Abstract

Background. Perianal Crohn's disease (CD) can be challenging. Despite the high incidence of fistulizing CD, literature lacks clear guidelines. Several medical, surgical, and combined treatment modalities have been proposed, but evidences are scarce. Methods. We searched the literature to assess the facets of perianal CD, with particular focus on complex fistulae. Disease epidemiology, classification, diagnosis, activity scoring systems, and medical-surgical treatments were assessed. Results. Perianal fistulizing CD is common, frequently associated with upper gastrointestinal and colorectal CD. Complex fistulas often require repeated treatments. Continence is a major concern when dealing with repeated procedures. A prudent pathway is to resolve active sepsis and to limit damages, delaying a definitive treatment to the time when acute phase has been controlled. The improved diagnostic techniques allow better preoperative planning and are useful in monitoring the response to treatment. Besides newer devices, cell-based treatments are promising tools which have recently enriched the treatment portfolio. However, the need for proctectomy is still disturbingly high in CD patients with complex perianal fistulae. Conclusions. Perianal CD can impair quality of life and lead to need for proctectomy. A staged approach is reasonable. Treatment success can be improved by multimodal treatment and collaborative management by experienced gastroenterologists and surgeons.

1. Introduction

Approximately 40–60% of Crohn's disease (CD) patients have perianal involvement, and 30% have perianal fistula [1, 2]. The pathogenesis of perianal fistulae in CD is different from that of cryptoglandular ones. Usually, fistulae are believed to originate from either deep penetrating ulcers or anal gland infection/abscess [3]; however, other theories have been advocated in CD patients, involving microbiological, immunological, and genetic factors [4, 5]. These observations are in agreement with the higher rate of high, complex fistulae observed in CD patients with active rectal disease [6]. It is well known that CD is an independent risk factor for postoperative septic complications [7], suggesting the relevant contribution of intestinal microbiota to such a mechanism. Genetic and epigenetic factors play a pivotal role in CD, as the risk of developing CD and its related complications is higher in relatives of CD patients than in general population [5, 8]. Genetic susceptibility is suggested by the frequent association between perianal CD and colorectal as well as upper gastrointestinal disease involvement [9, 10] so that CD is a different entity from penetrating abdominal CD [9] and is also associated with worse prognosis in the long term [11]. Also, as active, persisting disease leads to fibrosis in CD [5], a hypoxia-mediated mechanism could also play a role [12]. Epidemiology of perianal CD should be considered in the light of the presumed incidence and prevalence of the disease per country. In Italy, the estimated incidence and prevalence of CD are reported to be as high as 5/100 000 inhabitants/year and 59.63/100 000 inhabitants, respectively [13]. In other words, a prevalence of nearly 11 000 patients with CD perianal fistulae can be predicted in Italy. Also, it has been reported that in 10% of patients perianal fistulae can be the first manifestation of CD [14]. This means that approximately 300 patients per year will present with perianal fistulae before receiving diagnosis of CD in Italy. These data give an insight of the burden of disease and highlight the importance of knowing how to manage such patients in the acute settings to avoid subsequent problems. Repeated maneuvers and too aggressive approaches justify the rate of incontinence still observed with conventional, cutting techniques in these patients, even reaching 50% for intersphincteric fistulae [15]. It should be noted that faecal diversion and proctectomy still play a relevant role in perianal CD [10, 16–19], further suggesting that the ideal management of such patients is yet to be achieved.

We present the most recent advances of surgical treatment of perianal CD in the light of the new discoveries in medical treatment, moving from lay-open to cell-based therapy, as well as imaging techniques.

2. Classification and Preoperative Assessment

The Montreal revision of Vienna classification identified perianal disease as an additional category (identified as “p” added to CD behavior) to be considered in association with the three main patterns of disease (penetrating; inflammatory; nonpenetrating noninflammatory) [20, 21]: this confirms that perianal CD is distinct entity from abdominal fistulizing CD [9, 11] and can occur in association with and independently of CD baseline behavior.

Sir Parks in 1976 classified perianal fistulae as intersphincteric, transsphincteric, suprasphincteric, extrasphincteric, and superficial, according to their relations with the external sphincter [22]. Several classifications were subsequently proposed for perianal CD, among which the Cardiff classification is one of the most known. However, it is considered difficult to apply in routine practice and of limited interest in terms of patient management [23]. The technical review published in 2003 by the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) proposed a simpler classification, widely adopted, identifying fistulae as either “simple” (low, with a single external opening) or “complex” (high, may have ≥1 external opening, associated with perianal abscess, rectovaginal fistula, anorectal stenosis, or active rectal disease) [1]. However, when planning treatment, each patient needs to be evaluated in detail, in order to avoid inappropriate treatment or overtreatment (i.e., a low, anovulvar fistula amenable with fistulotomy is classified as “complex”), suggesting that also such classification has grey areas.

Concerning the assessment of perianal disease, the most widespread tool is the perianal disease activity index (PDAI) [24], a clinical score assigning 0 (none) to 5 (highest) points to each of the following: fistula discharge, pain, restriction of daily activity, restriction of sexual activity, type of perianal disease, and degree of induration.

