Abstract

The fastidious behavior of T7 RNA polymerase limits the incorporation of synthetic nucleosides into RNA transcripts, particularly at or near the promoter. The practically exclusive use of GTP for transcription initiation further compounds this challenge, and reactions with GTP analogs, where the heterocyclic nucleus has been altered, have not, to our knowledge, been demonstrated. The enzymatic incorporation of thGTP, a newly synthesized isomorphic fluorescent nucleotide with a thieno[3,4-d]pyrimidine core, is explored. The modified nucleotide can initiate and maintain transcription reactions, leading to the formation of fully modified and highly emissive RNA transcripts with thG replacing all guanosine residues. Short and long modified transcripts are synthesized in comparable yields to their natural counterparts. To assess proper folding and function, transcripts were used to assemble a hammerhead ribozyme with all permutations of natural and modified enzyme and substrate strands. The thG modified substrate was effectively cleaved by the natural RNA enzyme, demonstrating the isomorphic features of the nucleoside and its ability to replace G residues while retaining proper folding. In contrast, the thG modified enzyme showed little cleavage ability, suggesting the modifications likely disrupted the catalytic center, illustrating the significance of the Hoogsteen face in mediating appropriate contacts. Importantly, the ribozyme cleavage reaction of the emissive fluorescent transcripts could be followed in real time by fluorescence spectroscopy. Beyond their utility as fluorescent probes in biophysical and discovery assays, the results reported point to the potential utility of such isomorphic nucleosides in probing specific mechanistic questions in RNA catalysis and RNA structural analysis.

Introduction

In vitro transcription reactions, particularly those mediated by T7 RNA polymerase, have become a cornerstone of modern RNA biochemistry and biophysics. These cell-free transformations facilitate the preparation of short as well as long native RNA transcripts using synthetic and plasmid-derived DNA templates. While of rather general utility, T7 RNA polymerase requires a specific promoter for optimal transcription and tends to also be rather sensitive to sequence composition, particularly next to its consensus promoter. Numerous studies have analyzed the initiation and elongation stages in these processes and, practically, identified optimal sequences at the transcript’s 5′ end.1−5 Guanosine residues are frequently found at positions +1 and +2, where altered sequences typically suffer from significantly diminished transcription efficiency.6,7 In vitro prepared transcripts therefore almost exclusively possess a GTP at their 5′ end, with 15 out of 17 reported promoters initiating transcription with pppG and 13 with pppGpG.8

A formidable contemporary challenge, which is compounded by the constraints outlined above, is the need to modify RNA transcripts, typically with fluorescent probes, for diverse biochemical and biophysical applications.9−12 This problem has been tackled in several ways, including the development of orthogonal base pairing systems, which require, however, the synthesis of modified DNA templates in addition to the necessary complementary modified triphosphates.13−16 The fastidious behavior of T7 RNA polymerase has also limited the modification position, with most appearing remote to the promoter, where the enzymatic process is believed to be beyond its vulnerable initiation phase.17−22 Replacing the initiating GTP at position +1 with alternatives such as GMP and guanosine, some with modifications on the monophosphate or ribose, has been explored with different levels of success.6,23−29 Transcription initiation with GTP analogs, where the heterocyclic nucleus has been altered has not, to our knowledge, been explored. This has motivated the study reported here, where newly synthesized thGTP, a highly isomorphic and emissive analog, has been investigated as a GTP surrogate in T7 RNA transcription reactions.

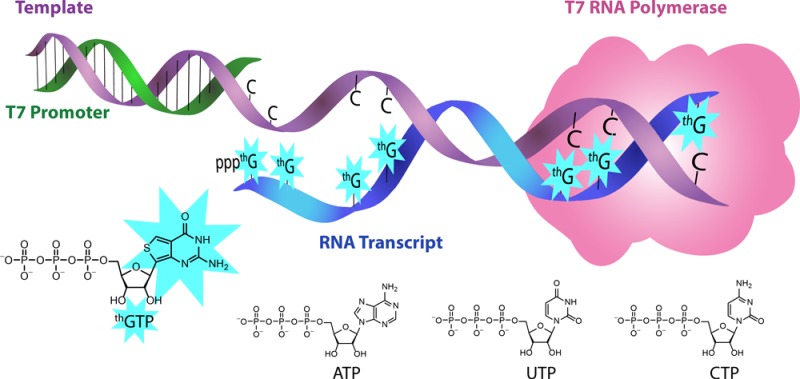

The recent completion of an emissive RNA alphabet, a fluorescent ribonucleoside set comprised of highly emissive purine and pyrimidine analogs, all derived from thieno[3,4-d]pyrimidine,30 presents unique opportunities for the generation of modified RNA constructs. Despite the high structural resemblance to their native counterparts,30 it was unclear at the onset of this project whether or not polymerases could accommodate and effectively incorporate these modified nucleosides into oligonucleotides.17 As discussed above, particularly challenging is the initiation of in vitro transcription reactions with GTP analogs, which is inevitable in this context. In this contribution we critically assess the ability of T7 RNA polymerase to initiate RNA transcription and elongate the nascent modified transcript using thGTP (2), a highly emissive and isomorphic GTP analog, and compare the results to its performance with the native triphosphate. We demonstrate that the modified nucleotide is capable of initiating and maintaining transcription reactions, leading to the formation of fully modified and highly emissive transcripts. Importantly, to assess proper folding and function of RNA transcripts where all G residues have been replaced with a synthetic analog, we explore modified hammerhead ribozymes, catalytic RNA assemblies, which are likely to be exceedingly sensitive to such alterations. The fully modified enzyme and substrate of the hammerhead ribozyme are efficiently transcribed, and the impact of replacing all G residues with thG is evaluated. We further demonstrate that the emissive transcripts can be used to monitor the ribozyme-mediated cleavage reaction in real time.

Results

Synthesis

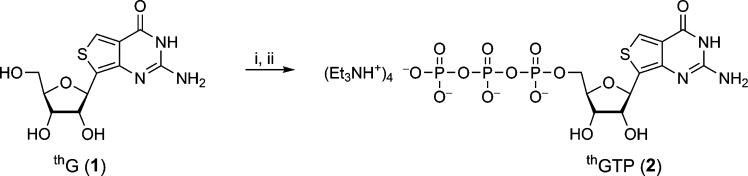

The 5′-triphosphate of thG was synthesized from the parent nucleoside using freshly distilled POCl3 and tributylammonium pyrophosphate (Scheme 1).31 The triphosphate was purified by ion-exchange chromatography and reverse-phase HPLC (see Experimental Section). Final treatment with Chelex 100 afforded the analytically pure nucleotide [31P NMR δ −9.98 (d, J = 20.1 Hz, Pγ), −10.64 (d, J = 18.6 Hz, Pα), −22.64 (t, J = 18.6 Hz, Pβ)].

