Abstract

Introduction

No consensus exists for post-hepatectomy venous thromboembolic (VTE) prophylaxis. Factors impacting VTE prophylaxis patterns among hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgeons were defined.

Method

Surgeons were invited to complete a web-based survey on VTE prophylaxis. The impact of physician and clinical factors was analysed.

Results

Two hundred responses were received. Most respondents were male (91%) and practiced at academic centres (88%) in the United States (80%). Surgical training varied: HPB (24%), transplantation (24%), surgical oncology (34%), HPB/transplantation (13%), or no specialty (5%). Respondents estimated VTE risk was higher after major (6%) versus minor (3%) resections. Although 98% use VTE prophylaxis, there was considerable variability: sequential compression devices (SCD) (91%), unfractionated heparin Q12h (31%) and Q8h (32%), and low-molecular weight heparin (39%). While 88% noted VTE prophylaxis was not impacted by operative indication, 16% stated major resections reduced their VTE prophylaxis. Factors associated with the decreased use of pharmacologic prophylaxis included: elevated international normalized ratio (INR) (74%), thrombocytopaenia (63%), liver insufficiency (58%), large EBL (46%) and complications (8%). Forty-seven per cent of respondents wait until ≥post-operative day 1 (POD1) and 35% hold pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis until no signs of coagulopathy. A minority (14%) discharge patients on pharmacologic prophylaxis. While 81% have institutional VTE guidelines, 79% believe hepatectomy-specific guidelines would be helpful.

Conclusion

There is considerable variation regarding VTE prophylaxis among liver surgeons. While most HPB surgeons employ VTE prophylaxis, the methods, timing and purported contraindications differ significantly.

Introduction

The development of venous thromboembolism (VTE) in the peri-operative period can be a devastating complication with high morbidity and mortality. Strategies to prevent the development of VTE include sequential compression devices (SCD) and pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis. The use of pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis can reduce the incidence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and (pulmonary embolism) PE by about 75% among general surgery patients.1,2 For the majority of abdominal operations, peri-operative pharmacological VTE prophylaxis is now considered the standard of care for patients with a moderate-to-high risk of developing a VTE.3,4 Most patients undergoing a liver resection would be considered moderate-to-high risk,5 as VTE within 90 days of a hepatic resection has been reported to occur in nearly 1 in 12 patients.6,7 Liver surgeons, however, are often worried about the potential for post-operative haemorrhage after a hepatectomy and may not be inclined to utilize peri-operative pharmacological VTE prophylaxis.

The decision whether to employ peri-operative VTE prophylaxis, and the type of prophylaxis (e.g. SCDs vs. pharmacologic VTE prophylaxis), often relies on the individual surgeons assessment of the relative risk of developing a VTE versus post-operative haemorrhage for a particular patient and operation. Further complicating a liver surgeon’s decision on prophylaxis are the numerous available types of VTE prophylaxis [SCD, unfractionated heparin (UFH), low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH)], as well as the varied dosing interval associated with pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (e.g. q 12 h vs. q 8 h). Historically, some surgeons have perceived the risk of VTE after a liver resection to be lower than for other major abdominal procedures owing to transient liver dysfunction sometimes reflected in an increased prothrombin time and international normalized ratio (INR). Barton et al. 8 found, however, that in spite of elevated INR values, thromboelastography actually demonstrated a brief hypercoagulable state after a liver resection. Other studies have similarly noted that VTE risk may actually increase with more extensive hepatic resections even in the setting of increased post-operative INR levels.9,10 Even patients suffering from chronic liver insufficiency do not appear to be anticoagulated based on elevated INR levels and may actually be at an increased risk of VTE.11,12

Owing to a lack of data on VTE-related outcomes after a hepatectomy, current practice guidelines regarding prophylaxis for patients undergoing a liver resection remain unclear. While some institutions have formalized ‘current best practices’ around prophylaxis for VTE after a hepatic resection, other centres have not. Although there is a perceived large amount of heterogeneity in practice patterns among liver surgeons, the degree of this variability has not been previously defined or quantitated. In the present study, we hypothesized that a wide array of factors might influence the choice of whether to administer VTE prophylaxis around the time of a hepatic resection. We sought to determine current VTE prophylaxis patterns among practicing hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB) surgeons and define what clinical factors impact their choice and timing of VTE prophylaxis.