Physical examination must be implemented with endoscopy and at least one among examination under anesthesia (EUA), endoanal ultrasonography (EUS), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [1, 25, 26]. The effectiveness of EUS in pediatric patients has recently been reported, and this is relevant when considering the high rate of patients being observed with inflammatory bowel disease in the developmental age [27–29]. Concerning EUS, this technique has now been implemented with 3D image reconstruction, allowing better identification of the relationship between the fistula and the sphincter complex. In a series of 85 patients, Reginelli et al. showed that 3D-EUS provides accurate anatomical information and suggested that minor defects can be recognized, not detectable with conventional EUS [30]. In addition, the technique can be made more accurate by instillation of hydrogen peroxide. West et al. [31] compared the efficacy of hydrogen peroxide enhanced 3D-EUS with endoanal MRI in a prospective cohort of 21 patients with perianal fistula and reported an agreement as high as 80% in identifying the primary track for 3D-EUS and surgery, 90% for both MRI and surgery, and 3D-EUS and MRI. 3D-EUS was as accurate as MRI, in identifying the internal opening (86% both 3D-EUS and surgery, and MRI and surgery, 90% 3D-EUS and MRI) [31]. These findings support the reliability of both endoanal 3D-EUS and MRI in preoperative evaluation of fistula-in-ano. However, care must be paid not to overlook distant abscess, better visualized with conventional MRI. Furthermore, it is important to avoid errors with 3D-EUS originating from stitches or setons, which can simulate abscesses after enhancement with hydrogen peroxide [32].

Imaging techniques have also been reported to be useful in guiding the patient management and to assess response to treatment [27, 33, 34]. A meta-analysis [35] comparing MRI and EUS for the evaluation of perianal fistulae showed a slight superiority of the former; however comparable results can be expected in experienced hands, and performing a combination of two modalities among EUA, EUS, and MRI may reach 100% accuracy.

3. Treatment

3.1. Acute Presentation: Control of Sepsis

Up to 60% of patients with perianal CD shall present with an abscess requiring drainage [36, 37]. Literature lacks good quality studies on antibiotic treatment alone for perianal abscess and fistulae in CD, but most agree that a clinical response is observed after 6 to 8 weeks and mainly consists of reduced discharge, while fistula closure is uncommon and symptom recurrences are highly probable [38, 39]. As now, antibiotics (ciprofloxacin or metronidazole [39, 40]) can be considered first-line treatment, but surgery should be considered if symptoms worsen or are unacceptable and if a response is not observed within 6–8 weeks. Thia et al. [40] randomized 25 patients with perianal CD into three treatment arms: ciprofloxacin (10), metronidazole (7), and placebo (8). At 10-week follow-up, remission occurred in 30%, 0, and 12.5% of patients receiving ciprofloxacin, metronidazole, and placebo (P = 0.41). Response occurred more frequently in patients treated with ciprofloxacin but the differences were not significant. Once indication to surgery is made, aims of treatment of the acute phase are to drain adequately the abscess and to avoid sphincter lesions. Michelassi et al. [36] showed that incision and drainage achieved healing in 2/3 of 34 patients with perianal CD, while 1/3 subsequently presented with fistula. Others have reported that almost half of patients with perianal CD abscess will subsequently need treatment for associated fistulae [41]. Pritchard et al. [41] treated 38 consecutive CD patients presenting with perirectal abscess, of whom 30 had simple and eight horseshoe abscesses. Fifty-three percent of patients underwent incision and drainage, whereas 47% had drain catheters placed. After abscess resolution, abscesses recurred in 45% and 56% of the patients who underwent catheter drainage and incision and drainage, respectively [41]. It is common practice in some surgical teams to place a mushroom (or Malecot) catheter to drain large cavities, but it is mostly done following empirical principles [14]. Should a low, intersphincteric fistula be found at surgery, spontaneous healing is observed in approximately 35% of patients, while fistulotomy achieves complete healing in 60–100% of patients [36, 42, 43]; it is prudent and recommended to place loose-setons along fistulae for which the relations with anal sphincters are unclear or in those extending upward. The surgeons should carefully check that external opening is wide enough to ensure adequate draining; primary suturing of potential residual cavities is proscribed.

Once sepsis is controlled, fistula assessment is recommended by means of MRI or EUS, should it have not been performed before surgery.

3.2. Maintenance/Preparation

Once sepsis is controlled, it is important to maintain the remission, keeping the site drained. The commonest strategy is represented by atraumatic, loose-seton placement (silastic or ethibond), aimed at preventing abscess formation and to avoid sphincter section. This is a safe procedure to limit damages, and short-time healing is achieved in 48–100% of patients [44]. No accepted data are available concerning the ideal time to remove the seton, and this is performed on empirical basis, reported to range between 3 and 58 months by some authors [33]. If an early removal may intuitively lead to abscess formation, a prolonged stay in situ can result in fibrosis of the fistulous track, leading to persistent incapability to heal after seton removal. Furthermore, disappointing results can be expected in the long term, with symptomatic recurrences occurring in over 80% of patients after removal [33]. However, placing a seton loosely is a safe and useful strategy before attempting a definitive approach, without continence disturbances.

