Abstract

Human cytosolic sulfotransferases (SULTs) regulate the activities of thousands of small molecules—metabolites, drugs, and other xenobiotics—via the transfer of the sulfuryl moiety (-SO3) from 3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS) to the hydroxyls and primary amines of acceptors. SULT1A1 is the most abundant SULT in liver and has the broadest substrate spectrum of any SULT. Here we present the discovery of a new form of SULT1A1 allosteric regulation that modulates the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme over a 130-fold dynamic range. The molecular basis of the regulation is explored in detail and is shown to be rooted in an energetic coupling between the active-site caps of adjacent subunits in the SULT1A1 dimer. The first nucleotide to bind causes closure of the cap to which it is bound and at the same time stabilizes the cap in the adjacent subunit in the open position. Binding of the second nucleotide causes both caps to open. Cap closure sterically controls active-site access of the nucleotide and acceptor; consequently, the structural changes in the cap that occur as a function of nucleotide occupancy lead to changes in the substrate affinities and turnover of the enzyme. PAPS levels in tissues from a variety of organs suggest that the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme varies across tissues over the full 130-fold range and that efficiency is greatest in those tissues that experience the greatest xenobiotic “load”.

Transfer of the sulfuryl group (-SO3) to and from small-molecule metabolites switches these compounds between distinctly different functional states. Sulfonation of the agonists and antagonists that bind nuclear and dopamine receptors, which regulate scores of complex cellular functions, typically decreases but can also enhance their affinities for their targets by orders of magnitude. The inability to maintain the requisite balance of sulfonated and nonsulfonated forms of a particular compound(s) has been linked to human diseases, including breast1 and endometrium2 cancer, Parkinson’s disease,3 cystic fibrosis,4 and hemophilia.5

Small-molecule sulfonation is catalyzed by a small, approximately 13-member,6 family of enzymes, the cytosolic sulfotransferases (SULTs). The donor in these reactions is the nucleotide PAPS (3′-phosphoadenosine 5′-phosphosulfate), also known as activated sulfate. The remarkably high chemical potential of the phosphoric–sulfuric acid anhydride bond in PAPS potentiates the sulfuryl moiety for energetically favorable transfer to recipients.7 The acceptors are the hydroxyls and primary amines of hundreds, if not thousands, of small molecules—endogenous metabolites, drugs, and other xenobiotics.8 In addition to their roles in regulating endogenous metabolites, SULTs provide a critical defensive function; they detoxify compounds, particularly xenobiotics, by preventing them from binding adventitiously to receptors and target them for degradation and elimination.1,9,10

SULT1A1, the focus of this study, is the predominant SULT isoform in liver and is responsible for the majority of the sulfonation that occurs there.11 Consistent with its role in detoxifying xenobiotics—an enormous, complex category of compounds—the substrate spectrum of SULT1A1 is the broadest of any SULT.6 Recent studies of the molecular basis of SULT substrate specificity reveal that SULTs extensively utilize a conserved, dynamic 30-residue active-site “cap” in selecting their substrates. In the unliganded state, the cap is open.12−14 As PAPS binds, the cap closes and molecular “pores” that sterically restrict ligand access are formed at the acceptor and donor sites. PAPS is too large to pass through the nucleotide pore, and its entry and departure require that the cap open.13 Certain acceptors are small enough to pass unrestricted through the acceptor pore; others are not, and their binding, like that of PAPS, also requires cap opening.15 Here we show that opening and closing of the caps in the SULT1A1 dimer are allosterically coordinated by the binding of nucleotide. Binding of the first and second nucleotides produces different cap configurations, and the catalytic efficiencies of these forms differ over a 130-fold dynamic range. For the first time, it is clear that a nucleotide can function as an allostere in SULT systems.

Materials and Methods

The experimental materials and their sources are as follows. Adenosine monophosphate (AMP), dithiothreitol (DTT), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1-hydroxypyrene (1-HP), 4-hydroxytamoxifen (afimoxifene, TAM), imidazole, isopropyl thio-β-d-galactopyranoside (IPTG), Luria broth (LB), lysozyme, β-mercaptoethanol (β-ME), pepstatin A, Na2HPO4, and NaH2PO4 were obtained from Sigma. Ampicillin, HEPES, KCl, KOH, MgCl2, NaCl, and phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) were purchased from Fisher Scientific. Glutathione- and nickel-chelating resins were obtained from GE Healthcare. Competent Escherichia coli [BL21(DE3)] cells were purchased from Agilent Technologies. PAP, PAPS, and [35S]PAPS were synthesized in house as previously described12,16,17 and were ≥98% pure as assessed by anion-exchange high-performance liquid chromatography.

Protein Purification

The open reading frame of the human SULT1A1 DNA was codon-optimized for E. coli (MR. GENE) and inserted into a pGEX6 vector containing a His/GST/MBP triple affinity tag.14 The enzyme was expressed in E. coli BL21(DE3) and purified according to a published protocol.17 Briefly, enzyme expression was induced with IPTG (0.50 mM) in LB medium at 16 °C for 14 h. The cells were pelleted, resuspended in lysis buffer, sonicated, and centrifuged. The supernatant was loaded onto a Chelating Sepharose Fast Flow column charged with Ni2+. The enzyme was eluted with imidazole (10 mM) onto a Glutathione Sepharose column and then eluted with glutathione (10 mM). The tag was cleaved from the enzyme by precision protease, and the enzyme was separated from the tag using a glutathione resin. Finally, the protein was concentrated using a Millipore Ultrafiltration Disc (Ultracel 10 kDa cutoff), and the concentration was determined spectrophotometrically (ε280 = 54 mM–1 cm–1).14 The enzyme was flash-frozen and stored at −80 °C.

