Abstract

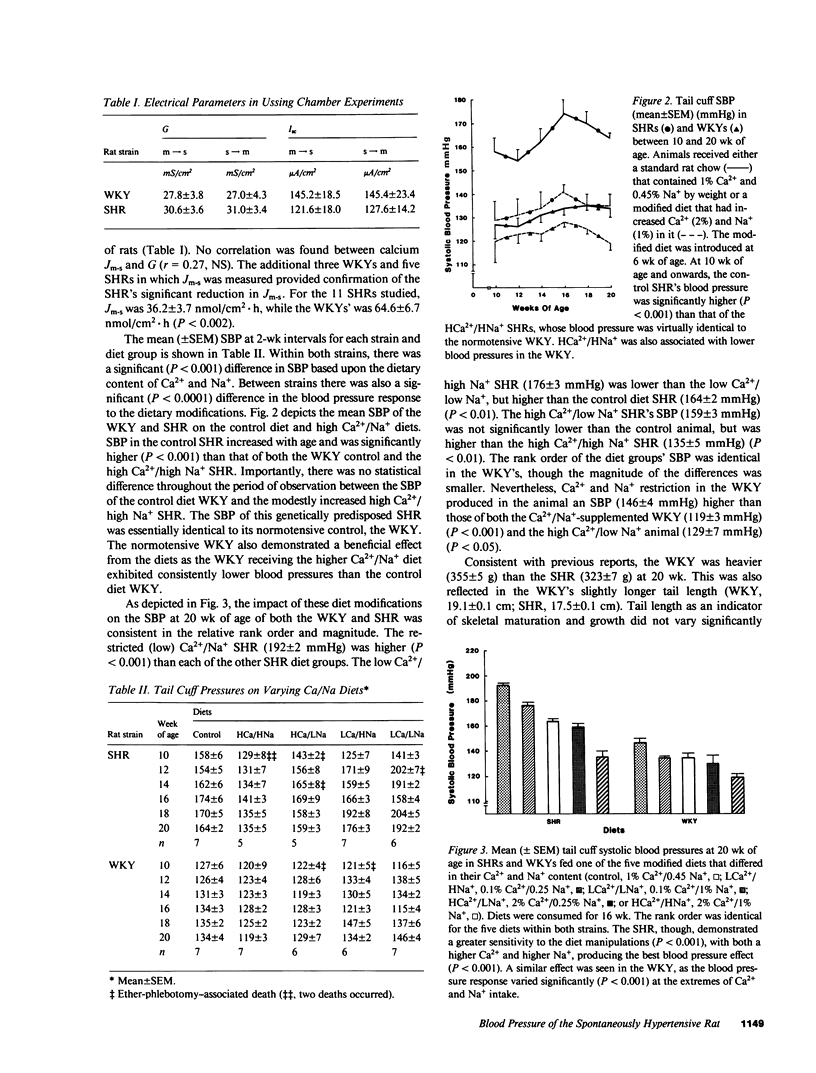

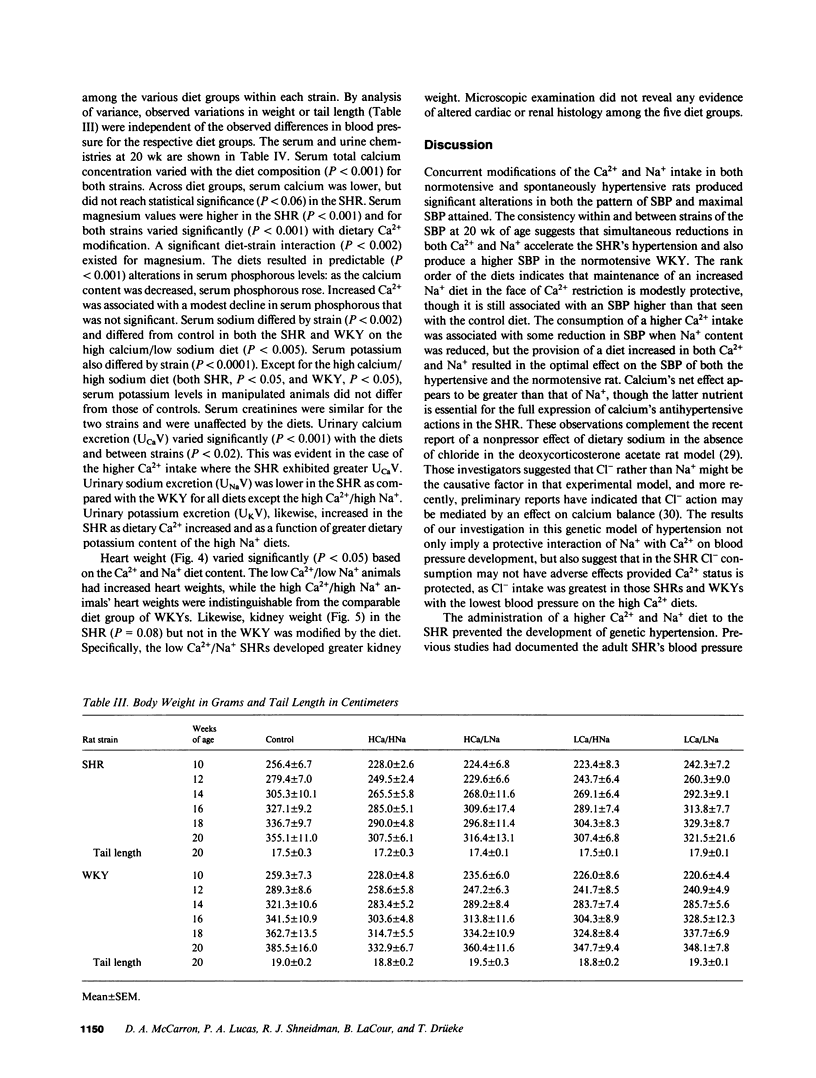

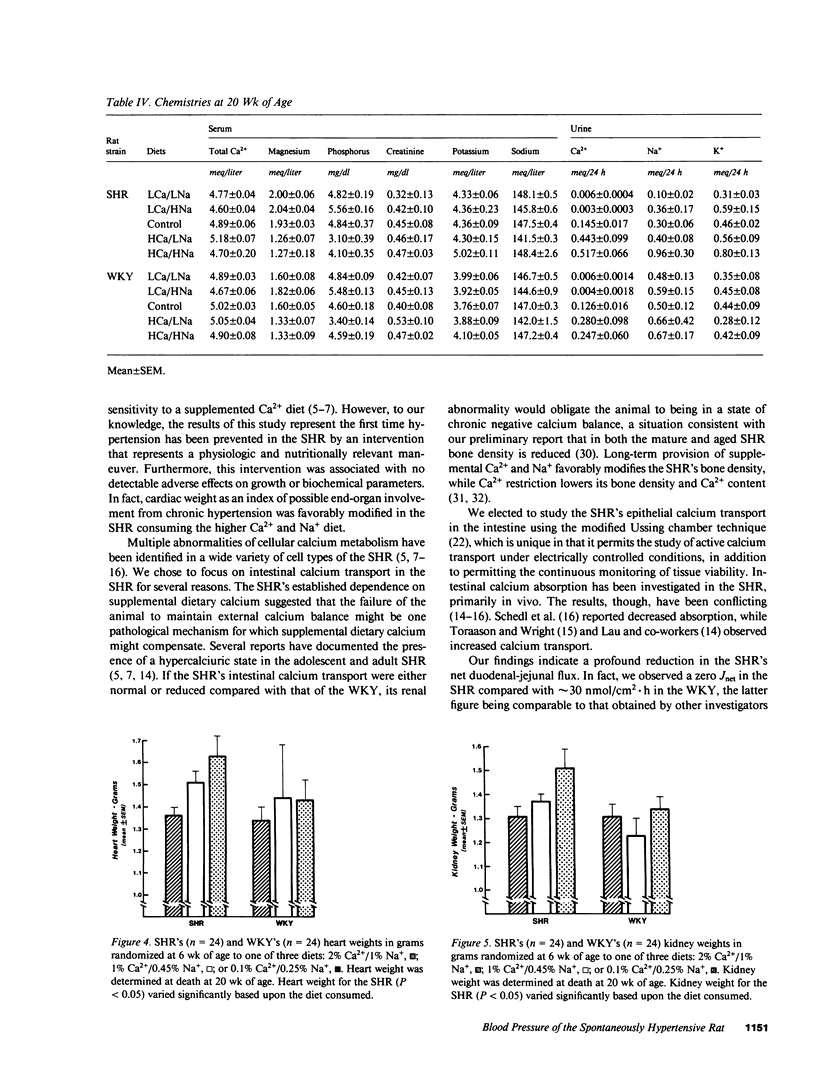

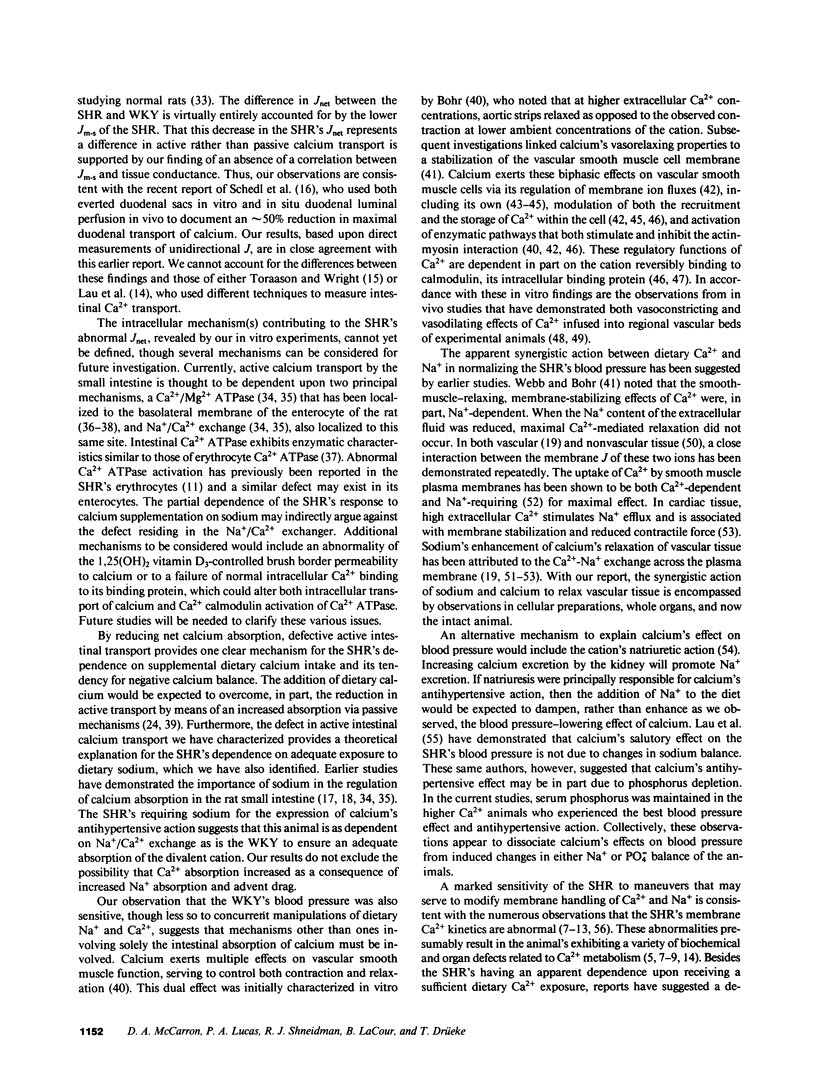

The blood pressure of the spontaneously hypertensive rat (SHR) is influenced by the Ca2+ content of its diet. As the SHR's greater dependence on dietary calcium may reflect a defect in intestinal calcium absorption, we measured in vitro unidirectional Ca2+ flux (J) in the duodenum-jejunum (four segments each) of the SHR (n = 6) and the normotensive Wistar-Kyoto rat (WKY; n = 6) by a modified Ussing apparatus. Because of the known and postulated interactions between Ca2+ and Na+ in both intestinal and vascular tissue, we assessed in vivo the influence of a concurrent manipulation of Na+ intake (three levels: 0.25%, 0.45%, and 1.0%) on the blood pressure development of SHRs (n = 35) and WKYs (n = 35), between 6 and 20 wk of age, exposed to three levels of dietary calcium (0.1, 1.0, and 2%). Net calcium flux (Jnet) (mean +/- SEM) was significantly (P less than 0.01) lower in the SHR (-2.8 +/- 6.3 nmol/cm2 X h) than in the WKY (34.6 +/- 8.8 nmol/cm2 X h). The SHR's decreased Jnet resulted from a significantly (P less than 0.03) lower mucosa-to-serosa flux (Jm-s) in the SHR (41.0 +/- 5.6 nmol/cm2 X h) compared with the Jm-s of the WKY (70.1 +/- 9.1 nmol/cm2 X h). Serosa-to-mucosa flux for calcium did not differ between the SHR (43.8 +/- 6.6 nmol/cm2 X h) and the WKY (35.5 +/- 8.0 nmol/cm2 X h). The SHR's decreased (P less than 0.002) Jm-s was confirmed by additional measurements in SHRs and WKYs. Jm-s was 36.2 +/- 3.7 nmol/cm2 X h in the SHRs (n = 11) and 64.4 +/- 6.7 nmol/cm2 X h in the WKYs (n = 9). The provision of an increased dietary Ca2+ (2% by weight) and increased Na+ (1%) to the SHR prevented the emergence of hypertension (P less than 0.001) (mean +/- SEM systolic blood pressure at 20 wk of age; 135 +/- 5 mmHg for the 2% Ca2+, 1% Na+ SHR vs. 164 +/- 2 mmHg for the control diet SHR). Ca2+ (0.1%) and Na+ (0.25%) restriction accelerated the SHR's hypertension (192 +/- 2 mmHg) (P less than 0.001) and was associated with higher pressures in the WKY (146 +/- 4 mmHg in the restricted WKY vs. 134 +/- 4 mmHg in the control WKY). In a parallel group of 24 SHRs and 24 WKYs fed one of three diets (2% Ca2+/1% Na+; 1% Ca2+/0.45% Na+; or 0.1% Ca2+/0.25% Na+), the heart (P < 0.05) and kidney (P = 0.08) weight of the SHRs varied depending on the diet at 20 wk of age. Low Ca2+ and Na+ intake was associated with increased heart weight (1.6+/-0.9 g) compared with the normal diet for SHR (1.51+/-0.07 g). Increased Ca2+ and Na+ intake was associated with a significantly (P = 0.05) lower heart weight in the SHR (1.37+/-0.03 g) and in the WKY (1.35+/-0.06 g) compared with their normal diet controls. These findings show one mechanism for the SHR's depressor response to supplemental dietary Ca2+ and, in part, explain the sodium dependence of calcium's cardiovascular protective effect.