Abstract

Background:

Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and Murray et al. have both produced sets of estimates for worldwide HIV incidence, prevalence and mortality. Understanding differences in these estimates can strengthen the interpretation of each.

Methods:

We describe differences in the two sets of estimates. Where possible, we have drawn on additional published data to which estimates can be compared.

Findings:

UNAIDS estimates that there were 6 million more people living with HIV (PLHIV) in 2013 (35 million) compared with the Murray et al. estimates (29 million). Murray et al. estimate that new infections and AIDS deaths have declined more gradually than does UNAIDS. Just under one third of the difference in PLHIV is in Africa, where Murray et al. have relied more on estimates of adult mortality trends than on data on survival times. Another third of the difference is in North America, Europe, Central Asia and Australasia. Here Murray et al. estimates of new infections are substantially lower than the number of new HIV/AIDS diagnoses reported by countries, whereas published UNAIDS estimate tend to be greater. The remaining differences are in Latin America and Asia where the data upon which the UNAIDS methods currently rely are more sparse, whereas the mortality data leveraged by Murray et al. may be stronger. In this region, however, anomalies appear to exist between the both sets of estimates and other data.

Interpretation:

Both estimates indicate that approximately 30 million PLHIV and that antiretroviral therapy has driven large reductions in mortality. Both estimates are useful but show instructive discrepancies with additional data sources. We find little evidence to suggest that either set of estimates can be considered systematically more accurate. Further work should seek to build estimates on as wide a base of data as possible.

Keywords: HIV estimates, incidence prevalence, mortality UNAIDS

Introduction

Murray et al.[1] have recently published estimates of the number of new HIV infections, the number of persons living with HIV (PLHIV) and the number of AIDS deaths for all countries. These can be contrasted with other estimates released by Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) [2]. These two sets of estimates are computed in related but different ways and it should, therefore, come as no surprise that, despite broad similarities, there are some differences in the estimates. However, whereas Murray et al. suggest that their approach can unequivocally be preferred, we believe that it is important to understand the differences that exist between the two sets of estimates in order to know how to interpret their respective findings. Given the importance attached to estimates in global health, we also reflect upon alternative ways in which country estimates can be generated.

Different approaches

The differences between the Murray et al. and the UNAIDS approaches can be summarised by the data upon which the estimates are based. UNAIDS derives estimates using data on HIV prevalence in most settings with generalised epidemics and some settings with concentrated epidemics (Box 1). A model is fit to these data in order to generate estimates of incidence, deaths and other quantities. In some settings (mostly high-income countries), estimates are configured to align with case-report surveillance in others. Estimates are computed by countries, with technical assistance from UNAIDS, and results are tested for their consistency with local surveillance and program data.

Box 1.

no caption available.

In contrast, Murray et al. base most of their estimates on UNAIDS outputs that are then combined with their own estimates of all-cause and cause-specific death rates. Candidate epidemiological trajectories for a particular country are generated, based on previously generated results by UNAIDS but with Murray et al. applying their own assumptions for, among other factors, HIV survival rates and the distribution of incidence by age and sex. Final estimates are generated by selecting from among the candidate trajectories those that imply a better agreement with their estimates of deaths. Estimates of mortality rates are based on data from vital registration systems where possible, and from other available data and model-based extrapolations elsewhere. In lower-level epidemic settings wherein AIDS cause-specific mortality is used, there is some reclassification of deaths that is intended to account for the misassignment of AIDS-related deaths to another cause.

Thus, the UNAIDS and the Murray et al. estimates are not independent, with the latter estimates relying on the same epidemiologic models used by UNAIDS but with the additional influence of their own estimates of mortality.

Different results

These different approaches give reasonably similar results, as has been highlighted previously [3]. However, there are interesting differences: Murray et al. estimate that there are fewer PLHIV than UNAIDS has reported, and Murray et al. estimates suggest that recent reductions in AIDS deaths have been more modest than UNAIDS has reported. We consider each of these in turn.

Differences in the magnitude of the HIV epidemic

For 2013, the number of PLHIV is 35 million in the UNAIDS estimates and 29 million in Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation estimates. The 6 million person difference is 17% of the UNAIDS total.

However, in the regions with the largest epidemics (Southern, Eastern, Central and West Africa), where the greatest attention of donors is focussed, the difference is small; UNAIDS estimates 25 million PLHIV, whereas Murray et al. estimate 23 million. This accounts for just less than one third of the difference in the overall totals of PLHIV globally.