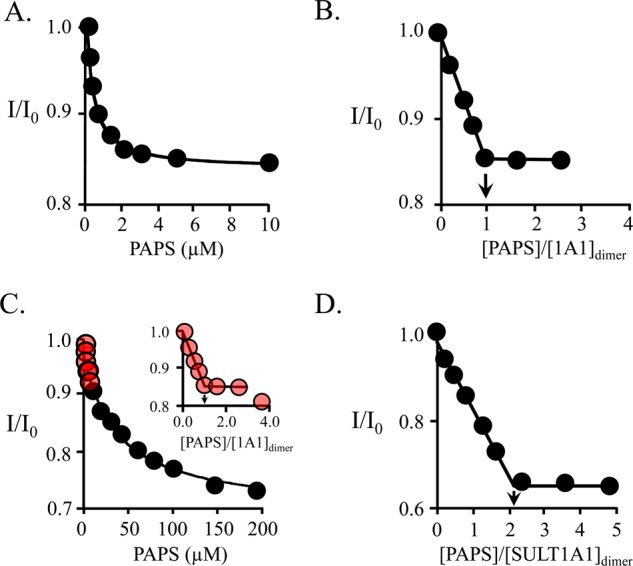

Equilibrium Binding of PAPS to SULT1A1

Binding of PAPS to SULT1A1 was monitored via ligand-dependent changes in intrinsic fluorescence (λex = 290 nm; λem = 345 nm). Typically, PAPS was titrated into solutions containing SULT1A1, MgCl2 (5.0 mM), and NaPO4 (50 mM) at pH 7.2 and 25 ± 2 °C. The PAPS concentrations used in the titration depicted in Figure 1D were high enough to cause inner-filter effects. Consequently, λex was shifted to 297 nm to lower the PAPS absorbance (ε297 = 0.43 mM–1 cm–1). Despite the lowered absorbance, inner-filter effects were detected at ≥60 μM PAPS. To correct for these effects, control titrations in which AMP (which does not bind SULT1A1) was substituted for PAPS were performed and the PAPS titration data were corrected accordingly. All titrations were performed in triplicate, and the averaged data were least-squares fit using a model that assumes a single binding site per dimer.12

Figure 1.

Equilibrium binding of PAPS to SULT1A1. (A) PAPS binding to the high-affinity subunit. Binding was monitored via ligand-induced changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of SULT1A1 (λex = 295 nm; λem = 345 nm). Reaction conditions included SULT1A1 (0.05 μM, dimer), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2 °C. Each point is the average of three independent determinations. The solid line through the data represents a least-squares fit using a model that assumes a single binding site per dimer. Kd = 0.37 ± 0.05 μM. (B) PAPS binding stoichiometry at the high-affinity site. The conditions were identical to those in described for panel A except that [SULT1A1] = 3.0 μM dimer (16Kd). The stoichiometry was 1.1 ± 0.2 PAPS molecules per dimer. (C) PAPS binding at the low-affinity site. Experimental conditions were identical to those in described for panel B. PAPS binding is biphasic. The high- and low-affinity phases are colored red (inset) and black, respectively. The line through the points represents a least-squares fit to the low-affinity phase using a model that assumes a single binding site per dimer. Kd = 30 ± 4 μM. (D) Full-site PAPS binding stoichiometry. The reaction conditions were identical to those described for panel A except that [SULT1A1] = 475 μM dimer (16Kd for the low-affinity site). The stoichiometry was 2.1 ± 0.2 PAPS molecules per dimer, or 1.1 ± 0.1 per subunit.

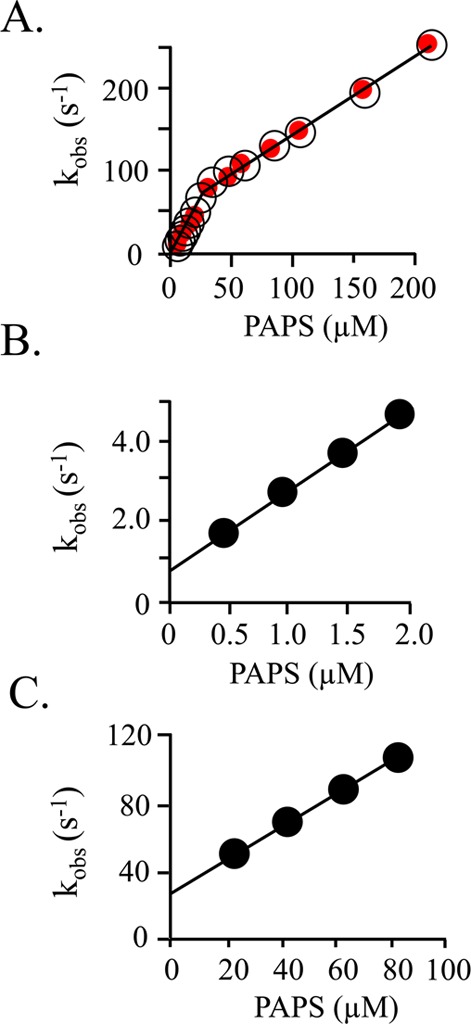

Pre-Steady-State PAPS Binding Studies

Pre-steady-state binding experiments were performed using an Applied Photophysics SX20 stopped-flow spectrofluorimeter. SULT1A1 fluorescence was excited at 290 nm and detected above 330 nm using a cutoff filter. kon and koff for binding to the high-affinity site were obtained by rapidly mixing [1:1 (v:v)] a solution containing SULT1A1 (30 nM, dimer), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), and NaPO4 (25 mM) at pH 7.2 and 25 ± 2 °C with a solution that was identical except that it contained PAPS and was without enzyme. kon and koff for the binding to the low-affinity site were determined by pre-equilibrating the dimer (2.0 μM) with PAPS (4.0 μM) and then rapidly mixing the equilibrated solution [1:1 (v:v)] with a solution that was identical except for the PAPS concentrations and the fact that it lacked enzyme. The reactions were pseudo-first-order with respect to PAPS concentration. Three independently determined progress curves (each an average of 8–10 binding reactions) were collected at four separate PAPS concentrations. The apparent rate constant (kobs) at a given PAPS concentration was obtained by fitting the average of the three curves to a single-exponential equation. kon and koff were obtained from the slopes and intercepts, respectively, predicted by linear least-squares analysis of four-point kobs versus PAPS concentration plots.18

Equilibrium Binding of TAM and 1-HP to SULT1A1

Binding of an acceptor to three different enzyme forms [E, E·PAP, and E·(PAP)2] was monitored via ligand-induced changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of the enzyme (λex = 290 nm; λem = 345 nm). Acceptors were titrated into a solution containing SULT1A1 (0.05–10 μM, dimer), PAP (0–500 μM), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), and NaPO4 (25 mM) at pH 7.2 and 25 ± 2 °C. Titrations were performed in triplicate. Data were averaged and least-squares fit using a model that assumes a single binding site per monomer.12,17

