Abstract

• Background Plant evolutionary theory has been greatly enriched by studies on crop species. Over the last century, important information has been generated on many aspects of population biology, speciation and polyploid genetics.

• Scope Searches for quantitative trait loci (QTL) in crop species have uncovered numerous blocks of genes that have dramatic effects on adaptation, particularly during the domestication process. Many of these QTL have epistatic and pleiotropic effects making rapid evolutionary change possible. Most of the pioneering work on the molecular basis of self-incompatibility has been conducted on crop species, along with the sequencing of the phytopathogenic resistance genes (R genes) responsible for the ‘gene-to-gene’ relations of coevolution observed in host–pathogen relationships. Some of the better examples of co-adaptation and early acting inbreeding depression have also been elucidated in crops. Crop–wild progenitor interactions have provided rich opportunites to study the evolution of novel adaptations subsequent to hybridization. Most crop/wild F1 hybrids have reduced fitness, but in some instances the crop relatives have acquired genes that make them more efficient weeds through crop mimicry. Studies on autopolyploid alfalfa and potato have uncovered the means by which polyploid gametes are formed and have led to hypotheses about how multiallelic interactions are associated with fitness and self-fertility. Research on the cole crops and wheat has discovered that newly formed polyploids can undergo dramatic genome rearrangements that could lead to rapid evolutionary change.

• Conclusions Many more important evolutionary discoveries are on the horizon, now that the whole genome sequence is available of the two major subspecies of rice Oryza sativa ssp. japonica and O. sativa ssp. indica. The rice sequence data can be used to study the origin of genes and gene families, track rates of sequence divergence over time, and provide hints about how genes evolve and generate products with novel biological properties. The rice sequence data has already been mined to show that transposable elements often carry fragments of cellular genes. This type of genome shuffling could play a role in creating novel, reorganized genes with new adaptive properties.

Keywords: Crop domestication, self-incompatibility, R genes, hybridization, genome evolution, polyploidy

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this paper is to describe the contributions of crop research to evolutionary biology, particularly in the areas of population genetics, speciation and polyploidy. Population genetic studies are reviewed that deal with the underlying mechanisms regulating quantitative variation in populations, the cohesiveness of the genome (co-adaptation), sexual incompatibility systems and host–pathogen evolution. Studies of speciation are described that concern what constitutes a species, the role of hybridization and introgression in evolutionary change, and the degree of genome evolution after speciation. Polyploid studies are outlined that provide information on the adaptive benefit of polyploidy, the nature of self-infertility in autopolyploids, and the capacity of polyploids to evolve. The recent sequencing of two subspecies of rice is also discussed in the context of evolutionary biology.

POPULATION GENETICS

Quantitative genetics

Knowledge about the underlying genetics is critical to understanding how quantitative traits evolve over time. In the early 1900s, crop geneticists first began to wonder whether more continuous traits such as plant height and seed weight were inherited according to Mendelian laws. Johannsen (1903) showed that such variation was indeed influenced by genes, but that the environment also played a role—he was the first to distinguish between genotype and phenotype. Yule (1906) hypothesized that quantitative variation could be caused by several genes having small effects, and Nileson-Ehle (1909) and East (1916) confirmed this suspicion using wheat and tobacco. Several statistical techniques were then developed to partition the total variability within a population into it's various genetic, environmental and interaction components (for reviews, see Mather and Jenks, 1977; Fehr, 1987; Falconer and Mackay, 1996).

Most recently, molecular markers have provided a means to dissect the genetic basis of the complex traits that are regulated by many individual quantitative trait loci (QTL) (Tanksley, 1993; Patterson et al., 1998). Plant breeders now regularly employ QTL analyses to tag the key genes regulating agronomic traits, and evolutionary biologists have found the technique to be valuable in identifying the genetics of important adaptive traits and reconstructing the speciation process (Rieseberg, 2000).

A considerable amount of work has been conducted to identify those QTL associated with the process of crop domestication (Hancock, 2004). One of the most striking findings in these studies is that a few major genes often influence a large amount of the genetic variability even though a high number of genes may be affected by artificial selection during domestication (Wright et al., 2005). This means that substantial evolutionary change can initially occur with the selection of only a few genes. Koinange et al. (1996) found major genes in dry beans associated with mode of seed dispersal, seed dormancy, growth habit, gigantism, earliness, photoperiod sensitivity and harvest index (Fig. 1). Doebley and his colleagues isolated three key QTL in maize that regulate glume toughness, sex expression and the number and length of internodes in both lateral branches and inflorescences (Doebley et al., 1990). One of these, teosinte glume architecture 1, probably played a particularly important role in the appearance of maize 8000 years ago, as it disrupts reproductive development in such a way that the kernels are naked, rather than encased in tough glumes (Dorweiler et al., 1993; Lukens and Doebley, 1999; Wang et al., 2005). Major QTL for other traits associated with the domestication process have also been described in pearl millet (Poncet et al., 1998), sorghum (Paterson et al., 1998), tomato (Grandillo and Tanksley, 1996; Grandillo et al., 1999) and rice (Xiong et al., 1999; Bres-Patry et al., 2001). Xiao et al. (1998) located two O. rufipogan alleles on two chromosomes that were associated with almost 20 % increases each on grain yield per plant.

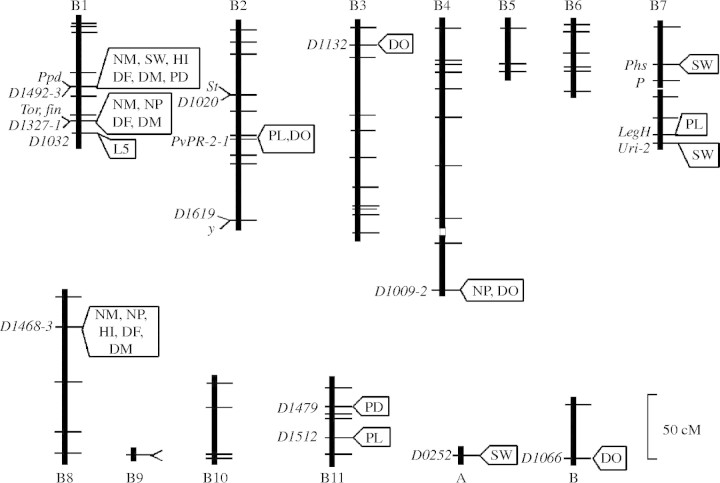

Fig. 1.

Linkage map location of known genes and marker loci controlling the domestication syndrome in common bean. Symbols for the genes: fin, determinacy; P, anthocyanin pigmentation; Ppd, photoperiod-induced delay in flowering; St, pod string; y, yellow. Symbols for marker loci: DF, days to flowering; DM, days to maturity; DO, seed dormancy; HI, harvest index; L5, length of fifth internode; NM, number of nodes on main stem; PL, pod length; NP, number of pods per plant; PD, photoperiod induced delay in flowering; SW, seed weight (Koinange et al., 1996).

Two QTLs for domestication traits have even been cloned; fw2.2 which has dramatic effects on fruit weight in tomato (Frary et al., 2000) and Hd1 which regulates photosensitivity in rice (Yano et al., 2000). Interestingly, the fruit weight variation associated with fw2.2 has been linked to nucleotide changes in the promoter region of the gene rather than its structural components (Liu et al., 2003), and molecular-clock-based estimates indicate that the large fruit allele arose long before the tomato was domesticated (Nesbitt and Tanksley, 2002).

Of considerable interest to evolutionary biologists is the level of genic interaction that underlies adaptive change. Classical statistical studies of quantitative variation have uncovered considerable evidence of epistasis (Falconer and Mackay, 1996), but the documentation of inter-genic interactions in QTL mapping studies has proved to be more elusive (Tanksley, 1993; Paterson, 1995; Kim and Rieseberg, 2001; Westerbergh and Doebley, 2004). A large part of the difficulty in identifying epistatic interactions with molecular markers deals with the statistical power represented by smaller population sizes, and limitations in the analysis of variance technique itself (Wade, 1992; Doebley et al., 1995). Mixed linear model approaches have been suggested to improve the detection of digenic epistasis and QTL × environment interactions (Wang et al., 1999).

