Abstract

This review discusses the impact of neurotrophins and other trophic factors, including fibroblast growth factor and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor, on mood disorders, weight regulation and drug abuse, with an emphasis on stress- and drug-induced changes in the ventral tegmental area (VTA). Neurotrophins, comprising nerve growth factor, brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and neurotrophins 3 and 4/5 play important roles in neuronal plasticity and the development of different psychopathologies. In the VTA, most research has focused on the role of BDNF, because other neurotrophins are not found there in significant quantities. BDNF originating in the VTA provides trophic support to dopamine neurons. The diverse intracellular signaling pathways activated by BDNF may underlie precise physiological functions specific to the VTA. In general, VTA BDNF expression increases after psychostimulant exposures, and enhanced BDNF level in the VTA facilitates psychostimulant effects. The impact of VTA BDNF on the behavioral effects of psychostimulants relies primarily on its action within the mesocorticolimbic circuit. In the case of opiates, VTA BDNF expression and effects seem to be dependent on whether an animal is drug-naïve or has a history of drug use, only the latter of which is related to dopamine mechanisms. Social defeat stress that is continuous in mice or intermittent in rats increases VTA BDNF expression, and is associated with depressive and social avoidance behaviors. Intermittent social defeat stress induces persistent VTA BDNF expression that triggers psychostimulant cross-sensitization. Understanding the cellular and molecular substrates of neurotrophin effects may lead to novel therapeutic approaches for the prevention and treatment of substance use and mood disorders.

Keywords: BDNF, cross-sensitization, depression, drug abuse, social stress

Introduction

Neurotrophins are closely related neuropeptides of the nerve growth factor family that control many aspects of neuronal survival, development, growth, and functions such as synapse formation and synaptic plasticity (see review of Reichardt, 2006). Trophic support for midbrain dopaminergic neurons by local synthesis of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and neurotrophin-3 (NT-3) was initially described more than twenty years ago (Hyman et al., 1991; Gall et al., 1992). Prior to that, nerve growth factor (NGF) was identified and characterized in the pivotal research of Levi-Montalcini (1987), and found to act specifically on cholinergic neurons (Thoenen, 1991). Due to their critical effects, neurotrophins have accumulated more than ten thousand publications with multiple reviews in recent years, mostly concerning their molecular mechanisms and functional significance (for recent reviews see “BDNF special issue” of Neuropharmacology, 2014).

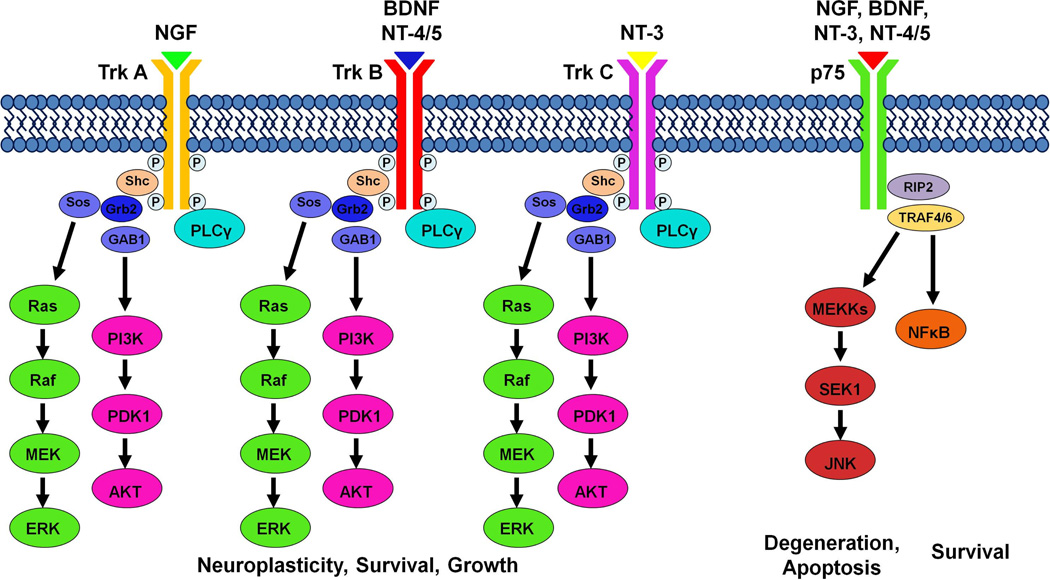

During the synthesis of neurotrophins, pro-neurotrophins are cleaved to produce the mature neurotrophin proteins (Mowla et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2005). Immature neurotrophins preferentially bind to the p75 neurotrophin receptor, while mature neurotrophins have a lower affinity for the p75 receptor and show ligand specificity for the tropomyosin-related kinase (Trk) family of receptor tyrosine kinases (Figure 1; Segal, 2003; Longo and Massa, 2013). BDNF and neurotrophin-4 (NT-4) recognize the TrkB receptor, while NGF binds specifically with TrkA, and NT-3 activates TrkC (Chao, 2003; Reichardt, 2006). Trk receptor dimerization leads to trans-autophosphorylation and activation of intracellular signaling cascades that are activated by BDNF. Three well characterized intracellular signaling pathways include the Ras/extracellular signal regulated kinase (ERK), the phosphatidylinositol-3’-OH-kinase (PI3K)-AKT pathway, and the phospholipase C-γ (PLC-γ) pathway (Figure 1; for more details see the recent review by Park and Poo, 2013). Many of the intracellular signaling components that mediate neurotrophin signaling, such as ERK, AKT, PLC, PKC, Ras, JNK, and NF-κB, are not unique to neurotrophins, and these common elements may serve as cross-talk tools between neurotrophins and other neurotransmitter systems.

Figure 1. Neurotrophin ligand-receptor specificity and intracellular signaling cascades.

Neurotrophins show ligand specificity for Trk receptors, and activate intracellular signaling cascades, including Ras/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and PLCγ to alter neuronal survival, growth and neuroplasticity. Trk receptor activation results in the recruitment of Src homology domain-containing protein (Shc) and PLCγ to the intracellular domain. Localization of Shc to the receptor site recruits growth factor receptor bound protein 2 (Grb 2), which recruits the intermediary proteins Sos and GAB1 to activate the Ras/ERK and PI3K/AKT pathways, respectively. Upon activation, the Ras/ERK, PI3K/AKT, and PLCγ signaling pathways can activate other signaling pathways, as well as nuclear factors. In addition, all neurotrophins can bind to p75 to activate the Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) or nuclear factor kappa B (NFκB) intracellular signaling cascades responsible for neuronal fate and apoptosis. P75 receptor activation recruits receptor interacting protein 2 (RIP2) and tumor necrosis factor receptor associated factor 4/6 (TRAF4/6). Depending on context, neurotrophins binding to the p75 receptor can activate either the NFκB pathway to promote survival and augment Trk effects, or the JNK pathway to promote apoptosis and antagonize the effects of Trk receptors. For additional details on neurotrophin ligand-receptor signaling, see reviews by Segal (2003), Reichardt (2006), Longo and Massa (2013).

Expression of BDNF, perhaps the most widely studied neurotrophin, is intimately regulated by neural activity. Detailed mapping of BDNF immunolabeling and mRNA expression have revealed that the VTA contains a medium-to-high density of BDNF expression. At the same time, mesolimbic projection areas such as the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and nucleus accumbens (NAc) have distinctive BDNF immunoreactive fibers and intracellular protein in the absence of mRNA expression, suggesting anterograde axonal transport of BDNF protein via afferent systems (Conner et al., 1997). BDNF is further known to undergo both retrograde and anterograde transport (Altar et al., 1997). The prefrontal cortex (PFC) contains dense BDNF mRNA-expressing neurons (Conner et al., 1997), which supply BDNF to both the NAc and VTA, thereby mediating the functions of these brain regions (Seroogy et al., 1994; Guillin et al., 2001).

Populations of various neuronal types are differentially distributed throughout the rostrocaudal and mediolateral axes of the VTA (Nair-Roberts et al., 2008). The VTA as a whole contains mainly dopaminergic neurons (50 – 65%), with approximately 1/3 GABAergic neurons (30 – 35%; Swanson, 1982; Oades and Halliday, 1987; Yamaguchi et al., 2007; Nair-Roberts et al., 2008) and a few glutamatergic neurons (2–3%; Nair-Roberts et al., 2008). Glutamatergic neurons, as defined by their expression of vesicular glutamate transporter type 2, are mostly confined to the medial portion of the rostral VTA (Kawano et al., 2006; Nair-Roberts et al., 2008). Some VTA neurons that release glutamate also express tyrosine hydroxylase, the rate-limiting enzyme in the synthesis of dopamine (Tagliaferro and Morales, 2008; Yamaguchi et al., 2011).

In the VTA, approximately 50% of all neurons were found to co-label for both tyrosine hydroxylase and BDNF (Seroogy et al., 1994). The diverse intracellular signaling pathways activated by BDNF may represent precise physiological functions specific to the VTA, such as behavioral response to drug and natural reward, stress, and some mood disorders. These functions can be studied using viral-mediated gene transfer (Carlezon et al., 2000) to manipulate selectively the expression of a single gene in a specific brain region at a particular time.