Activation of SULT1A1

The initial rate response of SULT1A1 to nucleotide binding at the high- and low-affinity sites was studied using 1-HP, a fluorescent acceptor. 1-HP and its sulfonated counterpart (1-HPS) fluoresce at a λex of 320 nm, but the intensity ratio at a λem of 380 nm is >100 in favor of 1-HPS. Reaction progress was monitored via 1-HPS fluorescence (λex = 320 nm; λem = 380 nm). Reactions were initiated by addition of PAPS, and the conditions were as follows: SULT1A1 (1.0 nM, dimer), 1-HP (160 μM, 20Kd), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2.0 °C. The PAPS concentration was the limiting substrate in all cases, and it was ≤5% consumed at the end point of the reactions. The experiments were performed in duplicate. The Km and kcat of 1-HP for the doubly occupied enzyme were determined using a saturating PAPS concentration (2.0 μM), and a range of 1-HP concentrations (8.0–200 nM, 0.2–5Km). The kinetic constants for 1-HP sulfation with the singly occupied enzyme were obtained using the same strategy except that the PAPS concentration was sufficient to saturate only the first site (0.30 μM). Initial rate constants were obtained using a weighted least-squares fit of the data in double-reciprocal format.19

Initial Rate Kinetics of TAM Sulfation

The initial rate of TAM sulfation was measured using radiolabeled [35S]PAPS. Reaction conditions included SULT1A1 (10 nM, dimer), [35S]PAPS (3.0 or 250 μM, 14 nCi/reaction), TAM (0.12–70 μM, 0.20–5.0Km), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2 °C. The reactions were initiated by the addition of PAPS to a final volume of 10 μL. The reactions were quenched after 10–50 min with 1.0 μL of 0.10 M NaOH and then the mixtures neutralized with HCl. Samples were then boiled for 1.0 min and centrifuged for 5.0 min at 12100g. The samples were spotted onto a reverse phase thin layer chromatography plate and separated using a running buffer containing methylene chloride, methanol, water, and ammonium hydroxide (90:16:3.5:0.50 volume ratio). Radiolabeled products were visualized and quantitated using a STORM imaging system.

Results and Discussion

Biphasic Binding of PAPS to SULT1A1

The fluorescence titrations depicted in Figure 1A–D present what appears to be the first example of the biphasic binding of PAPS to SULT1A1, or any SULT. The conditions of the titration pairs, A/B and C/D, were selected to yield affinities and stoichiometries, respectively, of PAPS binding to the high-affinity (A/B) and low-affinity (C/D) sites of the enzyme. The enzyme active-site concentrations used in the “affinity-constant” titrations (A and C) were set below (≤0.14) Kd, while those used in “stoichiometry” titrations (B and D) were ≥15Kd.

The affinity of PAPS for the high-affinity site of SULT1A1 [Kd = 0.37 ± 0.05 μM (Table 1)] is virtually identical to that for other SULTs;12,14,16 its stoichiometry, however, is not.12,17 A second titration, at [SULT1A1] = 16Kd, reveals that the stoichiometry of PAPS binding at the high-affinity site is 1.1 ± 0.1 per SULT1A1 dimer (Figure 1B). Clearly, only one subunit in each dimer exhibits high affinity. This finding stands in contrast to the behaviors of SULT2A1 and SULT1E1, which bind 1 equiv of PAPS with high affinity at each dimer subunit.14,16

Table 1. PAPS Binding to SULT1A1.

| binding site | kon (μM–1 s–1)a | koff (s–1)a | koff/kon (μM)a | Kd (μM)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| high-affinity | 2.0 (0.1) | 0.70 (0.05) | 0.37 (0.04) | 0.37 (0.05) |

| low-affinity | 0.96 (0.01) | 29 (1) | 30 (3) | 30 (4) |

Values in parentheses indicate one standard deviation.

As the nucleotide concentration increases beyond saturation of the first site, a second binding phase is observed (Figure 1C). Red dots indicate the region of the titration in which binding occurs nearly exclusively at the high-affinity site, and as the inset shows, that site is loaded stoichiometrically. In the black-dotted region, a low-affinity site becomes saturated. The Kd associated with this region is 31 ± 4 μM. To confirm that this phase is associated with a single nucleotide site, its PAPS binding stoichiometry was determined (Figure 1D). The low-affinity site clearly binds one nucleotide, and thus, SULT1A1, like its siblings, binds one nucleotide at each subunit.

Most members of the SULT family harbor a conserved 30-residue active-site cap that covers both the nucleotide and acceptor binding pockets.13,14,20 The nucleotide is nearly completely encapsulated when the cap is closed, and its addition and escape require that the cap open.20 The cap of the ligand-free enzyme is predominantly open (≥95%14,20), while that of nucleotide-bound SULT1A1 is closed ∼95% of the time.14,20 As the cap closes at the acceptor site, a pore forms, creating an entrance to the acceptor binding pocket. The binding of acceptors small enough to pass through the pore is not affected by cap closure; nucleotide binding has no discernible effect on the kon and koff of such compounds. As acceptors become too large to pass through the pore, nucleotide binding causes their affinities to decrease by a factor given by the cap closure isomerization equilibrium constant (Kiso), which equals 26 for SULT1A1.14 This decrease in affinity is due solely to a decrease in kon and is caused by the nucleotide-induced 26-fold decrease in the concentration of the enzyme form to which large compounds can bind.

The Hypothesis

Given the coupling between PAPS binding and cap closure, and structural data indicating that the cap must open for PAPS to enter and depart, we reasoned that the decreased affinity for the second nucleotide could be due to reciprocal interactions between the open and closed forms of adjacent caps. If PAPS binding and closure at the first subunit stabilize the adjacent cap in either the open or closed position, the affinity of PAPS for the second site will decrease relative to that for the first. If closure is stabilized, kon for PAPS binding will decrease, because closure decreases the concentration of the only form to which PAPS can bind, the cap-open form. If, on the other hand, the adjacent cap is stabilized in the open position, the kon for binding to the tight and weak sites will be identical, because the caps of both the unliganded and singly liganded enzymes are fully open (≥95%). Thus, the change in affinity will be due solely to an increase in koff that occurs because the nucleotide need not “wait” until the cap opens to depart.

The Test

To test the coupled cap model and distinguish between the adjacent cap open and closed mechanisms, the on and off rate constants for binding of PAPS to SULT1A1 were determined over a range of PAPS concentrations that probe binding to the tight and weak sites. PAPS binding was monitored via binding-induced changes in the intrinsic fluorescence of SULT1A1 (Figure S1 of the Supporting Information shows a typical PAPS binding reaction). The reactions were pseudo-first-order in PAPS concentration, and kobs values were obtained by fitting progress curves to a single-exponential model. The results are compiled in the kobs versus PAPS concentration plot presented in Figure 2A, which shows two distinct linear phases indicative of two experimentally separable binding sites.

Figure 2.

