Abstract

Background

Partially unroofed coronary sinus (PUCS) is a rare congenital cardiac anomaly and prone to be misdiagnosed. The purpose of this study was to explore the value of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) in CS imaging for the detection of PUCS and to develop a special two-dimensional TEE-based en face view of CS.

Methods

Twenty adult patients with suspected PUCS, showing a dilated coronary sinus and an enlarged right heart on transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), underwent TEE examination. In the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 120°, the en face view of the CS successfully imaged the roof of the CS, which was beyond the realm of the atrial septum, and the interatrial septum was obtained simultaneously in the same view. Meanwhile, the 3D zoom mode could clearly display the comprehensive volume image and the adjacent structures of the PUCS. The results of TEE were compared with the findings of surgery or catheterization.

Results

En face view of the CS was obtained successfully by 2DTEE in 20 patients. In addition, 3DTEE was used for imaging of PUCS in 11 of the 20 patients. PUCS was ultimately confirmed in 13 patients either by surgery or catheterization. The TEE for PUCS diagnosis was consistent with the surgical findings.

Conclusion

Transesophageal echocardiography can be successfully applied to obtain the comprehensive view of CS and its surrounding structures. The en face view of CS provided by 2DTEE may be helpful in better understanding PUCS and discriminating it from associated atrial septal defects.

Keywords: partially unroofed coronary sinus, transesophageal echocardiography, en face view

Partially unroofed coronary sinus (PUCS) is a rare congenital cardiac anomaly characterized by the partial absence of the coronary sinus (CS) roof, leading to a shunt from the left atrium (LA) to the CS and ultimately to the right atrium (RA),1–3 and exhibits similar hemodynamics to that of atrial septal defect (ASD). The diagnosis of PUCS is important to prevent pulmonary hypertension and brain abscess or cerebral emboli.4 Its treatment requires not only the careful assessment of the condition but also of other concomitant cardiac abnormalities to prevent posttreatment hemodynamic complications.5

Before the era of echocardiography, precise diagnosis of PUCS was only possible during a surgical procedure or at autopsy.1 With development in imaging techniques through the decades, transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) has become a readily available modality, which can afford clues to a dilated CS, an enlarged right heart or a left-to-right shunt. However, the technique is limited in its ability to visualize the posterior cardiac structures, such as the CS and pulmonary veins. Hence, it is difficult to discriminate PUCS from the associated ASDs or other congenital abnormalities by TTE. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is a technique that can more accurately assess these posterior cardiac structures; however, in the recent years, the usefulness of two- or three-dimensional TEE in diagnosing congenital or acquired PUCS has been reported only in a few cases.6–8 So, the accurate visualization of the CS and surrounding structures by TEE needs comprehensive experience.

This study was designed to explore the value of TEE in CS imaging for the diagnosis of PUCS and to develop a special two-dimensional (2D) TEE-based en face view of the CS.

Methods

Patient Enrollment

Between April 2003 and September 2011, 20 patients (7 males and 13 females; age range: 18–72 years; mean age: 39 years) admitted at our cardiovascular center with suspected PUCS, showing a dilated coronary sinus and an enlarged right heart on TTE, were referred to this study. Following enrollment, 2DTEE examination was performed for assessment of PUCS. Patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) class III–IV heart failure (stratified by the NYHA functional classification) and patients with anesthetics hypersensitivity history were excluded. After we acquired real time three-dimensional (RT3D) TEE capabilities in May 2009, 11 of the 20 patients were also evaluated using 3DTEE in addition to 2DTEE. Finally, 13 patients underwent surgery or catheterization. This study was approved by our institutional review board, and written informed consents were obtained from all patients.