This review will focus on recent work assessing the role of neurotrophin-activated intracellular signaling cascades in social stress, depression, and the behavioral effects associated with drugs of abuse.

VTA BDNF in depression and susceptibility to stress

The involvement of mesolimbic dopamine in human and animal models of depression has been known since the early 1980s. Evidence for dysfunction of dopamine neurotransmission in major depression began with the observation that reduced dopamine metabolites are present during anhedonia-like behavior, and that antidepressant treatment increases mesolimbic dopamine transmission (Chiodo and Antelman, 1980; Willner, 1983). Exposure to a stressful situation changes mesolimbic dopamine release, and causes the development of stress-induced reward devaluation and anhedonia-like behavior (see reviews by Zacharko and Anisman, 1991; Cabib and Puglisi-Allegra, 1996).

BDNF is expressed in regions that both produce and receive dopamine (Seroogy et al., 1994; Conner et al, 1997). The expression of BDNF has been broadly implicated in both major depression and bipolar disorder; in fact, many of the drugs used to treat these disorders alter BDNF expression and signaling (for reviews see Hashimoto et al., 2004; Post, 2007; Calabrese et al., 2009). In respect to depression, the function of BDNF has been most widely studied in the hippocampus, since decreased hippocampal BDNF expression is consistently associated with depressive-like behavior. Moreover, antidepressant treatment has been shown to up-regulate BDNF in the hippocampus, whereas behavioral effects of such therapies are prevented by blockade or genetic deletion of BDNF (for review see Duman and Monteggia, 2006; Duman and Voleti, 2012). By contrast, increased BDNF levels within the mesolimbic dopamine system are associated with the development of a depressive-like phenotype. It has been hypothesized that BDNF in the mesolimbic pathway (VTA - NAc), which is implicated in the rewarding effects of drugs of abuse and natural rewards, is pro-depressive – an effect opposite to its role in the hippocampus (Nestler and Carlezon, 2006). While it is tempting to characterize elevated VTA BDNF as pro-depressive, it is important to note that chronic treatment with the antidepressant fluoxetine increased BDNF expression in both the hippocampus and VTA, as well as in the PFC and NAc shell (Molteni et al., 2006). Furthermore, while electroconvulsive shock is an effective treatment for extreme cases of major depression in humans, and its use in experimental animals results in increased BDNF expression in the hippocampus, knockdown of hippocampal BDNF was not sufficient to prevent the antidepressant effects of electroconvulsive shock (Taliaz et al., 2013). Instead, the antidepressant behavioral response to electroconvulsive shock was associated with reduced VTA BDNF expression, while BDNF overexpression in the VTA blocked its antidepressant effects (Taliaz et al., 2013).

Behavioral animal models of depression include immobility in the forced swim test, decreased social interactions following social defeat stress, and reduction of sucrose intake after chronic stress that might reflect anhedonia (see review of Krishnan and Nestler, 2008). Some evidence suggests a similar role for mesolimbic BDNF in rats and in mice, whereby increasing VTA BDNF enhances learned helplessness and decreases social interactions. Several experimental approaches have demonstrated the involvement of VTA BDNF signaling in rodent models of depression. For example, intra-VTA BDNF protein infusion produces depressive-like behavior in the forced swim test in rats (Eisch et al., 2003). Our own experiments have shown that intermittent social defeat stress, where an experimental animal is subjected to aggressive confrontation with a counterpart, induces prolonged BDNF expression in the VTA (Fanous et al., 2010). Moreover, intermittent social defeat stress causes chronic alterations in social behavior; rats exhibit reduced social interactions with a novel conspecific and increased social avoidance (Fanous et al., 2011b). By contrast, bilateral knockdown of VTA BDNF prior to intermittent social defeat stress alleviates the effects of stress on social behavior measured seven weeks after stress. These findings in rats agree with the results in a mouse model of continuous social defeat stress (Table 1), which increased BDNF activity within the mesolimbic dopamine pathway (VTA and NAc), and produced depressive-like symptoms, including social avoidance, enhanced susceptibility to stress, and reduced sucrose preference (Berton et al., 2006; Krishnan et al., 2007). Furthermore, these behavioral alterations induced by continuous social defeat stress were blocked by mesolimbic BDNF knockdown. Interestingly, a history of winning experiences during daily agonistic interactions in mice has also been shown to increase BDNF mRNA expression in the VTA, suggesting that BDNF may be involved in a general behavior-induced activation of dopamine neurons (Kudryavtseva et al., 2010).

Table 1.

Effects of different procedures of social defeat stress on VTA BDNF, depressive-like and drug-related behaviors, and other neurochemical changes. Arrows indicate direction of alterations, PR = progressive ratio.

| Species | Rats | Mice | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stress regimen | Intermittent social defeat stress (4×10 days) |

Continuous social defeat stress for 36 consecutive days |

Continuous social defeat stress for 10 consecutive days |

| Behavioral changes | Sensitization ↑ Self-administration: • Acquisition ↑ • PR ↑ • Binge ↑ Social interactions ↓ |

Sucrose preference ↓ Sensitization ↓ Self-administration: • Acquisition ↓ • PR ↓ • Binge↓ |

Social interaction↓ Sucrose preference ↓ Susceptibility to stress ↑ |

| Neurochemical changes/Neuroplasticity | 1 h after stress: ↑ BDNF in PFC, AMY |

BDNF in VTA ↓ | BDNF in VTA ↑ phospho-AKT, GSK-3β and ERK1/2 in VTA ↑ Firing frequency of VTA DA neurons ↑ |

| 28 day after stress: ↑ BDNF in VTA and AMY | |||

| References | (Miczek et al, 2011; Fanous et al, 2010, 2011) | (Berton et al, 2006; Krishnan et al, 2007) | |

While various social defeat models produce social avoidance of a novel conspecific and are often spoken of interchangeably, it should be noted that not all models of social defeat produce the same changes in behavior and mesolimbic BDNF expression; intermittent and continuous social defeat stress exposure in rats produce opposite effects on VTA BDNF expression and some behaviors (Table 1; Fanous et al., 2010; Miczek et al., 2011). Continuous social defeat stress reduced sucrose preference and intake, decreased exploratory behavior, and reduced VTA BDNF in defeated rats, while VTA BDNF increased only in intermittently defeated rats. This finding that rats undergoing continuous social defeat stress have lower levels of VTA BDNF contradicts the increase in VTA BDNF seen in mice after continuous social defeat stress, and suggests that the effects of social defeat stress may differ across species. Drawing similar conclusions across laboratory rats and mice regarding conspecific aggression warrants caution, as differences in behavioral responses to stress, such as defensive freezing, may exist across species (Blanchard et al., 2001; Blanchard et al., 2003). Social aggression and defense are complex behaviors, and inter-species variation of these behaviors suggests the possibility that they are mediated by different mechanisms (Table 1). Moreover, most studies of BDNF signaling in the mouse model of continuous social defeat stress have utilized the C57BL6 strain, and significant inter-strain differences exist in mouse models of depressive-like behavior (Nikulina et al., 1991; Bai et al., 2001).

Individuals display wide variation in responses to stress, and are often described as either susceptible or resilient. Resilience refers to an individual’s ability to successfully avoid the negative consequences of stress (for review see Feder et al., 2009; Russo et al., 2012). Continuous social defeat stress in mice produces enhanced VTA dopamine excitability, and consequently increases activity-dependent release of BDNF in the NAc, and is accompanied by long-lasting reduction of social interactions and the development of social avoidance (Krishnan et al., 2007). Based on social interaction/avoidance, sucrose preference, circadian amplitudes, and social hyperthermia data, these mice can be divided into susceptible or resilient subpopulations. Preventing increases in the firing of VTA dopamine neurons or blocking downstream BDNF signaling in the NAc was sufficient to normalize social behaviors and anhedonia. This increase in NAc BDNF protein levels in susceptible mice suggests that increased BDNF in the NAc is a consequence of enhanced activity-dependent BDNF transport from VTA dopamine neurons. Remarkably, postmortem analysis of human NAc tissue revealed that depressed patients also had higher levels of NAc BDNF protein (Krishnan et al., 2007). It has been suggested that BDNF functions as a stress detector along the mesolimbic pathway. Evidence in support of this comes from an optogenetic study showing that increased phasic stimulation of the VTA dopamine pathway in stress-naïve mice is not sufficient to produce social avoidance or increased NAc BDNF expression. After social stress with subsequent enhanced firing of VTA dopamine neurons, both social avoidance and increased NAc BDNF expression were observed (Walsh et al., 2014). This stress-induced BDNF expression was found to be dependent upon a corticotropin releasing hormone acting in the NAc, suggesting that the putative stress-detecting function of BDNF depends on various components of, and interactions within, the mesolimbic pathway.

