Abstract

Voltage- and ligand-gated ion channels form the molecular basis of cellular excitability. With >400 members and accounting for ∼1.5% of the human genome, ion channels are some of the most well studied of all proteins in heterologous expression systems. Yet, ion channels often exhibit unexpected properties in vivo because of their interaction with a variety of signaling/scaffolding proteins. Such interactions can influence the function and localization of ion channels, as well as their coupling to intracellular second messengers and pathways, thus increasing the signaling potential of these ion channels in neurons. Moreover, functions have been ascribed to ion channels that are largely independent of their ion-conducting roles. Molecular and functional dissection of the ion channel proteome/interactome has yielded new insights into the composition of ion channel complexes and how their dysregulation leads to human disease.

Introduction

Ion channels are multimeric assemblies consisting of a central ion-conducting pore and a variable number of additional proteins. These channel-interacting proteins (CIPs) may act as obligate subunits in that their only known function is to regulate channel parameters, such as gating, permeation, and/or trafficking to the cell surface or particular subcellular microdomains. Voltage-gated Na+, K+, and Ca2+ channels each associate with one or more non–pore-forming subunits that are structurally and functionally distinct (Li et al., 2006; Buraei and Yang, 2010; Dolphin, 2013; Calhoun and Isom, 2014; Jerng and Pfaffinger, 2014). Other CIPs are common signaling or scaffolding proteins that can influence the function of ion channels and/or their coupling to downstream pathways. For example, A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) tethers cAMP-dependent protein kinase and calcineurin, which can regulate the phosphorylation status, and modulation, of the Cav1 L-type Ca2+ channel (Dittmer et al., 2014; Fuller et al., 2014) and the Kv7 M-type K+ channel (Zhang et al., 2011), as well as the role of Cav1 channels in transcriptional signaling (Zhang and Shapiro, 2012; Murphy et al., 2014). G-protein-coupled receptors represent another class of CIPs that associate with a variety of ion channels, including N-methyl-d-aspartate receptor (NMDAR) glutamate-gated channels. NMDARs associate with D1 and D2 dopamine receptors, which mediate inhibition of NMDAR function in response to D1 and D2 receptor agonists (Lee et al., 2002; Liu et al., 2006).

Genetic variations that disrupt the association of ion channels with CIPs cause a variety of human disorders, such as Liddle syndrome, cardiac arrhythmia, diabetes mellitus, and epilepsy (Jackson and Nicoll, 2011; Kline and Mohler, 2014; Bao and Isom, 2014; O'Malley and Isom, 2014). Moreover, drugs that stabilize CIP/channel interactions are being developed as novel therapeutic strategies (Andersson and Marks, 2010). Therefore, the characterization of the ion channel proteome/interactome has been the subject of intense investigation, requiring an interdisciplinary battery of proteomics, biochemistry, and electrophysiology, combined with the development of new animal models. These studies have greatly expanded our view of ion channels as macromolecular signaling complexes, the constituents of which define the properties and function of these channels in a cell-type-specific manner. Given the wealth of knowledge that has emerged on ion channel-signaling complexes, this review is not meant to be comprehensive but highlights some recent advances in our understanding of CIP/ion channel interactions in the context of neuronal signaling.

Analyzing native ion channels by “functional proteomics”

The comprehensive analysis of ion channels and CIPs in their native cellular environment represents a major challenge. Such analysis ideally requires the intact isolation of the “native” ion channels and the unbiased identification of their constituents. Technical limitations have hampered such strategies, leaving more indirect approaches based on molecular biology (such as expression or siRNA-based cloning and yeast-two-hybrid arrest) or on genetic analysis of distinct (disease-related) phenotypes. However, recent advances in protein biochemistry and, in particular, high-resolution mass spectrometry, have enabled direct access to native ion channels in their microenvironments through unbiased proteomics technologies (for review, see Schulte et al., 2011).

The respective workflow, termed “functional proteomics” (Müller et al., 2010), comprises several distinct experimental steps:

Initially, appropriately solubilized membrane fractions are set up that are prepared from the tissue expressing the channel of interest and finally come as a suspension of inhomogeneous membrane-surrounded vesicles/fragments (Mena et al., 1980). Prepared from brain, these protein fractions are often called “synaptosomal fractions” as they show some enrichment of presynaptic and postsynaptic membranes/proteins, but, important to note, also contain membranes/proteins from cell bodies and dendrites, as well as from the various intracellular membrane compartments (Müller et al., 2010). Solubilization requires careful selection of detergents as they may, in addition to acting as a solvent, destabilize protein–protein interactions and thus perturb the integrity of protein complexes. Consequently, the preservation of higher molecular weight assemblies of the target protein must be assessed, most directly by native gel electrophoresis (Berkefeld et al., 2006; Schwenk et al., 2012).

The channel protein(s) are then extracted from these solubilized membrane fractions by affinity matrices consisting of immobilized antibodies targeting the ion channel of interest, either via the pore-forming α-subunit or tightly associated auxiliary subunits. This step benefits from the use of multiple antibodies recognizing different epitopes because single antibodies may exhibit cross-reactivity to other proteins or may extrude interacting proteins from the target (Schulte et al., 2011). Alternatively, the ion channel complexes may be isolated by native gel electrophoresis and excision of the target-containing gel sections (Schwenk et al., 2012).

The isolated/enriched protein samples are then analyzed by high-resolution nano-flow mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS). This approach provides unbiased information on both the amount (intensity of precursor ions in the MS spectra) and identity of any protein in the sample (via fragmentation resulting in MS/MS spectra resulting from fragmentation). The protein amounts can be quantified by various methods (Beynon et al., 2005; Ong and Mann, 2006; Cox and Mann, 2008; Nanavati et al., 2008; Bildl et al., 2012), of which label-free quantification of MS signals from precursor peptides is favored because of its extended dynamic range of up to as much as four orders of magnitude (Bildl et al., 2012).

Finally, the protein amounts are used to discriminate the proteins that are specifically copurified with the target (ion channel) from background. For this purpose, protein amounts in affinity purifications with the target-specific antibodies are first related to two types of negative controls: affinity purifications with preimmunization immunoglobulins (IgGs) and affinity purifications with the target-specific antibodies from membrane fractions of target knock-out animals. Subsequently, all proteins dubbed specific for any individual target-specific antibody are probed for consistent appearance across all target-specific antibodies to discard all the single “hits” resulting from the particular properties of individual target antibodies. With these criteria of specificity and consistency, one can identify the entire set of proteins that reconstitute a given ion channel in native membranes, termed “proteome” (or sometimes “interactome”) of that particular channel (Müller et al., 2010; Schwenk et al., 2012).

This workflow has been successfully applied to various types of ion channels (Nadal et al., 2003; Berkefeld et al., 2006; Schulte et al., 2006; Marionneau et al., 2009; Schwenk et al., 2009; Zolles et al., 2009; Müller et al., 2010; Schwenk et al., 2012). Of these, glutamate receptors of the AMPA-type (AMPARs) represent an ideal example to demonstrate the benefit of unbiased proteomic analysis for studying architecture and function of ion channels in the context of native cells and/or tissue.

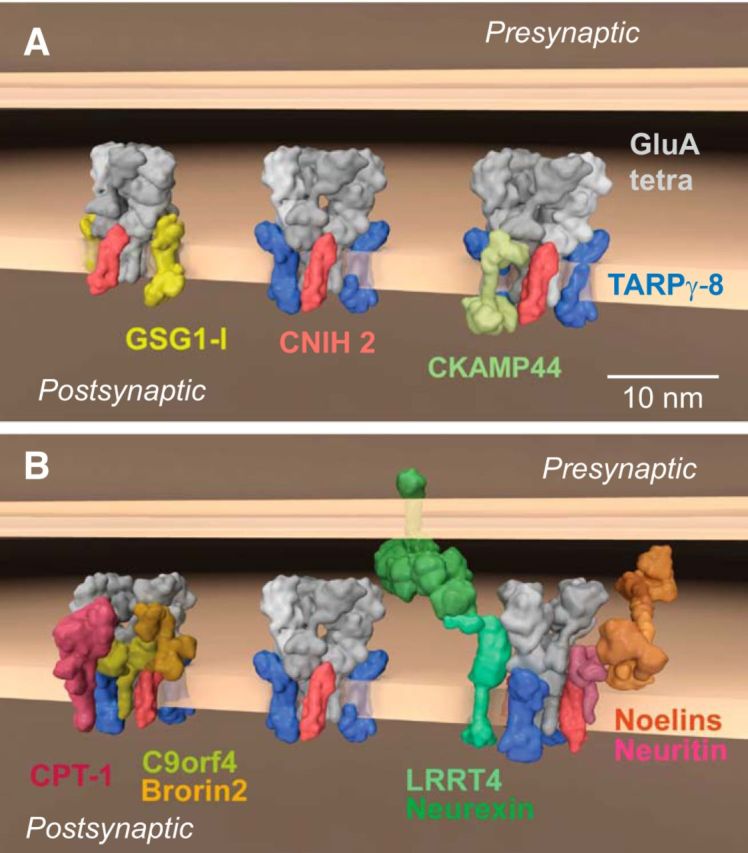

Based on molecular cloning and phenotype analysis, AMPARs were assumed to consist of four GluA proteins and a family of transmembrane AMPAR regulatory proteins (TARPs) (Tomita et al., 2003; Milstein et al., 2007). However, comprehensive proteomic analysis with 10 different antibodies against the four pore-forming GluA proteins identified AMPARs in the rodent brain as macromolecular complexes assembled from a pool of >30 different proteins, mostly transmembrane proteins of different classes and secreted proteins (Schwenk et al., 2012). These findings revealed unanticipated molecular diversity for native AMPARs but also defined some principles behind their assembly. AMPARs exhibit a “layered” architecture, consisting of a defined core and a more variable periphery (Schwenk et al., 2012). The receptor core is formed by tetramers of the pore-forming GluA1–4 proteins (Seeburg, 1993; Hollmann and Heinemann, 1994) and up to four members of three distinct families of membrane proteins that serve as classical auxiliary subunits: TARPs (TARPs, γ-2, γ-3, γ-4, γ-5, γ-7, γ-8), the cornichon homologs 2 and 3 (CNIH2, 3) (Schwenk et al., 2009), and the GSG1-l protein (Fig. 1A) (Schwenk et al., 2012; Shanks et al., 2012). The periphery of the receptors is built from a set of transmembrane and/or soluble proteins that include CKAMPs 44, 52 (von Engelhardt et al., 2010), CPT-1, C9orf 4, Brorin2, Noelins1–3, Neuritin, PRRTs 1,2, and LRRT4 (Siddiqui et al., 2013), as well as four isoforms of the MAGUK family (Schwenk et al., 2012) (Fig. 1A,B).