Methods

Key clinical factors were incorporated into a 35-question survey that was designed to evaluate current VTE prophylaxis patterns among surgeons who perform liver surgery (Appendix S1). The survey instrument was divided into three sections focused on data collection regarding: (i) details on surgeon demographics and training, (ii) surgeon perception and assessment of VTE risks, practice patterns and opinions on VTE prophylaxis utilization, and (iii) VTE guidelines. In particular, the respondent was asked which VTE prophylaxis (s)he would recommend around the time of liver resection, when prophylaxis is typically initiated, as well as the type of prophylaxis preferred (e.g. SCD, UFH, LMWH). In addition, specific questions were aimed at identifying which clinical factors the respondent utilized in making decisions regarding VTE prophylaxis at the time of liver resection. The clinical factors which we asked respondents to evaluate for a potential impact on VTE prophylaxis included: a prior history of DVT/ PE, hypercoaguable diagnosis, obesity, cancer diagnosis, co-morbidities, combined operations, post-operative complications, elevated INR values, liver insufficiency, large volume blood loss and major versus minor liver resections. All co-authors reviewed the survey for validity and we did a small pilot of sending the survey to all HPB faculties in the participating departments.

Invitations to take the survey were sent by e-mail to surgical members of the Americas Hepato-Pancreatobiliary Association, International Hepato-Pancreatobiliary Association and Surgical Society of the Alimentary Tract, with self-reported interests in liver surgery; e-mail addresses were obtained from publicly available sources such as web sites and publications in the field.13,14 Response to the survey was voluntary and anonymous; no financial incentive was offered to encourage participation. After the initial distribution of the survey, we scheduled three automatic email reminders at 2-week intervals to all non-responders, which were coded with a unique identification number. The survey was sent to 414 email addresses and opening the email was considered confirmation that the email address was correct and the survey was viewed. The questionnaire was available online through QuestionPro (a survey engine). The study protocol and survey instrument were approved by the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine Institutional Review Board.

35-question survey

Descriptive statistics were compared using Fisher’s exact test, the rank-sum test, or the Kruskal–Wallis test, as appropriate. Choice data were analysed using multinomial logistic regression models with robust variance estimates, yielding odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) that reflect the change in the odds of choosing a particular therapy over an alternative. For each of the 10 different VTE prophylaxis patterns examined a separate regression model was created that included factors of clinical significance including: gender, country of practice, private or community hospital vs. academic or university hospital, fellowship, years after training and practice pattern. All tests of statistical significance were two-sided, and statistical significance was established at P < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using Stata/MP 10.1 for Windows (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

The email was sent to 414 recipients, 297 recipients opened the email, and 200 responded. Demographic and practice characteristics of the respondents are given in Table 1. The majority of respondents (88%) practiced at academic centres, and 55% were in practice ≥10 years. The overwhelming majority of respondents were male (91%) and practiced in the United States (81%). Surgical training varied: 34% surgical oncology, 24% transplant, 24% HPB, 13% combined HPB/transplant and 5% no fellowship training. Most respondents (67%) reported that the majority (>50%) of their clinical practice involved HPB surgery. Respondents reported performing a median of four [interquartile range (IQR) 2–5] liver resections per month, with half (50%) of the resections being major (≥3 segments) (IQR 34–70).

Table 1.

Surgeon demographics and practice characteristics of respondents (n = 200)

| Characteristics | Value, No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Male gender, No. (%) | 181 (91) |

| Country, US, No.(%) | 161 (81) |

| Fellowship, No.(%) | |

| Surgical Oncology Fellowship | 68 (34) |

| Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Fellowship | 48 (24) |

| Transplant Fellowship | 48 (24) |

| Combined hepato-pancreato-biliary and Transplant Fellowship | 25 (13) |

| None | 11 (6) |

| Years after completion of training, No.(%) | |

| ≤10 years | 91 (46) |

| 11–20 years | 65 (33) |

| 21–30 years | 34 (17) |

| >30 years | 10 (5) |

| Primary practice setting, No.(%) | |

| Academic practice or university hospital staff | 175 (88) |

| Private practice or community hospital staff | 24 (12) |

| Hepato-pancreato-biliary practice | |

| ≥75% | 93 (47) |

| 50–74% | 40 (20) |

| 25–49% | 34 (17) |

| <25% | 33 (17) |

| Number of liver resection per month, median (IQR) | 4 (2–5) |

| Major resection(≥3 segments), %, median (IQR) | 50 (34–70) |

IQR, interquartile range.