In many studies of VTA BDNF signaling in depressive-like behaviors, susceptible mice exhibit significantly less of the active, phosphorylated form of AKT within the VTA, while chronic antidepressant treatment increased phospho-AKT in the VTA (Krishnan and Nestler, 2008). Additionally, ERK signaling in the VTA has been shown to regulate vulnerability to continuous social defeat stress (Iniguez et al., 2010). Viral-mediated overexpression of the ERK2 isoform in rats was sufficient to increase anxiety on an elevated plus maze, and in mice resulted in enhanced susceptibility to social defeat stress. Blocking ERK2 activity was accompanied by reduced firing of VTA dopamine neurons, suggesting that ERK2 blockade may confer resiliency to stress (Iniguez et al., 2010). PLCγ1 in the VTA also has a prominent role in the regulation of anxiety-like behavior and sucrose preference (Bolanos et al., 2003). Overexpression of PLCγ1 produced two distinct behavioral phenotypes depending on the affected VTA subregion. PLCγ1 overexpression in the rostral VTA increased reward preference for sucrose, while increased PLCγ1 in the caudal VTA reduced sucrose preference and enhanced sensitivity during axiogenic challenges. These studies demonstrate that the signaling pathways associated with VTA BDNF (Figure 1) play an essential role in mood disorders, and critically influence susceptibility vs. resiliency to stressors. While BDNF modulation of VTA dopamine transmission is an important outcome of these intracellular signaling pathways, it is likely that such neurotrophin pathways also function to control indirectly other neurotransmitter systems.

BDNF in the VTA and weight regulation

Recent investigations have revealed that BDNF acting at the TrkB receptor plays an important role in the regulation of energy balance in humans and animals (for reviews see Cordeira and Rios, 2011; Rios, 2013). Food intake represents a behavioral complex of energy homeostasis and reward-related food consumption. The mesolimbic dopamine system mediates reward-seeking behavior, which includes natural rewards like palatable food intake. In this regard, consumption of high-fat food alters the expression of BDNF and TrkB receptor mRNA in the VTA of wild-type mice, while mutant mice with VTA-specific depletion of BDNF increased their food consumption and body weight when given the same high-fat diet (Cordeira et al., 2010). However, when these mutant mice were given standard mouse chow, they did not exhibit significant increases of consumption or weight gain, suggesting that the effect of VTA BDNF is related to the rewarding rather than consumatory properties of eating. Mutant mice with depleted VTA BDNF were further characterized by diminished dopamine release in the NAc. Consistent with these findings in mice, knockdown of VTA BDNF in rats induces increased food intake and weight gain (Fanous et al., 2011b). Moreover, depleting VTA BDNF conferred resistance to the reductions in body weight normally observed after social defeat stress, and generally enhanced weight gain regardless of stress history. These data implicate VTA BDNF in weight regulation, even when induced by social stress, which is consistent with the role of BDNF in the VTA-NAc pathway that has previously been associated with depressive-like behavior (Nestler and Carlezon, 2006).

Interestingly, the effects of BDNF on food consumption appear to be limited to highly palatable foods, and differ during dietary administration and withdrawal (Sharma et al., 2013). Specifically, mesolimbic BDNF expression was unaffected in mice fed low-or high-fat diets, but BDNF increased in the NAc during withdrawal from a high fat diet when mice exhibited elevated palatable food reward (Sharma et al., 2013). Food restriction has been shown to reduce TrkB receptor level in the VTA without altering the expression of BDNF protein (Pan et al., 2011). Food restriction was also shown to increase VTA phospho-ERK1/2, a mediator of synaptic plasticity and downstream target of BDNF. These results suggest reciprocal effects of food consumption on VTA neuronal TrkB signaling and synaptic dopamine release (Pan et al., 2011). Chronic food restriction has also been associated with increased sensitivity to drugs of abuse (Carroll and Meisch, 1981; Stuber et al., 2002), suggesting that VTA BDNF signaling may facilitate the rewarding properties of such drugs.

VTA BDNF in drug abuse and drug-seeking behavior

Similar to the effects of social stress, most drugs of abuse enhance dopamine transmission along the mesolimbic pathway. The expression of BDNF has been associated with increased dopamine metabolism, turnover, and activity-induced release from midbrain dopaminergic neurons (Altar et al., 1992; Martin-Iverson et al., 1994; Blochl and Sirrenberg, 1996; Feng et al., 1999; Goggi et al., 2002). In addition to its role in regulating dopamine release, VTA BDNF is also necessary for the maintenance of dopamine D3 receptor expression in the NAc shell (Guillin et al., 2001), a brain region implicated in the effects of drugs of abuse. Alterations in mesocorticolimbic BDNF expression have been associated with many drugs with the potential for abuse (Numan et al., 1998; Meredith et al., 2002; McGough et al., 2004; Le Foll et al., 2005; Fumagalli et al., 2007), and a substantial body of research suggests that BDNF expression is associated with susceptibility to drugs of abuse (Berhow et al., 1995; Guillin et al., 2001; Hall et al., 2003; Flanagin et al., 2006; Tsai, 2007; Thomas et al., 2008). Given the pivotal modulatory role for BDNF in long-term synaptic plasticity (Kang and Schuman, 1995; Levine et al., 1995; Patterson et al., 1996; Kovalchuk et al., 2002), drug-induced BDNF expression in the VTA may facilitate the persistent neuroplastic changes induced by drugs of abuse, which underlie an entire repertoire of addictive behaviors. The NAc is the primary neural substrate for drugs of abuse, and receives direct projections from the VTA. As such, for the purpose of this review, the impact of VTA BDNF signaling on the behavioral effects of abused drugs must be discussed in the context of this mesolimbic circuit.

VTA BDNF and drug-induced sensitization

Intermittent administration of a drug of abuse is known to induce progressive augmentation of behavioral activity, a phenomenon known as “sensitization” (Kalivas and Stewart, 1991). Sensitization is critical to the development of addiction, and individual differences in drug sensitization are thought to underlie individual differences in susceptibility to addiction. The process of sensitization has been well characterized in the context of psychomotor stimulants (Dougherty and Ellinwood, 1981), and is also observed with opiates (Babbini et al., 1975; Kornetsky, 2004). The VTA is required for the induction of behavioral sensitization to both opiates and psychomotor stimulants (Joyce and Iversen, 1979; Vezina et al., 1987; Vezina and Stewart, 1990). Chronic BDNF infusions into the NAc or VTA enhance the initial psychomotor effects of cocaine, facilitate the development of cocaine-induced sensitization and induce long-lasting increases in reinforcing efficacy that can be observed more than one month after the cessation of BDNF infusions (Table 2; Horger et al., 1999). Moreover, three daily intra-VTA BDNF infusions progressively increased locomotor activity compared to saline-infused rats, suggesting that repeated intra-VTA BDNF infusion itself can induce sensitization (Pierce et al., 1999). Additionally, overexpression of BDNF or TrkB receptor in the NAc caused enhanced cocaine-induced locomotor activity and conditioned place preference, delayed extinction and increased reinstatement, while NAc overexpression of TrkT1, a dominant negative form of TrkB, prevented increased sensitivity to the effects of cocaine (Bahi et al., 2008). Increased TrkB receptor phosphorylation is observed in the NAc within hours of a single injection of cocaine, and TrkB signaling is required for both subsequent behavioral sensitization and conditioned place preference to cocaine (Crooks et al., 2010). In contrast to the potentiating effect of BDNF on the behavioral effects of cocaine or morphine (Table 2), chronic cocaine and morphine treatment both induced increases in VTA tyrosine hydroxylase levels and ERK activity, which were both prevented by chronic intra-VTA infusions of BDNF (Beitner-Johnson and Nestler, 1991; Berhow et al., 1995; Berhow et al., 1996). Such chronic intra-VTA BDNF infusions alone were sufficient to reduce total VTA levels of ERK protein without affecting the levels of phosphorylated ERK, suggesting that BDNF can enhance the efficiency of ERK activation (Berhow et al., 1996). Although ERK activation is one potential downstream effect of opioid receptor stimulation, modulation of ERK through its upstream effector mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK; Figure 1) was not observed in the VTA after either acute or repeated morphine treatment. Increased MAPK-ERK activity was present in cortical areas, but not in neurons expressing mu-opioid receptors (Eitan et al., 2003). Chronic cocaine and morphine have also been found to increase the activity of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and adenyl cyclase in the NAc (Terwilliger et al., 1991), which can be prevented by intra-VTA infusion of BDNF (Berhow et al., 1995).

Table 2.

Effects of VTA BDNF on drug-related behaviors and changes in neurochemistry

| Manipulation | Drug Type | Behavioral Effect | Neurochemical and Neuroplastic Changes |

References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intra-VTA BDNF Infusion | Psycho-stimulants | Cue-induced Reinstatement ↑ | BDNF Effect can be reversed by MEK inhibitor (U012) | Lu et al., 2004 |

| Conditioned Response ↑ | ERK activity • Drug or BDNF alone: ↑ • BDNF plus chronic drug: ↓ |

Horger et al., 1999, Berhow et al., 1996 | ||

| Sensitization ↑ | ||||

| Opiates | Shifts DA-independent and DA-dependent systems (dependent on drug history) | GABAA receptor switches from inhibitory to excitatory on VTA GABA interneurons | Vargas-Perez et al., 2009 | |

| Morphine-induced conditioned place preference ↓ | Morphine-induced increases of excitability of VTA DA neurons ↓ | Koo et al., 2012 | ||

| Viral Vector-Mediated Overexpression of VTA BDNF | Amphetamine | Social defeat stress-induced cross-sensitization ↑ | ↑ of ΔFosB in the PFC and NAc | Wang et al., 2013b |

| Cocaine | Self-administration • Acquisition ↑ • Drug taking during a 12 hr binge ↑ |

ΔFosB in the NAc ↑ BDNF in the infralimbic cortex ↓ |

Wang et al., 2013a |

Ten to fourteen days after termination of repeated cocaine injections, VTA dopaminergic neurons are more susceptible to excitatory synaptic inputs; this synaptic potentiation is dependent on local BDNF-TrkB receptor signaling and has been replicated in drug-naïve rats receiving intra-VTA BDNF administration (Pu et al., 2006). Thus, it is highly likely that VTA BDNF signaling can prime local dopaminergic neurons to excitatory input, which may alter basal dopamine levels and activity-induced dopamine release in VTA terminal regions, such as the NAc (Heidbreder et al., 1996). The potentiating effect of BDNF on synaptic plasticity in dopamine neurons of the mesolimbic circuit could be caused by increased presynaptic neurotransmitter release, possibly through enhanced synaptic activity (Jovanovic et al., 2000), or by enhanced postsynaptic response, potentially via increased AMPA receptor expression (Li and Wolf, 2011; Fortin et al., 2012), or some combination of these mechanisms.

