Abstract

We present axial plane optical microscopy (APOM) that can, in contrast to conventional microscopy, directly image a sample's cross-section parallel to the optical axis of an objective lens without scanning. APOM combined with conventional microscopy simultaneously provides two orthogonal images of a 3D sample. More importantly, APOM uses only a single lens near the sample to achieve selective-plane illumination microscopy, as we demonstrated by three-dimensional (3D) imaging of fluorescent pollens and brain slices. This technique allows fast, high-contrast, and convenient 3D imaging of structures that are hundreds of microns beneath the surfaces of large biological tissues.

Aconventional wide-field optical microscope captures 2D images of samples' cross-sections within the objective's thin focal plane normal to its optical axis1. For applications such as imaging cortical neurons of a living brain2 or studying mechanotransduction3,4 and mechanical properties of cells5, however, the principal plane of interest is often perpendicular to the sample surface. Currently, axial plane images (parallel to the objective lens's optical axis) are typically obtained with a confocal microscope by scanning its objective lens, intrinsically limiting the temporal resolution6. In principle, axial plane images can also be obtained by digital holographic microscopy7,8,9, which requires coherent light signals and is thus not applicable to incoherent fluorescence signals, critically limiting its applications in biology. The recently invented oblique plane microscopy10,11,12 can image out-of-focus planes, but has been limited to small tilting angles and cannot image axial planes directly due to the mechanical constraint of its optical configuration. Recently, a novel slit scanning confocal microscope that images the axial plane by combining remote focusing and synchronously scanning two small mirrors was developed13. It increased the scanning speed in the axial direction because the two small mirrors are lighter than the objective lens and are not in contact with the sample13. However, it still relies on scanning to form a 2D image. In this letter, we report an optical method, APOM, that directly images the axial cross-section of a sample without scanning. The APOM is fully compatible with conventional wide-field microscopes, enabling fast, simultaneous acquisition of orthogonal combination of wide-field images of 3D samples. More importantly, the APOM allows light-sheet illumination and optical signal detection through the same objective lens, as we demonstrated by 3D imaging of fluorescent pollens and mouse brain slices. This fast, high-contrast, and convenient imaging approach does not require special sample preparation, and is particularly suitable for imaging structures that are hundreds of micrometers beneath the surface of large biological samples such as living brains.

