Abstract

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality worldwide and also exerts a significant economic burden, especially in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Detection of subclinical CVD, before an individual experiences a major event, may therefore offer the potential to prevent or delay morbidity and mortality, if combined with an appropriate care response. In this review, we discuss imaging technologies that can be used to detect subclinical atherosclerotic CVD (carotid ultrasound, coronary artery calcification) and non-atherosclerotic CVD (echocardiography). We review these imaging modalities, including aspects such as rationale, relevance, feasibility, utilization, and access in LMICs. The potential gains in detecting subclinical CVD may be substantial in LMICs, if earlier detection leads to earlier engagement with the health care system to prevent or delay cardiac events, morbidity, and premature mortality. Thus, dedicated studies examining the feasibility, utility, and cost-effectiveness of detecting subclinical CVD in LMICs are warranted.

Introduction

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of mortality and loss of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) worldwide.[1] In addition to the health burden, CVD will exert a significant economic burden, on the order of approximately $15 trillion over the next 20 years.[2] While high-income countries have experienced a substantial decline in CVD mortality over the past several decades,[3,4] many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) have higher age-standardized CVD mortality rates than high-income countries.[4,5] Rapid urbanization, mechanization of transport, and increasingly sedentary jobs in LMICs have led to a rise in CVD burden.[6] In combination with a persistent infectious and nutritional disease burden, this has led to a challenging “double burden of disease” in many countries.[7,8] Furthermore, CVD in LMICs affects younger individuals than in high-income countries, which has severe adverse effects for household income, livelihood, and functionality.[9,10,5]

CVD in LMICs manifests as both atherosclerotic and non-atherosclerotic disease, with significant geographic heterogeneity with respect to relative burden of these broad categories of disease.[11–14] Atherosclerotic manifestations of CVD, including ischemic heart disease and stroke, have emerged as the principal causes of death and disability in many parts of Eastern Europe, South Asia, East Asia, North Africa/Middle East, and Latin America.[15–20] On the other hand, non-atherosclerotic CVD, such as rheumatic heart disease and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy, are disproportionately burdensome in sub-Saharan Africa, Southeast Asia, and parts of South Asia.[21,22,16]

Detection of subclinical CVD, before an individual experiences a major event, may therefore offer the potential to prevent or delay morbidity and mortality, if combined with an appropriate care response. Moreover, detection of asymptomatic vascular disease may lead to adoption of risk-mitigating therapies or healthy lifestyles that might lower subsequent CVD risk.[23,24] The full spectrum of cardiovascular imaging technologies exist in many LMICs.[25] However, in this review, we will limit our discussion to carotid ultrasound, coronary calcium scan using computed tomography, and echocardiography, which can be used to detect subclinical atherosclerotic and non-atherosclerotic CVD.

Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

The two bioimaging technologies that we will discuss for detection of subclinical atherosclerotic CVD are carotid ultrasound and coronary calcium scan using computed tomography.

Carotid Ultrasound

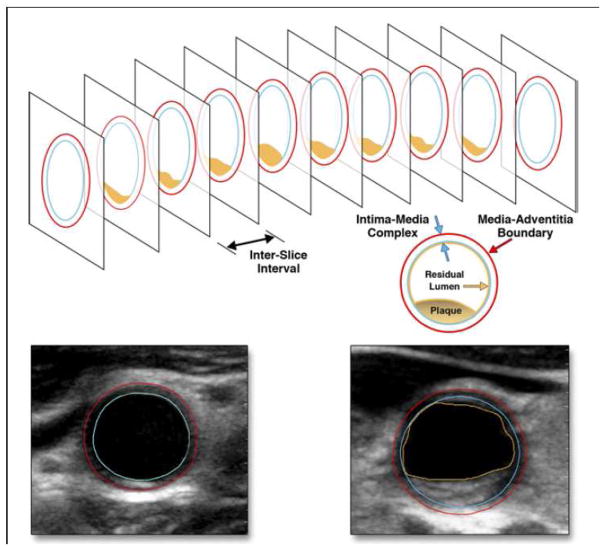

Atherosclerosis is a diffuse process and requires a systematic approach to medical and risk factor management. Since detection of atherosclerosis in the carotid vasculature is associated with coronary atherosclerosis,[26,27] it is a valuable approach to assessing an individual for subclinical atherosclerotic CVD. Although multiple imaging-based modalities exist to assess extra-cranial carotid disease, the most commonly used method in primary prevention settings remains carotid ultrasound (cUS). Measuring carotid intima-media thickness (cIMT), most commonly performed at the carotid bifurcation, has been linked in numerous studies to an increased and independent risk for cardiovascular events.[26] Thus, cIMT has long been considered a marker of atherosclerosis. However, recent studies have shown that approximately 80% of the cIMT complex is comprised of media rather than intima. As atherosclerosis is largely a sub-intimal process, cIMT is no longer considered a reliable marker of atherosclerosis but rather a phenotypic response to aging or hypertension.[28–30] In contrast, cUS may also be used to directly visualize and quantify carotid atherosclerotic plaque (Figure 1).[27,31] Compared to cIMT, carotid plaque-based metrics demonstrate stronger associations with thrombotic events.[32,33,31] To date, most studies evaluating carotid plaque have used either semi-quantitative or binary (present/absent) approaches to measure disease.[34,35] In contrast, a novel approach to quantify carotid atherosclerosis was introduced by the High-Risk Plaque (HRP) BioImage study, a longitudinal cohort of approximately 6,000 asymptomatic United States adults who underwent multimodality vascular imaging.[36] In this study, cUS was used to interrogate the entire length of both right and left common and internal carotid arteries from the angle of the jaw to the clavicle. The cross-sectional areas of all visualized plaques were summed to calculate the overall carotid plaque burden (cPB) for each individual (Figure 2). The overall prevalence of carotid atherosclerosis in this cohort (78%) was much higher than previously reported in other studies using less sensitive methods to detect atherosclerosis.[27] In terms of risk prediction, preliminary findings from the HRP study show that cPB demonstrates a strong and graded association with cardiovascular events over 3 years. Specifically, three-year rates of adverse events among those without any carotid plaque and first, second and third tertiles of cPB were 1.7%, 3.3%, 4.5% and 5.2%, respectively (p<0.001).[37]

