Abstract

Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) plays an important role in the regulation of the innate and adaptive immune response. Both agonists and antagonists of TLR4 are of considerable interest as drug leads for various disease indications. We herein report the rational design of two myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD2)-derived macrocyclic peptides as TLR4 modulators, using the Rosetta Macromolecular Modeling software. The designed cyclic peptides, but not their linear counterparts, displayed synergistic activation of TLR signaling when co-administered with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Although the understanding of the mechanism of action of these peptides remains elusive; these results underscore the utility of peptide cyclization for the discovery of biologically active agents, and also lead to valuable tools for the investigation of TLR4 signaling.

Keywords: Macrocyclic peptide, Toll-like receptor 4, Myeloid differentiation factor 2, Computer design, Drug synergy

1. Introduction

Innate immunity is of crucial importance to many biological processes, thanks to its ability to readily respond to and fend off exogenous threats such as bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens.1,2 This rapid response allows an organism to combat threats upon pathogen invasion by responding to a few pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS) shared by a vast majority of pathogen or danger signals.3,4 Toll-like receptors (TLRs) are an important family of innate immune receptors. In human cells at least 10 TLRs respond to a variety of PAMPs, including lipopeptides (TLR2 associated with TLR1 or TLR6), bacterial flagellin (TLR5), viral double-stranded RNA (dsRNA, TLR3), viral or bacterial single-stranded RNA (ssRNA, TLR7 and TLR8), cytidine–phosphate-guanosine (CpG)-rich unmethylated DNA (TLR9), and lipopolysaccharide (LPS, TLR4).5-8 Specifically, the latter TLR4 recognizes LPS derived from the cell wall of Gram-negative bacteria, as well as endogenous signals such as heat shock protein 60 (HSP60), HSP70, and fibrinogen.9 Activation of this receptor depends on the formation of a homodimeric protein complex of TLR4 and its accessory protein, myeloid differentiation factor 2 (MD2).6 Assembly of the TLR4-MD2-LPS complex then initiates a myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88)-dependent signaling cascade, relocating nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) from the cytoplasm to the nucleus.10 Transcription by the NF-κB promoter directs the production of a number of proinflammatory cytokines including nitric oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β), and interferon gamma (IFN-γ).9

Previous research has indicated that TLR4 modulators were helpful to reduce the pain response2 and were also advantageous in treating inflammatory diseases.11 In particular, TLR4 activation can be beneficial to promote antitumor immunity.12 The regulation of the TLR4 signaling pathway has been a target for the development of vaccine adjuvants.13 Since TLR4 signaling depends on the formation of the TLR4/MD2 homodimer,14,15 targeting the MD2-TLR4 interface is of remarkable interest in therapeutic development. Specific point mutations in MD2, such as Cys95Tyr, prevent its association with TLR4, abolishing signaling downstream to TLR4.16 The recently reported crystal structure of the murine TLR4-MD2 complex revealed more details of the molecular recognition sites on the TLR4-MD2 interface, which could serve as potential targets for the design of TLR4 signaling modulating peptides that work as either agonists or antagonists of the TLR4-mediated proinflammatory response.17 The complex structure displays charged corresponding patches on the TLR4 and MD2 interfaces (termed A, B and A′B′, respectively) that provide considerable binding affinity. In particular, the B′ patch on MD2 consists of three consequtive aspartate residues 99-101 that are located within a loop stabilized by a disulfide bridge (C95-C105). 17 This sequence region was shown to play a critical role in the MD2-TLR4 interaction18 (critical “hot-spot” residues are underlined in Table 1). Indeed, our previous study showed that a rationally designed disulfide-bridged peptide spanning residues 95-111 (MD2-I, Table 1) can work as an antagonist by blocking LPS induced TLR4-MD2 association.19 In the present study we report that the same region can be used to design agonist peptides when co-administered with LPS: These MD-2 derived disulfide bridged cyclic agonist peptides work synergistically with LPS in induction of TLR4 signaling in a whole-cell assay. Thus, while the mechanism that defines agonist and antagonist activity of these peptides is yet to be identified, the fact that both agonist and antagonist peptides can be designed based on the same MD2-derived peptidic stretch, suggests a novel strategy for future development of immune modulators.

Table 1.