Results

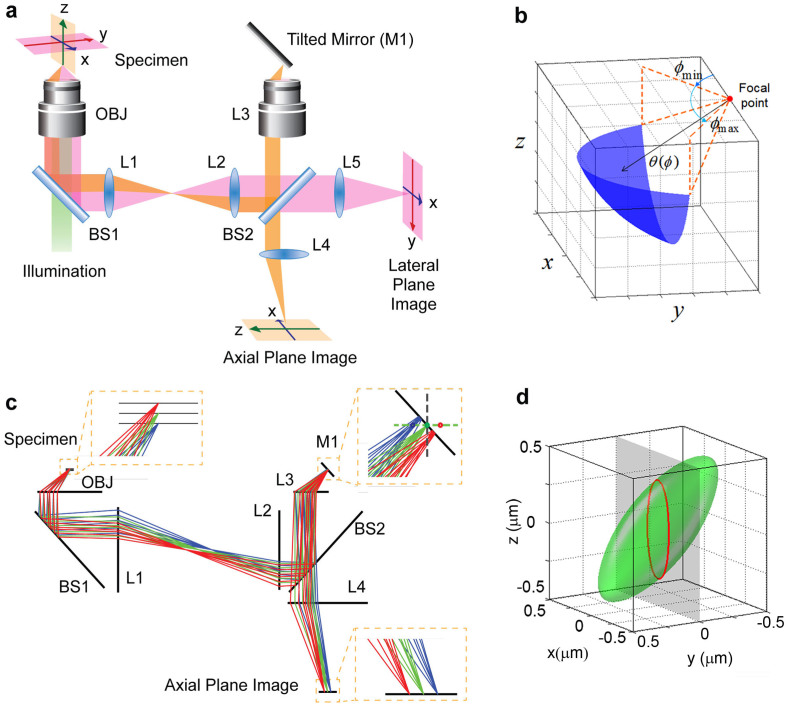

As shown in Fig. 1a, we use one objective lens (OBJ, 100×, NA = 1.4, oil immersion) near the sample for both illumination and image collection, and an identical remote lens (L3) at about half meter away from the sample for forming a 3D intermediate optical image at its focus. A 45°-tilted mirror (M1) placed at the focus of L3 transforms the axial cross-section to the lateral cross-section of this remote lens. The axial plane image of the sample is therefore formed at the image plane of the remote lens and collected by a CCD camera (Fig. 1c). This direct optical imaging method does not require scanning or computation, and is thus inherently fast. In principle, the mirror M1 can be placed at an arbitrary angle between 0° and 45°, and be rotated around the optical axis of the remote objective to achieve arbitrary plane imaging. In the current experimental setup, the remote lens L3 is identical to the objective lens OBJ in order to form a 3D image without the spherical aberration for optical signals from object points outside the focal plane of OBJ14,15,16. Because the working distance of the high NA objective that we used is small (about 0.13 mm), only the edge of the 45° mirror is used. This requires the mirror to have a high quality reflecting surface as well as a straight edge. We create such mirrors by coating aluminum on cleaved silicon wafers with an atomically straight edge.

Figure 1. Optical setup and principle of the APOM.

(a) Schematic of the APOM setup. The APOM contains one objective lens (OBJ) near the sample for both illumination and signal collection, and a remote lens (L3), about 60 cm away from the sample in optical path, to form an intermediate aberration-free 3D image near its focal point. This intermediate 3D image is reflected by a mirror (M1) tilted by 45° with respect to the optical axis of L3. Part of the reflected light is recollected by L3 and forms an axial plane image of the sample at camera's CCD plane. At the same time, the light directly transmitting through BS2 forms a lateral plane image of the sample. BS1 and BS2 are beam splitters. L1, L2, L4, L5 are achromatic tube lenses. (b) The 3D effective pupil area of APOM in remote lens L3. θ: polar angle, φ: azimuthal angle. (c) Ray tracing simulation of APOM. (d) Calculated 3D PSF of APOM. The green surface is the iso-surface at the half peak intensity of the 3D PSF of APOM. The red contour is the x-z cross section of the PSF iso-surface at y = 0, which directly shows the PSF of axial plane imaging.

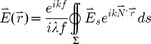

The APOM allows direct high-resolution axial plane imaging of a sample over a large field of view (Fig. 1). To understand the resolution limit of APOM, we have calculated the intensity point spread function (PSF) of APOM with a vector diffraction theory that treats a high NA optical system more accurately than scalar theories (Fig. 1d)17,18,19,20. The classical scalar diffraction theory estimates PSF with Fresnel approximation, which is only applicable to low NA systems and will overestimate the PSF in the axial direction by about 40% for a conventional microscope with a NA = 1.4 oil immersion lens19. The scalar Debye theory does not make the paraxial approximation, but still neglects the vectorial nature of the light that is important for a high NA system20. Since the NA of the objective lens in our system is very high (NA = 1.4), we calculate the PSF with a vector theory that does not use paraxial approximation and considers the polarization of electromagnetic waves17,20. The electric field  at an observation point

at an observation point  near the focus of an objective lens can be calculated by the vectorial Kirchhoff integral, derived from a vector analogue of the Green's second identity. When the focal length of the objective lens is much larger than the wavelength of the collected light, and the observation point is close to the focal point compared with the focal length, the vectorial Kirchhoff integral is simplified to the vectorial Debye integral, where

near the focus of an objective lens can be calculated by the vectorial Kirchhoff integral, derived from a vector analogue of the Green's second identity. When the focal length of the objective lens is much larger than the wavelength of the collected light, and the observation point is close to the focal point compared with the focal length, the vectorial Kirchhoff integral is simplified to the vectorial Debye integral, where  can be calculated by integrating the electric field

can be calculated by integrating the electric field  at the wavefront surface Σ over the entire exit pupil (Fig. 1b) of an imaging system20:

at the wavefront surface Σ over the entire exit pupil (Fig. 1b) of an imaging system20:  . Here k is the wave number in the medium, λ is the wavelength in the medium, f is the distance between the focal point and the wavefront surface Σ, and