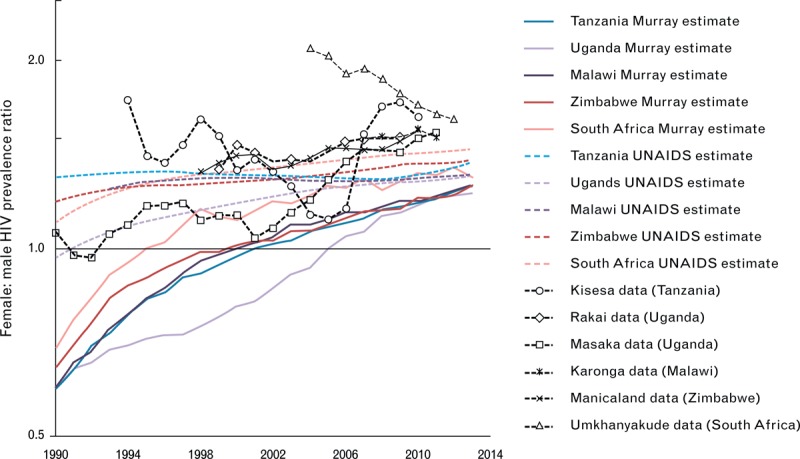

In these areas with the largest epidemics, however, there are important differences in the historic trajectory of new infection and deaths, despite an overall agreement in PLHIV. Numbers of deaths are smaller in the Murray et al. estimates. This is likely because of different assumptions made about natural HIV survival [i.e. without antiretroviral therapy (ART)]. UNAIDS bases its assumptions on direct empirical measurements from long-running population-based cohort studies [4] [11.1 years (8.7–14.2 years) for Eastern African cohorts and 11.6 years (9.8–13.7 years) for Southern Africa] for 25–29-year olds, which are also consistent with historical cohort studies in Europe, North America and Australia [5] (10.9 years (10.6–11.3 years) for 25–34-year olds)]. These same survival times are applied across epidemic settings. Murray et al. allow median survival to vary between 3.6 and 29.5 years, based on a new meta-analysis, and permit survival rates to vary by sex, age and country in any manner in order to best fit estimates of all-cause mortality. Precedence is therefore given to their estimates of deaths, which, in most of these countries, are modelled based on indirect data sources, and therefore, potentially subject to errors. This could lead to unsubstantiated differences in survival rates across age, sex and country. This survival schedule selection procedure may also have contributed to the estimate by the Murray et al. that during the 1990s HIV prevalence was higher among men than in women. This has not been found in data from cohort studies from that time [6–13] (Fig. 1), although the comparison between estimates and data is somewhat complicated by the different age groups for which results are available.

Fig. 1.

Female-to-male prevalence ratios in the Murray et al. estimates [ratio of numbers of women-to-men people living with HIV (PLHIV), all ages] (solid coloured lines), in UNAIDS estimates (ratio of numbers of women to men PLHIV, all ages) (dashed colour lines) and measurements in available population level survey data among 15–49-year olds (markers with grey connecting lines).

Note that the estimates based on data rely on an interpolation to provide a continuous time-series.

There are greater proportionate differences between the Murray et al. and UNAIDS estimates for other countries outside Africa. Across North America, Europe, Central Asia and Australasia, the total discrepancy in PLHIV is 1.7 million (UNAIDS PLHIV estimate 3.4 million vs. Murray et al., 1.7 million). This too accounts for almost one third on the total global difference in the estimates. In these regions, the epidemics are concentrated among those at greatest risk of infection and Murray et al. assert that these ‘concentrated epidemics have been systematically overestimated by a factor on average of more than two’. Fortunately, however, many of these countries have strong case-based surveillance data that can be used to investigate these differences.

Numbers of new diagnoses can be considered as a rough, time-lagged proxy for HIV incidence. Broadly, number of new diagnoses are expected to underestimate new infections (as not all infected persons will seek HIV testing), but the number of cases could overstate new infections if there is double counting of patients (caused by, for instance, their presentation at multiple sites) or if many of the new cases were actually acquired abroad (for instance, among migrants from higher prevalence countries). In practice, in most places, measures are taken in order to avoid double counting [16].