Sequence alignment of murine MD2, the designed peptides described in the present study (YH1-4), and a previously reported peptide inhibitor (MD2-I) that disrupts the TLR4/MD2 interaction.19 The previously experimentally identified critical “hot-spot” residues are underlined.18 Disulfide-bond forming cysteine residues are highlighted in bold. These cysteine residues are mutated to alanines (italicized) in YH2 and YH4 for comparison.

| Peptide | Amino Acid Sequence |

|---|---|

| Murine17 | R90KEVLCHGHDDDYSFCRALKGETVNTSIPFS120 |

| MD2-I | CRGSDDDYSFCRALKGE |

| YH1 | DCDYSFCRAL |

| YH2 | DADYSFARAL |

| YH3 | CAADDDYSFCRALAAC |

| YH4 | AAADDDYSFCRALAAA |

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Computational Design

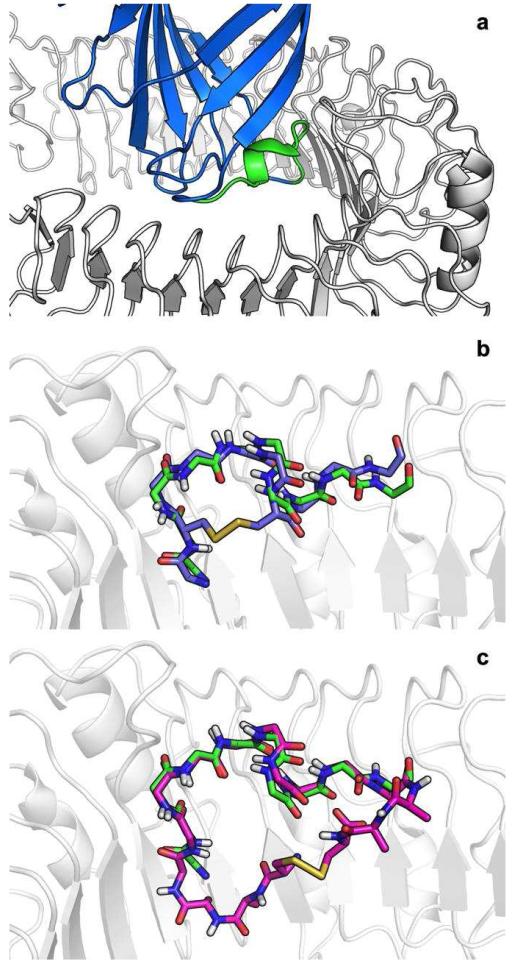

We previously reported a protocol for the identification of dominant linear peptides (or hot-segments) at the interfaces of protein-protein complexes.20 Here we have applied this protocol to the complex of human TLR4 and MD2 (PDB ID: 3FXI). A 10-mer peptide derived from MD2 99-DDDYSFCRAL-108 was identified as contributing 52% of the binding energy of the interaction (Fig. 1a). Manual inspection of this peptide conformation in the context of TLR4 suggested two possible cyclization strategies.

Figure 1. Disulfide cyclic designs of MD2 derived peptides.

a. MD2 (blue) in complex with TLR4 (white). The identified dominant peptide 99-108 (green) is predicted to contribute 52% of the interaction energy. b. YH1: (purple) A D100C cyclic peptide in which the new cysteine forms a disulfide with Cys105, creating a small macrocycle. c. YH3: (magenta) an extended peptide with flanking Ala-Ala-Cys sequences, forming a larger disulfide–mediated macrocycle.

YH1

The first approach utilizes Cys105 which in the complete MD2 structure takes part in a disulfide bridge with Cys95. A D100C mutation will place the new Cys100 in a position to create a disulfide bridge with Cys105. (Fig. 1b) Both Asp100 and Cys105 are at the “back” side of the peptide and are not involved in any interactions with TLR4 (Note that nevertheless, D100 has previously been defined as a binding hotspot residue, due to the detrimental effect of the D100G point mutant on TLR4 binding18. This is most probably an indirect effect due to increased loop flexibility introduced by the new Glycine residue, since the side chain of D100 itself does not directly contact TLR4). Short flexible backbone relaxation simulations of the peptide suggest that the disulfide bond can be accommodated with almost no backbone adjustments (1.1Å root mean square deviation over Cα atoms). In the corresponding YH2 peptide, the two cysteines involved in the disulfide bridge were mutated to alanine, allowing us to assess the importance of cyclization for peptide binding.