. Here k is the wave number in the medium, λ is the wavelength in the medium, f is the distance between the focal point and the wavefront surface Σ, and  is a unit ray vector normal to the wavefront. The 3D effective pupil area of APOM is shown in Fig. 1b. Due to the signal loss at the 45° mirror, the effective pupil area is not symmetric, giving rise to an asymmetric PSF. For comparison, we also calculated the PSF of conventional microscopy along the z-axis, although conventional microscopy cannot image the axial plane directly (Supplementary Fig. S1). Note that the PSF of conventional microscopy is also different along the z-axis and the x-axis.

is a unit ray vector normal to the wavefront. The 3D effective pupil area of APOM is shown in Fig. 1b. Due to the signal loss at the 45° mirror, the effective pupil area is not symmetric, giving rise to an asymmetric PSF. For comparison, we also calculated the PSF of conventional microscopy along the z-axis, although conventional microscopy cannot image the axial plane directly (Supplementary Fig. S1). Note that the PSF of conventional microscopy is also different along the z-axis and the x-axis.

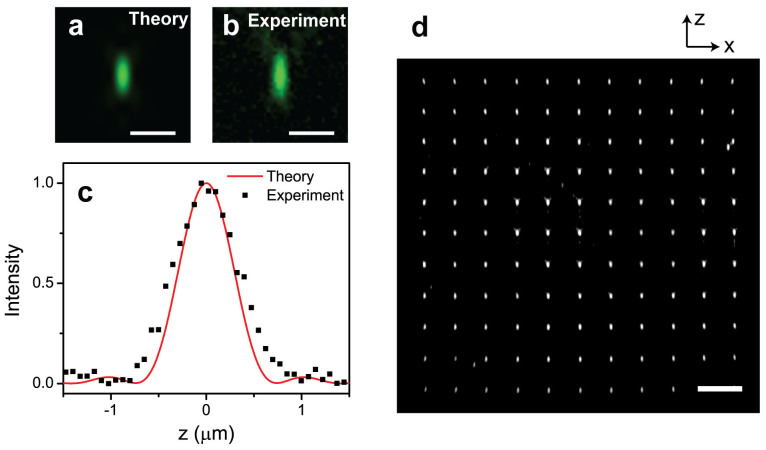

The calculated full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the PSF of APOM in the axial direction is almost the same as that of conventional microscopy in the axial direction for high NA objectives. When the NA of both OBJ and L3 is 1.4, as used in the current experiment, the calculated FWHM of the PSF of APOM is 641 nm along the z-axis and 255 nm along the x-axis (Fig. 2a) for the illumination wavelength of 546 nm. The experimentally measured FWHM of a 150 nm gold nanoparticle with APOM is about 770 nm along the z-axis, agreeing with the vector diffraction theory (Fig. 2c). The field of view of APOM is mainly determined by the range in which the remote lens L3 can cancel the aberrations caused by the objective OBJ. We imaged a test sample of a nano-hole array with a period of 7 μm perforated in a gold film (Supplementary Fig. S2). The nano-hole array was placed in the axial plane of the 100× objective OBJ with a wide-field illumination. As shown in Fig. 2d, the 70 µm × 70 µm nano-hole array is well-resolved by the APOM with negligible distortions over the entire array, confirming that APOM is well suited to directly image the axial cross-section of large samples. The axial field of view of APOM is much larger than the depth-of-focus of the same high NA objective in a conventional microscope which is typically less than 1 μm.

Figure 2. Calibration of the APOM.

(a) The x-z section of the calculated intensity point spread function (PSF) of the axial plane image when NA = 1.4, oil immersion (n = 1.52) objective lenses are used and the signal is assumed to be an unpolarized light at the wavelength of 546 nm. (b) Measured axial plane image of a 150 nm diameter gold nanoparticle placed near the focus of OBJ. (c) Profiles of the PSF in the axial direction. The black squares are measured profile of a 150 nm gold nanoparticle in the axial direction, while the red curve is the theoretical profile of the PSF. (d) The axial plane optical image of a 70 µm × 70 µm nano-hole array with a period of 7 µm. The nano-hole array is placed parallel to the optical axis of OBJ. Wide-field light from a tungsten lamp is used for the illumination. The scale bars in (a) and (b) are 1 µm, and the one in (d) is 10 µm.