Figure 1.

Measurement of carotid plaque vs cIMT using ultrasound imaging. The right carotid of the individual (37-year-old male) is scanned in the transversal plane (short-axis view) from the base of the common carotid up through the bifurcation. An atherosclerotic plaque is seen in the bulb region and marked up as illustrated (A). The far-wall IMT of the common carotid approximately 1 cm from the flow divider is measured and recorded in the longitudinal plane (long-axis view) (B). Reproduced with permission from Singh et al.[38]

Figure 2.

Calculation of the overall carotid plaque burden using carotid ultrasound. Segment of carotid artery with a plaque (orange), which is scanned with a linear array transducer as a series of image slices in transverse section (top). Each image is analyzed with semi-automated software to quantify plaque area, plaque grayscale statistics, percent stenosis, and other metrics of interest. Plaque areas from all images in the entire image sequence were summed as “plaque burden”. Lower left: Common carotid artery with no plaque. The blue border represents the lumen/intima border; the red border represents the media-adventitia boundary. Lower right: Common carotid artery with plaque. The red and blue borders are the same as in previous image, but the orange border represents the boundary of the plaque. Reproduced with permission from Sillesen et al.[27]

Emerging data suggest that cUS may be a feasible method to screen for subclinical atherosclerotic CVD in LMICs. The multinational HAPPY (Heart Attack Prevention Program for You) initiative examined the utility of cUS, performed by non-experts after a single 4-hour training session, in a relatively young (mean age 40 years) rural cohort from Northern India.[38] Each examination took approximately three minutes, and cUS studies were performed in 771 asymptomatic volunteers over a three-day period. Carotid plaques were detected in 69 subjects (8.9%) with a higher prevalence in men compared to women (10% vs. 4%, p=0.02). Although these results highlight the feasibility to train, perform and interpret cUS in a LMIC setting, these findings should be considered within the context of the cohort studied. Specifically, participants were young and tended to be physically active with a healthy diet, which may limit the generalizability of these findings to other populations with less healthy lifestyles. In addition, associations between atherosclerosis detected by cUS and longitudinal outcomes in LMIC cohorts have not been examined in detail. Moreover, whether or not such an imaging-based approach for subclinical atherosclerotic CVD screening will be more cost-effective than traditional CVD risk factor assessment alone remains unknown.

Coronary Calcium Scan

Deposition of calcium within the coronary arteries is considered pathognomonic for coronary artery atherosclerosis, and may be directly quantified with a coronary calcium scan using computed tomography.[39] With the Agatson method,[40] the measurement of coronary artery calcium (CAC) has been largely standardized allowing comparisons across populations and time periods. While the prevalence of CAC varies by gender, age, and race, the absolute amount of CAC is a consistent and independent correlate of adverse events.[41,42] Results from the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, which can be applied with caution to LMIC populations of similar ethnic backgrounds, have shown that both the extent and progression of CAC are strong and independent predictors of adverse events as compared to other modalities such as cIMT.[43,44] The utility of this method as a screening tool for atherosclerosis is reflected in recent guidelines—no other imaging-based modality, with the exception of coronary calcium scanning, was recommended for use in recent American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association lipid-lowering guidelines (Class IIb).[45] Although previous studies have shown the utility of CAC in predicting long-term events,[41] the HRP study demonstrated the impact of CAC for near-term risk prediction. Over an average follow-up of 2.7 years, the extent of CAC among HRP participants was independently associated with a graded risk for adverse events, even after controlling for concomitant carotid atherosclerosis.[37]

Despite the clear epidemiologic links between CAC and adverse events in primary prevention populations in high-income countries, similar data from cohorts in LMIC remain sparse.[46,47] One report from a large urban teaching hospital in Pakistan examined the correlation between CAC scores and coronary luminal obstruction based on CT angiography.[47] Consistent with findings from cohorts in high-income countries, the authors found that low CAC scores (< 10) were associated with a low frequency of obstructive CAD while a majority of subjects (74%) with CAC scores exceeding 400 had severe coronary stenosis.[48] Another study from India found that presence of CAC in an asymptomatic population was associated with traditional atherosclerotic risk factors, such as age, hypertension and diabetes mellitus.[46] These findings notwithstanding, the feasibility, cost implications and predictive utility of CAC in LMIC cohorts remain unknown. For example, while measuring CAC is a largely automated and standardized process, detecting CAC requires large scanners that emit radiation are not portable. Given that coronary calcium scanning involves ionizing radiation, and that CVD affects a relatively younger population in LMICs, the issue of radiation exposure at younger ages may also be another limitation for its widespread use in LMICs.