It has been established that alterations in both dopaminergic and glutamatergic transmission throughout the mesocorticolimbic system contribute to behavioral sensitization (Vanderschuren and Kalivas, 2000). In the VTA, glutamatergic input is critical for behavioral sensitization following repeated psychostimulant exposure. For example, intra-VTA infusion of an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor antagonist is sufficient to prevent amphetamine sensitization. One of the major sources of glutamatergic input to the VTA is the PFC; a considerable portion of VTA afferents activated by amphetamine project from the PFC (Colussi-Mas et al., 2007). Furthermore, chronic AMPH administration can potentiate the response of VTA dopamine neurons to electrical stimulation of the PFC (Tong et al., 1995), and the medial PFC is the only source of glutamate to the VTA that is essential for drug sensitization (Cador et al., 1999). In fact, BDNF acts on glutamatergic neurons to potentiate neurotransmitter release (Lessmann et al., 1994; Li et al., 1998). Taken together, these data suggest that the synaptic strength of PFC glutamatergic projections to the VTA is enhanced following repeated psychostimulant treatment, which may promote the induction of behavioral sensitization. In addition, rats sensitized to amphetamine have significantly higher levels of BDNF expression in the medial PFC and VTA compared to drug-naïve rats (Fanous et al., 2011a). Moreover, the largest populations of activated neurons co-expressing BDNF and Fos were found in these two brain regions after the onset of behavioral sensitization. Thus, it is possible that BDNF-expressing neurons in the PFC-VTA pathway are likely to undergo psychostimulant-induced neural activation. Consequently, increased BDNF expression in the medial PFC may be a molecular substrate that engenders enhanced synaptic efficacy in a set population of PFC neurons following repeated injections of amphetamine (Gulley and Stanis, 2010). Ultimately, such BDNF-induced enhancement of excitatory VTA input from medial PFC could result in behavioral sensitization to psychomotor stimulants.

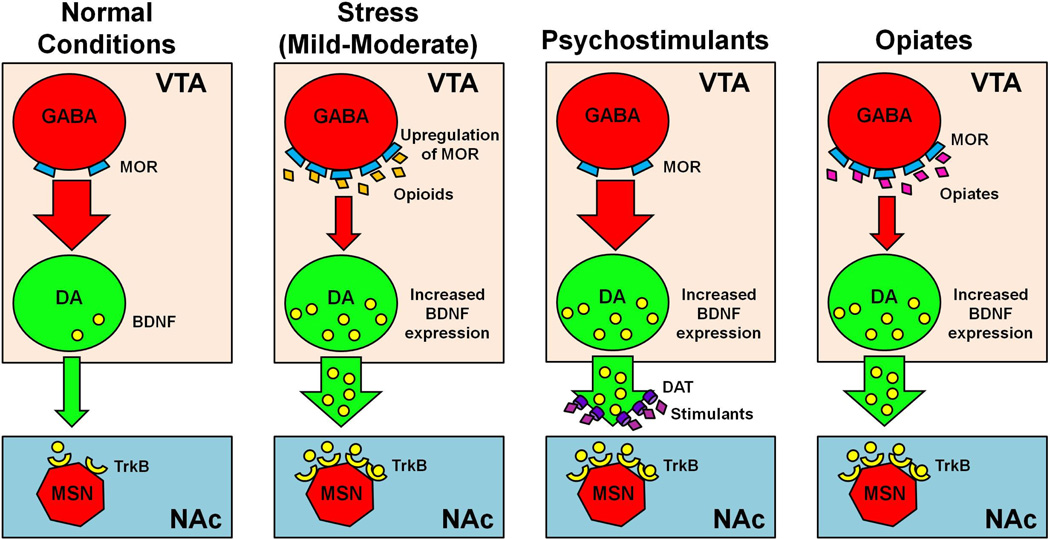

Although BDNF potentiates synaptic plasticity in mesolimbic dopamine and PFC glutamatergic neurons, abundant evidence suggests that BDNF is also capable of reducing the efficacy of synaptic transmission. In cultured hippocampal neurons, BDNF reduces the amplitude of inhibitory postsynaptic currents through various mechanisms, including the regulation of chloride ion transport and downregulation of GABAA receptor expression on the cell surface (Brünig et al., 2001; Wardle and Poo, 2003). While the bulk of evidence on such inhibitory effects of BDNF primarily derives from hippocampal neuron cultures, the intriguing possibility exists that BDNF might act to inhibit local GABAergic neurons in other brain regions, such as the VTA, thereby disinhibiting neurons targeted by these GABA projections. For example, reduced inhibition of VTA dopaminergic neurons by local GABAergic neurons has been observed after repeated cocaine treatment, thereby facilitating LTP induction (Liu et al., 2005). Furthermore, cocaine-induced attenuation of the strength of local VTA GABAergic inhibition is ERK-signaling dependent, since intra-VTA infusion of an ERK inhibitor is capable of reducing the rewarding efficacy of cocaine (Pan et al., 2011). Thus, VTA BDNF expression seems capable of influencing the activity of local dopamine neurons in two ways: either through direct potentiation of the response of dopaminergic neurons to excitatory input or through indirect potentiation of local dopaminergic activity by inhibition of VTA GABAergic neurons (Figure 2). Such BDNF-mediated potentiation of VTA dopamine neurons may represent a critical molecular mechanism underlying sensitization to psychostimulants.

Figure 2. Effects of drugs and stress on VTA BDNF expression and mesolimbic tone.

Under normal conditions, VTA GABA neurons express low levels of mu-opioid receptors (MORs) and tonically inhibit VTA dopamine (DA) neurons, producing low levels of DA neurotransmission to NAc medium spiny neurons (MSNs). After intermittent social defeat stress, MORs are upregulated on VTA GABAergic neurons, resulting in disinhibition of VTA DA neurons and enhanced BDNF expression (Johnston et al., 2012). In general, psychostimulant drugs increase DA in the synaptic cleft by blocking dopamine transporter (DAT) or releasing DA from pre-synaptic terminals, which leads to induction of VTA BDNF and its release in the NAc (Graham et al., 2009; Wang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2013b), while opiates act on VTA GABA neurons, disinhibiting VTA DA signaling and increasing BDNF expression (Vargas-Perez et al., 2009; Ting et al., 2013). In summary, stress, psychostimulants, and opiates all increase DA and BDNF signaling, albeit through different mechanisms.

Size of red/green arrows represent strength of GABA or DA neurotransmission; large red circle: GABA neuron; large green circle: DA neuron; small blue trapezoids: MORs; orange diamonds: endogenous opioids; pink diamonds: exogenous opiates; purple diamonds: psychostimulant drugs; purple cylinders: DAT; small yellow crescents: TrkB receptors; small yellow circles: BDNF molecules; red heptagon: MSN.

VTA BDNF and opiate abuse

Compared to psychostimulants, which increase extracellular dopamine levels by targeting dopamine transporters (Jones et al., 1999; Brown et al., 2001; Schmitz et al., 2001), opiates and endogenous opioids induce hyperpolarization of GABAergic neurons that tonically inhibit dopamine neurons (Figure 2; Gysling and Wang, 1983; Johnson and North, 1992). By inhibiting GABA release, opiates and opioids act to disinhibit dopamine neurons and to increase dopamine transmission (for review of opiate-induced neuroadaptations, see Christie, 2008). Recent studies reveal that GABAergic input from the rostromedial tegmental nucleus, also known as the tail of the VTA (tVTA), comprises a dense projection to rostral VTA dopamine neurons (Jalabert et al; 2011; Matsui and Williams, 2011). These GABAergic neurons are sensitive to mu-opioid receptor activation, which produces hyperpolarization to inhibit their firing, thereby disinhibiting VTA dopamine neurons (Matsiu and Williams, 2011).