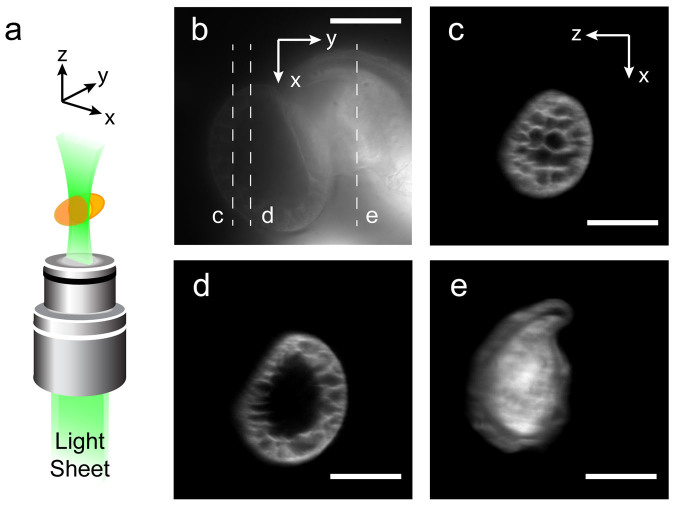

For thick fluorescent biological samples, the APOM naturally allows selective-plane illumination microscopy (SPIM)21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28 with a single objective lens near the sample, enabling axial plane fluorescence imaging with high contrast and throughput (Fig. 3). The SPIM significantly increases the image contrast by only illuminating a selected cross-section of the sample and eliminating background fluorescence from other parts outside the region of interest21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28. Compared to laser-scanning confocal microscopy, the SPIM allows faster imaging, higher signal-to-noise ratio and reduces overall photo-bleaching22. A major disadvantage of conventional SPIMs has been that they require two or more objective lenses configured at two perpendicular axes near the sample, one for illumination and the other for detection. The configuration of closely installed objective lenses has limited the size of the samples, NA of the objectives and thus the general applications of SPIM. For example, it is highly challenging to apply SPIM for imaging large mouse brains. In contrast, the APOM uses only one high NA objective near the sample for both selective plane illumination and signal collection. Comparing to former oblique plane microscopy10,11,12 that was limited to small tilting angles, APOM can image the axial plane directly, which simplifies the optics of the selective plane illumination. As shown in Fig. 3a, we applied a thin light sheet parallel to the optical axis of the objective lens for illumination. In this work, the light sheet is a 532 nm laser beam with a waist (thickness) of about 2 µm. As a demonstration, we used this APOM with the light-sheet illumination to image auto-fluorescent pine pollens (Fig. 3). The pollens imbedded in polymer are intact commercial samples prepared for conventional wide-field microscopes. Figure 3b is a lateral plane fluorescence image of the pine pollen under wide-field illumination, showing low contrast due to the background fluorescence from out-of-focus parts. On the other hand, the axial plane images (Fig. 3c–e) shows very high contrast. The shell and hollow structures of the pollen with feature size about 1 µm are clearly resolved.

Figure 3. Lateral and axial plane auto-fluorescence images of the pollen taken by the APOM.

(a) For high-contrast axial plane imaging, the sample is illuminated by a thin laser sheet through the same objective lens (OBJ) used for image collection. The orange ellipsoid represents the sample. The laser sheet is generated by a pair of cylindrical lenses placed before the objective lens. The width of the laser sheet is about 2 µm. (b) A lateral plane image of the pollen, taken by a wide-field illumination using a mercury lamp. (c), (d), (e) are the axial plane images of three different cross-sections of the pollen as labeled in (b). The axial plane images have much higher contrast and better resolved features than the normal plane image because of the optical sectioning by light-sheet illumination. The scale bars are 20 µm.

