T., Kahraman A., Herzog F., Rinner O., Beck M., Aebersold R. (2010) Probing native protein structures by chemical cross-linking, mass spectrometry, and bioinformatics. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1634–1649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bensimon A., Heck A. J. R., Aebersold R. (2012) Mass spectrometry–based proteomics and network biology. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 81, 379–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Müller M. Q., Ihling C. H., Sinz A. (2013) Analyzing PPARα/ligand interactions by chemical cross-linking and high-resolution mass spectrometry. Methods Mol. Biol. 952, 287–299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sinz A. (2006) Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometry to map three-dimensional protein structures and protein-protein interactions. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 25, 663–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Fischer L., Chen Z. A., Rappsilber J. (2013) Quantitative cross-linking/mass spectrometry using isotope-labelled cross-linkers. J. Proteomics 88, 120–128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Tagwerker C., Flick K., Cui M., Guerrero C., Dou Y., Auer B., Baldi P., Huang L., Kaiser P. (2006) A tandem affinity tag for two-step purification under fully denaturing conditions: application in ubiquitin profiling and protein complex identification combined with in vivo cross-linking. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 737–748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Guerrero C., Tagwerker C., Kaiser P., Huang L. (2006) An integrated mass spectrometry-based proteomic approach: quantitative analysis of tandem affinity-purified in vivo cross-linked protein complexes (QTAX) to decipher the 26 S proteasome-interacting network. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 5, 366–378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Guerrero C., Milenkovic T., Przulj N., Kaiser P., Huang L. (2008) Characterization of the proteasome interaction network using a QTAX-based tag-team strategy and protein interaction network analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 105, 13333–13338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Fang L., Kaake R. M., Patel V. R., Yang Y., Baldi P., Huang L. (2012) Mapping the protein interaction network of the human COP9 signalosome complex using a label-free QTAX strategy. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 11, 138–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chang Z., Kuchar J., Hausinger R. P. (2004) Chemical cross-linking and mass spectrometric identification of sites of interaction for UreD, UreF, and urease. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 15305–15313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zhang H., Tang X., Munske G. R., Zakharova N., Yang L., Zheng C., Wolff M. A., Tolic N., Anderson G. A., Shi L., Marshall M. J., Fredrickson J. K., Bruce J. E. (2008) In vivo identification of the outer membrane protein OmcA-MtrC interaction network in Shewanella oneidensis MR-1 cells using novel hydrophobic chemical cross-linkers. J. Proteome Res. 7, 1712–1720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bruce J. E. (2012) In vivo protein complex topologies: sights through a cross-linking lens. Proteomics 12, 1565–1575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kuo M. H., Allis C. D. (1999) In vivo cross-linking and immunoprecipitation for studying dynamic Protein:DNA associations in a chromatin environment. Methods 19, 425–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nittis T., Guittat L., LeDuc R. D., Ben Dao, Duxin J. P., Rohrs H., Townsend R. R., Stewart S. A. (2010) Revealing novel telomere proteins using in vivo cross-linking, tandem affinity purification, and label-free quantitative LC-FTICR-MS. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1144–1156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kastner B., Fischer N., Golas M. M., Sander B., Dube P., Boehringer D., Hartmuth K., Deckert J., Hauer F., Wolf E., Uchtenhagen H., Urlaub H., Herzog F., Peters J. M., Poerschke D., Lührmann R., Stark H. (2008) GraFix: sample preparation for single-particle electron cryomicroscopy. Nat. Methods 5, 53–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Stark H. (2010) GraFix: stabilization of fragile macromolecular complexes for single particle cryo-EM. Methods Enzymol. 