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Ackley S., Barrett-Connor E., Suarez L. Dairy products, calcium, and blood pressure. Am J Clin Nutr. 1983 Sep;38(3):457–461. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/38.3.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoki K., Yamori Y., Ooshima A., Okamoto K. Effects of high or low sodium intake in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Jpn Circ J. 1972 Jun;36(6):539–545. doi: 10.1253/jcj.36.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayachi S. Increased dietary calcium lowers blood pressure in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. Metabolism. 1979 Dec;28(12):1234–1238. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(79)90136-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beierwaltes W. H., Arendshorst W. J., Klemmer P. J. Electrolyte and water balance in young spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1982 Nov-Dec;4(6):908–915. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.4.6.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belizan J. M., Villar J., Pineda O., Gonzalez A. E., Sainz E., Garrera G., Sibrian R. Reduction of blood pressure with calcium supplementation in young adults. JAMA. 1983 Mar 4;249(9):1161–1165. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla R. C., Webb R. C., Singh D., Ashley T., Brock T. Calcium fluxes, calcium binding, and adenosine cyclic 3',5'-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase activity in the aorta of spontaneously hypertensive and Kyoto Wistar normotensive rats. Mol Pharmacol. 1978 May;14(3):468–477. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birge S. J., Switzer S. C., Leonard D. R. Influence of sodium and parathyroid hormone on calcium release from intestinal mucosal cells. J Clin Invest. 1974 Sep;54(3):702–709. doi: 10.1172/JCI107808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaustein M. P. Sodium ions, calcium ions, blood pressure regulation, and hypertension: a reassessment and a hypothesis. Am J Physiol. 1977 May;232(5):C165–C173. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1977.232.5.C165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr D. F. Vascular Smooth Muscle: Dual Effect of Calcium. Science. 1963 Feb 15;139(3555):597–599. doi: 10.1126/science.139.3555.597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman R. A. Control of cardiac contractility at the cellular level. Am J Physiol. 1983 Oct;245(4):H535–H552. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1983.245.4.H535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert R., Ewald D. Residual calcium ions depress activation of calcium-dependent current. Science. 