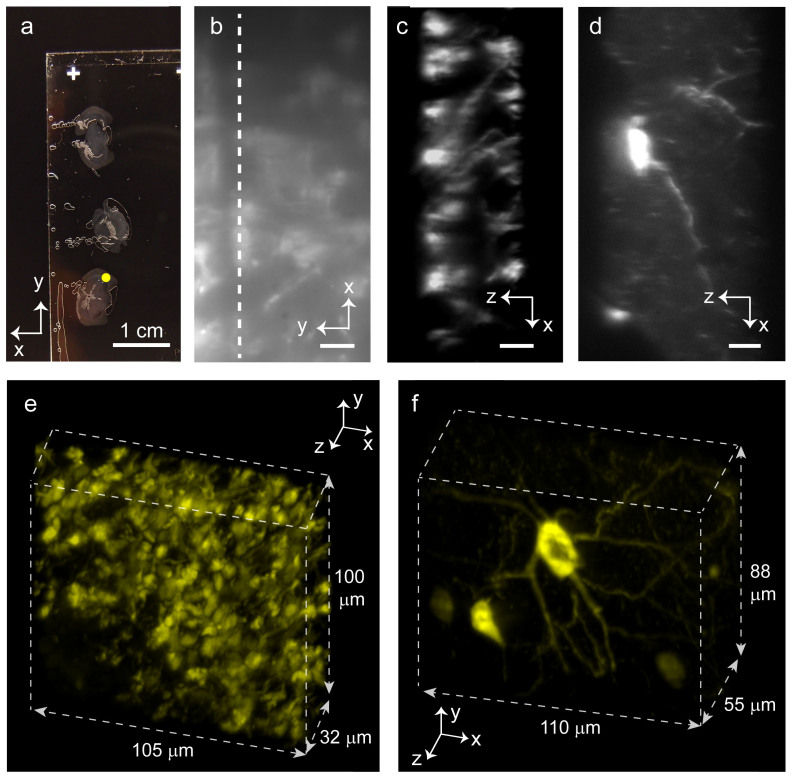

Since APOM uses only one objective near the sample for SPIM, it does not require special sample preparation and is particularly suitable for imaging structures well beneath the surface of large samples, for example, the cerebral cortex of living mammal brains29,30. As a demonstration, we use the APOM to image fluorescently labeled centimeter-scale mouse brain slices (Fig. 4a), where the conventional SPIM with the multiple objectives configured near the sample is very difficult to apply. Figure 4b shows its lateral fluorescence image with wide-field illumination, and Figure 4c shows a high-contrast axial plane fluorescence image of the same brain slice with light-sheet illumination. Again, the axial plane image shows higher contrast and better-resolved features than the lateral image because of optical sectioning. Simply by scanning the sample along the y-axis, a series of axial plane images was taken and stacked together to create a 3D image efficiently. Figure 4e, 4f show the 3D fluorescence images of two different mouse brain slices with different fluorescence labeling, which display dense and sparse brain structures, respectively30,31 (see also Supplementary videos 1, 2). Figure 4c is a cross-section of Fig. 4e, and Figure 4d is a cross-section of the Fig. 4f. Different from laser scanning confocal microscopy, the APOM can obtain a 2D axial plane image without scanning, and a 3D image by scanning along only one direction.

Figure 4. Fluorescence imaging of large mouse brain sections by APOM with selective plane illumination.

(a) A picture of centimeter-scale fluorescently labeled mouse brain slices embedded in polymer. No special sample preparation is required for APOM. The thickness of the brain slices shown in (a, b, c, e) is about 32 µm, and the thickness of the brain slice shown in (d, f) is about 55 µm. (b) A normal plane image of the brain slice in the region, as marked by a yellow dot in (a). The size of the yellow dot is larger than the area shown in (b) for better visibility of the marking dot. The dashed line in (b) indicates the y position of the cross-section shown in (c). (c) An axial plane image of a cross-section of the brain slice as labeled in (b). (d) An axial plane image of a thicker brain slice. (e) and (f) show two 3D fluorescent images of the mouse brain sections obtained by stacking a series of axial plane images together. (e) shows a dense regime while (f) shows a more sparsely stained one. The scale bars are 1 cm in (a), 10 µm in (b-d), respectively.