Scheme 1. Synthesis of thGTP (2) from thG (1).

Reagents and conditions: (i) POCl3, (MeO)3PO, 0 °C; (ii) tributylammonium hydrogen pyrophosphate in DMF, Bu3N, 0 °C.

T7 RNA Polymerase-Mediated in Vitro Transcription Reactions

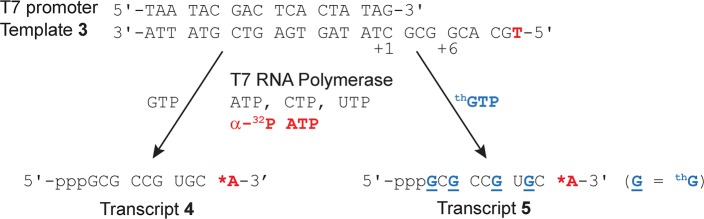

Transcription reactions with the analytically pure thGTP (2) and T7 RNA polymerase were performed to first analyze its enzymatic incorporation into short RNA oligonucleotides. A short DNA promoter–template duplex13,17 was used to discern the ability of thGTP to initiate transcription and be incorporated during the elongation phase (Figure 1). The DNA template 3 is terminated with a single T at the 5′ end so a lone A is directed to the 3′ end of the transcript. When trace amounts of α-32P ATP are used, only successfully transcribed full length labeled RNA products would be visible, whereas short failed transcripts would be undetected after gel electrophoresis (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

T7 promoter and template 3 depicting the enzymatic incorporation reaction using natural NTPs and GTP or thGTP resulting in transcripts 4 or 5. thG is underlined and bolded blue in transcript 5.

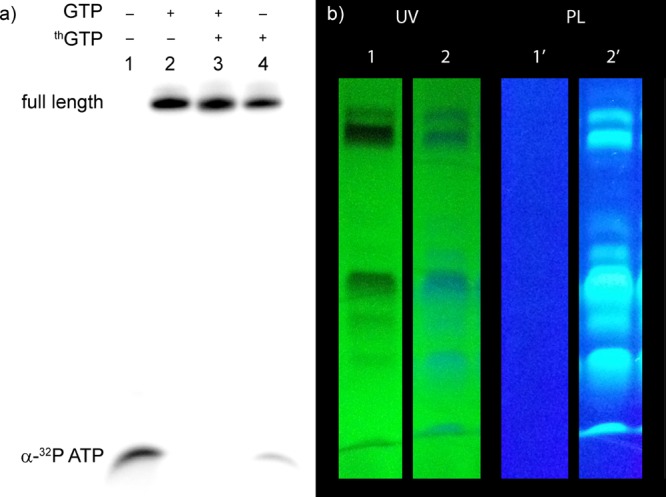

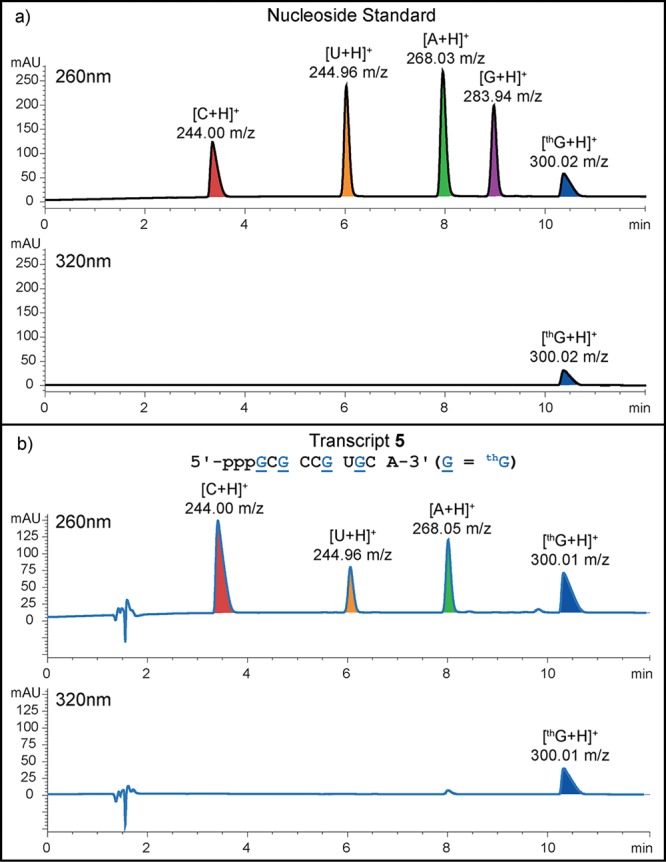

The T7 promoter and template 3 were annealed, and transcribed in the presence of natural NTPs or with thGTP replacing GTP and a trace of α-32P ATP. A phosphorimage revealed a full length 10-mer product (transcript 5) using thGTP that corresponded to the natural triphosphates transcript 4 (Figure 2a). The overall yield of transcript 5, containing four thG residues, compared to the natural unmodified transcript 4 was 70 ± 3%, indicating that the average individual incorporation was 91 ± 1%. Next, a large-scale transcription reaction was run and UV shadowing was used to visualize all products. Comparing the transcription reactions with GTP to reactions with thGTP illustrates that the desired product and abortive transcripts appear almost identical (compare lanes 1 and 2, respectively, in Figure 2b). Importantly, when visualizing the gel under UV illumination (302 nm), the product and initiation phase truncated transcripts are highly fluorescent (right Figure 2b). Following extraction, the isolated yield of the thG modified 10-mer (transcript 5) was 78 ± 12% compared to the native 10-mer (transcript 4), averaging 94 ± 2% per thG incorporation. The transcripts were characterized by ESI (Figure S1a) and digested using S1 nuclease and dephosphorylated. The nucleoside mixtures were subjected to HPLC-MS analysis. Comparing the chromatogram obtained for the native 10-mer (4, Figure S3b) to that of the modified one (5, Figure 3) confirms the presence of thG in the latter.