Non-Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease

Echocardiography is the primary imaging technology for the detection of subclinical non-atherosclerotic CVD.

Echocardiography

Cardiac ultrasound, or echocardiography, has advantages over other cardiovascular imaging modalities and has become the dominant technology in LMICs. There is no ionizing radiation, so there are no radiation safety issues. Echocardiography can be used for a broad range of non-atherosclerotic cardiovascular indications, beyond ischemia evaluation alone, and is already the most commonly used diagnostic imaging tool in cardiology.[49] Because of the fewer infrastructure requirements, it is more adaptable to low-resource settings, and compared to other imaging modalities (i.e. nuclear imaging, magnetic resonance imaging, computed tomography), it is imminently more portable. Echocardiography is well-suited for the epidemiology of CVD in many LMICs, which face a substantial burden of non-atherosclerotic CVD.[21,22,16,50] Given the relative predominance of valvular heart disease, cardiomyopathies, and hypertensive heart disease in many LMICs, echocardiography is the primary bio-imaging technology for these regions.

Rheumatic heart disease (RHD), a dominant cause of valvular heart disease in LMICs, is a disease for which echocardiography can help with management. The worldwide prevalence of RHD is estimated to be 15.6 million cases, with 233,000 deaths per year.[51] However, these estimates may underestimate the true prevalence of subclinical RHD, as recent echocardiography-based screening studies have demonstrated.[52] Although the valvular lesions of RHD have classic and distinctive auscultatory patterns detected by stethoscope, even highly trained specialists vary in their ability to detect RHD with the stethoscope alone, compared to echocardiography with low levels of training.[53] Effective image quality has been demonstrated, even by individuals with no prior training in echocardiography, prior to mass RHD screening.[54] Multiple studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in the mass screening setting.[55,56] Earlier detection of RHD can lead to treatment that may delay progression to advanced disease, although the link between early detection of RHD and impact on prognosis is still debated.[57,58] The World Heart Federation has proposed criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis and recommends screening in high-prevalence regions.[59]

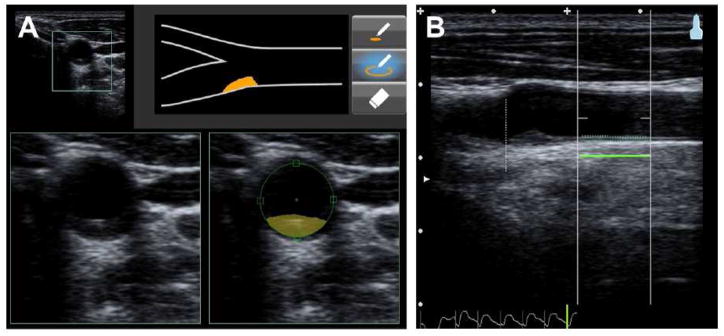

Handheld echocardiography has recently been developed and numerous studies have demonstrated feasibility and applicability in low-resource settings with studies performed by non-cardiologists, especially as these devices have become smaller while maintaining some of the sophistication of larger machines (Figure 3).[60–62] Early studies from the 1990s required portable generator use,[63] by the 2000s, ultrasounds were hand-carried and battery-operated,[64] and in the 2010s, these devices can now fit in the same pocket that once would carry a stethoscope.[65]

Figure 3.

Photograph of the Vscan handheld ultrasound (GE Healthcare, Wauwatosa, WI) being used in a medical mission to Honduras where patients were screened for cardiovascular disease. Used with permission from Monica Mukherjee, M.D.[84]

Because of the potential for misapplication or incorrect interpretation of echocardiographic images by non-expert imagers,[66] remote interpretation has been evaluated to provide greater access to accurate interpretation.[67] In the past, such consultation has required dedicated satellite connections and custom wireless transmitters.[68] However, with the expansion of access to broadband internet connectivity, this kind of teleconsultation is now no longer prohibitively resource-intensive, and rapid remote interpretation can be provided on a mass scale.[69] This may be especially useful if local expert interpretation is not available. For example, the World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease are complex and may require expert interpretation,[59] which could be facilitated by this type of remote image interpretation.

In summary, echocardiography can be a powerful tool to direct treatment pathways for non-atherosclerotic CVD. For instance, in sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of cardiomyopathy cases are non-atherosclerotic in etiology. Thus, simple parasternal and subcostal views to quickly establish right ventricular size, left ventricular systolic function and the existence of any valvulopathy can effectively differentiate between cardiomyopathy, right-sided heart failure, rheumatic disease, or congenital heart disease.[50]

Access to Imaging and Clinical Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries

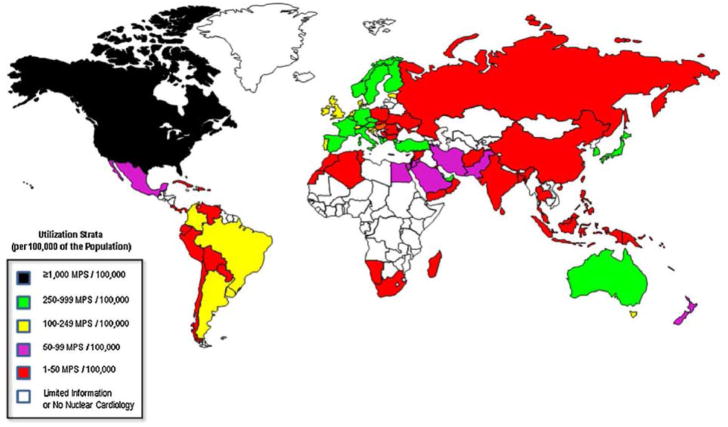

Bio-imaging for subclinical CVD may be technically feasible and available in many LMICs, but there exist marked disparities in utilization (Figure 4).[25] Limited resources and lack of available health care infrastructure in LMICs may introduce unique challenges in widespread implementation of these technologies. Cardiovascular imaging is concentrated in capital cities,[70] with higher use in border states of “high user” nations.[71] However, these services are often provided on a fee-for-service basis with the cost prohibitive for all but the highest echelons of wealth in those countries. For example, stress SPECT MPI in India costs $180, which is a significant burden in the context of an average monthly middle-class income of $500.[72]

Figure 4.

Illustration of worldwide utilization of nuclear cardiology procedures (per 100,000 population). Reproduced with permission from Vitola et al.[71]

Even when imaging technologies are available, in many LMICs they may not be sufficiently utilized. For example, although cUS is mobile and relatively inexpensive, acquisition and interpretation of images requires experienced technicians and readers, particularly when making precise measurements of area. Training for technicians is nearly non-existent in most LMICs,[67] leading to more than half of installed equipment being not utilized secondary to inadequate servicing or lack of operators.[73] When these technologies are used, problems are further compounded by lack of accreditation processes which may lead to patient and operator safety oversights.[74]

Health care delivery systems also need to be developed alongside the implementation of imaging to detect subclinical CVD. The benefit of early detection would be lost if there was no means to seek additional medical attention after an abnormality is found. For example, in West Africa there are no pediatric cardiac surgery centers, and in Ghana only 20 percent of children diagnosed with congenital heart disease could afford surgery within one year of echocardiographic diagnosis.[75] In Brazil, the mean waiting time for coronary artery bypass graft surgery was 23 months with a 6% annual mortality rate on the waiting list; for heart valve surgery, the wait time was reported at 32 months with a 13% annual mortality.[76] Surgical missions funded by international charities cannot meet the overwhelming demand in LMICs for those with surgical CVD, and are also not sustainable long-term solutions. Instead, building local capacity (physical, technical, and human) is critically important. In addition to surgical treatment options, access to medicines remains a formidable challenge.[77] Among patients with atherosclerotic CVD, less than 25% have been found to use evidence-based medicines such as antiplatelet drugs, beta blockers, and statins,[78] with correspondingly worse statistics in LMICs. The development of care delivery systems, both surgical and medical, must dovetail with diagnostic referrals if bio-imaging for subclinical CVD is to actually aid the population to prevent or delay events, morbidity, and premature mortality due to CVD. The potential promise of earlier detection of subclinical CVD can be realized if preventive, lower-cost, and early therapeutic measures could slow progression to later stages that require prohibitively costly intervention.

In part, this will require funding for CVD control that needs to be re-aligned in order to correspond to the burden on LMIC populations. Development assistance for health that is allocated to CVD and other non-communicable diseases is very low relative to the burden of these diseases in LMICs.[79–81] In fact, many donor countries have policy bans against funds for non-communicable diseases.[82] These trends must change in order to improve the alignment of health financing and disease burden. Efforts to promote universal health coverage and healthy life expectancy have the potential to improve efforts at CVD prevention and control, but this would also require careful attention to structures of global governance that impact health and related sectors.[83]

In summary, issues related to access, feasibility, and integration within a comprehensive care delivery system need to be addressed in the context of implementation and utilization of bio-imaging for the detection of subclinical CVD in LMICs. In addition to the issues described above, further documentation and experience is required to demonstrate that these bio-imaging technologies can be equitably utilized and accessed outside of research settings. Policymakers at all levels—global, national, and local—need to take these issues into account when considering the expansion of these technologies in LMIC settings.

Conclusions

There are many potential challenges and issues that need to be addressed regarding the consideration of using bio-imaging for the detection of subclinical CVD in LMICs. However, the potential gains in detecting subclinical CVD may be substantial in LMICs, if earlier detection leads to earlier engagement with the health care delivery system in a fashion that prevents or delays subsequent cardiac events, morbidity, and premature mortality. Thus, dedicated studies examining the feasibility, predictive utility, and cost-effectiveness of detecting subclinical CVD in LMICs are warranted.

Acknowledgments

Funding: RV is supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number K01 TW 009218 - 03.

The authors would like to thank Claire Hutchinson for editorial assistance.