CS Imaging by TTE

TTE images were obtained with the patient in a left lateral decubitus position and the left arm extended over the head. The parasternal long-axis (PLAX) view and angulated apical four-chamber (A4C) view showed the CS, the transverse diameter or longitudinal diameter of the right chamber, or a left-to-right shunt. The cutoff of 10 mm was set for CS dilatation, and the RV dilatation was defined as the RV to LV transverse diameter ratio at least 1 in A4C. In some cases, a suprasternal window showed the persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC), which drains into the CS. Some patients had valve regurgitation or pulmonary artery hypertension in various degrees, or had complexities present from other concomitant cardiac abnormalities.

CS Imaging by TEE

Lidocaine (2%) throat spray was used as topical pharyngeal anesthesia in all patients. TEE images were obtained, with the patient in the left lateral decubitus position, using a TE-V5M probe on an Acuson Sequoia C256 ultrasound machine (Siemens Medical Solutions, Mountain View, CA) or an X7-2t volume probe on a Philips IE33 ultrasound machine (Philips Medical Systems, Andover, MA), which can afford 2D and live 3D images. Synchronized electrocardiograms were recorded and displayed on the images. The echocardiographic exams were taken by Dr. Fei, Dr. Chen or Dr. Zheng.

In the near-longitudinal plane, atrioventricular chambers and normal pulmonary venous return were documented. In the four-chamber view of the transverse plane, the physician sonographer could observe the septum between the CS and LA on the near-longitudinal plane. With further rotation, the TEE transducer was placed in the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 120°, and the en face view of the CS was obtained behind the left atrium posterior wall and opened into the right atrium between the septum and the posterior leaflet of the tricuspid valve. The roof of the CS, which was beyond the realm of the atrial septum, and the interatrial septum were obtained simultaneously in the same view (movie clips S1–S4).

As the transducer was adjusted to obtain an optimal biplane view of the roof defect, the 3D zoom mode was used to acquire the en face view of the PUCS in 11 patients. To clearly display the comprehensive volume image and the surrounding structures of the PUCS, the size of the 3D echocardiographic sample volume was defined by adjusting the depth position, width, and height using a trackball and dials. The tricuspid valve was also the target structure acquired in the zoom mode.

In addition, in the mid-esophageal plane and at an approximate angle of 90°, the oval foramen and vena cava were visualized, which helped to distinguish between secondary ASD and sinus venosus ASD. In the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 15°, the apical four-chamber plane showed the primary ASD. Every patient was carefully examined for the presence of other concomitant cardiac abnormalities.

Surgical Treatment

Twelve patients underwent open heart surgery. Autologous pericardium was used for patch closure or for roofing of the unroofed coronary sinus. The operative method was based on the anatomical findings.

Cardiac Catheterization Examination

Catheterization examination was performed in 1 patient. The left-to-right atrial shunt was defined by the pulmonary to systemic flow ratio (Qp/Qs), as measured by oximetry using the Fick’s principle.9

Results

TTE Findings

All the 20 adult patients enrolled in the study presented with a dilated coronary sinus and an enlarged right heart. Sixteen of the 20 patients had a definite left-to-right shunt. In 4 other patients, TTE imaging seemed to have a left-to-right shunt and with rich flow signal in CS. One patient was diagnosed with coronary sinus ostium atresia, and 4 patients were diagnosed with a PLSVC concomitantly with PUCS. Aneurysm of the membranous ventricular septum was detected in 1 patient. TTE could not clearly discriminate PUCS from associated ASDs in 2 patients. Besides, 2 patients had mitral valve prolapse, and 1 patient had rheumatic mitral stenosis. The characteristics of the 20 patients are listed in Table1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 20 Adult Patients with Partially Unroofed Coronary Sinus

| No. | Sex | Age (years) | TTE View | TEE View | Surgical Findings | Catheter Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 48 | Suspected PUCS, PLSVC | PUCS, PLSVC, PFO | Same as TEE | – |

| 2 | M | 32 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS, PFO | – | – |

| 3 | F | 32 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS | Same as TEE | – |

| 4 | F | 33 | Suspected PUCS, PLSVC | PUCS, PLSVC | – | – |

| 5 | M | 23 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS, ASDs | Same as TEE | – |