YH3

Addition of short linkers on both sides of the peptide CAA-DDDYSFCRAL-AAC will allow the peptide to adopt its binding conformation with minimal backbone adjustment (0.53Å Cα RMSD) while creating a larger disulfide mediated macrocycle (Fig. 1c). The di-alanine linkers are predicted to form only minor interactions with TLR4. Again, a corresponding control peptide, YH4, was devised that contains alanine substitutions at the disulfide-bridge forming cysteine positions.

2.2. Peptide preparation

Mid-sized peptide macrocycles have been known to be challenging goals for solid phase peptide syntheses (SPPS). We employed the Fmoc-protection strategy outlined by Bacsa and Kappe with minor modifications to adapt a protocol for microwave-assisted solid peptide synthesis.21 Briefly, the cyclic and control linear peptides were synthesized on a commercial Rink Amide AM resin (200-400 mesh) (Nova Biochem) with a substitution level of 0.71 mmol/g. Each coupling using five equivalents of HBTU coupling reagent and five equivalents of amino acid was performed in duplicate with a coupling time of two minutes. After cleavage and workup, peptides with an imidized C-terminus and a free amino N-terminus were characterized using Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectroscopy. All peptides were purified by a Waters 600E HPLC equipped with a SepaxGP-C8 reverse phase, 21.2 × 250 mm column over a 50:50 to 0:100 (water, 0.1% TFA:acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA) gradient for thirty to forty minutes. Fractions were characterized with mass spectrometry and lyophilized to dryness (Supplementary Figures 1-4). The overall yield of the pure YH1, YH2, YH3 and YH4 are 13.5%, 9.8%, 16.3% and 41.4%, respectively.

2.3. Macrocyclic, but not linear YH peptides are effective TLR4/MD-2 modulators

The computational modeling predicts that the macrocyclic peptides YH1 and YH3 would be able to adopt the TLR4-binding conformations similar to their counterpart sections in the full-length MD2. As such they might compete with MD2 for TLR4 binding, and consequently act either as agonists (exert the same effect of MD2 binding to TLR4), or antagonists (prevent MD2-mediated activation of TLR4). As mentioned above, linear peptide mutants (YH2 and YH4) were used to evaluate the importance of cyclization (Table 1).