481, 109–126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Richter F. M., Sander B., Golas M. M., Stark H., Urlaub H. (2010) Merging molecular electron microscopy and mass spectrometry by carbon film-assisted endoproteinase digestion. Mol. Cell. Proteomics 9, 1729–1741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Aitchison J. D., Blobel G., Rout M. P. (1996) Kap104p: A karyopherin involved in the nuclear transport of messenger RNA binding proteins. Science 274, 624–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schultz M. C., Hockman D. J., Harkness T. A., Garinther W. I., Altheim B. A. (1997) Chromatin assembly in a yeast whole-cell extract. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 9034–9039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fernandez-Martinez J., Phillips J., Sekedat M. D., Diaz-Avalos R., Velazquez-Muriel J., Franke J. D., Williams R., Stokes D. L., Chait B. T., Sali A., Rout M. P. (2012) Structure-function mapping of a heptameric module in the nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 196, 419–434 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Oeffinger M., Wei K. E., Rogers R., DeGrasse J. A., Chait B. T., Aitchison J. D., Rout M. P. (2007) Comprehensive analysis of diverse ribonucleoprotein complexes. Nat. Methods 4, 951–956 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Oeffinger M., Zenklusen D., Ferguson A., Wei K. E., Hage, el A., Tollervey D., Chait B. T., Singer R. H., Rout M. P. (2009) Rrp17p is a eukaryotic exonuclease required for 5′ end processing of Pre-60S ribosomal RNA. Mol. Cell 36, 768–781 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Alber F., Dokudovskaya S., Veenhoff L. M., Zhang W., Kipper J., Devos D., Suprapto A., Karni-Schmidt O., Williams R., Chait B. T., Rout M. P., Sali A. (2007) Determining the architectures of macromolecular assemblies. Nature 450, 683–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alber F., Dokudovskaya S., Veenhoff L. M., Zhang W., Kipper J., Devos D., Suprapto A., Karni-Schmidt O., Williams R., Chait B. T., Sali A., Rout M. P. (2007) The molecular architecture of the nuclear pore complex. Nature 450, 695–701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lee D. J., Busby S. J. W., Westblade L. F., Chait B. T. (2008) Affinity isolation and I-DIRT mass spectrometric analysis of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 Sakai RNA polymerase complex. J. Bacteriol. 190, 1284–1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Westblade L. F., Minakhin L., Kuznedelov K., Tackett A. J., Chang E. J., Mooney R. A., Vvedenskaya I., Wang Q. J., Fenyö D., Rout M. P., L R., Landick R., ick, Chait B. T., Severinov K., Darst S. A. (2008) Rapid isolation and identification of bacteriophage T4-encoded modifications of Escherichia coli RNA polymerase: a generic method to study bacteriophage/host interactions. J. Proteome Res. 7, 1244–1250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Field M. C., Adung'a V., Obado S., Chait B. T., Rout M. P. (2012) Proteomics on the rims: insights into the biology of the nuclear envelope and flagellar pocket of trypanosomes. Parasitology 139, 1158–1167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Di Virgilio M., Callen E., Yamane A., Zhang W., Jankovic M., Alex, Gitlin A. D., Gitlin E. D., Feldhahn N., Resch W., Oliveira T. Y., Chait B. T., Nussenzweig A., Casellas R., Robbiani D. F., Nussenzweig M. C. (2013) Rif1 prevents resection of DNA breaks and promotes immunoglobulin class switching. Science 339, 711–715 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Taylor M. S., Lacava J., Mita P., Molloy K. R., Huang C. R. L., Li D., Adney E. M., Jiang H., Burns K. H., Chait B. T., Rout M. P., Boeke J. D., Dai L. (2013) Affinity proteomics reveals human host factors implicated in discrete stages of LINE-1 retrotransposition. Cell 155, 1034–1048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Domanski M., Molloy K., Jiang H., Chait B. T., Rout M. P., Jensen T. H., LaCava J. (2012) Improved methodology for the affinity isolation of human protein complexes expressed at near endogenous levels. BioTechniques 0, 1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cristea I. M., Rozjabek H., Molloy K. R., Karki S., White L. L., Rice C. M., Rout M. P., Chait B. T., MacDonald M. R. (2010) Host factors associated with the Sindbis virus RNA-dependent RNA polymerase: role for G3BP1 and G3BP2 in virus replication. J. Virol. 