Figure 2.

Transcription reactions with template 3 in the presence of thGTP. (a) Small scale transcription using trace α-32P ATP. Lane 1: control transcription reaction in the absence of GTP or thGTP. Lane 2: control reaction in the presence of all natural NTPs. Lane 3: reaction in the presence of equimolar concentration of thGTP and GTP. Lane 4: reaction in the presence of thGTP. Incorporation efficiencies of thGTP transcripts are reported with respect to transcription in the presence of GTP. All reactions were performed in triplicate, and the errors reported are the standard deviations. (b) Large scale transcription reaction using template 3 with all natural NTPs (lane 1 and 1′) or ATP, UTP, CTP, and thGTP (lanes 2 and 2′, 78 ± 12% isolated yield) with UV light at 254 nm (on TLC plate) and 302 nm (PL). The reaction was resolved by gel electrophoresis on a denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel.

Figure 3.

HPLC-MS traces of the (a) mixture of nucleosides used as a standard and (b) digestion results of transcript 5. Digestion of 1–2 nmol of transcript was carried out using S1 nuclease for 2 h at 37 °C and followed by dephosphorylation with alkaline phosphatase for 2 h at 37 °C. The ribonucleoside mixture obtained was analyzed by reverse-phase analytical HPLC, using a mobile phase of 0–6% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) in water (0.1% formic acid) over 12 min; flow rate 1 mL/min.

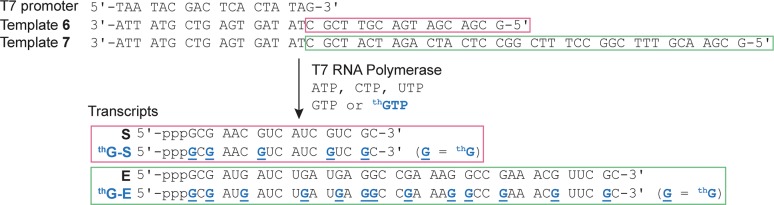

To test the runoff transcription of longer constructs and assess the function of the resulting transcripts, longer DNA templates (6 and 7) were used to generate hammerhead ribozymes: the natural all native substrate (S), the modified substrate (thG-S), the natural enzyme (E), and the modified enzyme (thG-E) (Figure 4). These transcription reactions were executed only on a large scale, and the RNA transcripts (S, thG-S, E, and thG-E) were isolated after polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Figure S4), characterized by ESI (Figure S1b and S1c), and then digested (Figure S3c and S3d). As before, the full length products and all short failed transcripts in transcription reactions using thGTP are highly emissive (Figure S4).

Figure 4.

T7 promoter and templates 6 and 7 depicting the enzymatic incorporation reaction using natural NTPs and GTP or thGTP resulting in transcripts S, thG-S, E, or thG-E. thG is underlined and bolded blue in the transcripts thG-S and thG-E.