Discussion

The APOM can be further improved in several ways. Its resolution can be increased by using objective lenses with larger NA. Objective lenses with 1.49 NA are commercially available and can improve the axial resolution of APOM to about 450 nm for the wavelength of 546nm (Supplementary Fig. S1). The field of view can be increased to about 200 µm × 200 µm without decreasing the resolution by using commercially available 40×, 1.4 NA objectives15. The tilted mirror can also be rotatable to achieve arbitrary plane imaging. Our APOM requires no special preparation of the sample and allows the use of samples on standard microscope slides. We note that the recently developed inverted selective plane illumination microscopy (iSPIM) has partially lessened the drawbacks of conventional SPIM, permitting conventional mounting of specimens32. However, the iSPIM still requires two objective lenses with overlapping focuses configured at two perpendicular axes near the sample, which limits the use of higher NA lenses for imaging large samples at higher resolutions. The oblique plane microscopy10,11,12 has been previously limited to image oblique planes with small tilting angles due to its optical configuration. The combination of the current optical arrangement and the silicon-wafer mirror with a flat edge allows our system to image oblique planes at arbitrary tilting angles between 0–90°. To further improve the resolution of the system by light sheet illumination, the thickness of the light sheet must be small over a wide field comparing to the PSF of the system. This is difficult to achieve with conventional Gaussian light sheets, but can be achieved with thin Bessel beams33. Our APOM system can generate thin Bessel illumination beams easily because the whole aperture of the objective lens (NA = 1.4) can be used for illumination.

In conclusion, we demonstrated a novel microscopy APOM, capable of directly imaging the axial plane cross-sections of various 3D samples without scanning. The acquired image shows negligible distortion over a large field of view (> 70 µm × 70 µm), which is much larger than the depth of focus in conventional optical microscopy. When a laser sheet is used for illumination through a single objective near the sample, the APOM provides fast, high-contrast, and convenient 3D images of thick biological samples such as pollens and brain slices. APOM with light-sheet illumination opens a new avenue for many exciting biological applications such as direct imaging of a living brain from its surface. Moreover, the light sheet from the single high NA objective lens can be easily thinned down further to reduce the excitation volume and consequently increase signal-to-background ratio, towards fast and convenient imaging of single fluorescent molecules34,35.

Methods

Optical setup

The main components of APOM are shown in Fig. 1a. Both the objective lens (OBJ) near the sample and the remote lens (L3) are Zeiss Plan-Apochromat 100×/NA 1.4 oil immersion objective lenses. The tube lenses (L1, L2, L4, L5) are f = 150 mm achromatic doublet lenses. BS1 is a 90% reflection beam splitter, while BS2 is a 50% beam splitter. The tilted mirror M1 is a cleaved silicon wafer coated by about 150 nm of aluminum. We used a cleaved silicon wafer because it has a very straight and shape edge. So the mirror is usable even only a few micrometers away from its edge. This allows us to tilt the mirror at 45 degree as respected to the optical axis of the L3. This tilted mirror converts the image in the axial plane of L3 to an image in the lateral plane of L3. A ray tracing simulation of the principle of APOM is shown in Fig. 1c.

The illumination light is from a tungsten lamp for imaging the nano-hole array shown in Fig. 2d, while it is from a mercury lamp for the normal plane images of fluorescent pollens and mouse brain slices (Fig. 3b, 4b). To take the axial plane images of biological samples with high contrast, we used a 532 nm laser light sheet. The light sheet is generated by passing a laser through a pair of cylindrical lenses (f = 15 mm and f = 200 mm). We also used a narrow slit to further reduce the thickness of the light sheet. We typically use a light sheet with a thickness of about 2 micrometers near the focus of the OBJ for selective plane illumination. The camera used for taking the fluorescent images is a Luca R EMCCD camera from Andor. For fluorescence imaging, a 580 nm long pass filter (not shown in Fig. 1a) is placed in front of the camera to block the illumination light while letting the fluorescent signal pass through.

Point spread function of APOM

Due to the 45° tilted mirror in APOM, the half-cone angle of the objective lens for signal collection must be greater than 45°, corresponding to 0.71 NA in air and 1.07 NA in a n = 1.52 oil. The classical scalar diffraction theory is inaccurate in this high NA regime and thus we used the vector diffraction theory that properly deals with high aperture systems. We first determined an effective 3D pupil function in APOM (NA = 1.4, n = 1.52) by considering the reflected beam path from the tilted mirror back to the exit pupil as shown in Fig. 1b, which is rotationally asymmetric about the optical axis in the spherical coordinate. Then, to predict theoretical intensity point spread function (PSF) of APOM for an unpolarized point object (λ = 546 nm), we numerically evaluated multiple double integrals, in MATLAB, consisting of the vector Debye integral14,15 over the derived effective 3D pupil area. For such a numerical simulation, we also assumed that the objective lens satisfies the Abbe's sine condition and the whole system is aberration-free. The FWHM of the PSF as a function of NA is shown in Supplementary Fig. S1.