| 6 | F | 42 | Suspected PUCS, PLSVC | PUCS, PLSVC, PFO | Same as TEE | – |

| 7 | F | 72 | Suspected PUCS, PFO | PUCS, PFO | – | – |

| 8 | F | 20 | Suspected PUCS, aneurysm of the membranous ventricular septum | PUCS, aneurysm of the membranous ventricular septum | Same as TEE | – |

| 9 | F | 18 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS | – | – |

| 10 | F | 23 | Suspected PUCS, PLSVC | PUCS, PLSVC, ASDs | Same as TEE | – |

| 11 | F | 69 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS, PFO, stenosis of CS ostium | – | PUCS, PFO |

| 12 | F | 39 | Suspected PUCS, MVP | PUCS, MVP | Same as TEE | – |

| 13 | M | 30 | Suspected PUCS, MVP | PUCS, MVP | Same as TEE | – |

| 14 | F | 38 | Suspected PUCS, PLSVC, CS ostium atresia, MS | PUCS, PLSVC, CS ostium atresia, MS | Same as TEE | – |

| 15 | F | 42 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS | – | – |

| 16 | M | 46 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS | – | – |

| 17 | M | 21 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS | Same as TEE | – |

| 18 | M | 51 | Suspected PUCS, PFO | PUCS, PFO | Same as TEE | – |

| 19 | M | 58 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS | – | – |

| 20 | F | 44 | Suspected PUCS | PUCS | PUCS, PLSVC | – |

PUCS = partially unroofed coronary sinus; PLSVC = persistent left superior vena cava; PFO = patent foramen ovale; ASDs = secondary atrial septal defect; CS = coronary sinus; MVP = mitral valve prolapsed; MS = rheumatic mitral stenosis; Dash (–) indicates not applicable.

2DTEE and 3DTEE Findings

The TEE examinations were performed by Dr. Fei (8/20), Dr. Chen (6/20), and Dr. Zheng (6/20). En face views of the CS (Fig.1) were successfully obtained by 2DTEE in all the 20 patients. TEE showed that all subjects had coronary sinus dilatation and a definite defect, with a shunt from the LA to the CS. One patient with coronary sinus ostium atresia and rheumatic mitral stenosis had a functional PLSVC, which was associated with the atretic CS, leading to a shunt from the LA to the CS and to the PLSVC, via the left innominate vein ultimately to the RA (Fig.2). One patient with PUCS showed dilatation of the CS and stenosis of the CS ostium, in which the maximum velocity of blood flow through the stenosis position was 1.63 m/s (Fig.3A–C).

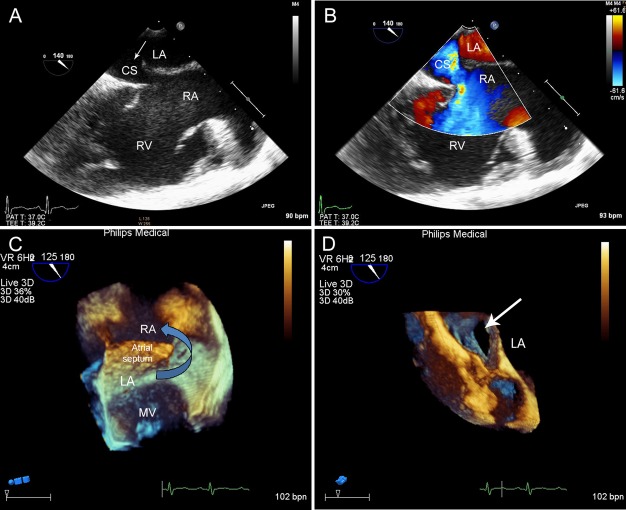

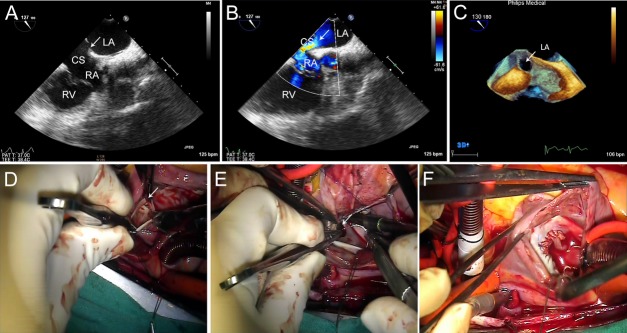

Figure 1.