In spite of the statistical limitations, several studies on rice have clearly documented QTL with epistatic effects. Yamamoto et al. (2000) found a significant interaction between two QTL (Hd2 and Hd6) involved in photoperiod sensitivity. Yu et al. (1997) identified 32 QTL associated with four yield traits, and found that almost all of them significantly interact with at least one other QTL. Mei et al. (2003) even found that a greater proportion of the total phenotypic variation found in rice was due to epistatic interactions than additive ones.

Doebley's group has discovered a significant epistatic interaction in maize between a QTL on chromosome arm 1L (QTL-1L) and another on chromosome arm 3L (QTL-3L) that both influence the number and length of the internodes in both the primary lateral branch and inflorescence (Doebley et al., 1995; Lukens and Doebley, 1999). Alleles at these loci derived from either maize or teosinte had the strongest phenotypic effect in their own species background, further signalling the complexity of genomic interactions in Zea mays. Numerous QTL studies of crop species have uncovered genes with pleiotropic effects, where they affect a number of traits simultaneously. As a result, their selection would make large-scale phenotypic change much more rapid than if the traits were evolving separately.

The fin gene in dry beans conditions the earliness of flowering, and has significant effects on node number on stems, pod number, and the number of days from flowering to fruiting (Koinange et al., 1996). Several pleiotropic QTL have been identified in Zea including: teosinte glume architecture 1 (tb1), which effects internode lengths, inflorescence sex and structure, teosinte branched 1 (te1), which also effects internode lengths, numbers and inflorescence sex, and suppressor of sessile spikelets1 (sos1), which effects branching in the inflorescence and the presence of single vs. paired spikelets in the ear (Doebley et al., 1995). Allard (1988) identified a number of marker loci for quantitative traits in barley that had significant additive effects on several to many quantitative traits. In one case, a QTL analysis proved that a suspected pleiotropic effect did not exist. Frary et al. (2004) found little overlap in the QTL determining the size and shape of leaflets, sepals and petals of tomato, even though leaves have long been considered antecedent to flowers.

Many of the QTL associated with the domestication syndromes are clustered close together on the same chromosome. Such close associations of genes would reduce the amount of segregation between these adaptively important genes and in a sense ‘fix’ the crop type, again allowing for rapid change. These genic assemblages are very similar to the ‘supergenes’ that have been described in native species (Ford, 1975). Koinange et al. (1996) found the distribution of domestication syndrome genes to be concentrated in three genomic regions, one of which greatly effected growth habit and phenology, the other seed dispersal and dormancy, and a third the size fruit and seed. Doebley et al. (1990) found five of the QTLs that distinguish maize and teosinte in a tight cluster on chromosome 8. These genes regulated: (a) the tendency of the ear to shatter, (b) the percentage of male spikelets in the primary inflorescence; (c) average length of internodes on the primary lateral branch; (d) percentage of cupules lacking the pedicellate spikelet; and (e) the number of cupules in a single rank. Wright et al. (2005) found a number of candidate genes on this chromosome and others that had putative functions in plant growth. Many of the genetic factors controlling domestication-related traits were also concentrated on a few chromosomal blocks in pearl millet (Poncet et al., 1998), tomato (Grandillo and Tanksley, 1996) and rice (Xiang et al., 1999). The linkage relationships of the QTL associated with domestication-related traits have been found to be conserved in eggplant, tomato, pepper and potato (Doganler et al., 2002; Frary et al., 2003). Considerable synteny has also been found between the chromosomal region carrying the major heading-date QTL in perennial ryegrass and the rice region with the Hd3 heading-date locus (Armstead et al., 2004).

Co-adaptation

Most evolutionary biologists consider the genome to be cohesive, with selection operating on the whole phenotype of an individual and not only on the product of single genes. The evolutionary ramification of this genomic complexity is that alleles are selected at two levels: (1) how well they function in the environment, and (2) how well they function together. Hybrids between different populations of the same species are sometimes weak or inviable (Wallace, 1968). Such ‘hybrid breakdowns’ are thought to arise because the gene pools within populations have been selected over time for their harmonious interaction. When individuals are crossed from variant populations, their genes may not be well integrated and therefore produce poorly adapted offspring.

Most of the most graphic examples of hybrid breakdowns have been demonstrated in animals, although a particularly good example of hybrid breakdown has been documented in the bean, Phaseolus vulgaris (Gepts, 1988, 1998). There are large- and small-seeded races from South America and Mexico which when crossed produce high percentages of weak, semi-dwarf progeny. This reduction in hybrid fertility and vigour is associated primarily with two independent loci DL1 and DL2, although many other differences exist in the gene pools of the geographic races, including distinct phaseolin seed proteins, electrophoretic alleles, chloroplast DNA, flowering times and floral structures (Shii et al., 1981; Gepts and Bliss, 1985; Chacón et al., 2005).

Hogenboom (1973, 1975) coined the term ‘incongruity’ to describe the pre-fertilization barriers that sometimes arise between divergent taxa of crop species. He felt that inter-species crosses often fail because one species lacks the genetic information necessary to properly co-ordinate the critical functions of the other through disrupted gene regulation, the absence of a gene, or poor genomic–cytoplasmic interactions. Haghighi and Ascher (1988) provided circumstantial evidence of this phenomenon by showing that the vigour of inter-specific crosses of Phaseolis vulgaris and P. acutifolius can be improved through several rounds of crosses, presumably through selection for the most co-ordinated genes.

Genetic systems influencing outcrossing rates

The breeding system of plants has a strong influence on variation patterns, with largely outcrossed species being much more heterozygous than highly inbred ones. One of the plant systems forcing outcrossing is dioecy where there are separate male (pistillate) and female (staminate) sexes. In most plant species, there are not separate chromosomes that regulate sex as in animals, although there are exceptions. Mapping studies have lead to the conclusion that papaya (Carica papaya) has an incipient sex chromosome that is still in the process of evolving. It contains a primitive Y chromosome with a male-specific region that accounts for 10 % of the chromosome (Liu et al., 2004; Ma et al., 2004). Recombination is severely repressed in this region leading to permanent heterozygosity in females.

Outcrossing is also encouraged by the self-incompatibility systems (SI), gametophytic and sporophytic. In gametophytic systems, pollen germination and tube growth is dependent on the genotype of the parent; while in sporophytic systems, pollen performance is based on the genotype of the male parent (Lewis, 1979; deNettancourt, 2001).

The bulk of the work that has been done on the molecular basis of self-incompatibility has been conducted on crop plants (McCubbin and Kao, 2000; Silva and Goring, 2001; Nasrallah, 2002). There appear to be three major types of SI mechanisms (Kao and Tsukamoto, 2004). In the Brassicaceae (cole crops) with sporophytic incompatibility, self-pollen germination is inhibited through the interaction of a pollen protein (SP11/SCR), a stylar receptor kinase (SKR), a glycoprotein (SLG) and several other proteins. The mechanism of rejection is due to the prevention of pollen grain hydration and germination (Kemp and Doughty, 2003). In the Papaveraceae (poppy) with gametophytic self-incompatibility, self-pollen tube growth is rejected at the stigmatic surface by the interaction of a stigmatic S protein, a pollen S receptor (SBP), a calcium-dependent protein kinase (CDPK) and a glycoprotein. Pollen tube growth is arrested by a cascade of events associated with an increase in cytosolic calcium and a disruption of the cytoskeleton. In the gametophytic Solanaceae (tobacco, tomato, petunia and potato) and Rosaceae (apple, cherry and pear), self-pollen tube growth is inhibited within styles by a pistil-released RNase (S-RNase) that selectively destroys the RNA of self-pollen tubes. Pollen S proteins determine S-RNase stability in self- vs. non-self styles (Sijacic et al., 2004; Ushijima et al., 2004). Gametophytic SI in the Solanaceae, Scrophulariaceae and Rosaceae appear to have a common origin (Igic and Kohn, 2001).