Responses to attitudinal questions of respondents regarding the method and timing of VTE prophylaxis patterns were assessed. The overwhelming majority (98%) of respondents routinely used VTE prophylaxis. There was considerable variability, however, regarding which VTE prophylaxis modalities were employed: 91% SCD, 39% LMWH, 32% UFH every 8 h and 31% UFH every 12 h (Table 2). When asked to assess the risk of VTE among patients undergoing a liver resection, respondents had a variable estimate. Specifically, 4% of respondents estimated the risk to be <1%, whereas 69% estimated the risk at 1–6%, 17% at 7–9%, and 10% thought the risk of VTE after liver resection was >10%. Of note, respondents estimated the risk of VTE to be higher after a major versus minor resection (mean estimated risk: 7% vs. 4%, respectively; P < 0.001). In spite of this, 16% of respondents noted that they were less likely to administer pharmacological VTE prophylaxis after a major resection compared with a minor resection. In general, respondent estimates for VTE risk varied based on the indication for surgery: benign (2%) vs. malignant (5%) disease (P < 0.001). However, 88% of respondents stated that the likelihood of administering pharmacological VTE prophylaxis did not change based on the indication for surgical resection.

Table 2.

Method and timing of respondents’ VTE prophylaxis patterns

| Type of DVT/PE prophylaxis (multiple choice) | No. (%) |

|---|---|

| Sequential compression devices | 176 (91.2) |

| Low molecular weight heparin | 76 (39.4) |

| Unfractionated heparin q8 hours | 61 (31.6) |

| Unfractionated heparin q12 hours | 59 (30.6) |

| Time of administering DVT/PE prophylaxis | No. (%) |

| POD 0 | 103 (53.4) |

| POD ≥ 1 | 90 (46.6) |

| Hold administering of pharmacologic DVT/PE prophylaxis until laboratory values demonstrate no signs of coagulopathy or bleeding | (%) |

| Strongly agree and Agree | 34.2 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 13.8 |

| Strongly disagree and Disagree | 52.0 |

VTE, venous thromboembolic; DVT, deep vein thrombosis; PE, pulmonary embolism, POD, post-operative day.