Imaging results of patient no. 9 (an 18-year-old female with PUCS). En face view of the CS showed the roof of the CS, which beyond the realm of the atrial septum, was partial absent. A. A shunt from the LA to the dilated CS, and ultimately to the RA was confirmed by the color Doppler flow imaging. B. In the 3DTEE image, the arrow shows that the LA is communicating with the RA through the defect. C. The white arrow points to the en face view of the defect. D. PUCS, partially unroofed coronary sinus; LA, left atrium; CS, coronary sinus; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle; MV, mitral valve.

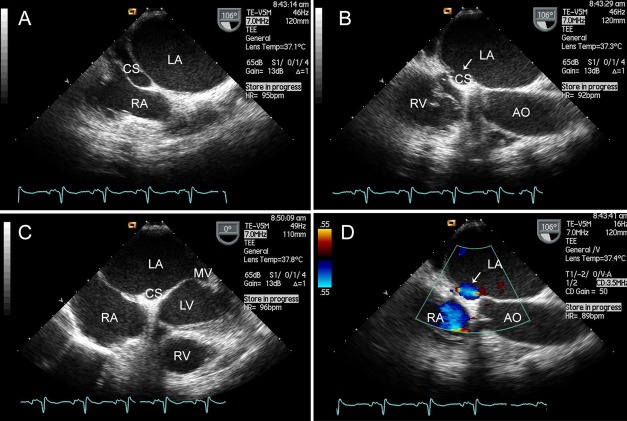

Figure 2.

Patient no. 14 (a 38-year-old female with partially unroofed coronary sinus (PUCS), coronary sinus ostium atresia. A. and rheumatic mitral stenosis. C. The white arrow points to the defect between the LA and the CS. B. The color Doppler flow imaging showed a shunt from the LA to the CS. D. PUCS = partially unroofed coronary sinus; CS = coronary sinus; AO, aorta; LV = left ventricle.

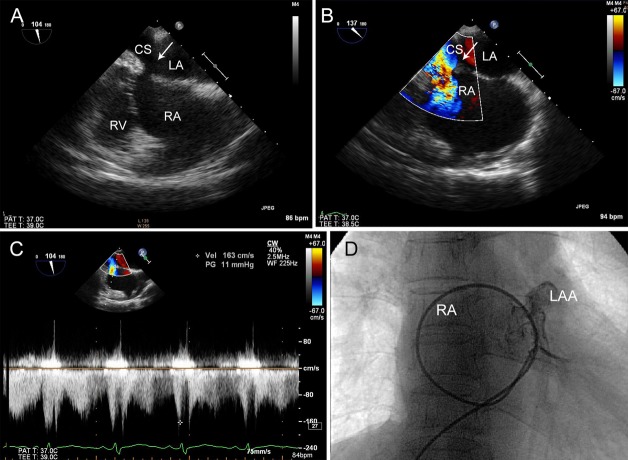

Figure 3.

Patient no. 11 (a 69-year-old female with PUCS). En face view of the CS showed the dilatation of the CS and stenosis of the CS ostium. A. The color Doppler flow imaging confirmed a left-to-right shunt. B. The pulse Doppler imaging showed that the maximum velocity of blood flow through the stenosis position was 1.63 m/s. C. The defect was crossed using a 6 Fr multipurpose catheter, from the inferior vena cava (IVC) to the RA, via the PUCS, ultimately to the LA. Angiography clearly demonstrated the appearance of the left auricular appendage (LAA). D. IVC, inferior vena cava; LAA, left auricular appendage; RA, right atrium; PUCS, partially unroofed coronary sinus; CS, coronary sinus.