A phenomena called ‘early acting inbreeding depression’ can mimic SI, when selfed embryos abort as deleterious alleles are expressed during seed development or the outcrossed progeny display a hybrid vigour that enables them to out-compete the selfed ones (Weins et al., 1987; Weller and Ornduff, 1989; Seavey and Carter, 1994). This mode of self-infertility has been clearly elucidated in the crop plants alfalfa, blueberries and coffee, which were historically misclassified as self-incompatible due to poor selfed seed set (Busbice, 1968; Crowe, 1971; Krebs and Hancock, 1991). Early acting inbreeding depression differs from SI, in that different genotypes display a range in self-fertility. Significant positive correlations are also found in species with early acting inbreeding depression between self- and out-cross fertility and the percentage of aborted ovules and inbreeding coefficients (Hokanson and Hancock, 2000).

Co-evolution

Several types of co-evolution have been described in the literature about evolution, including mutualism, character displacement and host-pathogen evolution. Some of the best examples of host–pathogen evolution are found in the crop literature, where constant battles are fought to find new sources of resistance to rapidly evolving pest populations (Allard, 1990). For example, dominant alleles have been identified at more than five loci in wheat that confer resistance to the Hessian fly, but alleles exist for each locus in the fly that confer counter resistance (Hatchett and Gallum, 1970). Dozens of examples of ‘gene-for-gene’ relations have been described in pathogen/host systems where there is a gene for susceptibility or resistance in the crop to match each gene for virulence or avirulence in the pathogen (Martin and Ellingboe, 1976; Leath and Pederson, 1986; Hautea et al., 1987; Pederson and Leath, 1988).

Specific genes have been identified in plants that are associated with these ‘gene-for-gene’ relationships. These phytopathogenic resistence genes (R genes) encode proteins that recognize specific pathogen-derived proteins and trigger a cascade of resistance responses leading to cell death (Martin et al., 2003; Nimchuk et al., 2003). A number of R genes have been cloned and sequenced from mainly crop species and arabidopsis. They are found in tandem arrays of multiple copies and display considerable variability due to both point mutations and unequal meiotic recombination (Shamray, 2003; Kruijt et al., 2004; Xiao et al., 2004). Balancing selection is thought to be the main force maintaining high levels of R gene diversity in populations, although frequency-dependent selection and drift also play important roles (Bergelson et al., 2001; Caicedo and Schaal, 2004).

SPECIATION

Nature of species

A topic of continual discussion among evolutionary biologists is how to define a species. Probably the most popular concept is the ‘biological species’ as ‘groups of actually or potentially interbreeding natural populations, which are reproductively isolated from each other’ (Mayr, 1942; Schemske, 2000). While the biological species concept allows for the unambiguous delineation of species, it is still not without problems (Hancock, 2004). Strongly divergent groups of plants often maintain some degree of inter-fertility even though they differ at numerous loci and are effectively evolving on their own. Plants also show great ranges in self-fertility from obligate outcrossing to complete selfing to apomixis (uniparental). In a highly inbred or apomictic group, every individual would be a species according to the biological species concept.

Numerous concepts have been developed which include ecological with reproductive criteria to better define species; however, no single model solves all of the potential problems in trying to define separate evolutionary units. Levin (2000) even suggests that ‘the choice of a species concept has to do, in part, with the perspective that gives one satisfaction’. Harlan and deWet (1972) developed what they called the ‘gene pool system’ to deal with varying levels of inter-fertility between related taxa of crop species and their relatives. They recognized three types of genic assemblages:

primary gene pool (GP-1)—hybridization easy, hybrids generally fertile;

secondary gene pool (GP-2)—hybridization possible, but difficult; hybrids weak with low fertility;

tertiary gene pool (GP-3)—hybrids lethal or completely sterile.

The primary gene pool is directly equivalent to the biological species. The recognition of GP-2 and GP-3 allows other levels of inter-fertility to be incorporated into the overall concept of species. These are related taxa which share a considerable amount of genetic homology with GP-1, but are divergent enough to have greatly reduced inter-fertility. Several agronomically important groups have been described using this system including legumes, wheat and most of the other cereals (Harlan and deWet, 1975; Smartt, 1984).

Hybridization and introgression

Thoughts about the relative importance of hybridization and introgression in plant evolution have switched back and forth over time, but with the advent of molecular markers in the 1980s support has been greatly bolstered (Rieseberg, 1995; Rieseberg et al., 2000). Some of the best examples of introgression have been observed between crop species and their native relatives. Evidence for crop introgression into wild populations of congeners has been provided for 31 species, including alfalfa, barley, beets, cabbages, canola, cotton, carrots, cassava, chili, cocona, common bean, cowpea, finger millet, foxtail millet, hemp, hops, lettuce, maize, oats, pearl millet, pigeon pea, potato, quinoa, radish, raspberry, rice, rye, sorghum, soybean, squash, sunflower, tomato, watermelon and wheat (Ellstrand et al., 1999; Jarvis and Hodgkin, 1999).

Most F1 hybrids of cultivated and wild congeners have reduced fitness in nature and the genes of domesticated plants rarely travel far from narrow hybrid zones. However, some wild plants have acquired crop genes that make them more effective agronomic weeds. In some instances, genes have introgressed into wild plants that allow them to ‘mimic’ the habit of domesticated ones, and thus escape removal in agronomic sites by farmers. The weed may look identical to the crop until seed dispersal, or the weed seeds may be impossible to separate from the agronomic source.

Crop mimicry has been particularly prevalent among the grains (Harlan et al., 1973; Harlan, 1992). A classic example of crop mimicry can be found in sugar beat fields in Europe, where weed introgressants bolt and scatter seeds before crop harvest (Viard et al., 2002). There are weedy bolters which probably resulted from the contamination of seed producers by pollen from wild individuals, and bolters that emerge from the seed bank containing wild/crop introgressants. The bolters carry the dominant B allele which cancels any cold requirement.

Wild/crop hybridizations have also resulted in alterations of the crop itself, when farmers have exploited new, useful genetic combinations (Hancock, 2004). Farmer selection of crop/weed introgressants may have played a particularly important role in the early development of crops, as agriculture spread out of the centres of origin. It is difficult to document the historic introgression of native genes into crops, but Jarvis and Hodgkin (1999) have identified nine examples where today's farmers are selecting crop/wild introgressents.

Hybridization can lead to new adaptions appearing in recipient species, but high amounts of gene flow and hybridization can also lead to extinction (Levin et al., 1996; Buerkle et al., 2000). There can be ‘genetic assimilation’, where the hybrids are fertile, and they replace pure conspecifics of either or both hybridizing taxa, and there can be ‘demographic swamping’, where population growth in a numerically inferior taxa is retarded by the formation of hybrid seed, and population growth falls below the replacement level.

Some of the clearest examples of genetic assimilation and demographic swamping have been observed in interactions between crops and wild relatives. Genetic assimilation is likely occurring on the Galapagos Islands between the native species Gossypium darwinii and the crop, G. hirsutum (Wendel and Percy, 1990). In California, the cultivated radish, Raphanus sativus, and the jointed charlock, R. raphanistrum, have completely merged (Panetsos and Baker, 1967). Hybridization with cultivated rice is thought to have led to the near extinction of the endemic Taiwanese taxon, Oryza rufipogon spp. formosana through genetic assimilation (Kiang et al., 1979). In fact, most populations of native Asian subspecies of O. rufipogon may be endangered through hybridization with the crop (Chang, 1995; Ellstrand et al., 1999).

Genome evolution

Of interest to many evolutionary biologists, is the degree of genetic change associated with speciation. As previously mentioned, molecular markers are increasingly being used to construct genetic maps of species, and these maps have expanded our knowledge of genome structure and evolution. By comparing maps of related species, it is possible to evaluate the kinds of genomic changes that accompany speciation (Reiseberg et al., 1995, 1996).