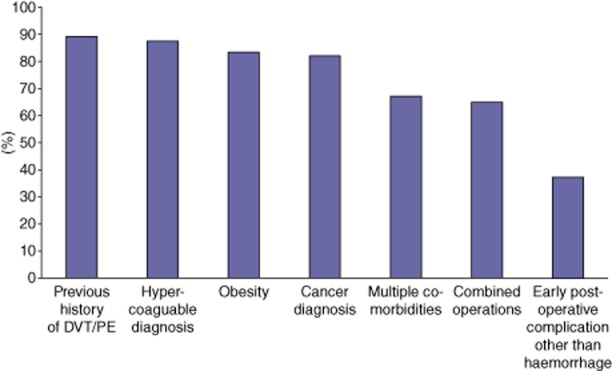

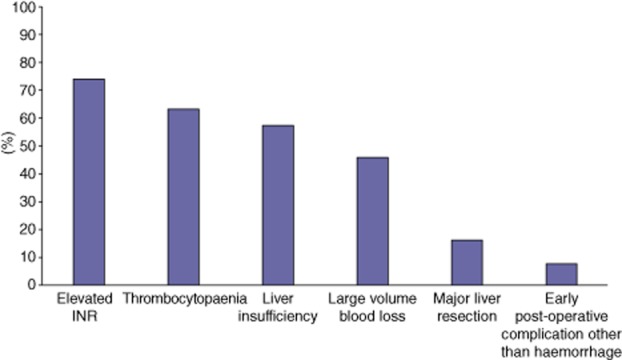

Factors that most respondents did state would increase their likelihood of administering pharmacological VTE prophylaxis after a hepatectomy included: a history of DVT/PE (89%), a hypercoaguable diagnosis (88%), obesity (84%), multiple medical co-morbidities (67%), combined operations (65%) and early post-operative complications other than haemorrhage (38%) (Fig. 1). In contrast, factors that influenced respondents to choose not to use pharmacological VTE prophylaxis included: elevated INR (74%), thrombocytopaenia (63%), liver insufficiency (58%), large operative blood loss (46%) and an early post-operative complication (7%) (Fig. 2). With regard to the timing of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis initiation, 47% of respondents reported that they routinely waited until post-operative day (POD) 1 or longer and 35% stated that they routinely hold pharmacological VTE prophylaxis until there are no objective signs of coagulopathy. While only 17% of respondents indicated that they believe pharmacological VTE prophylaxis increased the risk of post-operative bleeding, 15% stated that they have had at least one bleeding complication that they believe was directly attributable to pharmacological VTE prophylaxis administration. Among all respondents, 28% reported that they believed routine administrative of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis pre-operatively was unnecessary; this proportion increased to 59% when respondents were asked about patients undergoing only a minor liver resection. Twenty-two per cent of respondents stated that their VTE prophylaxis pattern changed based on the extent of liver resection. Of note, 14% of respondents noted that they routinely discharge patients home on pharmacological VTE prophylaxis after hepatic resections.

Figure 1.

Proportion of respondents identifying factor as increasing likelihood of administering pharmacological deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE) prophylaxis

Figure 2.

Proportion of respondents identifying factor as decreasing likelihood of administering pharmacological deep vein thrombosis (DVT)/pulmonary embolism (PE) prophylaxis

Surgeon-specific factors were evaluated for differences in self-reported practice patterns regarding thromboembolic prophylaxis. While there were no differences in timing of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis associated with surgeon demographics or training experience, self-reported surgeon HPB volume influenced pharmacological VTE prophylaxis practice patterns. Compared with lower volume HPB surgeons, surgeons who described their practice as >75% HPB estimated that the risk of VTE was lower for both minor (5% vs. 3%, respectively; P < 0.001) and major hepatectomies (8% vs. 6%, respectively; P = 0.01) (Table 3). In addition, compared with lower volume HPB surgeons, surgeons who self-reported a practice consisting of >75% HPB cases stated using pharmacological VTE prophylaxis a mean duration of 1.5 days longer (4.6 vs. 6.1 days, P = 0.03) after a liver resection. Attitudes towards pharmacological VTE prophylaxis were also impacted by factors such as academic versus community hospital status, as well as geographical location of the provider. Specifically, surgeons who practiced in a community setting were more likely to believe that the administration of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis increased the risk of post-operative surgical bleeding (OR 6.77, 95% CI 2.66–17.22; P < 0.001). Furthermore, surgeons practicing in the United States were more likely to use SCD (OR 3.62, 95% CI 1.47–8.94; P = 0.005), as well as UFH every 8 h as pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (OR 4.80, 95% CI 1.62–14.17; P = 0.005). In contrast, surgeons from the United States were less likely to report using LMWH as pharmacological VTE prophylaxis (OR 0.38, 95% CI 0.19–0.77; P = 0.008). United States surgeons were also less likely to report the practice of discharging patients home on pharmacological VTE prophylaxis after hepatic resections (OR 0.37, 95% CI 0.15–0.87; P = 0.02).

Table 3.

Clinical factors associated with patterns of VTE prophylaxis use among hepato-pancreato-biliary surgeons

| Patterns of VTE prophylaxis | OR | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hold prophylaxis administration until there are no signs of coagulopathy | |||