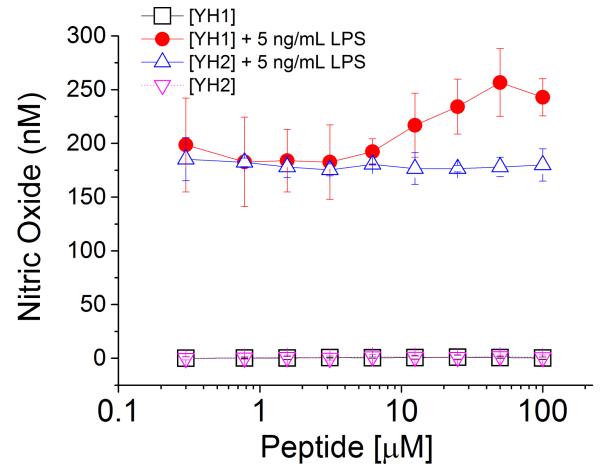

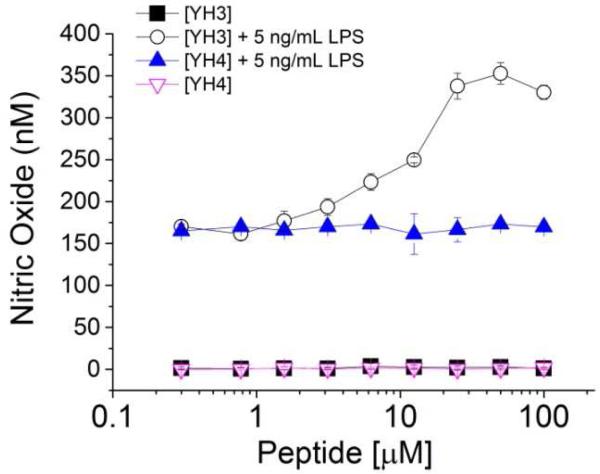

Nitric oxide (NO) is a low molecular weight agent that plays an important role in numerous cell signaling cascades.22 For instance, macrophage cells turn up NO production upon detection of pathogen invasions.23 In the TLR-mediated inflammatory response, NO is a downstream effector of NF-κb activation, a common effect shared by all TLRs.24 By monitoring the NO signal induced by LPS, one can measure the TLR4 signaling activation. Herein, we tested different concentrations of YH1, YH2, YH3 and YH4 on the Raw 264.7 macrophage cell line. None of them demonstrated either agonism or antagonsim to NO signaling, when administered alone, for concentrations up to 100 μM (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). By contrast, after incubation of 5 ng/mL LPS with Raw 264.7 cells for 24 hours, we observed a significant increase of NO production by LPS (data not shown), showing the activation of the TLR4 signaling pathway. Interestingly, when the cells were treated with the YH1 macrocyclic peptides in the presence of LPS, a significant synergetic effect was observed. This effect was not observed with co-treatment of the linear control peptide, YH2, with LPS (Fig. 2, and Supplementary Figure 5), suggesting that the disulfide bridge-mediated closure of the peptides is critical for the observed activity (Supplementary Figure 6). A similar behavior was observed for the cyclic peptide with YH3. Again, YH3 showed a significantly stronger synergistic effect with LPS (more than 2 fold change) in the activation of NO signaling in comparison to its linear counterpart, peptide YH4 (Fig. 3, and Supplementary Figure 5). Last, we note that the longer peptide YH3 lead to a stronger synergistic effect with LPS than YH1, suggesting that not only the disulfide bond, but also the cycle size is an important determinant of activity.

Figure 2. Nitric oxide production induced by LPS in the presence and absence of macrocyclic peptide, YH1, or its linear control, YH2.

NO activation is induced in the Raw 264.7 cells by LPS in the presence of various concentrations of macrocyclic peptide (YH1), or the linear corresponding peptide (YH2).

Figure 3. Nitric oxide production induced by LPS in the presence and absence of macrocyclic peptide, YH3, or its linear control, YH4.

NO activation is induced in the Raw 264.7 cells by LPS in the presence of various concentrations of macrocyclic peptide, YH3, or the linear corresponding peptide (YH4).

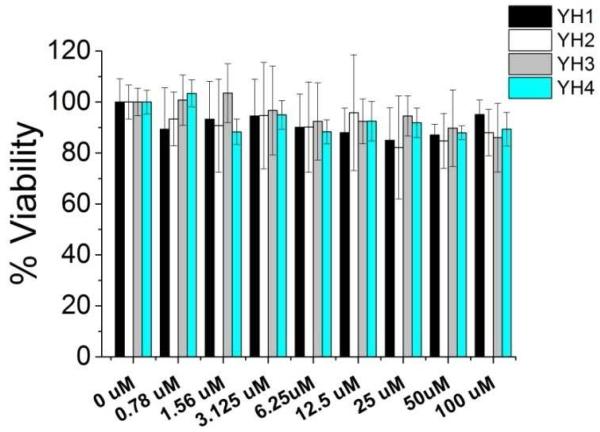

2.4. Macrocyclic induced inflammatory response with minimal cytotoxicity

It is well known that cells under stress (e.g. cytotoxicity) may also produce elevated levels of NO via a TLR-independent pathway. As the YH peptides do not induce NO production in the absence of LPS, the possibility of YH’s ability to synergetically induce NO production with LPS by non-specifically stressed cells is low. Nonetheless, to demonstrate that the YH peptides did not induce NO enhancement by cytotoxicity, we employed a previously established cytotoxicity MTT assay to test the cell viability in the absence and presence of the macrocyclic peptides along with their linear controls (Fig. 4). Our results show that only negligible cytotoxicity was induced by the YH peptides in RAW 264.7 cells, confirming that they likely induce NO production enhancement through a TLR-specific mechanism (Fig. 4). Further biochemical and biophysical characterizations of their molecular interactions are currently in process.

Figure 4. The YH peptides showed negligible cytotoxicity to the Raw 264.7 cells.

The MTT toxicity assay results showed little cytotoxicity caused by the YH peptides, ruling out the possibility that the increase of NO production in the presence of the YH peptides are due to non-specific cell stress. This is consistent with the hypothesis that the YH peptides directly mediated cell functions by their interaction with TLR4.