A large amount of work has been devoted to studying the degree of linkage conservation or ‘genome evolution’ that exists across a number of crop species (Bennetzen, 2000; Paterson et al., 2000), with variable results. In the initial comparative mapping studies conducted with limited genetic markers and progeny populations, gene order appeared highly conserved in several families including the Fabaceae (lentil and pea: Weeden et al., 1992; mung bean and cowpea: Menancio-Hautea et al., 1993), the Solanaceae (potato and tomato: Tanksley et al., 1992) and the Poaceae (maize, rice and sorghum: Devos and Gale, 2000). However, the gene order appeared quite divergent in the Poaceae (rye and wheat: Devos et al., 1992a, b), the Solanaceae (pepper and tomato: Livingstone et al., 1999) and the diploid and amphiploid Brassica species (Paterson et al., 2000). Very limited conservation has also been found in the most recent fine scale comparisons of maize, rice and sorghum, when mapped bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) sequences have been used to measure collinearity (Lai et al., 2004).

POLYPLOIDY

Adaptive benefit of polyploidy

One of the most intriguing questions facing plant evolutionists is why there are so many polyploid species. The majority of plant species have high chromosome numbers and it has been estimated that 2–4 % of all speciation events represent polyploidy (Ramsey and Schemske, 1998; Otto and Whitten, 2000). Ancient cycles of genome duplication have been documented in a number of crop species including the cole crops, corn, cotton, soybean and many of the important cereals (Blanc et al., 2000; Wendel, 2000; Lukens et al., 2004). The complete sequence data recently completed for arabidopsis and rice support this notion (Bennetzen, 2002). The most commonly implicated advantage of polyploidy over diploidy is increased heterozygosity (Barber, 1970; Manwell and Baker, 1970), and nearly all polyploids that have been examined with molecular markers have been found to have high levels of heterozygosity (Gottlieb, 1982; Soltis and Soltis, 1993, 1999).

Most polyploids are thought to have arisen through the unification of unreduced gametes (Harlan and deWet, 1975; Bretagnolle and Thompson, 1995). The initial level of heterozygosity transmitted via these unreduced gametes has been shown in crop plants to be dependent on the process of 2n-gamete formation. There are a number of events that can result in unreduced gametes, but the most common are first division restitution (FDR) and second division restitution (SDR). In FDR, homologous chromosomes do not separate during meiosis I, while in SDR sister chromatids do not separate during meiosis II. Assuming one cross-over per chromosome, it has been calculated that FDR transmits 80·2 % of the parental heterozygosity to the gametes and SDR transmits 39·6 % (Hermson, 1984). Cytogenetic studies of FDR and SDR have been undertaken in potato (Mok and Peloquin, 1975; Mendiburu and Pelequin, 1977; Douches and Quiros, 1988), alfalfa (Vorsa and Bingham, 1979) and maize (Rhodes and Dempsey, 1966).

Self-fertility in polyploids

It has long been assumed that polyploid species should have higher rates of self-fertilization than their diploid progenitors (Stebbins, 1950), because selfing would facilitate the likelihood of finding mates after the initial polyploidization event and having multiple genes would shield the raw polyploids from the deleterious effects of inbreeding (Marple, 2004).

Numerous studies of natural species have shown that polyploidy can in some instances increase levels of self-fertility through the breakdown of self-incompatibility systems (Mable, 2004). This probably occurs because of competition among alleles in diploid pollen (Stone, 2004). However, there is not a strong association between polyploidy and self-compatibility at the level of species or family, and it is more likely that polyploids carrying multiple alleles will show varying levels of self-compatibility (SC) rather than a complete breakdown of SI. Several recent studies on sour cherries have shown that levels of SC are associated with the segregation of functional and nonfunctional alleles at the pollen-S locus (Hauck et al., 2002; Ushijima et al., 2004; Yamane et al., 2005).

There is some direct evidence that tetraploid species can tolerate more inbreeding than their diploid progenitors (Husband and Schemske, 1997; Cook and Soltis, 2000), but this has not been found to be the case in the autopolyploid crop species, alfalfa and potato. In fact, both these species are highly outcrossed and very subject to inbreeding depression (Bingham, 1980). It has been proposed that self-infertility in these autopolyploid species might be tied to the loss of higher-order allelic interactions in what is known as the overdominance model of inbreeding depression (Bever and Felber, 1992). Evidence for this possibility has come from the observation that inbreeding depression in alfalfa and potato is much greater than would be predicted by the coefficient of inbreeding in a two-allele model (Busbice and Wilsie, 1966; Mendoza and Haynes, 1974; Mendiburu and Peloquin, 1977).

Supportive data for the importance of higher-order allelic interactions in autopolyploids has come from comparisons of the self-fertility of autotetraploids of alfalfa with different genetic structures. Bingham and his group (Dunbier and Bingham, 1975; Bingham, 1980) produced diploids from natural tetraploids by haploidy, generated diploid hybrids, and then doubled the diploid hybrids using colchicine treatments to obtain defined two-allele duplexes (di-allele loci). These were then crossed to produce double hybrids with presumed tetra-allelic interactions. When the performance of these different structured populations was compared, ‘progressive heterosis’ was observed as the diploid hybrids had higher above-ground biomass than their diploid parents, and the double hybrids had the highest productivity of all.

Genetic differentiation in polyploids

In spite of the advantages thought to be associated with increased heterozygosity, polyploidy has long been considered to be a conservative rather than a progressive force in evolution (Stebbins, 1950, 1971; Grant, 1981). It was thought that the presence of multiple alleles reduced the effect of single alleles and genetic differentiation was further restricted by the lack of segregation due to fixed heterozygosities in allopolyploids and the reduced rate of segregation due to tetrasomic inheritance in autopolyploids.

This conservative opinion about the evolutionary potential of polyploids has dramatically changed in recent years. Polyploids may indeed evolve slower than diploids due to the buffering effect of multiple alleles, but they may actually have a broader adaptive potential. There is a greater potential dose span between additive alleles in polyploids, allowing for a greater range in phenotype, and the higher levels of genetic variability generally found in polyploids allows for more possible assortments of genes (Hancock, 2004). This possibility has been most dramatically demonstrated in the breeding of polyploid crop species. Over two-thirds of crop species are polyploids, and breeders have substantially improved most of them for numerous traits. A particularly dramatic example can be seen for the autoallo-octoploid strawberry where Bringhurst and Voth (1984) have been able to increase its yields by 500 % over 25 years of artificial selection.

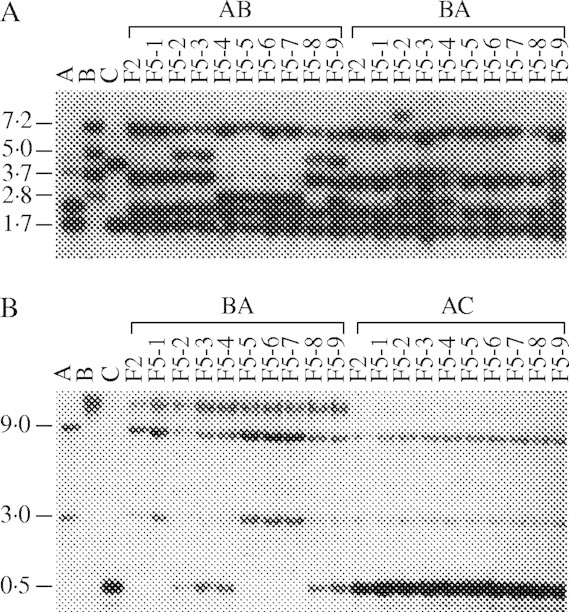

There is growing evidence that there is genome downsizing in polyploidy plants after formation (Lai et al., 2004; Leitch and Bennett, 2004) and synteny among homeologues can decay rapidly after polyploidy (Ilic et al., 2003; Langham et al., 2004). Exciting studies on the cole crops and wheat have also indicated that newly formed polyploids can undergo dramatic genome rearrangements that could result in rapid evolution. Song et al. (1995) produced reciprocal hybrids between the diploids Brassica rapa and B. nigra, and B. rapa and B. oleraceae. The F1 individuals were colchicine doubled and progenies were generated to the F5 generation by selfing. They then conducted an RFLP analysis of F2 and F5 individuals of each line, using 89 nuclear DNA probes, and found substantial genomic alterations in the F5 generation, including losses of parental fragments and gains of novel fragments (Fig. 2). Almost twice as much change was observed in the combinations involving the two most distant relatives, B. rapa and B. nigra, and they observed more change in some nuclear/cytoplasmic combinations than others.