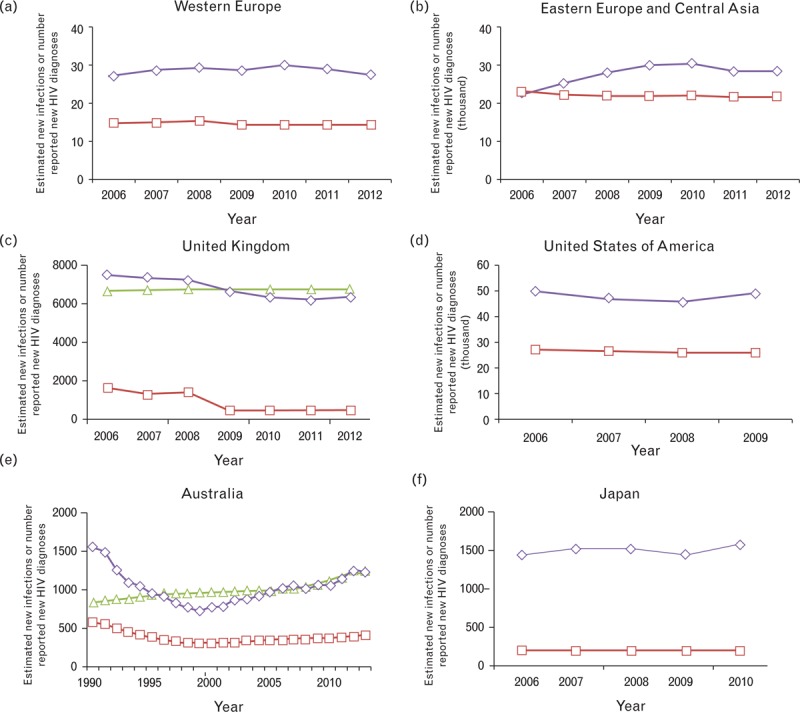

In Table 1, countries in Europe and North America are ranked by the number of newly diagnosed HIV infections they report. In general, Murray et al. estimates are substantially less than the numbers of new cases reported in a country, whereas UNAIDS estimates tend to be greater. These differences are consistent over time (Fig. 2a–d).

Table 1.

Countries with good case-based reporting systems in Europe, United States of America, Canada and Russian Federation in 2012 (except USA, for which data are for 2011).

| Country | Rank in number of newly diagnosed HIV infections | Reported newly diagnosed HIV infections | Murray et al. estimated new infections | Relative difference between Murray et al. new infection estimate and reported newly diagnosed HIV cases (%) | UNAIDS estimate | Relative difference between UNAIDS estimate and reported newly diagnosed HIV cases (%) |

| Russian Federation | 1 | 75 708 | 36 600 | −52 | ||

| United States of America | 2 | 49 273 | 26 200 | −47 | ||

| Ukraine | 3 | 16 872 | 13 100 | −22 | 8604 | −49 |

| United Kingdom | 4 | 6358 | 470 | −93 | 6755 | 6 |

| France | 5 | 4066 | 2430 | −40 | 6856 | 69 |

| Italy | 6 | 3898 | 3050 | −22 | ||

| Spain | 7 | 3210 | 2210 | −31 | 3262 | 2 |

| Germany | 8 | 2953 | 1710 | −42 | ||

| Canada | 9 | 2062 | 850 | −59 | 3122 | 51 |

| Kazakhstan | 10 | 2014 | 2700 | 34 | ||

| Belgium | 11 | 1227 | 213 | −83 | ||

| Belarus | 12 | 1223 | 720 | −41 | 2728 | 123 |

| Poland | 13 | 1085 | 470 | −57 | ||

| Turkey | 14 | 1068 | 590 | −45 | ||

| Greece | 15 | 1059 | 52 | −95 | ||

| Netherlands | 16 | 976 | 280 | −71 | ||

| Tajikistan | 17 | 814 | 790 | −3 | 1668 | 105 |

| Republic of Moldova | 18 | 757 | 560 | −26 | 1392 | 84 |

| Portugal | 19 | 721 | 2390 | 231 | ||

| Kyrgyzstan | 20 | 700 | 820 | 17 | 870 | 24 |

| Switzerland | 21 | 643 | 350 | −46 | 698 | 9 |

| Georgia | 22 | 526 | 67 | −87 | 639 | 21 |

| Azerbaijan | 23 | 517 | 403 | −22 | 1163 | 125 |

| Romania | 24 | 489 | 300 | −39 | 608 | 24 |

| Israel | 25 | 487 | 109 | −78 | ||

| Sweden | 26 | 363 | 60 | −83 | ||

| Ireland | 27 | 339 | 57 | −83 | ||

| Latvia | 28 | 339 | 260 | −23 | ||

| Estonia | 29 | 315 | 98 | −69 | ||

| Austria | 30 | 306 | 540 | 76 |

Countries are ranked by their reported number of newly diagnosed HIV infections (top 30), a proxy for new HIV infections. Some Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates, denoted by ‘…’, are not published by UNAIDS but UNAIDS’ files are configured to match incidence to numbers of reported cases. Relative differences are computed as ‘Estimate – Reported New Cases/Reported New Cases’. Source [1,14,15,18]. UNAIDS, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS.

Fig. 2.

Comparison between Murray et al. and Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) estimates of new infections with case-report data in (a) Western Europe, (b) Eastern Europe and Central Asia, (c) United Kingdom, (d) United States of America, (e) Australia and (f) Japan.

Red line with squares is the estimate of new HIV infections from Murray et al.; green line with triangles is UNAIDS estimate of new infections; purple line with diamonds is the country-reported number of new HIV diagnoses. UNAIDS estimates are not published for Japan, the United States of America or some European countries. Source: [1,14,16,18,19].