Pre-steady-state binding of PAPS to SULT1A1. (A) Composite kobs vs [PAPS] plot. Two well-isolated binding phases are observed. Binding was monitored via changes in SULT1A1 intrinsic fluorescence (λex = 290 nm; λem ≥ 330 nm). kobs values are the average of three independent determinations. Reaction conditions included SULT1A1 (0.050 μM, dimer), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2 °C. Red dots indicate the kobs values predicted using the kon and koff values obtained from the experiments associated with panels B and C. (B) kobs vs [PAPS] for the high-affinity subunit. Reaction conditions were identical to those described for panel A except that [SULT1A1] = 0.030 μM (dimer). kon = 2.0 ± 0.2 μM–1 s–1; koff = 0.70 ± 0.02 s–1. (C) kobs vs [PAPS] for the low-affinity subunit. Reaction conditions were identical to those described for panel A except the SULT1A1 (2.0 μM, dimer) was equilibrated with PAPS [8.0 μM, 26Kd(high affinity), 0.27Kd(low affinity)] before being mixed with PAPS at higher concentrations (20–80 μM). kon = 0.96 ± 0.01 μM s–1; koff = 29 ± 1 s–1. All reactions were pseudo-first-order in PAPS concentration.

The 81-fold difference in the affinities of the two PAPS binding sites allows them to be studied in isolation. At the PAPS concentrations used to construct the kobs versus PAPS concentration plot in Figure 2B, the percentage of dimers with two molecules of PAPS bound at equilibrium ranges from 1.5 to 6.3%; hence, the signal from the doubly liganded species is negligible, and kon and koff for the high-affinity site can be obtained from a linear fit of the data. The rate constants associated with binding at the low-affinity site can be obtained using a pre-equilibration strategy. At 8.0 μM PAPS, the equilibrium distribution of enzyme forms is as follows: E, 2.5%; E·PAPS, 76%; E·(PAPS)2, 21%. When this pre-equilibrated solution is mixed with PAPS at concentrations sufficiently high to saturate the second site, one observes conversion of the singly to doubly liganded species with a negligible contribution from other species. The result of such an experiment is shown in Figure 2C, and here again, kon and koff are obtained from the slope and intercept,18 respectively. The accuracy of the four rate constants (kon and koff for high- and low-affinity binding) was tested by using them to predict the kobs values associated with Figure 2A. The predicted values are represented by red dots and closely match the experimental constants.

The Results

The rate constants associated with binding at the high- and low-affinity sites are compiled in Table 1. As the data indicate, the Kd values predicted by these constants are indistinguishable from those obtained from equilibrium binding studies. The off-rate constants reveal that nucleotide escapes from the low-affinity site 41-fold faster than from the high-affinity site. If the cap at the low-affinity site is “held” fully open (≥95%) by binding at the tight site, and the escaping tendency of the nucleotide from the cap-open form of the high- and low-affinity sites is the same, the kon values for binding at the first and second sites will be identical, because the cap in the subunit to which the nucleotide binds is open in both the unliganded and singly liganded enzyme forms. Thus, any fold difference in Kd will be due solely to differences in koff. The results indicate that the changes in Kd (81-fold) and koff (41-fold) differ by a factor of nearly 2 (i.e., 1.93). Within error, this same factor is given by the ratio of the kon values for the low- and high-affinity sites, 2.08. A factor of 2 is readily explained if both subunits of the dimer are capable of binding the first ligand and only one can bind the second. In this scenario, kon for the first site will appear to be 2-fold higher than that for the second because the probability of binding to the first site is twice that of the second, not because kon values for binding to the subunits differ. If, as it appears, this is the case, the aggregate kon for binding to the first site, 2.0 μM–1 s–1, should be halved, to 1.0 μM–1 s–1, and thus the kon values for binding to the first and second sites are identical. In summary, the system behaves precisely as predicted by the adjacent cap open mechanism.