| Clinical care >75% | Ref | ||

| Clinical care ≤75% | 0.55 | 0.30–1.01 | 0.05 |

| Send patients home on pharmacological prophylaxis | |||

| Non-US surgeon | Ref | – | – |

| US surgeon | 0.37 | 0.15–0.87 | 0.02 |

| Clinical care >75% | Ref | ||

| Clinical care ≤75% | 3.82 | 1.54–9.48 | 0.004 |

| Sequential compression | |||

| Non-US surgeon | Ref | – | – |

| US surgeon | 3.62 | 1.47–8.94 | 0.005 |

| Unfractionated heparin q12 | |||

| ≤10 years after completion of training | Ref | – | – |

| 11–20 years | 1.59 | 0.78–3.24 | 0.20 |

| 21–30 years | 2.33 | 1.01–5.40 | 0.05 |

| >30 years | 1.43 | 0.34–6.02 | 0.63 |

| Unfractionated heparin q8 | |||

| Non-US surgeon | Ref | – | – |

| US surgeon | 4.80 | 1.62–14.17 | 0.005 |

| ≤10 years after completion of training | Ref | – | – |

| 11–20 years | 0.37 | 0.18–0.75 | 0.01 |

| 21–30 years | 0.29 | 0.11–0.76 | 0.01 |

| >30 years | 0.33 | 0.07–1.66 | 0.18 |

| LMWH | |||

| Non-US surgeon | Ref | – | – |

| US surgeon | 0.38 | 0.19–0.77 | 0.008 |

| Administering prophylaxis increases the risks of surgical bleeding | |||

| Private practice or community hospital | Ref | – | – |

| Academic practice or university hospital | 0.15 | 0.06–0.38 | <0.001 |

| Postoperative prophylaxis is necessary | |||

| Major resection >51% | Ref | ||

| Major resection ≤50% | 0.22 | 0.08–0.62 | 0.004 |

| All patients should receive prophylaxis before and after liver resection | |||

| Non-US surgeon | Ref | – | – |

| US surgeon | 2.28 | 1.06–4.90 | 0.04 |

| ≤10 years after completion of training | Ref | – | – |

| 11–20 years | 0.59 | 0.27–1.28 | 0.18 |

| 21–30 years | 0.31 | 0.13–0.76 | 0.01 |

| >30 years | NA | ||

| Patients undergoing a minor liver resection should receive both pre and post operative prophylaxis | |||

| ≤10 years after completion of training | Ref | – | – |

| 11–20 years | 0.68 | 0.35–1.32 | 0.25 |

| 21–30 years | 0.38 | 0.17–0.84 | 0.02 |

| >30 years | 0.24 | 0.06–1.02 | 0.05 |

Each of the 10 statistical regression models the same independent variables which include gender, country of practice, private or community hospital vs. academic or university hospital, fellowship, years after training, and practice pattern.

VTE, venous thromboembolic; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin; US, United States; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Regarding general attitudes about VTE guidelines and practice patterns at their hospital, 88% of respondents reported a belief that a major variation in pharmacological VTE prophylaxis patterns existed among HPB surgeons. Most respondents (81%) indicated that their own institution had guidelines on VTE prophylaxis and most surgeons (80%) reported adherence to the recommended hospital guidelines. However, only 52% of respondents believed that their institutional VTE guides were actually based on data relevant for patients undergoing HPB surgery and 79% of respondents stated that consensus guidelines specific for a hepatectomy would be useful in their practice.

Discussion

Liver surgeons face a challenging dilemma in deciding on the method and timing of VTE prophylaxis after a hepatectomy. Several recent studies have demonstrated that the occurrence of VTE after a hepatectomy is not uncommon and the incidence ranges from 2.1% to 4.7%.6,9,10,15–18 In the past, liver surgeons have been reluctant to initiate pharmacological prophylaxis because of the perception that these patients may be at a lower risk of developing VTE events and a higher risk of post-operative bleeding than other surgical procedures. However, a review of 5651 NSQIP patients undergoing liver surgery revealed that the risk of VTE was higher after major hepatic resections and outweighed the risk of bleeding.10 In fact, these investigators found that patients who experienced a VTE had a 30-day mortality of 7.4% versus 2.3% for those patients who did not have a VTE event.10 The American College of Chest Physicians has recommended the use of chemoprophylaxis over no prophylaxis in surgical patients of moderate-to-high risk.3 In turn, based on the widely used and externally validated Caprini risk scoring system, most patients undergoing a liver resection would be considered moderate-to-high risk.5 However, owing to the perceived risk of possible peri-operative bleeding after a hepatectomy, this recommendation is only grade 2C.19,20 Provider perceptions about these guideline recommendations, as well as surgeon VTE practice patterns, have been poorly characterized. The current study is important because it utilized a broad-based multi-institutional survey to define surgeon attitudes and practices around VTE prophylaxis after a liver resection. We found that considerable practice variation exists among liver surgeons. Interestingly, while 98% of surgeons routinely use VTE prophylaxis, the methods and timing of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis varied significantly.