HH Ribozyme Cleavage Reactions

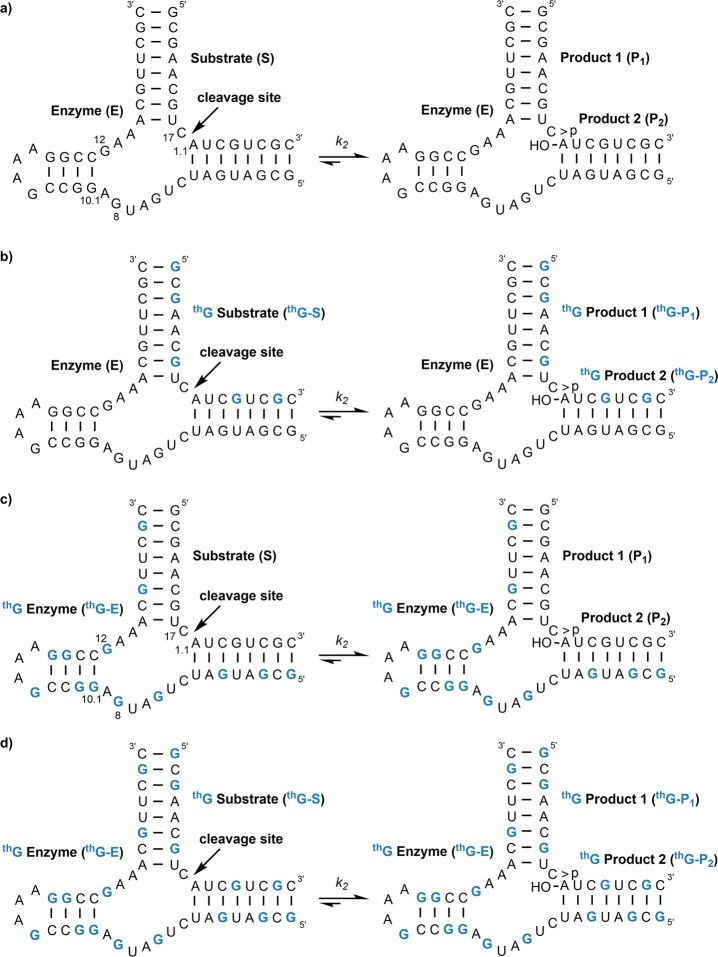

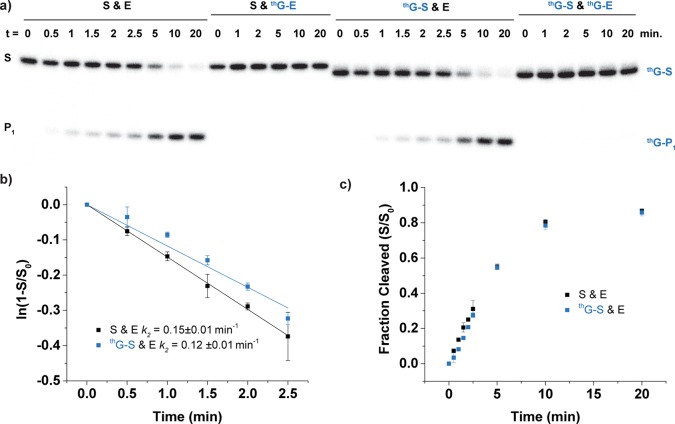

Following purification, the natural substrate (S) and thG-substrate (thG-S) were dephosphorylated with alkaline phosphatase and 5′ labeled with T4 polynucleotide kinase according to standard protocols.32 The assembled ribozymes were then tested for the anticipated strand cleavage in all different combinations (Figure 5), using conditions similar to those previously published,33,34 where the ribozyme cleavage reaction was initiated by mixing equal volumes of buffered solutions containing MgCl2 of substrate with enzyme. The reactions contained excess enzyme to obtain pseudo first-order kinetic rate constants (k2).33−35 Single turnover reactions at 31 °C contained 0.3 μM substrate (including a trace of 5′-32P labeled material) and 3 μM enzyme, in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2. The rate constants obtained for the native HH ribozyme S and E (Figure 5a) and the substrate-modified one thG-S and E (Figure 5b) were 0.15 ± 0.1 min–1 and 0.12 ± 0.1 min–1, respectively (Figure 6b). The unmodified HH enzyme E cleaved 87% and 86% of the substrates S and thG-S, respectively, at 20 min. The fully modified thG-containing enzyme (thG-E) showed no cleavage of S or thG-S at 31 °C (Figures 5c, 5d, and 6a). Reactions of thG-E with the natural and modified substrates at slightly elevated temperatures (37 °C) did show a small amount of sequence specific cleavage, estimated at about 2% after 40 min (Figure S5).

Figure 5.

Hammerhead ribozymes and cleavage reactions of (a) natural substrate and enzyme (S and E), (b) modified substrate and natural enzyme (thG-S and E), (c) natural substrate and modified enzyme (S and thG-E), and (d) modified substrate and modified enzyme (thG-S and thG-E).

Figure 6.

(a) HH ribozyme cleavage reaction results were followed by 32P radioactive labeling of substrate strands S and thG-S. S and P1, and thG-S and thG-P1 indicate substrate and product strands (Figure 5). All reactions were conducted at 31 °C and contained 0.3 μM substrate (including a trace of 5′-32P labeled material), 3 μM enzyme, 50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2. The reactions were quenched at the given times (t in min) and resolved by gel electrophoresis on a denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel with 7 M urea. (b) Initial kinetics of S and E and thG-S and E. The pseudo-first-order rate constants (k2) of the cleavage reactions are determined as the slope of ln(fraction cleaved) versus time. (c) Ribozyme-mediated cleavage curves as determined by 32P data for S and E and thG-S and E. Fraction cleaved (S/S0) was determined by dividing the amount of cleaved substrate by the sum of the full length and cleaved substrate.

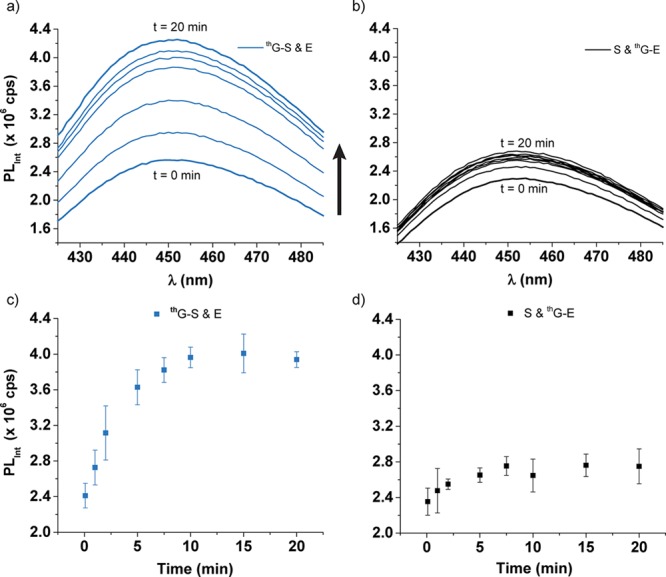

The cleavage of thG-S by the native enzyme E was monitored with nonradiolabeled material using steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy under the same conditions as the experiments performed with the radiolabeled constructs but in a slightly larger volume (see Figure S6 for absorption and emission spectra of thG-S). Mixing the substrate with the enzyme in a fluorescence cuvette at 31 °C gave final concentrations of 0.3 μM substrate and 3 μM enzyme in 50 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2. The fluorescence intensity, monitored at 450 nm, increased during the reaction (Figure 7a and 7c). Alternatively, the fully modified enzyme thG-E mixed with the native substrate S, which showed no measurable strand cleavage at 31 °C when monitored using the 32P labeled substrate, displayed minimal fluorescence intensity changes (Figure 7b and 7d). The fraction cleaved of thG-S from the radioactive and fluorescence experiments was normalized and showed a similar trend (Figure S7). Importantly, PAGE analysis confirms the presence of two fluorescent products thG-P1 and thG-P2 (see Figure S8).

Figure 7.

Fluorescence spectra of (a) thG-S and E (blue) (excitation 470 nm, emission 425–485 nm, slit widths 8 nm) and (b) S and thG-E (black) (excitation 470 nm, emission 425–485 nm, slit widths 4 nm), where t = 0 min and t = 20 min spectra have thicker lines. All reactions were conducted at 31 °C and contained 0.3 μM substrate, 3 μM enzyme, 50 mM Tris pH 7.0, 200 mM NaCl, and 10 mM MgCl2. The fluorescence intensity shown at 450 nm over 20 min of the (c) cleavage of thG-S by E (blue) and (d) mixing of S and thG-E (black).

Discussion

As has been previously demonstrated, fluorescent nucleoside analogs can tremendously facilitate the study of nucleic acid folding, recognition, and catalysis, including the enablement of real time assays.9,10,34,36 Of particular significance is the modification of oligonucleotides with isomorphic nucleoside analogs, as their high similarity to their canonical counterparts and nonperturbing nature frequently results in faithful folding and function.37 A case in point is our recent study of emissive mRNAs, where specific G residues have been surgically replaced by thG using solid-phase synthesis.38 These modified RNA constructs were recognized by the ribosome and capable of fluorescently reporting discrete steps in translation.39 Here we set to explore the ability of thGTP to support the initiation step of in vitro transcription reactions and then elongate the nascent RNA transcripts to yield full length products in which all G residues are replaced by thG. We then evaluate the impact of this rather dramatic modification on the function of the HH ribozyme as a prototypical functional RNA system.