Linking to Acceptor-Site Binding

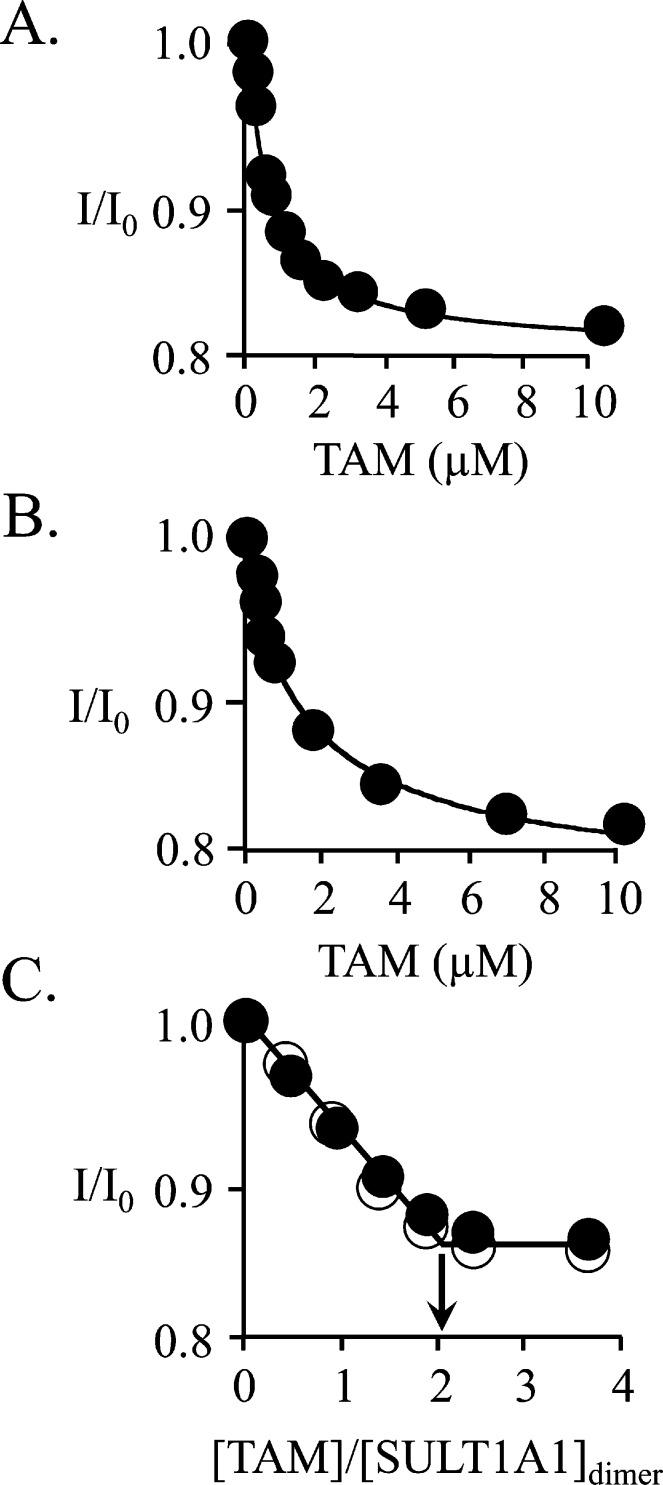

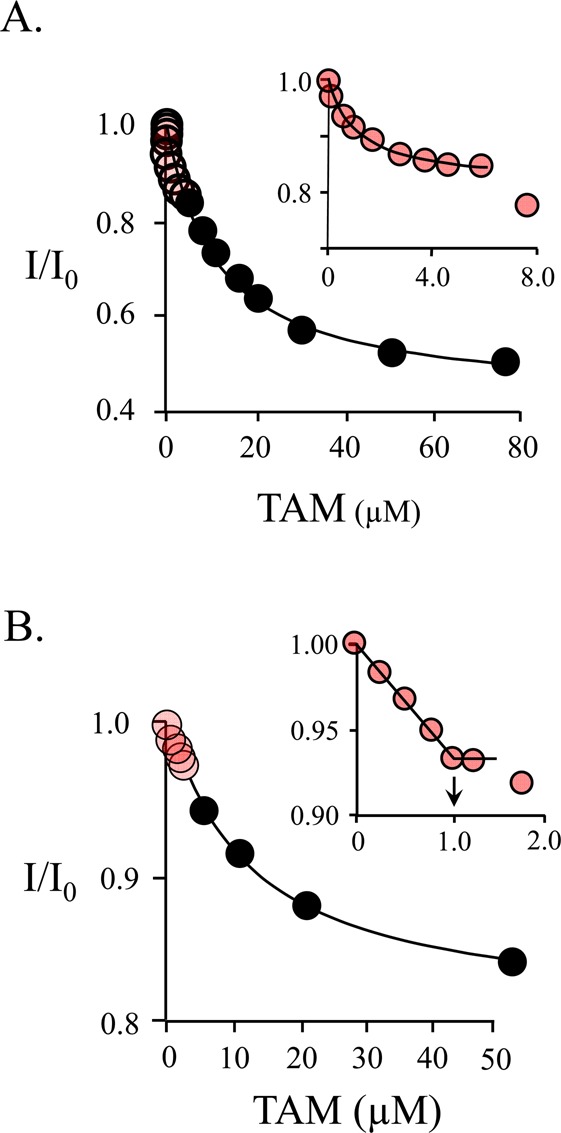

To define how cap behavior is coordinated at the four binding pockets of the enzyme, the PAPS dependence of the open or closed status of the acceptor binding sites was probed using a large acceptor [4-hydroxytamoxifen (TAM)]. As discussed, such acceptors are too large to pass through the pore that forms in response to nucleotide binding. When PAP is bound to SULT1A1, the isomerization equilibrium constant, Kiso, is 26 in favor of pore closure,14 and large acceptors bind 26-fold more weakly to the nucleotide-bound form of the enzyme.14 It should be noted that Kiso values obtained with PAP and PAPS are nearly identical.13

The affinities and stoichiometries of binding of TAM to SULT1A1 at 0 and 0.50 mM PAP (which is sufficient to saturate both nucleotide pockets) were determined by fluorescence titration (Figure 3A–C). The results, compiled in Table 2, reveal that the TAM affinities for E·PAP and E·(PAP)2 are virtually identical (0.67 ± 0.08 and 0.65 ± 0.07 μM, respectively) and that each subunit of the dimer binds one acceptor. In contrast, when the PAP concentration favors the singly nucleotide-bound dimer, TAM binding is biphasic (Figure 4A,B). At 6.0 μM PAP, the distribution of forms is biased toward the E·PAP complex [E·PAP, 79%; E·(PAP)2, 16%; E, 5.0%] and the affinities of the phases (0.67 ± 0.03 and 13 ± 2 μM) strongly suggest that the cap of one subunit is open while that of the other is closed. To confirm that each dimer contains a single high-affinity site, a “stoichiometry” titration was performed at a dimer concentration of 9.0 μM [i.e., 13Kd TAM, 24Kd PAP(high affinity), and 0.3Kd PAP(low affinity)]. To maximize the concentration of singly bound species, the nucleotide concentration was set equal to that of the dimer, 9.0 μM. Under this condition, the distribution of forms is as follows: E·PAP, 77%; E·(PAP)2, 3.8%; E, 19%. Both high- and low-affinity sites are observed in the titration, and the inset reveals that each dimer contains a single high-affinity TAM binding site.

Figure 3.

Binding of TAM to E and E·(PAP)2. (A) TAM binding to E. Binding was monitored via changes in SULT1A1 intrinsic fluorescence (λex = 290 nm; λem = 345 nm). Reaction conditions included SULT1A1 (0.10 μM, dimer), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2 °C. Each point is the average of three independent determinations. The curve is the behavior predicted by a best fit model that assumes a single binding site per dimer. Kd = 0.67 ± 0.04. (B) TAM binding to E(PAP)2. Conditions and data analysis were identical to those described for panel A except PAP = 0.50 mM (17Kd for PAPS binding at its low-affinity site). The Kd for TAM binding is 0.68 ± 0.12 μM. (C) Stoichiometry of binding of TAM to E and E·(PAP)2. Conditions were identical to those described for panels A and B except that [SULT1A1] = 10 μM (dimer). Binding to E and E·(PAP)2 is shown with filled and empty circles, respectively. The stoichiometries are 2.0 ± 0.1 TAM bound per SULT1A1 dimer.

Table 2. TAM and 1-HP Binding to SULT1A1.

| ligand | SULT1A1 species | Kd (μM)a |

|---|---|---|

| TAM | E | 0.67 (0.08) |

| TAM | E·(PAP)2 | 0.65 (0.07) |

| TAM | E·PAP | 13 (2) |

| 1-HP | E | 8 (0.5) |

| 1-HP | E·(PAP)2 | 0.025 (0.001) |

| 1-HP | E·PAP | 0.025 (0.0010) |

Values in parentheses indicate one standard deviation.

Figure 4.