In the eventuality of active disease not amenable with conservative treatment, a fecal diversion may be needed and usually restores patient well-being rapidly [45]. In a study of 79 patients with severe, debilitating CD undergoing faecal diversion with loop-ileostomy, 91% had clinical improvement and allowed delaying definitive surgery at a later stage, under more appropriate circumstances [45]. On the other hand, one should consider that diverted CD patients are unlikely to undergo stoma reversal, with more than 80% of patients receiving an indefinite diversion [17]. This also raises safety concerns, due to the presence of active disease with consequent higher risk of malignancies [46]. Aiming to identify predictors of definitive stoma, Galandiuk et al. [47] reviewed the clinical data of 356 consecutive patients with CD, of whom 86 were with perianal CD. Active colonic disease, anorectal stenosis, and multiple perianal procedures were associated with the need of permanent diversion [47].

3.3. Definitive Treatment

Low/simple fistulae are well treated with tissue separating techniques, as fistulotomy achieves almost 100% of healing with minimal risk of continence disturbances [36, 48, 49]. Tissue separating techniques can be carried out at the time of seton removal in selected patients for complex fistulas, but the risk of incontinence is a major issue in such an eventuality [6, 50].

More conservative treatments have consequently been proposed. The efficacy of infliximab (IFX, a murine/human chimeric monoclonal antibody directed toward TNF-α) in inducing complete healing in CD perianal fistulae has been reported to be as high as 46% after induction therapy (3 infusions at weeks 0, 2, and 6) [51], as well as the utility of establishing a maintenance regimen. In fact, in the ACCENT II trial, 36% of patients receiving scheduled maintenance IFX effusions had complete healing confirmed after 54 weeks, compared with 19% in the placebo group [52]. In order to increase the rate of success Topstad et al. [53] proposed a combined approach, consisting of surgery aimed at draining sepsis with seton placement, followed by IFX effusions. The good results obtained were confirmed by others [54, 55], showing higher rate of response and lower recurrences with EUA plus IFX than with IFX alone [54], and a decrease of PDAI after EUA plus IFX [55]. A study comparing three groups treated with IFX, surgery, or combined treatment showed that the former had shorter time to heal and longer time to recur [56]. However, IFX administration can have significant side effects and is contraindicated in patients with abdominal fibrostenosing CD [1, 57]. Aiming to reduce systemic effects and to treat patients with contraindications to intravenous administration, Poggioli et al. proposed injection of IFX at the fistula site [58] and showed complete healing in 10 out of 15 patients treated (67%). The same promising results were confirmed using another biological drug, adalimumab (ADA), a fully humanized anti-TNF-α antibody [59]. The drawback of this approach is the local fibrosis caused by the drugs, but it seemed less marked with ADA [59].

Advancement flaps of rectal mucosa represent another surgical option for the management of complex perianal and rectovaginal fistulae (RVF). The advantages of flap procedures consist of both avoidance of external wounds, the healing of which could be impaired by active sepsis and contribute to perineal scarring, and reduced manipulation of the sphincters, with lower risks of incontinence. Flaps are contraindicated with active proctitis. The procedure is easier in patients with perineal descent and internal intussusception. However, midterm success rates do not exceed 57% [60, 61]. CD is an independent predictor of failure [60, 61], with a hazard ratio of 2.92 versus patients with cryptoglandular fistulae [60]. RVF can be approached for flap procedures either transanally or tranvaginally. A systematic review of 11 studies reporting on 224 flap procedures for RVF in CD patients showed that pooled primary closure (53% versus 61% transrectal versus transvaginal) and pooled overall closure (75% versus 81%, transrectal versus transvaginal) were similar with both approaches [62]. Very recently a new technique was proposed to enhance the outcomes of flap repair for complex CD fistulae, combining it with video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) [63]. Out of 11 patients in whom the treatment was completed, 9 had a complete response at 9-month follow-up (82%), with no continence disturbances.

Gingold et al. [64] performed the ligation of the intersphincteric fistula track (LIFT) procedure in 15 consecutive patients with complex fistulae, reporting healing of the LIFT site in 8 of 12 patients (67%) with 12-month follow-up. The authors suggested that lateral versus midline location (P = 0.02) and longer mean fistula length (P = 0.02) were predictors of 12-month LIFT site healing [64]. No patients experienced incontinence.

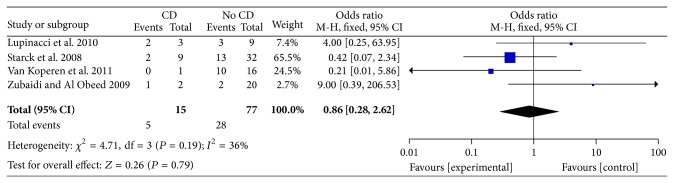

Less invasive strategies have been also attempted with fistula track fillers, namely, plugs and glues. A systematic review of 20 studies aimed at comparing the results of bioprosthetic anal fistula plug in patients with CD compared with non-CD patients has recently been published. The authors suggested that studies were too heterogeneous to attempt meta-analysis [65] but reported an overall pooled fistula closure of 55% (22/42 patients) and 54% (265/488 patients) in CD and non-CD, respectively. As the authors included both complex and simple fistulae, we tried to assess the failure rate by only evaluating data of patients with complex fistulae and from studies where the diagnoses were clearly reported. By including 4 studies [66–69], we found a rate of no response in 33% versus 36% in CD versus non-CD patients, but this slight difference was not statistically relevant and 36% heterogeneity (assessed with I 2) was observed (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Forest plot of the failure (event) of patients undergoing plug procedure with (CD) or without (no CD) diagnosis of Crohn's disease. Only papers in which CD could clearly be identified and only patients with complex fistulae were included. No differences were observed between Crohn's disease patients and controls (OR 0.86, 95%CI 0.28–2.62, P = 0.79) (Mantel-Haenszel fixed effect). Low heterogeneity is observed: I 2 = 36%.