The commonly used T7 promoters end with C, so one could not test a single G or thG incorporation in G-containing transcripts where a G residue is remote to the promoter. We therefore initially used a short oligonucleotide 3 that has been previously used by our lab to evaluate T7 RNA polymerase’s ability to produce short modified transcripts (Figure 1).17 Transcription reactions using template 3 in the presence of thGTP, CTP, ATP, and UTP but no GTP (Figure 2a, lane 3) yielded full length products, which suggested that thGTP could indeed initiate such transcription reactions. The high incorporation efficiency of the thG modification at an average yield of 91 ± 1% per incorporation demonstrated its structural and functional similarity to G. It is likely, however, that the incorporation yield at positions +1 and +3 is lower than those at positions +6 and +8, due to their proximity to the promoter. Capitalizing on these positive results, the transcription reactions were scaled up to provide large quantities of full length products for analytical characterization. Indeed, MS analysis and enzymatic digestion reactions followed by HPLC-MS analysis further confirmed that thGTP was indeed recognized by T7 RNA polymerase, and efficiently utilized during the initiation and elongation phases (Figure 3). The intense fluorescence of the abortive transcripts provided another positive indication that thGTP was indeed the agent responsible for initiating transcription (Figure 2b).

DNA templates (e.g., 6 and 7), yielding medium RNA transcripts, also demonstrated that thGTP is efficiently incorporated during the initiation and elongation phases. This illustrates that diverse transcript lengths can be formed using thGTP. The thG-E transcript, for example, contains 13 thG incorporations. Much longer transcripts, which include multiple thG residues at the 5′-end, as well as several consecutive thG residues, have also been transcribed in high yields, with an average incorporation yield of 95% per thGTP (see Figure S9). We submit that these observations validate thG as a true isomorphic nucleoside analog of G, which is faithfully recognized by the polymerase, while retaining high selectivity for WC pairing. Although, in principle, multiple alterations within an RNA transcript might be functionally detrimental, the intense emission of these per-modified transcripts suggests potential utility (see below). Additionally, established protocols in RNA biochemistry allow ligations of RNA fragments into larger constructs,40−42 which suggest that short thG-containing RNAs can be ligated to longer native ones for certain applications.

In addition to thGTP being a substrate for T7 RNA polymerase, we tested the fully modified oligonucleotides, specifically thG-S and thG-E, for their ability to function as components in a HH ribozyme, as a prototypical catalytically active RNA. The substrates (S and thG-S) were first radioactively labeled to visualize their ribozyme-mediated cleavage. Incidentally, this successful labeling demonstrates that the 5′-end of the transcript thG-S does not hamper alkaline phosphatase-mediated dephosphorylation and T4 polynucleotide kinase-mediated phosphorylation. These observations are of significance, as they suggest that modifying RNA transcript with thG does not hinder enzymatic transformations by commonly used molecular biological agents.

The unmodified HH enzyme E cleaves its native substrate S and the fully modified one thG-S with similar rates, indicating that replacing all G residues with thG in the HH substrate does not substantially interfere with ribozyme catalysis. This suggests very similar hybridization and folding processes. In contrast, the fully modified HH enzyme thG-E showed very little cleavage ability of either the native substrate S or the corresponding modified thG-S. This suggests that the substitution of G for thG interferes with either the folding or catalysis of the HH enzyme. As the modified substrate is almost fully duplexed and effectively cleaved by the native enzyme, attention is then focused on the relevant residues in the enzyme that are proposed to be involved in catalysis: G8, G10.1, and G12 (Figure 5c). In the proposed ribozyme cleavage mechanism, the N7 of G10.1 coordinates a divalent metal ion,43 which appears to be involved in the phosphodiester cleavage reaction. The lack of the imidazole ring and hence of N7 in thG may therefore explain the severely attenuated catalytic activity of the fully modified enzyme thG-E. Additionally, the nucleobase of G12 is involved in the cleavage reaction where the putatively deprotonated N1 position acts as a base to abstract the proton on the O2′ of C17, which then nucleophilically attacks the adjacent 3′ phosphate, eventually leading to strand cleavage.43,44 Since the pKa of the N1 position of thG within the folded ribozyme likely differs from that of G, this key step could also be hampered. At position G8, the sugar and not the nucleobase is proposed to be involved in catalysis,43,44 making it less likely that modification at this position is directly hindering cleavage.45

Importantly, the cleavage of the modified HH substrate thG-S by the native enzyme E can be observed using steady-state fluorescence spectroscopy, demonstrating the utility of such emissive transcripts for monitoring RNA related processes in real time (Figure 7a and 7c). A significant fraction of the large increase seen in fluorescence intensity likely originates from the cleavage of thG-S by E because inactive combinations (such as that of S and thG-E) exhibit much smaller fluorescence intensity changes (Figure 7b and 7d). We note, however, that changes in emission intensity observed when mixing such fluorescent RNA strands represent multiple events, including the annealing, folding, and Mg2+ coordination, as well as strand cleavage and dissociation. This is supported by the small fluorescence increase seen when the S and thG-E are mixed to generate an inactive HH ribozyme, which likely reflect only conformational changes and metal coordination (Figure 7b and 7d). Notably, however, when the normalized data generated by 32P labeling is compared to the fluorescence-generated rates for thG-S and E, similar overall trends and rates are seen (Figure S6). While these “deficiencies” can likely be circumvented by monitoring the process using a stopped-flow kinetic apparatus (thus separating the fast events from the relatively slow cleavage reaction), we emphasize that monitoring catalytic RNAs using simple benchtop steady-state fluorescence spectrometers can be an effective way to probe substrate cleavage and inhibition.46 It greatly reduces the overall experimental time, and unlike 32P-monitored reactions, which are not monitored in real-time, can provide additional insight into conformational changes, hybridization, and magnesium binding events, among others.

Conclusions

thGTP is found to be accepted by T7 polymerase as a faithful GTP surrogate. This highly isomorphic nucleoside triphosphate can initiate transcription, as well as be incorporated during the elongation phase in short and longer oligonucleotides. Importantly, such modified transcripts, which contain a pppthG at their 5′-end, are also successfully dephosphorylated with alkaline phosphatase and then phosphorylated with T4 polynucleotide kinase, illustrating that other terminus-modifying enzymes tolerate this modification as well. To investigate the impact of thG substitution on RNA function, we tested HH ribozyme combinations where the substrate and enzyme were per-modified with thG. A HH ribozyme containing a fully modified substrate thG-S hybridized to a native enzyme E undergoes efficient phosphodiester bond cleavage that can be monitored either with radioactively labeled substrate followed by PAGE or, in real time, using thG′s fluorescence. In contrast, the fully modified HH enzyme thG-E displayed very little cleavage ability with either S or thG-S.