Binding of TAM to SULT1A1. (A) TAM binding is biphasic. Binding was monitored via changes in SULT1A1 intrinsic fluorescence (λex = 290 nm; λem = 345 nm). The titration conditions included SULT1A1 (0.10 μM, dimer), PAP (6.0 μM), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2 °C. The distribution of enzyme forms at 6.0 μM PAP is as follows: E·PAP, 79%; E·(PAP)2, 16%; E, 5.0%. The first phase (red dots, inset) shows binding of TAM to the PAP-free subunit of SULT1A1 (Kd = 0.67 ± 0.05 μM). The second phase shows binding of TAM to the nucleotide-bound subunit (Kd = 13 ± 2 μM). Each point is the average of two independent determinations. The line through the points is the behavior predicted by a best-fit model that assumes a single binding site per dimer. The first and second phases were fit separately using the data indicated by the red and black circles, respectively. (B) Semiquantitative stoichiometric binding of TAM. The conditions of the titration included SULT1A1 (9.0 μM, dimer), PAP (9.0 μM), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2 °C. At these concentrations, the distribution of enzyme forms is as follows: E·PAP, 77%; E·(PAP)2, 3.8%; E, 19%. The binding is biphasic. The first phase (red dots, inset) indicates a stoichiometry of approximately one TAM binding site per dimer. A second low-affinity phase is also observed (black dots).

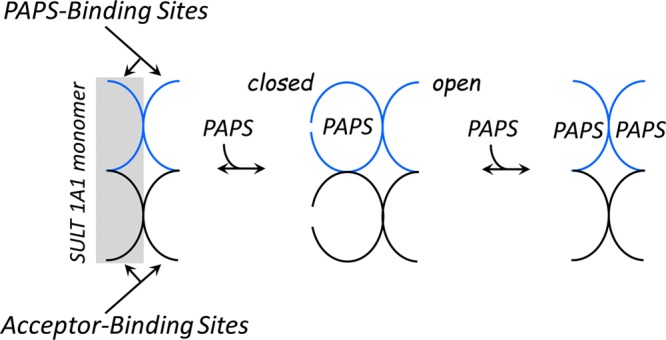

Together, the nucleotide and TAM binding studies indicate that binding of the first nucleotide stabilizes the cap in the adjacent subunit in the open position, and in this configuration, only one acceptor site is open. When the second nucleotide binds, all nucleotide and acceptor sites open. What remains is to determine whether the open acceptor site in the singly occupied enzyme is located on the subunit to which PAPS is bound. This issue is addressed in the following section.

Linking to Reactivity

To assess whether PAPS occupancy influences SULT1A1 reactivity, the initial rate enzyme turnover was studied under conditions in which one or both of the dimer subunits were bound to nucleotide. The initial rate mechanism of SULT1A1 is sequential, rapid equilibrium random;21 that is, a reactive ternary complex can form with either substrate binding first, and substrate binding reactions are near equilibrium during turnover.12,21 In such mechanisms, steady-state affinity constants are excellent approximations of thermodynamic binding constants. Experiments were performed with small and large acceptors [1-hydroxypyrine (1-HP) and TAM]. [35S]PAPS was used to monitor formation of sulfonated TAM (see Materials and Methods and Figure S2 of the Supporting Information). 1-HP and its sulfonated counterpart, 1-HPS, are fluorescent (Figure S3 of the Supporting Information). At the wavelengths used to monitor 1-HPS formation (λex = 320 nm; λem = 380 nm), the fluorescence intensity of 1-HP is ∼1% of that of 1-HPS. To establish experimental benchmarks for the 1-HP studies, the affinities of 1-HP for the three requisite forms of the enzyme [E, E·PAP, and E·(PAP)2] were determined by fluorescence titration (Figure S4A–C of the Supporting Information). The Kd values are compiled in Table 2 and reveal that, like other substrates,22,23 1-HP and nucleotide bind synergistically.

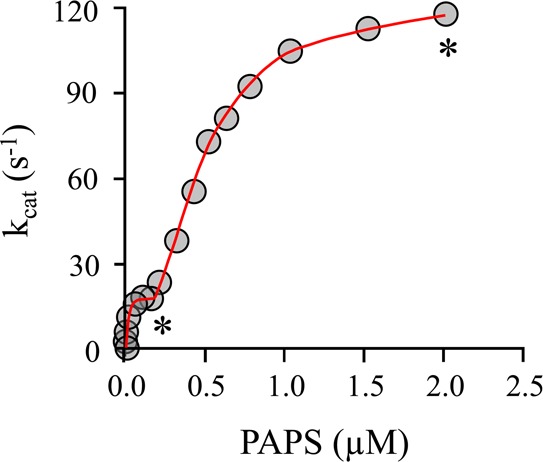

When SULT1A1 turnover is plotted versus PAPS concentration at a saturating 1-HP concentration (Figure 5), distinct low- and high-PAPS affinity phases are observed. To quantitate the differences in initial rate behavior of the singly and doubly occupied enzyme, initial rate experiments were performed at PAPS concentrations fixed in the plateau region of each phase (see asterisks in Figure 5). Table 3 lists the initial rate parameters associated with 1-HP sulfonation and the PAPS concentrations at which they were determined. As expected for a small acceptor, Km for 1-HP is not affected by PAPS occupancy; however, kcat increases nearly 8-fold. If the increased rate of turnover were due solely to PAPS saturation at the second site, a 2-fold increase would have occurred. Thus, as the caps are opened at both sites, each subunit turns over 4 times more quickly than the subunit in the singly occupied enzyme.

Figure 5.

SUTL1A1 turnover as a function of PAPS occupancy. A plot of SULT1A turnover vs [PAPS] is biphasic. The first and second phases correspond to saturation of the high- and low-affinity PAPS binding sites, respectively. The reaction was monitored via 1-HPS fluorescence (λex = 320 nm; λem = 380 nm). The conditions included SULT1A1 (1.0 nM, dimer), 1-HP (160 μM, 20Kd), MgCl2 (5.0 mM), NaPO4 (50 mM), pH 7.2, and 25 ± 2.0 °C. The asterisks indicate the PAPS concentrations (0.20 and 2.0 μM) used in initial rate studies to obtain Michaelis parameters for the E·PAP and E·(PAPS)2 forms.

Table 3. Initial Rate Parameters for E·PAP and E·(PAP)2 Forms of SULT1A1.

| substrate | SULT1A1 species | Km (μM)a | kcat (s–1)a | [PAPS] (μM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-HP | E·PAP | 0.041 (0.002) | 130 (20) | 0.30 |

| 1-HP | E·(PAP)2 | 0.044 (0.03) | 1000 (60) | 2.0 |

| TAM | E·PAP | 14 (1.0) | 2.0 (0.3) | 4.0 |

| TAM | E·(PAP)2 | 0.60 (0.03) | 11 (1.0) | 250 |

Values in parentheses indicate one standard deviation.