While most surgeons utilized SCDs (91%) in combination with pharmacological VTE prophylaxis, some employed UFH (61%) and others LMWH (39%). The reported high frequency use of combined pharmacological VTE prophylaxis and SCDs in our study is in agreement with current recommendations against mechanical methods as monotherapy for cancer patients.21 Regarding the choice of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis, there are three randomized trials comparing LMWH and UFH for pharmacological VTE prophylaxis in cancer22,23 and colorectal surgery24 patients, all of whom appear to show similar efficacy with LMWH and UFH. However, meta-analyses evaluating different dosing regimens of these drugs demonstrate that UFH given every 8 h, as well as daily LMWH, are superior to UFH given twice daily.2,25 This is noteworthy, because roughly one-third of respondents are utilizing UFH twice daily.

There are no studies evaluating the optimal timing of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis for hepatectomies; however, current international guidelines for patients undergoing cancer surgery recommends initiation of pharmacological VTE prophylaxis 2–12 h pre-operatively.21 A large proportion of respondents do not appear to be following these guidelines for patients undergoing a hepatectomy; 47% of respondents stated that they routinely wait until POD 1 and 35% until there are no signs of coagulopathy before initiating pharmacological VTE prophylaxis. Similarly, in spite of data to suggest that the risk of VTE remains elevated for at least 12 weeks after surgery,3 only 14% of liver surgeons routinely send patients home on pharmacological VTE prophylaxis. This may be important because Tzeng et al. 17 found that 29% of all VTE after a hepatectomy occurred post-discharge.

Based upon somewhat limited data, the authors currently initiate mechanical and pharmacological VTE prophylaxis within 2 h of incision and continue pharmacological VTE prophylaxis for the duration of the hospitalization after a hepatectomy. However, given the significant variation found in prophylaxis patterns amongst liver surgeons in this survey, we sought to identify factors that might influence provider decisions around VTE administration. We found that significant practice variation exists that is independent of post-graduate training and several other demographical variables. Self-reported higher volume HPB surgeons described the risk of VTE as lower, while stating that they prescribe pharmacological VTE prophylaxis for a longer duration than lower volume HPB surgeons. In addition, surgeons in community practice were more likely to believe that pharmacological VTE prophylaxis increased the risk of bleeding after a hepatectomy. Interestingly, surgeons from the United States more frequently used UFH for pharmacological VTE prophylaxis and were less likely to continue therapy post-discharge.

Our study had several limitations which should be considered. First, the survey assessed stated preferences for VTE prophylaxis among liver surgeons as opposed to their actual practice patterns. There may be differences between a surgeon’s stated and actual VTE prophylaxis pattern. Second, because we do not know the characteristics of the non-respondents, we cannot verify that the findings are representative of all surgeons performing hepatectomies. We specifically targeted surgeons who had publically available email addresses, so our results may not be representative of liver surgeons ‘at-large.’ However, the demographics of respondents reflected a wide range of training backgrounds and 19% of respondents were from outside of the United States.

In conclusion, there is considerable practice variation regarding VTE prophylaxis among liver surgeons. The vast majority of surgeons agree that VTE events after a hepatectomy are not uncommon and routinely employ VTE prophylaxis. However, the methods, timing and purported contraindications to VTE prophylaxis differ significantly among liver surgeons and are not necessarily supported by the literature. Different VTE prophylaxis patterns appear independent of post-graduate training and most demographic variables, but may be related to reported volume of HPB surgery, practice setting and location. Our data highlight the lack of consensus on the method and timing of VTE prophylaxis after liver operations among practicing surgeons.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article at the publisher's web-site:

Survey questions.