Our results point to intriguing future implementations of such modified nucleosides. For example, the inactivity of the fully thG modified HH enzyme suggests utility of this nucleoside in probing specific mechanistic questions in RNA catalysis.45 Moreover, due to their reliable hybridization and WC pairing, highly isomorphic but potentially inactive HH constructs could provide useful tools for structural analysis.47 As such, the observation that thGTP is accepted by T7 polymerase as a faithful GTP surrogate (in both its initiation and elongation phases) and that other enzymes, commonly used in molecular biology, accept such per-modified strands as viable substrates opens up numerous creative opportunities to utilize such modified nucleosides and oligonucleotides, both as structural as well as fluorescent tools. We note that no probe provides a universal solution to every biophysical challenge. Even 2-aminopurine, an extensively employed emissive A isoster, fails to perform in certain cases.9,48 We feel, however, that thG can be an extremely useful probe due to its unique structural features and favorable photophysical characteristics.38,39

Experimental Section

Materials

Unmodified DNA oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc. Oligonucleotides were purified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and desalted on Sep-Pak (Waters Corporation). Enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs. NTPs and the ribonuclease inhibitor (RiboLock) were obtained from Fermentas Life Science.

Radiolabeled α-32P ATP (10mCi/mL, 3000 Ci/mmol) and γ-32P ATP (10mCi/mL, 6000 Ci/mmol) were obtained from PerkinElmer. Chemicals for preparing buffer solutions were purchased from Fisher Biotech (enzyme grade). Autoclaved 0.1% DEPC treated water was used in all biochemical reactions and fluorescence titrations.

Instrumentation

NMR spectra were recorded on a Jeol ECA 500 MHz spectrometer. Small molecule mass spectra (MS) were recorded at the University of California, San Diego, Chemistry and Biochemistry Mass Spectrometry Facility, utilizing an Agilent 6230 HR-ESI-TOF mass spectrometer. Reverse-phase HPLC (Vydac C18 column) purification and analysis were carried out using an Agilent 1200 series instrument. Products were lyophilized utilizing a Labconco FreeZone 2.5 freeze dryer.

Polyacrylamide gels containing radiolabeled RNA were analyzed by using a BioRad phosphorimager. Steady-state fluorescence experiments were carried out in a microfluorescence cell (125 μL) with a path length of 1.0 cm (Hellma GmbH & Co. KG, Müllheim, Germany) on a Horiba Jobin Yvon (FluoroMax-3) spectrometer. Mass spectra for oligonuceotides were obtained on a ThermoFinnigan LCQ DECA XP at TriLink Biotechnologies, Inc.

Synthesis of thGTP (2)

Tris(tetrabutylammonium) hydrogen pyrophosphate (0.99 g, 1.1 mmol) in a 10 mL round-bottom flask, and thG30 (60 mg, 0.20 mmol) in a 25 mL round-bottom flask, were separately coevaporated with anhydrous pyridine and dried. Trimethyl phosphate (2 mL) was added to thG and cooled in an ice bath to 0 °C. Phosphoryl chloride (46 μL, 0.5 mmol) was added slowly, and the reaction was stirred for 2 h at 0 °C, resulting in a pinkish brown solution. The coevaporated tris(tetrabutylammonium) hydrogen pyrophosphate was dissolved in 2 mL of anhydrous DMF and added to the thG reaction mixture. Then tributyl amine (0.26 mmol, 1.1 mmol) was added and the reaction was kept stirring at 0 °C for 40 min. To the reaction mixture was added 6 mL of 1 M triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer (TEAB), and the mixture was stirred briefly. The mixture was then transferred to a separatory funnel and washed with 10 mL of EtOAc. The organic layer was then back-extracted with 5 mL of 1 M TEAB. The aqueous layers were combined and concentrated under reduced pressure at room temperature to afford an oily yellow residue. The residue was dissolved in 10 mL of 0.05 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer and loaded onto a DEAE Sephadex A25 anion-exchange column kept in a cold room at 4 °C. The column was eluted using a gradient mixer with 0.05–0.5 M of ammonium bicarbonate buffer. A fraction collector was used to collect 260 fractions that were about 8 mL (220 drops). The fractions containing the triphosphate were evaporated under reduced pressure at 10 °C, and then the residue was lyophilized. To purify the triphosphate further, the residue was run on another DEAE Sephadex A25 anion-exchange column and eluted with 0.06–0.6 M ammonium bicarbonate buffer. After lyophilization, the triphosphate was treated with 25 mg of Chelex 100 for 15 min with occasional shaking, and then filtered. The triphosphate was further purified by HPLC (Phenomenex Synergi Fusion-RP 80A C18 column, 4 μm, 250 × 10 nm, 0–4% acetonitrile in 50 mM TEAB buffer, pH 6.0, 30 min). Appropriate fractions were lyophilized to yield thGTP (0.11g, 13%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O) δ 8.10 (d, J = 4.7 Hz, 1H), 5.16–4.97 (m, 1H), 4.34 (s, 1H), 4.21 (dd, J = 11.5, 9.5 Hz, 4H); 31P NMR (202 MHz, D2O) δ −9.98 (d, J = 20.1 Hz, Pγ), −10.64 (d, J = 18.6 Hz, Pα), −22.64 (t, J = 18.6 Hz, Pβ); HR ESI-MS (negative ion mode) [C11H15N3O14P3S]− calculated 537.9493, found 537.9500; ESI-MS (negative ion mode) [C11H15N3O14P3S]− calculated 538.24, found 537.98 and 559.96 as [M – 2H + Na]−.