Fig. 2.

Nuclear RFLP patterns of Brassica rapa, B. nigra, B. oleraceae, F2 hybrids between them and F5 populations. (A) HindIII-digested DNAs probed with EZ3, which show a loss of fragments and a gain of fragments in some F5 plants (5·0 kb and 2·8 kb). (B) HpaII-digested DNAs probed with EC3C8 showing a gain of a 0·5-kb fragment in five BA F5 plants, which does not exist in either the A or B parental genome, but which is present in the C genome parent and all AC F5 plants (Song et al., 1995).

In the work on wheat, Feldman et al. (1997) began by examining RFLP patterns in natural diploid and allopolyploid species. They used 16 probes that were from low-copy, non-coded DNA. Nine of these probes were found in all the diploid species. indicating they were conserved, but when they examined aneuploid and nullisomic lines, they found that each sequence was only retained in one of the allopolyploid genomes. In follow-up work, Liu et al. (1998a, b) examined RFLP fragment profiles of both coding and non-coding sequences in synthetic tetraploid, hexaploid and octoploids of Triticum and Aegilops that had been selfed for three to five generations. They obtained similar results to Feldman et al. (1997), observing non-random sequence elimination in all the allopolyploids studied, along with the occasional appearance of unique fragments. They also found that some of the changes were brought about by DNA methylation. By comparing crosses with and without the PH1 gene that regulates bivalent pairing, they were able to deduce that intergenomic recombination did not play a role in the sequence change, as both types of crosses yielded about the same amount of change.

In two further studies, the Feldman group found that the direction of sequence change in wheat followed a different pattern to that observed by Song's group in Brassica, and confirmed that some sequences were silenced by elimination, while others were silenced through methylation. Ozkan et al. (2001) analysed diploid parental generations, F1 progeny and the first three generations of (S1, S2 and S3) of synthetic hybrids of several species of Aegilops and Triticum. When they followed the rate of elimination of eight low-copy DNA sequences, they found that sequence elimination began earlier in the synthetic allopolyploids that most closely represented naturally occurring ones, and sequence elimination was not associated with cytoplasm. Shaked et al. (2001) used AFLP and methylation-sensitive amplification polymorphism fingerprinting (MSAP) to evaluate another set of diploid and tetraploid hybrids within and between genera. They also found considerable sequence elimination after polyploidy that occurred most rapidly in allopolyploids of the same species rather than different species. Further analysis indicated that some of the sequences were eliminated, while others were altered by cytosine methylation.

The Feldman group has suggested that the observed sequence alterations may play a physical role in how chromosomes pair, resulting in the bivalent meiotic behaviour of newly formed allopolyploids. However, sequence losses do not appear to be necessary for bivalent pairing behaviour, as Liu et al. (2001) found little evidence of change in 22 000 AFLP loci in artificial hybrids of cotton, even though pairing in cotton tetraploids is strictly bivalent. It is also unknown why the most divergent genomes were altered the most in Brassica, while the opposite was true in wheat. Perhaps transposons play a role, with the direction and degree of perturbations being associated with the unification of genomes with or without unique mobile elements.

Emerging research

The almost completed sequencing of the two major subspecies of cultivated rice, Oryza sativa ssp. japonica (Goff et al., 2002) and O. sativa ssp. indica (Yu et al., 2002) offers plant evolutionary biologists with a number of exciting research possibilities. Opportunities abound for studying the nature of adaptation at the molecular level, as these two species have very distinct ecological ranges. The indica subspecies is most widely cultivated in China and most of Asia, while the japonica rice is grown in Japan and other temperate regions. The rice sequence data can be compared with other species sequences to examine rates of evolution in a wide range of selectively significant and neutral traits.

Broad comparisons of molecular evolution across species boundaries are likely to be possible, as the relative numbers and types of genes found in rice are very similar to those found in arabidopsis, and at least 80 % of the genes that have been found in arabidopsis are in rice. The plant genome appears to quite distinct from the fungal and animal ones, as about one-third of the genes found in plants are missing in the fungi and animals, and the genomes of both rice and arabidopsis have many more copies of genes than the other two kingdoms (Bennetzen, 2002). The sequence data now available will afford evolutionary biologists with the opportunity to study the origin of gene families, track their subsequent divergence and should provide hints about how genes diverge and produce proteins with novel biological properties.

Evolutionary biologists have already begun to mine the rice sequence data and have made some very interesting observations. Paterson et al. (2004) compared genomic data from rice with other taxa, and came to the conclusion that an ancient polyploidization occurred before the divergence of the cereals. Vandepoele et al. (2003) used the rice genome data to conclude that aneuploidy, and the duplication of one chromosome, played an important role in cereal evolution. Most recently, Jiang et al. (2004) used rice sequence data to discover that common transposable elements, MULEs, often carry fragments of genes. This likely represents an important mechanism for the evolution of genes in higher plants, where genomic sequences are shuffled and reorganized to create novel, adaptively significant genes. Without complete sequence data, the prevalence of this phenomenon would not have been recognized.

Acknowledgments

I would like to acknowledge the rich environment in the plant sciences at Michigan State University. In few other places in the world is there such a well-stocked pool of evolutionary biologists, molecular biologists and plant breeders. Vigorous, inter-departmental programmes exist in ecology, evolutionary biology and behaviour; genetics; plant breeding and genetics; and molecular and cellular biology.

LITERATURE CITED

- Allard RW. 1988. Genetic changes associated with the evolution of adaptedness in cultivated plants and their wild progenitors. Journal of Heredity 79: 225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allard RW. 1990. The genetics of host–pathogen coevolution: implications for genetic resource conservation. Journal of Heredity 81: 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstead LP, Turner LB, Farrell M, Skot L, Gomez P, Montoya T, Donnison IS, King IP, Humphreys MO. 2004. Synteny between a major heading-date QTL in perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.) and the Hd3 Heading-date locus in rice. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 108: 822–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber HN. 1970. Hybridization and the evolution of plants. Taxon 19: 154–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen JL. 2000. Comparative sequence analysis of plant nuclear genomes: microcolinearity and its many exceptions. The Plant Cell 12: 1021–1029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennetzen J. 2002. Opening the door to comparative plant biology. Science 296: 60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergelson J, Kreitman M, Stahl EA, Tian D. 2001. Evolutionary dynamics of plant R-genes. Science 292: 2281–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bever JD, Felber F. 1992. The theoretical population genetics of autopolyploids. Oxford Surveys of Evolutionary Biology 8: 185–217. [Google Scholar]

- Bingham ET. 1980. Maximizing heterozygosity in autopolyploids. In: Lewis WD, ed. Polyploidy. New York: Plenum Press. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc G, Barakat A, Guyot R, Cook R, Delseny M. 2000. Extensive duplication and reshuffling in the Arabidopsis genome. The Plant Cell 12: 1093–1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bres-Patry C, Lorieux M, Clément G, Bangratz M, Ghesquière A. 2001. Heredity and genetic mapping of domestication-related traits in a temperate japonica weedy race. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 102: 118–126. [Google Scholar]

- Bretagnolle F, Thompson JD. 1995. Gametes with the somatic chromosome number: mechanisms of their formation and role in the evolution of autopolyploid plants. New Phytologist 129: 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bringhurst RS, Voth V. 1984. Breeding octoploid strawberries. Iowa State Journal of Research 58: 371–382. [Google Scholar]

- Buerkle TH, Morris RJ, Asmussen MA, Rieseberg LH. 2000. The likelihood of homoploid hybrid speciation. Heredity 84: 441–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busbice TH. 1968. Effects of inbreeding on fertility in Medicago sativa L. Crop Science 8: 231–234. [Google Scholar]