Some differences are quite extreme. For example, in the UK, the Murray et al. estimate for the number of new HIV infections among men (350 in 2010) is almost seven-fold less than the estimate from the United Kingdom Health Protection Agency for just MSM in England and Wales (∼2300) [17].

Differences are also found in other countries with robust surveillance systems, such as Australia and Japan (Fig. 2e and f).

These comparisons do not support the contention of Murray et al. that their lower estimates of new infections or PLHIV are more likely to be correct in these regions, and perhaps others where additional data to cross-check the estimates are not available. The UNAIDS estimate are potentially consistent with not all newly infected persons being diagnosed, but it is not possible to confirm the accuracy of the estimates with these data.

The remainder of the global differences in the two estimates of PLHIV comes largely from Asia Pacific (1.7 million discrepancy) and Latin America (630 000 discrepancy). In these settings, epidemics are also concentrated and although there are less well developed systems for reporting cases, many countries are assumed to have good vital registration systems. In the regions where vital registration systems are good (upon which Murray et al. estimates are based) and estimates of prevalence and size of risk groups (upon which UNAIDS estimate are based) are thought to be less reliable, we agree that estimates should rely more on mortality data in addition to the epidemiological data. UNAIDS is already doing this for Argentina, Mexico and Brazil in the latest round of estimates [20]. Overall, the discrepancy in the 2013 numbers of new infections, PLHIV and deaths, in those countries in Latin America and Asia with concentrated epidemics but good vital registration systems, amounts to 60 000 fewer new infections, 1.1 million fewer PLHIV and 55 000 fewer AIDS deaths in the Murray et al. estimates compared with UNAIDS, equivalent to about 3% of the overall UNAIDS estimates for each indicator.

Nevertheless, other data – where they exist – in those countries with good vital registration systems that have not been incorporated into the Murray et al., estimates can provide a useful check on derived estimates. For instance, there have been two HIV prevalence surveys in Dominican Republic, in 2002 and 2007 (samples sizes 26 217 and 55 170, respectively). Multiplying prevalence estimates from those (1 and 0.8%, respectively [21]) by corresponding population sizes estimates [22] gives estimates of PLHIV aged 15–49 years of 46 000 and 40 000, respectively. Comparatively, Murray et al. estimates for PLHIV of all ages, at 17 500 and 19 600, respectively, are less than half these values. In contrast, the UNAIDS estimates for PLHIV of all ages, at 70 000 and 55 000, are greater which may be partly explained by children and adults over 50 years living with HIV. In Brazil, Murray et al. estimate 396 000 (263 000–515 000) PLHIV, compared with the UNAIDS estimate of 726 000 (664 000–808 000); but the Brazilian government reports [23] a total of 436 000 PLHIV either in pre-ART care or on ART – more than the point estimate in Murray et al.

Arguably, these findings do not support the contention of Murray et al., that their estimates are more likely to be correct than any other estimates, even in these settings where appropriate prevalence data are relatively sparse.

Difference in view of mortality trends over time

UNAIDS and Murray et al. estimates show that ART has driven large declines in mortality, the most dramatic being in southern and eastern Africa. However, the Murray et al. estimates indicate a somewhat more modest reduction in deaths than do those from UNAIDS.