Equilibrium binding constants (Table 2) were used to select the PAPS concentrations, 4.0 and 250 μM, used in the TAM initial rate studies. At 4.0 μM PAPS, the majority of SULT1A1 has a single nucleotide bound [E·PAP, 82%; E·(PAP)2, 1.1%; E, 10%]. At 250 μM PAPS, the enzyme is primarily in the doubly occupied form [E·(PAP)2, 89%; E·PAP, 10%; E, <0.1%]. The results are listed in Table 3. The fact that the TAM Km values are nearly identical to their corresponding Kd values (Table 2) confirms that binding is near equilibrium during turnover. On the basis of the TAM equilibrium binding studies, it was not possible to determine whether, for the singly occupied enzyme, the high-affinity TAM binding site is situated on the subunit that is bound to PAPS. If the high-affinity site were located on the PAPS-bound subunit, the Km would equal the high-affinity Kd; if not, it would equal the low-affinity Kd. The TAM Km value, 14 μM, is nearly equal to the Kd for the low-affinity site, 13 μM; hence, the high-affinity binding site is located on the empty subunit of the singly occupied enzyme. The ratio of the TAM Km for the singly and doubly occupied enzyme is 23. This value is nearly equal to the cap isomerization equilibrium constant, 26,14 and indicates that the cap has gone from largely closed to largely opened as the second nucleotide binds, a finding that is completely consistent with the TAM equilibrium binding data.

The results of the initial rate studies clearly indicate that the allosteric interactions that govern nucleotide binding also regulate the reactivity of the enzyme. For small substrates, the effects are primarily on kcat, and the catalytic efficiency (V/K) of the enzyme increases by a factor of ∼8. For large substrates, both kcat and Km are affected, with the result that the efficiency for such substrates increases 130-fold as the system moves from the singly to doubly occupied state. These two states represent end points on a sliding scale of catalytic efficiency whose set point is determined by the nucleotide concentration.

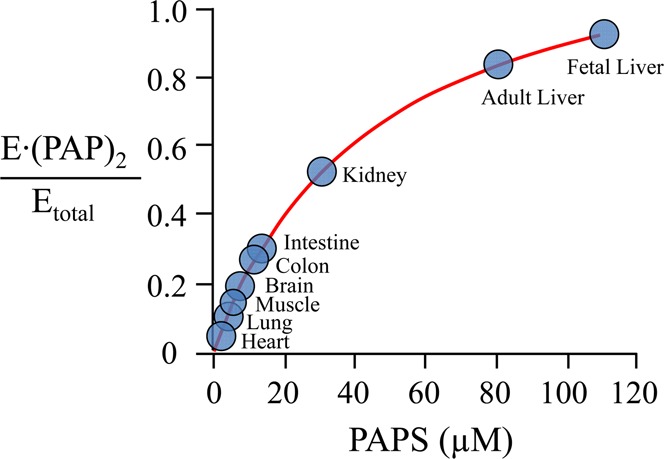

A Biological Raison d’Etre

For the PAPS concentration to be used to regulate SULT1A1 reactivity in the cell, its in vivo concentration must be sufficiently high to populate the second nucleotide binding site. PAPS levels have been quantitated in numerous human tissues that express SULT1A1,24−27 and its concentrations can be calculated using tissue-specific, weight/volume conversion factors.28 While these calculations are gross in that they assume a uniform distribution of nucleotide throughout the tissue, they nevertheless provide a likely lower limit of the cellular PAPS concentration. These concentrations were used to calculate the fraction of dimers that have PAPS bound at both subunits in the various tissues (Figure 6). The calculations predict that PAPS concentrations in all tissues are sufficiently high to saturate the first subunit, but only in certain tissues is it high enough to substantially populate the second.

Figure 6.

Predicted fraction of E·(PAPS)2 in human tissues. Fractions were calculated using reported PAPS concentrations.24−27

As SULT1A1 becomes doubly occupied, kcat increases 8-fold; the catalytic capacity of the system increases by a factor of nearly 10, and Km decreases ∼25-fold for only large substrates. This selective bias places large and small substrates on a catalytic “par”; their kcat/Km values become comparable at double occupancy. One of the important functions of SULT1A1 is to detoxify xenobiotics as they pass through the liver. While this enormous class of compounds is far from fully characterized, many can be classified as large substrates. Thus, in tissues in which the defensive role of SULT1A1 is particularly important, the enzyme seems likely to operate in the double-occupancy mode, which is precisely what the calculations predict. In liver, where the defensive function is arguably the most important of any organ, the enzyme is predicted to be almost entirely in the double-occupancy state. In organs like kidney and intestine, where the demand for defensive function is weaker, but still significant, the curve predicts that the enzyme is balanced between single- and double-occupancy states and is thus poised to respond to PAPS concentration and xenobiotic “load”. Finally, in tissues like heart and brain, where the load is presumably slight, the enzyme is nearly exclusively in its low-efficiency state. In summary, it appears that PAPS concentrations in vivo are indeed sufficiently high to regulate SULT1A1 reactivity, and remarkably, the enzyme’s performance with respect to turnover and substrate specificity will be highly tissue dependent.

Conclusions

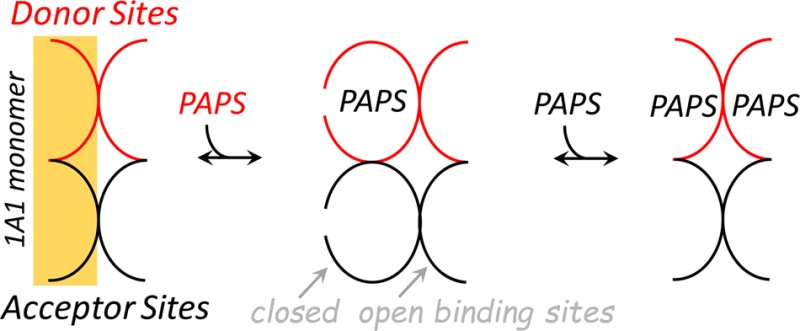

PAPS binds antisynergistically to the subunits of the SULT1A1 dimer. Nucleotide binding at the first subunit causes an 81-fold weakening in the affinity at the second. The decreased affinity is due solely to an increase in the nucleotide off rate constant, which strongly suggests that the cap at the weak affinity site is stabilized in the open position. To determine the cap configurations at all four ligand binding sites as a function of PAPS occupancy, cap positioning at the acceptor pockets was determined using large and small acceptors. PAPS binding at the first site closes both the nucleotide and acceptor cap segments only on the subunit to which PAPS is bound; the cap on the adjacent subunit remains open at both sites. Once the second nucleotide adds, the caps open at all four ligand binding pockets. The coupling of PAPS binding and cap closure is depicted in Figure 7. In this configuration, kcat is increased 8-fold relative to that of the singly PAPS-bound enzyme, and Km decreases 23-fold toward large substrates. Finally, estimates of PAPS concentrations across a variety of tissues suggest that SULT1A1 reactivity will be highly tissue-dependent, and that the enzyme will function in its broadest specificity and highest turnover mode in tissues that experience the highest levels of xenobiotics.