Concerning treatment with glues, literature lacks good quality studies focused on CD patients. An open label, randomized, controlled trial from the Groupe d'Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif (GETAID) on CD patients comparing fibrin glue with observation only showed clinical remission in (13/34) 38% of glue group compared with 6/37 (16%) in controls at 8-week follow-up [70]. Twenty controls were also treated with fibrin glue, and 9 maintained remission after 16 weeks. Considering all 54 patients receiving fibrin glue, only 11 (20%) were in remission at last follow-up (median 37 months for fibrin glue ab initio and 17 months for the crossover group) [70]. In published series, treatment success ranges between 0 and 100% [70–73].

Caution must be paid when trying to interpret data on glues and plugs [65, 74]: many authors have conflict of interests; devices are very expensive; patients, procedures, and studies are heterogeneous; the follow-up is often too short; healing is assessed only clinically; no postoperative MRI scan is performed in any study, although some assess the patients with MRI preoperatively [70]. However, limited sphincter manipulation is needed, with theoretically no risk of incontinence so that the procedures can be harmlessly repeated.

Aiming to improve the rate of success of fibrin glue, modified glue formulations have been proposed. Garcia-Olmo et al. [75] randomized 49 patients (14 suffering from CD) with perianal fistulae to treatment with either adipose derived stem cells (ASCs) in fibrin glue or fibrin glue alone and reported an increase in healing rate from 18% with fibrin glue alone to 71% in patients receiving the glue added with ASCs [75]. This publication paves the way to the so-called cell-based treatment of perianal fistulae. ASCs are living adult stem cells of mesenchymal origin which are activated in an inflamed environment (e.g., fistulae). ASCs can simultaneously regulate multiple upstream pathways of inflammation. These cells are activated by IFN-γ released in inflamed areas and have the capability to suppress both the proliferation of activated lymphocytes and the production of inflammatory signals through the expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase [76, 77]. These effects ultimately lead to elimination of activated lymphocytes and proinflammatory cytokines, resulting in pain cessation and tissue repair. This perspective, if confirmed, is fascinating when dealing with CD patients with complex perianal fistulae, as the principle of ASCs relies on stimulating the host immune system to almost physiologically remove the source of inflammation, with no reported side effects and limited perineal scarring. A phase-III multicentric, randomized, controlled trial is currently recruiting CD patients with complex perianal fistulae unresponsive to conventional medical or surgical treatment, investigating the efficacy of allogenic ASCs as intralesional injection versus placebo, saline solution (ADMIRE-CD, registered as NCT01541579 at clinicaltrial.gov). This is a double-blind trial, and healing is going to be assessed both clinically and by means of MRI (with central blind assessment) up to 52 weeks after treatment. Final data collection date should be around January 2015. If the results of this study will confirm the enthusiastic findings of prior studies with ASCs as filling devices, it will add a useful tool to the armamentarium of surgeons and physicians dealing with complex perianal CD.

In refractory perianal disease with concomitant active proctitis unresponsive to medical/surgical treatment, a faecal diversion can be necessary. Since less than 20% of diverted CD patients will undergo stoma reversal, this should be considered a last resort [17, 18]. It has been also reported that 20% of patients receiving colectomy will require proctectomy within 5 years [19]. These observations justify the disturbingly high rate of proctectomy still observed, ranging between 10 and 18% [10, 49]. Recently, IFX proved to be effective in CD patients with failed ileorectal anastomosis candidates to proctectomy, preserving the rectum in 10/12 patients (83.3%) [78]. Proctectomy is still to be favored over indefinite diversion.

4. Conclusions

Despite perianal fistulae affecting a relevant rate of patients suffering from CD, literature lacks evidence-based pathways for the management of complex perianal fistulae in CD. This is commonly performed with empirical approaches. Also, unlike ulcerative colitis [29, 79] and colorectal surgery [80], little is known concerning treatment according to age, as this may be relevant when balancing advantages and potential side effects of medical compared with surgical treatment. Furthermore, the risk of cancerogenesis and a potential role of timely surgery in removing inflammation ultimately reducing the risk of cancer are less investigated in CD than in ulcerative colitis patients [46, 81]. When dealing with perianal CD, it is pivotal to assess the entire patient condition and to careful balance medical and surgical treatment. A staged approach, as reported in Figure 2, may be a prudent choice.

Figure 2.

A proposed algorithm to manage patients presenting with perianal Crohn's disease. In patient needing immediate drainage of abscess, emergency treatment is performed, aimed at controlling sepsis (1). Should associated fistulous tracks be identified, it is prudent to place loose-seton(s) as bridge-to-definitive treatments, aiming to maintain the drainage, avoiding abscess formation. Patients with very active disease may require temporary faecal diversion (2). Once sepsis is controlled and the patient is in good general health status, definitive treatment can be attempted, consisting of either tissue separating techniques (fistulotomy, fistulectomy) or more conservative and combined approach (3). An interval of 2-3 months seems acceptable. In patients with failure, procedures can be repeated, favoring approaches which do not increase significantly the risk of incontinence. Stoma or proctectomy may be required in refractory, frail patients. LIFT: ligation of the intersphincteric fistula track, VAAFT: video-assisted anal fistula treatment.