Nano-hole array fabrication and imaging

The nano-hole array was fabricated and used for demonstrating the distortion-free large-scale axial plane imaging. We first deposited 2 nm of chromium and 150 nm of gold film on a clean glass cover slip using an electron beam evaporator. We then milled the array of circular holes in the gold film using a focused ion beam. An array of 11 × 11 holes were fabricated with a hole separation of 7 μm (Supplementary Fig. S2). The diameter of each hole is about 500 nm. The array was fabricated near the edge of the coverslip, allowing it to be placed within the working distance of the objective lens in the APOM system. In the imaging experiment, the fabricated sample was aligned to be parallel to the optical axis of the objective lens OBJ, and also be parallel to the edge of the titled mirror M1. The sample was placed in the index-matched oil of the oil-immersion objective lens for imaging.

Pollen sample

A slice of mixed pollen grains was purchased from Carolina Biological Supply Inc. (Burlington, USA). It was prepared for conventional wide-field optical microscopy. Pollens were embedded in a polymer whose optical refractive index is close to that of glass for using with oil immersion objective lenses.

Mouse brain sections

Two kinds of fluorescently labeled brain sections shown in Fig. 4 were kindly gifted by Dr. Kazunari Miyamichi in Stanford University and Dr. Hongfeng Gao at UC Berkeley, respectively. A sample shown in Fig. 4b, 4c, 4e is a brain section with 32 μm thickness, prepared from a Thy1-GCaMP3 mouse. The cells genetically expressed by GCaMP3 protein are immnostained by using GFP antibodies conjugated with Cy3. The other sample shown in Fig. 4d, 4f is another brain section with 55 μm thickness from a transgenic mouse and labeled with td-Tomato. The APOM images axial cross-sections of the sample directly. To obtain a 3D image, we stepped the sample along y-axis with an interval of 0.5 µm by a motorized translation stage. Then a series of axial plane images were stacked together to form a 3D image.

Author Contributions

T.L. and S.O. designed the experiment, S.O. and Z.J.W. fabricated samples, J.K. performed simulation, S.O. and T.L. conducted measurements. X.Z., Y.W. and X.Y. guided the research. All authors contributed to data analysis and discussions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary video 1

Supplementary video 2

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Kazunari Miyamichi at Stanford University and Hongfeng Gao at UC Berkeley for providing fluorescently labeled mouse brain sections. We thank Hu Cang, Peng Zhang and Ziliang Ye for helpful discussions. We also appreciate the support from the CNR Biological Imaging Facility at UC Berkeley. This research is funded by the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation.

References

- Abbe E. On the Mode of Vision with Objectives of Wide Aperture. J. of the Royal Microscopical Society 4, 20–26 (1884). [Google Scholar]