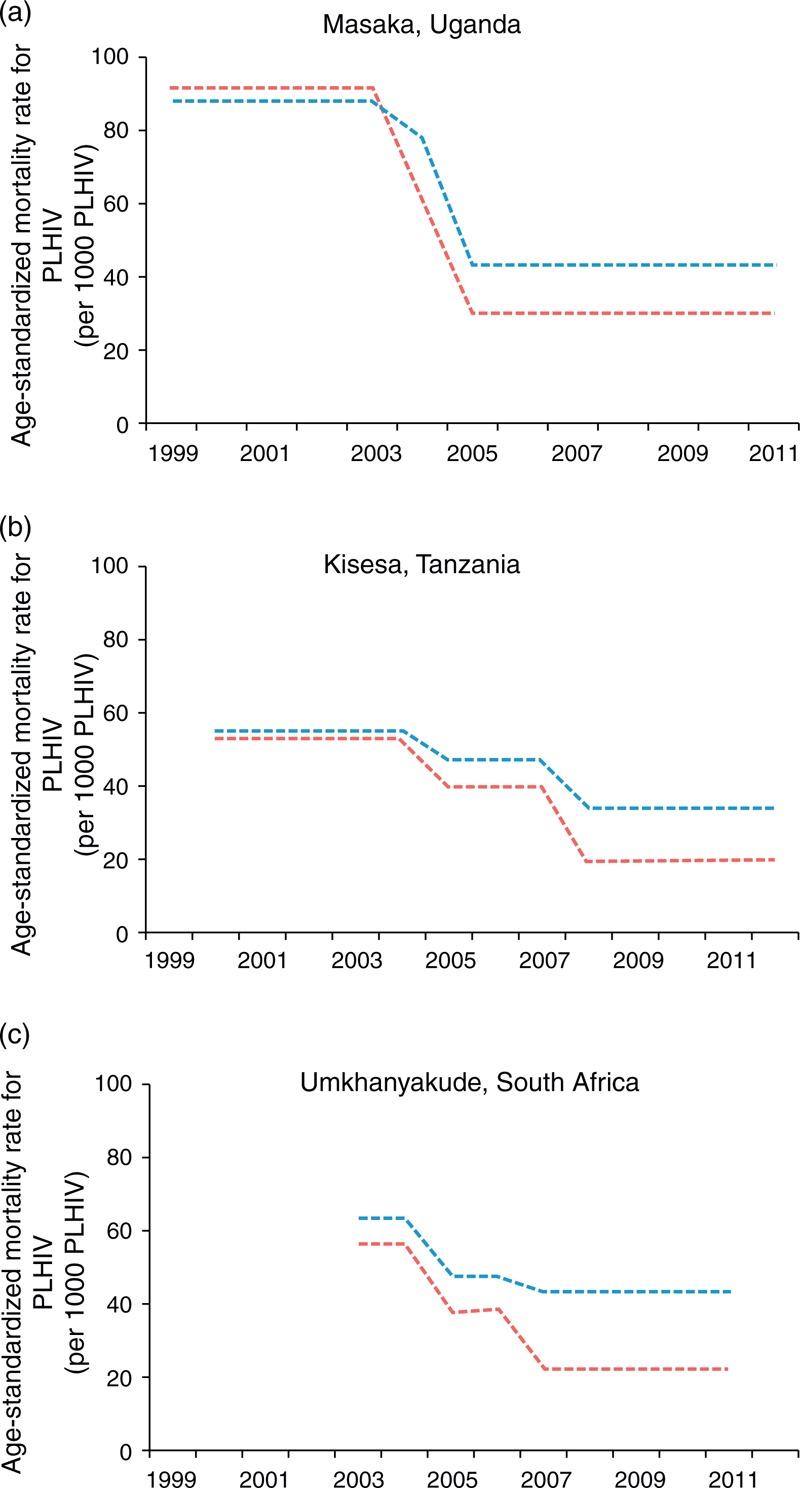

Again, there are direct empirical data from population cohorts in several settings in Africa that can be used to assess the impact of ART (Fig. 3a–c). These data were not incorporated into either the Murray et al. or the UNAIDS estimates. These cohort data do indeed exhibit strong reductions in the rate of AIDS deaths – falls on the order of 50% reductions in mortality among PLHIV – consistent in magnitude with the decline reported by UNAIDS. It maybe the case, however, that the intensively researched populations have benefitted by a greater provision of ART than is available in the rest of their countries, and so could have experienced larger mortality reductions than at the national level.

Fig. 3.

Empirical measures of death rates among people living with HIV from cohort studies in (a) Uganda, (b) Tanzania and (c) South Africa.

Rates of men are in blue and rates in women are in red. These are the reported age-standardized mortality rates among HIV-infected individuals for three periods: pre-ART, ART scale-up, and post-ART scale-up, plotted as uniform over the calendar time to which those definitions correspond [24]. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Conclusion

It is useful and welcome that two different methods have been applied to estimate the same quantities. Most striking is the overall similarity in the estimates, rather than the differences – both show approximately 30 million people worldwide living with HIV and that enormous gains in life years have been generated by ART. It is inevitable that differences in the methods, related though they are, will lead to some differences in the results. We see this as an opportunity to investigate and learn from how different approaches and assumptions can affect results. Although we do not believe either set of estimates will be uniformly correct, our further investigations with additional empirical data do not lend support to the central contention of Murray et al. that their estimates should necessarily be preferred over others. Rather, we find no evidence that either set of estimates can be considered more accurate than the other, and indeed both will – in places – exhibit discrepancies with other data.

It is a significant and highly valuable contribution of Murray et al., in that study and in their previous work [25], to have produced estimates of breakdowns by mortality cause. We agree that leveraging mortality data can strengthen estimates of HIV, and other diseases, where those data are available. However, we also believe that estimation methods should appropriately balance this with information from other epidemiological data sources, including prevalence data, case-based surveillance and program data. Without doing so, as we have described, estimates can be generated that are clearly at odds with robust data available in the countries, and such contradictions will not assist planners in their evaluation of their interventions or in setting priorities. Future work, for all those generating estimates in HIV, should seek a fuller integration of these disparate data sources. For its part, UNAIDS is seeking to include data from tests for recent infection [26], case reports, vital registration [27], programmes for prevention of mother-to-child transmission and more details on ART programmes in future estimates (audits of ART numbers, viral load measurements in population-based surveys and country-level data on survival and retention on ART), while also continuing to confront estimates with empirical data to check the validity of its methods [28,29].