Figure 1.

Molecular diversity of AMPAR assemblies. A, B, Different macromolecular AMPAR assemblies of distinct subunit composition as identified by functional proteomics in the whole rodent brain (Schwenk et al., 2009, 2012). All proteins are presented as space-filling 3D models that are projected onto the postsynaptic membrane. The models were generated with the Maya platform (Autodesk Maya 3D) (Takamori et al., 2006) using pdb-entries and molecular modeling for the indicated proteins.

The assembly of different proteins within this combinatorial architecture can greatly influence AMPAR function. The inner core largely determines the biophysical properties of the receptor channels, which includes agonist-triggered gating, ion selectivity and permeation, or block by polyamines, and influences their biogenesis, protein processing, and/or trafficking (Chen et al., 2000; Tomita et al., 2005; Bats et al., 2007; Cho et al., 2007; Soto et al., 2007; Schwenk et al., 2009; Soto et al., 2009; Kato et al., 2010; Coombs et al., 2012; Studniarczyk et al., 2013). In heterologous expression experiments, TARPs, CNIHs, and GSG1l (Fig. 1A) impact the gating of the AMPARs, either alone or in combination, by distinctly slowing deactivation and desensitization of various GluA homo-tetramers or hetero-tetramers (Schwenk et al., 2009, 2012). Among those auxiliary subunits, the two CNIH proteins exert the strongest influence, slowing the time constants of either channel-closing process by up to more than fivefold, independent of the GluA composition of the pore (Schwenk et al., 2009; Kato et al., 2010; Coombs et al., 2012). The neurophysiological significance of CNIH2 in prolonging AMPAR currents was demonstrated by the acceleration in the decay of EPSCs upon virus-directed knock-down of CNIH2 in hippocampal mossy cells and, vice versa, by the pronounced slowing of the postsynaptic currents in the neighboring interneurons upon virus-mediated expression of CNIH2 (Boudkkazi et al., 2014). The proteins comprising the periphery of AMPAR influence various aspects of AMPAR function (von Engelhardt et al., 2010) or trafficking (Cantallops et al., 2000; Chen et al., 2000; Zhu et al., 2002; Hussain et al., 2010; Siddiqui et al., 2013). It must be emphasized, however, that many of the physiological implications of the periphery-forming AMPAR constituents are not clear because they currently lack defined primary functions.

Nevertheless, the characterization of the AMPAR proteome will undoubtedly motivate investigations into the function of these proteins and guide future analyses of the molecular mechanisms underlying the observed functional diversity of AMPARs.

CaBPs enhance the functional diversity and cellular regulation of voltage-gated Cav1 Ca2+ channels

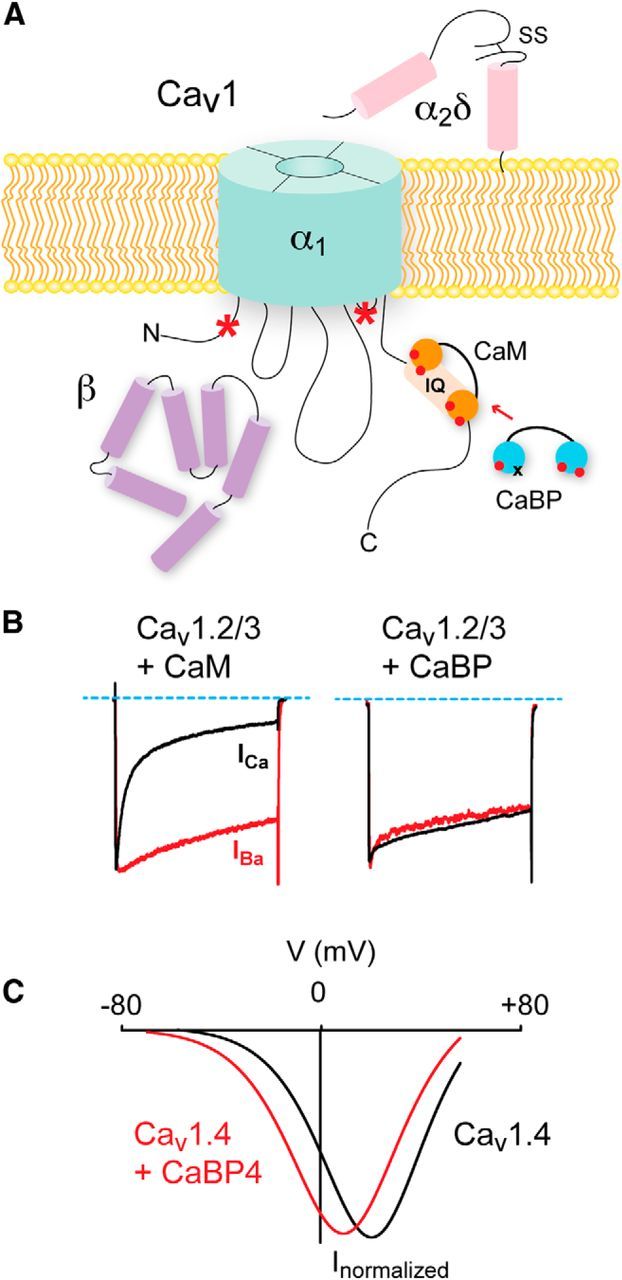

Quantitative proteomic analyses have revealed that voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, like AMPARs, are embedded in complex protein nano-environments (Müller et al., 2010). Cav channels consist of a main pore-forming α1 subunit and an auxiliary Cavβ and α2δ subunit (Fig. 2A), which alter channel activation, inactivation, and/or cell-surface trafficking (Buraei and Yang, 2010; Dolphin, 2013; Simms and Zamponi, 2014). Of the multiple classes of Cav channels that have been characterized, Cav1 Ca2+ channels mediate L-type Ca2+ currents in nerve and muscle. Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 are the most highly expressed Cav1 channels in the brain (Schlick et al., 2010), where they regulate neuronal excitability (Marrion and Tavalin, 1998; Puopolo et al., 2007), activity-dependent gene transcription (Ma et al., 2013), and synaptic plasticity (Moosmang et al., 2005). Cav1.4 and Cav1.3 are the primary Cav1 channels in retinal photoreceptors and cochlear inner hair cells, respectively (Platzer et al., 2000; Brandt et al., 2003; Mansergh et al., 2005).

Figure 2.

Distinct modulation of Cav1 channels by CaM and CaBPs. A, Cav complexes consist minimally of α1, β, and α2δ subunits. CaM and CaBPs bind to the IQ domain, but other CaBP binding sites exist in the N-terminal domain and III-IV linker (*). B, For Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 channels, CDI due to CaM manifests as faster inactivation of Ca2+(ICa) currents compared with Ba2+ currents (left). CaBPs prevent CDI (right). Modified from Zhou et al. (2004). C, Current–voltage relation demonstrating effect of CaBP4 in potentiation of Cav1.4 channels by causing a negative shift in voltage-dependent activation (red trace). Modified from Haeseleer et al. (2004).

Cav1 channels interact with a variety of CIPs (Calin-Jageman and Lee, 2008; Dai et al., 2009), including the EF-hand Ca2+ sensor, calmodulin (CaM). Tethered to a consensus IQ domain in the C-terminal domain of the Cav1 α1 subunit (Fig. 2A), CaM binds incoming Ca2+ ions and initiates conformational changes in the channel protein that underlie Ca2+-dependent inactivation (CDI) (Fig. 2B) (Peterson et al., 1999; Qin et al., 1999; Zühlke et al., 1999; for review, see Ben-Johny and Yue, 2014). In the heart, Ca2+/CaM-driven CDI accelerates the decay of Cav1.2 channel Ca2+ currents, which prevents excessively long cardiac action potentials that can cause arrhythmia (Alseikhan et al., 2002). CDI has also been described for Cav channels in neurons (Budde et al., 2002) and may be neuroprotective in preventing excitotoxic Ca2+ overloads (Nägerl et al., 2000). Multiple factors can influence the extent to which Cav1 channels undergo CDI (Christel and Lee, 2012). In hippocampal neurons, AKAP anchoring of cAMP-dependent protein kinase promotes phosphorylation and potentiation of Cav1 channels. This in turn primes channels to undergo CDI, here due to dephosphorylation by calcineurin associated with the AKAP/Cav1 channel complex (Dittmer et al., 2014).

Other CIPs that play important CDI-modulatory roles are a family of CaM-like Ca2+ binding proteins (CaBPs) that are highly expressed in the brain, retina, and inner ear (Seidenbecher et al., 1998; Haeseleer et al., 2000, 2004; Yang et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2014). Like CaM, CaBPs have 4 EF-hand Ca2+ binding domains, at least one of which is nonfunctional (Haeseleer et al., 2000). In heterologous expression systems, CaBPs inhibit CDI of Cav1.2 and Cav1.3 (Zhou et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2007; Tippens and Lee, 2007) (Fig. 2B). The mechanism likely involves displacement of CaM from the Cav1 α1 IQ domain (Zhou et al., 2004; Findeisen et al., 2013; Oz et al., 2013) (Fig. 2A). However, CaBPs can bind to multiple sites in Cav1 α1, and so, may allosterically modulate CaM interactions with the channel (Zhou et al., 2005; Oz et al., 2011; Yang et al., 2014).