84, 6720–6732 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Moorman N. J., Cristea I. M., Terhune S. S., Rout M. P., Chait B. T., Shenk T. (2008) Human cytomegalovirus protein UL38 inhibits host cell stress responses by antagonizing the tuberous sclerosis protein complex. Cell Host Microbe 3, 253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sabatini D. D., Bensch K., Barrnett R. J. (1963) Cytochemistry and electron microscopy. The preservation of cellular ultrastructure and enzymatic activity by aldehyde fixation. J. Cell Biol. 17, 19–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Schejter A., Bar-Eli A. (1970) Preparation and properties of crosslinked water-insoluble catalase. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 136, 325–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Walt D. R., Agayn V. I. (1994) The chemistry of enzyme and protein immobilization with glutaraldehyde. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 13, 425–430 [Google Scholar]

- 51. Oeffinger M., Aless, Fatica A., Fatica R., Rout M. P., Tollervey D. (2007) Yeast Rrp14p is required for ribosomal subunit synthesis and for correct positioning of the mitotic spindle during mitosis. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, 1354–1366 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Zhang Y., Fonslow B. R., Shan B., Baek M. 3rd, J. R. Y. (2013) Protein analysis by shotgun/bottom-up proteomics. Chem. Rev. 113, 2343–2394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Shevchenko A., Jensen O. N., Alex, Podtelejnikov A., Podtelejnikov R., Sagliocco F., Wilm M., Vorm O., Mortensen P., Shevchenko A., Boucherie H., Mann M. (1996) Linking genome and proteome by mass spectrometry: Large-scale identification of yeast proteins from two dimensional gels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93, 14440–14445 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Figeys D., Ducret A., Yates J. R., Aebersold R. (1996) Protein identification by solid phase microextraction-capillary zone electrophoresis-microelectrospray-tandem mass spectrometry. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 1579–1583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Rasmussen K., Albrechtsen J. (1974) Glutaraldehyde. The influence of pH, temperature, and buffering on the polymerization rate. Histochemistry 38, 19–26 [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wessel D., Flügge U. I. (1984) A method for the quantitative recovery of protein in dilute solution in the presence of detergents and lipids. Anal. Biochem. 138, 141–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wiœniewski J. R., Alex, Zougman A., Zougman R., Mann M. (2009) Combination of FASP and StageTip-based fractionation allows in-depth analysis of the hippocampal membrane proteome. J. Proteome Res. 8, 5674–5678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Cox J., Mann M. (2008) MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 26, 1367–1372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Vizcaino J. A., Deutsch E. W., Wang R., Csordas A., Reisinger F., Rios D., Dianes J. A., Sun Z., Farrah T., Bandeira N., Binz P., Xenarios I., Eisenacher M., Mayer G., Gatto L., Campos A., Chalkley R. J., Kraus H., Albar J. P., Martinez-Bartolome S., Apweiler R., Omenn G. S., Martens L., Jones A. R., Hermjakob H. (2014) ProteomeXchange provides globally coordinated proteomics data submission and dissemination. Nat. Biotechnol. 32, 223–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Wright R. (2000) Transmission electron microscopy of yeast. Microsc. Res. Techniq. 51, 496–510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Karnovsky M. J. (1965) A formaldehyde-glutaraldehyde fixative of high osmolality for use in electron microscopy. J. Cell Biol. 27, A137–A138 [Google Scholar]