Comprehensive analyses of VTA BDNF signaling during opiate abuse have not always agreed. While one study found that VTA BDNF protein was reduced from 1 to 14 days after termination of chronic morphine treatment (Chu et al., 2007), another study reported that VTA BDNF increased significantly 7 days after chronic morphine treatment (Mashayekhi et al., 2012). Yet another revealed that VTA BDNF mRNA expression was unaffected by chronic morphine either immediately after treatment or following shortterm (24 hr) withdrawal (Numan et al., 1998). Chronic morphine-induced alteration of VTA BDNF is thought to be mediated in part by histone H3K9 trimethylation, an epigenetic modification that is associated with repression of transcription on promoter II of the bdnf gene (Mashayekhi et al., 2012). As occurs in psychostimulant sensitization, progressively augmented motor behavioral responses are also observed following repeated opiate treatment (Babbini et al., 1975; Vezina et al., 1987; Kornetsky, 2004). Locomotor sensitization in a morphine-paired environment has been shown to be accompanied by significant increases of BDNF in the NAc. This sensitization can be prevented by intra-NAc infusion of anti-TrkB immunoglobulin (Liang et al., 2011), suggesting that mesolimbic BDNF-TrkB signaling is necessary for behavioral sensitization to opiates.

In contrast to the positive modulatory affect that VTA BDNF has on the actions of psychostimulants, VTA BDNF has been shown to suppress the effects of morphine (Table 2). For example, morphine-induced increases in the excitability of dopaminergic neurons and their rewarding effects have been shown to be blocked by intra-VTA BDNF infusion in mice (Koo et al., 2012). Chronic morphine treatment has also been associated with reduced soma size of mesolimbic dopaminergic neurons (Sklair-Tavron et al., 1996), and a concomitant reduction in the number of BDNF-positive cells in the VTA (Chu et al., 2007). Both effects are blocked by direct or indirect enhancement of VTA BDNF. Chronic morphine treatment has also been shown to increase VTA ERK activity, an effect which can be prevented by intra-VTA infusion of BDNF (Berhow et al., 1996). However, others have failed to note increased ERK signaling in the VTA after either acute or chronic morphine treatment, although ERK activity increased in some cortical regions (Eitan et al., 2003). Collectively these data suggest that while BDNF signaling in the VTA may have an antagonistic effect on chronic morphine-induced neuroadaptations, its effects are not solely due to changes in the ERK signaling pathway.

While several studies have shown that increased VTA BDNF expression is sufficient to prevent the effects of chronic morphine treatment, there are also several lines of evidence suggesting that increased VTA BDNF expression in opiate-naïve rats potentiates a shift from a drug non-dependent to a drug-dependent state. After 16 hours of withdrawal from chronic heroin treatment, opiate-dependent rats exhibited significantly greater expression of BDNF protein and mRNA in the VTA, effects that were not present after 15 days of withdrawal or following a single injection of heroin (Vargas-Perez et al., 2009). In non-dependent rats, opiate reward is mediated by non-dopaminergic processes in the VTA (Figure 2), but after chronic opiate treatment and during withdrawal, reward becomes dependent on the mesolimbic dopamine system (Laviolette et al., 2002). While a single infusion of BDNF into the VTA was sufficient to induce this shift from dopamine-independent to dopamine-dependent reward signaling in opiate non-dependent rats, BDNF was unable to alter the magnitude of the effect of conditioned place preference to morphine unless combined with systemic pretreatment with alpha-flupenthixol, a dopamine receptor antagonist (Vargas-Perez et al., 2009). VTA BDNF facilitates a shift to an opiate-dependent state in drug-naïve rats. However, once the dopamine-dependent system has been activated, VTA BDNF functions to antagonize the effects of opiate drugs (Table 2).

Intra-VTA infusion of the GABAA receptor antagonist, bicuculline, produces a rewarding effect in opiate-naïve rats that cannot be blocked by a dopamine antagonist, unless BDNF was previously infused into the VTA (Vargas-Perez et al., 2009). After chronic morphine treatment and withdrawal, the electrophysiological properties of the GABAA receptor switch from inhibitory to excitatory, such that 44% of VTA GABAergic neurons exhibit increased activity in response to the GABAA receptor agonist, muscimol (Laviolette et al., 2004). When BDNF was infused into the VTA of opiate-naïve rats, a similar proportion of VTA GABAergic neurons switched from inhibitory to excitatory GABAA receptor signaling (Vargas-Perez et al., 2009), but BDNF had no effect on the function of GABAB receptors. The shift in a subset of VTA GABAergic neurons during opiate dependence may be due to a breakdown of chloride ion clearance through the potassium-chloride symporter, resulting in relatively greater bicarbonate ion efflux, and causing the signaling properties of GABAA receptors to shift from inhibitory to excitatory (Ting et al., 2013). Blockade of the symporter by furosemide in the VTA of opiate-naïve rats also induces a shift from inhibitory to excitatory GABAA receptor signaling, which can be blocked by inhibiting the enzyme that catalyzes the formation of bicarbonate ions. Thus, it is possible that the BDNF-induced shift from inhibitory to excitatory GABAA receptor signaling is also due to partial alterations of the potassium-chloride symporter and/or bicarbonate formation (Rivera et al., 2004; Wake et al., 2007; Ting et al., 2013). These data suggest that increased BDNF signaling in the VTA has specific effects on GABAergic neuronal activity.

VTA BDNF and psychostimulants self-administration

Drug treatments that induce psychomotor sensitization are also known to facilitate subsequent drug taking during self-administration with extended drug access (Ferrario and Robinson, 2007). Conversely, extended access to cocaine during self-administration is capable of inducing locomotor sensitization to cocaine one month after the cessation of self-administration (Ferrario et al., 2005). These findings suggest that the neural changes mediating psychomotor sensitization are important for the transition from casual drug use to abuse, and imply that incentive sensitization and psychomotor activation share common neural substrates. The laboratory model of drug self-administration in animals has predictive validity to addiction-like behavior in humans (Weeks, 1962), and this model has been used to study the role of mesolimbic BDNF-TrkB signaling during drug intake, seeking, and relapse. Cocaine self-administered for 14 days resulted in significant elevations of NAc BDNF immediately after the last self-administration session (Fumagalli et al., 2013). A separate study found similar increases in NAc BDNF expression after 3 weeks of active cocaine self-administration (Graham et al., 2009).

Abstinence following chronic self-administration, often referred to as the “withdrawal” period, allows time for the neuroplasticity induced by drug self-administration to fully develop. While many neurochemical changes take place during abstinence following self-administration, increased BDNF expression occurs progressively in several parts of the mesolimbic circuit (e.g., VTA, NAc, and amygdala) for up to 90 days after cessation of cocaine self-administration (Grimm et al., 2003). Such alterations of VTA BDNF expression are caused, at least in part, by epigenetic modification of promoter 1 of the bdnf gene (Schmidt et al., 2012). In fact, VTA BDNF overexpression facilitates the acquisition of cocaine self-administration, and is positively correlated with drug taking during a 12 hour cocaine binge (Table 2; Wang et al., 2013a). Furthermore, overexpression of BDNF and TrkB in the NAc enhances cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization, conditioned place preference and reinstatement, while expression of a dominant negative form of TrkB prevents such changes (Bahi et al., 2008), and NAc TrkB knockdown reduces cocaine self-administration (Graham et al., 2009).Taken together, these data suggest that while enhanced VTA BDNF is sufficient to engender susceptibility to psychomotor stimulants, such enhanced psychostimulant-taking behaviors are dependent on the expression of TrkB receptor in the NAc.

Progressive increases in BDNF expression have been associated with enhanced cue-induced reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior, termed incubation of drug craving (Neisewander et al., 2000; Grimm et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2004b). For example, rats receiving intra-VTA BDNF infusion after the last episode of cocaine self-administration exhibited significant enhancement of cue-induced reinstatement for up to 30 days (Table 2; Lu et al., 2004a). Of particular note, this effect of VTA BDNF on cue-induced reinstatement is ERK activity-dependent, as it is blocked by U0126, an inhibitor of MEK, the upstream kinase that phosphorylates ERK. While the intracellular ERK signaling pathway is activated by many neurotransmitter and trophic systems, these data suggest that the neuroplasticity induced in the mesolimbic dopaminergic system by BDNF and psychomotor stimulants may converge on ERK signaling pathways in the VTA. Given the importance of ERK signaling for learning- and drug-induced neuroplasticity (Lu et al., 2006; Girault et al., 2007), as well as sensitization to drugs of abuse (Valjent et al., 2004; Valjent et al., 2006; Marin et al., 2009; Kim et al., 2011), it is possible that the BDNF-TrkB-pERK signaling cascade (Figure 1) is one of the primary signaling pathways mediating drug-induced neuroplasticity in the mesolimbic circuit.

VTA BDNF and stress-induced vulnerability to drugs of abuse

The effects of many drugs of abuse are enhanced by a variety of stressors (Antelman et al., 1980; Robinson et al., 1985; Miczek et al., 1999; Covington and Miczek, 2001; Cleck and Blendy, 2008), and such stress-induced augmentation is defined as “stress-induced cross-sensitization” (Table 1). Among the various laboratory stress models, intermittent social defeat stress in rats has gained prominence in cross-sensitization studies for several reasons. Social aggression and conflict in rats reflect a critical facet of natural behavior that has high face validity in replicating the human response to social defeat and changes in social status. Moreover, rats do not habituate to repeated episodes of intermittent social defeat, due to its uncontrollability and unpredictability. As such, the intermittent model of social defeat stress serves as a biologically relevant way to study stress-induced vulnerability to drugs of abuse. Similar to the persistence of sensitization induced by repeated, intermittent drug exposure (Paulson et al., 1991), intermittent social defeat stress induces long-lasting cross-sensitization to amphetamine that can be observed even two months after the last episode to defeat (Nikulina et al., 2004).