The distinct tissue distribution of CaBP family members suggests that they may regulate different Cav1 channels (Haeseleer et al., 2000, 2004). Alternative splicing produces 3 CaBP1 variants (CaBP1-S, CaBP1-L, and caldendrin), which associate with Cav1.2 channels in the brain (Zhou et al., 2004; Tippens and Lee, 2007). When coexpressed with Cav1.2 in heterologous systems, both CaBP1 and caldendrin strongly suppress CDI, but through slightly different molecular determinants. Although mutations of the IQ domain strongly diminish the impact of both caldendrin and CaBP1, CaBP1 but not caldendrin binds to the N-terminal domain of Cav1.2 α1, and deletion of this N-terminal site inhibits modulation by CaBP1 but not caldendrin (Zhou et al., 2004; Tippens and Lee, 2007). Caldendrin is expressed at higher levels than either CaBP1 variant and, in the frontal cortex, undergoes a developmental increase in expression that parallels the time course of cortical synaptogenesis (Laube et al., 2002; Kim et al., 2014). Caldendrin may be important for prolonging Cav1 Ca2+ signals that promote the formation of dendritic arbors during development (Redmond et al., 2002), although caldendrin also regulates synapse number via NMDA receptor signaling (Dieterich et al., 2008).

In the cochlea, antibodies against CaBP1, CaBP2, CaBP4, and CaBP5 strongly label inner hair cells (Yang et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2007). In transfected HEK293T cells, all four CaBPs inhibit CDI of Cav1.3 channels (Yang et al., 2006; Cui et al., 2007; Schrauwen et al., 2012). Unlike the transient Cav1.3 Ca2+ currents due to CaM-driven CDI, the sustained Cav1.3 Ca2+ currents caused by CaBPs would support tonic glutamate release necessary for sound coding at the inner hair cell ribbon synapse. A mutation that impairs CaBP2 modulation of Cav1.3 CDI causes autosomal recessive hearing loss in humans (Schrauwen et al., 2012), although the phenotype is not as severe as the profound deafness seen in patients with a loss-of function mutation in the CACNA1D gene encoding Cav1.3 α1 (Baig et al., 2011). The presence of other CaBPs may compensate for a deficit in CaBP2 modulation. However, other mechanisms may jointly suppress CDI of Cav1.3 in inner hair cells, such as alternative splicing of Cav1.3 α1 transcripts (Shen et al., 2006) or interactions with other inner hair cell proteins (Gebhart et al., 2010).

In the retina, CaBP4 is highly localized in photoreceptor terminals, where it interacts with the IQ domain of the Cav1.4 α1 subunit (Haeseleer et al., 2004). Unlike Cav1.2 and Cav1.3, Cav1.4 channels undergo little CDI even in the absence of CaBPs. CaM can still bind to the Cav1.4 α1 IQ domain, but this interaction is disrupted by an autoregulatory C-terminal domain (ICDI: inhibitor of CDI). Deletion of the ICDI permits CaM-dependent CDI (Singh et al., 2006; Wahl-Schott et al., 2006), which is then blunted by CaBP4 (Shaltiel et al., 2012). The similar effects of CaBP4 and the ICDI in suppressing CDI are likely due to each competing for occupancy of the IQ domain (Shaltiel et al., 2012). However, a second, and likely the major, effect of CaBP4 is to shift the voltage dependence of activation to more negative voltages (Haeseleer et al., 2004; Shaltiel et al., 2012) (Fig. 2C). This effect of CaBP4 is prevented by deletion of the ICDI (Shaltiel et al., 2012), suggesting that interactions between the ICDI, CaBP4, and the IQ domain are required for modulation of channel gating by CaBP4. Association of Cav1.4 channels with CaBP4 would promote Ca2+ influx at the relatively depolarized membrane potential of photoreceptors in darkness (∼−40 mV). This in turn may enhance the gain of rod photoreceptor synapses by ensuring sufficient activation of postsynaptic metabotropic glutamate receptors and subsequent hyperpolarization of ON rod bipolar cells in darkness. Mice lacking CaBP4 exhibit impaired rod bipolar responses to light stimuli, consistent with loss of function of Cav1.4 (Haeseleer et al., 2004). Moreover, mutations in the CaBP4 gene, which disrupt CaBP4 modulation of Cav1.4, cause vision impairment in humans (Zeitz et al., 2006; Littink et al., 2009; Shaltiel et al., 2012). Together, these studies illustrate the importance of CaBPs as CIPs that can facilitate Cav1 Ca2+ influx in various neuronal cell types.

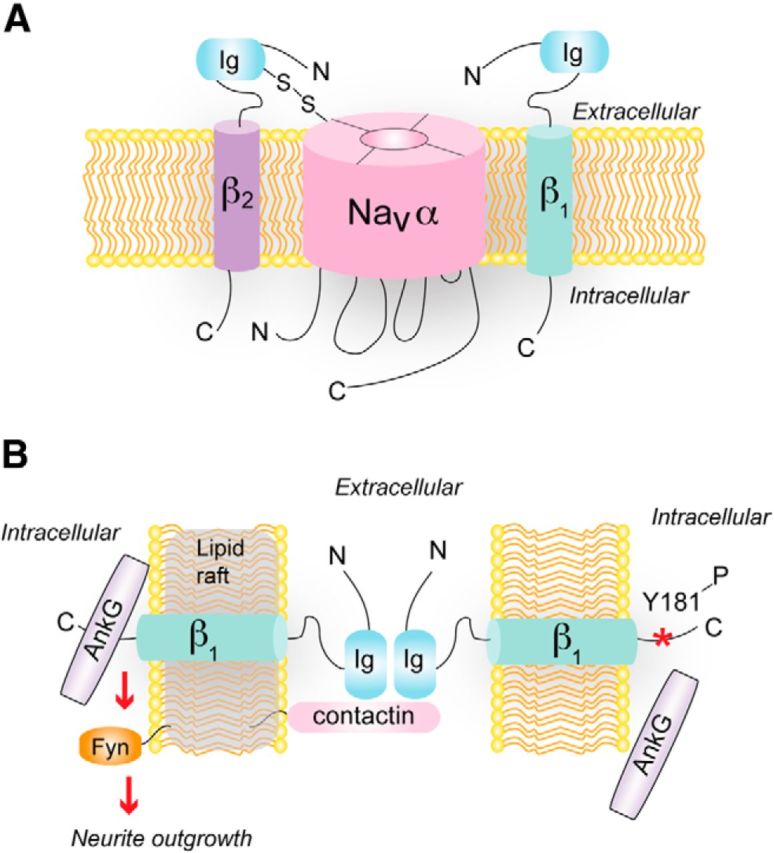

Nav β subunits are multifunctional regulators of neuronal excitability and cell adhesion

Voltage-gated Nav Na+ channels generate the rising phase and propagation of the action potential in excitable cells, including neurons and cardiac myocytes. Like Cav channels, Nav channels are comprised of one pore-forming α subunit (Fig. 3A). The Nav α subunit can associate with one or more β subunits, which are structurally distinct from Cav β subunits (Fig. 3A). Originally characterized as “auxiliary” subunits that solely regulate Nav channel function, Nav β subunits are now known to play essential and diverse roles in a variety of cell types with or without Nav α subunits. The physiological importance of Nav β subunits is illustrated by the numerous and severe disorders linked to mutations in the encoding genes. These include epilepsy (e.g., Dravet Syndrome with sudden unexpected death in epilepsy), cardiac arrhythmia, and sudden infant death syndrome. In addition, changes in Nav β subunit expression are thought to modulate pain, demyelinating and neurodegenerative disorders, cancer, and autism spectrum and mood disorders (O'Malley and Isom, 2014). Five Nav β subunit proteins are encoded by a family of four genes, denoted SCNXB: β1 and its splice variant β1B (SCN1B); β2, β3, and β4 (SCN2B, SCN3B, and SCN4B, respectively) (O'Malley and Isom, 2014).

Figure 3.

Auxiliary and nonauxiliary roles of Navβ subunits. A, One or more β subunits interact with and regulate Nav α subunits. β2 (and β4) are covalently linked, whereas β1 (and β3) are noncovalently linked, to the α subunit. B, Role of Navβ1 in cell adhesion. β1 is localized in lipid rafts with contactin and forms trans-homophilic interactions with other β1 subunits. This is postulated to activate fyn kinase signaling and neurite outgrowth. AnkyrinG (AnkG) is recruited to sites of cell–cell contact through interactions with the C-terminal domain of β1. When a specific tyrosine residue in the β1 C terminus is (Y181, *) phosphorylated (presumably by fyn kinase), AnkG association is inhibited.

In heterologous expression systems, β1 can negatively shift the voltage dependence of Nav channel activation and inactivation, and speed inactivation kinetics (Isom et al., 1992). Although these actions of β1 on Nav properties are subtle in vivo, genetic inactivation of SCN1B severely impairs cellular excitability in the brain and heart (Chen et al., 2004; Lopez-Santiago et al., 2007; Brackenbury et al., 2013). Paradoxically, dorsal root ganglion and cortical neurons from SCN1B null mice are hyperexcitable (Lopez-Santiago et al., 2007; Marionneau et al., 2012; Brackenbury et al., 2013), which may be due to effects of β1 on Kv channels. β1 interacts directly with Kv4.2 A-type K+ channels and increases the cell-surface density of these channels. In layer V cortical pyramidal cells from SCN1B null mice, A-type K+ current density is reduced and repetitive firing is increased (Marionneau et al., 2012). β1 also interacts with Kv4.3 channels in the heart and increases Kv4.3 current density both in cardiac myocytes and transfected HEK293 cells (Deschênes and Tomaselli, 2002; Deschênes et al., 2008). By partnering with either Nav or Kv channels, Nav β subunits can powerfully modulate cellular excitability.