All methods for producing estimates have their limitations. In this review, we have not attempted to be systematic in comparing the two sets of estimates, but have rather sought to identify and examine the largest and most important differences. There will be examples in both sets of estimates which seem to be falsified by other data – which is a sign that neither set can be considered perfect. This also underlines the difficulty in generating estimates. The reliance, for instance, of the UNAIDS method on the reported numbers on ART and its assumptions of a uniform impact of ART on transmission and mortality risk may make it vulnerable to overestimating the impact of ART, where programs are not able to deliver the same standard of care as has been reported in studies or if there are any errors in reports of numbers on ART. The reliance, exclusively until recently, on the consistency in prevalence data in concentrated epidemics, over time and of the veracity of empirically derived, but nevertheless uncertain, estimates of sizes of key populations [30] could also lead to biased results. Nevertheless, the UNAIDS numbers and trends in new infections and deaths seem directionally consistent with other independent empirical data from cohort studies, for example especially in the large generalised epidemics. Meanwhile, the Murray et al. method suffers, by necessity, on a reliance on uncertain models for mortality in most of the settings with largest epidemics, and elsewhere is subject to questions about the extent to which verbal autopsy data can be relied upon [31,32] and the difficulties of adjusting for misclassification of death caused by AIDS.

There is increasingly a focus on country leaders taking ownership of HIV programmes, and other public health programmes, and there have been many calls for the greater use of data in decision making. It is therefore extremely helpful if the generation and use of data for public decision making are led by countries. In a recent editorial, Atun [33] calls for transparency and sharing of the methods and data used to make estimates and an emerging theme in programme planning and evaluating is understanding process at a finer spatial scale [34]. In this context, the UNAIDS approach of empowering countries to construct their own estimates, increasingly at sub-national level [35,36], with guidance on appropriate methods and assumptions, with most datasets and models freely accessible and continuously subject to peer review, seems well placed. On the other hand, there are advantages to synthesising data from multiple countries together in order to produce an internally consistent view of global health across disease and countries. These different approaches are complementary and the value that they each provide to country programme planners can be enhanced through coordination and data sharing.

We may stand at the edge of a revolution in data sharing in global health, as The United States President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief, The Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and other agencies open up their records, and countries and international agencies increase their efforts to distribute epidemiological data [37]. This is an exciting time, and estimates and evaluations will be strengthened through an iterative scientific investigative process that should result in meaningful gains in reliable information for country programme planners.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Jeffrey Eaton for helpful comments on drafts of this review. T.B.H. thanks the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, UNAIDS, the Rush Foundation and the World Bank for funding support.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Authors are members of the UNAIDS Reference Group on Estimates, Modelling, Projections.