Abbreviations

- ADA:

Adalimumab

- AGA:

American Gastroenterological Association

- ASCs:

Adipose derived stem cells

- CD:

Crohn’s disease

- EUA:

Examination under anesthesia

- EUS:

Endoanal ultrasonography

- GETAID:

Groupe d’Etude Thérapeutique des Affections Inflammatoires du Tube Digestif

- IFX:

Infliximab

- LIFT:

Ligation of the intersphincteric fistula track

- MRI:

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PDAI:

Perianal disease activity index

- RVF:

Rectovaginal fistula

- VAAFT:

Video-assisted anal fistula treatment.

Disclosure

Dr. G Pellino presented this overview as a speech at the Joint Congress of Italian Societies of Surgery (Chirurgie, il Futuro, I Giovani Chirurghi), held in Naples, 4–6 June 2014.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

References

- 1.Sandborn W. J., Fazio V. W., Feagan B. G., Hanauer S. B. American Gastroenterological Association Clinical Practice Committee. AGA technical review on perianal Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:1508–1530. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schwartz D. A., Loftus E. V., Jr., Tremaine W. J., Panaccione R., Harmsen W. S., Zinsmeister A. R., Sandborn W. J. The natural history of fistulizing Crohn's disease in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Gastroenterology. 2002;122(4):875–880. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schwartz D. A., Pemberton J. H., Sandborn W. J. Diagnosis and treatment of perianal fistulas in Crohn disease. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2001;135(10):906–918. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-135-10-200111200-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tozer P. J., Whelan K., Phillips R. K. S., Hart A. L. Etiology of perianal Crohn's disease: role of genetic, microbiological, and immunological factors. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2009;15(10):1591–1598. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Latella G., Rogler G., Bamias G., et al. Results of the 4th scientific workshop of the ECCO (I): pathophysiology of intestinal fibrosis in IBD. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2014;8(10):1147–1165. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halme L., Sainio A. P. Factors related to frequency, type, and outcome of anal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1995;38(1):55–59. doi: 10.1007/BF02053858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pellino G., Sciaudone G., Candilio G., Campitiello F., Selvaggi F., Canonico S. Effects of a new pocket device for negative pressure wound therapy on surgical wounds of patients affected with Crohn's disease: a pilot trial. Surgical Innovation. 2014;21(2):204–212. doi: 10.1177/1553350613496906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pellino G., Sciaudone G., Patturelli M., et al. Relatives of Crohn's disease patients and breast cancer: an overlooked condition. International Journal of Surgery. 2014;12(supplement 1):S156–S158. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2014.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tang L. Y., Rawsthorne P., Bernstein C. N. Are perineal and luminal fistulas associated in Crohn's disease? A population-based study. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2006;4(9):1130–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wolff B. G., Culp C. E., Beart R. W., Jr., Ilstrup D. M., Roger M. S., Ready L. Anorectal Crohn's disease—a long-term perspective. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1985;28(10):709–711. doi: 10.1007/BF02560279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Biancone L., Zuzzi S., Ranieri M., Petruzziello C., Calabrese E., Onali S., Ascolani M., Zorzi F., Condino G., Iacobelli S., Pallone F. Fistulizing pattern in Crohn's disease and pancolitis in ulcerative colitis are independent risk factors for cancer: a single-center cohort study. Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2012;6(5):578–587. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pellino G. Immunosuppression may exert a hypoxia-mediated carcinogenetic effect in long-standing fistulizing Crohn's disease. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2014;26(5):575–576. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tursi A., Elisei W., Picchio M. Incidence and prevalence of inflammatory bowel diseases in gastroenterology primary care setting. European Journal of Internal Medicine. 2013;24(8):852–856. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nielsen O. H., Rogler G., Hahnloser D., Thomsen O. Ø. Diagnosis and management of fistulizing Crohn's disease. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology and Hepatology. 2009;6(2):92–106. doi: 10.1038/ncpgasthep1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keighley M. R., Allan R. N. Current status and influence of operation on perianal Crohn's disease. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 1986;1(2):104–107. doi: 10.1007/BF01648416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frizelle F. A., Santoro G. A., Pemberton J. H. The management of perianal Crohn's disease. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 1996;11(5):227–237. doi: 10.1007/s003840050052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yamamoto T., Allan R. N., Keighley M. R. B. Effect of fecal diversion alone on perianal Crohn's disease. World Journal of Surgery. 2000;24(10):1258–1263. doi: 10.1007/s002680010250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong M. K. H., Craig Lynch A., Bell S., Woods R. J., Keck J. O., Johnston M. J., Heriot A. G. Faecal diversion in the management of perianal Crohn's disease. Colorectal Disease. 2011;13(2):171–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cattan P., Bonhomme N., Panis Y., Lémann M., Coffin B., Bouhnik Y., Allez M., Sarfati E., Valleur P. Fate of the rectum in patients undergoing total colectomy for Crohn's disease. British Journal of Surgery. 2002;89(4):454–459. doi: 10.1046/j.0007-1323.2001.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gasche C., Scholmerich J., Brynskov J., D'Haens G., Hanauer S. B., Jan Irvine E., Jewell D. P., Rachmilewitz D., Sachar D. B., Sandborn W. J., Sutherland L. R. A simple classification of Crohn's disease: report of the working party for the world congresses of gastroenterology, Vienna 1998. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2000;6(1):8–15. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200002000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Satsangi J., Silverberg M. S., Vermeire S., Colombel J.-F. The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: Controversies, consensus, and implications. Gut. 2006;55(6):749–753. doi: 10.1136/gut.2005.082909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parks A. G., Gordon P. H., Hardcastle J. D. A classification of fistula in ano. British Journal of Surgery. 1976;63(1):1–12. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800630102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hughes L. E. Clinical classification of perianal Crohn's disease. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1992;35(10):928–932. doi: 10.1007/BF02253493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Irvine E. J. Usual therapy improves perianal Crohn's disease as measured by a new disease activity index. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 1995;20(1):27–32. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ardizzone S., Maconi G., Cassinotti A., Massari A., Porro G. B. Imaging of perianal Crohn's disease. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2007;39(10):970–978. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2007.07.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wise P. E., Schwartz D. A. The evaluation and treatment of Crohn perianal fistulae: EUA, EUS, MRI, and other imaging modalities. Gastroenterology Clinics of North America. 2012;41(2):379–391. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rosen M. J., Moulton D. E., Koyama T., Morgan W. M., III, Morrow S. E., Herline A. J., Muldoon R. L., Wise P. E., Polk D. B., Schwartz D. A. Endoscopic ultrasound to guide the combined medical and surgical management of pediatric perianal Crohn's disease. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2010;16(3):461–468. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Castro M., Papadatou B., Baldassare M., Balli F., Barabino A., Barbera C., Barca S., Barera G., Bascietto F., Canani R. B., Calacoci M., Campanozzi A., Castelluci G., Catassi C., Colombo M., Covoni M. R., Cucchiara S., D'Altilia M. R., de Angelis G. L., de Virgilis S., di Ciommo V., Fontana M., Guariso G., Knafelz D., Lambertini A., Licciardi S., Lionetti P., Liotta L., Lombardi G., Maestri L., Martelossi S., Mastella G., Oderda G., Perini R., Pesce F., Ravelli A., Roggero P., Romano C., Rotolo N., Rutigliano V., Scotta S., Sferlazzas C., Staiano A., Ventura A., Zaniboni M. G. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents in Italy: data from the pediatric national IBD register (1996–2003) Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2008;14(9):1246–1252. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pellino G., Sciaudone G., Miele E., Candilio G., De Fatico G. S., Riegler G., Staiano A., Canonico S., Selvaggi F. Functional outcomes and quality of life after restorative proctocolectomy in paediatric patients: a case-control study. Gastroenterology Research and Practice. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/340341.340341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Reginelli A., Mandato Y., Cavaliere C., Pizza N. L., Russo A., Cappabianca S., Brunese L., Rotondo A., Grassi R. Three-dimensional anal endosonography in depicting anal-canal anatomy. Radiologia Medica. 2012;117(5):759–771. doi: 10.1007/s11547-011-0768-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.West R. L., Zimmerman D. D. E., Dwarkasing S., Hussain S. M., Hop W. C. J., Schouten W. R., Kuipers E. J., Felt-Bersma R. J. F. Prospective comparison of hydrogen peroxide-enhanced three-dimensional endoanal ultrasonography and endoanal magnetic resonance imaging of perianal fistulas. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2003;46(10):1407–1415. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6758-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mandato Y., Reginelli A., Galasso R., Iacobellis F., Berritto D., Cappabianca S. Errors in the radiological evaluation of the alimentary tract: part I. Seminars in Ultrasound, CT and MRI. 2012;33(4):300–307. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Buchanan G. N., Owen H. A., Torkington J., Lunniss P. J., Nicholls R. J., Cohen C. R. G. Long-term outcome following loose-seton technique for external sphincter preservation in complex anal fistula. British Journal of Surgery. 2004;91(4):476–480. doi: 10.1002/bjs.4466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tozer P., Ng S. C., Siddiqui M. R., Plamondon S., Burling D., Gupta A., Swatton A., Tripoli S., Vaizey C. J., Kamm M. A., Phillips R., Hart A. Long-term MRI-guided combined anti-TNF-α and thiopurine therapy for crohn's perianal fistulas. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2012;18(10):1825–1834. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siddiqui M. R., Ashrafian H., Tozer P., et al. A diagnostic accuracy meta-analysis of endoanal ultrasound and MRI for perianal fistula assessment. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2012;55(5):576–585. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318249d26c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Michelassi F., Melis M., Rubin M., Hurst R. D. Surgical treatment of anorectal complications in Crohn's disease. Surgery. 2000;128(4):597–603. doi: 10.1067/msy.2000.108779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sangwan Y. P., Schoetz D. J., Jr., Murray J. J., Roberts P. L., Coller J. A. Perianal Crohn's disease: results of local surgical treatment. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1996;39(5):529–535. doi: 10.1007/BF02058706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brandt L. J., Bernstein L. H., Boley S. J., Frank M. S. Metronidazole therapy for perineal Crohn's disease: a follow-up study. Gastroenterology. 1982;83(2):383–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Solomon M. J., McLeod R. S., O'Connor B. I., Steinhart A. H., Greenberg G. R., Cohen Z. Combination ciprofloxacin and metronidazole in severe perianal Crohn's disease. Canadian Journal of Gastroenterology. 1993;7(7):571–573. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thia K. T., Mahadevan U., Feagan B. G., et al. Ciprofloxacin or metronidazole for the treatment of perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease: a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled pilot study. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2009;15(1):17–24. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pritchard T. J., Schoetz D. J., Jr., Roberts P. L., Murray J. J., Coller J. A., Veidenheimer M. C. Perirectal abscess in Crohn's disease: drainage and outcome. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1990;33(11):933–937. doi: 10.1007/BF02139102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Makowiec F., Jehle E. C., Becker H.-D., Starlinger M. Perianal abscess in Crohn's disease. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1997;40(4):443–450. doi: 10.1007/BF02258390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Allan A., Keighley M. R. Management of perianal Crohn's disease. World Journal of Surgery. 1988;12(2):198–202. doi: 10.1007/BF01658054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Whiteford M. H., Kilkenny J., III, Hyman N., Buie W. D., Cohen J., Orsay C., Dunn G., Perry W. B., Ellis C. N., Rakinic J., Gregorcyk S., Shellito P., Nelson R., Tjandra J. J., Newstead G. Practice parameters for the treatment of perianal abscess and fistula-in-ano (revised) Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2005;48(7):1337–1342. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0055-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zelas P., Jagelman D. G. Loop ileostomy in the management of Crohn's colitis in the debilitated patient. Annals of Surgery. 1980;191(2):164–168. doi: 10.1097/00000658-198002000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Egan L., D'Inca R., Jess T., Pellino G., Carbonnel F., Bokemeyer B., Harbord M., Nunes P., van der Woude J., Selvaggi F., Triantafillidis J. Non-colorectal intestinal tract carcinomas in inflammatory bowel disease: results of the 3rd ECCO Pathogenesis Scientific Workshop (II) Journal of Crohn's and Colitis. 2014;8(1):19–30. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2013.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galandiuk S., Kimberling J., Al-Mishlab T. G., Stromberg A. J., Adams D. B., Ricketts R. R., O'Leary J. P. Perianal Crohn disease: predictors of need for permanent diversion. Annals of Surgery. 2005;241(5):796–801. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000161030.25860.c1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morrison J. G., Gathright J. B., Jr., Ray J. E., Ferrari B. T., Hicks T. C., Timmcke A. E. Surgical management of anorectal fistulas in Crohn's disease. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1989;32(6):492–496. doi: 10.1007/BF02554504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Graham Williams J., Rothenberger D. A., Nemer F. D., Goldberg S. M. Fistula-in-ano in Crohn's disease—results of aggressive surgical treatment. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 1991;34(5):378–384. doi: 10.1007/BF02053687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Williams J. G., MacLeod C. A., Rothenberger D. A., Goldberg S. M. Seton treatment of high anal fistulae. British Journal of Surgery. 1991;78(10):1159–1161. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800781004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Present D. H., Rutgeerts P., Targan S., Hanauer S. B., Mayer L., van Hogezand R. A., Podolsky D. K., Sands B. E., Braakman T., Dewoody K. L., Schaible T. F., van Deventer S. J. H. Infliximab for the treatment of fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 1999;340(18):1398–1405. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199905063401804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sands B. E., Anderson F. H., Bernstein C. N., et al. Infliximab maintenance therapy for fistulizing Crohn’s disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;350:876–885. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Topstad D. R., Panaccione R., Heine J. A., Johnson D. R. E., MacLean A. R., Buie W. D. Combined seton placement, infliximab infusion, and maintenance immunosuppressives improve healing rate in fistulizing anorectal Crohn's disease: a single center experience. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2003;46(5):577–583. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-6611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Regueiro M., Mardini H. Treatment of perianal fistulizing Crohn's disease with infliximab alone or as an adjunct to exam under anesthesia with seton placement. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2003;9(2):98–103. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200303000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hyder S. A., Travis S. P. L., Jewell D. P., McC. Mortensen N. J., George B. D. Fistulating anal Crohn's disease: results of combined surgical and infliximab treatment. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2006;49(12):1837–1841. doi: 10.1007/s10350-006-0656-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sciaudone G., Di Stazio C., Limongelli P., Guadagni I., Pellino G., Riegler G., Coscione P., Selvaggi F. Treatment of complex perianal fistulas in Crohn disease: infliximab, surgery or combined approach. Canadian Journal of Surgery. 2010;53(5):299–304. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Orlando A., Armuzzi A., Papi C., Annese V., Ardizzone S., Biancone L., Bortoli A., Castiglione F., D'Incà R., Gionchetti P., Kohn A., Poggioli G., Rizzello F., Vecchi M., Cottone M. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) Clinical Practice Guidelines: the use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2011;43(1):1–20. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poggioli G., Laureti S., Pierangeli F., Rizzello F., Ugolini F., Gionchetti P., Campieri M. Local injection of infliximab for the treatment of perianal Crohn's disease. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2005;48(4):768–774. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-0832-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poggioli G., Laureti S., Pierangeli F., Bazzi P., Coscia M., Gentilini L., Gionchetti P., Rizzello F. Local injection of adalimumab for perianal Crohn's disease: better than infliximab? Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. 2010;16(10, article 1631) doi: 10.1002/ibd.21210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sonoda T., Hull T., Piedmonte M. R., Fazio V. W. Outcomes of primary repair of anorectal and rectovaginal fistulas using the endorectal advancement flap. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2002;45(12):1622–1628. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7249-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mizrahi N., Wexner S. D., Zmora O., Da Silva G., Efron J., Weiss E. G., Vernava A. M., III, Nogueras J. J. Endorectal advancement flap: are there predictors of failure? Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2002;45(12):1616–1621. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7248-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ruffolo C., Scarpa M., Bassi N., Angriman I. A systematic review on advancement flaps for rectovaginal fistula in Crohn's disease: transrectal vs transvaginal approach. Colorectal Disease. 2010;12(12):1183–1191. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.02029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwandner O. Video-assisted anal fistula treatment (VAAFT) combined with advancement flap repair in Crohn’s disease. Techniques in Coloproctology. 2013;17(2):221–225. doi: 10.1007/s10151-012-0921-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gingold D. S., Murrell Z. A., Fleshner P. R. A prospective evaluation of the ligation of the intersphincteric tract procedure for complex anal fistula in patients with crohn disease. Annals of Surgery. 2013 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000000479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.O'Riordan J. M., Datta I., Johnston C., Baxter N. N. A systematic review of the anal fistula plug for patients with Crohn's and non-Crohn's related fistula-in-ano. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2012;55(3):351–358. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0b013e318239d1e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lupinacci R. M., Vallet C., Parc Y., Chafai N., Tiret E. Treatment of fistula-in-ano with the Surgisis® AFPTM anal fistula plug. Gastroenterologie Clinique et Biologique. 2010;34(10):549–553. doi: 10.1016/j.gcb.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Starck M., Bohe M., Zawadzki A. Success rate of closure of high transphincteric fistulas using anal fistula plug. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 2008;51:692. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Van Koperen P. J., Bemelman W. A., Gerhards M. F., Janssen L. W. M., Van Tets W. F., Van Dalsen A. D., Slors J. F. M. The anal fistula plug treatment compared with the mucosal advancement flap for cryptoglandular high transsphincteric perianal fistula: a double-blinded multicenter randomized trial. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2011;54(4):387–393. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e318206043e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zubaidi A., Al-Obeed O. Anal fistula plug in high fistula-in-ano: an early saudi experience. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2009;52(9):1584–1588. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a90b65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grimaud J.-C., Munoz-Bongrand N., Siproudhis L., et al. Fibrin glue is effective healing perianal fistulas in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2275.e1–2281.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Venkatesh K. S., Ramanujam P. Fibrin glue application in the treatment of recurrent anorectal fistulas. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 1999;42(9):1136–1139. doi: 10.1007/BF02238564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lindsey I., Smilgin-Humphreys M. M., Cunningham C., Mortensen N. J. M., George B. D. A randomized, controlled trial of fibrin glue vs. conventional treatment for anal fistula. Diseases of the Colon and Rectum. 2002;45(12):1608–1615. doi: 10.1007/s10350-004-7247-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.de Parades V., Far H. S., Etienney I., Zeitoun J.-D., Atienza P., Bauer P. Seton drainage and fibrin glue injection for complex anal fistulas. Colorectal Disease. 2010;12(5):459–463. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1318.2009.01811.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sehgal R., Koltun W. A. Fibrin glue for the treatment of perineal fistulous Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138(7):2216–2219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Garcia-Olmo D., Garcia-Arranz M., Herreros D. Expanded adipose-derived stem cells for the treatment of complex perianal fistula including Crohn's disease. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2008;8(9):1417–1423. doi: 10.1517/14712598.8.9.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Singh U. P., Singh N. P., Singh B., Mishra M. K., Nagarkatti M., Nagarkatti P. S., Singh S. R. Stem cells as potential therapeutic targets for inflammatory bowel disease. Frontiers in Bioscience—Scholar. 2010;2(3):993–1008. doi: 10.2741/s115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.González M. A., Gonzalez-Rey E., Rico L., Büscher D., Delgado M. Adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells alleviate experimental colitis by inhibiting inflammatory and autoimmune responses. Gastroenterology. 2009;136(3):978–989. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sciaudone G., Pellino G., Riegler G., Selvaggi F. Infliximab in drug-naïve patients with failed ileorectal anastomosis for Crohn's disease: a new chance for sparing the rectum? European Surgical Research. 2011;46(4):163–168. doi: 10.1159/000324398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Pellino G., Sciaudone G., Candilio G., Camerlingo A., Marcellinaro R., Rocco F., De Fatico S., Canonico S., Selvaggi F. Complications and functional outcomes of restorative proctocolectomy for ulcerative colitis in the elderly. BMC Surgery. 2013;13(supplement 2, article S9) doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pellino G., Sciaudone G., Candilio G., Camerlingo A., Marcellinaro R., De Fatico S., Rocco F., Canonico S., Riegler G., Selvaggi F. Early postoperative administration of probiotics versus placebo in elderly patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery: a double-blind randomized controlled trial. BMC Surgery. 2013;13(supplement 2, article S57) doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-13-S2-S57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Selvaggi F., Pellino G., Canonico S., Sciaudone G. Systematic review of cuff and pouch cancer in patients with ileal pelvic pouch for ulcerative colitis. Inflammatory Bowel Disease. 2014;20(7):1296–1308. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]