In addition to their role in modulating ion channel function, Nav β subunits act as cell adhesion molecules (CAMs). All five β subunits contain an extracellular immunoglobulin (Ig; Fig. 3A) domain homologous to V-type Ig loop motifs present in the Ig superfamily of CAMs (Isom, 2001). Like other CAMs of the Ig superfamily, β subunits can interact with each other trans-homophilically to induce signaling in adjacent cells (Fig. 3B). In Drosophila S2 cells, exogenously expressed β1 or β2 leads to aggregation of cells and recruitment of ankyrinG at sites of cell–cell contact. AnkyrinG interacts with β subunits and recruitment of ankyrinG to cell–cell contacts, but not cell aggregation, is prevented by deletion of the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of either β subunit and by phosphorylation of tyrosine (Y)181 in this region (Malhotra et al., 2000, 2002) (Fig. 3B). In the heart, phosphorylation of Y181 prevents the interaction of β1 with ankyrin but promotes the interaction of β1 with N-cadherin. Moreover, β1 subunits with phosphorylated Y181 colocalize with N-cadherin at intercalated disks, but not with ankyrin at t-tubules (Malhotra et al., 2004). The intracellular domain of β1 interacts with receptor tyrosine phosphatase β, which regulates the modulatory impact of β1 on Nav channels in transfected tsA-201 cells (Ratcliffe et al., 2000). By opposing phosphorylation of Y181, receptor tyrosine phosphatase β could enhance interactions of β1 with ankyrin, which may dynamically regulate the subcellular localization of Nav channels.

In neurons, the association of Nav β subunits with distinct subsets of proteins determines their subcellular localization and function. At the axon initial segment, Nav β4 is recruited by Nav α subunits through a disulfide linkage formed between Nav α and an extracellular cysteine in β4 (Buffington and Rasband, 2013). Nav β4 mediates resurgent Na+ current, a transient increase in Na+ conductance upon membrane repolarization (Raman and Bean, 1997; Grieco et al., 2005). Because the activity of Nav channels in the axon initial segment regulates action potential generation (Khaliq and Raman, 2006), the targeting of Nav β4 to the axon initial segment should strongly influence neuronal excitability. Consistent with this prediction, siRNA knockdown of SCN4B depresses repetitive firing in cerebellar granule neurons (Bant and Raman, 2010). At nodes of Ranvier, β subunits colocalize with Nav α subunits and are thus positioned to modulate channels during rapid saltatory conduction of action potentials (Chen et al., 2002, 2004). In the paranodal subcompartment adjacent to the nodal gap, β1 interacts with a trimeric complex of axo-glial paranodal proteins consisting of contactin, Caspr, and glial neurofascin-155 (Kazarinova-Noyes et al., 2001; McEwen et al., 2004). The localization of β1 to this subcellular compartment may contribute to the establishment and maintenance of paranodes and formation of the nodal gap: paranodal structure is abnormal in SCN1B null mice, which may contribute to the ataxia observed in these animals (Chen et al., 2004).

In addition to ataxia, SCN1B null mice undergo spontaneous seizures beginning around postnatal day (P)10 (Chen et al., 2004). Before the development of hyperexcitability at P5, SCN1B null mice exhibit defects in neuronal proliferation, migration, and pathfinding (Brackenbury et al., 2013). In cerebellar granule neurons, Nav β1 promotes neurite outgrowth through trans-homophilic interactions (Davis et al., 2004), and this effect requires contactin and the lipid raft-associated tyrosine kinase fyn (Brackenbury et al., 2008) (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, Nav β subunits have been detected in lipid rafts, where they are substrates for sequential cleavage by β- (BACE) and γ-secretases implicated in the pathology of Alzheimer's disease (Wong et al., 2005). These results highlight a key role for Nav β subunits as CAMs required for normal development of neural circuits, as well as multifunctional regulators of ion channels and neuronal excitability in the mature nervous system.

Interactions of K+ channels with cytoplasmic signaling pathways

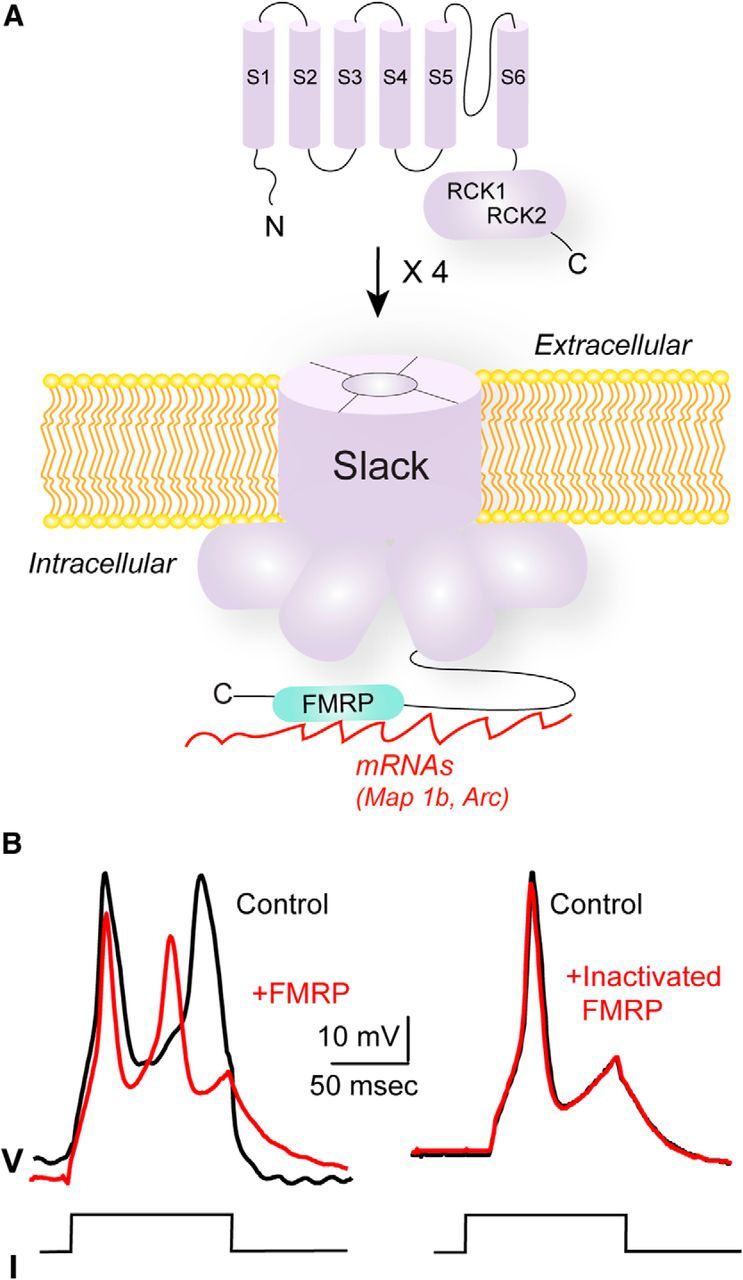

Within the ion channel superfamily, K+ channels are the most diverse at the molecular level, with >80 genes encoding K+ channel α subunits. In contrast to the single polypeptide forming the pore of Nav and Cav channels, functional K+ channels are comprised of homomers or heteromers of four α subunits (Fig. 4A; two in the case of the K2P subfamily). This diversity is unlikely to represent functional redundancy and suggests that different members of the K+ channel family have roles that go beyond simply regulating K+ flux across the plasma membrane.

Figure 4.

Interaction of the Slack Na+-activated K+ channel with FMRP. A, Slack subunits have six transmembrane domains (S1–S6); four of these subunits form the channel. The bulk of the channel protein resides in the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of each subunit (solid and dashed lines), which contains two regulator of K+ conductance domains (RCK1, RCK2). FMRP and its target RNAs interact with the C-terminal domain of Slack. B, Injection of FMRP(1–298) hyperpolarizes membrane potential in Aplysia neurons. Representative traces of the effect of injection of FMRP(1–298) or heat-inactivated FMRP(1–298) on action potentials of Aplysia bag cell neurons. Action potentials were evoked by injecting 0.6 nA current pulses. Modified from Zhang et al. (2012).

A variety of studies have shown that K+ channels interact directly with cytoplasmic and cytoskeletal proteins and that the gating of channels can trigger cytoplasmic signaling even when ion flux through the pore of the channel has been eliminated (Kaczmarek, 2006). Some subfamilies of voltage-gated Kv K+ channels have their own classes of auxiliary subunits (Li et al., 2006). These subunits are not required for ion permeation but regulate trafficking and gating and may be required for modulation of the channels by protein kinases or other signaling pathways (Vacher and Trimmer, 2011). For example, the pore-forming α-subunits of Kv1 channels interact with one of three Kv β subunits. Two of these are functional aldo-keto reductases that use NADPH as a cofactor. Activation of these attached enzymes directly regulates inactivation and amplitude of Kv1 currents. Moreover, direct phosphorylation of the Kv β subunits is required for appropriate trafficking and targeting of these channels to axons (Vacher and Trimmer, 2011).

In some cases, Kv channel auxiliary subunits mediate interactions with other ion channels. For example, Ca2+-activated BK K+ channels form complexes with Cav Ca2+ channels (Berkefeld et al., 2006). Cav channels can also interact with Kv channels via the Kv auxiliary subunits. KChiPs are members of a family of neuronal Ca2+-binding proteins that interact with Kv4 channels and regulate their voltage dependence of inactivation (Li et al., 2006; Vacher and Trimmer, 2011). In some neurons, KChiPs exist in ternary complex with Kv4.2 K+ channels and Cav3 T-type Ca2+ channels (Anderson et al., 2010). These Kv/Cav channel complexes would allow for precise timing of neuronal hyperpolarization following depolarization, due to very local regulation of Kv channels by Ca2+ that enters through the pore of the Cav channel.