Abbreviations (in alphabetical order)

- CAC

Coronary artery calcium

- cIMT

Carotid intima-media thickness

- cPB

Carotid plaque burden

- cUS

Carotid ultrasound

- CVD

Cardiovascular disease

- DALY

Disability-adjusted life years

- HRP

High-Risk Plaque

- LMICs

Low- and middle-income countries

- RHD

Rheumatic heart disease

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Adair T, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Barker-Collo S, Bartels DH, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bhalla K, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Boufous S, Bucello C, Burch M, Burney P, Carapetis J, Chen H, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahodwala N, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ezzati M, Feigin V, Flaxman AD, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Franklin R, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gonzalez-Medina D, Halasa YA, Haring D, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Hoen B, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Keren A, Khoo JP, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Ohno SL, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Mallinger L, March L, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGrath J, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Michaud C, Miller M, Miller TR, Mock C, Mocumbi AO, Mokdad AA, Moran A, Mulholland K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KM, Nasseri K, Norman P, O’Donnell M, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Phillips D, Pierce K, Pope CA, 3rd, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Raju M, Ranganathan D, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Rivara FP, Roberts T, De Leon FR, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Salomon JA, Sampson U, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Segui-Gomez M, Shepard DS, Singh D, Singleton J, Sliwa K, Smith E, Steer A, Taylor JA, Thomas B, Tleyjeh IM, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Undurraga EA, Venketasubramanian N, Vijayakumar L, Vos T, Wagner GR, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Wilkinson JD, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh PH, Yip P, Zabetian A, Zheng ZJ, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380 (9859):2095–2128. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61728-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bloom DE, Cafiero ET, Jané-Llopis E, Abrahams-Gessel S, Bloom LR, Fathima S, Feigl AB, Gaziano T, Mowafi M, Pandya A, Prettner K, Rosenberg L, Seligman B, Stein AZ, Weinstein C. The Global Economic Burden of Noncommunicable Diseases. World Economic Forum. Geneva: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levi F, Lucchini F, Negri E, La Vecchia C. Trends in mortality from cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases in Europe and other areas of the world. Heart. 2002;88 (2):119–124. doi: 10.1136/heart.88.2.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ, Naghavi M. Temporal trends in ischemic heart disease mortality in 21 world regions, 1980 to 2010: the global burden of disease 2010 study. Circulation. 2014;129 (14):1483–1492. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.004042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran AE, Roth GA, Narula J, Mensah GA. 1990–2010 Global Cardiovascular Disease Atlas. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):3–16. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuckler D. Population causes and consequences of leading chronic diseases: a comparative analysis of prevailing explanations. The Milbank quarterly. 2008;86 (2):273–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2008.00522.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Remais JV, Zeng G, Li G, Tian L, Engelgau MM. Convergence of non-communicable and infectious diseases in low- and middle-income countries. International journal of epidemiology. 2013;42 (1):221–227. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bygbjerg IC. Double burden of noncommunicable and infectious diseases in developing countries. Science. 2012;337 (6101):1499–1501. doi: 10.1126/science.1223466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reddy KS. India wakes up to the threat of cardiovascular diseases. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50 (14):1370–1372. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.04.097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leeder S, Raymond S, Greenberg H. A Race Against Time: The Challenge of Cardiovascular Disease in Developing Economies. Trustees of Columbia University; New York: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett DA, Krishnamurthi RV, Barker-Collo S, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Connor M, Lawes CMM, Moran AE, Anderson LM, Roth GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJL, Feigin VL. The Global Burden of Ischemic Stroke: Findings of the GBD 2010 Study. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):107–112. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnamurthi RV, Moran AE, Forouzanfar MH, Bennett DA, Mensah GA, Lawes CMM, Barker-Collo S, Connor M, Roth GA, Sacco R, Ezzati M, Naghavi M, Murray CJL, Feigin VL. The Global Burden of Hemorrhagic Stroke: A Summary of Findings From the GBD 2010 Study. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):101–106. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moran AE, Tzong KY, Forouzanfar MH, Roth GA, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJL, Naghavi M. Variations in Ischemic Heart Disease Burden by Age, Country, and Income: The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors 2010 Study. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):91–99. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sampson UKA, Fowkes FGR, McDermott MM, Criqui MH, Aboyans V, Norman PE, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Song Y, Harrell FE, Denenberg JO, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray C. Global and Regional Burden of Death and Disability From Peripheral Artery Disease: 21 World Regions, 1990 to 2010. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):145–158. e121. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moran A. East Asia. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):53–58. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moran A. South Asia. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moran A. Central Europe. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moran A. Eastern Europe & Central Asia. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):77–82. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moran A. North Africa & Middle East. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):17–22. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moran A. Latin America & Caribbean. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moran A. Sub-Saharan Africa. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moran A. Southeast Asia. Global Heart. 2014;9 (1):59–64. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2014.03.2448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalia NK, Miller LG, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, Agrawal N, Budoff MJ. Visualizing coronary calcium is associated with improvements in adherence to statin therapy. Atherosclerosis. 2006;185 (2):394–399. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orakzai RH, Nasir K, Orakzai SH, Kalia N, Gopal A, Musunuru K, Blumenthal RS, Budoff MJ. Effect of patient visualization of coronary calcium by electron beam computed tomography on changes in beneficial lifestyle behaviors. The American journal of cardiology. 2008;101 (7):999–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Michelis KC, Choi BG. Cardiovascular Imaging in the Developing World. In: Mollura DJ, editor. Radiology and Global Health: Implementation and Optimization of Imaging Services in the Developing World. Springer Publishing; New York: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lorenz MW, Markus HS, Bots ML, Rosvall M, Sitzer M. Prediction of clinical cardiovascular events with carotid intima-media thickness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation. 2007;115 (4):459–467. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.628875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sillesen H, Muntendam P, Adourian A, Entrekin R, Garcia M, Falk E, Fuster V. Carotid plaque burden as a measure of subclinical atherosclerosis: comparison with other tests for subclinical arterial disease in the High Risk Plaque BioImage study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2012;5 (7):681–689. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2012.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finn AV, Kolodgie FD, Virmani R. Correlation between carotid intimal/medial thickness and atherosclerosis: a point of view from pathology. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2010;30 (2):177–181. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.173609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cuspidi C, Lonati L, Sampieri L, Pelizzoli S, Pontiggia G, Leonetti G, Zanchetti A. Left ventricular concentric remodelling and carotid structural changes in essential hypertension. Journal of hypertension. 1996;14 (12):1441–1446. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199612000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linhart A, Gariepy J, Giral P, Levenson J, Simon A. Carotid artery and left ventricular structural relationship in asymptomatic men at risk for cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 1996;127 (1):103–112. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)05940-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spence JD, Eliasziw M, DiCicco M, Hackam DG, Galil R, Lohmann T. Carotid plaque area: a tool for targeting and evaluating vascular preventive therapy. Stroke. 2002;33 (12):2916–2922. doi: 10.1161/01.str.0000042207.16156.b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ebrahim S, Papacosta O, Whincup P, Wannamethee G, Walker M, Nicolaides AN, Dhanjil S, Griffin M, Belcaro G, Rumley A, Lowe GD. Carotid plaque, intima media thickness, cardiovascular risk factors, and prevalent cardiovascular disease in men and women: the British Regional Heart Study. Stroke. 1999;30 (4):841–850. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.4.841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rundek T, Arif H, Boden-Albala B, Elkind MS, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Carotid plaque, a subclinical precursor of vascular events: the Northern Manhattan Study. Neurology. 2008;70 (14):1200–1207. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303969.63165.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lamina C, Meisinger C, Heid IM, Lowel H, Rantner B, Koenig W, Kronenberg F. Association of ankle-brachial index and plaques in the carotid and femoral arteries with cardiovascular events and total mortality in a population-based study with 13 years of follow-up. European heart journal. 2006;27 (21):2580–2587. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Meer IM, Bots ML, Hofman A, del Sol AI, van der Kuip DA, Witteman JC. Predictive value of noninvasive measures of atherosclerosis for incident myocardial infarction: the Rotterdam Study. Circulation. 2004;109 (9):1089–1094. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000120708.59903.1B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muntendam P, McCall C, Sanz J, Falk E, Fuster V. The BioImage Study: novel approaches to risk assessment in the primary prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease--study design and objectives. American heart journal. 2010;160 (1):49–57. e41. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Baber UFV. Detection and Impact of Subclinical Coronary and Carotid Atherosclerosis on Cardiovascular Risk Prediction and Reclassification In Asymptomatic US Adults: Insights from the High Risk Plaque BioImage Study. American College of Cardiology Scientfic Sessions; Washington DC: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Singh S, Naga A, Maheshwar P, Panwar R, Hecht H, Fukumoto T, Bansal M, Panthagani D, Lammertin G, Kasliawal R, MIshra H, Hosfstra L, Singh MP, Fuster V, Sengupta PP, Narula J. Rapid Screening for Subclinical Atherosclerosis by Carotid Ultrasound Examination. the HAPPY (Heart Attack Prevention Program for You) Substudy. Global Heart. 2013;8 (2):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Becker CR, Knez A, Ohnesorge B, Schoepf UJ, Flohr T, Bruening R, Haberl R, Reiser MF. Visualization and quantification of coronary calcifications with electron beam and spiral computed tomography. Eur Radiol. 2000;10 (4):629–635. doi: 10.1007/s003300050975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agatston AS, Janowitz WR, Hildner FJ, Zusmer NR, Viamonte M, Jr, Detrano R. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1990;15 (4):827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Budoff MJ, Shaw LJ, Liu ST, Weinstein SR, Mosler TP, Tseng PH, Flores FR, Callister TQ, Raggi P, Berman DS. Long-term prognosis associated with coronary calcification: observations from a registry of 25,253 patients. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2007;49 (18):1860–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2006.10.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Budoff MJ, Hokanson JE, Nasir K, Shaw LJ, Kinney GL, Chow D, Demoss D, Nuguri V, Nabavi V, Ratakonda R, Berman DS, Raggi P. Progression of coronary artery calcium predicts all-cause mortality. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3 (12):1229–1236. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Folsom AR, Kronmal RA, Detrano RC, O’Leary DH, Bild DE, Bluemke DA, Budoff MJ, Liu K, Shea S, Szklo M, Tracy RP, Watson KE, Burke GL. Coronary artery calcification compared with carotid intima-media thickness in the prediction of cardiovascular disease incidence: the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA) Archives of internal medicine. 2008;168 (12):1333–1339. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Budoff MJ, Young R, Lopez VA, Kronmal RA, Nasir K, Blumenthal RS, Detrano RC, Bild DE, Guerci AD, Liu K, Shea S, Szklo M, Post W, Lima J, Bertoni A, Wong ND. Progression of coronary calcium and incident coronary heart disease events: MESA (Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61 (12):1231–1239. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stone NJ, Robinson J, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Lloyd-Jones DM, Blum CB, McBride P, Eckel RH, Schwartz JS, Goldberg AC, Shero ST, Gordon D, Smith SC, Jr, Levy D, Watson K, Wilson PW. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wasnik A, Raut A, Morani A. Coronary calcium scoring in asymptomatic Indian population: correlation with age, gender and risk factors--a prospective study on 500 subjects. Indian Heart J. 2007;59 (3):232–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bhulani N, Khawaja A, Jafferani A, Baqir M, Ebrahimi R, Sajjad Z. Coronary calcium scoring: are the results comparable to computed tomography coronary angiography for screening coronary artery disease in a South Asian population? BMC Res Notes. 2013;6:279. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-6-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.van Werkhoven JM, Schuijf JD, Gaemperli O, Jukema JW, Kroft LJ, Boersma E, Pazhenkottil A, Valenta I, Pundziute G, de Roos A, van der Wall EE, Kaufmann PA, Bax JJ. Incremental prognostic value of multi-slice computed tomography coronary angiography over coronary artery calcium scoring in patients with suspected coronary artery disease. European heart journal. 2009;30 (21):2622–2629. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehp272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheitlin MD, Alpert JS, Armstrong WF, Aurigemma GP, Beller GA, Bierman FZ, Davidson TW, Davis JL, Douglas PS, Gillam LD, Lewis RP, Pearlman AS, Philbrick JT, Shah PM, Williams RG, Ritchie JL, Eagle KA, Gardner TJ, Garson A, Gibbons RJ, O’Rourke RA, Ryan TJ. ACC/AHA guidelines for the clinical application of echocardiography: executive summary. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines (Committee on Clinical Application of Echocardiography). Developed in collaboration with the American Society of Echocardiography. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 1997;29 (4):862–879. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(96)90000-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kwan GF, Bukhman AK, Miller AC, Ngoga G, Mucumbitsi J, Bavuma C, Dusabeyezu S, Rich ML, Mutabazi F, Mutumbira C, Ngiruwera JP, Amoroso C, Ball E, Fraser HS, Hirschhorn LR, Farmer P, Rusingiza E, Bukhman G. A simplified echocardiographic strategy for heart failure diagnosis and management within an integrated noncommunicable disease clinic at district hospital level for sub-Saharan Africa. JACC Heart failure. 2013;1 (3):230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2013.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carapetis JR, Steer AC, Mulholland EK, Weber M. The global burden of group A streptococcal diseases. The Lancet infectious diseases. 2005;5 (11):685–694. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70267-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Marijon E, Celermajer DS, Tafflet M, El-Haou S, Jani DN, Ferreira B, Mocumbi AO, Paquet C, Sidi D, Jouven X. Rheumatic heart disease screening by echocardiography: the inadequacy of World Health Organization criteria for optimizing the diagnosis of subclinical disease. Circulation. 2009;120 (8):663–668. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.849190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Carapetis JR, Paar P, Cherian T. Standardization of epidemiologic protocols for surveillance of post-streptococcal sequelae: acute rheumatic fever, rheumatic heart disease and acute post-streptococcal glomerulonephritis 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reeves BM, Kado J, Brook M. High prevalence of rheumatic heart disease in Fiji detected by echocardiography screening. Journal of paediatrics and child health. 2011;47 (7):473–478. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carapetis JR, Hardy M, Fakakovikaetau T, Taib R, Wilkinson L, Penny DJ, Steer AC. Evaluation of a screening protocol using auscultation and portable echocardiography to detect asymptomatic rheumatic heart disease in Tongan schoolchildren. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2008;5 (7):411–417. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saxena A, Ramakrishnan S, Roy A, Seth S, Krishnan A, Misra P, Kalaivani M, Bhargava B, Flather MD, Poole-Wilson PP. Prevalence and outcome of subclinical rheumatic heart disease in India: the RHEUMATIC (Rheumatic Heart Echo Utilisation and Monitoring Actuarial Trends in Indian Children) study. Heart. 2011;97 (24):2018–2022. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2011-300792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zuhlke L, Mayosi BM. Echocardiographic screening for subclinical rheumatic heart disease remains a research tool pending studies of impact on prognosis. Current cardiology reports. 2013;15 (3):343. doi: 10.1007/s11886-012-0343-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Roberts K, Colquhoun S, Steer A, Remenyi B, Carapetis J. Screening for rheumatic heart disease: current approaches and controversies. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2013;10 (1):49–58. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Remenyi B, Wilson N, Steer A, Ferreira B, Kado J, Kumar K, Lawrenson J, Maguire G, Marijon E, Mirabel M, Mocumbi AO, Mota C, Paar J, Saxena A, Scheel J, Stirling J, Viali S, Balekundri VI, Wheaton G, Zuhlke L, Carapetis J. World Heart Federation criteria for echocardiographic diagnosis of rheumatic heart disease--an evidence-based guideline. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2012;9 (5):297–309. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2012.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Saxena A, Zühlke L, Wilson N. Echocardiographic Screening for Rheumatic Heart Disease: Issues for the Cardiology Community. Global Heart. 2013;8 (3):197–202. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson BP, Sanghvi A. Point-of-Care Cardiac Ultrasound: Feasibility of Performance by Noncardiologists. Global Heart. 2013;8 (4):293–297. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nelson BP, Narula J. How Relevant Is Point-of-Care Ultrasound in LMIC? Global Heart. 2013;8 (4):287–288. doi: 10.1016/j.gheart.