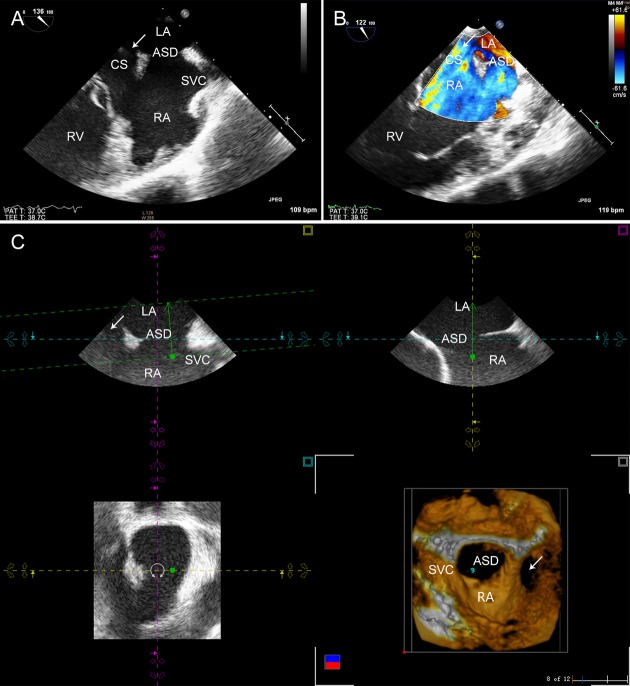

In addition to 2DTEE, 3DTEE was successfully used for volume imaging of the CS defect and the surrounding structures in 11 patients, especially in the 2 patients with an associated ASD (Fig.4). There were no procedural complications.

Figure 4.

Patient no. 10 (a 23-year-old female with partially unroofed coronary sinus (PUCS) and a secondary ASD). En face view of the CS was obtained, as a defect of the atrial septum was visualized simultaneously in the same view. A. The color Doppler flow imaging showed two left-to-right shunts. B. In the 3DTEE image, the white arrow points to the PUCS with an associated secondary ASD, which was close to the SVC. C. ASD, atrial septal defect; SVC, superior vena cava; PUCS, partially unroofed coronary sinus; CS, coronary sinus.

Surgical View and Follow-up

In the surgical view, all subjects showed a defect between the CS and the LA (Fig.5), and there were no operative deaths. One patient had PLSVC, which was missed in TTE and TEE. Follow-up data of TTE were available for 9 of the 12 patients who underwent surgery; the data indicated the absence of a residual shunt and geometry reconstruction of the right heart.

Figure 5.

Patient no. 6 (a 42-year-old-female with PUCS). En face view of the CS showed the roof defect. A, and a left-to-right shunt was confirmed by the color Doppler flow imaging. B. In the 3DTEE image, the white arrow points to PUCS. C. Surgical view from the RA; the white arrows point to the defect. D. Autologous pericardium was used to perform the roof repair. E–F. PUCS = partially unroofed coronary sinus; RA = right atrium.

Cardiac Catheterization

One patient underwent catheterization. The defect was crossed using a 6 Fr multipurpose catheter (Fig.3D), with a large left-to-right atrial shunt (QP/QS 2.45:1) and moderate pulmonary arterial pressure (mean 35 mmHg). Transcatheter occlusion was not attempted due to the risk of coronary sinus obstruction caused by occluding device. Besides, considering the patient’s age, the family refused surgical treatment.

Comparison of TEE Findings with Those of Surgery and Catheterization

Partially unroofed coronary sinus was confirmed in 12 patients via surgery and in 1 patient via catheterization. The TEE for PUCS diagnosis was consistent with the surgical findings.