3. Conclusion

In the current study, we used the Rosetta program to derive and model macrocyclic peptides to target the MD2-binding region of TLR4. Using microwave-assisted solid peptide syntheses, we have synthesized and evaluated the activity of the two designed peptides along with their linear controls. Results indicate that the macrocyclic peptides (YH1 and YH3) were effective in synergistic enhancement of LPS-induced inflammatory response, whereas their linear controls (YH2 and YH4) showed little effects, suggesting that the disulfide bond bridge is important for the agonistic activities. This NO production is not due to general cytotoxic effects of these peptides on the cells, but rather dependent on TLR4 activation, as our cytotoxicity assays reveal. This demonstrates that the hereby presented macrocyclic peptides with rigidified structures act as successful agonists of induction of the TLR4 signaling pathways. Thus, even though the exact mechanism of activation is not yet elucidated, these peptides provide a good starting point for the targeted fine-tuned manipulation of TLR4-mediated inflammatory response.

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Computational Modeling

The MD2 dominant interface peptide was identified using the PeptiDerive protocol20 on chains A (TLR4) and C (MD2) of PDB: 3FXI using the following command line:

PeptideDeriver.linuxgccrelease –database rosetta_database/ - in:file:s 3fxi.AC.pdb

PeptiDerive has been described previously20. In short, for an input pdb file consisting of two interacting protein chains, the protocol first estimates the binding energy of this complex (Δ Gbind), and then calculates for each overlapping 10-mer peptide in a protein partner its relative contribution to this binding energy. The output provides the strongest binding peptide. For the sake of accuracy, we note that the default scoring function of Rosetta has been replaced since our simulations. The current version would detect positions 97-106 as the dominant peptide (GSDDDYSFCR, shifted by two positions). To obtain the same results as reported here, the parameter –restore_pre_talaris_2013_behavior has to be added to the command line. The Rosetta PeptiDerive protocol will be available shortly in an upcoming release at http://www.rosettacommons.org/software/licences-and-download), and can also be requested from the authors.

Cysteine residues were introduced using RosettaDesign25 and the cyclic peptides were relaxed26 while enforcing the formation of the disulfide bond using the following command line:

relax.linuxgccrelease -database rosetta_database/ - in:file:native cyclic.pdb –in:file:s cyclic.pdb -fix_disulf ss - relax:fast -constrain_relax_to_start_coords -chi_move false.

4.2. Nitric Oxide (NO) production assay

RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were grown in 96-well plates (50,000 cells per well) including 200 μL RPMI medium supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin (100 U/ml), streptomycin (100 mg/ml) and L-glutamine (2 mM) for 24 hours at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 humidified incubator. The medium was then changed to pure RPMI and indicated concentrations of peptide (or peptide with 5 ng/mL LPS) were added to the total volume of 200 μL. Following another 24 hours incubation, 100 μL of supernatant was collected and added to flat black 96-well microfluor plates (Thermo scientific, MA, USA). The plates were incubated for 15 min with 10 μL of 2,3-diaminonaphthalene (0.05 mg/ml in 0.62 M HCl) added to each well, and then quenched by addition of 3 M NaOH (5 μL).5 Fluorescence was determined on a Beckman Coulter DTX880 plate reader (Beckman Coulter, CA, USA) with excitation wavelength set at 365 nm and emission wavelength set at 450 nm.

4.3. MTT cell viability assay

RAW 264.7 macrophage cells were cultured as described above for the NO assay. After change of medium to pure RPMI, each peptide was added with indicated concentration from 0 μM to 100 μM. After 24h incubation, 20 μL (5 mg/mL in PBS) MTT solution was added to each well and incubated (37 °C, 5% CO2) extra 4 hours to allow the MTT to be metabolized. The media was removed and the plate was dried on paper towels to remove any residue, followed by addition of 150 μL DMSO in each well and continued shaking for an additional 40 minutes. When all the MTT metabolic products were dissolved, optical density was determined using an UV-Vis spectrophotometer set at wavelength of 560 nm. Optical density should be directly correlated with cell quantity. Cytotoxicity (%) was determined using the following formula: Cytotoxicity (%) = (1 − [Compounds (OD560) − Background (OD560)]/[Control (OD560)−Background (OD560)])×100.