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Anabwani GM, Bonhoeffer P. Prevalence of heart disease in school children in rural Kenya using colour-flow echocardiography. East Afr Med J. 1996;73 (4):215–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kobal SL, Lee SS, Willner R, Aguilar Vargas FE, Luo H, Watanabe C, Neuman Y, Miyamoto T, Siegel RJ. Hand-carried cardiac ultrasound enhances healthcare delivery in developing countries. The American journal of cardiology. 2004;94 (4):539–541. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.04.077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Choi BG, Mukherjee M, Dala P, Young HA, Tracy CM, Katz RJ, Lewis JF. Interpretation of remotely downloaded pocket-size cardiac ultrasound images on a web-enabled smartphone: validation against workstation evaluation. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2011;24 (12):1325–1330. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2011.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Melamed R, Sprenkle MD, Ulstad VK, Herzog CA, Leatherman JW. Assessment of left ventricular function by intensivists using hand-held echocardiography. Chest. 2009;135 (6):1416–1420. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Everton KL, Mazal J, Mollura DJ Group R-ACW . White paper report of the 2011 RAD-AID Conference on International Radiology for Developing Countries: integrating multidisciplinary strategies for imaging services in the developing world. Journal of the American College of Radiology: JACR. 2012;9 (7):488–494. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Huffer LL, Bauch TD, Furgerson JL, Bulgrin J, Boyd SY. Feasibility of remote echocardiography with satellite transmission and real-time interpretation to support medical activities in the austere medical environment. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2004;17 (6):670–674. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2004.03.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Singh S, Bansal M, Maheshwari P, Adams D, Sengupta SP, Price R, Dantin L, Smith M, Kasliwal RR, Pellikka PA, Thomas JD, Narula J, Sengupta PP, Investigators A-RS. American Society of Echocardiography: Remote Echocardiography with Web-Based Assessments for Referrals at a Distance (ASE-REWARD) Study. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography: official publication of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2013;26 (3):221–233. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2012.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zaidi H. Medical physics in developing countries: looking for a better world. Biomedical imaging and intervention journal. 2008;4 (1):e29. doi: 10.2349/biij.4.1.e29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Vitola JV, Shaw LJ, Allam AH, Orellana P, Peix A, Ellmann A, Allman KC, Lee BN, Siritara C, Keng FY, Sambuceti G, Kiess MC, Giubbini R, Bouyoucef SE, He ZX, Thomas GS, Mut F, Dondi M. Assessing the need for nuclear cardiology and other advanced cardiac imaging modalities in the developing world. Journal of nuclear cardiology: official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2009;16 (6):956–961. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9104-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lele VR, Soman P. Nuclear cardiology in India and the developing world: opportunities.. and challenges! Journal of nuclear cardiology: official publication of the American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. 2009;16 (3):348–350. doi: 10.1007/s12350-009-9073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Essential Health Technologies Strategy 2004–2007. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Mollura DJ, Shah N, Mazal J Group ftR-ACW. White paper report of the 2013 RAD-AID conference on international radiology for developing countries: access to radiology services in limited resource regions. Journal of the American College of Radiology. doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2014.03.026. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Edwin F, Sereboe LA, Tettey MM, Aniteye EA, Kotei DA, Tamatey MM, Entsua-Mensah K, Frimpong-Boateng K. Experience from a single centre concerning the surgical spectrum and outcome of adolescents and adults with congenitally malformed hearts in West Africa. Cardiology in the young. 2010;20 (2):159–164. doi: 10.1017/S1047951109990679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Haddad N, Bittar OJ, Pereira AA, da Silva MB, Amato VL, Farsky PS, Ramos AI, Sampaio M, Almeida TL, Armaganijan D, Sousa JE. Consequences of the prolonged waiting time for patient candidates for heart surgery. Arquivos brasileiros de cardiologia. 2002;78 (5):452–465. doi: 10.1590/s0066-782x2002000500003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kishore SP, Vedanthan R, Fuster V. Promoting global cardiovascular health ensuring access to essential cardiovascular medicines in low- and middle-income countries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57 (20):1980–1987. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.12.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Yusuf S, Islam S, Chow CK, Rangarajan S, Dagenais G, Diaz R, Gupta R, Kelishadi R, Iqbal R, Avezum A, Kruger A, Kutty R, Lanas F, Lisheng L, Wei L, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Oguz A, Rahman O, Swidan H, Yusoff K, Zatonski W, Rosengren A, Teo KK. Use of secondary prevention drugs for cardiovascular disease in the community in high-income, middle-income, and low-income countries (the PURE Study): a prospective epidemiological survey. Lancet. 2011;378 (9798):1231–1243. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(11)61215-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dieleman JL, Graves CM, Templin T, Johnson E, Baral R, Leach-Kemon K, Haakenstad AM, Murray CJ. Global health development assistance remained steady in 2013 but did not align with recipients’ disease burden. Health Aff (Millwood) 2014;33 (5):878–886. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sridhar D, Batniji R. Misfinancing global health: a case for transparency in disbursements and decision making. Lancet. 2008;372 (9644):1185–1191. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61485-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nugent R, Feigl A. Where Have All the Donors Gone? Scarce Donor Funding for Non-Communicable Diseases. Center for Global Development; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 82.WHO Reform Process Submission - The NCD Alliance. The NCD Alliance; London: [Google Scholar]

- 83.Sridhar D, Brolan CE, Durrani S, Edge J, Gostin LO, Hill P, McKee M. Recent shifts in global governance: implications for the response to non-communicable diseases. PLoS Med. 2013;10 (7):e1001487. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Honduras Medical Mission Trip. GW Heart & Vascular Institute; [Accessed May 9, 2014]. http://www.gwheartandvascular.org/index.php/community-outreach/honduras-medical-mission-trip/ [Google Scholar]