It is well known that stressful experiences increase dopamine transmission in VTA projection areas (Kalivas and Duffy, 1989; Tidey and Miczek, 1996). Our own experiments have shown that BDNF protein and mRNA levels increase significantly in the VTA after a prolonged period of abstinence from stress, but not immediately after the last episode of social defeat stress (Fanous et al., 2010). This dynamic temporal pattern of VTA BDNF expression following intermittent social defeat stress corresponds to the onset of cross-sensitization and may be important to the persistent behavioral alterations that present after social defeat stress. Moreover, different temporal patterns of social defeat stress produce differential BDNF expression and behavioral responses to drugs of abuse (Table 1). For example, intermittent social defeat stress induces cross-sensitization to psychostimulants and facilitates acquisition of drug taking, both of which are associated with increased VTA BDNF expression (Covington and Miczek, 2001; Miczek et al., 2011; Nikulina et al., 2012). In contrast, continuous social defeat stress in rats (continuous subordination for 5 weeks) reduces VTA BDNF expression and is associated with psychostimulant tolerance and blunted acquisition of drug self-administration (Miczek et al., 2011). Thus, the social defeat procedure determines whether VTA BDNF expression will increase or decrease, and may subsequently direct behavioral output toward either psychostimulant sensitization (intermittent defeat stress) or depression/anhedonia (continuous defeat stress).

Several reports provide evidence that psychostimulants affect the function of opioid receptors, specifically increased VTA mu-opioid receptor (MOR) mRNA has been associated with the expression of amphetamine sensitization (Magendzo and Bustos, 2003; Trigo et al., 2010). Additionally, increased VTA MOR mRNA is present as little as 30 minutes after acute social defeat stress (Nikulina et al., 1999), while repeated episodes of social defeat stress increases VTA MOR mRNA expression by 20–70%, and this increase persists up to 14 days after the last episode (Nikulina et al., 2008). This upregulation of MORs is essential, since genetic MOR knockout mice do not exhibit social defeat stress-induced social avoidance (Komatsu et al., 2011), and MOR knockdown in rat VTA prevents cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Johnston et al., 2011). In the VTA, MORs are expressed by GABA neurons (Sesack and Pickel, 1995; Garzon and Pickel, 2002), which are hyperpolarized in response to MOR stimulation, and act to disinhibit VTA dopamine transmission (Johnson and North, 1992; Bergevin et al., 2002; Vargas-Perez et al., 2009). In fact, enhancement of VTA MOR expression (Nikulina et al., 2005; Nikulina et al., 2008) coincides with social defeat stress-induced cross-sensitization to psychomotor stimulants (Covington and Miczek, 2001; Nikulina et al., 2004; Nikulina et al., 2012), suggesting that GABAergic MORs in the VTA may mediate stress-induced psychomotor sensitization (Figure 2). In support of this, MOR knockout mice exhibit enhanced VTA GABA transmission and reduced cocaine self-administration (Mathon et al., 2005), while systemic MOR antagonism blocks the expression of amphetamine sensitization (Magendzo and Bustos, 2003). Recent data from our laboratory reveal that lentivirus-mediated knockdown of VTA MORs prevents social defeat stress-induced cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Johnston et al., 2011) and also blocks induction of VTA BDNF expression (Johnston et al., 2012). Taken together, the results of these studies suggest that stress increases VTA BDNF expression as a consequence of increased MOR upregulation on VTA GABA neurons (Figure 2), and implicates VTA MORs as a long-term mediator of stress-induced drug sensitization.

At the time point at which intermittent social defeat stress induces amphetamine cross-sensitization, neural activation is present in the mesocorticolimbic circuit, as evidenced by increased Fos-like protein response (Nikulina et al., 2004). In particular, drug-naïve rats with a history of intermittent social defeat stress exhibit markedly greater Fos-like protein expression in the VTA in response to amphetamine challenge. Furthermore, co-expression of BDNF with ΔFosB, a long-lasting isoform of Fos, increased significantly in the PFC, NAc, and medial amygdala 10 days after the last episode of intermittent social defeat stress (Nikulina et al., 2012). In the infralimbic cortex, stress exposure increased the expression of ΔFosB selectively in neurons that project to the VTA, which suggests that stress-induced neural activation is limited to PFC projections between the infralimbic cortex and the VTA (Nikulina et al., 2012). By altering dopamine transmission, increased VTA BDNF expression may prime neurons in VTA projection areas, thereby facilitating persistent ΔFosB expression. Thus, enhanced BDNF-ΔFosB colocalization in regions of the mesocorticolimbic circuit may serve as anatomical substrates that mediate intermittent social defeat stress-induced psychostimulant cross-sensitization. The putative molecular mechanism underlying colocalization of BDNF with ΔFosB after intermittent social defeat stress is not currently known and provides an intriguing subject for future studies.

In order to determine whether an increase of VTA BDNF is sufficient to facilitate stress-induced psychostimulant cross-sensitization, we overexpressed BDNF in the VTA and assessed cross-sensitization after a single episode of social defeat stress (Table 2; Wang et al., 2013b), which normally induces mild and short-lived cross-sensitization (de Jong et al., 2005). Instead, we observed that VTA BDNF overexpression induces long-lasting amphetamine cross-sensitization, up to 14 days later. A low dose of amphetamine in rats exposed to a single episode of social defeat stress with VTA BDNF overexpression produced significant sensitization compared to both viral GFP-control and handled rats with VTA BDNF overexpression. Moreover, overexpression of VTA BDNF alone was sufficient to induce ΔFosB expression in the NAc and PFC (Wang et al., 2013b). These data suggest that elevated VTA BDNF itself functions to increase neuronal activation in VTA projection areas, wherein ΔFosB may represent a stable molecular marker for the addictive state (Nestler, 2008), Thus, by facilitating stress-induced neuroplasticity, VTA BDNF overexpression is capable of inducing persistent cross-sensitization in response to even a single episode of social defeat stress.

The NAc is necessary for the expression of drug sensitization and is one of the main brain regions implicated in the reinforcing effects of drugs of abuse. Moreover, BDNF signaling in the NAc has been associated with susceptibility to the effects of social defeat stress (Krishnan et al., 2007), and intact NAc TrkB signaling is necessary for the behavioral effects of both acute (Crooks et al., 2010) and chronic cocaine administration (Bahi et al., 2008; Graham et al., 2009). Furthermore, knockdown of NAc TrkB receptors prior to intermittent social defeat stress exposure prevents cross-sensitization to amphetamine (Wang et al., 2014). Previous work has found that some of the key neurochemical changes induced by social defeat stress result in accumulation of NAc ΔFosB (Perrotti et al., 2004; Nikulina et al., 2008), increased VTA expression of the GluA1 subunit of the AMPA receptor (Covington et al., 2008), and enhanced VTA BDNF expression (Fanous et al., 2010), each of which is blocked by knockdown of NAc TrkB receptors (Wang et al., 2014). As such, it is likely that mesolimbic BDNF-TrkB signaling is necessary for the development of stress-induced neuroplasticity, while interrupting BDNF-TrkB signaling along the mesolimbic pathway can prevent the long-term neurochemical and behavioral changes induced by social defeat stress.

Overexpression of BDNF in the NAc is known to enhance cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization, conditioned place preference, and reinstatement in rats (Bahi et al., 2008). Consistent with this, overexpression of VTA BDNF alone facilitates acquisition of cocaine self-administration, and leads to escalated drug intake during a 12 hour binge session when combined with social defeat stress (Table 2; Wang et al., 2013a). Of particular note, VTA BDNF expression is positively correlated with drug intake during the 12 hour binge, suggesting that VTA BDNF promotes compulsive drug taking (Wang et al., 2013a). These results imply that elevated VTA BDNF may act as a risk factor that engenders increased vulnerability to cocaine abuse, particularly in individuals with a history of stress.

Effect of other neurotrophins and trophic factors in the VTA

In addition to BDNF, other members of the neurotrophin family have been found to act in the VTA to influence responses to drugs of abuse, stress and mood. While ventral midbrain dopamine neurons express mRNA for BDNF and TrkB, they also express NT-3 and TrkC (Hyman et al., 1994; Seroogy et al., 1994; Numan and Seroogy, 1999; Numan et al., 2005). Neurotrophins 4/5 (NT-4/5) are not found at high concentrations in the central nervous system (Timmusk et al., 1993), although NT-4/5 has a high affinity for, and can bind to the TrkB receptor (Figure 1). However, while both NT-4/5 and BDNF increase the dopamine content and tyrosine hydroxylase expression of VTA neurons, NT-4/5 stimulation produces significantly greater tyrosine hydroxylase expression, whereas BDNF also significantly increases dopamine uptake capacity (Hyman et al., 1994). In contrast, NGF has no obvious action on dopamine neurons and is expressed at very low levels in the VTA, being favored instead in brain regions receiving projections from basal forebrain cholinergic neurons (see review of Korsching et al., 1986; Sofroniew et al., 2001).