Discussion

Unroofed coronary sinus, a rare congenital anomaly first described by Raghib and colleagues in 1965,10 is a result of an embryologic error involving imperfect development or complete failure in development of the left atriovenous fold, which is manifested as a focal or complete absence of the CS septum. This abnormality is commonly associated with a PLSVC, which originates at the confluence of the left internal jugular and subclavian veins, and typically drains into the CS, as reported in approximately 75% of patients.11 PUCS is also found in combination with other cardiac abnormalities, such as atrioventricular septal defects, coronary arteriovenous fistula, atresia of the CS ostium, and tetralogy of Fallot.1 In this study, we found that PUCS was associated with coronary sinus ostium atresia, coronary sinus ostium stenosis, or a secondary ASD in some cases (Table1).

Because of the chronic right ventricle volume overload, the size of the PUCS and the degree of the left-to-right shunt generally determine the clinical presentation of this cardiac anomaly.12 However, it is often difficult to diagnose nonspecific clinical signs and symptoms.13,14 Although TTE is the first-line imaging modality, the anatomy of the CS can be difficult to visualize in adults due to the limited sonic window. Noninvasive cross-sectional imaging techniques, such as rapid acquisition or gated techniques of computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance (MR) imaging, are now available and are being increasingly used.2 However, the loss of flow information on the shunt from the LA to the dilated CS, high expenses, noise, and need to inject a contrast medium may limit the clinical application of these techniques. Because of the use of a high-frequency beam and the unique position of the transesophageal transducer behind the left atrium posterior wall, TEE can visualize cardiac structures more availably and accurately, and should therefore be an increasingly used technique in the future.

Based on our experience, the PLAX plane of TTE can visualize the anteroposterior parameter of the enlarged CS behind the LA, and the apical four-chamber plane can visualize the supero-inferior parameter of the CS. A dilated CS and an enlarged right heart on TTE can afford clues to be considered for diagnosis of cardiac abnormalities, such as PUCS, a persistent left SVC to coronary sinus connection concomitantly with a secundum ASD, CS ostial atresia or coronary artery–CS fistulas. However, the image of the septum between the CS and the LA cannot be successfully acquired by TTE—a feature that is important in discriminating PUCS from associated ASDs or other congenital abnormalities. In this study, when the transesophageal (TEE) transducer was placed in the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 120°, the en face view of the CS successfully imaged the roof of the CS, which was beyond the realm of the atrial septum, and the interatrial septum was obtained simultaneously in the same view. The size, shape, location, rim tissue of the PUCS can be demonstrated in TEE imaging. Moreover, when the ultrasound machine was equipped with 3D imaging and biplane 2D echocardiography, the 3D imaging yielded additional volume information on the CS and surrounding structures to the physician sonographer, especially in the patient with an associated ASD. This is an important factor that can facilitate a better interaction between echocardiographers and cardiac surgeons, or interventionalists.15

The type of surgical treatment selected for a PUCS depends on the associated cardiac anomalies and the location of the defect. In our study, the TEE for PUCS diagnosis was consistent with the surgical findings. Therefore, TEE may provide additional information for accurate evaluation of and clinical decision making in patients with PUCS.

Study Limitation

Completely unroofed CS, is rarer than PUCS, almost be in children and was incidentally found during surgeries for other cardiac anomalies. Based on our method, the en face view of the CS was easily and rapidly obtained. The image quality, ease of use, and reproducability of imaging technique have clearly improved markedly after the learning curve. But the en face view of the CS was obtained successfully in PUCS with partially unroofed terminal portion, as the morphologic type IV of unroofed coronary sinus syndrome classified by Kirklin and Barratt-Boyes,16 and was limited in the ability to identify completely unroofed CS or partially unroofed mid-portion. Moreover, in our study, except for the 13 patients with PUCS who underwent surgery or catheterization for the confirmation of PUCS, other patients did not undergo further investigations, such as selected CS angiography, multidetector computed tomography, or MRI to do comparison and support the diagnosis. Meanwhile, the value of TEE to select patient for transcatheter closuring of PUCS needs further study.