Na+-activated K+ channels represent an additional class of K+ channels that shape the excitability of neurons in the CNS and are encoded by the Slack and Slick genes (also termed Slo2.2 and Slo2.1, or KCNT1 and KCNT2, respectively) (Joiner et al., 1998; Yuan et al., 2003; Bhattacharjee et al., 2005). The fact that the C-terminal cytoplasmic domains of these channels are particularly large prompted a search for cytoplasmic proteins that may interact with these domains. At least one such interacting protein is the Fragile X Mental Retardation Protein (FMRP; Fig. 4A) (Brown et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2012).

FMRP is an RNA-binding protein that is required for some forms of activity-dependent protein translation within neurons and may be particularly important for local translation in dendrites or compartments other than the soma (Bassell and Warren, 2008). Loss of FMRP results in Fragile X syndrome, the most common inherited form of intellectual disability in humans. This condition is also associated with hypersensitivity to sensory stimuli, particularly auditory stimuli, and with an increased incidence of epilepsy during childhood (10%–18%). Interactions between FMRP and the cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of Slack have been demonstrated by yeast two-hybrid and coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Brown et al., 2010). FMRP also interacts with two other ion channels, BK K+ channels (Deng et al., 2013) and CaV2.2 (N-type) Ca2+ channels (Ferron et al., 2014).

The association of Slack with FMRP links the C terminus of the channel directly to mRNAs encoding proteins, such as Map1b and Arc, which are targets of FMRP (Fig. 4A). In brains from wild-type mice, but not those from Fmr1−/y mice that lack FMRP, these mRNAs can be coimmunoprecipitated with Slack channels (Brown et al., 2010). The Slack/FMRP interaction leads to a reversible activation of channel activity. Application of a recombinant fragment of FMRP(1–298) that includes most of the known FMRP protein–protein interaction domains to excised inside-out patches containing Slack channels causes a twofold to threefold increase in channel activity. This effect has been observed both for Slack channels expressed heterologously in Xenopus oocytes (Brown et al., 2010) and for native Na+-activated K+ channels in the bag cell neurons of Aplysia, where injection of FMRP produces a hyperpolarization of the membrane (Fig. 4B) (Zhang et al., 2012). A second effect of FMRP on the gating of Slack channels in both preparations is to largely eliminate subconductance states, which are readily detected before application of FMRP(1–298). No effect of FMRP(1–298) was detected on functional Slack channels that were truncated at their distal C terminus, the putative site of channel–FMRP interaction (Brown et al., 2010).

Slack and Slick are very widely expressed in central neurons (Bhattacharjee et al., 2002, 2005), and Na+-activated K+ currents have been characterized in a wide variety of neurons (Bhattacharjee et al., 2005; Kaczmarek, 2013). Suppression of Slack expression using siRNA techniques can reduce a major component of total K+ current in several neuronal types (Budelli et al., 2009; Lu et al., 2010). One neuronal type that expresses Slack and in which the characteristics of the native Na+-activated K+ channels have been compared with those of Slack channels in heterologous expression systems is the principal neuron of the medial nucleus of the trapezoid body (Yang et al., 2007). These neurons fire at high rates with high temporal accuracy and are a component of the brainstem circuitry that determines the location of sounds in space (Kaczmarek et al., 2005). Increasing the level of Na+-activated K+ current in medial nucleus of the trapezoid body neurons in brainstem slices increases the temporal accuracy with which action potentials lock to stimulus pulses (Yang et al., 2007). The level of Na+-activated K+ current in medial nucleus of the trapezoid body neurons from Fmr1−/y mice is substantially reduced compared with that in neurons from wild-type animal, whereas no change in levels of Slack channels can be detected (Brown et al., 2010). This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that the interaction of Slack with FMRP in native neurons serves to enhance Na+-activated K+ current amplitude.

The interaction of an ion channel with part of the biochemical machinery that regulates translation of mRNAs suggests that changes in channel activity may contribute to the regulation of activity-dependent protein synthesis in neurons. Experiments testing this hypothesis are in progress. Circumstantial support for a role for Slack channels in the development of normal intellectual function has come, however, from the characterization of human mutations in the Slack gene (Barcia et al., 2012; Heron et al., 2012; Ishii et al., 2013; McTague et al., 2013; Martin et al., 2014; Milligan et al., 2014). Different mutations produce one of three types of seizures that occur in infancy or childhood: (1) malignant migrating partial seizures of infancy, (2) autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy, and (3) Ohtahara syndrome. Most of the mutations are in the large cytoplasmic C-terminal domain of Slack. The mutant channels conduct K+ currents that are significantly greater than those of wild-type channels (Barcia et al., 2012; Martin et al., 2014; Milligan et al., 2014). In single-channel analysis, the mutant channels behave like channels that are constitutively activated by FMRP in that subconductance states are strongly suppressed or absent (Barcia et al., 2012).

Each of the human Slack mutations is associated with very severe intellectual disability and developmental delay (Kim and Kaczmarek, 2014). It is possible that these are a consequence of the abnormal electrical activity that occurs during the seizures. Nevertheless, the finding that autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy can be caused by mutations either in the neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor or in Slack channels, but that intellectual disability only occurs for the Slack channel mutations (Heron et al., 2012), suggests that the disruption of the C-terminal protein–protein interactions of Slack with cytoplasmic signaling molecules contributes to the intellectual disability.