- Busbice CA, Wilsie CP. 1966. Inbreeding depression and heterosis in autotetraploids with application to Medicago sativa L. Euphytica 15: 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo AL, Schaal BA. 2004. Heterogeneous evolutionary processes affect R gene diversity in natural populations of Solanum pimpinellifolium Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 101: 17444–17449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chacón S, Pickersgill B, Debouck DG. 2005. Domestication patterns in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) and the origin of the Mesoamerican and Andean cultivated races. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 110: 432–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang TT. 1995. Rice, Oryza sativa and Oryza glabberima (Gramineae – Oryzeae). In: Smartt J, Simmonds NW, eds. Evolution of crop plants. Harlow: Longman Scientific and Technical. [Google Scholar]

- Cook LM, Soltis PS. 2000. Mating systems of diploid and allotetraploid populations of Tragapogon (Asteraceae). Heredity 84: 410–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe LK. 1971. The polygenic control of outbreeding in Borago officinalis Heredity 27: 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- deNettancourt D. 2001.Incompatibility and incongruity in wild and cultivated plants. Berlin: Springer-Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- Devos KM, Gale MD. 2000. Genome relationships: the grass model in current research. The Plant Cell 12: 637–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos KM, Atkinson MD, Chinoy CN, Liu CJ, Gale MD. 1992. Chromosomal rearrangements in rye genome relative to that of wheat. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 85: 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devos KM, Chinoy MD, Liu CJ, Gale MD. 1992. RFLP-based genetic map of the homeologous group 3 chromosomes of wheat and rye. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 83: 931–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley J, Stec A, Wendal J, Edwards M. 1990. Genetic and morphological analysis of a maize-teosinte F2 population: implications for the origin of maize. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 87: 9888–9892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doebley J, Stec A, Gustus C. 1995.teosinte branched1 and the origin of maize: evidence for epistasis and the evolution of dominance. Genetics 141: 333–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doganlar S, Frary A, Daunay M-C, Lester RN, Tanksley SD. 2002. Conservation of gene function in the Solanaceae as revealed by comparative mapping of domestication traits in eggplant. Genetics 161: 1713–1726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorweiler J, Stec A, Kermicle J, Doebley J. 1993.Teosinte glume architecture 1: a genetic locus controlling a key step in maize evolution. Science 262: 233–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douches DS, Quiros CF. 1988. Genetic strategies to determine the mode of 2n gamete production in diploid potatoes. Euphytica 38: 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Dunbier MW, Bingham ET. 1975. Maximum heterozygosity in alfalfa: results using haploid-derived autotetraploids. Crop Science 15: 527–531. [Google Scholar]

- East EM. 1916. Studies on size inheritance in Nicotiana Genetics 1: 164–176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellstrand NC, Prentice HC, Hancock JF. 1999. Gene flow and introgression from domesticated plants into their wild relatives. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 30: 539–563. [Google Scholar]

- Falconer DS, Mackay TFC. 1996.Introduction to quantitative genetics. New York: Burgess Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr WR. 1987.Principles of cultivar development Vol. I. Theory and technique. New York: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Feldman M, Liu B, Segal G, Addo A, Levy AA, Vega JM. 1997. Rapid elimination of low-copy DNA sequences in polyploid wheat: a possible mechanism for differentiation of homeologous chromosomes. Genetics 147: 1381–1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford EB. 1975.Ecological genetics: the evolution of super-genes. London: Chapman & Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Frary A, Nesbitt TC, Frary A, Grandillo S, van der Knapp E, Cong B, et al. 2000. fw2.2: a quantitative trait locus key to the evolution of tomato fruit size. Science 289: 85–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frary A, Doganlar S, Daunay MC, Tanksley SD. 2003. QTL analysis of morphological traits in eggplant and implications for conservation of gene function during evolution of Solanaceous species. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 107: 359–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frary A, Fritz LA, Tanksley SD. 2004. A comparative study of the genetic basis of natural variation in tomato leaf, sepal and petal morphology. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 109: 523–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P. 1988. A middle American and an Andean common gene pool. In: Gepts P, ed. Genetic resources of Phaseolus beans. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic, 375–390. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P. 1998. Origin and evolution of common bean: past events and recent trends. HortScience 33: 1124–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Gepts P, Bliss FA. 1985. F1 weakness in the common bean. Journal of Heredity 76: 447–450. [Google Scholar]

- Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan T-H, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, et al. 2002. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science 296: 92–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gottlieb LD. 1982. Conservation and duplication of isozymes in plants. Science 216: 373–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandillo S, Tanksley SD. 1996. QTL analysis of horticultural traits differentiating the cultivated tomato from the closely related species Lycopersicon pimpinellifolium Theoretical and Applied Genetics 92: 935–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandillo S, Ku HM, Tansley SD. 1999. Identifying the loci responsible for natural variation in fruit size and shape in tomato. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 99: 978–987. [Google Scholar]

- Grant V. 1981.Plant speciation, 2nd edn. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi KR, Ascher PD. 1988. Fertile, intermediate hybrids between Phaseolus vulgaris and P. acutifolius from congruity backcrossing. Sexual Plant Reproduction 1: 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Hancock JF. 2004.Plant evolution and the origin of crop species. Wallingford: CABI Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JR. 1992.Crops and man. Madison, WI: American Society of Agronomy. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JR, deWet JMJ. 1972. A simplified classification of cultivated sorghum. Crop Science 12: 172–176. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JR, deWet JMJ. 1975. On Ö. Winge and a prayer: the origins of polyploidy. Botanical Review 41: 361–390. [Google Scholar]

- Harlan JR, deWet JMJ, Price EG. 1973. Comparative evolution of cereals. Evolution 27: 311–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchett JH, Gallum R. 1970. Genetics of the ability of the Hessian fly, Mayetiola destructor, to survive on wheats having different genes for resistance. Annual Report of the Entomological Society of America 63: 1400–1407. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck NR, Yamane H, Tao R, Iezzoni A. 2002. Self-incompatibility and compatibility in tetraploid sour cherry (Prunus cerasus L.). Sexual Plant Reproduction 15: 39–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hautea RA, Coffman WR, Sorrells ME, Bergstrom GC. 1987. Inheritance of partial resistance to powdery mildew in spring wheat. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 73: 609–615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermsen JGT. 1984. Nature, evolution and breeding of polyploids. Iowa State Journal of Research 58: 411–420. [Google Scholar]

- Hogenboom NG. 1973. A model for incongruity in intimate partner relationships. Euphytica 22: 219–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hogenboom NG. 1975. Incompatibility and incongruity: two different mechanisms for the non-functioning of intimate partner relationships. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London Series B 188: 361–375. [Google Scholar]

- Hokanson K, Hancock JF. 2000. Early-acting inbreeding depression in three species of Vaccinium Sexual Plant Reproduction 13: 145–150. [Google Scholar]

- Husband BC, Schemske DW. 1997. The effect of inbreeding in diploid and tetraploid populations of Epilobium angustifolium (Onagraceae): implications for the genetic basis of inbreeding depression. Evolution 51: 737–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igic B, Kohn JR. 2001. Evolutionary relationships among self-incompatibility RNases. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA 98: 13167–13171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilic K, SanMiguel PJ, Bennetzen JL. 2003. A complex history of rearrangement in an orthologous region of the maize, sorghum and rice genomes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 100: 12265–12270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang N, Bao Z, Zhang X, Eddy SR, Wessler SR. 2004. Pack-MULE transposable elements mediate gene evolution in plants. Nature 431: 569–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis DI, Hodgkin T. 1999. Wild relatives and crop cultivars: detecting natural introgression and farmer selection of new genetic combinations in agroecosystems. Molecular Ecology 8: S159–S173. [Google Scholar]

- Johannsen W. 1903.Uber Enblichkeit in populationen und in reinen Linien. Jena: Gustav Fischer. [Google Scholar]