1982 May 14;216(4547):730–733. doi: 10.1126/science.6281880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghijsen W. E., De Jong M. D., Van Os C. H. ATP-dependent calcium transport and its correlation with Ca2+ -ATPase activity in basolateral plasma membranes of rat duodenum. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1982 Jul 28;689(2):327–336. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(82)90266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghijsen W. E., van Os C. H. Ca-stimulated ATPase in brush border and basolateral membranes of rat duodenum with high affinity sites for Ca ions. Nature. 1979 Jun 28;279(5716):802–803. doi: 10.1038/279802a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover A. K., Kwan C. Y., Daniel E. E. Ca2+ dependence of calcium uptake by rat myometrium plasma membrane-enriched fraction. Am J Physiol. 1982 May;242(5):C278–C282. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1982.242.5.C278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover A. K., Kwan C. Y., Rangachari P. K., Daniel E. E. Na-Ca exchange in a smooth muscle plasma membrane-enriched fraction. Am J Physiol. 1983 Mar;244(3):C158–C165. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1983.244.3.C158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz L., McGuffee L. J., Smith P. M., Little S. A. Specific inhibition of calcium channels by calcium ions in smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1982 Feb;220(2):382–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ireland P., Fordtran J. S. Effect of dietary calcium and age on jejunal calcium absorption in humans studied by intestinal perfusion. J Clin Invest. 1973 Nov;52(11):2672–2681. doi: 10.1172/JCI107461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koller M., Binswanger U. Calcium transport in the ileum of uremic rats. Am J Physiol. 1982 Feb;242(2):G128–G134. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1982.242.2.G128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuriyama H., Ito Y., Suzuki H., Kitamura K., Itoh T. Factors modifying contraction-relaxation cycle in vascular smooth muscles. Am J Physiol. 1982 Nov;243(5):H641–H662. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1982.243.5.H641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz T. W., Morris R. C., Jr Dietary chloride as a determinant of "sodium-dependent" hypertension. Science. 1983 Dec 9;222(4628):1139–1141. doi: 10.1126/science.6648527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurtz T. W., Morris R. C., Jr Dietary chloride as a determinant of disordered calcium metabolism in salt-dependent hypertension. Life Sci. 1985 Mar 11;36(10):921–929. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90387-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwan C. Y., Daniel E. E. Biochemical abnormalities of venous plasma membrane fraction isolated from spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 1981 Nov 5;75(4):321–324. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(81)90561-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K., Chen S., Eby B. Evidence for the role of PO4 deficiency in antihypertensive action of a high-Ca diet. Am J Physiol. 1984 Mar;246(3 Pt 2):H324–H331. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1984.246.3.H324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau K., Zikos D., Spirnak J., Eby B. Evidence for an intestinal mechanism in hypercalciuria of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am J Physiol. 1984 Nov;247(5 Pt 1):E625–E633. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1984.247.5.E625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louis W. J., Tabei R., Spector S. Effects of sodium intake on inherited hypertension in the rat. Lancet. 1971 Dec 11;2(7737):1283–1286. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(71)90603-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin D. L., DeLuca H. F. Influence of sodium on calcium transport by the rat small intestine. Am J Physiol. 1969 Jun;216(6):1351–1359. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1969.216.6.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron D. A. Is calcium more important than sodium in the pathogenesis of essential hypertension? Hypertension. 1985 Jul-Aug;7(4):607–627. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.7.4.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron D. A., Morris C. D., Cole C. Dietary calcium in human hypertension. Science. 1982 Jul 16;217(4556):267–269. doi: 10.1126/science.7089566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarron D. A., Morris C. D., Henry H. J., Stanton J. L. Blood pressure and nutrient intake in the United States. Science. 1984 Jun 29;224(4656):1392–1398. doi: 10.1126/science.6729459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore L., Hurwitz L., Davenport G. R., Landon E. J. Energy-dependent calcium uptake activity of microsomes from the aorta of normal and hypertensive rats. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1975 Dec 16;413(3):432–443. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(75)90126-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murer H., Hildmann B. Transcellular transport of calcium and inorganic phosphate in the small intestinal epithelium. Am J Physiol. 1981 Jun;240(6):G409–G416. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1981.240.6.G409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellans H. N., Kimberg D. V. Cellular and paracellular calcium transport in rat ileum: effects of dietary calcium. Am J Physiol. 