Transcription Reactions with α-32P ATP

Single strand DNA templates were annealed to an 18-mer T7 RNA polymerase consensus promoter sequence in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM NaCl, pH 7.8) by heating a 1:1 mixture (10 μM) at 90 °C for 3 min and cooling the solution slowly to room temperature. Transcription reactions were performed in 40 mM Tris-HCl buffer (pH 7.9) containing 500 nM annealed templates, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 10 mM NaCl, 2 mM spermidine, 1 U/μL RNase inhibitor (RiboLock), 1 mM GTP or 1 mM thGTP, 1 mM CTP, 1 mM UTP, 20 μM ATP, 2 μCi α-32P ATP (800 Ci/mmol stock), and 2.5 U/μL T7 RNA polymerase (Fermentas) in a total volume of 20 μL. After 3 h at 37 °C, reactions were quenched by adding 10 μL of loading buffer (7 M urea in 1× TBE with 0.05% bromophenol blue and 0.05% xylene cyanol), heated to 75 °C for 3 min, and 10 μL was loaded onto an analytical 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The products on the gel were analyzed using a phosphorimager. Transcription efficiencies are reported with respect to transcription in the presence of natural nucleotides. Transcription efficiencies were determined from three independent reactions, and the errors reported represent standard deviations.

Large Scale Transcription Reactions for Template 3

To preparatively isolate RNA and for enzymatic digestions large scale transcription reactions using template 3 were performed in a 250 μL reaction volume under similar conditions, with the following changes. The reaction contained 1 mM ATP, CTP, and UTP, 1 mM GTP or thGTP, 15 mM MgCl2, 500 nM template, 1500 units T7 RNA polymerase, and 250 units of Ribolock. After incubation for 5 or 6 h at 37 °C, the precipitated magnesium pyrophosphate was removed by centrifugation. The reaction was quenched by adding 150 μL of loading buffer. The mixture was heated at 75 °C for 3 min and loaded onto a preparative 20% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was UV shadowed; appropriate bands were excised, extracted with 0.5 M ammonium acetate, and desalted on a Sep-Pak column. Concentrations of the RNA transcript were determined using absorption spectroscopy at 260 nm using the following extension coefficients: C, 7200; U, 9900; G; 11500; A, 15400; and thG, 5517 L·mol–1· cm–1.

Large Scale Transcription Reactions for Templates 6 and 7

To preparatively isolate RNA and for enzymatic digestions large scale transcription reactions using template 6 and 7 were performed in a 250 μL reaction volume under similar conditions, with the following changes. The reaction contained 2 mM CTP, UTP, and ATP, 2 mM GTP or thGTP, 20 mM MgCl2, 500 nM template, 6 U/μL (1500 U) T7 RNA polymerase, and 1 U/μL (250 U) of Ribolock. After incubation for 5 or 6 h at 37 °C, the precipitated magnesium pyrophosphate was removed by centrifugation. The reaction was speed-vac to reduce half the volume. Then 125 μL of loading buffer was added. The mixture was heated at 75 °C for 3 min, and loaded onto a preparative 20% or 15% denaturing polyacrylamide gel. The gel was UV shadowed; appropriate bands were excised, extracted with 0.5 M ammonium acetate, and desalted on a Sep-Pak column. Concentrations of the RNA transcript were determined using absorption spectroscopy at 260 nm as described above.

Oligonucleotide Characterization

Digestions

All transcripts (1–2 nmol of 4, 5, S, thG-S, E, thG-E) were incubated with S1 nuclease in reaction buffer (Promega) for 2 h at 37 °C. The reaction was further treated with alkaline phosphatase and dephosphorylation buffer (Promega) for 2 h at 37 °C. The ribonucleoside mixture obtained was analyzed by reverse-phase analytical HPLC with an Agilent column eclipse XDB-C18 (5 μm, 4.6 × 150 mm). Mobile phase: 0–6% acetonitrile (0.1% formic acid) in water (0.1% formic acid) over 12 min; flow rate 1 mL/min.

ESI-MS Spectrometry

Mass spectra as raw data were taken by ESI mass spectrometer in negative ion mode with Xcalibur software version 1.3, and the raw ESI-MS m/z data were deconvoluted by ProMass for Xcalibur Version 2.5 SR-1. The running buffer was 10 mM tert-butylamine in 70% acetonitrile in water. All deconvoluted mass spectra are in Figure S1 and an example of raw m/z data and deconvoluted spectra are shown in Figure S2.

5′ Labeling

The RNA transcripts S and thG-S (12.9 pmol and 12.3 pmol, respectively) in 3 μL of 10× dephosphorylation buffer and 1 μL of calf intestinal alkaline phosphatase in a total volume of 30 μL were incubated at 37 °C for 2 h. Water (70 μL) was added and the reaction mixture extracted with 100 μL of phenol:chloroform (CHCl3):isoamyl alcohol (iAA) = 25:24:1. The water layer was extracted with chloroform (100 μL). The RNA in the aqueous layer was precipitated with 6 μL of glycoblue, 20 μL of 10 M NH4OAc, and 400 μL of EtOH and put in dry ice bath for 1 h, followed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 20 min and removal of the supernatant. The pellet was washed 4× with 50 μL of cold 70% EtOH. The pellet was air-dried for 30 min and then dissolved in 38 μL of water. Five μL of 10× kinase buffer, 1 μL of dithiothreitrol, 5 μL of γ-32P ATP, and 1 μL of T4 polynucleotide kinase, were added and the reaction was heated to 37 °C for 2 h. The RNA was then precipitated (2 μL of glycoblue, 10 μL of 10 M NH4OAc, and 200 μL of EtOH) and washed (×1 with 25 μL of cold 70% EtOH), similar to the above procedure. The pellet was dissolved on 1× TBE 7 M urea loading buffer, and then the RNA was resolved by gel electrophoresis on a denaturing 20% polyacrylamide gel. The RNA was cut out and extracted with water overnight, filtered, and then concentrated using a speed vac.

Ribozyme Reaction Conditions

Cleavage reactions were conducted in a total reaction volume of 34 μL for the natural enzyme (E) and 22 μL for the thG-enzyme (thG-E) with the substrate (S) or thG-substrate (thG-S) for radiography. For the fluorescence-based experiments, a volume of 125 μL total was used. The reactions were carried out at 31 °C in a buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.0) and NaCl (200 mM). Buffered solutions of the substrate (0.6 μM with traces of 5′-32P labeled substrate) and enzyme (6 μM) were denatured separately by heating to 90 °C for 90 s and cooled to room temperature over 10 min to allow for refolding. MgCl2 (to make a final concentration of 10 mM) was added to both the enzyme and substrate, and both were equilibrated at 31 °C for 10 min. The cleavage reaction was then initiated by manually mixing equal volumes of the modified or natural substrate (0.6 μM) with the enzyme or modified enzyme (6 μM) in a heat block at 31 °C, to give final concentrations of 0.3 μM of the substrate and 3 μM of the enzyme and 10 mM MgCl2.