- Kao T, Tsukamoto T. 2004. The molecular and genetic bases of S-RNase-based self-incompatibility. The Plant Cell 16: S72–S83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp BP, Doughty J. 2003. Just how complex is the Brassica S-receptor complex? Journal of Experimental Botany 54: 157–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiang YT, Antonovics J, Wu L. 1979. The extinction of wild rice (Oryza perennis formosana) in Taiwan. Journal of Asian Ecology 1: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S-C, Rieseberg LH. 2001. The contribution of epistasis to species of Aegilops species differences in annual sunflowers. Molecular Ecology 10: 683–690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinange EMK, Singh SP, Gepts P. 1996. Genetic control of the domestication syndrome in common bean. Crop Science 36: 1037–1045. [Google Scholar]

- Krebs SL, Hancock JF. 1991. Embryonic genetic load in the highbush blueberry, Vaccinium corymbosum (Ericaceae). American Journal of Botany 78: 1427–1437. [Google Scholar]

- Kruijt M, Brandwagt BF, deWet PJGM. 2004. Rearrangements in the Cf-9 disease resistance gene cluster of wild tomato have resulted in three genes that mediate Avr9 responsiveness. Genetics 168: 1655–1663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai J, Ma J, Swigonová Z, Ramakrishna W, Linton E, Llaca V, et al. 2004. Gene loss and movement in the maize genome. Genome Research 14: 1924–1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langham RJ, Walsh J, Dunn M, Ko C, Goff SA, Freeling M. 2004. Genomic duplication, fractionation and the origin of regulatory novelty. Genetics 166: 935–945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leath S, Pederson WD. 1986. Comparison of near-isogenic maize lines with and without the Ht1 gene for resistance to four foliar pathogens. Phytopathology 76: 108–111. [Google Scholar]

- Leitch IJ, Bennett MD. 2004. Genome downsizing in polyploid plants. Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 82: 651–663. [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA. 2000.The origin, expansion, and demise of plant species. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Levin DA, Francisco-Ortega J, Jansen RK. 1996. Hybridization and the extinction of rare plant species. Conservation Biology 10: 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. 1979.Sexual incompatibility in plants. London: Edward Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Vega JM, Feldman M. 1998. Rapid genomic changes in newly synthesized amphiploids of Triticum and Aegilops II. Changes in low copy coding DNA sequences. Genome 41: 535–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Vega JM, Segal G, Abbo S, Rodova M, Feldman M. 1998. Rapid genomic changes in newly synthesized amphiploids of Triticum and Aegilops I. Changes in low copy non-coding sequences. Genome 41: 272–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Brewbaker CL, Mergeai G, Cronn RC, Wendel JF. 2001. Polyploid formation in cotton is not accompanied by rapid genomic changes. Genome 44: 321–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Cong B, Tanksley SD. 2003. Generation and analysis of an artificial gene dosage series in tomato to study the mechanisms by which the cloned quantitative trait locus fx2.2 controls fruit size. Plant Physiology 132: 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Z, Moore PH, Ma H, Ackerman CM, Ragiba M, Yu Q, et al. 2004. A primitive Y chromosome in papaya marks incipient sex chromosome evolution. Nature 427: 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone KD, Lackney VK, Blauth JR, van Wijk R, Jahn MK. 1999. Genome mapping in Capsicum and the evolution of genome structure in the Solanaceae. Genetics 152: 1183–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukens LN, Doebley J. 1999. Epistatic and environmental interactions for quantitative trait loci involved in maize evolution. Genetical Research 74: 291–302. [Google Scholar]

- Lukens LN, Quijada PA, Udall J, Pires JC, Schranz ME, Osborn TC. 2004. Genome redundancy and plasticity within ancient and recent Brassica crop species. Journal of the Linnean Society 82: 665–674. [Google Scholar]

- McCubbin AG, Kao T-H. 2000. Molecular recognition and response in pollen and pistil interactions. Annual Review of Cellular and Developmental Biology 16: 333–364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma H, Moore PH, Liu Z, Kim MS, Yu Q, Fitch MMM, et al. 2004. High-density linkage mapping revealed suppression of recombination at the sex determination locus in papaya. Genetics 166: 419–436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mable BK. 2004. Polyploidy and self-incompatibility: is there an association? New Phytologist 162: 803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manwell C, Baker CM. 1970.Molecular biology and the origin of species. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marple BK. 2004. Polyploidy and self-compatibility: is there an association? New Phytologist 162: 803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GB, Bogdanove AJ, Sessa G. 2003. Understanding the functions of plant disease proteins. Annual Review of Plant Biology 54: 23–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin TJ, Ellingboe AH. 1976. Differences between compatible parasite host genotype involving the Pm4 locus of wheat and the corresponding genes in Erysiphe graminis f. sp. Tritici. Phytopathology 66: 669–679. [Google Scholar]

- Mather K, Jinks JL. 1977.Introduction to biometrical genetics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mayr E. 1942.Systematics and the origin of species. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mei HW, Luo LJ, Ying CS, Wang YP, Yu XQ, Guo LB, Paterson AH, Li ZK. 2003. Gene actions of QTL affecting several agronomic traits resolved in a recombinant inbred rice population and two testcross populations. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 107: 89–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menancio-Hautea D, Fatokun CA, Kumar L, Danesh D, Young ND. 1993. Comparative genome analysis of mungbean (Vigna radiata L. Wilczek) and cowpea (V. unguiculata L. Walpers) using RFLP mapping data. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 86: 797–810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiburu AO, Peloquin SJ. 1977. The significance of 2N gametes in potato breeding. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 49: 53–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendoza HA, Haynes FL. 1974. Genetic basis of heterosis for yield in the autotetraploid potato. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 45: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok DWS, Peloquin SJ. 1975. Three mechanisms of 2n pollen formation in diploid potatoes. Canadian Journal of Genetics and Cytology 17: 217–225. [Google Scholar]

- Nasrallah JB. 2002. Recognition and rejection of self in plant reproduction. Science 296: 305–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbitt TC, Tanksley SD. 2002. Comparative sequencing in the genus Lycopersicon: implication for the evolution of fruit size in the domestication of cultivated tomatoes. Genetics 162: 365–379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson-Ehle H. 1909. Kreuzungsuntersuchungen as Hafer and Wiezen. Lunds Univ Avarkr. N.F Afd Ser 25: 1–122. [Google Scholar]

- Nimchuk Z, Eulgem T, Holt BF, Dangl. 2003. Recognition and response in the plant immune system. Annual Review of Genetics 37: 579–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otto SP, Whitton J. 2000. Polyploid incidence and evolution. Annual Review of Genetics 34: 401–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozkan H, Levy AA, Feldman M. 2001. Allopolyploidy-induced rapid genome evolution in the wheat (Aegilops-Triticum group). The Plant Cell 13: 1735–1747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panetsos CA, Baker HG. 1967. The origin of variation in ‘wild’ Raphanus sativus (Cruciferae) in California. Genetica 38: 243–274. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH. 1995. Molecular dissection of quantitative traits: progress and prospects. Genome Research 5: 321–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Schertz KF, Lin Y, Li Z. 1998.Case history in plant domestication: sorghum, an example of cereal evolution. London: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Burlow MD, Draye X, Elsik CG, Jiang C-X, et al. 2000. Comparative genomics of plant chromosomes. The Plant Cell 12: 1523–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson AH, Bowers JE, Chapman BA. 2004. Ancient polyploidization predating divergence of the cereals, and its consequences for comparative genomics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 101: 9903–9908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson WL, Leath S. 1988. Pyramiding major genes for resistance to maintain residual effects. Annual Review of Phytopathology 26: 369–378. [Google Scholar]

- Poncet V, Lanny F, Enjalbert J, Joly H, Sarr A, Robert T. 1998. Genetic anaylsis of the domestication syndrome in pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum L, Poaceae): inheritance of the major characters. Heredity 81: 648–658. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey J, Schemske DW. 1998. Pathways, mechanisms, and rates of polyploidy formation in flowering plants. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29: 467–501. [Google Scholar]