Acute cocaine transiently increases the expression of NT-3 in the VTA (Pierce et al., 1999), while blockade of VTA NT-3 activity enhances repeated cocaine-induced locomotor sensitization (Freeman and Pierce, 2002). In contrast, daily intra-VTA infusion of NT-3 for 3 days failed to induce locomotor sensitization in response to cocaine until 15 days later (Pierce et al., 1999). These data suggest that there is a specific temporal component to the role of NT-3 in cocaine-induced sensitization. VTA infusion of either NT-3 or NT-4 is sufficient to prevent both morphine- and cocaine-induced increases in VTA tyrosine hydroxylase expression (Berhow et al., 1995). During withdrawal from morphine, NT-3 mRNA and TrkC expression increased in the locus coeruleus. However no differences were found in the VTA (Numan et al., 1998), suggesting that VTA NT-3 signaling does not play a critical role in morphine withdrawal. In contrast, VTA infusion of NGF had no effect on tyrosine hydroxylase when given alone or concurrently with morphine treatment (Berhow et al., 1995), which is consistent with a lack of specificity for dopamine neurons. However, NGF has been implicated in the effects of stress (see review by Cirulli and Alleva, 2009) and in hippocampal studies of depression (McGeary et al., 2011, Banerjee et al., 2013).

Several other neurotrophic factors have been shown to drive VTA-mediated behaviors. Members of the fibroblast growth factor (FGF) and glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) families have been implicated in the effects of drugs of abuse in the VTA. For example, intermittent injections of amphetamine cause persistent increase of basic FGF (bFGF) expression that is associated with astrocytes rather than dopamine neurons in both the VTA and the substantia nigra pars compacta (Flores et al., 1998). Moreover, the amphetamine-induced increase of bFGF is blocked by co-administration of a glutamate antagonist, suggesting that the sustained expression of astrocytic bFGF may protect dopamine neurons from the negative effects of psychostimulant-induced glutamate release (Flores et al., 1998). Furthermore, infusion of a bFGF-neutralizing antibody into the VTA prior to repeated amphetamine completely prevents the development of amphetamine sensitization (Flores et al., 2000). These data suggest that bFGF mediates long-term responses to psychostimulant drugs via glutamatergic-dopaminergic interactions, rather than by acting directly on VTA dopamine neurons. Similarly, FGF-1 in the VTA appears to be necessary for the induction, but not the expression of morphine sensitization (Flores et al., 2010). Infusion of FGF-1 into the VTA facilitates the locomotor activating effects of morphine, while VTA infusion of anti-FGF-1 blocks morphine sensitization; neither infusion into the substantia nigra had any effect (Flores et al., 2010).

The dorsal and ventral striatum are the primary sources of GDNF supply to the midbrain, where receptors for GDNF are abundantly expressed in the VTA and substantia nigra. Like BDNF, GDNF is known to provide trophic support for midbrain dopamine neurons and has been widely studied in relation to drugs of abuse (see review of Ghitza et al., 2010). Infusion of GDNF into the VTA prevents or reverses cocaine- and morphine-induced expression of tyrosine hydroxylase and NMDAR1 (Messer et al., 2000). Moreover, VTA infusion of GDNF is sufficient to reduce the magnitude of conditioned place preference for cocaine, while intra-VTA infusion of anti-GDNF enhances sensitivity to the rewarding effects of cocaine (Messer et al., 2000). Overexpression or intra-VTA infusion of GDNF during withdrawal from cocaine self-administration increases cue-induced cocaine seeking, an effect that can be reversed by blocking VTA ERK signaling (Lu et al., 2009). Heroin self-administration and withdrawal regulate GDNF mRNA expression in the NAc and VTA in a time-dependent manner, whereas infusion of GDNF to the NAc, but not to the VTA, potentiates cue-induced heroin seeking (Airavaara et al., 2011). Despite this, infusion of anti-GDNF into the NAc or VTA had no effect on incubation of heroin craving. Taken together, these results suggest that the effects of GDNF in the mesolimbic pathway differ between psychostimulants and opiates, and that the role of GDNF is more complicated in abuse of opiates than psychostimulants.

Concluding remarks

This review attempts to summarize evidence suggesting that neurotrophins expressed in the VTA are sensitive and responsive to various environmental stimuli, such as stress and drug administration, and are contingent on neuronal circuit activity. For example, increased BDNF expression in the VTA and TrkB signaling in mesolimbic terminal regions are associated with the development of a depressive-like phenotype, facilitation of psychostimulant-induced behavior, and altered social behavior. That BDNF, which is critical for the survival and function of VTA dopamine neurons, may be involved both in reward responding and in depressive symptoms is an apparent paradox. Anhedonia during depression-like behavior, as well as the euphoric experience induced by psychostimulants, are both mediated by the mesocorticolimbic circuit. The dichotomy of BDNF action might be due in part to the respective cellular actions of pro- and mature BDNF, which activate different receptors and intracellular pathways (see Figure 1 and Introduction). For example, proBDNF and mature BDNF have opposite effects on long-term potentiation and long-term depression in brain stress and reward systems (see review by Martinowich et al., 2007).

These contradictory effects may also be explained in part by recent studies revealing that VTA dopamine neurons are more heterogeneous than previously thought (see review by Roeper, 2013). The functional diversity of VTA dopamine neurons is related to their distinct projection targets and differences in afferent supply. Rewarding and aversive stimuli differentially affect subsets of afferent projections to VTA dopamine neurons (Ikemoto, 2007; Lammel et al., 2011; Lammel et al., 2012). The activity of VTA dopamine neurons projecting to the NAc is required for susceptibility to stress-induced depressive symptoms, whereas activation of PFC neurons that project to the VTA is associated with resiliency (Chaudhury et al, 2013).

The impact of VTA BDNF on the effect of morphine appears to differ depending on drug history, which is known to involve dopamine-dependent and -independent VTA signaling (Vargas-Perez et al, 2009). The tVTA has abundant GABAergic projections to the rostral VTA that regulate the activity of dopamine cells (Jalabert et al., 2011; Bourdy and Barrot, 2012; Barrot et al., 2012) to modulate morphine’s effect. As discussed throughout the review, the involvement of various intracellular signaling pathways allows for the precise regulation of distinct behavioral functions. Future research is needed to determine whether BDNF signaling in the tVTA is involved in the effect of acute or chronic morphine actions, and whether its effects depend on drug history.

The limitation of most studies is that few have assessed the role of VTA BDNF signaling in a cell type-(GABA, glutamate, or dopamine) or projection-specific manner. Levels of BDNF and its associated signaling proteins have been mostly examined in homogenates from the entire VTA region or in only its rostral portion, which has resulted in various differences across studies. Evidence of cell type specific effects of BDNF signaling have been demonstrated in various neuronal populations of the PFC. After withdrawal from repeated cocaine, excitatory glutamatergic synapses onto VTA dopamine neurons are sensitized, and this effect is dependent on endogenous BDNF-TrkB signaling (Pu et al, 2006). The critical role of BDNF transcription in the PFC has been identified in GABAergic interneurons expressing parvalbumin, a subtype implicated in executive function and schizophrenia (Sakata et al, 2009).

An accumulating body of research has shown that VTA BDNF is particularly responsive to social stress exposures. A recent review showed that BDNF and glucocorticoid activity have reciprocal modulatory influences (Jeanneteau and Chao, 2013), depending on the intensity of the stressor. The interplay between BDNF and glucocorticoid after a stress episode was observed mainly in hippocampal tissue. However, VTA BDNF induction after the presentation of social stress depends on the strength and duration of stress exposure. Moreover, when VTA BDNF is overexpressed, the time course of social stress and psychostimulant action is expanded as a consequence of dopamine neuronal activation. The caudal portion of the VTA has been implicated in aversive behavior, and social stress is one factor known to induce social aversion as well as sensitized response to psychostimulants. It remains to be determined whether BDNF signaling in the caudal VTA is involved in the effects of stress and drugs of abuse. Future research of intracellular BDNF signaling in different parts of the VTA could provide potential strategies for the development of novel approaches to mitigate various psychopathologies.

Highlights.

VTA BDNF expression increases after psychostimulant exposure

Effect of BDNF is dependent on history of opiate exposure

Chronic social defeat stress increases VTA BDNF that associated with depressive behavior

Acknowledgements

Support contributed by USPHS award DA026451.