Conclusions

This initial study demonstrates that TEE can yield an accurate and comprehensive view of the CS and surrounding structures. The en face view of the CS obtained by 2DTEE may be helpful in better understanding PUCS and differentiating PUCS from the associated ASDs.

Supporting Information

In the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 0°, the four-chamber view was obtained.

Close to an angle of 90°, the mid-esophageal bicaval view was obtained.

With further rotation, in the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 120°, the en face view of the CS was obtained. The roof of the CS, which was beyond the realm of the atrial septum, was partial absent.

A shunt from the LA through the defect to the dilated CS, and ultimately to the RA was confirmed by the color Doppler flow imaging.

References

- Ootaki Y, Yamaguchi M, Yoshimura N. Unroofed coronary sinus syndrome: Diagnosis, classification, and surgical treatment. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2003;126:1655–1656. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5223(03)01019-5. et al: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Choe YH, Park SW. Partially unroofed coronary sinus: MDCT and MRI findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195:W331–W336. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3689. et al: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannavale G, Higgins CB, Ordovas KG. Unroofing the diagnosis. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;26:841–842. doi: 10.1007/s10554-010-9667-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troost E, Gewillig M, Budts W. Percutaneous closure of a persistent left superior vena cava connected to the left atrium. Int J Cardiol. 2006;106:365–366. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders P, Jais P, Hocini M. Electrical disconnection of the coronary sinus by radiofrequency catheter ablation to isolate a trigger of atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2004;15:364–368. doi: 10.1046/j.1540-8167.2004.03300.x. et al: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XS. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Partially unroofed coronary sinus. Circulation. 2007;116:e373. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.717942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acar P, Arran S, Paranon S. Unroofed coronary sinus with persistent left superior vena cava assessed by 3D echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2008;25:666–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2008.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A, Nanda NC, Romp RL. Assessment of surgically unroofed coronary sinus by live/real time three-dimensional transthoracic echocardiography. Echocardiography. 2007;24:74–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8175.2006.00359.x. et al: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thanopoulos BD, Laskari CV, Tsaousis GS. Closure of atrial septal defects with the amplatzer occlusion device: Preliminary results. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1998;31:1110–1116. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00039-4. et al: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghib G, Ruttenberg HD, Anderson RC. Termination of left superior vena cava in left atrium, atrial septal defect, and absence of coronary sinus; a developmental complex. Circulation. 1965;31:906–918. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.31.6.906. et al: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quaegebeur J, Kirklin JW, Pacifico AD. Surgical experience with unroofed coronary sinus. Ann Thorac Surg. 1979;27:418–425. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(10)63339-5. et al: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thangaroopan M, Truong QA, Kalra MK. Images in cardiovascular medicine. Rare case of an unroofed coronary sinus: Diagnosis by multidetector computed tomography. Circulation. 2009;119:e518–e520. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.707018. et al: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdillon PD, Foale RA, Somerville J. Persistent left superior vena cava with coronary sinus and left atrial connections. Eur J Cardiol. 1980;11:227–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adatia I. Gittenberger-de groot AC: Unroofed coronary sinus and coronary sinus orifice atresia. Implications for management of complex congenital heart disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;25:948–953. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00475-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santoro G. Gaio G. Russo MG: Transcatheter treatment of unroofed coronary sinus. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv; 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirklin JW, Barratt-Boyes BG. Cardiac surgery. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1986. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

In the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 0°, the four-chamber view was obtained.

Close to an angle of 90°, the mid-esophageal bicaval view was obtained.

With further rotation, in the mid-esophageal plane and close to an angle of 120°, the en face view of the CS was obtained. The roof of the CS, which was beyond the realm of the atrial septum, was partial absent.

A shunt from the LA through the defect to the dilated CS, and ultimately to the RA was confirmed by the color Doppler flow imaging.