- Rhodes MM, Dempsey E. 1966. Introduction of chromosome doubling at meiosis by the elongate gene in maize. Genetics 54: 505–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH. 1995. The role of hybridization: old wine in new skins. American Journal of Botany 82: 944–953. [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH. 2000. Genetic mapping as a tool for studying speciation. In: Soltis DE, Soltis PS, Doyle JJ, eds. Molecular systematics of plants. Vol. II. DNA sequencing, Boston: Kluwer Academic. [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, van Fossen C, Desrochers A. 1995. Hybrid speciation accompanied by genomic reorganization in wild sunflowers. Nature 375: 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Sinervo B, Linder CR, Ungerer M, Arias DM. 1996. Role of gene interactions in hybrid speciation : evidence from ancient and experimental hybrids. Science 272: 741–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rieseberg LH, Baird SJE, Gardner KA. 2000. Hybridization, introgression and linkage evolution. Plant Molecular Biology 42: 205–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schemske DW. 2000. Understanding the origin of species. Evolution 54: 1069–1073. [Google Scholar]

- Seavey SR, Carter SK. 1994. Self-fertility in Epilobium obcordatum (Onagraceae). American Journal of Botany 81: 331–338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shamray SN. 2003. Plant resistance genes: molecular and genetic organization, function and evolution. Zhurnal Obshchei Biologii 64: 195–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaked H, Kashkuh K, Ozban H, Feldman M, Levy AA. 2001. Sequence elimination and cytosine methylation are rapid and reproducible responses of the genome to wide hybridization and allopolyploidy in wheat. The Plant Cell 13: 1749–1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shii CT, Mok MC, Mok DWS. 1981. Developmental controls of morphological mutants of Phaseolus vulgaris L: differential expression of mutant loci in plant organs. Developmental Genetics 2: 279–290. [Google Scholar]

- Sijacic P, Wang X, Skirpan AL, Wang Y, Dowd PE, McCubbin AG, et al. 2004. Identification of the pollen determinant of S-RNase-mediated self-incompatibilty. Nature 429: 302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva NF, Goring DR. 2001. Mechanisms of self-incompatibility in flowering plants. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 58: 1988–2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smartt J. 1984. Gene pools in grain legumes. Economic Botany 38: 24–35. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 1993. Molecular data and the dynamic nature of polyploidy. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 12: 243–273. [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 1999. Polyploidy: recurrent formation and genome evolution. Trends in Ecology and Systematics 14: 348–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soltis DE, Soltis PS. 2000. The role of genetic and genomic attributes in the success of polyploids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 97: 7051–7057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song KM, Lu P, Tang K, Osborn TC. 1995. Rapid genome change in synthetic polyploids of Brassica and its implications for polyploidy evolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 92: 7719–7723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins GL. 1950.Variation and evolution in plants. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stebbins GL. 1971.Chromosomal variation in higher plants. London: Arnold. [Google Scholar]

- Stone JL. 2004. Sheltered load associated with S-alleles in Solanum carolinense Heredity 92: 335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley SD. 1993. Mapping polygenes. Annual Review of Genetics 27: 205–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley SD, Ganal MW, Prince JP, de Vicente MC, Bonierbale MW, Broun P, et al. 1992. High density molecular linkage maps of the tomato and potato genomes. Genetics 132: 1141–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ushijima K, Yamane H, Watari A, Kakehi E, Ikeda K, Hauck NR, et al. 2004. The S haplotype-specific F-box protein gene, SFB, is defective in self-compatible haplotypes of Prunus avium and P. mume The Plant Journal 39: 573–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandepoele K, Simillion C, Van de Peer Y. 2003. Evidence that rice and other cereals are ancient anueploids. The Plant Cell 15: 2192–2202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viard F, Bernard J, Desplanque B. 2002. Crop-weed interactions in the Beta vulgaris complex at a local scale: allelic diversity and gene flow within sugar beet fields. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 104: 688–697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vorsa N, Bingham ET. 1979. Cytology of 2n pollen production in diploid alfalfa, Medicago sativa Canadian Journal of Genetics and Cytology 21: 525–530. [Google Scholar]

- Wade MJ. 1992. Sewell Wright: gene action and the shifting balance theory. Oxford Survey of Evolutionary Biology 8: 35–62. [Google Scholar]

- Wallace B. 1968.Topics in population genetics: coadaptation. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Wang DL, Zhu J, Li ZK, Paterson AH. 1999. Mapping QTLs with epistatic effects and QTL × environmental interactions by mixed linear model approaches. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 99: 1255–1264. [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Nussbaum-Wagler T, Li B, Zhao Q, Vigouroux Y, Faller M, Bomblies K, Lukens L, Doebley JF. 2005. The origin of the naked grains of maize. Nature 436: 714–719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weeden NF, Muehlbauer FG, Ladizinsky G. 1992. Extensive conservation of linkage relationships between pea and lentil genetic maps. Journal of Heredity 83: 123–129. [Google Scholar]

- Weller SG, Ornduff R. 1989. Incompatibility in Amsinckia grandiflora (Boraginaceae): distribution of callose plugs and pollen tubes following inter and intramorph crosses. American Journal of Botany 76: 277–282. [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF. 2000. Genome evolution in polyploids. Plant Molecular Biology 42: 225–249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendel JF, Percy RG. 1990. Allozyme diversity and introgression in the Galapagos Islands endemic Gossypium darwinii and its relationship to continental G. barbadense Biochemical Ecology and Systematics 18: 517–528. [Google Scholar]

- Westerbergh A, Doebley J. 2004. Quantitative trait loci controlling phenotypes related to the perennial versus annual habit in wild relatives of maize. Theoretical and Applied Genetics 109: 1544–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiens D, Calvin CL, Wilson CA, Davern CI, Frank D, Seavey SR. 1987. Reproductive success, spontaneous embryo abortion and genetic load in flowering plants. Oecologia 71: 501–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright SI, Bi IV, Schoeder SG, Yamasaki M, Doebley JF, McMullen MD, Gaut BS. 2005. The effects of artificial selection on the maize genome. Science 308: 1310–1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong LZ, Liu KD, Dai XK, Xu CG, Zhang Q. 1999. Identification of genetic factors controlling domestication-related traits of rice using an F2 population of a cross between Oryza sativa and O. rufipogan Theoretical and Applied Genetics 98: 243–251. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Li J, Grandillo S, Ahn SN, Yuan L, Tanksley SD, et al. 1998. Identification of trait-improving quantitative trait loci alleles from a wild rice relative, Oryza rufipogan. Genetics 150: 899–909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao S, Emerson B, Ratanasut K, Patrick E, O'Neill CO, Bancroft I, Turner JG. 2004. Origin and maintenance of a broad-spectrum disease resistance locus in Arabidopsis Molecular Biology and Evolution 21: 1661–1672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto T, Lin H, Sasaki T, Yano M. 2000. Identification of heading date quantitative trait locus Hd6 and characterization of its epistatic interactions with Hd2 in rice using advanced backcross progeny. Genetics 154: 885–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamane H, Ikeda K, Hauck NR, Iezzoni AF, Tao R. 2003. Self-incompatibility (S) locus region of the mutated S6-haplotype of sour cherry (Prunus cerasus) contains a functional pollen S allele and a non-functional pistil S allele. Journal of Experimental Botany 54: 2431–2437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M, Katayose Y, Ashikari M, Yamamouchi U, Monna L, Fuse T, et al. 2000.Hd1 a major photoperiod sensitivity quantitative trait locus in rice is closely related to the Arabidopsis flowering time gene CONSTANS. The Plant Cell 12: 2473–2483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu SB, Li JX, Tan YF, Gao YJ, Li XH, Zhang Q, et al. 1997. Importance of epistasis as the genetic basis of heterosis in an elite rice hybrid. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the USA 94: 9226–9231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK-S, Li S, Liu B, et al. 2002. A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science 296: 79–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yule GU. 1906. On the theory of inheritance of quantitative compound characters on the basis of Mendel's laws – a preliminary note. In: Report of the 3rd International Conference on Genetics, 140–142. [Google Scholar]