References

- Collins R, Scrimgeour A, Yusuf S, Peto R. Reduction in fatal pulmonary embolism and venous thrombosis by perioperative administration of subcutaneous heparin. Overview of results of randomized trials in general, orthopedic, and urologic surgery. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:1162–1173. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198805053181805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mismetti P, Laporte S, Darmon JY, Buchmuller A, Decousus H. Meta-analysis of low molecular weight heparin in the prevention of venous thromboembolism in general surgery. Br J Surg. 2001;88:913–930. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.01800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, Karanicolas PJ, Arcelus JI, Heit JA, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2 Suppl):e227S–e277S. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyman GH, Khorana AA, Kuderer NM, Lee AY, Arcelus JI, Balaban EP, et al. Venous thromboembolism prophylaxis and treatment in patients with cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology clinical practice guideline update. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:2189–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.49.1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caprini JA, Arcelus JI, Hasty JH, Tamhane AC, Fabrega F. Clinical assessment of venous thromboembolic risk in surgical patients. Semin Thromb Hemost. 1991;17(Suppl 3):304–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ejaz A, Spolverato G, Kim Y, Lucas DL, Lau B, Weiss M, et al. Defining incidence and risk factors of venous thromboemolism after hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2432-x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Martino RR, Goodney PP, Spangler EL, Wallaert JB, Corriere MA, Rzucidlo EM, et al. Variation in thromboembolic complications among patients undergoing commonly performed cancer operations. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2011.10.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton JS, Riha GM, Differding JA, Underwood SJ, Curren JL, Sheppard BC, et al. Coagulopathy after a liver resection: is it over diagnosed and over treated? HPB. 2013 doi: 10.1111/hpb.12051. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan H, Weiss MJ, Soff GA, Stempel M, Dematteo RP, Allen PJ, et al. Pharmacologic prophylaxis, postoperative INR, and risk of venous thromboembolism after hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013;18:295–302. doi: 10.1007/s11605-013-2383-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng CW, Katz MH, Fleming JB, Pisters PW, Lee JE, Abdalla EK, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism outweighs post-hepatectomy bleeding complications: analysis of 5651 National Surgical Quality Improvement Program patients. HPB. 2012;14:506–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1477-2574.2012.00479.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tripodi A, Mannucci PM. The coagulopathy of chronic liver disease. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:147–156. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman T, Porte RJ. Rebalanced hemostasis in patients with liver disease: evidence and clinical consequences. Blood. 2010;116:878–885. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-261891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kucirka LM, Namuyinga R, Hanrahan C, Montgomery RA, Segev DL. Formal policies and special informed consent are associated with higher provider utilization of CDC high-risk donor organs. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:629–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2008.02523.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan H, Bridges JF, Schulick RD, Cameron AM, Hirose K, Edil BH, et al. Understanding surgical decision making in early hepatocellular carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:619–625. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris-Stiff G, White A, Gomez D, Toogood G, Lodge JP, Prasad KR. Thrombotic complications following liver resection for colorectal metastases are preventable. HPB. 2008;10:311–314. doi: 10.1080/13651820802074431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddy SK, Turley RS, Barbas AS, Steel JL, Tsung A, Marsh JW, et al. Post-operative pharmacologic thromboprophylaxis after major hepatectomy: does peripheral venous thromboembolism prevention outweigh bleeding risks? J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:1602–1610. doi: 10.1007/s11605-011-1591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng CW, Curley SA, Vauthey JN, Aloia TA. Distinct predictors of pre- versus post-discharge venous thromboembolism after hepatectomy: analysis of 7621 NSQIP patients. HPB. 2013;15:773–780. doi: 10.1111/hpb.12130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turley RS, Reddy SK, Shortell CK, Clary BM, Scarborough JE. Venous thromboembolism after hepatic resection: analysis of 5,706 patients. J Gastrointest Surg. 2012;16:1705–1714. doi: 10.1007/s11605-012-1939-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, et al. GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:924–926. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Vist GE, Liberati A, et al. Going from evidence to recommendations. BMJ. 2008;336:1049–1051. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39493.646875.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farge D, Debourdeau P, Beckers M, Baglin C, Bauersachs RM, Brenner B, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment and prophylaxis of venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:56–70. doi: 10.1111/jth.12070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Efficacy and safety of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for prevention of deep vein thrombosis in elective cancer surgery: a double-blind randomized multicentre trial with venographic assessment. ENOXACAN Study Group. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1099–1103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baykal C, Al A, Demirtas E, Ayhan A. Comparison of enoxaparin and standard heparin in gynaecologic oncologic surgery: a randomised prospective double-blind clinical study. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol. 2001;22:127–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod RS, Geerts WH, Sniderman KW, Greenwood C, Gregoire RC, Taylor BM, et al. Subcutaneous heparin versus low-molecular-weight heparin as thromboprophylaxis in patients undergoing colorectal surgery: results of the canadian colorectal DVT prophylaxis trial: a randomized, double-blind trial. Ann Surg. 2001;233:438–444. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200103000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akl EA, Labedi N, Terrenato I, Barba M, Sperati F, Sempos EV, et al. Low molecular weight heparin versus unfractionated heparin for perioperative thromboprophylaxis in patients with cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;(11) doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009447. CD009447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Survey questions.