1978 Dec;235(6):E726–E737. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1978.235.6.E726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellans H. N., Popovitch J. E. Calmodulin-regulated, ATP-driven calcium transport by basolateral membranes of rat small intestine. J Biol Chem. 1981 Oct 10;256(19):9932–9936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlov S. N., Pokudin N. I., Postnov YuV Calmodulin-dependent Ca2+ transport in erythrocytes of spontaneously hypertensive rats. Pflugers Arch. 1983 Apr;397(1):54–56. doi: 10.1007/BF00585168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overbeck H. W. Attenuated arteriolar dilator responses to calcium in genetically hypertensive rats. Hypertension. 1984 Sep-Oct;6(5):647–653. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.6.5.647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piascik M. T., Babich M., Rush M. E. Calmodulin stimulation and calcium regulation of smooth muscle adenylate cyclase activity. J Biol Chem. 1983 Sep 25;258(18):10913–10918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen H. Cellular calcium metabolism. Ann Intern Med. 1983 May;98(5 Pt 2):809–816. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuter J. Some aspects of the growth of rats. Growth. 1976 Dec;40(4):379–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCHULTZ S. G., ZALUSKY R. ION TRANSPORT IN ISOLATED RABBIT ILEUM. I. SHORT-CIRCUIT CURRENT AND NA FLUXES. J Gen Physiol. 1964 Jan;47:567–584. doi: 10.1085/jgp.47.3.567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SCOTT J. B., FROHLICH E. D., HARDIN R. A., HADDY F. J. Na, K, Ca, and Mg ion action on coronary vascular resistance in the dog heart. Am J Physiol. 1961 Dec;201:1095–1100. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1961.201.6.1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schedl H. P., Miller D. L., Pape J. M., Horst R. L., Wilson H. D. Calcium and sodium transport and vitamin D metabolism in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Clin Invest. 1984 Apr;73(4):980–986. doi: 10.1172/JCI111323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitt F. W., Clayton D. G., Crawford M. D., Morris J. N. Clinical and biochemical indicators of cardiovascular disease among men living in hard and soft water areas. Lancet. 1973 Jan 20;1(7795):122–126. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(73)90195-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suki W. N. Calcium transport in the nephron. Am J Physiol. 1979 Jul;237(1):F1–F6. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1979.237.1.F1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tai Y. H., Decker R. A. Mechanisms of electrolyte transport in rat ileum. Am J Physiol. 1980 Mar;238(3):G208–G212. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1980.238.3.G208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannen R. L. Effects of potassium on blood pressure control. Ann Intern Med. 1983 May;98(5 Pt 2):773–780. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor A., Windhager E. E. Possible role of cytosolic calcium and Na-Ca exchange in regulation of transepithelial sodium transport. Am J Physiol. 1979 Jun;236(6):F505–F512. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1979.236.6.F505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobian L. Human essential hypertension: implications of animal studies. Ann Intern Med. 1983 May;98(5 Pt 2):729–734. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-98-5-729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toraason M. A., Wright G. L. Transport of calcium by duodenum of spontaneously hypertensive rat. Am J Physiol. 1981 Oct;241(4):G344–G347. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1981.241.4.G344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trippodo N. C., Frohlich E. D. Similarities of genetic (spontaneous) hypertension. Man and rat. Circ Res. 1981 Mar;48(3):309–319. doi: 10.1161/01.res.48.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Breemen C., Aaronson P., Loutzenhiser R. Sodium-calcium interactions in mammalian smooth muscle. Pharmacol Rev. 1978 Jun;30(2):167–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walling M. W., Kimberg D. V. Active secretion of calcium by adult rat ileum and jejunum in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1973 Aug;225(2):415–422. doi: 10.1152/ajplegacy.1973.225.2.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walling M. W., Kimberg D. V. Effects of 1alpha,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 and Solanum glaucophyllum on intestinal calcium and phosphate transport and on plasma Ca, Mg and P levels in the rat. Endocrinology. 1975 Dec;97(6):1567–1576. doi: 10.1210/endo-97-6-1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman R. H. Intestinal absorption of calcium and phosphorus. Fed Proc. 1981 Jan;40(1):68–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb R. C., Bohr D. F. Mechanism of membrane stabilization by calcium in vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol. 1978 Nov;235(5):C227–C232. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1978.235.5.C227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb R. C., Bohr D. F. Recent advances in the pathogenesis of hypertension: consideration of structural, functional, and metabolic vascular abnormalities resulting in elevated arterial resistance. Am Heart J. 1981 Aug;102(2):251–264. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8703(81)80016-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]