4.4. secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) assay

HEK-Blue hTLR4 cells were obtained by co-transfection of the human TLR4, MD-2 and CD14 co-receptor genes, and an inducible secreted embryonic alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) reporter gene into HEK293 cells. Cells were cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 10× penicillin/streptomycin and 10×l-glutamine. Cells were implanted in 96 well plates (4×104 cells /well) for 24 h at 37 °C prior to drug treatment. In the next 24h treatment, media was removed from the 96-well plate, replaced with 200 μL supplemented Opti-MEM medium (0.5% FBS, 50 U/ml penicillin, 50 μg/ml streptomycin, 1 × nonessential amino acid) containing 0-100 μM peptides with or without 5 ng/mL LPS, or containing 5 ng/mL LPS with or without 100 μM YH1 (or YH3), or containing 5 ng/mL LPS with dithiothreitol (DTT) treated peptides (YH1 or YH3 treated with 0.5 mM DTT in 37 °C for 1h). A sample buffer (20 μL) from each well of the cell culture supernatants was collected and transferred to a transparent 96 well plate (Thermo Scientific MA, USA). Each well was treated with 200 μL of QUANTI-Blue (Invivogen) buffer, and incubated at 37 °C for 1h. A purple color can be observed and optical density was measured using a plate reader at OD 620.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (R01GM101279 and R01GM103843 to H. Y.) for the financial support.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Beutler B. Nature. 2004;430:257–263. doi: 10.1038/nature02761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bevan DE, Martinko AJ, Loram LC, Stahl JA, Taylor FR, Joshee S, Watkins LR, Yin H. ACS Med. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:194–198. doi: 10.1021/ml100041f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miyauchi K, Urano E, Takeda S, Murakami T, Okada Y, Cheng K, Yin H, Kubo M, Komano J. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;424:519–523. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.06.148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Neill LAJ. Nat. Immunol. 2008;9:459–461. doi: 10.1038/ni0508-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng K, Wang XH, Zhang ST, Yin H. Angew. Chem.-Int. Edit. 2012;51:12246–12249. doi: 10.1002/anie.201204910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Botos I, Segal DM, Davies DR. Structure. 2011;19:447–459. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2011.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imler JL, Hoffmann JA. Nat. Immunol. 2003;4:105–106. doi: 10.1038/ni0203-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guo LH, Schluesener HJ. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2007;64:1128–1136. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-6494-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeda K, Akira S. Semin. Immunol. 2004;16:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.O’Neill LAJ, Bryant CE, Doyle SL. Pharmacol. Rev. 2009;61:177–197. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oblak A, Jerala R. Clin. Dev. Immunol. 2011:12. doi: 10.1155/2011/609579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mata-Haro V, Cekic C, Martin M, Chilton PM, Casella CR, Mitchell TC. Science. 2007;316:1628–1632. doi: 10.1126/science.1138963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shimazu R, Akashi S, Ogata H, Nagai Y, Fukudome K, Miyake K, Kimoto M. J. Exp. Med. 1999;189:1777–1782. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.11.1777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang H, Young DW, Gusovsky F, Chow JC. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:20861–20866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002896200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Visintin A, Latz E, Monks BG, Espevik T, Golenbock DT. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:48313–48320. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M306802200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim HM, Park BS, Kim JI, Kim SE, Lee J, Oh SC, Enkhbayar P, Matsushima N, Lee H, Yoo OJ, Lee JO. Cell. 2007;130:906–917. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Re F, Strominger JL. J. Immunol. 2003;171:5272–5276. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.10.5272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Slivka PF, Shridhar M, Lee GI, Sammond DW, Hutchinson MR, Martinko AJ, Buchanan MM, Sholar PW, Kearney JJ, Harrison JA, Watkins LR, Yin H. ChemBioChem. 2009;10:645–649. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200800769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.London N, Raveh B, Movshovitz-Attias D, Schueler-Furman O. Proteins. 2010;78:3140–3149. doi: 10.1002/prot.22785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bacsa B, Kappe CO. Nat. Protoc. 2007;2:2222–2227. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowenstein CJ, Alley EW, Raval P, Snowman AM, Snyder SH, Russell SW, Murphy WJ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1993;90:9730–9734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.20.9730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang X, Smith C, Yin H. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2010;42:4859–4866. doi: 10.1039/c3cs60039d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hennessy EJ, Parker AE, O’Neill LAJ. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010;9:293–307. doi: 10.1038/nrd3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuhlman B, Baker D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10383–10388. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khatib F, Cooper S, Tyka MD, Xu K, Makedon I, Popovic Z, Baker D. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:18949–18953. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1115898108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.