- 62. Morozov V. N., Morozova T. Y., Johnson K. L., Naylor S. (2003) Parallel determination of multiple protein metabolite interactions using cell extract, protein microarrays and mass spectrometric detection. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 17, 2430–2438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Scheler C., Lamer S., Pan Z., Li X. P., Salnikow J., Jungblut P. (1998) Peptide mass fingerprint sequence coverage from differently stained proteins on two-dimensional electrophoresis patterns by matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization-mass spectrometry (MALDI-MS). Electrophoresis 19, 918–927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Karatzas K. A. G., Randall L. P., Webber M., Piddock L. J. V., Humphrey T. J., Woodward M. J., Coldham N. G. (2008) Phenotypic and proteomic characterization of multiply antibiotic-resistant variants of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium selected following exposure to disinfectants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 1508–1516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Lutzmann M., Kunze R., Buerer A., Aebi U., Hurt E. (2002) Modular self-assembly of a Y-shaped multiprotein complex from seven nucleoporins. EMBO J. 21, 387–397 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Siniossoglou S., Wimmer C., Rieger M., Doye V., Tekotte H., Weise C., Emig S., Segref A., Hurt E. C. (1996) A novel complex of nucleoporins, which includes Sec13p and a Sec13p homolog, is essential for normal nuclear pores. Cell 84, 265–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rout M. P., Aitchison J. D., Suprapto A., Hjertaas K., Zhao Y., Chait B. T. (2000) The yeast nuclear pore complex: composition, architecture, and transport mechanism. J. Cell Biol. 148, 635–652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Craig R., Beavis R. C. (2004) TANDEM: matching proteins with tandem mass spectra. Bioinformatics 20, 1466–1467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Kim T. H., Ren B. (2006) Genome-wide analysis of protein-DNA interactions. Annu. Rev. Genom. Human Genet. 7, 81–102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Farmer T. B., Caprioli R. M. (1998) Determination of protein-protein interactions by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 33, 697–704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Helin J., Caldentey J., Kalkkinen N., Bamford D. H. (1999) Analysis of the multimeric state of proteins by matrix assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry after cross-linking with glutaraldehyde. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 13, 185–190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Cook A., Bono F., Jinek M., Conti E. (2007) Structural biology of nucleocytoplasmic transport. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 647–671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Fabre E., Hurt E. (1997) Yeast genetics to dissect the nuclear pore complex and nucleocytoplasmic trafficking. Annu. Rev. Genet. 31, 277–313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Dilworth D. J., Suprapto A., Padovan J. C., Chait B. T., Wozniak R. W., Rout M. P., Aitchison J. D. (2001) Nup2p dynamically associates with the distal regions of the yeast nuclear pore complex. J. Cell Biol. 153, 1465–1478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kordes E., Savelyeva L., Schwab M., Rommelaere J., Jauniaux J. C., Cziepluch C. (1998) Isolation and characterization of human SGT and identification of homologs in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Caenorhabditis elegans. Genomics 52, 90–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Angeletti P. C., Walker D., Panganiban A. T. (2002) Small glutamine-rich protein/viral protein U-binding protein is a novel cochaperone that affects heat shock protein 70 activity. Cell Stress Chaperon. 7, 258–268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ursic D., Sedbrook J. C., Himmel K. L., Culbertson M. R. (1994) The essential yeast Tcp1 protein affects actin and microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 5, 1065–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Siegers K., Bölter B., Schwarz J. P., Böttcher U. M. K., Guha S., Hartl F. U. (2003) TRiC/CCT cooperates with different upstream chaperones in the folding of distinct protein classes. EMBO J. 22, 5230–5240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 79. Lindstrom D. L., Squazzo S. L., Muster N., Burckin T. A., Wachter K. C., Emigh C. A., McCleery J. A., 3rd, J. R. Y., Hartzog G. A. (2003) Dual roles for Spt5 in pre-mRNA processing and transcription elongation revealed by identification of Spt5-associated proteins. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 1368–1378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Tye B. K. (1999) MCM proteins in DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68, 649–686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Erzberger J. P., Berger J. M. (2006) Evolutionary relationships and structural mechanisms of AAA+ proteins. Annu. Rev. Bioph. Biom. 35, 93–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Aless, Costa A., Costa R., Ilves I., Tamberg N., Petojevic T., Nogales E., Botchan M. R., Berger J. M. (2011) The structural basis for MCM2–7 helicase activation by GINS and Cdc45. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 471–477 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Remus D., Beuron F., Tolun G., Griffith J. D., Morris E. P., Diffley J. F. X. (2009) Concerted loading of Mcm2–7 double hexamers around DNA during DNA replication origin licensing. Cell 139, 719–730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Crevel G., Ivetic A., Ohno K., Yamaguchi M., Cotterill S. (2001) Nearest neighbor analysis of MCM protein complexes in Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 29, 4834–4842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Davey M. J., Indiani C., O'Donnell M. (2003) Reconstitution of the Mcm2–7p heterohexamer, subunit arrangement, and ATP site architecture. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 4491–4499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Sclafani R. A., Holzen T. M. (2007) Cell cycle regulation of DNA replication. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 237–280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Santt O., Pfirrmann T., Braun B., Juretschke J., Kimmig P., Scheel H., Hofmann K., Thumm M., Wolf D. H. (2008) The yeast GID complex, a novel ubiquitin ligase (E3) involved in the regulation of carbohydrate metabolism. Mol. Biol. Cell 19, 3323–3333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Menssen R., Schweiggert J., Schreiner J., Kusevic D., Reuther J., Braun B., Wolf D. H. (2012) Exploring the topology of the Gid complex, the E3 ubiquitin ligase involved in catabolite-induced degradation of gluconeogenic enzymes. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 25602–25614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Ulitsky I., Shlomi T., Kupiec M., Shamir R. (2008) From E-MAPs to module maps: dissecting quantitative genetic interactions using physical interactions. Mol. Syst. Biol. 4, 209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Deshaies R. J., Joazeiro C. A. P. (2009) RING domain E3 ubiquitin ligases. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 78, 399–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Henchey L. K., Jochim A. L., Arora P. S. (2008) Contemporary strategies for the stabilization of peptides in the α-helical conformation. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 12, 692–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Zhang F., Sadovski O., Xin S., Xin S. J., Xin S. J., Woolley G. A. (2007) Stabilization of folded peptide and protein structures via distance matching with a long, rigid cross-linker. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 14154–14155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Mellacheruvu D., Wright Z., Couzens A. L., Lambert J., St-Denis N. A., Li T., Miteva Y. V., Hauri S., Sardiu M. E., Low T. Y., Halim V. A., Bagshaw R. D., Hubner N. C., Al-Hakim A., Bouchard A., Faubert D., Fermin D., Dunham W. H., Goudreault M., Lin Z., Badillo B. G., Pawson T., Durocher D., Coulombe B., Aebersold R., Superti-Furga G., Colinge J., Heck A. J. R., Choi H., Gstaiger M., Mohammed S., Cristea I. M., Bennett K. L., Washburn M. P., Raught B., Ewing R. M., Gingras A., Nesvizhskii A. I. (2013) The CRAPome: a contaminant repository for affinity purification-mass spectrometry data. Nat. Methods 10, 730–736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Gilchrist A., Au C. E., Hiding J., Alex, Bell A. W., Bell E. W., Fernandez-Rodriguez J., Fern J., Lesimple S., ez-Rodriguez, Nagaya H., Roy L., Gosline S. J. C., Hallett M., Paiement J., Kearney R. E., Nilsson T., Bergeron J. J. M. (2006) Quantitative proteomics analysis of the secretory pathway. Cell 127, 1265–1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Li X., Foley E. A., Kawashima S. A., Molloy K. R., Li Y., Chait B. T., Kapoor T. M. (2013) Examining post-translational modification-mediated protein-protein interactions using a chemical proteomics approach. Protein Sci. 22, 287–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Peterson S. E., Li Y., Wu-Baer F., Chait B. T., Baer R., Yan H., Gottesman M., Gautier J. (2013) Activation of DSB processing requires phosphorylation of CtIP by ATR. Mol. Cell 49, 657–667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.