- Murayama M., Pérez-Garci E., Nevian T., Bock T., Senn W. & Larkum M. E. Dendritic encoding of sensory stimuli controlled by deep cortical interneurons. Nature 457, 1137–1141 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang N., Butler J. P. & Ingber D. E. Mechanotransduction across the cell surface and through the cytoskeleton. Science 260, 1124 (1993). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingber D. E. Cellular mechanotransduction: putting all the pieces together again. The FASEB Journal 20, 811 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri O., Parekh S. H., Lam W. A. & Fletcher D. A. Combined atomic force microscopy and side-view optical imaging for mechanical studies of cells. Nat. Methods 6, 383–387 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conchello J.-A. & Lichtman J. W. Optical sectioning microscopy. Nat. Methods 2, 920–931 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang T. & Yamaguchi I. Three-dimensional microscopy with phase-shifting digital holography. Opt. Lett. 23, 1221–1223 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charrière F. et al. Living specimen tomography by digital holographic microscopy: morphometry of testate amoeba. Opt. Express 14, 7005–7013 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sung Y. et al. Optical diffraction tomography for high resolution live cell imaging. Opt. Express 17, 266–277 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsby C. Optically sectioned imaging by oblique plane microscopy. Opt. Express 16, 20306–20316 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Wilding D., Sikkel M. B., Lyon A. R., MacLeod K. T. & Dunsby C. High-speed 2D and 3D fluorescence microscopy of cardiac myocytes. Opt. Express 19, 13839–13847 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutrale F. & Gratton E. Inclined selective plane illumination microscopy adaptor for conventional microscopes. Micros. Res Tech. 75, 1461–1466 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botcherby E. J., Booth M. J., Juškaitis R. & Wilson T. Real-time slit scanning microscopy in the meridional plane. Opt. Lett. 34, 1504–1506 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botcherby E. J., Juškaitis R., Booth M. J. & Wilson T. Aberration-free optical refocusing in high numerical aperture microscopy. Opt. Lett. 32, 2007–2009 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botcherby E. J. et al. Aberration-free three-dimensional multiphoton imaging of neuronal activity at kHz rates. PNAS 109, 2919–2924 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anselmi F., Ventalon C., Bègue A., Ogden D. & Emiliani V. Three-dimensional imaging and photostimulation by remote-focusing and holographic light patterning. PNAS 108, 19504 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards B. & Wolf E. Electromagnetic diffraction in optical systems. II. Structure of the image field in an aplanatic system. Proc. R. Soc. London. A 253, 358–379 (1959). [Google Scholar]

- Stamnes J. J. Waves in Focal Regions (Hilger, Bristol., 1986). [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard C. J. R. & Matthews H. J. Imaging in high-aperture optical systems. JOSA A 4, 1354 (1987). [Google Scholar]

- Gu M. Advanced Optical Imaging Theory (Springer, 2000). [Google Scholar]

- Huisken J., Swoger J., Del Bene F., Wittbrodt J. & Stelzer E. H. K. Optical Sectioning Deep Inside Live Embryos by Selective Plane Illumination Microscopy. Science 305, 1007–1009 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verveer P. J. et al. High-resolution three-dimensional imaging of large specimens with light sheet–based microscopy. Nat. Methods 4, 311–313 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mertz J. Optical sectioning microscopy with planar or structured illumination. Nat. Methods 8, 811–819 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krzic U., Gunther S., Saunders T. E., Streichan S. J. & Hufnagel L. Multiview light-sheet microscope for rapid in toto imaging. Nat. Methods 9, 730–733 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomer R., Khairy K., Amat F. & Keller P. J. Quantitative high-speed imaging of entire developing embryos with simultaneous multiview light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods 9, 755–763 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodt H.-U. et al. Ultramicroscopy: three-dimensional visualization of neuronal networks in the whole mouse brain. Nat. Methods 4, 331–336 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens M. B., Orger M. B., Robson D. N., Li J. M. & Keller P. J. Whole-brain functional imaging at cellular resolution using light-sheet microscopy. Nat. Methods 10, 413–420 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holekamp T. F., Turaga D. & Holy T. E. Fast three-dimensional fluorescence imaging of activity in neural populations by objective-coupled planar illumination microscopy. Neuron. 57, 661–672 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osten P. & Margrie T. W. Mapping brain circuitry with a light microscope. Nature Methods 10, 515–523 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamichi K. et al. Cortical representations of olfactory input by trans-synaptic tracing. Nature 472, 191–196 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Q. et al. Imaging Neural Activity Using Thy1-GCaMP Transgenic Mice. Neuron 76, 297–308 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y. et al. Inverted selective plane illumination microscopy (iSPIM) enables coupled cell identity lineaging and neurodevelopmental imaging in Caenorhabditis elegans. PNAS 108, 17708 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao L., Shao L., Chen B.-C. & Betzig E. 3D live fluorescence imaging of cellular dynamics using Bessel beam plane illumination microscopy. Nature Protocols 9, 1083 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanacchi F. C. et al. Live-cell 3D super-resolution imaging in thick biological samples. Nat. Meth. 8, 1047–1049 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebhardt J. C. M. et al. Single-molecule imaging of transcription factor binding to DNA in live mammalian cells. Nat. Meth. 10, 421–426 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary video 1

Supplementary video 2

Supplementary Information