Perspectives

The encoding of information by patterns of neural activity demands that ion channel signaling exhibits a high degree of spatial and temporal precision. Molecular dissection of the ion channel proteome and detailed analyses of the functional impact of ion channel-associated proteins have greatly expanded our understanding of how such precision may be achieved. Moving forward, it will be important to consider that channel-interacting proteins may transform the biophysical features of ion channels in ways that could influence their pharmacological properties, as ion channels are major drug targets. Acknowledging that ion channels and their interacting proteins may have nonconducting roles, we may discover new and unexpected mechanisms by which disease-causing mutations lead to channelopathies. Finally, the potential of mapping ion channel proteomes in different neurons, and at distinct developmental time points, offers new perspectives on how ion channel regulation may be tailored to generate and maintain synapses and circuits.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DC009433 and NS084190 to A.L., HD067517 and DC01919 to L.K.K., and NS064245 and NS076752 to L.L.I., a Carver Research Program of Excellence Award to A.L., the University of Michigan Center for Organogenesis to L.L.I., FRAXA Grant to L.K.K., and Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft SFB 746, Fa 332/9-1 and Swiss National Fund CRSII3-136210/1 to B.F.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Alseikhan BA, DeMaria CD, Colecraft HM, Yue DT. Engineered calmodulins reveal the unexpected eminence of Ca2+ channel inactivation in controlling heart excitation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17185–17190. doi: 10.1073/pnas.262372999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson D, Mehaffey WH, Iftinca M, Rehak R, Engbers JD, Hameed S, Zamponi GW, Turner RW. Regulation of neuronal activity by Cav3-Kv4 channel signaling complexes. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:333–337. doi: 10.1038/nn.2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson DC, Marks AR. Fixing ryanodine receptor Ca leak: a novel therapeutic strategy for contractile failure in heart and skeletal muscle. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2010;7:e151–e157. doi: 10.1016/j.ddmec.2010.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baig SM, Koschak A, Lieb A, Gebhart M, Dafinger C, Nürnberg G, Ali A, Ahmad I, Sinnegger-Brauns MJ, Brandt N, Engel J, Mangoni ME, Farooq M, Khan HU, Nürnberg P, Striessnig J, Bolz HJ. Loss of Cav1.3 (CACNA1D) function in a human channelopathy with bradycardia and congenital deafness. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:77–84. doi: 10.1038/nn.2694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bant JS, Raman IM. Control of transient, resurgent, and persistent current by open-channel block by Na channel beta4 in cultured cerebellar granule neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:12357–12362. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005633107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Isom LL. NaV1.5 and regulatory β subunits in cardiac sodium channelopathies. Cardiac Electrophysiol Clin. 2014 doi: 10.1016/j.ccep.2014.07.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barcia G, Fleming MR, Deligniere A, Gazula VR, Brown MR, Langouet M, Chen H, Kronengold J, Abhyankar A, Cilio R, Nitschke P, Kaminska A, Boddaert N, Casanova JL, Desguerre I, Munnich A, Dulac O, Kaczmarek LK, Colleaux L, Nabbout R. De novo gain-of-function KCNT1 channel mutations cause malignant migrating partial seizures of infancy. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1255–1259. doi: 10.1038/ng.2441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassell GJ, Warren ST. Fragile X syndrome: loss of local mRNA regulation alters synaptic development and function. Neuron. 2008;60:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bats C, Groc L, Choquet D. The interaction between Stargazin and PSD-95 regulates AMPA receptor surface trafficking. Neuron. 2007;53:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Johny M, Yue DT. Calmodulin regulation (calmodulation) of voltage-gated calcium channels. J Gen Physiol. 2014;143:679–692. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkefeld H, Sailer CA, Bildl W, Rohde V, Thumfart JO, Eble S, Klugbauer N, Reisinger E, Bischofberger J, Oliver D, Knaus HG, Schulte U, Fakler B. BKCa-Cav channel complexes mediate rapid and localized Ca2+-activated K+ signaling. Science. 2006;314:615–620. doi: 10.1126/science.1132915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beynon RJ, Doherty MK, Pratt JM, Gaskell SJ. Multiplexed absolute quantification in proteomics using artificial QCAT proteins of concatenated signature peptides. Nat Methods. 2005;2:587–589. doi: 10.1038/nmeth774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A, Gan L, Kaczmarek LK. Localization of the Slack potassium channel in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2002;454:241–254. doi: 10.1002/cne.10439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee A, von Hehn CA, Mei X, Kaczmarek LK. Localization of the Na+-activated K+ channel Slick in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2005;484:80–92. doi: 10.1002/cne.20462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bildl W, Haupt A, Müller CS, Biniossek ML, Thumfart JO, Huber B, Fakler B, Schulte U. Extending the dynamic range of label-free mass spectrometric quantification of affinity purifications. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11:M111007955. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M111.007955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudkkazi S, Brechet A, Schwenk J, Fakler B. Cornichon2 dictates the time course of excitatory transmission at individual hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 2014;82:848–858. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury WJ, Davis TH, Chen C, Slat EA, Detrow MJ, Dickendesher TL, Ranscht B, Isom LL. Voltage-gated Na+ channel beta1 subunit-mediated neurite outgrowth requires Fyn kinase and contributes to postnatal CNS development in vivo. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3246–3256. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5446-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brackenbury WJ, Yuan Y, O'Malley HA, Parent JM, Isom LL. Abnormal neuronal patterning occurs during early postnatal brain development of Scn1b-null mice and precedes hyperexcitability. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:1089–1094. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208767110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandt A, Striessnig J, Moser T. CaV1.3 channels are essential for development and presynaptic activity of cochlear inner hair cells. J Neurosci. 2003;23:10832–10840. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-34-10832.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MR, Kronengold J, Gazula VR, Chen Y, Strumbos JG, Sigworth FJ, Navaratnam D, Kaczmarek LK. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls gating of the sodium-activated potassium channel Slack. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:819–821. doi: 10.1038/nn.2563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budde T, Meuth S, Pape HC. Calcium-dependent inactivation of neuronal calcium channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:873–883. doi: 10.1038/nrn959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Budelli G, Hage TA, Wei A, Rojas P, Jong YJ, O'Malley K, Salkoff L. Na+-activated K+ channels express a large delayed outward current in neurons during normal physiology. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:745–750. doi: 10.1038/nn.2313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buffington SA, Rasband MN. Na+ channel-dependent recruitment of Navbeta4 to axon initial segments and nodes of Ranvier. J Neurosci. 2013;33:6191–6202. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4051-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buraei Z, Yang J. The β subunit of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:1461–1506. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00057.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun JD, Isom LL. The role of non-pore-forming beta subunits in physiology and pathophysiology of voltage-gated sodium channels. Handb Exp Pharmacol. 2014;221:51–89. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-41588-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calin-Jageman I, Lee A. Cav1 L-type Ca2+ channel signaling complexes in neurons. J Neurochem. 2008;105:573–583. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantallops I, Haas K, Cline HT. Postsynaptic CPG15 promotes synaptic maturation and presynaptic axon arbor elaboration in vivo. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1004–1011. doi: 10.1038/79823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Bharucha V, Chen Y, Westenbroek RE, Brown A, Malhotra JD, Jones D, Avery C, Gillespie PJ, 3rd, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Kazarinova-Noyes K, Shrager P, Saunders TL, Macdonald RL, Ransom BR, Scheuer T, Catterall WA, Isom LL. Reduced sodium channel density, altered voltage dependence of inactivation, and increased susceptibility to seizures in mice lacking sodium channel beta 2-subunits. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17072–17077. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212638099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Westenbroek RE, Xu X, Edwards CA, Sorenson DR, Chen Y, McEwen DP, O'Malley HA, Bharucha V, Meadows LS, Knudsen GA, Vilaythong A, Noebels JL, Saunders TL, Scheuer T, Shrager P, Catterall WA, Isom LL. Mice lacking sodium channel beta1 subunits display defects in neuronal excitability, sodium channel expression, and nodal architecture. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4030–4042. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4139-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Chetkovich DM, Petralia RS, Sweeney NT, Kawasaki Y, Wenthold RJ, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. Stargazin regulates synaptic targeting of AMPA receptors by two distinct mechanisms. Nature. 2000;408:936–943. doi: 10.1038/35050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho CH, St-Gelais F, Zhang W, Tomita S, Howe JR. Two families of TARP isoforms that have distinct effects on the kinetic properties of AMPA receptors and synaptic currents. Neuron. 2007;55:890–904. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christel C, Lee A. Ca2+-dependent modulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2012;1820:1243–1252. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2011.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coombs ID, Soto D, Zonouzi M, Renzi M, Shelley C, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Cornichons modify channel properties of recombinant and glial AMPA receptors. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9796–9804. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0345-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008;26:1367–1372. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui G, Meyer AC, Calin-Jageman I, Neef J, Haeseleer F, Moser T, Lee A. Ca2+-binding proteins tune Ca2+ feedback to Cav1.3 channels in auditory hair cells. J Physiol. 2007;585:791–803. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.142307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai S, Hall DD, Hell JW. Supramolecular assemblies and localized regulation of voltage-gated ion channels. Physiol Rev. 2009;89:411–452. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00029.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis TH, Chen C, Isom LL. Sodium channel beta1 subunits promote neurite outgrowth in cerebellar granule neurons. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:51424–51432. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410830200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng PY, Rotman Z, Blundon JA, Cho Y, Cui J, Cavalli V, Zakharenko SS, Klyachko VA. FMRP regulates neurotransmitter release and synaptic information transmission by modulating action potential duration via BK channels. Neuron. 2013;77:696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes I, Tomaselli GF. Modulation of Kv4.3 current by accessory subunits. FEBS Lett. 2002;528:183–188. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(02)03296-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deschênes I, Armoundas AA, Jones SP, Tomaselli GF. Post-transcriptional gene silencing of KChIP2 and Navbeta1 in neonatal rat cardiac myocytes reveals a functional association between Na and Ito currents. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2008;45:336–346. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2008.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dieterich DC, Karpova A, Mikhaylova M, Zdobnova I, König I, Landwehr M, Kreutz M, Smalla KH, Richter K, Landgraf P, Reissner C, Boeckers TM, Zuschratter W, Spilker C, Seidenbecher CI, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED, Kreutz MR. Caldendrin-Jacob: a protein liaison that couples NMDA receptor signalling to the nucleus. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e34. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer PJ, Dell'Acqua ML, Sather WA. Ca2+/calcineurin-dependent inactivation of neuronal L-type Ca2+ channels requires priming by AKAP-anchored protein kinase A. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1410–1416. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolphin AC. The α2δ subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2013;1828:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferron L, Nieto-Rostro M, Cassidy JS, Dolphin AC. Fragile X mental retardation protein controls synaptic vesicle exocytosis by modulating N-type calcium channel density. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3628. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Findeisen F, Rumpf CH, Minor DL., Jr Apo states of calmodulin and CaBP1 control CaV1 voltage-gated calcium channel function through direct competition for the IQ domain. J Mol Biol. 2013;425:3217–3234. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2013.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller MD, Fu Y, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. Differential regulation of CaV1.2 channels by cAMP-dependent protein kinase bound to A-kinase anchoring proteins 15 and 79/150. J Gen Physiol. 