Figure 7.

Coupling of PAPS binding and cap closure in SULT1A1. The ligand binding sites of the unliganded enzyme are open and can receive ligands. Binding of the first PAPS molecule closes both the PAPS and acceptor binding sites of the subunit to which PAPS has bound. In this configuration, PAPS cannot escape and only small acceptors can enter unless the enzyme isomerizes to the open form (not shown), which is unfavorable (Kiso = 26 in favor of the closed state). Consequently, the singly PAPS-bound configuration favors small acceptors. As the second PAPS molecule binds, all of the binding sites open, thus alleviating the catalytic bias against large substrates, and each subunit turns over 4-fold faster.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- HEPES

N-(2-hydroxyethyl)piperazine-N′-2-ethanesulfonic acid

- MBP

maltose binding protein

- PAP

3′,5′-diphosphoadenosine.

Supporting Information Available

Pre-steady-state binding of PAPS to SULT1A1 (Figure S1), TAM initial rate studies (Figure S2), fluorescence spectra of 1-HP and 1-HPS (Figure S3), and 1-HP binding to the E and E·(PAP)2 forms of SULT1A1 (Figure S4). This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Supported by National Institutes of Health Grant GM106158.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Falany J. L.; Macrina N.; Falany C. N. (2002) Regulation of MCF-7 breast cancer cell growth by β-estradiol sulfation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 74, 167–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falany J. L.; Falany C. N. (1996) Regulation of estrogen sulfotransferase in human endometrial adenocarcinoma cells by progesterone. Endocrinology 137, 1395–1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steventon G. B.; Heafield M. T.; Waring R. H.; Williams A. C. (1989) Xenobiotic metabolism in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology 39, 883–887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Falany C. N. (2007) Elevated hepatic SULT1E1 activity in mouse models of cystic fibrosis alters the regulation of estrogen responsive proteins. J. Cystic Fibrosis 6, 23–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K. L. (2003) The biology and enzymology of protein tyrosine O-sulfation. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 24243–24246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell S.; Falany C. N. (2006) Pharmacogenetics of human cytosolic sulfotransferases. Oncogene 25, 1673–1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyh T. S. (1993) The physical biochemistry and molecular genetics of sulfate activation. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 28, 515–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falany C. N. (1997) Enzymology of human cytosolic sulfotransferases. FASEB J. 11, 206–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser T. J. (1994) Role of sulfation in thyroid hormone metabolism. Chem.-Biol. Interact. 92, 293–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson J. F.; Harrison M. (2004) Fulvestrant: Pharmacokinetics and pharmacology. Br. J. Cancer 90(Suppl. 1), S7–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riches Z.; Stanley E. L.; Bloomer J. C.; Coughtrie M. W. (2009) Quantitative evaluation of the expression and activity of five major sulfotransferases (SULTs) in human tissues: The SULT “pie”. Drug Metab. Dispos. 37, 2255–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook I.; Wang T.; Falany C. N.; Leyh T. S. (2012) A Nucleotide-Gated Molecular Pore Selects Sulfotransferase Substrates. Biochemistry 51, 5674–5683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leyh T. S.; Cook I.; Wang T. (2013) Structure, dynamics and selectivity in the sulfotransferase family. Drug Metab. Rev. 45, 423–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook I.; Wang T.; Almo S. C.; Kim J.; Falany C. N.; Leyh T. S. (2013) The gate that governs sulfotransferase selectivity. Biochemistry 52, 415–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook I.; Wang T.; Falany C. N.; Leyh T. S. (2013) High Accuracy In-Silico Sulfotransferase Models. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 34494–34501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang H.; Varlamova O.; Vargas F. M.; Falany C. N.; Leyh T. S. (1998) Sulfuryl transfer: The catalytic mechanism of human estrogen sulfotransferase. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 10888–10892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M.; Leyh T. S. (2010) The human estrogen sulfotransferase: A half-site reactive enzyme. Biochemistry 49, 4779–4785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. (1992) Transient-state kinetic analysis of enzyme reaction pathways. In The Enzymes (Sigman D. S., Ed.) pp 1–61, Academic Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Cleland W. W. (1979) Statistical analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Methods Enzymol. 63, 103–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook I.; Wang T.; Almo S. C.; Kim J.; Falany C. N.; Leyh T. S. (2013) Testing the Sulfotransferase Molecular Pore Hypothesis. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8619–8626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Cook I.; Falany C. N.; Leyh T. S. (2014) Paradigms of Sulfotransferase Catalysis: The Mechanism of SULT2A1. J. Biol. Chem. 289, 26474–26480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyapochkin E.; Cook P. F.; Chen G. (2008) Isotope exchange at equilibrium indicates a steady state ordered kinetic mechanism for human sulfotransferase. Biochemistry 47, 11894–11899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittemore R. M.; Pearce L. B.; Roth J. A. (1986) Purification and kinetic characterization of a phenol-sulfating form of phenol sulfotransferase from human brain. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 249, 464–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brzeznicka E. A.; Hazelton G. A.; Klaassen C. D. (1987) Comparison of adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-phosphosulfate concentrations in tissues from different laboratory animals. Drug Metab. Dispos. 15, 133–135. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappiello M.; Franchi M.; Giuliani L.; Pacifici G. M. (1989) Distribution of 2-naphthol sulphotransferase and its endogenous substrate adenosine 3′-phosphate 5′-phosphosulphate in human tissues. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 37, 317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacifici G. M.; Franchi M.; Colizzi C.; Giuliani L.; Rane A. (1988) Sulfotransferase in humans: Development and tissue distribution. Pharmacology 36, 411–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakakibara Y.; Yanagisawa K.; Katafuchi J.; Ringer D. P.; Takami Y.; Nakayama T.; Suiko M.; Liu M. C. (1998) Molecular cloning, expression, and characterization of novel human SULT1C sulfotransferases that catalyze the sulfonation of N-hydroxy-2-acetylaminofluorene. J. Biol. Chem. 273, 33929–33935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McIntosh R. L.; Anderson V. (2010) A Comprehensive Tissue Properties Database Provided for the Thermal Assessment of a Human at Rest. Biophys. Rev. Lett. 5, 129. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.