Abbreviations

- BDNF

brain-derived neurotrophic factor

- ERK

extracellular signal regulated kinase

- FGF

fibroblast growth factor

- GDNF

glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- MARK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MOR

mu-opioid receptor

- NT

neurotrophin

- NAc

nucleus accumbens

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- PLC-γ

phospholipase C-γ

- TrkB

tropomyosin-regulated kinase B

- tVTA

tail of ventral tegmental area

- PFC

prefrontal cortex

- VTA

ventral tegmental area

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Airavaara M, Pickens CL, Stern AL, Wihbey KA, Harvey BK, Bossert JM, Liu QR, Hoffer BJ, Shaham Y. Endogenous GDNF in ventral tegmental area and nucleus accumbens does not play a role in the incubation of heroin craving. Addict Biol. 2011;16:261–272. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00281.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar CA, Boylan CB, Jackson C, Hershenson S, Miller J, Wiegand SJ, Lindsay RM, Hyman C. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor augments rotational behavior and nigrostriatal dopamine turnover in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:11347–11351. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altar CA, Cai N, Bliven T, Juhasz M, Conner JM, Acheson AL, Lindsay RM, Wiegand SJ. Anterograde transport of brain-derived neurotrophic factor and its role in the brain. Nature. 1997;389:856–860. doi: 10.1038/39885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antelman SM, Eichler AJ, Black CA, Kocan D. Interchangeability of stress and amphetamine in sensitization. Science. 1980;207:329–331. doi: 10.1126/science.7188649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babbini M, Gaiardi M, Bartoletti M. Persistence of chronic morphine effects upon activity in rats 8 months after ceasing the treatment. Neuropharmacology. 1975;14:611–614. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(75)90129-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahi A, Boyer F, Chandrasekar V, Dreyer JL. Role of accumbens BDNF and TrkB in cocaine-induced psychomotor sensitization, conditioned-place preference, and reinstatement in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2008;199:169–182. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Li X, Clay M, Lindstrom T, Skolnick P. Intra- and interstrain differences in models of "behavioral despair". Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2001;70:187–192. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00599-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R, Ghosh AK, Ghosh B, Mondal AC. Role of NGF/TrkA signaling milieu in depressogenic induction of rat brain. Al Ameen J Med Sci. 2013;6:355–363. [Google Scholar]

- Barrot M, Sesack SR, Georges F, Pistis M, Hong S, Jhou TC. Braking dopamine systems: a new GABA master structure for mesolimbic and nigrostriatal functions. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14094–14101. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3370-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitner-Johnson D, Nestler EJ. Morphine and cocaine exert common chronic actions on tyrosine hydroxylase in dopaminergic brain reward regions. J Neurochem. 1991;57:344–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb02133.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergevin A, Girardot D, Bourque MJ, Trudeau LE. Presynaptic mu-opioid receptors regulate a late step of the secretory process in rat ventral tegmental area GABAergic neurons. Neuropharmacology. 2002;42:1065–1078. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(02)00061-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhow MT, Hiroi N, Nestler EJ. Regulation of ERK (extracellular signal regulated kinase), part of the neurotrophin signal transduction cascade, in the rat mesolimbic dopamine system by chronic exposure to morphine or cocaine. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:4707–4715. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-15-04707.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berhow MT, Russell DS, Terwilliger RZ, Beitner-Johnson D, Self DW, Lindsay RM, Nestler EJ. Influence of neurotrophic factors on morphine- and cocaine-induced biochemical changes in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Neuroscience. 1995;68:969–979. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(95)00207-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berton O, McClung CA, Dileone RJ, Krishnan V, Renthal W, Russo SJ, Graham D, Tsankova NM, Bolanos CA, Rios M, Monteggia LM, Self DW, Nestler EJ. Essential role of BDNF in the mesolimbic dopamine pathway in social defeat stress. Science. 2006;311:864–868. doi: 10.1126/science.1120972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard RJ, McKittrick CR, Blanchard DC. Animal models of social stress: effects on behavior and brain neurochemical systems. Physiol Behav. 2001;73:261–271. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(01)00449-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard RJ, Wall PM, Blanchard DC. Problems in the study of rodent aggression. Horm Behav. 2003;44:161–170. doi: 10.1016/s0018-506x(03)00127-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blochl A, Sirrenberg C. Neurotrophins stimulate the release of dopamine from rat mesencephalic neurons via Trk and p75Lntr receptors. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1996;271:21100–21107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.35.21100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolanos CA, Perrotti LI, Edwards S, Eisch AJ, Barrot M, Olson VG, Russell DS, Neve RL, Nestler EJ. Phospholipase Cgamma in distinct regions of the ventral tegmental area differentially modulates mood-related behaviors. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2003;23:7569–7576. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-20-07569.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdy R, Barrot M. A new control center for dopaminergic systems: pulling the VTA by the tail. Trends in neurosciences. 2012;35:681–690. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2012.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JM, Hanson GR, Fleckenstein AE. Regulation of the vesicular monoamine transporter-2: a novel mechanism for cocaine and other psychostimulants. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;296:762–767. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brünig I, Penschuck S, Berninger B, Benson J, Fritschy J-M. BDNF reduces miniature inhibitory postsynaptic currents by rapid downregulation of GABAA receptor surface expression. European Journal of Neuroscience. 2001;13:1320–1328. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabib S, Puglisi-Allegra S. Stress, depression and the mesolimbic dopamine system. Psychopharmacology. 1996;128:331–342. doi: 10.1007/s002130050142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cador M, Bjijou Y, Cailhol S, Stinus L. D-amphetamine-induced behavioral sensitization: implication of a glutamatergic medial prefrontal cortex-ventral tegmental area innervation. Neuroscience. 1999;94:705–721. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00361-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese F, Molteni R, Racagni G, Riva MA. Neuronal plasticity: a link between stress and mood disorders. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34(Suppl 1):S208–S216. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Nestler EJ, Neve RL. Herpes simplex virus-mediated gene transfer as a tool for neuropsychiatric research. Crit Rev Neurobiol. 2000;14:47–67. doi: 10.1080/08913810008443546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll ME, Meisch RA. Determinants of increased drug self-administration due to food deprivation. Psychopharmacology. 1981;74:197–200. doi: 10.1007/BF00427092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chao MV. Neurotrophins and their receptors: a convergence point for many signalling pathways. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4:299–309. doi: 10.1038/nrn1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhury D, Walsh JJ, Friedman AK, Juarez B, Ku SM, Koo JW, Ferguson D, Tsai HC, Pomeranz L, Christoffel DJ, Nectow AR, Ekstrand M, Domingos A, Mazei-Robison MS, Mouzon E, Lobo MK, Neve RL, Friedman JM, Russo SJ, Deisseroth K, Nestler EJ, Han MH. Rapid regulation of depression-related behaviours by control of midbrain dopamine neurons. Nature. 2013;493:532–536. doi: 10.1038/nature11713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiodo LA, Antelman SM. Electroconvulsive shock: progressive dopamine autoreceptor subsensitivity independent of repeated treatment. Science. 1980;210:799–801. doi: 10.1126/science.6254148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie MJ. Cellular neuroadaptations to chronic opioids: tolerance, withdrawal and addiction. Br J Pharmacol. 2008;154:384–396. doi: 10.1038/bjp.2008.100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu NN, Zuo YF, Meng L, Lee DY, Han JS, Cui CL. Peripheral electrical stimulation reversed the cell size reduction and increased BDNF level in the ventral tegmental area in chronic morphine-treated rats. Brain research. 2007;1182:90–98. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.08.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirulli F, Alleva E. The NGF saga: from animal models of psychosocial stress to stress-related psychopathology. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2009;30:379–395. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleck JN, Blendy JA. Making a bad thing worse: adverse effects of stress on drug addiction. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:454–461. doi: 10.1172/JCI33946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colussi-Mas J, Geisler S, Zimmer L, Zahm DS, Berod A. Activation of afferents to the ventral tegmental area in response to acute amphetamine: a double-labelling study. The European journal of neuroscience. 2007;26:1011–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2007.05738.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conner JM, Lauterborn JC, Yan Q, Gall CM, Varon S. Distribution of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) protein and mRNA in the normal adult rat CNS: evidence for anterograde axonal transport. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1997;17:2295–2313. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-07-02295.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeira J, Rios M. Weighing in the role of BDNF in the central control of eating behavior. Mol Neurobiol. 2011;44:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s12035-011-8212-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordeira JW, Frank L, Sena-Esteves M, Pothos EN, Rios M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates hedonic feeding by acting on the mesolimbic dopamine system. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:2533–2541. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5768-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, 3rd, Miczek KA. Repeated social-defeat stress, cocaine or morphine. Effects on behavioral sensitization and intravenous cocaine self-administration "binges". Psychopharmacology. 2001;158:388–398. doi: 10.1007/s002130100858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covington HE, 3rd, Tropea TF, Rajadhyaksha AM, Kosofsky BE, Miczek KA. NMDA receptors in the rat VTA: a critical site for social stress to intensify cocaine taking. Psychopharmacology. 2008;197:203–216. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-1024-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crooks KR, Kleven DT, Rodriguiz RM, Wetsel WC, McNamara JO. TrkB signaling is required for behavioral sensitization and conditioned place preference induced by a single injection of cocaine. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:1067–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong JG, Wasilewski M, van der Vegt BJ, Buwalda B, Koolhaas JM. A single social defeat induces short-lasting behavioral sensitization to amphetamine. Physiol Behav. 2005;83:805–811. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty GG, Jr, Ellinwood EH., Jr Chronic D-amphetamine in nucleus accumbens: lack of tolerance or reverse tolerance of locomotor activity. Life Sci. 1981;28:2295–2298. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(81)90582-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Monteggia LM. A neurotrophic model for stress-related mood disorders. Biological psychiatry. 2006;59:1116–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duman RS, Voleti B. Signaling pathways underlying the pathophysiology and treatment of depression: novel mechanisms for rapid-acting agents. Trends in neurosciences. 2012;35:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2011.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]