References

- 1.Murray CJ, Ortblad KF, Guinovart C, Lim SS, Wolock TM, Roberts DA, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence and mortality for HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria during 1990–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lancet 2014; 384:1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.UNAIDS, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). The Gap Report. 2014; ISBN 978-92-9253-062-4. UNAIDS/JC2656 (English original, July 2014, updated September 2014) http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/UNAIDS_Gap_rep ort_en.pdf. [Accessed 12 August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sidibe M, Dybul M, Birx D. MDG 6 and beyond: from halting and reversing AIDS to ending the epidemic. Lancet 2014; 384:935–936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Todd J, Glynn JR, Marston M, Lutalo T, Biraro S, Mwita W, et al. Time from HIV seroconversion to death: a collaborative analysis of eight studies in six low and middle-income countries before highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2007; 21 Suppl 6:S55–S63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Time from HIV-1 seroconversion to AIDS and death before widespread use of highly-active antiretroviral therapy: a collaborative re-analysis. Collaborative Group on AIDS Incubation and HIV Survival ∗ including the CASCADE EU Concerted Action. Lancet 2000; 355:1131–1137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boerma JT, Urassa M, Senkoro K, Klokke A, Ngweshemi JZ. Spread of HIV infection in a rural area of Tanzania. AIDS 1999; 13:1233–1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Glynn JR, Ponnighaus J, Crampin AC, Sibande F, Sichali L, Nkhosa P, et al. The development of the HIV epidemic in Karonga District, Malawi. AIDS 2001; 15:2025–2029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crampin AC, Glynn JR, Ngwira BM, Mwaungulu FD, Ponnighaus JM, Warndorff DK, et al. Trends and measurement of HIV prevalence in northern Malawi. AIDS 2003; 17:1817–1825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gregson S, Mason PR, Garnett GP, Zhuwau T, Nyamukapa CA, Anderson RM, et al. A rural HIV epidemic in Zimbabwe? Findings from a population-based survey. Int J STD AIDS 2001; 12:189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamali A, Carpenter LM, Whitworth JA, Pool R, Ruberantwari A, Ojwiya A. Seven-year trends in HIV-1 infection rates, and changes in sexual behaviour, among adults in rural Uganda. AIDS 2000; 14:427–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mwaluko G, Urassa M, Isingo R, Zaba B, Boerma JT. Trends in HIV and sexual behaviour in a longitudinal study in a rural population in Tanzania, 1994-2000. AIDS 2003; 17:2645–2651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boerma JT, Gregson S, Nyamukapa C, Urassa M. Understanding the uneven spread of HIV within Africa: comparative study of biologic, behavioral, and contextual factors in rural populations in Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Sex Transm Dis 2003; 30:779–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wambura M, Urassa M, Isingo R, Ndege M, Marston M, Slaymaker E, et al. HIV prevalence and incidence in rural Tanzania: results from 10 years of follow-up in an open-cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2007; 46:616–623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control/WHO Regional Office for Europe. HIV/AIDS surveillance in Europe. 2012; pp. 1–87. ISBN 978-92-9193-541-3. ISSN 1831-9483. http://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications/Publications/hiv-aids-surveillance-report-2012-20131127.pdf. [Accessed 12 August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Surveillance and Epidemiology Division, Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada. HIV and AIDS in Canada: Surveillance Report to December 31, 2012. 2013; ISSN: 1701-4158. Pub.: 130452. http://www.catie.ca/sites/default/files/HIV-AIDS-Surveillence-in-Canada-2012-EN-FINAL.pdf. [Accessed 12 August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson D, McDonald A, Zhang L, Mao L. The Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia. Annual Surveillance Report 2014 HIV Supplement. The Kirby Institute, UNSW, NSW 2052. http://kirby.unsw.edu.au/sites/default/files/hiv/resources/HIVASRsuppl2014_online.pdf [Accessed 1 August 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Birrell PJ, Gill ON, Delpech VC, Brown AE, Desai S, Chadborn TR, et al. HIV incidence in men who have sex with men in England and Wales 2001-10: a nationwide population study. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:313–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stacy Cohen, Xiaohong Hu, Daxa Shah, Anne Patala, Sabitha Dasari, Anna Satcher Johnson, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Surveillance Report, 2011; vol. 23 Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, Georgia: February 2013. Report number: CS-228642. http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/ [Accessed 12 August 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Japan Annual Report. AIDS Surveillance Committee, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; 2013. Japan AIDS Surveillance Committee, 23 May 2014. http://api-net.jfap.or.jp/status/2013/13nenpo/coment.pdf [Accessed 12 August 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stover J, Gopalappa C, Mahy M, Doherty MC, Easterbrook PJ, Weiler G, Ghys PD. The impact and cost of the 2013 WHO recommendations on eligibility for antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 2014; 28 Suppl 2:S225–S230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. [[Accessed 14 August 2014]]; http://www.statcompiler.com. [Google Scholar]