Ribozyme Cleavage Radioactive Assay

For initial data points (time = 0), 2 μL of the substrate was removed immediately prior to starting the reaction. Following initiation of the reaction, 4 μL aliquots were removed at designated time periods and quenched with 12 μL of urea containing loading buffer (7 M urea, 1× TBE, and 0.05% bromophenol blue, and xylene cyanol FF). The tubes were heated to 90 °C for 90 s and loaded on a 20% polyacrylamide with 7 M urea gel. Corresponding bands were quantified on a Personal Molecular Imager and analyzed with Quantity One software (Biorad).

Ribozyme Cleavage Radioactive Data Analysis

Rate constants (k2) were calculated as the slope of ln(1 – S/S0) versus time, where S/S0 is the fraction of cleaved substrate. For experiments utilizing a radioactively labeled substrate, S/S0 was determined by dividing the amount of cleaved substrate by the sum of the full length and cleaved substrates.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the NIH, via grant number GM 069773, for generous support. We thank TriLink BioTechnologies for help with ESI-MS analyses of the RNA transcripts.

Supporting Information Available

Oligonucleotide characterization (enzymatic digestions and ESI-MS of RNA transcripts), PAGE of large scale transcription reactions, absorption and emission spectra of RNA transcripts. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Kuzmine I.; Gottlieb P. A.; Martin C. T. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 2819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy W. P.; Momand J. R.; Yin Y. W. J. Mol. Biol. 2007, 370, 256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlin M.; Ring J. J. Biol. Chem. 1973, 248, 2235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin Y. W.; Steitz T. A. Science 2002, 298, 1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sousa R.; Mukherjee S. Prog. Nucleic Acid Res. Mol. Biol. 2003, 73, 1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan J. F.; Groebe D. R.; Witherell G. W.; Uhlenbeck O. C. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987, 15, 8783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan J. F.; Uhlenbeck O. C. Methods Enzymol. 1989, 180, 51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn J. J.; Studier F. W. J. Mol. Biol. 1983, 166, 477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinkeldam R. W.; Greco N. J.; Tor Y. Chem. Rev. 2010, 110, 2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilhelmsson L. M. Q. Rev. Biophys. 2010, 43, 159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodd D. W.; Hudson R. H. E. Mini-Rev. Org. Chem. 2009, 6, 378. [Google Scholar]

- Rist M. J.; Marino J. P. Curr. Org. Chem. 2002, 6, 775. [Google Scholar]

- Tor Y.; Dervan P. B. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1993, 115, 4461. [Google Scholar]

- Mitsui T.; Kimoto M.; Harada Y.; Yokoyama S.; Hirao L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 8652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai R.; Kimoto M.; Ikeda S.; Mitsui T.; Endo M.; Yokoyama S.; Hirao L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 17286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimoto M.; Hikida Y.; Hirao I. Isr. J. Chem. 2013, 53, 450. [Google Scholar]

- Srivatsan S. G.; Tor Y. Chem.-Asian J. 2009, 4, 419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanpure A. A.; Srivatsan S. G. Chem.—Eur. J. 2011, 17, 12820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawar M. G.; Srivatsan S. G. Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stengel G.; Urban M.; Purse B. W.; Kuchta R. D. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Costa C. P.; Fedor M. J.; Scott L. G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanpure A. A.; Srivatsan S. G. ChemBioChem 2014, 15, 1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson J. R.; Uhlenbeck O. C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1988, 85, 1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes E.; Das S. R. ChemBioChem 2011, 12, 125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G. H.; Lim H. K.; Jung W.; Hah S. S. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2012, 33, 3861. [Google Scholar]

- Huang F. Q.; He J.; Zhang Y. L.; Guo Y. L. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williamson D.; Cann M. J.; Hodgson D. R. W. Chem. Commun. 2007, 5096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiammengo R.; Musilek K.; Jaschke A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 9271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolf J.; Dombos V.; Appel B.; Muller S. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2008, 6, 899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin D.; Sinkeldam R. W.; Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 14912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J. Acta Biochim. Biophys. 1981, 16, 131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M. R.; Sambrook J.; Sambrook J.. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual, 4th ed.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y., 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Hertel K. J.; Herschlag D.; Uhlenbeck O. C. Biochemistry 1994, 33, 3374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirk S. R.; Luedtke N. W.; Tor Y. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2001, 9, 2295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fedor M. J.; Uhlenbeck O. C. Biochemistry 1992, 31, 12042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahba A. S.; Azizi F.; Deleavey G. F.; Brown C.; Robert F.; Carrier M.; Kalota A.; Gewirtz A. M.; Pelletier J.; Hudson R. H. E.; Damha M. J. ACS Chem. Biol. 2011, 6, 912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tor Y. Pure Appl. Chem. 2009, 81, 263. [Google Scholar]

- Liu W.; Shin D.; Tor Y.; Cooperman B. S. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013, 8, 2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A series of short mRNAs, all containing a single thG residue replacing their native G counterparts, have been shown to form an initiation complex, facilitate tRNA binding, allow PRE complex formation, and be “translocation active”. Spectral differences have been seen for different states, which facilitated kinetic analysis of all discrete processes. See ref (38).

- Rieder R.; Lang K.; Graber D.; Micura R. ChemBioChem 2007, 8, 896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Höbartner C.; Rieder R.; Kreutz C.; Puffer B.; Lang K.; Polonskaia A.; Serganov A.; Micura R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005, 127, 12035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang K.; Micura R. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martick M.; Lee T. S.; York D. M.; Scott W. G. Chem. Biol. 2008, 15, 332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han J.; Burke J. M. Biochemistry 2005, 44, 7864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The site-specific modification of individual G residues with their thG surrogates, to study the impact on RNA catalysis, is currently being pursued.

- For a discussion regarding the two photon induced fluorescence of such isomorphic emissive nucleosides and their potential utility for single molecules spectroscopy, see:Lane R. S. K.; Jones R.; Sinkeldam R. W.; Tor Y.; Magennis S. W. ChemPhysChem 2014, 15, 867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- While faithfully pairing with C, thG is lacking the purine’s N7. It thus provides opportunities to explore the involvement of Hoogsteen pairing and N7 participation in higher structure and RNA-based processes.

- Srivatsan S. G.; Tor Y. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.