2014;143:315–324. doi: 10.1085/jgp.201311075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhart M, Juhasz-Vedres G, Zuccotti A, Brandt N, Engel J, Trockenbacher A, Kaur G, Obermair GJ, Knipper M, Koschak A, Striessnig J. Modulation of Cav1.3 Ca2+ channel gating by Rab3 interacting molecule. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2010;44:246–259. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieco TM, Malhotra JD, Chen C, Isom LL, Raman IM. Open-channel block by the cytoplasmic tail of sodium channel beta4 as a mechanism for resurgent sodium current. Neuron. 2005;45:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Sokal I, Verlinde CL, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pronin AN, Benovic JL, Fariss RN, Palczewski K. Five members of a novel Ca2+-binding protein (CABP) subfamily with similarity to calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:1247–1260. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.2.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haeseleer F, Imanishi Y, Maeda T, Possin DE, Maeda A, Lee A, Rieke F, Palczewski K. Essential role of Ca2+-binding protein 4, a Cav1.4 channel regulator, in photoreceptor synaptic function. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:1079–1087. doi: 10.1038/nn1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heron SE, Smith KR, Bahlo M, Nobili L, Kahana E, Licchetta L, Oliver KL, Mazarib A, Afawi Z, Korczyn A, Plazzi G, Petrou S, Berkovic SF, Scheffer IE, Dibbens LM. Missense mutations in the sodium-gated potassium channel gene KCNT1 cause severe autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1188–1190. doi: 10.1038/ng.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann M, Heinemann S. Cloned glutamate receptors. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:31–108. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.000335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussain NK, Hsin H, Huganir RL, Sheng M. MINK and TNIK differentially act on Rap2-mediated signal transduction to regulate neuronal structure and AMPA receptor function. J Neurosci. 2010;30:14786–14794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4124-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii A, Shioda M, Okumura A, Kidokoro H, Sakauchi M, Shimada S, Shimizu T, Osawa M, Hirose S, Yamamoto T. A recurrent KCNT1 mutation in two sporadic cases with malignant migrating partial seizures in infancy. Gene. 2013;531:467–471. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.08.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom LL. Sodium channel beta subunits: anything but auxiliary. Neuroscientist. 2001;7:42–54. doi: 10.1177/107385840100700108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isom LL, De Jongh KS, Patton DE, Reber BF, Offord J, Charbonneau H, Walsh K, Goldin AL, Catterall WA. Primary structure and functional expression of the b1 subunit of the rat brain sodium channel. Science. 1992;256:839–842. doi: 10.1126/science.1375395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson AC, Nicoll RA. The expanding social network of ionotropic glutamate receptors: TARPs and other transmembrane auxiliary subunits. Neuron. 2011;70:178–199. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jerng HH, Pfaffinger PJ. Modulatory mechanisms and multiple functions of somatodendritic A-type K (+) channel auxiliary subunits. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:82. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joiner WJ, Tang MD, Wang LY, Dworetzky SI, Boissard CG, Gan L, Gribkoff VK, Kaczmarek LK. Formation of intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels by interaction of Slack and Slo subunits. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:462–469. doi: 10.1038/2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek LK. Non-conducting functions of voltage-gated ion channels. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7:761–771. doi: 10.1038/nrn1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek LK. Slack, slick and sodium-activated potassium channels. ISRN Neurosci. 2013;2013 doi: 10.1155/2013/354262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek LK, Bhattacharjee A, Desai R, Gan L, Song P, von Hehn CA, Whim MD, Yang B. Regulation of the timing of MNTB neurons by short-term and long-term modulation of potassium channels. Hear Res. 2005;206:133–145. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato AS, Gill MB, Ho MT, Yu H, Tu Y, Siuda ER, Wang H, Qian YW, Nisenbaum ES, Tomita S, Bredt DS. Hippocampal AMPA receptor gating controlled by both TARP and cornichon proteins. Neuron. 2010;68:1082–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.11.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazarinova-Noyes K, Malhotra JD, McEwen DP, Mattei LN, Berglund EO, Ranscht B, Levinson SR, Schachner M, Shrager P, Isom LL, Xiao ZC. Contactin associates with Na+ channels and increases their functional expression. J Neurosci. 2001;21:7517–7525. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-19-07517.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khaliq ZM, Raman IM. Relative contributions of axonal and somatic Na channels to action potential initiation in cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1935–1944. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4664-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim GE, Kaczmarek LK. Emerging role of the KCNT1 Slack channel in intellectual disability. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:209. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KY, Scholl ES, Liu X, Shepherd A, Haeseleer F, Lee A. Localization and expression of CaBP1/caldendrin in the mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2014;268:33–47. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline CF, Mohler PJ. Defective interactions of protein partner with ion channels and transporters as alternative mechanisms of membrane channelopathies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1838:723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2013.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laube G, Seidenbecher CI, Richter K, Dieterich DC, Hoffmann B, Landwehr M, Smalla KH, Winter C, Böckers TM, Wolf G, Gundelfinger ED, Kreutz MR. The neuron-specific Ca2+-binding protein caldendrin: gene structure, splice isoforms, and expression in the rat central nervous system. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;19:459–475. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2001.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee FJ, Xue S, Pei L, Vukusic B, Chéry N, Wang Y, Wang YT, Niznik HB, Yu XM, Liu F. Dual regulation of NMDA receptor functions by direct protein–protein interactions with the dopamine D1 receptor. Cell. 2002;111:219–230. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(02)00962-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Um SY, McDonald TV. Voltage-gated potassium channels: regulation by accessory subunits. Neuroscientist. 2006;12:199–210. doi: 10.1177/1073858406287717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littink KW, van Genderen MM, Collin RW, Roosing S, de Brouwer AP, Riemslag FC, Venselaar H, Thiadens AA, Hoyng CB, Rohrschneider K, den Hollander AI, Cremers FP, van den Born LI. A novel homozygous nonsense mutation in CABP4 causes congenital cone-rod synaptic disorder. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2009;50:2344–2350. doi: 10.1167/iovs.08-2553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu XY, Chu XP, Mao LM, Wang M, Lan HX, Li MH, Zhang GC, Parelkar NK, Fibuch EE, Haines M, Neve KA, Liu F, Xiong ZG, Wang JQ. Modulation of D2R–NR2B interactions in response to cocaine. Neuron. 2006;52:897–909. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Santiago LF, Meadows LS, Ernst SJ, Chen C, Malhotra JD, McEwen DP, Speelman A, Noebels JL, Maier SK, Lopatin AN, Isom LL. Sodium channel Scn1b null mice exhibit prolonged QT and RR intervals. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:636–647. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.07.062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Das P, Fadool DA, Kaczmarek LK. The slack sodium-activated potassium channel provides a major outward current in olfactory neurons of Kv1.3−/− super-smeller mice. J Neurophysiol. 2010;103:3311–3319. doi: 10.1152/jn.00607.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Cohen S, Li B, Tsien RW. Exploring the dominant role of Cav1 channels in signalling to the nucleus. Biosci Rep. 2013;33:97–101. doi: 10.1042/BSR20120099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Kazen-Gillespie K, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Sodium channel beta subunits mediate homophilic cell adhesion and recruit ankyrin to points of cell–cell contact. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:11383–11388. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.15.11383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Koopmann MC, Kazen-Gillespie KA, Fettman N, Hortsch M, Isom LL. Structural requirements for interaction of sodium channel beta 1 subunits with ankyrin. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:26681–26688. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202354200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra JD, Thyagarajan V, Chen C, Isom LL. Tyrosine-phosphorylated and nonphosphorylated sodium channel beta1 subunits are differentially localized in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40748–40754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407243200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mansergh F, Orton NC, Vessey JP, Lalonde MR, Stell WK, Tremblay F, Barnes S, Rancourt DE, Bech-Hansen NT. Mutation of the calcium channel gene Cacna1f disrupts calcium signaling, synaptic transmission and cellular organization in mouse retina. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:3035–3046. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marionneau C, LeDuc RD, Rohrs HW, Link AJ, Townsend RR, Nerbonne JM. Proteomic analyses of native brain K(V)4.2 channel complexes. Channels (Austin) 2009;3:284–294. doi: 10.4161/chan.3.4.9553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marionneau C, Carrasquillo Y, Norris AJ, Townsend RR, Isom LL, Link AJ, Nerbonne JM. The sodium channel accessory subunit Navbeta1 regulates neuronal excitability through modulation of repolarizing voltage-gated K(+) channels. J Neurosci. 2012;32:5716–5727. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6450-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrion NV, Tavalin SJ. Selective activation of Ca2+-activated K+ channels by co-localized Ca2+ channels in hippocampal neurons. Nature. 1998;395:900–905. doi: 10.1038/27674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin HC, Kim GE, Pagnamenta AT, Murakami Y, Carvill GL, Meyer E, Copley RR, Rimmer A, Barcia G, Fleming MR, Kronengold J, Brown MR, Hudspith KA, Broxholme J, Kanapin A, Cazier JB, Kinoshita T, Nabbout R, Nabbout R, Bentley D, et al. Clinical whole-genome sequencing in severe early-onset epilepsy reveals new genes and improves molecular diagnosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:3200–3211. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen DP, Meadows LS, Chen C, Thyagarajan V, Isom LL. Sodium channel beta1 subunit-mediated modulation of Nav1.2 currents and cell surface density is dependent on interactions with contactin and ankyrin. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:16044–16049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M400856200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McTague A, Appleton R, Avula S, Cross JH, King MD, Jacques TS, Bhate S, Cronin A, Curran A, Desurkar A, Farrell MA, Hughes E, Jefferson R, Lascelles K, Livingston J, Meyer E, McLellan A, Poduri A, Scheffer IE, Spinty S, et al. Migrating partial seizures of infancy: expansion of the electroclinical, radiological and pathological disease spectrum. Brain. 2013;136:1578–1591. doi: 10.1093/brain/awt073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mena EE, Hoeser CA, Moore BW. An improved method of preparing rat brain synaptic membranes: elimination of a contaminating membrane containing 2′,3′-cyclic nucleotide 3′-phosphohydrolase activity. Brain Res. 1980;188:207–231. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90569-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milligan CJ, Li M, Gazina EV, Heron SE, Nair U, Trager C, Reid CA, Venkat A, Younkin DP, Dlugos DJ, Petrovski S, Goldstein DB, Dibbens LM, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Petrou S. KCNT1 gain of function in 2 epilepsy phenotypes is reversed by quinidine. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:581–590. doi: 10.1002/ana.24128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milstein AD, Zhou W, Karimzadegan S, Bredt DS, Nicoll RA. TARP subtypes differentially and dose-dependently control synaptic AMPA receptor gating. Neuron. 2007;55:905–918. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moosmang S, Haider N, Klugbauer N, Adelsberger H, Langwieser N, Müller J, Stiess M, Marais E, Schulla V, Lacinova L, Goebbels S, Nave KA, Storm DR, Hofmann F, Kleppisch T. Role of hippocampal Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels in NMDA receptor-independent synaptic plasticity and spatial memory. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9883–9892. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1531-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller CS, Haupt A, Bildl W, Schindler J, Knaus HG, Meissner M, Rammner B, Striessnig J, Flockerzi V, Fakler B, Schulte U. Quantitative proteomics of the Cav2 channel nano-environments in the mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14950–14957. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1005940107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy JG, Sanderson JL, Gorski JA, Scott JD, Catterall WA, Sather WA, Dell'Acqua ML. AKAP-anchored PKA maintains neuronal L-type calcium channel activity and NFAT transcriptional signaling. Cell Rep. 2014;7:1577–1588. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal MS, Ozaita A, Amarillo Y, Vega-Saenz de Miera E, Ma Y, Mo W, Goldberg EM, Misumi Y, Ikehara Y, Neubert TA, Rudy B. The CD26-related dipeptidyl aminopeptidase-like protein DPPX is a critical component of neuronal A-type K+ channels. Neuron. 2003;37:449–461. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)01185-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nägerl UV, Mody I, Jeub M, Lie AA, Elger CE, Beck H. Surviving granule cells of the sclerotic human hippocampus have reduced Ca(2+) influx because of a loss of calbindin-D(28k) in temporal lobe epilepsy. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1831–1836. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-05-01831.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanavati D, Gucek M, Milne JL, Subramaniam S, Markey SP. Stoichiometry and absolute quantification of proteins with mass spectrometry using fluorescent and isotope-labeled concatenated peptide standards. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2008;7:442–447. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M700345-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Malley HA, Isom LL. Sodium channel β subunits: emerging targets in channelopathies. Annu Rev Physiol. 2014 doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-021014-071846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong SE, Mann M. A practical recipe for stable isotope labeling by amino acids in cell culture (SILAC) Nat Protoc. 2006;1:2650–2660. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz S, Tsemakhovich V, Christel CJ, Lee A, Dascal N. CaBP1 regulates voltage-dependent inactivation and activation of Cav1.2 (L-type) calcium channels. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:13945–13953. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.198424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oz S, Benmocha A, Sasson Y, Sachyani D, Almagor L, Lee A, Hirsch JA, Dascal N. Competitive and non-competitive regulation of calcium-dependent inactivation in CaV1.2 L-type Ca2+ channels by calmodulin and Ca2+-binding protein 1. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:12680–12691. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.460949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BZ, DeMaria CD, Adelman JP, Yue DT. Calmodulin is the Ca2+ sensor for Ca2+ -dependent inactivation of L-type calcium channels. Neuron. 1999;22:549–558. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80709-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Platzer J, Engel J, Schrott-Fischer A, Stephan K, Bova S, Chen H, Zheng H, Striessnig J. Congenital deafness and sinoatrial node dysfunction in mice lacking class D L-type Ca2+ channels. Cell. 2000;102:89–97. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)00013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Puopolo M, Raviola E, Bean BP. Roles of subthreshold calcium current and sodium current in spontaneous firing of mouse midbrain dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:645–656. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4341-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin N, Olcese R, Bransby M, Lin T, Birnbaumer L. Ca2+-induced inhibition of the cardiac Ca2+ channel depends on calmodulin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2435–2438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raman IM, Bean BP. Resurgent sodium current and action potential formation in dissociated cerebellar Purkinje neurons. J Neurosci. 1997;17:4517–4526. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-12-04517.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ratcliffe CF, Qu Y, McCormick KA, Tibbs VC, Dixon JE, Scheuer T, Catterall WA. A sodium channel signaling complex: modulation by associated receptor protein tyrosine phosphatase beta. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:437–444. doi: 10.1038/74805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Redmond L, Kashani AH, Ghosh A. Calcium regulation of dendritic growth via CaM kinase IV and CREB-mediated transcription. Neuron. 2002;34:999–1010. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(02)00737-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlick B, Flucher BE, Obermair GJ. Voltage-activated calcium channel expression profiles in mouse brain and cultured hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 2010;167:786–798. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2010.02.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrauwen I, Helfmann S, Inagaki A, Predoehl F, Tabatabaiefar MA, Picher MM, Sommen M, Seco CZ, Oostrik J, Kremer H, Dheedene A, Claes C, Fransen E, Chaleshtori MH, Coucke P, Lee A, Moser T, Van Camp G. A mutation in CABP2, expressed in cochlear hair cells, causes autosomal-recessive hearing impairment. Am J Hum Genet. 2012;91:636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte U, Thumfart JO, Klöcker N, Sailer CA, Bildl W, Biniossek M, Dehn D, Deller T, Eble S, Abbass K, Wangler T, Knaus HG, Fakler B. The epilepsy-linked Lgi1 protein assembles into presynaptic Kv1 channels and inhibits inactivation by Kvbeta1. Neuron. 2006;49:697–706. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulte U, Müller CS, Fakler B. Ion channels and their molecular environments: glimpses and insights from functional proteomics. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:132–144. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk J, Harmel N, Zolles G, Bildl W, Kulik A, Heimrich B, Chisaka O, Jonas P, Schulte U, Fakler B, Klöcker N. Functional proteomics identify cornichon proteins as auxiliary subunits of AMPA receptors. Science. 2009;323:1313–1319. doi: 10.1126/science.1167852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwenk J, Harmel N, Brechet A, Zolles G, Berkefeld H, Müller CS, Bildl W, Baehrens D, Hüber B, Kulik A, Klöcker N, Schulte U, Fakler B. High-resolution proteomics unravel architecture and molecular diversity of native AMPA receptor complexes. Neuron. 2012;74:621–633. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seeburg PH. The Trends Neurosci/TiPS Lecture: the molecular biology of mammalian glutamate receptor channels. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:359–365. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90093-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenbecher CI, Langnaese K, Sanmartí-Vila L, Boeckers TM, Smalla KH, Sabel BA, Garner CC, Gundelfinger ED, Kreutz MR. Caldendrin, a novel neuronal calcium-binding protein confined to the somato-dendritic compartment. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21324–21331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaltiel L, Paparizos C, Fenske S, Hassan S, Gruner C, Rötzer K, Biel M, Wahl-Schott CA. Complex regulation of voltage-dependent activation and inactivation properties of retinal voltage-gated Cav1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels by Ca2+-binding protein 4 (CaBP4) J Biol Chem. 2012;287:36312–36321. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.392811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanks NF, Savas JN, Maruo T, Cais O, Hirao A, Oe S, Ghosh A, Noda Y, Greger IH, Yates JR, 3rd, Nakagawa T. Differences in AMPA and kainate receptor interactomes facilitate identification of AMPA receptor auxiliary subunit GSG1L. Cell Rep. 2012;1:590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Yu D, Hiel H, Liao P, Yue DT, Fuchs PA, Soong TW. Alternative splicing of the Cav1.3 channel IQ domain, a molecular switch for Ca2+-dependent inactivation within auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10690–10699. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2093-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqui TJ, Tari PK, Connor SA, Zhang P, Dobie FA, She K, Kawabe H, Wang YT, Brose N, Craig AM. An LRRTM4-HSPG complex mediates excitatory synapse development on dentate gyrus granule cells. Neuron. 2013;79:680–695. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simms BA, Zamponi GW. Neuronal voltage-gated calcium channels: structure, function, and dysfunction. Neuron. 2014;82:24–45. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2014.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Hamedinger D, Hoda JC, Gebhart M, Koschak A, Romanin C, Striessnig J. C-terminal modulator controls Ca2+-dependent gating of Ca(v)1.4 L-type Ca2+ channels. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:1108–1116. doi: 10.1038/nn1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto D, Coombs ID, Kelly L, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Stargazin attenuates intracellular polyamine block of calcium-permeable AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1260–1267. doi: 10.1038/nn1966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto D, Coombs ID, Renzi M, Zonouzi M, Farrant M, Cull-Candy SG. Selective regulation of long-form calcium-permeable AMPA receptors by an atypical TARP, γ-5. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:277–285. doi: 10.1038/nn.2266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Studniarczyk D, Coombs I, Cull-Candy SG, Farrant M. TARP γ-7 selectively enhances synaptic expression of calcium-permeable AMPARs. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16:1266–1274. doi: 10.1038/nn.3473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takamori S, Holt M, Stenius K, Lemke EA, Grønborg M, Riedel D, Urlaub H, Schenck S, Brügger B, Ringler P, Müller SA, Rammner B, Gräter F, Hub JS, De Groot BL, Mieskes G, Moriyama Y, Klingauf J, Grubmüller H, Heuser J, et al. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell. 2006;127:831–846. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tippens AL, Lee A. Caldendrin: a neuron-specific modulator of Cav1.2 (L-type) Ca2+ channels. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:8464–8473. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611384200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S, Chen L, Kawasaki Y, Petralia RS, Wenthold RJ, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Functional studies and distribution define a family of transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory proteins. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:805–816. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200212116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomita S, Adesnik H, Sekiguchi M, Zhang W, Wada K, Howe JR, Nicoll RA, Bredt DS. Stargazin modulates AMPA receptor gating and trafficking by distinct domains. Nature. 2005;435:1052–1058. doi: 10.1038/nature03624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vacher H, Trimmer JS. Diverse roles for auxiliary subunits in phosphorylation-dependent regulation of mammalian brain voltage-gated potassium channels. Pflugers Arch. 2011;462:631–643. doi: 10.1007/s00424-011-1004-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Engelhardt J, Mack V, Sprengel R, Kavenstock N, Li KW, Stern-Bach Y, Smit AB, Seeburg PH, Monyer H. CKAMP44: a brain-specific protein attenuating short-term synaptic plasticity in the dentate gyrus. Science. 2010;327:1518–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1184178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wahl-Schott C, Baumann L, Cuny H, Eckert C, Griessmeier K, Biel M. Switching off calcium-dependent inactivation in L-type calcium channels by an autoinhibitory domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:15657–15662. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604621103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong HK, Sakurai T, Oyama F, Kaneko K, Wada K, Miyazaki H, Kurosawa M, De Strooper B, Saftig P, Nukina N. β Subunits of voltage-gated sodium channels are novel substrates of β-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme (BACE1) and γ-secretase. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:23009–23017. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M414648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang B, Desai R, Kaczmarek LK. Slack and Slick K(Na) channels regulate the accuracy of timing of auditory neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:2617–2627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5308-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang PS, Alseikhan BA, Hiel H, Grant L, Mori MX, Yang W, Fuchs PA, Yue DT. Switching of Ca2+-dependent inactivation of Cav1.3 channels by calcium binding proteins of auditory hair cells. J Neurosci. 2006;26:10677–10689. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3236-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang PS, Johny MB, Yue DT. Allostery in Ca(2)(+) channel modulation by calcium-binding proteins. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10:231–238. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan A, Santi CM, Wei A, Wang ZW, Pollak K, Nonet M, Kaczmarek L, Crowder CM, Salkoff L. The sodium-activated potassium channel is encoded by a member of the Slo gene family. Neuron. 2003;37:765–773. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(03)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitz C, Kloeckener-Gruissem B, Forster U, Kohl S, Magyar I, Wissinger B, Mátyás G, Borruat FX, Schorderet DF, Zrenner E, Munier FL, Berger W. Mutations in CABP4, the gene encoding the Ca2+-binding protein 4, cause autosomal recessive night blindness. Am J Hum Genet. 2006;79:657–667. doi: 10.1086/508067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Shapiro MS. Activity-dependent transcriptional regulation of M-Type (Kv7) K(+) channels by AKAP79/150-mediated NFAT actions. Neuron. 2012;76:1133–1146. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Bal M, Bierbower S, Zaika O, Shapiro MS. AKAP79/150 signal complexes in G-protein modulation of neuronal ion channels. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7199–7211. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4446-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Brown MR, Hyland C, Chen Y, Kronengold J, Fleming MR, Kohn AB, Moroz LL, Kaczmarek LK. Regulation of neuronal excitability by interaction of fragile X mental retardation protein with slack potassium channels. J Neurosci. 2012;32:15318–15327. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2162-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Kim SA, Kirk EA, Tippens AL, Sun H, Haeseleer F, Lee A. Ca2+-binding protein-1 facilitates and forms a postsynaptic complex with Cav1.2 (L-type) Ca2+ channels. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4698–4708. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5523-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H, Yu K, McCoy KL, Lee A. Molecular mechanism for divergent regulation of Cav1.2 Ca2+ channels by calmodulin and Ca2+-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29612–29619. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]