- 22. [[Accessed 14 August 2014]]; http://esa.un.org/unpd/wpp/ [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sara Alves, Sergio D’Avila, Marcelo Araújo de Freitas, Cíntia Freitas, Ana Roberta Pati Pascom, Gerson Fernando Pereira, et al. Progress Report on the Brazilian Response to HIV/AIDS (2010 2011). Brazil Ministry of Health Report, Health. Surveillance Secretariat. Department of STD, AIDS and Viral Hepatitis. http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/UNGASS_2012_ingles_rev_08jun.pdf [Accessed 14 August 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Slaymaker E, Todd J, Marston M, Calvert C, Michael D, Nakiyingi-Miiro J, et al. How have ART treatment programmes changed the patterns of excess mortality in people living with HIV? Estimates from four countries in East and Southern Africa. Glob Health Action 2014; 7:22789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lozano R, Naghavi M, Foreman K, Lim S, Shibuya K, Aboyans V, et al. Global and regional mortality from 235 causes of death for 20 age groups in 1990 and 2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2012; 380:2095–2128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bao L, Ye J, Hallett TB. Incorporating incidence information within the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection Package framework: a study based on simulated incidence assay data. AIDS 2014; 28 Suppl 4:S515–S522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vegsa JF, Cori A, van Sighem A, Hallett TB. Estimating HIV incidence from case-report data: method and an application in Colombia. AIDS 2014; 28 Suppl 4:S489–S496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Samuel Oji Oti, Marilyn Wamukoya, Mary Mahy, Catherine Kyobutungi. InterVA versus Spectrum: how comparable are they in estimating AIDS mortality patterns in Nairobi's informal settlements? Glob Health Action 2013; 6:21638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michael D, Kanjala C, Calvert C, Pretorius C, Wringe A, Todd J, et al. Does the Spectrum model accurately predict trends in adult mortality? Evaluation of model estimates using empirical data from a rural HIV community cohort study in North-Western Tanzania. Glob Health Action 2014; 7:21783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UNAIDS/WHO Working Group on Global HIV/AIDS and STI Surveillance. Guidelines on estimating the size of populations most at risk to HIV, 2011. World Health Organization and UNAIDS; ISBN 978 92 4 159958 0 (NLM classification: WC 503.41). http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2011/2011_estimating_populations_en.pdf [Accessed 26 June 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glynn JR, Calvert C, Price A, Chihana M, Kachiwanda L, Mboma S, et al. Measuring causes of adult mortality in rural northern Malawi over a decade of change. Glob Health Action 2014; 7:23621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopman B, Cook A, Smith J, Chawira G, Urassa M, Kumogola Y, et al. Verbal autopsy can consistently measure AIDS mortality: a validation study in Tanzania and Zimbabwe. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 2010; 64:330–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Atun R. Time for a revolution in reporting of global health data. Lancet 2014; 384:937–938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNAIDS, UNAIDS. Local Epidemics Issues Brief. 2014; pp. 1–52. UNAIDS / JC2559/1/E. ISBN 978-92-9253-039-6. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2014/JC2559_local-epidemics_en.pdf. [Accessed 14 August 2014]. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahy M, Nzima M, Ogungbemi MK, Ogbang DA, Morka MC, Stover J. Redefining the HIV epidemic in Nigeria: from national to state level. AIDS 2014; 28 Suppl 4:S461–S467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Larmarange J, Bendaud V. HIV estimates at second subnational level from national population-based surveys. AIDS 2014; 28 Suppl 4:S469–S476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Data Watch: Closing a Persistent Gap in the AIDS Response: A new approach to tracking data to guide the AIDS response; An update on the Action Agenda to End AIDS. amfAR, AVAC; 2014. http://www.avac.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/DataWatchAugust2014.pdf [Accessed 1 September 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marsh K, Mahy M, Salomon JA, Hogan DR. Assessing and adjusting for differences between HIV prevalence estimates derived from national population-based surveys and antenatal care surveillance, with applications for Spectrum 2013. AIDS 2014; 28 Suppl 4:S497–S505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hogan DR, Salomon JA. Spline-based modelling of trends in the force of HIV infection, with application to the UNAIDS Estimation and Projection Package. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88 Suppl 2:i52–i57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bao L. A new infectious disease model for estimating and projecting HIV/AIDS epidemics. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88 Suppl 2:i58–i64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reference Group on Estimates, Modelling and Projections, Imperial College London: Bao L, Bennett E, Brown T, Calleja T, Case K, Eaton J, et al. Report and Recommendations: Technical refinements for Spectrum 2013: December 2012. UNAIDS January 2013. http://www.epidem.org/sites/default/files/reports/TechnicalRefinementsforSpectrum%202013.pdf [Accessed 23 June 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Population Prospect. 2012 Revision. United Nations - Department of Economic and Social Affairs - Population Division. Population Division Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations 2012. ISBN 978-92-1-151504-6. http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/trends/WPP2012_Wallchart.pdf [Accessed 1 August 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Aceijas C, Friedman S, Cooper H, Wiessing L, Stimson G, Hickman M. Estimates of injecting drug users at the national and local level in developing and transitional countries, and gender and age distribution. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82 Suppl 3:iii10–iii17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cáceres C, Konda K, Pecheny M, Chatterjee A, Lyerla R. Estimating the number of men who have sex with men in low and middle income countries. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82 Suppl 3:iii3–iii9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Carael M, Slaymaker E, Lyerla R, Sarkar S. Clients of sex workers in different regions of the world: hard to count. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82 Suppl 3:iii26–iii33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vandepitte J, Lyerla R, Dallabetta G, Crabbe F, Alary M, Buve A. Estimates of the number of female sex workers in different regions of the world. Sex Transm Infect 2006; 82 Suppl 3:iii18–iii25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yiannoutsos CT, Johnson LF, Boulle A, Musick BS, Gsponer T, Balestre E, et al. Estimated mortality of adult HIV-infected patients starting treatment with combination antiretroviral therapy. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88 Suppl 2:i33–i43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rollins N, Mahy M, Becquet R, Kuhn L, Creek T, Mofenson L. Estimates of peripartum and postnatal mother-to-child transmission probabilities of HIV for use in Spectrum and other population-based models. Sex Transm Infect 2012; 88 Suppl 2:i44–i51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]